Abstract

Torque motors are typically operated within a limited angular range and are widely used in high-precision control applications due to their ability to provide uniform torque throughout the operating region. In this paper, a new torque motor structure is proposed that enhances torque density while maintaining the inherent torque uniformity. The proposed motor employs an optimized stator pole geometry that enables the magnetic flux generated by both the armature and the permanent magnet to contribute more effectively to torque production. To clarify the torque generation mechanism, the flux distributions of the field and armature were analyzed and validated through finite element analysis. Key design parameters were then defined, and an optimal design was performed to maximize the average torque. The performance of the proposed structure was evaluated through a comparative analysis with a conventional torque motor, confirming its superiority. Finally, a prototype of the proposed torque motor was fabricated, and its torque performance was verified through load testing.

1. Introduction

A limited-angle torque motor (LATM) is an electromagnetic actuator that provides restricted angular motion, typically within a range of ±90°, and is widely used as a key actuator in systems requiring precise position control [1,2,3]. LATMs can generate torque proportional to the input current without the need for a gearbox or additional mechanical components. One of their major advantages is that they can maintain a uniform torque characteristic regardless of the rotor speed or position within the limited angular range. They also feature a simple structure, high reliability, and ease of control. Owing to these advantages, LATMs are extensively utilized in high-precision control applications such as precision servo valves and optical positioning systems [4,5,6].

LATMs are generally classified into radial-flux and axial-flux types depending on the direction of the magnetic flux that generates torque. Radial-flux LATMs can be further divided into slotted and slotless structures [3,5,7]. Slotted LATMs offer the advantage of achieving high torque density due to their relatively short air-gap length. However, they suffer from torque ripple caused by cogging torque. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted on optimizing the stator core geometry to improve the torque characteristics of slotted torque motors [8,9].

In contrast, slotless LATMs have a relatively large air-gap, which results in somewhat lower torque density; however, the absence of slots means that cogging torque is theoretically eliminated [2,10]. As a result, slotless LATMs can provide highly uniform torque over the entire operating range. Owing to this advantage, they are widely used in applications where torque uniformity is critical, such as precision servo control and valve actuation. Meanwhile, various studies have been actively conducted to compensate for their lower torque density through structural improvements and high–fill-factor winding techniques [9,11].

Meanwhile, hybrid axial–radial flux LATMs have recently gained attention for achieving high torque density within a constrained volume by utilizing combined magnetic flux paths. However, their complex flux topology makes fabrication and assembly more difficult, and the structure is sensitive to core alignment errors [12,13,14,15,16]. In addition, axial-flux LATMs employing SMC cores and multilayer concentrated windings have been investigated as another approach to enhance torque output. Nevertheless, these designs face practical limitations such as flux loss caused by increased magnetic reluctance and assembly challenges due to the strong magnetic attraction of the permanent magnets [17,18].

Therefore, a review of previous studies shows that it is still difficult to find motor designs that simultaneously achieve uniform torque characteristics and improved torque density. In particular, conventional torque motor structures that inherently generate cogging torque have fundamental limitations in realizing completely flat torque profiles, such as those of slotless configurations, despite extensive research efforts.

In this paper, a new torque motor structure is proposed that simultaneously achieves uniform torque characteristics over the entire operating range and enhanced torque density by utilizing both radial and axial flux paths. First, the structural characteristics of conventional radial- and axial-flux LATMs are analyzed, and based on these observations, a stator pole structure incorporating a hybrid flux path that combines the advantages of both configurations is designed. The torque generation mechanism of the proposed structure is then explained through an analysis of the field and armature flux distributions with respect to the rotor position, and its torque characteristics are verified through finite element analysis (FEA).

The key design parameters of the proposed structure are subsequently defined, and an optimal design is performed using Full Factorial Design (FFD) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to maximize the average torque. In addition, the performance of the proposed design is compared with that of a conventional slotless LATM, which offers inherently uniform torque characteristics. Finally, a prototype of the proposed torque motor is fabricated, and load tests are conducted to validate its torque performance by comparing the measured results with the analytical predictions.

2. Conventional LATM

2.1. Radial Flux Type

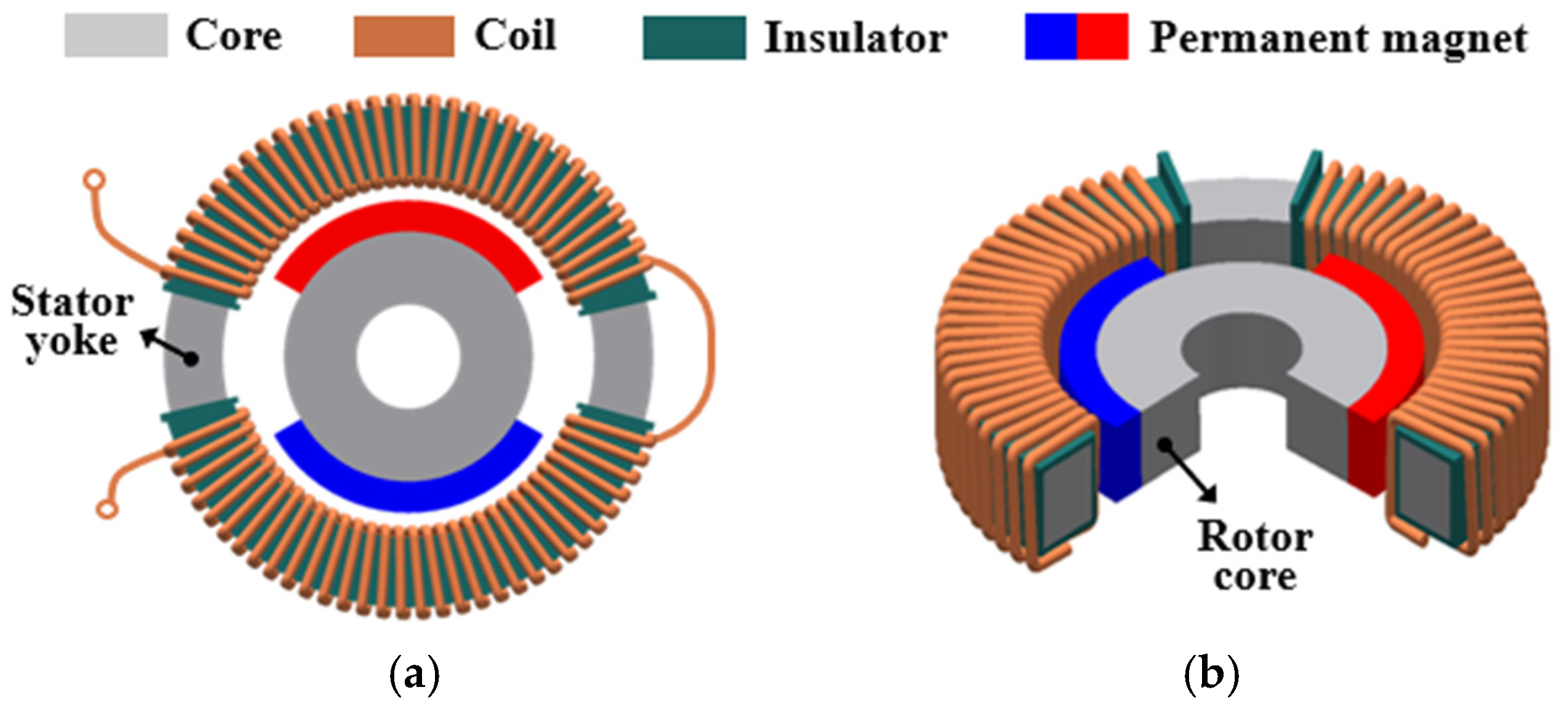

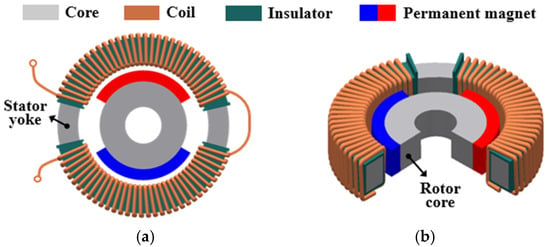

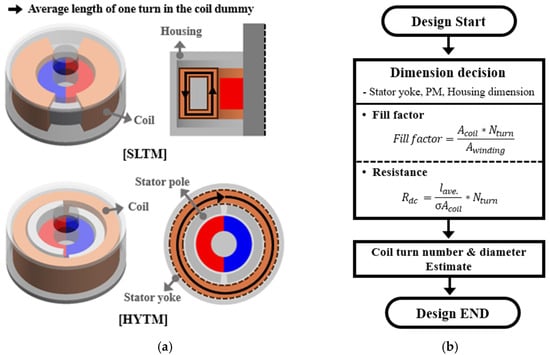

Figure 1 illustrates a representative LATM structure, the slotless type (SLTM). This configuration consists of a two-pole permanent magnet and two coil dummies connected in series. The coils are wound in a toroidal shape around the stator yoke [13,14]. Because the coils are located inside the stator yoke, the effective magnetic air-gap length becomes relatively large, which results in lower torque density compared to slotted torque motors. On the other hand, since the slotless structure maintains a constant air-gap length regard less of the rotor position, cogging torque is theoretically eliminated, allowing the motor to achieve highly uniform torque characteristics over the entire operating range.

Figure 1.

Structure of the SLTM: (a) Top view, and (b) 3D cross-sectional view.

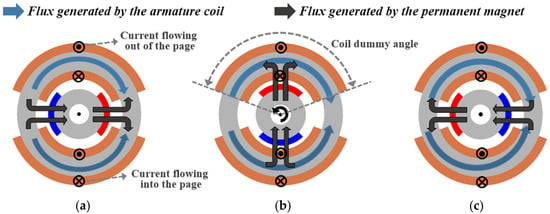

Figure 2 shows the distributions of armature flux and field flux according to the rotor position. In the initial position shown in Figure 2a, the two fluxes are formed in opposite directions, resulting in the minimum flux linkage. As the rotor moves into the coil dummy angle, as illustrated in Figure 2b, the field flux gradually links with the armature windings, increasing the effective magnetic flux. Finally, when the rotor reaches the final position shown in Figure 2c, the two fluxes align in the same direction, and the total flux linkage reaches its maximum value. At this moment, the rotor reaches a torque equilibrium state and no further rotation occurs.

Figure 2.

Flux distribution of the SLTM according to rotor position: (a) Initial position, (b) Intermediate position, and (c) Final position.

