Abstract

Healthcare-related homicidal cases are not novel within the medical–legal landscape, but investigations are often made difficult with the scarcity of material evidence related to the crime. For this reason, it is necessary to carefully analyze the clinical documentation and employ ancillary forensic resources such as radiology, histopathology, and toxicology. In the presented scenario, the observation of 14 deaths from abnormal bleeding in a First-Level Italian Hospital revealed the administration of massive doses of heparin by a nurse. On behalf of the Judicial Authority, a multidisciplinary medical team investigated the case through the following steps: a thorough review of the clinical documentation, exhumation of the bodies belonging to the deceased patients, performing PMCT and autopsy, and collecting tissue samples for histopathological, immunohistochemical, and toxicological investigations. All the analyzed cases have been characterized by the observation of fatal hemorrhagic episodes not explained with the clinical conditions of the patients, confirmed using autopsy observations and the histological demonstration of the vitality of the lesions. However, due to the limited availability of biological material for the toxicological analysis, the indirect evidence from hematological analyses in hospitalized patients was crucial in demonstrating heparin overdose and its link to the recorded deaths. The present scenario demonstrates the fundamental importance of a multidisciplinary approach to cases of judicial interest related to the healthcare context. Therefore, the illustrated methodologies can be interpreted as an operational framework for similar future cases.

Keywords:

healthcare setting; forensic; murder; heparin overdose; fatal hemorrhage; PMCT; autopsy; Glycophorin A 1. Introduction

Events such as the execution of murders by healthcare workers in hospitals or other care facilities are not a novelty within the medical–legal field. Recent history is dotted with well-known episodes concerning healthcare-related deaths that are more or less explained with the clinical history of the victims [1]. Following similar events, the term “angel of death”, of Jewish origin [2], has been coined to define a serial killer employed in this specific field [3].

Based on a recent literature review of cases involving health professionals prosecuted or convicted of murder, 60% of these individuals fall into the nursing category, and 18% are in the medical class [4]. However, these data are strongly influenced by the geographical context. Another scientific review focused specifically on the Western context (with 40% of the cases reported in the United States of America) and estimated that nursing staff make up as much as 86% of all killers. Additionally, despite the majority of people in the nursing profession being women, the small percentage of male nursing staff greatly skews this estimate [4].

As for the clinical context in which these crimes are perpetrated, it is essential to state that the preferred categories of patients are fragile individuals suffering from numerous comorbidities, and those of an extremely young or advanced age. Moreover, the hospital environment is the most popular venue for such events. The departments most frequently involved, in accordance with the category of patients targeted by these homicidal gestures, consist of General Medicine, Surgeries, and Intensive Care Units (ICUs) [4]. Within these contexts, access to medicines and drugs is often restricted to nursing staff, so in most cases of murder involving pharmacological substances, the active principle is not subjected to control [5]. For example, the use of insulin, although it is difficult to prove in post-mortem investigations [6].

Other examples of insidious substances include epinephrine, potassium chloride, and possible neuromuscular agents such as succinylcholine and pancuronium, as well as cardiac drugs like digoxin and lidocaine. In cases where the perpetrator does not have authorization to administer drugs, physical means of aggression are more commonly used. Mechanical suffocation through insidious methods, such as forcibly administered water, is a widely employed method [7].

The main problem associated with these events is the difficulty of identifying the cases and initiating judicial investigations, as these acts often go unnoticed due to the fragility of the most frequently targeted patients.

From a statistical perspective, the factor that often raises initial suspicion of the absence of accidental events in relation to numerous deaths is the low probability of a certain number of deaths occurring for the same cause in the same place within a limited time range. Specifically, this is frequently observed as an increase in cardiopulmonary arrests within the same hospital unit. Sometimes, perpetrators can leave a trail behind when changing workplaces, generating a “pseudo-epidemic” of such unusual events in the new setting. During investigations, additional parameters can be challenging to interpret. For instance, in cases of substance intoxication, one may expect an overdose of drugs used in therapy. Post-mortem toxicological investigations, especially after a significant period of time, can be significantly affected by catabolic transformative phenomena that alter the nature and quantity of the substances themselves [8]. However, the fact that non-medical personnel do not have access to these drugs is an important clue in narrowing down the number of suspects.

On the other hand, distinguishing between accidental and intentional administration may be a critical factor in court proceedings. Additionally, in cases where the cause of death is physical violence, the ability to observe and document injuries or wounds is of great assistance to the examiner. Moreover, the presence of multiple types of physical injuries may indicate long-term violence or abuse [9].

Therefore, approaching these cases requires a rigorous methodology and the utilization of all available means based on current scientific knowledge. Sometimes, due to the significant time span between the victims’ death and the initiation of judicial proceedings, traditional forensic techniques may be inapplicable. Consequently, it is often necessary to rely on pre-death blood tests, as biological fluids may be scarce or absent after months or years. However, when a body is buried in a zinc-plated case, it allows for a considerable degree of preservation through special transformative processes such as corification. It is crucial to consider that these processes can lead to post-mortem contamination with compounds like arsenic or lead, due to the chemical interaction with the metal elements of the coffin. Awareness of such phenomena is essential for accurate medical and legal judgment [10,11].

When possible, the approach may involve the exhumation of the body to perform specific clinical, radiological, and laboratory investigations, including the following:

- post-mortem radiological techniques [12,13,14,15];

- autopsy investigation;

- histopathological investigations on samples taken from the deceased;

- sampling of biological tissues suitable for toxicological investigations [11].

