Abstract

Background: Pneumonia remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality among critically ill children. Lung ultrasound has emerged as a promising bedside diagnostic tool. Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis across PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Scopus, World Health Organization Libraries, Epistemonikos, and MedRxiv was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasound for pneumonia in paediatric patients. Publication bias was evaluated using the generalised Egger’s test. Diagnostic performance metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve were pooled using a bivariate random-effects model. Results: Thirty studies comprising a total of 4356 children were included. The studies were of high methodological quality, with minimal heterogeneity. Lung ultrasound pooled sensitivity was 91% (95% CI: 87–94%), and specificity was 90% (95% CI: 83–94%). The ROC curve was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.90–0.95), indicating excellent diagnostic performance. Conclusions: LUS is a reliable and accurate imaging modality for diagnosing pneumonia in critically ill children. The findings support its use as a first-line diagnostic tool in emergency and intensive care settings.

1. Introduction

Pneumonia is the leading infectious cause of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide [1,2], responsible for over 740,000 deaths annually in those under five years of age [3]. Despite its high incidence and potential for serious complications, timely and accurate diagnosis remains challenging, often requiring multiple complementary tests. This highlights the pressing need for rapid, reliable, and accessible diagnostic methods.

In paediatric populations, pneumonia is a common cause of admission to intensive care units (PICU) [4,5], particularly in high-income countries, where it contributes significantly to healthcare costs and widespread antibiotic use [6]. However, no universally accepted diagnostic reference standard currently exists. Clinical presentations vary with age and causative pathogen, further complicating its diagnosis [7,8,9].

Chest X-ray (CXR) is commonly used in clinical practice, but has well-documented limitations in detecting pneumonia, distinguishing between viral and bacterial aetiologies, and predicting clinical outcomes [10,11,12,13,14]. Computed tomography (CT), while more accurate, is not routinely used due to concerns about radiation over exposure [15], need for patient cooperation or sedation, and higher cost constraints—issues particularly relevant in resource-limited settings [1,16].

Lung ultrasound (LUS) has emerged as a promising alternative: it is safe, portable, non-invasive, cost-effective, and increasingly used even in primary care for the evaluation of multiple pulmonary conditions. It offers real-time bedside imaging and avoids many of the drawbacks associated with CXR and CT. However, uncertainty remains regarding its diagnostic accuracy, particularly in critically ill paediatric patients [17,18].

Given these gaps, the present systematic review and meta-analysis aims to comprehensively synthesise the current evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of LUS for pneumonia in this high-risk population. The objective is to assess its clinical utility in emergency and intensive care settings, where timely and precise diagnosis is essential.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Protocol Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines. The study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (Registration Number: CRD42019135338).

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across several databases, including PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Scopus, World Health Organization Libraries, Epistemonikos, and MedRxiv, covering all studies published until December 2022.

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a hospital expert librarian to maximise sensitivity and relevance. Search terms included combination of keywords such as paediatrics (“age < 21 years”), clinically suspected pneumonia (“pneumonia”), and imaging tests for diagnosing clinically suspected pneumonia (“ultrasound,” “sonography,” “ultrasonography,” “radiography,” “chest film,” “chest radiograph,” “computerized tomography,” or “image test”). Reference lists of included studies, related reviews, and articles suggested by PubMed and EMBASE were manually screened to identify additional relevant publications.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were selected according to predefined eligibility criteria based on PICO (Population, Interventions, Comparator, and Outcome). Eligible studies included paediatric patients from 0 to 21 years of age with clinical suspicion or confirmed diagnosis of pneumonia, evaluated in emergency departments (acutely ill patients) or critical care settings (critically ill patients requiring intensive care support). Studies focusing only on neonatal or adult populations were excluded to maintain homogeneity within the paediatric cohort.

The intervention of interest was LUS performed for pneumonia diagnosis. Eligible studies were required to compare LUS findings against a reference standard, which could include clinical evolution, CXR, CT or a composite diagnostic criterion based on clinical presentation, imaging, laboratory markers, and/or microbiological findings [19].

Studies were included only if they reported sufficient data to reconstruct 2 × 2 contingency tables, enabling the calculation of diagnostic performance metrics.

The methodological quality and risk of bias of the diagnostic accuracy studies included in this review were assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool [20] (Whiting et al., 2011). QUADAS-2 evaluates four key domains: Patient Selection, Index Test, Reference Standard, and Flow and Timing. Each domain was assessed for risk of bias (classified as low, high, or unclear). The assessment was based on signalling questions provided by the QUADAS-2 framework, which guides reviewers in making judgments about potential sources of bias and applicability concerns. The results are summarised in frequency tables and visualised using bar plots to illustrate the distribution of risk levels across domains. Only original, peer-reviewed studies published in English or Spanish were considered.