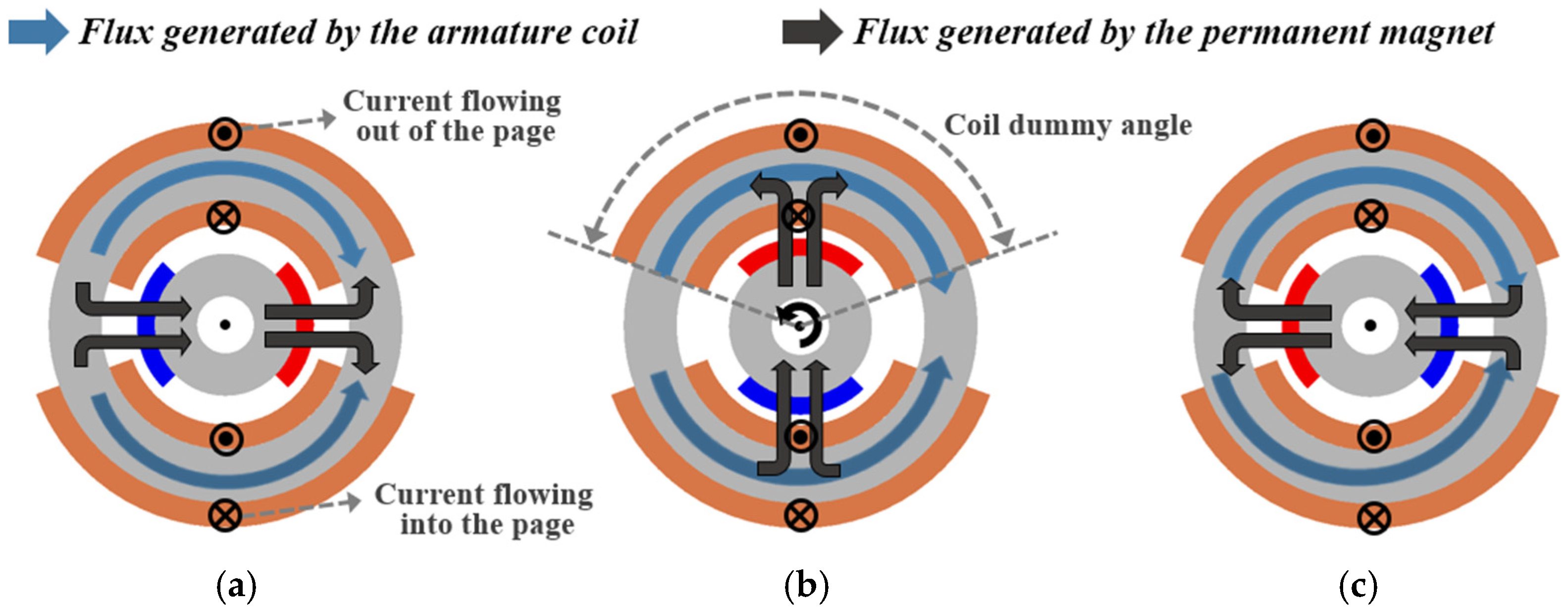

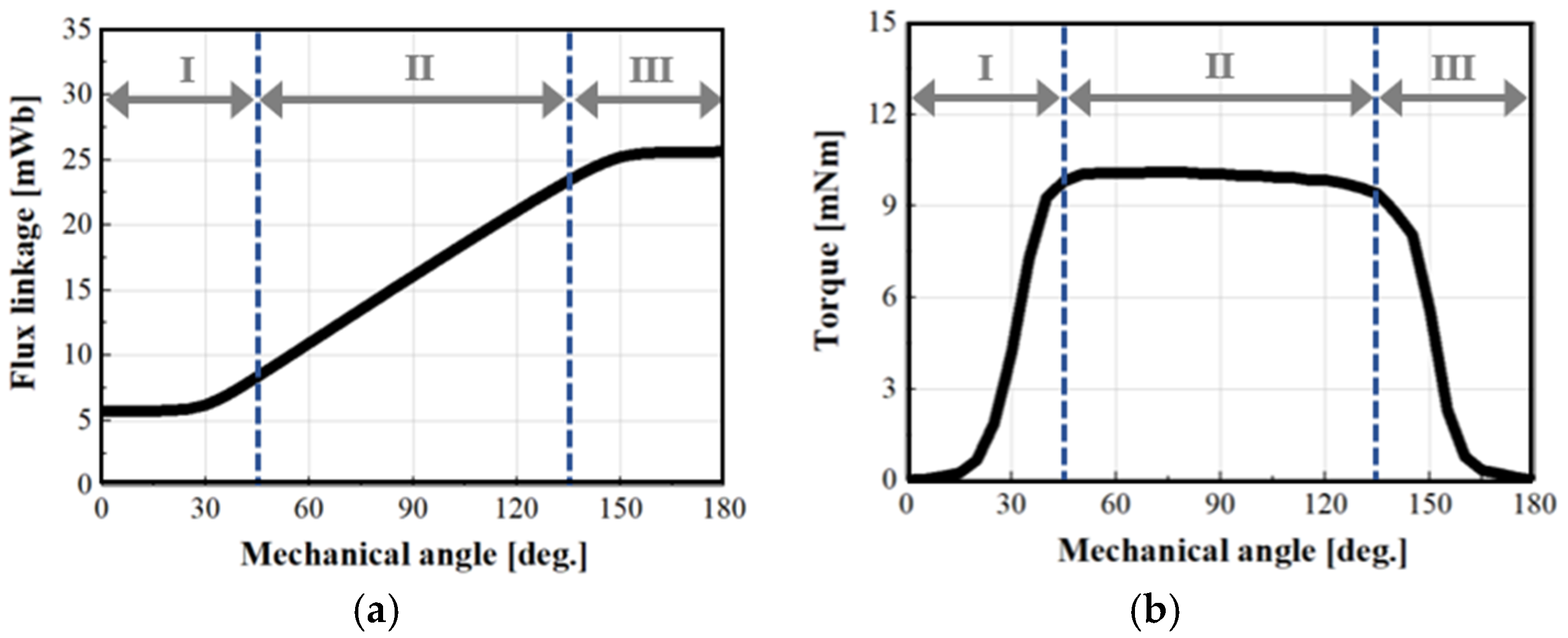

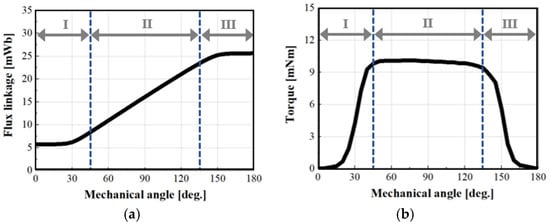

Figure 3 presents the variations in flux linkage and corresponding torque waveform with respect to rotor displacement. As shown in Figure 3a, the flux linkage can be divided into three regions depending on the rotor position. Regions I and III exhibit varying slopes, while Region II maintains a constant slope. Accordingly, the torque shown in Figure 3b increases in Region I, remains constant in Region II, and decreases in Region III.

Figure 3.

Flux linkage and torque characteristics of the SLTM according to rotor position: (a) Flux linkage, and (b) Torque profile.

In current-excited rotating machines, magnetic energy is stored in the magnetic circuit and is converted into mechanical energy. The torque produced is expressed as the variation in magnetic energy with respect to the rotor position, as shown in (1) [19,20,21].

At this time, the mechanical energy is supplied from the magnetic energy, assuming no losses. In addition, in a linear magnetic system, the magnetic energy can be expressed as shown in (2). At this time, the flux linkage is expressed as the product of the current and the inductance.

Therefore, the torque of a rotating machine can be expressed as the product of the current and the variation in inductance or flux linkage, and is summarized in (3).

where is the input current, L is the inductance, is rotation angle, and is the mechanical energy. That is, as shown in Figure 3a, the torque of the motor is determined by the slope of the flux linkage in Region II, and the wider the range over which this slope remains constant, the broader the interval in which a flat torque output can be achieved.

Meanwhile, in the SLTM, the toroidal winding structure inherently results in a relatively long magnetic air-gap, which limits torque enhancement even when high-energy permanent magnets are employed. Therefore, optimizing the coil geometry and air-gap length is essential for improving the performance of the SLTM.

2.2. Axial Flux Type

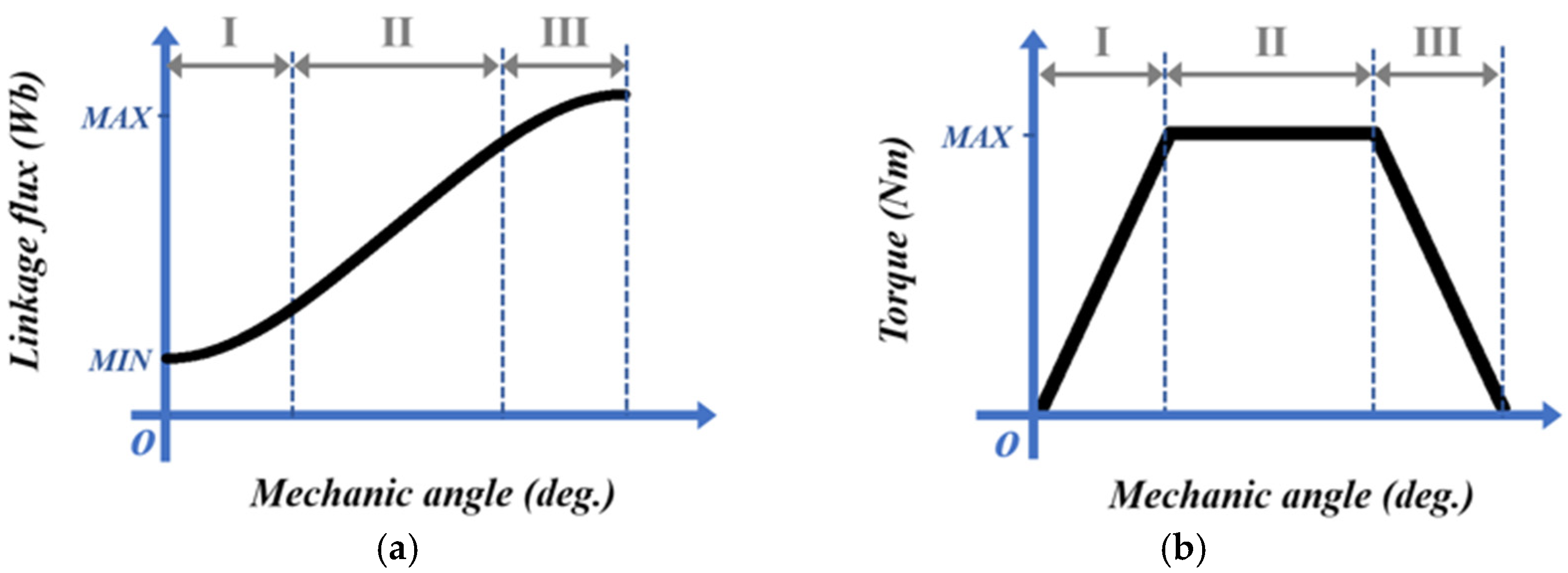

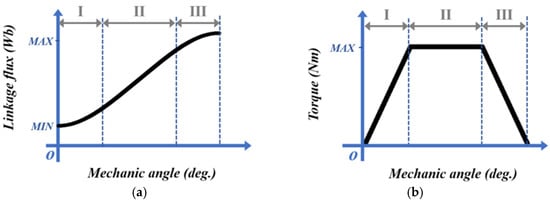

Figure 4 illustrates the basic structure of a voice coil torque motor. It consists of two stator poles protruding from the inner surfaces of the upper and lower stator covers, and a rotor composed of two sector-shaped poles. The cylindrical stator yoke is assembled with the stator covers to form a closed magnetic circuit. The coil is positioned between the stator yoke and the rotor poles and is wound in the theta direction.

Figure 4.

Structure of the VCTM: (a) Overall structure, and (b) 3D cross-sectional view.

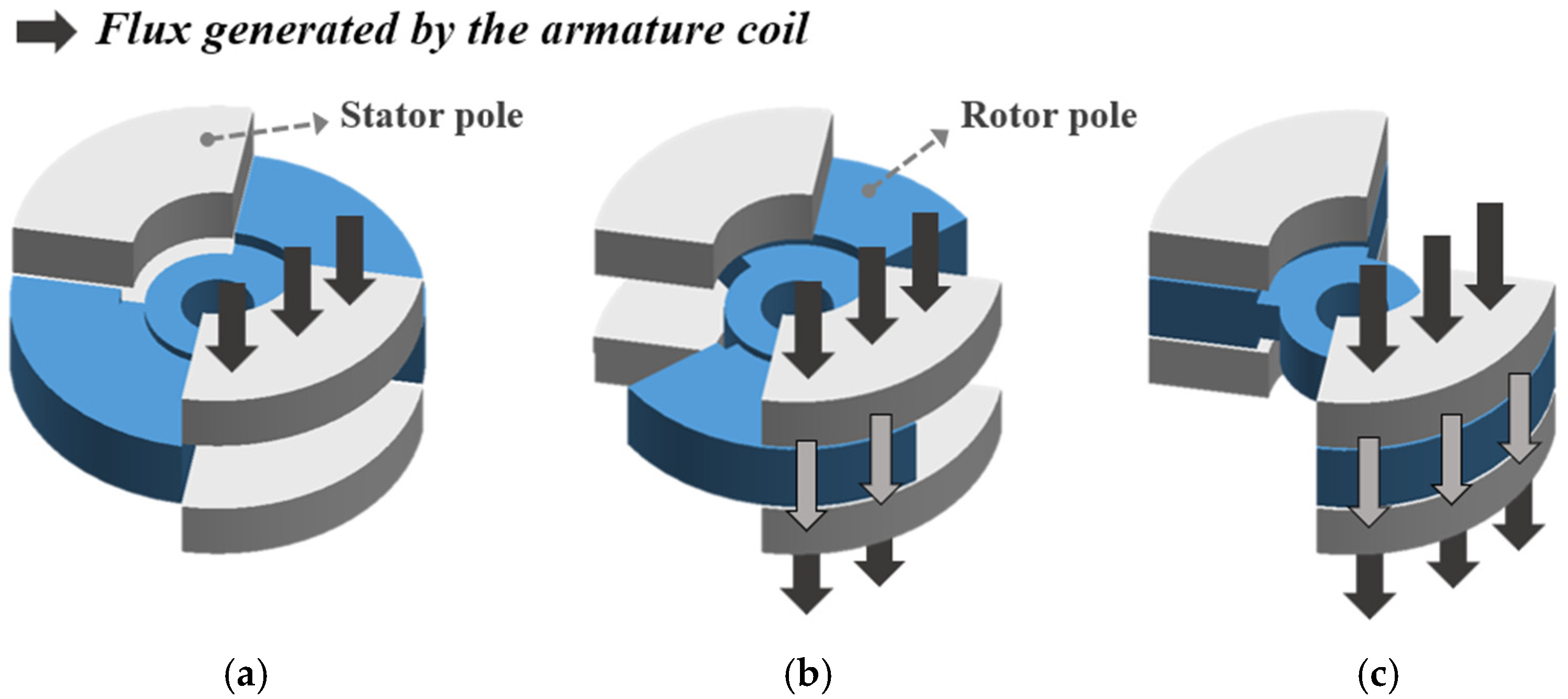

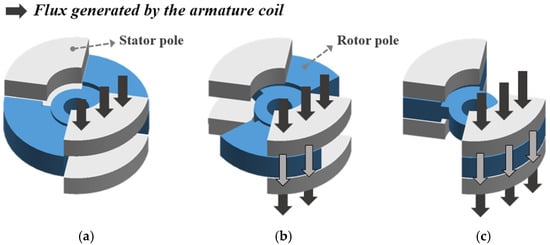

Figure 5 shows the main magnetic flux distributions of the VCTM according to rotor position. In the initial position, the rotor and stator poles do not overlap, resulting in maximum magnetic reluctance and minimal flux linkage. As the rotor begins to overlap with the stator poles, the reluctance decreases and the flux linkage increases. When the poles become fully aligned, the reluctance reaches its minimum and the flux linkage becomes maximal. At this position, the rotor reaches torque equilibrium and stops rotating.

