Serum Phenylacetylglutamine Is a Potential Risk Factor for Aortic Stiffness in Patients with Chronic Hemodialysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Anthropometric and Biochemical Measurements

2.3. Blood Pressure and Aortic Stiffness Assessment

2.4. Determination of Serum PAG Concentrations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

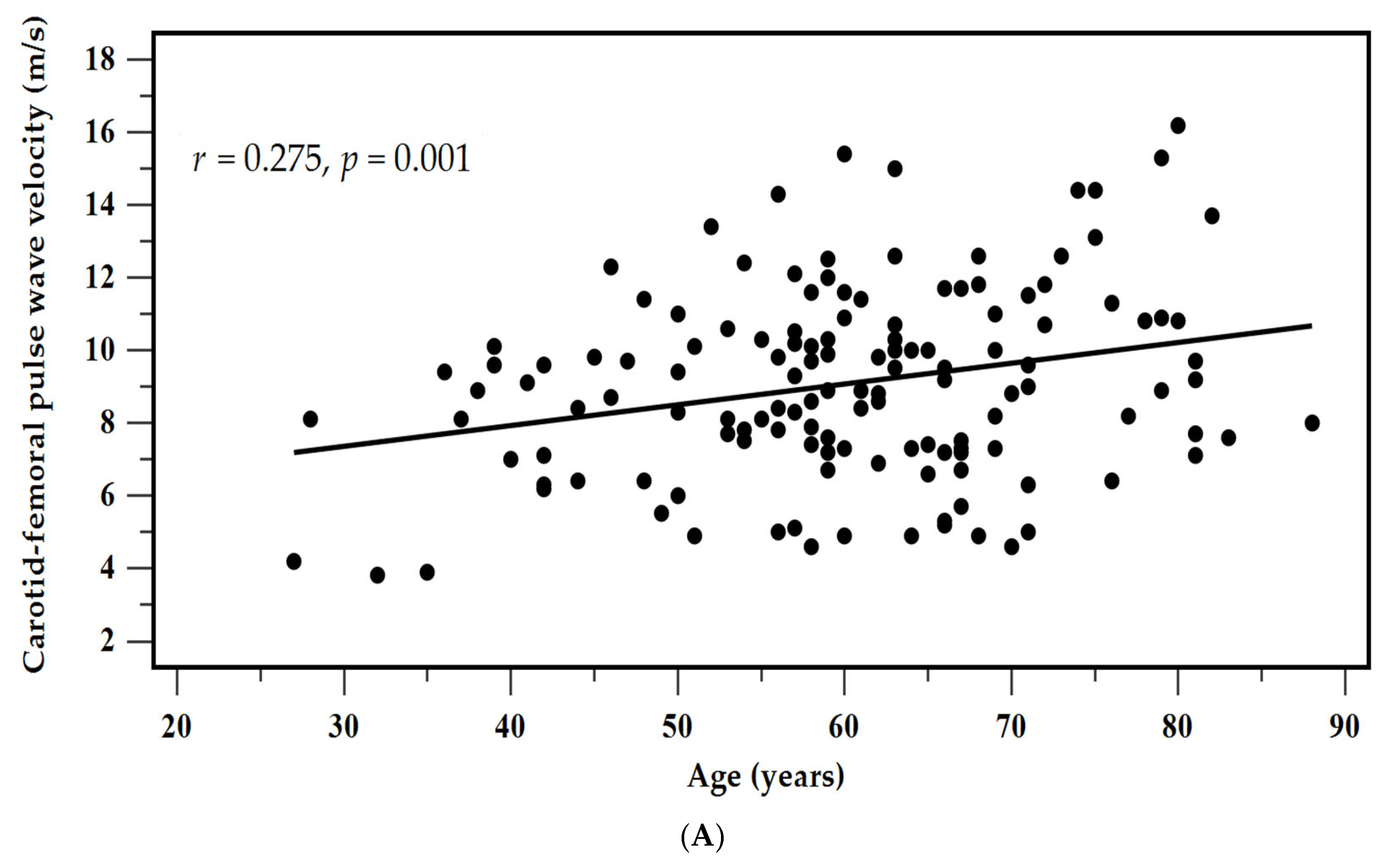

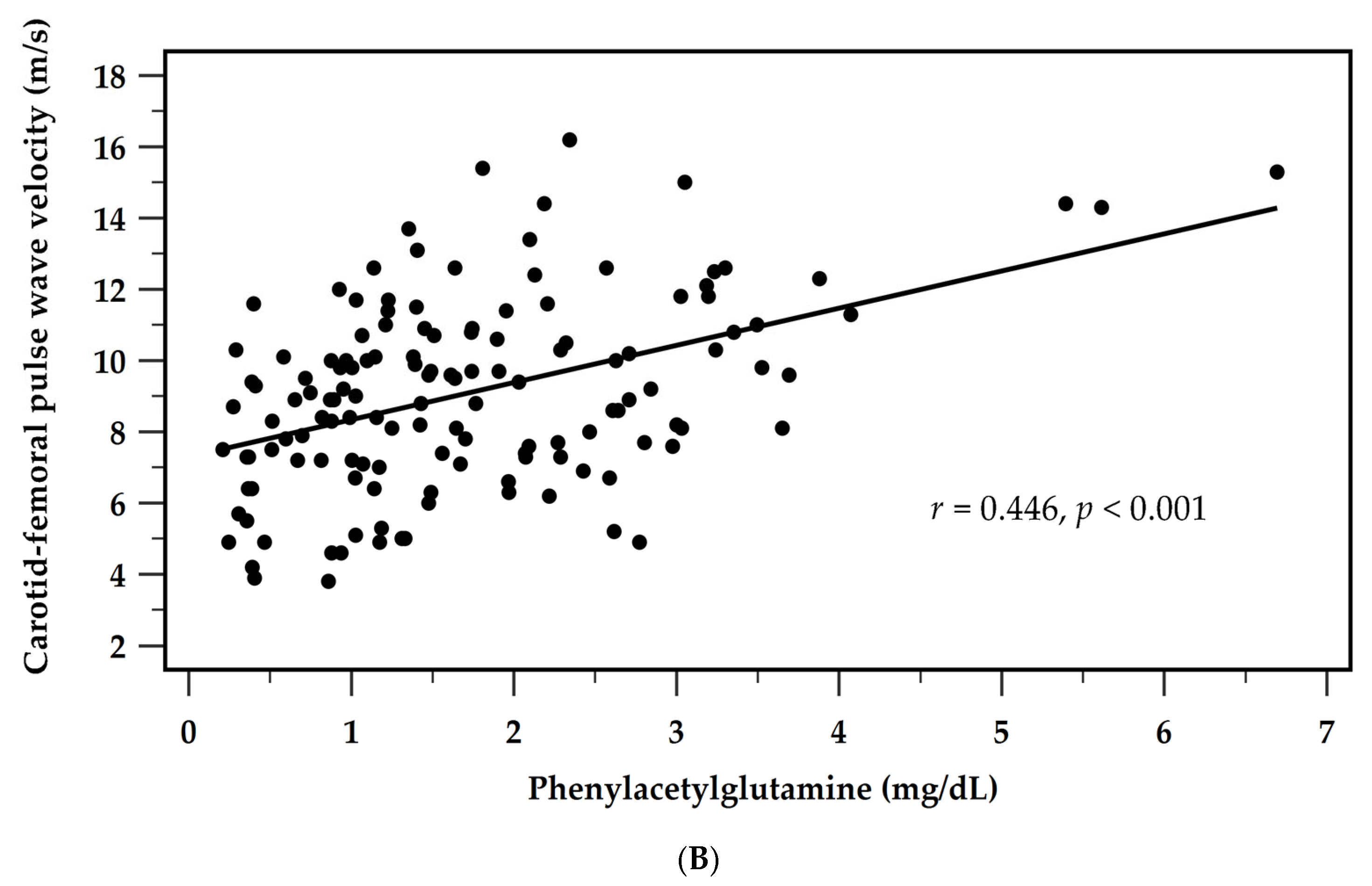

3.2. Factors Associated with Aortic Stiffness

