Abstract

Background and Objective: Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) is a universal standard for identifying laboratory tests and clinical observations. It facilitates a smooth information exchange between hospitals, locally and internationally. Although it offers immense benefits for patient care, LOINC coding is complex, resource-intensive, and requires substantial domain expertise. Our objective was to provide training and evaluate the performance of LOINC mapping of 20 pathogens from 53 hospitals participating in the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Methods: Complete mapping codes for 20 pathogens (nine bacteria and 11 viruses) were requested from all participating hospitals to review between January 2014 and December 2016. Participating hospitals mapped those pathogens to LOINC terminology, utilizing the Regenstrief LOINC mapping assistant (RELMA) and reported to the NNDSS, beginning in January 2014. The mapping problems were identified by expert panels that classified frequently asked questionnaires (FAQs) into seven LOINC categories. Finally, proper and meaningful suggestions were provided based on the error pattern in the FAQs. A general meeting was organized if the error pattern proved to be difficult to resolve. If the experts did not conclude the local issue’s error pattern, a request was sent to the LOINC committee for resolution. Results: A total of 53 hospitals participated in our study. Of these, 26 (49.05%) used homegrown and 27 (50.95%) used outsourced LOINC mapping. Hospitals who participated in 2015 had a greater improvement in LOINC mapping than those of 2016 (26.5% vs. 3.9%). Most FAQs were related to notification principles (47%), LOINC system (42%), and LOINC property (26%) in 2014, 2015, and 2016, respectively. Conclusions: The findings of our study show that multiple stage approaches improved LOINC mapping by up to 26.5%.

1. Introduction

Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC®) is the global standard terminology for identifying and describing laboratory examinations [1,2]. The Regenstrief Institute, a US non-profit organization, developed and has maintained LOINC since 1994, and it is currently adopted in more than 165 countries worldwide [3,4]. The adoption of LOINC in hospitals expedites the exchange of laboratory and clinical data among various information systems, providers, and individuals. The logic behind developing the LOINC code was to facilitate interoperability between systems (i.e., electronic health records (EHRs) and laboratory information systems (LISs)) for sharing laboratory results by reducing complex mapping [4,5,6]. Hospitals were previously facing immense problems sharing data locally and globally due to universally recognized and specialized terminologies before the initiation of LOINC [7,8]. Each country and hospital developed its own local codes to record laboratory test findings, which created potential challenges for laboratory test ordering as well as reporting, interpreting, comparing, and sharing [9,10,11].

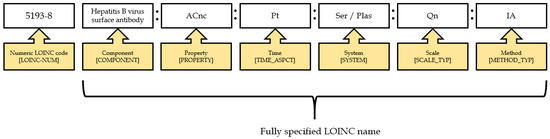

In recent decades, the scope of LOINC content has significantly increased, extending to clinical and non-clinical observations, such as vital signs, echocardiography, obstetric ultrasound, pulmonary ventilator management, Glasgow coma score, gastro-endoscopic procedures, and billing [12,13,14,15]. Taiwan has developed an electronic laboratory reporting (ELR) system and adopted and used standardized terminologies since 2006. Liu et al. [16] reported that the mapping ratio of the national health insurance (NHI) codes to LOINC codes was low (17%) and that the NHI codes were too generic (imprecise) to map exactly to the LOINC codes. Appropriate coding from NHI codes to LOINC codes requires support from both physicians and laboratory technologists, which is labor intensive and could hamper the performance of current operating procedures. However, Lee et al. [17] developed a multi-part matching strategy algorithm to improve mapping quality and reduce manual efforts. The performance of the automated model was better than the Regenstrief LOINC Mapping Assistant (RELMA) and Lab Auto Mapper (LAM) in terms of recall (86% vs. 78%) and precision (75% vs. 69%). There are several challenges when mapping Taiwanese local codes to LOINC codes, including completeness (insufficient information), coding variance (use of different LOINC codes for the same test), correctness (lack of LOINC terminology knowledge), local issues (too many codes for specimens and methodology), and literacy of standardized terminology (lack of LOINC expertise). According to the LOINC naming convention, every laboratory test name is composed of six parts: component, property, timing, system, scale, and method (Figure 1) [18].