By employing these combined methods, it is possible to reach a correct classification of the cause of death. Integrating these data with the information contained in the clinical records allows for the answering of the specific case’s questions.

2. Materials and Methods

Between 2014 and 2015, an Intensive Care Unit of a First-Level Hospital in Italy recorded 14 deaths of patients who, despite suffering from severe morbidity, experienced unexplained hemorrhagic episodes. Due to strong suspicions of criminal activity related to these events, a judicial process was initiated, resulting in the investigation of a nurse for intentional murder.

Forensic investigations were conducted on the clinical records and bodies of eight of these patients, leading to conclusions supported with scientific evidence. These findings provided valuable support for the decision-making process of the Judicial Authority. This paper aims to illustrate the operational methodology employed in these investigations, emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in complex forensic cases. The objective of this work is to provide practical and reliable guidance for future investigations in this field.

On the basis of the information provided with clinical and investigative documentation, as well as the analysis relevant for judicial purposes, a multidisciplinary team of experts was appointed by the competent authorities to address the following questions:

- the administration and dosage of anticoagulant drugs available within the hospital of interest for the 14 patients under investigation;

- the causes of the 14 deaths and the potential responsibility of the hospital’s health services.

The initial step in the evaluation involved a meticulous examination of the clinical records of the deceased patients. Following this preliminary phase, further forensic investigations were conducted. The selection of the most appropriate investigations for the cases at hand had to consider the advanced state of decomposition of the cadavers.

It is important to note that the judicial autopsies commenced almost a year after the death of the last suspected case (in September 2015), which itself occurred approximately 20 months after the death of the initial case (in January 2014).

The appointed team performed cadaveric exhumation on 8 out of the 14 bodies under consideration (Table 1: Case 1, Case 2, Case 3, Case 4, Case 5, Case 6, Case 10, Case 14). These operations were not possible in the remaining six cases due to objective hindrances including the cremation of the corpse at the time of death.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical data related to the fourteen shown cases.

These bodies underwent initial radiological examinations, specifically total-body Post-Mortem Computed Tomography (PMCT), at the Complex Operational Unit (U.O.C.) of Emergency Radiology at Umberto I General Hospital in Rome. Each corpse was scanned with 16 slices using the following parameters: field of view (FOV) of 50 cm, slice thickness of 0.625 mm, interval of reconstruction of 1.25 mm, 120 kvp, 112 mA, and a 48 s scan time.

After a preliminary radiological assessment, a complete autopsy examination was conducted on the eight bodies at the Morgue of Umberto I General Hospital in Rome. Due to the advanced stage of putrefaction and transformative processes associated with burial in zinc-plated coffins, the visualization of pathological images was hindered. Nonetheless, the investigation allowed for the collection of biological fluids and tissues for further analyses.

Among these investigations, histopathological examinations were performed on the eight bodies, involving the collection of five “standard” samples from the following organs: brain, lung, heart, liver, and kidneys. Additional samples were taken from mucous or cutaneous areas affected by hemorrhagic infiltration.

Two different approaches were employed during these investigations: traditional histochemistry, utilizing van Gieson Elastic and Perls Prussian blue stainings, and immunohistochemistry, involving antigen–antibody reactions for Glycophorin A.

In order to achieve optimal results from the immunohistochemistry investigation, a meticulous preparation methodology was adopted, following the protocol outlined below:

- pre-treatment of the sample with 0.25 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) to facilitate antigenic screening and increase membrane permeability to antibodies;

- traditional fixation by passing the sample through an alcohol solution and then a formalin solution;

- washing in water and inclusion in paraffin;

- production of 4-µm-thick sections from paraffin blocks using a slide microtome;

- slide mounting by covering with 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane;

- application of anti-Glycophorin antibody A (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at a concentration of 1:500;

- incubation of the preparation for 120 min at an ambient temperature of 20 °C;

- detection using avidin–biotin reaction.

Subsequently, a toxicological investigation was conducted by sampling splenic, hepatic, and renal tissue through enzymatic hydrolysis and generic extraction of acidic and/or basic substances. The employed screening method consisted in liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and involved samples processed according to the following steps:

- solid-phase extraction (SPE) using Isolute HCX columns.

- cryophylation using nitrogen.

- inclusion using a 1% solution of acetonitrile and formic acid.

- untargeted analysis using a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry device from Thermo.

However, the toxicological tests could not address the fundamental investigative question of whether or not there was an overdose of heparin in the bodies under investigation. The LC-MS method has the ability to detect heparinic derivatives, but the need for large quantities of biological fluids due to losses during extraction made this investigation impracticable. The post-dehydration during autopsy procedures prevented the collection of any fluid useful for the investigation, particularly blood substances.

To partially address this problem, the hematological analyses of the deceased patients, available in all 14 cases, were observed. Specifically, the coagulation tests performed at the time with the Laboratory Analysis of a University Hospital in Italy were considered. Heparinemia was directly measured in the first four cases, providing direct data. In the remaining cases, an indirect evaluation of the biological action of heparin was possible by comparing the values of three parameters: Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT), Thrombin Time (TT), and Reptilase Time (RT).

In conclusion, it was possible to establish a causal link between the administration of heparin and the recorded deaths.

3. Results

A careful analysis of the sequence of events illustrated with the medical records of the 14 cases considered (Table 1) was fundamental as it allowed us to highlight two important aspects related to the case:

- the major hemorrhagic events could be attributed to the overdose of enoxaparin sodium;

- the observation of shifts helped establish the relationship between the facts described in the file and the health professionals involved.

