Sinus Tarsi Morphometry Is Correlated with Flatfoot Severity on Weight-Bearing CT

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection of the Patients

2.2. Radiographic Measurement on WB X-Rays

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- History of chronic or progressive neuromuscular disorders (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, stroke, Sequelae cerebral palsy, or muscular dystrophy) resulting in significant gait or foot deformities.

- (2)

- Previous foot or ankle surgeries (including internal fixation, arthrodesis, or implant placement) or the presence of unhealed fractures within the past one year.

- (3)

- Diagnosed inflammatory joint diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis) or systemic metabolic bone diseases (e.g., severe osteoporosis with a history of fractures, or osteomalacia).

- (4)

- Congenital foot deformities (e.g., congenital vertical talus or polydactyly/syndactyly with malformation) or other significant structural congenital abnormalities.

- (5)

- Regular use of custom orthotic insoles or arch supports for corrective purposes (e.g., plantar fasciitis or Charcot foot).

- (6)

- Prior systematic physical therapy or rehabilitation training targeting the foot and ankle (e.g., ankle sprain or achilles tendon rupture).

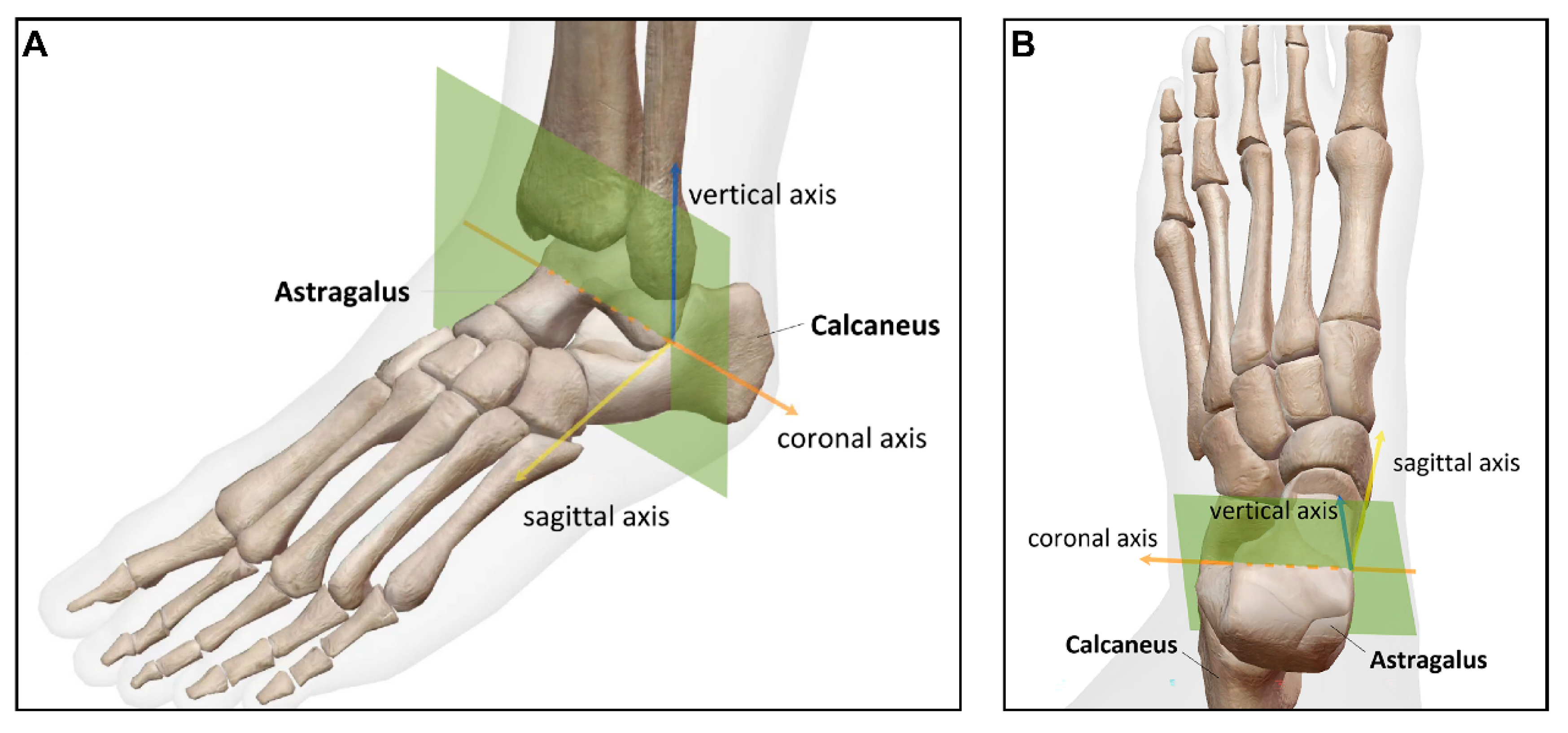

2.5. Morphometric Measurements of the Sinus Tarsi on WBCT

- (1)

- Sinus tarsi length (STL): the distance between the medial apex of the sinus tarsi canal (at the talar edge of the anterior subtalar articular facet) and the lateral endpoint of the sinus tarsi canal orifice on the calcaneus.