Figure 5.

Flux distribution of the VCTM according to rotor position: (a) Initial position, (b) Intermediate position, and (c) Final position.

Similarly to the SLTM, the magnetic energy stored in the magnetic circuit of the VCTM is converted into mechanical output energy. In a linear system, the two energies are identical. The co-energy can be expressed as shown in (4). In this expression, the magnetomotive force (MMF) can be represented as the product of the coil turns and current, and it can also be expressed as the product of the magnetic reluctance and flux.

Consequently, the torque can be expressed as the product of the current and the variation in magnetic reluctance, as shown in (5).

where is the MMF, is the flux, is the flux linkage, and is the magnetic reluctance. In this manner, the flux linkage and torque characteristics of the VCTM exhibit a similar pattern to those of the SLTM shown in Figure 3, and the torque is determined by the slope of the magnetic reluctance or flux linkage. Furthermore, the wider the range over which this slope remains constant, the broader the interval in which a flat torque output can be achieved.

However, since the VCTM does not use permanent magnets, its torque density may be lower than that of the SLTM. Nonetheless, it offers advantages such as a simpler winding structure, improved manufacturability, and reduced dependence on neodymium permanent magnets, which are difficult to procure.

3. Proposed Hybrid-Type LATM

3.1. Structural Configuration

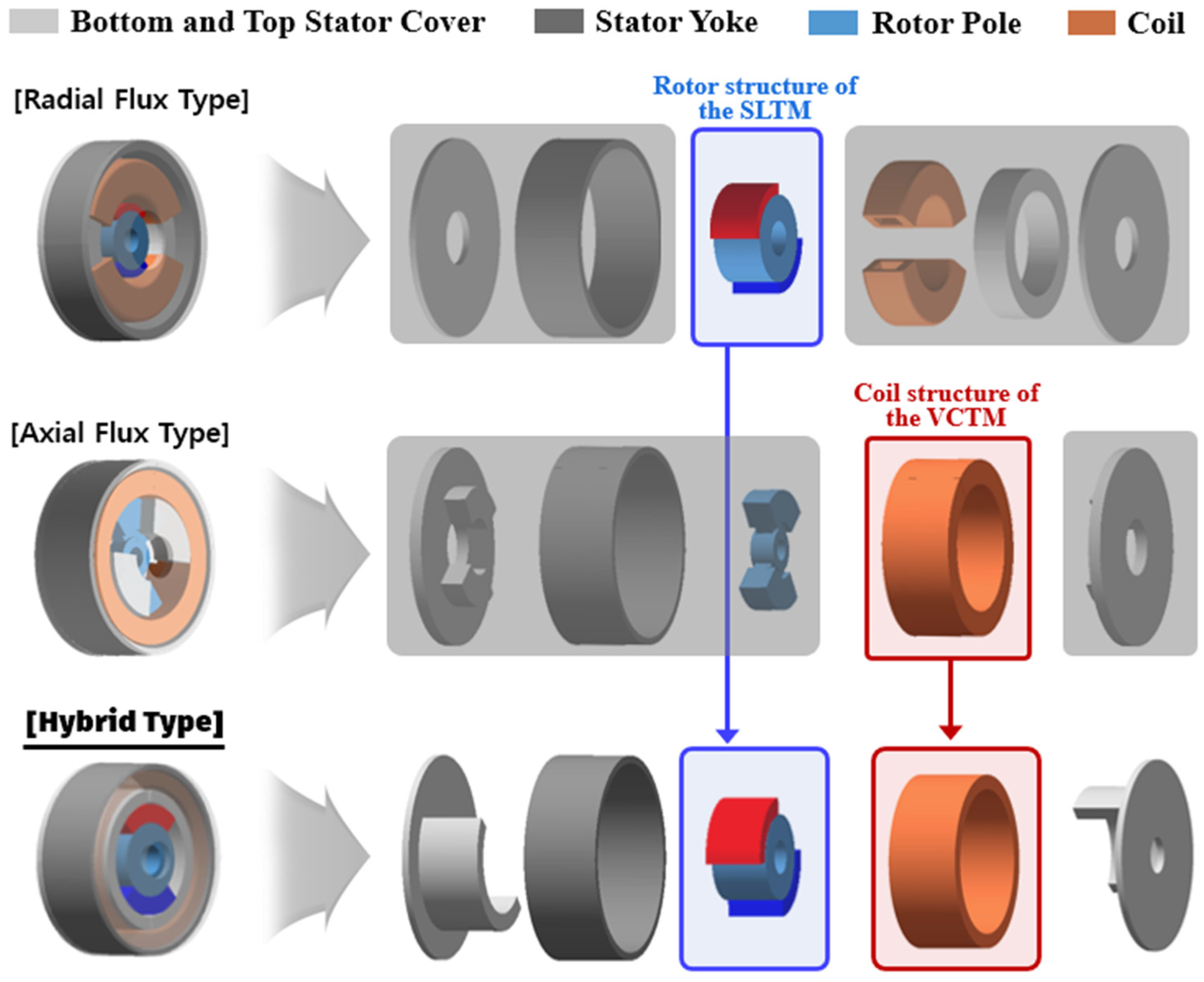

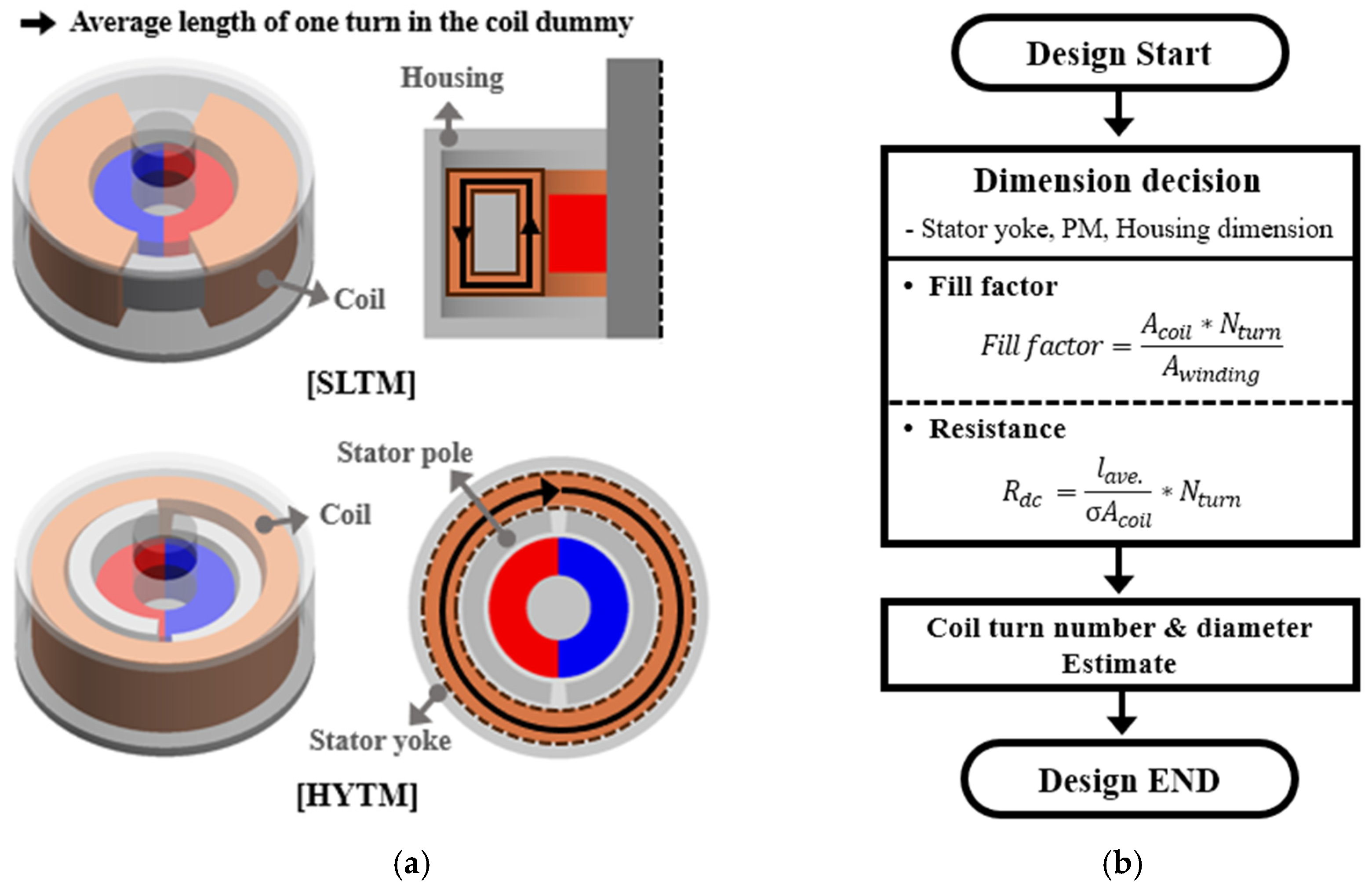

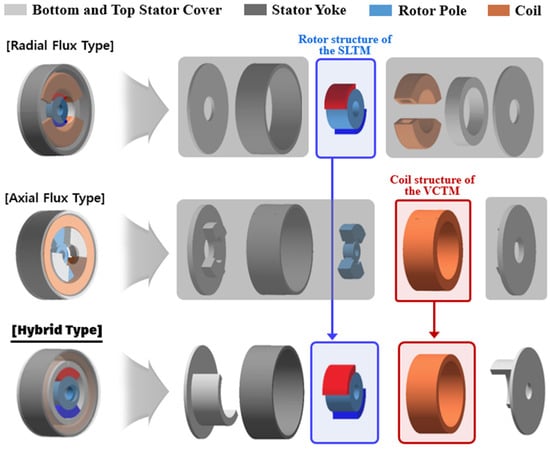

Figure 6 illustrates the structures of the conventional SLTM and VCTM, as well as the hybrid flux torque motor (HYTM) proposed in this study. The proposed HYTM is a hybrid-type LATM that combines the structural advantages of both the SLTM and VCTM. By adopting the permanent magnet configuration of the SLTM, a strong field flux can be secured, while the simple coil configuration of the VCTM enables a high space factor.

Figure 6.

Comparison of structural configuration of the proposed HYTM with conventional types.

Furthermore, a new stator pole structure was designed to facilitate efficient torque generation through the interaction between the axial armature flux and the radial field flux. This structure consists of two semi-cylindrical poles symmetrically protruding from the inner surfaces of the upper and lower stator covers, forming a magnetic flux path through which both the armature and field fluxes circulate via the stator covers and yoke. This flux path plays a key role in torque generation in the HYTM.