3.3. Determinants of cfPWV

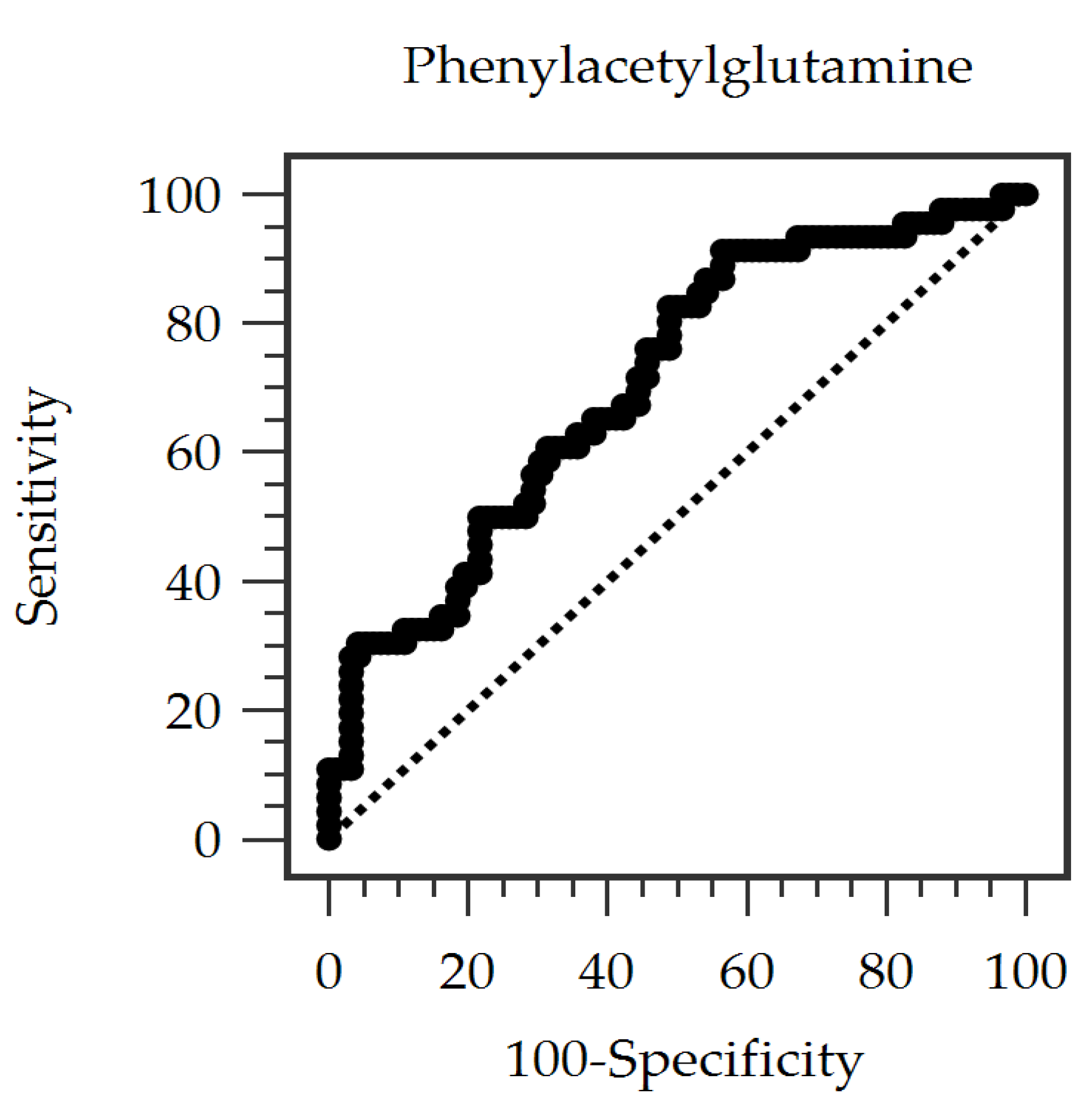

3.4. Predictive Performance of Serum PAG

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| cfPWV | Carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| HD | Hemodialysis |