Evidence showed that only 12 cases presented a significant hemorrhagic event during hospitalization (cases 1–12), and among these, only 10 cases (cases 1–10) demonstrated a causal link between hemorrhage and death.

Following the initial classification of the cases, a radiological investigation using PMCT was ordered for the available eight bodies. This choice was motivated by the technique’s worldwide success, known for its high sensitivity and specificity in detecting various clinical findings in a minimally invasive manner. The term “Virtopsy”, coined about 20 years ago [16,17], has gained widespread use in the medico-legal field to describe this approach, combining “Virtual” and “Autopsy”.

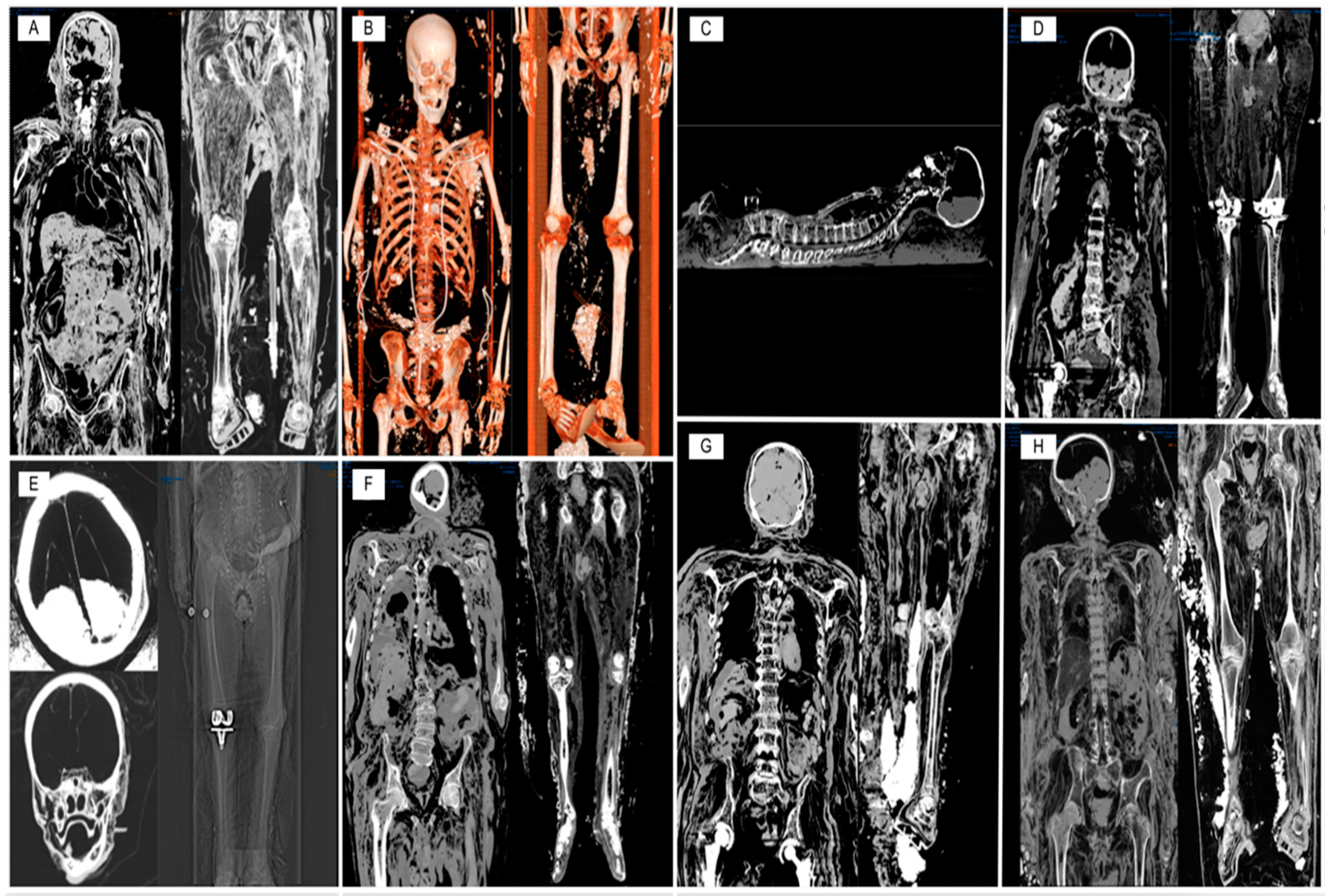

In the present case, the PMCT technique was particularly suitable as it allowed for the identification of any internal bleeding [18], employing high-energy, low-interference image acquisition protocols [19]. Despite the advanced stages of body transformation, these investigations facilitated a rapid and effective classification of the cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Details of PMCT investigations conducted on 8 exhumed bodies. (A) Case 1: widespread putrefactive phenomena characterized by adipose degeneration and gaseous production can be observed. In addition, outcome of surgical treatment for left pertrocanthric fracture is highlighted. (B) Case 2: it is possible to observe the progress of putrefactive phenomena, besides the presence of a cardiac pacemaker; a mitral valve prosthesis and lithiasic concretions to the urinary system bilaterally. (C) Case 3: a thoracic pacemaker and a fracture of the L3 vertebral body are observed in this case. (D) Case 4: the cerebral parenchyma assumes, by virtue of the putrefactive phenomena, the typical radiological aspect of “Swiss cheese”; we also observe the results of the positioning of right hip prostheses and bilateral knee prostheses. (E) Case 5: a substantial integrity of the somatic structures is observed, particularly of the skull containing little colliquate brain matter. In detail, result of placement of right total knee prosthesis. (F) Case 6: marked colliquative phenomena in fatty tissue. Further acquisitions allowed for objectifying the presence of cardiac pacemaker in situ. (G) Case 10: minor putrefactive phenomena, especially in fatty tissue. The spinal canal, however, is occupied by gaseous material of post-mortal origin. Bilateral hip prosthesis outcomes. (H) Case 14: evident bodi disintegration consequent to the advance of the putrefactive phenomena. Both kneecaps are dislocated laterally.

