Abstract

This manuscript presents a reinforcement learning (RL) agent method to optimize the geometry of a coaxial magnetic gear using a 2D finite element magnetic (FEM) simulation. The proposed optimization algorithm aims to improve the maximum torque within given boundaries of the magnetic gear geometry by adjusting parameterized radii. A linear actor–critic gradient algorithm is implemented, where the actor learns a policy to adjust and discover the values of five geometric parameters of the magnetic gear model, and the critic evaluates the performance of the resulting designs. The RL agent interacts with an environment integrated with a 2D FEM simulation, which provides feedback by calculating the total torque of the new geometry discovered. The optimization algorithm uses a greedy exploration method that uses the total torque as a reward system, which the RL agent aims to maximize. The results obtained for the magnetic gear optimization demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed RL algorithm, which can be applied to automate multiparameter geometric optimization using artificial intelligence systems.

1. Introduction

Magnetic gears have recently gained attention due to their benefits: contactless torque transmission, little to no maintenance, and natural overload protection [1,2]. Their optimal performance is heavily dependent on the precise arrangement of permanent magnets, ferromagnetic segments, and components [2,3,4]. Finding the optimal design for a magnetic gear often involves solving multiparameter complex tasks for achieving maximum torque, structural integrity, and feasibility [5,6]. These problems require heavy computational power and often involve cycles of solving finite element analysis simulations, manual adjustments, and many performance evaluations [7]. While gradient-based optimization can speed up this process, it struggles with non-linear designs, multiple optimization parameters [8], etc. The non-linearity of magnetic gears arises first from the material properties and second from the magnetic field focusing effect. This is essential for their modeling [9,10,11,12], control [13], and design optimization [14,15]. To solve some of these problems and limitations, this manuscript proposes an experimental RL algorithm combined with 2D FEM simulation for optimizing a coaxial magnetic gear design to find its maximum torque within given volume boundaries.

Recent advances in RL have shown promising capabilities in automating complex design optimization tasks, particularly in engineering systems with multiparameter and time-consuming evaluation processes [10,11,12,13]. The RL method is a subfield of machine learning wherein an optimization agent learns to interact with an environment (optimization search space) by taking actions and receiving corrections by a secondary system of rewards or penalties. These corrections are different from environment stimuli that may be provided by the direct objective function or its gradients [15]. Unlike the supervised learning method, in which the agent is provided with explicit labels or correct answers that are not always easily accessible, the RL method requires the optimization agent to learn through trial and error in a secondary reword system, guided by the progress of the optimization problem in the main search space. The process itself is a secondary mapping of the search space from agent actions that maximizes the cumulative reward obtained over time for a single agent. Traditional machine learning methods require predefinition of multiple hyper-parameters to provide proper method functionality. This requires many trial and error runs for method adjustment alone with the problem under consideration, which reduces computational efficiency. These parameters are related to the optimization algorithm itself, learning process parameters, secondary model parameters, etc. These hyper-parameters can outnumber the optimization parameters, requiring more parameter values to be guessed other than those that must be optimized. A new emerging trend designed to solve this issue is the use of self-adjusting parameter algorithms dependent on optimization solution convergence. Hyper-parameter adjustment is automatic during the iterative steps of optimization. This requires a decentralized open model for objective function calculation.

Future design optimization methods will be able to autonomously adapt to problem search space under consideration and autonomously adapt to the computational environment. These will be implementations of real artificial intelligence, which will require limited information provided by the user to produce an optimal solution, maximizing the use of the available computational time and environment.

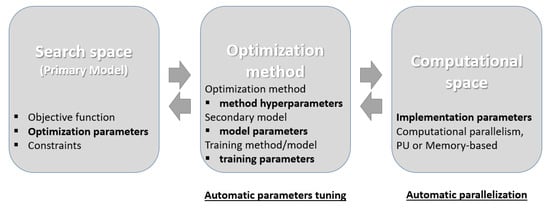

Various RL algorithms address search space secondary mapping or guidance with secondary metrics, typically using neural networks to model the policy and/or value function and thereby enabling the application of RL to complex environments with multiple design parameters with large or continuous states in the search spaces (Figure 1). One of the promising RL frameworks is the actor–critic (RL-AC) algorithm, where two roles are implemented via two neural networks with different functionality and behavior. In this way, variable actions can be estimated according to their impact on the objective function. The risk is to overestimate or underestimate these impacts performed internally for the algorithm stimuli without significant improvement of the desired global objective function.

