Abstract

Aerostatic bearings incorporating micro-hole restrictors with diameters on the order of tens of microns demonstrate superior static and dynamic stiffness characteristics, while significantly reducing air consumption, and are increasingly adopted in precision engineering applications. This paper investigates the modelling of aerostatic bearings with micro-hole restrictors. First, a refined discharge coefficient formula is developed, incorporating the orifice length-to-diameter ratio effect using the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation results on a centrally fed circular aerostatic bearing. A numerical solution scheme is proposed using the developed discharge coefficients to enable more accurate and efficient prediction of the bearing performance and flow characteristics. Finally, the proposed numerical approach is implemented using the finite difference method (FDM) and demonstrated through a circular thrust air bearing case study. The results are validated against both CFD simulations and experimental measurements, showing excellent agreement and confirming the reliability of the FDM-based numerical model. Numerical and experimental investigations consistently demonstrate that micro-hole-restricted air bearings can achieve both high load capacity and high stiffness, having the potential for application in more complex air bearing designs and systems.

1. Introduction

Aerostatic or air bearings are a class of gas-lubricated bearings that support loads using a thin film of externally pressurised air introduced through restrictors. Unlike aerodynamic bearings, which rely on relative motion to generate pressure, air bearings maintain a stable air film even at zero or low speeds, making them ideal for applications requiring high precision and minimal friction. Due to their non-contact operation, air bearings exhibit several advantages over conventional contact-based bearings, including negligible wear, low heat generation, and the ability to operate in cleanroom environments. These characteristics make them particularly attractive in high-precision and high-speed applications such as ultra-precision machining [1,2,3], coordinate measuring machines [4,5,6], semiconductor manufacturing equipment [7,8], and space and aerospace systems [9,10], where lubrication-free operation is critical.

Restriction, or compensation, is one of the most critical aspects in the design of air bearings, as it directly influences key performance parameters such as load-carrying capacity, stiffness, air consumption, and stability [11]. Various types of restriction methods have been developed to regulate the flow of pressurised air into the bearing gap. These include orifice restrictors (with or without pockets), capillary restrictors, slot restrictors, porous media restrictors, and micro-hole arrays. Among these, simple orifices with recessed pockets or grooves are widely used due to their ease of fabrication and ability to provide high load capacity and stiffness. However, they often suffer from dynamic instabilities such as air hammer effects and limited damping, which can degrade performance in high-speed or precision applications. In contrast, annular or inherent restrictors offer improved dynamic characteristics, including better damping and stability, but typically at the expense of lower load capacity and stiffness.

Micro-hole restrictors with diameters in the range of tens of microns have emerged as a highly promising restriction technology. The recent advancements in laser micromachining and mechanical micro-drilling have enabled the reliable fabrication of micro-holes, making this approach not only practical but increasingly preferred in high-performance applications. These micro-hole restrictors combine the simplicity of orifices with improved flow distribution and dynamic performance. With careful design, they can achieve higher load capacity due to the relatively large number of feeding holes, hence having a larger and uniform high-pressure region, and also higher static and dynamic stiffness at a smaller air film gap. Moreover, the smaller diameter of the restrictors and air film gap reduce air consumption, a factor which is usually ignored but critical in modern precision systems as the compressed air is one of the most expensive utilities.

Schulz and Muth presented air bearings fabricated with laser-drilled micro-hole restrictors. They reported that air bearings with a large number of micro-orifices without pockets or groove, particularly with a large orifice length-to-diameter ratio, achieve optimal static and dynamic performance [12,13]. Refs. [14,15] investigated the annular thrust bearings with micro-feed holes of less than 50 µm diameter. They numerically and experimentally confirmed that air bearings with micro-feed holes have a larger stiffness and a higher damping coefficient than bearings with conventional restrictors. Lu et al. reported on the performance of air bearings with a multi-hole integrated restrictor, with a diameter as small as 50 µm, which is like a porous insert. The results showed that the number of micro-holes in the integrated restrictor had a significant effect on the bearing performance [16]. Belforte et al. performed experimental analysis of air bearings with laser-drilled micro-holes in the range of 50–100 µm, providing a guidance on maximising stiffness and minimising air consumption [17]. For practical air bearing design using micro-hole restrictions, Wu et al. investigated the flow behaviour of a circular thrust air bearings with micro-holes and the effect of micro-hole diameter, number of holes, and the layout of the holes on the load capacity and stiffness [18]. Wang et al. proposed a multi-objective design approach to optimise the micro-hole air bearing performance [19].