Subsequently, to confirm the results obtained from the radiological investigation, complete autopsies were performed on the eight available bodies. The bodies were exhumed by reopening the galvanized coffins in which they were placed. Due to the advanced post-mortem transformative processes, particularly corification, locating biological material (especially fluids) and identifying hemorrhagic skin patterns presented greater difficulty [20]. However, by utilizing the information provided with the clinical documentation, a satisfactory level of accuracy was achieved during the local examination.

Unfortunately, the same results could not be achieved following corpses’ evisceration because of the advanced degree of putrefaction: therefore, for each of them, five “standard” samples were obtained, including the brain, lung tissue, heart, liver, and kidneys. Moreover, when possible, additional samples were taken from mucous or cutaneous areas showing signs of hemorrhagic infarction [21]. Given the highly compromised state of the biological matter, the choice of histopathological methods was influenced. Therefore, the execution of traditional stains like hematoxylin and eosin was postponed due to the scarcity of residual cellular elements, including nuclei, organelles, and cytoplasmic membranes.

Instead, a specific histochemical staining for elastic fibers using van Gieson’s method was employed to achieve satisfactory visualization of structures less affected by post-mortem transformative processes. This staining technique combines multiple reagents (resorcinol–fuchsin for elastic fibers, Weigert’s iron hematoxylin for nuclear staining, picrofuchsin for collagen matrix) to enhance the visualization of residual biological structures that retain significant diagnostic value in forensics [22,23].