Figure 1.

Optimization method bilateral interaction with the optimization problem search space from one side and computational environment from the other. The new generation of optimization methods must provide autonomous hyper-parameter tuning and model parameter adjustment.

Figure 1 shows the optimization method’s bilateral interaction, with the optimization problem from one side and computational environment from the other. The new generation of optimization methods must provide autonomous hyper-parameter tuning and model parameter adjustment for the secondary optimization of computational resource usage, especially for parallel processing in different configurations. Automatic parallelization of computing must be integrated in future optimization implementations. There, RL will be directed not only for the optimization but also for the algorithm’s fit within the available computational resources.

In this work, an RL-AC based agent is used to optimize the radial geometry of a coaxial magnetic gear, where the available design space is defined by a set of variables corresponding to geometric radii of its permanent magnets, ferromagnetic segments, and components. By integrating the RL agent and optimization algorithm in Python [15,16] with an FEM simulator [17], the agent “learns” to iteratively optimize a set of geometry parameters to maximize the total torque output. A linear neural network ε-greedy policy [18,19] is trained using feedback from passed iterations and advantage estimation. The RL-AC agent uses an FEM simulator as its environment to explore and discover, using value functions for state evaluations which, throughout each passed episode, tries to maximize its reward-based feedback system. The RL-AC agent seeks maximum reward, which is interconnected with total output torque for each design solution of the coaxial magnetic gear optimization task.

The geometry of the magnetic gear is fully defined by a set of five design parameters that control the relative radial thicknesses of viable regions in the design, which are then scaled to fit the radial span for drawing the FEM model. Each parameter of the geometry is optimized through action policies in an RL loop, either to increase it or to decrease it by a certain step. Actions modify the parameters, trigger a test in FEM simulation to evaluate performance (torque), and use the reward to update the RL agent policy. Over a number of iterations, the RL agent “learns” which parameter adjustments lead to maximum torque and better gear designs. The results obtained show the effectiveness of the presented method and are promising data for implementing a variety of design optimization problems in electromagnetic devices. Moreover, the method can be used to solve and optimize electromagnetic devices with non-linear behavior and complex designs.

The article is structured as follows: after the Introduction, Section 2 presents the coaxial magnetic gear design and its components with geometric parametrization of parameters for optimization. Section 3 presents the RL-AC algorithm’s flow chart and mathematical model and describes how the algorithm operates, as well as describing the FEMM software and governing equations. Section 4 provides results achieved by the RL algorithmic optimization for maximum torque and its corresponding FEM model results, which are discussed and analyzed in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the presented work and its conclusions.

2. Magnetic Gear Design Parametrization and FEM Modeling

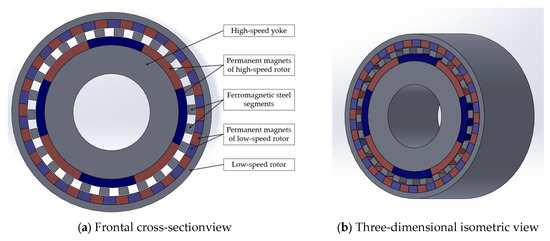

The coaxial magnetic gear design consists of a high-speed yoke, ferromagnetic steel segments, and a low-speed rotor [6,20]. Four permanent pair magnets are mounted on high-speed rotors; there are 26 ferromagnetic steel segments and 22 mounted permanent pairs magnets on the slow-speed rotor. The gear ratio is 5.5. Figure 2 shows a sketch of the design geometry [6,21].

Figure 2.

Coaxial magnetic gear design: frontal cross-section view (a) and 3D isometric view (b).

The design of the magnetic gear shown in Figure 2 is parametrized to be used in 2D FEM analysis simulation. The optimization parameters are radii which are concentrically arranged and limited by the outer and inner magnetic gear radii of the shaft. Therefore, they are calculated to fit the space:

where is the space between inner and outer radii, and dr denotes the radii steps, n is the number of the optimized radii.