Despite the growing interest in air bearings with micro-hole restrictors, there is no accurate and computationally efficient model that can capture flow characteristics and calculate the static and dynamic performance for practical air bearing designs. For conventional orifices, the mass flow rate is typically calculated using lumped-parameter equations under the assumption of isentropic conditions. These assumptions are valid primarily for orifices with relatively large diameters and short lengths, where the length-to-diameter ratio (L/do) is close to one.

However, micro-hole restrictors with diameters on the order of tens of microns often have L/do ratios exceeding 10 due to structural design constraints. Such high aspect ratios significantly alter the internal flow regime within the restrictor. Unlike larger orifices with low L/do ratios, where air velocity builds up rapidly, potentially leading to turbulence and self-excited vibrations, the combination of small orifice diameter and high aspect ratio promote laminar and more isothermal flow due to lower velocity gradients and reduced temperature rise. These flow characteristics can have a profound impact on the load capacity, stability, damping, and thermal behaviour of the bearing, yet they are not well-understood or quantified in the current literature.

Accurate determination of the discharge coefficient for micro-hole restrictors is critical for predicting air bearing performance using numerical methods such as the finite difference method (FDM). Previous studies have attempted to determine discharge coefficients for micro-holes through the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) approach [14,20] and experimental measurements [21]. However, reported values of discharge coefficients vary widely, and the existing models often neglect the influence of the length-to-diameter ratio.

This study aims to address these gaps by investigating the flow behaviour through the micro-hole restrictors with varying length-to-diameter ratio. The objectives are (1) to obtain accurate discharge coefficients that account for the influence of L/do ratio and air film thickness, and (2) to develop a practical numerical solution scheme suitable for practical bearing designs. To achieve this, both CFD simulations and experimental measurements will be conducted to validate the numerical simulation results.

2. Governing Equations

2.1. Flow Characteristics of Micro-Hole Restrictors

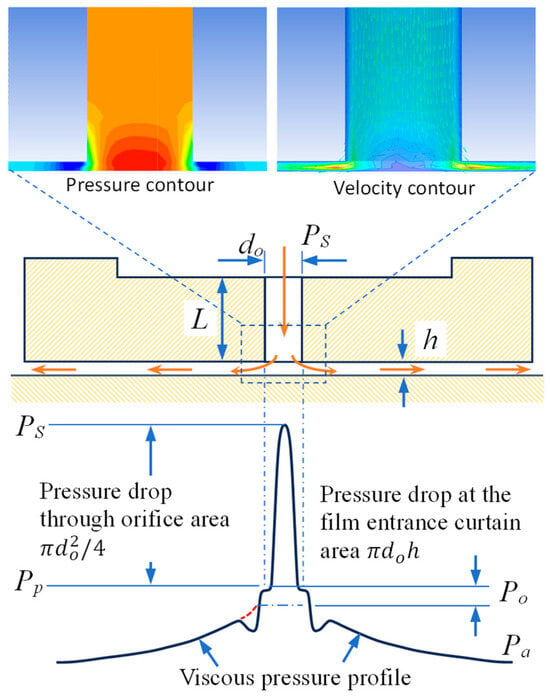

Firstly, the flow characteristics of micro-hole restrictors is investigated. CFD has been used to accurately predict bearing performance and capture flow behaviour [14,15,18,19]. To qualitatively investigate flow characteristics, a simple centrally fed micro-hole restrictor circular air bearing model was developed. Figure 1 presents typical pressure and velocity contours along a cross-sectional plane through the bearing diameter. Further parametric analyses using the same CFD model to determine the discharge coefficient are discussed in Section 3.