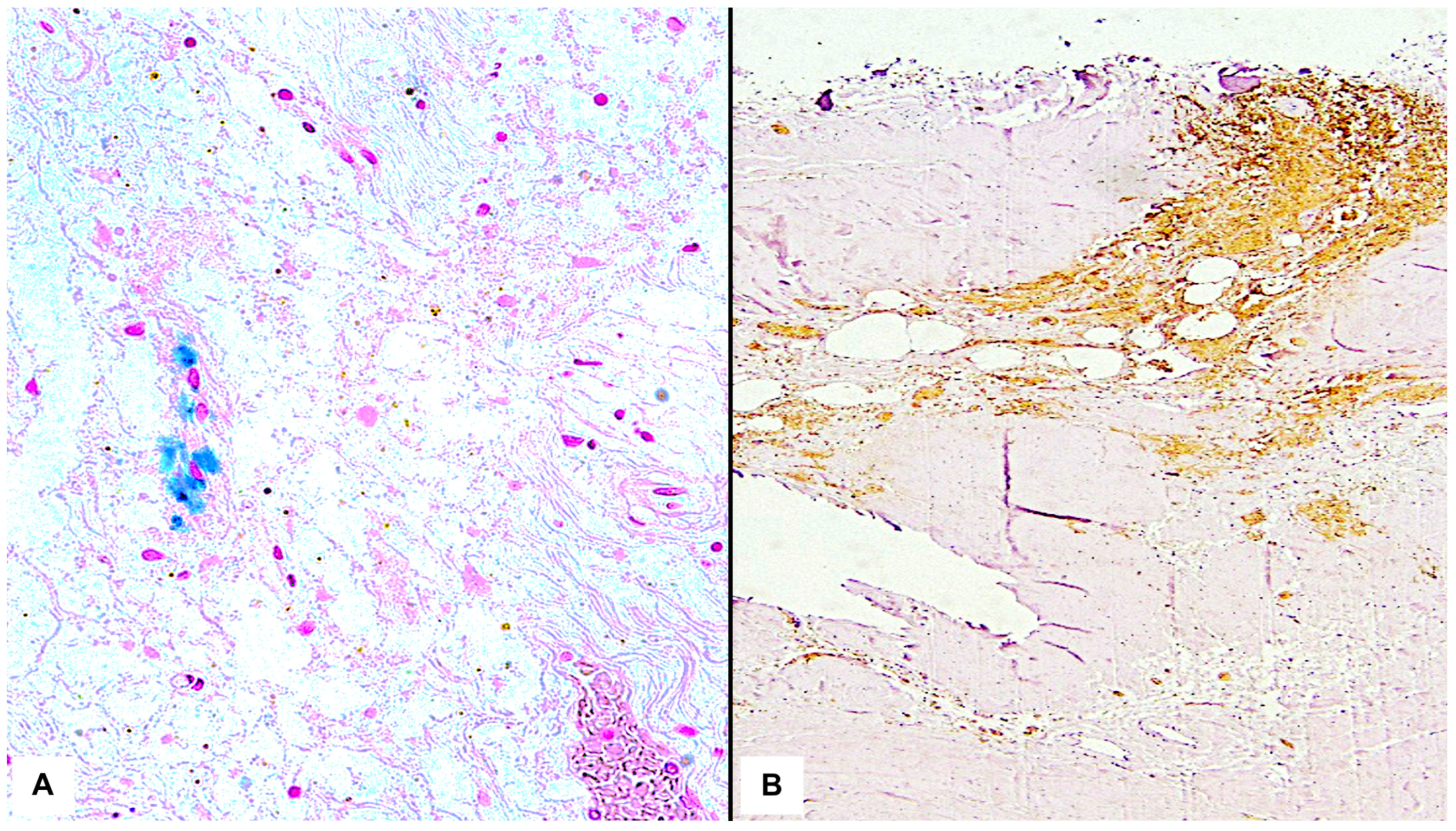

Furthermore, histochemical iron staining with Perls Prussian Blue was performed to highlight the presence of hemosiderin deposits [24], and an immunohistochemical study using the antibody reaction against Glycophorin A was conducted in the presented cases [25]. Glycophorin A, an antigen present on the surface of erythrocytes regardless of blood group, was chosen due to its high sensitivity in diagnosing hemorrhagic lesions, even at a considerable post-mortem interval (PMI) when macroscopic examination of tissues is hindered by putrefactive processes [26,27] (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Histopathological investigation results.

Figure 2.

Details of histochemical and immunohistochemical investigations conducted on autoptic biological samples. (A) Presence of positive reaction to Perls staining in brainstem. (B) Positive reaction to Glycophorin A in encephalic structures.

During the autopsy, biological tissues from the liver, spleen, and kidney were sampled for toxicological purposes, and the analyses were conducted using LC-MS. This specific choice was made due to the high throughput, soft ionization, and excellent metabolite detection capabilities of LC-MS [28]. Although its diffusion to date is limited (estimated to be less than 1% of modern diagnostic laboratory analyses), the forensic field has shown proficiency in utilizing LC-MS [29].

As previously mentioned, the toxicological investigation aimed to provide a general screening for substances commonly abused, despite the challenges posed with the poor preservation of the tissues under investigation. In all eight cases tested for general acidic or basic substances, the toxicological results were negative.

However, the lack of blood or its scarcity in the investigated cadavers for direct detection of heparinic drugs necessitated the use of indirect methods based on data obtained from the available clinical documentation. In some patients (Cases 1–4), heparinemia measurement during their lifetime provided reliable data. For the remaining cases, a clinical evaluation was conducted based on known values of aPTT, TT, and RT.

These indicators are commonly used in clinical practice to assess blood coagulability and can be influenced by various clinical conditions or drug dosages. aPTT, currently the most widely used method for coagulation screening, detects deficiencies in multiple coagulation factors, including prothrombin (FII) and FX [30]. Since heparin’s biological action involves activating antithrombin (AT), which inhibits the aforementioned factors [31], aPTT serves as a first-level screening method, particularly for Unfractioned Heparins (UFHs) [32]. TT, on the other hand, is useful for detecting qualitative and quantitative fibrinogen abnormalities and is highly sensitive to the presence of heparin [33].

However, the observation of abnormal prolongation of aPTT and TT alone is not a reliable diagnostic element for heparin administration, as several clinical or pharmacological conditions can lead to a similar profile [34]. Therefore, an additional indicator, RT, was evaluated [35]. This test is highly sensitive to fibrinogen abnormalities and is not affected by anticoagulants, including heparin [36].

Exclusion of alternative factors such as oral anticoagulant therapy (OA) was achieved by monitoring the progressive normalization of the International Normalized Ratio (INR) during the hospitalization of patients receiving such therapies for their respective conditions [37].

In this context, the combination of prolonged aPTT and TT without alteration in RT was considered a highly reliable indicator of heparin administration in the investigated cases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of blood analysis conducted on patients during hospitalization.

The great advantage of this assessment lay in its applicability to all the cases involved in the investigation, rather than just the eight cases for which the bodies were available. Furthermore, the observation of indirect biological effects of heparin overdose at the time of hospital admissions provided scientifically reliable data with a high degree of certainty.

After a comprehensive evaluation of clinical, radiological, autopsy, histopathological, and toxicological data from 14 patients, it was possible to establish the causal link between heparin administration and the recorded deaths (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of clinical characteristics of cases exposed to anticoagulant administration and reconstruction of the causal link between anticoagulant administration and death.

4. Discussion

Although clinical documentation highlights hemorrhagic episodes regarding all the cases examined (of which, moreover, only 12 were characterized by clinical severity), the application of rigorous medico-legal methodology has brought to light decisive aspects.

Firstly, the outcome of the described investigations has revealed the actual necessity of careful observation of available medical documentation as the initial approach to each case, whenever it is available.

Subsequently, the exhumation of eight cadavers was the starting phase of all procedures carried out on the considered cases. In fact, it allowed the discovery of subcutaneous hemorrhagic areas in four out of eight cases, which were not only vital (Glycophorin A+) but also consistent with an iatrogenic hemorrhagic diathesis. Unfortunately, due to the poor degree of preservation of the corpses, it was not possible to observe further macroscopic phenomena attributable to bleeding caused by heparin overdose.

Similarly, the application of forensic radiological investigations was not decisive for the detection of hemorrhagic lesions or other elements relevant to the case evaluation. However, the capability of this technique to conservatively visualize numerous findings, including some elements useful for subject identification (e.g., joint or dental prostheses, presence of fracture outcomes, or absence of specific anatomical areas) or for estimating the time of death (liquefaction processes in the parenchyma, adipose degeneration, endovascular gas phenomena), has emerged strongly, confirming what is already known regarding the undeniable usefulness of such techniques for forensic purposes.