Studies were excluded if they lacked a clear diagnostic standard, used inappropriate or poorly described methodologies (e.g., absence of randomization or blinding where relevant), or failed to report outcomes in a manner compatible with meta-analytic synthesis. Review articles, meta-analyses, editorials, letters, case reports, and conference abstracts were also excluded.

Studies were classified as high risk for bias if they lacked a detailed description of randomization. Incorrect randomization methods, such as coin tosses, were exclusionary. Only articles in English and Spanish were considered.

The primary outcome was the diagnostic accuracy of LUS in identifying pneumonia. Accuracy was assessed through sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios.

2.4. Study Selection

All identified records were imported into Rayyan QCRI [21], and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, followed by full-text review. Each article was evaluated independently by four reviewers (CGP, SBP, MBG, IJG), with disagreements resolved through discussion and consensus. A PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the selection process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

2.5. Data Extraction and Management

Data were extracted independently by four reviewers (CGP, SBP, MBG, and IJG) using a standardised form that included the following items:

- Study characteristics: Author, year, country, setting, sample size, design.

- Study design: Randomised, blinded, prospective/retrospective.

- Participant characteristics: Age range, sex, clinical setting.

- Diagnostic method details: LUS equipment and protocols, probe type, scanning zones, operator expertise, blinding procedures, follow-up.

- Outcome data: True positives, false positives, false negatives, true negatives, and statistical measures of diagnostic accuracy.

- Adverse events and other relevant findings.

Where necessary, corresponding authors were contacted to obtain missing data.

2.6. Risk of Publication Bias Assessment

Publication bias was evaluated using the generalised Egger’s test for diagnostic accuracy studies, as proposed by Hong (2020) [22], applied jointly to sensitivity and specificity estimates. The test was implemented through a parametric bootstrap approach to improve robustness. In addition, visual inspection of funnel plots for sensitivity and specificity was performed to assess asymmetry.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the meta v8.2.1 [23], metafor 4.8.0 (2010) [24], and mada 0.5.12, R v4.5.0 packages. Diagnostic accuracy was assessed using sensitivities, specificities, likelihood ratios, and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). A random-effects model was applied to calculate pooled effect estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals using the DerSimonian–Laird method [25]. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated using Cochran’s Q statistic [26], Higgins’ I2 [27], and prediction intervals for pooled effects [28]. A bivariate model approach [29] was employed to jointly model sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity and specificity estimates and their confidence intervals (continuity-corrected estimates and Wald intervals) were computed using the madad function of the R library mada [30], while the pooled estimates are the previously presented estimates from the bivariate model (Reitsma function of the same R library).

The summary estimates for both log-Diagnostic odds ratios and the likelihood ratios are those from the bivariate model presented previously generated through the sampling procedure proposed in Zwinderman and Bossuyt [31]. The individual study estimates and confidence intervals were obtained in the same manner as for the sensitivity and specificity. The weights displayed are derived from a univariate random effect size estimation of the diagnostic odds ratio, as in DerSimonian and Laird [25].

Differences in diagnostic performance were thoroughly examined using Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic (SROC) curves. The differences in diagnostic performance were tested using bootstrap technique applying the summary AUC comparison test for Summary ROC curves, as proposed by Noma, Matsushima, and Ishii [32], and implemented in the R library dmetatools [32]. The Summary ROC curve approach developed by Rutter and Gatsonis [33] was used to compare the AUCs of the bivariate models.

Forest plots of the sensitivity and specificity, log diagnostic odds ratios, and likelihood ratios for both LUS and comparators are provided for the articles included on the bivariate analysis. The forest plots were generated using the R library forestploter [34].

Dealing with missing data: If there were missing data, we attempted to contact the corresponding authors of included studies for any necessary data by e-mail. However, if the missing data could not be obtained, the study was excluded from the analysis.

Subgroup analysis: If there was significant heterogeneity between studies, a subgroup analysis was carried out to explore the causes of heterogeneity.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The initial database search yielded 838 records (Figure 1). After removal of 72 duplicates, 766 titles and abstracts were screened, leaving 116 articles for full-text review. Following the exclusion of 55 articles (14 reviews/meta-analyses, 5 adult-only studies, 12 for methodological or reporting reasons, and others), 30 studies met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated using the QUADAS-2 tool. The main source of potential bias was patient selection. Articles were assessed by at least two independent reviewers. A third evaluator reassessed the articles when there were discrepancies. Four case-only studies were excluded from the pooled bivariate analysis due to incompatibility with the model.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

The 30 eligible studies, published between 2008 and 2022, involved a total of 4356 paediatric patients. The median sample size was 100 (IQR 69–154), with participants ranging in age from 0 to 21 years. Most studies (63%) were prospective cohorts, and 60% were performed in emergency department settings. Geographically, the studies were conducted in Italy (n = 8), the United States (n = 4), Spain (n = 1), China (n = 1), and other countries.

