Abstract

Patient-centered care is essential in high-quality health care, as it leads to beneficial outcomes for patients. The objective of this review is to systematize indicators for the care of patients with cardiometabolic diseases based on patient-centered care, extending from the stages of diagnostic evaluation and care planning to intervention. An integrative literature review was conducted by searching seven scientific databases, and a narrative analysis was performed. A total of 15 articles were included, and indicators related to diagnosis and care planning/intervention were extracted. In the planning of care centered on the person with cardiometabolic diseases, the individuality, dynamics of the processes, flexibility and the participation of all stakeholders should be taken into account. The needs of the person must be addressed through the identification of problems; establishment of individual goals; shared decision making; information and education; systematic feedback; case management; meeting the patient’s preferences and satisfaction with care; engagement of the family; and therapeutic management. The indicators for intervention planning extracted were behavioral interventions, therapeutic management programs, lifestyle promotion, shared decision making, education patient and information, interventions with the use of technology, promotion of self-management, program using technology, therapeutic relationship, therapeutic adherence programs and specialized intervention.

1. Introduction

Patient-centered care (PCC) is defined as care that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families to ensure that the care needs, values, and preferences of patients are satisfied [1]. PCC is characterized by empathy, respect, engagement, relationships, communication, shared decision making, holistic approaches, individualized focus and coordinated care [2]. From this perspective, the relationship between the patient and the caregiver is strengthened and is characterized by information sharing, empathy, and empowerment. In the partnerships established, the team’s sensitivity to the patient’s needs and their engagement in care stand out. In health promotion, the following dimensions are essential: case management and patient empowerment [1].

PCC is fundamental in high-quality health care and leads to beneficial outcomes for the patient, such as knowledge about their health, better skills to manage self-care behaviors, increased satisfaction, medication adherence, improved quality of life, and reduced admissions, readmissions and length of hospital stay. Regarding family members, PCC reduces the intensity of stress, anxiety, and depression, increases satisfaction, and improves relationships with health professionals. It also has beneficial effects on the health system, as services with a good cost–benefit ratio are provided [1,3].

For care to be centered on the patient, it is essential for decision making to be shared. In this care model, health communication is central to supporting patient engagement. Shared decision making has evolved greatly in recent years in Europe and North America. It reflects attitudes, beliefs and practices that should be explicit in PCC and that differ among different regions of the world and, on a smaller scale, among the different regions of a country [4].

One of the greatest challenges of the century is to optimize the health and quality of life of the population. The unavoidable reality of the high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases in the adult population and the aging of the population is a problem. Approximately 70% of elderly individuals have two or more chronic diseases, typically including a cardiovascular disease and a metabolic disease, which makes decision making difficult for health professionals and patients. A patient-centered approach and shared decision making can help ensure that the benefits of care decisions outweigh the harms of multiple comorbidities [5].

Cardiometabolic diseases (CMDs) are one of the main causes of comorbidities and death worldwide, both in developed countries and in emerging and underdeveloped economies. It is estimated that approximately 25% of the global adult population suffers from CMDs. Considered by the World Health Organization as the epidemic of the 21st century, CMDs encompass, among other conditions, obesity, diabetes and hypertension, which are considered risk factors for the development of cardiovascular diseases, such as acute myocardial infarction and stroke and peripheral arterial disease [6].

The risk factors for the development of CMDs are diverse but interrelated, such as hypertension, elevated fasting glucose, obesity and elevated triglycerides; understanding these contributes significantly to the development of clinical and/or treatment strategies [7]. However, there are some risk factors that cannot be changed, i.e., unmodifiable, such as older age (increasing age increases risks), genetic predisposition and sex (more frequent in men than in women until the age of menopause). However, in the case of most CMDs, the most common factors are almost always linked to lifestyle and therefore are modifiable, for example, diet, sedentary lifestyle, smoking and alcohol consumption, on which we can act on a day-to-day basis by preventing or treating. The less active a person is and the more foods rich in carbohydrates, sugars, and sodium they consume, such as fast food, cookies and/or sweets, the greater the chance of developing CMDs [6].

To reduce the chances of developing CMDs across the years, it is very important to implement lifestyle changes, such as prioritizing healthy eating and reducing the consumption of simple carbohydrates, sugars, and sodium; exercising at least 150 min per week; controlling alcohol intake; reducing or avoiding smoking; adopting measures that reduce stress (e.g., reading, sports and meditation); and having nights of restful sleep [6].