Therefore, the results obtained from PMCT in this paper must be explicated with a critical eye. On the one hand, it is crucial to interpret aspects dictated with the progression of putrefactive phenomena that could potentially be misinterpreted as pathological phenomena [38]. On the other hand, the conservative visualization of regions that are difficult to investigate during autopsy (e.g., minor blood vessels) allows for a much higher overall accuracy compared to a simple autopsy. Finally, the fundamental task of PMCT consisted in excluding other modes of death, which is of crucial importance in legal and evidentiary contexts in cases of violent causes [39].

For this reason, it is possible to affirm that the implementation of such a resource within the conducted investigations has not only demonstrated its usefulness but, above all, its standardized applicability in a forensic context.

However, the execution of autopsy investigations has proven to be even more fundamental as it allowed for the objective observation, beyond the mere findings consistent with known pathologies and hospital admissions, of the presence of subcutaneous hemorrhagic extravasations in four out of eight cases, which were not only vital (Glycophorin A+) but also compatible with an iatrogenic hemorrhagic diathesis.

Regarding the demonstration of the vitality of hemorrhagic lesions in decomposed cadavers, immunohistochemical investigation for the detection of Glycophorin is currently considered the gold standard [40,41,42]. In this sense, the present study confirms this assumption by identifying a positive reaction in all investigated areas despite a post-mortem interval (PMI) of over 1 year for all corpses [43,44].

Furthermore, the progression of putrefactive phenomena in the investigated corpses led to the almost total loss of all vital biological fluids (e.g., vitreous humor, cerebrospinal fluid, central and peripheral blood). Therefore, direct access to body cavities was necessary in order to proceed with sampling from solid organs.

Another aspect of significant interest was the interpretation of hematological investigations conducted during the individuals’ lifetime in order to identify laboratory alterations specifically related to heparin administration. Given the fundamental value that such investigations had in the overall inquiry, the present paper emphasizes the crucial importance of a multidisciplinary approach in every forensic case, but particularly in matters related to the healthcare field.

Ultimately, the execution of the presented investigations allowed for a comprehensive response to the questions posed by the judicial authority and has given a solid basis for the conduct of a judicial process that is still ongoing.

5. Conclusions

In the forensic field, the hypothesis of homicide perpetrated by healthcare personnel within care facilities constitutes an area of particular difficulty, as often the methods used to carry out the act of suppression are difficult to interpret and not unambiguous. Furthermore, the relative rarity with which such episodes come to light is significantly influenced by the presumed high rate of unreported events to the competent authorities, as they may be interpreted as natural deaths.

However, the advancement of technical–scientific knowledge constantly provides the forensic pathologist and all the physicians involved in the technical operations with new investigative methodologies to arrive at conclusions characterized by a degree of certainty. Specifically, the impossibility to proceed with cadaveric blood heparin dosing was overcome with the indirect finding of APTT and TT elevation with Reptilase Time within physiological limits, allowing the definitive establishment of a causal link between pharmacological overdose and death in 10 patients out of 14 investigated and, therefore, providing valuable data for the final judgement.

Although the scientific literature shows numerous reports on cases not dissimilar to those presented here, the complete and rigorous application of a multidisciplinary and multi-instrumental forensic approach constitutes an experience that has not been previously addressed.

For this reason, the paper’s aim is to demonstrate the effectiveness of a systematic and comprehensive approach to the examination of cases of extraordinary complexity, where a high PMI prevents the implementation of a traditional protocol based solely on autoptical and histopathological investigations [45,46,47].

In conclusion, the investigative methods illustrated here can be considered a true methodological proposal in order to establish an operational pathway, especially for future cases of violent death in the healthcare field [48,49,50,51,52]. “The pursuit of safe care as a new emerging right for patients and balancing the right to legal justice with the right to safer healthcare merit further investigation and discussion” [53].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C., E.T., G.S. and V.F.; methodology, M.S. and A.S.; validation, P.F.; data curation, N.D.F. and L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and D.M.; writing—review and editing, E.T. and V.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because judicial cases are involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is included in a legal case in Italy and for this reason it is not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABG | arterial blood gas |

| AF | atrial fibrillation |

| aPTT | Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| ARF | acute respiratory failure |

| ASA | aspirin |

| ATIII | antithrombin III |

| BNP | brain natriuretic peptide |

| BP | blood pressure |

| CABG | coronary artery bypass graft |

| CF | cardiac frequency |

| CSH | chronic subdural hematoma |

| CVC | central venous catheter |

| DIC | disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| ECG | electrocardiography |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| EDTA | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| EF | ejection fraction |

| EGD | esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| ENT | ear, nose, throat |

| HB | hemoglobin |

| HBV | Human Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCV | Human Hepatitis C Virus |

| HF | heart failure |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| LC-MS | liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LMWH | low-molecular-weight heparin |

| NSTEMI | non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| PE | pulmonary embolism |

