Abstract

This paper presents a systematic review of linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension, a key technology for reconciling vehicle comfort, handling stability, and energy consumption. The review focuses on two core areas: actuator configuration and control strategy. In configuration design, a comparison of moving-coil, permanent magnet synchronous (PMSLM), and switched-reluctance linear motors identifies the PMSLM as the mainstream approach due to its high-power density and performance. Key design challenges for meeting stringent vehicle operating conditions, such as mass-volume optimization, thermal management, and high reliability, are also analyzed. Regarding control strategy, the review outlines the evolutionary path from classical to advanced and intelligent control. It also examines the energy-efficiency trade-off between vibration suppression and energy recovery. Furthermore, the paper summarizes three core challenges for industrialization: nonlinear issues like thrust fluctuation and friction, the coupling of electromagnetic–mechanical–thermal multi-physical fields, and bottlenecks related to high costs and reliability verification. Finally, future research directions are envisioned, including new materials, sensorless control, and active safety integration for autonomous driving.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

The chassis, serving as the fundamental load-bearing platform, plays a pivotal role in various domains such as automotive engineering [1,2,3,4,5] and agricultural machinery [6,7,8,9,10]. It provides structural support and connectivity for the powertrain system, transmission system, vehicle body or working implements, and payload. In addition to these functions, it facilitates the transmission of driving and braking forces while enduring complex impacts from road surfaces and operational activities. Nonetheless, a significant challenge facing chassis design is achieving a balance between the robustness necessary for load-bearing capabilities and the adaptability required to navigate uneven terrain. If the wheels were rigidly affixed to the chassis, road surface irregularities would generate severe impacts, leading to passenger discomfort, damage to cargo (especially any precision equipment being transported), loss of wheel grip, and premature fatigue failure of the chassis structure.

The suspension system serves as the fundamental solution to this conflict and plays a pivotal role in enhancing chassis performance. Employing elastic components (e.g., springs) and dampers, the suspension fulfills three essential functions: shock absorption and vibration damping, ensuring continuous wheel-to-ground contact, and stabilizing the vehicle’s body posture [11,12]. Consequently, the suspension acts as both an intelligent execution unit and a dynamic stabilizer of the chassis, striking a balance between stiffness and compliance. Its effectiveness directly influences the vehicle’s ability to efficiently, smoothly, and safely convert power into controllable motion under complex conditions. This capability significantly affects overall handling, comfort, safety, and operational efficiency. Thus, it constitutes the core subsystem that enables the chassis to achieve its full potential [13,14].

1.2. Development Needs of Suspension Systems

The design and optimization of suspension systems have consistently centered around three fundamental objectives: ride comfort, handling stability, and driving safety [15]. These performance requirements are the primary catalysts for technological advancements in suspension systems, necessitating ongoing enhancements in their design philosophies and control strategies.

Ride Comfort [16,17] pertains to a vehicle’s capacity to isolate and attenuate vibrations and shocks induced by road irregularities during travel, thereby creating a smooth and comfortable environment for occupants.

Handling Stability [18,19,20] encompasses the vehicle’s response—both transient and steady-state—to driver inputs such as steering, acceleration, and braking. Additionally, it involves the vehicle’s ability to withstand external disturbances like crosswinds or road banking while maintaining a stable driving posture. Effective handling stability demands that the suspension system proficiently suppresses variations in the vehicle’s body attitude while ensuring optimal tire adhesion [21].

Driving Safety [22,23] is paramount in vehicle design considerations. The role of the suspension system in enhancing safety has evolved from merely addressing passive safety concerns (ensuring structural integrity) to encompassing active safety measures. During emergency maneuvers—such as abrupt obstacle avoidance, high-speed cornering, or braking on slippery surfaces—the performance of the suspension system becomes critically linked to the vehicle’s capability to maintain control.

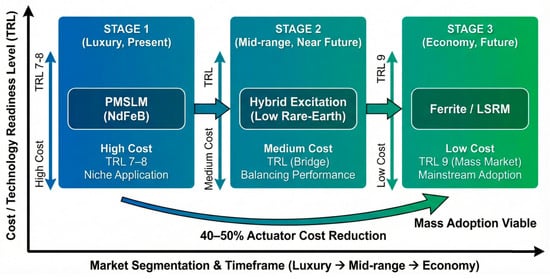

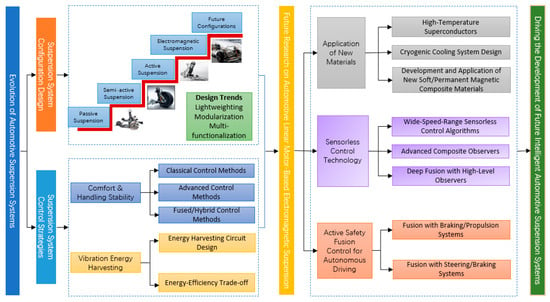

1.3. Development Trends of Vehicle Suspension Configurations

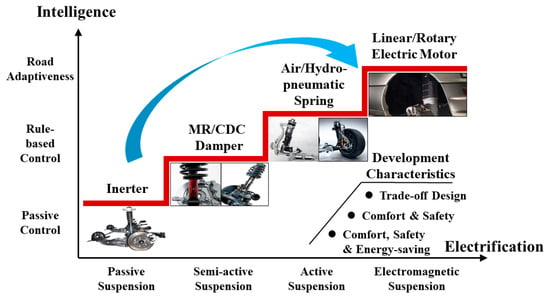

The conceptual framework for this evolution is depicted in Figure 1. The development of automotive suspension systems has followed a defined sequence, evolving through passive, semi-active, and active configurations, with electromagnetic suspension representing the current frontier. This progression corresponds to a sequential enhancement in control capability: from fixed passive mechanisms, to rule-based semi-active adjustments, to adaptive active control utilizing real-time road inputs, and more recently, to intelligent control strategies that incorporate predictive information and high-level decision-making. It is now heading towards intelligent control that incorporates predictive analytics and high-level decision-making processes. This technological maturation has been propelled by innovations in critical hardware components such as variable dampers (for instance, Magnetorheological (MR) and Continuous Damping Control (CDC) systems), alongside active elements like air springs. The culmination of these advancements is evident in the deployment of electromagnetic actuators characterized by their high dynamic response rates. The development trends within automotive suspension demonstrate clear trajectories toward intellectualization and electrification. This technological pathway directly addresses the core challenge of the comfort-handling trade-off in conventional suspension design. The aim is to collectively enhance performance across multiple domains—ride comfort, handling stability, and energy efficiency—to satisfy the stringent and integrated requirements of future intelligent electric vehicle platforms.

Figure 1.

Technology evolution roadmap of automotive suspension.

In passive suspensions, employing low damping is advantageous for mitigating body resonance and enhancing comfort. However, this approach results in suboptimal control of wheel hop and diminished tire grip. Conversely, utilizing high damping effectively suppresses wheel hop to ensure handling performance but also transmits more high-frequency vibrations to the vehicle chassis, thereby compromising comfort. As a result, the parameters selected for a passive suspension represent a compromise directed toward achieving specific evaluation metrics, making it unattainable to realize optimal performance across all operating conditions. In recent years, advancements in electrohydraulic and active air suspensions have made notable strides by enabling active control of ride height and suspension forces through sophisticated control algorithms. This development effectively enhances vehicle performance [24,25]. Nevertheless, these active suspension systems still face challenges such as structural complexity, elevated costs, significant energy consumption, limited response speed and control bandwidth, along with an increase in unsprung mass [26,27].

Precisely due to the irreconcilable conflicts inherent in traditional passive suspensions and the considerable application hurdles faced by existing mainstream active suspensions concerning cost-efficiency, energy demands, and responsiveness, novel suspension technologies exhibiting strong potential have garnered extensive attention. Among these, the linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension is prominent. Its straightforward architecture, rapid response, precise control, and energy regeneration capabilities position it as a key solution to the aforementioned challenges and a fundamental driver for the development of next-generation chassis systems.

1.4. Scope and Structure of This Review

The preceding sections have detailed the research background, developmental needs, and technological advantages of vehicle suspensions, as well as the application challenges of mainstream active suspension systems. Given these advantages, linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension has emerged as a critical development direction for next-generation high-performance suspensions. Therefore, to thoroughly elucidate the current research status and developmental trajectory of this technology, this review will subsequently focus on two core areas: (1) the configuration design of linear electromagnetic actuators, and (2) control methodologies. The former constitutes the physical embodiment and hardware foundation for achieving superior mechanical output, while the latter provides the theoretical underpinnings and control strategies essential for realizing intended performance objectives and multi-objective optimization.

2. Research on Configurations of Linear Motor-Based Electromagnetic Suspension

2.1. Motor Types and Topologies

As the essential actuation component of a linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension system, the design configuration and type selection of the electromagnetic actuator serve as foundational elements that determine the overall performance of the system [28]. Various motor types and topologies exhibit considerable differences in thrust density, dynamic response, control complexity, energy conversion efficiency, and manufacturing costs. Consequently, research focusing on their configuration design is fundamental within this domain.