Regarding comparators, CXR was the most frequent reference standard in 22 (73%) studies. Regarding LUS features, pulmonary consolidation was the most assessed finding in 29 (96.6%) studies. Regarding quality measures, 24 studies (80%) reported blinding of operators to comparator outcomes.

Full details of demographics, imaging protocols, and diagnostic outcomes are presented in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

Table 2.

Description of LUS technique: equipment, operators, and results.

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of LUS for pneumonia.

3.3. Pooled Diagnostic Accuracy

This meta-analysis demonstrated that LUS had excellent diagnostic performance for LUS (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Pooled estimates at a 95% confidence interval, including sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratio (LR), and the log-diagnostic odds ratio (lnDOR). Heterogeneity assessed using Higgins’ I2 statistic. LUS: lung ultrasound.

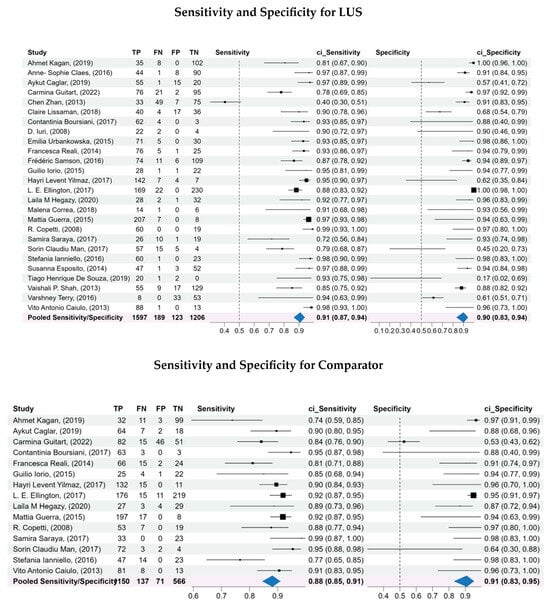

The pooled sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp) for LUS were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.87–0.94) and 0.90 (95% CI: 0.83–0.94), respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) for LUS resulted of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.90–0.95) indicating strong overall performance (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of diagnostic performance between LUS and the comparator test using summary ROC curves. Each triangle represents the accuracy of each article. Ellipses represent confidence regions around the average sensitivity and specificity estimates for each test. The overlap between ellipses suggests that the diagnostic accuracy of the two tests may be similar.

Comparators showed an Se of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85–0.91) and Sp of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.83–0.95). Heterogeneity was low for both groups (LUS: I2 = 8.5%; CXR: I2 = 3.5%), indicating a high degree of homogeneity among the included studies.

