Abstract

We present early follow-up observations of Einstein Probe (EP) X-ray transients, following its first year of operation. EP is a dedicated wide-field X-ray observatory that is transforming our understanding of the dynamic X-ray universe. During its first year, EP successfully detected a diverse range of high-energy transients—including gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), tidal disruption events (TDEs), and fast X-ray transients (FXTs), besides many stellar flares, disseminating 128 alerts in the aggregate. Ground-based optical follow-up observations, particularly those performed by our BOOTES telescope network, have played a crucial role in multi-wavelength campaigns carried out so far. Out of the 128 events, the BOOTES Network has been able to follow up 58 events, detecting 6 optical counterparts at early times. These complementary optical measurements have enabled rapid identification of counterparts, precise redshift determinations (such as EP250215a at ), and detailed characterization of the transient phenomena. The synergy between EP’s cutting-edge X-ray monitoring and the essential optical follow-up provided by facilities, such as the above-mentioned BOOTES Global Network or other Spanish ground-based facilities we have access to, underscores the importance and necessity of coordinated observations in the era of time-domain and multi-messenger astrophysics.

1. Introduction

X-ray transients represent some of the most energetic and dynamic phenomena in the universe, offering unique insights into extreme physics and fundamental astrophysical processes [1,2,3]. These events encompass a diverse range of sources, including tidal disruption events (TDEs), gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), stellar flares, and compact object mergers [4]. While X-ray observations reveal their prompt emission mechanisms, optical follow-up observations play a pivotal role in classifying transients, measuring redshifts, and constraining multi-wavelength energetics. For example, optical spectroscopy provides critical redshift measurements for cosmological GRBs [5], while color evolution in afterglows probes jet dynamics and circumburst environments [3].

The Einstein Probe (EP) mission [6,7] addresses the need for wide-field X-ray monitoring with its unique dual-telescope design: the Wide-field X-ray Telescope (WXT) surveys ∼3600 deg2 per exposure in the 0.5–4 keV band, while the Follow-up X-ray Telescope (FXT) provides rapid (<4 min slewing) deep imaging with a sensitivity of erg cm−2 s−1 in 2 ks [6]. EP employs two trigger systems: (1) onboard triggers for bright events (e.g., GRBs) and (2) ground-processed triggers for fainter transients (e.g., FXTs), leveraging real-time data downlink through the Beidou system [7].

This article focuses on optical follow-up observations conducted by the BOOTES Global Network [8,9,10] for EP transients during its first year of operations. BOOTES comprises seven robotic stations equipped with 0.6 m Ritchey–Chretien telescopes, achieving a slewing speed of 100 deg/s and a pointing accuracy of <5″ [9]. Each telescope utilizes SDSS and WFCAM/VISTA filters, reaching limiting magnitudes of in 300 s exposures [10]. In this work, we analyze the following:

- Time delays between the EP X-ray triggers and our optical observations.

- BOOTES’s observational strategies and site-specific performance.

- Case studies of high-redshift GRBs (e.g., GRB 240315A at ) and outstanding transients (e.g., EP240408a).

The synergy between EP’s rapid localization and the BOOTES network’s robotic response has been demonstrated in multiple events (see Table 1), where BOOTES swiftly carried out optical follow-up observations to complement EP’s X-ray detections. This coordinated effort not only enabled rapid identification of potential afterglows but also paved the way for deeper spectroscopic studies using facilities like the GTC (Gran Telescopio CANARIAS) or VLT (Very Large Telescope), thereby greatly enhancing our understanding of these transient phenomena. Conversely, the absence of optical counterparts for EP240408a down to mag challenges existing models of jetted TDEs [11]. These results highlight how optical follow-up not only complements X-ray data but also drives new theoretical inquiries.

Table 1.

EP alert systems and BOOTES performance [6].

Section 2 details EP’s alert pipelines and BOOTES’s observational protocols (Section 2.1 and Section 2.2) as well as time response statistics and light curves (Section 2.3), while Section 3 discusses the astrophysical implications of key sources. Our findings establish a framework for optimizing transient follow-up in the multi-messenger era.

2. Methods

The transients analyzed in this paper were discovered by Einstein Probe (EP) between 19 February 2024 (the first source EP240219) and 26 February 2025. The data presented in this paper were compiled from various public sources, with a focus on optical follow-up observations conducted by the BOOTES network.

2.1. Data Sources

Our analysis focuses primarily on optical follow-up observations from ground-based facilities, particularly the BOOTES network. Key data sources include the following:

- The GCN (Gamma-Ray Coordinates Network) Circulars, which provide prompt notifications of EP detections, including source coordinates and discovery time (https://gcn.nasa.gov/circulars, accessed on 26 February 2025).

- The Astronomer’s Telegram (ATel) reports, which contain follow-up observations and classification information from various teams (https://www.astronomerstelegram.org, accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Published papers focusing on specific EP sources, providing detailed multi-wavelength analysis and source characterization.

For each transient, we compiled key information such as the following:

- Discovery time and position.

- Multi-wavelength follow-up observations, with a focus on optical data from the BOOTES network.

2.2. BOOTES Network Follow-Up Observations

BOOTES (Burst Observer and Optical Transient Exploring System) is a global network of robotic telescopes designed for rapid response to transient alerts. Its strategic distribution across seven stations enables near-continuous monitoring and follow-up observations of transient astronomical events.

2.2.1. Telescope Network

The BOOTES network consists of seven stations (B1–B7) located across different continents, as shown in Table 2. Each station is equipped with a 0.6 m Ritchey–Chretien telescope, designed with fast-slewing capabilities to respond rapidly to transient alerts.

Table 2.

BOOTES network sites location.

2.2.2. Instrumentation and Observations

BOOTES telescopes are equipped with SDSS , , and WFCAM/VISTA Z and Y filters, along with Andor iXon X3 EMCCD cameras that provide a field of view. These telescopes can initiate observations within minutes of receiving an alert, ensuring timely multi-band photometry to capture the color evolution of transient sources. The limiting magnitudes vary based on telescope and exposure time, with BOOTES-5 reaching mag in a 300 s exposure. The BOOTES network is also equipped with the low-resolution spectrograph COLORES [12] and has demonstrated its versatility in observing diverse optical transients, including gamma-ray bursts and stellar flares. Its rapid slewing capability (<100 deg/s) ensures timely follow-up within critical observational windows.

Data reduction includes standard procedures such as bias subtraction, flat-fielding, and photometric calibration using Pan-STARRS reference stars [13]. Differential photometry is employed to analyze the brightness variations over time.

2.2.3. Response Times and Observational Strategy

The response time for BOOTES observations varies depending on the alert type. Onboard triggers for the brightest transients typically result in faster follow-up observations, while ground-based processed triggers for fainter events may have longer delays. For instance, Stellar flares typically exhibit rapid variability with durations of 1–2 h at most, as evidenced by the multi-wavelength observations of the DG CVn superflare [14]. Monitoring the delay between transient onset and the first observation is crucial for understanding the transient’s early optical behavior.

2.2.4. Spectroscopic Follow-Up with 10.4 m GTC

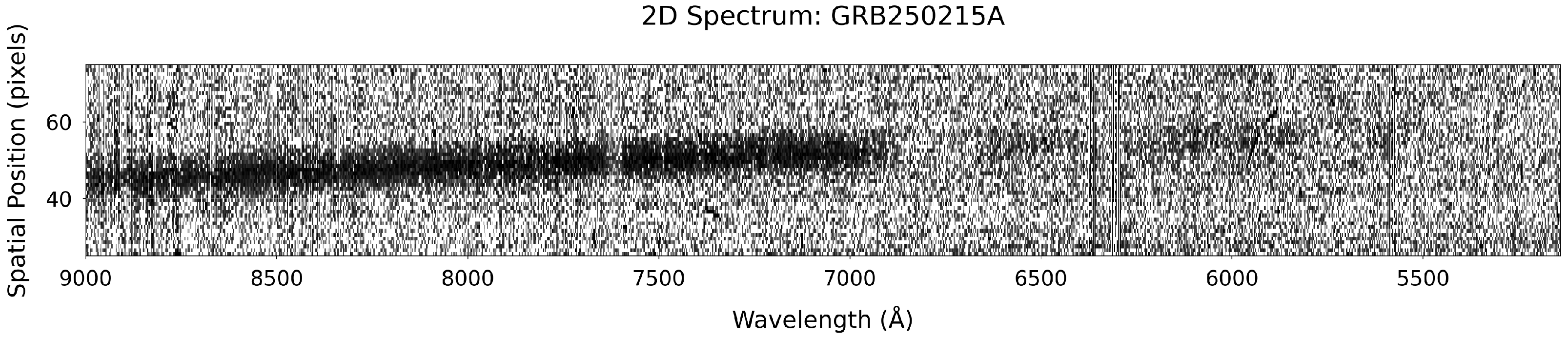

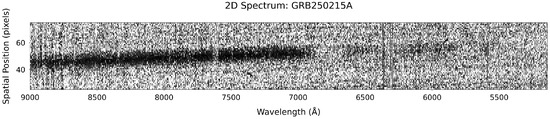

Spectroscopic observations with the 10.4 m GTC telescope (+OSIRIS spectrograph) constitute a pivotal component of our multi-wavelength follow-up campaign. While the BOOTES network provides rapid optical imaging and initial photometric characterization, the high-resolution spectrum obtained here allows for a precise redshift determination and a thorough examination of the host galaxy’s environment. These spectroscopic data enable us to investigate the physical conditions in the host and along the line of sight, offering critical insights into the interstellar and intergalactic media. Such information is essential not only for confirming the nature of the transient event but also for refining theoretical models of its progenitor system. Among the various sources we observed, the transient EP250215a is of particular interest. As an example, we show in Figure 1 the two-dimensional spectrum, which reveals a pronounced spectral break at ∼7100 Å, attributed to Ly absorption.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional spectrum of EP250215a obtained with GTC/OSIRIS. The red continuum remains smooth up to ∼7100 Å, beyond which a pronounced spectral break appears. This feature is attributed to Ly absorption in the host galaxy’s interstellar medium (ISM), while the blueward region is characterized by a Ly forest produced by HI absorption from intervening intergalactic medium (IGM) clouds along the line of sight.

