Abstract

The development of antibiotic resistance has become a global health challenge, resulting in approximately 800,000 deaths per year. The rapid rise in multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens has prompted an urgent need for antimicrobial alternatives. Punica granatum L. peel has long been valued for its rich bioactive polyphenols with potent antimicrobial properties. In this study, P. granatum L. peel extract (PGPE) was integrated with chitosan nanoparticles (CH-PGPE) to enhance antimicrobial efficacy while minimizing potential cytotoxicity. The antimicrobial potential of PGPE and CH-PGPE was evaluated with agar well diffusion, disk diffusion, and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) analyses against standard ATCC and clinical MDR strains of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. MTT assay evaluated the biocompatibility and anti-proliferative potential of PGPE on ARPE-19 (normal retinal pigment epithelial), HeLa (human cervical cancer), and A549 (human lung carcinoma) cell lines. PGPE exhibited antibacterial activity, and CH-PGPE reduced MIC values by approximately two-fold. Both PGPE and CH-PGPE demonstrated comparable or superior inhibition compared to several conventional antibiotics, particularly against MDR strains. The MTT assay revealed that PGPE was non-cytotoxic to normal ARPE-19 cells, while exhibiting the highest antiproliferative potency against A549 cells and a moderate inhibitory response in HeLa cells. The nanoparticle-supported formulation enhanced the antimicrobial efficacy of PGPE and also exhibited selective anti-proliferative activity against cancer cells without affecting normal cells.

1. Introduction

Antibiotics are the most commonly used drug group in the world [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the concept of ‘appropriate drug use’ as ‘the ability of individuals to obtain the appropriate drug for their clinical findings and characteristics, at the appropriate duration and dosage’ [2]. However, widespread and improper antibiotic use has led to bacterial resistance, creating a global threat [3]. Diseases caused by resistant bacteria pose a serious health risk, particularly for immunocompromised patients in intensive care, leading to prolonged hospitalization, complications, and increased mortality and morbidity [4]. The decreasing efficacy and growing contraindications of synthetic drugs have increased interest in natural therapies [5].

The medicinal use of plants dates back to early human history [6]. After Stephen DeFelice introduced the term ‘nutraceutical’ in 1989, combining ‘nutrition’ and ‘pharmaceutical’, research on herbal and functional foods gained importance [7]. Punica granatum L. (pomegranate), belonging to the Punicaceae family, is a nutritionally rich fruit with diverse bioactive compounds, especially polyphenolics [8,9,10]. P. granatum has antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory properties [11,12,13]. The antibacterial activity of pomegranate exhibits a broad spectrum against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including Streptococcus mutans, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella species, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [14,15,16]. The antimicrobial potential of P. granatum is primarily attributed to the high content of hydrolysable polyphenols, which can disrupt bacterial plasma membranes and inhibit antimicrobial resistance-related proteins [14,16].

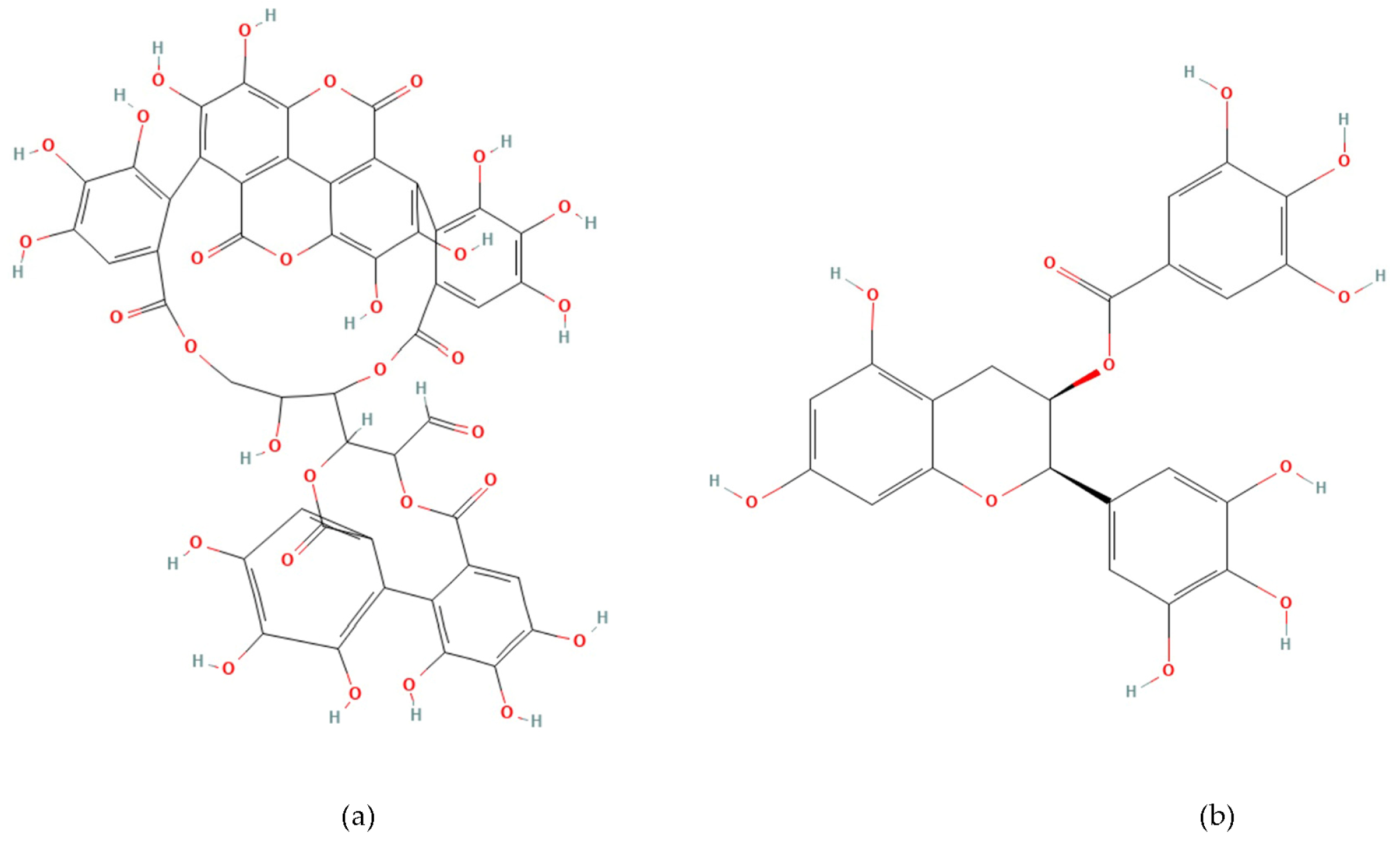

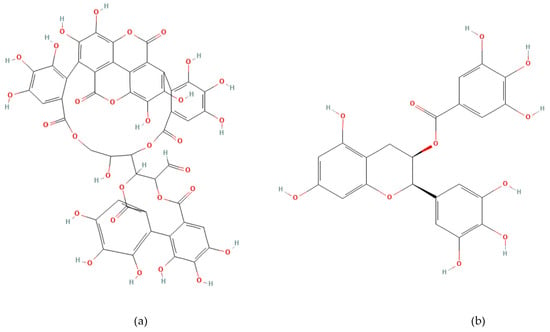

Phenolic compounds are plant-derived secondary metabolites beneficial to human health [17,18]. Punicalagin (2,3-(S) hexahydroxydiphenoyl-4,6-(S,S)-gallagyl-d-glucose, PUN) (Figure 1a) is the most hydroxylated ellagitannin in the pomegranate peel [19,20]. PUN disrupts bacterial redox balance and inhibits “quorum sensing”, the communication system regulating virulence. Interfering with these pathways weakens bacterial defenses, reduces biofilm formation, and enhances susceptibility to antibiotics [21,22]. Epigallocatechin gallate (Epigallocatechin 3-O-gallate, EGCG) (Figure 1b) is a catechin molecule having a gallate group at position 3 [23]. EGCG binds to the lipid bilayer of bacterial membranes, increasing permeability and causing cell death [24]. EGCG also inhibits vital enzymes like DNA gyrase and suppresses protein synthesis [22,25]. The numerous hydroxyl (-OH) groups in PUN and EGCG confer strong antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity, while exhibiting antimicrobial effects by disrupting bacterial cell wall integrity or inhibiting enzymatic processes [23,24,25,26,27].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of Punicalagin (a) and Epigallocatechin gallate (b).

Nevertheless, the bioavailability of phenolic compounds is often limited due to their chemical structure. To address the limitation, nanoparticles (NPs) are widely used in biotechnology, pharmacology, and medicine due to their unique physicochemical properties, which enable them to adhere to cell surfaces and be taken up into cells through various mechanisms. The conjugation of NPs obtained from natural materials with plant extracts has gained momentum lately [28]. Chitosan is a polysaccharide obtained by deacetylation of chitin, which carries a positive charge, providing strong affinity for negatively charged phenolic compounds [29].

This study aims to isolate phenolics from P. granatum and coat the raw extract with chitosan to enhance the stability and antibacterial activity of the compounds, creating a cost-effective and low-toxicity antimicrobial agent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

HPLC sample analyses were performed using a LC-2030C-3D (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) device, with a diode array detector (DAD) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and an RP-18 reverse phase column (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Methanol (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used as the extraction solvent, while acetic acid was purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany) for encapsulation procedures. Chitosan, Tween 80, and sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). RPMI-1640 medium was obtained from Capricorn (Düsseldorf, Germany), and fetal bovine serum (10% FBS), along with penicillin-streptomycin (1%, 10,000 U/mL), were purchased from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA, USA) for cell culture.

Reference strains: Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13883), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 43300) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Clinical isolates were collected from patients at Recep Tayyip Erdogan University Training and Research Hospital (Rize, Turkey). A549 (human lung carcinoma), HeLa (cervical carcinoma), and ARPE-19 (retinal pigment epithelial) cell lines were obtained from the Department of Medical Microbiology, Recep Tayyip Erdogan University.

2.2. Preparation of Punica granatum L. Peel Extract

The P. granatum L. used in the study was obtained from a local farmer who does not use pesticides (Adıyaman, Turkey). The fruit peels were dried in an oven at 40 °C and then ground into a powder. In total, 15–20 g of the powder was mixed with 100 mL of methanol-water (50:50, v/v) and stirred for 72 h. It was then filtered, and methanol was removed by rotary evaporation. The stock extract was prepared as a 1000 mg/mL solution in distilled water and stored at 4 °C.

2.3. Fraction Recovery by HPLC Method

Reverse-phase HPLC was employed for the detection and separation of phenolic acids [30]. Elution was performed using a binary gradient system with Eluent A (0.2% phosphoric acid) and Eluent B (0.3% acetonitrile). The gradient applied for analytical separation is as follows: 0–10 min at 10% B, 10–30 min at 25% B, 30–38 min at 60% B, 38–45 min at 60% B, and 45–45.01 min at 10% B. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C, with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min and an injection volume of 100 µL. UV-Vis detection was performed at 203, 280, 320, and 360 nm. Calibration curves were generated from standard solutions of 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 ppm. For pre-purification, a 50% methanol solution, determined as having the highest phenolic content, was used.