Figure 1.

An example of a LOINC name and code.

Several studies have already suggested possible ways to overcome LOINC mapping. Lin et al. [19] suggested using more specific naming conventions for local descriptions, providing better training, and developing automated mapping tools. Dixon et al. [20] highlighted the importance of developing enhanced RELMA functions, mapping local terms to LOINC codes effectively. There are few previous studies that describe the process of mapping local test names to LOINC in detail. The objective of our study was to improve LOINC mapping quality, which is separated into three specific aims: (1) to improve LOINC mapping performance in the ELR system through training; (2) to analyze the local codes and standardize the mapping patterns or characteristics for 20 pathogens; and (3) to describe the local issues for requesting new LOINC codes for coverage of pathogen terms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Background

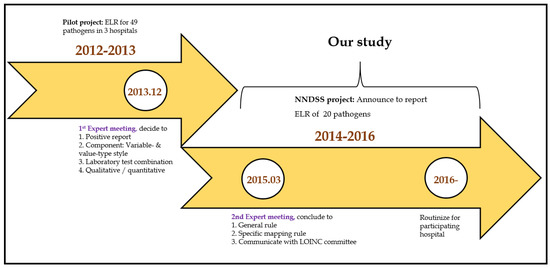

In 2012, the Taiwan Center for Disease Control (TCDC) conducted a pilot study to investigate how to implement ELR in Taiwan. A total of 49 pathogens’ data were collected from three hospitals and utilized RELMA for LOINC mapping. The primary objectives were: (1) to develop a LOINC mapping tool for 49 pathogens, which could reduce the burden of the LOINC mapping process; (2) to hold a training course to improve the mapping consistency; (3) to standardize the laboratory tests results using the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) for analysis; (4) to manage the mapping table of local codes to LOINC codes for version updates (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Timeline for NNDSS.

In 2013, the TCDC organized a meeting of experts to decide how to map local laboratory test codes to the LOINC terminology. All experts provided suggestions to: (a) establish a validation cycle for LOINC mapping; (b) collect positive laboratory results for reportable diseases as specified by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); (c) take note of the difference of variable- and value-type styles; and (d) include all laboratory tests combinations for a specific condition (notifiable disease) and all the laboratory tests results as narrative or numerical data.

2.2. Development of the NNDSS Study Plan

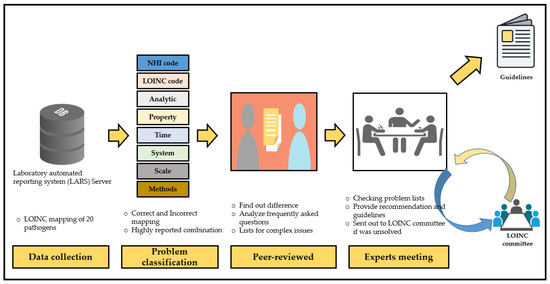

The TCDC again organized a meeting of experts, consisting of medical informaticians, laboratory experts, and CDC specialists to set general goals for encouraging and improving LOINC mapping (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The entire process of the NNDSS project.

In the strategy meeting, we decided on a multi-stage approach to implement NNDSS. Using this approach, we can observe or estimate the general condition in different types of hospitals, such as public, private, centers, regional, district, and affiliated hospitals. We gradually invited the nationwide representative hospitals first, and the regional hospital were in the second choice. Afterward, we invited the branches of hospitals, which are part of a multi-hospital system.

