Abstract

During the operation of the magnetic fluid sealing device, a large amount of heat is generated due to the viscous friction of the magnetic fluid, causing the shaft to deform and thus affecting the sealing effect. This paper explores the thermal expansion effect of the magnetohydrodynamic sealing device under the working conditions of an axle diameter of 1030 mm and a maximum rotational speed of 700 r/min. The temperature distribution law under the action of a magnetic field, the influence of thermal deformation caused by temperature on the sealing performance, and the influence of the selection of shaft and pole shoe materials on the magnetic fluid sealing device were studied. Research findings show that in magnetic fluid sealing, an increase in system temperature can enhance the sealing effect, but it will cause thermal expansion of the rotating shaft and change the gap. By adopting a combination of different materials for the rotating shaft and the pole shoe, the sealing performance can be optimized and improved.

1. Introduction

Magnetic fluid is a new type of intelligent material widely used in machinery, aviation, acoustics and other fields. It has the advantages of zero leakage, high reliability, long-term durability and good recovery.

In recent years, due to the rapid development of China in the fields of machinery, petroleum and chemical engineering, although the rotational speed of general centrifuges can reach several thousand or tens of thousands of revolutions, the main shaft diameter is basically below 500 mm. However, in actual engineering requirements and under special working conditions, the main shaft diameter needs to be above 1000 mm and the rotational speed above 1000 r/min. Obviously, the current centrifuges are gradually unable to meet the usage requirements of these special working conditions. Therefore, for the main shaft sealing of large centrifuges, adopting a magnetic fluid sealing method is a relatively good choice.

Zhou [1] conducted a study on the lubrication characteristics of magnetic fluid membranes based on a helical groove mechanical seal test bench combined with numerical analysis methods. The research revealed how the magnetic field affects the fluid dynamic pressure effect of the magnetic fluid. It has been proven that the sealing capability can be controlled by adjusting the current intensity of the magnetic generator, thus expanding the application scenarios of magnetic fluid seals. Szczęch [2] proposed a computational model for the pressure resistance of magnetohydrodynamic seals based on magnetic field numerical analysis. By examining pressure transmission mechanisms in multi-stage seal structures, this approach was found to reduce discrepancies between simulation results and experimental data. It has been proved that the increase in the volume of the magnetic fluid applied during the sealing stage and the increase in the magnetic saturation in the sealing gap can reduce the influence of manufacturing errors. Cao [3] aimed to resolve the problem that harsh working conditions, such as low assembly and processing accuracy, heavy loads, and high rotational speeds, lead to mechanical equipment vibration and radial oscillation. To achieve this, he developed a large-gap magnetic fluid sealing scheme with axial and radial distribution. With the commonly used rollers in mining equipment as an example, a simulation test on sealing performance in underground environments was performed using a mining roller operating resistance test bench. The research results have significant theoretical and practical value in addressing the shortcomings of the magnetic liquid sealing structure and expanding the application fields of magnetic liquids. Wang [4] developed a dual-rotating ferrofluid vane micropump with embedded permanent magnets, accompanied by prototype design, magnetic field analysis, and experimental validation. Through numerical simulations and experimental investigations of the magnetic field within the pump chamber, the structural parameters of the micropump were systematically optimized. The pump’s gas flow rate and pumping height were characterized under various rotational speeds. The magnetic field of the single-sided magnetic source decays rapidly with distance, which limits the pumping performance. No attempts were made to adopt a better magnetic layout such as a dual-sided magnetic source. And in the future, long-term operation tests can also be conducted. Qiao [5] addressed the limitation of traditional magnetic fluid seals frequently failing under high-speed operational conditions. To overcome this deficiency, a novel magnetic fluid seal structure specifically engineered for high rotational speeds was developed. The experimental configuration utilized a sealed shaft with a 45 mm diameter operating at 30,000 rpm, which was systematically compared against conventional magnetic fluid sealing structures. A systematic comparative study was later conducted to examine the effects of magnetic source configuration (single versus dual), magnetic pole location, and rotational speed on sealing performance. These discoveries supply important guidance for the engineering design of high-speed magnetic fluid seal structures. Although the magnetic fluid with high saturation magnetization can enhance the pressure resistance, it has a relatively high viscosity, which leads to viscous heating at high speeds and thus there is still room for performance optimization. Li [6] proposed an experimental device for testing the sealing performance of magnetic fluids, in order to determine the relationship between the volume of magnetic fluid injected into the sealing gap and the sealing pressure. The research results show that when the volume of ferromagnetic fluid is less than 0.5 mL, the sealing pressure is positively correlated with its volume. The system characterizes the key parameters such as the magnetization characteristics and the viscosity-temperature characteristics of the silicone oil-based magnetic fluid. Through simulation and experimental verification, it also examines the influence mechanism of the injection volume on the sealing failure. However, this study did not take into account the interference of common factors such as temperature and rotational speed in actual working conditions, and thus was unable to clearly determine the coupling effect of these factors with the injection volume on the sealing performance. Bhandari [7] utilized COMSOL Multiphysics software to optimize the sealing performance of liquid magnetic fluids within rotating systems. The numerical solution comprehensively considered viscosity effects induced by rotation and the influence of magnetic fields on fluid flow. For the first time, rotational viscosity and magnetization force were incorporated into the magnetic fluid flow model, taking into account the effects of radial and tangential magnetic fields. This filled the gap in traditional models that ignored the coupling relationship between magnetic viscosity and heat transfer. However, the parameter values used in the simulation are based on existing literature and do not cover a wider range of parameters. Therefore, they are unable to accurately reflect the magnetic fluid flow characteristics under extreme conditions. Fan [8] designed a dual-magnetic-source seal structure to enhance pressure resistance of ferromagnetic fluid seals under large-gap conditions, employing finite element analysis to study magnetic field distribution within the seal gap. The study focused on investigating the effects of seal gap dimensions, permanent magnet length-to-height ratio, seal groove width, and the ratio of pole shoe height to shaft radius on sealing performance. Results indicated that increasing the seal gap significantly reduced pressure capacity. Pressure capacity first decreased then increased with increasing seal groove width, while it first increased then decreased with increasing pole shoe height-to-shaft radius ratio. Tomioka [9] designed a magnetic fluid seal device for plasma pump applications. Four magnetic fluids were tested via biocompatibility hemolysis experiments to investigate their sealing pressure resistance and durability characteristics. It was found that water-based magnetic fluids are unsuitable for plasma pump magnetic fluid seals. This research achievement has expanded the application scope of magnetic fluid seals and promoted the development of magnetic fluid seal technology in the medical field. Cong [10] conducted systematic investigations into magnetic fluid sealing characteristics under high-speed vacuum conditions. Through theoretical analysis and experimental validation, the influence mechanisms of various operating parameters on sealing performance were revealed, providing crucial theoretical guidance for optimizing magnetic fluid seal designs in high-speed vacuum environments. The paper uses the control variable method to optimize the parameters, but fails to take into account the coupling effects among multiple parameters, which may result in the overall structure not achieving the optimal performance. Rosenzweig [11] employed an improved Kelvin-Helmholtz instability theoretical model. By integrating the coupled effects of multiple factors—including magnetic field strength, relative permeability, density, and interfacial tension—theoretical calculations revealed the relationship between the critical relative velocity at the magnetic fluid-liquid interface and interface instability. This research provides crucial theoretical foundations for the application of magnetic fluid1 in liquid medium sealing. Chen [12] conducted a simulation calculation of the fluid temperature field and established a relationship between the saturated magnetization intensity and temperature, in order to quantitatively calculate the magnetic performance attenuation; and based on the magnetization curve results, the two-phase flow field of air-magnetic fluid under different rotational speeds was solved. The results show that the simulation results of the gas–liquid two-phase flow sealing ability are in good agreement with the experimental results, proving that in engineering applications, the simulation calculation method can be used to verify the rationality of the design of magnetic fluid seals. In the future, we can conduct in-depth research on the coupling effects between structural factors such as sealing gaps and pole teeth parameters and temperature rise. Parmar [13] conducted performance tests on a two-stage magnetic fluid seal with an axial diameter of 20 mm and variable rotational speed and radial clearance. The influence of radial clearance and fluid magnetization intensity on pressure difference was analyzed using the finite element method. Finally, it was stated that this seal can be applied to the bearing protection of large-axial-diameter, low-pressure chemical vapor deposition vacuum equipment, the isolation sealing of stepper motors and robotic arms, etc. Mitamura [14] designed a magnetic fluid sealing device with a “shielding” function that can be applied in liquid environments. This shielding device can prevent the magnetic fluid from flowing out and mixing with the liquid, thereby extending the service life of the magnetic fluid seal. If this article includes research on the sealing mechanism, it would be even better and more conducive to promoting the progress of research on magnetic fluid seals for liquid media.