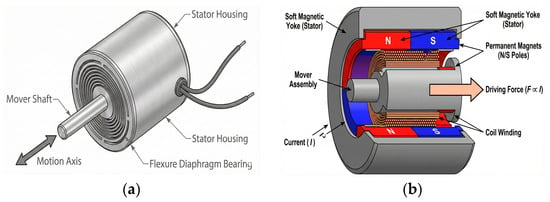

2.1.1. Moving-Coil Linear Motor (Voice Coil Actuator, VCA)

The moving-coil linear motor, commonly referred to as the Voice Coil Actuator (VCA), features a simple yet effective structure comprising a permanent magnet field assembly paired with coil windings, as shown in Figure 2. By applying an electric current through the coil, a driving force proportional to the current’s magnitude is generated within the magnetic field. Initially employed extensively in applications such as audio loudspeakers and magnetic head positioning for hard disk drives, VCAs are favored for several advantages including high acceleration capabilities, rapid response times, hysteresis-free operation, straightforward construction, smooth thrust output characteristics, and ease of achieving precise linear control. These benefits have led scholars to investigate their potential applications in high-performance control fields such as active suspension systems.

Figure 2.

Structure of a moving-coil linear motor: (a) three-dimensional schematic of the actuator assembly; (b) cross-sectional view illustrating the arrangement of permanent magnets and coil windings.

Focusing on the application of Voice Coil Actuators (VCAs) in precision motion control, Okyay et al. [29] proposed a comprehensive design and optimization methodology for cylindrical VCAs. They employed Finite Element Analysis to carry out parameter optimization with the dual objectives of maximizing acceleration and minimizing thermal dissipation. By decoupling the selection of coil specifications from performance optimization, they established a theoretical foundation for designing high-dynamic-performance VCAs, thus achieving performance enhancement at the structural level. Feng et al. [30] conducted a comparative analysis of two typical Voice Coil Motor (VCM) configurations and clearly elucidated their derivative relationship, providing an intuitive conceptual model for understanding the interconnections among various VCM structures. Luo et al. [31] innovatively integrated a VCA into an active suspension system. In their test rig, they connected the mover of the moving-coil motor to the wheel while linking the stator to the vehicle body. A parallel coil spring was incorporated to jointly support the load applied by the vehicle body, resulting in a complete quarter-car physical model representing an active suspension system.

Despite the theoretical advantages of Voice Coil Actuators (VCAs) as active suspension actuators—due to their technical characteristics including rapid transient response, backlash-free direct drive, and high control linearity—their commercialization continues to confront several fundamental obstacles that appear insurmountable. The primary technical bottleneck is their excessively high energy dissipation. To produce the significant control forces necessary for effective suspension operation, a VCA must function at elevated peak currents, resulting in instantaneous power consumption levels reaching several hundred kilowatts—vastly exceeding the supply capacity of conventional vehicle energy systems. Additionally, their inherently limited thrust density, combined with challenges in achieving force amplification through mechanical structures, restricts their applicability on heavy-duty platforms. Furthermore, the substantial thermal effects induced by high current usage not only disrupt control accuracy due to fluctuations in coil resistance but also present considerable challenges for system thermal management design. This challenge ultimately increases complexity, cost, and weight implications. Lastly, the considerable mass of the actuator itself can adversely affect unsprung mass dynamics and thereby compromise overall vehicle handling performance. In conclusion, this combination of technical constraints has collectively relegated VCA-based active suspension solutions primarily to theoretical research stages and experimental validation efforts.

2.1.2. Moving-Magnet Linear Motor (Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor, PMSLM)

The Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor (PMSLM) employs high-energy-product rare-earth permanent magnet materials, such as Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB), as its excitation source. This design eliminates the need for additional excitation windings and the corresponding excitation losses, thereby achieving exceptionally high energy conversion efficiency and power factor. In particular, within the moving-magnet configuration, the armature winding—responsible for generating a significant amount of heat—is positioned in the stator. This strategic placement facilitates an efficient connection to the vehicle chassis or other heat-dissipating structures, forming an effective thermal pathway. Consequently, this design mitigates the thermal bottleneck often encountered in moving-coil actuators (VCAs), ensuring both thermal stability and operational reliability under conditions of high power and long strokes [32].

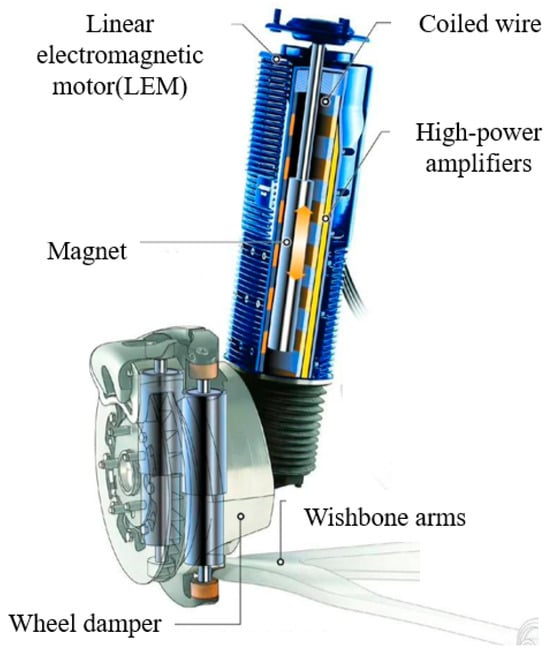

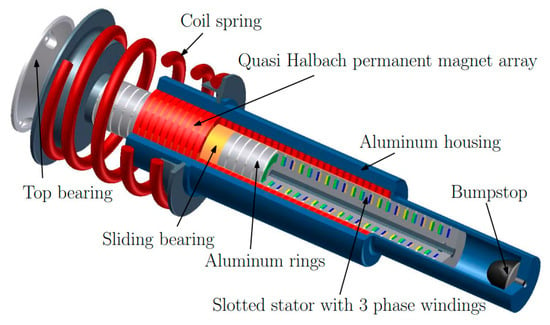

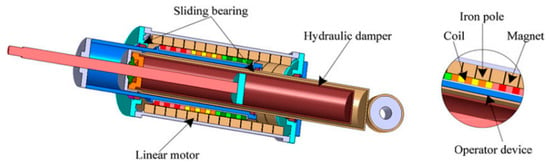

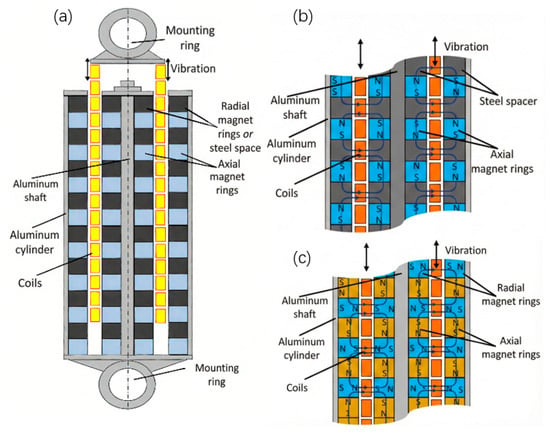

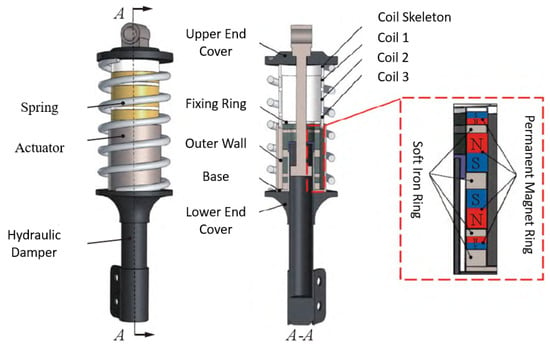

As shown in Figure 3, Bose Corporation publicly showcased its independently developed linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension system on a Lexus LS400. The test results indicated that the electromagnetic suspension achieved what can be described as a “perfect” control effect—characterized by “no squat during acceleration, no dive during braking, no roll during cornering, and no shaking over bumps” [33]. Professor Kim from Texas A&M University [34,35] has designed various control methods for application to linear electromagnetic actuators, demonstrating that linear electromagnetic active suspensions can significantly enhance vehicles’ dynamic performance. Researchers Gysen et al. [36,37,38] from Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands proposed an active electromagnetic suspension system featuring a tubular permanent magnet actuator arranged in parallel with a passive spring, as shown in Figure 4. This design also incorporates integrated passive eddy-current damping, which employs the eddy-current effect to generate damping force, thereby improving energy utilization efficiency under diverse driving conditions. As shown in Figure 5, Ding et al. [27,39,40] from Jiangsu University have innovatively combined a permanent magnet synchronous linear motor with a variable reluctance motor to achieve a highly integrated and compact structure. This configuration enables synergistic operation of the actuators: the PMLSM delivers high-dynamic-response active control forces while the VRM provides variable passive damping/stiffness forces with reduced energy consumption, thus achieving functional complementarity. Tang et al. [41] from Stony Brook University in the USA built upon a single-layer tubular linear electromagnetic actuator by replacing the conventional soft magnetic steel spacer rings with radial magnets. They also introduced a dual-layer magnet configuration that integrates both axial and radial magnets, as shown in Figure 6. This innovative dual-layer design achieved superior power density and damping density. Furthermore, Sun et al. [42,43] from Shenyang University of Technology incorporated a linear motor between the spring and the damper, thereby endowing the suspension system with dual functionalities: active control and energy harvesting, which demonstrated effective body attitude control under complex operating conditions, which is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 3.

The linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension developed by Bose Corporation (Framingham, MA, USA).

Figure 4.

The linear electromagnetic actuator proposed by the Eindhoven University of Technology.

Figure 5.

The linear motor actuator designed by Ding et al. [27,39,40]: Schematic of the hybrid electromagnetic actuator.

Figure 6.

Double-layer LETs designed by Tang et al. [41]: (a) Overview, (b) With axial magnets and steel spacers, (c) With both axial and radial magnets.

Figure 7.

The linear hybrid electromagnetic actuator designed by Sun et al. [42,43].

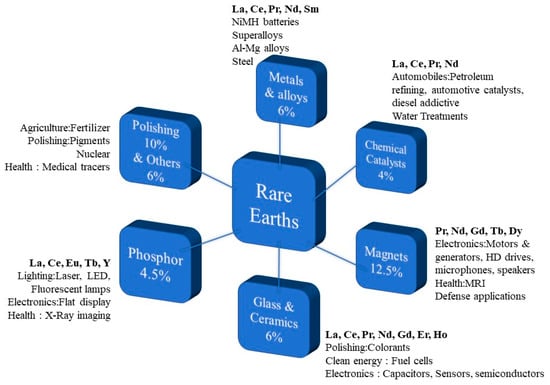

Despite its dominant position in configuration design, the PMSLM confronts three intrinsic limitations that hinder its widespread application. The first is electromagnetic nonlinearity. Interactions between stator slots and permanent magnets, combined with end effects, generate inherent cogging forces and thrust ripples. These parasitic fluctuations disrupt control smoothness, particularly during low-speed micro-movements. Furthermore, magnetic field saturation introduces strong nonlinearities during high-speed operation. These characteristics often couple with mechanical vibrations, which significantly complicates the development of accurate models and robust control strategies. The second challenge is thermal instability. PMSLMs typically rely on sintered Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) magnets for excitation. These materials are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations. Under continuous high-load conditions, such as driving on rough terrain, the actuator generates substantial heat. Without efficient thermal management, heat accumulation can trigger irreversible demagnetization. This results in permanent performance degradation or even complete actuator failure [44]. The third constraint is economic and industrial viability. The superior performance of PMSLMs depends heavily on rare-earth materials. This dependency drastically elevates manufacturing costs. Moreover, it exposes the technology to supply chain vulnerabilities driven by the geopolitical dynamics of rare-earth resources. These factors currently restrict the adoption of PMSLMs primarily to high-end or specialized vehicle platforms.

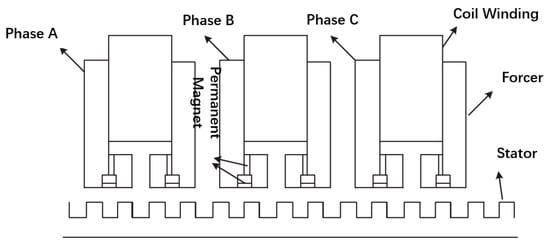

2.1.3. Switched Reluctance Linear Motor (LSRM)

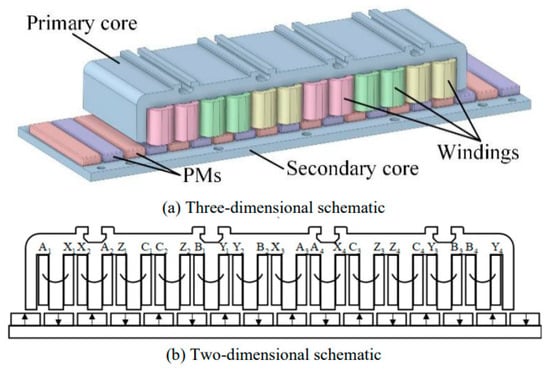

The Switched Reluctance Machine (SRM) is a type of motor characterized by its doubly salient pole structure, which operates without permanent magnets or rotor windings, as shown in Figure 8 [45]. Its functioning principles are founded on the minimum reluctance principle; sequential excitation of the stator phase windings generates an electromagnetic field that attracts the salient poles on the mover, thereby facilitating either linear or rotary motion. Owing to its robust construction, cost-effectiveness, high-temperature resilience, and exceptional fault-tolerant capabilities, the SRM is regarded as a formidable candidate for applications in demanding automotive environments, such as integrated starter/generator systems [46].

Figure 8.

Structure of a switched reluctance linear motor.

Nevertheless, the intrinsic doubly salient architecture and pulsed excitation mode of the SRM give rise to significant challenges related to thrust ripple and acoustic noise—issues that remain pivotal constraints on its applicability. Consequently, academic research has predominantly concentrated on advanced control strategies and optimization of motor topology. At the design level of these motors, Ma et al. [47] utilized finite element simulations to explore various methods aimed at actively mitigating thrust ripple through modifications in mover slot geometry. Additionally, considering the highly nonlinear electromagnetic characteristics inherent in SRMs, accurate modeling emerges as a crucial prerequisite for attaining high-performance control solutions. The research conducted by Xue et al. [48] underscored the importance of accounting for intricate factors such as mutual inductance between phases during this modeling process.

Although the switched reluctance motor (SRM) presents several advantages—such as robustness, high-temperature resistance, and impressive fault tolerance due to its lack of permanent magnets—it theoretically offers a highly resilient drive option for automotive applications. However, its significant thrust ripple and acoustic noise, which arise from its doubly salient structure and pulsed excitation, constitute primary technical limitations that impede its adoption in passenger car suspensions. To address these adverse effects, reliance on complex nonlinear models and sophisticated control algorithms with substantial computational demands is necessary. This requirement significantly escalates both the development complexity and cost of the control system. Furthermore, when compared to permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs), SRMs typically exhibit lower power density and efficiency—especially at low speeds—and their distinct power converter topology is inherently more intricate. These combined factors present challenges for SRMs in competing with permanent magnet motors within the realm of passenger car suspensions. Consequently, their application potential tends to be concentrated in specialized vehicles or specific industrial contexts that are less sensitive to noise and vibration or have exceptionally high demands for reliability and temperature resistance [49].

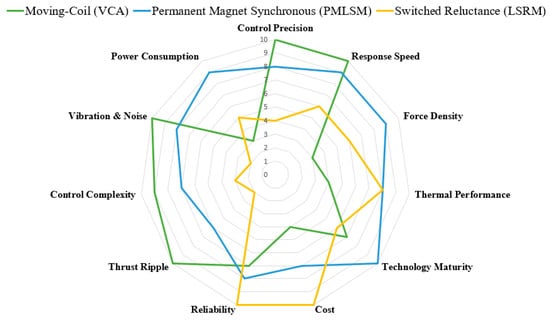

To provide a clearer perspective on the selection of actuator configurations, a comparative summary of the three motor types—focusing on performance, cost implications (specifically rare-earth dependence), and application maturity—is presented in Table 1. This comparison complements the performance radar chart shown in Figure 9.

Table 1.

Comparative summary of typical linear motor configurations for electromagnetic suspension.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of different linear motor types.

Therefore, the permanent magnet synchronous linear motor (PMSLM) currently represents the most promising mainstream technological pathway for electromagnetic suspension actuators. In contrast to the inherent limitations of moving-coil actuators concerning energy consumption and thermal dissipation, as well as the challenging thrust ripple issues associated with switched reluctance motors, the PMSLM showcases significant advantages in terms of power density, energy efficiency, and thermal management. While it does encounter challenges such as cogging force, these are considered engineering problems that can be addressed through design optimization and advanced control algorithms. This firmly establishes its pivotal role in the advancement of high-performance active suspensions.

2.2. Challenges in Structural Design

2.2.1. Mass-Volume Optimization

In the field of vehicle dynamics theory, unsprung mass is a critical parameter influencing both ride comfort and handling performance. However, the electromagnetic actuator itself adds considerable mass, and its placement on the vehicle significantly affects the overall unsprung mass. Consequently, a fundamental design challenge arises: how to maximize reductions in the volume and weight of the actuator while ensuring adequate thrust output [50,51].

Jiang et al. [52] employed a multi-objective topology optimization method for the housing and brackets of the actuator, achieving substantial weight reduction while adhering to stiffness constraints. This approach provides an effective model for lightweight design. Regarding material applications, Vishrut Shah et al. [53] developed an automotive chassis using titanium, aluminum, and carbon fiber composite materials. When compared to traditional steel chassis designs, their innovative structure demonstrated a 64% increase in stiffness alongside a 32% reduction in weight—highlighting the significant potential of new materials for enhancing strength-to-weight ratios. Furthermore, optimizing core motor design to enhance force density can also contribute to equivalent objectives in lightweighting pursuits. For instance, Serdal Arslan’s novel tubular flux-switching permanent magnet linear motor [54] achieved increased force density without noticeably augmenting overall system mass; it exhibited commendable vibration-damping performance within semi-active suspension systems.