2.4. Chitosan Nanoparticle Coating of PGPE

2.4.1. Encapsulation

Chitosan nanoparticles were prepared using the ionic gelation method described by Subair et al. [31]. Chitosan was dissolved in 1% (v/v) acetic acid and stirred for 24 h at room temperature to obtain a homogeneous solution. Tween 80 was added to the mixture was stirred for 2 h at 60 °C. After cooling to room temperature, PGPE was added dropwise, maintaining a chitosan to bioactive compound ratio of 1:1.25. Finally, a 0.5% (w/v) TPP solution was added, and the mixture was stirred for an additional 30 min.

2.4.2. Purification

The resulting emulsion was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed with a 1% (v/v) Tween 80 solution at twice the volume of the pellet to remove unbound compounds. To remove residual impurities, the nanoparticles were washed twice with deionized water, aliquoted, and stored at 4 °C.

2.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests

2.5.1. Agar Well Diffusion Method

In the agar well diffusion method, a well with a diameter of 8 mm was used in Mueller–Hinton Agar (MHA) with a standard thickness of 4 mm [32]. Bacterial suspensions adjusted to 0.5 McFarland were spread onto the agar surface. Wells were filled with 100 μL of PGPE at concentrations of 400, 200, 100, 50, 25, and 12.5 mg/mL, while sterile distilled water served as the negative control. Each concentration was applied once per plate, and the assay was independently repeated in triplicate. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, inhibition zones were recorded. As all strains showed growth inhibition, the lowest effective concentration was subsequently determined using the minimal inhibitory concentration method.

2.5.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Analysis

Pure cultures in the logarithmic growth phase were adjusted to 0.5 McFarland (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL). For the MIC assay, two-fold serial dilutions of PGPE and CH-PGPE were prepared at 256, 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, and 2 µg/mL, with negative and positive controls. Each concentration was tested once per run, and the assay was independently repeated twice. Following incubation, the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration showing no visible bacterial growth. CLSI breakpoints were applied, where MIC ≥ 32 µg/mL indicates resistance (R), 8–16 µg/mL intermediate susceptibility (I), and ≤4 µg/mL susceptibility (S) [33].

2.5.3. Disk Diffusion Method

In the disk diffusion assay, sterile blank disks were impregnated with 400 mg/mL PGPE and CH-PGPE. Ten disks were placed on each MHA plate: eight containing the appropriate control antibiotics and two centrally positioned disks with PGPE and CH-PGPE. Bacterial suspensions adjusted to 0.5 McFarland were inoculated onto the agar surface, and disks were applied with sterile forceps. Disks were tested once per plate, and the assay was independently repeated three times. After 24 h incubation at 35 °C, inhibition zones were measured. Antimicrobial activity was interpreted according to CLSI breakpoints: ≤14 mm as resistant (R), 15–19 mm as intermediates (I), and ≥20 mm as susceptible (S) [33].

2.6. MTT Cytotoxicity Assay

The MTT assay was performed according to the method of Mossmann [34]. PGPE was tested at 800, 400, 200, 100, 50, and 25 μg/mL, with each concentration applied to four replicate wells, and the experiment was independently repeated three times. After 48 h of treatment, 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The medium was then removed, and the resulting formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences were analyzed using an unpaired t-test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Most experiments were conducted in triplicate.

3. Results

3.1. HPLC

The highest phenolic content was obtained using 50% methanol (4082.22 µg PUN/g), whereas 80% and 100% methanol yielded considerably lower levels (1395 µg and 1179.53 µg PUN/g, respectively). Similarly, EGCG content was maximal in 50% methanol (127.95 µg EGCG/g). Therefore, 50% methanol was selected as the extraction solvent. The identified compounds and corresponding mass spectral data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

PGPE phenolic compounds in increasing methanol concentrations (µg/g).

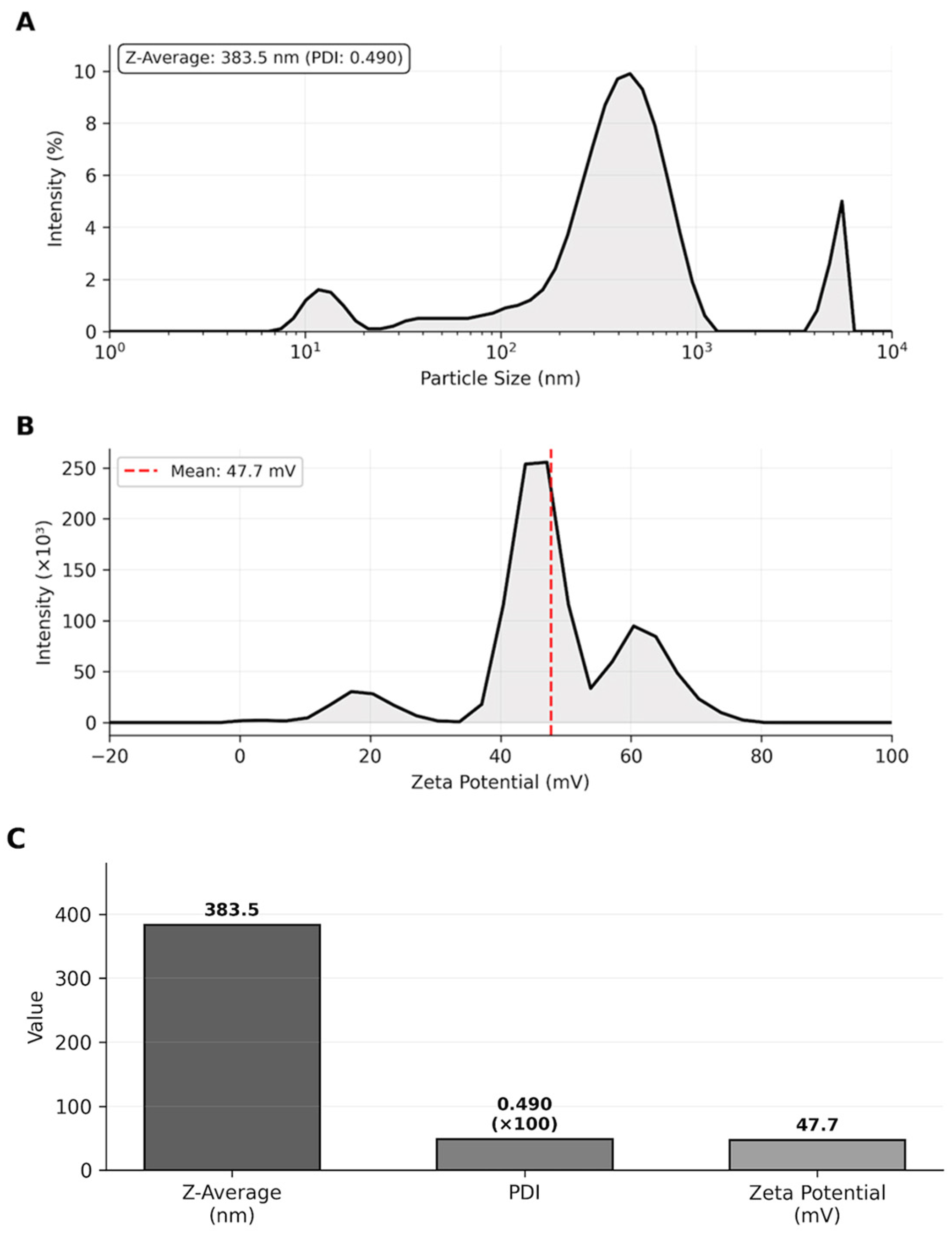

3.2. Nanoparticle Characterization

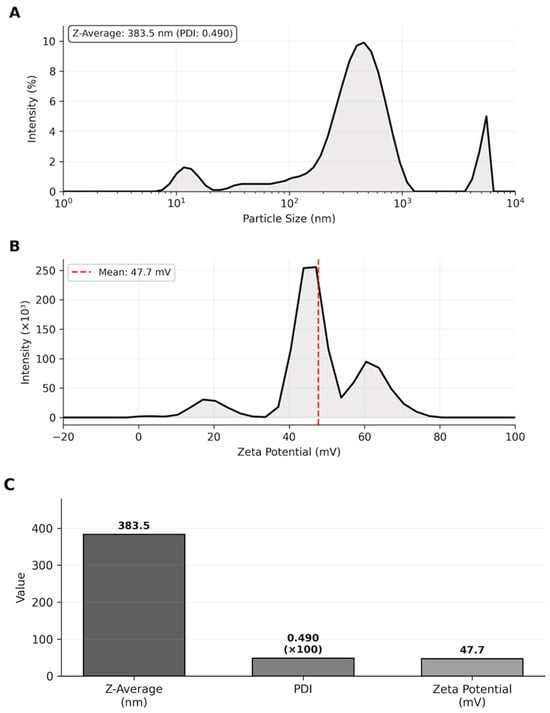

The Z-average of 383.5 nm falls within the optimal size range (100–500 nm) for transdermal drug delivery systems, which was suitable for penetration through the stratum corneum while avoiding rapid systemic clearance. The PDI value of 0.490 indicated acceptable size distribution homogeneity. The high positive zeta potential (+47.7 mV, exceeding the ±30 mV stability threshold) ensured excellent colloidal stability through strong electrostatic repulsion between particles, preventing aggregation and maintaining long-term suspension stability (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Size, zeta potential, and polydispersity index of nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

Nanoparticle characterization. (A) Particle size distribution by intensity showing Z-average. (B) Zeta potential distribution. (C) Summary of characterization parameters demonstrating suitable physicochemical properties for transdermal delivery.

Particle size distribution by intensity showing Z-average of 383.5 nm with PDI of 0.490. Zeta potential distribution with a mean value of +47.7 mV, indicating excellent colloidal stability.

3.3. Antimicrobial Activity

3.3.1. Agar Well Diffusion Test Results

The antimicrobial activity of PGPE was evaluated against standard ATCC reference strains following CLSI guidelines to ensure reproducibility and comparability with the literature [33]. PGPE inhibited the growth of all tested bacteria in a dose-dependent manner. Sensitivity varied among the strains: S. aureus showed the greatest susceptibility (32 ± 1.00 mm), whereas P. aeruginosa displayed the smallest inhibition zone (24 ± 1.00 mm) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The inhibition zone diameters created by PGPE (mm).

3.3.2. MIC Analysis

MIC values of PGPE and CH-PGPE were determined against clinically isolated strains. The MIC distributions for both formulations across the tested bacteria are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

MIC values of PGPE and CH-PGPE (µg/mL).

PGPE exhibited intermediate activity (I) against S. aureus, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae, while showing resistance (R) against P. aeruginosa. In contrast, CH-PGPE demonstrated consistently stronger antimicrobial activity across all strains, indicating intermediate effectiveness (I). Nanoparticle coating markedly enhanced antibacterial efficacy, reducing MIC values by approximately half for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Overall, CH-PGPE displayed a broader and more potent antimicrobial spectrum compared to PGPE.

