Abstract

The use of pharmacogenomic (PGx) tests is increasing, but there are not standard approaches to counseling patients on their implications or results. To inform approaches for patient counseling, we conducted a scoping review of published literature on patient experiences with PGx testing and performed a thematic analysis of qualitative and quantitative reports. A structured scoping review was conducted using Joanna Briggs Institute guidance. The search identified 37 articles (involving n = 6252 participants) published between 2010 and 2021 from a diverse range of populations and using a variety of study methodologies. Thematic analysis identified five themes (reasons for testing/perceived benefit, understanding of results, psychological response, impact of testing on patient/provider relationship, concerns about testing/perceived harm) and 22 subthemes. These results provide valuable context and potential areas of focus during patient counseling on PGx. Many of the knowledge gaps, misunderstandings, and concerns that participants identified could be mitigated by pre- and post-test counseling. More research is needed on patients’ PGx literacy needs, along with the development of a standardized, open-source patient education curriculum and the development of validated PGx literacy assessment tools.

1. Introduction

Pharmacogenomic (PGx) testing is increasingly entering mainstream clinical practice and is of great interest to patients and providers [1]. Numerous healthcare systems are implementing PGx programs [2,3,4,5,6,7,8], and statewide initiatives to implement PGx testing are also underway [9,10]. As the clinical utility and uptake of PGx has grown, conversations about PGx have shifted from “should we do PGx testing?” to “how should we best implement PGx testing?” As guideline-producing groups, such as the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium [11], develop recommendations for how to best apply the scientific evidence, and as clinicians and implementation scientists [12] develop best practices for clinical implementation, there is one critical voice that must be heard: the patient. Understanding how patients perceive PGx is essential for providers to be able to anticipate their questions, concerns, and/or needs and to inform the counseling that clinicians provide prior to and after PGx testing.

The subject of patient counseling for PGx testing has received little attention. Patient and provider literacy for genetics in general has been described as insufficient and is frequently cited as a barrier to PGx implementation [13,14]. Moreover, specific PGx literacy needs have, to our knowledge, never been empirically identified outside of one study that examined the impact of objective numeracy on accurate interpretation of PGx results [15]. Given the paucity of direct research on PGx patient counseling, we conducted a scoping review of published literature on patient experiences with PGx testing.

The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with PGx testing among patients and the general public. Specific objectives were to (1) conduct a systematic search of published literature for assessments of patient knowledge of PGx, (2) perform a thematic analysis of qualitative and quantitative reports of patient experiences, and (3) discuss implications of the analysis for patient counseling for PGx testing.

2. Materials and Methods

Given the varied nature of patient experiences with PGx testing and the predominantly qualitative nature of the data, a scoping review was deemed to be the best methodology for our analysis, as opposed to meta-analysis [16]. Our protocol followed published guidance from the Joanna Briggs Institute on the conduct of scoping reviews [17] and adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review—Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist [18]. The protocol was registered on 21 November 2021 in the Open Science Foundation Registry (https://osf.io/registries/discover; doi:10.17605/osf.io/gqfky).

2.1. Literature Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

A systematic PubMed search was performed on 28 October 2021 using the discrete search string “(patient OR consumer OR public) AND (Pharmacogen*) AND (literacy OR education OR knowledge OR understanding OR perception* OR perspective* OR view* OR attitude*)”. Filters on the search included English language, abstract included, and published after 1 January 2010. The rationale for this date is that the early 2010s marked the launch of several commercial multi-gene panels that soon became the industry standard approach and represents a transition point to more “modern” approaches to PGx testing. Articles meeting search criteria underwent title/abstract review. Full texts were downloaded and evaluated by the author (J.D.A.). Questionable articles were refereed by the senior author (J.R.B.).

Eligible articles represented studies that enrolled patients, consumers, undergraduate students, or the general public. Studies must have queried individuals about PGx testing but participants did not have to receive testing to be eligible. Eligible study designs included closed-ended surveys, open-ended surveys, semi-structured interviews, focus groups, or qualitative reviews of primary data sources.

Studies of populations that included healthcare providers, health professional students, and other stakeholders (e.g., government, laboratories, managed care, etc.) were excluded. Studies that queried individuals about disease risk genomics, somatic tumor testing, or direct-to-consumer testing were also excluded. Ineligible study designs included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical outcomes trials, and clinical guidelines. Studies that reported unanchored Likert-style questions (e.g., 4.1 out of 5 on patient satisfaction) without reporting summary statistics (e.g., 80% of patients were somewhat or very satisfied) were excluded. Unpublished data, preprints, and grey literature were also excluded. Given the broad, qualitative nature of eligible articles, numeric ratings of article quality were not performed.

2.2. Data Elements

For each eligible article, the following characteristics were extracted: sample size, study population, study methodology, and whether study participants received PGx testing (yes/no—studies with mixed PGx tested and control populations were coded as “yes”). Data elements related to patient knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and/or experiences with PGx testing were extracted. Due to the broad study designs included in the scoping review, data elements for a given article could include:

- Direct quotes from participants (e.g., “I was satisfied with my PGx testing”).

- Quotes from participants that are summarized or paraphrased by study authors, if no representative direct quote was present (e.g., “Many patients reported satisfaction with PGx testing”).

- Statistics from specific questionnaire items (e.g., “80% of patients were satisfied with PGx testing”).