In summary, scholars have proposed research on new sealing structures for complex working conditions such as high speed, large clearances, and liquid media. By integrating experiments, simulations, and theoretical models, they have revealed the influence mechanisms of factors such as magnetic fields, fluid volume, and temperature from multiple perspectives. They have also introduced coupling factors such as rotational viscosity, magnetic force, and two-phase flow, which cover fields such as industry and biomedicine. However, some studies have not comprehensively considered factors such as temperature, rotational speed, and thermal deformation. The parameter range of simulation or experiments is relatively narrow, making it difficult to reflect the performance under extreme working conditions. There is a lack of in-depth research on some mechanisms of magnetohydrodynamic sealing, and most of them ignore the deformation of the sealing device and the sealing effect caused by temperature rise and the selection of different materials. Therefore, in this paper, through the coupling mechanism among heat, water and force, the thermal expansion effect of the magnetohydrodynamic sealing device with an shaft diameter of 1030 mm and a maximum rotational speed of 700 rad/min is explored. Through the coupling analysis among heat, flow and solid, the distribution law of its temperature at different rotational speeds and the influence of different material choices for the rotating shaft and pole shoe on the sealing performance are studied, in order to provide a theoretical basis for the design and application of magnetohydrodynamic seals under high-speed working conditions with large shaft diameters.

2. Theoretical Basis

The expression of the magnetic force of the magnetic fluid in the cylindrical coordinate system under a unit volume is as follows [15]:

where

,

, and

denote the radial, circumferential, and axial components of the magnetic field on the cylinder, respectively.

and

represent the magnetic field intensities in the radial and axial directions, respectively.

and

refer to the radial and axial components of the magnetization intensity, respectively.

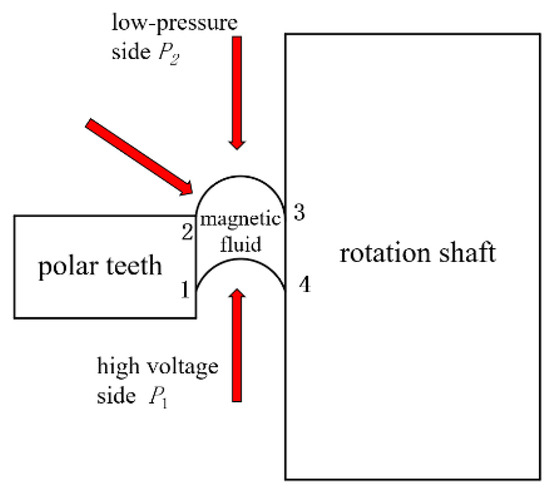

Magnetic fluid demonstrates fluidity during operation and responds to external magnetic fields, being classified as an incompressible liquid. The working pressure situation is shown in Figure 1, where P1 represents the high-pressure region and P2 represents the low-pressure region. When gravitational effects are neglected, the equation of motion for magnetorheological fluid can be expressed as [1,16,17]:

where

represents the magnetic fluid density,

denotes the magnetic fluid velocity,

indicates the pressure gradient applied to the magnetic fluid,

stands for the temperature-dependent fluid viscosity, and

refers to the Kelvin force, which represents the body force acting on the magnetic fluid within the magnetic field. The expression for this force is given by:

where

represents the permeability of free space, while

and

denote the magnetization and magnetic field intensity, respectively.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of magnetic fluid working under pressure.

In the analysis of the flow tube with steady-state magnetic fluid sealing, the high-pressure interface (1, 4) and the low-pressure interface (2, 3) are selected as two reference cross-sections. From the Bernoulli equation, the interface equation can be derived, then:

In the equation,

stands for the pressure resistance of a single pole tooth. The initial term on the right-hand side indicates the impact of magnetic field pressure, and the subsequent term describes how centrifugal force affects the sealing performance.

As this paper centers on the effects of temperature and thermal expansion factors on sealing performance, the centrifugal force term is disregarded here. For ordinary fluids, the energy conservation equation describes the variations in fluid energy and work, which can be expressed as [18]:

In the equation,

represents the rate of change in thermal energy;

represents the difference in internal energy between fluid flowing in and out during the flow process;

represents the heat conduction of the fluid;

represents the work performed by the fluid, which becomes zero for incompressible fluids;

represents the irreversible mechanical dissipation work caused by fluid viscosity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Heat conduction model.