In this sense, it is essential that health professionals carry out a diagnostic assessment, develop an adequate care plan that is adapted to the lifestyle and environment in which they are inserted, and implement person-centered care. However, the scientific literature is sparse and has little consensus on diagnostic assessment strategies, care planning and interventions centered on people with patients with CMDs.

This integrative literature review aims to identify and systematize indicators for the care of patients with CMDs based on PCC, extending from the stages of diagnostic evaluation and care planning to intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this review was registered and published in PROSPERO (CRD42021240880), including the unique characteristics of the methodological procedures, namely, the eligibility criteria and data synthesis strategies.

2.2. Study Design

The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [8,9]. Our methods followed the framework of Whittemore and Knafl [10].

The review was designed based on the following research questions:

- How can the diagnostic evaluation of patients with cardiovascular and metabolic disease be performed, either through assessment instruments or other types of evaluation?

- What are the care planning strategies focused on patients with cardiovascular and metabolic disease developed with the objective of promoting health and preventing and/or reducing complications related to the aforementioned diagnoses?

- What intervention strategies aim to implement care processes focused on patients with cardiovascular and metabolic disease?

2.3. Search Strategy

To conduct the review, a broad literature search was conducted in the following databases: EBSCOhost Research Platform; CINAHL® Plus with Full Text; Nursing and Allied Health Collection; Cochrane Plus Collection, including Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE); MedicLatina; MEDLINE®, including International Nursing Index; PubMed via MEDLINE; EMBASE; Scopus; CINAHL; Web of Science; The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane); and the Virtual Health Library (VHL).

The search strategy was adjusted to each database and was limited to finding the most recent evidence from the last 10 years, dating from 2011 to 2021, including publications in English, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian.

2.4. Search Terms and Boolean Operators

The search involved the combination of four basic concepts in line with the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms; the search phrase was as follows: ((metabolic disease) OR (cardiovascular disease)) AND ((patient-centered care) OR (patient care planning)).

First, an exploratory study was conducted without limitations. However, given the large number of results, the search was limited to the title, abstract and/or keywords in the different databases.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5.1. Selection of Studies

The studies were selected in different phases. Duplicates were removed from the different search engines. Two reviewers independently analyzed the eligibility of studies to reduce bias and did so by reading the title and abstract. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria of the review were excluded. A third reviewer was consulted when disagreements or questions emerged. Last, the full text of the articles was evaluated following the same methodology.

2.5.2. Data Extraction

The reviewers who selected the studies also extracted the data independently. The third reviewer helped in cases of questions or disagreements.

A descriptive evaluation of each study was performed using an instrument designed for data extraction, taking into account the defined research questions.

2.5.3. Quality Appraisal

In the evaluation of quantitative, qualitative or mixed studies, it was decided to use the instruments of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), Adelaide, Australia (2020). These instruments rigorously evaluate the essential criteria of primary studies. The critical evaluation instruments were applied by two independent reviewers, with recourse to the third reviewer for consensus in case of disagreement. The result of the critical evaluation of the studies was not defined as an inclusion/exclusion criterion. All studies selected up to this stage were included.

2.5.4. Strategy for Data Synthesis

This review includes articles with different study designs. We chose to perform a structured narrative analysis of the findings to answer the research questions [10].

3. Results

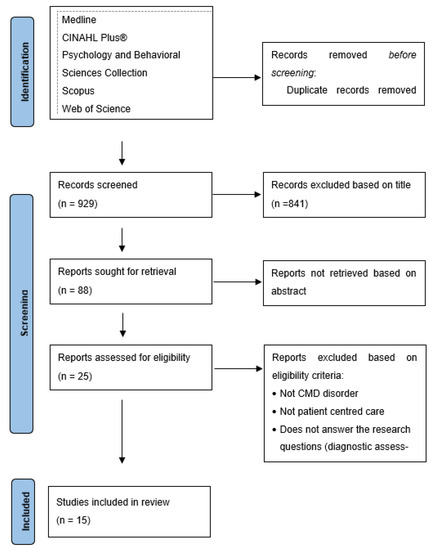

The search generated 946 results accepted for reading of the title. After that, 17 were removed because they were duplicates, and 841 were removed because the title did not fit the topic. The abstracts of the 88 selected articles were read, and the full text of 25 articles was analyzed. After reading the full text and applying the inclusion criteria, 10 articles were eliminated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Melbourne, Australia. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [9].