Figure 1.

Pressure profile in an orifice-compensated air bearing.

In orifice-compensated air bearings, compressed air flows to the bearing film through two restricted areas acting in series: the orifice area A1 = , and the film entrance annular curtain area A2 = . Here do denotes the orifice diameter, and h the bearing film thickness, which is typically designed around 10 µm to maximise stiffness. In conventional orifices, with do around 200 µm, the orifice area, A1, is significantly greater than the annular curtain area, A2, such that the mass flow rate is predominantly restricted by A2, i.e., inherently compensated restriction. By contrast, when micro-holes with a diameter of around 50 µm are used, A1 becomes comparable to A2, and the mass flow rate is jointly restricted by both areas. This dual restriction mechanism is the key characteristic of micro-hole-restricted air bearings and underpins their performance to achieve higher load capacity and stiffness. Accordingly, accurate modelling of micro-hole-restricted bearings requires explicit consideration of both restrictors.

As shown in Figure 1, the supply pressure Ps firstly drops to orifice downstream pressure Pp before reaching annular curtain area at the film entrance. It then further drops to Po which is the theoretical pressure at the film entrance. Po is the pressure required to balance air mass flow rate and serves as the boundary condition to calculate pressure distribution across the bearing film.

2.2. Micro-Hole Restrictor Modelling

Accurate modelling of micro-hole restrictors is essential for understanding and designing air bearings. Analytical flow models, derived from the Navier–Stokes equations under specific assumptions, not only provide effective predictive capabilities but also valuable physical insight into the design process. Two possible analytical flow models are the isothermal compressive flow model and isentropic orifice model. The isothermal compressive flow equation is applicable to laminar flow in capillaries with a length-to-diameter ratio greater than 20, though it neglects the inertia effect. The isothermal compressive flow equation is applicable to laminar flow in capillaries with a length-to-diameter ratio greater than 20, though it neglects the inertia effect. On the other hand, the isothermal compressive flow equation applies to the established flow; at the exit of the micro-hole restrictor, the flow impinges on the bearing surface and subsequently turns into the air film. This process introduces substantial irreversible pressure losses (as shown in Figure 1), which are not explicitly represented in the capillary flow model. In contrast, the isentropic flow describes an idealised one-dimensional, compressible, and adiabatic flow in which frictional and viscous effects are neglected. To account for these effects, an empirical discharge coefficient is typically introduced to correct the predicted mass flow rate and account for real flow losses. An empirical isentropic orifice model is used in this research.

The mass flow rate through the orifice restrictor is [22]

where κ is the ratio of specific heats for air κ = 1.4. R and T are the gas constant and the absolute temperature, respectively. The discharge coefficient of the orifice Cd is an empirical factor which is used to correct the difference between actual mass flow ratio to the theoretical mass flow rate in isentropic condition. The discharge coefficient Cd can account for pressure drop effect, viscous losses, and non-ideal orifice geometry, etc.

Chocked flow occurs at the limiting pressure ratio [22].

Then, at choked flow condition, mass flow rate through the orifice restrictor is calculated.

The mass flow rate through the annular curtain area takes the same form:

In Equation (4), pure inviscid isentropic flow is assumed, as the annular curtain area represents only a short entrance region; therefore, a discharge coefficient is not applied. Po and Pp are defined in Figure 1. There is no analytical solution to Po and Pp, so numerical methods must be used to calculate the pressure drops across the restrictors.

2.3. Air Bearing Film Modelling

- The following assumptions are made in modelling air bearing film:

- (a)

- Inertia forces, due to acceleration, can be neglected compared to forces produced by viscous shear.