| HPLC–MS | High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

| iPTH | Intact parathyroid hormone |

| PAG | Phenylacetylglutamine |

| PWV | Pulse wave velocity |

References

- Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G.; Osman, M.A.; Cho, Y.; Htay, H.; Jha, V.; Wainstein, M.; Johnson, D.W. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Mangano, M.; Stucchi, A.; Ciceri, P.; Conte, F.; Galassi, A. Cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2018, 33, iii28–iii34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadmehrabi, S.; Tang, W.H.W. Hemodialysis-induced cardiovascular disease. Semin. Dial. 2018, 31, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Adamczak, M.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Massy, Z.A.; Sarafidis, P.; Agarwal, R.; Mark, P.B.; Kotanko, P.; Ferro, C.J.; et al. Cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease: A review from the European Renal and Cardiovascular Medicine Working Group of the European Renal Association. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2017–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, J.; Floege, J.; Fliser, D.; Böhm, M.; Marx, N. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: Pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation 2021, 143, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C.; Kuo, C.H.; Lin, Y.L.; Hsu, B.G. Gut-derived uremic toxins and cardiovascular health in chronic kidney disease. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2025, 37, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacher, J.; Guerin, A.P.; Pannier, B.; Marchais, S.J.; London, G.M. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 2001, 38, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korjian, S.; Daaboul, Y.; El-Ghoul, B.; Samad, S.; Salameh, P.; Dahdah, G.; Hariri, E.; Mansour, A.; Spielman, K.; Blacher, J.; et al. Change in pulse wave velocity and short-term development of cardiovascular events in the hemodialysis population. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2016, 18, 857–863. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, S.; Cockcroft, J.; Van Bortel, L.; Boutouyrie, P.; Giannattasio, C.; Hayoz, D.; Pannier, B.; Vlachopoulos, C.; Wilkinson, I.; Struijker-Boudier, H. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: Methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 2588–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Gawałko, M.; Agbaedeng, T.A.; Saljic, A.; Müller, D.N.; Wilck, N.; Schnabel, R.; Penders, J.; Rienstra, M.; van Gelder, I.; Jespersen, T.; et al. Gut microbiota, dysbiosis and atrial fibrillation. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms and potential clinical implications. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, I.; Saha, P.P.; Gupta, N.; Zhu, W.; Romano, K.A.; Skye, S.M.; Cajka, T.; Mohan, M.L.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. A cardiovascular disease-linked gut microbial metabolite acts via adrenergic receptors. Cell 2020, 180, 862–877.e822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yu, B.; Alexander, D.; Manolio, T.A.; Aguilar, D.; Coresh, J.; Heiss, G.; Boerwinkle, E.; Nettleton, J.A. Associations between metabolomic compounds and incident heart failure among African Americans: The ARIC Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottosson, F.; Brunkwall, L.; Smith, E.; Orho-Melander, M.; Nilsson, P.M.; Fernandez, C.; Melander, O. The gut microbiota-related metabolite phenylacetylglutamine associates with increased risk of incident coronary artery disease. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 2427–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Cai, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Han, X.; Tian, J.; Jin, S.; Yan, Z.; Li, Y.; Lu, B.; et al. Phenylacetylglutamine as a novel biomarker of type 2 diabetes with distal symmetric polyneuropathy by metabolomics. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2023, 46, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arefin, S.; Mudrovcic, N.; Hobson, S.; Pietrocola, F.; Ebert, T.; Ward, L.J.; Witasp, A.; Hernandez, L.; Wennberg, L.; Lundgren, T.; et al. Early Vascular Aging in Chronic Kidney Disease: Focus on Microvascular Maintenance, Senescence Signature and Potential Therapeutics. Transl. Res. 2025, 275, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Ho, C.-C.; Hsu, B.-G. Serum Phenylacetylglutamine among Potential Risk Factors for Arterial Stiffness Measuring by Carotid–Femoral Pulse Wave Velocity in Patients with Kidney Transplantation. Toxins 2024, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, T.; Meyer, T.W.; Hostetter, T.H.; Melamed, M.L.; Parekh, R.S.; Hwang, S.; Banerjee, T.; Coresh, J.; Powe, N.R. Free Levels of Selected Organic Solutes and Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients: Results from the Retained Organic Solutes and Clinical Outcomes (ROSCO) Investigators. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Wu, P.H.; Lin, Y.T.; Hung, S.C. Gut dysbiosis and mortality in hemodialysis patients. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.Y.; Huang, C.S.; Lin, Y.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Hung, S.C.; Tsai, J.P.; Hsu, B.G. Positive association of serum galectin-3 with the development of aortic stiffness of patients on peritoneal dialysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.K. Errors in the use of multivariable logistic regression analysis: An empirical analysis. Indian J. Community Med. 2020, 45, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Ren, C.; Hu, J.; Greenberg, D.A.; Chen, T.; Xie, L.; Jin, K. Age-related impairment of vascular structure and functions. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, J.D. Mechanisms of vascular remodeling in hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rask-Madsen, C.; King, G.L. Vascular complications of diabetes: Mechanisms of injury and protective factors. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneni, F.; Beckman, J.A.; Creager, M.A.; Cosentino, F. Diabetes and vascular disease: Pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part I. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2436–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, I.; Li, X.S.; Haghikia, A.; Li, L.; Wilcox, J.; Romano, K.A.; Buffa, J.A.; Witkowski, M.; Demuth, I.; König, M.; et al. Atlas of gut microbe-derived products from aromatic amino acids and risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3085–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Kong, B.; Zhu, J.; Huang, H.; Shuai, W. Phenylacetylglutamine increases the susceptibility of ventricular arrhythmias in heart failure mice by exacerbated activation of the TLR4/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekawanvijit, S.; Kompa, A.R.; Wang, B.H.; Kelly, D.J.; Krum, H. Cardiorenal syndrome: The emerging role of protein-bound uremic toxins. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 1470–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Li, X.; Feng, X.; Wei, M.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, T.; Xiao, B.; Xia, J. Phenylacetylglutamine, a novel biomarker in acute ischemic stroke. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 798765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; Hang, W.; Wu, J.; Wang, D.W. Gut microbiota-dependent phenylacetylglutamine in cardiovascular disease: Current knowledge and new insights. Front. Med. 2024, 18, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curaj, A.; Vanholder, R.; Loscalzo, J.; Quach, K.; Wu, Z.; Jankowski, V.; Jankowski, J. Cardiovascular consequences of uremic metabolites: An overview of the involved signaling pathways. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Li, X.; Ghosh, S.; Xie, C.; Chen, J.; Huang, H. Role of gut microbiota-derived metabolites on vascular calcification in CKD. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 1332–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | All Patients (n = 138) | Control Group (n = 92) | Aortic Stiffness Group (n = 46) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.33 ± 12.30 | 58.57 ± 12.85 | 63.87 ± 10.34 | 0.016 * |