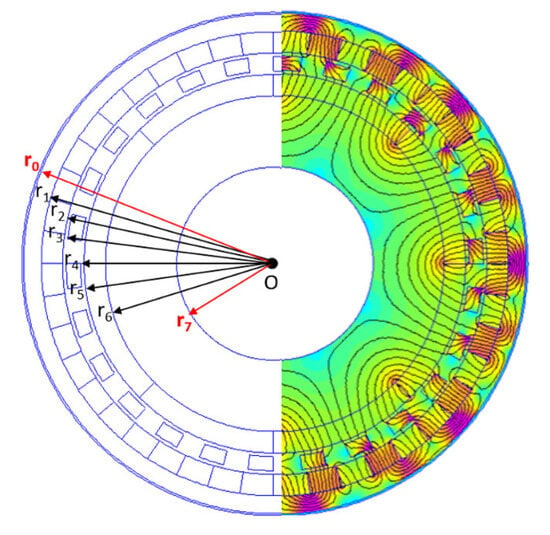

Figure 3 shows the considered radii used for the parametric model implemented in 2D FEM modeling. The inner radius r7 = 30 mm and outer radius r0 = 68 mm are fixed and used as the geometric boundary for the considered optimization task.

Figure 3.

Optimization parameters radii and magnetic field correspondence in the FEM model.

The magnetic field of the magnetic gear geometry was modeled using the FEM solver, which is based on a 2D formulation of the magnetic vector potential. The corresponding boundary conditions are satisfied. The maximum torque was calculated for the created design. Additional information about the 2D modeling of the coaxial magnetic gear can be found in [6,17,18]. The following materials were considered for the model: NdFeB35 was used for the permanent magnets; low-carbon steel AISI 1008 was used for the ferromagnetic steel segments and rotor yokes. Empty space was modeled as air.

The parameterized model for 2D FEM analysis was used as an environment to test and evaluate the RL-AC optimization solution and as corrective feedback.

3. Reinforcement Learning Optimization Framework

The algorithm developed for optimizing the coaxial magnetic gear was written in Python and creates an RL framework [22,23] using the 2D FEM solver as an environment to simulate and evaluate the created designs. Parameterized geometric values of the coaxial magnetic gear are represented by its radii (from r0 to r7) and were used to calculate radial differences between each part of the magnetic gear (dr0 to dr6), excluding dr2 and dr4. These correspond to air gaps and are fixed to 1 mm and considered in the optimization. The five parameters were used to define a five-dimensional vector yp. The radii of the magnetic gear r1 to r7 were used as optimization parameters. For each solved electromagnetic model design, the resulting magnetic torques for inner and outer rotors (Tinner and Touter) were calculated by the 2D FEMM 4.2 software and used as performance feedback to an RL agent, which processed this information to update its policy in order to adjust the geometric parameters and maximize the total torque.

The optimization problem is formulated as maximizing the total torque by modifying the geometric parameters with their respective geometric constraints.

A reward-based [24] system is created, which rewards higher achieved total torques. In the RL environment, the objective function J(yp) serves as a reward:

Each of the five parameters is subjected to an action policy at governed by two actions: increase or decrease its value by discrete step k = 0.1 mm. For the considered parameters, there are ten possible actions which could be taken:

Each pair of actions modifies one of the considered optimizations parameters:

