Challenges in the Classification of Cardiac Arrhythmias and Ischemia Using End-to-End Deep Learning and the Electrocardiogram: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

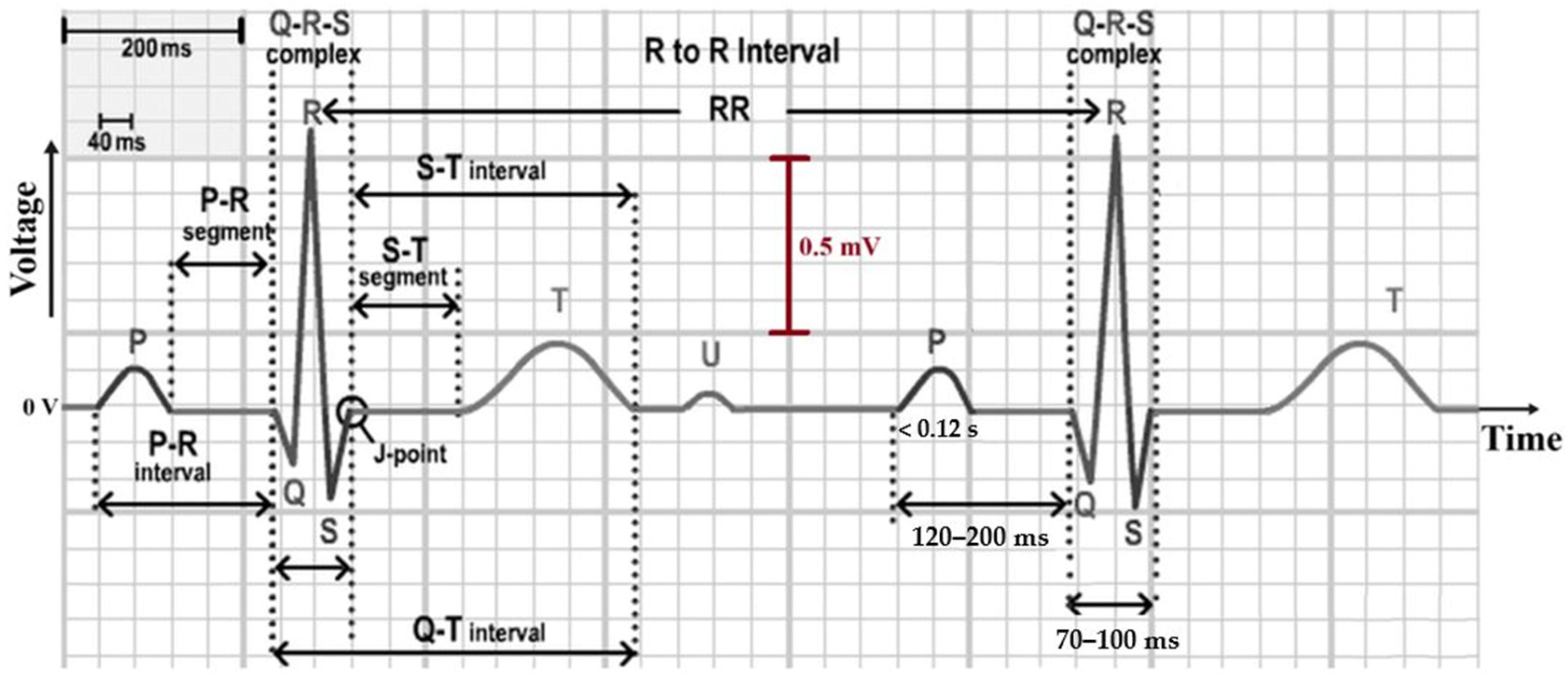

2.1. Electrical Control of Heart Pumping

2.2. The ECG and Its Leads

2.3. Arrhythmias: Causes and Classification

2.4. Ischemia: Causes and Consequences

2.5. Related Research

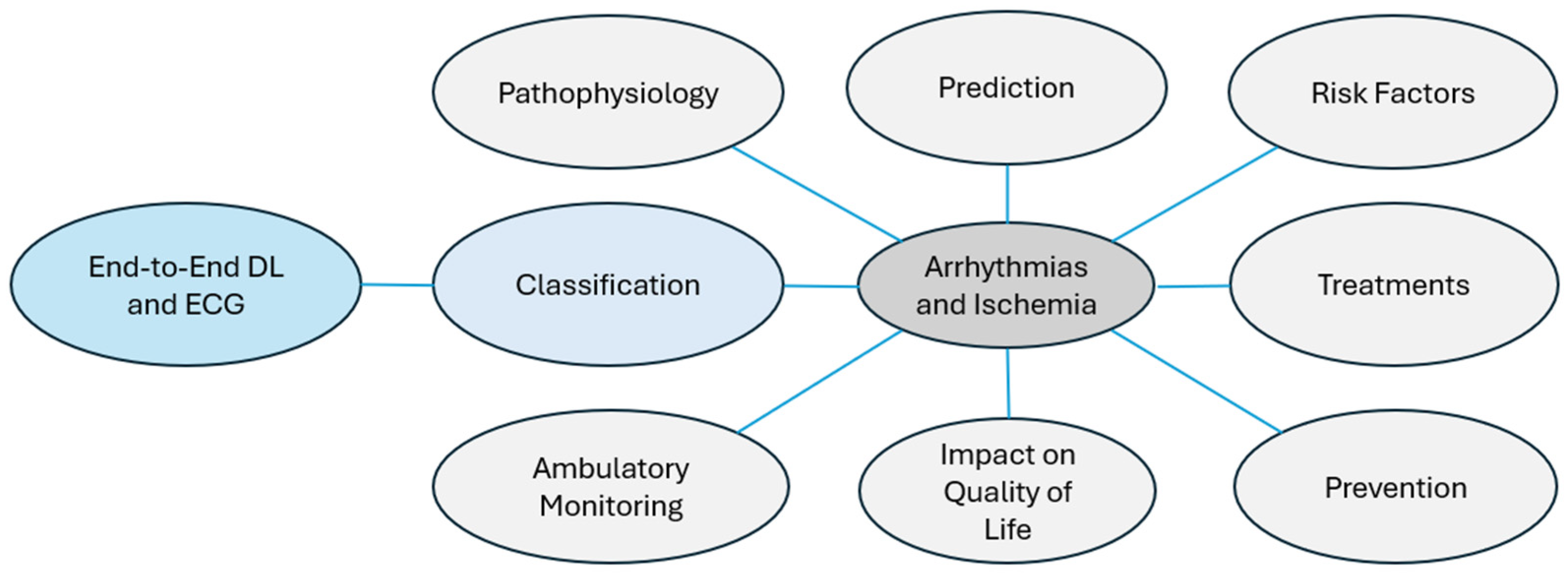

2.6. Aspects of Study

- Pathophysiology: The study of biological processes that alter heart rhythm or blood flow. For example, an imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems can lead to arrhythmias [37].

- Ambulatory Monitoring: Continuous tracking with portable devices to detect cardiac events in real time, such as Holter monitors integrated with IoT technology [40].

- Risk Factors: Identification of conditions that predispose individuals to cardiac diseases. For instance, obesity increases the risk of AF [41].

- Prevention: Measures aimed at minimizing cardiac arrhythmias or ischemia through modification of lifestyle or early intervention. For example, regular physical activity minimizes the risk of cardiac infarction [42].

- Treatments: Therapies designed to avoid or control arrhythmias and ischemia; for example, catheter ablation, which eliminates tachycardia [43].

- Impact on Quality of Life: Assessment of how heart disease affects emotional, physical, and social well-being. For example, patients recently diagnosed with ischemia may suffer from chronic anxiety [44].

- Prediction: Use of sophisticated algorithms to anticipate the occurrence of critical conditions. For example, ref. [45] proposed a fuzzy DL model to predict cardiac arrhythmias at their outset.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

- Planning: At this stage of the research protocol, investigators write draft a research protocol that contains the research questions and article search and selection procedure. This includes journal source selection, date selection, search strings, and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Execution: The protocol is utilized to select relevant articles addressing the formulated research questions and answering them.

- Results: Determination and presentation of statistics on the selected articles, including trends, quality, and distribution.

- Analysis: The researchers will be required to analyze the research questions formulated at the planning stage.

