Optimization of Preparation Process Parameters for HVOF-Sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr Coatings and Study of Abrasive and Corrosion Performances

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Coating Preparation and Experimental Design

2.2. Coating Characterization

2.2.1. Phase Composition Analysis

2.2.2. Morphology and Microstructure Observation

2.2.3. Bond Strength Tests

2.2.4. Microhardness Test

2.2.5. Abrasive Wear Test

2.2.6. Electrochemical Corrosion Test

3. Results and Discussion

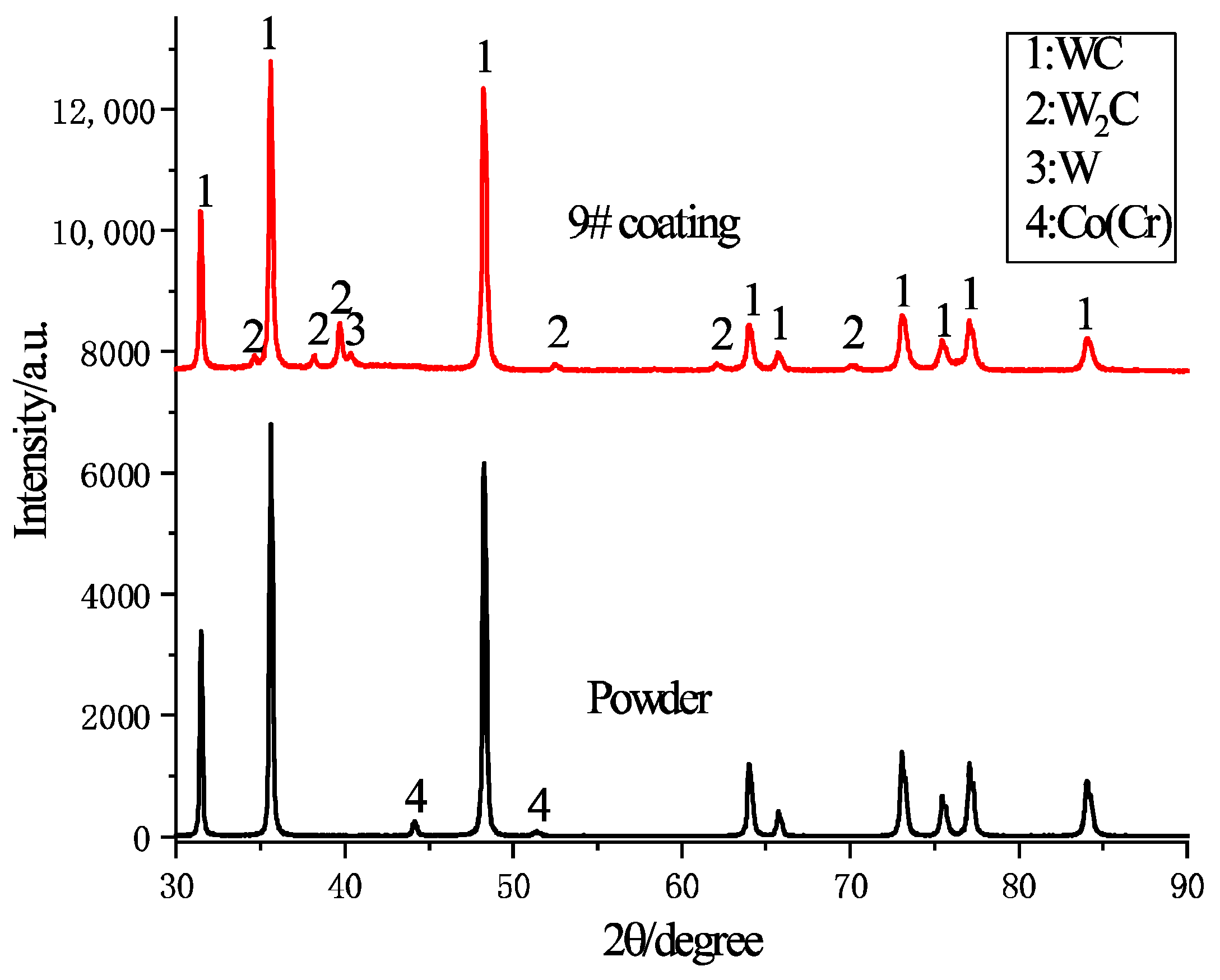

3.1. Phase Composition

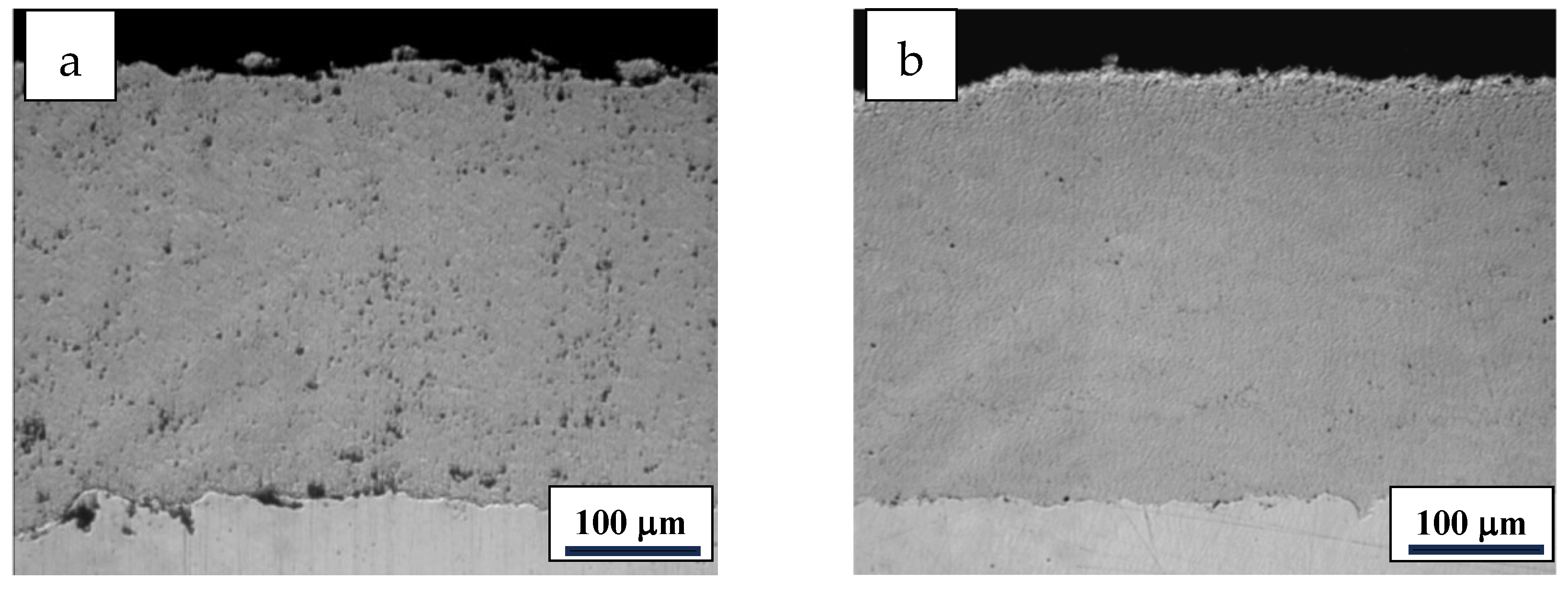