In the cylindrical coordinate system, the calculation expression of viscous dissipated work is [19]:

where

and

represent the shaft radius and pole shoe radius,

and

indicates the sealing clearance,

denotes the total length of the magnetic fluid along the axial direction, and

represents the linear velocity of the shaft.

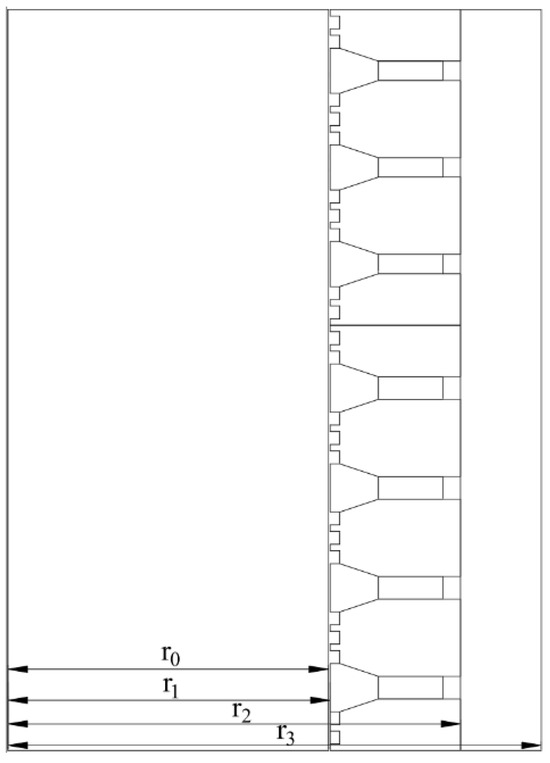

The thermal analysis of magnetic fluid sealing devices can be treated as equivalent to circuit analysis, since the governing equations for heat conduction bear striking similarity to those used in electrical circuits. In this analogy, heat sources correspond to electrical power sources, temperature corresponds to voltage, and thermal resistance corresponds to electrical resistance, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Magnetic field equivalent circuit analysis diagram.

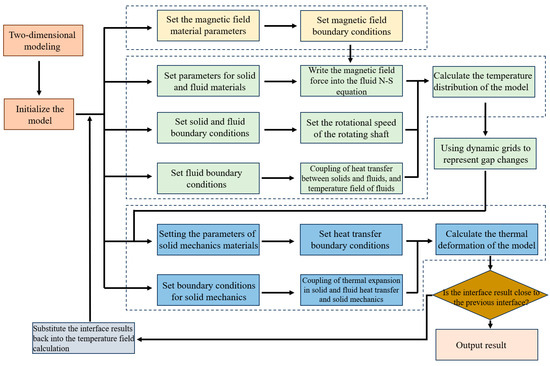

The magnetic fluid acts as the heat source for the sealing device and functions as the voltage source in the equivalent circuit. Since the permanent magnet exhibits significantly higher thermal resistance compared to the pole shoes, it can be treated as thermal capacitance, while the rotating shaft can also be modeled as thermal capacitance. The sealing device is represented as a composite cylindrical wall consisting of four layers with outer radii of r0, r1, r2, and r3, respectively, where axial heat transfer is neglected.

R1 stands for the thermal resistance of convective heat transfer between the magnetic fluid and the pole shoe; R2 and R3 denote the thermal resistances of the pole shoe and housing, respectively; R4 stands for the thermal resistance of convective heat transfer between the housing and air; C1 and C2 correspond to the heat capacities of the rotating shaft and permanent magnet, respectively; t1 and tₐ refer to the magnetic fluid temperature distant from the housing and the ambient temperature, respectively; tfi represents the temperature of each wall surface; Since the sealing device’s temperature is ambient at the initial state, the rotational shaft temperature t0 equals the magnetic fluid temperature.

When the

, heat conduction through cylindrical walls can be simplified as heat conduction through flat walls, with the thermal resistance expression given by:

where

stands for the mean radius of the surface of the cylindrical wall, calculated as

;

denotes the thickness of the cylindrical wall surface, expressed as

;

indicates the axial length of the cylindrical wall surface; and

refers to the thermal conductivity.

The thermal resistance for convective heat transfer can be expressed as:

where

and

represent the surface heat transfer coefficient of the material and the contact area between fluid and solid, respectively.

In magnetic fluid sealing devices, the magnetofluid acts as the heat source, while the housing serves as the sole pathway for heat dissipation. Based on the parallel current division principle in electrical circuits, the following relationship can be established:

In this equation,

and

denote the heat transfer power for the upper and lower sections, respectively.

The total heat flux of the convective heat transfer surface for the thin layer attached to the cylindrical wall is expressed as:

where

represents the surface heat transfer coefficient.

Under steady-state conditions, when the temperature gap between the solid and fluid surfaces remains consistent, the mean surface heat transfer coefficient corresponding to the entire wall surface may be expressed as:

To simplify a two-dimensional model into a one-dimensional model, the following formula can be applied:

where

represents the total resistance in the circuit, calculated using the following expression:

The temperature of each cylindrical wall layer is:

Let the heat flux density constant for a unit length of cylindrical pipe be

; then,

When

, the expression of the temperature distribution on the wall of the pole shoe cylinder can be derived by using the flat-wall Fourier law as:

The relationship between temperature and thermal expansion can be expressed as:

where

represents the thermal expansion coefficient of the material, and

denotes the current temperature of the material.

By substituting Equation (20) into Equation (21), the thermal expansion displacement of the pole shoe is obtained as follows:

where

The thermal expansion displacement of the rotating shaft is:

The parameters for the heat conduction model are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Model parameter.

3. Finite Element Analysis Method

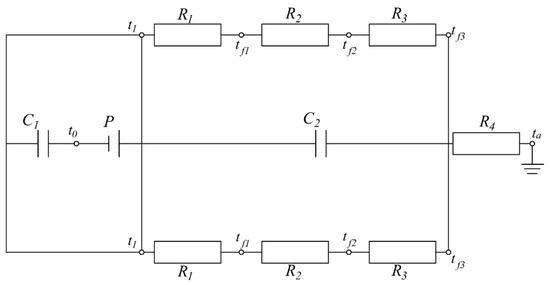

A two-dimensional model of the sealing device was developed using modeling software. The two-dimensional model was then imported into COMSOL Multiphysics simulation software for thermal expansion analysis. The complete simulation workflow is illustrated in Figure 4, representing a thermal-hydraulic-mechanical coupled model. Since the magnetic fluid sealing gap is influenced by temperature and experiences thermal expansion, the mesh variations caused by temperature field-induced gap changes were first calculated, followed by the computation of the model’s thermal expansion based on the modified mesh.