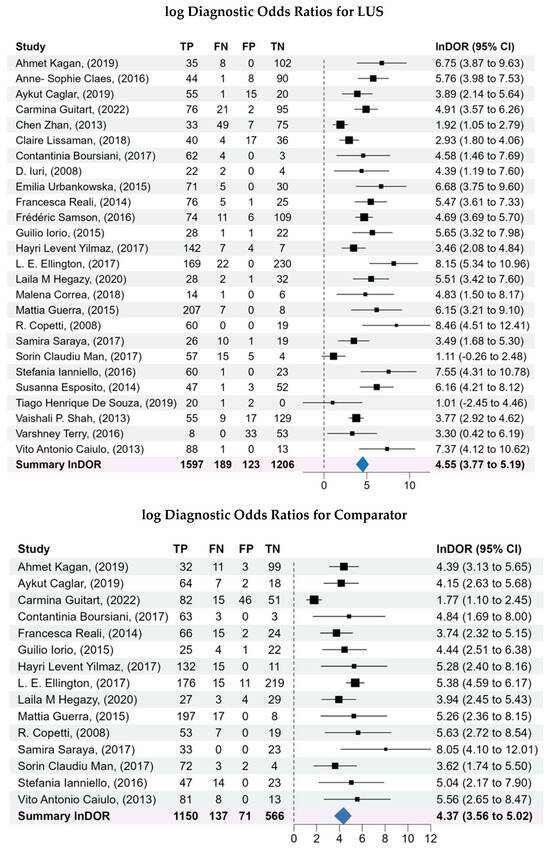

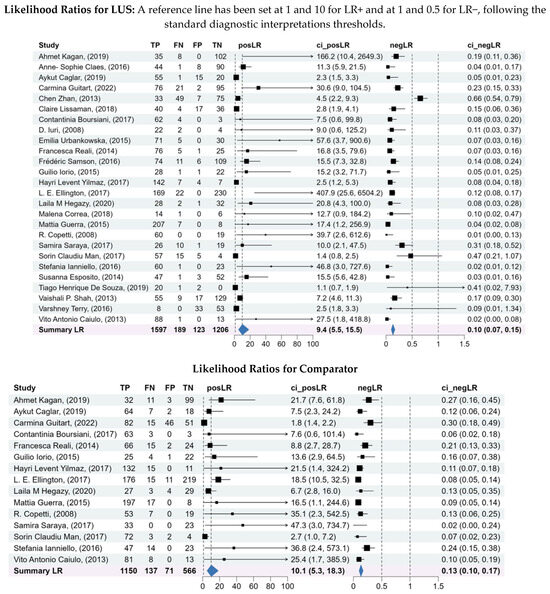

3.4. Forest Plot Analysis

Forest plots (Figure 3) confirm the consistent sensitivity for LUS across studies, with relatively homogenous estimates. Specificity values display more variability, but remain consistently high overall. In comparison, CXR shows more variable sensitivity across studies, whereas specificity estimates are more stable.

Figure 3.

Forest plots of the sensitivity and specificity, log diagnostic odds ratios, and likelihood ratios for both LUS and comparator. A bivariate analysis was conducted to assess the overall diagnostic capability of LUS compared to the comparators for diagnosis of pneumonia. A bivariate model was used to pool the sensitivity, specificity, log diagnostic odds ratios, and likelihood ratios of the included studies, considering the inherent correlation between these two measures of diagnostic accuracy.

3.5. Diagnostic Odds Ratios (DOR)

The pooled lnDOR for LUS was 4.55 (95% CI: 3.77–5.19), reflecting a strong association between positive LUS findings and pneumonia. The comparator lnDOR was slightly lower at 4.37 (95% CI: 3.56–5.02).

3.6. Likelihood Ratios

Pooled likelihood ratios further supported the diagnostic value of LUS. Positive LR resulted in 9.44 (95% CI: 5.48–15.5), demonstrating strong rule-in capability. Negative LR resulted in 0.10 (95% CI: 0.07–0.15), indicating reliable rule-out performance.

In contrast, comparators LR estimates were more heterogeneous, particularly in LR–values, suggesting that CXR was less consistent in excluding pneumonia compared to LUS. Details are shown in Figure 3.

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis confirms that LUS is a reliable, accurate, and clinically useful diagnostic tool for pneumonia in critically ill children. Our findings align with prior meta-analyses conducted in both paediatric and adult populations, which consistently reported high sensitivity and specificity for LUS compared with conventional imaging modalities [1,16,19,64,65,66,67]. Importantly, by focusing exclusively on paediatric patients in emergency and intensive care settings, our study reduces heterogeneity (I2 = 8.5%) and offers more targeted evidence relevant to high-acuity clinical scenarios compared to earlier studies. It also includes a larger population than most previous meta-analyses.

Across 30 studies and over 4300 patients, LUS achieved a pooled sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 90%, with excellent overall performance (AUC = 0.95). In other individual studies [1,67], LUS consistently demonstrated superior Se compared to CXR, highlighting LUS’ high diagnostic precision. These values confirm LUS as a powerful tool for both ruling in and out pneumonia, with strong positive [39,53] and negative likelihood ratios [17,41]. Compared to CXR, which showed slightly lower sensitivity but comparable specificity, LUS demonstrated superior consistency and reliability across settings [19,66]. Yan et al. further emphasised CXR limitations, noting its lower Se (91%), suggesting that CXR may miss mild or early-stage pneumonia cases [66].

Several individual studies highlight the particular strengths of LUS. Caiulo et al. reported sensitivity approaching 99%, emphasising its ability to detect small consolidations that may be missed on CXR [39]. Iuri et al. and others further demonstrated LUS’s advantage in detecting pleural effusions and pneumonia-related complications, underscoring its role as a comprehensive bedside imaging modality [37]. Moreover, the repeatability and radiation-free nature of LUS make it ideal for monitoring disease progression and treatment response, something CXR and CT cannot provide without exposing patients to additional risks.

These findings solidify LUS as a clinically valuable tool, particularly in resource-limited settings where rapid, reliable diagnostics are crucial. By ensuring accurate case identification, LUS aids in optimising treatment decisions, potentially reducing unnecessary antibiotic use and improving patient outcomes. Its high diagnostic accuracy minimises uncertainty, a key challenge in emergency and intensive care settings.