3.2. Planning

3.3. Execution

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Potential Articles

3.4.2. Publication Trends

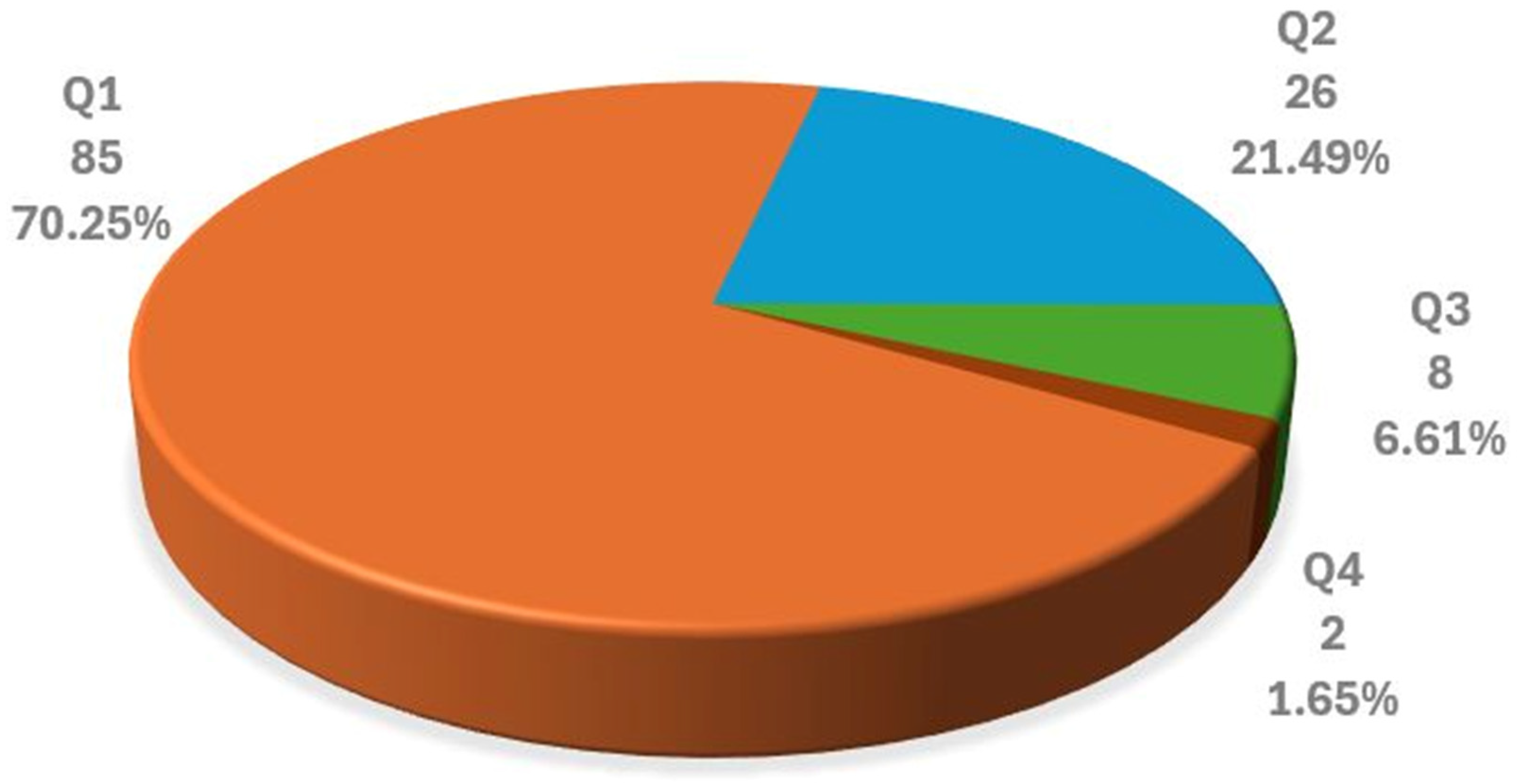

3.4.3. Selected Articles by Journal Quality Factor

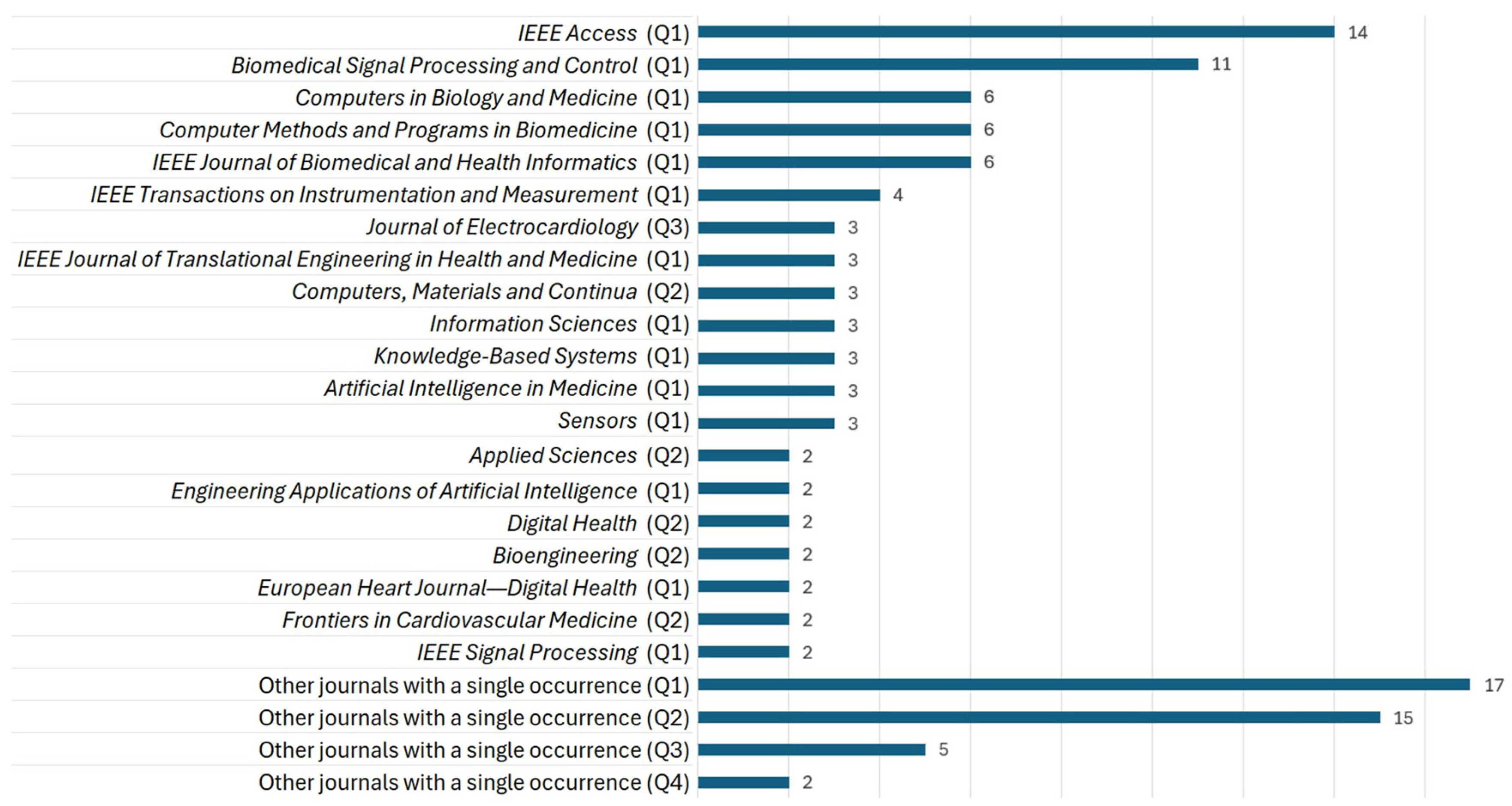

3.4.4. Selected Articles by Journal

3.5. Analysis

- RQ1: What preprocessing techniques are applied to ECG signals?

- RQ2: What end-to-end DL techniques are employed for feature extraction and CAIC from ECG?

- RQ3: Which databases are used to train and validate end-to-end DL algorithms?

- RQ4: What types of cardiac arrhythmias and ischemia are classified by the algorithms?

- RQ5: What metrics are used to evaluate the effectiveness of end-to-end DL algorithms?

- RQ6: Which techniques are used to explain the results of ECG-based CAIC using end-to-end DL?

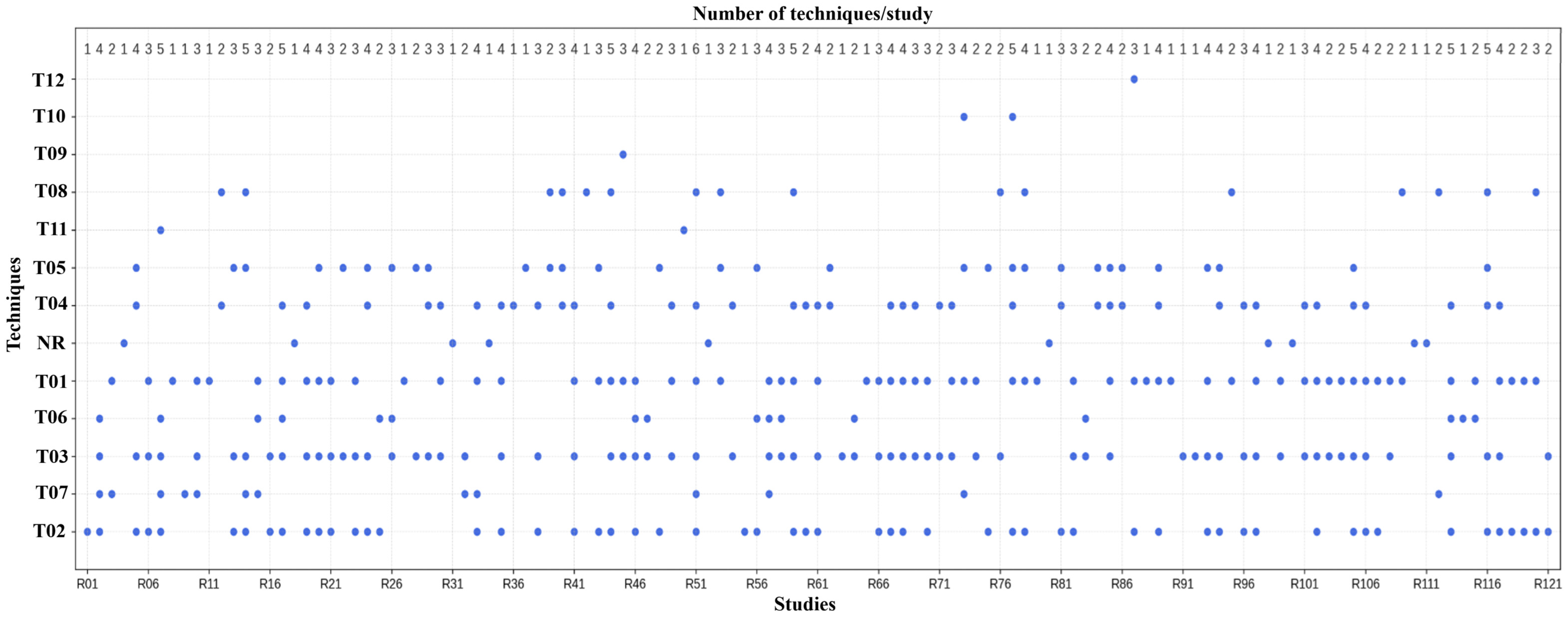

3.5.1. RQ1

- Techniques T01: Noise and Artifact RemovalThe methods used in this category are used for preprocessing the ECG signals in order to improve their quality. Wavelet-based methods rely on multi-resolution decomposition to separate waves and suppress noise components. Digital filters (Butterworth, band-pass, and notch) are used to suppress other frequencies, such as baseline wander and power-line noise. LOESS, moving average, and Non-Local Means (NLM) smoothing are statistical methods that use local signal similarity to suppress noise. To minimize amplitude changes, normalization methods are applied (sliding window). Furthermore, to discard residual noise, a thresholding strategy is employed (such as a hard threshold or wavelet threshold), discarding coefficients that went below a defined level. The purposes of artifact removal, baseline wander correction, high-frequency noise suppression, and residual noise removal represent complementary approaches to the common objective of enhancing ECG signal quality. In their studies, authors have labeled the techniques differently, but they are all aimed at solving the same noise and distortion problems in ECG preprocessing. In our corpus, 42 studies used some processing for noise or artifact removal.

- Techniques T02–05To ensure uniformity of the ECG signal amplitude, segmentation of the temporal structure on the recordings, and the harmonizing of sampling rates of the various datasets, preprocessing techniques T02–T04 were implemented. Normalization methods (T02) include Z-score scaling, Min–Max scaling, and unit variance adjustment to avoid varied amplitude ranges in the model. Windowing approaches (T03) segment signals into fixed-length segments of size 1.5–60 s using either a single window or multiple windows, with or without overlap, for local analysis and feature extraction. Resampling techniques (T04) modify the temporal resolution of a signal through downsampling or upsampling, aiming to create uniform sampling frequency data aligned in time and to process heterogeneous sources. These techniques enhance signal comparability and model compatibility, and were reported across a wide range of studies.The techniques under T05 deal with forcing identical signal duration and identical structure prior to the model input. The techniques used include zero-padding, cropping, trimming, replication, segmentation, and resampling. These methods were applied to obtain fixed-length signals of length 2.5 s to 2 min and sample length 4096 and 9000, respectively. Short recordings are padded or duplicated, while long recordings are cropped or split into overlapping recordings. These adaptations ensure that model architectures can leverage batch processing, allowing consistent feature extraction from various datasets. While the techniques vary across studies, they all attempt to bring the length and format of definitions to a more acceptable level to facilitate feature extraction and model training. According to Table S8, these approaches were analyzed in 25 papers.

- Techniques T06–T12In total, 41 techniques were identified in categories T06–T12, reported across 34 studies: 14 techniques in T06, 11 in T07, 11 in T08, 2 in T12, and 1 each in T09–T11.Techniques to balance classes (T06) are shown in Table 4; oversampling methods such as SMOTE and GAN, as well as downsampling and replication, are countermeasures to improve class balance. Techniques of data cleaning (T07) are used to remove redundant and missing values, noise, indistinct segments, duplicate values, and anomalous signal parts to add accuracy to the input. The techniques of augmentation (T08) apply operations such as cropping, jittering, warping, and noise insertion to diversify data and limit overfitting. Several less-often-reported categories serve specialized preprocessing roles. Overall, the objective of these techniques is to improve data quality, balance classes, and increase variability.