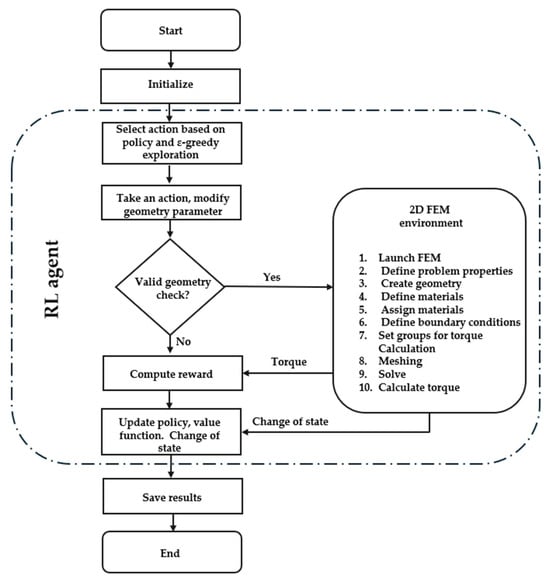

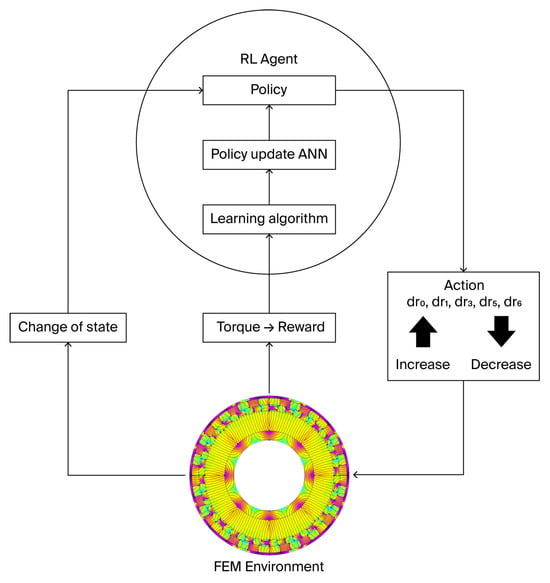

In the proposed algorithm, there are two modules: the RL agent and the environment, which is a created 2D model of the magnetic gear. At time t, the RL agent performs action at, which affects the environment, causing it to transition from state st to state st+1. The state of each of the optimization parameters is stored in a vector form.

After the transition, a new reward is calculated, rt+1, which the RL agent, alongside the state information st+1, uses to select the next action, at+1. The goal of the RL agent is to learn a policy that maximizes the value function :

where is the discount factor, and rt is the calculated reward.

The RL-AC agent is a linear neural network model [25,26] which uses gradient policy to reduce the variance in the estimated advantages. The policy is a linear neural network model which records the current state of the optimized parameters for each possible action. It uses a ε-greedy exploration strategy: With a small probability of ε = 0.1, it selects a random action for the five optimized parameters to explore new geometries; otherwise, it chooses the highest predicted reward. It also has an update gradient policy: It implements a policy to increase the probability of taking actions which lead to higher rewards and decreases the probability of taking actions which lead to lower rewards (total torque). The algorithm’s flow chart is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

RL algorithm flowchart.

3.1. Electromagnetic Simulation with FEM

FEMM 2D software 4.2 was used to create and solve the magnetostatic problem for the magnetic gear model. The magnetic vector potential formulation is used to describe the problem:

where M is the magnetization vector, and it is defined by

where Br is the remanence of the permanent magnets.

A function was created in Python 3.12, which serves as a computational environment to interface directly with the FEM to solve the axisymmetric finite element magnetic field. After the geometry is calculated, the Python algorithm interacts with the FEM and takes steps in order to create and solve the problem:

Torque was calculated for selected regions (inner and outer rotors) using the weighted stress tensor method [17,27,28,29,30]

where n is the directional normal to the surface S enclosing the rotor’s volume, r is the distance vector from the axis of rotation, and H is the magnetic intensity vector.

3.2. Reinforcement Learning Agent

The RL agent uses the actor–critic variant of a policy gradient method [31,32], which is used to calculate advantages and reduce variance. The policy class (the actor) function maps the states of the geometric parameters to actions. The actor policy is a linear mapping from state to action scores:

where W is a learnable weight vector.

For at action selection, an ε-greedy exploration strategy is used with a probability of 1 − ε. The action is selected, and with a small probability of ε, it takes a random action for geometric exploration.

The update uses the advantage values provided by the critique. The advantageous values (the critic) are calculated by a linear neural network for which its output is the expected future reward from any given state.

At the end of each episode, the actual total reward for the episode is calculated as Gt:

Advantage At is defined by predicted future reward V(s) and actual received Gt:

If At > 0, the reward was better than expected, and the actor increases the probability of taking this action again. If At > 0, the reward was worse than expected, and the actor decreases the probability of taking this action again. The actor’s policy weights are updated in the direction of the policy gradient, scaled by this normalized advantage.

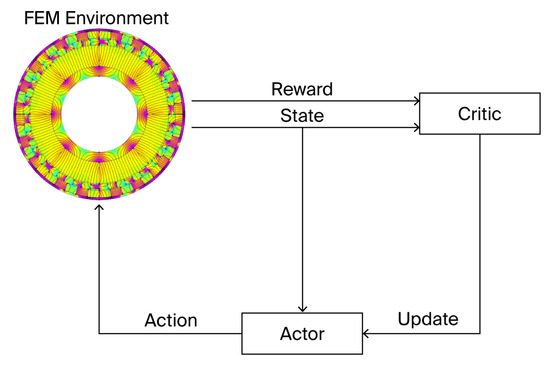

The algorithm’s flow chart for the actor–critic method is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

RL agent policy gradient method (actor–critic).

The main function of the RL-AC agent is to optimize the geometric design parameters of the coaxial magnetic gear for maximum torque. Through iterative interactions with the created 2D FEM environment and discrete modifications of radial thickness parameters, a policy gradient method is deployed. The agent learns a policy to map geometric states and enables actions and adjusts its policy parameters to benefit actions which lead to higher torque. This process of trial and error is navigated by a value function, which allows the agent to achieve better solutions over time. Figure 6 shows the core loop by which the RL-AC operates.