2.3. Data Extraction and Thematic Analysis

Data elements were extracted manually into AtlasTi Web [19], a standard tool for qualitative review. An initial codebook was developed based on review of a subset of articles by J.D.A. This codebook was developed, reviewed, and refined by the author group. After the codebook was finalized, thematic analysis of the entire dataset was conducted independently by J.D.A. and A.L.P. Discrepancies in coding were discussed between J.D.A. and A.L.P., with J.R.B. acting as tiebreaker.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

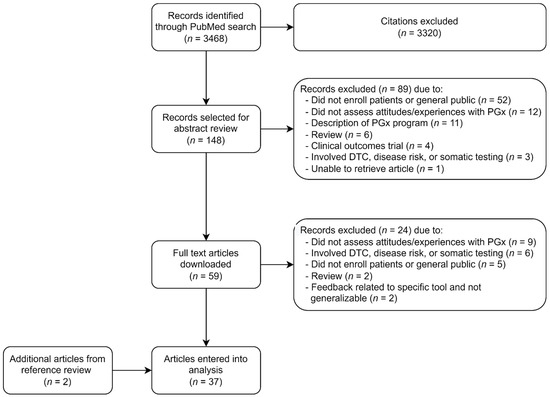

The PubMed search conducted in October 2021 identified 3468 potentially relevant citations. After title screening, 148 records were selected for abstract review. Only one article could not be retrieved and was not included in the review [20]. After abstract review, 59 full text articles were downloaded. Of these, 35 met eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. An additional two articles were identified upon reference review of eligible articles and also included in the analysis, for a final total of 37 articles [1,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Figure 1 summarizes the identification and selection process for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Review flowchart. Abbreviations: PGx, pharmacogenomic; DTC, direct to consumer.

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

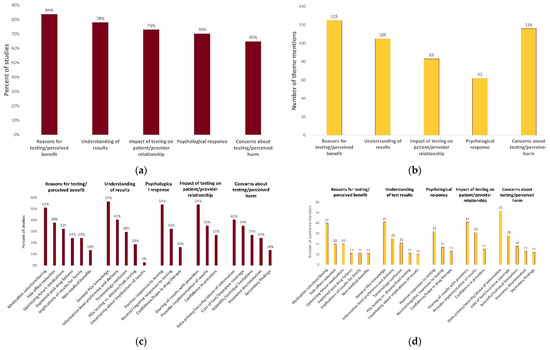

Characteristics of eligible articles are reported in Table 1. All included studies were published between 2010 and 2021, with 49% (18/37) published since 2019. The total sample size across all studies was 6252 participants from a diverse range of populations. Forty-nine percent (18/37) of studies enrolled participants who had previously received PGx testing or received PGx testing as part of the study. Study methodologies included closed-ended questionnaires (n = 12) focus groups (n = 11), semi-structured interviews (n = 7), open-ended questionnaires (n = 3), or a mixed-methodological approach (n = 3). One retrospective qualitative review of correspondence between patients and genetic counselors was also included [52]. A total of 488 data elements were extracted from the included studies. Following thematic analysis, five major themes emerged and 22 subthemes emerged (Table 2). The frequency and distribution of these themes and subthemes is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Included studies and their characteristics.

Table 2.

Themes, subthemes, and representative quotations from included studies.

Figure 2.

Distribution and frequency of themes and subthemes. (a) Percent of studies expressing each theme; (b) number of theme mentions across included studies; (c) percent of studies expressing each subtheme; (d) number of subtheme mentions across included studies.

3.3. Theme 1: Reasons for Testing/Perceived Benefit

3.3.1. Subtheme: Improved Medication Selection/Dosing

The most common theme observed across studies was an exploration of the reason for testing/perceived benefit. Participants across studies commonly identified the potential for improved medication selection/dosing as their primary motivation for testing. A large survey of the general public by Haga et al. [1] found that >90% of individuals would be likely to undergo PGx testing to predict drug effectiveness or initial dosing of a medication. This theme was also observed in participants who had received PGx testing. For example, 100% of the 150 participants in the study by Lemke et al. [33] identified helpfulness in optimizing treatment as a factor in their decision to undergo testing. Importantly, participants often spoke of testing as being able to identify the “best” medication, indicating a belief that PGx may be able to identify the one treatment that would provide the most optimal outcome for individuals. Over 75% of participants in both Haga et al. [29] and Daud et al. [30] agreed that testing would help their physician “select the best medication for them.”

3.3.2. Subtheme: Side Effect Reduction

Reduction in side effects was another common expected benefit of PGx testing. Most (78%) of participants in the study by Olson et al. [35] somewhat or strongly agreed that using PGx results when prescribing medication will reduce their risk of side effects. Studies by Haga et al. [1] and Daud et al. [30] reported similar percentages of individuals interested in this benefit (73% and 72%, respectively). As one participant in Deininger et al. [39] stated, “I would definitely agree (to PGx testing). I’m the type of person that gets those weird side effects that no one else gets.”

3.3.3. Subtheme: Optimization of Future Medications

In addition to optimizing current or imminently prescribed medications, in ~1/3 of the included studies, participants also spoke of the value of PGx testing for future medication decisions. Over 80% of the participants in Lemke et al. [33] agreed that PGx testing would be helpful to them in the future. For example, one participant in Truong et al. [53] stated, “I’d like (the PGx results) for every time I get prescribed a new medicine or change.”

3.3.4. Subtheme: Explanation of Previous Med Failures and Non-Medical Benefits

Other notable benefits of testing did not involve immediate or future improvement in medication outcomes. Eleven studies identified that patients valued how PGx test results could contextualize previous medication experiences. Nearly 70% of the participants in Lemke et al. [33] felt “more validated about previous medication experiences” after undergoing PGx testing. Some participants described self-curiosity as a reason for testing. For example, Waldman et al. [45] stated, “Many participants expressed that the PGx testing experience had personal utility, even when (healthcare providers) did not act on medication suggestions. These participants expressed the value they placed on information and knowledge acquisition.” Others underwent PGx testing for altruistic reasons (e.g., a desire to help further research). Finally, while not necessarily the primary reason for testing, many participants expressed interest in the potential benefits of PGx for family members with health conditions. For example, one participant in Schmidlen et al. [52] queried, “I need info on my CYP2C9 results and how they are genetically carried to my children. I have a child in critical care that may need this info.”