| PEA | pulseless electrical activity |

| PEG | Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy |

| OR | operative room |

| PLT | platelets |

| PM | post mortem |

| PMCT | post-mortem computed tomography |

| PMI | post-mortem interval |

| PT | prothrombin time |

| RBC | red blood cell |

| RCP | reactive C protein |

| RT | Reptilase Time |

| SPE | solid-phase extraction |

| TEA | Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair |

| TIA | transient ischemic attack |

| TT | Thrombin Time |

| UFH | Unfractioned Heparins. |

References

- Yorker, B.C. Hospital epidemics of factitious disorder by proxy. In The Spectrum of Factitious Disorders; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, L. The Jewish Religion: A Companion, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Geppert, C. The Angel of Death in Clarksburg. Fed. Pract. 2021, 38, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorker, B.C.; Kizer, K.W.; Lampe, P.; Forrest, A.R.; Lannan, J.M.; Russell, D.A. Serial murder by healthcare professionals. J. Forensic Sci. 2006, 51, 1362–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Inspector General Veterans Health Administration care and oversight deficiencies related to multiple homicides at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center in Clarksburg, West Virginia. In Healthcare Inspection Report #20035993-140; US Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Manetti, A.C.; Visi, G.; Spina, F.; De Matteis, A.; Del Duca, F.; Turillazzi, E.; Maiese, A. Insulin and Oral Hypoglycemic Drug Overdose in Post-Mortem Investigations: A Literature Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beine, K.H. Homicides of patients in hospitals and nursing homes: A comparative analysis of case series. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2003, 26, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skopp, G. Postmortem toxicology. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2010, 6, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.A. Elder maltreatment: A review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2006, 130, 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.L.; Rodrigues Ferreira, F.E.; Neves, M.C.M.; Casaca, C.; Cunha, A.S.; Marques, J.P.; Amorim, P.; Marques, A.F.; Marques, M.I. Arsenic detection in nineteenth century Portuguese King post mortem tissues by energy-dispersive x-ray fluorescence spectrometry. X-ray Spectrom. 2002, 31, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferner, R.E. Post-mortem clinical pharmacology. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 66, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, G.L.; Salerno, S.; Terranova, M.C.; Argo, A.; Casto, A.L.; Zerbo, S.; Lagalla, R. Virtopsy and Living Individuals Evaluation Using Computed Tomography in Forensic Diagnostic Imaging. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2019, 40, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Re, G.L.; Salerno, S.; Terranova, M.C.; Argo, A.; Casto, A.L.; Zerbo, S.; Lagalla, R. Imaging features in post-mortem x-ray dark-field chest radiographs and correlation with conventional x-ray and CT. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2019, 3, 25. [Google Scholar]

- De Marco, E.; Vacchiano, G.; Frati, P.; La Russa, R.; Santurro, A.; Scopetti, M.; Guglielmi, G.; Fineschi, V. Evolution of post-mortem coronary imaging: From selective coronary arteriography to post-mortem CT-angiography and beyond. La Radiol. Medica 2018, 123, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruder, T.D.; Thali, M.J.; Hatch, G.M. Essentials of forensic post-mortem MR imaging in adults. Br. J. Radiol. 2014, 87, 20130567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thali, M.J.; Yen, K.; Schweitzer, W.; Vock, P.; Boesch, C.; Ozdoba, C.; Schroth, G.; Ith, M.; Sonnenschein, M.; Doernhoefer, T.; et al. Virtopsy, a new imaging horizon in forensic pathology: Virtual autopsy by postmortem multislice computed tomography (MSCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)--a feasibility study. J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertozzi, G.; Cafarelli, F.P.; Ferrara, M.; Di Fazio, N.; Guglielmi, G.; Cipolloni, L.; Manetti, F.; La Russa, R.; Fineschi, V. Sudden Cardiac Death and Ex-Situ Post-Mortem Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Morphological Study Based on Diagnostic Correlation Methodology. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, L.C.; Franckenberg, S.; Sieberth, T.; Schweitzer, W.; Thali, M.; Ford, J.; Decker, S. A review of visualization techniques of post-mortem computed tomography data for forensic death investigations. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 1855–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, P.M.; Gascho, D.; Schweitzer, W.; Ruder, T.D.; Berger, N.; Ross, S.G.; Thali, M.J.; Ampanozi, G. Imaging in forensic radiology: An illustrated guide for postmortem computed tomography technique and protocols. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2014, 10, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collini, F.; Andreola, S.A.; Gentile, G.; Marchesi, M.; Muccino, E.; Zoja, R. Preservation of histological structure of cells in human skin presenting mummification and corification processes by Sandison’s rehydrating solution. Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 244, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankoke, K.; Nielsen, S.S.; Jørgensen, B.M.; Jensen, H.E.; Barington, K. Immunohistochemical study of CD31 and α-SMA expression for age estimation of porcine skin wounds. J. Comp. Pathol. 2023, 206, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmeyer, R.B. Forensic Histopathology: Fundamentals and Perspectives; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fazio, N.; Delogu, G.; Ciallella, C.; Padovano, M.; Spadazzi, F.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. State-of-Art in the Age Determination of Venous Thromboembolism: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biro, C.; Kopani, M.; Kopaniova, A.; Zitnanova, I.; El-Hassoun, O.; Minoo, P.; Kolenova, L.; Sisovsky, V.; Caplovicova, M.; Stvrtina, S.; et al. Iron accumulation in human spleen in autoimmune thrombocytopenia and hereditary spherocytosis. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2012, 113, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, L.; Vignali, G.; Maffioli, E.; Tambuzzi, S.; Giaccari, R.; Mattarozzi, M.; Nonnis, S.; Milioli, M.; Franceschetti, L.; Paredi, G.; et al. Mass spectrometry-based proteomic strategy for ecchymotic skin examination in forensic pathology. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crudele, G.D.L.; Galante, N.; Fociani, P.; Del Gobbo, A.; Tambuzzi, S.; Gentile, G.; Zoja, R. The forensic application of the Glycophorin A on the Amussat’s sign with a brief review of the literature. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2021, 82, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taborelli, A.; Andreola, S.; Di Giancamillo, A.; Gentile, G.; Domeneghini, C.; Grandi, M.; Cattaneo, C. The use of the anti-Glycophorin A antibody in the detection of red blood cell residues in human soft tissue lesions decomposed in air and water: A pilot study. Med. Sci. Law 2011, 51 (Suppl. S1), S16–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Xiao, J.F.; Tuli, L.; Ressom, H.W. LC-MS-based metabolomics. Mol. BioSyst. 2012, 8, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seger, C.; Salzmann, L. After another decade: LC-MS/MS became routine in clinical diagnostics. Clin. Biochem. 2020, 82, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignjatovic, V. Activated partial thromboplastin time. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 992, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Onishi, A.; St Ange, K.; Dordick, J.S.; Linhardt, R.J. Heparin and anticoagulation. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2016, 21, 1372–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Marlar, R.A.; Clement, B.; Gausman, J. Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Monitoring of Unfractionated Heparin Therapy: Issues and Recommendations. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2017, 43, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Undas, A. Determination of Fibrinogen and Thrombin Time (TT). Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1646, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi, R.; Balasco, N.; Autiero, I.; Sica, F.; Vitagliano, L. New insight into the traditional model of the coagulation cascade and its regulation: Illustrated review of a three-dimensional view. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 7, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocas, A.; Savard, P.; Carlo, A.; Lecompte, T.; de Maistre, E. How to assess hypercoagulability in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia? Biomarkers of potential value to support therapeutic intensity of non-heparin anticoagulation. Thromb. J. 2023, 21, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karapetian, H. Reptilase time (RT). Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 992, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sapapsap, B.; Srisawat, C.; Suthumpoung, P.; Luengrungkiat, O.; Leelakanok, N.; Saokaew, S.; Kanchanasurakit, S. Safety of Vitamin K in mechanical heart valve patients with supratherapeutic INR: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e30388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartocci, G.; Santurro, A.; Neri, M.; Zaccagna, F.; Catalano, C.; La Russa, R.; Turillazzi, E.; Panebianco, V.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Post-mortem computed tomography (PMCT) radiological findings and assessment in advanced decomposed bodies. La Radiol. Medica 2019, 124, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicentin-Junior, C.A.; Vieira, R.B.; Damascena, N.P.; Silva, M.C.; Santiago, B.M.; Cunha, E.; Issa, J.P.M.; Martins-Filho, P.R.; Machado, C.E.P. Differences in ballistic findings between autopsy and post-mortem computed tomography in the head and neck region of gunshot victims: A comprehensive synthesis for forensic decision-making. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 600–603. [Google Scholar]