3.5.2. RQ2

3.5.3. RQ3

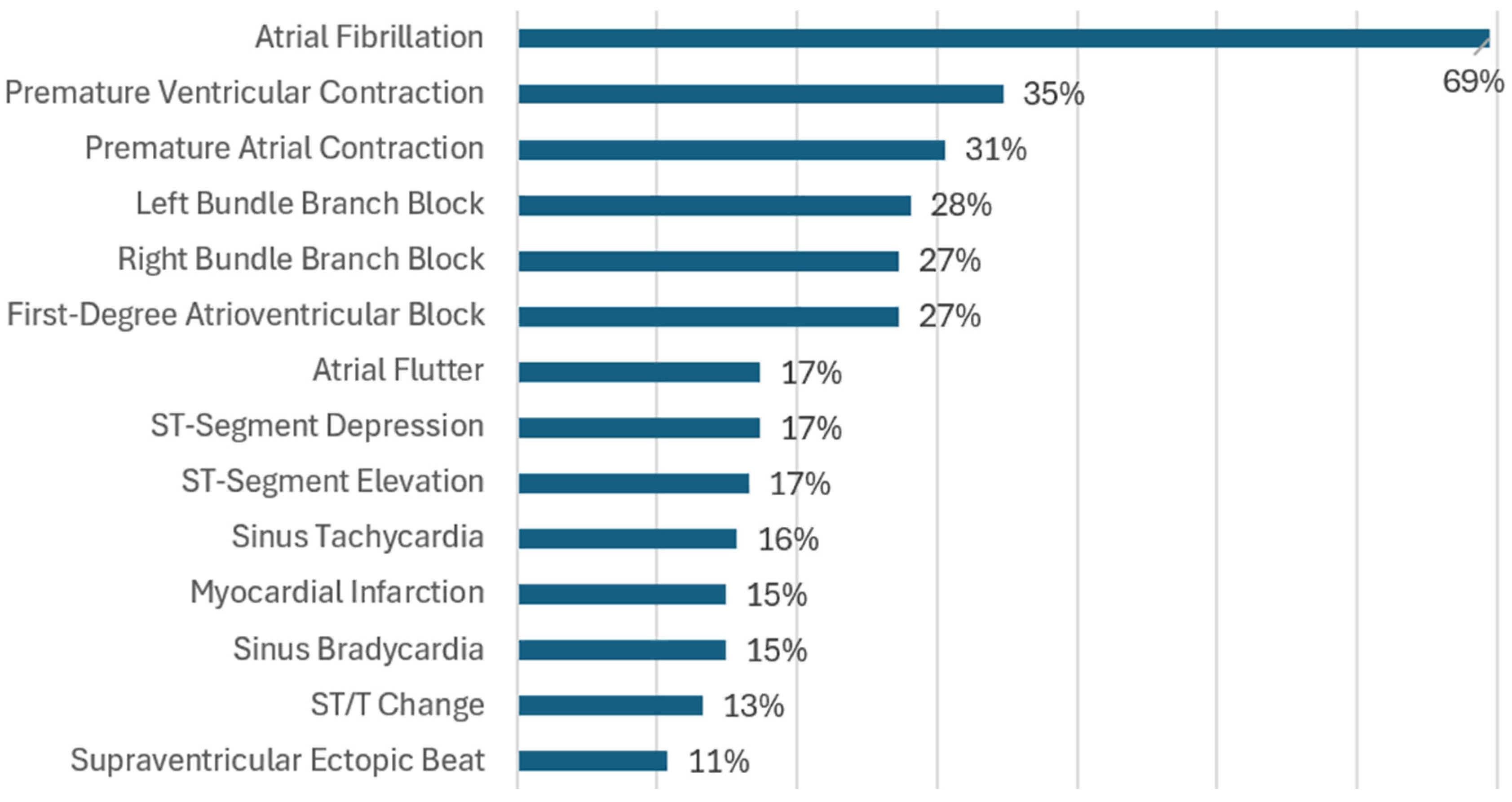

3.5.4. RQ4

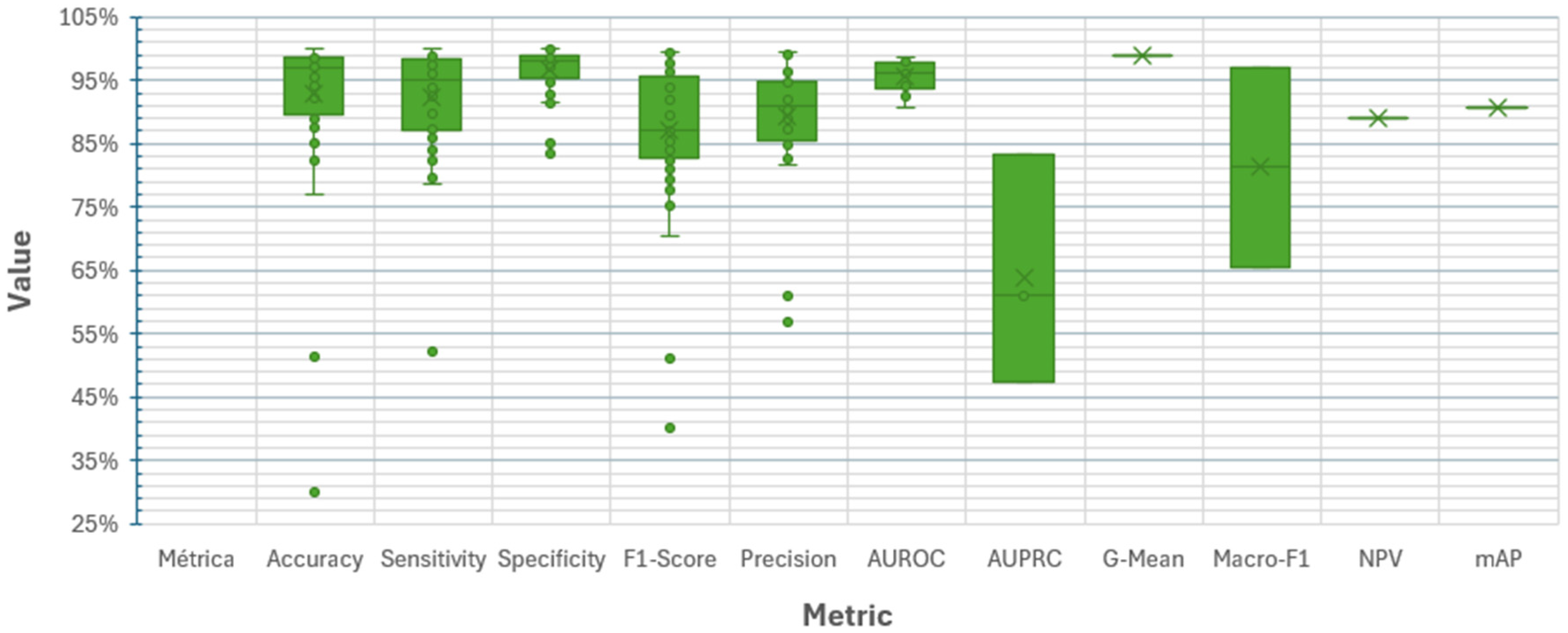

3.5.5. RQ5

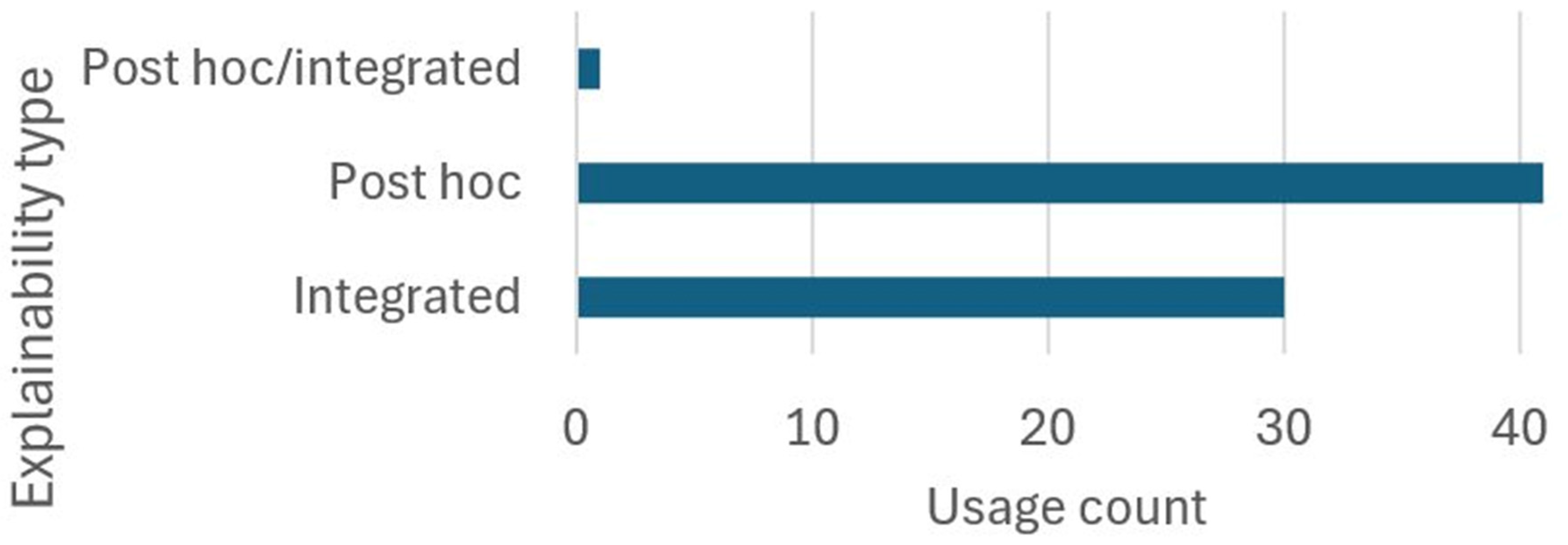

3.5.6. RQ6

4. Challenges of CAIC End-to-End DL and the ECG

4.1. Method

- Phase 1. Study Inventory: Relevant information on CAIC using end-to-end DL and ECG was collected from the specialized literature.

- Phase 2. Determination of the Purpose of each Analysis Aspect: The purpose of each analysis aspect was derived from its definition.

- Phase 3. Inventory of Challenges in the Analysis Aspects: A comprehensive review of the challenges reported in the collected studies was conducted for each analysis aspect.

- Phase 4. Identification of Unaddressed Challenges: Gaps not addressed in the literature were determined by comparing the inventory of challenges with the stated purposes of the analysis aspects.

- Phase 5. Discussion of Findings: The challenges identified in the previous phases were discussed, highlighting their implications for future research and the development of CAIC solutions. This phase is presented in Section 5.

4.2. Development

| ID | Difficulty | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| D16 | Lack of large, well-annotated databases for portable devices | Limits generalization of models trained on standard clinical ECGs. Makes it difficult to capture artifacts specific to ambulatory use. | [128] |

| D17 | Imbalance between positive classes or between positive and negative classes | Biases the model toward the majority class and reduces performance for clinically important conditions. | [17,18,20,54,55,56,57,58,59,62,64,67,68,69,71,73,74,75,76,80,81,82,83,85,86,88,89,91,92,93,95,98,101,102,107,113,116,118,119,120,121,123,125,126,129,130,131,132,133,136] |

| D18 | Scarcity of sufficiently large, diverse, and annotated databases | Weakens robustness and generalization to new clinical contexts. Leads to overfitting and hinders training of large or complex models. | [17,21,40,53,58,59,62,66,79,80,88,90,93,96,99,102,107,114,121,122,128] |

| D19 | Lack of data standardization or quality | Requires more diverse and labor-intensive preprocessing due to incompatibilities. Complicates cross-validation and benchmarking. | [18,21,57,58,78,79,83,91,126] |

| D20 | Underrepresentation of diverse populations | Introduces bias and limits applicability to generalized clinical use. | [17,18,57,72,92,96,116,126] |

| D21 | Restricted access and privacy issues | Complicates data collection, sharing, and use. Prevents external validation and reproducibility. | [18,20,53,58,59,61,74,78,97,98,100,101,104,107,134] |

| D22 | Different sampling rates across databases | Causes loss of information or signal distortion from resampling. | [57,114,116] |

| D23 | Data from a single source or device | Produces bias toward the source device, excessive dependence on calibration, and poor generalization to other datasets. Overestimates model capability and reduces external validity. | [21,57,91,104,106,119,126,127,129,130,131] |

| D24 | Variability among acquisition devices | Creates dependence on specific recording systems, degrades multicenter performance, and hinders cross-validation and benchmarking. | [72,75,78,98] |

