Abstract

An operational test and degradation analysis of a hydraulic fluid based on synthetic esters was performed in three types of work machines. To enhance its performance, ZDDP anti-wear agents were added. Hydraulic fluids are susceptible to degradation by oxidation; therefore, to ensure the long service life of the equipment, it is essential to monitor their current condition through laboratory analyses during machine operation. Emission spectrometry was used to determine the presence of contaminants and the concentration of additive substances in the oil. Pollution was assessed by cleanliness code analysis according to ISO 4406-2021, alongside Total Acid Number (TAN) analysis and LNF analysis of wear and contamination in lubricants. The combination of cleanliness code analysis and LNF analysis of particle type and origin allows for monitoring not only the count but also the origin of contaminating metallic particles, which increases the probability of correct diagnostics and successful detection and resolution of wear problems. All three machines were still operational at the end of the test interval, meaning the tested hydraulic fluid is a suitable alternative to mineral variants. However, in all three pieces of equipment, it is necessary to replace the hydraulic fluid and flush the system before further operation. Furthermore, we recommend replacing the filter elements and inspecting the internal spaces of rotating parts with an increased potential for wear. From the oil’s perspective, it is advisable to add more anti-wear additives (ZDDP), which are depleted the fastest.

1. Introduction

The technical equipment used in agriculture, forestry, and near water sources must meet strict criteria, especially biological degradability [1]. Thus, it is advisable to use alternatives to petroleum-based products. Commonly used mineral transmission–hydraulic oils can be replaced by ecological alternatives, which have higher biodegradability and, in the event of undesirable leaks, reduce the risk to the environment and groundwater. The most frequent causes of accidents are hose defects and leaking hose couplings, with a 50% share [2]. However, ecological hydraulic fluids must meet stringent requirements to be qualitatively comparable to conventional mineral oils.

The basic requirements for an environmentally acceptable hydraulic fluid are not only high biodegradability and low ecotoxicity, but also that the fluid’s performance guarantees satisfactory operation in the most demanding hydraulic components. However, to present good performance over long periods of operation, the physico-chemical properties of the fluid must remain stable. These properties include good performance at high and low temperatures, oxidation stability, thermal stability, shear stability, wear protection, demulsibility, low foaming tendency, and good filterability [3]. Bio-hydraulic oils have better rheological properties compared to mineral oils, thanks to a lower temperature–viscosity dependence and viscosity index [2].

To ensure these requirements are met, there are special technical standards for ecological hydraulic fluids, as Müller-Zermani states “There are many eco-labels and standards for environmental-compatible hydraulic fluids. Most of them are based on the international standard ISO 15380 [4]”. Ecological hydraulic fluids can be divided into four basic groups: HETG (composed of vegetable triglycerides), HEPG (consisting of polyglycols), HEPR (composed of polyalphaolefins and related substances), and the HEES we used (hydraulic fluid based on synthetic esters).

Like all existing esters, the esters used as lubricants and hydraulic fluids are made up of condensed acids and alcohols. The wide availability of both alcohols and acids with one, two, or more functional groups is the reason for one of the most important properties of ester products: their versatility [5].

The application of ecological fluids, including in heavy machinery, was also studied by [6,7,8]. The measurement of parameters in hydraulic circuits using sensors was studied by [9]. Hydraulic fluids must transfer energy as economically as possible, although it is well known that in most hydraulic systems, the efficiency does not exceed 75%. In this case, the input power is spent on overcoming mechanical friction, pressure losses in pipelines, valves, and fittings, and internal leakage of the hydraulic fluid [10]. Piston pumps are widely favored, particularly in heavy machinery and in the backhoe loaders included in our study. A piston pump is a positive displacement pump that can be classified into three main categories, namely, radial piston pumps, bent-axis piston pumps, and swash plate axial piston pumps [11].

Axial piston pumps are common because their design allows them to vary their geometric displacement, and thus, the flow rate in the hydraulic system, without changing their rotational speed. They have an odd number of pistons arranged in a circular array within a housing that is commonly referred to as a cylindrical block, rotor, or barrel. The cylinder block is driven to rotate about its axis of symmetry by a central shaft, aligned with the pumping pistons [11]. Hydraulic pumps need to provide varying degrees of hydraulic fluid volumetric flow and pressure to the rams to generate the necessary force to extend and retract the bucket, dipper arm, and boom against a given load; hence, torque can vary [12]. The work cycle of the piston chamber in an axial piston pump consists of the suction and discharge processes of hydraulic fluid. The reason for hydraulic fluid leakage in the pump is a large pressure difference between the piston chamber and the casing. Volume losses occur when liquid is forced into the pressure line [10]. These hydraulic pumps require high-quality hydraulic oil with good lubricating properties because the piston’s movement within the cylinder involves metal-on-metal contact, which can lead to undesirable friction and the generation of wear particles. One of the major causes of premature wear on machine parts, moving or working under load on the contact surface, is the practice of improper lubrication. This includes contamination with foreign particles, the use of improper lubricants, and the use of lubricants in excessive quantities or in insufficient quantities [13].

If wear particles are already present, capturing them with a filter is essential for the machine’s lifespan. However, not all particles are trapped, and these can then act as additional abrasive particles, accelerating damage. To detect their presence, we employ methods such as cleanliness code analysis and LNF analysis. One of the key elements in lubricant analysis is the ISO Code [14]. This code for solid contaminants expressly accounts for the purity levels of liquids and is internationally recognized [13]. Although measuring contamination is an important aspect, contaminants cause equipment failure, but not necessarily fluid failure [15]. It is important to address fluid contamination, as it causes the majority of hydraulic system failures [16]. Proper filtration can mitigate this problem (Contamination Control in Hydraulic Systems). Changes in fluid composition can arise from an increase in metallic particles due to wear, as well as from the depletion of additives formulated into the hydraulic fluid.

Spectrometry is a technique for quantification that uses the emission or absorption of light from a sample. Its goal is the determination of concentrations; it differs from qualitative analysis by its use of spectra, which is commonly referred to as spectroscopy [17,18]. In terms of the total number of samples processed, atomic emission spectroscopy is perhaps the most widely used oil analysis technique. Atomic emission spectroscopy is extensively employed because it permits simultaneous measurement of ppm concentrations of wear metals, contaminants, and additives in oil samples [19]. Since no two elements have the same pattern of spectral lines, the elements can be differentiated via spectroscopy. The intensity of the emitted light is proportional to the quantity of the element present in the sample, allowing the concentration of that element to be determined [19,20].

In addition to fluid contamination by particles and additive depletion, it is also important to monitor changes in acidity, specifically the Total Acid Number (TAN), which is a direct indicator of fluid aging. An increasing TAN is an indicator of fluid degradation. The aging during the use of hydraulic oil causes a deterioration in oil quality, i.e., changes in oil viscosity, acid number, and anti-wear properties, a growing trend towards the build-up of deposits on system components, and an increasing particulate matter content [21].

The goal of this research was to make the operation of backhoe loaders more environmentally friendly because these devices operate in areas near freshwater sources.

2. Materials and Methods

Tests of a hydraulic fluid, applied in hydraulic circuits, were performed on the following backhoe loaders:

- ➢

- JCB 4CX;

- ➢

- CAT 444 F2;

- ➢

- CASE 695 ST.

The operational test was set for 1000 engine hours, based on the hydraulic fluid change interval. Operational tests on all three tractor backhoes were conducted during normal working activities to ensure real-world load conditions. The test cycle was standardized and consisted of repetitive work operations typical for these machines: digging and loading material (full load on the hydraulic system), material transport and travel (medium load), and idling and maneuvering (low load).