3.3.3. Disk Diffusion Test Results

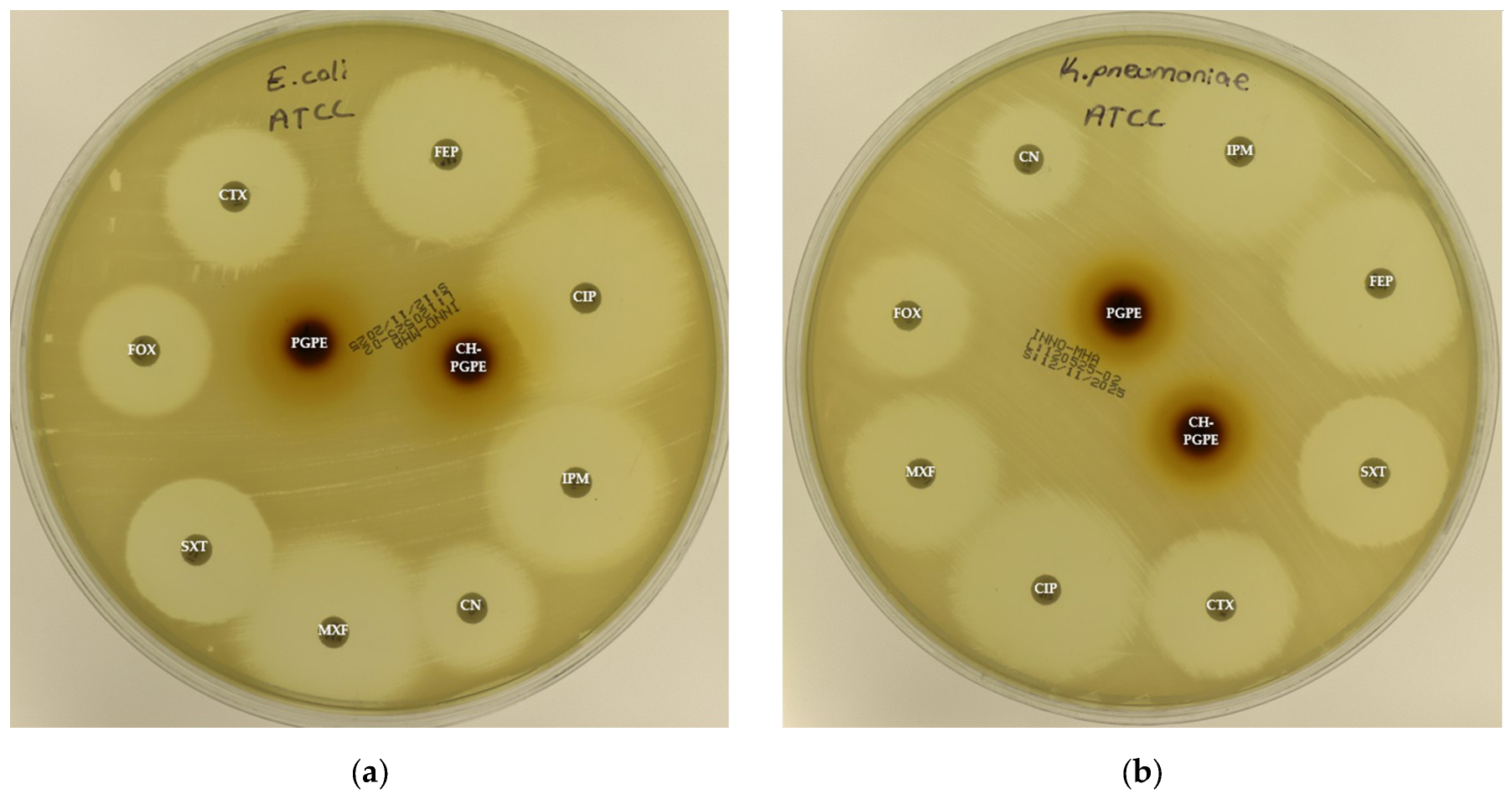

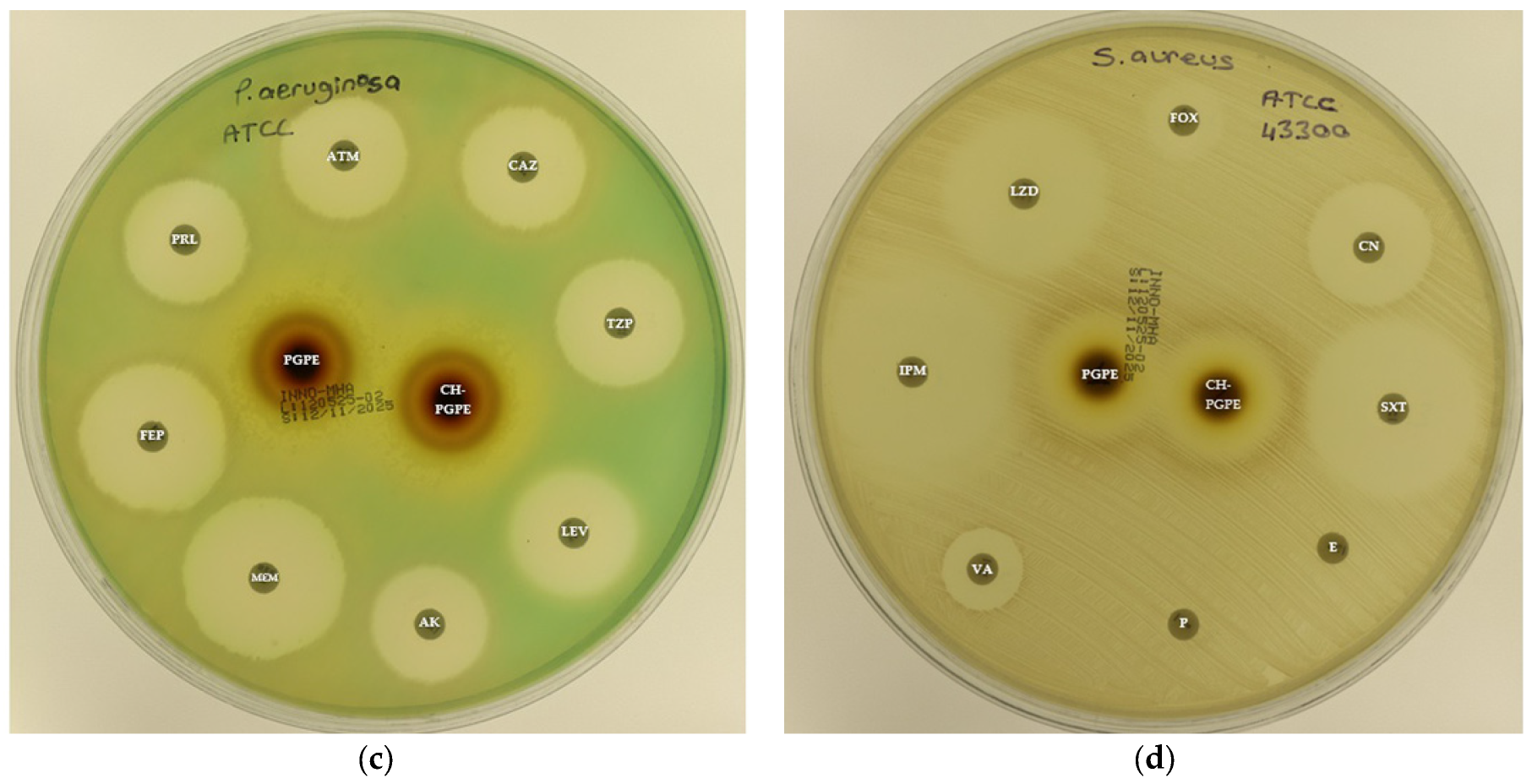

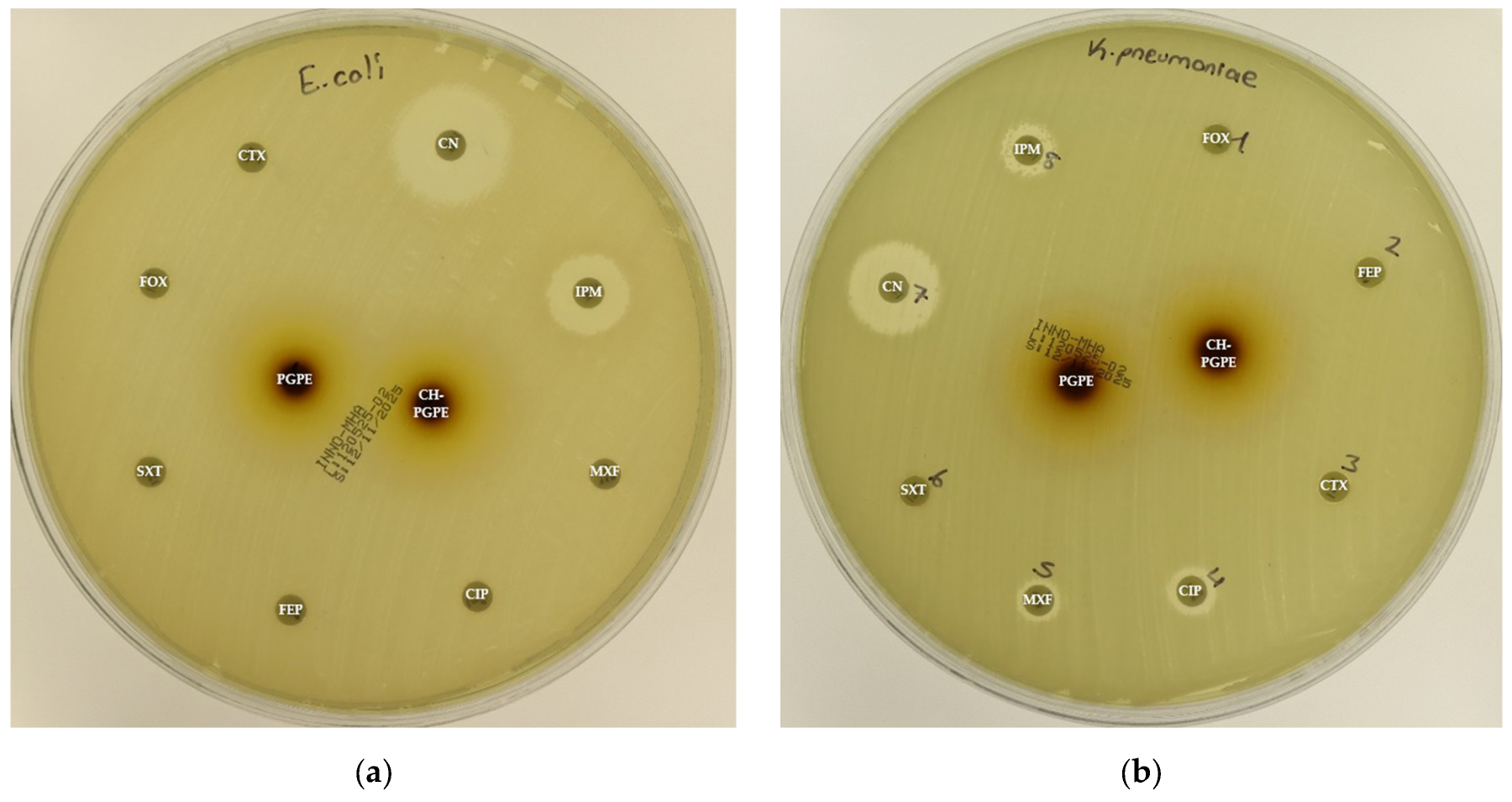

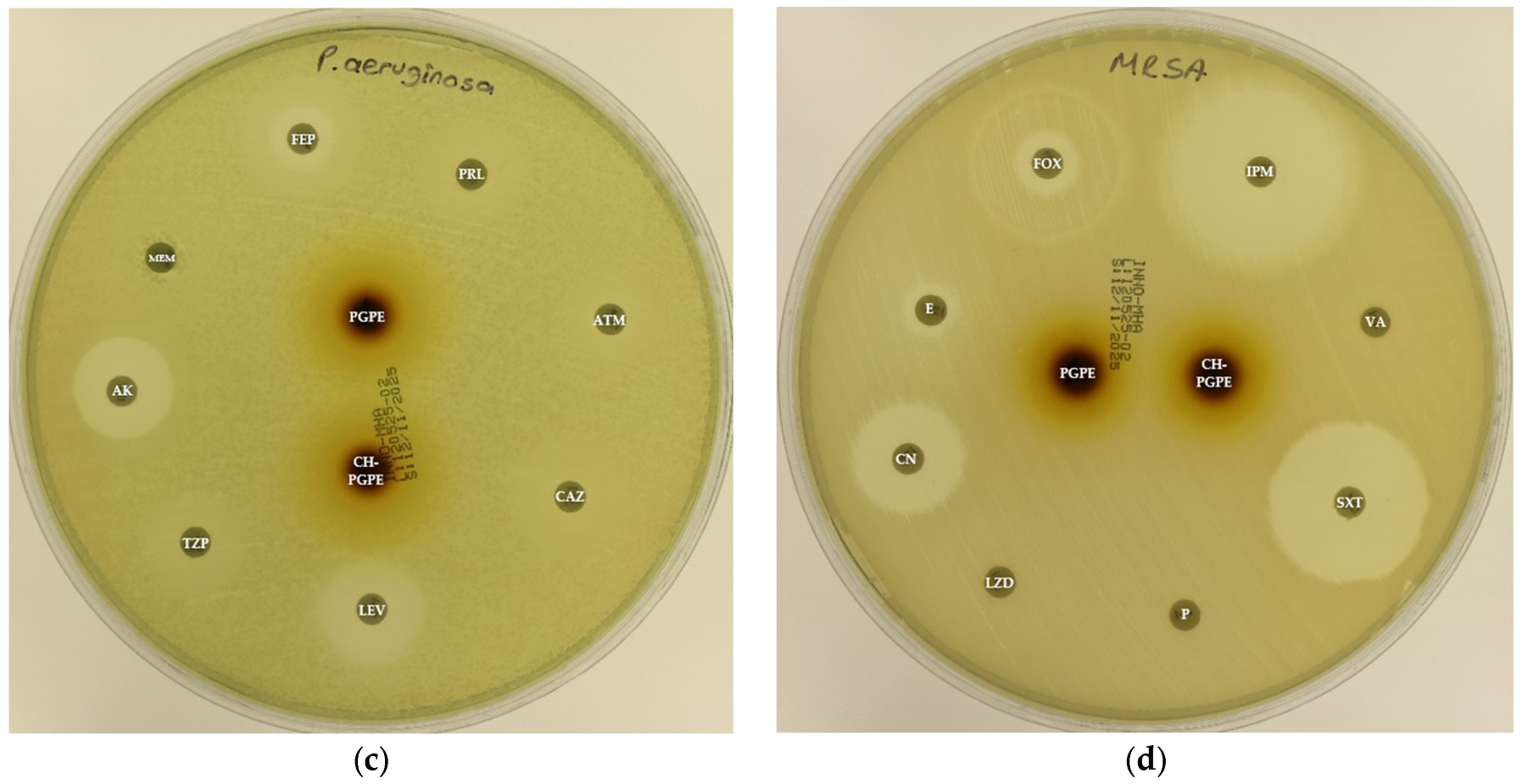

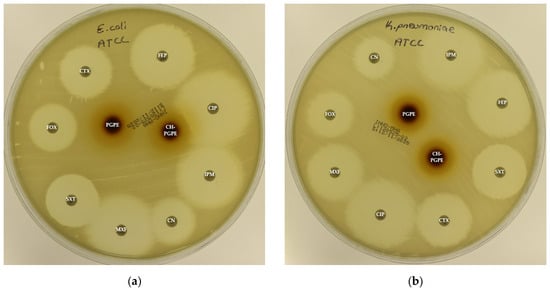

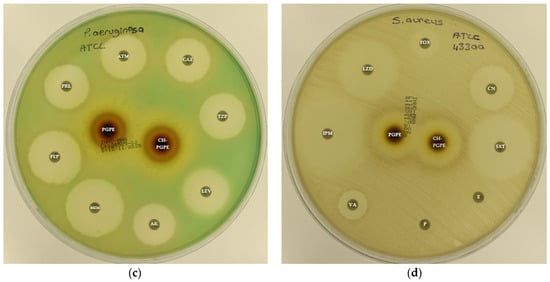

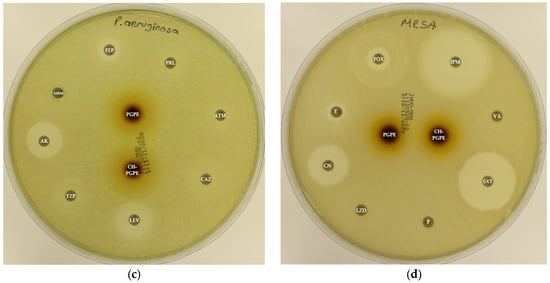

The disk diffusion analysis was performed with both ATCC reference strains and clinical isolates of E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus, to demonstrate the potential clinical relevance and compare antimicrobial responses. The inhibition zones produced by the treatments are presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4. According to preliminary experiments, 400 mg/mL was identified as the optimal effective concentration of PGPE: therefore, the PGPE and CH-PGPE impregnated disks were prepared at this concentration.

Figure 3.

(a) Inhibition zones on Escherichia coli ATCC 25922; (b) Inhibition zones on Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883; (c) Inhibition zones on Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853; (d) Inhibition zones on Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300. AK: Amikacin, ATM: Aztreonam, CAZ: Ceftazidime, CH-PGPE: Chitosan-coated P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL), CIP: Ciprofloxacin, CN: Gentamicin, CTX: Cefotaxime, E: Erythromycin, FEP: Cefepime, FOX: Cefoxitin, IPM: Imipenem, LEV: Levofloxacin, LZD: Linezolid, MEM: Meropenem, MXF: Moxifloxacin, P: Penicillin, PGPE: P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL), PRL: Piperacillin, SXT: Sulphamethoxazole/trimethoprim, TZP: Tazobactam/piperacillin, VA: Vancomycin.