| D25 | Limited metadata: age, sex, weight, ethnic origin and population diversity, comorbidities, etc. | Compromises interpretability, fairness, and adaptability of the model to subgroups or vulnerable populations. | [58,59,73,79,80,103] |

| D26 | Limited availability of databases with concurrent pathologies | Prevents training of robust multi-label models and restricts the design of clinically useful models. | [126] |

| D27 | Inconsistent or automated labeling | Leads the model to learn incorrect associations and reduces performance. | [18,55,57,84,89,98,101,102,103,135] |

| D28 | Absence of standardized protocols for acquisition, annotation, and structuring of records in ECG databases | Reduces interoperability between datasets and limits model generalization, transferability, and comparability. | [55,78] |

| D29 | Variability in the number of ECG leads | Reduces model comparability, introduces differences in spatial information, and prevents transfer to devices using different leads. | [70,126] |

| D30 | Dataset coverage restricted to a single pathology | Limits clinical evaluation and prevents training or testing of multi-class and multi-label models. | [110,113] |

| D31 | Inter-database variability in ECG recording duration and quality | Complicates model architecture and joint training, leading to uneven or biased learning. | [92,93] |

| D32 | Fine-tuning | Requires large, high-quality clinical datasets. | [110] |

| D33 | Different recording durations across databases | Increases computational complexity and training difficulty. Performs poorly on long signals where rare or transient events may occur. | [75,80,85,91,95,116,117,127,129] |

| ID | Difficulty | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| D34 | Pathology similarity | Makes it difficult to extract discriminative features, reducing accuracy in multi-class classification and increasing diagnostic errors. Requires clinically diverse data, precise labeling, and greater model capacity. | [54,58,62,63,71,82,83,88,93,95,97,106,108,113,117,118,123,134] |

| D35 | Comorbidities or multiple concurrent cardiac pathologies | Introduce diagnostic difficulty because one pathology may mask or distort another. Requires well-annotated multi-level databases and more sophisticated architectures capable of learning multiple patterns. | [40,67,82,108,113] |

| D36 | Intra-patient and inter-patient variability | Reduces generalization by blurring physiological and pathological variability. Lowers performance in external cross-validation and limits transferability to new patients. | [18,19,21,53,67,75,78,83,90,93,108,114,120,125,133,136] |

| D37 | Ambiguity in the patterns of certain pathologies | Reduces diagnostic specificity due to inter-class overlap. | [121] |

| D38 | Pathologies with episodic or paroxysmal occurrence | Require long recordings or sequential models; sensitivity is reduced when using short windows. | [17,53,64,68,75,83,87,88,92,93,122,129,133,134] |

| D39 | Subtypes of pathologies | Demand specialized models and finer expert-labeled annotations, increasing complexity and the risk of diagnostic errors. | [72,73,86] |

| D40 | Complex patterns | Require more sophisticated models and larger volumes of annotated data. | [20,21,73,82,83,85,87,92,101,123,128] |

| D41 | Subtle morphological changes in various pathologies | Make detection difficult and require complex models with high resolution or higher sampling rates. | [21,93] |

| D42 | Redundancy of information in the 12-lead ECG | Limits usefulness in deep models, where combinations can be learned automatically, and reduces suitability for portable devices. | [72,131] |

| ID | Difficulty | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| D43 | Presence of excessive or unaccounted noise and artifacts | Increases the risk of losing critical information and reduces model performance in real-world settings. | [17,18,20,58,72,74,75,76,78,79,80,82,85,86,87,90,91,92,93,95,99,114,118,119,120,121,122,125,127,128,129,134,136] |

| D44 | Unrealistic generation of synthetic data | May cause the model to capture non-real features, leading to poor generalization and reduced explainability. | [128] |

| D45 | Absence of standardized metrics for evaluation | Hinders comparison across models; the use of inadequate metrics may obscure poor performance in critical classes. | [18] |

| ID | Technique | Difficulty | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D46 | T02 | Regions highlighted by attention maps do not always match clinically relevant or expected features. | The use of clinical tests has limited acceptance in medical circles as they are neither very useful nor unambiguous. | [59,101] |

| D47 | T03 | Does not allow complete reconstruction of the decision-making process; limited in scenarios with high signal variability. | Restricts transparency; the lack of full traceability of the model’s reasoning hinders acceptance and validation in clinical settings. | [129,131,134] |

| D48 | T07 | Significant overlap of feature maps; generated maps may not display clinically understandable, relevant, or complete patterns | A reduction in visual clarity and difficulty in identifying the ECG areas influencing the results can lead to ambiguity and low clinical trustworthiness. | [78,84,102] |

| D49 | T09 | Explanations can show which areas are important to the model but do not always show areas that the clinician would find important for diagnosis. | Creates misalignment between model logic and clinical reasoning; hinders expert validation and reduces trust in automated decisions. | [60] |

| D50 | T11 | Incorrect assignment of relevance to noisy regions. | Produces false conclusions about ECG regions driving predictions; omits significant features, which may mislead analysts and reduce model reliability. | [78] |

| D51 | T13 | It is not possible to trace the complete reasoning of the model using these means. | Prevents full causal understanding of decisions; reduces transparency and limits reliability in clinical validation. | [97] |

| D52 | T17 | Highlights important regions for the decision without explaining why those regions are relevant. | Obscures the decision-making mechanism, reducing usefulness for clinical analysis or expert validation. | [97,98] |

| D53 | T18 | Identifies important ECG regions without establishing correlation with clinical criteria or validating medical relevance. | Limits interpretability; highlighted regions may be technically relevant but not clinically meaningful, reducing their reliability for practitioners. | [61] |

4.3. Unaddressed Difficulties

| ID | Aspect | Unaddressed Difficulties | Justification of the Affected Activity or Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| D54 | Preprocessing | Lack of dynamic normalization adapted to changing clinical contexts | Limits real-time processing of signals that vary due to physiological, technical, clinical, or temporal factors. |

| D55 | Preprocessing | Absence of standards for preprocessing multichannel signals from different devices | Creates compatibility and robustness issues due to technical differences between sources. |

| D56 | Preprocessing | Absence of automatic quality control of signals in real-world environments | Models trained on diagnostic-quality signals fail to generalize to uncontrolled environments. |

| D57 | Preprocessing | Fixed windows misaligned with clinical events | Windows that do not follow physiological or diagnostic boundaries lead to missed detection of brief events. |

| D58 | DL end-to-end techniques | Lack of automatic hyperparameter tuning mechanisms for deep architectures | Reduces efficiency and slows model experimentation and optimization. |

| D59 | DL end-to-end techniques | Integration of self-supervised techniques to pretrain models with limited data | Self-supervised pretraining reduces dependence on large annotated databases. |

| D60 | DL end-to-end techniques | Lack of real-time adaptation to patient changes during prolonged monitoring | Prevents models from adjusting parameters to individual physiological changes, reducing performance. |

| D61 | Database | Creation of synthetic databases to balance minority classes without compromising quality | Rare patterns should be included without degrading model performance. |

| D62 | Cardiac pathologies | Limited consideration of dynamic changes in pathologies | Hampers classification when pathologies evolve dynamically during prolonged monitoring. |

| D63 | Metrics | Limitations of metrics for evaluating explainability and confidence in model decisions | Undermines adoption in medical contexts where explainability is critical. |

| D64 | Metrics | Lack of correlation between computational metrics and clinical outcomes | Disconnect between metrics and clinical decision-making fails to account for clinical risk, diagnostic urgency, or therapeutic utility, hindering objective comparisons. |

| D65 | Metrics | Metrics with limitations for evaluating temporal sequences and real-time performance | Fail to capture event timing or latency, persistence, or continuity. Short events go undetected, and real-time inference cannot be evaluated. |

| D66 | Metrics | Metrics for multi-class classification | Conceal poor performance in minority classes and fail to reflect differences in clinical risk between classes. |

| D67 | Explainability techniques | Lack of visual tools to interpret decisions on long signals (e.g., Holter recordings) | Prevents reliable interpretation of extended ECG records. |

| D68 | Explainability techniques | Lack of explainability adapted to each pathological class | Current techniques do not distinguish between classes with different clinical criteria; an explanation valid for one class may be inadequate for another. |

| D69 | Explainability techniques | Limitations of explanations in multi-label and multi-lead contexts | Visual techniques merge explanatory information, preventing separation of influences by class or ECG lead. |

| D70 | Explainability techniques | Lack of standardized evaluations to assess agreement with expected clinical findings | Reduces the reliability of techniques and prevents comparability across studies. |

| D71 | Explainability techniques | Misalignment between the explanation’s scale and the clinical event’s scale | Explanations highlight very small regions without clinical correlation in duration. |