This cycle was consistently repeated throughout the entire 1000-engine-hour test interval. The oil temperature in the hydraulic circuit was continuously monitored using external sensors to ensure it remained within the normal operating range, which is crucial for evaluating oil degradation. This procedure ensured the repeatability and comparability of conditions for all tested machines.

The operational test was divided into 4 phases of 250 engine hours each. At these intervals, 2 dcl fluid samples were taken (one for each interval) using a sampling pump directly from the oil tank and subjected to laboratory analysis. Before taking samples, the machine was operated for 15 min. The sample at 0 mh was extracted from the hydraulic circuit, not from the container.

Before the actual start of the test, the hydraulic circuit of the handling equipment was flushed with the same type of oil as that used during the tests, so almost no amount of the previous oil was present. New hydraulic filters were installed in the hydraulic circuits, but the hydraulic pumps and cooling liquids remained the same. The basic technical parameters of the hydraulic circuits of the individual backhoe loaders are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Backhoe loader hydraulic circuit parameters.

2.1. Shell PANOLIN S2 Hydraulic DU EAL 46

In the hydraulic circuits of the JCB 4CX, CAT 444 F2, and CASE 695 ST backhoe loaders, the hydraulic fluid Shell Panolin S2 Fluid, produced from a base of readily biodegradable synthetic esters, was used. The choice of fluid was made based on guidance from the service companies supplying the backhoe loaders. They also insisted on adding more anti-wear agents, so the oil was enriched with a ZDDP additive at a concentration of 2 dcl in 100 liters of hydraulic fluid. The authors acknowledge that top-treating an EAL fluid with a ZDDP additive may compromise its final classification as an EAL under certain international standards due to the content of zinc and phosphorus. However, this step was taken based on the explicit recommendation of the service company to ensure sufficient wear protection for the heavy-duty hydraulic systems of the tested machinery. This decision was made as a pragmatic operational measure based on the explicit recommendation of the service company responsible for the machinery’s maintenance. Given the high operational hours of the machines (4500–7100 Eh) and the demanding nature of their work cycles, the priority was to ensure maximum protection of high-value components, such as the axial piston pumps, against premature wear. The addition of ZDDP was therefore considered a necessary precaution to guarantee the reliability and longevity of the equipment throughout the 1000 h test interval.

The basic characteristic properties of the biodegradable hydraulic fluid Shell Panolin S2 Fluid are shown in Table 2. This oil was also tested by [1] with positive results.

Table 2.

Basic characteristic properties of Shell PANOLIN S2 Hydraulic DU EAL 46 [22].

2.2. Analysis of Fluid Degradation Processes

During the operational test of the plant-based biodegradable hydraulic fluid, the basic physical and chemical properties of the fluid, and/or their changes, were monitored. Each sample analysis was performed in triplicate to ensure the repeatability of the results. All data presented in the tables and graphs represent the average values from these measurements. The error bars in the graphs represent the standard deviation from the mean. The statistical significance of the differences was assessed based on non-overlapping error bars.

2.2.1. RDE—OES (Rotating Disc Electrode–Optical Emission Spectrometry)

A fundamental analysis of degradation processes, or, more specifically, the fluid contamination process, involves monitoring the chemical elements contained in the hydraulic fluid. For this analysis, a SPECTROIL Q100 (Spectro Scientific, Chelmsford, MA, USA) atomic emission spectrometer with a rotating disc electrode was used. The SPECTROIL Q100 can analyze up to 31 elements simultaneously, including wear metals and contaminants. In our work, it was used to monitor the wear of the machinery by monitoring contaminant particles and to determine the presence of additive particles, both in mg·kg−1. Measurements were carried out according to the standard ASTM D6595 [23].

2.2.2. Cleanliness Code According to ISO 4406-2021

To measure the cleanliness code according to ISO 4406-2021 [14], the Hydac CS 1320 device (Sulzbach/Saar Germany) shown in Figure 1 was used, with the analysis sample consisting of 1 L of hydraulic fluid.

Figure 1.

Hydac CS 1320 device.

2.2.3. LNF Analysis

LNF analysis refers to the use of LaserNet Fines® (LNF) technology to analyze wear and contamination in lubricants. For the LNF analysis of the hydraulic fluid samples, the LNF-C analyzer shown in Figure 2 was used. Using a laser particle counter, information was obtained about the current condition of the hydraulic fluid and the wear status of the equipment. The instrument identifies particles up to 100 µm in size and, based on their shape, classifies them by their origin as cutting, sliding, fatigue, and potentially non-metallic particles. Measurements were carried out according to the ASTM D7596 standard [24].

Figure 2.

LNF-C analyzer.

2.3. Analysis of Physical Properties

During operational tests of biodegradable fluids in the hydraulic circuits of the backhoe loaders, the following physical properties were monitored:

- ➢

- Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and 100 °C;

- ➢

- Acid number (TAN).

2.3.1. Kinematic Viscosity Analysis

To measure kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and 100 °C, the Spectro VISC Q300 viscometer (Spectro Incorporated, Littleton, MA USA) shown in Figure 3 was used, according to the ASTM D445 standard [25]. The measuring range of the viscometer is from 0.6 to 3000 mm2·s−1. The operating temperature is from 20 to 110 °C. The temperature stability is ±0.01 °C. The analysis process begins by injecting a sample of less than 1 mL in volume into the measuring tube. Before the sample enters the capillary, it is heated to the bath temperature. The Spectro VISC Q300 consists of a thermostatic bath with a circulating system and a control unit. The bath contains 4 viscometer tubes with optical sensors for determining the oil flow through all tubes.

Figure 3.

Spectro VISC Q300 viscometer.

2.3.2. Analysis of Acid Number (TAN)

To analyze the acid number in hydraulic fluid samples, the FluidScan Q1000 device (Spectro Scientific, Chelmsford, MA, USA) shown in Figure 4 was used, according to the ASTM D664 standard [26]. The FluidScan Q1000 analyzer is designed based on an optical system that uses specific, fixed spectral bands for oil analysis. The acid number (TAN—Total Acid Number) is a measure of the amount of acidic components in a hydraulic oil sample. The acid number is defined as the amount of potassium hydroxide (KOH) in milligrams that is required to neutralize the acidic components in one gram of a sample. Regular monitoring of the acid number is an important part of an oil analysis program and helps prevent hydraulic system failures and optimize maintenance intervals.

Figure 4.

FluidScan Q1000.

2.4. Operational Tests

The operational tests on all three backhoe loaders lasted 1000 engine hours. At intervals of 250 engine hours, samples of the transmission–hydraulic fluid were taken, which were subjected to laboratory analyses.

2.4.1. Analysis of Degradation Processes

The basic analysis of the degradation processes of the hydraulic fluid was based on the depletion of additive elements in the fluid samples and the process of fluid contamination by various chemical elements. The analysis monitored the depletion process of the following additive elements:

- ➢

- Calcium (Ca);

- ➢

- Magnesium (Mg);

- ➢

- Zinc (Zn);

- ➢

- Phosphorus (P).

Additive element depletion during the operational test was determined as follows:

where

O0—concentration of chemical elements at 0 engine hours;

O250—concentration of chemical elements at 250 engine hours.

2.4.2. Analysis of the Fluid Contamination Process

In the analysis of the contamination process of the hydraulic fluid, all chemical elements that represent the contamination process (detected during the analysis) were monitored. These included aluminum (Al), boron (B), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), potassium (K), molybdenum (Mo), sodium (Na), silicon (Si), tin (Sn), and titanium (Ti).

The increase in chemical elements representing fluid contamination was calculated as follows:

where

Z0—concentration of chemical elements at 0 engine hours;

Z250—concentration of chemical elements at 250 engine hours.