Figure 4.

(a) Inhibition zones on MDR Escherichia coli; (b) Inhibition zones on MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae; (c) Inhibition zones on MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa; (d) Inhibition zones on Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. AK: Amikacin, ATM: Aztreonam, CAZ: Ceftazidime, CH-PGPE: Chitosan-coated P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL), CIP: Ciprofloxacin, CN: Gentamicin, CTX: Cefotaxime, E: Erythromycin, FEP: Cefepime, FOX: Cefoxitin, IPM: Imipenem, LEV: Levofloxacin, LZD: Linezolid, MEM: Meropenem, MXF: Moxifloxacin, P: Penicillin, PGPE: P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL), PRL: Piperacillin, SXT: Sulphamethoxazole/trimethoprim, TZP: Tazobactam/piperacillin, VA: Vancomycin.

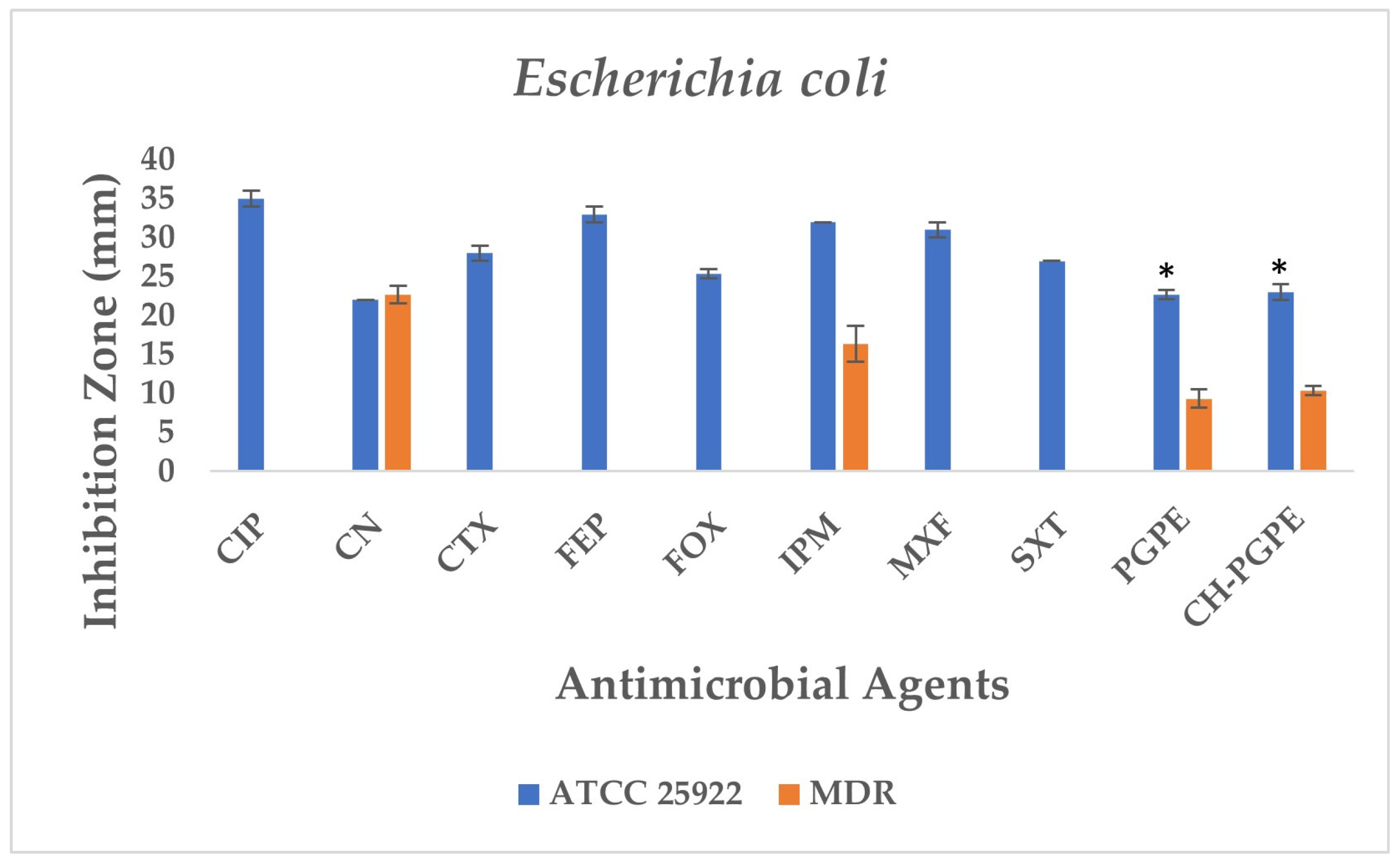

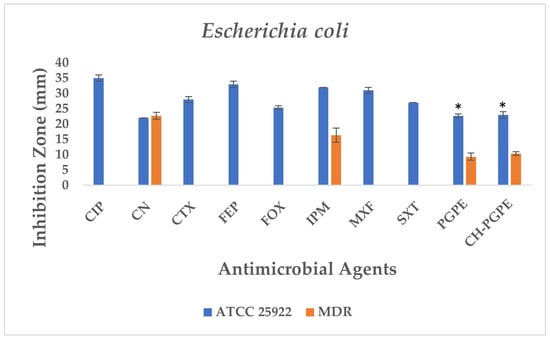

According to the CLSI M100 interpretive criteria for E. coli, the quality control strain (E. coli ATCC 25922) exhibited inhibition zones within the expected susceptible range for all tested antibiotics, confirming the reliability of the assay (Figure 5) [33]. In contrast, the multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. coli isolate showed markedly reduced or absent inhibition zones for several antibiotics. Complete resistance was observed to CIP, CTX, FEP, FOX, MXF, and SXT, with no measurable inhibition zones. The strain also exhibited resistance to IPM (32 ± 0.00 mm) and partial sensitivity to CN (22 ± 0.00 mm).