3.2. Operational Principle

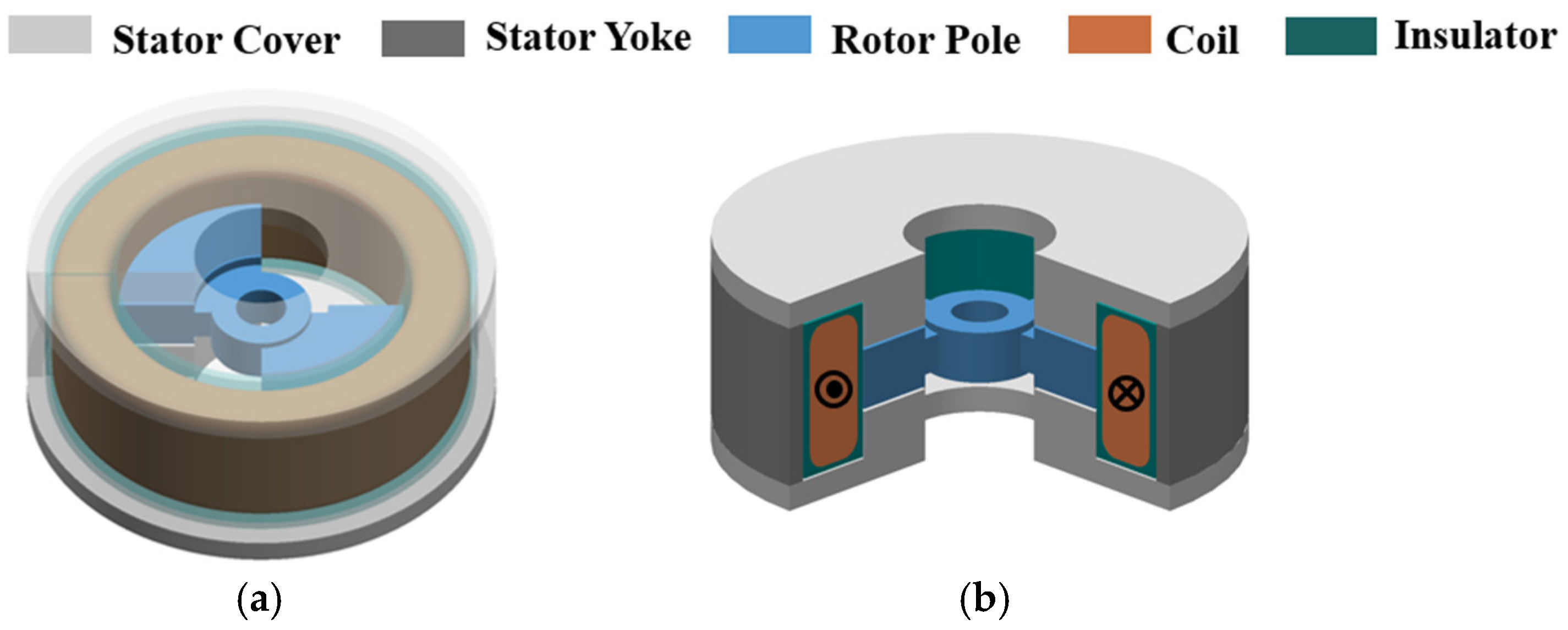

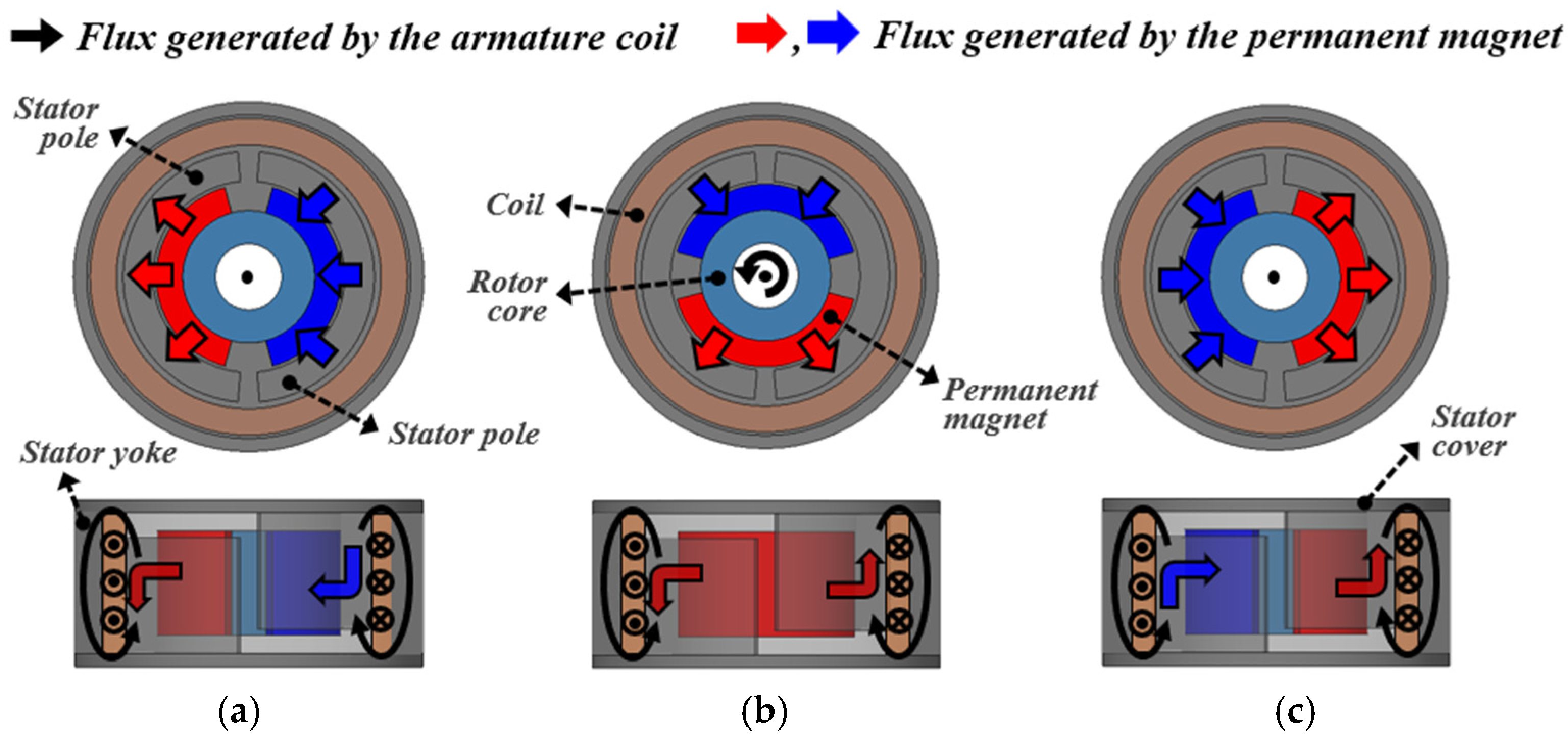

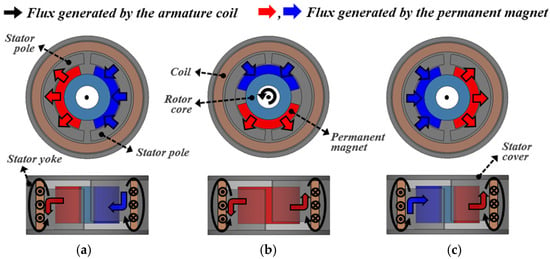

Figure 7 illustrates the distributions of the armature flux and field flux of the proposed HYTM according to the rotor position. In the initial position, as shown in Figure 7a, the magnetic flux generated by the armature coil is formed in the opposite direction to the field flux produced by the permanent magnet. As a result, the two fluxes cancel each other, and the flux linkage reaches its minimum value. As the rotor rotates, as shown in Figure 7b, the permanent magnet gradually overlaps with the opposite stator pole, causing the armature flux and field flux to begin aligning in the same direction. Consequently, the flux linkage increases progressively. Finally, in the position shown in Figure 7c, the armature flux and field flux are fully aligned, and the flux linkage reaches its maximum value. At this point, the rotor reaches a torque equilibrium state, and no additional rotation occurs.

Figure 7.

Flux distribution of the HYTM according to rotor position: (a) Initial position, (b) Intermediate position, and (c) Final position.

Figure 8 illustrates the flux linkage and torque characteristics of the proposed HYTM with respect to the rotor position, obtained through finite element analysis (FEA). As shown in Figure 8a, the flux linkage profile of the HYTM exhibits a shape similar to that of a conventional LATM. The slope of the flux linkage increases in Region I and decreases in Region III, while it remains relatively constant in Region II. The torque characteristics presented in Figure 8b also resemble those of a conventional LATM and, similar to the SLTM, exhibit a flat torque region in Region II.

Figure 8.

FEA result of the flux linkage and torque characteristics of the HYTM according to rotor position: (a) Flux linkage, and (b) Torque profile.

To achieve an ideal flat torque, the slope of the flux linkage must remain nearly constant in Region II. However, due to magnetic saturation and leakage flux in the actual core, maintaining a constant slope becomes difficult. Consequently, the Region II observed in the FEA results of Figure 8 is narrower than the ideal Region II depicted in Figure 3. These findings indicate that the proposed HYTM follows the same torque generation principle as conventional torque motors and is capable of delivering a stable and constant average torque within a limited angular displacement range.

4. Optimal Design

In this section, the performance of the proposed HYTM and the conventional SLTM is compared using finite element analysis. For a fair comparison, both motors share identical outer dimensions and magnet geometry, while their core structures and winding specifications were optimized to maximize average torque within the operating angle. The key design parameters were identified using Full Factorial Design (FFD), and their optimal values were obtained through Response Surface Methodology (RSM). The optimized models were then evaluated to quantitatively compare the performance of the two torque motors [3,4].

4.1. Design Model

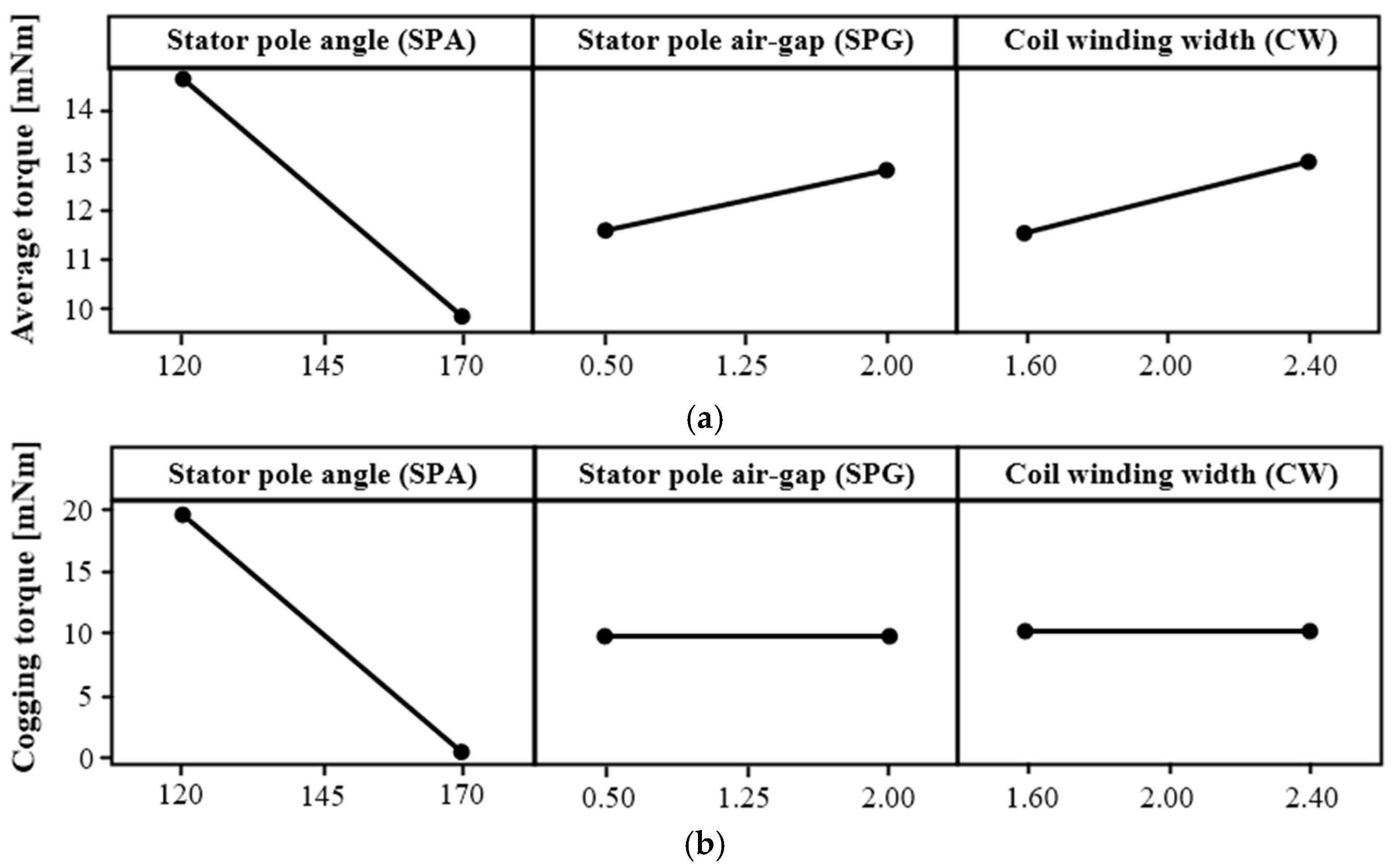

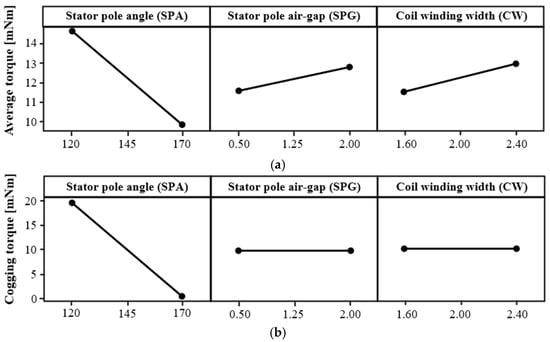

Figure 9a shows the initial configurations of the SLTM and the proposed HYTM. The SLTM consists of two coil-dummy structures, whereas the HYTM is designed with two stator poles.

Figure 9.

SLTM and HYTM Models and Design Procedure: (a) Initial model geometry, and (b) Coil turn number and coil diameter estimation process.