Table 1 shows the results of the studies.

Table 1.

Study results.

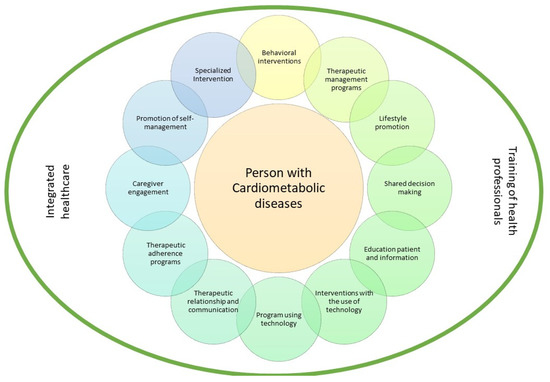

A content analysis was performed based on the extracted indicators and a patient-centered intervention model was built (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient-centered intervention model.

The intervention indicators extracted from the studies were: Behavioral interventions [15,21,24,25]; Therapeutic management programs [17,23,24]; Lifestyle promotion [11,13,14,24]; Shared decision making [12,14,16,18]; Education patient and information [15,21,22,24]; Interventions with the use of technology [11,17,25]; Program using technology [11,17,18,24,25]; Therapeutic relationship and communication [13,25]; Therapeutic adherence programs [16,21,23,25]; Caregiver engagement [12,22]; Promotion of self-management [15,21,25]; and Specialized intervention [18,22].

4. Discussion

This review integrates studies that allow for performing a narrative analysis of process, outcome and improvement indicators resulting from diagnostic evaluations and care planning and/or interventions in patients with CMDs.

4.1. Diagnostic Evaluation

Person-centered care models reinforce the satisfaction of the person’s needs. Regarding diagnostic evaluations, we found several instruments that are conducive to this care model. Most of the studies found based the diagnostic evaluation on person-centered data collection instruments, such as semi-structured interviews with different care stakeholders, including patients, practitioners and/or family members [12,15,21]. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (2013) published new guidelines to assess the risk of cardiovascular disease; the guidelines are centered on the evaluation of risk scores, providing a prediction of cardiovascular risk in order to identify the main risk factors and risk markers in primary and secondary prevention [16,26]. In the study by Dhukaram, Baber and De Stefanis (2012) [17], the evaluation was performed based on a focus group to understand the concerns and perceptions of patients. In a study conducted in Taiwan, the diagnostic evaluation was performed based on data collected from the National Health Insurance Research Database [20]. In the study by Duda et al. (2013) [25], patient evaluations were performed by a doctor, following the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology for the medical diagnosis of heart failure (Maggioni et al., 2013) [27]. The American Heart Association Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Health Summit reinforces the importance of evaluating seven health behaviors and cardiometabolic risk factors [28].

Based on the analysis of the various studies, we highlight the importance of conducting an individualized cardiometabolic risk assessment in order to implement primary and secondary prevention strategies adapted to individual risk.

4.2. Care Planning and Intervention

The planning of care and the respective intervention found in the selected studies revealed a diversity of data that mostly converge on care centered on patients and their individual conditions. The study conducted by Iturralde et al. (2019) [11] designed an intervention to develop knowledge and skills in patients who were systematically unable to achieve therapeutic management goals and control cardiovascular risk factors. The e-health intervention for patient training and self-management was based on the use of voice or video calls to reinforce self-management behaviors and skills. The authors found improvements in the care process and patient engagement. However, there were no evident improvements in the control of cardiovascular risk factors. In the study by O’Leary et al. (2016) [12], the intervention performed focused on cardiac telemetry monitoring. The use of technology had great relevance in the care process was the improvement of communication between patients and health professionals. However, there were no significant differences in decision making, information sharing or patient satisfaction. The indicator related to communication was also found in the study by Kim and Rich (2016) [18]. According to these authors, discussing the management plan with the patient is important, and providing a written summary can facilitate communication among stakeholders. In the study by McBride et al. (2014) [22] on the management of patients with heart failure, specialist nurses used patient-held alert cards to improve communication and care continuity for these patients. The involvement of specialist nurses facilitates care continuity for patients with heart failure at different levels of care in the health system, as well as safety and efficacy. The alert cards enabled both patients and caregivers to take a more active role in PCC.

