Abstract

Background: Pleural effusion (PE) is a common condition where accurate detection is essential for management. Thoracic ultrasound (TUS) is the first-line modality owing to safety, portability, and high sensitivity, but accuracy is operator-dependent. Artificial intelligence (AI)-based automated analysis has been explored as an adjunct, with early evidence suggesting potential to reduce variability and standardise interpretation. This review evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of AI-assisted TUS for PE detection. Methods: This review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251128416) and followed PRISMA guidelines. MEDLINE, Scopus, Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, Cochrane CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched through 20 August 2025 for studies assessing AI-based TUS analysis for PE. Eligible studies required recognised reference standards (expert interpretation or chest CT). Risk of bias was assessed with QUADAS-2, and certainty with GRADE. Owing to heterogeneity, structured narrative synthesis was performed instead of meta-analysis. Results: Five studies (7565 patients) published between 2021–2025 were included. All used convolutional neural networks with varied architectures (ResNet, EfficientNet, U-net). Sensitivity ranged 70.6–100%, specificity 67–100%, and AUC 0.77–0.99. Performance was reduced for small, trace, or complex effusions and in critically ill patients. External validation showed attenuation compared with internal testing. All studies had high risk of bias in patient selection and index test conduct, reflecting retrospective designs and inadequate dataset separation. Conclusions: AI-assisted TUS shows promising diagnostic performance for PE detection in curated datasets; however, evidence is inconsistent and limited by key methodological weaknesses. Overall certainty is low-to-moderate, constrained by retrospective designs, limited dataset separation, and scarce external validation. Current evidence is insufficient to support routine clinical use. Robust prospective multicentre studies with rigorous independent validation and evaluation of clinically meaningful outcomes are essential before clinical implementation can be considered.

1. Introduction

Pleural diseases include a broad spectrum of pathological conditions, often presenting with pleural effusion (PE), and are classified as neoplastic—such as mesothelioma and metastatic lesions—or non-neoplastic, including infections, fibrosis, plaques, and pneumothorax [1,2,3,4]. Common symptoms include dyspnoea, chest pain, and cough, although early stages may be asymptomatic [5,6,7,8]. These disorders are associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and reduced quality of life, representing a frequent cause of hospital admission worldwide, including over 350,000 in the United States annually, with rising global incidence and healthcare costs [9,10,11,12].

PE is among the most frequent thoracic conditions, arising from diverse disorders, including heart failure, infections, malignancies, autoimmune, and inflammatory diseases [4,13,14]. Beyond etiological diagnosis, its presence often indicates disease progression, therapeutic failure, and/or the need for urgent intervention [3,15]. Accurate and timely detection is therefore critical for patient management and outcomes [6,7,16].

Traditional evaluation relies on chest radiography and computed tomography [12,17,18,19,20]. Chest X-rays are widely accessible and inexpensive but with a limited accuracy in detecting small or loculated effusions and differentiating pleural thickening [21]. Chest CT scan provides superior anatomical detail but is costly, it involves greater radiation exposure, and it is often impractical for bedside assessment in critically ill patients [17,18].

Thoracic ultrasound (TUS) has transformed the diagnostic evaluation of pleural disorders. Beyond its established role in guiding safe procedures, it enables bedside assessment of pleural pathology and is increasingly recognised as a field of active research with both clinical and academic significance [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. It offers real-time imaging, portability, absence of radiation, procedural guidance, and cost-effectiveness, with sensitivity and specificity for PE frequently exceeding 95% [29]. TUS is widely applicable in emergency, intensive care, outpatient, and point-of-care settings [13,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

However, it remains operator-dependent, with accuracy influenced by training, protocol adherence, anatomical familiarity, and patient factors such as obesity or subcutaneous emphysema [38]. Inter-observer variability and technical limitations can reduce diagnostic consistency, highlighting the need for standardised training and supportive technologies [39].

Artificial intelligence (AI) has introduced transformative potential across medicine, enabling data-driven decision support, predictive analytics, and workflow optimisation [40,41,42,43,44,45]. In respiratory medicine, AI has been increasingly explored across diverse domains, including the assessment of pulmonary function, disease phenotyping, and patient risk stratification [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. In imaging, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL)—including convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—have enhanced automated recognition, quantification, and pattern detection across organ systems, often matching or exceeding expert human performance [54,55,56,57]. In TUS, AI has been investigated for applications such as automated B-line quantification, pneumonia detection, and pneumothorax identification, showing preliminary evidence of reproducible accuracy and potential to reduce operator dependency [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. AI-assisted analysis in PE could have the potential to enhance diagnostic confidence, reduce cognitive burden, expedite interpretation, support training, and facilitate triage in resource-limited settings [57]. It may also contribute to reduced reliance on confirmatory imaging, more efficient workflows, and potential cost savings. Nevertheless, the current evidence remains fragmented, with considerable heterogeneity, limited external validation, and persisting gaps regarding performance in complex cases, integration into clinical practice, and overall cost-effectiveness [67,68]. In addition, beyond diagnostic performance, the interpretability of AI models remains a critical barrier to clinical adoption. Current explainability approaches in AI-assisted PE detection are heterogeneous and often superficial, limiting clinician trust and regulatory readiness [69,70,71,72,73,74].

Given the clinical significance of PE and the transformative potential of AI-assisted TUS, a rigorous synthesis of the existing evidence is warranted. While we recently published a narrative review providing a broad educational overview of advanced imaging and AI across the entire spectrum of pleural diseases and multiple imaging modalities [56], the present work represents a fundamentally different contribution in scope, methodology, and clinical applicability. This systematic review addresses a single, focused clinical question—the diagnostic accuracy of AI-assisted thoracic ultrasound for pleural effusion detection—through rigorous PRISMA-compliant methodology with prospective protocol registration, standardized quality assessment, and certainty of evidence evaluation (detailed in Section 2). Unlike the narrative format, which served as an educational introduction without systematic evidence synthesis, this review systematically aggregates diagnostic performance data across studies, critically appraises methodological quality and generalizability, evaluates explainability implementation, and provides actionable guidance on current clinical readiness and future validation requirements. By systematically examining model architectures, validation strategies, and reported diagnostic performance, this work—representing to our knowledge the first systematic review specifically evaluating this AI application—aims to delineate the current state of evidence, highlight methodological strengths and limitations, and provide guidance for future research and potential clinical integration.

2. Methods

2.1. Review Design

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251128416) and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [75,76]. The study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of AI-based automated analysis applied to TUS for the detection of PE.

Evidence regarding AI model performance was systematically extracted, and methodological quality and certainty of findings were critically appraised. Heterogeneity was assessed across four predefined domains: (1) clinical, including differences in prevalence and patient populations; (2) methodological, encompassing study design (retrospective versus prospective) and validation strategies (cross-validation versus external validation); (3) AI architecture, considering the diversity of model families, input formats, and output types; and (4) technical, addressing variability in data preprocessing and augmentation pipelines.

Given the fundamental differences in prediction tasks [77], model architectures, and input/output formats across studies, quantitative meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate in accordance with Cochrane guidance.

Consequently, a structured narrative synthesis, supported by tabular summaries, was used to comprehensively report diagnostic performance and model characteristics.

The complete PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided as Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Research Question

In patients undergoing TUS for suspected PE (P), how accurately does AI-based automated analysis of the scan (I) detect PE compared with expert interpretation and/or chest CT scan (C), as measured by sensitivity, specificity, and AUC (O)?

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Population

Studies enrolling patients of any age or sex who underwent TUS for suspected PE were eligible. Eligible settings included emergency departments, intensive care units, respiratory or general medicine wards, and outpatient clinics. Only studies written in English were considered, without geographic or socioeconomic restrictions. Excluded were animal or in vitro studies, case reports and studies addressing pleuropulmonary conditions other than PE without separable effusion data.