3. Results

This section shows the results of the measurements, and it is divided into two subsections: the results of the particle analysis and the results of the physical properties of the hydraulic fluids. Note that the particle analysis was performed after mixing the base oil with ZDDP anti-wear agents, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Elements present in Shell Panolin S2 hydraulic oil after adding additives but before adding it to the machines.

3.1. Particle Analysis

The particle analysis included tests of the additive element deception process, contamination process, analysis of the cleanliness code, and classification of wear particles by the LaserNet Fines Test.

3.1.1. Additive Element Depletion Process

This test identified the concentrations of various elements present in the hydraulic fluid in the three tested machines, as shown in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Additive element depletion process—JCB 4CX (concentration in mg·kg−1).

Table 5.

Additive element depletion process—CAT 444 F2 (concentration in mg·kg−1).

Table 6.

Additive element depletion process—CASE 695 ST (concentration in mg·kg−1).

The concentration of calcium in all three applications of the transmission–hydraulic oil decreases. Calcium is a common component of detergents and dispersants. The decrease in concentration is natural and indicates the consumption of this additive as it performs its function. Calcium (as a detergent/dispersant) is consumed during the neutralization of acids and when keeping impurities in suspension.

Magnesium is also often used as a component of detergents and dispersants, similar to calcium. Here, too, we observe gradual depletion. Magnesium (also a detergent/dispersant) is also gradually depleted. The percentage decrease is milder than that of calcium.

Phosphorus is a key component of anti-wear (AW) and antioxidant additives added into oil, most commonly in the form of ZDDP (zinc dialkyldithiophosphate). Its decrease indicates the consumption of this protective additive. The percentage decrease is the highest among Ca and Mg, which may reflect the degree of wear and oxidative stress.

Zinc, like phosphorus, is a main component of ZDDP. Its percentage decrease is the most significant among the monitored additives. This strong depletion of zinc (and phosphorus) is an important indicator that the anti-wear and antioxidant protection of the oil significantly decreases with increasing hours of operation. The percentage decrease in zinc and phosphorus differs across all three hydraulic circuits. This is interesting because phosphorus and zinc are bound together in ZDDP. The difference in percentage decrease could be caused by different behaviors of the individual ZDDP components or analytical variations, but both elements clearly show a trend of anti-wear protection depletion. A differing rate of decrease could suggest that, in some cases, zinc is released from another source, compensating for ZDDP consumption. All monitored elements (Ca, Mg, P, Zn) show a decreasing concentration with an increasing number of engine hours, confirming that these are consumable additives in the oil.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Contamination Process

In the analysis of the contamination process of the hydraulic fluid, all chemical elements that represent the contamination process (detected during the analysis) were monitored. These included aluminum (Al), boron (B), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), potassium (K), molybdenum (Mo), sodium (Na), silicon (Si), tin (Sn), and titanium (Ti). The results for three machines are in Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9.

Table 7.

Concentration of contaminating elements—JCB 4CX (concentration in mg·kg−1).

Table 8.

Concentration of contaminating elements—CAT 444 F2 (concentration in mg·kg−1).

Table 9.

Concentration of contaminating elements—CASE 695 ST (concentration in mg·kg−1).

In the complex contamination element analysis, we see an increase in every element in every device.

A huge increase in tin is observed in all three pieces of equipment during the first interval of 250 engine hours. Tin typically originates from bearings. Similar to copper and iron, an extremely high increase indicates very significant wear of tin-containing bearings throughout the entire monitored period, but especially during run-in.

Copper shows a significant increase in concentration in all three cases. Copper most often originates from the bearings or the oil cooler. An extremely high increase indicates very significant wear of copper-containing components throughout the entire monitored period.

The concentration of iron increases by more than 400% in the first and third pieces of equipment; in the CAT 444 F2 machine, it starts at 2.63 mg·kg−1 and significantly rises to 7.62 mg·kg−1 at 1000 engine hours. The overall increase for CAT 444F2 is only 189%. Iron is the main indicator of wear for most steel engine components. Similar to copper, an extremely high increase indicates very significant wear of these components throughout the entire monitored period.

Chromium is a typical wear element (rings, liners, valves). A more than 180% increase in the second case indicates significant wear of these components over 1000 engine hours.

The concentration of potassium fluctuates in all cases. Potassium indicates contamination by the coolant, i.e., externally. A relatively stable concentration with slight fluctuations and a very low overall increase suggests that no significant continuous potassium contamination occurs during this period. However, in the case of the CAT 444 F2 machine, we observe an increase of 462.50%. An extremely high percentage increase (similarly in the CASE 695 ST), even from a low initial value, indicates significant potassium contamination, most often from the coolant or external sources.

The concentration of sodium may indicate a gradual deterioration of cooling system seals or another source of contamination in the case of the CASE 695 ST machine, where it increases by 605%. In absolute numbers, the increase is not large, but this may be a warning for the operator to check the tightness of the cooling system.

Silicon is the main indicator of contamination by dust/dirt. A more than 100% increase suggests continuous ingress of impurities into the oil system, probably through the air intake system. This is a significant indicator of potential abrasive wear. The initial value in the CASE 695 ST machine is relatively high, suggesting that the oil is already contaminated at the beginning or there is a high rate of continuous dust ingress.

3.1.3. Analysis of Cleanliness Code

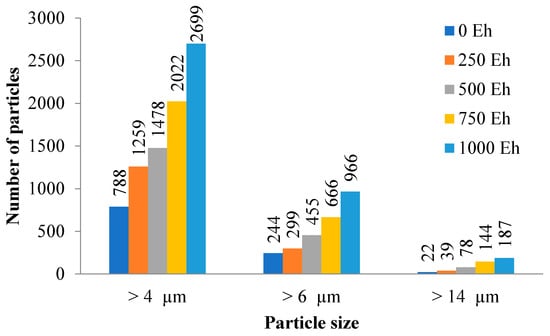

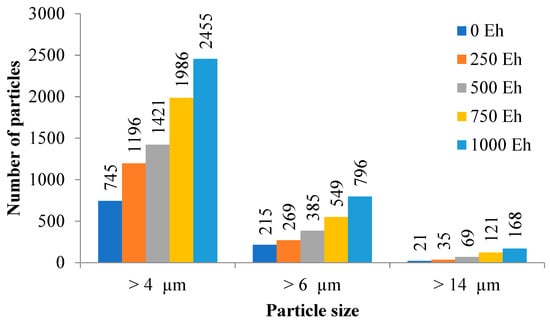

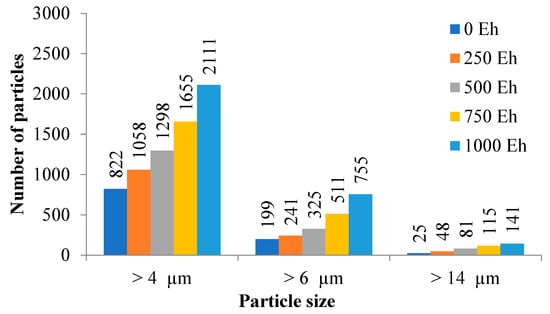

The analysis of the cleanliness code, as shown in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, determined the number of particles with respect to their sizes at various times during the testing cycle.

Figure 5.

Wear particle count according to ISO 4406-2021—JCB 4CX.

Figure 6.

Wear particle count according to ISO 4406-2021—CAT 444 F2.

Figure 7.

Wear particle count according to ISO 4406-2021—CASE 695 ST.