3.4. Theme 2: Understanding of PGx Concepts and Results

3.4.1. Subtheme: General Pharmacogenomics Knowledge

General knowledge of genomics, pharmacology, and PGx varied widely across patient populations. While 88% of respondents in Haga et al. [29] “reported that they understood how genetic testing can be used in healthcare very well or somewhat well, and while a substantial number of participants (64%) in Pereira et al. [43] were confident of their ability to understand genetic information, participants often struggled when actually presented with test results. Less than half of participants (45%) in Olson et al. [35] were “a little” or “not at all” confident in being able to explain their PGx results to a friend or family member. Participants sometimes struggled to identify how genomic information could be applicable to specific medication classes, such as antidepressants. In contrast, 95% of participants in the study by Liko et al. [49] could describe the PGx test. Importantly, and related to reasons for developing approaches for PGx education, these participants had undergone counseling by a pharmacist before and after receiving their results.

3.4.2. Subtheme: Differences in Information Level Preference and Delivery

Participants were often split on the depth and breadth of information they wanted to receive with respect to their PGx results. As Mills et al. [38] noted, “Two patient participants indicated inclusion of genotype information was not useful; however, another stated that he ‘wants to know everything (because the more information) you give, the more knowledge patients have…” In other cases, as Jones et al. noted [36], “Some patients requested to know everything about the result, ‘I’d like to know as much as I can;’ however, after reviewing the mock report, they thought that some sections of the report had too much information.”

This difference in information level preference may relate to patients’ preferred method of information delivery. Some participants stated that they preferred to receive PGx information from a healthcare provider, while others preferred to look it up themselves. Lemke et al. [33] found that 40% of participants looked up additional information about their results, while 35.7% wanted additional follow-up from a provider to discuss their results. Nearly 1 in 8 participants in Lemke et al. made changes to their medication regimen on their own.

3.4.3. Subtheme: Terminology Confusion

The terminology commonly used in the PGx field and on test reports often posed a barrier to patient understanding. As an example, only 17% of participants in Daud et al. [30] were aware of the meaning of the term “pharmacogenetics.” While some participants were able to break apart the word, others found it incomprehensible (“I don’t even know what that means.” [49]). Patients in the 2018 paper by Mills et al. [38] reviewing PGx educational material, “expressed concern about potentially confusing terminology. Two patient participants felt the term ‘metabolize’ needed a better definition, with one pointing out the risk of confusing it with ‘metabolism of food.’ One also worried that some patients may not be familiar with the term ‘enzyme.’” All participants in Asiedu et al. [46] “expressed concerns about the medical/technical terms such as ‘metabolize,’ ‘metabolic status,’ and ‘phenotype’.

3.4.4. Subtheme: Confusion between PGx Testing vs. Disease/Trait Testing

Another common (and persistent) source of confusion was the difference between PGx testing and disease risk or trait testing. Trinidad et al. [28] noted this refrain throughout the seven focus groups they performed: “most understood the purpose of genetic testing to be predicting one’s susceptibility to heritable illness.” Lee et al. [32], talking to participants who had not received PGx testing, noted that the group “universally confused PGx with disease risk testing, in some cases continuing even after hearing a definition of PGx and its applications.” Likewise, Dressler et al. [40] noted, “Despite the informed consent process specifically indicating that testing would not provide any disease risk information, 60% of participants on the pretest survey expected to receive results on cancer risk. Although this misconception significantly decreased in the post-testing survey, we still observed this expectation in 49% of respondents.”

3.4.5. Subtheme: Uncertainty about Implications of Results for Care

One particular area of confusion that deserves special mention is patient uncertainty about the implications of their results for care. While this concept was only identified in the Schmidlen et al. [52] paper, it nevertheless came out strongly. Schmidlen et al. retrospectively reviewed PGx-related genetic counseling requests as part of a large trial and found that 54% of participants requesting genetic counseling for a PGx results were seeking general assistance with understanding their results. Commonly, participants alluded to uncertainty regarding whether they should or should not be taking a given medication based on their study result or had questions about how their results applied to other medications.

3.5. Theme 3: Impact of PGx Testing on the Patient/Provider Relationship

3.5.1. Subtheme: Sharing of Results with Providers

Most participants desired to have their PGx results shared with their healthcare provider. In Haga et al. [29], 92% of participants said that they would share the results with other prescribers. In Lanting et al. [48], 74% of respondents planned to discuss results with their physicians, 37% reported doing so at follow up in a regular appointment, and 5% did so at a separate appointment. Many participants discussed the question of who would be the best provider to prescribe, interpret, and implement the PGx results. Most participants agreed that their primary care physician should have access, and many also wanted specialty physicians to have access if it was relevant to their practice. Moreover, participants often had an expectation that PGx results would immediately become a part of their medical record and therefore both accessible and actionable to all physicians.

Participants were more hesitant to share results with their pharmacist. While some participants felt their pharmacist was in the best position to monitor and act upon this information, many were unclear about whether pharmacists were adequately trained or appropriately positioned to act upon the information. Only 6.3% of participants in Waldman et al. [43] reported that they shared and discussed their PGx results with a pharmacist. Waldman et al. [45] stated, “of those who did not disclose their PGx results to a pharmacist (93.7%, n = 30), one participant stated that they “would probably rely on his or her doctor to prescribe the right medications based on the results,” and another stated that they “hadn’t thought of it prior to this survey”.