3.2. Cross-Sectional Microstructure

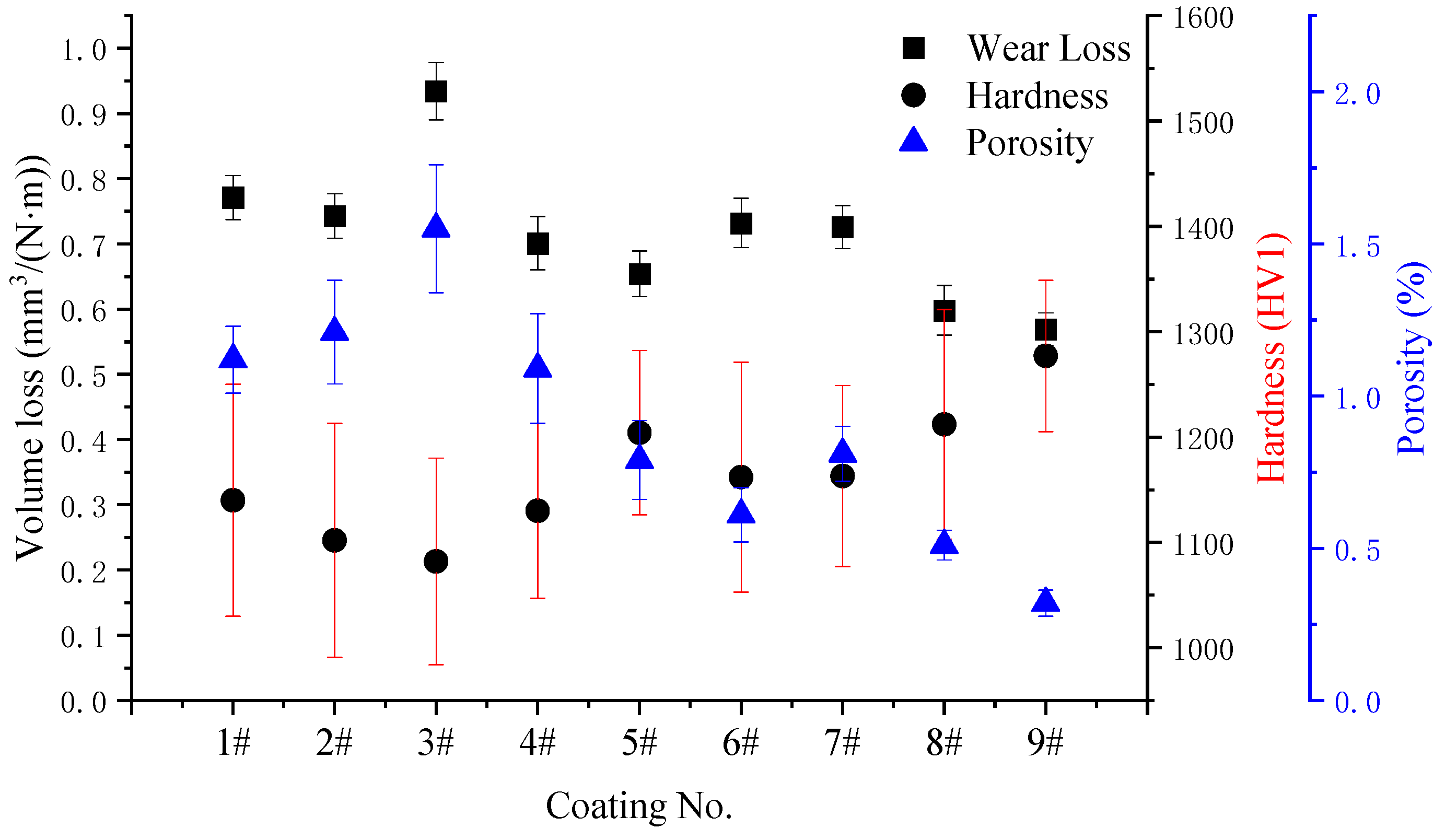

3.3. Influence of HVOF Parameters on Coating Hardness

3.4. Relationship Between Vickers Hardness, Porosity, Abrasive