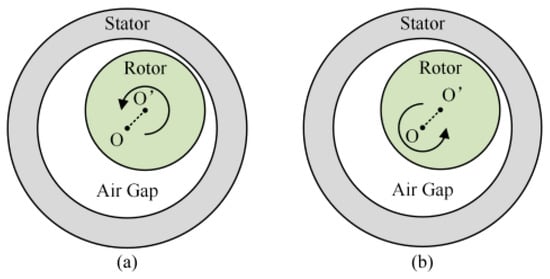

2.2.2. Axial Gap and Eccentric Load Compensation

In electromagnetic suspensions utilizing linear motor technology, the performance of the actuator is highly contingent upon maintaining a precise and uniform radial air gap between the stator and the mover. However, under real-world vehicle operating conditions—such as during cornering or braking—the suspension actuator experiences considerable lateral loads that result in radial eccentricity of the mover relative to the stator, as shown in Figure 10. This eccentricity disrupts the symmetry of the magnetic field within the air gap, thereby generating a detrimental radial parasitic force commonly referred to as Unbalanced Magnetic Pull (UMP) [55]. The presence of UMP further exacerbates this eccentricity of the mover. Not only does this force lead to increased friction and wear within the guidance mechanism, but it also induces vibration and noise. More critically, UMP significantly compromises control accuracy over the actuator’s primary thrust. In extreme instances, it can even provoke mechanical contact between the mover and stator, potentially leading to systemic failure. As a consequence, effectively compensating for lateral loads while minimizing UMP represents a fundamental challenge in designing robust electromagnetic suspensions.

Figure 10.

Schematic of mover eccentricity: (a) static eccentricity, (b) dynamic eccentricity.

Current research on the suppression of Unbalanced Magnetic Pull (UMP) predominantly centers around passive strategies, which are achieved through the optimization of both the motor’s electromagnetic configuration and its mechanical structure. At the electromagnetic design level, researchers have explored various avenues. Xinjie Wen et al. [56] employed a parallel winding structure and selected an appropriate slot-pole combination to significantly enhance the actuator’s inherent robustness against eccentric loads without complicating control mechanisms. Drawing upon magnetic field modulation theory, Yang Gongde et al. [57] proposed optimizing structural parameters to adjust the initial phase of key harmonics, thereby improving the self-cancellation effect among different harmonic components of UMP. At the mechanical structure level, Dongwen Wang et al. [58] advanced a strategy for optimizing support points within the rotor-bearing system. Their findings indicated that simply adjusting the relative positions of components could reduce maximum vibration acceleration due to UMP by 54.9%. Furthermore, an accurate UMP model serves as a fundamental basis for both design optimization and active control techniques. Emami et al. [59] innovatively simplified UMP calculations into a second-order algebraic vector function based on stator current variables. This model not only maintains high concordance with results from Finite Element Analysis (FEA) but also enhances computational speed by several orders of magnitude.

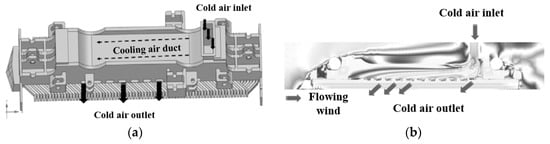

2.2.3. Thermal Management Technology

Thermal management plays a pivotal role in ensuring the stable performance and operational reliability of electromagnetic suspension actuators operating under high-power, long-stroke conditions. When these actuators continuously deliver high thrust to contend with rough roads or aggressive driving scenarios, significant heat is generated due to copper losses in the windings and iron losses in the core. If this heat cannot be efficiently dissipated, a rapid increase in temperature within the motor can result in a series of severe complications. Consequently, for automotive active electromagnetic actuators, passive cooling via natural convection proves inadequate. An effective active cooling system must be devised, with current research primarily focusing on two technical approaches: forced-air cooling and liquid cooling, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

The improved linear motor with an air duct and its cooling airflow diagram: (a) three-dimensional structural schematic of the motor housing; (b) cross-sectional view showing the cooling airflow distribution.

Forced-air cooling technology offers simplicity in structure and cost-effectiveness; however, its capacity for heat dissipation remains limited [60]. Research efforts are dedicated to enhancing its cooling efficiency. Shewalkar et al. [61], through thermal analysis, quantified how variations in cooling air velocity affect the internal temperature distribution and hotspot locations within permanent magnet synchronous motors. In order to address the limitations associated with conventional air-cooling methods, Zhang Yongcai et al. [62] developed a design featuring an integrated through-type air duct that significantly improved both cooling efficiency and temperature uniformity by expanding the convective heat transfer area. Furthermore, Li Xunbao et al. [63] established a comprehensive design process encompassing loss calculations, multiphysics simulations, and experimental validation—systematically analyzing how key parameters of the cooling fan (air volume and air pressure) impact motor temperature rise thus providing quantitative data essential for engineering decision-making.

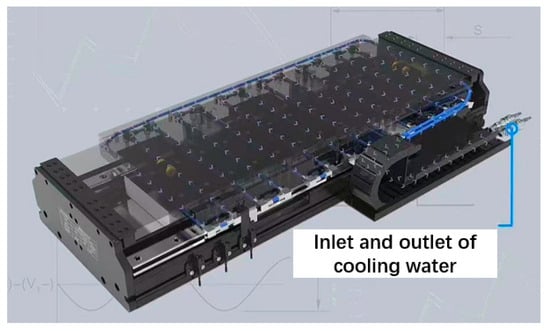

Liquid cooling technology is widely acknowledged as the most effective method for heat dissipation in high-performance electromagnetic suspensions, as shown in Figure 12. Current research emphasizes the structural optimization of cooling channels alongside multi-physics coupling analysis. Rui Xu [64] and Weihua Chen [65], among others, have proposed innovative liquid cooling configurations, including an embedded interleaved dual-channel design and a double-layer spiral structure. Utilizing techniques such as electromagnetic-thermal-fluid multi-physics coupling modeling and multi-objective genetic algorithms, these researchers optimized the geometric parameters of the water channels to achieve a synergistic reduction in both peak motor temperature and temperature non-uniformity. Moreover, research efforts have expanded towards integrated systems. Zhu Jiyuan et al. [66] conceptualized a comprehensive integrated water-cooling solution for a dual-axis linear motor module that encompassed the motor stator, slider, and ball screw, yielding impressive results.

Figure 12.

A permanent magnet synchronous linear motor with a water-cooling structure.

2.2.4. Reliability Technology

As a critical component of the chassis that directly impacts driving safety, the electromagnetic suspension actuator must demonstrate exceptional reliability throughout the vehicle’s entire lifecycle—potentially extending over a decade or encompassing hundreds of thousands of kilometers—while functioning in challenging in-vehicle environments characterized by extreme temperatures, high humidity, salt spray corrosion, gravel impact, and high-frequency vibrations. Consequently, designing for its reliability presents a systematic engineering challenge that involves addressing sealing and protection issues, shock and vibration resistance, and wear prevention. These efforts are all aimed at ensuring stable performance and functional safety of the actuator across its full operational lifespan.

Sealing and environmental protection form the cornerstone of actuator reliability; their primary objective is to prevent external contaminants such as moisture and dust from penetrating the system. Typically, protection levels are required to meet IP67 standards [67]. This level of safeguarding is accomplished through optimized designs for sealing components as well as comprehensive evaluations of the sealing structure itself. Jie Wei Li et al. [68] employed Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to pinpoint key mechanical failure factors associated with a Y-shaped sealing ring; they effectively enhanced both wear resistance and service life by optimizing its lip geometry. At a structural level, Yi Xiaojun et al. [69] also utilized FEA to perform modal and stress analyses on the sealing cylinder of a tubular linear motor in order to assess dynamic characteristics alongside structural integrity under complex excitations—thereby ensuring robust protection for internal core components.

To endure instantaneous high-intensity loads, such as those encountered during road impacts, it is essential to enhance mechanical robustness. A pivotal process in this enhancement is potting (or encapsulation) [70], which entails the application of materials like thermally conductive epoxy resin to vacuum-infill the stator windings and permanent magnets, subsequently curing them into a high-strength, void-free solid unit. This method significantly improves the shock and vibration resistance of internal components while also aiding in heat dissipation and moisture protection. Furthermore, conducting modal analysis and impact response assessments on critical load-bearing components—such as the housing and brackets—to identify and fortify structural weak points is an indispensable step towards ensuring structural reliability.

Wear protection primarily focuses on the linear guidance mechanism and dynamic sealing elements within the actuator, which are subjected to tens or even hundreds of millions of reciprocating cycles. Prolonged exposure to high-frequency, high-load frictional contact is among the primary contributors to actuator performance degradation (e.g., decreased precision, unusual noise) or even complete failure. Consequently, material selection along with tribological design necessitates special attention. A prevalent solution for achieving prolonged lifespan with low-friction motion involves employing a guide shaft featuring a hardened surface combined with self-lubricating bushings crafted from advanced engineering plastics. Moreover, comprehensive investigation into lubrication dynamics and wear mechanisms between the dynamic seal lip and reciprocating shaft—as well as developing long-lasting greases or utilizing self-lubricating sealing materials—is crucial for maintaining effective sealing performance throughout the entire product lifecycle.

2.3. Summary

This chapter systematically reviewed the configurations of linear motor-based electromagnetic suspensions. By analyzing the electromagnetic topologies, the Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor (PMSLM) was identified as the mainstream technical pathway due to its superior power density and control performance, despite the cost and thermal challenges discussed in Section 2.1.2. In contrast, while the Switched Reluctance Linear Motor (LSRM) offers cost/robustness benefits, its application is currently constrained by the NVH issues noted in Section 2.1.3. Regarding mechanical design, the review highlighted critical engineering challenges including mass-volume optimization, UMP compensation, and thermal management, summarizing state-of-the-art solutions for creating a robust actuator hardware foundation.