Figure 6.

Core loop of the RL agent with the actor–critic algorithm.

Table 1 shows the hyper-parameters used for the RL-AC algorithm implemented for optimizing the magnetic gear. These are reached by benchmark calibration, as described in reference [22,23].

Table 1.

Hyper-parameters of RL-AC algorithm implementation.

4. Results

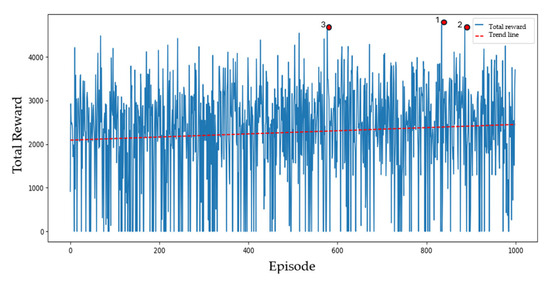

In this section, the results of the RL and actor–critic algorithm implementation are presented, along with data for the learning curve, showing total rewards per episode and torque improvement over the top three episodes. For this optimization task, 1000 episodes were solved, with ten steps taken in each episode. The learning rate used for the algorithm is LR = 0.05.

The three best solutions are presented for the solved iterations; they are the best discovered designs of geometric parameters for the coaxial magnetic gear that lead to the highest torque. The inner and outer radii of the initial design from which the RL-AC algorithm is defined were r0 = 68 mm and r7 = 30 mm. The minimal radial distance was set dr = 0.5 mm to exclude most of the invalid geometries, and the air gaps dr2 and dr4 were set to 1 mm. The results from the 2D analysis are presented for the best three solutions found during the iterations.

Figure 7 shows the learning curve and the total rewards achieved per episode. The top three episodes with the highest torque and reward score are, in descending order, episodes 834, 886, and 557. A trendline is included to show the steady positive improvement of the reward over time. The top three episodes are marked by red dots.

Figure 7.

Learning curve of the RL algorithm. The three best solutions are marked with red dots.

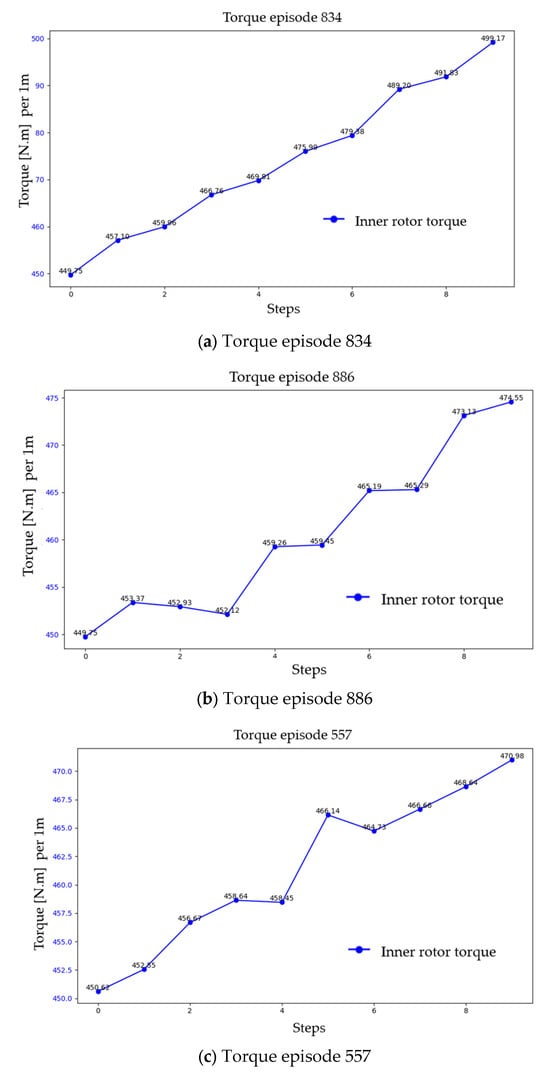

Figure 8 shows the calculated torque data for the inner rotor over the top three episodes with optimal designs during each step.

Figure 8.

Calculated torque during each step of top three rewarded episodes: (a) best-performing episode 834; (b) second-best-performing episode 886; (c) third-best-performing episode 557.