Figure 4.

Simulation flowchart.

As shown in Figure 4, the magnetic field force of the magnetorheological fluid is calculated in the first part and incorporated as a body force into the temperature field calculation. This approach determines the dynamic changes in the sealing gap caused by the temperature field under different linear velocities, along with the temperature distribution patterns, which are represented using dynamic mesh techniques. In the second part, the magnetic fluid sealing performance and boundary variations are calculated based on the dynamic mesh and temperature field conditions.

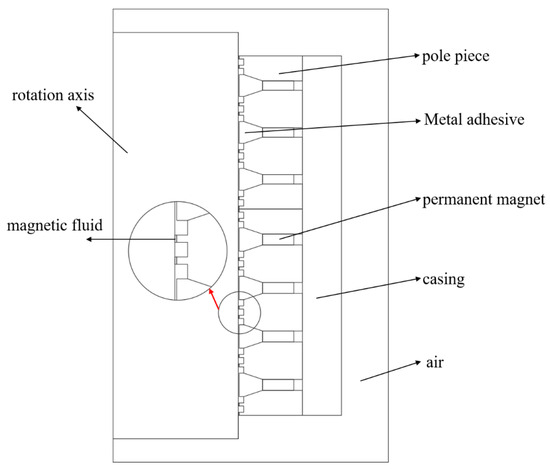

The simulation model of the sealing structure is shown in Figure 5, and the performance parameters of the materials used are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. In the simulation calculation, the ambient temperature ta is set at 25 °C. Adopt the natural convection method. The pressure that the magnetic fluid experiences in its initial state is 0.002 MPa to 0.1 Mpa.

Figure 5.

Sealing structure simulation model.

Table 2.

Model material performance parameters.

3.1. Magnetic Fluid Boundary Calculation

For the magnetic field calculations, NdFeB-N48H permanent magnets were employed, which exhibit a residual magnetic flux density of 1.37 T, an intrinsic coercivity of 1274 kA/m, a coercivity of 1000 kA/m, and a maximum energy product of 390 kJ/m3 [20]. The primary performance parameters of the magnetohydrodynamic fluid are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Magnetic fluid performance parameters.

Table 3.

Magnetic fluid performance parameters.

| Serial Number | Project | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | brand number | ZQMZ—04X |

| 2 | base carrier fluid | perfluoropolyether oil-based |

| 3 | saturation magnetization intensity | 582 Gs |

| 4 | kinematic viscosity (Pa·s) | 0.1~0.6 |

| 5 | operating temperature | −60 °C~150 °C |

| 6 | compatibility | insoluble in air, water vapor mixture, lubricating oil and oil mist |

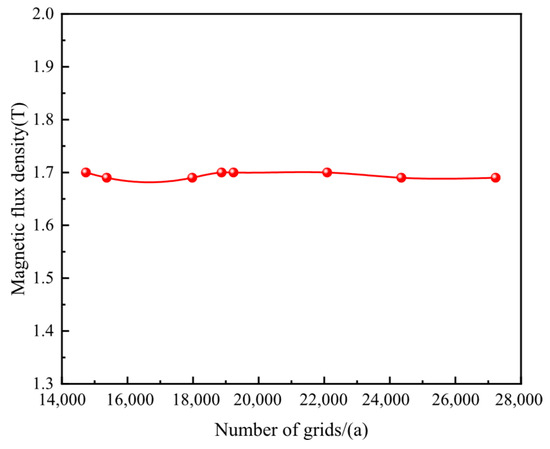

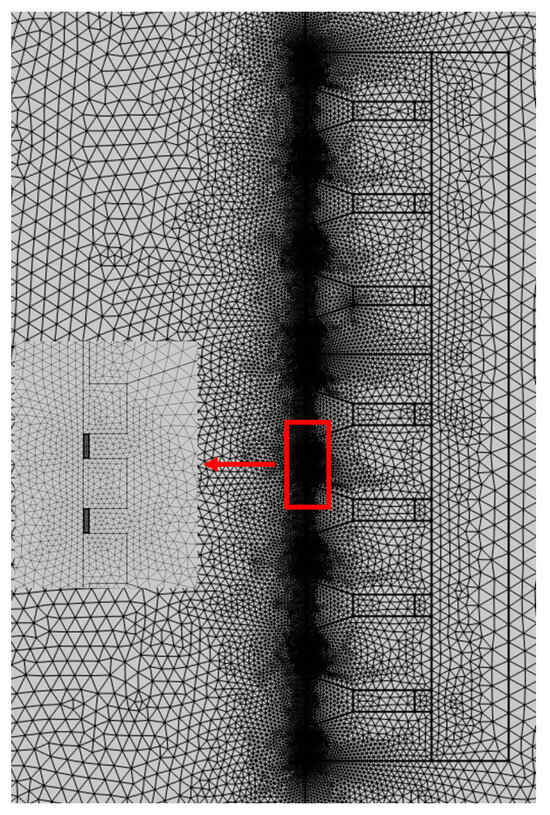

In the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model, in an ideal state, the fluid flow affecting the magnetic fluid is assumed to be laminar, with the magnetic fluid completely filling the gap between the shaft and pole teeth. To achieve more accurate results, the magnetic fluid mesh was configured with extremely fine resolution, while other parameters were maintained at their default values. To reduce the impact of grid division on the results, grid independence verification is necessary to ensure the accuracy of the simulation results. The number of grids and the maximum magnetic flux density at the sealing gap are shown in Figure 6. It can be concluded that the magnetic flux density at the sealing gap is almost independent of the change in the number of grids. The mesh configuration is illustrated in Figure 7, comprising a total of 51,684 elements with an average element quality of 0.8881, which satisfies the computational accuracy requirements.

Figure 6.

Verification of the independence between the number of grids and magnetic flux density.

Figure 7.

Grid division diagram.