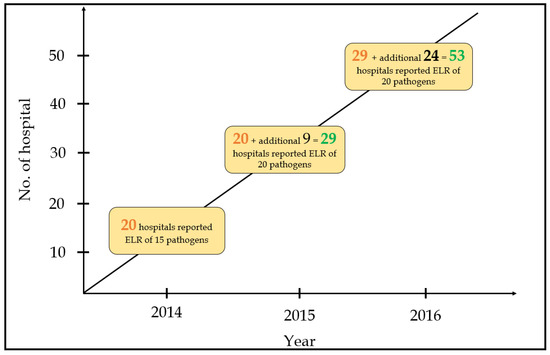

The NNDSS project started in 2014 with 20 hospitals. Financial support was proposed to all participating hospitals (Supplementary Table S1), who were requested to use LOINC codes for notification of 20 pathogens, including nine bacteria and 11 viruses. Regarding bacteria, the TCDC mainly focused on tuberculosis, childhood diseases, and zoonotic foodborne diseases. Concerning viruses, the TCDC focused on influenza, chronic hepatitis, and childhood illnesses. In 2015, another nine hospitals participated in the NNDSS and reported LOINC codes for 20 pathogens. Ultimately, an additional 22 hospitals joined the NNDSS and reported LOINC codes for 20 pathogens (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of hospitals and reported pathogens during the three-year study period.

2.2.1. Data Collection and Problems Classification

Data were collected from all participating hospitals, including data reported concerning viral hepatitis, mycobacterium, antigen or antibody tests for non-mycobacterium, antigen or antibody tests for non-viral hepatitis, and viral/bacterial cultures. The mapping problems were identified by reviewers and classified as correct and incorrect mapping, similar to the LOINC System in incorrect terms. The reviewers also took the necessary steps to correct problem lists. They evaluated reported data based on the following criteria:

- (a)

- Correctness—Each part matched to the original meaning of the test based on LOINC’s six parts;

- (b)

- Usefulness—Mapped with suitable LOINC codes for those tests;

- (c)

- Completeness—All required information was accurately represented in the mapping of the tests;

- (d)

- Consistency—Ensured all of the laboratory test combinations had their unique meaning.

2.2.2. Peer Review

Experts reviewed the mapping differences of those cases and suggested how to correct them. The expert panel consisted of LOINC specialists:

- (a)

- Medical informaticians: LOINC experts who were familiar with the six axes (component, property, time, system, scale, and method) of the LOINC model and suggested the LOINC mapping rule, e.g., LOINC for a manual count of white blood cells in cerebral spinal fluid specimen is presented by LOINC code 806-0 (Leukocytes: NCnc: Pt: CSF: Qn: Manual count). Here is the breakdown of the fully specified name for LOINC code 806-0—component: Leukocytes, property: NCnc (number concentration), time: Pt (point in time), system (specimen): CSF (cerebral spinal fluid), scale: Qn (quantitative), method: manual count (Supplementary Table S1).

- (b)

- Laboratory experts: Medical technologists who understand the laboratory tests meaning in the clinical laboratory and clarify the test terms in the laboratory information system, e.g., in HBsAg, they use the serum to analyze, but they use “Blood” in the LIS.

- (c)

- Officials from the TCDC: TCDC specialists who established the NNDSS reporting rules and collected the laboratory test data of disease notifications from all large hospitals in Taiwan, e.g., in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, they collected the positive reports of the acid-fast stains, which are used as the preliminary mycobacterium culture for the purpose of prevention.

2.2.3. Consensus Formation

Recommendations were provided based on the summary of errors report (Table 1). First, proper and meaningful suggestions were given for the error pattern in the frequently asked questions (FAQs). Second, a meeting was organized if the error pattern seemed to be more complicated to resolve. Third, if experts were unable to determine the local issue error pattern, we requested the LOINC committee to examine the problems (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Notification conditions list.

3. Results

3.1. Homegrown vs. Outsourcing

There were 53 hospitals included in our study. Of these 53 hospitals, 26 (49%) used homegrown (local laboratory people did the mapping) LOINC mapping and 27 (51%) used outsourced LOINC mapping. There were no statistically significant differences in LOINC mapping between homegrown and outsourced (82.6% vs. 82.0%) (Table 2). In the homegrown system, the participants who joined the project in 2016 (early participants), mapped LOINC codes more than the participants who joined the project between 2014 and 2015 (late participants) (91.3% vs. 80.0%). Moreover, the performance of LOINC mapping in early participants was greater than the late participants while using outsourcing (84.9% vs. 76.3%). Three (A, B, C) out of six vendors provided most of the outsourcing (Supplementary Table S2). Table 2 shows the LOINC mapping completeness from two difference sources.