Table 2 summarizes the calculated maximum torque for each of the top three episodes for the optimal design.

Table 2.

Magnetic gear torque for the best three solutions.

Table 3 shows the optimized radii for each of the solutions found for the considered magnetic gear design. The optimal designs are situated in the constrained radii for the coaxial magnetic gear for all three designs. Changes in the radii are small, proving that the optimal design is in that zone.

Table 3.

Magnetic gear radii for the three best solutions.

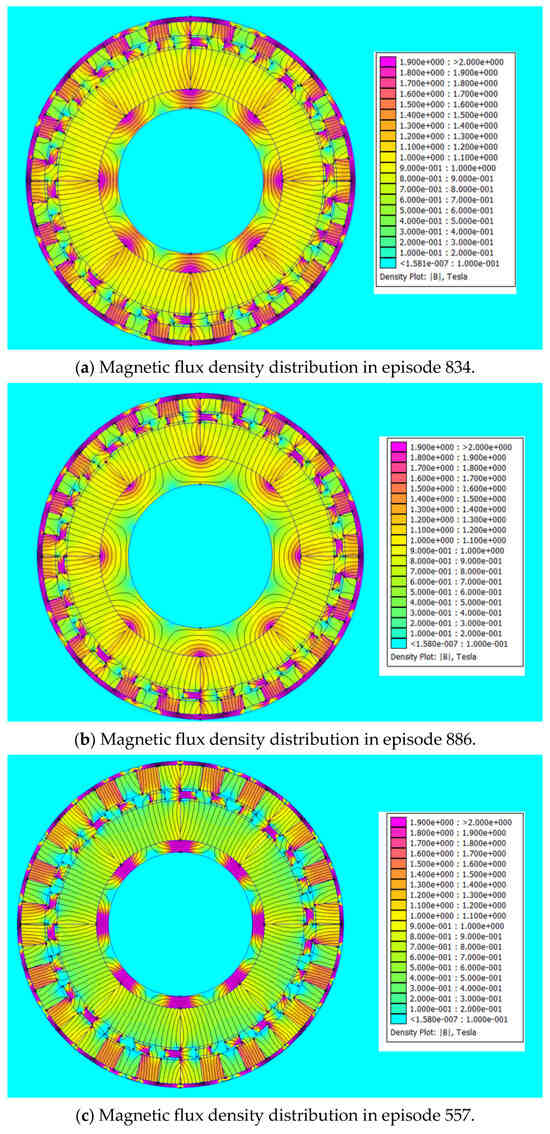

Figure 9 shows magnetic gear flux density distributions for the top three episodes. For solution 3 (episode 557), the flux density is considerably lower than the other two solutions which correspond to lower magnetic torque.

Figure 9.

Magnetic flux density distribution: (a) solution 1—best-performing episode, 834; (b) solution 2—second top-performing episode, 886; (c) solution 3—third top-performing episode, 557.

5. Discussion

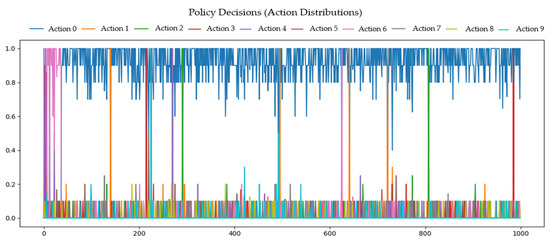

Optimizing the geometric design of coaxial magnetic gears by incorporating an FEM environment and an RL agent is a successful approach. The results obtained are satisfying for the initial discovery and scanning of optimal designs for maximum torque. The algorithm can be further deployed to aid further optimization of the geometric design of the considered magnetic gear. After initial findings of where potential good solutions may be present, another general iteration can be made to optimize the radii, magnetic torque, and other parameters even further by using smaller geometric steps, more steps per episode, and more iterations. Another logical approach is to analyze which parameters influence the design and to continue optimizing only the most important ones. Figure 10 shows the decisions that the RL agent made during optimization. The RL agent was given ten options to choose from but only used one of the ten considered parameters (dr0, dr1, dr3, dr5, and dr6).

Figure 10.

Policy decisions (action distributions) of the RL agent. Fraction 1 or 0 corresponds with increasing or decreasing the parameter. Actions 0 and 1 are adjusting dr0, actions 2 and 3 are adjusting dr1, actions 4 and 5 are adjusting dr3, actions 6 and 7 are adjusting dr5, and actions 8 and 9 are adjusting dr6.