Reducing cardiovascular risk is a cross-cutting goal in Western society. Lenz and Monaghan (2011) [13] demonstrated this concern ten years ago. They conducted a study that implemented a program to reduce cardiovascular risk based on an intervention conducted in a community pharmacy setting. They utilized various tools, such as a lifestyle adherence diary, nutrition diary, pedometer, home blood pressure monitor, monthly news bulletin, monthly support group meeting, blog site and educational materials. They observed improved compliance with the guidelines on cholesterol, increased consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, improved communication between patient and health professionals, and increased awareness and accountability for health. Very positive indicators, such as decreased cardiovascular risk, decreased blood pressure levels, decreased blood glucose levels, and decreased weight, were obtained in that study. At the end of the pilot program, 80% of participants consistently exercised at a level that met the guidelines (>150 min/week) for 3 months. In addition, all participants increased their combined consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, from an average of 0.9 to 4.5 servings per day. The average weight loss was greater than 12 lbs per person (more than 5% per person); the individual risk of cardiovascular disease improved on average by 34%; and for cardiac diseases only, the individual risk improved on average by 47% after 12 months. For more than half of the participants, communication with health professionals improved. The vast majority considered that the program helped them become more aware of their personal health needs and made them more responsible for actions related to lifestyle [13].

The guidelines issued in 2013 by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association described in the study by Montori, Brito and Ting (2014) [16] showed improvements in the implementation of PCC and shared decision making between patients and health professionals. Additionally, Sassen, Kok, Schepers and Vanhees (2014) [19] conducted a study to test the efficacy of a web-based intervention for the clinical practice of PCC; however, there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups. The study by Kornelius et al. (2015) [20] revealed that a diabetes shared care program, an integrated care model designed to increase the quality of care for patients with diabetes, had a positive impact. In addition, the outcomes pointed to a lower risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. Lifestyle improvement recommendations, such as cholesterol reduction, smoking cessation, weight loss, and blood pressure control, are essential in the control of CMDs [14]. The cited study constructed an expert system that learned knowledge on lifestyle and associated cardiometabolic risks from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study data using k-nearest neighbor prediction models. The system collects and analyzes information that improves decision making and patient commitment to adopt a healthy lifestyle.

PCC is associated with less uncertainty in illness than is usual care. Dudas et al. (2013) [25] report that the results of their study suggest that compared with hospitalization-centered care, PCC for patients hospitalized for heart failure seems to have a positive effect by reducing self-reported uncertainty regarding the disease. When the caregivers and patients worked together as partners in a structured PCC plan, many of the issues and uncertainties with which the patients struggled were clarified and resolved during hospitalization. Many patients reported that in the current health care system, they often have to navigate through a fragmented care system where the perspective of the health professional prevails instead of receiving care designed to focus on individual needs, preferences and values. Additionally, PCC reinforced the patients’ perception of the efficacy of treatment. In the multicenter study conducted by Dhukaram, Baber and De Stefanis (2012) [17] on understanding the concerns and perceptions of patients regarding pervasive healthcare systems, patients provided recommendations for system improvements and, as indicators, improvements in health status monitoring as a facilitator of contact between patient and doctor and assurances of confidentiality and privacy with respect to data security.

The interventions studied are highly heterogeneous and centered on recommendations for health promotion and prevention of cardiometabolic risk factors and using information and communication technologies (phone calls, telemedicine, e-health).

In general, the studies included in this integrative review show the following results: improvements in the care process, patient engagement [11], improvements in health status monitoring [17], improvements in communication between patient and health professionals [12,13,17,18,22,25], improvements in shared decision making between patients and health professionals [14,16], data improvements, respecting data privacy and confidentiality [17], care continuity [22], and improved compliance with guidelines and accountability for health [13,14]. These results corroborate previous studies related to patient- and family-centered care with regard to improved knowledge, self-care management, medication adherence and patient satisfaction [3].

The clinical results found in the studies were a decrease in cardiovascular risk factors, such as decreased blood pressure levels, decreased blood glucose levels, decreased weight [13,14,20] and decreased mortality [20]. The evidence found seems to be in agreement with the results previously found by Park et al. (2018) [3] because by reducing the risk factors, there will be better symptom management and better self-care, with a consequent reduction in hospital admissions.

