Design and Validation of a Soft Pneumatic Submodule for Adaptive Humanoid Foot Compliance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Antagonistic Tri-Layer Design: Symmetric pneumatic chambers achieving stiffness modulation without geometric deformation.

- Single-Shot Wax-Core Fabrication: Co-molding of soft, rigid, and inextensible materials for alignment and durability.

- Analytical Pressure–Stiffness Model: Linear closed-form formulation validated experimentally.

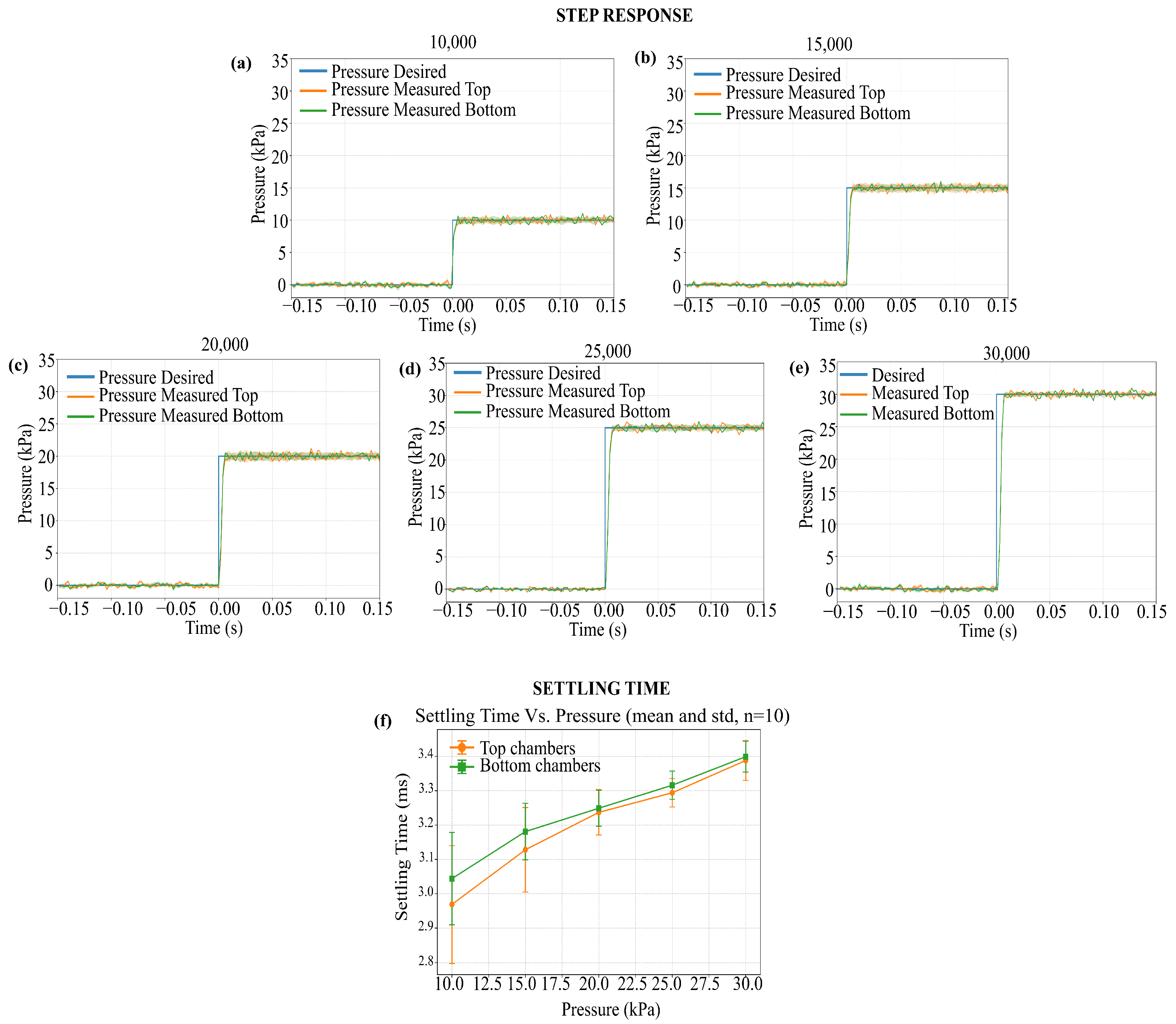

- Experimental Validation: Tunable stiffness (0.18–0.43 N·m/rad, 0–30 kPa), fast response (2.9–3.4 ms stable behavior under cyclic loading).

