Abstract

Parathyroid carcinoma (PC) is an exceedingly rare endocrine malignancy, accounting for less than 1% of all primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT) cases. It typically presents with pronounced hypercalcemia and markedly elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. Accurate imaging plays a pivotal role in diagnosis, staging, surgical planning, and long-term surveillance, although differentiating PC from benign disease on imaging remains a significant challenge. A multimodal imaging strategy combining cervical ultrasonography (US) and nuclear medicine techniques provides high sensitivity for lesion detection. Ultrasonography with advanced detective flow imaging allows detailed anatomical assessment and evaluation of vascular patterns of the primary tumor. [99mTc]Tc-methoxyisobutylisonitrile ([99mTc]Tc-MIBI) scintigraphy frequently demonstrates prolonged tracer retention in PC, while [18F]fluorocholine positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) and positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance (PET/MR) imaging have shown superior performance for detecting both primary tumors and metastatic disease due to its higher spatial resolution and higher molecular sensitivity. [18F]FDG PET serves as an adjunct modality for identifying aggressive, metabolically active lesions. Emerging radiotracers such as [18F]-fibroblast activation protein inhibitor ([18F]FAPI) and [68Ga]Ga-trivehexin have shown potential in cases where initial imaging is inconclusive. Theranostic strategies that integrate molecular imaging with targeted radioligand therapy may transform PC management by enabling personalized treatment approaches tailored to each tumor’s biological and imaging characteristics. This review aims to evaluate available imaging modalities for PC diagnosis and provide guidance for their clinical application.

1. Introduction

Parathyroid carcinoma is an exceptionally rare endocrine malignancy, with an estimated incidence of 3.5 to 5.7 cases per 10 million individuals. The disease was first described in 1904 by Swiss surgeon Fritz de Quervain, who referred to it as “parastruma maligna aberrata” [1,2]. Globally, the disease represents less than 0.005% of all cancers [3] and accounts for fewer than 1% of pHPT cases [4]. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years, with a slightly higher prevalence among men, particularly within Caucasian populations (around 75% of cases) [5]. Clinically, PC is characterized by markedly elevated PTH levels and significant hypercalcemia, leading to a spectrum of symptoms that range from mild fatigue and nausea to severe complications such as renal failure and pathological fractures [6,7,8,9]. Although PC generally follows a slow growth pattern, it carries substantial morbidity due to recurrent or persistent hypercalcemia and its tendency to metastasize, most commonly to the bones, lungs, and liver [8].

The most common clinical manifestations of PC arise from skeletal and renal complications secondary to severe hyperparathyroidism. Bone-related symptoms include pain, pathological fractures, and osteoporosis, while renal manifestations such as nephrolithiasis and renal insufficiency are also frequent. Less common but clinically relevant findings include generalized weakness (asthenia) and cervical compression symptoms—such as dysphonia, dysphagia, or dyspnea—resulting from tumor mass effect, which is palpable in approximately 15–50% of cases. Additional signs of severe hypercalcemia may include polyuria–polydipsia syndrome, nausea, vomiting, neuropsychiatric disturbances, peptic ulcer disease, and acute pancreatitis [10,11].

From a biochemical standpoint, hypercalcemia in PC is typically severe, with serum calcium often exceeding 140 mg/L (3.5 mmol/L). Elevated alkaline phosphatase and markedly increased PTH levels (ranging from three- to tenfold above the upper reference limit) are characteristic findings [4]. In a retrospective study of 131 Japanese patients with pHPT (111 with benign parathyroid lesions and 20 with PC), those with PC exhibited significantly higher mean serum calcium (12.7 mg/dL vs. 11.6 mg/dL) and PTH levels (397 pg/mL vs. 228 pg/mL) compared with benign cases [12]. Circulating PTH thus remains a key biomarker for detecting recurrence and monitoring disease progression.

PC may occasionally present with acute symptoms, including encephalopathy, vomiting, cardiac arrhythmia, and acute renal failure, all associated with a significant rise in PTH levels and severe hypercalcemia, the so-called parathyroid crisis. This represents a medical emergency that requires rapid intervention to manage hypercalcemia, typically through the administration of intravenous isotonic saline, with or without loop diuretics. Additional treatments, such as biphosphonates, cinacalcet, and calcitonin, can provide temporary relief. However, the definitive treatment of parathyroid crisis remains surgical parathyroidectomy [13].

The main goals of surgical management in PC are to evaluate tumor invasiveness, prevent further metastatic dissemination, and alleviate the systemic effects of excessive PTH secretion [14]. Achieving these objectives requires a precise and thorough preoperative diagnostic assessment to guide the optimal treatment strategy. The surgical state-of-the-art treatment for localized PC is an en bloc resection of the parathyroid tumor along with surrounding adipose tissue, the ipsilateral thyroid lobe, combined with ipsilateral central neck dissection to ensure a continuous margin of healthy tissue [14].

In most cases, PC is not recognized before surgery; the diagnosis is usually confirmed by histopathology following resection. The disease is characterized by its aggressive clinical behaviour, with regional lymph node metastases observed in 15–30% and distant metastasis in up to 30% at the time of diagnosis. Consequently, effective treatment often requires a multimodal approach integrating surgery with adjuvant or targeted therapies to address both local and systemic disease components.

Patients with metastatic PC generally have poor prognoses, especially when metastases are hormonally active and continue to secrete PTH. Surgical intervention remains the cornerstone of management, as both external radiotherapy and chemotherapy have shown limited therapeutic benefit. Reported five-year overall survival ranges from 60% to 95%, while recurrence occurs in approximately 30–67% of cases. These figures highlight the critical importance of advanced imaging techniques for early diagnosis, precise staging, and vigilant long-term monitoring [4].

Imaging plays an increasingly vital role in PC management—facilitating accurate tumor localization, differentiation from benign lesions where feasible, assessment of local invasion and distant metastases, surgical planning, and detection of recurrence. This comprehensive review explores the full spectrum of diagnostic imaging strategies for PC, emphasizing recent technological advances in diagnostic and monitoring capabilities. Modern approaches integrate multiple complementary modalities, including US with detective flow imaging and advanced nuclear medicine techniques, the latter offering not only superior diagnostic accuracy but also promising avenues for future therapeutic applications.

This review aims to comprehensively evaluate available imaging modalities for PC diagnosis, compare their diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility, and provide practical guidance for imaging strategy selection in suspected PC cases.

2. Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is a key diagnostic modality for detecting parathyroid lesions and is widely used as the first-line imaging technique owing to its broad availability, non-invasiveness, cost-effectiveness, and ability to provide real-time evaluation of cervical anatomy. It plays a central role in the initial assessment of suspected parathyroid disease and can offer valuable clues suggestive of malignancy.