- (b)

- Laminar flow conditions exist at all points in the air film.

- (c)

- Pressure is constant over any section normal to the direction of flow. For thin film flow, film height is significantly smaller than film length, so the difference in pressure in film height is neglected.

- (d)

- The boundaries are solid and impervious.

- (e)

- There is no slip in the boundaries between the fluid and the surfaces, i.e., the fluid and surface have the same velocity at the interface.

- (f)

- The lubricant behaves like a Newtonian fluid. Shear stress is linearly proportional with the velocity derivative scaled with viscosity.

- (g)

- The air film is assumed to be isothermal.

Based on the assumptions above, the pressure distribution in the air bearing film is governed by compressible isothermal Reynolds equation. Its general form in the Cartesian coordinates (x, y) is expressed as follows:

where

- p—pressure;

- h—film thickness;

- μ—dynamic viscosity of air;

- ρ—air density (function of pressure under isothermal conditions);

- U, V—relative surface velocities in the x- and y-directions;

- ∂h/∂t—squeeze film effects representing the time rate of change in film thickness.

When the air film gap h is constant and relative surface velocities are low, the terms on the right-hand side of the equation may be neglected. Equation (5) can then be simplified as

The air density under isothermal condition reads

By replacing ρ with p, Equation (6) can be further simplified as

Let P = p2, the above becomes the Laplace equation.

The numerical model developed is applied to a circular thrust air bearing pad. It is convenient to work in the polar coordinates (r, θ). Equation (8) is transformed to polar coordinates:

Similarly, Equation (9) is linearised by letting P = p2.

A five-point central finite difference method is used to solve Equation (11), where the finite difference forms are as follows:

By substituting Equation (12) into Equation (11), the finite difference equation is obtained:

where

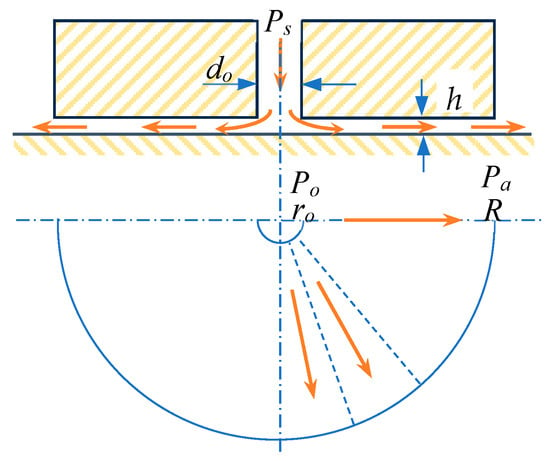

For a circular centrally fed bearing with only one feeding hole (as shown in Figure 2), which will be solved using CFD in the next section, it is the case of radial flow with uniform film thickness, and the mass flow rate through the film is written as follows:

where

Figure 2.

Circular centrally fed air bearing.

- Po—pressure at radius ro (entrance of the air film);

- Pa—ambient pressure;

- R—circular bearing radius;

- ro—orifice radius.

Equation (14) gives the relation between pressure at the film entrance Po and the mass flowrate. Equation (14) is rearranged to obtain the expression of Po as the function of mass flow rate.

Although Po can be calculated analytically from the load, a more accurate and noniterative approach is to determine Po using the mass flow rate (i.e., Equation (15)) for a circular centrally fed bearing.

2.4. Air Bearing Performance Calculations

The load capacity W over the bearing surface is given as

where p(r) is the pressure at radius r. And the stiffness is given by

In the design and optimisation of air bearing performance, both stiffness and load capacity are typically normalised by a characteristic pressure and area. This normalisation allows direct comparison across bearings with different diameters, film thicknesses, and supply pressures. The dimensionless load capacity and stiffness are defined as follows:

where A is the bearing area and ho is the bearing design film thickness.