- (2)

- Sinus tarsi width (STW): the vertical distance between the superior and inferior borders of the sinus tarsi canal, measured along a line perpendicular to the talar surface of the tibiotalar joint, passing through the midpoint of that surface.

- (3)

- Angle between the long axis of the sinus tarsi and the horizontal line (ST-H angle): the angle formed by the line connecting the medial apex of the sinus tarsi canal (at the talar edge of the anterior subtalar articular facet) to the lateral endpoint of the sinus tarsi canal orifice on the calcaneus, and the horizontal line.

- (4)

- Sinus tarsi angle (ST angle): the angle formed by the lateral superior point and lateral inferior point of the sinus tarsi orifice, and the medial apex of the sinus tarsi canal (the talar edge of the anterior subtalar articular facet).

- (5)

- Tibia width: the distance between the lateral edge of the tibial plafond and the medial turning point of the tibia at the tibiotalar joint from an anterior–posterior view.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kerr, C.M.; Stebbins, J.; Theologis, T.; Zavatsky, A.B. Static postural differences between neutral and flat feet in children with and without symptoms. Clin. Biomech. 2015, 30, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi-Demneh, E.; Melvin, J.M.A.; Mickle, K. Prevalence of pathological flatfoot in school-age children. Foot 2018, 37, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, S.; Unluer, N.O.; Korkusuz, F. Morphological and mechanical properties of plantar fascia and intrinsic foot muscles in individuals with and without flat foot. J. Orthop. Surg. 2018, 26, 2309499018802482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascio, A.; Comisi, C.; Cinelli, V.; Pitocco, D.; Greco, T.; Maccauro, G.; Perisano, C. Radiological Assessment of Charcot Neuro-Osteoarthropathy in Diabetic Foot: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, W.; Alotaibi, S.; Shaheen, A.; Farouk, M.; Farrag, A. The combined effect of short foot exercises and orthosis in symptomatic flexible flatfoot: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Hwang, S.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.S.; Park, G.; Kim, H.; Choi, J.; Kim, S. Deep learning-based tool affects reproducibility of pes planus radiographic assessment. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, A.; Lintz, F.; Sadile, F. The role of arthroereisis of the subtalar joint for flatfoot in children and adults. EFORT Open Rev. 2017, 2, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghali, A.; Mhapankar, A.; Momtaz, D.; Driggs, B.; Thabet, A.M.; Abdelgawad, A. Arthroereisis: Treatment of Pes Planus. Cureus 2022, 14, e21003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.W.; Wang, Y.; Niu, W.; Zhang, M. Finite element analysis of subtalar joint arthroereisis on adult-acquired flexible flatfoot deformity using customised sinus tarsi implant. J. Orthop. Transl. 2021, 27, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, X.; He, S.; Zhou, X.; Yi, G.; Tang, X.; Li, B.; Wang, G.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Y. Association between subtalar articular surface typing and flat foot deformity: Which type is more likely to cause flat foot deformity. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, T.; Ma, Y. Anatomical Features of the Tarsal Sinus in Patients with Pes Planus: Implications for Clinical Management. Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e940687-1–e940687-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E.J.; Vanore, J.V.; Thomas, J.L.; Kravitz, S.R.; Mendelson, S.A.; Mendicino, R.W.; Silvani, S.H.; Gassen, S.C. Diagnosis and treatment of pediatric flatfoot. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2004, 43, 341–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J.Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, X. Mid-term Results of Subtalar Arthroereisis with Talar-Fit Implant in Pediatric Flexible Flatfoot and Identifying the Effects of Adjunctive Procedures and Risk Factors for Sinus Tarsi Pain. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 13, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.H.; Lee, C.C.; Tseng, T.H.; Wu, K.W.; Chang, J.F.; Wang, T.M. Endosinotarsal device exerts a better postoperative correction in Meary’s angle than exosinotarsal screw from a meta-analysis in pediatric flatfoot. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flury, A.; Hasler, J.; Beeler, S.; Imhoff, F.B.; Wirth, S.H.; Viehöfer, A. Talus morphology differs between flatfeet and controls, but its variety has no influence on extent of surgical deformity correction. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 142, 3103–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiffer, M.; Van Den Borre, I.; Segers, T.; Ashkani-Esfahani, S.; Guss, D.; De Cesar Netto, C.; DiGiovanni, C.W.; Victor, J.; Audenaert, E.; Burssens, A. Implementing automated 3D measurements to quantify reference values and side-to-side differences in the ankle syndesmosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cesar Netto, C.; Myerson, M.S.; Day, J.; Ellis, S.J.; Hintermann, B.; Johnson, J.E.; Sangeorzan, B.J.; Schon, L.C.; Thordarson, D.B.; Deland, J.T. Consensus for the Use of Weightbearing CT in the Assessment of Progressive Collapsing Foot Deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 2020, 41, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbdelMassih, A.; Hozaien, R.; Mishriky, F.; Michael, M.; AmanAllah, M.; Ali, N.; ElGamal, N.; Medhat, O.; Kamel, M.; Helmy, R.; et al. Meary angle for the prediction of mitral valve prolapse risk in non-syndromic patients with pes planus, a cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2022, 15, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinacore, D.R.; Gutekunst, D.J.; Hastings, M.K.; Strube, M.J.; Bohnert, K.L.; Prior, F.W.; Johnson, J.E. Neuropathic midfoot deformity: Associations with ankle and subtalar joint motion. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2013, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbachova, T.; Melenevsky, Y.V.; Latt, L.D.; Weaver, J.S.; Taljanovic, M.S. Imaging and Treatment of Posttraumatic Ankle and Hindfoot Osteoarthritis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Koh, D.T.S.; Tay, K.S.; Koo, K.O.T.; Singh, I.R. Lateral column osteotomy versus subtalar arthroereisis in the correction of Grade IIB adult acquired flatfoot deformity: A clinical and radiological follow-up at 24 months. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021, 27, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, K.C.; Greene, G.; Hallam, J.; Juliano, P.J.; Aynardi, M.C. Short- to Mid-Term Outcomes Following the Use of an Arthroereisis Implant as an Adjunct for Correction of Flexible, Acquired Flatfoot Deformity in Adults. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018, 12, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, C.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Z. Risk Factors of Subtalar Arthroereisis for Progressive Collapsing Foot Deformity: A Retrospective Analysis of 236 Cases. Orthop. Surg. 2025, 17, 2662–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, E.A.; Cook, J.J.; Basile, P. Identifying risk factors in subtalar arthroereisis explantation: A propensity-matched analysis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2011, 50, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boerum, D.H.; Sangeorzan, B.J. Biomechanics and pathophysiology of flat foot. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003, 8, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; Khatun, S. Pes Planus Foot among the First and Second Year Medical Students of a Medical College: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2021, 59, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, D.V.; Mejía Gómez, C.; Fernández Hernando, M.; Davis, M.A.; Pathria, M.N. Adult Acquired Flatfoot Deformity: Anatomy, Biomechanics, Staging, and Imaging Findings. RadioGraphics 2019, 39, 1437–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, E.A.; Williamson, E.R.; Burket, J.C.; Deland, J.T.; Ellis, S.J. Correlation of Talar Anatomy and Subtalar Joint Alignment on Weightbearing Computed Tomography with Radiographic Flatfoot Parameters. Foot Ankle Int. 2016, 37, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nourbakhsh, S.-A.; Sheikhhoseini, R.; Piri, H.; Soltani, F.; Ebrahimi, E. Spatiotemporal and kinematic gait changes in flexible flatfoot: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahririan, M.A.; Ramtin, S.; Taheri, P. Functional and radiographic comparison of subtalar arthroereisis and lateral calcaneal lengthening in the surgical treatment of flexible flatfoot in children. Int. Orthop. 2021, 45, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Patel, S.; Kaushal, A. Arthroereisis for Flatfoot: Current Status of Our Understanding. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2023, 10, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Min. | Max. | Mean ± SD | Median (Q1, Q3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Y) | 18 | 62 | 36.36 ± 10.59 | 36 (27, 43) |

| Height (m) | 1.53 | 1.88 | 1.69 ± 0.07 | 1.70 (1.63, 1.73) |

| Weight (kg) | 43.4 | 100.0 | 70.15 ± 11.10 | 70.5 (62.0, 78.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.06 | 34.60 | 24.49 ± 3.08 | 24.86 (22.05, 26.13) |