Figure 5.

Antimicrobial activity of PGPE and CH-PGPE against E. coli compared to reference antibiotics. CIP: Ciprofloxacin; CN: Gentamicin; CTX: Cefotaxime; FEP: Cefepime; FOX: Cefoxitin; IPM: Imipenem; MXF: Moxifloxacin; SXT: Sulphamethoxazole/trimethoprim; PGPE: P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); CH-PGPE: Chitosan-coated P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); MDR: Multi-drug resistance. Results were analyzed using Student’s unpaired t-test in GraphPad (n = 3). * p < 0.05.

PGPE and CH-PGPE produced inhibition zones of 10 ± 1.15 mm each against the MDR strain, indicating a low but measurable antibacterial effect. In contrast, both extracts exhibited moderate activity (23 ± 0.58 mm) against the ATCC 25922 control strain, corresponding to a susceptible range. These findings confirm that while the MDR isolate was resistant to multiple conventional antibiotics, PGPE and CH-PGPE demonstrated mild inhibitory effects, suggesting that the bioactive components of P. granatum retain some antibacterial potential even against resistant strains. Unpaired t-test analysis showed that PGPE produced significantly greater inhibition in E. coli ATCC 22922 than in the MDR strain; the difference between the ATCC and MDR group was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Similarly, CH-PGPE produced stronger inhibition in the ATCC strain compared with the MDR isolate; this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

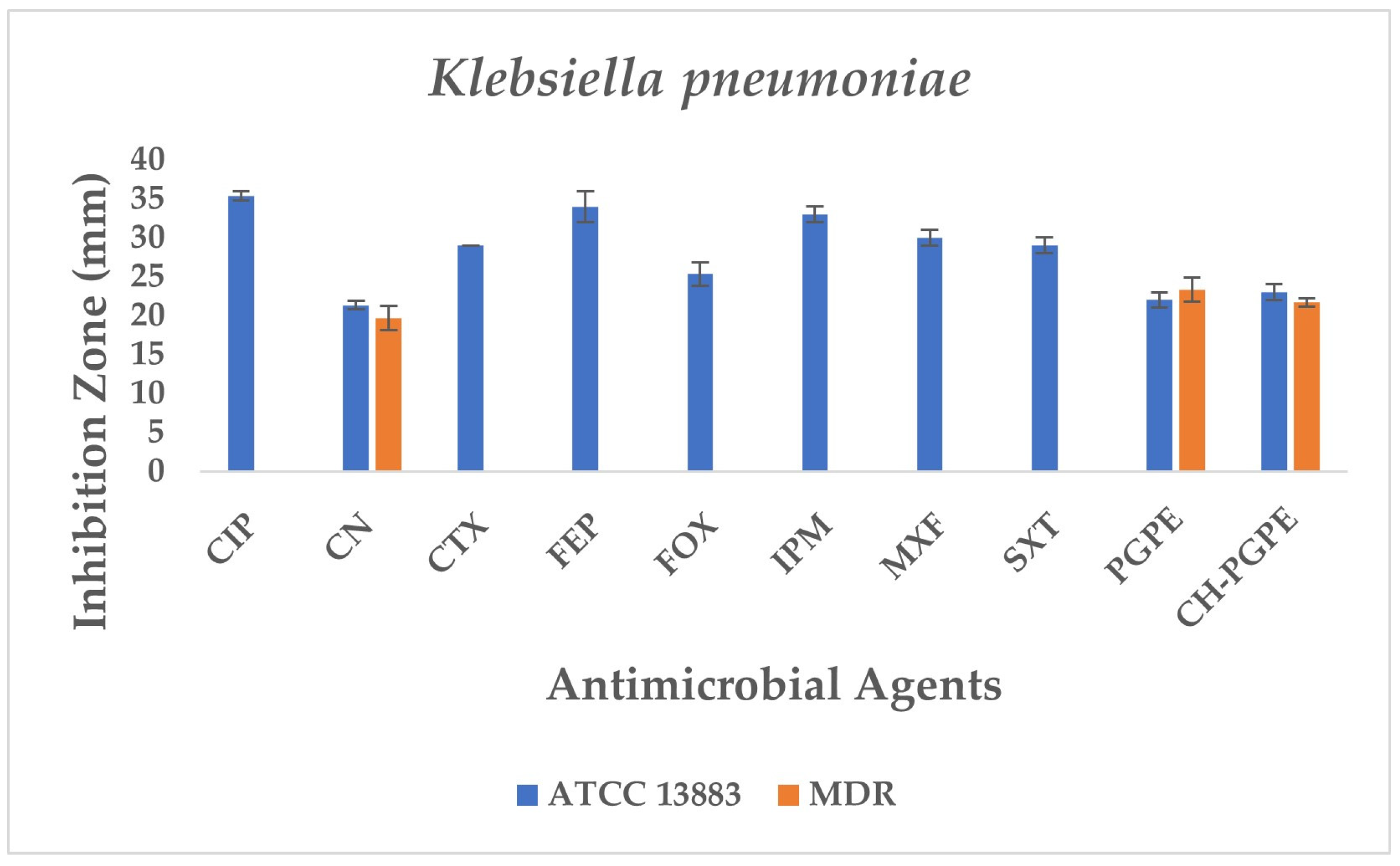

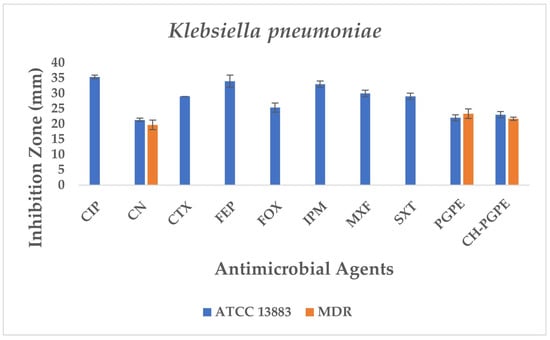

The reference strain K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 exhibited inhibition zones consistent with the susceptible range for all tested antibiotics (Figure 6). MDR K. pneumoniae isolate, however, showed a complete lack of inhibition against most antibiotics, including CIP, CTX, FEP, FOX, IPM, MXF, and SXT, indicating extensive resistance. Only CN produced a measurable zone of 18 ± 1.53 mm, which corresponds to intermediate susceptibility.

Figure 6.

Antimicrobial activity of PGPE and CH-PGPE on K. pneumoniae compared to reference antibiotics. CIP: Ciprofloxacin; CN: Gentamicin; CTX: Cefotaxime; FEP: Cefepime; FOX: Cefoxitin; IPM: Imipenem; MXF: Moxifloxacin; SXT: Sulphamethoxazole/trimethoprim; PGPE: P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); CH-PGPE: Chitosan-coated P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); MDR: Multi-drug resistance.

Interestingly, both PGPE and CH-PGPE demonstrated clear inhibitory activity against the MDR strain, producing zones of 23 ± 1.53 mm and 21 ± 0.58 mm, respectively. Against the susceptible ATCC 13883 strain, the inhibition zones were 23 ± 1.00 mm for PGPE and 24 ± 1.00 mm for CH-PGPE, indicating consistent antibacterial activity. These results suggest that both PGPE and CH-PGPE retained their antimicrobial potential even against highly resistant K. pneumoniae, with CH-PGPE exhibiting slightly reduced but comparable activity to PGPE. There is no statistically significant difference between PGPE and CH-PGPE (p > 0.05).