The trend for the smallest monitored particle size category (>4 μm) shows a clear and significant increase in the number of particles with each subsequent interval of engine hours for all three tested machines. In the first case, for the JCB 4CX machine, the particle count nearly triples from 0 to 1000 engine hours. This increase is typical and reflects the continuous generation of fine wear particles and the accumulation of small contaminants that the filter does not capture. Larger particles (>6 μm) are more abrasive, and their increasing number is a direct indicator of wear. The increase in the number of larger particles (>6 μm and >14 μm) is particularly important and indicates the ongoing generation of abrasive and fatigue particles in the system. For the largest monitored particles (>14 μm), we see a significant and progressive increase in all cases throughout the entire 1000 engine hours.

The absolute counts are the lowest, but these are the particles most responsible for serious abrasive wear. The percentage increase is the highest, which indicates that the filter is not sufficiently effective at removing these larger particles, or their generation is so intense that it exceeds the filtration/sedimentation capacity. The absolute numbers of larger particles are the lowest, but their percentage increase and impact on wear are significant, as they have a higher potential to cause abrasive wear. All cleanliness codes of the tested machines are shown in Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12.

Table 10.

Cleanliness code according to ISO 4406-2021—JCB 4CX.

Table 11.

Cleanliness code according to ISO 4406-2021—CAT 444 F2.

Table 12.

Cleanliness code according to ISO 4406-2021—CASE 695 ST.

3.1.4. Classification of Particles by the LaserNet Fines Test

While the previous analyses quantified the total number of particles by their size and chemical composition, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15 indicate how these particles are formed, which helps to identify specific wear mechanisms.

Table 13.

Classification of wear particles by the LaserNet Fines Test—JCB 4CX.

Table 14.

Classification of wear particles by the LaserNet Fines Test—CAT 444 F2.

Table 15.

Classification of wear particles by the LaserNet Fines Test—CASE 695 ST.

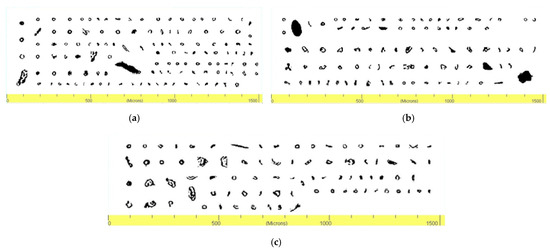

The number of cutting particles significantly increases with operating hours. This increase is direct evidence of active abrasive wear throughout the entire monitored period. The presence of cutting particles confirms the conclusions from the previous analyses regarding a high level of silicon (Si) contamination, as dust/sand particles are a typical source of abrasive wear, which precisely generates these cutting particles.

The number of fatigue particles gradually increases throughout the entire 1000 engine hours. Fatigue particles indicate fatigue wear, which may be related to stress on rolling bearings or gears. Their increasing number can signal a gradual deterioration in the condition of these components.

The number of sliding particles in all three backhoe loaders initially increases slowly, with a more significant increase occurring around the 500-engine-hour mark. Sliding particles are related to sliding or adhesive wear. The increase after 500 engine hours could correlate with a more significant depletion of anti-wear additives (P, Zn). When the level of ZDDP (zinc dialkyldithiophosphate) is lower, the protection of sliding surfaces is less effective, which can lead to an increase in adhesive wear. The increase in Fe and Cu in the previous analyses also supports this conclusion, as sliding wear is a major wear mechanism for bearings and some other parts.

The number of non-metallic particles significantly and continuously increases throughout the entire 1000 engine hours, with the highest values in the JCB 4CX machine (98). These particles are primarily an indicator of contamination (dust, soot, oil degradation products). The high and increasing number of non-metallic particles perfectly correlates with the high and increasing silicon (Si) content and the total particle counts from the previous analyses. This confirms that contamination is a serious problem in the tested systems, especially in the JCB 4CX.

Figure 8 shows the LNF analysis of individual samples after the completion of the operational tests.

Figure 8.

LNF analysis of fluid samples after the operational test ((a)—JCB 4CX, (b)—CAT 444, (c)—CASE 695 ST).

3.2. Analysis of Physical Properties

The observed physical properties were kinematic viscosity and its change and the Total Acid Number and its change.

3.2.1. Kinematic Viscosity

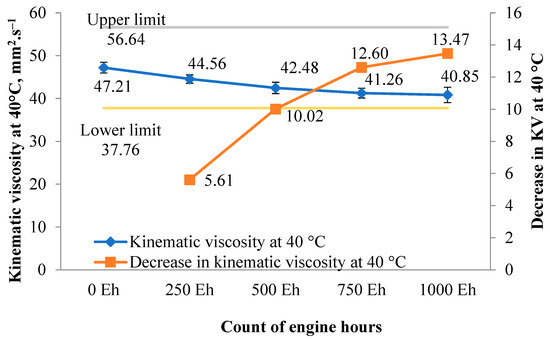

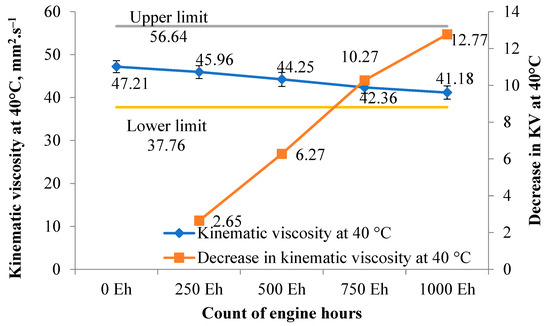

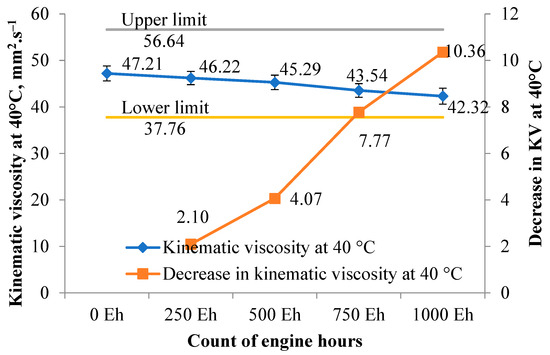

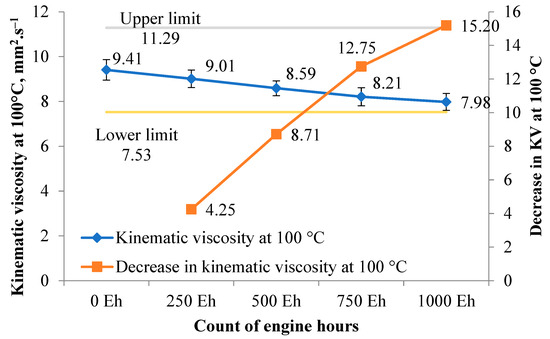

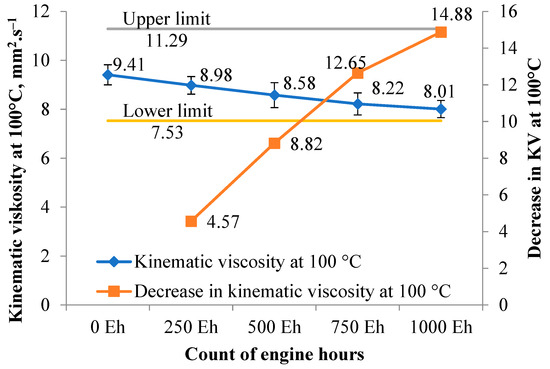

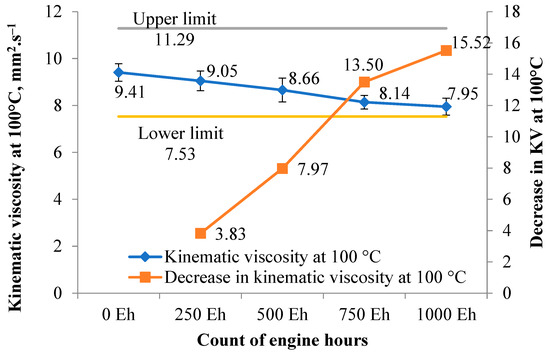

The measurement of kinematic viscosity was carried out according to the ISO 8217 standard [27] at temperatures of 40 °C and 100 °C. Based on the ISO 15380:2023 standard [28], the kinematic viscosity value cannot change by more than 20% compared to the start of the test. These limits and measured values are shown in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 9.

Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and decrease in kinematic viscosity at 40 °C—JCB 4CX.

Figure 10.

Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and decrease in kinematic viscosity at 40 °C—CAT 444.

Figure 11.

Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and decrease in kinematic viscosity at 40 °C—CASE 695 ST.

Figure 12.

Kinematic viscosity at 100 °C and decrease in kinematic viscosity at 100 °C—JCB 4CX.

Figure 13.

Kinematic viscosity at 100 °C and decrease in kinematic viscosity at 100 °C—CAT 444.

Figure 14.

Kinematic viscosity at 100 °C and decrease in kinematic viscosity at 100 °C—CASE 695 ST.

Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C gradually decreases with increasing engine hours in all the tested backhoe loaders. Throughout the entire operational test, the kinematic viscosity at 40 °C remains within permissible limits in all cases. From these findings, it is evident that during the operational test of the hydraulic fluid, the limit values for the change in kinematic viscosity at 40 °C, specified in the ISO 15380:2023 standard, were not exceeded.

For comparison, we tested oil viscosity at 100 °C as well.

Kinematic viscosity at 100 °C gradually decreases with increasing engine hours in all the tested backhoe loaders. Throughout the entire operational test, the kinematic viscosity at 100 °C remains within permissible limits in all cases; however, it decreases significantly in the intervals. The limit values for the change in kinematic viscosity at 100 °C, specified in the ISO 15380:2023 standard, were not exceeded.

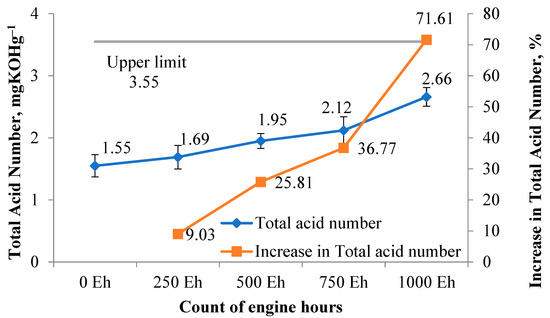

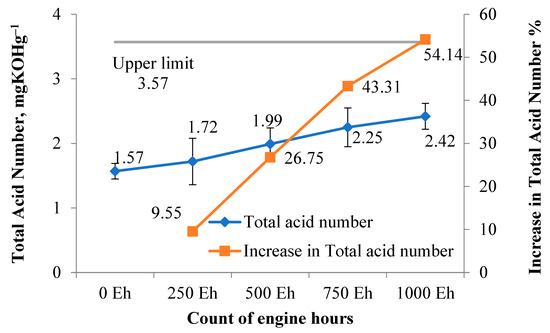

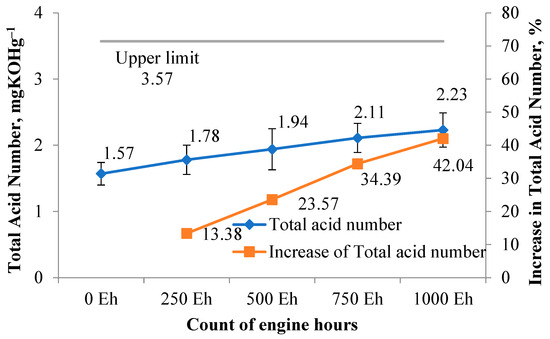

3.2.2. Total Acid Number—TAN

Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17 show the progression of changes in the Total Acid Number (TAN) during the operational test of the hydraulic fluid. Based on the ISO 15380:2023 standard, a maximum increase in the acid number by a value of TAN = 2 mg KOH·g−1 is established.

Figure 15.

Total Acid Number (TAN) and increase in Total Acid Number (TAN)—JCB 4X.

Figure 16.

Total Acid Number (TAN) and increase in Total Acid Number (TAN)—CAT 444.

Figure 17.

Total Acid Number (TAN) and increase in Total Acid Number (TAN)—CASE 695 ST.

The Total Acid Number (TAN) consistently and smoothly increases with increasing engine hours in all the tested hydraulic circuits. An increasing TAN is a natural phenomenon during oil degradation. The oil degrades during operation, and acidic substances accumulate in it. Although the TAN at 1000 engine hours has not yet exceeded the established upper limit in any case, in the JCB 4CX machine, it approaches the upper limit, which indicates that oil degradation is actively occurring.

4. Discussion

The Shell Panolin S2 hydraulic oil performed in all the excavators during the entire planned interval. In this way, it withstood the same load as mineral oils are supposed to withstand. Apart from environmental benefits, according to [2], using bio-oils can reduce fuel costs when operating at correct temperatures. [29] noted that biodegradable oil did not negatively affect the construction of a tractor in his experiment; moreover, it had the potential to increase its lifetime.

Despite the positive performance, the analysis showed some changes in the elemental composition.

A decrease in additives can be explained by their functions. Phosphorus has the tendency to accumulate on the metallic surfaces of the hydraulic circuit, thus protecting them from wear, as an anti-wear agent. Calcium and magnesium serve as detergents and corrosion inhibitors, according to [30]. They can tie up impurities, which are then captured by the filter.

JCB 4CX—specific elements

Most of the monitored elements that are indicators of wear (Fe, Cu, Cr, Sn, Al, Cd, Mo, Ti) and contamination (Si, Na, K, B) showed an increasing trend with accumulating engine hours. The most significant increase in concentration over 1000 engine hours was recorded for Fe (464.75%—from 1.22 to 6.89 mg·kg−1), Cu (374.39%—from 0.82 to 3.89 mg·kg−1), and Sn (395.98%—from 5.22 to 25.89 mg·kg−1). These are critical indicators of the intensive wear of main engine components, especially bearings and parts made of iron/steel. The significant increase in Si (104.80%—from 1.25 to 2.56 mg·kg−1) confirms a problem with dust contamination, which contributes to abrasive wear. The increase in Cr (109.95%—from 2.01 to 4.22 mg·kg−1) indicates wear of chromed parts (rings, liners). The milder, but still present, increases in Al, Cd, Mo, Ti, Na, and B point to the wear of other components and possible sources of contamination.

CAT 444 F2—specific elements

Several key wear elements (Cr, Cu, Fe, Sn) and contamination elements (K, Na, Si, Ti) showed a significant increase in concentration over 1000 engine hours. The highest percentage increase was observed for elements K (462.50%—from 0.08 to 0.45 mg·kg−1), Ti (371.43%—from 0.21 to 0.99 mg·kg−1), Sn (326.37%—from 7.66 to 32.66 mg·kg−1), Na (221.82%—from 0.55 to 1.77 mg·kg−1), Cu (204.96%—from 1.21 to 3.69 mg·kg−1), Fe (189.73%—from 2.63 to 7.62 mg·kg−1), and Cr (185.06%—from 1.74 to 4.96 mg·kg−1). This strongly suggests active wear of components containing these elements (especially bearings, chromed parts, iron/steel parts) and significant contamination, particularly by potassium and sodium (probably from coolant or external sources) and silicon (dust). The increase in titanium from a very low base was also significant.