3.2. Thermal Expansion Calculation

Since the sealing device is axially constrained, thermal expansion causes only radial displacement changes. Thus, the upper surface of the rotating shaft and the outer surface of the pole shoe are set with zero axial displacement, whereas free displacement is allowed between the outer surface of the rotating shaft and the inner surface of the pole shoe. Key parameters in the model are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Structural parameters.

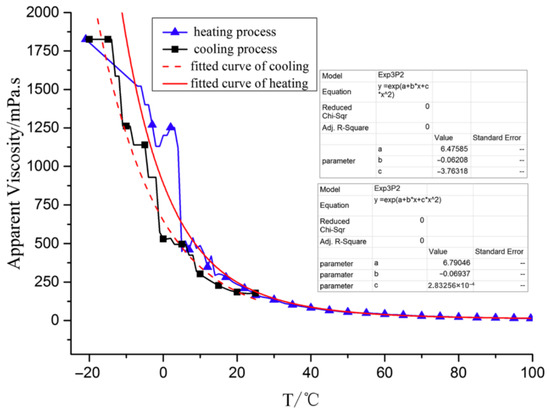

In the steady-state study, the shaft was configured as a rotating wall surface. The outer surface linear velocities of the shaft were set to 10.79 m/s, 16.18 m/s, 21.57 m/s, 26.97 m/s, 32.36 m/s, and 37.75 m/s, which correspond to rotational speeds of 200 r/min, 300 r/min, 400 r/min, 500 r/min, 600 r/min, and 700 r/min, respectively. The viscosity-temperature relationship of the magnetic fluid is presented in Figure 8, with the governing equation given as [21]:

where

denotes viscosity and

denotes temperature.

Figure 8.

Temperature dependent viscosity curve of magnetic fluid.

Calculate the thermal field by coupling solid heat transfer and flow field. In the cylindrical coordinate system, the elemental thermal equilibrium analysis of the magnetic fluid is carried out. According to the first law of thermodynamics, the increment of thermal energy within

time is:

where

denotes the specific heat capacity of the magnetofluid.

In the

,

, and

directions, the net heat input and output during the time interval dτ are given by:

where

represents the thermal conductivity coefficient.

In the differential element analysis, thermal energy is produced through viscous dissipation heat generated by the magnetofluid, where

represents the heat generation rate. The thermal equilibrium relationship can be expressed as:

By substituting Equations (26)–(29) into Equation (30) and performing simplification, the differential equation expression for magnetohydrodynamic heat conduction can be obtained as:

when steady state is reached, the right-hand side of Equation (31) becomes zero.

By calculating the thermal field, the temperature distribution of the sealing device is determined, which subsequently causes changes in the dynamic mesh and allows for the determination of thermal expansion distribution.

4. Finite Element Simulation Results

4.1. Magnetic Field Finite Element Simulation Results

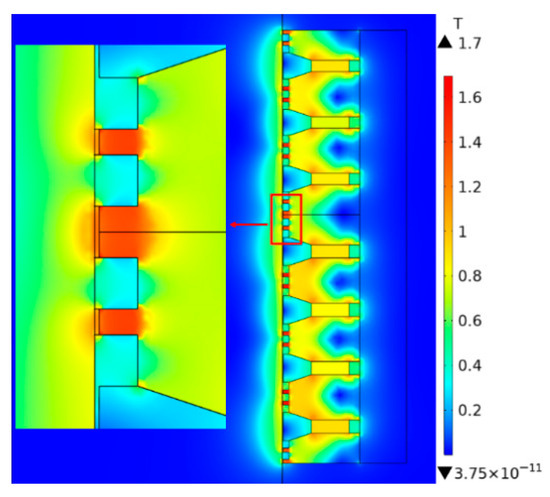

Post-processing of the simulation results revealed the distribution of magnetic flux density within the magnetic fluid seal structure and the sealing gap, as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively.

Figure 9.

Magnetic flux density distribution map.

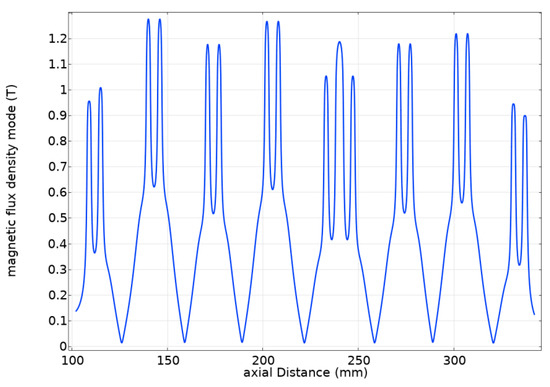

Figure 10.

Distribution law of magnetic induction intensity in sealing gap.

As presented in Figure 9, the regions with high magnetic flux density are concentrated at the pole teeth of the pole shoes, showing an alternating high-low distribution along the axial direction. This distribution helps adsorb the magnetic fluid, gathering it in the pole teeth area to form a stable liquid O-ring seal. At the same time, the magnetic induction intensity in the tooth slot area is weaker than that right below the pole teeth, and its magnitude decreases gradually from the center of the pole teeth to both sides.

To prevent leakage of the sealing medium due to inadequate sealing pressure at the gap, it is essential to calculate the local magnetic flux density. In Figure 10, the horizontal axis represents the axial coordinate along the shaft surface, and the vertical axis plots the corresponding magnetic flux density. Wave peaks are formed at the pole tooth tips, and wave troughs are created at the pole tooth gaps. The pressure values on the two sides of the pole teeth are lower than those beneath the pole teeth; this obvious pressure difference further gives rise to a magnetic field gradient. This analysis demonstrates that the liquid film formed by the magnetic fluid possesses excellent sealing capability and can withstand substantial pressure differences. Based on the pressure resistance formula calculation in Equation (6), the maximum pressure resistance value of this sealing structure reaches 1.054 MPa, which satisfies the sealing requirements under operating conditions.