3. Discharge Coefficient Determination and Numerical Solution Scheme

3.1. Discharge Coefficient Determination

CFD simulations were performed using the commercial software ANSYS Fluent 2024R2 to determine the discharge coefficients and predict flow characteristics. The three-dimensional simulation model includes a circular air bearing pad with a single centrally fed orifice, as illustrated in Figure 2. Ideal gas, isothermal conditions, laminar flow, and no-slip boundary condition on the wall were assumed in the simulation model. An iterative convergence accuracy of ε = 10−6 was applied to ensure numerical accuracy. The boundary conditions were the pressure at the inlet and outlet. Table 1 summarises the design parameters and operating conditions.

Table 1.

Design parameters and operating conditions of the simulation.

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the dimensionless load capacity and flowrate of the circular centrally fed air bearing at various L/do ratio, respectively. As shown in the inset of Figure 3, at a film thickness of 8 µm, which falls within the usual working range of 5–15 µm, the dimensionless load capacity decreases from 0.07 to 0.062 as the L/do ratio increases from 2 to 18. A similar trend is observed for the flowrate as shown in Figure 4. As the L/do ratio increases from 2 to 18, the flowrate decreases significantly, particularly when the film thickness exceeds 10 µm. The significant influence of the L/do ratio on the bearing performance confirms that the L/do must be considered when determining the discharge coefficient.

Figure 3.

Load capacity of the centrally fed air bearing.

Figure 4.

Flowrate of the centrally fed air bearing pad.

It should be noted that centrally fed air bearing is not an optimal configuration and therefore has a relatively low load capacity; it is only used here for determining the discharge coefficient as its mass flow rate can be expressed analytically.

The solution scheme to determine the discharge coefficient is proposed as follows:

- (1)

- Perform CFD simulations on a simple geometry, e.g., circular centrally fed air bearing pad, to obtain mass flow rate and load W at different film thickness h, orifice diameter do, and orifice length-to-diameter ratio L/do.

- (2)

- Calculate film curtain entry pressure Po from mass flow rate using Equation (15) for radial flow. Although Po can also be calculated from load W, this approach would be less accurate and requires iterations. Po is the pressure used in the isothermal Reynolds equation to obtain pressure distribution in practical bearing designs using numerical methods such as FDM or FEM.

- (3)

- Calculate the downstream pressure Pp by solving Equation (4), i.e., mass flow equation for flow through the annular curtain area.

- (4)

- Determine the discharge coefficient Cd by solving Equations (1)–(3) at different do, h(Pp/Ps) and L/do.

- (5)

- Determine Cd as a function of do, h (Pp /Ps) and L/do.

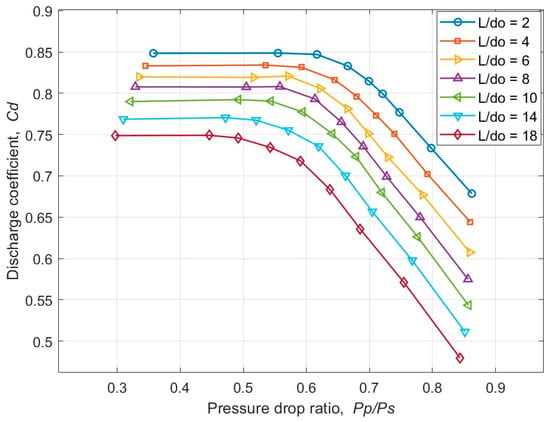

Figure 5 shows the calculated discharge coefficient for the air bearing pad at various L/do and h(Pp/Ps) ratios, with an orifice diameter of 50 μm, using the proposed discharge coefficient solution scheme. As illustrated, the discharge coefficient varies with air film thickness h, or more directly, with the pressure drop ratio Pp/Ps. At large pressure drop ratios, corresponding to a small bearing air film thickness, the discharge coefficient decreases approximately linearly with Pp/Ps. When pressure drop ratio falls below 0.5–0.6, corresponding to larger air film thicknesses, the discharge coefficient remains constant due to the onset of choked isentropic flow conditions.