CASE 695 ST—specific elements

The most significant percentage increases were observed for elements Na (605.00%—from 0.20 to 1.41 mg·kg−1), Sn (561.65%—from 4.12 to 27.26 mg·kg−1), Fe (453.85%—from 1.69 to 9.36 mg·kg−1), Cu (350.32%—from 1.55 to 6.98 mg·kg−1), Mo (170.93%—from 0.86 to 2.33 mg·kg−1), Si (142.82%—from 3.69 to 8.96 mg·kg−1), K (133.33%—from 0.12 to 0.28 mg·kg−1), V (122.35%—from 0.85 to 1.89 mg·kg−1), and Ti (101.59%—from 0.63 to 1.27 mg·kg−1). This strongly indicates serious wear of multiple components and significant contamination. The particularly high increases in Fe, Cu, Sn, Al, and Cd signify the wear of key components, such as bearings and parts of the hydraulic pump. The extremely high increases in Na and K, along with high Si, suggest severe contamination by the coolant and dust. The increases in Ti, V, and Mo may come from specific alloys or other sources of contamination.

Coolants are a mixture of water and glycol (ethylene glycol) with corrosion inhibitors. The presence of elements such as sodium (Na) and potassium (K) in the oil is clear evidence of coolant ingress into the oil. Even if the water from this mixture evaporates in the hot oil, the glycol and chemical additives remain.

The hydraulic fluid in the JCB 4CX backhoe loader exhibits some signs of degradation and contamination. Although some limits of the ISO 15380:2023 standard have not yet been strictly exceeded (viscosity, TAN increase), the observed trends (significant wear, high contamination, depletion of key additives, approaching the lower viscosity limit) suggest that the fluid is at the end of its service life in terms of ensuring optimal system protection and should be replaced. A similar development of physical and chemical properties of hydraulic fluids during operation has also been described in previous studies [31,32]. Continuing operation with such degraded and contaminated fluid would lead to accelerated wear of system components [32].

The additive consumption results indicate the following:

Additives, especially those crucial for anti-wear and antioxidant protection that we added to the base oil (Zn and P as part of ZDDP), were significantly depleted (Zn decreased by 55.75%—from 89.56 to 39.63 mg·kg−1; P decreased by 32.75%—from 22.47 to 15.11 mg·kg−1). ZDDP forms a thick film on rubbing surfaces, thereby protecting them [33]. After losing ZDDP, the fluid loses its ability to protect metal surfaces from direct contact. A similar depletion of ZDDP additives and its impact on the degradation processes of hydraulic fluids was also observed in [34].

The intensive component wear results indicate the following:

Elements indicating wear (Fe, Cu, Sn, Cr) reached higher concentrations after 1000 h (e.g., Fe increased by 464.75%—from 1.22 to 6.89 mg·kg−1, Cu increased by 374.39%—from 0.82 to 3.89 mg·kg−1, Sn increased by 395.98%—from 5.22 to 25.89 mg·kg−1, and Cr increased by 109.95%—from 2.01 to 4.22 mg·kg−1). The values of Tin are especially alarming and suggest the rapid and intensive wear of critical parts of the transmission and hydraulic system. Increased concentrations of wear metals were similarly documented in [31], which mentioned the negative impact of degraded fluid on component lifespans.

High level of contamination: The increase in silicon (Si by 104.80%—from 1.25 to 2.56 mg·kg−1) is an indicator of considerable ingress of dust particles into the system. According to [35], dust contaminants significantly contribute to abrasive wear in hydraulic systems, especially with failing seals or filtration. In combination with the high levels of wear metals and the presence of cutting particles (according to LaserNet Fines), this confirms that abrasive wear caused by contamination is the main degradation mechanism.

Deteriorating cleanliness code: The gradual worsening of the cleanliness code (from 17/15/12 to 19/17/15) indicates a failing filtration system. A similar trend was also recorded by [36], who demonstrated a link between deteriorating filtration and accelerated growth of wear particles.

Classification of wear particles: The analysis of particle types (LaserNet Fines) confirms the dominance of abrasive wear (cutting particles), directly related to Si contamination. Adhesive/sliding wear (sliding particles) showed an increase after 500 h, which correlated well with the depletion of anti-wear additives. The presence of fatigue particles signals material fatigue on loaded surfaces. The combined occurrence of different particle types as an indicator of the wear mechanism was also confirmed by [37].

Kinematic viscosity decreased, although it remained within standard limits.

The acid number (TAN) rose smoothly and relatively quickly (increase of 71.61%), confirming ongoing oxidative degradation of the fluid. The nominal limit of change was not yet exceeded, but the trend indicates that the reserve for acid neutralization is diminishing. The rising TAN values, as a predictor of the approaching end of fluid life, are consistent with the findings of [32].

It is necessary to identify and eliminate sources of dust/dirt contamination (e.g., by checking system air filters and seals) and consider more effective filtration solutions to extend fluid life and protect expensive system components in the future. These recommendations are consistent with the findings of [36], who highlighted the importance of preventive maintenance and effective filtration when working with biodegradable hydraulic fluids. Continuing operation without corrective measures would likely lead to a rapid deterioration in the machine’s condition and potential failures.

The hydraulic fluid used in the CAT 444 F2 backhoe loader showed fewer signs of degradation than that used in the JCB 4CX backhoe loader, but some of the analysis results indicate potential problems with longer-term operation. Despite relatively stable levels of the main additives (Zn, P, Ca), we observed gradual component wear, which correlated with increasing fluid contamination. Similar findings with longer operation using hydraulic fluids were also reported by [31]. The degradation processes of the hydraulic fluid applied in the transmission–hydraulic circuit of the CAT 444 F2 backhoe loader are as follows:

Additive degradation: The additive concentration slightly decreased; the most significant percentage decrease was observed for phosphorus (45.65%—from 23.66 to 12.86 mg·kg−1), which indicates substantial depletion of anti-wear and antioxidant protection. Although the decrease in zinc was milder, together with the decrease in phosphorus, it signals a weakening of additive protection. Simultaneously, however, there was an increase in the content of wear metals and contamination, which attests to weakened protection under certain conditions. Such development is also described by [34], who pointed out that normal additive values may not always guarantee sufficient protection.

The contamination and wear results indicate the following:

High percentage increases in Cr, Cu, Fe, and Sn confirm active wear of the system’s metallic components (bearings, chromed surfaces, steel parts). The increase in tin is particularly significant and points to bearing wear. These values do not yet indicate an alarming state but point to ongoing abrasive wear. Such a type of wear in hydraulic fluids was also described in the work by [32], where an increase in metals was correlated with micro-oxidative changes on metal surfaces.

The increase in silicon confirms the ingress of dust and impurities into the system. According to [35], even a slight increase in silicon during long-term operation can cause cumulative wear of bearings and sealing surfaces.

Fluid cleanliness worsened in all the monitored particle size categories (17/15/12 => 18/17/15). This increase in the number of solid particles is consistent with the results of the chemical analysis of contamination and confirms an increased rate of wear particle generation and ingress of contaminants into the fluid. The increasing number of larger particles (>6 μm and >14 μm) is particularly critical, as these particles cause the most severe abrasive wear.

Caterpillar chose ISO 17/15/13 [38] cleanliness as the minimum cleanliness requirement for the oil used to factory fill Caterpillar machines. This requirement is intended to be applied only to new oil, not to oil that has been or is currently used in a Caterpillar hydraulic system [38].

Particle classification (LaserNet Fines): We observed an increase in the number of cutting, fatigue, and especially sliding particles. The significant increase in non-metallic particles (>1000%) again underscores the problem with system contamination. The findings regarding the occurrence of combined wear with hydraulic fluids are also supported by the results of the study by [37].