In summary, the integration of fast-response imaging and detailed spectroscopic analysis exemplifies the comprehensive approach needed to unravel the complexities of these transient phenomena.

2.3. BOOTES Responsiveness

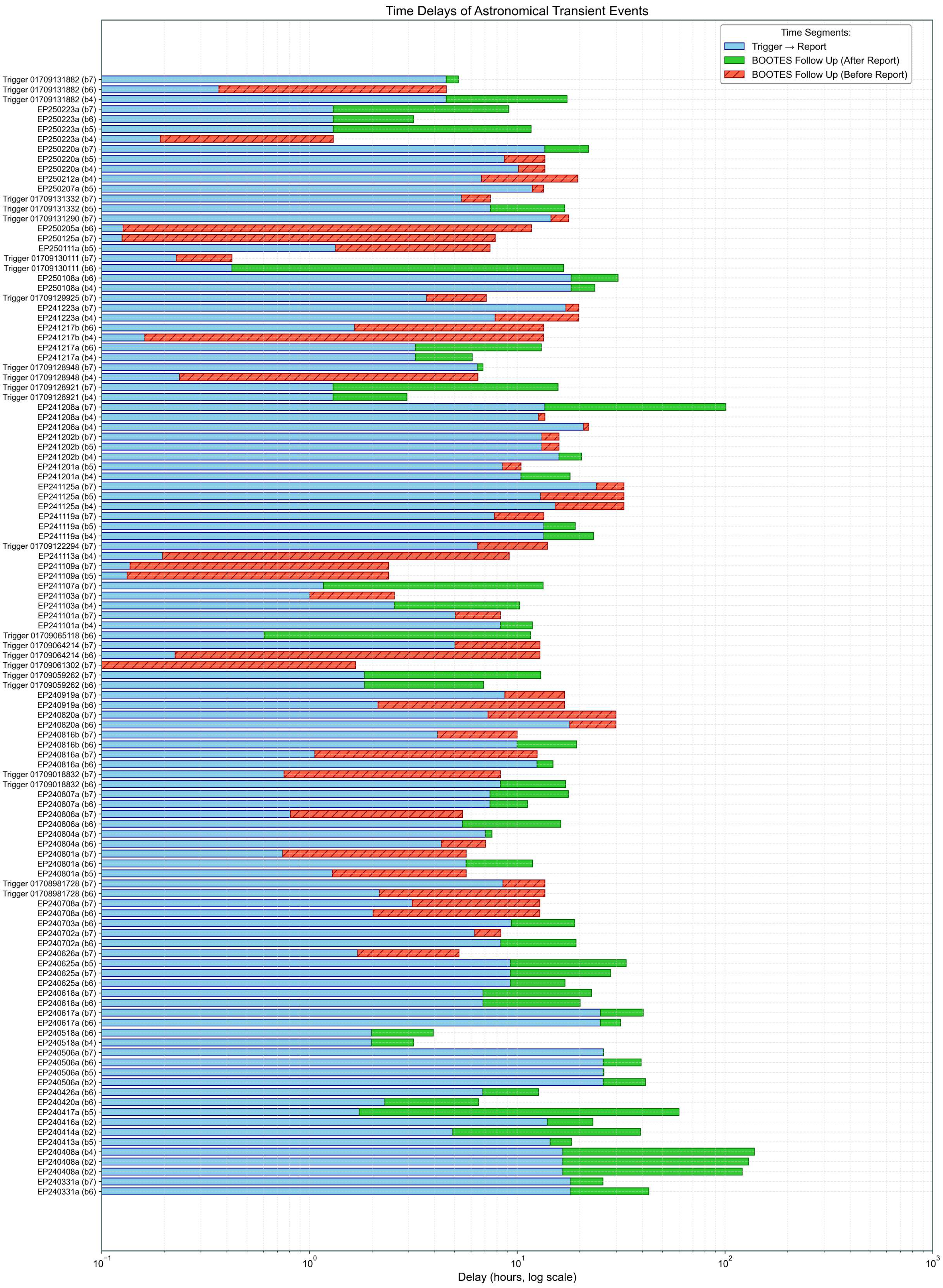

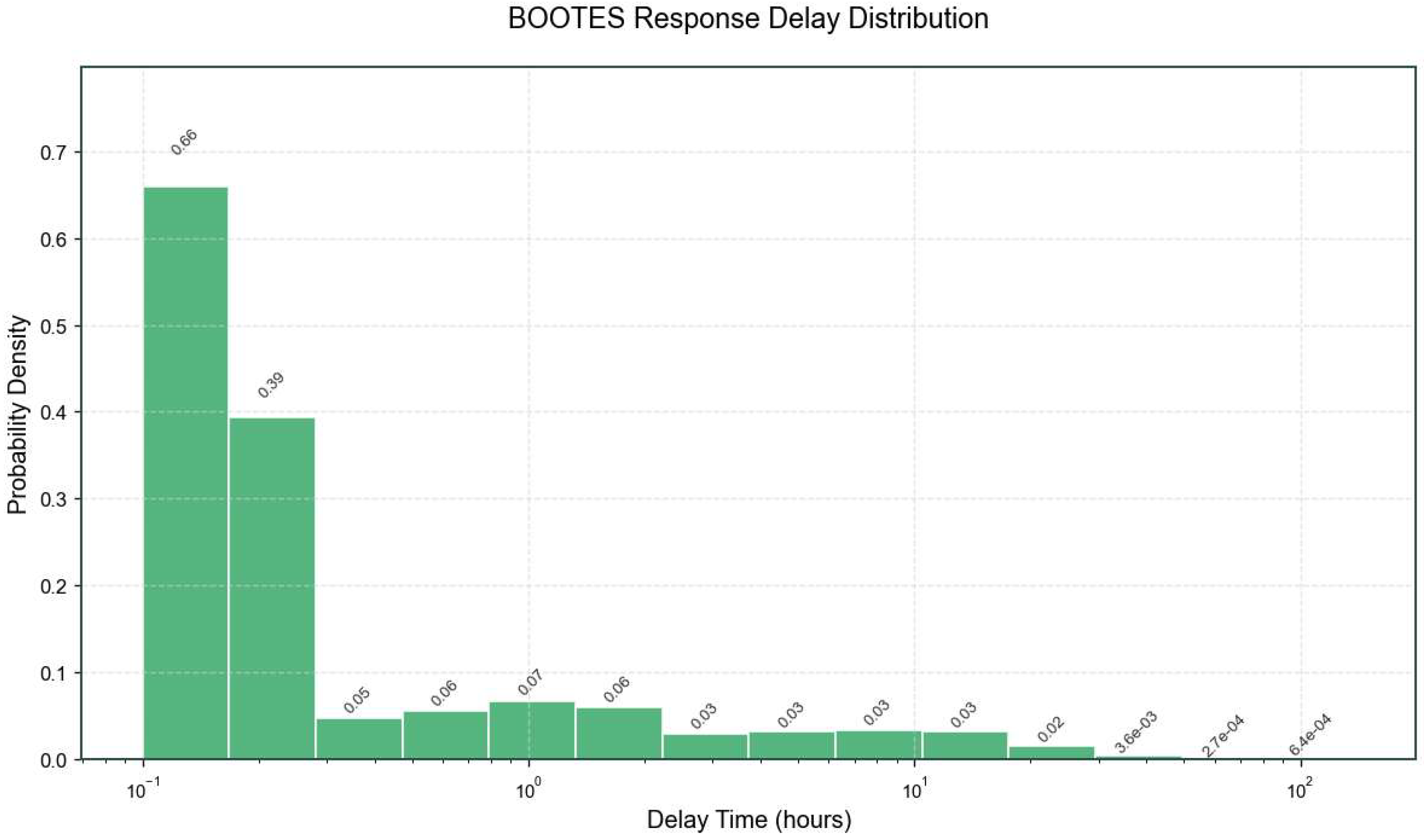

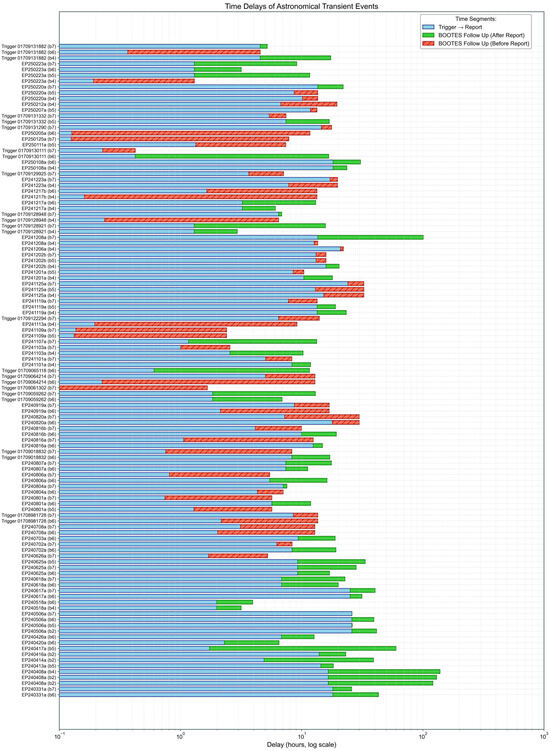

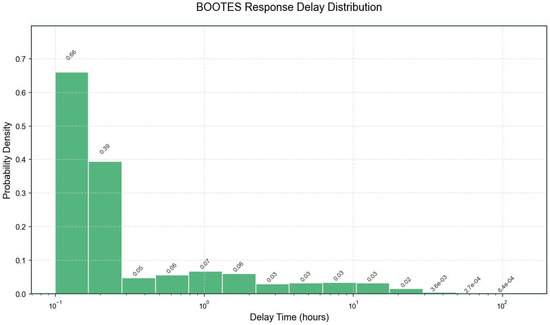

The BOOTES telescope network excels at rapid follow-up of astronomical transients, delivering near-real-time optical observations. Figure 2 breaks down, for each EP trigger, the interval from trigger to formal report (“Trigger → Report”) and the ensuing BOOTES observation. Remarkably, in 53 of 113 cases (46.9%), BOOTES began observing before the formal report—i.e., negative tracking delays. To achieve millisecond-level ingestion and parsing of EP alerts, BOOTES relies on the GCN Kafka service (built on Apache Kafka [15]). Kafka’s high throughput allows the network to autonomously schedule observations even before GCN Circulars are issued, underpinning the “negative latency” measurements in Figure 2 and enabling capture of the earliest optical light curves. Figure 3 illustrates the response time distribution of the BOOTES network; fifteen logarithmically spaced bins were used to generate a normalized histogram of BOOTES response delays (in hours) on a logarithmic axis, highlighting the skewness of the distribution, demonstrating its exceptional capability for rapid follow-up observations of transient events, with the majority of observations commencing within the critical first hours after detection.

Figure 2.