2.3.2. Index Test

Eligible studies evaluated AI-based automated analysis techniques applied to TUS images or video clips for PE detection. Included AI models comprised DL approaches, CNNs, ensemble methods, or other algorithmic frameworks. Both fully and semi-automated AI systems intended to support or replace human interpretation were considered. Excluded were studies relying solely on manual interpretation, AI applied to other imaging modalities (CT, X-ray, MRI), or studies exclusively focused on other pleuropulmonary conditions without separable PE data.

2.3.3. Reference Standard

Studies were required to include a recognized reference standard for PE diagnosis, including radiologist or expert clinician interpretation, or clinically confirmed diagnosis supported by imaging techniques (chest CT scan or chest X-Ray). Studies without a defined reference standard, comparisons with non-imaging modalities not directly related to PE, or comparisons solely between AI models without a human or standard reference comparator were excluded.

2.4. Outcomes

Primary outcomes: Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), overall accuracy, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of AI-based techniques for PE detection.

Secondary outcomes: Comparative diagnostic performance of AI versus human clinicians; subgroup analyses in specific patient populations (e.g., small or complex effusions, critically ill patients).

2.5. Eligible Studies

Eligible study designs encompassed prospective and retrospective cohort studies, diagnostic accuracy studies, cross-sectional investigations, and randomized controlled trials evaluating AI-assisted diagnostic strategies, conducted in either single-center or multicenter settings. Excluded were case reports, small case series (<10 patients), reviews, editorials, commentaries, and conference abstracts lacking complete diagnostic data.

2.6. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in collaboration with a professional medical librarian. The following databases and sources were systematically searched: MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, the Cochrane CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov. EMBASE was not accessed due to institutional subscription limitations; however, this limitation was mitigated through comprehensive searches of the multiple other relevant databases mentioned above, thereby ensuring broad literature coverage. Searches were performed without date restrictions and were limited to publications in English. All databases and sources were searched from inception through 20 August 2025, with the final search executed on that date.

Search strategies were developed around three core concepts: (i) thoracic ultrasound, (ii) pleural effusion, and (iii) artificial intelligence or automated image analysis. For MEDLINE (via PubMed), controlled vocabulary terms (MeSH) were combined with free-text keywords using the Boolean operator OR. For the remaining sources—keyword-based searches were performed due to the absence of formal controlled vocabulary. The three core concepts were linked using AND across all databases and sources. The complete search strings are provided in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material—Full search strategy).

2.7. Study Selection and Screening

After duplicates were automatically removed, both reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts using Rayyan.ai software (Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) [78]. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were obtained and assessed independently by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Standardized screening forms ensured consistency and transparency.

2.8. Data Extraction

Data were extracted independently by at least two reviewers using pre-specified forms, with disagreements resolved through discussion or adjudication by a third reviewer. Extracted information included the following:

- Study characteristics: author, year, country, study design (prospective/retrospective), clinical setting, and single- versus multicenter status.

- Patient characteristics: demographics, clinical features, prevalence and characteristics of pleural effusion (size, complexity), and relevant subgroups (e.g., ICU patients).

- Ultrasound technical specifications: probe type, ultrasound system, and acquisition protocols.

- AI system details: model architecture, input data type (still images, frames, or video), level of automation, pre-processing and data augmentation steps, multi-model or multi-label configurations and explainability and interpretability methods.

- Reference standard applied.

- Diagnostic performance metrics: sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, overall accuracy, and AUC.

- Subgroup or secondary analyses.

Individual participant data (IPD) were not sought; extraction relied solely on information reported in the published studies. Missing or unclear information was addressed by contacting study authors when feasible; otherwise, affected data were excluded.

2.9. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Risk of bias was evaluated using QUADAS-2, covering patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow/timing [79]. Assessments were conducted independently by two reviewers. Potential bias due to missing or unpublished results was considered and discussed qualitatively, acknowledging that selective reporting cannot be fully excluded given the small number of included studies.

2.10. Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of the synthesized evidence was evaluated in accordance with the GRADE framework [80]. This assessment systematically considered potential limitations across five domains: risk of bias, consistency of results, directness of evidence, precision of effect estimates, and the likelihood of publication bias. Outcomes were subsequently categorised as high, moderate, low, or very low certainty, providing a transparent appraisal of confidence in the reported diagnostic performance of AI-assisted TUS for PE detection.

2.11. Data Synthesis

Due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity—including differences in AI models, input data types, reference standards, and reported metrics—formal statistical pooling was not performed. A structured narrative synthesis integrated with four tables was employed to describe diagnostic performance, compare model characteristics, and identify knowledge gaps.

3. Results

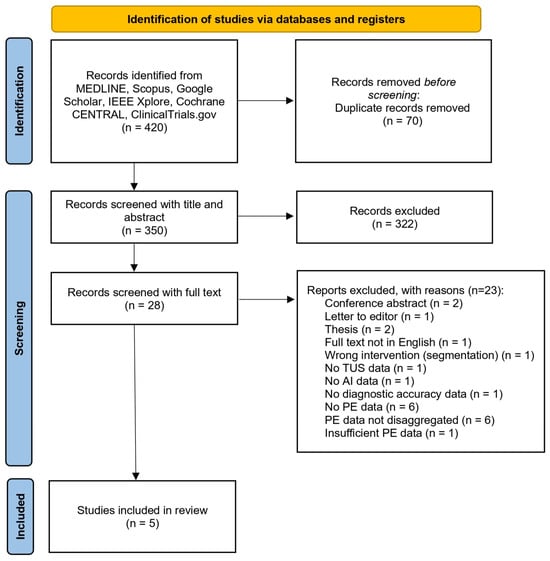

After completion of screening, five studies were identified which met the eligibility criteria, as illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the systematic screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion of studies in the revie.

The included studies demonstrated considerable heterogeneity across several methodological and clinical domains. To address this, the subsequent subsections present a structured synthesis covering study characteristics and settings, ultrasound technical specifications and acquisition protocols, AI system architecture and data processing, validation strategies and dataset partitioning, diagnostic performance metrics, specialised model configurations and clinical applications, performance stratified by effusion characteristics, and statistical significance with comparative analyses. These findings are further synthesised in three summary tables: Table 1 (Study and testing dataset characteristics), Table 2 (Software characteristics), and Table 3 (Diagnostic accuracy measures).

Table 1.

Study and testing dataset characteristics: Summary of the included studies’ design, centre type, reference standard, patient numbers, dataset characteristics, ultrasound equipment, and clinical indications. LUS = lung ultrasound, PACS = Picture Archiving and Communication System, MHz = megahertz, n = number of images/frames/patients, ICU = intensive care unit, US = ultrasound.

Table 2.

Software characteristics. Details of AI classification software and pipelines used in each study, including algorithm type, input data format, pre-processing steps, training dataset, and software implementation. CNN = convolutional neural network, RGB = red-green-blue, DICOM = Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine, AG = attention gate, Reg-STN = Regularised Spatial Transformer Network, U-net = U-shaped convolutional network architecture for segmentation, ResNet = residual neural network, Mish = Mish activation function, Focal loss = loss function for class imbalance, PNG = Portable Network Graphics format, AI = artificial intelligence.

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy measures. Diagnostic performance metrics of AI-based pleural effusion detection across the included studies, including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, AUC, positive predictive value, and additional reported performance indicators. AUC = area under the curve, PPV = positive predictive value, CI = confidence interval, F1-score = harmonic mean of precision and recall, Sens = sensitivity, Spec = specificity, Acc = accuracy, Multi-class = classification with more than two categories, Binary = classification with two categories.