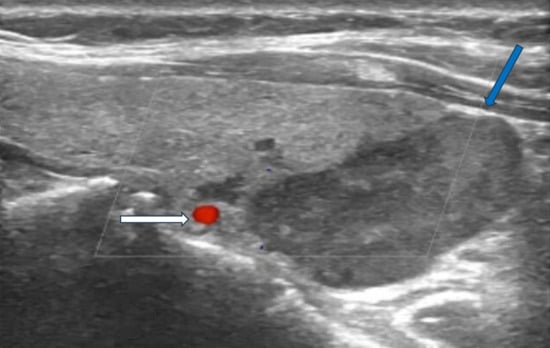

Sonographic features indicative of PC typically include lesion size greater than 3 cm, substantially larger than typical benign adenomas, which generally measure 1–2 cm. Malignant lesions often exhibit irregular or lobulated margins with evidence of invasion into adjacent tissues, in contrast to the smooth, well-circumscribed borders characteristic of benign counterparts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography image of parathyroid carcinoma. Legend: 65-year-old patient with parathyroid carcinoma presented with serum PTH of 1300 pg/mL (12–88 pg/mL) and Ca:13 mg/dL (8.8–10.6 mg/dL). Ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic mass with lobulated borders (32 × 23 × 14 mm) next to the lower pole of the left thyroid lobe (blue arrow). The white arrow shows the inferior thyroid artery.

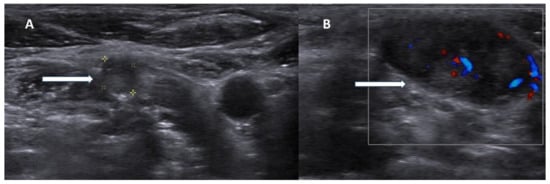

Additional suspicious findings include a heterogeneous echotexture with marked hypoechogenicity, reflecting necrosis, hemorrhage, or fibrosis, and a depth-to-width ratio of ≥1, as malignant lesions tend to be taller than wide. The presence of intralesional calcifications and cervical lymphadenopathy further strengthens the suspicion for carcinoma [2,15,16] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ultrasonography images of parathyroid carcinoma neck metastases. Legend: 70-year-old patient presented with parathyroid carcinoma lymph node metastases with hypoechoic lesions without fatty hilum ((A), white arrow) and chaotic blood flow in Doppler imaging ((B), white arrow).

However, these sonographic characteristics often overlap with those of large or atypical benign adenomas, and no single US feature is pathognomonic for malignancy. Conventional US achieves a sensitivity of approximately 76.1% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of approximately 93.2% for identifying parathyroid lesions [17], yet its ability to distinguish benign from malignant pathology remains limited. Moreover, as an operator-dependent technique, US demands substantial experience and specialized expertise in parathyroid imaging to ensure accuracy and reproducibility (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sonographic features suggestive of parathyroid carcinoma.

Recent technological advances have improved the diagnostic performance of US through detective flow imaging, a novel technique that surpasses traditional color Doppler in detecting slow microvascular blood flow. A 2024 study by Matsui et al. highlights its clinical utility, demonstrating successful visualization of low-velocity flow patterns within parathyroid tumors. This method enabled the detection of vascular-rich PC and provided valuable insights into lesion microvascularity, thereby enhancing diagnostic confidence in differentiating PC from benign disease [18].

While detective flow imaging offers a promising non-invasive advancement in enhancing the diagnostic accuracy of US, several important limitations must be acknowledged. The method requires dedicated high-performance equipment and operators with specialized training, which may restrict its availability to expert centers. Furthermore, larger prospective validation studies are needed to define standardized diagnostic criteria, establish sensitivity and specificity for malignancy detection, and ensure reproducibility across institutions.

The use of US-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for parathyroid lesions is a matter of discussion. The procedure can be performed with several passes to obtain enough cells for cytological evaluation or it can be performed as a simple PTH washout test, in which the physician performs fewer passes and rinses the biopsy needle with a saline solution to detect PTH levels; i.e., fine-needle aspiration-PTH (FNA-PTH). FNA-PTH washout test is a safe procedure with low risk of complications and high sensitivity and specificity (≥90%) for parathyroid lesions [19,20,21]. From a procedural standpoint, although no data for only FNA-PTH is available, FNAC is contraindicated in suspected PC for two key reasons: first, cytology cannot reliably differentiate benign from malignant parathyroid lesions due to overlapping cellular morphology; and second, there is a risk of tumor seeding along the needle tract, potentially leading to local recurrence or dissemination of malignant cells [22,23,24]. However, the decision for FNA may be challenging. If there is a high suspicion of PC or if there is a recurrent lesion after parathyroid cancer surgery, FNAC should be avoided. In such cases, the necessity for FNAC is also questionable, since surgical excision is recommended.

In parallel, recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced new opportunities for non-invasive diagnosis. A recent retrospective study involving 913 surgically confirmed cases (823 benign adenomas, 90 malignant or atypical lesions) applied radiomics-based machine learning models to US imaging [25]. Among the tested algorithms, the Random Forest model demonstrated the highest diagnostic performance (AUC 0.933, accuracy 0.940), significantly outperforming support vector machine and logistic regression classifiers. These findings highlight the potential of radiomics-assisted US as a valuable preoperative tool for distinguishing PC from benign adenomas and for improving clinical decision-making in parathyroid imaging.

3. [99mTc]Tc-MIBI Scintigraphy

[99mTc]Tc-MIBI scintigraphy of the parathyroid glands, first described by Coakley et al. in 1989 [26], remains a valuable imaging technique for the evaluation of PC, as these tumors generally exhibit intense radiotracer uptake. [99mTc]Tc-MIBI is a lipophilic, cationic compound widely used in parathyroid imaging that accumulates within mitochondria-rich cells, thereby reflecting both perfusion and metabolic activity. Uptake occurs in two phases: an initial distribution phase driven by tissue perfusion and cellular metabolism, followed by mitochondrial sequestration linked to the high negative transmembrane potential. Differential tracer washout between parathyroid and thyroid tissue forms the basis of lesion detection [27,28,29,30].

Standard dual-phase protocols involve early-phase imaging at 10–15 min post-injection to assess initial distribution and delayed-phase imaging at 1.5–2.5 h post-injection to assess tracer retention. In suspected PC, whole-body imaging is recommended to assess for potential metastatic spread. Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) enhances planar imaging by providing three-dimensional localization and improved anatomical correlation. While normal parathyroid and thyroid tissues exhibit rapid [99mTc]Tc-MIBI washout, hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue –both benign and malignant—demonstrates prolonged retention, allowing for distinction on delayed imaging. Alternatively, subtraction scintigraphy combining [99mTc]Tc-MIBI with thyroid tracers such as [99mTc]pertechnetate or Na [123I]I, improves the detection and localization of hyperfunctioning parathyroid lesions beyond that achieved with dual-phase protocols [31,32,33,34].