It is notable that the RL agent considered dr0 the most influential parameter over the whole design, while the other parameters have either little influence on maximum torque or a negative one. The parameter dr0 is calculated as the distance between r0 and r1, meaning that the outer diameter of the coaxial magnetic gear is the most influential of the design. The best rewards (torque) are achieved by increasing the outer diameter.

Another good practice could be fixing the outer diameter at reasonable and technically constructable values after initial findings and scanning and deploying the algorithm to optimize the other parameters or adjusting the reward system in order to favor whichever parameter is considered.

Integrating FEM analysis as an environment is an essential approach to allow an RL agent with the actor–critic algorithm to find better designs. This improves the efficiency and effectiveness of the design process by automating the iterative optimization of complex electromagnetic systems. Nevertheless, it is time-consuming and requires computer power. There are many options to solve those problems, such as distributing the calculations over several machines in parallel, using even more computing power, etc. One other way to solve this problem would be, after initial scanning, to replace the FEM environment with a surrogate function which will mimic the magnetic gear. This would speed up the process gradually.

While convergence is not yet achieved, as shown in Figure 7, the results are satisfying regarding the optimum solution and are comparable with previous optimization solutions for the current magnetic gear design, which are fully discussed in reference [6]. For the purposes of this study, Table 4 shows the optimal solutions of a genetic algorithm (GA) with 60 generations and 150 chromosomes described in the previous study.

Table 4.

Maximum magnetic gear torque achieved compared to the GA solution.

The results obtained for maximum magnetic torque of the coaxial magnetic gear show the advantages of the proposed RL-AC method for optimization of complex multiparameter tasks. These results could be used for further analysis and optimization of a variety of design optimization problems of electromagnetic systems and devices.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes and implements an RL-AC algorithm for the design optimization of a coaxial magnetic gear. A linear neural network actor–critic RL agent is developed to adjust five parameters in the form of the gear radii and evaluates the resulting torque from the magnetic gear FEM model simulation. The algorithm deploys an ε-greedy exploration strategy for discovering a new design geometry.

The implementation of RL–AC partially reduces the number of optimization iterations, showing an insignificant decrease in FEM model calls compared with the classical GA, but the smaller number of hyper-parameters to be adjusted makes general performance much faster, especially for optimization problems of unknown complexity. The RL-AC-based approach is an effective way to automate complex, multiparametric design optimization tasks using increasingly autonomous artificial intelligence.

The future of design optimization involves methods that can autonomously adapt to the search space problem under consideration and the computational environment. These will be real artificial intelligence implementations which will require limited information provided by the user to produce an optimal solution, in this way maximizing the use of available computational time and environment.

The developed method using RL-AC algorithm and FEM simulations opens up new perspectives and opportunities for optimization of electromechanical devices. The results obtained for optimization of a coaxial magnetic gear demonstrate its effectiveness and are promising basis for solving a variety of design optimization problems in electromagnetic devices with non-linear behavior and complex designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.I., V.M., I.M., W.G., E.M., and S.M.; methodology, G.I., V.M., I.M., W.G., E.M., and S.M.; software, G.I. and V.M.; validation, G.I., V.M., and I.M.; formal analysis, G.I., V.M., I.M., W.G., E.M., and S.M.; investigation, G.I., V.M., I.M., W.G., E.M., and S.M.; resources, V.M. and W.G.; data curation, G.I., V.M., I.M., W.G., E.M., and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.I., V.M., and I.M.; writing—review and editing, G.I., V.M., I.M., W.G., E.M., and S.M.; visualization, G.I., V.M., I.M., W.G., E.M., and S.M.; supervision, V.M. and W.G.; project administration, V.M. and W.G.; funding acquisition, V.M. and W.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the KP-06-Austria/7 project of the National Science Fund of Bulgaria.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruiz-Ponce, G.; Arjona, M.A.; Hernandez, C.; Escarela-Perez, R. A review of magnetic gear technologies used in mechanical power transmission. Energies 2023, 16, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, P.O.; Andersen, T.; Jorgensen, F.; Nielsen, O. Development of a high-performance magnetic gear. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2005, 41, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezen, S.; Yilmaz, K.; Aktas, S.; Ayaz, M.; Dindar, T. Solid Core Magnetic Gear Systems: A Comprehensive Review of Topologies, Core Materials, and Emerging Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, B.; Crozier, R.; McDonald, A.; Mueller, M. Review of magnetic gear technologies and their applications in marine energy. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2018, 12, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, M.; Alotto, P. Coaxial magnetic gear design and optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 9934–9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, M.; Mateev, V.; Marinova, I. Magnetic gear design optimization by genetic algorithm with ANN controlled crossover and mutation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IV International Conference on High Technology for Sustainable Development (HiTech), Sofia, Bulgaria, 7–8 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Luo, D.; Huang, S. Multi-objective robust optimization for a dual-flux-modulator coaxial magnetic gear. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 8002008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, B. A review of design optimization methods for electrical machines. Energies 2017, 10, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, W.; Kim, W.; Jeong, J.M.; Kim, S.S. Design optimization of 3D printed kirigami-inspired composite metamaterials for quasi-zero stiffness using deep reinforcement learning integrated with bayesian optimization. Compos. Struct. 2025, 359, 119031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Dong, T.; Chen, L.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Y. Multi-objective optimization approach for permanent magnet machine via improved soft actor–critic based on deep reinforcement learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, V.T.; Tuan, D.A.; Van, T.T. Torque control of PMSM motors using reinforcement learning agent algorithm for electric vehicle application. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2025, 14, 2571–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Hao, X.; Pan, D.; Wu, W. Physics-informed neural network for simulating magnetic field of coaxial magnetic gear. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lei, G.; Bramerdorfer, G.; Peng, S.; Sun, X.; Zhu, J. Machine learning for design optimization of electromagnetic devices: Recent developments and future directions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, I.; Mateev, V. Second order genetic algorithm for magnetic design optimization. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2505, p. 080018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L. An Introduction to Python; Network Theory Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Python, version 24. Python Releases for Windows. Python Software Foundation: Wolfeboro Falls, NH, USA, 2021.