For manufacturability, both motors employ a 2-pole ring-type permanent magnet in the rotor, and the magnets are magnetized using a parallel magnetization scheme. Figure 9b illustrates the procedure used to determine the number of turns and coil diameter. Once the torque motor geometry is defined, the coil-winding area and the single-turn length can be obtained. With these two values, the coil diameter and the number of turns required to meet the target resistance and fill factor can then be determined.

In this study, the coil fill factor for both torque motors was set to approximately 25% considering manufacturability, and the winding resistance was fixed at 16 Ω based on the system power requirements. In addition, the torque comparison was performed by evaluating the average torque within the ±30° interval centered at the angle of maximum torque. The design specifications of the two torque motors are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Common geometric dimensions of the SLTM and HYTM.

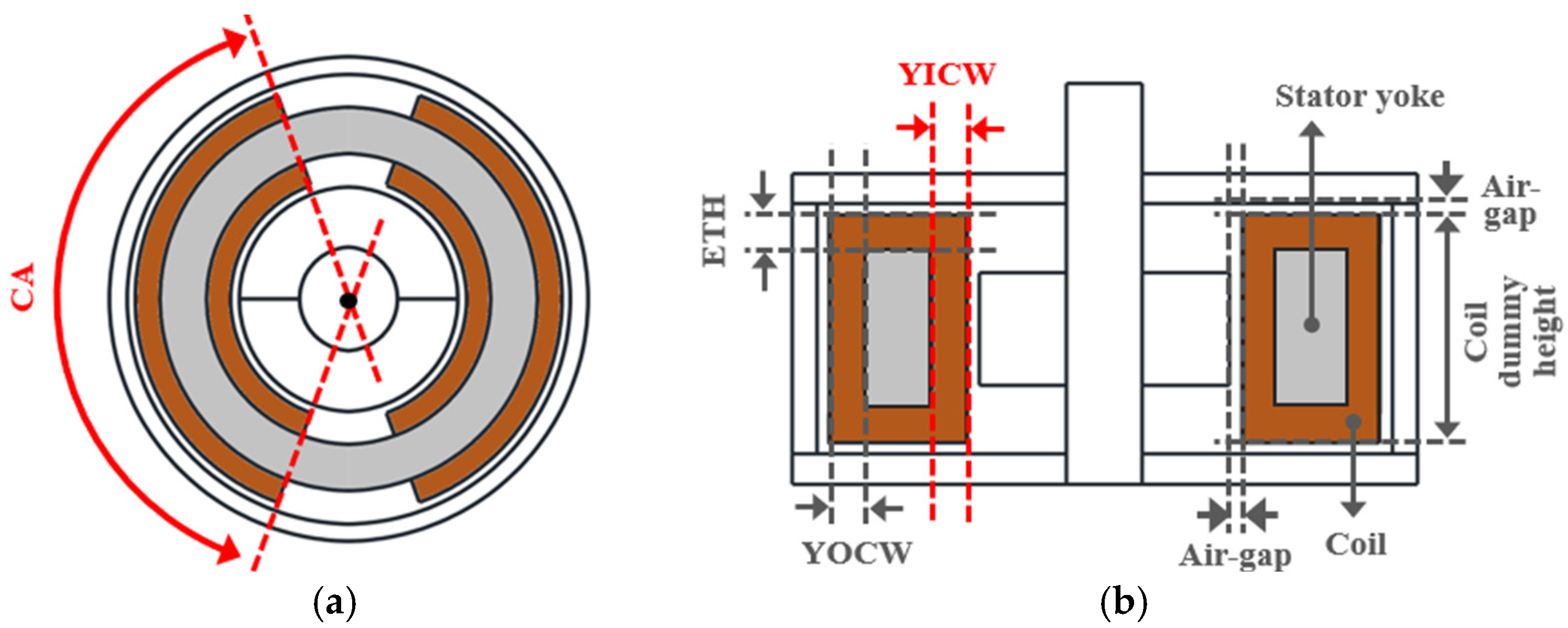

4.2. Design Factor

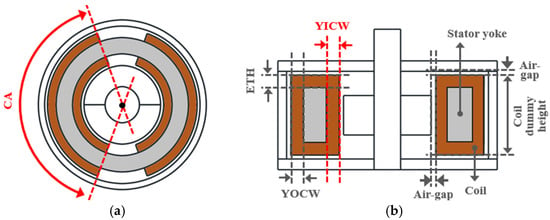

Figure 10 shows the major design parameters of the SLTM. Among these, the Coil Dummy Angle (CA) and the Yoke Inner Coil Dummy Width (YICW) were selected as the design variables. In this configuration, YICW, the Yoke Outer Coil Dummy Width (YOCW), and the End-Turn Height (ETH) were assumed to have identical values. In addition, the outer diameter, height, and thickness of the enclosure, as well as the outer diameter and height of the permanent magnet, were kept constant. The spacing between each component was fixed at 0.5 mm, and the coil-dummy height was maintained at 8.2 mm. Consequently, the thickness and height of the stator yoke are determined by the value of YICW. The ranges of the major design variables for the SLTM are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 10.

SLTM design parameters: (a) Top view, and (b) Cross-sectional view.

Table 2.

Ranges of the major design variables for the SLTM.

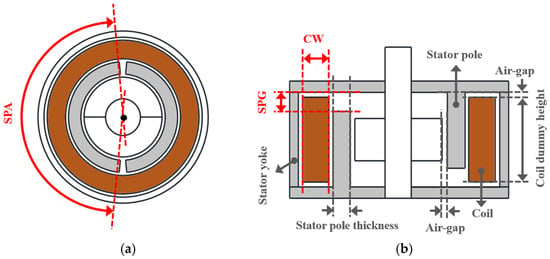

Figure 11 shows the major design parameters of the HYTM. In this model, the Stator Pole Angle (SPA), Stator Pole Air-Gap (SPAG), and Coil Width (CW) were selected as the design variables. In this configuration, the thickness and height of the stator yoke are determined by the values of CW and SPAG, and the thickness of the stator yoke was assumed to be half of the stator pole thickness. As in the SLTM, the spacing between each component was fixed at 0.5 mm, and the coil-dummy height was maintained at 8.2 mm. The ranges of the major design variables for the HYTM are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 11.

HYTM design parameters: (a) Top view, and (b) Cross-sectional view.

Table 3.

Ranges of the major design variables for the HYTM.

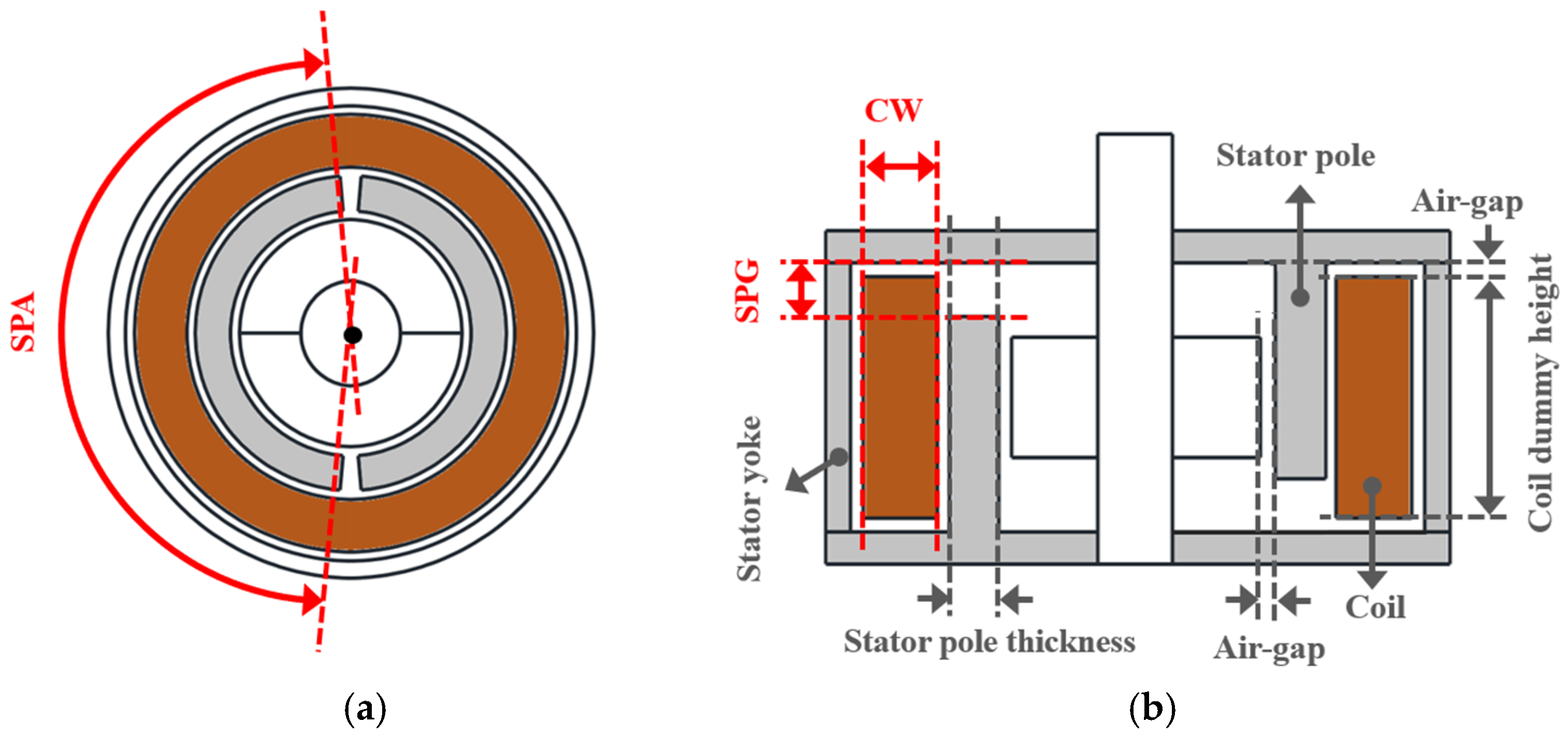

4.3. Full Factorial Design

Since the magnetic reluctance of the HYTM varies with rotor position depending on the SPA, cogging torque is inevitably generated. Therefore, a Full Factorial Design (FFD) was applied to the three design variables listed in Table 3 to identify the factors that most significantly affect both the average torque and cogging torque [17].

As shown in Figure 12a, the average torque increases as the SPA decreases, indicating that SPA is the most influential parameter for torque performance. SPG and CW also exhibit a gradual increase in average torque as their values increase. When SPG increases, flux leakage toward the stator cover is reduced, resulting in an increase in the overall flux linkage and consequently improving torque. However, if SPG exceeds a certain level, additional changes no longer produce meaningful variations in the total flux and may even negatively affect the cogging torque. Likewise, increasing CW initially enhances torque due to the higher number of turns, but if CW becomes excessively large, the stator pole and yoke thicknesses become too thin, and magnetic saturation can occur, leading to a reduction in torque.

Figure 12.

Result of the FFD for the HYTM: (a) Average torque, and (b) Peak value of cogging torque.

In contrast, Figure 12b shows that cogging torque is relatively insensitive to SPG and CW, but decreases noticeably as SPA increases. This confirms that maximizing average torque and minimizing cogging torque exhibit opposite tendencies with respect to SPA, demonstrating a clear trade-off relationship. Accordingly, in the subsequent RSM stage, the optimal design was carried out to maximize the average torque of the HYTM while applying a constraint to ensure that the cogging torque remained at a level that does not affect system operation.

4.4. Condition of Optimization

The objective function for both torque motors was defined as maximizing the average torque within the ±30° interval centered at the position where the maximum torque occurs.

In addition, for the HYTM, a constraint was imposed to ensure that the peak cogging torque remains below 10% of the average torque. In contrast, no such constraint was applied to the SLTM, as its structure inherently prevents cogging torque from occurring [22].

Peak value of cogging torque = with 10% of the average torque (@HYTM)

Finally, the design conditions for both torque motors were set identical to those used in the FFD, with a coil resistance of 16 Ω and a fill factor of 25%. The FEA was conducted using a current-source approach, and a DC current of 1.0 A was applied.

DC resistance: 16.0 (ohm)

Full factor: 25.0 (%)

DC current: 1.0 (A)

4.5. Response Surface Methodology

To construct an objective-function-based model and ensure appropriate response characteristics, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was employed. The experimental design points were generated using a Central Composite Design (CCD), and the ranges of the design variables were determined based on the FFD results. In the RSM stage, the design variables for both models were defined to be identical to those used in the FFD in terms of both variable selection and range.

SLTM: Coil dummy angle (CA), Yoke inner coil dummy width (YICW)

HYTM: Stator pole angle (SPA), Stator pole air-gap (SPAG), Coil dummy width (CW)

HYTM: Stator pole angle (SPA), Stator pole air-gap (SPAG), Coil dummy width (CW)

Based on the CCD results for the SLTM and HYTM, a second-order polynomial response surface model for the average torque was developed. The resulting regression equations include the linear, quadratic, and interaction terms of the design variables.