Figure 5.

Calculated discharge coefficients at various L/do ratio and h(Pp/Ps).

The influence of orifice length-to-diameter ratio (L/do) is also evident for the small orifice diameter considered in the CFD simulation. As L/do increases, the discharge coefficient decreases as a result of increasing viscous losses. Consequently, both the mass flow rate (see Figure 4) and the load capacity (see Figure 3) are reduced, even though the upstream pressure remains constant. At large L/do, the micro-hole restrictor behaves increasingly like a capillary, where the viscous friction dominates the flow characteristics.

The following formula is proposed from the CFD results above by using linear approximation.

Cd0 is related to the orifice diameter and was determined in the CFD as 0.865 for the diameter used.

3.2. Bearing Design Numerical Solution Scheme

Once the discharge coefficient Cd is determined, numerical methods such as FDM or FEM can be used to calculate the load capacity, stiffness, and mass flow rate in a practical air bearing design. The overall solution scheme entails the following:

- (1)

- Specify the air bearing geometry, generate mesh, and define position of the orifices.

- (2)

- Guess the pressure Po thus enabling the pressure boundary condition at the inlet to the air film.

- (3)

- Solve Reynolds equation numerically to obtain the pressure distribution within the film (finite difference equations, Equation (13), are given in polar coordinates) and mass flow rate through the bearing film.

- (4)

- Calculate the pressure drop Pp by solving Equation (4).

- (5)

- Determine mass flow rate through the orifice using Equation (1) or Equation (3) using the corresponding discharge coefficient Cd (Equation (20)).

- (6)

- Repeat steps (2)–(5), until the difference between two mass flow rates, and , falls within the specified tolerance.

- (7)

- Repeat steps (2)–(6) for a predefined range of bearing air film thicknesses.

- (8)

- Calculate the load capacity, stiffness, and flow rate against air film thickness for the bearing.

4. Characteristics of a Circular Thrust Air Bearing with Micro-Hole Restrictors

To evaluate the accuracy of the proposed numerical solution scheme and the discharge coefficient derived from the centrally fed air bearing, a circular thrust air bearing incorporating micro-hole restrictors was selected as a case study. The performance of this thrust air bearing was analysed using the developed numerical approach, which was implemented with the finite difference method, and subsequently validated through both CFD simulations and experimental testing.

4.1. Numerical Models

The thrust bearing considered in this case study has multiple feed holes arranged in a concentric row along a specified pitch circle diameter, Dp. Figure 6 illustrates the bearing geometry and mesh configuration for the CFD model. The numerical approach described in Section 3 is implemented using the finite difference method, programmed in MATLAB R2024a.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the circular thrust air bearing and the mesh for CFD.

CFD simulations are conducted using the commercial software ANSYS Fluent. The CFD model assumes ideal gas behaviour under isothermal conditions, with laminar flow and no-slip boundary conditions at the walls. Table 2 lists the bearing and operational parameters. Given its axisymmetry about the centre, the simulation domain is reduced to a sector to increase the computational speed (see Figure 6).

Table 2.

Design parameters and operating conditions used in the thrust air bearing pads.

4.2. Experimental Setup

The performance of the thrust air bearing pads is measured experimentally on a dedicated test rig, as shown in Figure 7. The test rig is built using two support beams (4) and a cross beam (2), forming a stable structural frame. The bearing pad (8) is supplied with pressurised air and floats on a precision lapped granite surface. A lead screw (3), driven by a motor (1), is used to apply a controlled load to the bearing pad. To minimise parasitic displacement and ensure accurate loading, a set of linear guides (5) is installed between the screw and the bearing pad. The applied load, displacement, and air flow rate are measured using a load cell (7), a precision displacement sensor (9), and a digital flowmeter (6), respectively.

Figure 7.

Air bearing test rig.