- Meeker, D. FEMM 4.2 Magnetostatic Tutorial. Computer Program. 2006. Available online: https://www.femm.info/wiki/MagneticsTutorial (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Dos Santos Mignon, A.; da Rocha, R.L.d.A. An adaptive implementation of ε-greedy in reinforcement learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 109, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokic, M. Adaptive ε-greedy exploration in reinforcement learning based on value differences. In Annual Conference on Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova, M.; Mateev, V.; Marinova, I. Permanent magnets for a magnetic gear. In Proceedings of the 2016 19th International Symposium on Electrical Apparatus and Technologies (SIELA), Bourgas, Bulgaria, 29 May–1 June; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marth, E.; Gruber, W.; Mallinger, S.; Mateev, V.; Marinova, I. Magnetic-Geared Bearingless Motor Unit with Central Exterior Output. In Proceedings of the 2024 23rd International Symposium on Electrical Apparatus and Technologies (SIELA), Bourgas, Bulgaria, 12–15 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Di Barba, P.; Gottvald, A.; Savini, A. Global Optimization of Loney’s Solenoid: A Benchmark Problem. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 1995, 6, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PyTorch Foundation. Actor-Critic Methods. Meta. 2022. Available online: https://docs.pytorch.org/rl/main/reference/objectives_actorcritic.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Tadepalli, P.; Ok, D. Model-based average reward reinforcement learning. Artif. Intell. 1998, 100, 177–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oja, E. Principal components, minor components, and linear neural networks. Neural Netw. 1992, 5, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolcu, U.; Egrioglu, E.; Aladag, C.H. A new linear & nonlinear artificial neural network model for time series forecasting. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, D. Finite element method magnetics. FEMM 2010, 4, 162. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, I.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.V.; Norouzi, M.; Bengio, S. Neural combinatorial optimization with reinforcement learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.09940. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, J.; Xia, Y.; Peng, X.; Shi, X.; Zhu, X.; Qu, B.; Yang, K. Multi-Objective Collaborative Optimization of Magnetic Gear Compound Machines Using Parameter Grouping and Kriging Surrogate Models. Energies 2025, 18, 6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salon, S. Finite Element Analysis of Electrical Machines; Springer: Troy, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein, M.; Barto, A.G.; Si, J.; Barto, A.; Powell, W.; Wunsch, D. Supervised actor-critic reinforcement learning. In Learning and Approximate Dynamic Programming: Scaling Up to the Real World; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 359–380. [Google Scholar]

- Gruslys, A.; Dabney, W.; Azar, M.G.; Piot, B.; Bellemare, M.; Munos, R. The reactor: A fast and sample-efficient actor-critic agent for reinforcement learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04651. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).