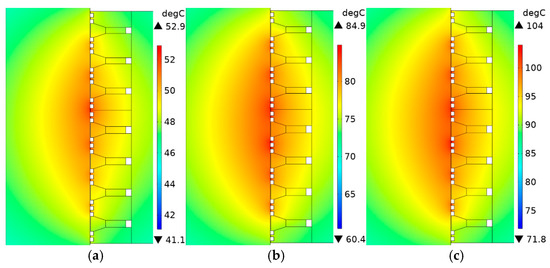

4.2. Finite Element Simulation Results of Temperature Field

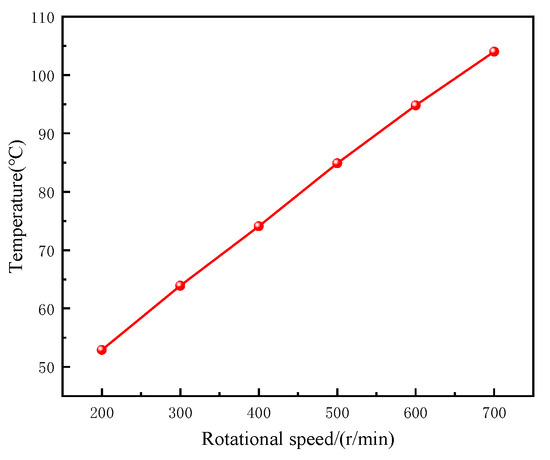

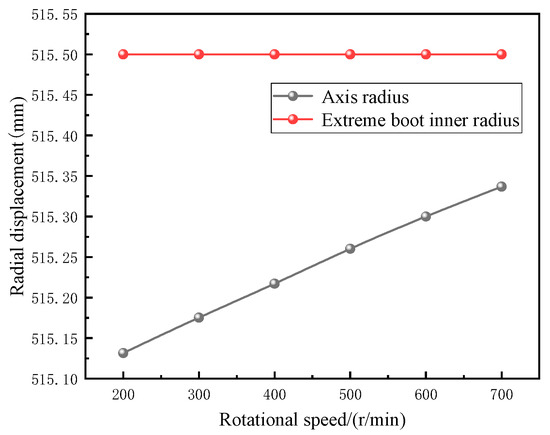

After the sealing device enters a steady state, the temperature distribution and thermal expansion displacement fluctuations of components including the rotating shaft and pole shoe assembly are displayed in Figure 11 and Figure 12, respectively. The results demonstrate that both temperature rise and displacement increase as linear velocity increases. A linear relationship between rotational speed and temperature was further established through simulation analysis, as illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 11.

Temperature distribution cloud map: (a) 200 r/min; (b) 500 r/min; (c) 700 r/min.

Figure 12.

Cloud map of thermal expansion displacement changes in the sealing gap: (a) 200 r/min; (b) 500 r/min; (c) 700 r/min.

Figure 13.

Temperature variation chart with rotational speed.

Figure 11 reveals that the temperature distribution of the sealing device exhibits a stepwise decrease from the center along the axial direction. The axial rotational speed remains constant across the outer cylindrical surface of the rotating shaft. Through comprehensive analysis of Figure 9 and Figure 10, it is observed that when the axial rotational speed is constant, the temperature level correlates with the magnetic flux density intensity of the pole teeth. Higher magnetic flux density leads to greater magnetic fluid adsorption beneath the pole teeth, which generates increased heat through viscous friction and results in elevated temperatures.

As shown in Figure 13, although the temperature increases with the increase in speed. Analysis based on Equation (8) reveals that for a given seal structure, the heat generation power is proportional to

. This finding, combined with the results presented in Figure 8, demonstrates that magnetic fluid viscosity decreases as temperature rises. Consequently, the thermal power of the magnetic fluid does not continue to increase with higher rotational speeds. Instead, upon reaching a certain threshold, a declining trend is observed, eventually stabilizing at a constant value.

Figure 14 reveals that temperature increases lead to thermal deformation in the structures on both sides of the sealing gap. Under free expansion conditions, thermal stress causes the pole shoe to expand axially while simultaneously undergoing radial expansion, which increases its inner diameter. When external fixed constraints are applied to the pole shoe, thermal expansion deformation of its inner diameter becomes restricted. Consequently, the rotating shaft experiences radial displacement due to thermal expansion effects, while the pole tooth structure remains essentially unchanged in its original position.

Figure 14.

Radial displacement variation diagram.

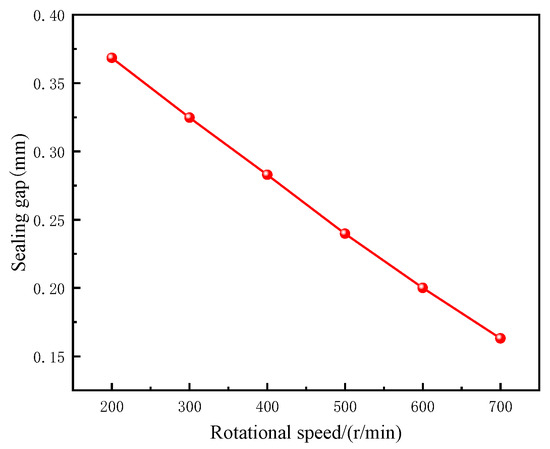

The difference between the inner radius of the pole shoe and the radius of the rotating shaft represents the sealing clearance, with its variation presented in Figure 15. The figure demonstrates that the sealing clearance decreases as rotational speed increases, indicating that thermal effects cause radial displacement of the rotating shaft.

Figure 15.

Change in sealing gap.

4.3. Analysis of Sealing Performance Results

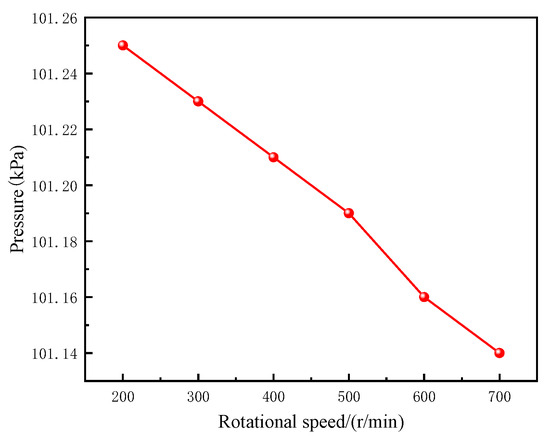

In the simulation software, the dynamic mesh was used to calculate the pressure on the outer surface of the rotating shaft, and the relationship between temperature and thermal expansion displacement was investigated, as presented in Figure 16. It is evident that with an increase in rotational speed, the pressure value declines, and rotational speed and pressure exhibit a negative correlation.

Figure 16.

The relationship between pressure value and speed variation.