Time delays of BOOTES telescope network follow-up observations for EP transient sources, plotted on a logarithmic time axis (hours). Each horizontal bar is composed of up to three segments: (1) Trigger → Report (blue), showing the elapsed time from the EP trigger to the formal report; (2) BOOTES Follow-Up (After Report) (green), representing observations initiated after the report; (3) BOOTES Follow-Up (Before Report) (red), indicating negative tracking delays when BOOTES began observing prior to the report. Bars are offset from the origin by a small constant (left = ) to ensure visibility on the log scale. This chart highlights BOOTES’s rapid-response capability across a wide dynamic range of follow-up latencies.

Figure 3.

Distribution of BOOTES response delays to astrophysical transients initially detected by the EP telescopes. Despite the challenging slew and setup, BOOTES achieves follow-up within 1 h for 13.3% of triggers and within 3 h for 22.1% of triggers, capturing the crucial early-time emission before most observations begin.

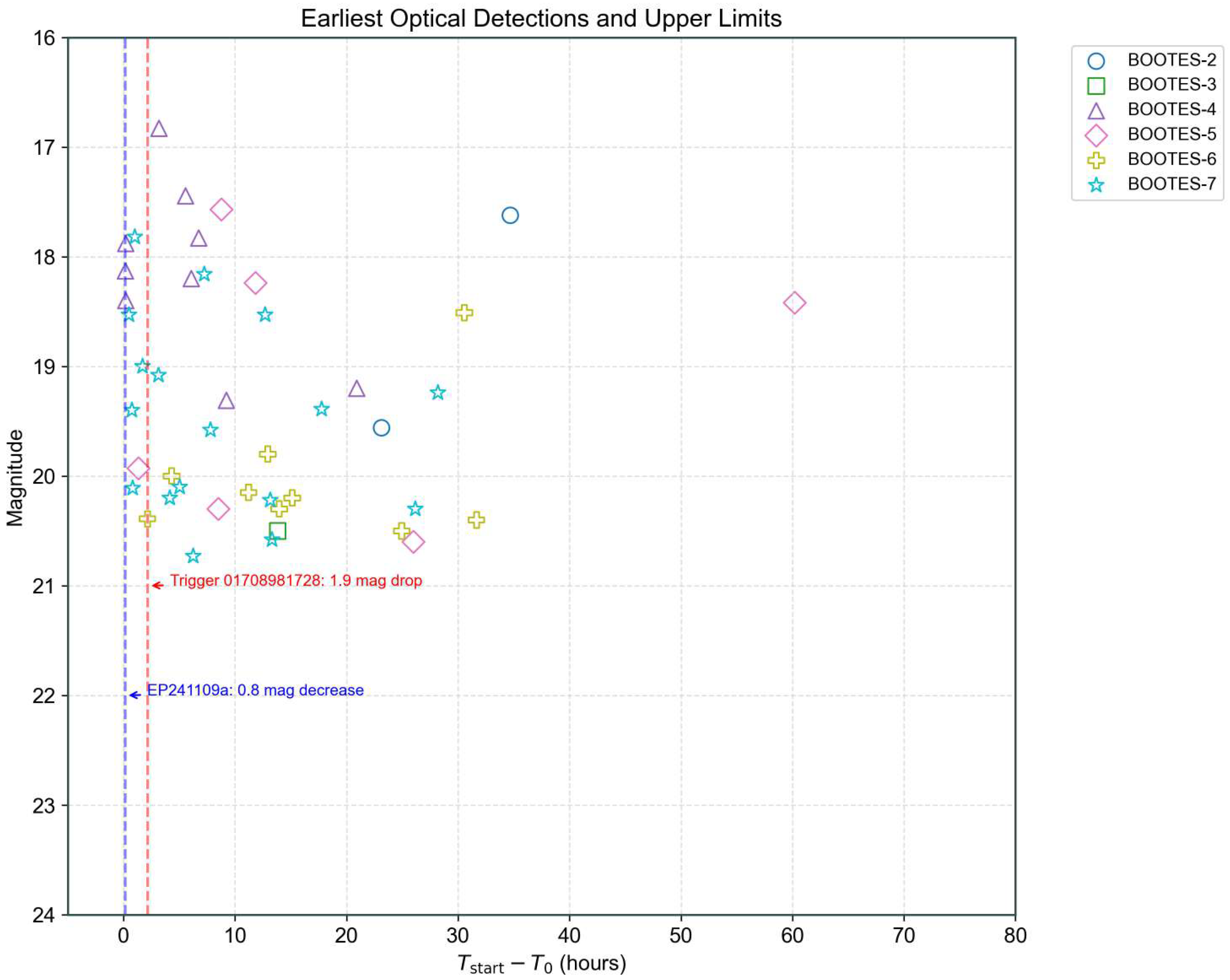

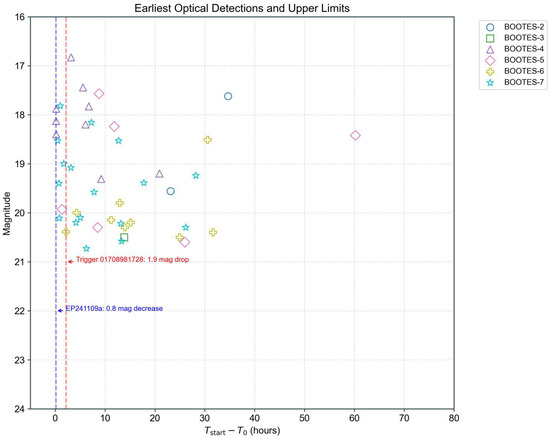

Figure 4 shows the earliest optical detections and upper limits for EP sources observed by the BOOTES telescope network. The heterogeneous distribution of data points reflects the varying sensitivity and response times of the BOOTES telescopes. For example, the repeated observations of EP240426a by BOOTES-4 and BOOTES-6 demonstrate the network’s capability to track transient evolution across multiple instruments.

Figure 4.

The earliest optical detections and upper limits for transients observed by the BOOTES telescope network. Magnitude values (or upper limits) are plotted against the time difference (hours), where is the initial trigger time. Data points are categorized by the BOOTES telescope identifier (BOOTES-2 to BOOTES-7), with empty markers indicating upper limits. Vertical dashed lines highlight special cases: a rapid brightness drop of 1.9 mag (red) and a 0.8 mag decrease (blue). The horizontal axis spans to 80 h, and magnitudes range from 16 to 24.

