Differential Time-of-Day Effects of Caffeine Capsule and Mouth Rinse on Cognitive Performance in Adolescent Male Volleyball Athletes: A Randomized Crossover Investigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

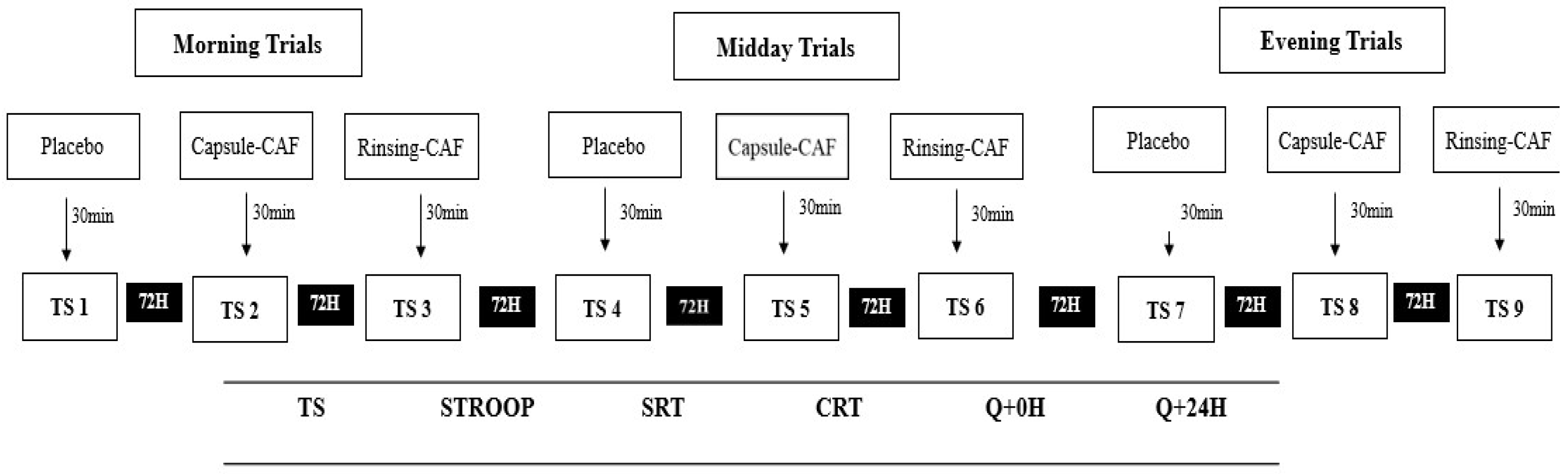

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Supplementation Protocols

2.4. Cognitive Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Oral Temperature

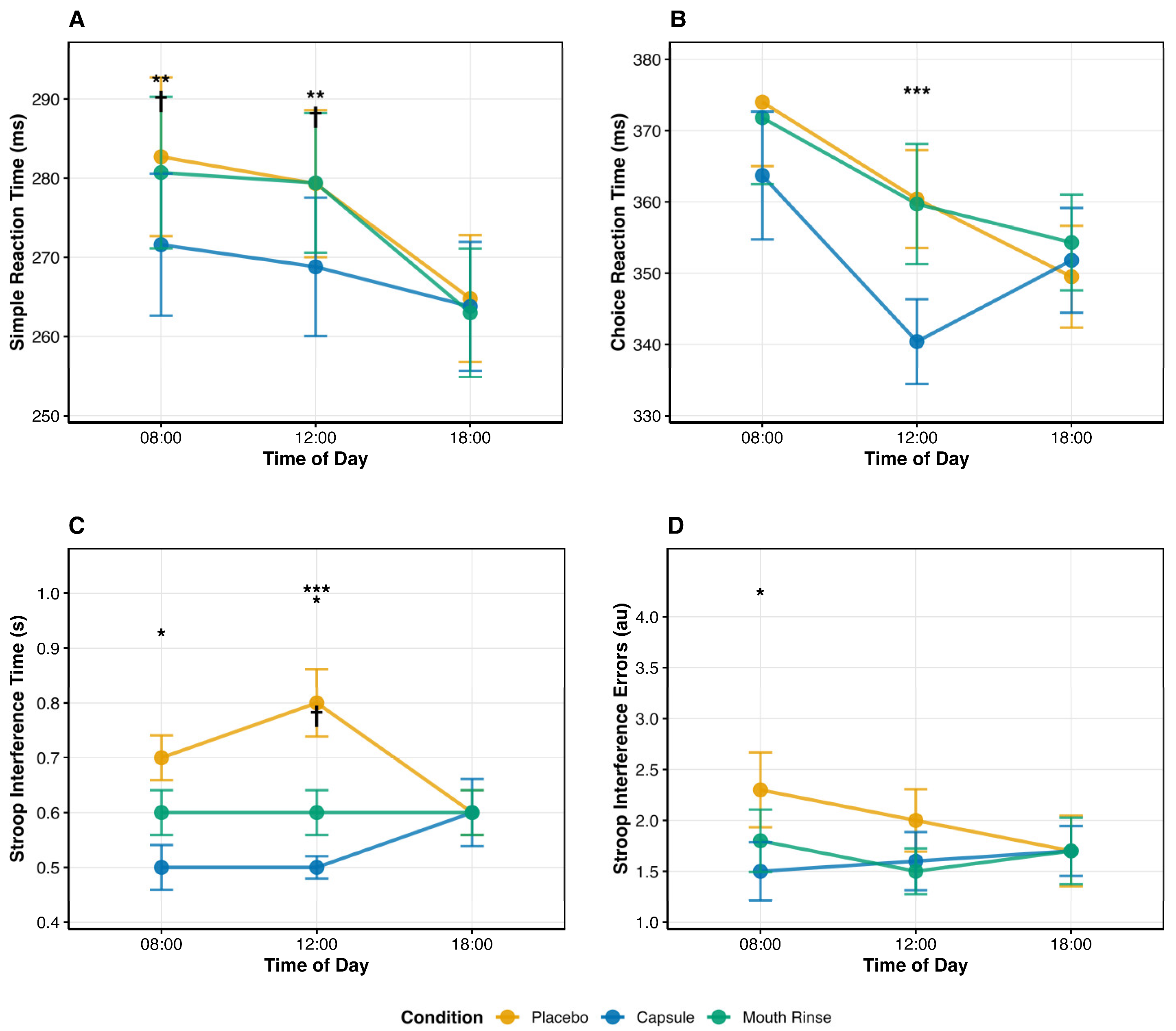

3.2. Simple Reaction Time (SRT)

3.3. Choice Reaction Time (CRT)

3.4. Stroop Interference Time

3.5. Stroop (Interference)—Errors

3.6. Side Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guest, N.S.; VanDusseldorp, T.A.; Nelson, M.T.; Grgic, J.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Jenkins, N.D.M.; Arent, S.M.; Antonio, J.; Stout, J.R.; Trexler, E.T.; et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Caffeine and exercise performance. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, C.; Grgic, J. Caffeine and Exercise: What Next? Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1007–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo Calvo, J.; Fei, X.; Domínguez, R.; Pareja-Galeano, H. Caffeine and Cognitive Functions in Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredholm, B.B.; Bättig, K.; Holmén, J.; Nehlig, A.; Zvartau, E.E. Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999, 51, 83–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbély, A.A. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum. Neurobiol. 1982, 1, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Chtourou, H.; Souissi, N. The effect of training at a specific time of day: A review. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 1984–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, Y.; Souissi, M.; Chtourou, H. Effects of caffeine ingestion on the diurnal variation of cognitive and repeated high-intensity performances. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2019, 177, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougrine, H.; Ammar, A.; Salem, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Jahrami, H.; Chtourou, H.; Souissi, N. Optimizing Short-Term Maximal Exercise Performance: The Superior Efficacy of a 6 mg/kg Caffeine Dose over 3 or 9 mg/kg in Young Female Team-Sports Athletes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougrine, H.; Nasser, N.; Abdessalem, R.; Ammar, A.; Chtourou, H.; Souissi, N. Pre-Exercise Caffeine Intake Attenuates the Negative Effects of Ramadan Fasting on Several Aspects of High-Intensity Short-Term Maximal Performances in Adolescent Female Handball Players. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin-Guichard, D.; Laflamme, V.; Julien, A.S.; Trottier, C.; Grondin, S. Decision-making and dynamics of eye movements in volleyball experts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trecroci, A.; Duca, M.; Cavaggioni, L.; Rossi, A.; Scurati, R.; Longo, S.; Merati, G.; Alberti, G.; Formenti, D. Relationship between Cognitive Functions and Sport-Specific Physical Performance in Youth Volleyball Players. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, S.; Guelfi, K.J.; Fournier, P.A. Mouth rinsing and ingesting a bitter solution improves sprint cycling performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 1648–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlert, A.M.; Twiddy, H.M.; Wilson, P.B. The Effects of Caffeine Mouth Rinsing on Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Sport. Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2020, 30, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, W.F.; Lopes-Silva, J.P.; Camati Felippe, L.J.; Ferreira, G.A.; Lima-Silva, A.E.; Silva-Cavalcante, M.D. Is caffeine mouth rinsing an effective strategy to improve physical and cognitive performance? A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, K.A.; Spriet, L.L. Administration of Caffeine in Alternate Forms. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doering, T.M.; Fell, J.W.; Leveritt, M.D.; Desbrow, B.; Shing, C.M. The effect of a caffeinated mouth-rinse on endurance cycling time-trial performance. Int. J. Sport. Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraftabi, H.; Ghorbani, H.; Souzandeh, P.; Berjisian, E.; Naderi, A.; Mojtahedi, S.; Kerksick, C. The Effects of Caffeine Mouth Rinsing During the Battery of Soccer-Specific Tests in the Trained Male Soccer Players: Fasted Versus Fed State. Int. J. Sport. Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2025, 35, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Tottenham, N.; Liston, C.; Durston, S. Imaging the developing brain: What have we learned about cognitive development? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.J.; Acebo, C.; Carskadon, M.A. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007, 8, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carskadon, M.A. Sleep in adolescents: The perfect storm. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 58, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J.A.; Mindell, J.; Baylor, A. Effect of energy drink and caffeinated beverage consumption on sleep, mood, and performance in children and adolescents. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougrine, H.; Ammar, A.; Salem, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Jahrami, H.; Chtourou, H.; Souissi, N. Effects of Various Caffeine Doses on Cognitive Abilities in Female Athletes with Low Caffeine Consumption. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougrine, H.; Ammar, A.; Salem, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Żmijewski, P.; Jahrami, H.; Chtourou, H.; Souissi, N. Effects of Different Caffeine Dosages on Maximal Physical Performance and Potential Side Effects in Low-Consumer Female Athletes: Morning vs. Evening Administration. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tassi, P.; Muzet, A. Sleep inertia. Sleep Med. Rev. 2000, 4, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougrine, H.; Cherif, M.; Chtourou, H.; Souissi, N. Can caffeine supplementation reverse the impact of time of day on cognitive and short-term high intensity performances in young female handball players? Chronobiol. Int. 2022, 39, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.K.; Lawson, S.C.; Tonkin, S.S.; Ziegler, A.M.; Temple, J.L.; Hawk, L.W. Caffeine enhances sustained attention among adolescents. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 29, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, A.; Almirall, H. Horne & Östberg morningness-eveningness questionnaire: A reduced scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohet, K.L.; Landrum, R.E. Caffeine consumption questionnaire: A standardized measure for caffeine consumption in undergraduate students. Psychol. Rep. 2001, 89, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip-Stachnik, A.; Krzysztofik, M.; Del Coso, J.; Wilk, M. Acute effects of two caffeine doses on bar velocity during the bench press exercise among women habituated to caffeine: A randomized, crossover, double-blind study involving control and placebo conditions. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, F.; Nagy, G.P. The random generation of Latin rectangles based on the assignment problem. Discret. Appl. Math. 2026, 378, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilditch, C.J.; McHill, A.W. Sleep inertia: Current insights. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2019, 11, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonati, M.; Latini, R.; Galletti, F.; Young, J.F.; Tognoni, G.; Garattini, S. Caffeine disposition after oral doses. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1982, 32, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaven, C.M.; Maulder, P.; Pooley, A.; Kilduff, L.; Cook, C. Effects of caffeine and carbohydrate mouth rinses on repeated sprint performance. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 38, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karayigit, R.; Ali, A.; Rezaei, S.; Ersoz, G.; Lago-Rodriguez, A.; Domínguez, R.; Naderi, A. Effects of carbohydrate and caffeine mouth rinsing on strength, muscular endurance and cognitive performance. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K. The Acute Effects of Caffeine Consumption on Muscle Performance of a 1 Rep Max Bench Press Exercise: A Critically Appraised Topic; Liberty University: Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajadi-Ernazarova, K.R.; Hamilton, R.J. Caffeine Withdrawal; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Facer-Childs, E.R.; Boiling, S.; Balanos, G.M. The effects of time of day and chronotype on cognitive and physical performance in healthy volunteers. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnilari, M.; Bommasamudram, T.; Easow, J.; Tod, D.; Varamenti, E.; Edwards, B.J.; Ravindrakumar, A.; Gallagher, C.; Pullinger, S.A. Diurnal variation in variables related to cognitive performance: A systematic review. Sleep Breath. 2024, 28, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, D.; Gupta, C.; Vincent, G.; Vandelanotte, C.; Duncan, M.; Tucker, P.; Di Milia, L.; Ferguson, S.A. The relationship between circadian type and physical activity as predictors of cognitive performance during simulated nightshifts: A randomised controlled trial. Chronobiol. Int. 2025, 42, 736–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroop, J.R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1935, 18, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.B.; Ruan, S.J.; Zhang, K.; Bao, Q.; Liu, H.Z. Time pressure effects on decision-making in intertemporal loss scenarios: An eye-tracking study. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1451674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broodryk, A.; Skala, F.; Broodryk, R. Light-Based Reaction Speed Does Not Predict Field-Based Reactive Agility in Soccer Players. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, C.M. Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 109, 163–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, T.M.; Caldwell, J.A.; Lieberman, H.R. A review of caffeine’s effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, S.; Piacentino, D.; Sani, G.; Aromatario, M. Caffeine: Cognitive and physical performance enhancer or psychoactive drug? Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015, 13, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell-Ramsay, C.F.; Jackson, P.A.; Forster, J.S.; Dodd, F.L.; Bowerbank, S.L.; Kennedy, D.O. The Acute Effects of Caffeinated Black Coffee on Cognition and Mood in Healthy Young and Older Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.P., Jr.; Hull, J.T.; Czeisler, C.A. Relationship between alertness, performance, and body temperature in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002, 283, R1370–R1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, C.A.; Kronauer, R.E.; Allan, J.S.; Duffy, J.F.; Jewett, M.E.; Brown, E.N.; Ronda, J.M. Bright light induction of strong (type 0) resetting of the human circadian pacemaker. Science 1989, 244, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refinetti, R.; Menaker, M. The circadian rhythm of body temperature. Physiol. Behav. 1992, 51, 613–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, T.M.; Markwald, R.R.; McHill, A.W.; Chinoy, E.D.; Snider, J.A.; Bessman, S.C.; Jung, C.M.; O’Neill, J.S.; Wright, K.P., Jr. Effects of caffeine on the human circadian clock in vivo and in vitro. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 305ra146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Xue, Y.; Hou, D.; Chen, S.; Xu, Z.; Peng, S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, C. Timing Matters: Time of Day Impacts the Ergogenic Effects of Caffeine-A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, T.W.; Arnsten, A.F. The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: Monoaminergic modulation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C.D.; Garavan, H.; Bellgrove, M.A. Insights into the neural basis of response inhibition from cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009, 33, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, C.; Roehrs, T.; Shambroom, J.; Roth, T. Caffeine effects on sleep taken 0, 3, or 6 hours before going to bed. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, F.; Muurlink, O.; Reid, N. Effects of caffeine on sleep quality and daytime functioning. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2018, 11, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, T.E. Caffeine and exercise: Metabolism, endurance and performance. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Effects of caffeine on human behavior. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 40, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.J.-L.; Tan, B.J.-W.; Yi, L.-X.; Zhou, Z.-D.; Tan, E.-K. Genetic susceptibility to caffeine intake and metabolism: A systematic review. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time of Day | Placebo | CAFcap | CAFrinse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8:00 | 36.90 ± 0.37 | 36.95 ± 0.31 | 36.93 ± 0.35 |