3.1. Study Characteristics and Settings

The included studies were published between 2021 and 2025, with all appearing after 2020 [81,82,83,84,85]. Four adopted a retrospective design, while one was prospective. Across all investigations, interpretation of TUS images by expert clinicians or radiologists served as the reference standard; in addition, one study [84] incorporated chest CT to further validate observer performance. Collectively, the studies enrolled 7565 unique patients across diverse clinical contexts. Sample sizes ranged from 70 patients [81] to 3966 [82], with a median cohort size of 848. Two studies were conducted in China [82,83], one in Australia [81], one in Canada [85], and one in the Republic of Korea [52]. Clinical settings varied substantially, spanning emergency departments, intensive care units, inpatient wards, and general ultrasound departments.

Prevalence of PE varied markedly across studies, ranging from 25.1% [82] to 71.4% [82], with a median of 53.6%. This 2.8-fold variation in disease prevalence has critical implications for interpretation of diagnostic accuracy metrics, particularly positive and negative predictive values.

Three investigations focused exclusively on binary detection of PE [81,83,85], whereas two applied multi-class or multi-label classification approaches that included PE alongside other TUS findings [82,84]. Across all studies, patient populations consisted exclusively of adults (age ≥ 18 years). Mean ages ranged from 59.8 ± 14.9 years (Chen et al. [82]) to 65 ± 17 years (Tsai et al. [81]). No studies included pediatric patients (age < 18 years), representing a significant evidence gap given the increasing utilization of point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric emergency medicine. Detailed study and dataset characteristics are provided in Table 1.

3.2. Ultrasound Technical Specifications and Acquisition Protocols

All conventional ultrasound probe types were represented across the included studies. Linear probes were employed in two studies, convex probes in three, and phased array probes in three, with two studies evaluating AI algorithms across multiple probe types. Ultrasound systems varied considerably, encompassing equipment from multiple manufacturers and imaging settings differed between measurements, including frequency, gain, depth, and focal zone adjustments (see Table 1).

Regarding acquisition protocols, two studies implemented established standardized ultrasonography protocols. Hong et al. applied the BLUE (Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergency) protocol, assessing six anatomical zones, while Chaudhary et al. followed the Blue Protocol, focusing on the costophrenic regions. The remaining studies employed institution-specific scanning approaches, including a six-region lung division [82] and six anatomical zones according to a standardized TUS protocol [81]. Overall, substantial heterogeneity existed in probe selection, ultrasound systems, and image acquisition protocols, reflecting differences in clinical practice, institutional resources, and study objectives.

No study reported implementation of automated image quality assessment (IQA) algorithms; all quality control was performed through manual expert review, with exclusion criteria varying from ‘poor image quality’ (Tsai, Huang) to ‘excessive probe movement’ (Chaudhary) to ‘images obscured by artifacts’ (Hong).

Details regarding ultrasound equipment, probe types, and acquisition protocols are summarised in Table 1.

3.3. AI System Architecture and Data Processing

All five studies employed CNNs as their primary classification approach, although the specific architectures varied substantially. Tsai et al. implemented a Regularised Spatial Transformer Network combined with CNN, Huang et al. compared Attention U-net with standard U-net models, Hong et al. utilised EfficientNet-B0 with transfer learning, Chen et al. developed a ResNet-based model incorporating a Split-Attention mechanism, and Chaudhary et al. created Pleff-Net, a bespoke CNN designed specifically for PE detection.

Among included studies, architectural approaches varied substantially between pure classification and hybrid segmentation-classification tasks. Huang et al. uniquely implemented both segmentation and classification capabilities through their Attention U-net architecture, achieving automated delineation of effusion boundaries (Dice coefficient 0.86, range 0.83–0.90) alongside binary detection. All other studies (Tsai, Chen, Hong, Chaudhary) focused exclusively on classification tasks without pixel-level segmentation output. This distinction is clinically relevant: classification models provide binary/categorical predictions suitable for screening and triage, whereas segmentation models enable quantitative volumetric assessment and procedural guidance for thoracentesis.

Input data formats were heterogeneous across studies: three investigations relied exclusively on still images [82,83,84], one study extracted still images from video sequences [81], and one processed full video clips by decomposing them into individual frames [85]. The total number of images ranged from 1440 [83] to 99,209 [81], with Chaudhary et al. processing over 313,000 frames from video clips.

This variation in data format underpins a key methodological distinction in AI model design: whether models are trained on individual frames or on full video sequences. Three studies (Chen, Huang, Hong) employed frame-based approaches, which benefit from simpler annotation and larger datasets but discard temporal information inherent to respiratory dynamics. Video-based models (Tsai, Chaudhary), in contrast, capture effusion persistence and motion patterns, providing insights into dynamic pleural changes, though they require more labor-intensive frame- or clip-level labeling.

Tsai et al. directly compared these approaches, reporting frame accuracy of 92.4% versus 91.1% for video, with the difference not statistically significant (p = 0.422). Chaudhary et al. developed three clip-level prediction algorithms from frame outputs, illustrating that video models can be optimized for different clinical priorities, such as maximizing sensitivity or specificity. Overall, frame-based models are efficient and practical for large datasets, whereas video-based approaches offer enhanced interpretability of temporal dynamics, a consideration that may be critical in certain diagnostic scenarios.

Pre-processing workflows also displayed considerable variability, encompassing DICOM decompression, format conversion, resizing, and normalization. Data augmentation was employed in three studies [83,84,85] and included horizontal flipping, contrast adjustments, and geometric distortions to enhance model generalisability. Details of the AI architectures, input data formats, and pre-processing pipelines are summarised in Table 2.

3.4. Validation Strategies and Dataset Splitting

The included studies exhibited substantial variability in their dataset partitioning and validation methodologies. Three investigations employed 10-fold cross-validation [81,83,85], while two studies applied conventional train-test splits [82,84]. Notably, Hong et al. implemented both temporal and external validation across multiple institutions, representing the most rigorous and comprehensive validation framework. Training set proportions ranged from 80% [82] to 90% [81,83].

Two studies were particularly distinguished for their validation robustness. Hong et al. evaluated model performance across four separate datasets, including internal, temporal, and two external test sets, thereby providing extensive insight into generalisability. Chaudhary et al. applied patient-level dataset splitting to avoid data leakage between training and testing phases, enhancing the reliability of performance estimates. Further details on dataset sizes, partitioning strategies, and validation approaches are summarised in Table 1.

3.5. Diagnostic Performance Metrics

Diagnostic accuracy exhibited notable variability across studies and model configurations. Sensitivity values ranged from 70.6% (Hong et al., External test 2) to 100% (Chen et al.), with the majority of investigations reporting sensitivities above 90%. Specificity similarly varied, ranging from 67.0% (Chaudhary et al., Trauma model) to 100% (Chen et al.), with most studies achieving values exceeding 85%.

Overall accuracy spanned from 79.0% (Chaudhary et al., Trauma model) to 98.2% (Chen et al., multi-class classification), with four out of five studies reporting accuracies above 89%. The AUC was reported in four studies, ranging from 0.77 (Hong et al., External test 2) to 0.998 (Chen et al.), reflecting generally strong discriminatory capability.

Notably, performance heterogeneity was particularly evident in multi-institutional validations. Hong et al. observed a progressive decline in AUC across validation datasets, decreasing from 0.94 in internal and temporal tests to 0.89 in External test 1, and 0.77 in External test 2. This pattern highlights potential overfitting and limited generalisability when applying models across different clinical environments.

Variation in disease prevalence (25–71%) markedly affects predictive values: high-prevalence settings inflate PPV but reduce NPV, while low-prevalence settings do the opposite.