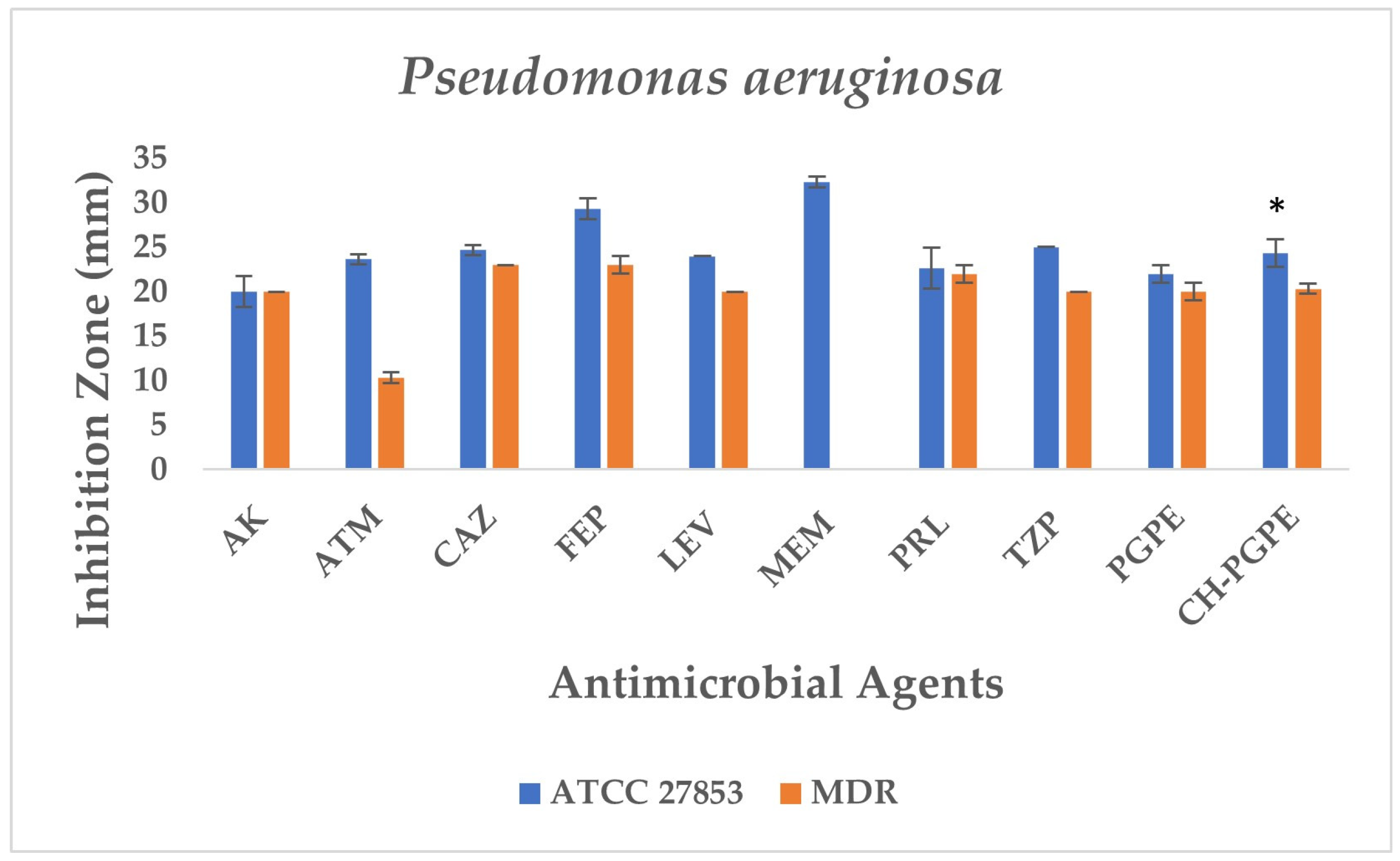

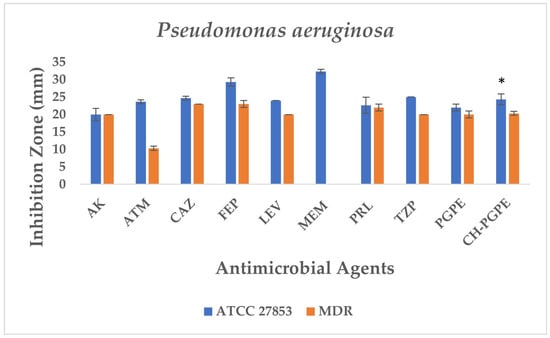

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 reference strain exhibited inhibition zones within the expected susceptible ranges for all tested antibiotics, confirming the reliability of the antimicrobial susceptibility testing procedure. In contrast, the MDR P. aeruginosa isolate demonstrated markedly reduced inhibition zones or complete resistance to several antibiotics (Figure 7). The strain showed no measurable inhibition against MEM, indicating carbapenem resistance, and significantly reduced susceptibility to ATM (11 ± 0.58 mm). Moderate inhibition zones were observed for AK (20 ± 0.5 mm), CAZ (23 ± 0.5 mm), FEP (24 ± 1.00 mm), LEV (20 ± 0.5 mm), PRL (21 ± 1.00 mm), and TZP (20 ± 0.58 mm), all of which fall below CLSI susceptibility breakpoints, confirming the MDR phenotype.

Figure 7.

Antimicrobial activity of PGPE and CH-PGPE on P. aeruginosa compared to reference antibiotics. AK: Amikacin; ATM: Aztreonam; CAZ: Ceftazidime; FEP: Cefepime; LEV: Levofloxacin; MEM: Meropenem; PRL: Piperacillin; TZP: Tazobactam/piperacillin; PGPE: P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); CH-PGPE: Chitosan-coated P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); MDR: Multi-drug resistance. Results were analyzed using Student’s unpaired t-test in GraphPad (n = 3). * p < 0.05.

PGPE and CH-PGPE demonstrated measurable antibacterial activity against the MDR isolate, each producing inhibition zones of 21 mm. Against the susceptible ATCC 27853 strain, PGPE and CH-PGPE formed inhibition zones of 22 ± 1.00 mm and 24 ± 1.53 mm, respectively, suggesting consistent antibacterial potential. These findings indicate that PGPE and CH-PGPE maintain inhibitory activity even against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa, comparable to several conventional antibiotics tested in this study. According to the unpaired t-test results between the P. aeruginosa ATCC and MDR groups, the inhibitory effect of the ATCC strain was higher when CH-PGPE was applied than the MDR strain, and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

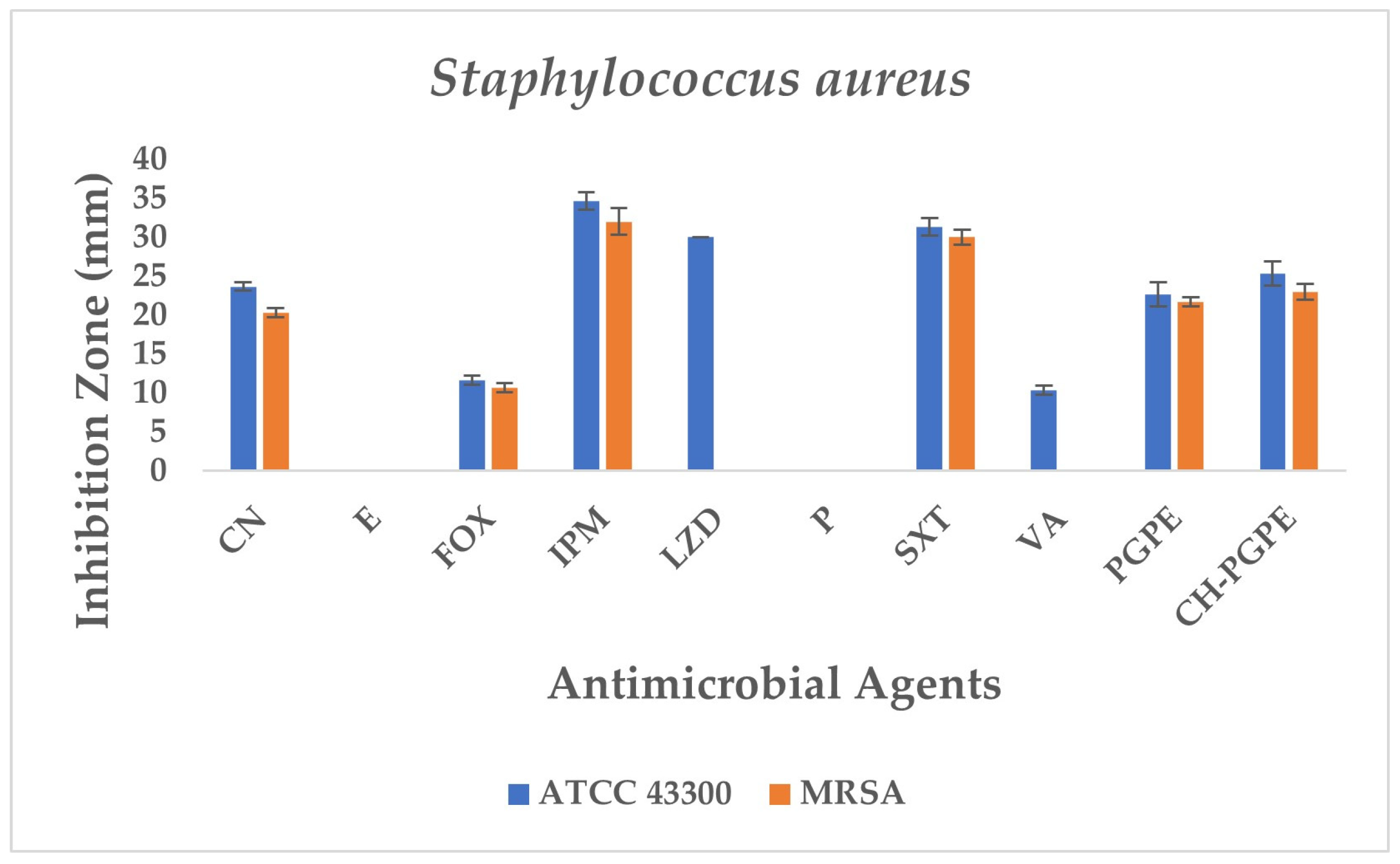

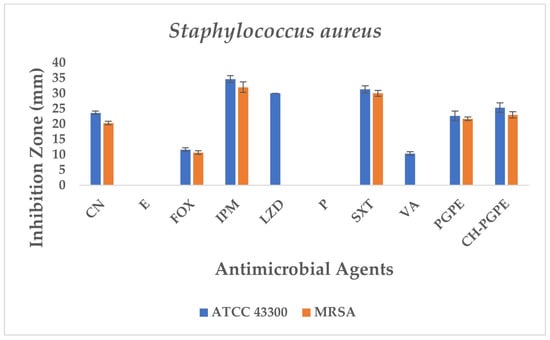

S. aureus ATCC 43300 reference strain displayed inhibition zones within the expected susceptible ranges for most antibiotics (Figure 8). In contrast, the MRSA isolate exhibited resistance to several antibiotics, including E, P, LZD, and VA, with no measurable inhibition zones. The strain showed only weak inhibition to FOX (11 ± 0.58 mm), confirming its methicillin-resistant phenotype. CN (23 ± 0.58 mm) and SXT (31 ± 1.15 mm) displayed intermediate to susceptible activity, while IPM (34 ± 1.15 mm) produced the largest inhibition zone, indicating preserved sensitivity.

Figure 8.

Antimicrobial activity of PGPE and CH-PGPE on S. aureus compared to reference antibiotics. CN: Gentamicin; E: Erythromycin; FOX: Cefoxitin; IPM: Imipenem; LZD: Linezolid; P: Penicillin; SXT: Sulphamethoxazole/trimethoprim; VA: Vancomycin; PGPE: P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); CH-PGPE: Chitosan-coated P. granatum Peel Extract (400 mg/mL); MRSA Methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

PGPE and CH-PGPE demonstrated measurable antibacterial activity against MRSA, with inhibition zones of 21 ± 0.58 mm and 23 ± 1.00 mm. Against the susceptible ATCC strain, PGPE and CH-PGPE produced inhibition zones of 22 ± 1.53 mm and 25 ± 1.53 mm, respectively. These findings indicate that both PGPE and CH-PGPE retained inhibitory effects against MRSA, with comparable or superior activity to certain conventional antibiotics tested, particularly those showing resistance in the MRSA isolate. There is no statistically significant difference between PGPE and CH-PGPE (p > 0.05).

