Return to Martial Arts after Surgical Treatment of the Cervical Spine: Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature for an Evidence-Based Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

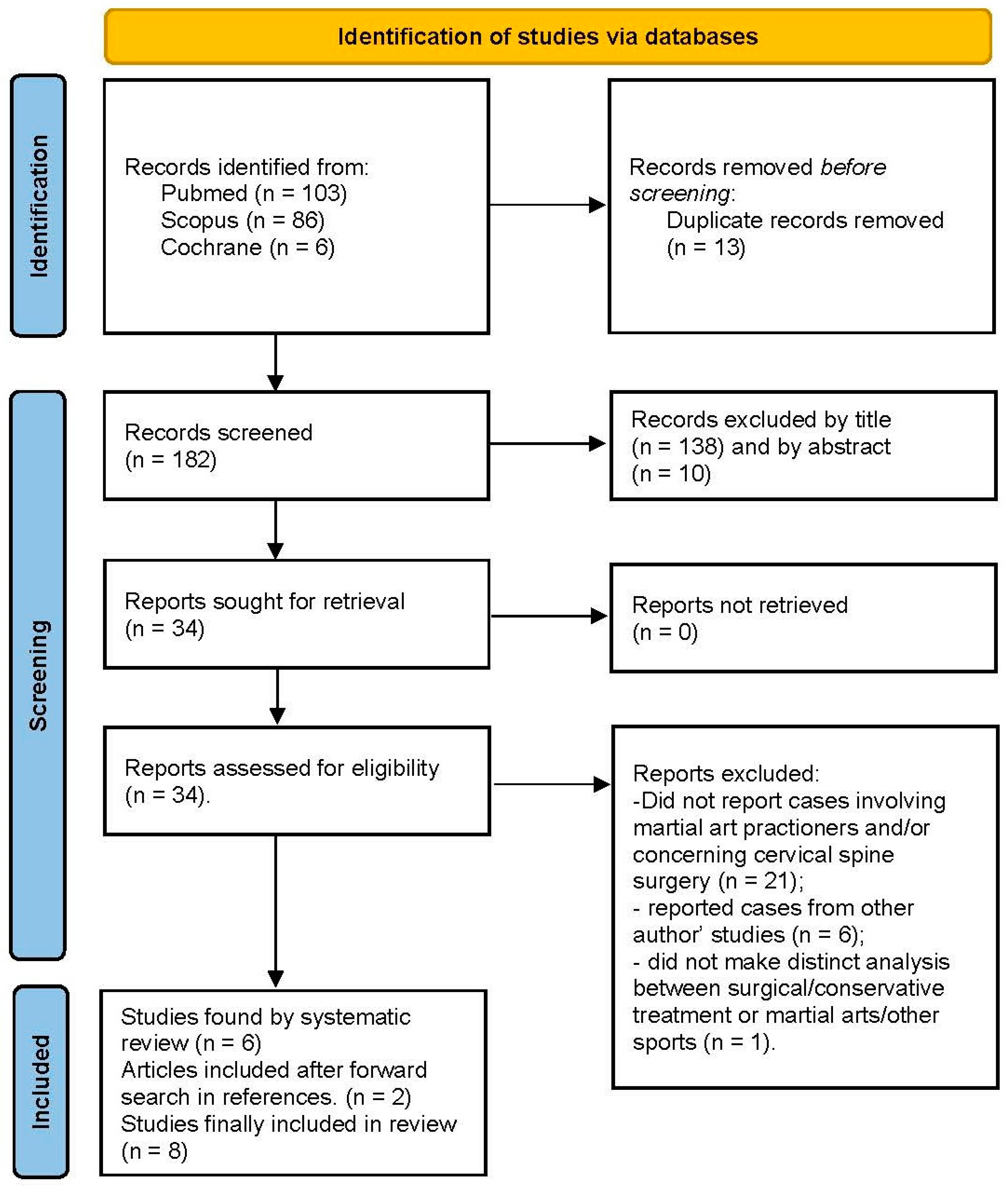

2. Materials and Methods

- the study population comprises one or more athletes who practice martial arts that underwent surgical treatment of the cervical spine;

- return-to-play mentioned in the text.