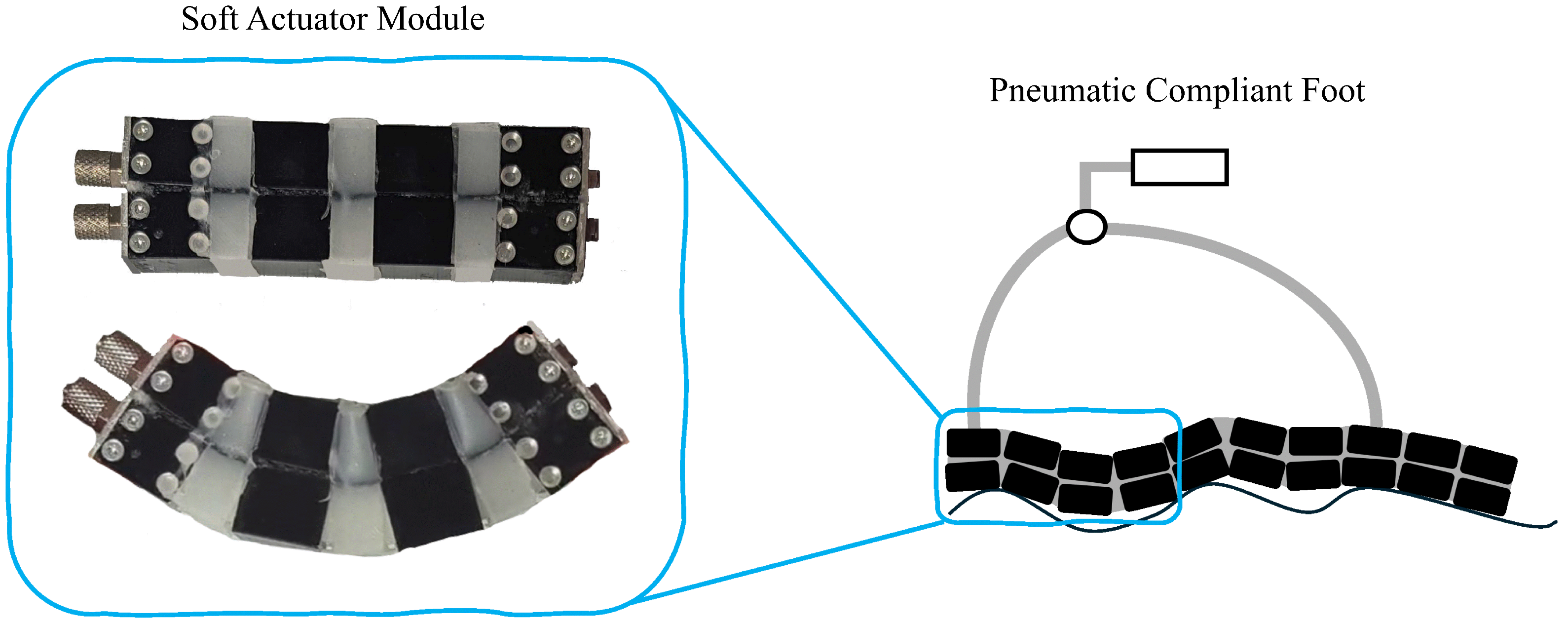

2. Antagonistic Tri-Layer Actuator Design

2.1. Design Concept and Working Principle

2.2. Structural Architecture and Components

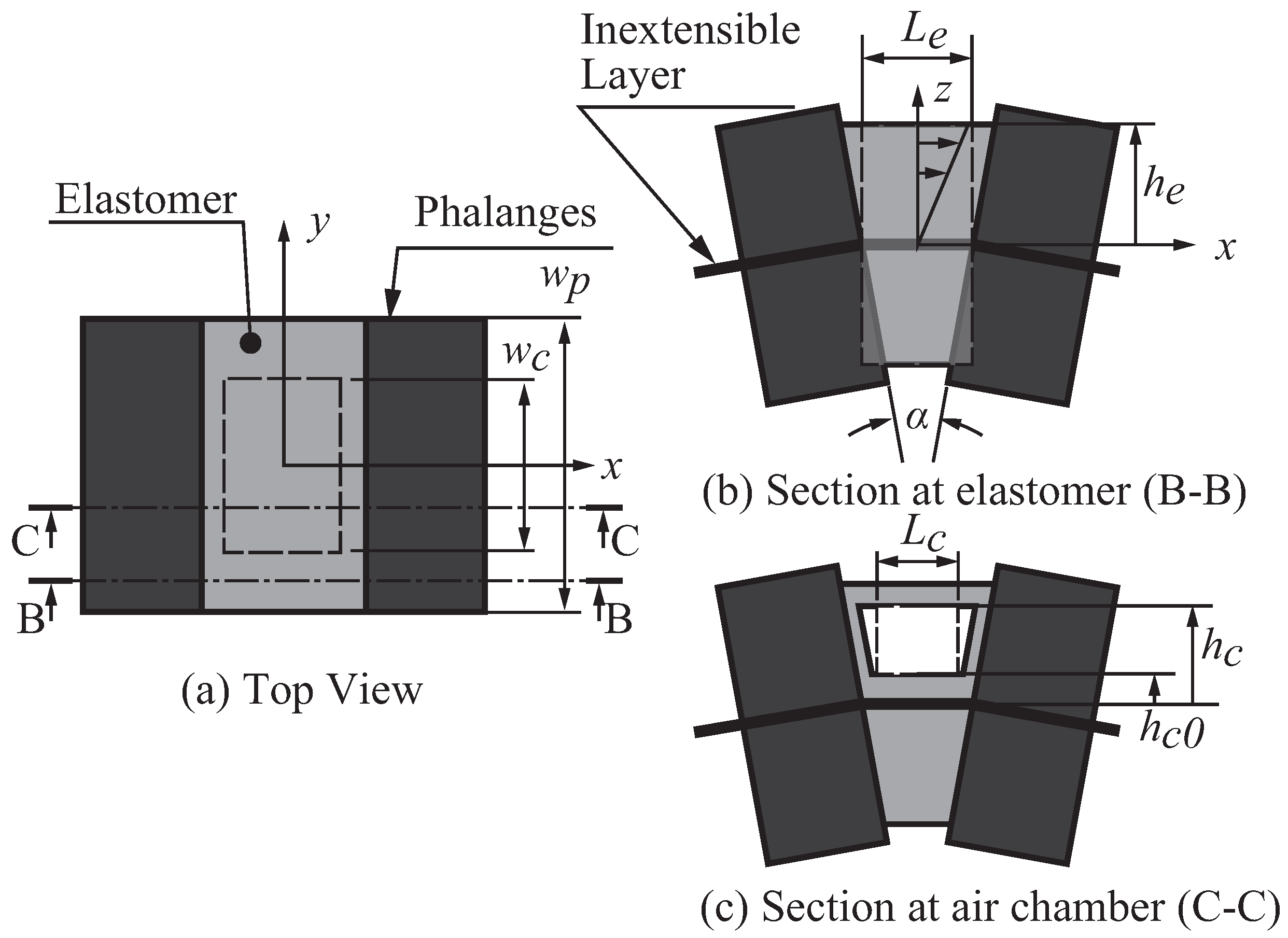

2.3. Geometric Definition

| Symbol | Description | Value [mm] |

|---|---|---|

| Total submodule length | 102 | |

| Pitch length (rigid + soft span) | 17.6 | |

| Length of soft silicone segment | 10.6 | |

| l | Chamber length | 7.0 |

| Total submodule width (including enclosure) | 20.0 | |

| w | Chamber width | 8.0 |