| 12:00 | 37.17 ± 0.37 *# | 37.20 ± 0.21 *# | 37.34 ± 0.24 *# |

| 18:00 | 36.93 ± 0.29 | 36.95 ± 0.26 | 37.02 ± 0.33 |

| Variable | Time | Placebo | CAFcap | CAFrinse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRT (ms) | 8:00 | 282.70 ± 49.10 * | 271.60 ± 43.90 *† | 280.70 ± 46.90 *‡ |

| 12:00 | 279.30 ± 45.50 *# | 268.80 ± 42.80 #†§ | 279.40 ± 43.20 #†‡ | |

| 18:00 | 264.80 ± 39.20 | 263.80 ± 39.90 | 263.00 ± 39.70 | |

| CRT (ms) | 8:00 | 374.00 ± 44.00 * | 363.70 ± 43.90 * | 371.80 ± 45.60 * |

| 12:00 | 360.40 ± 33.60 *# | 340.40 ± 29.10 *#† | 359.70 ± 41.30 #‡ | |

| 18:00 | 349.50 ± 35.00 | 351.80 ± 36.00 | 354.30 ± 32.90 | |

| Stroop Time (s) | 8:00 | 0.70 ± 0.20 * | 0.50 ± 0.20 *† | 0.60 ± 0.20 * |

| 12:00 | 0.80 ± 0.30 *# | 0.50 ± 0.10 *#†§ | 0.60 ± 0.20 *#‡ | |

| 18:00 | 0.60 ± 0.20 | 0.60 ± 0.30 | 0.60 ± 0.20 | |

| Stroop Errors (au) | 8:00 | 2.30 ± 1.80 * | 1.50 ± 1.40 *† | 1.80 ± 1.50 ** |

| 12:00 | 2.00 ± 1.50 *# | 1.60 ± 1.40 #†† | 1.50 ± 1.10 ## | |

| 18:00 | 1.70 ± 1.70 | 1.70 ± 1.20 | 1.70 ± 1.60 |

| Symptom | 8:00 | 12:00 | 18:00 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | CAFcap | CAFrinse | Placebo | CAFcap | CAFrinse | Placebo | CAFcap | CAFrinse | |

| Muscle soreness | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Increased urinary output | 0.00 | 4.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Tachycardia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Anxiety or nervousness | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Headache § | 4.20 | 16.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 4.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Gastrointestinal problems | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Insomnia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Increased activity | 0.00 | 8.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Perceived performance improvement § | 12.50 | 33.30 | 20.80 | 12.50 | 50.00 * | 33.30 | 12.50 | 37.50 | 37.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Amor, S.B.; Dhahbi, W.; Bougrine, H.; Bessifi, M.; Geantă, V.A.; Ursu, V.E.; Trabelsi, K.; Souissi, N. Differential Time-of-Day Effects of Caffeine Capsule and Mouth Rinse on Cognitive Performance in Adolescent Male Volleyball Athletes: A Randomized Crossover Investigation. Life 2026, 16, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010033

Amor SB, Dhahbi W, Bougrine H, Bessifi M, Geantă VA, Ursu VE, Trabelsi K, Souissi N. Differential Time-of-Day Effects of Caffeine Capsule and Mouth Rinse on Cognitive Performance in Adolescent Male Volleyball Athletes: A Randomized Crossover Investigation. Life. 2026; 16(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmor, Salma Belhaj, Wissem Dhahbi, Houda Bougrine, Manel Bessifi, Vlad Adrian Geantă, Vasile Emil Ursu, Khaled Trabelsi, and Nizar Souissi. 2026. "Differential Time-of-Day Effects of Caffeine Capsule and Mouth Rinse on Cognitive Performance in Adolescent Male Volleyball Athletes: A Randomized Crossover Investigation" Life 16, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010033

APA StyleAmor, S. B., Dhahbi, W., Bougrine, H., Bessifi, M., Geantă, V. A., Ursu, V. E., Trabelsi, K., & Souissi, N. (2026). Differential Time-of-Day Effects of Caffeine Capsule and Mouth Rinse on Cognitive Performance in Adolescent Male Volleyball Athletes: A Randomized Crossover Investigation. Life, 16(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010033