| Meary angle (°) | −4 | 33 | 8.03 ± 7.03 | 6 (3.75, 6) |

| Pitch angle (°) | 2 | 29 | 18.93 ± 6.66 | 20 (15, 24.25) |

| Control (n = 28) | Flatfoot (n = 42) | Statistics | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 24/4 | 23/19 | 5.96 | 0.015 a |

| Side (L/R) | 14/14 | 22/20 | 0.038 | 0.845 b |

| Age (Y) | 37.39 ± 8.77 | 35.67 ± 11.70 | 0.666 | 0.508 c |

| Height (m) | 1.71 ± 0.06 | 1.67 ± 0.08 | 2.405 | 0.019 d |

| Weight (kg) | 72.88 ± 11.59 | 68.32 ± 10.51 | 1.705 | 0.093 c |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.83 ± 3.52 | 24.27 ± 2.77 | 0.742 | 0.460 c |

| Meary angle (°) | 3 (1, 4) | 10 (7, 14) | −7.008 | <0.001 e |

| Pitch angle (°) | 24.5 (21, 27) | 16 (11.75, 19) | −5.879 | <0.001 e |

| Control (n = 28) | Flatfoot (n = 42) | Statistics | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STL (mm) | 23.09 ± 3.77 | 25.73 ± 3.50 | −3.000 | 0.004 a |

| STW (mm) | 8.71 ± 1.25 | 8.33 ± 2.07 | 0.937 | 0.352 b |

| ST-H angle (°) | 3.93 ± 4.15 | 2.89 ± 7.81 | 0.725 | 0.471 b |

| ST angle (°) | 17.83 (16.06, 23.24) | 13.20 (6.29, 18.40) | −3.501 | <0.001 c |

| Tibia width (mm) | 28.92 ± 3.59 | 28.87 ± 3.42 | 0.058 | 0.954 a |

| STL/tibia width | 0.81 ± 0.14 | 0.90 ± 0.15 | −2.680 | 0.009 a |

| STW/tibia width | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 0.958 | 0.341 a |

| Meary Angle as Dependent Variable. | |||||

| Unstandardized | Standardized | ||||

| B | SER | β | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 6.478 | 4.916 | 1.318 | 0.192 | |

| Gender * | −5.098 | 1.567 | −0.344 | −3.254 | 0.002 |

| ST angle (°) | −0.180 | 0.065 | −0.289 | −2.789 | 0.007 |

| STL/tibia width | 8.825 | 4.894 | 0.193 | 1.803 | 0.076 |

| Pitch Angle as Dependent Variable. | |||||

| Unstandardized | Standardized | ||||

| B | SER | β | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 28.270 | 4.446 | 6.358 | <0.001 | |

| ST angle (°) | 0.197 | 0.064 | 0.332 | 3.079 | 0.003 |

| STL/tibia width | −14.134 | 4.699 | −0.325 | −3.008 | 0.004 |

| Meary Angle as Dependent Variable. | |||||

| Sum of Square | df | Mean Square | F | p-value | |

| Regression | 1204.994 | 3 | 401.665 | 12.112 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 2188.778 | 66 | 33.163 | ||

| Total | 3393.771 | 69 | |||

| Pitch Angle as Dependent Variable. | |||||

| Sum of Square | df | Mean Square | F | p-value | |

| Regression | 835.110 | 2 | 417.555 | 12.559 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 2227.533 | 67 | 33.247 | ||

| Total | 3062.643 | 69 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, B.; Gao, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Li, W.; et al. Sinus Tarsi Morphometry Is Correlated with Flatfoot Severity on Weight-Bearing CT. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010162

Chen B, Gao X, Xu Y, Zhao T, Yang S, Liu Y, Jiang B, Zhou X, Chen X, Li W, et al. Sinus Tarsi Morphometry Is Correlated with Flatfoot Severity on Weight-Bearing CT. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Bingshu, Xing Gao, Ying Xu, Tianyuan Zhao, Siyao Yang, Yuan Liu, Bin Jiang, Xihan Zhou, Xiaoqiang Chen, Wencui Li, and et al. 2026. "Sinus Tarsi Morphometry Is Correlated with Flatfoot Severity on Weight-Bearing CT" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010162

APA StyleChen, B., Gao, X., Xu, Y., Zhao, T., Yang, S., Liu, Y., Jiang, B., Zhou, X., Chen, X., Li, W., & Guo, J. (2026). Sinus Tarsi Morphometry Is Correlated with Flatfoot Severity on Weight-Bearing CT. Diagnostics, 16(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010162