Interventions aimed at patients with cardiometabolic risk can be in-person or remote (e-health) and should be based on the principles of PCC to improve the safety and quality of care. In this sense, the approach to patients should be based on the therapeutic relationship, be holistic and individualized, in which there is empathy, respect, and patient involvement in decision-making, and communication should be clear and assertive. The studies found reported that PCC improved patient assessment, self-care, medication adherence, health and quality of life, and decreased cardiometabolic risk and mortality.

These results are in line with the findings of studies in which educational interventions aimed at lifestyles were carried out with the objective of reducing cardiometabolic risk in a more cost-effective way [29,30].

The main limitation of this study was the decision to conduct the search in electronic databases and portals in Portuguese, English, Italian and Spanish, which may have led to the non-inclusion of publications on the subject in other languages. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of the studies that limits the comparison of findings. However, it allows us to verify the complexity of evaluating patients with CMDs and the variety of interventions in this context.

5. Conclusions

We emphasize the importance of PCC models for patients with CMDs, highlighting the importance of performing a periodic evaluation of cardiometabolic risk with special emphasis on lifestyle assessment.

In intervention models focused on patients with cardiometabolic risk, an approach that encompasses behavioral interventions, therapeutic management programs, lifestyle promotion, shared decision making, education patient and information, interventions with the use of technology, promotion of self-management, program using technology, therapeutic relationship, therapeutic adherence programs and specialized intervention.

In care planning, some technological strategies can improve the care process and the outcomes, such as the use of e-health programs, telemedicine, follow-up through phone calls, the use of lifestyle diaries, and the use of information systems that support shared decision making.

In addition, PCC are related to improvements in communication, patient–practitioner relationships, shared decision making, medication adherence, engagement and responsibility for health, and self-care and care continuity. With regard to clinical outcomes, the PCC approach allows for improving health and quality of life by reducing cardiometabolic risk factors, thus translating into reduced mortality and a decreased need for hospitalization, and hence the associated costs.