3.5.2. Subtheme: Provider Implementation of Results

When PGx results were shared with healthcare providers, the response from providers varied. In Lanting et al. [48], 71% of conversations with healthcare providers were scored by participants as “very good,” while 13% were scored as “very bad.” In Waldman et al. [45], 87.1% of participants reported no changes to their medication regimen based on their PGx results. Of these, 44.4% reported that their medication regimen was already consistent with their PGx results, while 18.5% reported that their healthcare provider did not feel the need to change their medical care because of their PGx results. Many participants reported that providers were skeptical of the results or did not know how to properly implement them.

On the other hand, an additional concern raised by some participants was the potential for providers to rely on PGx testing to the exclusion of other factors. Some identified that genetic variation was only one factor in medication response and wanted their providers to practice a more holistic approach to medication selection.

3.5.3. Subtheme: Confidence in Providers

Participants generally reported trusting their healthcare providers about the decision to undergo PGx testing. A total of 59% of participants in both Haga et al. [1] and Daud et al. [30] underwent testing based on physician recommendation. In Pereira et al. [43], 75% of participants felt comfortable if their physician recommended genetic testing to guide their healthcare. Participants also expressed more confidence in providers who did take the time to understand and implement their PGx results. In Lemke et al. [33], 57% of participants agreed that they would be more likely to take medications prescribed by the provider if those decisions were informed by PGx testing. Participants felt that PGx testing made providers more informed and more “cutting edge”.

3.6. Theme 4: Psychological Response to PGx Testing

3.6.1. Subtheme: Positive Psychological Responses to Testing

Participants first learning about PGx testing commonly had a positive response. In a survey by Haga et al. [1], 65% of respondents were extremely or somewhat likely to undergo PGx testing after being informed of the risks. This number increased to 82% after learning more about the uses of PGx testing. This positive response frequently remained after receiving their PGx results. Participants in Lanting et al. [48] reported that knowing their PGx profile was “comforting” (89%), “useful” (92%) and that PGx testing “did not frighten them” (88%). In Olson et al. [35], 60% of respondents said they would encourage others to get CYP2D6 testing done, while 65% somewhat or strongly agreed that if more PGx tests became available they would ask their healthcare provider to order them.

3.6.2. Subtheme: Confidence/Hope in Medication Therapy

One frequently repeated positive response was that of improved confidence and/or hope in medication response as a result of PGx testing. Lemke et al. [33], querying individuals who underwent PGx testing, found that 73% of them felt more confident that the medications prescribed will not cause side effects. Some individuals brought up a tendency for healthcare provider to discount or pathologize patients’ experiences of medication side effects and expressed hope that PGx testing would provide a physiological basis for those experiences. As one participant in Frigon et al. [41] related, “…if an individual was not responding to a treatment, then it meant that the individual was having somatic symptoms. That was the term we were using. I am happy that you are bringing this up because this might avoid people being told that they are having somatic symptoms.”

3.6.3. Subtheme: Neutral/Negative Responses

Positive responses to PGx testing were not universal. Some participants expressed negative responses about undergoing testing, including feelings of skepticism that results would be helpful or unspecified fears. Some individuals who received PGx testing felt underwhelmed about the results. One-third of individuals in Haga et al. [29] indicated they felt nervous or anxious about their results. Others felt more neutral about the subject and either did not remember their results or did not feel PGx testing strongly impacted their life either positively or negatively. Interestingly, one participant specifically mentioned a concern relating to informed consent: “I don’t feel comfortable with my grandmother coming in here and being informed about what she’s signing up for.” [25].

3.7. Theme 5: Concerns about PGx Testing and Perceived Harm

3.7.1. Subtheme: Data Privacy/Security/Abuse of Information

The primary concern shared by participants across 41% of the included studies was that of data privacy and security. Indeed, 40% of participants in Lemke et al. [33] indicated concern about privacy of data, while nearly 80% of respondents in the survey by Haga et al. [1] were “not very” or “not at all” likely to have PGx testing if there was a chance their DNA sample or test result could be shared without their permission. Participants expressed concern that information would be misused or inappropriately accessed, and could lead to targeting by pharmaceutical companies or misuse by employers, law enforcement agencies, or the government. Even within the context of the healthcare system, there were concerns about data privacy. However, other participants expressed a lack of concern about PGx information, and expressed willingness for health care providers to have access to the information as long as it was relevant to their practice.

3.7.2. Subtheme: Insurance Discrimination

A specific concern related to abuse of information was insurance discrimination. Over 30% of the participants in Lemke et al. [33] indicated concern about the potential for discrimination, while about three-quarters of respondents in O’Daniel et al. [23] “indicated fear of discrimination by employers and health insurers” as a major reason to not undergo PGx testing.

3.7.3. Subtheme: Cost/Insurance Coverage

Another major concern of many participants was the out-of-pocket cost and/or insurance coverage of the test. Lack of insurance coverage for testing was a “very important” or “somewhat important” reason for declining PGx testing among respondents in O’Daniel et al. [23]. In contrast, if the entire cost of testing was covered by insurance, 89% of respondents in Gibson et al. [31] said that they would be very likely to get one. Many participants speculated on the cost/benefit ratio of the testing, while others expressed concern over issues of equity if the testing was too expensive or led to medication recommendations that were unaffordable for a portion of the population. Others questioned the societal benefit of large-scale PGx testing.

3.7.4. Subtheme: Scientific/Technical Limitations

Some participants were worried about the scientific and technical limitations of the testing. These limitations included topics such as testing accuracy, convenience of testing (e.g., concerns about blood draws), and the breadth of medications included. One participant in Lee et al. [32] asked, “How accurate is this genetic testing related to medications? Is there enough track record? Is it on target?” Post-testing, some participants expressed concern about results either being unhelpful or not aligning with their prior experiences with medications. For example, a participant in Liko et al. [49] commented, “They said green about a drug that I had stopped years past that didn’t work. So I think that was the thing, like one of the greens was like no, that’s not a green.”