Comprehensive diagnostic performance metrics for all included studies are summarised in Table 3.

3.6. Specialised Model Configurations and Clinical Applications

Two studies implemented multiple model variants specifically optimised for distinct clinical scenarios. Chaudhary et al. developed three separate models: a general model achieving 90.3% sensitivity and 89.0% specificity, a large-effusion model with 95.5% sensitivity, and a trauma-focused model yielding 98.0% sensitivity and 67.0% specificity. These results demonstrate the adaptability of AI algorithms to differing clinical requirements and effusion characteristics.

Huang et al. directly compared two architectural approaches, reporting that the Attention U-net consistently outperformed the standard U-net across multiple performance metrics, including specificity, precision, accuracy, and F1-score (p < 0.05). Moreover, this study incorporated image segmentation capabilities, achieving Dice coefficients of 0.86 for Attention U-net and 0.82 for standard U-net, highlighting the added value of architectural optimisation in AI-assisted pleural effusion detection.

3.7. Performance by Effusion Characteristics

Three studies conducted subgroup analyses to evaluate diagnostic performance according to effusion characteristics. Chaudhary et al. demonstrated that sensitivity varied with effusion size, achieving 95.1% for large effusions, 92.2% for small effusions, 79.9% for trace effusions, and 77.0% for complex effusions.

Hong et al. assessed performance across different patient populations and reported diminished accuracy in critically ill ICU patients relative to general hospital populations.

3.8. Statistical Significance and Comparative Analyses

Statistical comparisons between models or methodological approaches were reported in three studies. Huang et al. identified statistically significant differences between Attention U-net and standard U-net architectures across multiple performance metrics, with p-values ranging from 0.003 to 0.027, favouring the Attention U-net model. In contrast, Tsai et al. observed no significant difference between video-based and frame-based classification approaches (p = 0.422). Hong et al. reported a significant improvement in inter-reader agreement for binary pleural effusion detection when AI assistance was provided, with κ values increasing from 0.73 to 0.83 (p = 0.01).

Direct comparisons between AI models and human readers are nearly absent. Only Hong et al. assessed AI-assisted human performance, showing modest improvements, but did not evaluate standalone AI versus expert performance. This limits the understanding of whether AI can match or exceed human accuracy, a key requirement for autonomous clinical deployment. Contributing factors include reference standard circularity, resource-intensive reader studies, and potential publication bias. Evidence from related domains [86], suggests AI often approaches average expert performance but may underperform subspecialists, highlighting the need for rigorous comparative evaluation before clinical implementation.

3.9. Explainability and Interpretability: A Critical Gap in Clinical Translation

Explainability implementation in AI-based TUS studies varied considerably, with most studies providing only rudimentary interpretability analyses. Gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) was the predominant method, applied in three studies to generate heatmaps that highlighted image regions influencing model predictions. Tsai et al., by contrast, employed spatial transformer networks, which offered implicit localization capabilities, yet no formal visualization or assessment of attention patterns was provided. Huang et al. relied exclusively on attention mechanisms embedded in the network architecture, but these were neither visualized nor validated, leaving the internal model reasoning largely opaque.

Among the reviewed studies, Chaudhary et al. delivered the most comprehensive explainability assessment. Their approach combined Grad-CAM heatmaps with temporal confidence plotting across video sequences, allowing for the identification of model focus on clinically relevant structures, including anechoic fluid collections, bony structures responsible for the “spine sign” artifact, and pleural line demarcation. Importantly, this temporal analysis enabled the model to distinguish effusions visible during expiration from those compressed during inspiration, reflecting an understanding of respiratory dynamics that is crucial for accurate interpretation of Pes. Despite this sophistication, the study did not include a clinician assessment to verify whether the highlighted regions aligned with expert visual attention patterns.

Chen et al. implemented Grad-CAM within a multi-class ResNet framework, demonstrating class-specific attention patterns for A-lines, B-lines, consolidation, and PE. While these visualizations provided some insight into model reasoning, their clinical validation was limited to visual inspection, without systematic evaluation of whether the attention patterns corresponded to diagnostically meaningful features. Hong et al. briefly mentioned the use of Grad-CAM, but offered minimal analysis of the resulting activation maps. Huang et al. described the theoretical benefits of their attention mechanism, yet did not visualize attention weights or validate their clinical significance. Tsai et al. provided no explainability assessment beyond the implicit localization potential of the spatial transformer.

Critically, none of the studies conducted formal validation of explanation quality, either through clinician assessment or quantitative evaluation of attention map faithfulness. This represents a substantial limitation for clinical translation, as it precludes confirmation that AI models focus on the correct diagnostic features rather than spurious artifacts. The absence of validated explainability impedes regulatory approval, hinders clinician trust, limits error detection, and diminishes potential educational value. Without robust demonstration that model explanations align with expert reasoning and reliably highlight pathologically relevant structures, these AI models remain “black boxes,” unsuitable for autonomous deployment in clinical practice [87].

Details of the explainability approaches and their implementation across studies are summarised in Table 2.

3.10. Risk of Bias

The methodological quality of the included studies was systematically appraised using the QUADAS-2 tool, covering the domains of Patient Selection, Index Test, Reference Standard, and Flow and Timing, as well as overall applicability. All assessments were performed independently by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by discussion or adjudication by a third reviewer to ensure methodological rigour.

All five studies were at high risk of bias for Patient Selection, reflecting predominantly retrospective designs, non-consecutive enrolment, enriched disease prevalence, and systematic exclusion of technically suboptimal scans, which likely inflated performance estimates by omitting challenging real-world cases.

All studies were also rated high risk for Index Test conduct, primarily due to inadequate patient-level dataset partitioning. Except for Chaudhary et al., who explicitly ensured no patient’s images appeared in both training and testing sets, most studies randomized at the image level, allowing multiple images from the same patient in both sets. This AI-specific data leakage enables memorization of patient-specific features rather than generalizable disease patterns, likely inflating performance estimates.

Reference Standard and Flow and Timing were generally rated low risk; however, reliance on expert interpretation of the same images used for model training introduces incorporation bias that may further inflate concordance measures. The combined impact of these biases is likely to result in overly optimistic sensitivity and specificity relative to performance in unselected clinical populations.

Four studies (Tsai, Chen, Huang, Chaudhary) relied solely on expert LUS interpretation as the reference standard, introducing circularity bias, since the same modality served as both index test and comparator. This may artificially inflate diagnostic accuracy compared to an independent gold standard. Only Hong et al. used same-day chest CT for a subset of cases, providing validation against a modality-independent reference. Circularity bias is particularly concerning when AI is trained on expert labels and evaluated against the same experts, as models inherently replicate both correct interpretations and systematic expert errors.

Methodological work in related diagnostic AI domains (e.g., addressing class imbalance, feature selection, and missing data) underscores the importance of balanced datasets and robust validation to mitigate bias and improve generalisability [88]. Overall applicability was judged low risk, indicating alignment between study populations, index tests, and the clinical question addressed in this review.

These evaluations are summarised in Table 4, providing a structured overview of risk of bias and applicability across the included studies.

Table 4.

QUADAS-2 assessment of risk of bias and applicability for included studies. Assessment performed using the QUADAS-2 tool. Patient Selection evaluates risk of bias from study population and enrolment; Index Test evaluates risk of bias in the conduct or interpretation of the AI algorithm; Reference Standard assesses the risk of bias in the comparator (human LUS interpretation ± CT); Flow & Timing evaluates bias related to inclusion of patients and timing of tests. Applicability domains consider the relevance of each domain to the systematic review question. H: High risk; L: Low risk; QUADAS-2: Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies, revised version. Risk of bias was independently evaluated by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer.