Table 2.

Performance of LOINC mapping in homegrown and outsourced systems.

3.2. Performance Evaluation

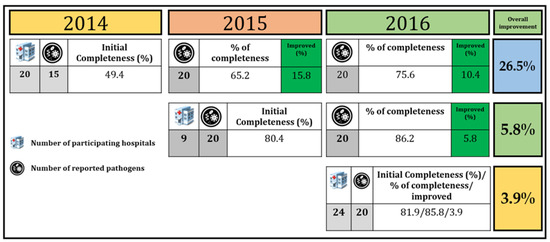

We evaluated the performance of LOINC mapping each year. Hospitals that joined the project in 2014 had improvements in LOINC mapping by 26.5% compared to hospitals that joined in 2015 and 2016 (5.8 and 3.9%, respectively) (Figure 5). Hospitals that joined earlier had more significant improvement than hospitals that joined later. This is because they received more suggestions and continuous feedback from experts to improve their LOINC coding.

Figure 5.

LOINC mapping performance comparison among 53 hospitals.

3.3. Experience vs. Inexperience

Participants who had previous user experience in LOINC coding showed greater completeness than participants who had no experience in LOINC coding (Table 3). There was a statistically significant difference in LOINC mapping completeness between groups (Mann–Whitney U test: p-value = 0.037).

Table 3.

Rate of LOINC mapping completeness based on experience.

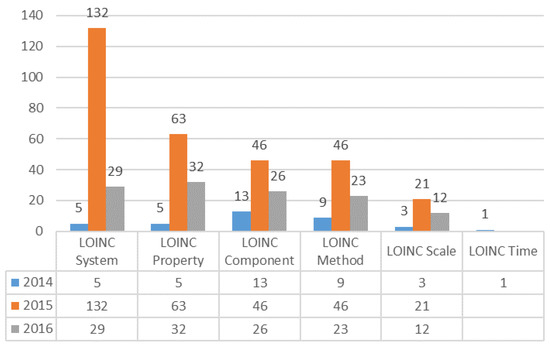

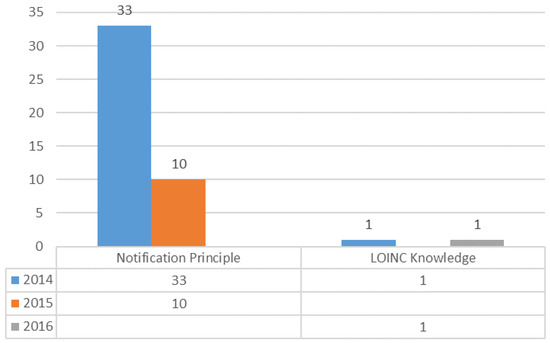

3.4. Analyses of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

We collected the questions concerning LOINC coding difficulties during the three year study period and grouped them into three categories: notification principle, LOINC knowledge, and LOINC domain (component, property, time, system, scale, method). In 2014, there were 70 questions reported in the ELR. The main issues were about the notification principle (47%), which is related to reported format, laboratory result presentations, and ways to present the results. In 2015, the number of FAQs had increased to 318 and a higher number of questions were related to the LOINC System (42%). In 2016, 123 questions concerned LOINC mapping, and all questions were related to LOINC domains, such as LOINC property (26%), LOINC system (23%), LOINC component (21%), and LOINC method (19%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Analysis of frequently asked questions (FAQs) regarding LOINC mapping.

3.5. Evaluation and Suggestions for LOINC Mapping

The evaluation of LOINC mapping was classified into three steps: (a) implementation of ELR; (b) audit of LOINC mapping; and (c) evaluated reported data (Table 4). We categorized LOINC mapping error into different types of items. Finally, we suggested LOINC mapping guidelines based on those errors. For example, to participants who had general errors by design (variable-style names or value-style names) and specific topic issues for each disease, i.e., the rapid influenza immunoassay for the diagnosis of influenza virus A and B, we suggested to the mapping of LOINC 72367-6. For the test for group B streptococcus in women 35 to 37 weeks pregnant, we suggested users map LOINC 72607-5.