BOOTES Network Observations of Multiple Sources

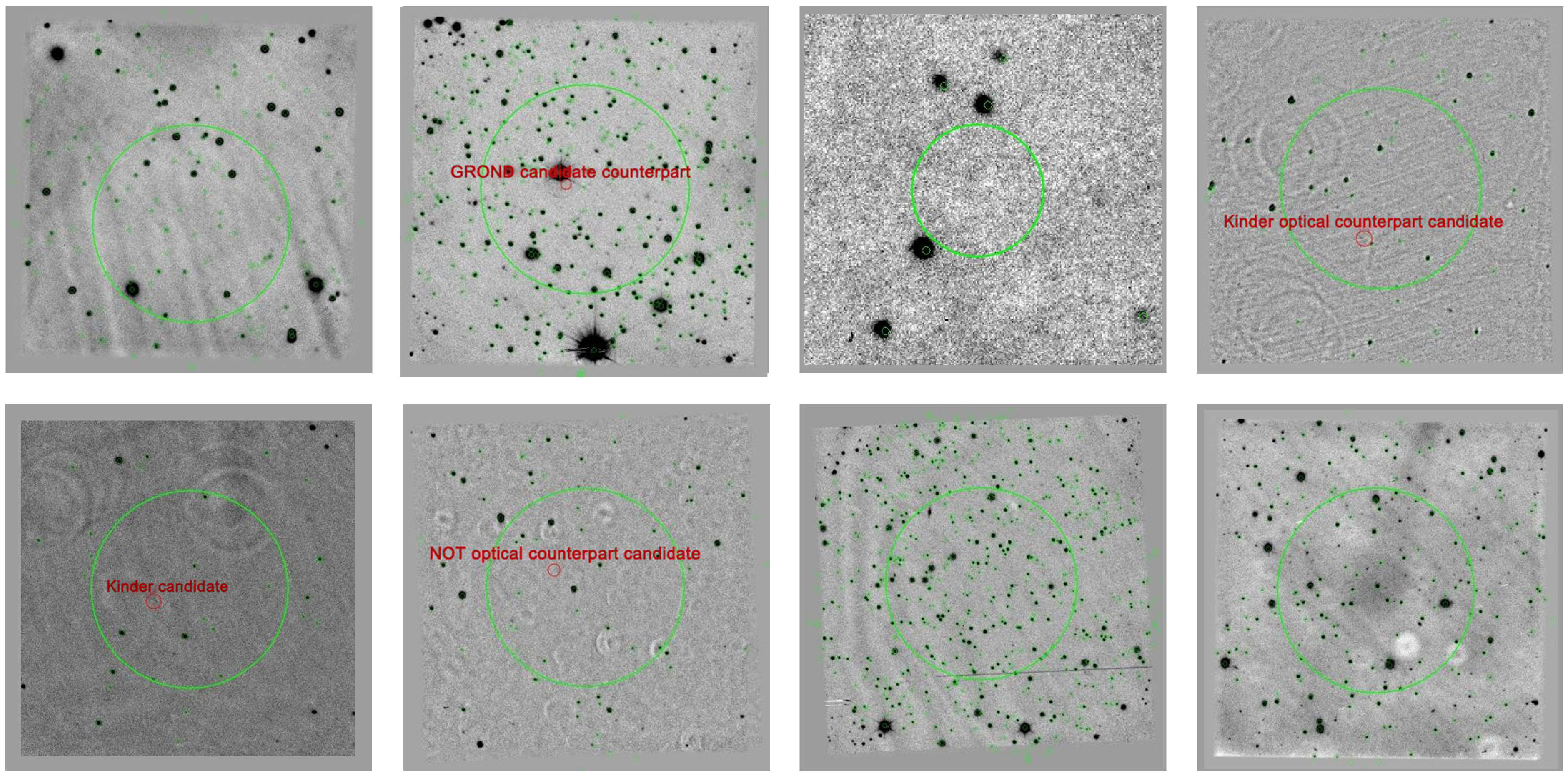

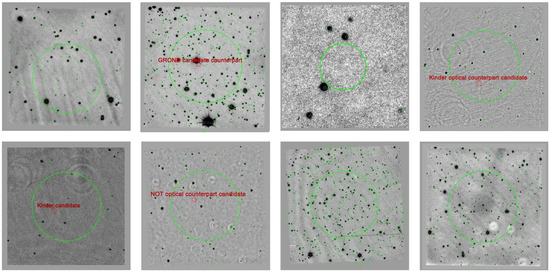

BOOTES network telescopes routinely conduct follow-up observations for EP-detected transients, providing detailed optical monitoring. Figure 5 shows selected sources observed across multiple epochs, demonstrating the BOOTES network’s capability to track the temporal evolution of transients.

Figure 5.

Some of the EP transients that were followed up on by the BOOTES network. The sources are arranged from left to right, top to bottom: EP240315a, EP240404a, EP240413a, EP240414a, EP240416a, EP240420a, EP240426a, and EP240506a. The green circles in the image denote sources detected by the telescope’s automated source extraction algorithm. However, not all of these correspond to confirmed optical counterparts of the EP X-ray transient sources; some may be unrelated background objects or noise.

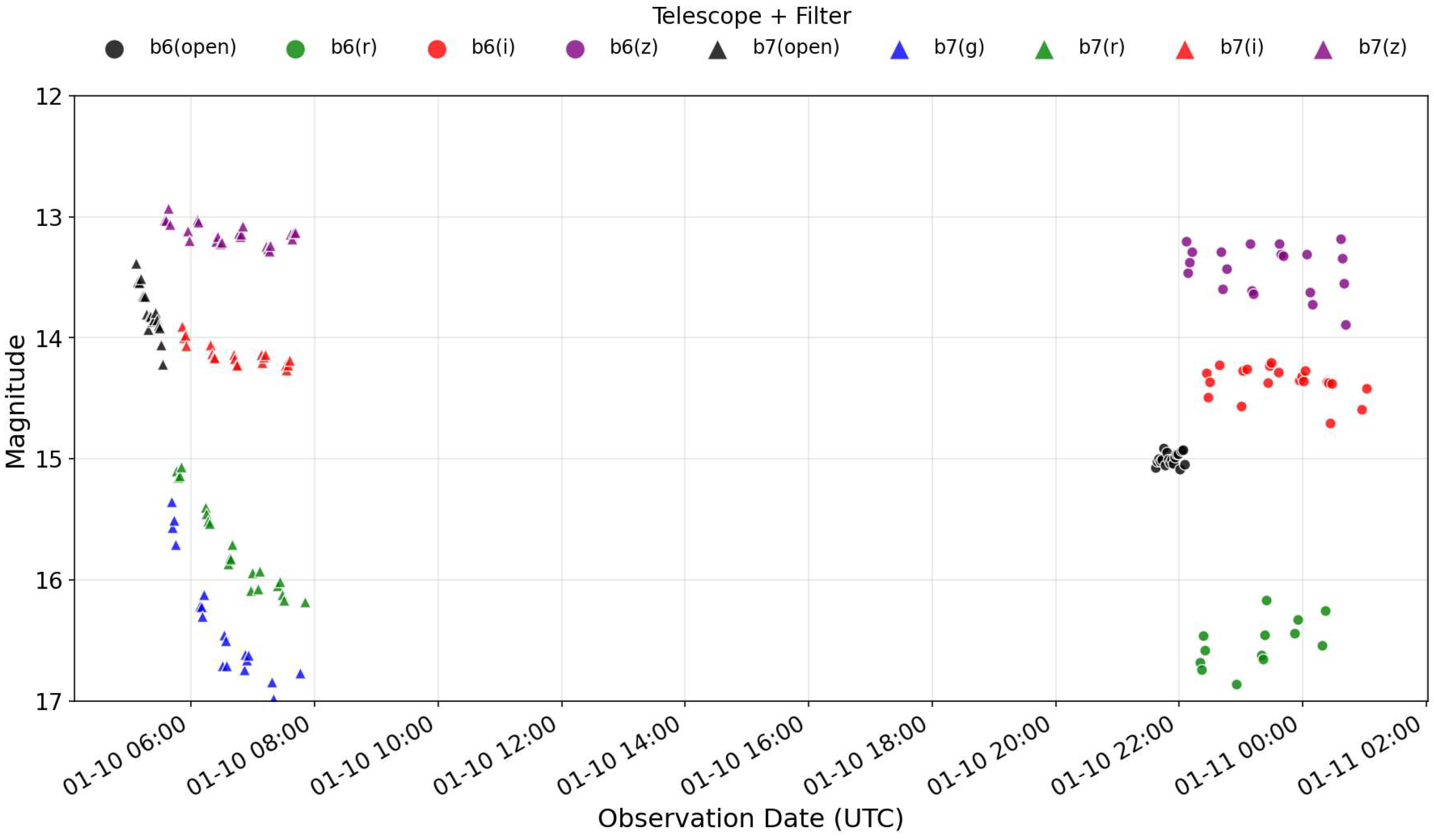

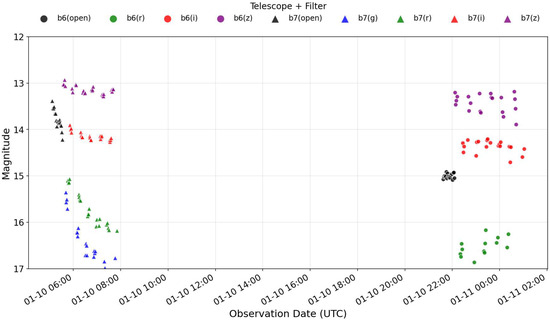

Optical light curves can be also provided automatically. As an example, the optical light curves of EP250110a, a flare star observed on 10 January 2025, using BOOTES-6 and BOOTES-7, are shown in Figure 6. These observations highlight significant brightness and color variations, with the z-band consistently showing brighter magnitudes compared to the r-band, suggesting significant spectral evolution, as seen in most active star flares [16].

Figure 6.

Filter-specific light curves of RX J0429.3-3124 obtained from BOOTES-6 (B6) and BOOTES-7 (B7) observations. Different filters are represented by distinct colors and symbols as indicated in the legend. Open symbols denote observations under suboptimal atmospheric conditions.

By focusing on the optical data and emphasizing response times, this section underscores BOOTES’s role in providing rapid and high-quality follow-up observations that complement EP’s X-ray detections.