Kinematic viscosity: Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C consistently decreased. Although it did not exceed the permissible limits according to ISO 15380:2023, it approached the lower limit. Decreasing viscosity can reduce the load-bearing capacity of the lubricating film and increase wear, especially at higher temperatures.

Acid number (TAN): The TAN rose smoothly, confirming the accumulation of acidic products of oil degradation. Although the value did not yet exceed the established limit for increase (2 mg KOH/g compared to the initial value), the upward trend is clear and signals ongoing oil degradation.

Although the change in the physical properties of the hydraulic fluid aligns with expectations during its gradual degradation, the wear particle levels indicate that physical parameters alone may not be sufficient to assess the actual condition of the fluid—which was also pointed out by [36].

Given the increasing contamination and the presence of wear particles, we recommend checking and replacing the filtration system, revising seals, and introducing LNF and contaminant screening at shorter intervals. Such an approach is consistent with recommendations from the literature [36], which emphasizes the importance of continuous monitoring during machine operation in demanding environments.

The transmission–hydraulic fluid in the CASE 695 ST circuit underwent degradation after 1000 engine hours, and the system showed signs of considerable wear and contamination.

The additive degradation results indicate the following:

There was a decrease in the concentrations of key additives such as calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and phosphorus (P), which provide the detergent, dispersant, and anti-wear/antioxidant properties of the fluid. Particularly, the significant decrease in phosphorus (35.32%—from 22.45 to 14.52 mg·kg−1) signals substantial depletion of anti-wear protection (ZDDP). Qu [39] mentioned that ZDDP can form deposits, and it is precisely for this reason that we may observe less of it in the oil sample. This decrease indicates a significantly reduced ability of the fluid to provide protection against wear and oxidation, which is consistent with observations in the study by [31], where rapid additive degradation was linked to operational load and contamination. The same phenomenon was also observed by [34], who showed that after the loss of additives, tribological failures in hydraulic systems develop rapidly.

The component wear and contamination results indicate the following:

The high increases in iron (Fe by 453.85%—from 1.69 to 9.36 mg·kg−1), copper (Cu by 350.32%—from 1.55 to 6.98 mg·kg−1), and tin (Sn by 561.65%—from 4.12 to 27.26 mg·kg−1) clearly indicate severe wear of key components, such as bearings, pistons, bushings, and parts of the hydraulic pump/motor. The increases in molybdenum (Mo), titanium (Ti), and vanadium (V) may attest to the wear of other alloyed parts. Particularly, the increased iron content is indicative of intensive abrasive wear. Such results are consistent with data from the study by [32], where similar iron concentrations were associated with the formation of cracks and micro-pitting on metal surfaces.

The high increases in sodium (Na by 605.00%—from 0.20 to 1.41 mg·kg−1) and potassium (K by 133.33%—from 0.12 to 0.28 mg·kg−1), along with the high increase in silicon (Si by 142.82%—from 3.69 to 8.96 mg·kg−1), according to Evans [30], attest to contamination by the coolant (Na, K) and dust/dirt (Si). This contamination can contribute to abrasive wear.

The deterioration of fluid cleanliness according to ISO 4406-2021 from 17/15/12 to 18/16/14 confirms that the fluid contains more solid particles, which increases the risk of abrasive wear. In the study by [35], similar development was linked to an inappropriate service interval and leakage through seals, which may also be the case for this machine.

Classification of wear particles (LaserNet Fines): The analysis of particle morphology confirmed the presence and increasing number of cutting, fatigue, and sliding particles, which is consistent with high concentrations of wear metals. The increase in non-metallic particles (>60 at 1000 h) was also significant. A significant representation of cutting and sliding particles indicates combined wear in an advanced stage. According to [37], such particles are formed mainly through the synergistic action of abrasive and adhesive wear—which leads to irreversible damage to hydraulic components.

Kinematic viscosity: Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C dropped to the lower limit according to ISO 15380:2023.

Acid number (TAN): The TAN gradually increased, which is a normal process of fluid aging associated with the formation of acidic products of oxidation and degradation. Although the percentage increase was considerable (42.04%), the absolute TAN value at the end of the test did not exceed the standardized limit, suggesting that the oil, to some extent, retained its ability to neutralize acids. An increased TAN can signal oxidation of the oil base and the formation of acidic degradation products—similar to what was documented by [36], where a TAN above 1.0 mg KOH·g−1 was associated with a reduced system lifespan.

As evident from the graphs (Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17), the observed changes in the physical properties of the fluid, such as kinematic viscosity and acid number, were statistically significant over the course of the test, which is confirmed by the non-overlapping error bars for the initial and final measurements. This consistent and statistically demonstrable change confirms the ongoing degradation processes.

Based on these results, it can be concluded that 1000 engine hours in this particular operational circuit led to a deteriorated state of the fluid and system, which would urgently require replacement of the hydraulic fluid and in-depth diagnostics and potential repairs of worn components, especially those that are sources of high concentrations of Fe, Cu, Sn, Al, and Cd. It is also crucial to identify and eliminate the sources of contamination (ingress of dust and coolant) to prevent a recurrence of this state with a new fluid fill. This approach also corresponds to the recommendations of authors [36,37] who emphasized the need for an adaptive service approach when fluid quality deteriorates.

5. Conclusions

An operational test of a hydraulic fluid with anti-wear additives applied in the transmission–hydraulic circuits of three backhoe loaders, namely, JCB 4CX, CAT 444 F2, and CASE 695 ST, was performed. The operational tests were set for 1000 engine hours, and at intervals of 250 engine hours, fluid samples were taken from the backhoe loaders for laboratory analyses.

All observed values (TAN, viscosity, purity code, LNF) were within limit values. In terms of contamination particles, we observed multiple fast increases, indicating possible wear problems.

In the JCB 4CX machine, the fluid was at the end of its service life after the test interval, and it is essential to replace it before further operation. Additionally, it is necessary to inspect the loaded parts of the hydraulic circuit, as high contamination with wear particles indicates that components may be damaged. The concentration of iron increased during the tests by 464.75%, to 6.89 mg·kg−1. The absolute value is not huge, but the increase indicates wear.

The CAT 444 F2 backhoe loader exhibited significant abrasive wear after the test interval. The values of tin increased by 356.37% to 32.66 mg·kg−1, which was caused by system contamination. To eliminate the cause, it is necessary to change the hydraulic oil, perform a system flush, and replace the filter elements in the cleaner.

The CASE 695 ST machine was extremely contaminated with metallic tin, increasing by 561.65% to 27.36 mg·kg−1. Sodium was present in the circuit as well, which increased in concentration by 605% to 1.41 mg·kg−1, probably originating from the coolant. For further operation, it is necessary to replace the hydraulic–transmission fluid and check the tightness of the oil cooler and the moving elements of the hydraulic system.

The SHELL Panolin S2 hydraulic oil with anti-wear additive passed the tests, and all the machines were able to perform their tasks even after the test interval. However, the rapid loss of additive concentration prompts machine operators to correctly replenish additives to ensure the long-term performance of this hydraulic fluid.

After these tests, the owner of the devices agreed to use this type of hydraulic fluid in his backhoe loaders as a suitable alternative appropriate for use near freshwater sources.