Wear Rate, and Wear Mechanism

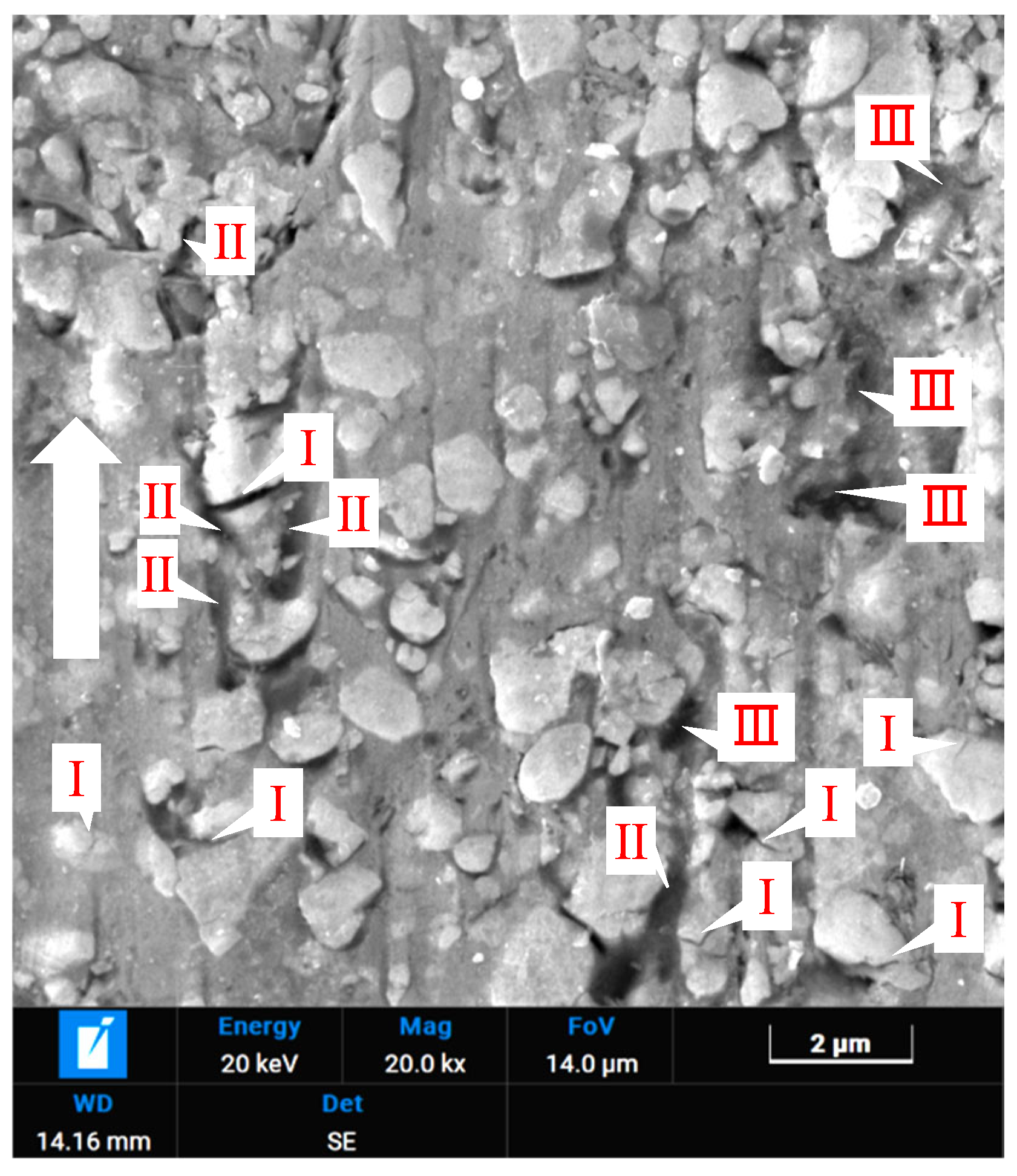

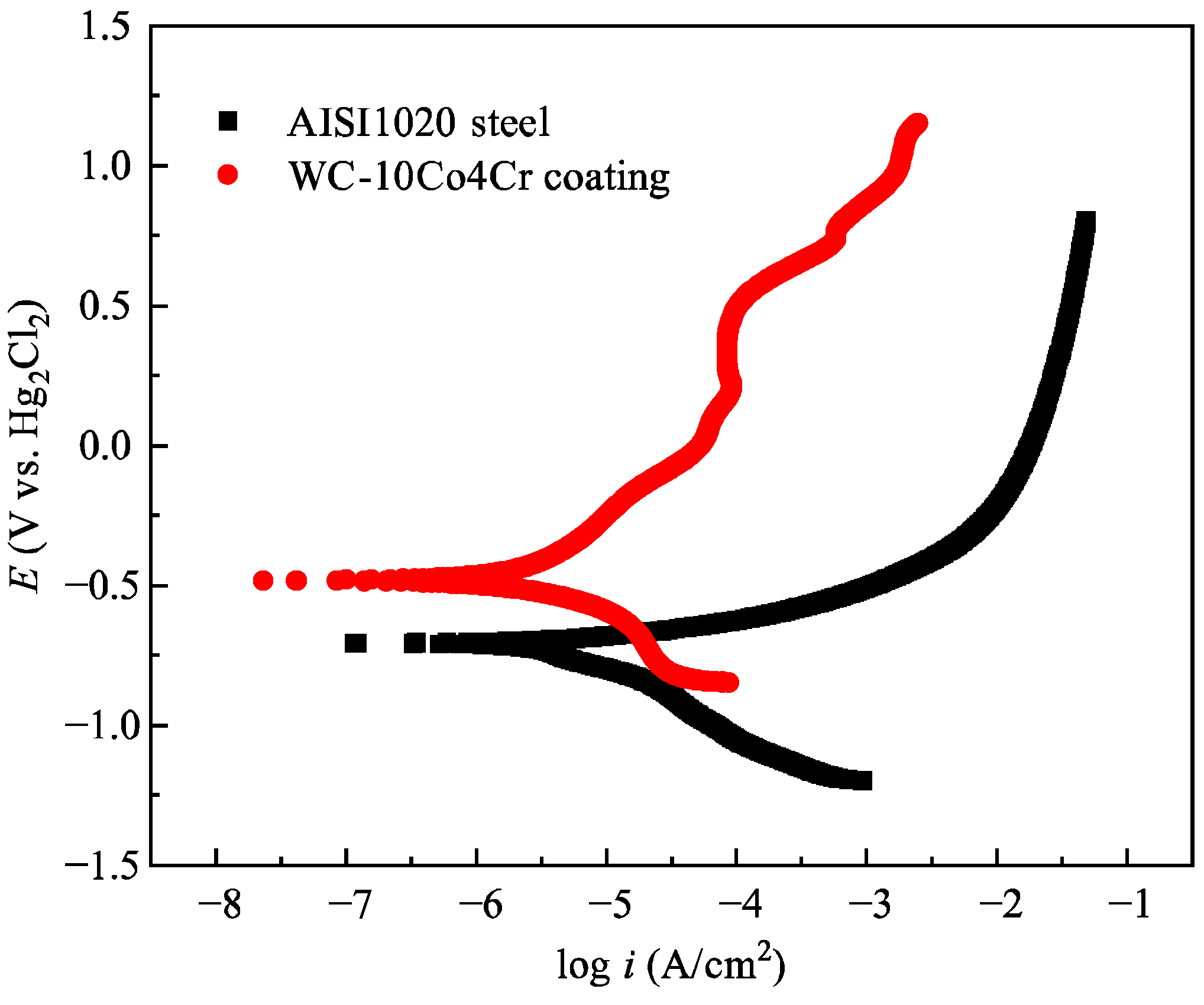

3.5. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior and Mechanism

- (1)