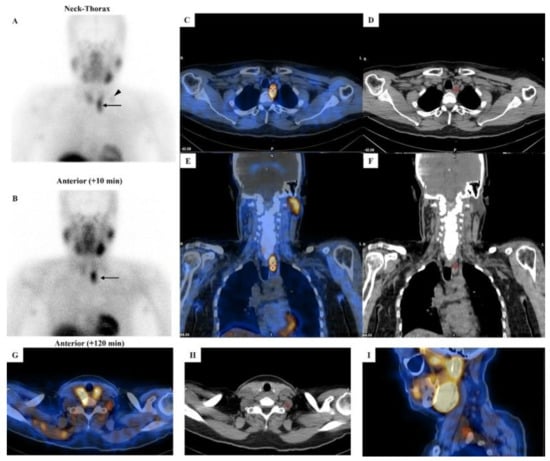

When combined with the US, [99mTc]Tc-MIBI scintigraphy achieves sensitivities of 81–95% for detecting hyperfunctioning parathyroid lesions [35,36,37]. Importantly, tracer retention patterns may suggest malignancy. Zhang et al. demonstrated that PCs exhibit significantly higher retention indices compared to benign parathyroid lesions, with distinct differences in both mean and peak retention values [38]. This finding highlights the potential of retention analysis as a non-invasive preoperative tool for differentiating malignant from benign parathyroid disease (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

[99mTc]Tc-MIBI imaging in a patient with parathyroid carcinoma. Legend: A 52-year-old man affected by pHPT [intact PTH = 421.6 pg/mL (8–76), total calcium = 12.1 mg/dL (8.2–10.4), ionized calcium = 1.82 mmol/L (1.10–1.30)] due to PC. Neck ultrasound showed a hypoechoic and heterogeneous parathyroid lesion (28 mm in maximum size) close to the lower pole of the left thyroid lobe. Dual-phase parathyroid scintigraphy was performed using [99mTc]Tc-MIBI. Panels (A,B): Planar parathyroid images (anterior views) were obtained 10 and 120 min after [99mTc]Tc-MIBI administration (400 MBq). Early (panel (A)) and late (panel (B)) images showed a well-defined area of abnormal and intense tracer uptake located at the lower pole of the left thyroid lobe (black arrow). At visual assessment (i.e., qualitative analysis), the late image (panel (B)) showed a significant tracer retention in the parathyroid lesion. Using a semiquantitative approach, the peak Retention Index (RI) was suspicious for PC (peak RI = 11.45%). Panels (C,E): SPECT/CT imaging was acquired 130 min after [99mTc]Tc-MIBI administration. Axial (panel (C)) and coronal (panel (E)) images confirmed an abnormal tracer uptake located lower than the inferior pole of the left thyroid lobe (red cross-mark). At neck-thorax CT performed without contrast agent media administration (panels (D,F)), a large-sized (28 mm in maximum diameter) and non-homogeneous parathyroid lesion was noted just lower with respect to the inferior pole of the left thyroid lobe (red cross-mark). In addition, a faint but focal and abnormal tracer uptake was noted at the early planar image (panel (A)) in the middle-lower part of the left lateral neck (black arrowhead), consistent with lymph-node metastasis, which was then confirmed by hybrid imaging (red cross-mark in panels (G–I)).

Semi-quantitative evaluation methods—such as delayed-to-early uptake ratio, tumor-to-background ratio on delayed images, and washout rate calculations—have been explored for preoperative differentiation [39]. However, retention indices can overlap between benign and malignant lesions, particularly in small tumors. Hence, further validation and methodological standardization are needed before these parameters can be integrated into routine clinical practice.

Interestingly, some reports describe absent tracer uptake in the primary tumor but increased uptake in metastases, underscoring the heterogeneous tracer kinetics of PC [40]. Despite the valuable diagnostic insights provided by [99mTc]Tc-MIBI scintigraphy, complementary imaging with [18F]fluorocholine PET/CT(MR) imaging is often required, given its superior sensitivity and spatial resolution for detecting both primary and metastatic disease [2] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Imaging modalities for parathyroid carcinoma.

4. [18F]fluorocholine PET

PET/CT(MR) imaging has emerged as a powerful tool for evaluating PC, offering superior spatial resolution and sensitivity compared to [99mTc]Tc-MIBI scintigraphy. Imaging with 18F-labeled choline analogs demonstrates high diagnostic efficacy for detecting both primary and metastatic PC lesions, with growing evidence supporting its value [2], even in non-secreting PTH cases [41].

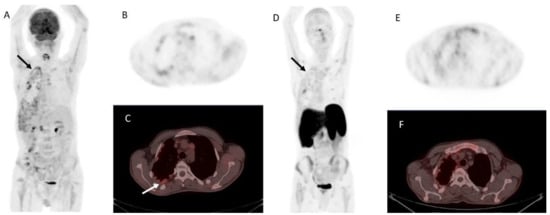

[18F]fluorocholine is a PET tracer that undergoes phosphorylation by choline kinase, an enzyme central to phospholipid synthesis in cell membranes. Hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue—particularly adenomas and carcinomas—shows upregulated choline metabolism, leading to marked tracer accumulation. Compared to traditional scintigraphy, [18F]fluorocholine PET/CT(MR) imaging provides several key advantages: markedly improved spatial resolution (4–5 mm vs. 10–15 mm), shorter acquisition time (approximately 30 min vs. 2–3 h), higher contrast-to-background ratio, and lower radiation exposure, particularly when performed with PET/MR imaging [42]. Figure 4. demonstrates an example of PC detected on [18F]fluorocholine PET/CT.

Figure 4.

A 73-year-old woman with primary hyperparathyroidism due to parathyroid carcinoma. Legend: (A) Coronal [18F]fluorocholine PET maximum intensity projection (MIP) image demonstrates an intensely tracer-avid lesion in the neck (black arrow, SUVmax 18.9). (B) Axial fused [18F]fluorocholine PET/CT image shows the tumor (white arrow) located deep to the right lobe of the enlarged thyroid gland. (C) On the corresponding unenhanced CT image, there is loss of the fat plane between the tumor (white arrows) and surrounding structures, with intralesional stippled calcifications visible (white arrowheads).

Several case reports and small cohort studies have confirmed the ability of [18F]fluorocholine PET to detect primary PC, local recurrences, regional lymph node metastases, and distant metastases to sites such as bone and lung, as well as other organs [41,43,44,45]. Notably, one case demonstrated the value of this modality in identifying an [18F]fluorocholine-positive PC metastasis in the skull base, which was subsequently removed via a transnasal-transpterygoid endoscopic approach [46]. Another report described bone and pulmonary lesions visible on [18F]fluorocholine PET but not on [18F]FDG PET/CT, highlighting the complementary role of both tracers [47].