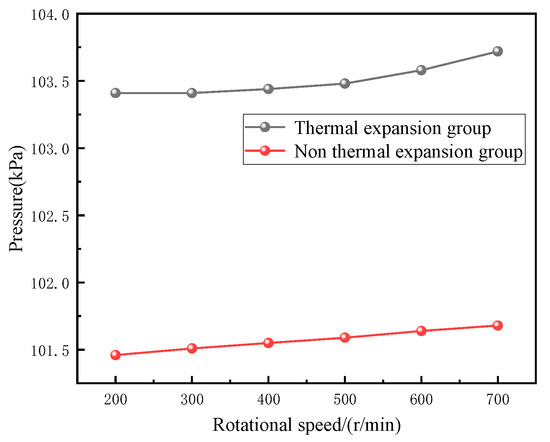

Pressure values were calculated for rotational speeds ranging from 200 rad/min to 700 rad/min, taking into account variations in temperature, magnetic fluid viscosity, seal gap, and external magnetic field strength, as illustrated in Figure 17. The upper surface of the rotating shaft and the outer surface of the pole shoe were categorized into the non-thermal expansion group, whereas the outer cylindrical surface of the rotating shaft and the inner cylindrical surface of the pole shoe were grouped into the thermal expansion group. Research findings indicate that under identical rotational speed conditions, pressure values in the thermal expansion group exceed those in the non-thermal expansion group. This analysis demonstrates that the thermal expansion effect enhances the sealing performance of the gap clearance throughout the entire sealing device from an overall standpoint.

Figure 17.

The relationship between pressure values of thermal expansion group and non-thermal expansion group and speed variation.

The temperature rise effect of the magnetic fluid sealing device is intensified by increasing rotational speed, as illustrated in Figure 13, subsequently imposing multiple thermal influences on key components including magnetic fluid materials, rotating shaft, and pole shoes. Parameters such as material thermal expansion characteristics, magnetization properties, and fluid viscosity are altered with temperature variations. Consequently, temperature serves as a critical factor that continuously affects the sealing performance of magnetic fluid seals.

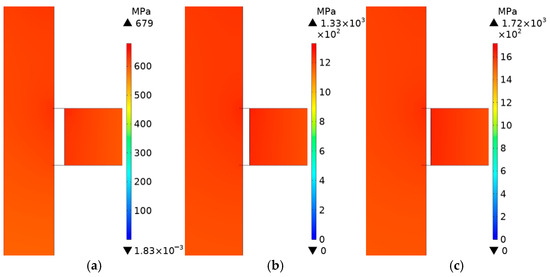

5. The Influence of Materials on Thermal Expansion

According to reference [15], sealing performance is influenced not only by rotational speed and temperature but also by the materials used for the shaft and pole shoe. Therefore, two additional materials, No. 10 steel and 20Cr13, were selected for comparative analysis with the previously employed materials. Both No. 10 steel and 20Cr13 are available in the COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2 built-in material library and can be directly accessed. However, certain parameters for 20Cr13 must be specified separately: density is 7750 kg·m−3, thermal conductivity is 22.2 W·m−1·K−1, specific heat capacity at constant pressure is 460 J·kg−1·K−1, and thermal expansion coefficient is 12.2 × 10−6 K−1.

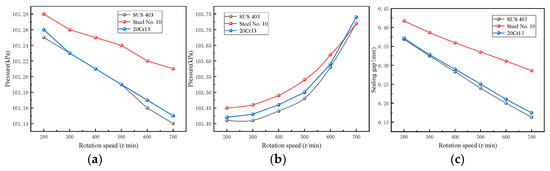

Both the shaft and pole shoes were configured using the same material, with SUS 403 being selected for the analysis as previously mentioned, as illustrated in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

The relationship between parameter values and rotational speed under different materials. (a) Pressure varies with rotational speed; (b) The pressure of the thermal expansion group varies with the rotational speed; (c) The sealing gap varies with the speed.

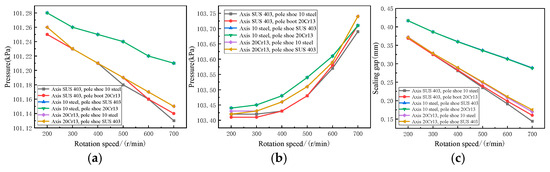

The material combinations of shaft and pole shoe were analyzed using SUS 403, No. 10 steel, and 20Cr13 materials, as illustrated in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

The relationship between parameter values and rotational speed under different material combinations of shaft and pole shoes. (a) Pressure varies with rotational speed; (b) The pressure of the thermal expansion group varies with the rotational speed; (c) The sealing gap varies with the speed.

Based on Figure 18 and Figure 19, several key findings were observed regarding the relationship between material selection and operational parameters. The pressure was found to decrease with increasing rotational speed regardless of the materials chosen for the shaft and pole shoe, while the thermal expansion group pressure increased with higher rotational speeds. Additionally, the sealing gap was observed to decrease as rotational speed increased. Research revealed that when different combinations of No. 10 steel and 20Cr13 were used for the shaft and pole shoe materials, the variation patterns of pressure, thermal expansion group, and sealing gap remained nearly identical. However, when SUS 403 was employed for the shaft while No. 10 steel and 20Cr13 were used for the pole shoe, slight differences in these variation patterns were noted. Figure 19 demonstrates that these differences become more pronounced at higher rotational speeds. A comparison between Figure 18 and Figure 19 indicates that changes in pressure and thermal expansion group values are influenced by the shaft material selection. Nevertheless, when optimal material combinations are selected for both the shaft and pole shoe, enhanced sealing performance may be achieved.

Although a higher rotational speed reduces the viscosity of the magnetic fluid—this in turn raises the temperature of the sealing device, causes radial displacement of the rotating shaft, and narrows the sealing gap—it still improves the sealing effect to some degree. However, the reduction in the sealing gap may cause mutual friction between the rotating shaft and the pole teeth. Therefore, choosing the appropriate material can enhance the sealing effect. In future research, the quantitative relationship among the material, the displacement caused by thermal expansion and the sealing effect can be considered.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- In magnetic fluid sealing, the thermal power of the magnetic fluid does not increase with the increase in rotational speed. When it reaches a certain value, it shows a downward trend and then reaches a stable value. Therefore, the temperature of the system will also reach a certain value.

- (2)

- The rotating shaft will undergo radial displacement due to thermal expansion, but the pole tooth structure basically remains in its original position.

- (3)

- The increase in the temperature of the sealing device enhances the sealing effect to a certain extent.