- Pit areas containing corrosion products (marked I, high in W and O): the electrochemical corrosion of HVOF-sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr coatings in NaCl solution is a multi-stage process. It begins with micro-galvanic coupling between WC particles and the CoCr binder phase. The more active CoCr binder acts as the anode, undergoing preferential dissolution (Co → Co2+ + 2e−), accelerated by chloride ions (Cl−). This leads to initial pit formation and weakens the support for WC particles. The exposed WC surface acts as the cathode, facilitating the oxygen reduction reaction (O2 + 2H2O + 4e− → 4OH−), creating a locally alkaline microenvironment within the confined pit. This alkalinity destabilizes WC, leading to its oxidative decomposition into soluble tungstate ions (e.g., 2WC + 4O2 + 2H2O → 2WO42− + 2CO + 4H+), which may subsequently re-deposit as W-rich oxides (e.g., WO3) accumulating inside the pits (Region I) [1].

- (2)

- Relatively flat regions (marked II): These regions contain Co and Cr along with W. The morphology suggests these are Co (Cr) solid solutions. The high Cr content imparts good corrosion resistance, explaining their relatively intact appearance after corrosion.

- (3)

- Bright white annular rings at pit edges (marked III): These bright phases are W2C and W formed from decarburization of WC particles during spraying. These phases remain after the surrounding material corrodes.

- (4)

- Deeper pores/holes (marked IV): These may form after the loss of both WC particles and corrosion products, or they may originate from pre-existing large pores in the coating where accelerated pitting corrosion occurred due to trapped electrolyte.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The phase composition of the WC-10Co-4Cr coatings prepared under various parameters remained largely consistent with the initial spray powder, with WC as the predominant phase. The presence of only minor amounts of W2C and trace W phases indicates effective suppression of decarburization and oxidation during the kerosene-fueled HVOF process, demonstrating high phase stability.

- (2)

- Optimization via a four-factor, three-level orthogonal experiment identified the optimal HVOF spray parameters as: kerosene flow rate of 0.0073 L/s, oxygen flow rate of 15.33 L/s, powder feed rate of 1 g/s, and spraying distance of 326 mm. The coating deposited under this optimized condition exhibited a dense microstructure characterized by the highest microhardness of 1281 HV1 and the lowest porosity of 0.32%.

- (3)

- A strong correlation was established between coating hardness, porosity, and wear performance. The microhardness was negatively correlated with both the wear rate and porosity. The dominant wear mechanism involved micro-cutting and ploughing of the binder phase by abrasives, leading to the subsequent loosening and pull-out of WC particles due to insufficient support.

- (4)

- The corrosion mechanism in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution was primarily governed by the electrochemical potential difference between the WC particles and the CoCr binder phase, leading to the formation of micro-galvanic cells. This resulted in the preferential anodic dissolution of the CoCr binder. Chloride ions (Cl−) further accelerated this process by destroying the passive film, ultimately causing destabilization and loss of WC particles and the formation of corrosion pits and surface roughness.

- (5)