One of the key aspects of this study was the use of an EAL fluid additionally additized with a zinc-and-phosphorus-based ZDDP additive. Although this practice, as recommended by a service company, was intended to enhance wear protection in demanding operating conditions, its impact on the fluid’s environmental profile must be critically evaluated. The presence of ZDDP can limit the ultimate biodegradability and increase ecotoxicity of the oil, meaning the resulting mixture may not meet all the criteria for the EAL designation. This situation highlights a common industrial trade-off between maximizing component protection and adhering to strict environmental requirements. Therefore, future research could focus on a direct comparison of the performance and degradation processes of the base EAL fluid with and without the additional ZDDP additization. Such a study would quantify the benefits of the extra wear protection while also assessing the environmental compromises, which would be a valuable contribution for operators of heavy machinery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.T., J.K. and J.J.; methodology, Z.T. and J.K.; validation, Z.T. and J.T.; formal analysis, G.Č., J.K. and S.D.; investigation, M.N. and J.K.; resources, M.N.; data curation, J.K. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.T., J.K. and D.S.; writing—review and editing, J.T. and G.Č.; visualization, J.K. and D.S.; supervision, Z.T.; project administration, Z.T. and J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Visegrad Funds, No. 52410187.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank the editor and reviewers for their valuable comments that improved the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Michalides, M.; Čorňák, Š.; Jelínek, J.; Janoušková, R.; Hujo, L.; Nosian, J. Degradation of Ecological Energy Carriers Under Cyclic Pressure Loading. Acta Technol. Agric. 2023, 26, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuster, S.; Schmitz, K. Bio-Based Hydraulic Fluids and the Influence of Hydraulic Oil Viscosity on the Efficiency of Mobile Machinery. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaff, Y.; De Negri, V.J.; Theissen, H.; Murrenhoff, M. Analysis of the influence of contaminants on the biodegradability characteristics and ageing of biodegradable hydraulic fluids. Stroj. Vestn. J. Mech. Eng. 2014, 60, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Zermani, B.; Gaule, G. Environmental approach to hydraulic fluids. Lubr. Sci. 2013, 25, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondioli, P. Lubricants and Hydraulic Fluids; Sheffield Academic Press: Sheffield, UK, 2001; pp. 331–343. [Google Scholar]

- Tkáč, Z.; Čorňák, Š.; Kosiba, J.; Janoušková, R.; Michalides, M.; Vozárová, V.; Csilag, J. Investigation of degradation of ecological hydraulic fluid. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2021, 235, 7925–7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučera, M.; Drmla, J.; Aleš, Z. Comparative Experimental Investigation of Environmentally Non-Hazardous Rapeseed Oils Using Technical Reliability Indicators. Acta Technol. Agric. 2025, 28, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.G.; Kim, J.K.; Na, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Hong, S.H. Application of condition monitoring for hydraulic oil using tuning fork sensor: A study case on hydraulic system of earth moving machinery. Materials 2022, 15, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque-Sarmiento, D.A.; Baño-Morales, D.A. Assessment of Hydraulic Oil Properties during Operation of a Mini Loader. Lubricants 2024, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhutin, M.G.; Khanh, G.Q.; Krivenko, A.E.; Van Heip, T. Evaluation of the influence of the hydraulic fluid temperature on power loss of the mining hydraulic excavator. J. Min. Inst. 2023, 261, 374–383. [Google Scholar]

- Bergada, J.M.; Kumar, S.; Watton, J. Axial piston pumps, new trends and development. Fluid Dyn. Mech. Appl. Role Eng. 2012, 10, 1–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, F.; Harding, J.A.; Glass, J. An eco-approach to optimise efficiency and productivity of a hydraulic excavator. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3966–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebensian, G.; Salem, N.; Bogdan, S. The lubricants’ parameters monitoring and data collecting. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 184, 03008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- ISO 4406:2021; Hydraulic Fluid Power—Fluids—Method for Coding the Level of Contamination by Solid Particles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.[Green Version]

- Livingstone, G.; Cavanaugh, G. The real reasons why hydraulic fluids fail. Tribol. Lubr. Technol. 2015, 71, 44. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Novak, N.; Trajkovski, A.; Kalin, M.; Majdič, F. Degradation of Hydraulic System due to Wear Particles or Medium Test Dust. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nölte, J. ICP Emission Spectrometry: A Practical Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry—Analytical Chemistry Division. Nomenclature, symbols, units and their usage in spectrochemical analysis—III. Analytical flame spectroscopy and associated non-flame procedures. Pure Appl. Chem. 1976, 45, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, T.; Henning, P.; Velasquez, A.; Saskia, J.; Michael, P. Detection of Abnormal Wear Particles in Hydraulic Fluids via Electromagnetic Sensor and Particle Imaging Technologies; Spectro Scientific: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saba, C.S.; Rhine, W.E.; Eisentraut, K.J. Efficiencies of sample introduction systems for the transport of metallic particles in plasma emission and atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1981, 53, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczewski, K.; Szczawiński, P. Investigation of the process of ageing of hydraulic oil during its use. Arch. Motoryz. 2016, 73, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shell PANOLIN S2 Hydraulic DU EAL 46, Technical Data Sheet; Shell: 17.7. 2023. Available online: https://www.lubritec.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/FT-SH-Shell-PANOLIN-S2-Hydraulic-DU-EAL-46-eng.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- ASTM D6595; Standard Test Method for Determination of Wear Metals and Contaminants in Used Lubricating Oils or Used Hydraulic Fluids by Rotating Disc Electrode Atomic Emission Spectrometry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D7596; Standard Test Method for Automatic Particle Counting and Particle Shape Classification of Oils Using a Direct Imaging Integrated Tester. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D445; Standard Test Method for Kinematic Viscosity of Transparent and Opaque Liquids (and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D664; Standard Test Method for Acid Number of Petroleum Products by Potentiometric Titration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ISO 8217:2024; Products from Petroleum, Synthetic and Renewable Sources—Fuels (Class F)—Specifications of Marine Fuels. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 15380:2023; Lubricants, industrial oils and related products (class L)—Family H (Hydraulic systems)—Specifications for Hydraulic Fluids in Categories HETG, HEPG, HEES and HEPR. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Tkáč, Z.; Čorňák, Š.; Cviklovič, V.; Kosiba, J.; Glos, J.; Jablonický, J.; Bernát, R. Research of Biodegradable Fluid Impacts on Operation of Tractor Hydraulic System. Acta Technol. Agric. 2017, 20, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S. Where Does All That Metal Come from? Wear Check Africa, Set Point Group: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, L.; Eason, R.W.; Clarke, D. Tribological performance and oxidative stability of biodegradable hydraulic oils in field conditions. Lubricants 2023, 11, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Thermal Oxidative Degradation Characteristics of Environmentally Friendly Hydraulic Fluids. Lubricants 2023, 11, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Spikes, H. The history and mechanisms of ZDDP. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 17, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcicki, T.; Michalak, M.; Dąbrowski, J. Degradation and monitoring of biodegradable hydraulic fluids in agricultural machinery. Agron. Res. 2019, 17, 552–560. [Google Scholar]

- Šmak, M.; Królikowski, A.; Piekoszewski, W. Effect of solid particle contamination on the wear of hydraulic pump components. Tribol. Int. 2015, 90, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Lu, Y. Failure analysis and preventive maintenance of hydraulic systems using oil condition monitoring. Energies 2021, 14, 6932. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, A.; Chawla, V. Particle morphology analysis for wear mechanism identification in hydraulic systems. Wear 2022, 498–499, 204304. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, I.S.; Totten, G.E.; De Negri, V. Biodegradable hydraulic fluids. In Handbook of Hydraulic Fluid Technology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2011; pp. 319–362. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J.; Luo, H.; Chi, M.; Ma, C.; Blau, P.J.; Dai, S.; Viola, M.B. Comparison of an oil-miscible ionic liquid and ZDDP as a lubricant anti-wear additive. Tribol. Int. 2014, 71, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).