3. Suspension Control Strategies

The development of control strategies for electromagnetic suspension begins with the formulation of fundamental control objectives. These objectives are intricately linked to the key dynamic performance characteristics of the vehicle and are evaluated through a set of quantifiable performance indices. Typically, the control objectives encompass three essential dimensions: ride comfort, handling stability, and energy efficiency.

3.1. Mapping of Structural Challenges to Control Strategies

As discussed in Section 2, linear motor actuators inherently exhibit structural and electromagnetic imperfections, such as thrust ripple, unbalanced magnetic pull (UMP), and thermal parameter drift. While structural optimization can mitigate these issues to some extent, it is often constrained by manufacturing costs and physical limits. Consequently, the burden of “fine-tuning” system performance falls on the control strategy. Control algorithms must not only achieve the primary suspension objectives (comfort and handling) but also act as a “software compensator” for hardware limitations. To provide a clear logical link between the actuator physics (Section 2) and control methodologies (Section 3), Table 2 summarizes the mapping between key structural challenges and their corresponding control solutions.

Table 2.

Mapping of structural/electromagnetic challenges to control solutions.

3.2. Classical Control Methods

Classical control methods are conventionally applied in single-input single-output (SISO) linear time-invariant (LTI) systems. The primary analytical tools utilized within these methods include frequency-domain analysis and transfer function models. Renowned for their intuitive nature, practical applicability, and exceptional problem-solving capabilities in engineering contexts [71], impacts these approaches serve as foundational techniques in this field. In this section, we will analyze three representative methodologies: Skyhook and Groundhook control, Linear Quadratic optimal control, and Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controllers alongside their enhanced algorithms.

3.2.1. Skyhook and Groundhook Control

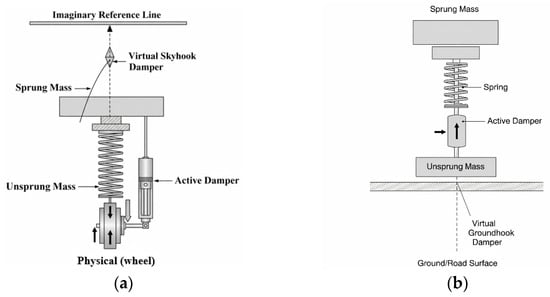

Skyhook and Groundhook control represent two of the most fundamental and classic concepts in the realm of active and semi-active suspension systems, as shown in Figure 13. These approaches aim to address two core yet often conflicting objectives: ride comfort and handling stability. Skyhook control seeks to minimize vehicle body vibrations to enhance ride comfort, while Groundhook control prioritizes improving tire-to-road contact for enhanced handling stability. Given the inherent difficulty in simultaneously achieving both ideal control objectives in practice, recent research efforts have focused on developing advanced hybrid or adaptive control strategies designed to strike an optimal balance between these competing goals.

Figure 13.

Schematic of Skyhook and Groundhook control principles: (a) Skyhook control, (b) Groundhook control.

To synergistically optimize the ride comfort and handling stability of active suspensions, researchers have proposed various Skyhook-Groundhook hybrid control strategies. Early research, such as that by Yerge et al. [72], proposed a controller based on discrete switching logic, which toggled between the two control modes by evaluating the product of the sprung and unsprung mass velocities. To overcome the abruptness of switching control, subsequent research shifted towards hybrid control with continuous adjustment. Changning Liu et al. [73] introduced a frequency-varying adaptive weighting factor. This achieves a dynamic balance of control objectives adapted to road excitation. Similarly, Vu Van Tan et al. [74] utilized a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to search for optimal weighting parameters. This approach offers an automated solution to balance comfort and handling. Yi Yang et al. [75] then integrated Skyhook and Groundhook control into a unified framework. They used Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to tune key control parameters offline. To further enhance the controller’s adaptability, researchers have explored more advanced intelligent algorithms. Kou Farong et al. [76] introduced the feedback mechanism of the biological endocrine system into the controller design, constructing a bionic intelligent algorithm that achieved nonlinear, continuous, and adaptive regulation of the control objectives. Liu Zhonghai et al. [77], on the other hand, focused on improving the performance of a single controller. The fuzzy logic Skyhook controller they designed could adjust the damping force online based on the real-time velocities of the vehicle body and suspension, significantly improving ride comfort compared to traditional fixed-gain Skyhook control.

3.2.2. Linear Quadratic Optimal Control (LQR/LQG)

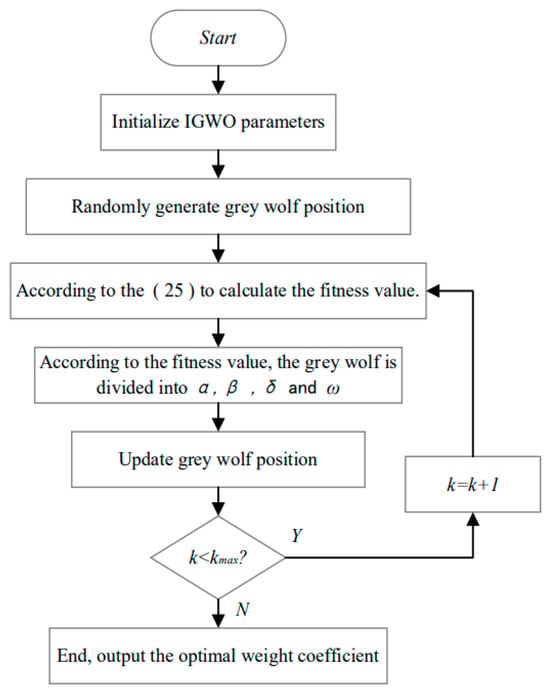

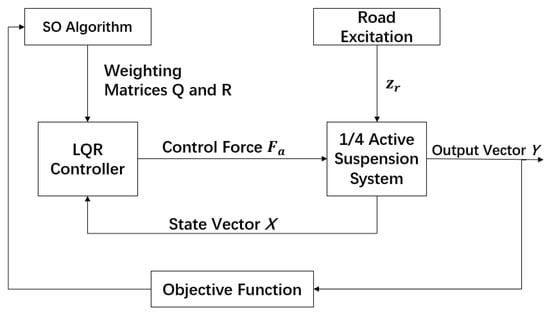

Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) is a classic method in active suspension control due to its ability to systematically trade off conflicting performance indices within a unified framework. However, its performance is highly sensitive to the selection of weighting matrices Q and R. Traditional trial-and-error tuning relies heavily on engineering experience and often fails to guarantee a global optimum.

To address the challenge of weight optimization, recent research has shifted towards intelligent bio-inspired algorithms. These methods aim to automate the search for optimal parameters by minimizing a comprehensive objective function. Swarm intelligence algorithms have proven particularly effective in this regard. For instance, Zhuo et al. [78] and Başak et al. [79] employed Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) and its hybrid variants to enhance global search capabilities, as shown in Figure 14. Similarly, other heuristic approaches, such as the Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (AFSA) [80], Improved Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO) [81], and the novel Snake Optimizer (SO) [82] (Schematic is shown in Figure 15), have been successfully implemented to escape local optima.

Figure 14.

Flowchart of an Improved Grey Wolf Optimization algorithm used to optimize an LQR controller.

Figure 15.

Schematic of the Snake Optimizer (SO) algorithm for optimizing an active suspension LQR controller.

In comparison to empirical tuning, these algorithm-optimized LQR controllers demonstrate superior robustness and a better balance between ride comfort and handling stability. Furthermore, for practical implementations involving sensor noise, Duan et al. [83] extended this optimization logic to LQG controllers, utilizing Genetic Algorithms (GA) to tune variable weights, thereby enhancing adaptability to diverse road conditions.

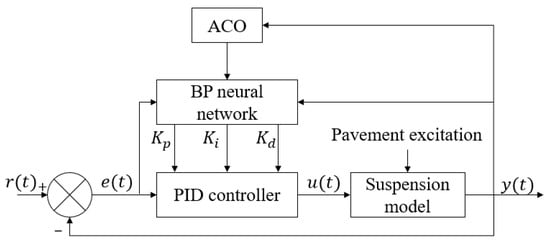

3.2.3. PID and Its Improved Algorithms (Anti-Windup, Gain Scheduling)

The Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller, owing to its simple structure, high reliability, and ease of engineering implementation, has played a significant role in the early research and basic applications of active suspensions. However, the fixed parameters of a traditional linear PID controller make it difficult to adapt to the inherent nonlinearities of the suspension system and the variable operating conditions of the vehicle. Furthermore, the physical limits of the actuator’s force output can easily lead to integral windup, which deteriorates control performance. To overcome these limitations, recent research has focused on combining PID control with various advanced algorithms, pursuing in-depth improvements from multiple perspectives, including multi-variable coordination, gain scheduling, and offline global optimization.