The meta-analysis results are broadly aligned with those reported by Houri et al., who analysed six studies involving 1099 paediatric patients with suspected pneumonia and reported a pooled sensitivity of 90.9% (95% CI: 85.5–94.4%) and specificity of 80.7% (95% CI: 63.6–91.0%). In comparison, our analysis, which included 30 studies and a more diverse patient population, yielded a comparable pooled sensitivity of 91% (95% CI: 87–94%) but a higher specificity of 90% (95% CI: 83–94%), with low heterogeneity. This difference may be attributable to methodological factors. Houri et al. reported inconsistent operator training, potentially introducing performance bias, and their specificity estimates showed high variability. By contrast, our study applied inclusion criteria regarding operator expertise and setting, thereby achieving greater diagnostic consistency.

When compared with other meta-analyses [1,19,64,65,66,67], our study demonstrated much lower heterogeneity (I2 = 8.5% vs. 52–85% in previous reviews). This consistency likely reflects the exclusion of studies focused on neonatal population, the emphasis on standardised comparators (mostly CXR or CT), and the inclusion of studies from healthcare systems with more uniform protocols. However, some variability in Se and Sp persisted across studies. While the pooled heterogeneity statistic was low, this primarily reflects statistical consistency and may not capture remaining methodological differences. Although most studies used a linear probe and comprehensive multi-zone scanning, variability persisted in exact scanning protocols, image interpretation criteria, and operator experience—factors that could influence diagnostic performance in practice.

Studies with smaller or more diverse populations exhibited wider intervals. Despite this variability, the pooled estimates confirmed LUS as a reliable diagnostic tool across clinical settings, with Se values clustering towards the higher end, indicating consistent pneumonia detection. CXR showed greater variability, suggesting that LUS provides more stable diagnostic accuracy than traditional imaging methods.

Operator expertise remains a key factor influencing LUS accuracy. Experienced clinicians consistently report higher Se and Sp compared to novices, as demonstrated in studies as Tsou et al. [65] and Guitart et al. [17]. Inexperienced operators, by contrast, tend to underestimate findings, leading to reduced sensitivity [48]. Interobserver agreement also decreases with less training, highlighting the need for standardised education and competency assessment [68]. The implementation of structured training programmes, as suggested by Orso et al., would improve diagnostic consistency and ensure reliable performance across different clinical settings [16].

Beyond initial diagnosis, LUS provides added value by facilitating longitudinal monitoring. Several studies have shown its feasibility in tracking consolidations and pleural effusions, guiding antibiotic stewardship, and supporting timely clinical decisions without exposing children to repeated radiation [46,53]. This feature is particularly important in paediatric intensive care units, where patients often require frequent reassessments and radiation-free imaging becomes more sensitive.

Overall, this meta-analysis reinforces LUS as a safe, accurate, and versatile tool for diagnosing paediatric pneumonia. Its portability, non-invasive nature, and strong diagnostic performance make it especially valuable in emergency and critical care environments, as well as in resource-limited settings where access to advanced imaging may be restricted. By enabling earlier and more precise diagnosis, LUS can improve clinical outcomes, reduce unnecessary antibiotic use, and optimise resource utilisation.

5. Limitations

This meta-analysis has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Although heterogeneity was lower than in previous reviews, some variability persisted across included studies. This likely reflects differences in study design, patient demographics, operator expertise, and ultrasound protocols. The lack of standardised criteria for LUS interpretation across studies may have further contributed to variability. Operator dependence remains a key issue, while experienced clinicians demonstrated consistently high diagnostic accuracy, results were less reliable when LUS was performed by less trained operators. In addition, the presence of publication bias cannot be excluded, Egger’s test was statistically significant (p < 0.005), and visual funnel plots (Supplementary Material, Figure S1) suggest that studies reporting higher diagnostic accuracy were more likely to be published, potentially leading to a modest overestimation of LUS performance.