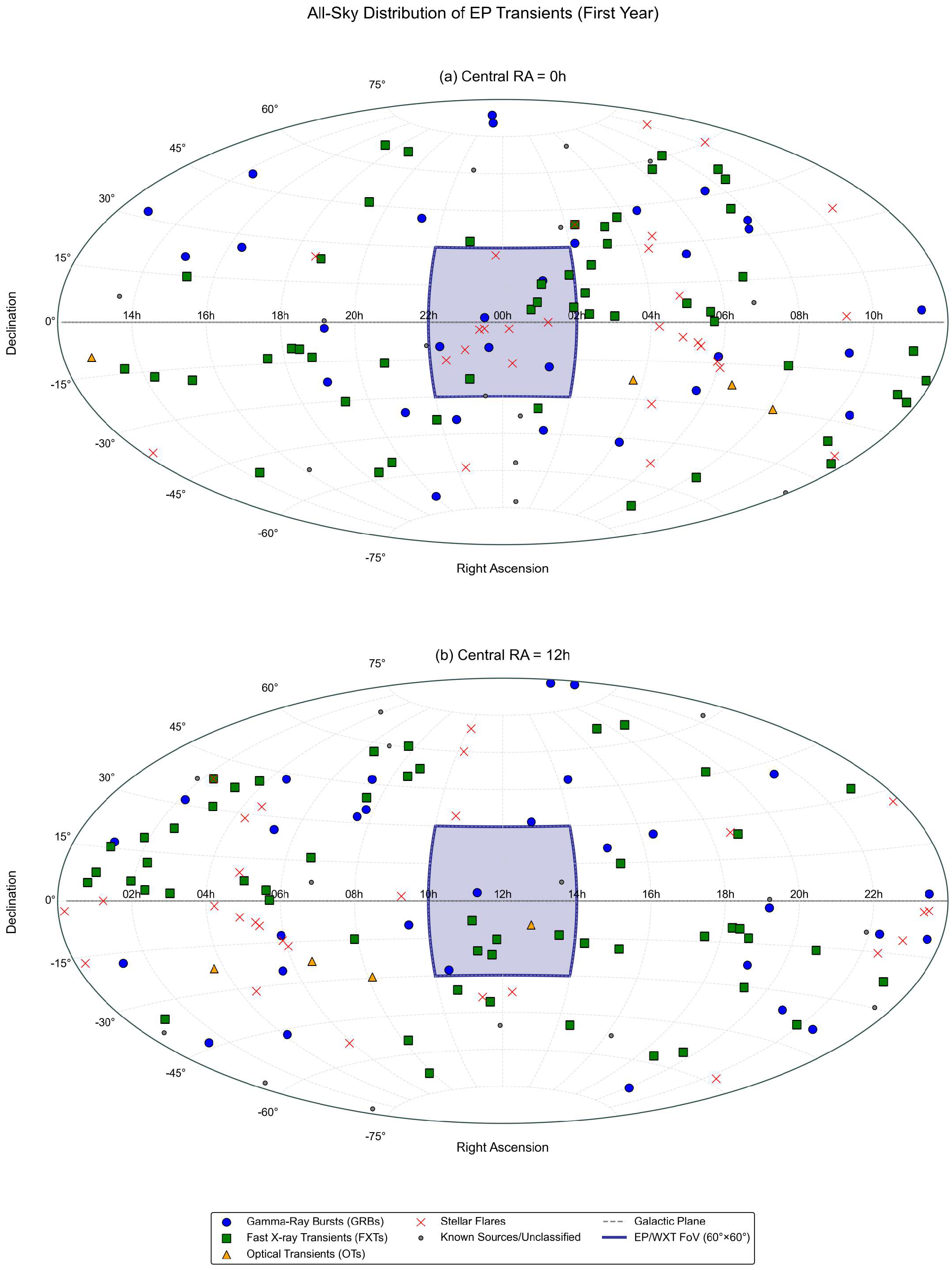

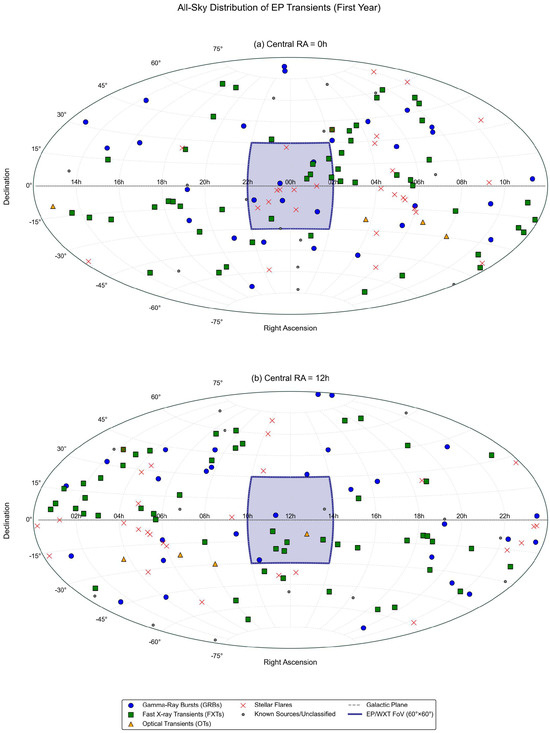

3. Overview of EP X-Ray Transients During the First Year

The spatial distribution of all EP transients detected during the first year of operation (from 19 February 2024 to 26 February 2025) is presented in Figure 7. A total of 128 transients were identified, with Fast X-ray Transients (FXTs) being the most numerous events (amounting to 52), followed by Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs) with 30 events, Stellar Flares with 28 events (bearing in mind that a very significant number remain unreported), Known Sources/Unclassified (14 events), and Optical Transients (4 events). The distribution exhibits a relatively isotropic pattern across the sky, with sources detected at all declinations. However, a slight deficit is observed near the Galactic plane, likely due to absorption effects and source confusion in these densely populated regions. This highlights the challenges of detecting transients in crowded fields, despite EP/WXT’s wide field of view and sensitivity.

Figure 7.

All-sky distribution of EP transients detected during the first year of operations, displayed in dual Aitoff projections with different coordinate centering. (a) Galactic distribution centered at RA = 0 h (vernal equinox) and (b) RA = 12 h (autumnal Equinox), both in J2000 equatorial coordinates. Source classes are differentiated by distinct markers: Gamma-Ray Bursts (blue circles), Fast X-ray Transients (green squares), Optical Transients (orange triangles), Stellar Flares (red crosses), and Known Sources/Unclassified (gray dots). The dashed black line traces the Galactic plane, while the blue shaded region demarcates the EP/WXT’s instantaneous 60° × 60° field of view. This dual projection demonstrates complete celestial coverage and reveals longitudinal variations in transient distributions.

3.1. Source Classification

To systematically categorize the X-ray transients detected by EP, we classify each source into a primary category based on its dominant characteristics while noting any secondary classifications where applicable. The classification criteria are as follows:

- Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs):

- −

- Identified based on high-energy X-ray/gamma-ray emissions.

- −

- Typically exhibit short (<2 s) or long (≳2 s) durations with rapid flux variability [17].

- −

- If associated with a known GRB event (e.g., detected by Fermi-GBM or Swift), they are classified as GRBs.

- −

- Sources with possible GRB-like properties but lacking definitive confirmation are marked as “Likely GRB”.

- Fast X-ray Transients (FXTs):

- −

- Short-lived (typical time scale range of seconds to kiloseconds) X-ray flares without clear GRB signatures [18].

- −

- Exhibit sudden onset and rapid decay in flux.

- −

- May lack a known gamma-ray counterpart but show variability consistent with X-ray transients.

- −

- If an FXT also has multi-wavelength detections, it is marked with additional secondary classifications.

- Optical Transients (OTs):

- −

- Transients with detected optical counterparts, either from follow-up observations or archival surveys.

- −

- Includes events such as Fast Blue Optical Transients (FBOTs) and optical afterglow candidates of GRBs.

- −

- If an optical transient is associated with a confirmed astrophysical event (e.g., a supernova), this is noted in the classification.

- Stellar Flares (M-dwarf Flares):

- −

- X-ray events associated with active low-mass stars (e.g., M-dwarfs).

- −

- Identified based on position coincidence with known stellar objects (e.g., Gaia DR3 sources).

- −

- Typically exhibit high-energy flaring activity over timescales of seconds to minutes.

- Known Sources/Unclassified:

- −

- Transients that do not fit neatly into any of the above categories.

- −

- May include weak X-ray sources, events with insufficient data for robust classification, or candidates for future multi-wavelength follow-up.

- −

- X-ray activity from cataloged astrophysical objects such as cataclysmic variables (CVs), high-mass X-ray binaries (HMXBs) or active galactic nuclei (AGNs).

Each transient is assigned to a single primary category based on the dominant observed characteristics, with secondary classifications given in the “Notes” column, where applicable. This approach ensures that sources are not double-counted in statistical analyses while preserving additional classification context.

Rationale for Using First Observation Data: The data presented in the “X-ray properties” column of Table 3 are based solely on the initial observations made by the EP/FXT. This decision is motivated by the need for a uniform and consistent basis for classifying and comparing X-ray transients. The initial observation allows for determining the fundamental physical parameters (e.g., duration, peak flux, photon index) at the time of detection, which are crucial for establishing the primary characteristics of each event. Although follow-up observations provide valuable insights into the temporal evolution and multi-wavelength behavior of the transients, incorporating these later data in the same column could lead to confusion by mixing the initial detection with subsequent changes. Instead, any supplementary information from follow-up observations is discussed in the following section (or in the accompanying notes).

Table 3.

Classification of EP sources based on their nature and multi-wavelength observations.

Table A1 in the Appendix A provides a detailed summary of the multi-wavelength follow-up observations for transient events whose names begin with “EP”. These sources are selected because they represent the initial detections by Einstein Probe that subsequently triggered coordinated observations across various wavelengths.

3.2. Notable Sources

During its first year of operation, EP detected numerous interesting X-ray transients. Here, we highlight five of them.

The first transient detected by EP was EPW20240219aa, reported during its commissioning phase [19]. Follow-up analysis suggested that this source was likely a gamma-ray burst (GRB) event, based on the detection of a coincident weak gamma-ray transient in Fermi/GBM data [20]. This source was subsequently identified as an untriggered gamma-ray burst through archival searches in Fermi/GBM, Swift/BAT, and Insight-HXMT/HE data. The joint spectral analysis revealed that a single cutoff power-law model could well describe both X-ray and gamma-ray bands, with a photon index of and a peak energy of keV, classifying it as an X-ray rich GRB. The analysis of prompt emission suggested a Poynting flux-dominated outflow rather than a thermal photon-dominated one. While follow-up observations in optical and radio bands identified several candidates, none was confirmed as the afterglow counterpart [21]. This discovery not only marked EP’s first light but also demonstrated its capability in detecting and characterizing the soft X-ray emission of GRBs.