To address the limitations of traditional single-variable PID in handling coupled motions such as vertical heave and pitch, Zhou Peng et al. [84] proposed a multi-variable PID design method based on model decoupling and parameter tuning using a characteristic matrix, achieving coordinated multi-degree-of-freedom control. To endow the controller with online adaptive capabilities, researchers have introduced intelligent algorithms for gain scheduling. Wangshui Yu et al. [85], in conjunction with road recognition, constructed a variable universe fuzzy PID controller that could self-adjust its parameters according to operating conditions and used a chaos particle swarm algorithm for its global optimization. Similarly, Yang [86] and Chen et al. [24], respectively, applied fuzzy PID and single-neuron adaptive PID to the leveling and height stability control of agricultural vehicles, verifying their effectiveness in rapid response and suppression of abrupt load changes. In pursuit of superior control performance, researchers have further developed multi-level, nested intelligent control systems. For example, as shown in Figure 16, the ACO-BP-PID composite strategy proposed by An Xinkai et al. [87] utilizes an Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) algorithm to offline-optimize the initial weights of a BP neural network, which then online-tunes the PID parameters. This controller, optimized by a dual layer of intelligent algorithms, demonstrated stronger comprehensive performance in vibration suppression compared to traditional PID and single-layer intelligent PID controllers.

Figure 16.

Control structure diagram of a BP neural network PID optimized by ACO.

3.3. Advanced Control Strategies

Although classical control methods have laid the theoretical foundation for active suspensions, they typically rely on precise linearized models. This limits their control performance when dealing with complex real-world problems such as the strong nonlinearities, time-varying parameters, and variable operating conditions inherent in vehicle suspensions. To overcome these limitations, researchers have introduced modern control theory into the field, developing a series of advanced control strategies. These methods, based on state-space equations, are a further extension and continuation of classical control theory, focusing on the evolution of state variables in multi-input multi-output (MIMO) control systems [88,89].

3.3.1. Adaptive Control

Adaptive control is an advanced control theory that can automatically adjust controller parameters to adapt to changes in the controlled object and the external environment [90]. It is exceptionally well-suited for addressing the parameter uncertainties and time-varying characteristics present in vehicle suspension systems [91,92]. In the active suspension field, adaptive control is primarily realized through two technical approaches: Model Reference Adaptive Control (MRAC) and Self-Tuning Control (STC).

The core idea of Model Reference Adaptive Control (MRAC) is to first define a reference model with a desired dynamic response. Then, a controller with adjustable parameters is designed, and an adaptation law is used to online-adjust these parameters based on the error between the actual system output and the reference model output. This forces the dynamic characteristics of the closed-loop system to ultimately track and approximate those of the reference model. To address parameter uncertainties such as changes in vehicle load, Hu Guoliang et al. [93] designed an MRAC scheme based on Lyapunov theory, verifying its vibration-damping performance under different loads. To enhance robustness against external disturbances and non-ideal actuator dynamics, Mousavi et al. [94] proposed a Tube-based Model Reference Adaptive Control (TMRAC) that incorporated a disturbance observer, achieving active compensation for unknown disturbances. Taking this further, MRAC has been integrated into more complex control frameworks. For instance, Yeneneh et al. [95] constructed a hybrid architecture that coordinated H∞, MRAC, and frequency-domain optimization to systematically address multiple control challenges. Its application has also been extended to multi-modal vehicle platforms like legged-wheel vehicles, validating the theory’s effectiveness in handling strongly nonlinear coupled systems [96]. At the theoretical frontier, Chen Yandong et al. [97] extended the reference model of MRAC from integer-order to fractional-order. Leveraging the advantages of fractional-order models in describing complex dynamics, they defined more flexible ideal dynamic targets for the suspension, opening up new theoretical avenues for improving control performance.

The efficacy of Self-Tuning Control (STC) hinges fundamentally on the accuracy of its online system identification. Research in this domain illustrates a clear evolutionary trajectory of the estimator technology: from traditional linear methods to advanced intelligent recognition. Initial approaches relied on classical mathematical techniques like Recursive Least Squares (RLS) to identify vehicle parameters online [98,99]. While computationally efficient, these linear methods often struggle to track rapid parameter variations in strongly nonlinear suspension systems. To overcome this limitation, subsequent research integrated intelligent algorithms as nonlinear estimators. For instance, Fuzzy Logic [100], Radial Basis Function Neural Networks (RBFNN) [101], and improved NARMA-L2 models [102] have been employed to approximate total system uncertainty in real-time. These methods offer superior tracking of unmodeled dynamics and nonlinear friction compared to traditional linear estimators. Representing a further leap in adaptability, recent studies have incorporated Deep Learning to introduce predictive capabilities. By utilizing Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for road recognition [103], the controller can evolve from “passive adaptation” (reacting to past errors) to “proactive compensation” (anticipating road changes), significantly reducing the phase lag inherent in traditional feedback mechanisms.

3.3.2. Robust Control

Robust control aims to ensure that a control system can maintain stability and meet predefined performance specifications in the presence of model uncertainties and external disturbances [11]. It does not rely on the online identification of uncertainties; instead, it involves designing a fixed controller that guarantees good performance across a predefined range of all possible uncertainties. In the active suspension field, control and Sliding Mode Control (SMC) are the two most widely applied and theoretically mature robust control methods.

H∞ control achieves optimal disturbance rejection by minimizing the H∞ norm of the closed-loop transfer function from external disturbances to the system’s performance output. In the application of the classic H∞ control framework, Zhen Wang et al. [104] used a mixed-sensitivity approach, constructing a robust controller that could effectively trade off among multiple conflicting objectives—such as ride comfort, handling stability, and control energy consumption—by carefully designing performance weighting functions. To further enhance controller reliability, Zhendong Liu et al. [105] introduced the concept of “non-fragile” control. The H∞ control framework they constructed not only considered parameter uncertainties in the vehicle model but also simultaneously accounted for the controller’s own gain variations, resulting in a non-fragile controller that is insensitive to implementation errors. Furthermore, to overcome the conservatism of traditional H∞ control, which arises from optimizing over the entire frequency domain, Hui Jing et al. [106] proposed robust finite-frequency H∞ control. This approach strictly confines the optimization of performance indices to specific frequency bands that have the most significant impact on suspension performance, thereby achieving superior vibration suppression. At the same time, to make H∞ control more applicable to engineering practice, researchers have worked to address the time-delay issues caused by digital control and actuator response. Gao Xiaolin et al. [107] modeled the active suspension as a discrete-time system with time delay and designed a corresponding discrete H∞ robust controller. Sun Dong et al. [108] more specifically modeled the actuator’s response lag as a time-delay element and integrated it into an H2/H∞ robust control framework. These efforts have extended the application of H∞ control from ideal continuous-time models to more challenging discrete-time systems with delays. Additionally, H∞ control has also been applied in the integrated design of innovative suspension hardware.

Sliding Mode Control (SMC) [109] has received considerable attention in active suspension control due to its strong robustness to matched uncertainties. However, the chattering phenomenon caused by its discontinuous switching term is a core challenge that urgently needs to be addressed [91]. To suppress chattering, early research focused on improving first-order sliding mode controllers. Xu Ming et al. [110] effectively weakened the control output’s chattering by designing an improved exponential reaching law and using a saturation function to replace the discontinuous sign function. Samsuria et al. [111] proposed a more systematic design paradigm: using Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) theory to design an optimal sliding surface and combining it with optimization algorithms to systematically tune key parameters like the sliding surface coefficients and the saturation function’s boundary layer. This provided a complete solution for designing controllers that balance both robustness and low chattering. To eliminate chattering at its source, Higher-Order Sliding Mode Control (HOSMC), particularly the Super-Twisting Algorithm (STA) which can generate a continuous control action, has become a more advanced solution. Furthermore, to enhance the adaptability of SMC in specific applications, Peng et al. [112], in the context of agricultural chassis leveling control, employed fuzzy logic to online-adjust the switching gain of the sliding mode control, achieving more stable real-time dynamic leveling.

3.3.3. Predictive Control

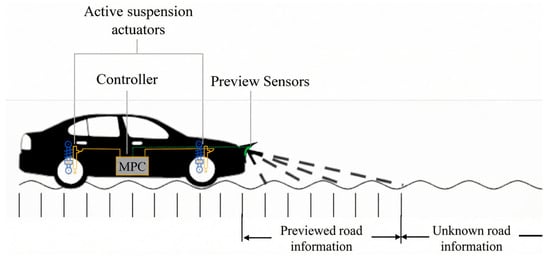

As shown in Figure 17, predictive control, especially Model Predictive Control (MPC), is considered one of the most ideal frameworks for solving complex suspension control problems due to its ability to online-optimize multi-objective performance, systematically handle physical constraints, and naturally incorporate future road information. Recent research has primarily focused on two directions: first, using MPC for multi-objective constrained optimization; and second, combining MPC with road preview information to achieve further performance breakthroughs.

Figure 17.

Schematic of a model predictive control active suspension with road preview functionality.

Even without external preview information, MPC can still serve as a powerful multi-objective constrained optimizer. To address the mismatch between the predictive model and the actual nonlinear dynamics of the vehicle, researchers have focused on integrating machine learning techniques with MPC. Gu Suying et al. [113] utilized a Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural network to online-identify and construct a high-precision suspension predictive model, thereby improving the optimization accuracy of the MPC. Furthermore, Mazouchi et al. [114] used a Gaussian Process (GP) to online-learn and compensate for prediction errors caused by model uncertainty, positioning machine learning as a parallel compensator for the MPC. When integrating road preview information, to cope with persistent model uncertainties, Papadimitrakis et al. [115] also employed an RBF neural network as an online estimator, achieving a deep fusion of preview MPC and intelligent estimation. To enhance the engineering practicality of MPC, researchers have improved the algorithmic framework itself. To address the computational burden, Wang Ruochen et al. [116] proposed a variable-horizon MPC, which significantly reduced the average computational load while maintaining performance by adaptively adjusting the prediction horizon online. Niaona Zhang et al. [117] proposed a distributed multi-agent MPC architecture, which decomposes the overall vehicle control task among four independent controllers for coordinated completion, greatly reducing the complexity and computational demands of centralized control. These studies are progressively transforming MPC from an idealized optimal controller into a more intelligent, efficient, and robust advanced control strategy capable of handling complex real-world operating conditions.