5. Discussion

5.1. About Preprocessing

5.2. About End-to-End DL Techniques

5.3. About Databases

5.4. About Cardiac Pathologies: Cardiac Arrhythmias and Ischemia

5.5. About Evaluation Metrics

5.6. About Explainability Techniques

5.7. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joseph, P.; Lanas, F.; Roth, G.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Lonn, E.; Miller, V.; Mente, A.; Leong, D.; Schwalm, J.-D.; Yusuf, S. Cardiovascular Disease in the Americas: The Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease and Its Risk Factors. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2025, 42, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Allen, N.B.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Bansal, N.; Beaton, A.Z.; et al. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 151, e41–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, B.; Jayabaskaran, J.; Jauhari, S.M.; Chan, S.P.; Goh, R.; Kueh, M.T.W.; Li, H.; Chin, Y.H.; Kong, G.; Anand, V.V.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases: Projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zheng, B.; Gong, Y. Global, Regional and National Burden of Ischemic Heart Disease and Its Attributable Risk Factors from 1990 to 2021: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.L.; Zaman, D.; Betancourt, M.T.; Robitaille, C.; Majoni, M.; Blanchard, C.; O’Neill, C.D.; Prince, S.A. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Canadians Living with and Without Cardiovascular Disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2025, 41, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.C.W.; Zheng, B.-B.; Tang, M.-L.; Chu, H.; Zhao, Y.-T.; Weng, C. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Its Risk Factors, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. QJM Int. J. Med. 2025, 118, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-X.; Zheng, Z.-Y.; Peng, Z.-X.; Ni, H.-G. Global Impact of PM2.5 on Cardiovascular Disease: Causal Evidence and Health Inequities across Region from 1990 to 2021. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 124168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalm, J.D.; Joseph, P.; Leong, D.; Lopez-Lopez, J.P.; Onuma, O.; Bhatt, P.; Avezum, A.; Walli-Attaei, M.; McKee, M.; Salim, Y. Cardiovascular Disease in the Americas: Optimizing Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2025, 42, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Almorós, A.; Casado Cerrada, J.; Álvarez-Sala Walther, L.-A.; Méndez Bailón, M.; Lorenzo González, Ó. Atrial Fibrillation and Diabetes Mellitus: Dangerous Liaisons or Innocent Bystanders? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornej, J.; Börschel, C.S.; Benjamin, E.J.; Schnabel, R.B. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st Century: Novel Methods and New Insights. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, D.; Gawalko, M.; Betz, K.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Vinter, N.; Guo, Y.; Johnsen, S. Atrial Fibrillation: Epidemiology, Screening and Digital Health. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2024, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, Y.; Mourad, O.; Qaraqe, K.; Serpedin, E. Deep Learning for ECG Arrhythmia Detection and Classification: An Overview of Progress for Period 2017–2023. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1246746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unnithan, D.R.; Jeba, J.R. A Novel Framework for Multiple Disease Prediction in Telemedicine Systems Using Deep Learning. Automatika 2024, 65, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C., D.; J, N. Cardio Vascular Disease Prediction by Deep Learning Based on IOMT: Review. Smart Sci. 2025, 13, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F.; Alfarhood, S.; Safran, M.; Che, D. Deep Learning-Based IoT System for Remote Monitoring and Early Detection of Health Issues in Real-Time. Sensors 2023, 23, 5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Fan, Z. A Novel Bidirectional LSTM Network Based on Scale Factor for Atrial Fibrillation Signals Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 76, 103663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; MacLachlan, S.; Yu, L.; Herbozo Contreras, L.F.; Truong, N.D.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Kavehei, O. Generalization Challenges in ECG Deep Learning: Insights from Dataset Characteristics and Attention Mechanism. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Automated Detection of Myocardial Infarction Based on an Improved State Refinement Module for LSTM/GRU. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 152, 102865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopannejad, S.; Roshanpoor, A.; Sadoughi, F. Attention-Assisted Hybrid CNN-BILSTM-BiGRU Model with SMOTE–Tomek Method to Detect Cardiac Arrhythmia Based on 12-Lead Electrocardiogram Signals. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241234624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Si, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H. Clinical Knowledge-Based ECG Abnormalities Detection Using Dual-View CNN-Transformer and External Attention Mechanism. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesley, K. Huszar’s ECG and 12-Lead Interpretation, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 978-0-323-71195-1. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, T.B. 12-Lead ECG: The Art of Interpretation, 2nd ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-7637-7351-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, J.; Hampton, J.; Adlam, A. The ECG Made Easy, 9th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 978-0-7020-7457-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland Clinic. Heart Conduction System; Cleveland Clinic: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, F.H. ECG Core Curriculum, 1st ed.; McGraw Hill/Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-0-07-178522-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mayapur, P. A Review on Detection and Performance Analysis on R-R Interval Methods for ECG. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 11019–11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, S.; Mastenbjörk, M. EKG/ECG Interpretation: Everything You Need to Know about the 12-Lead EKG/ECG Interpretation and How to Diagnose and Treat Arrhythmias, 2nd ed.; Medical Creations: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-7347413-5-3. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez Rodríguez, D. ECG: Electrocardiografía, 4th ed.; Marban: Madrid, Spain, 2020; ISBN 978-84-17184-98-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Guo, C. Deep Learning and Electrocardiography: Systematic Review of Current Techniques in Cardiovascular Disease Diagnosis and Management. BioMed Eng. OnLine 2025, 24, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Yao, T.; Wu, C.; Ni, J. Deep Learning for Personalized Electrocardiogram Diagnosis: A Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.07975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Lee, K.; Mokhtar, S.A.; Ismail, I.; Pauzi, A.L.B.M.; Zhang, Q.; Lim, P.Y. Deep Learning-Based ECG Arrhythmia Classification: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schots, B.B.S.; Pizarro, C.S.; Arends, B.K.O.; Oerlemans, M.I.F.J.; Ahmetagić, D.; van Der Harst, P.; van Es, R. Deep Learning for Electrocardiogram Interpretation: Bench to Bedside. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 55, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamate, E.; Piraianu, A.-I.; Ciobotaru, O.R.; Crassas, R.; Duca, O.; Fulga, A.; Grigore, I.; Vintila, V.; Fulga, I.; Ciobotaru, O.C. Revolutionizing Cardiology through Artificial Intelligence—Big Data from Proactive Prevention to Precise Diagnostics and Cutting-Edge Treatment—A Comprehensive Review of the Past 5 Years. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Costanzo, A.; Spaccarotella, C.A.M.; Esposito, G.; Indolfi, C. An Artificial Intelligence Analysis of Electrocardiograms for the Clinical Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.Y.; Yaqoob, M.; Ishaq, M.; Flushing, E.F.; Mangalote, I.A.C.; Dakua, S.P.; Aboumarzouk, O.; Righetti, R.; Qaraqe, M. A Survey of Transformers and Large Language Models for ECG Diagnosis: Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, J.G. Acute Myocardial Infarction: Perspectives on Physiopathology of Myocardial Injury and Protective Interventions. In Cardiac Diseases-Novel Aspects of Cardiac Risk, Cardiorenal Pathology and Cardiac Interventions; Gaze, D.C., Kibel, A., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-83968-161-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlang, I.; Maji, A.K.; Saha, G.; Chakrabarti, P.; Jasinski, M.; Leonowicz, Z.; Jasinska, E. Deep Learning Methods for Classification of Certain Abnormalities in Echocardiography. Electronics 2021, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjoob, K.; Bond, R.; Finlay, D.; McGilligan, V.; Leslie, S.J.; Rababah, A.; Iftikhar, A.; Guldenring, D.; Knoery, C.; McShane, A.; et al. Machine Learning and the Electrocardiogram over Two Decades: Time Series and Meta-Analysis of the Algorithms, Evaluation Metrics and Applications. Artif. Intell. Med. 2022, 132, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Shi, J.; Chang, S.; Wang, H.; He, J.; Huang, Q. MaeFE: Masked Autoencoders Family of Electrocardiogram for Self-Supervised Pretraining and Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 2502015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, R.; Baines, O.; Hayes, A.; Tompkins, K.; Kalla, M.; Holmes, A.P.; O’Shea, C.; Pavlovic, D. Impact of Obesity on Atrial Fibrillation Pathogenesis and Treatment Options. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.; Dastmalchi, L.N.; Gulati, M.; Michos, E.D. A Heart-Healthy Diet for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Where Are We Now? Vasc. Heal. Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, J.; Simard, C.; Drolet, B. Overview of Cardiac Arrhythmias and Treatment Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Yang, G.; Dong, H.; Liang, X.; He, Y. Impact of Cardiovascular Disease on Health-Related Quality of Life among Older Adults in Eastern China: Evidence from a National Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1300404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, H.; Mohammadzadeh, J.; Mirhosseini, S.M.; Nikravanshelmani, A. Early Prediction of Cardiac Arrhythmia Based on Active Fuzzy Deep Learning. Fuzzy Optim. Model. J. 2025, 6, 062506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, O.A.; Cavus, N. A Systematic Review on the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Electrocardiograms in Cardiology. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 195, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velandia, H.; Pardo, A.; Vera, M.I.; Vera, M. Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence and Electrocardiography for Cardiovascular Disease Diagnosis. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical Report EBSE 2007-001; Keele University: Keele, UK; University of Durham: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, N.; Gital, A.Y.; Aljojo, N.; Chiroma, H.; Adewole, K.S.; Mojeed, H.A.; Faruk, N.; Abdulkarim, A.; Emmanuel, I.; Folawiyo, Y.Y.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Data Analysis on the Applications of Deep Learning in Electrocardiogram. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 9677–9750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhushan, M.; Pandit, A.; Garg, A. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for the Analysis of Heart Disease: A Systematic Literature Review, Open Challenges and Future Directions. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 14035–14086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.W.; Wang, S.L.; Qi, X.Z.; Samuri, S.M.; Yang, C. Review of ECG Detection and Classification Based on Deep Learning: Coherent Taxonomy, Motivation, Open Challenges and Recommendations. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 74, 103493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, P.; Yang, H. CLECG: A Novel Contrastive Learning Framework for Electrocardiogram Arrhythmia Classification. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2021, 28, 1993–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y. An Arrhythmia Classification Model Based on Vision Transformer with Deformable Attention. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wu, M.; Li, J.; Liu, C. ECG-CL: A Comprehensive Electrocardiogram Interpretation Method Based on Continual Learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 5225–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.-J.; Chen, H.-Y.; Zhong, W.-B.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Song, J.-Y.; Guo, S.-D.; Qi, L.-X.; Chen, C.Y.-C. A Multi-Task Group Bi-LSTM Networks Application on Electrocardiogram Classification. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2019, 8, 1900111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashou, A.H.; Ko, W.-Y.; Attia, Z.I.; Cohen, M.S.; Friedman, P.A.; Noseworthy, P.A. A Comprehensive Artificial Intelligence–Enabled Electrocardiogram Interpretation Program. Cardiovasc. Digit. Health J. 2020, 1, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.; Truong, S.; Brijesh, P.; Adjeroh, D.A.; Le, N. sCL-ST: Supervised Contrastive Learning with Semantic Transformations for Multiple Lead ECG Arrhythmia Classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 2818–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Chen, X.; Hu, S. Application of an End-to-End Model with Self-Attention Mechanism in Cardiac Disease Prediction. Front. Physiol. 2024, 14, 1308774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Tao, Y.; Fu, J. Automatic Classification System of Arrhythmias Using 12-Lead ECGs with a Deep Neural Network Based on an Attention Mechanism. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wen, A.; Ren, Y. An End-to-End Model for ECG Signals Classification Based on Residual Attention Network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 80, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Jung, S.; Gil, Y.; Choi, J.-I.; Son, H.S. ECG-Signal Multi-Classification Model Based on Squeeze-and-Excitation Residual Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y.; Chen, C.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Shu, M. Automatic Detection of Atrial Fibrillation Based on CNN-LSTM and Shortcut Connection. Healthcare 2020, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnaparkhi, A.; Deshpande, P.; Ghule, G. A Framework for Segmentation and Classification of Arrhythmia Using Novel Bidirectional LSTM Network. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2021, 10, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.S.; Dandapat, S. Morphology-Aware ECG Diagnostic Framework with Cross-Task Attention Transfer for Improved Myocardial Infarction Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 4007811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Luo, D.; Ge, Y.; Chang, S.; Wang, H.; He, J.; Huang, Q. An Adaptive Threshold-Based Semi-Supervised Learning Method for Cardiovascular Disease Detection. Inf. Sci. 2024, 677, 120881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Shen, S.; Zhou, B.; Wang, Z. Multiscale Residual Network Based on Channel Spatial Attention Mechanism for Multilabel ECG Classification. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 630643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lian, C.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, B.; Zang, J.; Zhang, Z. A Multi-View Multi-Scale Neural Network for Multi-Label ECG Classification. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2023, 7, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Jin, Y.; Ko, B.; Kim, M.-S. K-Labelsets Method for Multi-Label ECG Signal Classification Based on SE-ResNet. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, D.; Liu, A.; Gao, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. MLBF-Net: A Multi-Lead-Branch Fusion Network for Multi-Class Arrhythmia Classification Using 12-Lead ECG. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2021, 9, 1900211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Lu, L.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, T.; Liang, Z.; Clifton, D.A.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.-T. Semi-Supervised Learning for Multi-Label Cardiovascular Diseases Prediction: A Multi-Dataset Study. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 3305–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lv, J.; Kong, D. CNN-FWS: A Model for the Diagnosis of Normal and Abnormal ECG with Feature Adaptive. Entropy 2022, 24, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, W.; Zhao, L.; Huang, W.; Wang, L.; Sun, A.; Li, L.; Mo, F. Acute Myocardial Infarction Detection Using Deep Learning-Enabled Electrocardiograms. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 654515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoud, A.S.; Mengash, H.A.; Eltahir, M.M.; Almalki, N.S.; Alnfiai, M.M.; Salama, A.S. Automated Arrhythmia Classification Using Farmland Fertility Algorithm with Hybrid Deep Learning Model on Internet of Things Environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 8265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleem, M.N.; Islam, M.S.; Al-Ahmadi, S.; Soudani, A. Multiscale Encoding of Electrocardiogram Signals with a Residual Network for the Detection of Atrial Fibrillation. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Kadian, T.; Shetty, M.K.; Gupta, A. Explainable AI Decision Model for ECG Data of Cardiac Disorders. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 75, 103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzato, R.; Beritelli, F. Automatic ECG Diagnosis Using Convolutional Neural Network. Electronics 2020, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, T.; Beinecke, J.M.; Krefting, D.; Müller, C.; Dathe, H.; Seidler, T.; Spicher, N.; Hauschild, A.-C. Analysis of a Deep Learning Model for 12-Lead ECG Classification Reveals Learned Features Similar to Diagnostic Criteria. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 28, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Han, B.; Shi, Y.; Ji, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Luo, J. Accurate Detection of Atrial Fibrillation from 12-Lead ECG Using Deep Neural Network. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 116, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.-C.; Yao, B.; Chen, B.-Q. Atrial Fibrillation Detection Using an Improved Multi-Scale Decomposition Enhanced Residual Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 89152–89161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C.; Hsieh, P.-H.; Wu, M.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Tsai, F.-J.; Shih, E.S.C.; Hwang, M.-J.; Huang, T.-C. Usefulness of Machine Learning-Based Detection and Classification of Cardiac Arrhythmias With 12-Lead Electrocardiograms. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.-C.; Hsieh, P.-H.; Wu, M.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Wei, J.-T.; Shih, E.S.C.; Hwang, M.-J.; Lin, W.-Y.; Lin, W.-T.; Lee, K.-J.; et al. Usefulness of Multi-Labelling Artificial Intelligence in Detecting Rhythm Disorders and Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction on 12-Lead Electrocardiogram. Eur. Heart J.-Digit. Health 2021, 2, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, M.; Qu, Y.; Jin, B. Constrained Transformer Network for ECG Signal Processing and Arrhythmia Classification. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhu, W.; Li, D.; Wang, L. Multi-Label Classification of Arrhythmia Using Dynamic Graph Convolutional Network Based on Encoder-Decoder Framework. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 95, 106348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-W.; Hong, D.-Y.; Jung, C.; Hwang, E.; Park, S.-H.; Roh, S.-Y. A Multi-View Learning Approach to Enhance Automatic 12-Lead ECG Diagnosis Performance. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 93, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Hwang, H.-G.; Tseng, V.S. Convolutional Neural Network Based Automatic Screening Tool for Cardiovascular Diseases Using Different Intervals of ECG Signals. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 203, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Xu, B.; Yan, S.; Xu, J. Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Classification Based on Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2020, 17, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z. An End-to-End Atrial Fibrillation Detection by a Novel Residual-Based Temporal Attention Convolutional Neural Network with Exponential Nonlinearity Loss. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 212, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Jiang, X.; Tong, Z.; Feng, P.; Zhou, B.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.; Pang, Y. Multi-Label Correlation Guided Feature Fusion Network for Abnormal ECG Diagnosis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 233, 107508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, J. An Intelligent Computer-Aided Diagnosis Approach for Atrial Fibrillation Detection Based on Multi-Scale Convolution Kernel and Squeeze-and-Excitation Network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.H.; Hoang, V.M.; Pham, M.T. Automatic Varied-Length ECG Classification Using a Lightweight DenseNet Model. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 82, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.U.; Mohd Zahid, M.S.; Abdullah, T.A.; Husain, K. Classification of Cardiac Arrhythmia Using a Convolutional Neural Network and Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 205520762211027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhao, N.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H. Automatic Cardiac Arrhythmia Classification Using Combination of Deep Residual Network and Bidirectional LSTM. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 102119–102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiriyannaiah, S.; G M, S.; M H M, K.; Srinivasa, K.G. A Comparative Study and Analysis of LSTM Deep Neural Networks for Heartbeats Classification. Health Technol. 