3. Results

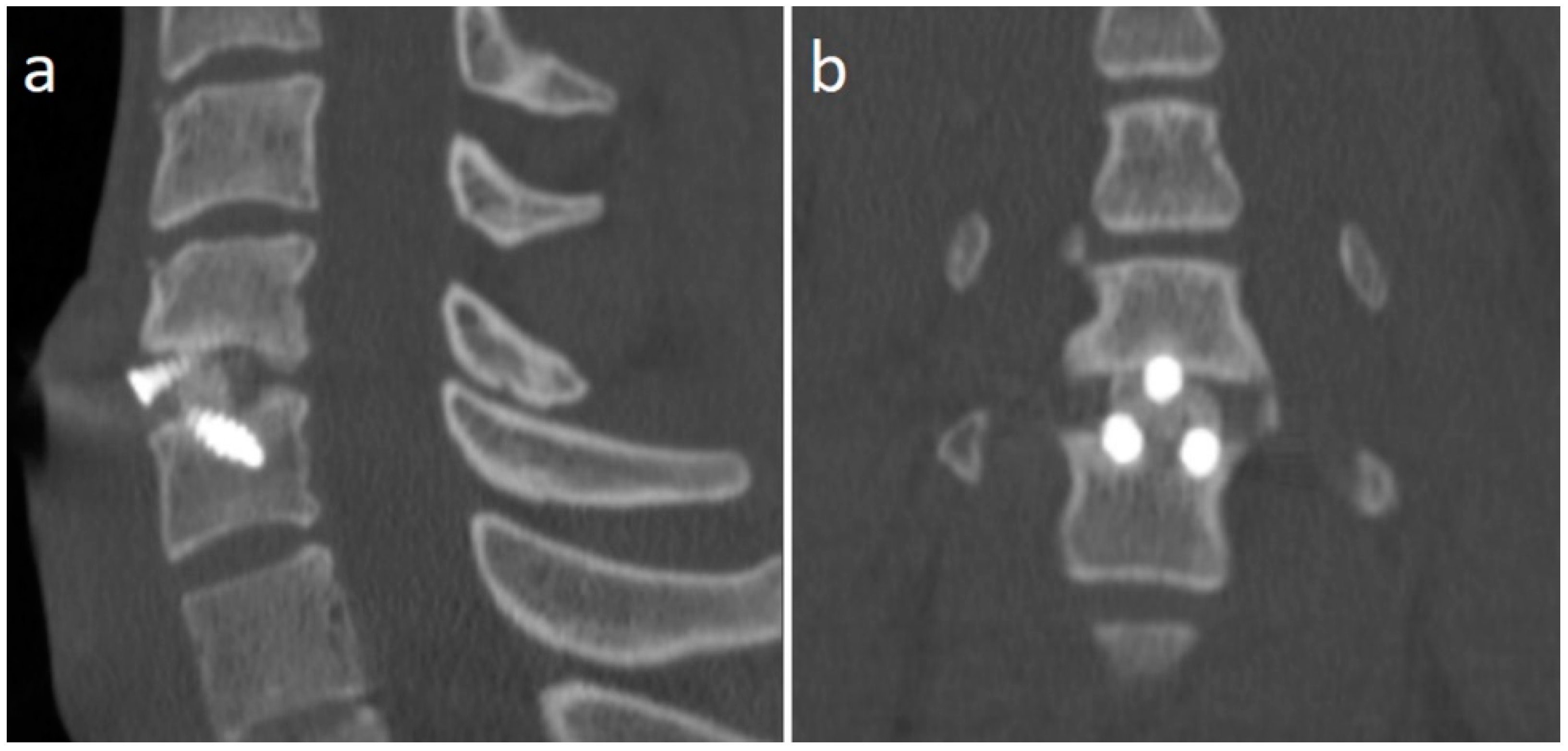

Case Report

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maroon, J.C.; Bailes, J.E. Athletes with Cervical Spine Injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996, 21, 2294–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, G.D.; Canseco, J.A.; Patel, P.D.; Hilibrand, A.S.; Kepler, C.K.; Mirkovic, S.M.; Watkins, R.G.; Dossett, A.; Hecht, A.C.; Vaccaro, A.R. Updated Return-to-Play Recommendations for Collision Athletes After Cervical Spine Injury: A Modified Delphi Consensus Study With the Cervical Spine Research Society. Neurosurgery 2020, 87, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, W.K. Outcomes Following Nonoperative and Operative Treatment for Cervical Disc Herniations in National Football League Athletes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011, 36, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, B.P.; Lin, W.; Young, M.; Mueller, F.O. Catastrophic Injuries in Wrestlers. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2002, 30, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroon, J.C.; Bost, J.W.; Petraglia, A.L.; LePere, D.B.; Norwig, J.; Amann, C.; Sampson, M.; El-Kadi, M. Outcomes After Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion in Professional Athletes. Neurosurgery 2013, 73, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasa, T.; Yoshizumi, Y.; Imada, K.; Aoki, M.; Terai, T.; Koizumi, T.; Goel, V.K.; Faizan, A.; Biyani, A.; Sakai, T.; et al. Cervical Spondylolysis in a Judo Player: A Case Report and Biomechanical Analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2009, 129, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torg, J.S.; Guille, J.T.; Jaffe, S. Injuries to the Cervical Spine in American Football Players. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 2002, 84, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiatek, P.R.; Nandurkar, T.S.; Maroon, J.C.; Cantu, R.C.; Feuer, H.; Bailes, J.E.; Hsu, W.K. Return to Play Guidelines After Cervical Spine Injuries in American Football Athletes: A Literature-Based Review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021, 46, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.R.; Schroeder, G.D.; Hecht, A.C.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Watkins, R.G.; Watkins, R.; Basques, B.A. Letter to the Editor Regarding “Return to Play Guidelines After Cervical Spine Injuries in American Football Athletes: A Literature-Based Review”. Spine 2021, 46, E1225–E1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Minami, K.; Arai, T.; Okamura, Y.; Nakamura, T. Cervical Spinal Cord Injury in Sumo Wrestling: A Case Report. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2004, 32, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigal, R.; Batjer, H.H.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; Berger, M.S. Return to Play for Neurosurgical Patients. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempel, Z.J.; Bost, J.W.; Norwig, J.A.; Maroon, J.C. Significance of T2 Hyperintensity on Magnetic Resonance Imaging After Cervical Cord Injury and Return to Play in Professional Athletes. Neurosurgery 2015, 77, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayana Kurup, J.K.; Jampani, R.; Mohanty, S.P. Catastrophic Cervical Spinal Injury in an Amateur College Wrestler. BMJ Case Report. 2017, bcr-2017-220260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, J.M.V.; Sane, J.C.; Diao, S.; Sy, M.H. Spinal Cord Injury Due to Cervical Disc Herniation without Bony Involvement Caused by Wrestling—A Case Report. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2019, 9, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Bharuka, A.; Gadiya, A.; Nene, A. Assessment of Outcomes of Spine Surgery in Indian Athletes Involved in High-End Contact Sports. Asian Spine J 2021, 15, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindi-Sugino, R.; Hartl, R.; Klezl, Z. Cervical Arthroplasty in a Professional Kick-Boxing Fighter, 7 Years Follow-Up. Acta Ortop. Mex. 2021, 35, 282–285. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.; Jones, A.; Davies, P.R.; Howes, J.; Ahuja, S. Is Return to Professional Rugby Union Likely after Anterior Cervical Spinal Surgery? J. Bone Jt. Surgery Br. Vol. 2008, 90-B, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, C.D.; Capo, J. Cervical Spinal Cord Contusion in Professional Athletes: A Case Series With Implications for Return to Play. Spine 2013, 38, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.T.; Chun, D.S.; Schneider, A.D.; Hecht, A.C.; Maroon, J.C.; Hsu, W.K. The Difference in Clinical Outcomes After Anterior Cervical Fusion, Disk Replacement, and Foraminotomy in Professional Athletes. Clin. Spine Surg. A Spine Publ. 2018, 31, E80–E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R.G.; Chang, D.; Watkins, R.G. Return to Play After Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion in Professional Athletes. Orthop. J. Sport. Med. 2018, 6, 232596711877967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tator, C.H. Recognition and Management of Spinal Cord Injuries in Sports and Recreation. Neurologic Clinics 2008, 26, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccaro, A.R.; Klein, G.R.; Ciccoti, M.; Pfaff, W.L.; Moulton, M.J.R.; Hilibrand, A.J.; Watkins, B. Return to Play Criteria for the Athlete with Cervical Spine Injuries Resulting in Stinger and Transient Quadriplegia/Paresis. Spine J. 2002, 2, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccaro, A.R.; Watkins, B.; Albert, T.J.; Pfaff, W.L.; Klein, G.R.; Silber, J.S. Cervical Spine Injuries in Athletes: Current Return-to-Play Criteria. Orthopedics 2001, 24, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar]