3.11. Certainty of Evidence (GRADE)

The certainty of evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of AI-assisted TUS for PE detection was systematically evaluated using the GRADE framework, focusing on sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy.

Risk of Bias: Considering the high risk of bias for patient selection and index test reported in most studies (see Table 4), confidence in the effect estimates is tempered by the predominantly retrospective designs and partially overlapping or non-independent datasets. Reference standards and flow and timing were consistently applied across studies, supporting internal validity.

Inconsistency: Substantial heterogeneity was observed among studies in study design (retrospective vs. prospective), sample size (70–3966 patients), clinical settings (emergency department, intensive care unit, hospital wards, ultrasound departments), imaging protocols, and AI model architectures. This heterogeneity was reflected in the wide range of diagnostic performance metrics reported (sensitivity 70.6–100%, specificity 67–100%, AUC 0.77–0.998).

Indirectness: Populations, index tests, and clinical settings were generally aligned with the review question. However, several models were developed using single-centre cohorts or selected patient subpopulations, which may limit generalisability to broader clinical environments.

Imprecision: Variability in sample sizes and the width of confidence intervals, particularly in multi-institutional external validations, contributed to imprecision of effect estimates.

Publication Bias: Formal statistical assessment was constrained by the small number of included studies. Although selective reporting cannot be entirely excluded, the inclusion of both favourable and less favourable outcomes mitigates, but does not eliminate, this concern.

Overall Certainty: Integrating these domains, the certainty of evidence was rated as moderate for sensitivity and specificity, indicating that AI-assisted TUS generally demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy for pleural effusion detection, while acknowledging that methodological limitations and heterogeneity reduce absolute confidence in the estimates. Certainty regarding broader applicability across diverse clinical settings was considered low-to-moderate.

Overall, while AI-assisted TUS demonstrates generally high diagnostic accuracy for PE detection, methodological limitations and heterogeneity moderate the certainty of the evidence.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

This is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review aimed at studying the accuracy of AI-assisted TUS for the detection of PE.

The evidence from the five included studies (n = 7565) confirms that AI-based automated analysis of TUS can achieve high diagnostic accuracy for PE in curated datasets. Reported sensitivities and specificities were frequently >90% in development and internal testing and reported AUCs ranged approximately 0.77–0.998, demonstrating strong discriminatory capability under favourable conditions. Single-centre development studies produced the most optimistic metrics, while temporal and external validations, most notably Hong et al., revealed performance attenuation on independent datasets. Subgroup analyses consistently show reduced accuracy for trace, small or morphologically complex effusions and for critically ill patients, and specialised model variants illustrate clinically relevant trade-offs between prioritising sensitivity in urgent contexts and preserving specificity in screening or routine care. Collectively these results support the technical feasibility of AI assistance for PE detection using TUS, while emphasising that real-world reliability depends on dataset heterogeneity, robust validation strategies and the intended clinical application.

4.2. Study Limitations and Methodological Considerations

The current evidence base for AI-assisted TUS is characterised by substantial methodological heterogeneity, limiting interpretability and generalisability. Included studies varied widely in input data (still images versus video clips), ultrasound equipment and acquisition protocols (standardised BLUE-based versus local approaches), AI architectures and preprocessing pipelines (ResNet variants, EfficientNet, U-Net/Attention U-Net, bespoke CNNs), and validation strategies. Most relied on internal splits, with only a minority implementing external or patient-level validation to mitigate data leakage. Reference standards were inconsistent, predominantly based on expert interpretation of the same ultrasound images used for model training, with limited use of independent modalities such as chest CT, raising concerns about circularity. Operator-dependent acquisition, heterogeneous handling of low-quality scans, and video-level rather than frame-level labelling further bias performance estimates. Conventional quality assessment tools, including QUADAS-2, have recognised limitations when applied to AI studies.

Given these factors, quantitative pooling of diagnostic performance was deemed methodologically inappropriate. Architectural differences alone can produce substantially divergent results, even within identical datasets, as demonstrated in other diagnostic AI domains [77]. The included studies evaluated five architecturally distinct models across heterogeneous datasets with widely varying prevalence (25–71%), clinical settings, and validation designs, making pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates non-comparable. Variation in disease prevalence further limits generalisability, as predictive values are prevalence-dependent even when sensitivity and specificity remain constant. Models trained in high-prevalence populations may underperform in low-prevalence settings, with external validation drops illustrating this effect. Standardised predictive value calculations at clinically relevant prevalence can aid interpretation, but prospective validation at intended clinical prevalence is essential. Consequently, a structured narrative synthesis was adopted to preserve critical contextual and methodological information that meta-analysis would obscure.

Explainability and clinical interpretability remain critical gaps. Few studies implemented even basic visualisations, and none provided comprehensive analyses aligned with clinical reasoning or regulatory requirements. Approaches ranged from detailed temporal analyses to complete absence of interpretability evaluation, reflecting the early stage of explainable AI (XAI) in this field. Effective deployment requires anatomically accurate feature focus, real-time confidence assessment, failure-mode highlighting, and integration into clinical workflows; current evidence shows these remain largely unvalidated.

The evidence base is further limited by retrospective designs, selection bias, small sample sizes, and scarce external validation. QUADAS-2 assessments indicate high risk of bias in patient selection and index test conduct, with idealised test conditions—such as exclusion of poor-quality images, inadequate patient-level data separation, and threshold optimisation—likely inflating sensitivity and specificity. Reported metrics should therefore be interpreted as potentially overestimated. No study reported patient-centred outcomes, safety endpoints, or health-economic analyses, and direct AI versus human comparisons are lacking. Applicability is constrained by equipment and protocol heterogeneity, and the small number of studies combined with predominantly positive findings suggests potential publication bias.

Finally, a major limitation is the absence of pediatric data, as all included studies enrolled adult populations (≥18 years). This gap is clinically relevant given the growing use of point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric settings, age-related anatomical and etiological differences in pleural effusion, and distinct pediatric decision thresholds for intervention. AI models trained solely on adult populations cannot be assumed to generalise to children without dedicated validation.

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice

Given the current evidence, AI-assisted TUS shows potential as a complementary decision-support tool, but its role as a reliable and effective adjunct to comprehensive clinical judgment is not yet fully confirmed and remains to be established. These systems appear promising in democratizing access to high-quality ultrasound interpretation, particularly in emergency or resource-limited settings, and as part of telemedicine or teleconsultation workflows, by supporting less-experienced operators and standardizing interpretation. Implementation requires institution-level validation against local devices, probe types and patient mixes, and must include transparent presentation of model confidence and localisation (for example segmentation overlays) together with clear escalation pathways for equivocal results. Ultrasound differs from other forms of automated imaging in that the process of image acquisition itself directly influences diagnostic outcomes, and imperfect scans are unavoidable, especially in fast-paced or high-pressure clinical settings. Incorporating software solutions that assist operators during acquisition and evaluate scan quality in real time could allow immediate identification and exclusion of substandard images, enhance performance for less-experienced users, and increase the overall reliability of AI-supported interpretations. Integration with conventional radiological pathways and clinical assessment remains essential: AI outputs should always be interpreted in the context of clinical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and integrated with imaging such as TUS, chest radiography, or CT, as part of a comprehensive, multimodal clinical assessment. Practical deployment further demands governance for responsibility of final interpretation, continuous performance monitoring and procedures for handling inadequate scans; embedding an automated scan-quality check within the pipeline could reduce false reassurance from poor inputs. For specific use cases, models should be tailored to context-specific performance priorities (for example, prioritizing high sensitivity for PE detection in critically ill ICU patients, or emphasizing robustness to operator variability in emergency or remote settings where inexperienced operators perform scans).