| Half-height (top or bottom section) | 15.0 | |

| h | Total chamber height (top + bottom) | 9.0 |

| Chamber cavity height | 5.0 | |

| Inextensible layer thickness | 1.2 |

2.4. Prototype Implementation

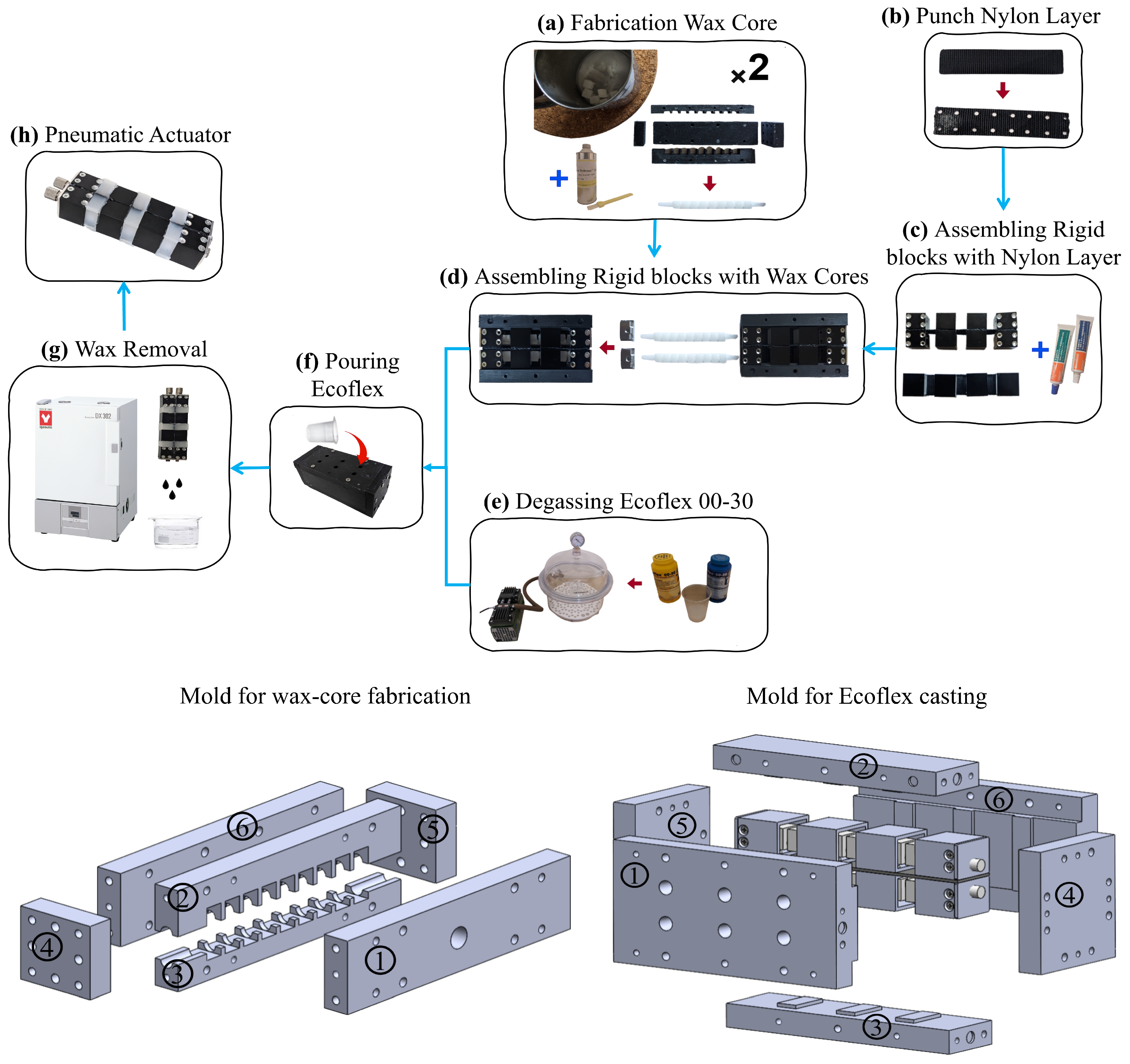

3. Monolithic Wax-Core Fabrication

3.1. Fabrication Workflow

3.2. Advantages over Existing Manufacturing Methods

4. Analytical Modeling of Pressure–Stiffness Relationship

4.1. Model Assumptions and Geometry

- Internal pressure is uniform and equal in both chambers (no differential bending).

- Deformation remains small (<25% strain), allowing linear elasticity for Ecoflex 00–30.

- Radial expansion is negligible due to confinement from the aluminum blocks and nylon sheet.

- Air behavior is isothermal and follows the ideal gas law.

4.2. Analytical Derivation

- Elastic contribution

- Pneumatic contribution

- Total stiffness

4.3. Discussion

5. Experimental Validation

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Results for Static Characterization: Stiffness–Pressure Relationship