| Authors and Year | Number of Cases | Age and Sex | Sport | Intervention | Level of Intervention | Time of Follow-Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakagawa et al. (2004) [10] | 1 case | 19, M | sumo (n = 1) | repositioning and posterior fixation (I stage), anterior cervical body fusion (II stage) | C7-T1 (n = 1) | 1 year | RTP in 0%. Wheelchair mobilization after surgery |

| Maroon et al. (2013) [5] | 8 cases | 29 ± 2,3 (range, 22–40 years), unspecified sex | wrestling (n = 8) | ACDF (n = 8) | C5-C6 (n = 7); C6-C7 (n = 1) | MD | RTP in 100% (n = 8). Time to RTP = 3–12 months (average 4.3 ± 3.0). One patient retired after RTP due to the persistence of chronic neck pain with radiculopathy |

| Saigal et al. (2014) [11] | 9 cases | MD | wrestling (n = 4) other unspecified martial art (n = 5) | variable (not discussed) | variable | MD | RTP in 75% of wrestlers (n = 3). Time to RTP = 3–6 months (66.7%); 6 months–1 year (33.3%). One patient developed a second cervical disc herniation that did not require surgical treatment. RTP in 100% of other martial art practitioners (n = 5). Time to RTP = 1–3 months (25%), 3–6 months (50%), 6 months–1 year (25%) |

| Tempel et al. (2015) [12] | 1 case | 31, M | wrestling (n = 1) | ACDF | C5-6 (n = 1) | 3 years | RTP in 100% (n = 1). Time to RTP = 9 months. No complication reported after RTP |

| Kurup, Jampani et al. (2017) [13] | 1 case | 19, M | wrestling (n = 1) | C7 corpectomy, stabilization and fusion through an anterior approach (n = 1) | C6-T1 (n = 1) | 6 months | RTP in 0%. Wheelchair mobilization after surgery. |

| Hope et al. (2019) [14] | 1 case | 23, M | wrestling (n = 1) | Anterior cervical discectomy, interbody fusion using autologous iliac crest graft and ventral stabilization using a cervical plate (n = 1) | C3-4 (n = 1) | 5 years | RTP in 100% (n = 1). Time to RTP = more than 6 months. No complication reported after RTP |

| Shah et al. (2021) [15] | 1 case | MD | wrestling (n = 1) | ACDF | C5-6 (n = 1) | 3 years | RTP in 100% (n = 1). Time to RTP = 3 months. No complication reported after RTP |

| Lindi-Sugino et al. (2021) [16] | 1 case | 34, F | kick-boxing (n = 1) | TDR | C5-6 (n = 1) | 7 years | RTP in 100% (n = 1). Time to RTP = 3 months. No complication reported after RTP |

| Our article | 1 case | 21, M | judo (n = 1) | ACDF | C5-6 (n = 1) | 1 year | RTP in 100% (n = 1), Time to RTP = 7 months. No complication reported after RTP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Monaco, G.; Mazzucchi, E.; Pignotti, F.; La Rocca, G.; Sabatino, G. Return to Martial Arts after Surgical Treatment of the Cervical Spine: Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature for an Evidence-Based Approach. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13010003

Di Monaco G, Mazzucchi E, Pignotti F, La Rocca G, Sabatino G. Return to Martial Arts after Surgical Treatment of the Cervical Spine: Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature for an Evidence-Based Approach. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Monaco, Giuliano, Edoardo Mazzucchi, Fabrizio Pignotti, Giuseppe La Rocca, and Giovanni Sabatino. 2023. "Return to Martial Arts after Surgical Treatment of the Cervical Spine: Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature for an Evidence-Based Approach" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13010003

APA StyleDi Monaco, G., Mazzucchi, E., Pignotti, F., La Rocca, G., & Sabatino, G. (2023). Return to Martial Arts after Surgical Treatment of the Cervical Spine: Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature for an Evidence-Based Approach. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13010003