4.4. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Advancement toward safe and generalisable clinical tools requires prospective, multicentre studies with consecutive enrolment across diverse healthcare settings and device vendors, generating realistic, prevalence-dependent performance estimates. Datasets must incorporate technically challenging cases, such as obesity and subcutaneous emphysema, while dedicated paediatric cohorts are essential due to anatomical differences, distinct disease aetiologies, and varying clinical decision thresholds. AI models intended for broad clinical use should therefore be trained on mixed-age datasets or explicitly developed and validated in paediatric populations before deployment in such settings, ensuring generalisability and equity.

Rigorous external and temporal validation should become standard practice, accompanied by transparent reporting of calibration, decision-curve analyses, and uncertainty intervals. Comparative studies should include direct AI-versus-human evaluation, using identical test sets and gold-standard references to determine non-inferiority or complementary error patterns for human–AI synergy.

Clinically validated explainability frameworks are critical and should combine technical visualisation (e.g., Grad-CAM or attention maps), multi-reader assessment, and real-time guidance to highlight diagnostically relevant features, quantify uncertainty, and support confidence-calibrated predictions. These frameworks should incorporate quantitative evaluation of explanations, including faithfulness scores derived from perturbation analysis, pointing game accuracy against expert annotations, multi-reader Likert-scale assessment of explanation utility, and counterfactual testing to ensure that explanations faithfully reflect model reasoning rather than post hoc rationalization. Such explainability measures are essential not only to enhance interpretability and clinician trust, but also to identify model limitations and error patterns, particularly for less-experienced operators.

Future methodological work should further address operator dependence through integrated scan-quality assessment and real-time acquisition support, and explore emerging model architectures to enhance robustness and generalisability. Cost-effectiveness analyses and pragmatic randomized trials are necessary to evaluate AI’s impact on patient outcomes, procedural safety, and resource utilisation. Finally, human-factors research, post-market surveillance, and adherence to AI-specific reporting and validation standards will be crucial to ensure transparent, reproducible, and safe translation of AI tools into routine clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

AI-assisted analysis of TUS for the detection of PE represents a rapidly and exponentially evolving domain with substantial translational potential. Current evidence indicates that these algorithms appear capable of achieving diagnostic performance approaching that of expert operators, thereby enhancing reproducibility and standardisation of sonographic interpretation.

Nevertheless, such tools must always be considered adjunctive rather than substitutive, and cannot replace comprehensive clinical assessment, which remains grounded in detailed history-taking, physical examination, symptom evaluation, laboratory testing, and holistic patient evaluation. These methodologies are inherently complementary and should be integrated with conventional radiological imaging and comprehensive clinical assessment to ensure a multidimensional diagnostic approach.

Their strategic implementation may be particularly beneficial in settings with limited specialist expertise, especially in the emergency departments and intensive care units of rural or remote healthcare facilities, as well as in low- and middle-income countries. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests potential utility even in tertiary care or high-volume academic centres, where AI-assisted interpretation may support workflow efficiency, rapid decision-making, and standardisation of sonographic evaluation.

In all these contexts, integration with telemedicine platforms or remote expert consultation may further augment diagnostic reliability and clinical decision-making. However, current evidence also highlights a gap between technical AI performance and clinical interpretability; robust explainability frameworks, including clinical validation and real-time interpretability interfaces, will be crucial to ensure trust, transparency, and safe deployment.

Future research should prioritise prospective, multicentre studies with rigorous external validation across heterogeneous populations and healthcare environments, alongside systematic evaluation of clinically meaningful outcomes. With continued methodological refinement, adherence to standardised reporting frameworks, and careful integration into clinical workflows, AI-assisted TUS has the potential to serve as a high-value adjunct to conventional imaging and comprehensive clinical evaluation, optimising diagnostic precision, efficiency, and equity in respiratory care.

Beyond local implementation, its development and uptake may also contribute to improving respiratory health in diverse global settings, where disparities in access and resources remain major challenges.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics16010147/s1, Supplementary Material—Full search strategy; Supplementary Table S1—PRISMA 2020 Checklist; Supplementary Material—COI Diagnostics.

Author Contributions

G.M.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; L.G.: Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; M.G.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; M.S.: Conceptualization, Visualization, Data Curation, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; F.B.: Supervision, Methodology, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; S.C.F.: Supervision, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; J.C.: Supervision, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; C.S.: Supervision, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; G.G.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; F.P.: Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing; L.C.: Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing; M.M.: Supervision, Methodology, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AG | Attention gate |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| B0 | Baseline model variant of EfficientNet |

| B-lines | Vertical artefacts in lung ultrasound |

| BLUE | Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergency |

| CI | Confidence interval (defined in tables, standard but explicitly included) |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| DL | Deep learning |

| F1-score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations |

| ICMJE | International Committee of Medical Journal Editors |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IPD | Individual participant data |

| LUS | Lung ultrasound |

| ML | Machine learning |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| PE | Pleural effusion |

| Pleff-Net | PLeural EFFusion neural NETwork |

| PNG | Portable Network Graphics format |

| POCUS | Point-of-care ultrasound |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 |