6. Content Analysis

We find that based on the extraction of results as part of the literature review process, there are different interventions/strategies focused on patients with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases that have a significant therapeutic impact on the quality of the care process, with reductions in health complications related to the aforementioned diagnoses and health gains, thus contributing to the effective monitoring of cardiovascular risk and positive outcomes of people-centered care through coordination, collaboration and partnership.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and M.d.C.M.; methodology, L.S. and M.d.C.M.; validation, M.L.; formal analysis, L.S. and M.d.C.M.; investigation, M.L., C.F., L.G.P., L.S. and M.d.C.M.; resources, R.P., M.P., L.S. and M.d.C.M.; data curation, R.P., M.P., L.S. and M.d.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.d.C.M. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, M.L., C.F. and L.G.P.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FEDER. Programa Interreg VA España-Portugal (POCTEP), grant number 0499_4IE_PLUS_4_E.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Green, C.; Dunn, S.; Grace, S.L.; Khanlou, N.; Stewart, D.E. How do and could clinical guidelines support patient-centred care for women: Content analysis of guidelines. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eklund, J.H.; Holmström, I.K.; Kumlin, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Skoglund, K.; Höglander, J.; Meranius, M.S. Same same or different? A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lee, M.; Jeong, H.; Jeong, M.; Go, Y. Patient-and family-centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 87, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zisman-Ilani, Y.; Obeidat, R.; Fang, L.; Hsieh, S.; Berger, Z. Shared Decision Making and Patient-Centered Care in Israel, Jordan, and the United States: Exploratory and Comparative Survey Study of Physician Perceptions. JMIR Res. 2020, 4, e18223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.; McKinn, S.; Bonner, C.; Muscat, D.M.; Doust, J.; McCaffery, K. Tomada de decisão compartilhada sobre medicamentos para doenças cardiovasculares em pessoas idosas: Um estudo qualitativo de experiências de pacientes na prática geral. BMJ Aberto 2019, 9, e026342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eduard, M.-S.; Júlio, P.-F.; Alejandra, R.-F. Coocorrência de Fatores de Risco para Doenças Cardiometabólicas: Alimentação Não Saudável, Tabaco, Álcool, Estilo de Vida Sedentário e Aspetos Socioeconómicos. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2019, 113, 710–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Saúde, D.G. Avaliação Do Risco Cardiovascular SCORE: Norma n.° 005/2013, de 19/03/2013, Atualizada em 21/01/2015. Lisboa: DGS. 2015. Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/directrizes-da-dgs/normas-e-circulares-normativas/norma-n-0052013-de-19032013-jpg.aspx (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; McKenzie, J.E. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturralde, E.; Sterling, S.A.; Uratsu, C.S.; Mishra, P.; Ross, T.B.; Grant, R.W. Changing Results-Engage and Activate to Enhance Wellness: A Randomized Clinical Trial to Improve Cardiovascular Risk Management. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e014021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.J.; Killarney, A.; Hansen, L.O.; Jones, S.; Malladi, M.; Marks, K.; Shah, H.M. Effect of patient-centred bedside rounds on hospitalised patients’ decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, T.L.; Monaghan, M.S. Implementing lifestyle medicine with medication therapy management services to improve patient-centered health care. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2011, 51, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.-L.; Nick Street, W.; Robinson, J.G.; Crawford, M.A. Individualized patient-centered lifestyle recommendations: An expert system for communicating patient specific cardiovascular risk information and prioritizing lifestyle options. J. Biomed. Inform. 2012, 45, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filler, T.; Dunn, S.; Grace, S.L.; Straus, S.E.; Stewart, D.E.; Gagliardi, A.R. Multi-level strategies to tailor patient-centred care for women: Qualitative interviews with clinicians. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montori, V.M.; Brito, J.P.; Ting, H.H. Patient-centered and practical application of new high cholesterol guidelines to prevent cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2014, 311, 465–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhukaram, A.V.; Baber, C.; De Stefanis, P. Patient-centred cardio vascular disease management–end-user perceptions. J. Assist. Technol. 2012, 6, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Rich, M.W. Patient-Centred Care of Older Adults with Cardiovascular Disease and Multiple Chronic Conditions. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sassen, B.; Kok, G.; Schepers, J.; Vanhees, L. Supporting health care professionals to improve the processes of shared decision making and self-management in a web-based intervention: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kornelius, E.; Chiou, J.-Y.; Yang, Y.-S.; Lu, Y.-L.; Peng, C.-H.; Huang, C.-N. The Diabetes Shared Care Program and Risks of Cardiovascular Events in Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligthart, S.A.; van den Eerenbeemt, K.D.; Pols, J.; van Bussel, E.F.; Richard, E.; van Charante, E.P.M. Perspectives of older people engaging in nurse-led cardiovascular prevention programmes: A qualitative study in primary care in the Netherlands. British J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e41–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McBride, A.; Burey, L.; Megahed, M.; Feldman, C.; Deaton, C. The role of patient-held alert cards in promoting continuity of care for heart failure patients. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2014, 13, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, B.A.; Freels, J.P.; Furuno, J.P.; Mackay, J. Pharmacy-managed program for providing education and discharge instructions for patients with heart failure. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2014, 71, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Flaherty, G.; Cormican, S.; Jones, J.; Kerins, C.; Walsh, A.M.; Crowley, J. Translating guidelines to practice: Findings from a multidisciplinary preventive cardiology programme in the west of Ireland. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudas, K.; Olsson, L.E.; Wolf, A.; Swedberg, K.; Taft, C.; Schaufelberger, M.; Ekman, I. Uncertainty in illness among patients with chronic heart failure is less in person-centred care than in usual care. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 12, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E. Scores de risco cardiovascular: Utilidade e limitações. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2016, 35, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggioni, A.P.; Anker, S.D.; Dahlström, U.; Filippatos, G.; Ponikowski, P.; Zannad, F.; Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA). Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with he hart failure treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12 440 patients of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013, 15, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasson, C.; Eckel, R.; Alger, H.; Bozkurt, B.; Carson, A.; Daviglus, M.; Sanchez, E. American heart association diabetes and cardiometabolic health summit: Summary and recommendations. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stol, D.M.; Over, E.A.; Badenbroek, I.F.; Hollander, M.; Nielen, M.M.; Kraaijenhagen, R.A.; Schellevis, F.G.; de Wit, N.J. Cost-effectiveness of a stepwise cardiometabolic disease prevention program: Results of a randomized controlled trial in primary care. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucini, D.; Malacarne, M.; Gatzemeier, W.; Pagani, M. A simple home-based lifestyle intervention program to improve cardiac autonomic regulation in patients with increased cardiometabolic risk. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).