A notable limitation, as with all radiotracers, is that [18F]fluorocholine PET cannot reliably distinguish benign adenomas from localized PC, as both demonstrate increased choline metabolism with overlapping standardized uptake values (SUV). However, the presence of a large cervical mass with intralesional calcifications, in conjunction with pathologic lymph nodes or lesions suspicious for distant metastases, is highly suggestive of PC rather than benign disease. Hence, when malignancy is clinically suspected, whole-body [18F]fluorocholine PET/CT(MR) imaging is recommended for comprehensive staging.

5. [11C]-Labeled Tracers

Carbon-11-labeled choline ([11C]CH) tracers share a similar uptake mechanism with [18F]fluorocholine and can be useful, particularly when conventional imaging methods such as US and [99mTc]Tc-MIBI scintigraphy fail to localize parathyroid lesions [48,49,50]. However, evidence supporting their effectiveness in detecting PC is lacking.

[11C]methionine ([11C]MET) has been applied as a second-line imaging option for identifying hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue in cases with inconclusive conventional imaging, demonstrating higher sensitivity than [99mTc]Tc-MIBI or US [51,52,53,54]. Nonetheless, its performance is inferior to that of [18F]fluorocholine [55,56,57] and [11C]CH [57]. [11C]MET uptake reflects amino acid metabolism and PTH precursor synthesis, providing complementary metabolic information distinct from [18F]FDG or [18F]fluorocholine [30,52,58]. In an isolated report, [11C]MET PET has successfully detected local recurrence even when both [99mTc]Tc-MIBI and [18F]FDG PET/CT were negative [59].

The major limitation of carbon-11-labeled tracers is their short physical half-life of approximately 20 min, necessitating on-site cyclotron production. This logistical constraint restricts their availability to specialized centers and limits their broader clinical use in PC imaging compared to [18F]fluorocholine. Another limitation is their inferior imaging characteristics.

6. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) serves as a complementary imaging modality in PC assessment, particularly for evaluating treatment response in advanced disease. As a glucose analog, [18F]FDG accumulates in tissues with high glycolytic activity [60,61]. Benign parathyroid lesions generally demonstrate low (to moderate) [18F]FDG uptake (with a variable sensitivity of 0–94% and a PPV of 62–100% [62]), whereas PCs frequently exhibit markedly increased [18F]FDG avidity, consistent with their aggressive biological behavior and higher proliferation rate [47,63,64,65,66,67]. [18F]FDG PET/CT (MR) imaging is especially valuable for detecting regional and distant metastases of less differentiated PCs that exhibit increased glucose consumption [16].

Key indications for [18F]FDG PET/CT (MR) imaging in PC encompass initial staging when PC is confirmed or highly suspected to assess for local invasiveness as well as distant metastases. Aggressive disease is often characterized by substantially elevated calcium and PTH levels reflecting their biology. Other important indications include surveillance monitoring of metastatic disease and treatment response assessment [16,63]. In cases with aggressive local tumor progression or metastatic disease, [18F]FDG PET may complement [18F]fluorocholine by localizing lesions with high metabolic activity [2,67].

A critical interpretive limitation lies in the potential misidentification of brown tumors or osteolytic lesions secondary to severe pHPT as metastases [68,69,70,71,72]. Brown tumors—benign osteolytic lesions driven by excess osteoclast activity—often display moderate, sometimes high metabolic activity on [18F]FDG PET, presumably owing to the elevated metabolic activity of osteoclasts and accompanying inflammatory cells [73,74]. Correlation with CT or MR imaging is therefore essential, as brown tumors typically appear as well-circumscribed lytic “soap-bubble” lesions, which are commonly found in the mandible, clavicle, ribs, and pelvis [75]. Resolution of uptake following correction of hypercalcemia further supports their benign nature, while biopsy may be reserved for ambiguous cases, given the risk of tumor seeding.

7. Dual-Tracer PET Strategy

A sequential dual-tracer PET strategy combining [18F]fluorocholine and [18F]FDG offers complementary insights into PC biology and may provide substantially enhanced disease staging and progression monitoring. Whereas [18F]fluorocholine reflects increased cell membrane turnover via upregulated specific choline metabolism, [18F]FDG highlights glycolytic activity associated with tumor aggressiveness. Utilizing both tracers would allow for the detection of lesions with distinct metabolic phenotypes—ranging from highly proliferative, glucose-avid tumors to those exhibiting lower glycolytic rates but active membrane synthesis.

Clinical evidence supports the diagnostic synergy of this approach. Several reports have shown [18F]fluorocholine PET/CT identifying additional metastatic foci not visualized with [18F]FDG PET/CT alone, thereby broadening the scope of metastatic disease evaluation [43,47,67]. Conversely, more aggressive or dedifferentiated lesions may demonstrate preferential [18F]FDG uptake.

Accordingly, the dual-tracer strategy holds particular value for initial staging in confirmed PC, comprehensive preoperative assessment prior to resection of metastases, and selection of optimal biopsy sites, providing a more complete depiction of tumor heterogeneity and metabolic activity.

8. Novel Tracers and Potential Applications

Recent advances in molecular imaging have introduced novel PET tracers that may expand diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities in parathyroid carcinoma. A recent case report suggests that [18F]FAPI PET/CT can effectively detect PC metastases, particularly in patients with biochemical evidence of disease recurrence but negative findings in [18F]FDG and choline-based imaging [76]. Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor tracers selectively target cancer-associated fibroblasts within the tumor microenvironment. This observation highlights the potential role of [18F]FAPI not only in improved disease localization but also in the emerging field of receptor-directed theranostics, potentially enabling personalized radioligand therapy in PC management.

Similarly, another novel radiotracer, [68Ga]Ga-Trivehexin, targets the αvβ6 integrin receptor and has shown promise in early clinical application [77]. In a recently reported case of recurrent PC, [68Ga]Ga-Trivehexin PET/CT successfully detected both local recurrence and pulmonary metastases, whereas [18F]FDG PET/CT and [99mTc]Tc-MIBI SPECT/CT yielded negative or inconclusive findings. These preliminary results suggest that integrin-targeted imaging may be valuable when conventional modalities fail, warranting further systematic investigation.