3.3.4. Intelligent Control

Intelligent control provides a powerful toolkit for solving the complex problems inherent in suspension systems—such as strong nonlinearities, model uncertainties, and multi-objective conflicts—by simulating human capabilities for logical reasoning, learning, and optimization. Unlike classical or modern control theories that rely on precise mathematical models, intelligent control methods are often data-driven or rule-based, offering greater adaptability and robustness.

Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC) simulates human reasoning by constructing “IF-THEN” rules, making it suitable for handling complex nonlinear systems that are difficult to model with precision [118]. In fundamental applications to active suspension, Dong Zhaowen et al. [119] used vehicle body velocity and acceleration as inputs to a fuzzy inference system to adjust suspension damping in real-time, effectively improving ride comfort. This application was subsequently extended to full-vehicle attitude control, as seen in the work of Pan Gongyu et al. [120], who designed a fuzzy controller capable of coordinated pitch and roll control based on a seven-degree-of-freedom (7-DOF) model. To overcome the limitations of fixed rules in traditional FLC, researchers have explored more advanced adaptive frameworks. Inspired by bionics, Kou Farong et al. [121] proposed an endocrine composite fuzzy control strategy that mimics biological hormone regulation mechanisms to achieve nonlinear, adaptive adjustment of control objectives. Another, more theoretically profound, technical path involves integrating fuzzy theory with modern robust control. Mohammad et al. [122] utilized a Takagi-Sugeno (T-S) fuzzy model to accurately describe the nonlinear suspension system, upon which they designed a gain-scheduled H∞ controller. This method not only guarantees the system’s robustness across the entire nonlinear operating range but also allows physical constraints, such as suspension travel, to be systematically integrated into the controller design, representing a cutting-edge direction for handling strongly nonlinear, multi-constraint problems.

Neural Networks (NNs), due to their nonlinear mapping and self-learning capabilities, play multiple roles in active suspension control, from online optimizers to end-to-end controllers [123,124]. Wang et al. [125] applied a BP neural network to the leveling of an agricultural machinery chassis, and its control effect was superior to that of traditional PID in terms of settling time, overshoot, and steady-state error. Taking this further, researchers have utilized Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) to construct end-to-end nonlinear control strategies. For example, Xuebin Zhu et al. [126] employed the DDPG algorithm, enabling the controller to autonomously learn the optimal control law by maximizing a comprehensive performance reward function through trial-and-error interaction with a simulation environment. This method does not require a precise dynamic model. To enhance the fidelity and adaptability of intelligent control, Huanqing Qiu et al. [127] proposed a new adaptive control paradigm that integrates a digital twin with an Artificial Neural Network (ANN). By providing continuous, real-time data feedback from a high-fidelity digital twin model to the ANN, they achieved a deep fusion and co-optimization of the physical system and its virtual counterpart.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) offers a data-driven paradigm that learns optimal control policies through environmental interaction. Current applications in active suspension generally follow two distinct technical pathways: hierarchical tuning and end-to-end control. The hierarchical approach utilizes RL as a high-level supervisor to optimize the parameters of a lower-level classical controller online. For example, Q-learning has been applied to adaptively tune PID gains [128,129] or to solve the LQR optimal control problem in a model-free manner [130]. This strategy retains the stability and explicit structure of classical control while endowing it with adaptability. In contrast, the end-to-end approach employs Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) algorithms to map state inputs directly to optimal control forces. Studies utilizing algorithms such as DDPG [126], TD3 [131], and PPO [132] have demonstrated that this method can theoretically achieve higher performance in handling high-dimensional, multi-objective constraints without reliance on precise dynamic models. However, compared to hierarchical methods, it faces greater engineering challenges regarding training convergence and policy interpretability. To provide a clear overview, the key features of these major suspension control strategies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Features of major suspension control strategies.

3.4. Energy Optimization Strategies

Beyond achieving enhanced ride comfort and improved handling stability, a significant advantage of linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension—distinguishing it from traditional high-energy-consumption active suspensions—is its potential for energy regeneration. However, effective realization and maximization of this potential necessitate systematic design and optimization at both the hardware (circuitry) and software (algorithm) levels. On one hand, efficient energy harvesting circuits must be developed to function as the physical interface for energy conversion and management. On the other hand, a sophisticated high-level control algorithm must intelligently assess and balance the conflicting objectives of vibration suppression and energy harvesting.

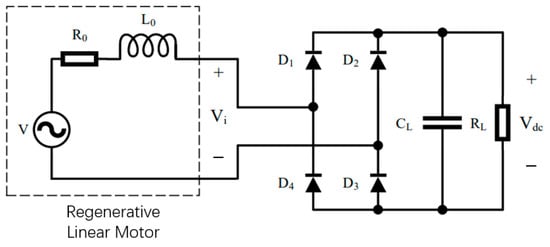

3.4.1. Regenerative Vibration Energy Harvesting Circuit Design

The energy harvesting circuit serves as the foundational component for transforming the alternating current (AC) electromotive force generated by the linear motor into a stable direct current (DC), which is subsequently fed into the vehicle’s energy storage system, as shown in Figure 18. Its design plays a crucial role in determining both the efficiency and flexibility of energy recovery.

Figure 18.

Schematic of a standard energy harvesting circuit.

Research on energy harvesting circuits seeks to delineate the performance boundaries of various topologies while enhancing conversion efficiency. Initial investigations concentrated on systematic comparative analyses of fundamental circuit designs. For instance, Lu Tao [133] and Hongfan Li [134], among others, conducted experimental and quantitative evaluations of configurations such as uncontrolled bridge rectifiers and basic DC-DC converters, including integrated Buck/Boost converters. Their work offers data-driven guidance for circuit selection. In summary, energy harvesting circuits are experiencing a distinct evolution from rudimentary passive rectification to controllable DC-DC conversion, ultimately progressing towards high-efficiency active synchronous switching technologies.

3.4.2. Energy-Efficiency Trade-Offs in Control Algorithms

Due to the inherent conflict between the damping force generated during the energy harvesting process and the active force required to achieve optimal comfort or handling, the core of research in this area is to design control strategies that can effectively trade off among multiple objectives.

To resolve the intrinsic conflict among ride comfort, handling stability, and energy harvesting in active/semi-active suspensions, the research first required a theoretical definition of this multi-objective problem. Lei Zuo et al. [135], through systematic analysis, clearly quantified the theoretical trade-off relationships and performance boundaries among these three main objectives, laying a theoretical foundation for subsequent research on coordinated control strategies. At the practical level, intelligent switching control is one of the mainstream technical approaches. Ding Renkai et al. [136] designed an “on-demand intervention” switching logic to maximize the reduction in active energy consumption while ensuring comfort. A more refined solution was designed by Xiangjun Xia [137,138], who not only developed an actuator with multiple modes, including pure damping and pure regeneration, but also utilized a hierarchical multi-objective fuzzy control strategy to achieve smooth and intelligent switching between these operating modes. In addition to mode switching, a composite control architecture is another effective path. The dual-loop fuzzy PID strategy proposed by Azmi et al. [139] decouples the control tasks: the outer loop is responsible for suppressing vibration, while the inner loop precisely regulates the duty cycle of the energy harvesting circuit. This architecture achieves parallel and coordinated optimization of the conflicting goals of vibration suppression and energy recovery.

The energy-efficiency trade-off control strategies for electromagnetic suspension are evolving towards becoming more intelligent and systematic. Through means such as operating condition recognition, mode switching, and composite control, a dynamic balance among multiple conflicting objectives—including comfort, handling, and energy recovery—has been achieved. Future research directions will likely focus more on deeply integrating suspension energy optimization into vehicle-level energy management systems and utilizing advanced AI technologies, such as deep reinforcement learning, to achieve end-to-end online policy optimization of the overall performance, thereby seeking globally optimal energy efficiency in more complex dynamic environments.

3.5. Experimental Validation and Quantitative Performance Analysis

Validating theoretical control strategies on physical platforms is critical for industrialization. Current research presents a multi-level validation landscape ranging from component simulations to full-vehicle tests, providing key quantitative indicators of performance improvement.

At the structural component level, quantitative gains are significant. For instance, through the use of novel composite materials, Shah et al. [53] achieved a 64% increase in chassis stiffness alongside a 32% reduction in weight. Similarly, by optimizing the rotor-bearing support points to counteract unbalanced magnetic pull, Wang et al. [58] successfully reduced the maximum vibration acceleration by 54.9%.

At the system control level, validation focuses on the trade-off between dynamics and energy. In quarter-car rig tests, Ding et al. [136] demonstrated that an “on-demand” control strategy could significantly reduce active energy consumption while maintaining vibration isolation performance. In more advanced full-vehicle applications, the Bose Corporation [33] reported qualitative breakthroughs, achieving “zero roll” and “zero pitch” during aggressive maneuvers, effectively eliminating squat and dive phenomena. Furthermore, in agricultural machinery applications, Wang et al. [125] validated via field tests that Neural Network control offered superior settling time and lower steady-state error compared to traditional PID controllers.