3.7.5. Subtheme: Secondary Findings

Some participants worried about secondary findings as a result of undergoing PGx testing. This was often connected to the concerns about insurance discrimination, i.e., that PGx testing would turn up additional findings that would then result in insurance discrimination. In Madadi et al., [22] there were “several reservations, spontaneously expressed by 15% of participants, toward some perceived facets of genetic application, namely, mutagenesis, pregnancy termination, genetic engineering, and/or testing for incurable genetic diseases.”

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, we analyzed the results from 37 articles that employed survey-style research as well as focus groups and semi-structured interviews. We identified five themes and 22 subthemes (Table 2) that provide a comprehensive understanding of the patient perspective regarding PGx testing and its implementation in patient care.

Each of the themes identified has implications for patient care and counseling with respect to PGx testing. Regarding the theme of reasons for testing/perceived benefit, the majority of participants were interested in testing to help address efficacy and safety of medications. Many held a belief that we may call “the myth of the perfect medication,” in which PGx testing will identify the exact medication that will provide the most optimal treatment for their condition. In a recent survey conducted by the authors at a state fair, 89% of members of the general public believed that “pharmacogenomics will tell you the best medication to treat your condition,” while 67% of members of the general public believed that “when deciding what medication is best for you, your genetic makeup is more important than age, weight, or other medications you are taking” (unpublished data). This tendency toward “genetic exceptionalism” (i.e., the idea that genetic information holds special significance over and above other types of clinical data), may lead to feelings of disappointment, anger, and failure if results do not align with patient expectations (as expressed in our “psychological responses” theme). Intriguingly, some participants underwent PGx testing for reasons unrelated to medication assessment. Some were interested in the results as a means of learning more about themselves (“self-curiosity”) or for altruistic reasons, such as to provide information for family members or to advance research. PGx providers should be aware of a patient’s reasons for undergoing PGx testing and tailor their messaging appropriately.

Regarding the theme of concerns about testing/perceived harm, we observed a general trend for participants to exhibit great enthusiasm for PGx testing initially, which tempered when they became more informed about the limitations of testing. Concerns about insurance discrimination, data privacy, abuse of information, and cost of testing were common. Here too, genetic exceptionalism may be at play, as it is unlikely that participants would be as concerned about others having access to other laboratory results (e.g., serum creatinine). While all genetic information comes with ethical, legal, and social concerns, PGx testing tends to pose fewer concerns than disease risk genomic testing [57]. Nevertheless, providers should ensure that patients are thoroughly educated on the entire chain of custody of their genomic information, how their results will be secured, and who will have access to the information. Test-specific limitations and talking points (e.g., allele coverage, secondary findings, etc.) should also be thoroughly addressed prior to the patient undergoing testing.

Regarding the theme of the impact of testing on the patient/provider relationship, participants had variable experiences with PGx testing in the context of the patient/provider relationship. Patients thought highly of providers who offered PGx, feeling that it would improve their ability to select medications that would be safe and effective. Use of PGx also signaled that providers were interested in practicing cutting edge medicine. Patients often had an expectation that providers would know how to interpret and implement their PGx results, and that results would be shared among their different healthcare providers. They frequently expressed disappointment when this was not the case. These findings speak to the need for comprehensive PGx education for all providers and for systems that allow PGx results to be shared among all providers involved in a patient’s care.

Patients also differed on which providers they felt would be the best for implementing PGx testing. Some preferred that it come from their primary care provider, while others wanted disease state specialists or genetics specialists to deliver the information. While pharmacy is often involved in driving PGx implementation within health systems [58], most participants did not feel that pharmacists would be the most appropriate individuals to implement PGx, possibly due to unfamiliarity with the role and education of a clinical pharmacist. This is in contrast to evolving data suggesting that pharmacists may be optimally positioned to educate patients and provide therapeutic recommendations that incorporate PGx data [59,60,61]. This speaks to the need for greater advocacy to improve the public’s perception of the roles of the pharmacist beyond traditional dispensing activities.

Patient understanding of PGx testing remains low. Patients struggled with nomenclature and frequently conflated PGx testing with disease risk genetic testing. These findings underscore the importance of pre-test education and counseling so that patients are able to make informed decisions about whether or not to undergo testing, how to interpret results, and to have an informed discussion with their provider about PGx-informed medication decisions. One open question for the field is how to assess patient PGx literacy to ensure adequate informed consent. Genomic literacy assessments exist in the disease risk literature [62,63,64,65], but none of these assessments include PGx-related content. The development of a PGx-specific knowledge assessment would greatly assist clinicians and researchers to assess the efficacy of PGx educational interventions.

One intriguing finding of our study was the subtheme of information level preference and delivery. There was wide variability between participants in terms of the depth of information they requested about PGx. Moreover, we found that for some participants, their information level preference was dynamic and changed based on the information presented and its salience to their questions. This poses a challenge for developers of PGx test reports, which typically require standardized, relatively static report formats. Future work should examine novel test formats that allow for scalable or customizable information levels tailored to patient (and clinician) preference.

Our paper adds valuable context to the evolving knowledge of what is important for PGx patient counseling. Many of the knowledge gaps, misunderstandings, and concerns that participants identified could be mitigated by robust pre- and post-test counseling. In Table 3 and Table 4, we outline several pre- and post-test counseling points that should be considered based on the themes we identified in our analysis. In a recent article that was published after we completed our analyses, Wake and colleagues [66] compared pre-test counseling themes across four pharmacist-led PGx clinical practices. The authors identified several similar themes across the four sites, including benefits, limitations, and concerns/risks of PGx testing. The article also outlines core elements of a PGx counseling session using the acronym PGX-DRUGS (Purpose and benefit of PGx testing, Genetic concepts, X-amples (“examples”), Drawbacks of PGx testing, Risks and concerns, Understand patient’s view of PGx testing, Game plan and process, and Sharing PGx results). The themes identified from this “expert opinion” perspective largely correspond to those identified in our “patient opinion” research and provide independent validation of our findings.