- (4)

- The reduction in the sealing gap may cause mutual friction between the rotating shaft and the pole teeth. Therefore, through the study of different combinations of three materials for the rotating shaft and the pole shoe, it was found that when the rotating shaft and the pole shoe are made of different materials, the sealing effect may be better.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L.; Methodology, W.Z.; Validation, X.L.; Formal analysis, H.W.; Investigation, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Sichuan International Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation Project—Design and Performance Research of Magnetic Fluid Seals for Large-Diameter High-Speed Centrifugal Compressors (2024YFHZ0338).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhaoqiang Yan was employed by the company Zigong Zhaoqiang Sealing Products Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The physical meanings represented by the physical symbols in this paper (arranged in the order of appearance):

| Physical quantity | The meaning of physical quantities |

| : | denotes the radial components of the magnetic field on the cylinder |

| : | denotes the radial components of the magnetic field on the cylinder |

| : | denotes the radial components of the magnetic field on the cylinder |

| : | represents the magnetic field intensities in the radial directions |

| : | represents the magnetic field intensities in the axial directions |

| : | refers to the radial components of the magnetization intensity |

| : | refers to the axial components of the magnetization intensity |

| : | represents the magnetic fluid density |

| : | denotes the magnetic fluid velocity |

| : | indicates the pressure gradient applied to the magnetic fluid |

| : | stands for the temperature-dependent fluid viscosity |

| : | refers to the Kelvin force |

| : | represents the permeability of free space |

| : | denotes the magnetization intensity |

| : | denotes the magnetic field intensity |

| : | stands for the pressure resistance of a single pole tooth |

| : | represents the rate of change in thermal energy |

| : | represents the difference in internal energy between fluid flowing in and out during the flow process |

| : | represents the heat conduction of the fluid |

| : | represents the work performed by the fluid |

| : | represents the irreversible mechanical dissipation work caused by fluid viscosity |

| : | viscous dissipated |

| : | represents the shaft radius |

| : | pole shoe radius |

| : | denotes the total length of the magnetic fluid along the axial direction |

| : | represents the linear velocity of the shaft |

| R1: | stands for the thermal resistance of convective heat transfer between the magnetic fluid and the pole shoe |

| R2: | denotes the thermal resistances of the pole shoe |

| R3: | denotes the thermal resistances of the housing |

| R4: | stands for the thermal resistance of convective heat transfer between the housing and air |

| C1: | corresponds to the heat capacities of the rotating shaft |

| C2: | corresponds to the heat capacities of the permanent magnet |

| t1: | refers to the magnetic fluid temperature distant from the housing temperature |

| ta: | refers to the magnetic fluid temperature distant from the ambient temperature |

| tfi: | represents the temperature of each wall surface |

| t0: | magnetic fluid temperature |

| : | heat conduction through flat walls |

| : | stands for the mean radius of the surface of the cylindrical wall |

| : | denotes the thickness of the cylindrical wall surface |

| : | indicates the axial length of the cylindrical wall surface |

| : | refers to the thermal conductivity |

| : | convective heat transfer thermal resistance |

| : | represents the surface heat transfer coefficient of the material |

| : | represents the surface heat transfer coefficient of the contact area between fluid and solid |

| : | denotes the heat transfer power for the upper sections |

| : | denotes the heat transfer power for the lower sections |

| : | represents the surface heat transfer coefficient |

| : | the heat flux density constant for a unit length of cylindrical pipe |

| : | the temperature distribution on the cylindrical wall of the pole shoe |

| : | the relationship between temperature and thermal expansion |

| : | represents the thermal expansion coefficient of the material |

| : | denotes the current temperature of the material |

| : | thermal energy |

| : | denotes the specific heat capacity of the magnetofluid |

| : | represents the thermal conductivity coefficient |

References

- Zhou, J.; Fan, H.; Shao, C. Experimental study on the hydrodynamic lubrication characteristics of magnetofluid film in a spiral groove mechanical seal. Tribol. Int. 2016, 95, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczch, M. Magnetic fluid seal critical pressure calculation based on numerical simulations. Simulation 2020, 96, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Bao, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, J. Design and experiment of a large gap rotating seal structure based on nanomagnetic liquid. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2025, 77, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Q.; Qing, J.; Li, X.; Yang, C.; He, X.; Zhao, Y. A Double-Rotating Ferrofluid Vane Micropump with an Embedded Fixed Magnet. Actuators 2024, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Li, D.; Ge, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, X. Numerical and experimental investigation of magnetic fluid sealing under high-speed conditions. Vacuum 2025, 239, 114366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Qi, Z.; Li, D. The sealing pressure variance originated from volume of ferrofluids in magnetic fluid seal. Tribol. Int. 2024, 200, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A. Study of ferrofluid flow in a rotating system through mathematical modeling. Math. Comput. Simul. 2020, 178, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yang, X.; Gao, S.; Chen, Y. Numerical study on key parameters of ferrofluid seal with large gap and two magnetic sources. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Me Chanics 2017, 55, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, J.; Miyanaga, N. Blood sealing properties of magnetic fluid seals. Tribol. Int. 2017, 113, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, M.; Wen, H.; Du, Y.; Dai, P. Coaxial twin-shaft magnetic fluid seals applied in vacuum wafer handling robot. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2012, 25, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosensweig, R.E. Ferrohydrodynamics; Dover Publications INC: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H. The Influence of the Temperature Rise on the Sealing Performance of the Rotating Magnetic Fluid Seal. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2020, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.; Ramani, V.; Upadhyay, R.V.; Parekh, K. Two stage magnetic fluid vacuum seal for variable radial clearance. Pergamon 2020, 172, 109087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitamura, Y.; Sekine, K.; Okamoto, E. Magnetic fluid seals working in liquid environments: Factors limiting their life and solution methods. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 500, 166293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ni, C.; Li, D. The influence of the thermal expansion on the magnetic fluid sealing performance. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 564, 169996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, J.; Yang, Z. Characteristics of a magnetic fluid seal and its motion in an axial variable seal gap. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2008, 18, 634–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, D. Theoretical Analysis and Experimental Study on the Influence of Magnet Structure on Sealing Capacity of Magnetic Fluid Seal. J. Magn. 2019, 24, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welty, J.; Rorrer, G.L.; Foster, D.G. Fundamentals of Momentum, Heat and Mass Transfer; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, D.; Li, D.; Chen, J.Y.J. Theoretical analysis and experimental study of the characteristics of magnetic fluid seal with a large diameter at high/low temperatures. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2018, 58, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, D.C.; Li, Y.W. Effect of permanent magnet material on failure-pressure of magnetic fluid seal. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, D. Preparation and property research of perfluoropolyether oil-based ferrofluid. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 3607–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).