Finally, variability in comparator methods, such as reliance on clinical diagnosis in some studies versus CXR or CT in others, may have led to the overestimation or underestimation of accuracy. Although the bivariate model accounts for inter-study variability, the use of non-uniform reference standards (clinical, CXR, CT, or composite criteria) remains a limitation that could influence the pooled accuracy estimates.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides strong evidence that LUS is a highly accurate and reliable tool for diagnosing pneumonia in critically ill paediatric patients. Future research should focus on standardising diagnostic criteria and follow-up. By addressing these aspects, LUS could be fully established as a first-line imaging modality for paediatric pneumonia, improving diagnostic certainty and patient outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics15243122/s1, Figure S1. Funnel plots; Figure S2. QUADAS-2 Risk of Bias Assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G., M.B., S.B.-P., and I.J.; Methodology, J.L.C. and G.P.; Software, J.L.C. and G.P.; Validation, C.G., M.B., S.B.-P., and I.J.; Formal Analysis, J.L.C. and G.P.; Investigation, C.G., M.B., S.B.-P., and I.J.; Resources, C.G., M.B., S.B.-P., and I.J.; Data Curation, C.G., M.B., S.B.-P., and I.J.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.B., C.G., and M.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.B., C.G., M.B., I.J., J.L.C., G.P. and S.B.-P.; Visualisation, J.B., C.G., M.B., I.J., J.L.C., G.P. and S.B.-P.; Supervision, C.G., M.B., S.B.-P., J.L.C., and I.J.; Project Administration, C.G. and M.B.; Funding Acquisition, C.G., M.B., S.B.-P., and I.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Sant Joan de Déu Scientific Library team for their expert assistance in designing the search strategy and to all members of the research group for their continued support. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Rayyan QCRI [21] for the systematic review screening process. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pereda, M.A.; Chavez, M.A.; Hooper-Miele, C.C.; Gilman, R.H.; Steinhoff, M.C.; Ellington, L.E.; Gross, M.; Price, C.; Tielsch, J.M.; Checkley, W. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: A meta-analysis. Pediatr. Am. Acad. Pediatr. 2015, 135, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Pneumonia in Children. 2022. Available online: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/pneumonia (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- UNICEF Data. Pneumonia. 2023. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/pneumonia/#:~:text=Globally%2C%20there%20are%20over%201%2C400,1%2C620%20cases%20per%20100%2C000%20children (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Boeddha, N.P.; Schlapbach, L.J.; Driessen, G.J.; Herberg, J.A.; Rivero-Calle, I.; Cebey-López, M.; Klobassa, D.S.; Philipsen, R.; De Groot, R.; Inwald, D.P.; et al. Mortality and morbidity in community-acquired sepsis in European pediatric intensive care units: A prospective cohort study from the European Childhood Life-threatening Infectious Disease Study (EUCLIDS). Crit Care 2018, 22, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinkugbe, O.; Cooke, F.J.; Pathan, N. Healthcare-Associated bacterial infections in the paediatric ICU. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 2, dlaa066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, C.L.F.; Rudan, I.; Liu, L.; Nair, H.; Theodoratou, E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; O’Brien, K.L.; Campbell, H.; Black, R.E. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 2013, 381, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prayle, A.; Atkinson, M.; Smyth, A. Pneumonia in the developed world. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2011, 12, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MARKH EBELL. Clinical Diagnosis of Pneumonia in Children. Am. Fam. Physician 2010, 82, 192–193. Available online: http://www.aafp.org/afp/poc (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Shah, S.; Sharieff, G.Q. Pediatric Respiratory Infections. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 25, 961–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.J.; Macaskill, P.; Kerr, M.; Fitzgerald, D.A.; Isaacs, D.; Codarini, M.; McCaskill, M.; Prelog, K.; Craig, J.C. Variability and accuracy in interpretation of consolidation on chest radiography for diagnosing pneumonia in children under 5 years of age. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2013, 48, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsky, Y.; Mimouni, F.B.; Fisher, D.; Ehrlichman, M. Chest radiography of acute paediatric lower respiratory infections: Experience versus interobserver variation. Acta Paediatr. 2013, 102, e310–e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Kline, J.A. Intraobserver and interobserver agreement of the interpretation of pediatric chest radiographs. Emerg. Radiol. 2010, 17, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, T.A.; French, B.; Zorc, J.J.; Alpern, E.R.; Shah, S.S. Variation in Emergency Department Diagnostic Testing and Disposition Outcomes in Pneumonia. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.S.; Byington, C.L.; Shah, S.S.; Alverson, B.; Carter, E.R.; Harrison, C.; Kaplan, S.L.; Mace, S.E.; McCracken, G.H.; Moore, M.R.; et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: Clinical practice guidelines by the pediatric infectious diseases society and the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, e25–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frush, D.P.; Donnelly, L.F.; Rosen, N.S. Computed tomography and radiation risks: What pediatric health care providers should know. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orso, D.; Ban, A.; Guglielmo, N. Lung ultrasound in diagnosing pneumonia in childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ultrasound 2018, 21, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Fanjul, J.; Guitart, C.; Bobillo-Perez, S.; Balaguer, M.; Jordan, I. Procalcitonin and lung ultrasound algorithm to diagnose severe pneumonia in critical paediatric patients (PROLUSP study). A randomised clinical trial. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, C.; Rodríguez-Fanjul, J.; Bobillo-Perez, S.; Carrasco, J.L.; Clemente, E.J.I.; Cambra, F.J.; Balaguer, M.; Jordan, I. An algorithm combining procalcitonin and lung ultrasound improves the diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia in critically ill children: The PROLUSP study, a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Xiao, H.; Chen, B.; Zhang, S.Y. Accuracy of lung ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of adult community-acquired pneumonia: Review of the literature and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M. QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, C.; Salanti, G.; Morton, S.C.; Riley, R.D.; Chu, H.; Kimmel, S.E.; Chen, Y. Discussion on “Testing small study effects in multivariate meta-analysis” by Chuan Hong, Georgia Salanti, Sally Morton, Richard Riley, Haitao Chu, Stephen E. Kimmel, and Yong Chen. Biometrics 2020, 76, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2019, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dersimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-Analysis in Clinical Trials. Control Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. The comparison of percentages in matched sample. Biometrika 1950, 37, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, P.; Davenport, C.; Deeks, J.; Hyde, C.; Leeflang, M.; Scholten, R. Chapter 11 Interpreting Results and Drawing Conclusions. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Version 0.9; Deeks, J.J., Bossuyt, P.M., Gatsonis, C., Eds.; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2013; Available online: http://srdta.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Reitsma, J.B.; Glas, A.S.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Scholten, R.J.P.M.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Zwinderman, A.H. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doebler, P.; Sousa-Pinto, B. Mada: Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mada (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Zwinderman, A.H.; Bossuyt, P.M. We should not pool diagnostic likelihood ratios in systematic reviews. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noma, H.; Matsushima, Y.; Ishii, R. Confidence interval for the AUC of SROC curve and some related methods using bootstrap for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Commun. Stat. Case Stud. Data Anal. Appl. 2021, 7, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, C.M.; Gatsonis, C.A. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat. Med. 2001, 20, 2865–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimu, D. Forestploter: Create a Flexible Forest Plot. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=forestploter (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Copetti, R.; Cattarossi, L. Diagnosi ecografica di polmonite nell’età pediatrica. Radiol. Medica 2008, 113, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, J.; Levin, T.L.; Han, B.K.; Taragin, B.H.; Weinstein, S. Comparison of ultrasound and CT in the evaluation of pneumonia complicated by parapneumonic effusion in children. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 193, 1648–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iuri, D.; De Candia, A.; Bazzocchi, M. Valutazione del quadro polmonare nei pazienti pediatrici con sospetto clinico di polmonite: Apporto dell’ecografia. Radiol. Medica 2009, 114, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.P.; Tunik, M.G.; Tsung, J.W. Prospective evaluation of point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caiulo, V.A.; Gargani, L.; Caiulo, S.; Fisicaro, A.; Moramarco, F.; Latini, G.; Picano, E.; Mele, G. Lung ultrasound characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2013, 48, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Papa, S.S.; Borzani, I.; Pinzani, R.; Giannitto, C.; Consonni, D.; Principi, N. Performance of Lung Ultrasonography in Children with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 37. Available online: http://www.ijponline.net/content/40/1/37 (accessed on 1 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Reali, F.; Papa, G.F.S.; Carlucci, P.; Fracasso, P.; Di Marco, F.; Mandelli, M.; Soldi, S.; Riva, E.; Centanni, S. Can lung ultrasound replace chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumonia in hospitalized children? Respiration 2014, 88, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianova, T.I.; Dianova, T.I. Ultrasound monitoring and age sonographic characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in children. Sovrem. Tehnol. Med. 2015, 7, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbankowska, E.; Krenke, K.; Drobczyński, Ł.; Korczyński, P.; Urbankowski, T.; Krawiec, M.; Kraj, G.; Brzewski, M.; Kulus, M. Lung ultrasound in the diagnosis and monitoring of community acquired pneumonia in children. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.C.; Ker, C.R.; Hsu, J.H.; Wu, J.R.; Dai, Z.K.; Chen, I.C. Usefulness of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2015, 56, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, G.; Capasso, M.; De Luca, G.; Prisco, S.; Mancusi, C.; Laganà, B.; Comune, V. Lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: Proposal for a new diagnostic algorithm. PeerJ. 