| Female, n (%) | 68 (49.3) | 50 (54.3) | 18 (39.1) | 0.092 |

| Height (cm) | 162.11 ± 9.43 | 161.40 ± 9.07 | 163.52 ± 10.08 | 0.215 |

| Pre-HD body weight (kg) | 68.67 ± 16.69 | 68.05 ± 16.98 | 69.91 ± 16.20 | 0.538 |

| Post-HD body weight (kg) | 66.45 ± 16.27 | 65.91 ± 16.64 | 67.52 ± 15.65 | 0.586 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.97 ± 5.08 | 25.97 ± 5.35 | 25.97 ± 4.55 | 0.996 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 152.72 ± 28.35 | 144.76 ± 26.48 | 168.65 ± 25.31 | <0.001 * |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80.17 ± 15.56 | 76.77 ± 13.59 | 86.98 ± 17.09 | <0.001 * |

| Diabetes mellitus, % (n) | 66 (47.8) | 38 (41.3) | 28 (60.9) | 0.030 * |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 83 (61.0) | 44 (49.5) | 38 (84.4) | <0.001 * |

| HD duration (months) | 75.84 (33.300–144.00) | 85.50 (45.57–144.93) | 48.90 (27.36–138.18) | 0.110 |

| Urea reduction rate | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.06 | 0.408 |

| Kt/V (Gotch) | 1.31 ± 0.19 | 1.31 ± 0.18 | 1.29 ± 0.21 | 0.488 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.70 ± 1.28 | 10.75 ± 1.33 | 10.59 ± 1.18 | 0.490 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.35 ± 0.52 | 4.34 ± 0.52 | 4.37 ± 0.51 | 0.781 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 148.53 ± 43.73 | 151.46 ± 45.35 | 142.67 ± 40.12 | 0.268 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 136.00 (90.50–202.50) | 136.00 (91.25–203.50) | 133.50 (86.50–189.50) | 0.674 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 159.00 ± 63.70 | 148.45 ± 46.01 | 180.11 ± 85.97 | 0.005 * |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 65.21 ± 17.11 | 65.33 ± 16.95 | 64.98 ± 17.61 | 0.911 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 10.16 ± 2.53 | 10.32 ± 2.57 | 9.84 ± 2.44 | 0.303 |