Table 4.

Suggestions for LOINC mapping problems.

Finally, we checked the accuracy of mapping and compared previous mappings to new mappings (Table 5). We observed several codes affected when participants migrated LOINC Version 2.50 to 2.64. We noticed some axes were changed instead of creating a new LOINC code (old codes were deprecated). Some laboratory tests were mapped to LOINC code with no suitable axes. In order to retian consistency, our guidelines suggested some laboratory tests to map fixed axes with no LOINC code in temporary.

Table 5.

Compression of mapping performance before and after project.

4. Discussion

In our study, we assessed the LOINC mapping performance for 20 pathogens in 53 hospitals in Taiwan and provided mapping suggestions for the error pattern in the FAQs. The findings of our study show that mapping performance increased by up to 26.5%; however, there were no significant differences in LOINC mapping between homegrown and outsourcing (82.6% vs. 82.0%). It was also notable that the mapping rate was higher among the hospitals with previous experience of LOINC coding than that of inexperienced hospitals. The most frequently asked question in 2014 was associated with notification principles; LOINC system and LOINC domain related questions were asked about more in 2015 and 2016, respectively (Table 6). Our study also shows that suggestions from experts and training courses lead to more consistent use of LOINC codes with less complexity and more accuracy.

Table 6.

Experts’ responses related to FAQs.

Until now, most hospitals have used their own local and idiosyncratic codes to identify laboratory tests [21]. For example, one hospital would record and identify serum sodium with the code “C1231” and another hospital with the code “SNA” [9]. Each hospital has its own unique code for each laboratory test, which always makes it difficult to exchange information between hospitals. LOINC has provided a universal identifier for each test and has provided multiple opportunities to map laboratory tests [22]. LOINC was initially developed more than 20 years ago and approximately 36,000 registered users from more than 165 countries are using it, and many countries have officially adopted it as a national standard [23,24].

Despite the benefits of using LOINC codes for laboratory test records and exchange, mapping local terms to standard terminologies such as LOINC is complex and labor intensive [25,26,27,28]. Appropriate mapping with LOINC depends on domain knowledge and knowledge of the target vocabulary standard. Although laboratory technologists and physicians always have a good knowledge of laboratory tests, they may lack the knowledge of how to map local laboratory test codes to LOINC codes [4,29,30,31]. Moreover, local test coding has always lacked information to successfully map all laboratory tests to standard terminology [32]. Previous studies developed various algorithms to automatically map local codes to LOINC codes with great efficiency and minimum human effort [33,34,35].

Even though automatic tools can help transform local test codes to standard terminology, expert human review is still needed to solve complex issues. In our project, we used multiple approaches, including automated tools plus human expert suggestions, to correctly map 20 pathogens. The findings of our study showed that most of the hospitals faced LOINC System related problems. We analyzed all FAQs, categorized problems, suggested how to map accurately, and provided guidelines. In this process, we observed an improvement in LOINC mapping over time, especially in those hospitals who joined earlier. Indeed, our model helped develop a common infrastructure to increase the adaption of LOINC coding and reduce the technical barriers to implementing interoperability standards. All the participating hospitals used standardized vocabulary to identify laboratory tests; therefore, information exchange among hospitals would be bi-directional, improve scalability, and facilitate data compilation and access to patients’ longitudinal data. Furthermore, nationwide adoption of LOINC codes will help to reduce healthcare costs and improve quality of care by reducing erroneous and duplicate laboratory tests.