- Compared to the AISI 1020 steel substrate, the optimized HVOF-sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr coating demonstrated a remarkable 122-fold improvement in abrasive wear resistance, coupled with superior corrosion resistance, underscoring its significant potential as a protective coating for components operating in synergistic corrosive-wear environments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, R.; Bhandari, D.; Goyal, K. Slurry erosion behaviour of HVOF-sprayed coatings on hydro turbine steel: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1033, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolelli, G.; Berger, L.M.; Börner, T.; Koivuluoto, H.; Lusvarghi, L.; Lyphout, C.; Vuoristo, P. Tribology of HVOF-and HVAF-sprayed WC-10Co4Cr hardmetal coatings: A comparative assessment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 265, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X. Sliding wear and solid-particle erosion resistance of WC-based coatings deposited by high-velocity oxy-fuel spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 407, 126759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.J.K. Tribology of thermal sprayed WC-Co coatings. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2010, 28, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, Q.; Tian, Y.; Yang, C.; Yuan, C.; Ramachandran, C.S. Microstructure and wear performance of CeO2-modified micro-nano structured WC-CoCr coatings sprayed with HVOF. Lubricants 2023, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Bandyopadhyay, P.P. Role of carbide grit size and in-flight particle parameters on the microstructure, phases, and nanoscale properties of HVOF-sprayed WC-12Co coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 484, 130879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudaprasert, T.; Shipway, P.H.; McCartney, D.G. Sliding wear behaviour of HVOF-sprayed WC-Co coatings deposited with both gas-fueled and liquid-fueled systems. Wear 2003, 255, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.K.; Liu, X.B.; Kang, J.J.; Yue, W.; Qin, W.B.; Ma, G.Z.; Wang, C.B. Corrosion behavior of HVOF-sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr coatings in the simulated seawater drilling fluid under the high pressure. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 109, 104338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Xiang, J.; Zhao, X.; Yang, G. Wear and corrosion performance of WC-10Co4Cr coatings deposited by different HVOF and HVAF spraying processes. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 218, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Ramachandran, C.S. Wear, erosion and corrosion resistance of HVOF-sprayed WC and Cr3C2 based coatings for electrolytic hard chrome replacement. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 81, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Li, H. Effect of Cobalt and Chromium Content on Microstructure and Properties of WC-Co-Cr Coatings Prepared by High-Velocity Oxy-Fuel Spraying. Materials 2023, 16, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Wang, N.; Fan, L.; Shang, L.; Yu, L. Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2025, 64, 20240066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Verma, P.K.; Singh, S.; Kapoor, M.; Balu, R. Microstructural characterization and electrochemical behaviour of HVOF sprayed WC-Co-Cr coatings on 316L boiler steel. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 16, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Chen, X.; Deng, Y. Process optimization and performance study of WC-10Co-4Cr coatings prepared by HVOF-sprayed. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 134, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C633-13; Standard Test Method for Adhesion or Cohesion Strength of Thermal Spray Coatings. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM G105-20; Standard Test Method for Conducting Wet Sand/Rubber Wheel Abrasion Test. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM G59-97; Standard Test Method for Conducting Potentiodynamic Polarization Resistance Measurements. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM G102-89; Standard Practice for Calculation of Corrosion Rates and Related Information from Electrochemical Measurements. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Qadir, D.; Sharif, R.; Nasir, R.; Awad, A.; Mannan, H.A. A review on coatings through thermal spraying. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, L.; Ruggiero, G.; Bolelli, G.; Lusvarghi, L.; Morelli, S.; Björklund, S.; Joshi, S. Effect of powder morphology on tribological performance of HVAF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 505, 132090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yin, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, S.; Wen, D.; Wang, G.; Hou, D. Optimisation and wear performance analysis of laser-cladded WC-Fe-based coating. Insight-Non-Destr. Test. Cond. Monit. 2024, 66, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Wu, Y.; Hong, S.; Long, W.; Cheng, J. Wet abrasive wear behavior of WC-based cermet coatings prepared by HVOF spraying. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, Z.; Cha, L. Cavitation and sand slurry erosion resistances of WC-10Co-4Cr coatings. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2015, 24, 2435–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ding, Z.X.; Chen, D. Abrasive wear behavior of WC reinforced Ni-based composite coating sprayed and fused by oxy-acetylene flame. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2009, 16, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinlechner, R.; de Oro Calderon, R.; Koch, T.; Linhardt, P.; Schubert, W.D. A study on WC-Ni cemented carbides: Constitution, alloy compositions and properties, including corrosion behaviour. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2022, 103, 105750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, M.G.; Gant, A.; Roebuck, B. Wear mechanisms in abrasion and erosion of WC/Co and related hardmetals. Wear 2007, 263, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Mehta, A.; Vasudev, H.; Samra, P.S. A review on the design and analysis for the application of Wear and corrosion resistance coatings. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2024, 18, 5381–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Cui, L.; Yang, W.; Ma, G.; Chen, R.; Wang, A. Comparative study on tribocorrosion behavior of hydrogenated/hydrogen-free amorphous carbon coated WC-based cermet in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2024, 227, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coating No. | Kerosene Flux (L/s) | Oxygen Flux (L/s) | Feed Rate (g/s) | Spraying Distance (mm) | Hardness (HV1) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 0.0063(A1) | 14.13(B1) | 1(C1) | 326(D1) | 1148 ± 110 | 1.12 ± 0.11 |