2021, 11, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-H.; Li, Y.-S.; Hwang, B.-J.; Hsiao, C.-H. Detection of Atrial Fibrillation Using 1D Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2020, 20, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-H.; Kim, T.Y.; Yoon, D. Effectiveness of Transfer Learning for Deep Learning-Based Electrocardiogram Analysis. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2021, 27, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.-Y.; Kwon, J.; Jeon, K.-H.; Cho, Y.-H.; Shin, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-J.; Jung, M.-S.; Ban, J.-H.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Detection and Classification of Arrhythmia Using an Explainable Deep Learning Model. J. Electrocardiol. 2021, 67, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.-Y.; Cho, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kwon, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Jeon, K.-H.; Cho, S.; Park, J.; Oh, B.-H. Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Detect Atrial Fibrillation Using Electrocardiogram. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 328, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaouni, N.; Aul, F.; Krischker, L.; Schmalhofer, S.; Hedrich, L.; Schulz, M.H. Energy Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Arrhythmia Detection. Array 2022, 13, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.; Doggart, P.; Smith, S.W.; Finlay, D.; Guldenring, D.; Bond, R.; McCausland, C.; McLaughlin, J. Device Agnostic AI-Based Analysis of Ambulatory ECG Recordings. J. Electrocardiol. 2022, 74, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Sunwoo, M.H. An Automated Cardiac Arrhythmia Classification Network for 45 Arrhythmia Classes Using 12-Lead Electrocardiogram. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 44527–44538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-K.; Jung, S.; Park, J.; Han, S.W. Arrhythmia Detection Model Using Modified DenseNet for Comprehensible Grad-CAM Visualization. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 73, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.H.; Pham, H.H.; Nguyen, T.B.T.; Nguyen, T.A.; Thanh, T.N.; Do, C.D. LightX3ECG: A Lightweight and eXplainable Deep Learning System for 3-Lead Electrocardiogram Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 85, 104963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Jiang, X.; Liu, L.; Han, B.; Zhang, L.; Wei, S. An Atrial Fibrillation Detection Algorithm Based on Lightweight Design Architecture and Feature Fusion Strategy. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 91, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Liu, L.; Han, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S. Diagnosis of Atrial Fibrillation Using Self-Complementary Attentional Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 238, 107565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, R.; Li, K. Inter-Patient Arrhythmia Classification with Improved Deep Residual Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 214, 106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tang, Y.M.; Yu, K.M.; To, S. SLC-GAN: An Automated Myocardial Infarction Detection Model Based on Generative Adversarial Networks and Convolutional Neural Networks with Single-Lead Electrocardiogram Synthesis. Inf. Sci. 2022, 589, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Long, X.; Sheng, W.; Vullings, R.; Yang, M.; Zhao, L.; Aarts, R.M.; Li, J.; Liu, C. An Atrial Fibrillation Detection Strategy in Dynamic ECGs With Significant Individual Differences. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 4002010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumiaa, M.-A.; Elhabbari, S.; Mansouri, M. The Use of the Multi-Scale Discrete Wavelet Transform and Deep Neural Networks on ECGs for the Diagnosis of 8 Cardio-Vascular Diseases. Mendel 2022, 28, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.; Liao, M.-T.; Chen, T.-L.; Lee, C.-K.; Chou, C.-Y.; Wang, W. Few-Shot Transfer Learning for Personalized Atrial Fibrillation Detection Using Patient-Based Siamese Network with Single-Lead ECG Records. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 144, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayya, M.; Nemri, N.; Alharbi, L.A.; Nour, M.K.; Alnfiai, M.M.; Abdullah Al-Hagery, M.; Salem, N.M.; Al Duhayyim, M. Improved Bat Algorithm with Deep Learning-Based Biomedical ECG Signal Classification Model. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 74, 3151–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarov, B.; Baikuvekov, M.; Momynkulov, Z.; Kassenkhan, A.; Nuralykyzy, S.; Iglikova, M. Convolutional LSTM Network for Heart Disease Diagnosis on Electrocardiograms. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 76, 3745–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakararao, E.; Dandapat, S. Attentive RNN-Based Network to Fuse 12-Lead ECG and Clinical Features for Improved Myocardial Infarction Diagnosis. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2020, 27, 2029–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Liang, S.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F. Exploiting Feature Fusion and Long-Term Context Dependencies for Simultaneous ECG Heartbeat Segmentation and Classification. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2021, 11, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Kim, H.; Seo, W.-Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Shin, J.-M.; Kim, D.-K.; Park, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, N. Enhancing the Performance of Premature Ventricular Contraction Detection in Unseen Datasets through Deep Learning with Denoise and Contrast Attention Module. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 166, 107532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Pratiher, S.; Alam, S.; Hari, A.; Banerjee, N.; Ghosh, N.; Patra, A. A Deep Residual Inception Network with Channel Attention Modules for Multi-Label Cardiac Abnormality Detection from Reduced-Lead ECG. Physiol. Meas. 2022, 43, 064005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Hao, M.; Zhang, X. MMA-RNN: A Multi-Level Multi-Task Attention-Based Recurrent Neural Network for Discrimination and Localization of Atrial Fibrillation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 89, 105747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfai, H.; Saleh, H.; Al-Qutayri, M.; Mohammad, M.B.; Tekeste, T.; Khandoker, A.; Mohammad, B. Lightweight Shufflenet Based CNN for Arrhythmia Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 111842–111854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Rehman, S.U.; Tu, S.; Mehmood, R.M.; Fawad; Ehatisham-ul-haq, M. A Hybrid Deep CNN Model for Abnormal Arrhythmia Detection Based on Cardiac ECG Signal. Sensors 2021, 21, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. A Deep Learning Approach for Atrial Fibrillation Signals Classification Based on Convolutional and Modified Elman Neural Network. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 102, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, X. A Deep Learning Refinement Strategy Based on Efficient Channel Attention for Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter Signals Identification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 130, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S. An Improved Deep Learning Approach Based on Exponential Moving Average Algorithm for Atrial Fibrillation Signals Identification. Neurocomputing 2022, 513, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. An Intelligent Computer-Aided Approach for Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter Signals Classification Using Modified Bidirectional LSTM Network. Inf. Sci. 2021, 574, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Automated Detection of Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter in ECG Signals Based on Convolutional and Improved Elman Neural Network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 193, 105446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Automated Detection of Premature Ventricular Contraction Based on the Improved Gated Recurrent Unit Network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 208, 106284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, G.; Yu, X.; Ye, M.; Liu, L.; Ling, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, D.; Zhou, B.; Liu, Y.; et al. Deep Learning Networks Accurately Detect ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Culprit Vessel. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 797207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yan, H.; Wu, X. ECG Signal Classification with Binarized Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 121, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Stiles, M.K.; Gillis, A.M.; Zhao, J. Enhancing the Detection of Atrial Fibrillation from Wearable Sensors with Neural Style Transfer and Convolutional Recurrent Networks. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Wang, R.; Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. Multi-Class Arrhythmia Detection from 12-Lead Varied-Length ECG Using Attention-Based Time-Incremental Convolutional Neural Network. Inf. Fusion 2020, 53, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, O.; Talo, M.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Tan, R.S.; Acharya, U.R. Accurate Deep Neural Network Model to Detect Cardiac Arrhythmia on More than 10,000 Individual Subject ECG Records. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 197, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lian, C.; Xu, B.; Su, Y.; Alhudhaif, A. 12-Lead ECG Signal Classification for Detecting ECG Arrhythmia via an Information Bottleneck-Based Multi-Scale Network. Inf. Sci. 2024, 662, 120239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gu, H.; Gao, J.; Lu, P.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z. An Effective Atrial Fibrillation Detection from Short Single-Lead Electrocardiogram Recordings Using MCNN-BLSTM Network. Algorithms 2022, 15, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gu, K.; Miao, S.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Y.; Wan, C.; Yu, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, Z.; Shan, T.; et al. Automated Detection of Cardiovascular Disease by Electrocardiogram Signal Analysis: A Deep Learning System. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 10, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, A.; Gao, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. ECG-Based Multi-Class Arrhythmia Detection Using Spatio-Temporal Attention-Based Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 106, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C. Over-Fitting Suppression Training Strategies for Deep Learning-Based Atrial Fibrillation Detection. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2021, 59, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhan, P.; Peng, X. ECG Classification Using Deep CNN Improved by Wavelet Transform. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2020, 64, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayano, Y.M.; Schwenker, F.; Dufera, B.D.; Debelee, T.G.; Ejegu, Y.G. Interpretable Hybrid Multichannel Deep Learning Model for Heart Disease Classification Using 12-Lead ECG Signal. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 94055–94080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba Mahel, A.S.; Al-Gaashani, M.S.A.M.; Alkanhel, R.I.; Hassan, D.S.M.; Muthanna, M.S.A.; Muthanna, A.; Aziz, A. A Multi-Scale Deep Learning Framework Combining MobileViT-ECA and LSTM for Accurate ECG Analysis. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 85473–85492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, F.S.; Wagner, M.F.; Schafer, J.; Ullate, D.G. Toward Automated Feature Extraction for Deep Learning Classification of Electrocardiogram Signals. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 118601–118616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Sun, W.; Guan, J.; You, I. Multi-ECGNet for ECG Arrythmia Multi-Label Classification. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110848–110858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, S.; Tripathy, R.K. SERN-AwGOP: Squeeze-and-Excitation Residual Network with an Attention-Weighted Generalized Operational Perceptron for Atrial Fibrillation Detection. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 34844–34853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Zhu, D. ECG Classification Exercise Health Analysis Algorithm Based on GRU and Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 59842–59850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Mughal, M.R.; Ali Irtaza, S.; Khan, M.; Tahir, M.; Ali, A.; Saeed, Z. A Deep Learning-Based Ultra-Lightweight Architecture for Atrial Fibrillation Detection Using Single-Lead ECG Recordings. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 86474–86486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghawry, E.; Gharib, T.F.; Ismail, R.; Zaki, M.J. An Efficient Heartbeats Classifier Based on Optimizing Convolutional Neural Network Model. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 153266–153275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahim, S.M.; Emamul Hossen, M.; Al Hasan, S.; Islam, M.K.; Iqbal, Z.; Alibakhshikenari, M.; Collotta, M.; Miah, M.S. TransMixer-AF: Advanced Real-Time Detection of Atrial Fibrillation Utilizing Single-Lead Electrocardiogram Signals. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 143149–143162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, T.H.; Woong Ko, Y. HeartNet: Self Multihead Attention Mechanism via Convolutional Network with Adversarial Data Synthesis for ECG-Based Arrhythmia Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 100501–100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Nerbonne, J.; Zhang, Q. Ultra-Efficient Edge Cardiac Disease Detection Towards Real-Time Precision Health. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 9940–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, I.; Qureshi, H.N.; Rizwan, A.; Imran, A. Cardiac Arrhythmia Classification from Lead I ECG Recorded in a Free-Living Environment. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Fan, J.; Li, Y. Deep Multi-Scale Fusion Neural Network for Multi-Class Arrhythmia Detection. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 2461–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubair, M.; Woo, S.; Lim, S.; Kim, D. Deep Representation Learning with Sample Generation and Augmented Attention Module for Imbalanced ECG Classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 2461–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Mutahira, H.; Wei, S.; Muhammad, M.S. ECG-Mamba: Cardiac Abnormality Classification with Non-Uniform-Mix Augmentation on 12-Lead ECGs. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2025, 13, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan Pham, H.; Tran, T.D.; Trung Duong Le, V.; Nakashima, Y. MINA: A Hardware-Efficient and Flexible Mini-InceptionNet Accelerator for ECG Classification in Wearable Devices. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 2025, 72, 2740–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Lee, M.; Song, H.S.; Lee, S.-W. Automatic Cardiac Arrhythmia Classification Using Residual Network Combined with Long Short-Term Memory. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 4005817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Lee, M.; Song, H.S.; Lee, S.-W. Local-Global Temporal Fusion Network with an Attention Mechanism for Multiple and Multiclass Arrhythmia Classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 6569–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannun, A.Y.; Rajpurkar, P.; Haghpanahi, M.; Tison, G.H.; Bourn, C.; Turakhia, M.P.; Ng, A.Y. Cardiologist-Level Arrhythmia Detection and Classification in Ambulatory Electrocardiograms Using a Deep Neural Network. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Qu, X.; Han, B.; Liu, L.; Wei, S. An Atrial Fibrillation Signals Analysis Algorithm in Line with Clinical Diagnostic Criteria. Signal Process. 2025, 236, 110068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rivolta, M.W.; Vaglio, M.; Maison-Blanche, P.; Badilini, F.; Sassi, R. Residual-Attention Deep Learning Model for Atrial Fibrillation Detection from Holter Recordings. J. Electrocardiol. 2025, 89, 153876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Bao, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, M.; He, N.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Y. Research on Atrial Fibrillation Diagnosis in Electrocardiograms Based on CLA-AF Model. Eur. Heart J.-Digit. Health 2025, 6, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toosi, M.H.; Mohammadi-nasab, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Salehi, M.E. Efficient Quantized Transformer for Atrial Fibrillation Detection in Cross-Domain Datasets. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 148, 110371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-H.; Wang, J.-W.; Xie, C.-X.; Lee, Z.-J.; Cai, B.-J.; Chen, T.-Y.; Chen, S.-L.; Chen, C.-A.; Abu, P.A.R.; Yang, T. Hierarchical Multiattention Temporal Fusion Network for Dual-Task Atrial Fibrillation Subtyping and Early Risk Prediction. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yan, M.; Wang, R.; Xie, L. Multiscale Feature Enhanced Gating Network for Atrial Fibrillation Detection. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 261, 108606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Bai, Z.; Yao, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Du, L.; Chen, X.; Ye, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, P.; et al. Advanced Deep Neural Network with Unified Feature-Aware and Label Embedding for Multi-Label Arrhythmias Classification. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2025, 30, 1251–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, P.; Du, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Song, J.; Fang, Z. A Multi-Level Multiple Contrastive Learning Method for Single-Lead Electrocardiogram Atrial Fibrillation Detection. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawahyuni, A.; Sari, W.K.; Afifah, N.; Tutuko, B.; Nurmaini, S.; Marcelino, J.; Isdwanta, R.; Khairunnisa, C.Z. A Deep Learning-Based Myocardial Infarction Classification Based on Single-Lead Electrocardiogram Signal. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2025, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhdar, M.; Mohammed, A.O.; Mstafa, R.J. Advanced Deep Learning Framework for ECG Arrhythmia Classification Using 1D-CNN with Attention Mechanism. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 315, 113301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; He, L.; Long, S.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J.; et al. Advancing Interpretable Cardiac Disease Diagnosis via a Transformer-Convolutional Hybrid Network on Electrocardiograms. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 152, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, K.; K, P.; J, J.S. Efficient Detection of Cardiac Arrhythmias Using Low-Latency Fpga-Accelerated Hybrid Deep Learning Models. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 025277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Wang, C. Adaptive Wavelet Base Selection for Deep Learning-Based ECG Diagnosis: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajardo, C.A.; Parra, A.S.; Castellanos-Parada, T.V. Lightweight Deep Learning for Atrial Fibrillation Detection: Efficient Models for Wearable Devices. Ing. Inv. 2025, 45, e114530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.L.; Choma, M.A.; Onofrey, J.A. Bias in Medical AI: Implications for Clinical Decision-Making. PLoS Digit Health 2024, 3, e0000651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdjanovska, E.; Rashkovska, A. A Framework for Comparative Study of Databases and Computational Methods for Arrhythmia Detection from Single-Lead ECG. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.T.; Lee, S.; King, E.; Liu, T.; Armoundas, A.A.; Bazoukis, G.; Tse, G. Clinical Significance, Challenges and Limitations in Using Artificial Intelligence for Electrocardiography-Based Diagnosis. Int. J. Arrhythm. 2022, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, S.; Pascoal, C.; Francisco, R.; dos Reis Ferreira, V.; Videira, P.A.; Valadão, G. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Rare Diseases: Is the Future Brighter? Genes 2019, 10, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Geng, Q. Multimorbidity in Cardiovascular Disease and Association with Life Satisfaction: A Chinese National Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Fu, S.; Chen, Y.; Ye, K. A Reliable Deep Learning Model for ECG Interpretation: Mitigating Overconfidence and Direct Uncertainty Quantification. Symmetry 2025, 17, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Leur, R.R.; Bos, M.N.; Taha, K.; Sammani, A.; Yeung, M.W.; Van Duijvenboden, S.; Lambiase, P.D.; Hassink, R.J.; Van Der Harst, P.; Doevendans, P.A.; et al. Improving Explainability of Deep Neural Network-Based Electrocardiogram Interpretation Using Variational Auto-Encoders. Eur. Heart J.-Digit. Health 2022, 3, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaiti, S.S.; Bond, R.R. Explainable-by-Design: Challenges, Pitfalls, and Opportunities for the Clinical Adoption of AI-Enabled ECG. J. Electrocardiol. 2023, 81, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, D.; Cárdenas-Grandez, J.; Uribe Godoy, G.V.; Rodríguez Mallma, M.J.; Maculan, N.; Mascaro, P. Maximizing Survival in Pediatric Congenital Cardiac Surgery Using Machine Learning, Explainability, and Simulation Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Addresses the research question Study Type: Original journal article Language: English Period: 2019 to 2025 | Studies not aligned with the objectives of this review. Studies conducted in different contexts (e.g., sleep disorders, diabetes, neonates or fetuses, non-human subjects, drug effects, recent surgeries). Studies focusing on other aspects (e.g., risk factors, treatments, prevention, use of tools other than ECG such as radar, echocardiography, or pulse oximetry, or not employing end-to-end DL). Conference proceedings, posters, editorials, and theses. Studies without contributions or results. |