Table 3.

Pre-test counseling points.

Table 4.

Post-test counseling suggestions.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to summarize and synthesize patient attitudes and experiences with PGx testing among patients and the general public. We used a broad search strategy, encompassing nearly 3500 articles, thus ensuring high sensitivity. Our analysis used multiple independent reviewers to ensure reliability of findings.

A major limitation of the analysis includes the reliance on reports of qualitative findings, rather than direct analysis of the qualitative transcripts themselves. Reporting on qualitative results necessitates interpretation, selection, and simplification of content—all possible avenues for author bias to affect results. Further, some quotations were presented without their accompanying context, making their classification ambiguous at times.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Pharmacogenomics represents a first step towards mainstream genomic medicine; thus, assessing and improving patients’ PGx literacy is a critical factor that must be addressed. Our analysis has relevance for development and standardization of patient counseling for PGx, but more research is needed on patients’ PGx educational needs. An open-source patient-focused education curriculum would allow for more efficient development and delivery of PGx counseling. This curriculum needs to be standardized yet scalable to individual information level preference. Additionally, there is a need for validated knowledge assessments that can be used to gauge the effectiveness of PGx patient counseling. Together, these steps will allow us to provide patients with the right PGx education, at the right level, at the right time.

Author Contributions

J.D.A., A.L.P. and J.R.B. were all involved in the conceptualization, methodology, analyses, data curation, writing and funding acquisition for the project. J.R.B. provided overall supervision for the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Defining the Future Grant from the College of Neurologic and Psychiatric Pharmacists Foundation and a Samuel W. Melendy/William & Mildred Peters Summer Research Scholarship from the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