A particularly remarkable discovery was EP240315a, detected on 15 March 2024, which represents one of the most distant high-energy transients observed by EP, at a redshift of [22]. This event exhibited strikingly different temporal profiles between its soft X-ray and gamma-ray emissions—while the gamma-ray emission observed by Swift/BAT and Konus-Wind lasted approximately 40 s, the soft X-ray emission detected by EP-WXT persisted for over 1000 s, making it one of the longest GRB durations ever measured [23]. High-redshift GRBs provide crucial insights into the early universe, serving as beacons to probe the formation of the first-generation stars and the reionization epoch. EP240315a joins this class, which includes GRB 090423 () [5,24], further extending the sample of high-redshift bursts accessible to soft X-ray observations. Multi-wavelength follow-up observations revealed a relativistic jet with a half-opening angle of approximately and a beaming-corrected total energy of ∼ erg, typical of long GRBs [25]. The optical counterpart was detected by ATLAS approximately 1.3 h after the initial X-ray trigger, showing rapid fading behavior with a decay of ∼2 magnitudes within 19 h, while the radio counterpart was detected 2.86 days post-burst using the MeerKAT radio telescope, revealing emission consistent with optically thick synchrotron radiation. The combination of multi-wavelength observations suggested EP240315a originated from a highly relativistic event, likely either a long gamma-ray burst or a jetted tidal disruption event, and demonstrated that some FXTs could be related to the lower-luminosity end of the GRB population [26]. This discovery highlights EP’s capability to probe the high-redshift transient universe, complementing existing missions and potentially uncovering the population of early-universe X-ray transients.

Another intriguing discovery was EP240408a, detected on 8 April 2024, which represents a new class of X-ray transients with an intermediate timescale [27]. The source exhibited a peculiar light curve featuring a 12 s intense X-ray flare that reached a peak flux of erg cm−2 s−1 in the 0.5–4 keV energy band, approximately 300 times brighter than its underlying emission [27]. Further analysis revealed that at redshift z > 0.5, this corresponds to a peak luminosity of ∼ erg s−1 [11]. The X-ray emission showed a plateau phase lasting for 4 days with luminosity exceeding erg s−1, followed by a steep decay () [11]. Extensive multi-wavelength follow-up observations revealed no optical or radio counterparts, though a faint potential host galaxy (r ∼ 24 AB mag) was identified near the X-ray localization [11]. The source’s X-ray spectrum remained non-thermal throughout the outburst, with a power-law photon index varying between 1.8–2.5 [27]. The observed properties of EP240408a were found to be inconsistent with known transient types—notably, the lack of a bright gamma-ray counterpart conflicts with typical gamma-ray bursts of similar X-ray luminosities, suggesting it may represent either a peculiar jetted tidal disruption event at z > 1.0 or an entirely new class of X-ray transients [11].

EP240414a, discovered on 14 April 2024, represents a highly unique fast X-ray transient. Located at a redshift of , it showed an unusually large offset (approximately 26–27 kpc) from its spiral host galaxy [28]. The source exhibited a complex, multi-component light curve featuring an initial rapid decline, followed by an unusual re-brightening reaching an absolute magnitude after two rest-frame days [29]. In the radio band, the source peaked around 30 days post-explosion with luminosity comparable to long gamma-ray bursts (∼ erg s−1 Hz−1), indicating a moderately relativistic outflow (bulk Lorentz factor ) [30]. The source eventually revealed a broad-lined Type Ic supernova component, and while it shared some characteristics with luminous fast blue optical transients (LFBOTs), its distinctive red colors and high X-ray luminosity (∼ erg s−1) suggested different physical mechanisms [31]. This remarkable source represents a previously unknown population of extragalactic fast X-ray transients, bridging the gap between classical gamma-ray bursts and ordinary stripped-envelope supernovae.

EP240709a, discovered by EP on 9 July 2024, represents a distinctive blazar candidate exhibiting remarkable characteristics. Its most notable feature is an extraordinary orphan X-ray flare, where the flux in the 0.5–10 keV energy band increased by at least 28 times compared to its low state in 2020, while showing no significant variability in radio, infrared, optical, UV, and GeV bands [32]. Subsequent NICER monitoring revealed X-ray flux variations between erg s−1 cm−2 in the 0.4–3.0 keV band, and multiple lines of evidence support its classification as a high-frequency-peaked BL Lac object, including its spatial coincidence with the Fermi unassociated source 4FGL J0031.5-5648 and a 99.98% probability of being a quasar as revealed by Gaia DR3 machine learning classification [33]. This discovery demonstrates Einstein Probe’s capability in identifying peculiar activities from active galactic nuclei through high-cadence X-ray sky surveys.

4. Conclusions

The first year of Einstein Probe (EP) operations has not only validated its unique capabilities in monitoring the dynamic X-ray sky but also yielded critical insights into high-energy transient phenomena, thanks to the capability of rapidly disseminating high-energy alerts associated with early follow-up observations, such as the ones carried out with our BOOTES network.

Out of the 128 events, the BOOTES network has been able to follow up on 58 events, detecting 6 optical counterparts at early times (EP240309a, EP trigger ID 01708981728, EP240804a, EP241109a, GRB 241105A, and EP trigger ID 01709128948).

While EP delivered outstanding results in its inaugural year, continued improvements in data processing, calibration, and real-time alert dissemination will further enhance its scientific yield. Moreover, coordinated multi-wavelength and multi-messenger follow-up observations remain essential for fully characterizing the diverse transient phenomena uncovered by EP. In this regard, we expect the early-time follow-up by the BOOTES Global Network (and other facilities) will enhance the overall picture of the transients discovered by EP.

As time-domain and multi-messenger astronomy continue to evolve, EP’s first-year contributions firmly establish it as a key observatory for unveiling the transient X-ray universe, effectively bridging the gap between current and next-generation high-energy missions.

Author Contributions

S.W., A.J.C.-T., and Y.H.: methodology, formal analysis, and investigation; I.P.-G., M.G., M.D.C.-G., S.G., E.J.F.-G., and R.S.-R.: resources, data curation; Y.H., M.G., A.J.C.-T., C.P.-d.-P., G.G.S., D.X., and B.-B.Z.: supervision; A.J.C.-T. and M.G.: funding acquisition; S.W.: writing—original draft preparation; all authors: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC). We acknowledge the use of data from the BOOTES (Burst Observer and Optical Transient Exploring System) network. We thank the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (IAA-CSIC) for its support and collaboration in this research. A.J.C.-T. acknowledges funding from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through project PID2023-151905OB-I00, and the Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa grant CEX2021-001131-S, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. M.G. acknowledges support from the Academy of Finland project No. 325806. The research at Ural Federal University (UrFU) was supported by the Priority-2030 development program (04.89).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author(s) upon reasonable request. Additionally, part of the data used in this work were obtained from publicly available sources, including Gamma-ray Coordinates Network (GCN) Circulars (https://gcn.nasa.gov/circulars, accessed on 26 February 2025), The Astronomer’s Telegram (ATel) (https://www.astronomerstelegram.org, accessed on 26 February 2025), and previously published research. Readers are encouraged to refer to these sources for further details.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (IAA-CSIC) for its institutional support and collaboration in this research. We also acknowledge the contributions of the BOOTES team for their assistance in data collection and technical support. We are grateful to the GCN and ATel communities for providing timely alerts and observational data, which greatly benefited this study. Additionally, we appreciate the observational efforts of various ground-based facilities. The authors also extend their gratitude to colleagues who provided valuable discussions and feedback during the development of this work. We further thank the EP team for fruitful conversations that provided valuable insights and enriched this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EP | Einstein Probe |

| WXT | Wide-field X-ray Telescope |

| FXT | Follow-up X-ray Telescope |

| FXTs | Fast X-ray Transients |

| SVOM | Space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor |

| BOOTES | Burst Observer and Optical Transient Exploring System |

| GCN | Gamma-ray Coordinates Network |

| TDE | Tidal Disruption Event |

| GRB | Gamma-Ray Burst |

| ATel | The Astronomer’s Telegram |

| NICER | Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer |

| eROSITA | extended Roentgen Survey with an Imaging Telescope Array |

| Chandra | Chandra X-Ray Observatory |

| XRT | X-ray Telescope |

| BAT | Burst Alert Telescope |

| GBM | Gamma-ray Burst Monitor |

| ROSAT | Roentgen Satellite |

| AGN | Active Galactic Nucleus |

| CV | Cataclysmic Variable |

| HMXB | High-Mass X-ray Binary |

| APEC | Astrophysical Plasma Emission Code |

| SDSS | Sloan Digital Sky Survey |

| WFCAM | Wide Field Camera |

| VISTA | Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy |

| VLT | Very Large Telescope |

| GTC | Gran Telescopio Canarias |

| OSIRIS | Optical System for Imaging and low-Intermediate-Resolution Integrated Spectroscopy |

| UCAC4 | U.S. Naval Observatory CCD Astrograph Catalog, 4th edition |

| Gaia DR3 | Gaia Data Release 3 |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Multi-wavelength follow-up observations of Einstein Probe transients.

Table A1.