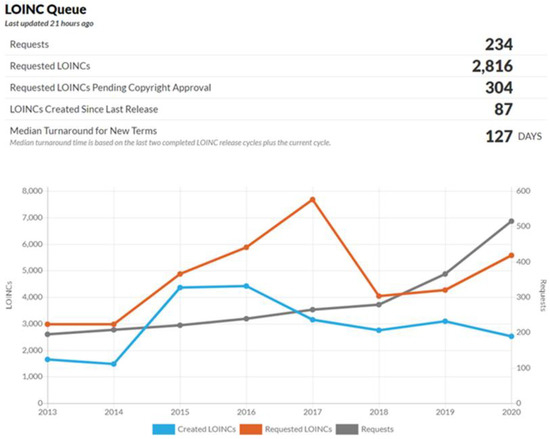

Regenstrief has started updating LOINC and releasing it twice per year since 2010. LOINC has already increased to nearly 95,000 terms (laboratory terms: 57,817; clinical terms: 37,078) in their current version, which is approximately a 1.6-fold increase in the last decade. Regenstrief has also designed a system for requesting new terms or changes to the existing LOINC contents (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Frequency of LOINC additions.

Over the study period, we taught clinicians and laboratory personnel how to use the updated LOINC terms. Taiwan’s NNDSS continues its work, and TCDC has added coronavirus as a reportable pathogen as of November 2020. To date, the participants include 63 hospitals, 20 medical centers, and 43 regional hospitals or district hospitals.

Strengths: Our study has several strengths. First, this was a nation-wide LOINC mapping project and evaluated the performance of LOINC mapping for 20 pathogens. Second, the performance of LOINC mapping improved significantly by using our multi-stage approach. Third, we provided new guidelines for LOINC mapping and solved complex LOINC mapping problems through discussion with the LOINC committee.

Limitations: Our study has several limitations that need to be addressed. First, our study included a limited number of hospitals and pathogens. However, more hospitals and pathogens have been included in the second phase of this project. Second, the use of LOINC mapping cannot provide guarantee for uniform interoperability of laboratory tests names and codes between different information systems, and our current study did not evaluate the feasibility of LOINC coding. Third, the challenges of LOINC mapping are geographically and chronologically diverse; mapping improvement through our model may not be representative of other health care systems.

Future work: The demand has been raised for health information exchange between interdepartmental in the same hospital or other hospitals to improve quality by sharing patients’ clinical information. In our current study, we only focused on the LOINC coding of 20 pathogens. In the future, we will focus on including more pathogens and managing new diseases such as COVID-19. Moreover, we will try to focus on profiling the microbiology data in FHIR for infection control, integrating biological results with other health information systems, and implementing existing standards in clinical data to support research. Finally, we will investigate the usability of LOINC, particularly with respect to its perceived benefits (e.g., interoperability, secondary data analysis).

5. Conclusions

Mapping local codes to standard terminology is always difficult, labor intensive, and requires domain expertise. However, it is important to exchange information among various departments in the same hospital or different hospitals. Our multi-stage approach improved LOINC mapping performance and provided guidelines that could help adoption of a new version in near future.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics11091564/s1. Table S1: Description of LOINC six axes; Table S2: Inceptive provided by government.