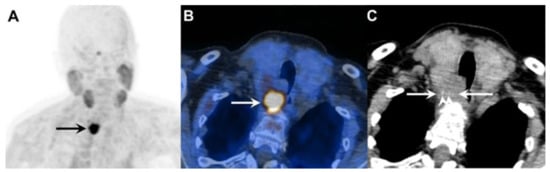

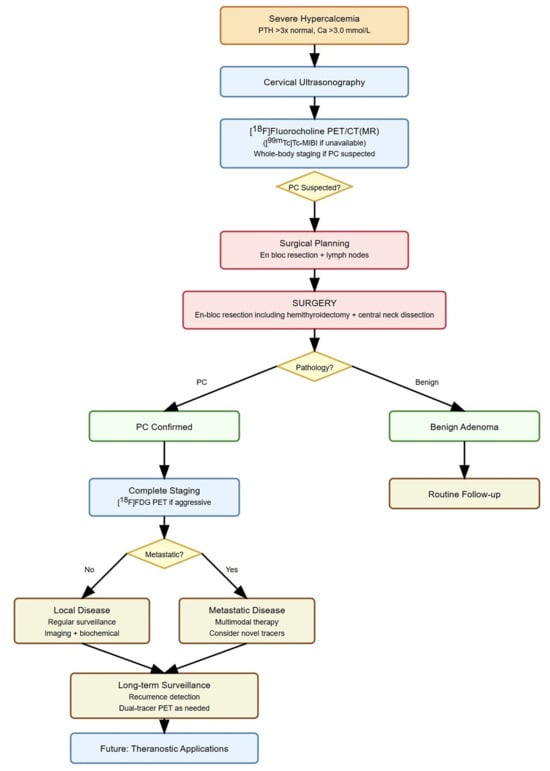

In addition, parathyroid tissue—both benign and malignant—may express somatostatin receptors (SSTR) [78]. A study by Storvall et al. demonstrated SSTR expression across all parathyroid tumor subtypes—including typical adenomas, atypical adenomas, and PCs—predominantly within the cytoplasm rather than on the cell membrane. Among receptor subtypes, SSTR 1 showed uniform expression, while SSTR 2–5 varied by tumor type. Notably, PC exhibited consistently high levels of SSTR expression, particularly SSTR 5, while adenomas demonstrated only minimal expression. The marked difference in cytoplasmic SSTR 5 expression rates between parathyroid tumors may serve as a potential malignancy indicator [79]. These findings support the biological rationale for SSTR-based imaging [80] and potential theranostic applications using peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Metastatic parathyroid carcinoma on [18F]FDG PET/CT and [68Ga]Ga DOTA-TATE PET/CT. Legend: A 72-year-old patient with metastatic parathyroid carcinoma. He had elevated Ca levels of 13.5 mg/dL (8.8–10.6 mg/dL) and PTH levels of 11,663 (12–88 pg/mL) after repeated surgeries and tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. [18F]FDG PET/CT shows extensive pleural metastases ((A), whole-body MIP image, black arrow; (B), axial MIP; (C), PET/CT, white arrow). [68Ga]Ga DOTA-TATE PET/CT was acquired to evaluate options for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy ((D), whole-body MIP image; (E), axial MIP; (F), PET/CT). Unfortunately, there was a faint uptake lower than the physiological liver uptake, rendering the patient ineligible for PRRT.

However, clinical evidence remains limited. At present, SSTR imaging is not recommended as a standard diagnostic tool in PC but may be considered selectively in patients with high receptor expression where PRRT is being contemplated as a therapeutic option (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Molecular imaging in parathyroid carcinoma management. Legend: PC, parathyroid carcinoma; PET/CT(MR), positron emission tomography/computed tomography (magnetic resonance) imaging.

Although no direct head-to-head comparison of [99mTc]Tc-MIBI and [18F]fluorocholine in PC has been published, the available data on diagnostic accuracy and management impact clearly favor [18F]fluorocholine. Additionally, whole-body cross-sectional imaging with [18F]fluorocholine is much quicker than with [99mTc]Tc-MIBI, taking approximately 15 min for [18F]fluorocholine PET/CT or PET/MR imaging, compared to about 2 h for [99mTc]Tc-MIBI SPECT/CT.

9. Conclusions

The diagnosis and management of PC have evolved substantially with the integration of US and molecular imaging technologies. Ultrasonography, particularly when enhanced by detective flow imaging, has improved the assessment of tumor vascularity and tissue architecture, although its accuracy remains highly operator-dependent. Nuclear medicine imaging continues to play a pivotal role in longitudinal monitoring. In selected cases, combining nuclear medicine imaging techniques—such as dual-tracer PET imaging with [18F]fluorocholine and [18F]FDG—can provide complementary biological information, supporting more precise staging and targeted treatment planning. Whole-body imaging is essential to identify distant metastases, distinguishing PC from benign parathyroid lesions, where imaging is typically confined to the neck and mediastinum.

Emerging novel PET tracers such as [18F]FAPI and [68Ga]Ga-trivehexin have demonstrated potential in identifying PC lesions that are undetectable with other tracers, offering new diagnostic pathways in complex or recurrent cases.

Looking ahead, the future of PC imaging is likely to be shaped by the development of theranostic strategies that integrate diagnostic imaging with targeted radioligand therapy. Such precision medicine approaches, grounded in the molecular and metabolic characteristics of individual tumors, could transform PC management from a predominantly surgical disease to one guided by personalized, image-based systemic treatment paradigms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.O., L.G. and M.W.H.; methodology, P.P.O., L.G. and M.W.H.; investigation, P.P.O., L.G. and M.W.H.; data curation, P.P.O., L.G., A.C., M.T., R.M.R. and M.W.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.O. and M.W.H.; writing—review and editing, P.P.O., L.G., M.T., J.I.I., V.L., M.R., D.D., R.M.R., F.V., A.C. and M.W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