5.3. Results for Dynamic Characterization: Step Response and Timing

5.4. Results for Dynamic Loading: Pulsed Stimuli Tests

5.5. Discussion of Experimental Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, F.; Wang, M.Y. Design optimization of soft robots: A review of the state of the art. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2020, 27, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Rodenberg, N.; Amend, J.; Mozeika, A.; Steltz, E.; Zakin, M.R.; Lipson, H.; Jaeger, H.M. Universal robotic gripper based on the jamming of granular material. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18809–18814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steltz, E.; Mozeika, A.; Rembisz, J.; Corson, N.; Jaeger, H. Jamming as an enabling technology for soft robotics. In Proceedings of the Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD), San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 March 2010; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 7642, pp. 640–648. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S.; Grioli, G.; Eiberger, O.; Friedl, W.; Grebenstein, M.; Höppner, H.; Burdet, E.; Caldwell, D.G.; Carloni, R.; Catalano, M.G.; et al. Variable stiffness actuators: Review on design and components. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2015, 21, 2418–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Zidek, T.; Harbel, C.; Yoon, S.; Strickland, F.S.; Kumar, S.; Shin, M. Soft robotics: A review of recent developments of pneumatic soft actuators. Actuators 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Atab, N.; Mishra, R.B.; Al-Modaf, F.; Joharji, L.; Alsharif, A.A.; Alamoudi, H.; Diaz, M.; Qaiser, N.; Hussain, M.M. Soft actuators for soft robotic applications: A review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 2000128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chen, Y.; Han, T.; Jiao, C.; Lian, B.; Song, Y. A soft gripper with variable stiffness inspired by pangolin scales, toothed pneumatic actuator and autonomous controller. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2020, 61, 101848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, H. Soft robotic finger with variable effective length enabled by an antagonistic constraint mechanism. Smart Mater. Struct. 2023, 32, 055001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X. A soft gripper based on PneuNets structure with stiffness-variable-enhanced load capacity for object grasping. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 383, 116253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, S.; Dai, J.; Oseyemi, A.E.; Liu, L.; Du, N.; Lv, F. A modular soft gripper with combined pneu-net actuators. Actuators 2023, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Gupta, S.; Khosla, A.; Furukawa, H. Transforming soft robotics: Laminar jammers unlocking adaptive stiffness potential in pneunet actuators. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 047007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, F.; Frohn-Sörensen, P.; Engel, B.; Manns, M. Applicability of models to predict the bending behavior of soft pneumatic grippers. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, M.; Ding, L.; Lu, N.; Yu, C.; Ye, X. Modeling analysis of soft Pneu-Net actuators from low to high pressure in free space. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2025, 239, 5034–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, K.; Iwazawa, R.; Kaneko, M. Modeling and analysis of a high-speed adjustable grasping robot controlled by a pneumatic actuator. Robotics 2022, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Song, Z.; Chen, S.; Gu, G.; Zhu, X. Morphological design for pneumatic soft actuators and robots with desired deformation behavior. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 4408–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; Majit, M.R.A.; Shih, B.; Schulze, J.P.; Tolley, M.T. Variable stiffness devices using fiber jamming for application in soft robotics and wearable haptics. Soft Robot. 2022, 9, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, R.; Tawk, C.; Alici, G.; Sariyildiz, E. A 3D printed monolithic soft gripper with adjustable stiffness. In Proceedings of the IECON 2017-43rd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Beijing, China, 29 October–1 November 2017; pp. 6235–6240. [Google Scholar]