- Santurro, A.; Maria Vullo, A.; Borro, M.; Gentile, G.; La Russa, R.; Simmaco, M.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Personalized Medicine Applied to Forensic Sciences: New Advances and Perspectives for a Tailored Forensic Approach. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2017, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldari, B.; Vittorio, S.; Sessa, F.; Cipolloni, L.; Bertozzi, G.; Neri, M.; Cantatore, S.; Fineschi, V.; Aromatario, M. Forensic Application of Monoclonal Anti-Human Glycophorin A Antibody in Samples from Decomposed Bodies to Establish Vitality of the Injuries. A Preliminary Experimental Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, A.; Manetti, A.C.; Iacoponi, N.; Mezzetti, E.; Turillazzi, E.; Di Paolo, M.; La Russa, R.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. State-of-the-Art on Wound Vitality Evaluation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibayashi, K.; Honjyo, K.; Higashi, T.; Tsunenari, S. Differentiation of discolouration in a body by an erythrocyte membrane component, glycophorin A. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 1993, 22, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kibayashi, K.; Hamada, K.; Honjyo, K.; Tsunenari, S. Differentiation between bruises and putrefactive discolorations of the skin by immunological analysis of glycophorin A. Forensic Sci. Int. 1993, 61, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maujean, G.; Vacher, P.; Bagur, J.; Guinet, T.; Malicier, D. Forensic Autopsy of Human Decomposed Bodies as a Valuable Tool for Prevention: A French Regional Study. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2016, 37, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolliger, S.A.; Tomasin, D.; Heimer, J.; Richter, H.; Thali, M.J.; Gascho, D. Rapid and reliable detection of previous freezing of cerebral tissue by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2018, 14, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barranco, R.; Ventura, F. Immunohistochemistry in the Detection of Early Myocardial Infarction: Systematic Review and Analysis of Limitations Because of Autolysis and Putrefaction. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2020, 28, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, S.; Pomeroy, R. Italian nurse arrested over serial killings of patients. Reuters World News. 2016. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/italy-serialkiller-idINKCN0WX0KR (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Kinnell, H.G. Serial homicide by doctors: Shipman in perspective. BMJ 2000, 321, 1594–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baines, E. Italian doctors face fraud and murder charges. Lancet 2008, 371, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, D.; Aitken, C.G.G. A review of the role of roster data and evidence of attendance in cases of suspected excess deaths in a medical context. Law Probab. Risk 2002, 1, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, A. Physician as serial killer--the Shipman case. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1843–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, R.; Prineas, S.; Poli, D.; Albolino, S.; Bellandi, T.; Biancofiore, G.; Bertolini, G.; Toccafondi, G. Safety Analysis of 13 Suspicious Deaths in Intensive Care: Ergonomics and Forensic Approach Compared. J. Patient Saf. 2021, 17, e1774–e1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).