| Source | Potentially Eligible Articles (n) | Selected Articles (n) | Selected Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 478 | 35 | [19,21,40,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] |

| Web of Science | 1091 | 68 | [17,18,20,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136] |

| PubMed | 0 | 0 | --- |

| IEEE Xplore | 447 | 18 | [137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154] |

| Total | 2016 | 121 | [13,14,15,16,17,30,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,32,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123] |

| ID | Technique Type | Description | Usage Count | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T01 | Noise and Artifact Removal | Noise: Unwanted random signals with a broad spectrum and low amplitude (~0.01–0.1 mV) superimposed on the ECG signal, including thermal and electronic noise. Artifacts: Higher-amplitude distortions (~0.1–10 mV) caused by physiological factors (breathing, muscle movement, physical activity, sweating, pacemakers), technical issues (poor electrode contact, faulty cables), or environmental factors (vibrations, 50/60 Hz interference). Their spectral range is ~0.05–100 Hz and they appear as abrupt spikes, irregular waves, interruptions, or baseline fluctuations around 0.05 Hz. | 61 | [17,19,20,21,40,55,60,64,65,71,72,73,76,79,81,83,87,88,90,94,96,98,99,104,105,106,108,110,112,114,115,119,120,121,122,124,126,130,132,135,136,137,141,142,143,145,146,153,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167] |

| T02 | Amplitude Normalization | Scaling ECG amplitudes into the same range to improve comparability and reduce scale bias. | 57 | [17,19,21,55,60,61,62,63,65,66,68,71,74,75,78,79,80,84,85,86,87,88,90,91,92,98,99,102,104,106,110,115,120,121,122,123,124,127,129,131,132,135,137,141,149,151,153,154,156,159,162,163,164,165,166,167,168] |

| T03 | Segmentation | Dividing the signal into fixed-length segments for efficient processing because DL models require fixed-length inputs. | 66 | [17,18,19,21,40,55,64,65,66,75,78,79,80,83,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,93,95,96,97,99,102,104,105,106,107,108,110,113,114,115,117,118,120,121,122,124,125,126,128,132,133,138,141,142,149,151,153,154,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,169] |

| T04 | Resampling | Ensuring consistent sampling frequencies when using multiple databases. Downsampling is often used to reduce computational load. | 42 | [17,18,19,21,40,53,58,65,66,68,78,87,91,96,99,100,102,104,108,110,113,115,116,121,122,123,124,125,131,132,134,149,151,153,154,156,158,159,162,163,164] |

| T05 | Length Normalization | Applying techniques like padding and cropping to equalize signal length across ECG records. Required because DL models need fixed-length inputs. | 30 | [18,40,58,60,61,63,67,68,70,71,78,84,85,88,89,91,93,95,101,103,112,116,127,129,131,134,141,151,162,163] |

| T06 | Class Balancing | Adjusting class distribution in datasets when classes are unevenly represented. | 16 | [20,63,64,75,80,87,92,93,106,107,114,118,133,144,146,153] |

| T07 | Data Cleaning | Correcting or removing missing, duplicate, or invalid data, including the removal of noisy sections (clipping). | 13 | [20,67,75,76,80,82,83,85,97,98,110,114,140] |