| 2# | 0.0063(A1) | 15.33(B2) | 1.25(C2) | 353(D2) | 1098 ± 111 | 1.21 ± 0.17 |

| 3# | 0.0063(A1) | 16.53(B3) | 1.5(C3) | 380(D3) | 1061 ± 98 | 1.55 ± 0.21 |

| 4# | 0.0068(A2) | 14.13(B1) | 1.25(C2) | 380(D3) | 1139 ± 83 | 1.09 ± 0.18 |

| 5# | 0.0068(A2) | 15.33(B2) | 1.5(C3) | 326(D1) | 1219 ± 78 | 0.79 ± 0.13 |

| 6# | 0.0068(A2) | 16.53(B3) | 1(C1) | 353(D2) | 1187 ± 109 | 0.61 ± 0.09 |

| 7# | 0.0073(A3) | 14.13(B1) | 1.5(C3) | 353(D2) | 1148 ± 86 | 0.81 ± 0.09 |

| 8# | 0.0073(A3) | 15.33(B2) | 1(C1) | 380(D3) | 1205 ± 109 | 0.51 ± 0.05 |

| 9# | 0.0073(A3) | 16.53(B3) | 1.25(C2) | 326(D1) | 1281 ± 72 | 0.32 ± 0.04 |

| k1 (hardness) | 1102.3 | 1145.0 | 1180.0 | 1216.0 | ||

| k2 (hardness) | 1181.7 | 1174.0 | 1172.7 | 1144.3 | ||

| k3 (hardness) | 1211.3 | 1176.3 | 1142.7 | 1135.0 | ||

| Range (hardness) | 109.0 | 31.3 | 37.3 | 81.0 | ||

| Order of Influence | A > D > C > B | |||||

| Optimal Level and Combination (hardness) | 0.0073(A3) | 16.53(B3) | 1(C1) | 326(D1) | ||

| k1 (porosity) | 1.29 | 1.01 | 0.75 | 0.74 | ||

| k2 (porosity) | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.88 | ||

| k3 (porosity) | 0.55 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 1.05 | ||

| Order of Influence | 0.75 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||

| Optimal Level and Combination (porosity) | 0.0073(A3) | 16.53(B3) | 1(C1) | 326(D1) | ||

| Specimen | OCP (V) | Ecorr (V) | Icorr (A/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AISI 1020 steel | −0.70 | −0.71 | 6.37 × 10−6 |

| WC-10Co-4Cr coating | −0.35 | −0.48 | 2.46 × 10−6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ramachandran, C.S. Optimization of Preparation Process Parameters for HVOF-Sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr Coatings and Study of Abrasive and Corrosion Performances. Lubricants 2025, 13, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120516

Liu T, Li J, Li H, Liu J, Huang Y, Wang Q, Ramachandran CS. Optimization of Preparation Process Parameters for HVOF-Sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr Coatings and Study of Abrasive and Corrosion Performances. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120516

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Tao, Jiajun Li, Haifeng Li, Jianwu Liu, Yueyu Huang, Qun Wang, and Chidambaram Seshadri Ramachandran. 2025. "Optimization of Preparation Process Parameters for HVOF-Sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr Coatings and Study of Abrasive and Corrosion Performances" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120516

APA StyleLiu, T., Li, J., Li, H., Liu, J., Huang, Y., Wang, Q., & Ramachandran, C. S. (2025). Optimization of Preparation Process Parameters for HVOF-Sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr Coatings and Study of Abrasive and Corrosion Performances. Lubricants, 13(12), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120516