Multi-wavelength follow-up observations of Einstein Probe transients.

| Name | Optical/NIR | X-Ray/Gamma-Ray | Radio/mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPW20240219aa | REM, LDT, NIRES, WINTER, Xinglong Observatory, GECKO/LOAO, 7DT, Mondy, Liverpool | SPI-ACS/INTEGRAL, Insight-HXMT/HE, Swift BAT, Fermi GBM | VLA |

| EP240305a | SALT, GRANDMA | Swift | ATCA |

| EP240309a | SALT | – | MeerKAT |

| EP240315a | WIRC, Ondřejov Observatory (D50), GTC, PRIME, 3.6 m TNG NIR, TShAO (Zeiss-1000), Kitab, Montarrenti, Lulin observatory, GROND J-band, VLT/X-shooter, Nanshan/HMT, Liverpool Telescope, ATLAS, Kinder | Chandra, Konus-Wind, Swift/BAT | e-MERLIN, ATCA, MeerKAT |

| EP240331a | BOOTES-6, 7, MASTER, GRANDMA, Kinder | – | |

| LXT 240402A | VLT X-shooter, WFST, AST3-3, MASTER, GWAC-F50A, Kinder | LEIA, Chandra, Swift, Konus-Wind, GECAM-C, Glowbug, Fermi GBM | MeerKAT, ATCA, e-Merlin |

| EP240408a | BOOTES-2, 4, GSP, MASTER, GROND, | GECAM-B, Swift-XRT | – |

| EP240413a | BOOTES-5, GOTO | GECAM-B | – |

| EP240414a | BOOTES-2, GTC, LBT, Gemini-South, NIRES, WINTER, Terskol Zeiss-2000, GMG, GSP, Pan-STARRS, Kinder | Chandra | MeerKAT |

| EP240416a | WINTER, Terskol Zeiss-2000, Khureltogoot, BOOTES-2/TELMA, MASTER, Kinder | – | – |

| EP240417a | BOOTES-5, YAHPT, SOAR | – | – |

| EP240420a | BOOTES-6, TNT, Xinglong, Nanshan, GWAC-F50A, NOT | – | – |

| EP240426a | BOOTES-6, GMG-2.4 m, DECam | EP-FXT | ASKAP, VAST |

| EP240426b | AST3-2 | – | – |

| EP240506a | BOOTES-2, 5, 6, 7, Xinglong, CrAO ZTSH, TRT, BOOTES Network, Kinder | – | RACS, VLASS |

| EP240518a | BOOTES-4, 6, GSP | – | – |

| EP240617a | BOOTES-6, 7, STEP/T80S | Swift/XRT, Fermi/GBM | – |

| EP240618a | BOOTES-6, 7, NOT, GSP, Abastumani, GRANDMA, TRT, OHP/T193 MISTRAL | Fermi/GBM, Swift/XRT | – |

| EP240625a | BOOTES-5, 6, 7, GRANDMA, NOT | – | – |

| EP240626a | BOOTES-7, Montarrenti Observatory, KAIT | – | – |

| EP240702a | BOOTES-6,7, 7DT, TRT, GSP | Swift/XRT | – |

| EP240703a | BOOTES-6, TRT, KAIT, BTA, Liverpool Telescope, Kinder, JinShan | Konus-Wind, Swift/XRT | – |

| EP240703b | GSP, TRT | Swift/XRT | – |

| EP240703c | Kinder | Swift/XRT | – |

| EP240708a | BOOTES-6,7, Kinder, GSP, KAIT, NOT, SVOM/C-GFT | Swift/XRT | – |

| EP240801a | BOOTES-5, 6, 7, GTC, Keck/LRIS, Assy-Turgen, BTA BVRI, ZTSh (CrAO), Osservatorio Astronomico Nastro Verde, SAO RAS, CrAO, AbAO, GRANDMA, Kilonova-Catcher, Leavitt Observatory, JinShan, NOT, LCOGT, GSP, Kinder, KAIT, GMG, TRT | – | GMRT |

| EP240802a | Kinder, SWIFT-UVOT, KAIT, Montarrenti Observatory, Bassano Bresciano Observatory | SWIFT-XRT, Konus-Wind, SVOM/GRM | – |

| EP240804a | LCOGT, BOOTES-6, NOT, GSP, VLT/X-shooter, LCOGT | Konus-Wind | – |

| EP240806a | BOOTES-6, 7, Global MASTER, Liverpool Telescope, Gemini North-GMOS, KAIT, LCOGT, GSP | – | – |

| EP240807a | BOOTES-6, 7, PRIME, STEP/T80S, Global MASTER | Konus-Wind | – |

| EP240816a | BOOTES-6, 7, Liverpool Telescope, KAIT, Global MASTER, TRT | – | – |

| EP240816b | BOOTES-6, 7, TRT, MASTER, KAIT, Liverpool | – | – |

| EP240820a | BOOTES-6, 7, PRIME, TRT | – | – |

| EP240904a | NOT | NuSTAR | ATCA |

| EP240908a | Gemini-North telescope, Mondy, AbAO, optical afterglow candidate, Global MASTER, TRT | WXT, FXT | – |

| EP240913a | AbAO, Mephisto, MASTER, VLT/HAWK-I, KAIT, NOT, JinShan, ESO-NTT | – | – |

| EP240918a | SVOM/VT, 1.6 m Mephisto, Global MASTER, JinShan, YAHPT, Kinder, GMG | Swift/XRT | – |

| EP240918b | Kinder | – | – |

| EP240918c | Kinder | – | – |

| EP240919a | BOOTES-6, 7, SVOM/VT, Mondy, REM, KAIT, Kinder, Global MASTER, NOT, Gemini, GOTO, JinShan | Fermi GBM, SVOM/GRM, INTEGRAL SPI-ACS | – |

| EP240930a | KAIT, CrAO ZTSH, SVOM/C-GFT, Liverpool Telescope, GOTO, Global MASTER | IPN triangulation, Swift/BAT | – |

| EP241021a | GTC, OSN, CAHA, Keck/LRIS, OHP/T193, SOAR, Kinder, Liverpool Telescope, Mephisto, SAO RAS, Gemini-South, Xinglong Observatory, Fraunhofer Telescope, VLT/FORS2, KAIT, DFOT, GSP, TRT, NOT, MASTER, GOTO | Konus-Wind, Swift-UVOT, Fermi-GBM | SMA, VLA, AMI-LA, ATCA, e-MERLIN |

| EP241025a | TNT, TRT | – | – |

| EP241026b | Keck/LRIS, Kinder, Liverpool Telescope, LBT, GROWTH, MASTER | – | – |

| EP241030a | Kinder, TNOT, SAO RAS, GMG, FTW, MASTER | – | – |

| EP241101a | BOOTES-4, 7, CrAO ZTSH, NUTTelA-TAO/BSTI, FTW, Kinder, OHP/T193, MASTER, | – | – |

| EP241103a | BOOTES-4, 7, GTC, GIT, GOTO, Gemini, GSP, LCO, MASTER | Swift XRT | – |

| EP241104a | Kinder | – | – |

| EP241107a | BOOTES-7, OSN, CAHA, GTC, SOAR, AbAO, MASTER, KAIT, Kinder, AKO, GSP, Gemini-South, OHP/T193, FTW, GIT, MASTER, SVOM/C-GFT, AKO | – | VLA |

| EP241109a | KAIT, Lick, BOOTES-5, 7 | – | – |

| EP241113a | BOOTES-4, OSN, Keck/LRIS, MASTER, WINTER | Swift XRT, Fermi-GBM | eMERLIN |

| EP241113b | OSN, Global MASTER | – | – |

| EP241115a | CAHA, Kinder, MASTER | Swift XRT, SVOM/GRM | – |

| EP241119a | BOOTES-4, 5, 7, 7DT, Kinder, GIT, WINTER, MASTER | – | – |

| EP241125a | BOOTES-b1b, 4, 5, 7, Kinder | – | – |

| EP241126a | BOOTES-7, SOAR, Mephisto, NOT, SVOM/VT, WFST, Kinder, GSP, TRT | – | – |

| EP241201a | BOOTES-4, 5, GTC, Mephisto, Kinder, NOT, MASTER | – | – |

| EP241202b | BOOTES-4, 5, 7, MASTER, KAIT | Fermi-GBM | – |

| EP241206a | MASTER, BOOTES, OSN | – | – |

| EP241208a | BOOTES-4, 7, OSN, MASTER, NOT, Kinder | SVOM/ECLAIRs | – |

| EP241213a | – | GRBAlpha, Konus-Wind, INTEGRAL/SPI-ACS | – |

| EP241217a | BOOTES-4, 6, OSN, GTC, SYSU, Liverpool, Leavitt, Mephisto, REM, NOT, GROWTH, Xinglong, MASTER, Gemini-North, Kinder, LCO | Fermi-GBM, Swift-XRT | – |

| EP241217b | Mephisto, GRANDMA/T1MPicduMidi, Nanshan/HMT, NOT, REM, SOAR, MASTER | Fermi-GBM | VLA, ATCA |

| EP241223a | BOOTES-4, 7, Mondy AZT-33IK, MASTER | – | – |

| EP241231b | Liverpool | – | – |

| EP250101a | Xinglong, Liverpool | – | – |

| EP250108a | BOOTES-4, 6, CAHA, AbAO, CMO, Terskol, DFOT, Gemini GMOS-S, NOT, GMG, SAO RAS, Mephisto, LCO, Liverpool Telescope, MASTER, VLT/X-shooter | Swift/XRT, Fermi-GBM | ATCA, VLA, MeerKAT |

| EP250109a | Mephisto, SVOM/VT, Terskol (INASAN), SAO RAS, GMG, MASTER, GOTO | GRBAlpha, Swift/BAT-GUANO, Swift/XRT, Swift/UVOT, Fermi-GBM | – |

| EP250109b | Liverpool | – | – |

| EP250111a | BOOTES-5, GTC, SAO RAS, KAIT, Mondy, NOT, MASTER | Einstein Probe WXT, Swift/XRT | – |

| EP250125a | BOOTES-7, DFOT, Kinder, Gemini, REM | Fermi, Swift | – |

| EP250205a | FTW | – | VLA |

| EP250207a | BOOTES-6, 7, NOT | Fermi-GRB, XRT | – |

| EP250207b | BOOTES-5, GTC, Xinglong, NOT, Liverpool, MASTER, Gemini | Chandra | VLA |

| EP250212a | FTW, Xinglong, MASTER, Liverpool, NOT | – | – |

| EP250215a | GTC, LCO, COLIBRI, NOT, Mephisto, Gemini, SVOM, MASTER | AstroSat CZTI, INTEGRAL SPI-ACS | – |

| EP250220a | FTW, Liverpool Telescope, Mephisto, Kinder, Xinglong, MASTER | – | – |

| EP250223a | BOOTES-4, CraO ZTSH, GMG, GROWTH-India, Kinder, GOTO, COLIBRI/DDRAGO, REM, TRT, Mephisto, SVOM/VT, OASDG, LCO, NOT, MASTER | Swift/XRT | – |

| EP250226a | Xinglong, SVOM/VT, Mephisto, Kinder, GSP, COLIBRI/DDRAGO, VLT/X-shooter, TRT, MASTER | INTEGRAL SPI-ACS and PICsIT, GECAM-B | – |