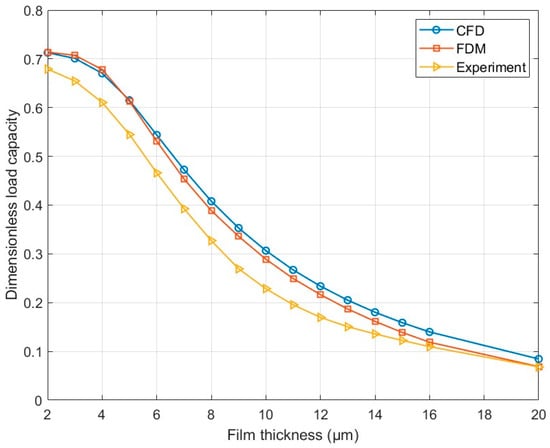

4.3. Results and Discussion

Figure 8 shows the dimensionless load capacity at various orifice lengths. As expected, the dimensionless load capacity can reach values as high as 0.7, which is significantly greater than that of circular centrally fed air bearings. Consistent with the results from the circular centrally fed air bearing simulations, the load capacity is influenced by the orifice length. As shown in the inset of Figure 8, at the film thickness of 8 µm, the load capacity decreases from 0.42 to 0.4 as the orifice length increases from 0.2 mm (L/do = 4) to 0.6 mm (L/do = 12), representing a change of approximately 5%. This further confirms that the effect of the orifice length cannot be ignored when calculating the bearing performance for the micro-hole-restricted bearings.

Figure 8.

Dimensionless load capacity of circular thrust bearing at different orifice lengths.

Figure 9 compares the dimensionless load capacity obtained from CFD, FDM, and experimental testing. FDM results show excellent agreement with CFD predictions, validating both the discharge coefficient obtained from the centrally fed air bearing simulation, and also the robustness of the proposed numerical solution scheme. A slight discrepancy is observed between experimental measurements and numerical simulations, with the experimental load capacity being lower. This difference is likely attributable to manufacturing errors, imperfections in the fabricated bearings, and numerical errors in the CFD model. Nevertheless, the stiffness measured experimentally aligns closely with simulation results, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Dimensionless load capacity of circular thrust bearings obtained from CFD, FDM, and experiments.

Figure 10.

Dimensionless stiffness of circular thrust bearings obtained from CFD, FDM, and experiments.

The maximum dimensionless stiffness is achieved at a film thickness of approximately 7 µm, as confirmed by both experimental and numerical approaches. The peak stiffness value of 0.6 is considered to be close to the optimal design, demonstrating that micro-hole-restricted air bearings are capable of simultaneously achieving high load capacity and high stiffness. This advantage highlights the potential of micro-hole restrictors in advancing the performance envelope of air bearing technology.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a discharge coefficient formula is developed for micro-hole restrictors, incorporating the effect of the orifice length-to-diameter (L/do) ratio effect. In addition, a numerical solution scheme is proposed for the analysis of micro-hole-restricted air bearings. The FDM simulations are validated by both CFD and experimental measurement. The following conclusions can be drawn.

- CFD simulations confirm that, for micro-hole-restricted air bearings, the orifice length-to-diameter ratio influences the flow behaviour through the restrictors, and consequently, the bearing performance in terms of load, stiffness, and mass flow rate.

- An accurate discharge coefficient formula accounting for both orifice length-to-diameter ratio and film thickness was derived from a centrally fed air bearing, and was verified to be accurate in a thrust circular bearing with multiple feed holes arranged in a pitch circle diameter.

- It was numerically and experimentally demonstrated that micro-hole-restricted air bearings can achieve high load capacity and high stiffness, having the potential for application in more complex air bearing designs and systems.