| Reg-STN | Regularised Spatial Transformer Network |

| ResNet | Residual neural network |

| RGB | Red–green–blue colour model |

| TUS | Thoracic ultrasound |

| U-net | U-shaped convolutional network architecture |

References

- Feller-Kopman, D.; Light, R. Pleural Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.E.; Rahman, N.M.; Maskell, N.A.; Bibby, A.C.; Blyth, K.G.; Corcoran, J.P.; Edey, A.; Evison, M.; de Fonseka, D.; Hallifax, R.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023, 78, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, A.; Bhatnagar, M.; Rahman, N.M. Diagnosis and management of pleural infection. Breathe 2024, 19, 230146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, L.; Toubes, M.E.; José, M.E.S.; Suárez-Antelo, J.; Golpe, A.; Valdés, L. Advances in pleural effusion diagnostics. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 14, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, R.W. Pleural Diseases, 5th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7817-6957-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bedawi, E.O.; Ricciardi, S.; Hassan, M.; Gooseman, M.R.; Asciak, R.; Castro-Añón, O.; Armbruster, K.; Bonifazi, M.; Poole, S.; Harris, E.K.; et al. ERS/ESTS statement on the management of pleural infection in adults. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2201062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller-Kopman, D.J.; Reddy, C.B.; DeCamp, M.M.; Diekemper, R.L.; Gould, M.K.; Henry, T.; Iyer, N.P.; Lee, Y.C.G.; Lewis, S.Z.; Maskell, N.A.; et al. Management of Malignant Pleural Effusions. An Official ATS/STS/STR Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Ost, D.E. Malignant pleural disease: A pragmatic guide to diagnosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2022, 28, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummadi, S.R.; Stoller, J.K.; Lopez, R.; Kailasam, K.; Gillespie, C.T.; Hahn, P.Y. Epidemiology of Adult Pleural Disease in the United States. Chest 2021, 160, 1534–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodtger, U.; Hallifax, R.J. Epidemiology: Why is pleural disease becoming more common? In Pleural Disease, 1st ed.; Maskell, N.A., Laursen, C.B., Lee, Y.C.G., Rahman, N.M., Eds.; European Respiratory Society: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: http://publications.ersnet.org/lookup/doi/10.1183/2312508X.10022819 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Vakil, E.; Taghizadeh, N.; Tremblay, A. The Global Burden of Pleural Diseases. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 44, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallifax, R.J.; Talwar, A.; Wrightson, J.M.; Edey, A.; Gleeson, F.V. State-of-the-art: Radiological investigation of pleural disease. Respir. Med. 2017, 124, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, E.; Gargani, L.; Bignami, E.G.; Barbariol, F.; Marra, A.; Forfori, F.; Vetrugno, L. Thoracic ultrasound for pleural effusion in the intensive care unit: A narrative review from diagnosis to treatment. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, A.; Hu, K.; Feller-Kopman, D.; Judson, M.A. Pleural fluid analysis: Maximizing diagnostic yield in the pleural effusion evaluation. Chest 2025, 168, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayen, S. Malignant pleural effusion: Presentation, diagnosis, and management. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 1188–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, J.P.; Hallifax, R.J.; Mercer, R.M.; Yousuf, A.; Asciak, R.; Hassan, M.; Piotrowska, H.E.; Psallidas, I.; Rahman, N.M. Thoracic ultrasound as an early predictor of pleurodesis success in malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2018, 154, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, T.; Parmar, M.S. (F)utility of computed tomography of the chest in the presence of pleural effusion. Pleura Peritoneum 2017, 2, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, K.; Li, W.; Liu, D. Chest ultrasound is better than CT in identifying septated effusion of patients with pleural disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, K.; Pelluru, S.; Mishra, D.; Pahuja, N.; Mohapatra, A.R.; Sharma, J.; Thapa, O.B.; Multani, M. Comparison of efficacy of lung ultrasound and chest X-ray in diagnosing pulmonary edema and pleural effusion in ICU patients: A single centre, prospective, observational study. Open J. Anesthesiol. 2024, 14, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmahos, G.C.; Demetriades, D.; Chan, L.; Tatevossian, R.; Cornwell, E.E.; Yassa, N.; Murray, J.A.; Asensio, J.A.; Berne, T.V. Predicting the need for thoracoscopic evacuation of residual traumatic hemothorax: Chest radiograph is insufficient. J. Trauma 1999, 46, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, H.A.; Albaroudi, B.; Shaban, E.E.; Shaban, A.; Elgassim, M.; Almarri, N.D.; Basharat, K.; Azad, A.M. Advancement in pleura effusion diagnosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of point-of-care ultrasound versus radiographic thoracic imaging. Ultrasound J. 2024, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.M.; Ullah, K.; Patail, H.; Ahmad, S. Ultrasound for pleural disease. Beyond a pocket of pleural fluid. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Mercer, R.M.; Rahman, N.M. Thoracic ultrasound in the modern management of pleural disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 190136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, G.; SzaboSzabo, G.; Koukaki, E.; De Wever, W.; Grabczak, E.M.; Juul, A.D. ERS International Congress 2025: Highlights from the Clinical Techniques, Imaging and Endoscopy Assembly. ERJ Open Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marchi, G.; Cucchiara, F.; Gregori, A.; Biondi, G.; Guglielmi, G.; Serradori, M.; Gherardi, M.; Gabbrielli, L.; Pistelli, F.; Carrozzi, L. Thoracic Ultrasound for Pre-Procedural Dynamic Assessment of Non-Expandable Lung: A Non-Invasive, Real-Time and Multifaceted Diagnostic Tool. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colares, P.d.F.B.; Mafort, T.T.; Sanches, F.M.; Monnerat, L.B.; Menegozzo, C.A.M.; Mariani, A.W. Thoracic ultrasound: A review of the state-of-the-art. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2024, 50, e20230395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, G.; Cinquini, S.; Tannura, F.; Guglielmi, G.; Gelli, R.; Pantano, L.; Cenerini, G.; Wandael, V.; Vivaldi, B.; Coltelli, N.; et al. Intercostal Artery Screening with Color Doppler Thoracic Ultrasound in Pleural Procedures: A Potential Yet Underexplored Imaging Modality for Minimizing Iatrogenic Bleeding Risk in Interventional Pulmonology. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, G. Exploring pleural effusion characterization with quantitative thoracic ultrasound imaging: A viewpoint on the investigational role of pixel-based echogenicity analysis in transudate and exudate differentiation. Breathe 2025, 21, 250282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, C.B.; Clive, A.; Hallifax, R.; Pietersen, P.I.; Asciak, R.; Davidsen, J.R.; Bhatnagar, R.; Bedawi, E.O.; Jacobsen, N.; Coleman, C.; et al. European Respiratory Society statement on thoracic ultrasound. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2001519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaswad, M.; Abady, E.M.A.; Darawish, S.M.; Barabrah, A.M.; Okesanya, O.J.; Zehra, S.A.; Aponte, Y.; Alkubati, S.A.; Alsabri, M. Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Pediatric Emergency Care in Low-Resource Settings: A Literature Review of Applications, Successes, and Future Directions. Curr. Treat. Options Pediatr. 2025, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, F.W.; Bonyan, F.A.; Al-Rubaye, S.A.M. Comparing Point-Of-Care Ultrasound Versus CT scan for Pleural Effusion Detection in The Emergency Department of Baghdad Teaching Hospital. J. Port Sci. Res. 2024, 7, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, F.M.; Bonfichi, A.; Esposito, C.; Zanza, C.; Bellou, A.; Sfondrini, D.; Voza, A.; Piccioni, A.; Di Sabatino, A.; Savioli, G. Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma in the Emergency Department: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, P.; Campo, I.; Derchi, L.E.; Bertolotto, M. Emergency Ultrasound in Trauma Patients: Beware of Pitfalls and Artifacts! J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 60, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böck, U.; Seibel, A. Lung ultrasound in cardiological intensive care and emergency medicine (part 2): Pneumothorax, ventilation disorders and the BLUE protocol; Lungensonographie in der kardiologischen Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin (Teil 2): Pneumothorax, Belüftungsstörungen und das BLUE-Protokoll. Kardiologie 2023, 17, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.A. Lung Ultrasound in the Critically Ill. J. Med. Ultrasound 2009, 17, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D. Novel approaches to ultrasonography of the lung and pleural space: Where are we now? Breathe 2017, 13, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.A. BLUE-Protocol and FALLS-Protocol. Chest 2015, 147, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, C.B.; Via, G.; Basille, D.; Bhatnagar, R.; Jenssen, C.; Konge, L.; Mongodi, S.; Pietersen, P.I.; Prosch, H.; Rahman, N.M.; et al. Thoracic Ultrasound—EFSUMB Training Recommendations, a position paper. Ultraschall Med. 2025, 46, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietersen, P.I.; Bhatnagar, R.; Rahman, N.M.; Maskell, N.; Wrightson, J.M.; Annema, J.; Crombag, L.; Farr, A.; Tabin, N.; Slavicky, M.; et al. Evidence-based training and certification: The ERS thoracic ultrasound training programme. Breathe 2023, 19, 230053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajwa, J.; Munir, U.; Nori, A.; Williams, B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Transforming the practice of medicine. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, e188–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhejaily, A.