- Polygerinos, P.; Lyne, S.; Wang, Z.; Nicolini, L.F.; Mosadegh, B.; Whitesides, G.M.; Walsh, C.J. Towards a soft pneumatic glove for hand rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 1512–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Polygerinos, P.; Wang, Z.; Overvelde, J.T.; Galloway, K.C.; Wood, R.J.; Bertoldi, K.; Walsh, C.J. Modeling of soft fiber-reinforced bending actuators. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, F.; Walsh, C.J.; Bertoldi, K. Automatic design of fiber-reinforced soft actuators for trajectory matching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkadesan, M.; Yawar, A.; Eng, C.M.; Dias, M.A.; Singh, D.K.; Tommasini, S.M.; Haims, A.H.; Bandi, M.M.; Mandre, S. Stiffness of the human foot and evolution of the transverse arch. Nature 2020, 579, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, J.T.M.; Zhang, M.; An, K.N. Effects of plantar fascia stiffness on the biomechanical responses of the ankle–foot complex. Clin. Biomech. 2004, 19, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loram, I.D.; Lakie, M. Direct measurement of human ankle stiffness during quiet standing: The intrinsic mechanical stiffness is insufficient for stability. J. Physiol. 2002, 545, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Krebs, H.I.; Patterson, S.L.; Judkins, T.N.; Khanna, I.; Forrester, L.W.; Macko, R.M.; Hogan, N. Measurement of human ankle stiffness using the anklebot. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 10th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 13–15 June 2007; pp. 356–363. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, R.; Weiss, P.; Morier, R. System identification of human ankle dynamics: Intersubject variability and intrasubject reliability. Clin. Biomech. 1990, 5, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, D.A. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Gait: Normal, Elderly and Pathological; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.L. Soft bending actuator with fiber-jamming variable stiffness and fiber-optic proprioception. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 7344–7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyildiz, E.; Mutlu, R.; Roberts, J.; Kuo, C.H.; Ugurlu, B. Design and control of a novel variable stiffness series elastic actuator. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2023, 28, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.M.; Miao, Y.; Liao, C.R.; Chen, W.M. A new variable stiffness absorber based on magneto-rheological elastomer. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2009, 19, s611–s615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J. A novel variable stiffness and tunable bending shape soft robotic finger based on thermoresponsive polymers. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, H.; Lu, J. Recent advances in shape–memory polymers: Structure, mechanism, functionality, modeling and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1720–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Jaarsveld, H.; Grootenboer, H.; De Vries, J.; Koopman, H.F. Stiffness and hysteresis properties of some prosthetic feet. Prosthetics Orthot. Int. 1990, 14, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.T.; Halsne, E.G.; Caputo, J.M.; Curran, C.S.; Hansen, A.H.; Hafner, B.J.; Morgenroth, D.C. Prosthetic forefoot and heel stiffness across consecutive foot stiffness categories and sizes. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryggvason, H.; Starker, F.; Lecomte, C.; Jonsdottir, F. Use of dynamic FEA for design modification and energy analysis of a variable stiffness prosthetic foot. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, C.; Ármannsdóttir, A.L.; Starker, F.; Tryggvason, H.; Briem, K.; Brynjolfsson, S. Variable stiffness foot design and validation. J. Biomech. 2021, 122, 110440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merces, L.; Ferro, L.M.M.; Thomas, A.; Karnaushenko, D.D.; Luo, Y.; Egunov, A.I.; Zhang, W.; Bandari, V.K.; Lee, Y.; McCaskill, J.S.; et al. Bio-Inspired Dynamically Morphing Microelectronics toward High-Density Energy Applications and Intelligent Biomedical Implants. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2313327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Yang, K.; Hu, H.; Qi, S.; Fang, L.; Han, L.; Zhang, R. Highly-sensitive ultrathin flexible pressure sensor based on quasi-2D conductive network for human physiological signal monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 154355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Geom. Change | Stiffness (N·m/rad) | Resp. Time | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer/particle jamming [2,3,27] | No | 0.1–5 | 0.1–1 s | Poor |

| Series-elastic (VSA) [4,28] | Yes | 1–50 | 10–100 ms | Limited |

| Smart materials (DE, MR, SMP) [29,30,31] | Small | <1 | 0.1–10 s | Low |

| Fiber-reinforced SPA [19,20] | Yes | 0.1–1 | 50–200 ms | Moderate |

| PneuNet SPA [17,18] | Yes | 0.05–0.5 | 100–500 ms | Good |

| Proposed tri-layer | No | 0.18–0.43 | 2.9–3.4 ms | High |

| System/Reference | Metric | Stiffness (N·m/rad) | Resp. Time/Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human ankle–foot (stance) [23,24] | quasi-stiffness | 0.2–0.6 | 1–3 Hz |

| Human foot arch (passive) [21,22] | longitudinal | 0.1–0.4 | <2 Hz |

| Prosthetic feet (ESR type) [32,33] | effective roll-over | 0.3–1.0 | ≲2 Hz |

| Variable-stiffness prosthetic foot [34,35] | tunable effective | 0.2–1.0 | ∼1–5 Hz |

| This work (submodule) | pressure-controlled | 0.18–0.43 | 2.9–3.4 ms (>250 Hz) |

| Projected full sole (from this work) | pressure-controlled | 0.09–0.22 | 38–50 ms (>20 Hz) a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frizza, I.; Kaminaga, H.; Fraisse, P.; Venture, G. Design and Validation of a Soft Pneumatic Submodule for Adaptive Humanoid Foot Compliance. Machines 2025, 13, 1142. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121142

Frizza I, Kaminaga H, Fraisse P, Venture G. Design and Validation of a Soft Pneumatic Submodule for Adaptive Humanoid Foot Compliance. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1142. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121142

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrizza, Irene, Hiroshi Kaminaga, Philippe Fraisse, and Gentiane Venture. 2025. "Design and Validation of a Soft Pneumatic Submodule for Adaptive Humanoid Foot Compliance" Machines 13, no. 12: 1142. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121142

APA StyleFrizza, I., Kaminaga, H., Fraisse, P., & Venture, G. (2025). Design and Validation of a Soft Pneumatic Submodule for Adaptive Humanoid Foot Compliance. Machines, 13(12), 1142. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121142