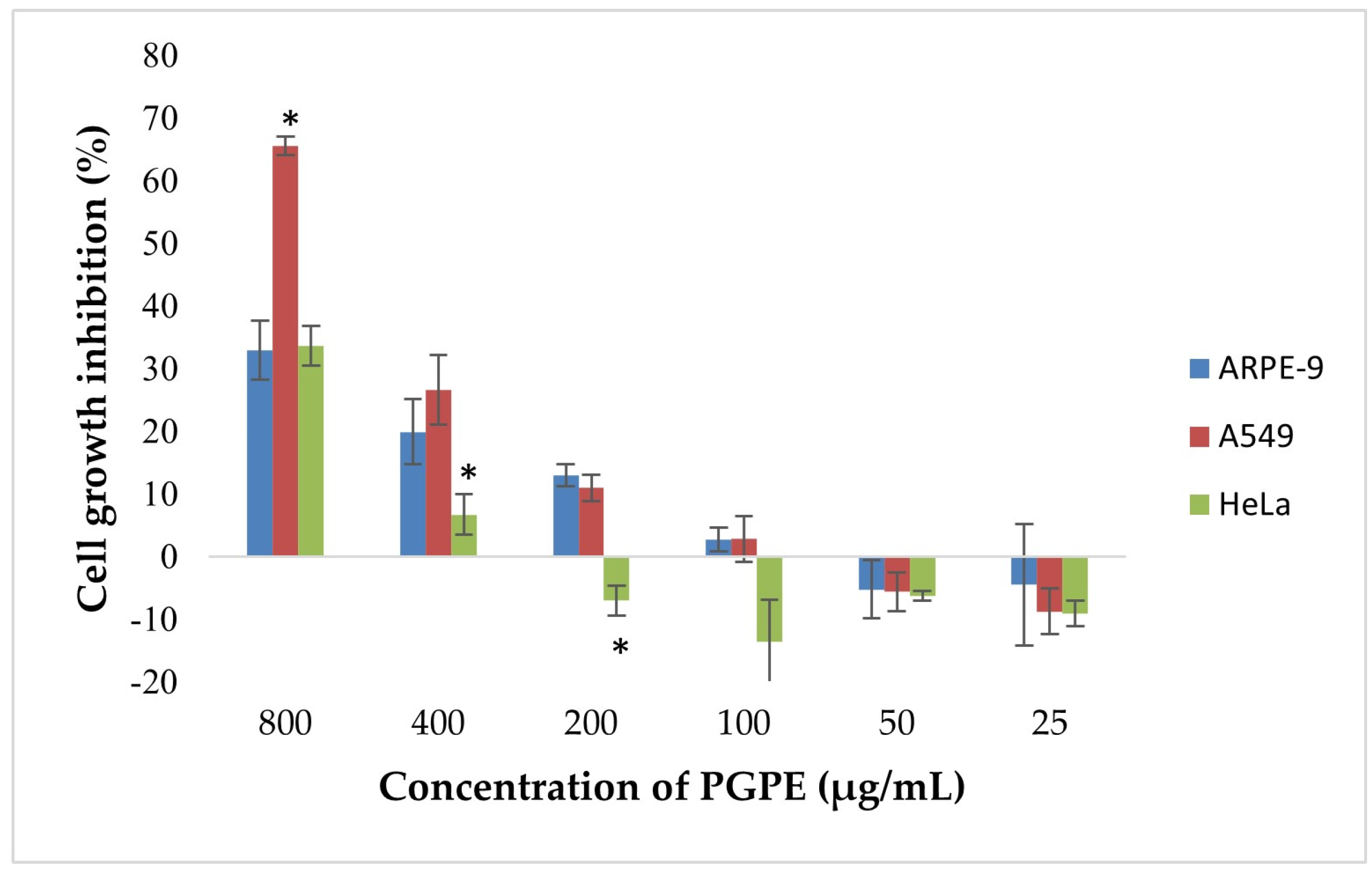

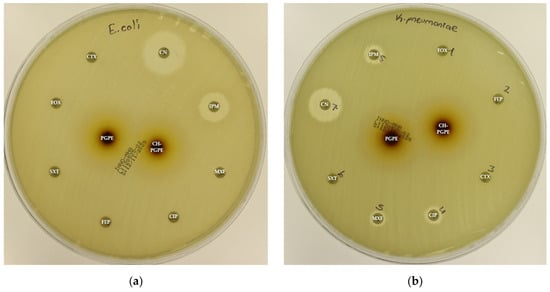

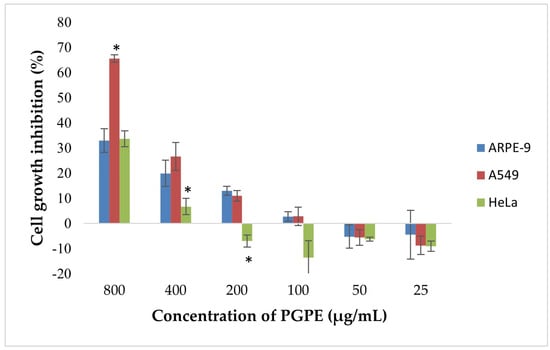

3.4. MTT Analysis

According to the results, dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation was observed in A549 and HeLa cells (Figure 9). The highest inhibition was detected at 800 µg/mL, reaching approximately 68% in A549 and 33.6% in HeLa cells. In contrast, ARPE-19 cells exhibited a lower inhibition rate (~30%) at the same concentration, indicating selective cytotoxicity toward cancer cells. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in growth inhibition were observed between A549 and ARPE-19 cells at 800 and 400 µg/mL, and between HeLa and ARPE-19 at 400 µg/mL. At concentrations ≤ 200 µg/mL, growth inhibition markedly decreased and was negligible or slightly negative, particularly in ARPE-19 and HeLa cells. No significant inhibition was observed below 100 µg/mL in any of the extract cell lines.

Figure 9.

Cytotoxic effects of PGPE on human cancer and diploid cell lines. Results were analyzed using Student’s unpaired t-test in GraphPad (n = 4). * p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Previous studies provide evidence for the protective effect of P. granatum peel on organs in sepsis [35,36]. Sepsis is a systemic condition that develops in response to infection [37]. Therefore, the antibacterial effectiveness of P. granatum has been observed on microorganisms that are the most common causative agents of sepsis, which are also known to cause nosocomial infections [36]. P. granatum is a plant that possesses antibacterial properties and is widely used as a traditional medicine for the treatment of pathogenic bacteria [11,38]. The antimicrobial effectiveness of P. granatum has been tested on Salmonella strains, which are bacterial pathogens that cause food poisoning and gastroenteritis and have significant morbidity and mortality. It has been reported that it exhibited antibacterial activity even against Salmonella typhimurium (JOL 389), which has high resistance rates [38]. Additionally, it was found to be inhibitory on Bacillus cereus, B. subtilis, B. coagulens, S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, as well as on oral pathogens S. epidermidis, L. acidophilus, S. mutans, and S. salivarius [39,40,41]. The antimicrobial activity of P. granatum may be related to polyphenol structures, as polyphenols can affect the bacterial cell wall, inhibit hydrolytic enzymes, interact with proteins, and disrupt the coaggregation of microorganisms [19]. Additionally, P. granatum is quite rich in punicalagins, which are multiple esters of gallic acid and glucose known for their antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [42,43,44]. However, the bioavailability of phenolic compounds in living systems is generally low. It has been shown that the use of P. granatum’s active ingredients together with polysaccharide-based chitosan increases its antioxidant capacity [45]. In our study, it was determined that the inhibitory effect of PGPE on Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria increased with chitosan coating and exhibited significant antibacterial activity at MIC levels. Notably, after nanoparticle coating, the MIC values were reduced by half for all strains. Although there is no visibly significant difference at the macro level according to the disk diffusion results, MIC results indicate that nanoparticle coating significantly increases efficacy at the micro level. This situation shows that when phenolic components are coated with nanoparticles, their bioavailability and cellular uptake increase, thereby enhancing their antimicrobial activity.

In general, Gram-positive bacteria are considered more sensitive than Gram-negative bacteria to different antimicrobial compounds because of the differences in the structure of their cell walls [39]. Similarly, S. aureus was found to be more sensitive against both PGPE and CH-PGPE. MRSA is an important pathogen that is cross-resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics. When the PBP2a gene expression was analyzed by Western blot, it was confirmed by an increase in Punicalagin’s binding affinity to the cell wall peptidoglycan [19]. Chitosan coating reduced the MIC values for S. aureus, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae from 16 µg/mL to 8 µg/mL. P. aeruginosa had an MIC value of 32 µg/mL, being identified as the most resistant strain against PGPE; however, after nanoparticle coating, these values decreased to 16 µg/mL. Considering the highly drug-resistant nature of P. aeruginosa, it is believed that the CH-PGPE formulation could be effective even against resistant bacteria. This suggests that the nanoparticle carrier system enhances the bioavailability of phenolic compounds and their passage through the cell membrane. This increase can be explained by the more effective transport of compounds, controlled release, and enhanced interaction with microbial cells, thanks to the nanoparticle system. In the MIC analysis of pure PGPE on MDR and ATCC strains, P. aeruginosa MDR was detected at 20 μg/μL, P. aeruginosa ATCC at 30 μg/μL, and S. aureus ATCC and MRSA at 4 and 12 μg/μL, respectively [46]. Gosset-Erard and colleagues showed that P. granatum peel consists mostly of pedunculagin I and II, ellagic acid and its derivatives, and punicalagin and its isomers [47]. It has been found that the peel extract of P. granatum has an inhibitory effect on S. epidermidis (ATCC 1222) and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 9027), and it also provides MIC values of 0.60 µg/mL for P. aeruginosa (ATCC 9027), 1.2 µg/mL for E. coli (ATCC 25922), and 0.60 µg/mL for S. aureus (ATCC 6538) [47]. It has been reported that the phenolics contained in pomegranate extract, such as gallic acid, ellagic acid, and punicalagin, exert their effects by disrupting cell wall integrity and causing protein denaturation [19].

Combination with nanoparticles potentially enhances this effect in a synergistic manner. CH-PGPE, which has antibacterial potential, can reduce the increasing costs and mortality associated with treatment failures caused by resistant bacteria, serving as an alternative to expensive commercial drugs. In a study comparing the antibacterial activities of pomegranate extract and its chitosan-coated form, it was reported that nanoparticle coating led to a decrease in MRSA MIC values [48]. When inhibition zone diameters and MIC values were compared, the chitosan-coated formulation was reported to exhibit enhanced antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa [49]. PGPE and CH-PGPE were compared with various antibiotics tested against reference (ATCC) and multidrug-resistant (MDR/MRSA) bacterial strains. According to the antibiogram results, CH-PGPE demonstrated superiority over many antibiotics by showing inhibition zones ranging from 10 to 24 mm against resistant strains. While ciprofloxacin, cefepime, and meropenem were completely ineffective against MDR strains, CH-PGPE provided 10–20 mm inhibition. Additionally, it showed similar activity against S. aureus and MRSA when compared to tobramycin and vancomycin. These results suggest that nanoparticle-supported herbal compounds could be an effective alternative in combating antibiotic resistance. While most conventional antibiotics do not show inhibitory effects in resistant strains, CH-PGPE provided inhibition with a diameter of 10–22 mm. In Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus/MRSA), CH-PGPE showed an effect close to Vancomycin and Linezolid (22 mm). While the effect of antibiotics in Gram-negative bacteria has largely been nullified in resistant strains, PGPE has retained its effect. The results indicate that PGPE and CH-PGPE exhibit high and consistent antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria compared to conventional antibiotics. In terms of antimicrobial activity, CH-PGPE should be considered a natural and innovative alternative against antibiotic resistance, as it competes with many conventional antibiotics and even demonstrates superior performance against resistant bacteria. Scaglione and colleagues demonstrated that pomegranate peel extract of P. granatum exhibits antimicrobial activity against MDR Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and P. aeruginosa, and further reported that its bactericidal effect is dose- and time-dependent, with high concentrations also providing antioxidant protection to cellular systems and red blood cell membranes [46]. When the in vitro effect on cell viability (HeLa) was evaluated, no cytotoxic effect was observed at 50–150 μg/μL range [46]. The findings of this study indicated that the compound has the strongest antiproliferative effect on A549 cells at higher concentrations (>200 µg/mL) among the three cell lines (HeLa, A549, ARPE-19) tested, with comparatively lower cytotoxicity observed in HeLa and non-cancerous ARPE-19 cells.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Punica granatum peel extract (PGPE) has notable dose-dependent antibacterial activity. Encapsulation within chitosan (CH) significantly enhances its efficacy by reducing MIC values. Both PGPE and CH-PGPE exhibited stronger or equivalent inhibition than several standard antibiotics, with pronounced effects against resistant strains. CH-PGPE showed particularly strong inhibition against resistant strains, while maintaining biocompatibility with human cells. These results indicate the potential of combining plant-derived bioactive compounds with nanotechnological systems to improve antimicrobial efficacy. The chitosan-based nanoparticle form of PGPE may serve as a promising natural alternative or adjunct in addressing antimicrobial resistance.