Despite these successes, it is important to note that systematic quantitative comparisons across different studies remain difficult due to the lack of unified testing benchmarks (e.g., standardized road inputs like ISO 2631 [140]). Future research must prioritize establishing these standards to facilitate direct performance benchmarking.

3.6. Summary

This chapter systematically reviewed the evolution of control strategies for electromagnetic suspension, transitioning from classical methods to advanced and intelligent techniques. Classical methodologies, such as Skyhook and PID, established the theoretical foundation but are limited by linear assumptions. Advanced strategies, including Adaptive and Robust control, overcame these limits by handling system uncertainties, while Model Predictive Control (MPC) introduced effective constraint management. Furthermore, Intelligent methods like Neural Networks and Reinforcement Learning have enabled data-driven solutions for complex nonlinear problems.

Crucially, the selection of these strategies must align with the specific vehicle platform. For heavy commercial and agricultural vehicles, the priority is managing drastic mass variations; thus, Robust and Adaptive controls are preferred for stability, ideally integrated with energy harvesting logic to improve efficiency. For high-performance luxury vehicles, where dynamics outweigh cost, MPC with road preview and Deep Reinforcement Learning are ideal for resolving multi-objective conflicts. Conversely, for economy platforms constrained by hardware costs, Improved PID and Fuzzy Logic remain the most pragmatic choices due to their low computational demands. This analysis highlights that future development requires not only algorithmic innovation but also the precise matching of control logic to specific engineering scenarios.

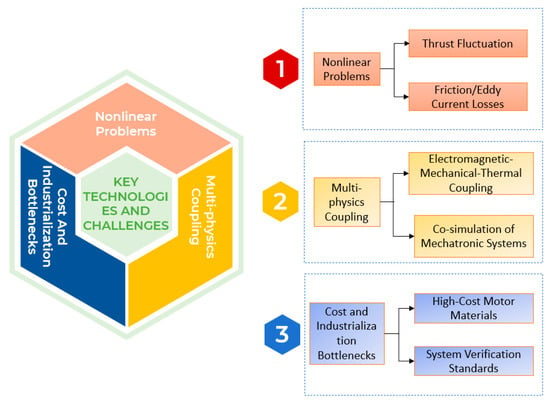

4. Key Technologies and Challenges

While linear motor-based electromagnetic suspension offers superior theoretical performance, its transition from laboratory research to widespread industrial application is confronted by a series of complex engineering challenges. As illustrated in Figure 19, these critical technical barriers can be systematically categorized into three core dimensions: nonlinear dynamics, multi-physics coupling mechanisms, and industrialization bottlenecks. This section will first address the nonlinear problems inherent to the actuator—specifically thrust fluctuation and friction—which fundamentally compromise control precision. Subsequently, it will examine the intricate coupling effects among electromagnetic, mechanical, and thermal fields that complicate high-fidelity modeling. Finally, the analysis will extend to economic and practical constraints, focusing on the high cost of motor materials and the absence of unified system verification standards, which currently hinder large-scale commercial adoption.

Figure 19.

Key technologies and challenges.

4.1. Nonlinear Problems

Although advanced control strategies have the potential to achieve superior performance in theory, their practical effectiveness in physical systems is significantly constrained by the inherent and complex nonlinear characteristics of electromagnetic actuators. These nonlinear factors pose one of the primary technical challenges currently confronting this field, as they directly influence control precision, operational smoothness, and overall energy efficiency. The fundamental issue lies in the fact that these nonlinearities are not merely static disturbances; rather, they are dynamic variables intricately linked to the system’s state (e.g., velocity, current, temperature). This complexity renders traditional linear control theory inadequate and necessitates a shift towards more sophisticated modeling and compensation strategies, as shown in Figure 19. This section will primarily address two core types of nonlinear problems: first, thrust fluctuations directly attributable to the motor’s electromagnetic design; second, frictional losses and eddy currents arising from both mechanical and electrical characteristics within the system.

4.1.1. Motor Thrust Fluctuation Compensation

During operation, the Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor (PMSLM) inevitably experiences parasitic force fluctuations, commonly referred to as thrust ripple. This phenomenon arises from the inherent characteristics of its magnetic circuit structure. The significance of this challenge is underscored by the fact that thrust ripple not only impacts static positioning accuracy but can also serve as an endogenous vibration source, continuously exciting system vibrations if its spectral components fall within the controller’s bandwidth or coincide with the mechanical resonance frequencies of the vehicle body or suspension. This dynamic coupling effect has been highlighted in research conducted by Xiaojun Yang et al. [141]. Consequently, suppressing thrust ripple is essential for achieving high-performance control. Current research primarily focuses on two approaches: structural optimization and control compensation.

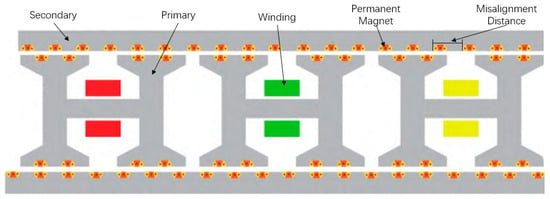

Structural optimization represents a fundamental approach, incorporating techniques such as the optimization of magnet pole shapes, the implementation of skewed pole/slot configurations, and the strategic arrangement of windings to mitigate harmonic magnetic fields. As shown in Figure 20, Miao Zhongcui et al. [142] utilized multi-objective optimization methods, including the Taguchi method, to synergistically adjust key structural parameters with the objective of achieving an optimal design characterized by “high average thrust and low thrust ripple.” However, there exists a highly nonlinear coupling relationship between design parameters and system performance, complicating accurate predictions regarding performance responses to variations in these parameters. Additionally, inherent conflicts arise among various performance indices (e.g., thrust density, efficiency, thrust ripple) and engineering constraints (e.g., cost, volume), necessitating careful optimization that balances these mutually restrictive objectives. For example, an excessive focus on optimizing cogging torque may result in diminished thrust density or increased manufacturing costs and process complexities. Moreover, once a design is finalized, its optimization effects become static and incapable of accommodating random fluctuations introduced by manufacturing tolerances or variations across material batches.

Figure 20.

The bilateral staggered-tooth topology proposed by Miao Zhongcui et al. [142]: the gray parts indicate the primary and secondary iron cores, the green and yellow blocks represent the armature windings, and the red and orange blocks represent the permanent magnets.

Control compensation is dedicated to the active cancellation of existing thrust ripple utilizing advanced algorithms. One approach originates from the electrical source, exemplified by the work of Jiawei Hu et al. [143], who introduced specific voltage harmonics to counteract current harmonics that generate fluctuating torque. A significant challenge associated with this method is its exceptionally high demand for precise online identification of motor parameters, particularly inductance; any parameter mismatch can severely degrade the compensation effect or even introduce new fluctuations. An alternative and more generalized strategy involves compensation based on a disturbance observer (DOB). The specialized observer devised by Mingfei Huang et al. [144] is capable of estimating the total thrust ripple in real time and providing feedforward compensation. However, this approach presents challenges related to balancing the observer’s bandwidth against its sensitivity to noise: while a higher bandwidth is essential for accurately tracking high-frequency ripples, it also amplifies measurement noise. Additionally, the inherent phase lag within the observer can further constrain compensation accuracy during high-dynamic responses.

In conclusion, a singular technical pathway proves insufficient for achieving an ideal solution to this problem. Future challenges will hinge on realizing a co-design between mechanical structures and control algorithms as well as developing nonlinear compensation algorithms that exhibit insensitivity to variations in model parameters and possess robust adaptive capabilities. This focus is essential for ensuring consistent performance throughout the lifecycle of actuators.

4.1.2. Friction/Eddy Current Loss Modeling and Compensation

In addition to thrust ripple, the suspension actuator also exhibits nonlinearities stemming from its mechanical and electrical characteristics, primarily including friction and eddy current damping forces. The crux of this challenge lies in the fact that these forces, particularly friction, display extremely complex dynamic characteristics (e.g., hysteresis, the Stribeck effect, pre-sliding behavior). The intricacy of their mathematical representation and the difficulty associated with parameter identification pose fundamental obstacles that hinder precise force control at low speeds and during micro-movements. Regarding friction, contemporary research has delineated two primary technical pathways: model-driven approaches and data-driven/model-free techniques.

The model-driven approach aims to develop high-fidelity friction models. For example, Wang Limei et al. [145] utilized the LuGre dynamic model, while Xinlong Xu et al. [146] implemented the Prandtl-Ishlinskii (P-I) model which more accurately captures hysteresis phenomena. However, a critical challenge emerges from the stark conflict between a model’s “fidelity” and its “complexity.” As models become more accurate—characterized by an increasing number of parameters—their physical significance becomes less clear; consequently, this complexity complicates offline identification processes while making it challenging to ensure that parameters remain stable under real-world operating conditions (such as temperature fluctuations or wear). Although Liu Zhiguo et al. [147] have employed online identification methods like Recursive Least Squares (RLS) to address time-varying parameters, issues concerning algorithm convergence and robustness persist as significant challenges for practical online application.