Author Contributions

D.H.: project administration, investigation, original draft. A.F.: modelling, formal analysis, review and editing. J.L. and N.G.: experiments and validation. K.C.: formal analysis, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Junliang Liu and Ning Gou are employed by Infina Precision Ltd.. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Gong, Z.; Huo, D.; Niu, Z.; Chen, W.; Cheng, K. A novel long-stroke fast tool servo system with counterbalance and its application to the ultra-precision machining of microstructured surfaces. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 173, 109063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, N.; Cheng, K.; Huo, D. Multiscale modelling and analysis for design and development of a high-precision aerostatic bearing slideway and its digital twin. Machines 2021, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huo, D.; Lu, L.; Liu, H. Design philosophy of an ultra-precision fly cutting machine tool for KDP crystal machining and its implementation on the structure design. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 70, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijschuur, R.H.T.; Saikumar, N.; HosseinNia, S.H.; van Ostayen, R.A.J. Air-based contactless wafer precision positioning system: Contactless sensing using charge coupled devices. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2022, 237, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, P. Accuracy improvement of the H-drive air-levitating wafer inspection stage based on error analysis and compensation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2018, 29, 045013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Park, C.H.; Kim, S.W. Estimation method for errors of an aerostatic planar XY stage based on measured profile errors. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2010, 46, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Chen, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Gao, W.; Takahashi, K.; Kanayama, T.; Arakawa, K.; Hayashi, A. A micro-coordinate measurement machine (CMM) for large-scale dimensional measurement of micro-slits. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, E.; Moers, T.; van Riel, M. Design and verification of an ultra-precision 3D-coordinate measuring machine with parallel drives. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2015, 26, 085904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, V.J.; Steyn, W.H.; Underwood, C.I. Attitude control for small satellites using control moment gyros. Acta Astronaut. 2002, 51, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, R.; Koç, M.A.; Ermiş, K. Hybrid ANFIS-PSO algorithm for estimation of the characteristics of porous vacuum preloaded air bearings and comparison performance of the intelligent algorithm with the ANN. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Chen, W.; Lu, L.; Huo, D.; Cheng, K. Aerostatic bearings design and analysis with the application to precision engineering: State-of-the-art and future perspectives. Tribol. Int. 2019, 135, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B.; Muth, M. Dynamically optimized air bearings manufactured with the laser beam. In Proceedings of the Lasers and Optics in Manufacturing III, Munich, Germany, 16–20 June 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, M.; Schulz, B. Segmented air bearing in micronozzle technology for the project SOFIA. In Proceedings of the Optical Science, Engineering and Instrumentation ’97, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 July–1 August 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyatake, M.; Yoshimoto, S. Numerical investigation of static and dynamic characteristics of aerostatic thrust bearings with small feed holes. Tribol. Int. 2010, 43, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, U.; Somaya, K.; Yoshimoto, S. Numerical calculation and experimental verification of static and dynamic characteristics of aerostatic thrust bearings with small feedholes. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 1790–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.-W.; Zhang, J.-A.; Liu, B. Research and analysis of the static characteristics of aerostatic bearings with a multihole integrated restrictor. Shock Vib. 2020, 2020, 7426928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belforte, G.; Colombo, F.; Raparelli, T.; Trivella, A.; Viktorov, V. Experimental analysis of air pads with micro holes. Tribol. Trans. 2013, 56, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Du, J. Lubrication mechanism and characteristics of aerostatic bearing with close-spaced micro holes. Tribol. Int. 2024, 192, 109278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Feng, K. A novel optimization design method for obtaining high-performance micro-hole aerostatic bearings with experimental validation. Tribol. Int. 2023, 185, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Chan, C.W.; Jeng, Y.R. Discharge coefficients in aerostatic bearings with inherent orifice-type restrictors. ASME J. Tribol. 2015, 137, 011705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beforte, G.; Raparelli, T.; Viktorov, V.; Trivella, A. Discharge coefficients of orifice-type restrictor for aerostatic bearings. Tribol. Int. 2007, 40, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, E.G.; Stout, K.J. Orifice restrictor losses in journal bearings. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 1979, 193, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.