Further work is required to establish safety profiles, optimal dosing strategies, pharmacokinetic parameters, anti-biofilm activity, and formulation stability. Comprehensive preclinical and clinical studies, including the evaluation of purified compound metabolism and therapeutic interactions, will be essential to advance CH-PGPE toward potential clinical application as an adjuvant or combination therapy.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the study. K.S. contributed to the methodology, supervision, and manuscript writing. S.S.A. conducted laboratory analysis, data collection, writing (original draft), and correspondence. I.B. contributed to microbiological assay design. Z.A.Y. conducted manuscript writing. B.O. conducted sample preparation and experimental supervision. N.E. contributed to cytotoxicity analyses, and E.Y. conducted phytochemical analysis. D.B.A. conducted nanoparticle characterization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been supported by the Recep Tayyip Erdogan University (RTEU) Development Foundation (Grant number: 02025012001834) and the RTEU Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (Grant No: TSA-2024-1619).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not involve humans or animals. All experiments were performed using in vitro methods in accordance with internationally accepted laboratory biosafety standards.

Informed Consent Statement

The study did not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Recep Tayyip Erdogan University for providing technical support and laboratory facilities used in this research. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AK | Amikacin |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| ATM | Aztreonam |

| CAZ | Ceftazidime |

| CH-PGPE | Chitosan-coated Punica granatum peel extract |

| CIP | Ciprofloxacin |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute |

| CTX | Cefotaxime |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin gallate |

| E | Erythromycin |

| FEP | Cefepime |

| FOX | Cefoxitin |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| I | Intermediate |

| IPM | Imipenem |

| LEV | Levofloxacin |

| LZD | Linezolid |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MEM | Meropenem |

| MHA | Mueller–Hinton agar |

| MHB | Mueller–Hinton broth |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MRSA | Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MSSA | Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus |

| MXF | Moxifloxacin |

| P | Penicillin |

| PGPE | Punica granatum peel extract |

| PRL | Piperacillin |

| R | Resistant |

| S | Susceptible |

| SXT | Sulphamethoxazole/trimethoprim |

| TZP | Tazobactam/piperacillin |

| VA | Vancomycin |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Karabay, O. Antibiotic consuption in Turkey and where the antibiotic resistance goes? ANKEM Derg. 2009, 23, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The Rational Use of Drugs: Report of the Conference of Experts, Nairobi, 25–29 November 1985; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987; p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- Christaki, E.; Marcou, M.; Tofarides, A. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria: Mechanisms, Evolution, and Persistence. J. Mol. Evol. 2020, 88, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreitmann, L.; Helms, J.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Salluh, J.; Poulakou, G.; Pène, F.; Nseir, S. ICU-acquired infections in immunocompromised patients. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovska, B.B. Historical review of medicinal plants’ usage. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2012, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricant, D.S.; Farnsworth, N.R. The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109 (Suppl. 1), 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- DeFelice, S.L. The nutraceutical revolution: Its impact on food industry R&D. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.; Jadhav, V.T.; Sharma, J. Global scenario of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) culture with special reference to India. Fruit Veg. Cereal Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 4, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Melgarejo-Sanchez, P.; Nunez-Gomez, D.; Martinez-Nicolas, J.J.; Hernandez, F.; Legua, P.; Melgarejo, P. Pomegranate variety and pomegranate plant part, relevance from bioactive point of view: A review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Dadmohammadi, Y.; Abbaspourrad, A. Nutritional and bioactive components of pomegranate waste used in food and cosmetic applications: A review. Foods 2021, 10, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, R.R.; Fawole, O.A.; Makunga, N.P.; Opara, U.L. Effect of drying on the bioactive compounds, antioxidant, antibacterial, and antityrosinase activities of pomegranate peel. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modaeinama, S.; Abasi, M.; Abbasi, M.M.; Esfahlan, R.J. Anti-tumoral properties of Punica granatum (pomegranate) seed extract in different human cancer cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 1119–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.Y.; Ma, N.; Pan, T.; Du, C.L.; Sun, J.Y. Punicagranine, a new pyrrolizine alkaloid with anti-inflammatory activity from the peels of Punica granatum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, P.M.; Gomes Fontoura, G.M.; Rodrigues, L.D.S.; Souza, A.S.; Viana, J.P.M.; Fernandes Pereira, A.L.; Dutra, R.P.; Nogueira Ferreira, A.G.; Neto, M.S.; Reis, A.S.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Punica granatum and Isolated Compounds: Evidence-Based Advances to Treat Bacterial Infections. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 4026440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wafa, B.A.; Makni, M.; Ammar, S.; Khannous, L.; Ben Hassana, A.; Bouaziz, M.; Es-Safi, N.E.; Gdoura, R. Antimicrobial effect of the Tunisian Nana variety Punica granatum L. extracts against Salmonella enterica (serovars Kentucky and Enteritidis) isolated from chicken meat and phenolic composition of its peel extract. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, D.; Ray, R.; Hazra, B. Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate fruit constituents against drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharm Biol. 2015, 53, 1474–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Rana, T.S.; Narzary, D.; Verma, N.; Meshram, D.T.; Ranade, S.A. Pomegranate biology and biotechnology: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 160, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksu, F.; Göktaş, M.A.; Tosya, F.; Bölek, S. Investigation of the effects of food matrix on bioavailability of phenolic compounds in foods. In Proceedings of the International Hazar Scientific Researches Conference–III, Baku, Azerbaijan, 7–9 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, S.H.; Kang, O.H.; Kong, R.; Zhou, T.; Kim, S.A.; Shin, D.W.; Kwon, D.Y. Punicalagin suppresses methicillin resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to oxacillin. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 137, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 16129719, Punicalagin. 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Punicalagin (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Mohan, M.; Mohanavarshaa, C.A.; Priya, D.; Anjana, G.V. Review of pharmacological and medicinal uses of Punica granatum. Cureus 2024, 16, e71510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.A.A.H.; Gad, M.F.; Abdelhafez, H.M.; Ebrahem Mersal, A.T.; Mossa, A.T.H. Phytochemical study, antioxidant potential and preparation of a clove nanoemulsion loaded with pomegranate peel extract. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 65064, Epigallocatechin Gallate. 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Epigallocatechin-Gallate (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Lou, F.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Shi, Y. Investigation of the inhibitory effect and mechanism of epigallocatechin-3-gallate against Streptococcus suis sortase A. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Li, J.; Cai, Q.; Deng, C.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, X.; Cheng, B. Exploring the antibiofilm potential of chitosan nanoparticles by functional modification with chloroquine and deoxyribonuclease. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 347, 122726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Martinez, F.J.; Rodríguez, J.C.; Borras-Rocher, F.; Barrajon-Catalan, E.; Micol, V. The antimicrobial capacity of Cistus salviifolius and Punica granatum plant extracts against clinical pathogens is related to their polyphenolic composition. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Silva, S.; Santos, S.A.O.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Duarte, M.F.; Saraiva, J.A.; Pintado, M. Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate peel extracts performed by high pressure and enzymatic assisted extraction. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doğanyiğit, Z.; Küp, F.Ö.; Kaymak, E.; Okan, A.; Oçak, B.; Akin, A.T. Effect of Grape Seed Extract of Silver Nanoparticles on TNF-α and BNP Expression and Histologic Changes in Endotoxic Heart Tissue. Bozok Tıp Derg. 2019, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Imeri, A.G.; Knorr, D. Effect of chitosan on yield and compositional data of carrot and apple juice. J. Food Sci. 1988, 53, 1707–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyis, F.; Yurteri, E.; Ozcan, A.; Cirak, C. Altitudinal impacts on chemical content and composition of Hypericum perforatum, a prominent medicinal herb. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 135, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subair, S.; Singh, N.; Maru, M.; Prakash, S.; Hasanar, M. An Antimicrobial Fabric Using Nano-Herbal Encapsulation of Essential Oils. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, 194, e65187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytar, M.; Oryaşın, E.; Başbülbül, G.; Bozdoğan, B. Agar Well Difüzyon Yönteminde Standardizasyon Çalışması. Bartın Univ. Int. J. Nat. Appl. Sci. (JONAS) 2019, 2, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mossmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, K.; Sahin Aktura, S.; Bahceci, I.; Mercantepe, T.; Tumkaya, L.; Topcu, A.; Mercantepe, F.; Duran, O.F.; Uydu, H.A.; Yazici, Z.A. Is Punica granatum Efficient Against Sepsis? A Comparative Study of Amifostine Versus Pomegranate. Life 2025, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin Aktura, S.; Sahin, K.; Tumkaya, L.; Mercantepe, T.; Topcu, A.; Pinarbas, E.; Yazici, Z.A. The Nephroprotective Effect of Punica granatum Peel Extract on LPS-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Life 2024, 14, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraballo, C.; Jaimes, F. Organ dysfunction in sepsis: An ominous trajectory from infection to death. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2019, 92, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.G.; Kang, O.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Chae, H.S.; Oh, Y.C.; Brice, O.O.; Kim, M.S.; Sohn, D.H.; Kim, H.S.; Park, H.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Antibacterial Activity of Punica granatum Peel Ethanol Extract against Salmonella. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 690518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, H.; Vaara, M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol. Rev. 1985, 49, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, P.S.; Jayaprakasha, G.K. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Punica granatum peel extracts. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, S.H.; Mashouf, R.; Mortazavi, H.; Moghaddam, M.; Roozbahani, N.; Vahedi, M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of Punica granatum peel extracts against oral pathogens. J. Dent. 2011, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kharchoufi, S.; Licciardello, F.; Siracusa, L.; Muratore, G.; Hamdi, M.; Restuccia, C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant features of ‘Gabsi’ pomegranate peel extracts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarulo, C.; De Vito, V.; Picariello, G.; Colicchio, R.; Pastore, G.; Salvatore, P.; Volpe, M.G. Inhibitory effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) polyphenol extracts on the bacterial growth and survival of clinical isolates of pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.I.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Hess-Pierce, B.; Holcroft, D.M.; Kader, A.A. Antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and its relationship with phenolic composition and processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 4581–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan-Koç, B.; Türkyılmaz, M.; Yemiş, O.; Özkan, M. Effects of various protein- and polysaccharide-based clarification agents on antioxidative compounds and colour of pomegranate juice. Food Chem. 2015, 184, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglione, E.; Sateriale, D.; Mantova, G.; Di Rosario, M.; Continisio, L.; Vitiello, M.; Pagliarulo, C.; Colicchio, R.; Pagliuca, C.; Salvatore, P. Antimicrobial efficacy of Punica granatum Lythraceae peel extract against pathogens belonging to the ESKAPE group. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1383027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosset-Erard, C.; Zhao, M.; Lordel-Madeleine, S.; Ennahar, S. Identification of punicalagin as the bioactive compound behind the antimicrobial activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peels. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.A.M.; Grinholc, M.; Dena, A.S.A.; El-Sherbiny, I.M.; Megahed, M. Boosting the antibacterial activity of chitosan-gold nanoparticles against antibiotic-resistant bacteria by Punicagranatum L. extract. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 256, 117498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.I.; Mahmoud, N.M.R.; Ramadan, A.; Al-Subaie, A.M.; Ahmed, S.B. Novel Biological-Based Strategy for Synthesis of Green Nanochitosan and Copper-Chitosan Nanocomposites: Promising Antibacterial and Hematological Agents. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).