2015, 3, e1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.; Crichiutti, G.; Pecile, P.; Romanello, C.; Busolini, E.; Valent, F.; Rosolen, A. Ultrasound detection of pneumonia in febrile children with respiratory distress: A prospective study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianniello, S.; Piccolo, C.L.; Buquicchio, G.L.; Trinci, M.; Miele, V. First-line diagnosis of paediatric pneumonia in emergency: Lung ultrasound (LUS) in addition to chest-X-ray (CXR) and its role in follow-up. Br. J. Radiol. 2016, 89, 20150998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Grundtvig, N.; Klug, H. Performance of Bedside Lung Ultrasound by a Pediatric Resident A Useful Diagnostic Tool in Children With Suspected Pneumonia. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2016, 34, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, T.; Mok, E.; Shapiro, A.J.; Li, P.; Dubrovsky, A.S. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in young children with respiratory tract infections and wheeze. Emerg. Med. J. 2016, 33, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, A.S.; Clapuyt, P.; Menten, R.; Michoux, N.; Dumitriu, D. Performance of chest ultrasound in pediatric pneumonia. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 88, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.L.; Özkaya, A.K.; Sarı Gökay, S.; Tolu Kendir, Ö.; Şenol, H. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in children with community acquired pneumonia. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 35, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursiani, C.; Tsolia, M.; Koumanidou, C.; Malagari, A.; Vakaki, M.; Karapostolakis, G.; Mazioti, A.; Alexopoulou, E. Lung Ultrasound as First-Line Examination for the Diagnosis of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Children. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2017, 33, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, K.K.; Awasthi, S.; Parihar, A. Lung Ultrasound is Comparable with Chest Roentgenogram for Diagnosis of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Hospitalised Children. Indian J. Pediatr. 2017, 84, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraya, S.; El Bakry, R. Ultrasound: Can it replace CT in the evaluation of pneumonia in pediatric age group? Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2017, 48, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, S.C.; Fufezan, O.; Sas, V.; Schnell, C. Performance of lung ultrasonography for the diagnosis of communityacquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Med. Ultrason. 2017, 19, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellington, L.E.; Gilman, R.H.; Chavez, M.A.; Pervaiz, F.; Marin-Concha, J.; Compen-Chang, P.; Riedel, S.; Rodriguez, S.J.; Gaydos, C.; Hardick, J.; et al. Lung ultrasound as a diagnostic tool for radiographically-confirmed pneumonia in low resource settings. Respir. Med. 2017, 128, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, F.; Gorostiza, I.; González, A.; Landa, M.; Ruiz, L.; Grau, M. Prospective evaluation of clinical lung ultrasonography in the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in a pediatric emergency department. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.; Zimic, M.; Barrientos, F.; Barrientos, R.; Román-Gonzalez, A.; Pajuelo, M.J.; Anticona, C.; Mayta, H.; Alva, A.; Solis-Vasquez, L.; et al. Automatic classification of pediatric pneumonia based on lung ultrasound pattern recognition. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissaman, C.; Kanjanauptom, P.; Ong, C.; Tessaro, M.; Long, E.; O’Brien, A. Prospective observational study of point-of-care ultrasound for diagnosing pneumonia. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkaya, A.K.; Başkan Vuralkan, F.; Ardıç, Ş. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in children with non-cardiac respiratory distress or tachypnea. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 2102–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, T.H.; Nadal, J.A.H.; Peixoto, A.O.; Pereira, R.M.; Giatti, M.P.; Soub, A.C.S.; Brandão, M.B. Lung ultrasound in children with pneumonia: Interoperator agreement on specific thoracic regions. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlar, A.; Ulusoy, E.; Er, A.; Akgül, F.; Çitlenbik, H.; Yılmaz, D.; Duman, M. Is lung ultrasonography a useful method to diagnose children with community-acquired pneumonia in emergency settings? Hong Kong J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, L.M.; Rezk, A.R.; Sakr, H.M.; Ahmed, A.S. Comparison of efficacy of lus and cxr in the diagnosis of children presenting with respiratory distress to emergency department. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Xu, X.; Xu, Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the accuracy of lung ultrasound and chest radiography in diagnosing community acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 3130–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, P.-Y.; Chen, K.P.; Wang, Y.-H.; Fishe, J.; Gillon, J.; Lee, C.-C.; Deanehan, J.K.; Kuo, P.-L.; Yu, D.T.Y. Diagnostic Accuracy of Lung Ultrasound Performed by Novice Versus Advanced Sonographers for Pneumonia in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.H.; Yu, N.; Wang, Y.H.; Gao, Y.B.; Pan, L. Lung ultrasound vs chest radiography in the diagnosis of children pneumonia: Systematic evidence. Medicine 2020, 99, E23671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balk, D.S.; Lee, C.; Schafer, J.; Welwarth, J.; Hardin, J.; Novack, V.; Yarza, S.; Hoffmann, B. Lung ultrasound compared to chest X-ray for diagnosis of pediatric pneumonia: A meta-analysis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2018, 53, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, S.; Ganatra, H.; Martinez, E.; Mannaa, M.; Peters, J. Accuracy and reliability of bedside thoracic ultrasound in detecting pulmonary pathology in a heterogeneous pediatric intensive care unit population. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2019, 47, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).