| T08 | Data Augmentation | Enhancing model robustness through synthetic data generation or transformations. May also help balance class distribution. | 16 | [21,53,58,59,65,85,103,110,112,128,129,140,143,145,149,167] |

| T09 | Z-shaped Reconstruction | Converting one-dimensional data into two-dimensional representations. | 1 | [105] |

| T10 | Lead Expansion | Creating new leads by mathematically combining existing ones. | 2 | [67,68] |

| T11 | Wavelet Decomposition | Decomposing the ECG signal into different frequencies or scales to extract features at each level. | 2 | [80,109] |

| T12 | Inter-Patient Variability Reduction | Minimizing ECG variability across patients with the same pathology to improve the generalization of DL models. | 1 | [135] |

| ID | Technique Type | Specific Techniques | Usage Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| T01 | Noise and Artifact Removal | Wavelet | 8 |

| Digital filter | 21 | ||

| LOESS | 1 | ||

| Moving average | 1 | ||

| Smoothing | 1 | ||

| NLM | 2 | ||

| Normalization | 1 | ||

| Thresholding | 2 | ||

| T02 | Amplitude Normalization | Z-score | 49 |

| Min–Max | 7 | ||

| Unit variance | 1 | ||

| T03 | Segmentation | Fixed window | 60 |

| Multiple fixed windows | 3 | ||

| Overlapping sliding windows | 3 | ||

| T04 | Resampling | Downsampling | 40 |

| Upsampling | 2 | ||

| T05 | Length Normalization | Zero-padding | 11 |

| Cropping | 11 | ||

| Trimming | 5 | ||

| Replication | 2 | ||

| Segmentation | 1 | ||

| Resampling | 3 | ||

| Filling | 4 | ||

| T06 | Class Balancing | Oversampling: SMOTE | 4 |

| Oversampling: GAN | 1 | ||

| Oversampling: ADYSAN | 1 | ||

| Downsampling | 2 | ||

| Oversampling | 1 | ||

| Replication | 2 | ||

| Segmentation | 2 | ||

| Data amplification | 2 | ||

| T07 | Data Cleaning | Remove missing values | 2 |

| Remove zeros or NaN data | 2 | ||

| Remove noisy segments | 5 | ||

| Remove duplicates | 1 | ||

| Remove anomalous portions | 2 | ||

| T08 | Data Augmentation | Cropping | 1 |

| Jittering | 1 | ||

| Warping | 1 | ||

| Noise injection | 2 | ||

| Scaling | 2 | ||

| Random sampling | 2 | ||

| Others | 5 | ||

| T09 | Z-shaped Reconstruction | --- | 1 |

| T10 | Lead Expansion | --- | 2 |

| T11 | Wavelet Decomposition | --- | 2 |

| T12 | Inter-Patient Variability Reduction | FFT- and Hanning window-based filter | 1 |

| Family | Representative Techniques | Usage Count | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-based models | CNN, ResNet, DenseNet, Inception, SE-ResNet, ShuffleNet, U-Net, AlexNet-1D, Multi-Resolution CNN, Temporal/Dilated CNN, GoogLeNet, XResNet | 35 | [55,57,62,73,76,77,78,80,86,87,89,91,95,97,98,100,102,106,109,114,118,119,128,133,136,140,144,148,149,152,154,156,169] |

| RNN-based models | LSTM, Bi-LSTM, GRU, BiGRU, Elman | 5 | [64,74,81,82,94] |

| Hybrid CNN-RNN models | CNN–LSTM, CNN–BiLSTM, CNN–GRU, CNN–BiGRU, CNN–BiLSTM–BiGRU, Deep CNN–LSTM | 23 | [17,19,63,84,92,93,99,112,120,123,124,125,126,130,132,135,139,142,143,161,164,167] |

| Transformer-based models | CNN–Transformer, Swin–Transformer, Dual-view Transformers | 8 | [21,54,83,108,131,145,159,166] |

| Attention-enhanced models | SE blocks, channel/spatial/temporal attention, multi-head attention, CNN + SSM | 39 | [18,19,56,59,60,61,65,67,68,69,70,71,79,85,88,90,101,103,104,105,113,115,116,117,121,122,129,134,137,138,141,146,150,151,153,157,158,160,165] |

| Generative/Contrastive | Autoencoder, Contrastive Learning | 7 | [40,53,58,96,110,162,163] |

| Custom/Ensemble/Neural Architecture Search | Reinforcement Learning, Bat Algorithm, Binarized Neural Network, AlexNet-1D Semi-supervised | 4 | [66,111,127,168] |

| ID | Database | fs (Hz) | No. of Records | Record Duration | Access | Leads Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB01 a | AHA ECG Database (AHA) | 500 | 45,152 | 10 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB02 | Asan Medical Center Liver Transplant Database | 500 | 65,932 | 10 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB03 a | AUMC ICU Biosignal Database | 500 | 190,000 | 10–20 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB04 a | Author-collected dataset | 500 | 6877 | 6–60 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB05 | Chinese PLA General Hospital | 200 | 1436 | 6 s–30 min | PUB | I, II |

| DB06 | CPSC-2018 (public set + CPSC-Extra) | 250 | 35 | 8 min | PUB | 1 |

| DB07 | CPSC-2020 | 250 | 35 | 2 h | PUB | 2 |

| DB08 a | CPSC-2021 (V1.0.3) | 500 | 10,344 | 5–10 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB09 a | Custom wearable ECG device recordings | 500 | 32,142 | 10 s | PRIV | I, II, V1–V6 |

| DB10 | Datasets from South Korean University Hospitals | 257 | 75 | 30 min | PUB | 12 |

| DB11 | ECG Arrhythmia Classification Dataset | 360 | 48 | 30 min | PUB | 2 |

| DB12 | Federal Ministry of Education and Research Dataset | 250 | 25 | 10 h | PUB | 2 |

| DB13 | First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University ECG Database | 300 | 8528 | 9–61 s | PUB | 1 |

| DB14 | First People’s Hospital of Guangzhou Database | 1000 | 549 | 2 min | PUB | 12, 3 Frank |

| DB15 a | Korea University Anam Hospital ECG Dataset | 100, 500 | 21,799 | 10 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB16 | Lobachevsky University Database (LUDB) | 500 | 200 | 10 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB17 | Long-Term AF Database (LTAFDB) | 500 | 45,152 | 10 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB18 | Mayo Clinic ECG Database | 250 | 80 | 3 h | PRIV | 2 |

| DB19 | MIMIC-III | 125 | 436 | NR | PRIV | II |

| DB20 | MIT-BIH Malignant Ventricular Arrhythmia Database (VFDB) | 250, 500 | 2,648,100 | NR | PRIV | II |

| DB21 | MIT-BIH Noise Stress Test Database (NSTDB) | NR | 6500 | NR | PRIV | 12 |

| DB22 | MIT-BIH Supraventricular Arrhythmia Database (SVDB) | 500 | NR | 10 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB23 a | Patch Database | 500 | 13,256 | 6–144 s | PUB/PRIV | 12 |

| DB24 a | PhysioNet 2020 | 400 | 10 | ~24 h | PUB | 1 |

| DB25 a | Private 12-lead ECG Dataset | 100–1000 | >100,000 | 5 s–30 min | PUB | 12 |

| DB26 | QT Database (QTDB) | 400 | 29 | 24 h | PRIV | I |

| DB27 a | Shandong Provincial Hospital Database (SPHw) a | NR | 52,043 | 10 s | PRIV | II |

| DB28 | Shandong Provincial Hospital Database (SPH) | NR | 5000 | 10 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB29 | Shandong Provincial Hospital Database (SPHDB) a | 512 | 16,000 | 120 s | PRIV | I, II |

| DB30 | Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital Database (SNPH) | NR | 277,807 | 10–60 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB31 | Shanxi Bethune Hospital Dataset | 1000 | 90 | 10 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB32 | Telehealth Network Minas Gerais (TNMG) | 200 | 28,308 | 10 s | PUB | II |

| DB33 a | Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University Database | 500 | 200 | 10 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB34 | Wearable ECG device recordings | 128 | 84 | 24–25 h | PUB | 2 |

| DB35 a | Wearable long-term ECG device recordings | 500 | 2,499,522 | ~10 s | DUA | 12 |

| DB36 | AHA ECG Database (AHA) | 125 | >67,000 | Up to several weeks | PUB | I, II, III, aVR, V |

| DB37 | Asan Medical Center Liver Transplant Database | 250 | 22 | 30 min | PUB | 2 |

| DB38 | AUMC ICU Biosignal Database | 360 | 12 | 30 min | PUB | 2 |

| DB39 | Author-collected dataset | 128 | 78 | 30 min | PUB | 2 |

| DB40 | Chinese PLA General Hospital | NR | 328 | 30 s | PRIV | 1 |

| DB41 a | CPSC-2018 (public set + CPSC-Extra) | 100–1000 | 43,101 | 5 s–30 min | PUB | 12 |

| DB42 | CPSC-2020 | NR | 549,211 | NR | PRIV | 12 |

| DB43 | CPSC-2021 (V1.0.3) | 250 | 105 | 15 m | PUB | 2 |

| DB44 | Custom wearable ECG device recordings | 200 | NR | 24 h | PUB | 12 |

| DB45 a | Datasets from South Korean University Hospitals | 500 | 25,770 | 10–60 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB46 | ECG Arrhythmia Classification Dataset | 200 | NR | 24 h | PUB | 12 |

| DB47 | Federal Ministry of Education and Research Dataset | 500 | 75,111 | 11–92 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB48 a | First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University ECG Database | 500 | 7000 | NR | PRIV | 12 |

| DB49 a | First People’s Hospital of Guangzhou Database | 300–600 | 2,322,513 | 7–10 s | PUB | 12 |

| DB50 | Korea University Anam Hospital ECG Dataset | 1000 | 793 | 10 s | PRIV | 12 |

| DB51 | Lobachevsky University Database (LUDB) | 500 | 5189 | NR | PRIV | 12 |

| DB52 | Long-Term AF Database (LTAFDB) | 400 | 12 | ~2 days | PRIV | 12 |

| ID | Technique | Description | Type of Explainability | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE01 | Activation Maps | Enable understanding of how a model processes inputs across different convolutional layers. | Post hoc Integrated | [118] |

| TE02 | Attention Maps | Visualize the spatial or temporal distribution of the attention learned by the model. | Post hoc | [115] |

| TE03 | Attention Mechanism | Allocates weights to portions of the input according to their importance for classification. | Integrated | [18,21,54,56,59,61,67,85,88,103,104,113,116,117,123,129,131,134,138,141,146,157,159,165,166] |

| TE04 | Embedding Visualization | Shows how internal representations are organized in the model’s latent space. | Post hoc | [83] |

| TE05 | Feature Heatmaps | Highlight the local importance of features over the input, typically in the temporal domain. | Post hoc | [105] |

| TE06 | Global Channel Attention Block (GCAB) | Assigns weights to input channels to emphasize the most relevant ones. | Integrated | [101] |

| TE07 | Grad-CAM | Generates activation maps to identify the input regions most relevant for prediction. | Post hoc | [21,60,65,68,84,91,93,102,131,134,137,145,154,156,160,161,166,168] |

| TE08 | Gradient-based Visualization | Visualizes gradient magnitudes with respect to the input as an indicator of importance. | Post hoc | [121] |

| TE09 | Heatmaps | Display the intensity of a feature at each point of input. | Post hoc | [114] |

| TE10 | Integrated Gradients | Accumulates gradients between a baseline signal and the actual input to estimate feature importance. | Post hoc | [78] |

| TE11 | Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) | Propagates relevance scores back to the input layers to identify key regions. | Post hoc | [78] |

| TE12 | Lead-wise Grad-CAM | Applies Grad-CAM individually to each ECG lead to show its contribution to the prediction. | Post hoc | [103] |