-M.G. Artificial intelligence in healthcare (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2025, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causio, F.A.; DE Angelis, L.; Diedenhofen, G.; Talio, A.; Baglivo, F. Perspectives on AI use in medicine: Views of the Italian Society of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2024, 65, E285–E289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, G.; Gambini, G.; Guglielmi, G.; Pistelli, F.; Carrozzi, L. Valutazione comparativa di modelli linguistici di grandi dimensioni per il supporto all’educazione sanitaria del paziente con BPCO: Uno studio pneumologico internazionale delle risposte generate da ChatGPT-4, Claude 3.5 Sonnet e Gemini 1.5 Advanced. Recent. Progress. Med. 2025, 116, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Obaido, G.; Jere, N.; Mienye, E.; Aruleba, K.; Emmanuel, I.D.; Ogbuokiri, B. A survey of explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: Concepts, applications, and challenges. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2024, 51, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abuhmed, T.; El-Sappagh, S.; Muhammad, K.; Alonso-Moral, J.M.; Confalonieri, R.; Guidotti, R.; Del Ser, J.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Herrera, F. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Anazi, S.; Al-Omari, A.; Alanazi, S.; Marar, A.; Asad, M.; Alawaji, F.; Alwateid, S. Artificial intelligence in respiratory care: Current scenario and future perspective. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2024, 19, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cellina, M.; Cacioppa, L.M.; Cè, M.; Chiarpenello, V.; Costa, M.; Vincenzo, Z.; Pais, D.; Bausano, M.V.; Rossini, N.; Bruno, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Lung Cancer Screening: The Future Is Now. Cancers 2023, 15, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, T.; Yasufuku, K. Artificial intelligence in interventional pulmonology. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2024, 30, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, G. Artificial Intelligence in Interventional Pulmonology: Promise Versus Proof. Respiration 2025, 1–4, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, D.; Adejumo, I.; Hansen, K.; Poberezhets, V.; Slabaugh, G.; Hui, C.Y. Artificial intelligence in respiratory care: Perspectives on critical opportunities and challenges. Breathe 2024, 20, 230189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, G.; Fanni, S.C.; Mercier, M.; Cefalo, J.; Salerni, C.; Ferioli, M.; Candoli, P.; Romei, C.; Gori, L.; Cucchiara, F.; et al. Artificial intelligence and radiomics in drug-induced interstitial lung disease. ERJ Open Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.; Van Heumen, S.; Funke, F.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Serino, M.; Frille, A.; Marchi, G.; Koukaki, E.; Hardavella, G.; Catarata, M.J. The role of interventional pulmonology in management of pulmonary nodules during lung cancer screening. Breathe 2025, 21, 240256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorini, G.; Puliti, D.; Picozzi, G.; Giovannoli, J.; Veronesi, G.; Pistelli, F.; Senore, C.; Tessa, C.; Cavigli, E.; Bisanzi, S.; et al. CCM-ITALUNG2 pilot on lung cancer screening in Italy: Recruitment, integration with smoking cessation and baseline results. Radiol. Medica 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharqi, M.; Edelman, E.R. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular Imaging and Interventional Cardiology: Emerging Trends and Clinical Implications. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2025, 4, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Föllmer, B.; Williams, M.C.; Dey, D.; Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Maurovich-Horvat, P.; Volleberg, R.H.J.A.; Rueckert, D.; Schnabel, J.A.; Newby, D.E.; Dweck, M.R.; et al. Roadmap on the use of artificial intelligence for imaging of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque in coronary arteries. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, G.; Mercier, M.; Cefalo, J.; Salerni, C.; Ferioli, M.; Candoli, P.; Gori, L.; Cucchiara, F.; Cenerini, G.; Guglielmi, G.; et al. Advanced imaging techniques and artificial intelligence in pleural diseases: A narrative review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 240263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addala, D.N.; Rahman, N.M. Man versus Machine in Pleural Diagnostics: Does Artificial Intelligence Provide the Solution? Ann. ATS 2024, 21, 202–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloescu, C.; Bailitz, J.; Cheema, B.; Agarwala, R.; Jankowski, M.; Eke, O.; Liu, R.; Nomura, J.; Stolz, L.; Gargani, L.; et al. Artificial Intelligence–Guided Lung Ultrasound by Nonexperts. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccatonda, A.; Piscaglia, F. New perspectives on the use of artificial intelligence in the ultrasound evaluation of lung diseases. J. Ultrasound 2024, 27, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, J.J.; Munoz, M.; Genovés, V.; Herraiz, J.L.; Ortega, I.; Belarra, A.; González, R.; Sánchez, D.; Giacchetta, R.C.; Trueba-Vicente, Á. Artificial Intelligence and Democratization of the Use of Lung Ultrasound in COVID-19: On the Feasibility of Automatic Calculation of Lung Ultrasound Score. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, G. The road less travelled: Thoracic ultrasound, advanced imaging, and artificial intelligence for early diagnosis of non-expandable lung in malignant pleural effusion. Breathe 2025, 21, 250179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Liteplo, A.; Duggan, N.; Hutchinson, A.B.; Shokoohi, H. Artificial intelligence in lung ultrasound. Curr. Pulmonol. Rep. 2024, 13, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhong, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, B. Application of Deep Learning-Based Artificial Intelligence Model in Lung Ultrasound for Pediatric Lobar Pneumonia. researchsquare.com. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-6410448/latest (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Nekoui, M.; Bolouri, S.S.; Forouzandeh, A.; Dehghan, M.; Zonoobi, D.; Jaremko, J.L.; Buchanan, B.; Nagdev, A.; Kapur, J. Enhancing lung Ultrasound Diagnostics: A clinical study on an Artificial Intelligence Tool for the detection and quantification of A-Lines and B-Lines. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Maranna, S.; Watson, C.; Parange, N. A scoping review on the integration of artificial intelligence in point-of-care ultrasound: Current clinical applications. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2025, 92, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Point of Care Ultrasound Lung Artificial Intelligence (AI) Validation Data Collection Study. 2021. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04891705 (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Resühr, D.; Garnett, C. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of AI in Medical Imaging. EMJ Radiol. 2025, 6, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gichoya, J.W.; Katabi, D.; Ghassemi, M. The limits of fair medical imaging AI in real-world generalization. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2838–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennab, M.; Mcheick, H. Enhancing interpretability and accuracy of AI models in healthcare: A comprehensive review on challenges and future directions. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11, 1444763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abgrall, G.; Holder, A.L.; Chelly Dagdia, Z.; Zeitouni, K.; Monnet, X. Should AI models be explainable to clinicians? Crit. Care 2024, 28, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Jeong, W.; Lee, S.W. Explainable AI in Clinical Decision Support Systems: A Meta-Analysis of Methods, Applications, and Usability Challenges. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Alizadehsani, R.; Cifci, M.A.; Kausar, S.; Rehman, R.; Mahanta, P.; Bora, P.K.; Almasri, A.; Alkhawaldeh, R.S.; Hussain, S.; et al. A review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in healthcare. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vani, M.S.; Sudhakar, R.V.; Mahendar, A.; Ledalla, S.; Radha, M.; Sunitha, M. Personalized health monitoring using explainable AI: Bridging trust in predictive healthcare. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R.K.; Jolly, L.; Dakua, S.P. Advancing explainable AI in healthcare: Necessity, progress, and future directions. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2025, 119, 108599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, J.H. PROSPERO: An International Register of Systematic Review Protocols. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2019, 38, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayturan, K.; Sarıkamış, B.; Akşahin, M.F.; Kutbay, U. SPHERE: Benchmarking YOLO vs. CNN on a Novel Dataset for High-Accuracy Solar Panel Defect Detection in Renewable Energy Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, M. Introduction to the GRADE tool for rating certainty in evidence and recommendations. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; van der Burgt, J.; Vukovic, D.; Kaur, N.; Demi, L.; Canty, D.; Wang, A.; Royse, A.; Royse, C.; Haji, K.; et al. Automatic deep learning-based pleural effusion classification in lung ultrasound images for respiratory pathology diagnosis. Phys. Med. 2021, 83, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shen, M.; Hou, S.; Duan, X.; Yang, M.; Cao, Y.; Qin, W.; Niu, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent interpretation of four lung ultrasonographic features with split attention based deep learning model. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 81, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lin, Y.; Cao, P.; Zou, X.; Qin, Q.; Lin, Z.; Liang, F.; Li, Z. Automated detection and segmentation of pleural effusion on ultrasound images using an Attention U-net. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2024, 25, e14231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Choi, H.; Hong, W.; Kim, Y.; Kim, T.J.; Choi, J.; Ko, S.-B.; Park, C.M. Deep-learning model accurately classifies multi-label lung ultrasound findings, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and inter-reader agreement. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]