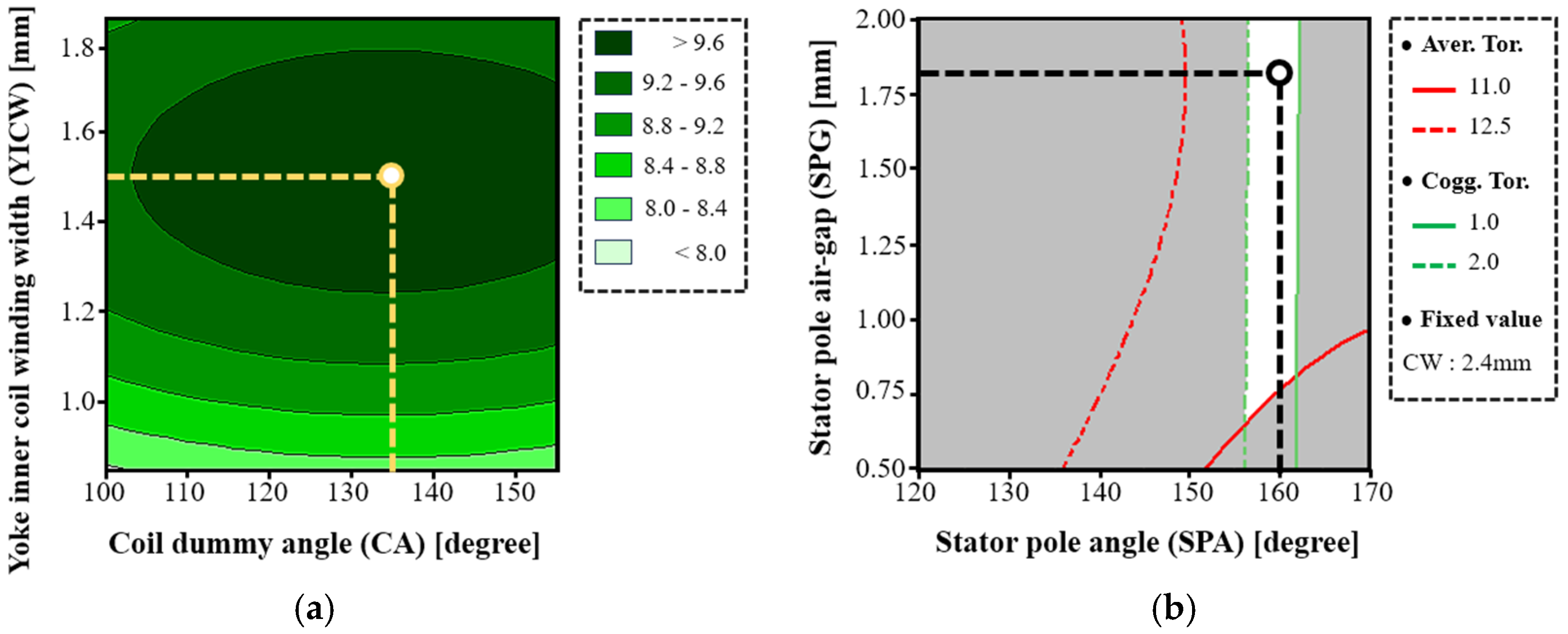

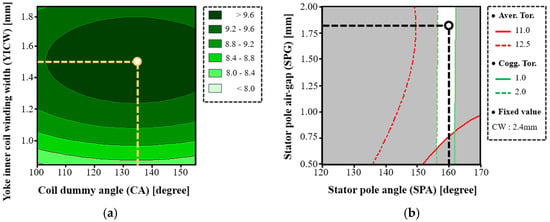

where A1 is CA and B1 is YICW. A2 is SPA, B2 is SPAG, and C2 is CW. Figure 13 illustrates the response trends of the average torque with respect to variations in the design parameters.

Figure 13.

Result of the RSM: (a) SLTM, and (b) HYTM.

As shown in Figure 13a, the SLTM exhibits a distinct optimal point within the ranges of CA and YICW where the average torque reaches its maximum.

In contrast, Figure 13b presents the average torque trend of the HYTM with respect to SPA and SPG, with CW fixed at 2.4 mm. Although increasing CW can further enhance the average torque, it also leads to an excessively thin stator yoke. Therefore, considering manufacturability, CW was fixed at 2.4 mm in the final model. As shown in Figure 13b, the feasible design region of the HYTM becomes narrower due to the cogging-torque constraint. The optimal geometric parameters for both torque motors are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Design dimensions of the SLTM and HYTM obtained through the RSM.

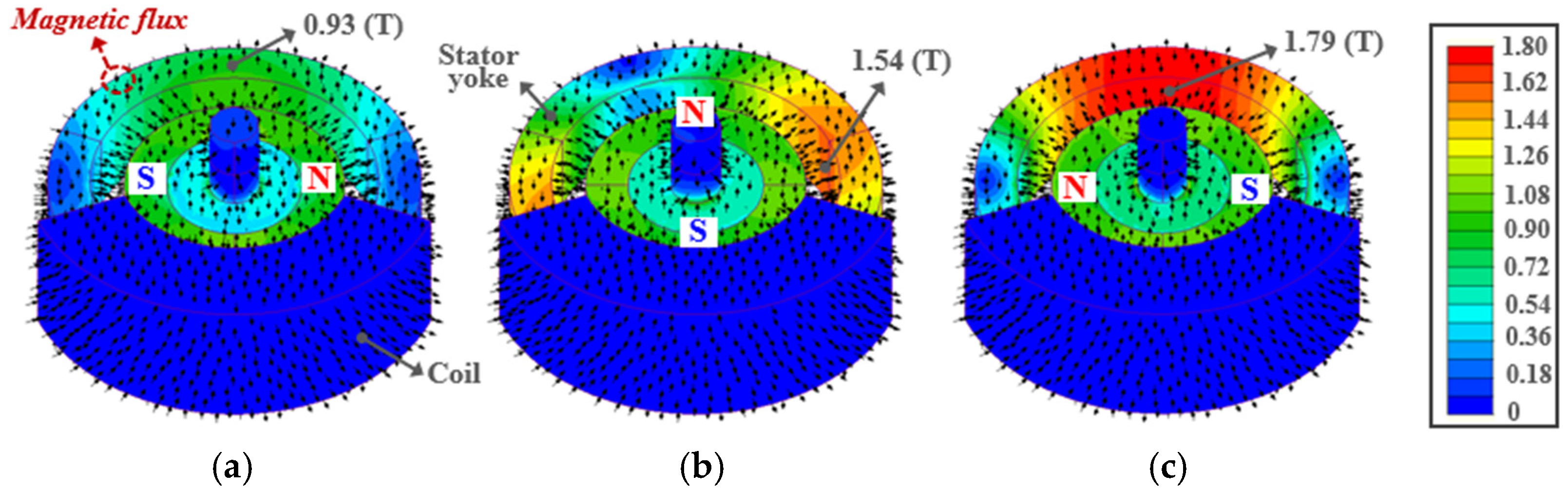

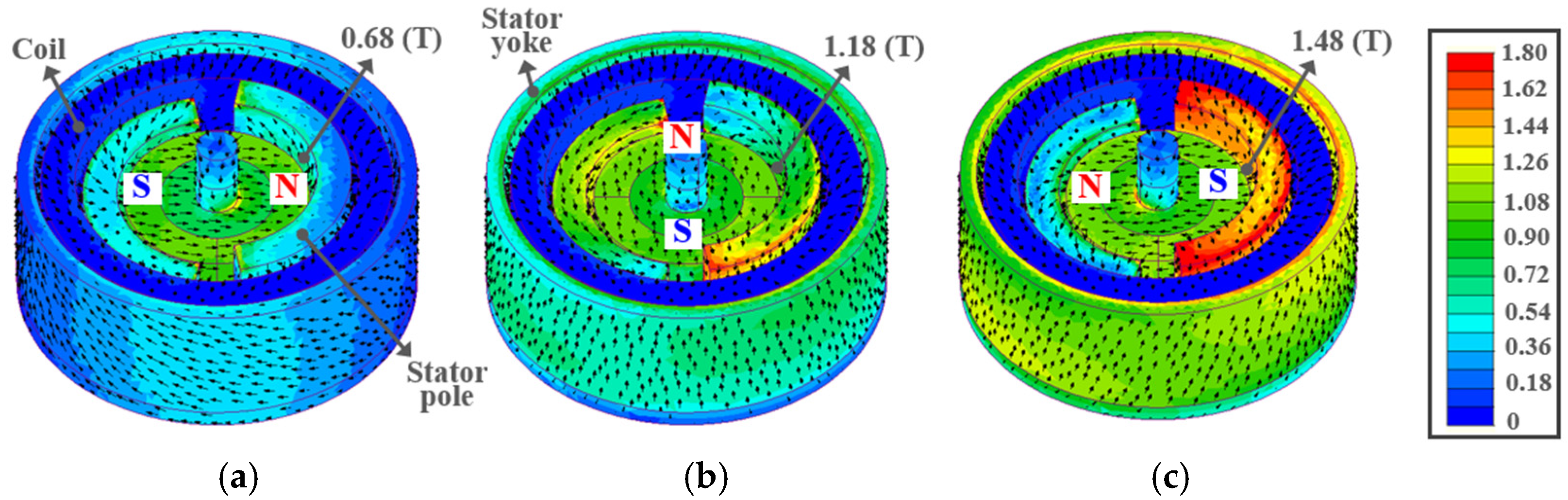

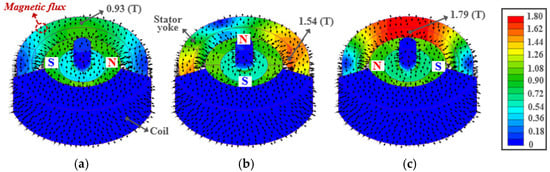

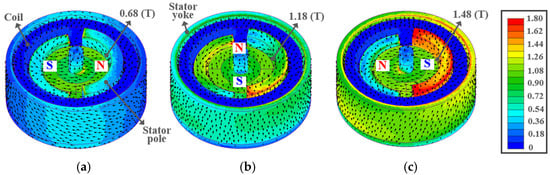

Figure 14 and Figure 15 show the magnetic flux distributions of the SLTM and HYTM, respectively, as a variation in rotor position obtained through finite element analysis.

Figure 14.

Magnetic flux distributions of the SLTM obtained from finite element analysis: (a) Initial position, (b) Intermediate position, (c) Final position.

Figure 15.

Magnetic flux distributions of the HYTM obtained from finite element analysis: (a) Initial position, (b) Intermediate position, (c) Final position.

For the SLTM shown in Figure 14, the upper coil was omitted to clearly illustrate the flux path, while for the HYTM shown in Figure 15, the upper stator cover was removed to visualize the flux distribution.

As observed in Figure 14 and Figure 15, the magnetic flux density in both motors is lowest at the initial rotor position because the armature flux and field flux oppose each other, resulting in a reduced flux level in the stator yoke and pole. As the rotor angle increases, the magnetic flux density on the stator core gradually increases, and it reaches its maximum at the final position where the armature and field fluxes become nearly balanced. This trend in flux variation is consistent with the characteristics previously described in Figure 2 and Figure 7.