Author Contributions

Investigation and validation, C.-Y.Y., S.-J.P., H.C.Y., C.-Y.H., H.-C.C. and M.-C.L.; data curation, C.-Y.Y., S.-J.P., H.C.Y., M.I., T.N.P. and M.-C.L.; writing—original-draft preparation, C.-Y.Y., T.N.P. and H.-C.C.; writing—review and editing M.I. and S.M.H.; supervision, H.-C.C. and M.-C.L.; funding acquisition, C.-Y.H. and M.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (grant number 108-2314-B-038-053-MY3) to M.-C.L., Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (grant number 103-CDC-C-114-000801) to C.-Y.Y., and Taipei Medical University, Taiwan (grant numbers 103-AE1-B26, 108-FRP-02) to M.-C.L.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Taiwan Center for Disease Control for providing the data used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Uchegbu, C.; Jing, X. The potential adoption benefits and challenges of LOINC codes in a laboratory department: A case study. Heal. Inf. Sci. Syst. 2017, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Griffith, S.P.; Moore, C.; Russell, D.; Rosario, J.A.C.; Bertolli, J. Standardizing Laboratory Data by Mapping to LOINC. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006, 13, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenreider, O.; Cornet, R.; Vreeman, D.J. Recent Developments in Clinical Terminologies—SNOMED CT, LOINC, and RxNorm. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2018, 27, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.; Shapiro, J.S.; Melton, G.; Schlegel, C.; Stetson, P.D.; Johnson, S.B.; Bakken, S. Iterative Evaluation of the Health Level 7--Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes Clinical Document Ontology for Representing Clinical Document Names: A Case Report. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2009, 16, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stram, M.; Gigliotti, T.; Hartman, D.; Pitkus, A.; Huff, S.M.; Riben, M.; Henricks, W.H.; Farahani, N.; Pantanowitz, L. Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes for Laboratorians. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019, 144, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, W.S.; Karlsson, D.; Vreeman, D.J.; Lazenby, A.J.; Talmon, G.A.; Campbell, J.R. A computable pathology report for precision medicine: Extending an observables ontology unifying SNOMED CT and LOINC. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiebeck, J.; Gietzelt, M.; Ballout, S.; Christmann, M.; Fradziak, M.; Laser, H.; Ruppel, J.; Schönfeld, N.; Teppner, S.; Gerbel, S. Implementing LOINC-Current Status and Ongoing Work at a Medical University. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 267, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, H.M.; Helhorn, A.; Phan-Vogtmann, L.A.; Palm, J.; Thomas, E.; Iffland, A.; Heidel, A.; Müller, S.; Saleh, K.; Krohn, K. Integration of allergy documentation into an interoperable archiving and communication platform to improve patient care and clinical research at the Jena University Hospital. GMS Med. Inform. Biom. Epidemiol. 2021, 17, Doc06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.J.; Huff, S.M.; Suico, J.G.; Hill, G.; Leavelle, D.; Aller, R.; Forrey, A.; Mercer, K.; DeMoor, G.; Hook, J.; et al. LOINC, a Universal Standard for Identifying Laboratory Observations: A 5-Year Update. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrey, A.W.; Mcdonald, C.J.; DeMoor, G.; Huff, S.M.; Leavelle, D.; Leland, D.; Fiers, T.; Charles, L.; Griffin, B.; Stalling, F. Logical observation identifier names and codes (LOINC) database: A public use set of codes and names for electronic reporting of clinical laboratory test results. Clin. Chem. 1996, 42, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, A.K.; Bixho, I.; Goonan, E.M.; Bates, D.W.; Shaykevich, S.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Landman, A.B.; Tanasijevic, M.J.; Melanson, S.E.F. The Benefits and Challenges of an Interfaced Electronic Health Record and Laboratory Information System: Effects on Laboratory Processes. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2017, 141, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, S.M.; Rocha, R.A.; McDonald, C.J.; De Moor, G.J.E.; Fiers, T.; Bidgood, W.D.; Forrey, A.W.; Francis, W.G.; Tracy, W.R.; Leavelle, D.; et al. Development of the Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes (LOINC) Vocabulary. J. Am. Med Inform. Assoc. 1998, 5, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, S.; Cimino, J.J.; Haskell, R.; Kukafka, R.; Matsumoto, C.; Chan, G.K.; Huff, S.M. Evaluation of the Clinical LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes) Semantic Structure as a Terminology Model for Standardized Assessment Measures. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2000, 7, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- White, T.M. Extending the LOINC Conceptual Schema to Support Standardized Assessment Instruments. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2002, 9, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.J.; Park, H.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, H.S. Application of Standard Terminologies for the Development of a Customized Healthcare Service based on a PHR Platform. J. Multimed. Inf. Syst. 2019, 6, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-T.; Hsu, M.-H.; Wang, L.-W.; Wen, L.-L.; Lai, J.-S. A Unified Approach to Adoption of Laboratory LOIN in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the 2007 9th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Application and Services, Taipei, Taiwan, 19–22 June 2007; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.-H.; Groß, A.; Hartung, M.; Liou, D.-M.; Rahm, E. A multi-part matching strategy for mapping LOINC with laboratory terminologies. J. Am. Med Inform. Assoc. 2014, 21, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kim, H.; El-Kareh, R.; Goel, A.; Vineet, F.; Chapman, W. An approach to improve LOINC mapping through augmentation of local test names. J. Biomed. Inform. 2012, 45, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.C.; Vreeman, D.J.; McDonald, C.J.; Huff, S.M. A Characterization of Local LOINC Mapping for Laboratory Tests in Three Large Institutions. Methods Inf. Med. 2011, 50, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, B.E.; Hook, J.; Vreeman, D.J. Learning from the Crowd in Terminology Mapping: The LOINC Experience. Lab. Med. 2015, 46, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chen, E.S.; Melton, G.B.; Engelstad, M.E.; Sarkar, I.N. Standardizing clinical document names using the HL7/LOINC document ontology and LOINC codes. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 13–17 November 2010; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2010; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Baorto, D.M.; Cimino, J.J.; Parvin, C.A.; Kahn, M.G. Using Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes (LOINC) to exchange laboratory data among three academic hospitals. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Fall Symposium, Nashville, TN, USA, 1 January 1997; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1997; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, Y.; Dong, X.; Duke, J.; Natarajan, K.; Hripcsak, G.; Shah, N.; Banda, J.M. Normalizing Clinical Document Titles to LOINC Document Ontology: An Initial Study. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium, Virtual Event, USA, 14–18 November 2020; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020; p. 1441. [Google Scholar]