| Total calcium (mg/dL) | 9.35 ± 0.86 | 9.39 ± 0.90 | 9.27 ± 0.79 | 0.429 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.83 ± 1.40 | 4.93 ± 1.49 | 4.65 ± 1.18 | 0.268 |

| iPTH (pg/mL) | 288.55 (45.24–548.85) | 269.55 (143.35–637.97) | 290.95 (145.50–495.00) | 0.957 |

| Phenylacetylglutamine (mg/dL) | 1.72 ± 1.13 | 1.44 ± 0.88 | 2.28 ± 1.35 | <0.001 * |

| Carotid-femoral PWV (m/s) | 9.09 ± 2.64 | 7.64 ± 1.67 | 12.00 ± 1.59 | <0.001 * |

| Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylacetylglutamine, 1 mg/dL | 1.903 | 1.171–3.094 | 0.009 * |

| Age, 1 year | 1.042 | 1.001–1.084 | 0.044 * |

| Female | 0.589 | 0.227–1.528 | 0.276 |

| Hemodialysis duration, 1 month | 1.000 | 0.994–1.006 | 0.983 |

| Glucose, 1 mg/dL | 1.008 | 0.999–1.016 | 0.057 |

| Systolic blood pressure, 1 mmHg | 1.015 | 0.988–1.043 | 0.274 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, 1 mmHg | 1.033 | 0.992–1.077 | 0.119 |

| Diabetes mellitus, present | 1.298 | 0.457–3.688 | 0.625 |

| Hypertension, present | 1.017 | 0.268–3.861 | 0.980 |

| Variables | Carotid-Femoral PWV (m/s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Correlation | Multivariable Linear Regression | ||||

| r | p Value | Beta | Adjusted R2 Change | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 0.275 | 0.001 * | 0.180 | 0.025 | 0.013 * |

| Log-HD duration (months) | −0.144 | 0.093 | – | – | – |

| Height (cm) | 0.116 | 0.175 | – | – | – |

| Pre-HD body weight (kg) | 0.093 | 0.279 | – | – | – |

| Post-HD body weight (kg) | 0.087 | 0.309 | – | – | – |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 0.042 | 0.629 | – | – | – |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.436 | <0.001 * | 0.292 | 0.095 | <0.001 * |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.315 | <0.001 * | – | – | – |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | −0.003 | 0.972 | – | – | – |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.038 | 0.655 | – | – | – |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.104 | 0.224 | – | – | – |

| Log-Triglyceride (mg/dL) | −0.081 | 0.345 | – | – | – |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 0.236 | 0.006 * | 0.162 | 0.019 | 0.024 * |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | −0.027 | 0.750 | – | – | – |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | −0.123 | 0.150 | – | – | – |

| Total calcium (mg/dL) | −0.005 | 0.592 | – | – | – |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | −0.037 | 0.665 | – | – | – |

| Log-iPTH (pg/mL) | 0.026 | 0.761 | – | – | – |

| Phenylacetylglutamine (mg/dL) | 0.446 | <0.001 * | 0.313 | 0.193 | <0.001 * |

| Urea reduction rate | −0.046 | 0.592 | – | – | – |

| Kt/V (Gotch) | −0.037 | 0.665 | – | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, I.-M.; Wu, T.-J.; Liu, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-L.; Hsu, B.-G. Serum Phenylacetylglutamine Is a Potential Risk Factor for Aortic Stiffness in Patients with Chronic Hemodialysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3123. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243123

Su I-M, Wu T-J, Liu C-H, Lin Y-L, Hsu B-G. Serum Phenylacetylglutamine Is a Potential Risk Factor for Aortic Stiffness in Patients with Chronic Hemodialysis. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3123. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243123

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, I-Min, Tsung-Jui Wu, Chin-Hung Liu, Yu-Li Lin, and Bang-Gee Hsu. 2025. "Serum Phenylacetylglutamine Is a Potential Risk Factor for Aortic Stiffness in Patients with Chronic Hemodialysis" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3123. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243123

APA StyleSu, I.-M., Wu, T.-J., Liu, C.-H., Lin, Y.-L., & Hsu, B.-G. (2025). Serum Phenylacetylglutamine Is a Potential Risk Factor for Aortic Stiffness in Patients with Chronic Hemodialysis. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3123. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243123