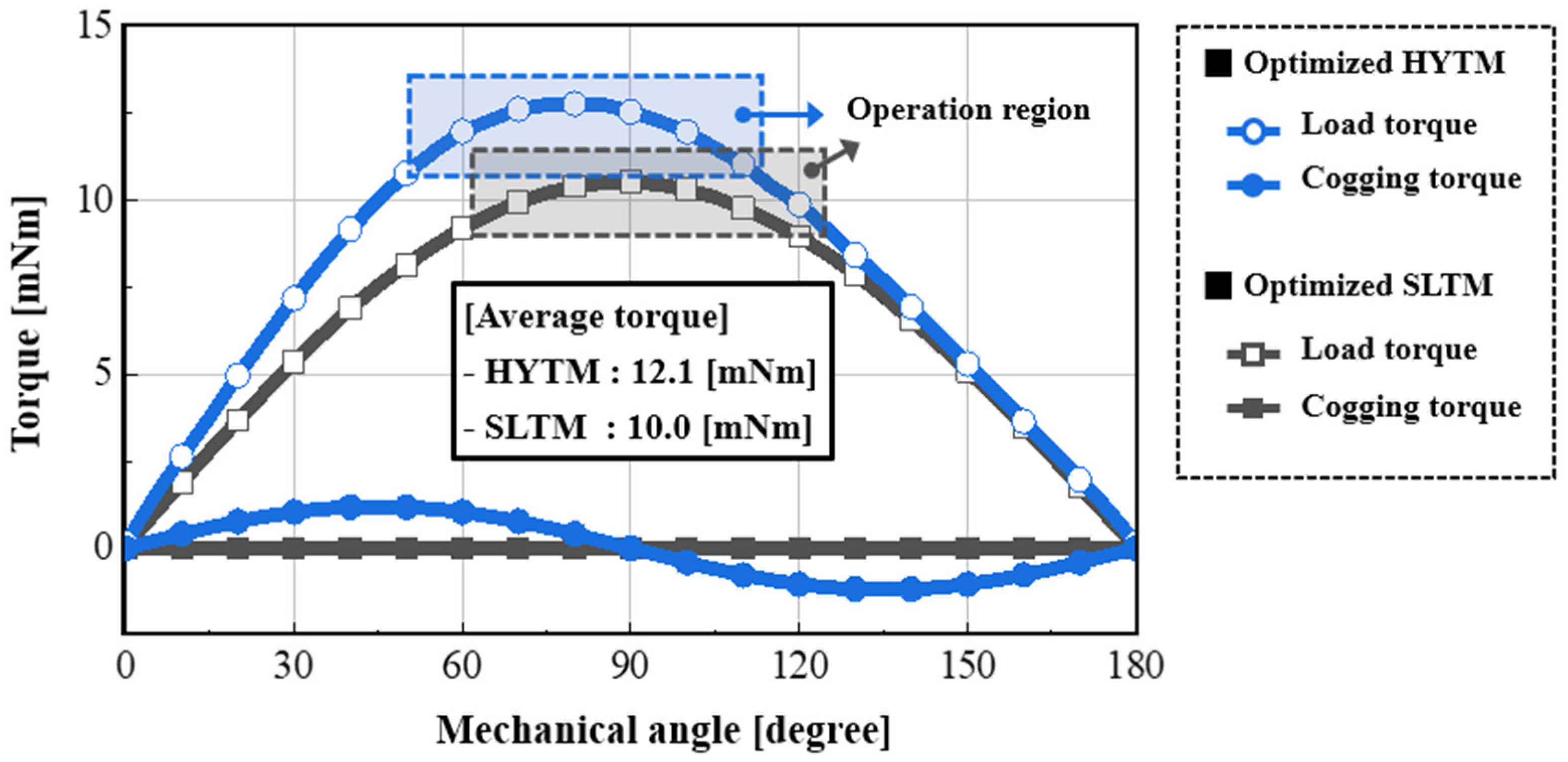

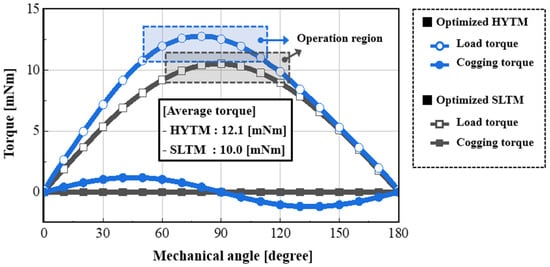

Figure 16 compares the torque and cogging torque waveforms of the two optimized models. As summarized in Table 5, the proposed HYTM achieves approximately 21% higher average torque than the SLTM. The comparison was conducted under identical fill-factor conditions; however, because the HYTM features a simpler coil structure, it has the potential to achieve a higher fill factor than the SLTM, providing additional room for further performance improvement. Although a small amount of cogging torque is generated in the HYTM due to its structural characteristics, its magnitude is very small relative to the average torque and thus has a negligible effect on the overall torque behavior.

Figure 16.

Torque and cogging torque waveform comparison of optimized SLTM and HYTM.

Table 5.

Average torque and cogging torque peak for the Optimized SLTM and HYTM.

5. Prototype Manufacturing and Test

5.1. Prototype Configuration

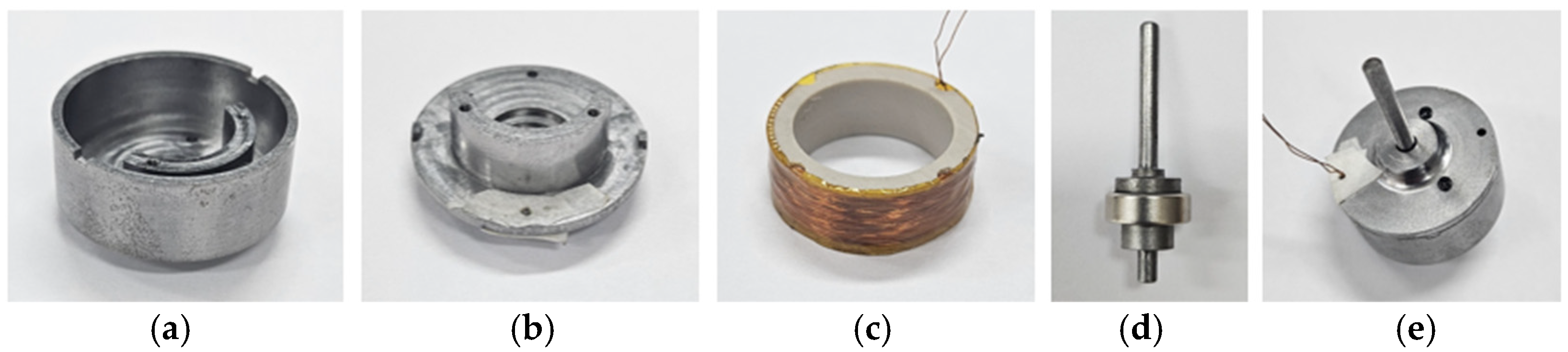

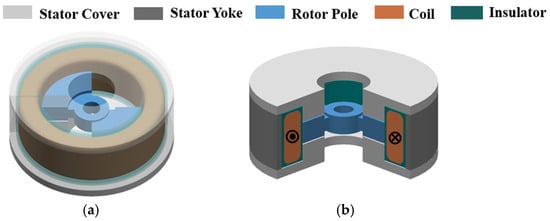

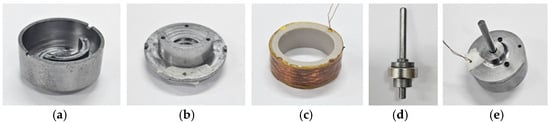

Figure 17 shows the main components and the assembled prototype of the proposed Hybrid Torque Motor (HYTM). As illustrated in Figure 15a, the bottom stator cover is fabricated in a cylindrical shape with an inner curved pole of 160°. The top stator cover, shown in Figure 17b, has a symmetric curved structure of the same angle, forming a closed magnetic path together with the bottom cover. Figure 17c presents the coil dummy wound on a thin cylindrical insulator, which is assembled between the stator pole and yoke of the cover. Additionally, as shown in Figure 17d, the rotor consists of a shaft with a ring-shaped permanent magnet mounted on it, where the stepped structure of the shaft ensures precise alignment of the magnet at the center of the stator poles. Finally, all components are assembled into the completed prototype, as illustrated in Figure 17e.

Figure 17.

Components and prototype of the proposed HYTM: (a) Bottom stator cover, (b) Top stator cover, (c) Coil wound on cylindrical insulator, (d) Rotor Assy, and (e) Assembled HYTM prototype.

5.2. Prototype Test

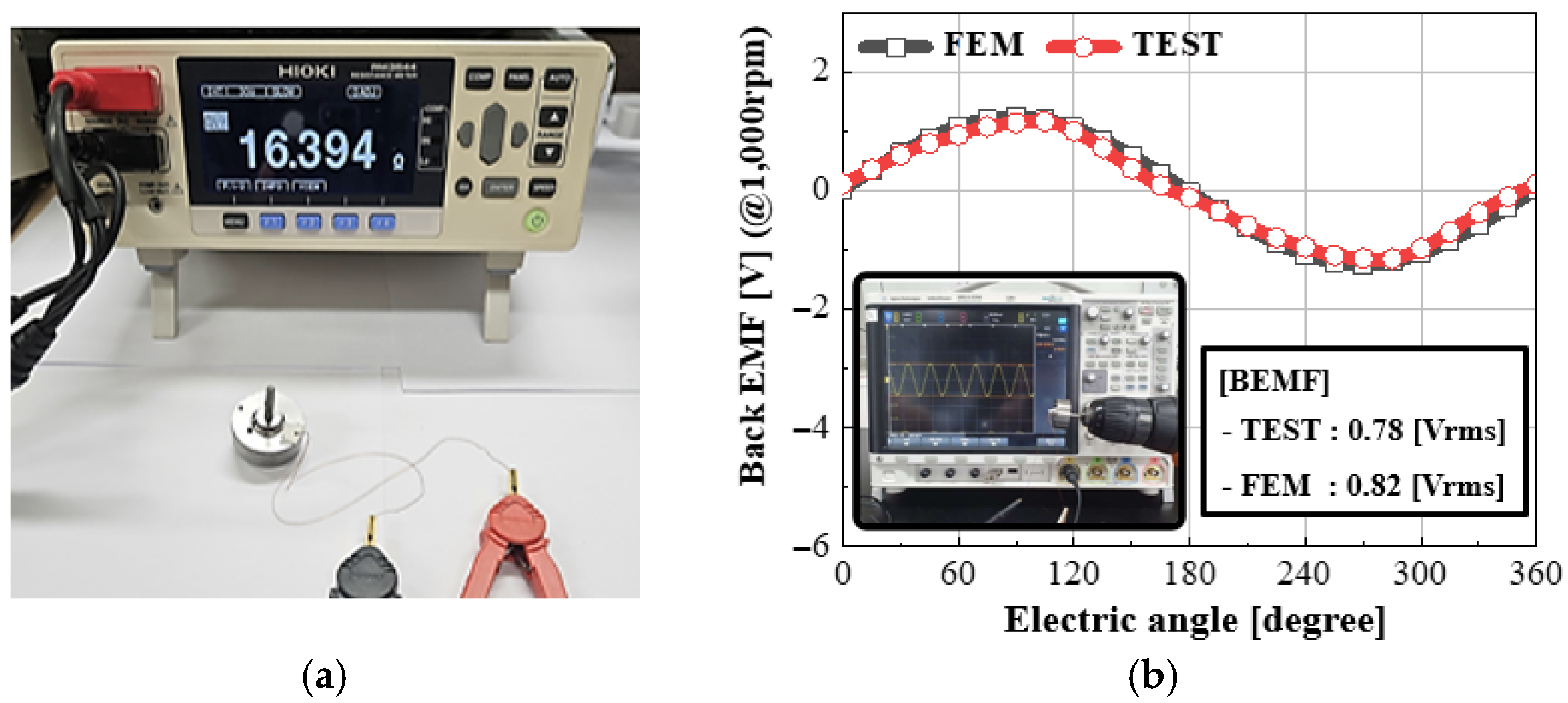

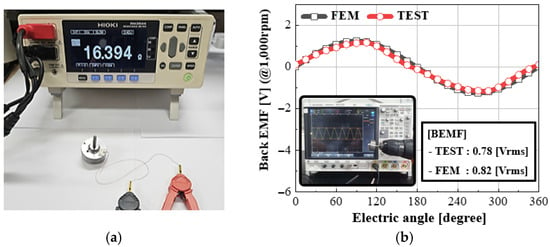

To verify the design validity of the prototype, the winding resistance and back electromotive force (back-EMF) were measured, as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Measurement of winding resistance and back-EMF of the HYTM prototype: (a) Resistance, and (b) back-EMF.

As presented in Figure 18a, the measured winding resistance of the prototype was approximately 16.4 Ω, which shows a deviation of about 2.4% from the designed value of 16.0 Ω calculated using the procedure described in Figure 9.

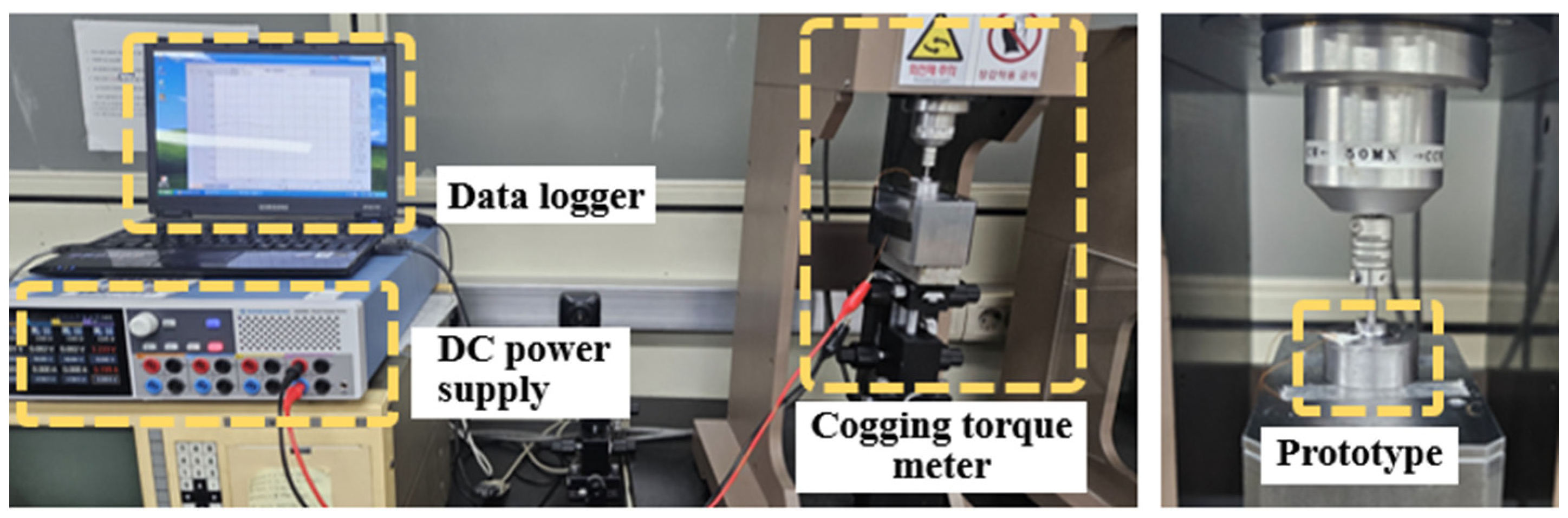

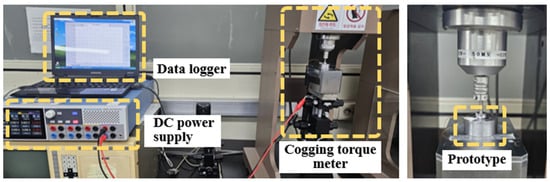

Considering that the measured value includes the resistance of the lead wires, this confirms the validity of the coil specification estimation method. Figure 18b shows the back-EMF measured at the lead terminals when the prototype was driven by an external motor. The effective value of the induced voltage measured at 1000 rpm was approximately 0.78 V, which shows good agreement with the simulation result of 0.82 V, exhibiting an error of about 5%. The load torque characteristics of the prototype were evaluated using the measurement setup shown in Figure 19. As illustrated in Figure 19 a compact torque meter was employed to measure the torque of the prototype while applying current under a low-speed condition of 1 rpm across a full 360° rotation.