- Bietenbeck, A.; Boeker, M.; Schulz, S. NPU, LOINC, and SNOMED CT: A comparison of terminologies for laboratory results reveals individual advantages and a lack of possibilities to encode interpretive comments. J. Lab. Med. 2018, 42, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabutsch, S.; Weigl, G. Using HL7 CDA and LOINC for standardized laboratory results in the Austrian electronic health rec-ord. J. Lab. Med. 2018, 42, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, N.; Do, N.; Brophy, M.; Zimolzak, A. Interactive Machine Learning for Laboratory Data Integration. MedInfo 2019, 264, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Shin, S.-Y.; Kang, M.; Yi, B.-K.; Chang, D.K. Developing a Standardization Algorithm for Categorical Laboratory Tests for Clinical Big Data Research: Retrospective Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2019, 7, e14083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Chi, C.; Huang, B.; Meng, H.; Yu, J.; Zhao, D. CrowdMapping: A Crowdsourcing-Based Terminology Mapping Method for Medical Data Standardization. Stud. Heal. Technol. Inform. 2017, 245, 511–515. [Google Scholar]

- Baorto, D.M.; Cimino, J.; A Parvin, C.; Kahn, M.G. Combining laboratory data sets from multiple institutions using the logical observation identifier names and codes (LOINC). Int. J. Med Inform. 1998, 51, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.C.; Glasgow, M.; Narus, S.P.; Clayton, P.D. Using LOINC to link an EMR to the pertinent paragraph in a structured reference knowledge base. In Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium, San Antonio, TX, USA, 9–13 November 2002; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002; p. 652. [Google Scholar]

- Heras, Y.Z.; Mitchell, J.A.; Williams, M.S.; Brothman, A.R.; Huff, S.M. Evaluation of LOINC for representing constitutional cytogenet-ic test result reports. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium, San Francisco, CA, USA, 14–18 November 2009; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2009; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Kopanitsa, G. Application of a Regenstrief RELMA V.6.6 to Map Russian Laboratory Terms to LOINC. Methods Inf. Med. 2016, 55, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-H.; Chen, H.-K.; Hsu, M.-H.; Wang, H.-C.; Yeh, Y.-T. Cloud Computing for Infectious Disease Surveillance and Control: Development and Evaluation of a Hospital Automated Laboratory Reporting System. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunner, C.; Bürkle, T.; Prokosch, H.-U.; Ganslandt, T. Mapping local laboratory interface terms to LOINC at a German university hospital using RELMA V.5: A semi-automated approach. J. Am. Med Inform. Assoc. 2013, 20, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, L.M.; Johnson, K.; Monson, K.; Lam, S.H.; Huff, S.M. A method for the automated mapping of laboratory results to LOINC. In Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 4–8 November 2000; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2000; p. 472. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).