L.G. received research grants and speaker fees not related to the present work from Roche Diagnostics (Switzerland). M.W.H. received grants and speaking fees from GE HealthCare, a grant from the Clinical Research Priority Program (CRPP) on Artificial Intelligence in Oncological Imaging at University Hospital Zurich, and funding from the Alfred and Annemarie von Sick legacy. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- de Quervain, F. Parastruma Maligna Aberrata. Dtsch. Z. Chir. 1909, 100, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranović Ovčariček, P.; Campennì, A.; Giovanella, L.; Huellner, M.W. Parathyroid Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Analysis with Focus on Molecular Imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2025, 52, 2754–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, A.; Drakou, E.E.; Lajeunesse-Trempe, F.; Grossman, A.B.; Dimitriadis, G.K. Parathyroid Carcinoma: New Insights. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 32, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantyghem, M.-C.; Mirallié, E.; Al-Salameh, A.; Aubert, S.; Barraud, S.; Baud, G.; Hamou, A.B.; Bertocchio, J.-P.; Borson-Chazot, F.; Bouillet, B.; et al. French Expert Consensus Statement on Diagnosis and Management of Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Ann. Endocrinol. 2025, 86, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Khan, J.; Waheed, A.; Sharma, N.; Pryor, E.K.; Stumpe, T.R.; Zarate, L.V.; Cason, F.D.; Kumar, S.; Misra, S.; et al. Parathyroid Carcinoma: Incidence, Survival Analysis, and Management: A Study from the SEER Database and Insights into Future Therapeutic Perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetani, F.; Pardi, E.; Torregrossa, L.; Borsari, S.; Pierotti, L.; Dinoi, E.; Marcocci, C. Approach to the Patient with Parathyroid Carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzaro, A.; Zhao, G.; Kulke, M. Diagnosis and Management of Parathyroid Carcinoma. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 116, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboobipour, A.A.; Pourabdollah, M.; Hadaegh, F.; Herik Dizaji, M.; Tavangar, S.M.; Shadmehr, M.B. Metastatic Parathyroid Carcinoma Diagnosed after Five Surgical Attempts: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 19, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traini, E.; Lanzafame, A.; Carnassale, G.; Daloiso, G.; Borghesan, N.; Sanchez, A.M.; Mattia, A. Synchronous Multiple Parathyroid Carcinoma: A Challenging Diagnosis Influencing Optimal Primary Treatment-A Literature Review to Guide Clinical Decision-Making. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Arya, A.K.; Bhadada, S.K.; Saikia, U.N.; Sood, A.; Dahiya, D.; Behera, A. Parathyroid Carcinoma: An Experience from the Indian Primary Hyperparathyroidism Registry. Endocr. Pract. 2021, 27, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Lyu, Z.H.; Ba, J.M.; Pei, Y.; Dou, J.T.; Gu, W.J.; Du, J.; Guo, Q.H.; Chen, K.; et al. Parathyroid Carcinoma: Report of 10 Patients and Literature Review. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2022, 43, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Kaji, H.; Nomura, R.; Sowa, H.; Yamauchi, M.; Tsukamoto, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Sugimoto, T.; Chihara, K. Trial to Predict Malignancy of Affected Parathyroid Glands in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Endocr. J. 2003, 50, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Kuraganti, G.; Steenkamp, D. Hypercalcemic Crisis: A Clinical Review. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInerney, N.J.; Moran, T.; O’Duffy, F. Parathyroid Carcinoma: Current Management and Outcomes—A Systematic Review. Am. J. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Med. Surg. 2023, 44, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarty, N.; Mahajan, A.; Basu, S.; D’Cruz, A.K. Imaging Recommendations for Diagnosis and Management of Primary Parathyroid Pathologies: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranović Ovčariček, P.; Giovanella, L.; Carrió Gasset, I.; Hindié, E.; Huellner, M.W.; Luster, M.; Piccardo, A.; Weber, T.; Talbot, J.N.; Verburg, F.A. The EANM Practice Guidelines for Parathyroid Imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 2801–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.; Wang, T.S.; Farrokhyar, F.; Roman, S.A.; Sosa, J.A. A Meta-Analysis of Preoperative Localization Techniques for Patients with Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M.; Jikuzono, T.; Kure, S.; Ishibashi, O.; Akasu, H.; Sugitani, I. Usefulness of Ultrasonographic Detective Flow Imaging for Detecting Parathyroid Tumors: A Report of Two Cases. J. Nippon. Med. Sch. 2024, 90, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Lilla, E.; Miller, D.V.; Austin, K.; Hazel, M.; Ansari, I.; Sheppard, B.; Butler, A.M.; Aljammal, J. Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy of Parathyroid Adenomas in Patients Undergoing Parathyroidectomy Does Not Lead to Clinically Significant Fibrosis. Gland Surg. 2025, 14, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köroğlu, E.Y.; Evranos Öğmen, B.; Tural Balsak, B.; Yazicioğlu, M.Ö.; Aydin, C.; Topaloğlu, O.; Ersoy, R.; Çakir, B. Unlocking the Diagnostic Potential of Parathormone Washout: A Path to Accurate Parathyroid Tumor Localization. Postgrad. Med. 2025, 137, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbaloglu, H.; Deniz, O.; Ozaydin, R.Y.; Tasdoven, I.; Karadeniz Cakmak, G. Parathyroid Fine Needle Aspiration with PTH Washout: Can It Lead to Parathyroid Cell Seeding in Primary Hyperparathyroidism? Medicine 2024, 103, E37754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentsch, E.J.; Withrow, K.P.; Ackermann, D.; Bumpous, J.M. Parathyromatosis and Recurrent Hyperparathyroidism. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2003, 129, 894–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, C.; Bonadio, A.G.; Berti, P.; Materazzi, G.; Miccoli, P. Cutaneous Spreading of Parathyroid Carcinoma after Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2000, 23, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, G.; Dhingra, S.; Mishra, S.K.; Krishnani, N. Implantation of Parathyroid Carcinoma along Fine Needle Aspiration Track. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2006, 391, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Li, W.; Wen, B.; Xue, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Gong, J.; Huang, L.; He, J.; Yao, J.; et al. An Explainable Radiomics-Based Machine Learning Model for Preoperative Differentiation of Parathyroid Carcinoma and Atypical Tumors on Ultrasound: A Retrospective Diagnostic Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1617032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coakley, A.J.; Kettle, A.G.; Wells, C.P.; O’Doherty, M.J.; Collins, R.E. 99Tcm Sestamibi—A New Agent for Parathyroid Imaging. Nucl. Med. Commun. 1989, 10, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrakul, N.; Civelek, A.C.; Stagg, C.A.; Udelsman, R. In Vitro Accumulation of Technetium-99m-Sestamibi in Human Parathyroid Mitochondria. Surgery 2001, 130, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, A.; Jeannotte, S.; Verreault, J.; Lefebvre, B.; Bisson, G.; Mongeau, C.J.; Maheux, P. Preoperative Localization of Parathyroid Lesions in Hyperparathyroidism: Relationship between Technetium-99m-MIBI Uptake and Oxyphil Cell Content. J. Nucl. Med. 1998, 39, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, F.; Torregrosa, J.V.; Fuster, D. Biological Factors Influencing Parathyroid Localization. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2003, 24, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranović Ovčariček, P.; Calderoni, L.; Campenni, A.; Fanti, S.; Giovanella, L. Molecular Imaging of Thyroid and Parathyroid Diseases. Expert. Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 19, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, M.; Wieslander, B.; Myschetzky, P.S.; Lundstrøm, A.; Bacher, T.; Sørensen, C.H.; Trolle, W.; Nygaard, B.; Bennedbæk, F.N. A Prospective Comparative Study of Parathyroid Dual-Phase Scintigraphy, Dual-Isotope Subtraction Scintigraphy, 4D-CT, and Ultrasonography in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, G.; Mesguich, C.; Gaye, D.; Tabarin, A.; Haissaguerre, M.; Hindié, E. Dual-Tracer 99mTc-Sestamibi/ 123I Imaging in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 67, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périé, S.; Fessi, H.; Tassart, M.; Younsi, N.; Poli, I.; St Guily, J.L.; Talbot, J.-N. Usefulness of Combination of High-Resolution Ultrasonography and Dual-Phase Dual-Isotope Iodine 123/Technetium Tc 99m Sestamibi Scintigraphy for the Preoperative Localization of Hyperplastic Parathyroid Glands in Renal Hyperparathyroidism. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 45, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, A.-M.; Bolster, A.A.; Han, S.; Poon, F.-W.; Colville, D.; Shand, J.; Neilly, J.B. Dual-Isotope Subtraction SPECT-CT in Parathyroid Localization. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2017, 38, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukan, A.; Reyhan, M.; Aydin, M.; Yapar, A.F.; Sert, Y.; Canpolat, T.; Aktas, A. Preoperative Evaluation of Hyperparathyroidism: The Role of Dual-Phase Parathyroid Scintigraphy and Ultrasound Imaging. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2008, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.N.; Salahudeen, H.M.; Lansdown, M.; Scarsbrook, A.F. Clinical Utility of Ultrasound and 99mTc Sestamibi SPECT/CT for Preoperative Localization of Parathyroid Adenoma in Patients with Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Clin. Radiol. 2010, 65, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranović Ovčariček, P.; Giovanella, L.; Hindie, E.; Huellner, M.W.; Talbot, J.N.; Verburg, F.A. An Essential Practice Summary of the New EANM Guidelines for Parathyroid Imaging. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 66, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, L.; Rui, W.; Guo, R.; He, H.; Miao, Y.; Meng, H.; Liu, J.; Li, B. Semi-Quantitative Analysis of 99mTc-Sestamibi Retention Level for Preoperative Differential Diagnosis of Parathyroid Carcinoma. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2019, 9, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listewnik, M.H.; Piwowarska-Bilska, H.; Kurantowicz, M.; Ostrowski, M.; Borowiecki, A.; Safranow, K.; Jasiakiewicz, K.; Iwanowski, J.; Chosia, M.; Laszczyńska, M.; et al. Semi-Quantitative Method for the Assessment of Focal Lesions in Parathyroid Scintigraphy with Relation to Histopathology: A Prospective Study. Nucl. Med. Rev. Cent. East. Eur. 2017, 20, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; You, J.; Deng, S.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hong, Z. Diagnostic Value of Tc-99m-MIBI SPECT/CT in Parathyroid Carcinoma with Lung Metastasis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1501447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brument, M.; Zanetta, S.; Drouet, C. 18F-Fluorocholine PET/CT for the Staging and Follow-up of a Patient Suffering From Metastatic Parathyroid Carcinoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2025, 50, e617–e620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranović Ovčariček, P.; Schaab, J.; Beintner-Skawran, S.; Maurer, A.; Rupp, N.J.; Ikenberg, K.; Morand, G.B.; Mueller, S.A.; Vetter, D.; Liberini, V.; et al. [18F]Fluorocholine PET/MRI and [18F]Fluorocholine PET/CT as First- and Second-Line Imaging in Primary Hyperparathyroidism—Who Takes the Lead? Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2025, 52, 5165–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deandreis, D.; Terroir, M.; Al Ghuzlan, A.; Berdelou, A.; Lacroix, L.; Bidault, F.; Troalen, F.; Hartl, D.; Lumbroso, J.; Baudin, E.; et al. 18Fluorocholine PET/CT in Parathyroid Carcinoma: A New Tool for Disease Staging? Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 42, 1941–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radzikowski, K.C.; Rendl, G.; Beheshti, M.; Pirich, C. 18F Choline PET/CT in a Patient with HRPT2 Mutation: Detecting Parathyroid Carcinoma Recurrence and Concomitant Breast Carcinoma. Nuklearmedizin 2022, 61, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzl, M.; Röper-Kelmayr, J.C.; Fellner, F.A.; Gabriel, M. 18F-Fluorocholine, 18F-FDG, and 18F-Fluoroethyl Tyrosine PET/CT in Parathyroid Cancer. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 42, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morand, G.B.; Rupp, N.J.; Huellner, M.W.; Gerber, P.A.; Soyka, M.B.; Broglie, M.A.; Holzmann, D. Transnasal-Transpterygoid Endoscopic Removal of an 18F–Choline-Avid Parathyroid Carcinoma Metastasis in the Skull Base. JAMA Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 978–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovitti, C.M.; Cuzzocrea, M.; Gianola, L.; Paone, G.; Treglia, G. Dual-Tracer Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography with [18F]FDG and [18F]Fluorocholine in a Patient with Metastatic Parathyroid Carcinoma. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.W.; Ismail, A.; Søndergaard, S.B.; Bennedbæk, F.N.; Nygaard, B.; Jensen, L.T.; Trolle, W.; Holst-Hahn, C.; Zerahn, B.; Kristensen, B.; et al. Preoperative Imaging in Primary Hyperparathyroidism: Are 11C-Choline PET/CT and 99mTc-MIBI/123Iodide Subtraction SPECT/CT Interchangeable or Do They Supplement Each Other? Clin. Endocrinol. 2022, 97, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noltes, M.E.; Kruijff, S.; Jansen, L.; Westerlaan, H.E.; Zandee, W.T.; Dierckx, R.A.J.O.; Brouwers, A.H. A Retrospective Analysis of the Diagnostic Performance of 11C-Choline PET/CT for Detection of Hyperfunctioning Parathyroid Glands after Prior Negative or Discordant Imaging in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. EJNMMI Res. 2021, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noltes, M.E.; Kruijff, S.; Noordzij, W.; Telenga, E.D.; Vállez García, D.; Trofimiuk-Müldner, M.; Opalińska, M.; Hubalewska-Dydejczyk, A.; Luurtsema, G.; Dierckx, R.A.J.O.; et al. Optimization of Parathyroid 11C-Choline PET Protocol for Localization of Parathyroid Adenomas in Patients with Primary Hyperparathyroidism. EJNMMI Res. 2019, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noltes, M.E.; Coester, A.M.; van der Horst-Schrivers, A.N.A.; Dorgelo, B.; Jansen, L.; Noordzij, W.; Lemstra, C.; Brouwers, A.H.; Kruijff, S. Localization of Parathyroid Adenomas Using 11C-Methionine Pet after Prior Inconclusive Imaging. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2017, 402, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, D.; Boerner, A.R.; Hofmann, M.; Brunkhorst, T.; Meyer, G.J.; Petrich, T.; Scheumann, G.F.; Knapp, W.H. Pre-Operative Localisation of Hyperfunctional Parathyroid Tissue with 11C-Methionine PET. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2004, 31, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, T.; Gottstein, M.; Schwenzer, S.; Beer, A.; Luster, M. Is C-11 Methionine PET/CT Able to Localise Sestamibi-Negative Parathyroid Adenomas? World J. Surg. 2017, 41, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, N.; Nakamoto, Y.; Kurihara, K.; Yasoda, A.; Kanamoto, N.; Miura, M.; Inagaki, N.; Togashi, K. A Comparison between 11C-Methionine PET/CT and MIBI SPECT/CT for Localization of Parathyroid Adenomas/Hyperplasia. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2015, 36, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bioletto, F.; Barale, M.; Parasiliti-caprino, M.; Prencipe, N.; Berton, A.M.; Procopio, M.; Deandreis, D.; Ghigo, E. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of 18F-Fluorocholine PET and 11C-Methionine PET for parathyroid localization in primary hyperparathyroidism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 185, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.; Smaxwil, C.; Hermann, M.; Lenschow, C.; Lorenz, K.; Steinmüller, T.; Trupka, A.; Negele, T.; Holzer, K.; Tzatzarakis, E.; et al. Results of 18F-Choline and 11C-Methionine Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography for the Preoperative Localization of Hyperfunctional Parathyroid Glands in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 2025, 180, 109056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noltes, M.E.; Kruijff, S.; Appelman, A.P.A.; Jansen, L.; Zandee, W.T.; Links, T.P.; van Hemel, B.M.; Schouw, H.M.; Dierckx, R.A.J.O.; Francken, A.B.; et al. Head-to-Head Comparison of [11C]Methionine PET, [11C]Choline PET, and 4-Dimensional CT as Second-Line Scans for Detection of Parathyroid Adenomas in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 51, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranović Ovčariček, P.; Giovanella, L.; Vrachimis, A. Parathyroid Imaging. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 67, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omi, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Nagashima, Y.; Abe, K.; Karasawa, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Okamoto, T. Parathyroid Carcinoma in a 13-Year-Old Girl with a Long-Term Survival. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, C. PET-FDG: Impetus. Cancers 2020, 12, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.J.; Wienke, A.; Surov, A. Associations between GLUT Expression and SUV Values Derived from FDG-PET in Different Tumors-A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluijfhout, W.P.; Pasternak, J.D.; Drake, F.T.; Beninato, T.; Gosnell, J.E.; Shen, W.T.; Duh, Q.Y.; Allen, I.E.; Vriens, M.R.; de Keizer, B.; et al. Use of PET Tracers for Parathyroid Localization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2016, 401, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, L.; Sorgato, N.; Torresan, F.; Boschin, I.M.; Pennelli, G.; Saladini, G.; Piotto, A.; Rubello, D.; Pelizzo, M.R. FDG-PET/CT and Parathyroid Carcinoma: Review of Literature and Illustrative Case Series. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 2, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lu, H.; Gao, Y. FDG-Anorectic Parathyroid Carcinoma with FDG-Avid Bone Metastasis on PET/CT Images. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2013, 38, 916–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Jeon, Y.K.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, B.H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, I.J. Distant Subcutaneous Recurrence of a Parathyroid Carcinoma: Abnormal Uptakes in the 99mTc-Sestamibi Scan and 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, M.; Sia, W.; Hoskinson, M.; Niven, E.; Khurana, R. The Use of PET/CT in Pregnancy: A Case Report of Malignant Parathyroid Carcinoma and a Review of the Literature. Obstet. Med. 2018, 11, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantic, N.; Grujicic, L.; Radovic, B.; Saranovic, D.S.; Artiko, V.; Odalovic, S. The Complementary Roles of 18F-Fluorocholine and 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in an Evaluation of a Patient with Parathyroid Carcinoma: A Case Report. Mol. Imaging Radionucl. Ther. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemps, B.; Quarles Van Ufford, H.; Creyghton, W.; De Haas, M.; Baarslag, H.J.; Borel Rinkes, I.; De Klerk, J. Brown Tumors Simulating Metastases on FDG PET in a Patient with Parathyroid Carcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2008, 35, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.F.; Albrecht-Beste, E. Brown Tumors Due to Primary Hyperparathyroidism in a Patient with Parathyroid Carcinoma Mimicking Skeletal Metastases on (18)F-FDG PET/CT. Diagnostics 2015, 5, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, Y.; Sun, S.; Via, M.A. Brown Tumors Secondary to Parathyroid Carcinoma Masquerading as Skeletal Metastases on 18F-FDG PET/CT: A Case Report. AACE Clin. Case Rep. 2019, 5, e230–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A.; Inagi, T.; Iijima, H.; Ebisumoto, K.; Okami, K. Two Cases of Parathyroid Carcinoma Associated with Multiple Brown Tumours. BJR Case Rep. 2023, 10, uaad003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. Differential Diagnosis of Brown Tumors and Bone Metastases from Parathyroid Carcinoma Using 18F-FDG PET/CT and 99mTc-MIBI SPECT/CT: A Case Report. Asian J. Surg. 2025, 48, 1587–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwee, T.C.; de Klerk, J.M.H.; Nix, M.; Heggelman, B.G.F.; Dubois, S.V.; Adams, H.J.A. Benign Bone Conditions That May Be FDG-Avid and Mimic Malignancy. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 47, 322–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquet-Francillon, N.; Prevot, N. Brown Tumors in Nuclear Medicine: A Systematic Review. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2023, 37, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paramita, R.D.; Rahardjo, P. Multiple Brown Tumor in Late Adolescence Mimicking Bone Metastasis: A Challenging Case Report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2024, 19, 4266–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, M.; An, Q.; Wei, L.; Chen, B. Detection of Muscular Metastasis in a Case of Parathyroid Carcinoma Using 18 F-FAPI-04 PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2024, 49, e501–e502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorba, D.D.; Kuyumcu, S.; Uzum, A.K.; Isik, E.G.; Sanli, Y. Detection of Recurrent Parathyroid Cancer Using 68 Ga-Trivehexin PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2025, 50, e451–e452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.J.; Marangos, P.J.; Richardson, S.; LoGerfo, P.; Hardy, M.A.; Feind, C.; Reemtsma, K. Presence of Neuron-Specific Enolase and Somatostatin in Human Parathyroid Tissues. Surgery 1985, 98, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Storvall, S.; Leijon, H.; Ryhänen, E.; Louhimo, J.; Haglund, C.; Schalin-Jäntti, C.; Arola, J. Somatostatin Receptor Expression in Parathyroid Neoplasms. Endocr. Connect. 2019, 8, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawagishi, S.; Funaki, S.; Ose, N.; Kimura, K.; Mukai, K.; Otsuki, M.; Shintani, Y. Debulking Surgery for Functional Pleural Dissemination of Parathyroid Carcinoma-Case Report. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).