Figure 19.

Experimental setup for torque test.

The DC power supply was configured to maintain a constant current, which was increased stepwise from 0.4 A to 1.0 A in 0.2 A increments. Between each test cycle, sufficient cooling time was provided to dissipate the heat generated in the coil before proceeding to the next measurement.

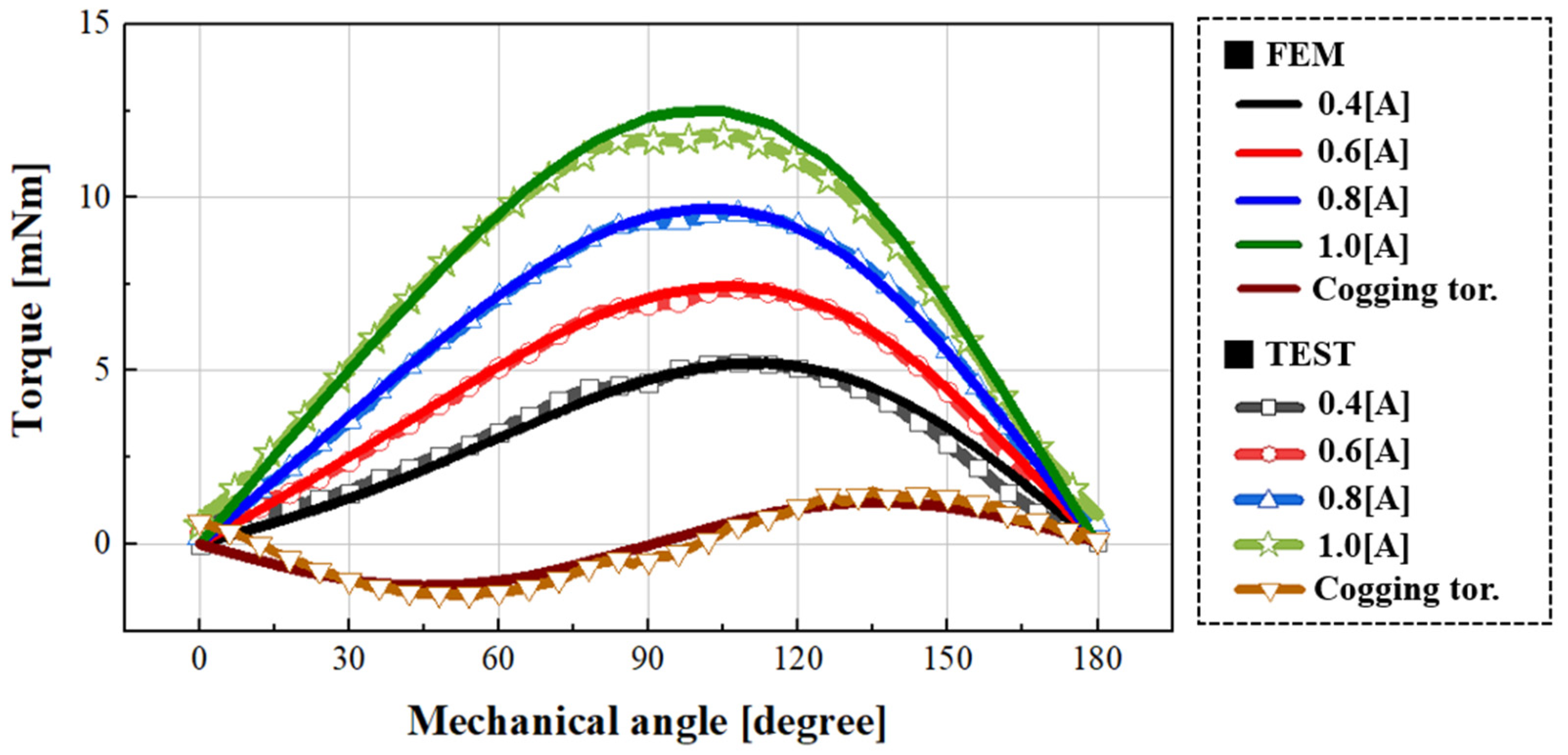

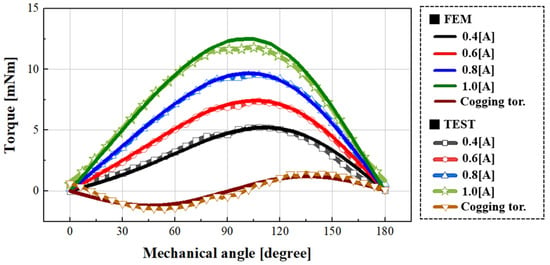

Figure 20 presents the measured cogging torque and load torque waveforms at different current levels. For cogging torque, the peak-to-peak values from simulation and measurement were 2.99 mNm and 2.42 mNm, respectively, corresponding to an error of approximately 20%. Since the cogging torque of a small-sized torque motor is inherently low, such deviation is considered reasonable given mechanical factors such as shaft misalignment and bearing friction [23,24].

Figure 20.

Comparison of FEA and experimental torque waveforms under different current conditions.

Regarding the load torque results, the measured and simulated average torques at 1.0 A were 11.28 mNm and 11.77 mNm, respectively, showing a small discrepancy of about 4.3%. Similar agreement between simulation and experiment was observed at other current levels, and the detailed values are summarized in Table 6. Additionally, as the applied current increased from 0.4 A to 1.0 A, the position of maximum torque was observed to shift gradually. This occurs because, at low current levels, the cogging torque has a relatively greater influence on the total torque waveform, whereas at higher currents, the load torque magnitude increases and the relative impact of cogging torque diminishes. Consequently, as long as the stator pole and yoke remain unsaturated, the position of maximum torque tends to converge toward a specific point as the current increases.

Table 6.

FEA and experimental results over a 60° operating range.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposed a hybrid limited-angle torque motor (HYTM) that enhances torque density by simultaneously utilizing radial and axial magnetic flux. The proposed HYTM adopts a pair of symmetrically formed semi-cylindrical poles on the inner surfaces of the stator covers, enabling effective use of both radial and axial flux paths.

Using the Full Factorial Design (FFD) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM), key design parameters were optimized to maximize the average torque while minimizing cogging torque. Finite element analysis (FEA) results showed that the optimized HYTM achieved approximately 21% higher average torque compared to the conventional slotless torque motor (SLTM), while maintaining the cogging torque below 10% of the average torque, thus ensuring a stable torque profile.

Experimental validation also demonstrated high agreement with the analytical results, with measured winding resistance, back electromotive force (back-EMF), and torque values all showing less than 5% deviation from the simulations. The prototype employing a ring-shaped permanent magnet exhibited an arc-dome torque waveform, whereas the segmented permanent magnet configuration, as confirmed through simulation, provided a much flatter torque characteristic.

In conclusion, the proposed HYTM achieves both high torque density and excellent torque uniformity when a segmented permanent magnet structure is applied. Owing to its simple structure and high manufacturability, it is considered suitable for precision limited-angle actuator applications. Future work will involve the practical implementation of the segmented magnet structure and further optimization of the stator pole segmentation and magnet arrangement to enhance the overall performance of the HYTM.

Author Contributions

Methodology and investigation, H.-Y.L.; validation, S.-O.K.; visualization, H.-Y.L.; supervision, H.-Y.L. and M.-R.P.; writing and review and editing, H.-Y.L. and M.-R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE), Republic of Korea, under the project titled “Development of design and demonstration technology for 3MW POD system” (RS-2023-00250833).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to IL Shin Motor Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. An overview on developments and research of limited-angle torque motor. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2023, 38, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Kassem, A.E.M.; Hassan, M.A. Prospects for the use of limited-angle torque motors in renewable energy systems. Int. J. Energy Appl. Technol. 2025, 12, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z. Investigation on flat torque-angle characteristic of torque motor for 2D valve systems. IET Power Electron. 2023, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, Q.; Sun, J.; Yan, B.; Hu, Z.; Sun, W. Multi-Objective Optimization of Torque Motor Structural Parameters in Direct-Drive Valves Based on Genetic Algorithm. Actuators 2025, 14, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygın, A.; Olgun, İ. Four-Pole Limited-Angle Toroidal Motor Magnetic Design. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 809–818. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J. Moment-Frequency Characteristics of Limited-Angle Torque Motors for Electro-Hydraulic Servo Valve Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium on Advanced Fluid Power Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–18 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Xu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Wang, C. Development of a slotless limited-angle torque motor for reaction wheel torque measurement system. Small Spec. Electr. Mach. 2024, 52, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Zou, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q. Torque Performance Improvement of a Radial-Flux Slotted Limited-Angle Torque Motor by Tapered Tooth-Tip. Int. J. Electr. Mach. Drives 2025, 9, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Sheng, H.; Jiang, S. Integrated physical modeling and optimal control method of limited-angle torque motor in fuel metering apparatus. Micromachines 2022, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdanpanah, R. Analytical study, design, and optimization of radial-flux PM limited-angle torque motors. Sci. Iran. 2022, 29, 1975–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Yoon, S.-Y.; Kwon, S.-O.; Shin, J.-Y.; Park, S.-H.; Lim, M.-S. A study on a slotless brushless DC motor with toroidal winding. Processes 2022, 10, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, D.; Qu, R. Analysis of an Axial-Flux Slotted Limited-Angle Torque Motor with Quasi-Halbach Array for Torque Performance Improvement. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2023, 7, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Research on a novel high-torque-density axial–radial-flux permanent-magnet motor with annular winding for an elevator-traction machine. Electronics 2023, 12, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemoto, T.; Tsunata, Y. A Proposal of an Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Machine Using Soft Magnetic Composite Material for Improved Manufacturability. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2023, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, G.; He, Y.; Lei, X.; Li, D.; Huang, L.; Lee, C.H.T. Investigation of Axial-Flux Limited-Angle Torque Motor with Tooth-Tip Structure for Torque Performance Improvement. In Proceedings of the 2023 26th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS 2023), Zhuhai, China, 5–8 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, D.; He, C.; Li, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, X.; Ma, L.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, H. The Design, Analysis, and Verification of an Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Motor with High Torque Density. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupertino, F.; Pellegrino, G.; Armando, E. Axial-flux permanent-magnet motors for torque-dense applications: Design challenges and manufacturing constraints. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 4574–4585. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, R.; Vaschetto, S.; Gerada, C. Design and analysis of a high-torque-density axial-flux PM machine for aerospace actuation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 107340. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, M.; Dorrell, D.G.; Cossar, C. Energy-based torque analysis of permanent-magnet machines using co-energy and virtual work methods. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Barrière, A.; Lubin, T. Magnetic-energy and co-energy torque calculation methods for rotating electrical machines. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 203, 107672. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, K.; Fukushima, Y. Unified torque computation based on magnetic energy variation in synchronous and reluctance machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 4521–4531. [Google Scholar]

- Abduh, S.; Sadineni, M.; Abdullah, W. Cogging torque reduction by pole-arc and stator-slot optimization in a permanent magnet machine. Energies 2025, 18, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, F.; Jin, S.; Sun, Y. Study on performance of low-speed high-torque permanent-magnet synchronous machines with rotor dynamic eccentricity. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 8, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, D.; Madariaga, C.; Jara, W.; Bramerdorfer, G.; Tapia, J.A.; Riedemann, J. Study on stator-rotor misalignment and its effects on unbalanced magnetic force, cogging torque, back-EMF, and mean torque in PMSMs with modular stator core. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.