References

- Remillard, R.A.; McClintock, J.E. X-Ray Properties of Black-Hole Binaries. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 44, 49–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komossa, S. Tidal disruption of stars by supermassive black holes: Status of observations. J. High Energy Astrophys. 2015, 7, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Zhang, B. The physics of gamma-ray bursts & relativistic jets. Phys. Rep. 2015, 561, 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.E.A. Multi-messenger Observations of a Binary Neutron Star Merger. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2017, 848, L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvaterra, R.; Della Valle, M.; Campana, S.; Chincarini, G.; Covino, S.; D’Avanzo, P.; Fernandez-Soto, A.; Guidorzi, C.; Tagliaferri, G.; Antonelli, L.A.; et al. GRB 090423 at a redshift of z 8.1. Nature 2009, 461, 1258–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W. The Einstein Probe mission. In Proceedings of the 44th COSPAR Scientific Assembly, Online, 16–24 July 2022. Abstract E1.16-0036-22. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Dai, L.; Feng, H.; Jin, C.; Jonker, P.; Kuulkers, E.; Liu, Y.; Nandra, K.; O’Brien, P.; Piro, L.; et al. Science objectives of the Einstein Probe mission. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2025, 68, 239501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Tirado, A.J.; Soldán, J.; Bernas, M.; Páta, P.; Rezek, T.; Hudec, R.; Sanguino, T.M.; de la Morena, B.; Berná, J.A. The Burst Observer and Optical Transient Exploring System (BOOTES). Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 1999, 138, 583–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.D.; Castro-Tirado, A.J.; Fernández-García, E.; Caballero-García, M.D.; Pérez-García, I.; Carrasco-García, I.M.; Castellón, A.; Pérez del Pulgar, C.; Reina Terol, A.J. The Burst Observer and Optical Transient Exploring System in the Multi-messenger Astronomy Era. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2023, 10, 952887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Tirado, A.J. Tracking transients night and day. Nat. Astron. 2023, 7, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, B.; Pasham, D.; Andreoni, I.; Hare, J.; Beniamini, P.; Troja, E.; Ricci, R.; Dobie, D.; Chakraborty, J.; Ng, M.; et al. Characterization of a peculiar Einstein Probe transient EP240408a: An exotic gamma-ray burst or an abnormal jetted tidal disruption event? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-García, M.D.; Jelínek, M.; Castro-Tirado, A.J.; Hudec, R.; Cunniffe, R. Initial follow-up of optical transients with COLORES using the BOOTES network. Acta Polytech. 2015, 55, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, K.C.; Magnier, E.A.; Metcalfe, N.; Flewelling, H.A.; Huber, M.E.; Waters, C.Z.; Denneau, L.; Draper, P.W.; Farrow, D.; Finkbeiner, D.P.; et al. The Pan-STARRS1 Surveys. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.05560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-García, M.D.; Simon, V.; Jelínek, M.; Castro-Tirado, A.J.; Cwiek, A.; Claret, A.; Opiela, R.; Żarnecki, A.F.; Gorosabel, J.; Oates, S.R.; et al. Early optical follow-up of the nearby active star DG CVn during its 2014 superflare. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 452, 4195–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, J.; Narkhede, N.; Rao, J. Kafka: A Distributed Messaging System for Log Processing. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Networking Meets Databases, Athens, Greece, 12 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Antognini, J.M.O. Timescales of Kozai–Lidov oscillations at quadrupole and octupole order in the test particle limit. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 452, 3610–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouveliotou, C.; Meegan, C.A.; Fishman, G.J.; Bhat, N.P.; Briggs, M.S.; Koshut, T.M.; Paciesas, W.S.; Pendleton, G.N. Identification of two classes of gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. J. 1993, 413, L101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sguera, V.; Barlow, E.J.; Bird, A.J.; Dean, A.J.; Landi, R.; Lubinski, P.; Malizia, A.; Ubertini, P. INTEGRAL observations of recurring fast X-ray transients. Astron. Astrophys. 2005, 444, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ling, Z.X.; Liu, Y.; Pan, X.; Jin, C.; Cheng, H.Q.; Cui, C.Z.; Fan, D.W.; Hu, H.B.; Hu, J.W.; et al. Detection of a Bright X-Ray Flare by Einstein Probe in Its Commissioning Phase; Astronomer’s Telegram, No. 16463; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, H.; Yin, Y.H.I.; Yang, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, X. EPW20240219aa Is Likely a GRB Event; Astronomer’s Telegram, No. 16473; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.H.I.; Zhang, B.B.; Yang, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, C.; Shao, Y.X.; Hu, Y.D.; Zhu, Z.P.; Xu, D.; An, L.; et al. Triggering the Untriggered: The First Einstein Probe-Detected Gamma-Ray Burst 240219A and Its Implications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.10156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Xu, D.; Svinkin, D.S.; Delaunay, J.; Tanvir, N.R.; Gao, H.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.F.; et al. Soft X-ray prompt emission from a high-redshift gamma-ray burst EP240315a. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.16425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levan, A.J.; Jonker, P.G.; Saccardi, A.; Malesani, D.B.; Tanvir, N.R.; Izzo, L.; Heintz, K.E.; Sánchez, D.M.; Quirola-Vásquez, J.; Torres, M.A.; et al. The fast X-ray transient EP240315a: A z 5 gamma-ray burst in a Lyman continuum leaking galaxy. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.16350. [Google Scholar]

- Tanvir, N.R.; Fox, D.B.; Levan, A.J.; Berger, E.; Wiersema, K.; Fynbo, J.P.U.; Cucchiara, A.; Krühler, T.; Perley, D.A.; Cenko, S.B.; et al. A γ-ray burst at a redshift of z∼8.2. Nature 2009, 461, 1254–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, R.; Troja, E.; Yang, Y.H.; Yadav, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Wu, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, W. Long-term radio monitoring of the fast X-ray transient EP240315a: Evidence for a relativistic jet. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.18311. [Google Scholar]

- Gillanders, J.H.; Rhodes, L.; Srivastav, S.; Carotenuto, F.; Bright, J.; Huber, M.E.; Stevance, H.F.; Smartt, S.J.; Chambers, K.C.; Chen, T.W.; et al. Discovery of the optical and radio counterpart to the fast X-ray transient EP240315a. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.10660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Yuan, W.; Ling, Z.; Chen, Y.; Rea, N.; Rau, A.; Cai, Z.; Cheng, H.; Zelati, F.C.; Dai, L.; et al. Einstein Probe discovery of EP240408a: A peculiar X-ray transient with an intermediate timescale. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2024, 68, 219511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, W.X.; Liu, L.D.; Gao, H.; Wang, X.F.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, B.; Filippenko, A.V.; Xu, D.; An, T.; et al. Extragalactic fast X-ray transient from a weak relativistic jet associated with a Type Ic-BL supernova. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2410.02315. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastav, S.; Chen, T.W.; Gillanders, J.H.; Rhodes, L.; Smartt, S.J.; Huber, M.E.; Aryan, A.; Yang, S.; Beri, A.; Cooper, A.J.; et al. Identification of the optical counterpart of the fast X-ray transient EP240414a. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 978, L21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, J.S.; Carotenuto, F.; Fender, R.; Choza, C.; Mummery, A.; Jonker, P.G.; Smartt, S.J.; DeBoer, D.R.; Farah, W.; Matthews, J.; et al. The Radio Counterpart to the Fast X-ray Transient EP240414a. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.19055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dalen, J.N.; Levan, A.J.; Jonker, P.G.; Malesani, D.B.; Izzo, L.; Sarin, N.; Quirola-Vásquez, J.; Sánchez, D.M.; de Ugarte Postigo, A.; van Hoof, A.P.; et al. The Einstein Probe transient EP240414a: Linking Fast X-ray Transients, Gamma-ray Bursts and Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 982, L47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xue, R.; Buckley, D.; Howell, D.A.; Jin, C.; Li, W.; Monageng, I.; Pan, H.; et al. Detection of an Orphan X-ray Flare from a Blazar Candidate EP240709a with Einstein Probe. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.18463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Hare, J.; Jaisawal, G.K.; Malacaria, C.; Markwardt, C.B.; Sanna, A. Tentative Blazar Candidate EP240709A Associated with 4FGL J0031.5-5648: NICER and Archival Multiwavelength Observations. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.18718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).