In the past twelve months, J.D.A. has served as a consultant to Tempus Labs, Inc., which offers PGx testing. J.R.B. has served as a consultant to OptumRx for drug information related activities unrelated to PGx. A.L.P. has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Haga, S.B.; O’Daniel, J.M.; Tindall, G.M.; Lipkus, I.R.; Agans, R. Survey of US public attitudes toward pharmacogenetic testing. Pharmacogenom. J. 2012, 12, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroz, P.; Michel, S.; Allen, J.D.; Meyer, T.; McGonagle, E.J.; Carpentier, R.; Vecchia, A.; Schlichte, A.; Bishop, J.R.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; et al. Development and Implementation of In-House Pharmacogenomic Testing Program at a Major Academic Health System. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 712602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matey, E.T.; Ragan, A.K.; Oyen, L.J.; Vitek, C.R.; Aoudia, S.L.; Ragab, A.K.; Fee-Schroeder, K.C.; Black, J.L.; Moyer, A.M.; Nicholson, W.T.; et al. Nine-gene pharmacogenomics profile service: The Mayo Clinic experience. Pharmacogenom. J. 2021, 22, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, J.; McDermott, J.; Qureshi, N.; Newman, W. Pharmacogenomic testing to support prescribing in primary care: A structured review of implementation models. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, M.J.; Crosby, S. Description of an Established, Fee-for-Service, Office-Based, Pharmacist-Managed Pharmacogenomics Practice. Sr. Care Pharm. 2019, 34, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liko, I.; Corbin, L.; Tobin, E.; Aquilante, C.L.; Lee, Y.M. Implementation of a pharmacist-provided pharmacogenomics service in an executive health program. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2021, 78, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arwood, M.J.; Dietrich, E.A.; Duong, B.Q.; Smith, D.M.; Cook, K.; Elchynski, A.; Rosenberg, E.I.; Huber, K.N.; Nagoshi, Y.L.; Wright, A.; et al. Design and Early Implementation Successes and Challenges of a Pharmacogenetics Consult Clinic. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunnenberger, H.M.; Biszewski, M.; Bell, G.C.; Sereika, A.; May, H.; Johnson, S.G.; Hulick, P.J.; Khandekar, J. Implementation of a multidisciplinary pharmacogenomics clinic in a community health system. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2016, 73, 1956–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.R.; Huang, R.S.; Brown, J.T.; Mroz, P.; Johnson, S.G.; Allen, J.D.; Bielinski, S.J.; England, J.; Farley, J.F.; Gregornik, D.; et al. Pharmacogenomics education, research and clinical implementation in the state of Minnesota. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.N.; Voora, D.; Bell, G.; Bates, J.; Cipriani, A.; Bendz, L.; Frick, A.; Hamadeh, I.; McGee, A.S.; Steuerwald, N.; et al. North Carolina’s multi-institutional pharmacogenomics efforts with the North Carolina Precision Health Collaborative. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. Available online: https://cpicpgx.org/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Sperber, N.R.; Dong, O.M.; Roberts, M.C.; Dexter, P.; Elsey, A.R.; Ginsburg, G.S.; Horowitz, C.R.; Johnson, J.A.; Levy, K.D.; Ong, H.; et al. Strategies to Integrate Genomic Medicine into Clinical Care: Evidence from the IGNITE Network. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.N.; Ursan, I.D.; Zueger, P.M.; Cavallari, L.H.; Pickard, A.S. Stakeholder views on pharmacogenomic testing. Pharmacotherapy 2014, 34, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, J.; Curry, T.B.; Formea, C.M.; Nicholson, W.T.; Rohrer Vitek, C.R. Education and Knowledge in Pharmacogenomics: Still a Challenge? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drelles, K.; Pilarski, R.; Manickam, K.; Shoben, A.B.; Toland, A.E. Impact of Previous Genetic Counseling and Objective Numeracy on Accurate Interpretation of a Pharmacogenetics Test Report. Public Health Genom. 2021, 24, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH Atlas.ti Web. Berlin, Germany. 2021. Available online: https://atlasti.com/cloud/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Chapdelaine, A.; Lamoureux-Lamarche, C.; Poder, T.G.; Vasiliadis, H.-M. Sociodemographic factors and beliefs about medicines in the uptake of pharmacogenomic testing in older adults. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddy, C.A.; Ward, H.M.; Angley, M.T.; McKinnon, R.A. Consumers’ views of pharmacogenetics-A qualitative study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2010, 6, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, P.; Joly, Y.; Avard, D.; Chitayat, D.C.; Smith, M.A.; Ross, C.J.D.; Carleton, B.C.; Hayden, M.R.; Koren, G. Communicating pharmacogenetic research results to breastfeeding mothers taking codeine: A pilot study of perceptions and benefits. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 88, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Daniel, J.; Lucas, J.; Deverka, P.; Ermentrout, D.; Silvey, G.; Lobach, D.F.; Haga, S.B. Factors influencing uptake of pharmacogenetic testing in a diverse patient population. Public Health Genom. 2010, 13, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haga, S.B.; O’Daniel, J.M.; Tindall, G.M.; Lipkus, I.R.; Agans, R. Public attitudes toward ancillary information revealed by pharmacogenetic testing under limited information conditions. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, J.L.; Robinson, R.; Starks, H.; Burke, W.; Dillard, D.A. Risk, reward, and the double-edged sword: Perspectives on pharmacogenetic research and clinical testing among Alaska Native people. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 2220–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Defrank, J.T.; Chiu, W.K.; Ibrahim, J.G.; Walko, C.M.; Rubin, P.; Olajide, O.A.; Moore, S.G.; Raab, R.E.; Carrizosa, D.R.; et al. Patients’ understanding of how genotype variation affects benefits of tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer. Public Health Genom. 2014, 17, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.Y.W.; Chua, B.Y.; Subramaniam, M.; Suen, E.L.K.; Lee, J. Clinicians’ perceptions of pharmacogenomics use in psychiatry. Pharmacogenomics 2017, 18, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinidad, S.B.; Coffin, T.B.; Fullerton, S.M.; Ralston, J.; Jarvik, G.P.; Larson, E.B. “Getting off the Bus Closer to Your Destination”: Patients’ Views about Pharmacogenetic Testing. Perm. J. 2015, 19, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haga, S.B.; Mills, R.; Moaddeb, J.; Allen Lapointe, N.; Cho, A.; Ginsburg, G.S. Patient experiences with pharmacogenetic testing in a primary care setting. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 17, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, A.N.A.; Bergsma, E.L.; Bergman, J.E.H.; De Walle, H.E.K.; Kerstjens-Frederikse, W.S.; Bijker, B.J.; Hak, E.; Wilffert, B. Knowledge and attitude regarding pharmacogenetics among formerly pregnant women in the Netherlands and their interest in pharmacogenetic research. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.L.; Hohmeier, K.C.; Smith, C.T. Pharmacogenomics testing in a community pharmacy: Patient perceptions and willingness-to-pay. Pharmacogenomics 2017, 18, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M.; McKillip, R.P.; Borden, B.A.; Klammer, C.E.; Ratain, M.J.; O’Donnell, P.H. Assessment of patient perceptions of genomic testing to inform pharmacogenomic implementation. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 2017, 27, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, A.A.; Hulick, P.J.; Wake, D.T.; Wang, C.; Sereika, A.W.; Yu, K.D.; Glaser, N.S.; Dunnenberger, H.M. Patient perspectives following pharmacogenomics results disclosure in an integrated health system. Pharmacogenomics 2018, 19, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, R.; Ensinger, M.; Callanan, N.; Haga, S.B. Development and Initial Assessment of a Patient Education Video about Pharmacogenetics. J. Pers. Med. 2017, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, J.E.; Rohrer Vitek, C.R.; Bell, E.J.; McGree, M.E.; Jacobson, D.J.; St Sauver, J.L.; Caraballo, P.J.; Griffin, J.M.; Roger, V.L.; Bielinski, S.J. Participant-perceived understanding and perspectives on pharmacogenomics: The Mayo Clinic RIGHT protocol (Right Drug, Right Dose, Right Time). Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.K.; Kulchak Rahm, A.; Gionfriddo, M.R.; Williams, J.L.; Fan, A.L.; Pulk, R.A.; Wright, E.A.; Williams, M.S. Developing Pharmacogenomic Reports: Insights from Patients and Clinicians. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2018, 11, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H.; Kang, H.Y.; Suh, H.S.; Lee, S.; Oh, E.S.; Jeong, H. Awareness and attitude of the public toward personalized medicine in Korea. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.; Haga, S.B. Qualitative user evaluation of a revised pharmacogenetic educational toolkit. Pharmgenomics. Pers. Med. 2018, 11, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.M.; Tran, J.N.; Tsunoda, S.M.; Young, G.K.; Lee, Y.M.; Anderson, H.D.; Page, R.L.; Hirsch, J.D.; Aquilante, C.L. Stakeholder perspectives of the clinical utility of pharmacogenomic testing in solid organ transplantation. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, L.G.; Bell, G.C.; Abernathy, P.M.; Ruch, K.; Denslow, S. Implementing pharmacogenetic testing in rural primary care practices: A pilot feasibility study. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigon, M.P.; Blackburn, M.È.; Dubois-Bouchard, C.; Gagnon, A.L.; Tardif, S.; Tremblay, K. Pharmacogenetic testing in primary care practice: Opinions of physicians, pharmacists and patients. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, S.B.; Liu, Y. Patient characteristics, experiences and perceived value of pharmacogenetic testing from a single testing laboratory. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.L.; So, D.; Bae, J.H.; Chavez, I.; Jeong, M.H.; Kim, S.W.; Madan, M.; Graham, J.; O’Cochlain, F.; Pauley, N.; et al. International survey of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and their attitudes toward pharmacogenetic testing. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2019, 29, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, T.M.; Lipschultz, E.; Danahey, K.; Schierer, E.; Ratain, M.J.; O’Donnell, P.H. Assessment of Patient Knowledge and Perceptions of Pharmacogenomics Before and After Using a Mock Results Patient Web Portal. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 13, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, L.; Shuman, C.; Cohn, I.; Kaiser, A.; Chitayat, D.; Wasim, S.; Hazell, A. Perplexed by PGx? Exploring the impact of pharmacogenomic results on medical management, disclosures and patient behavior. Pharmacogenomics 2019, 20, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiedu, G.B.; Finney Rutten, L.J.; Agunwamba, A.; Bielinski, S.J.; St Sauver, J.L.; Olson, J.E.; Rohrer Vitek, C.R. An assessment of patient perspectives on pharmacogenomics educational materials. Pharmacogenomics 2020, 21, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Broughton, S.; Aponte-Soto, L.; Watson, K.; Da Goia Pinto, C.; Empey, P.; Reis, S.; Winn, R.; Massart, M. Participatory genomic testing can effectively disseminate cardiovascular pharmacogenomics concepts within federally qualified health centers: A feasibility study. Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanting, P.; Drenth, E.; Boven, L.; van Hoek, A.; Hijlkema, A.; Poot, E.; van der Vries, G.; Schoevers, R.; Horwitz, E.; Gans, R.; et al. Practical Barriers and Facilitators Experienced by Patients, Pharmacists and Physicians to the Implementation of Pharmacogenomic Screening in Dutch Outpatient Hospital Care—An Explorative Pilot Study. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liko, I.; Lai, E.; Griffin, R.J.; Aquilante, C.L.; Lee, Y.M. Patients’ Perspectives on Psychiatric Pharmacogenetic Testing. Pharmacopsychiatry 2020, 53, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Png, W.Y.; Wong, X.Y.; Kwan, Y.H.; Lin, Y.Y.; Tan, D.S.Y. Perspective on CYP2C19 genotyping test among patients with acute coronary syndrome—A qualitative study. Future Cardiol. 2020, 16, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigter, T.; Jansen, M.E.; de Groot, J.M.; Janssen, S.W.J.; Rodenburg, W.; Cornel, M.C. Implementation of Pharmacogenetics in Primary Care: A Multi-Stakeholder Perspective. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidlen, T.; Sturm, A.C.; Scheinfeldt, L.B. Pharmacogenomic (PGx) Counseling: Exploring Participant Questions about PGx Test Results. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.M.; Lipschultz, E.; Schierer, E.; Danahey, K.; Ratain, M.J.; O’Donnell, P.H. Patient insights on features of an effective pharmacogenomics patient portal. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2020, 30, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, D.; Worley, M.; Porter, B.L. Patient perceptions of pharmacogenomic testing in the community pharmacy setting. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meagher, K.M.; Curtis, S.H.; Borucki, S.; Beck, A.; Srinivasan, T.; Cheema, A.; Sharp, R.R. Communicating unexpected pharmacogenomic results to biobank contributors: A focus group study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stancil, S.L.; Berrios, C.; Abdel-Rahman, S. Adolescent perceptions of pharmacogenetic testing. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zierhut, H.A.; Campbell, C.A.; Mitchell, A.G.; Lemke, A.A.; Mills, R.; Bishop, J.R. Collaborative Counseling Considerations for Pharmacogenomic Tests. Pharmacotherapy 2017, 37, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunnenberger, H.M.; Crews, K.R.; Hoffman, J.M.; Caudle, K.E.; Broeckel, U.; Howard, S.C.; Hunkler, R.J.; Klein, T.E.; Evans, W.E.; Relling, M.V. Preemptive clinical pharmacogenetics implementation: Current programs in five us medical centers. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015, 55, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.R. Pharmacists as facilitators of pharmacogenomic guidance for antidepressant drug selection and dosing. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1206–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastergiou, J.; Quilty, L.C.; Li, W.; Thiruchselvam, T.; Jain, E.; Gove, P.; Mandlsohn, L.; van den Bemt, B.; Pojskic, N. Pharmacogenomics guided versus standard antidepressant treatment in a community pharmacy setting: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.T.; Gregornik, D.; Kennedy, M.J. Advocacy and Research Committees The Role of the Pediatric Pharmacist in Precision Medicine and Clinical Pharmacogenomics for Children. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 23, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, L.A.; Kelly, S.E. The Genetic Knowledge Index: Developing a standard measure of genetic knowledge. Genet. Test. 1999, 3, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erby, L.H.; Roter, D.; Larson, S.; Cho, J. The rapid estimate of adult literacy in genetics (REAL-G): A means to assess literacy deficits in the context of genetics. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2008, 146A, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald-Butt, S.M.; Bodine, A.; Fry, K.M.; Ash, J.; Zaidi, A.N.; Garg, V.; Gerhardt, C.A.; McBride, K.L. Measuring genetic knowledge: A brief survey instrument for adolescents and adults. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, M.M.; Roche, M.I.; Brewer, N.T.; Berg, J.S.; Khan, C.M.; Leos, C.; Moore, E.; Brown, M.; Rini, C. Development and Validation of a Genomic Knowledge Scale to Advance Informed Decision Making Research in Genomic Sequencing. MDM Policy Pract. 2017, 2, 2381468317692582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wake, D.T.; Bell, G.C.; Gregornik, D.B.; Ho, T.T.; Dunnenberger, H.M. Synthesis of major pharmacogenomics pretest counseling themes: A multisite comparison. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).