Abstract

Intelligent Fault Diagnosis (IFD) systems are integral to predictive maintenance and real-time monitoring but often encounter challenges such as data scarcity, non-linearity, and changing operational conditions. To address these challenges, we propose an enhanced transfer learning framework that integrates the Universal Adaptation Network (UAN) with Spectral-normalized Neural Gaussian Process (SNGP), WideResNet, and attention mechanisms, including self-attention and an outlier attention layer. UAN’s flexibility bridges diverse fault conditions, while SNGP’s robustness enables uncertainty quantification for more reliable diagnostics. WideResNet’s architectural depth captures complex fault patterns, and the attention mechanisms focus the diagnostic process. Additionally, we employ Optuna for hyperparameter optimization, using a structured study to fine-tune model parameters and ensure optimal performance. The proposed approach is evaluated on benchmark datasets, demonstrating superior fault identification accuracy, adaptability to varying operational conditions, and resilience against data anomalies compared to existing models. Our findings highlight the potential of advanced machine learning techniques in IFD, setting a new standard for applying these methods in complex diagnostic environments.

Keywords:

transfer learning; UAN; attention; SNGP; IFD; optimization; diagnostics; prognostics; predictive maintenance 1. Introduction

Industrial systems are becoming increasingly interconnected, automated, and data driven. As a result, the reliability of rotating machinery and electromechanical systems has become central to safety-critical and productivity-critical environments. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis (IFD) has therefore emerged as a key enabler of predictive maintenance, early fault identification, and overall system resilience. However, practical deployment of IFD remains challenging due to three persistent obstacles: data scarcity, domain shift, and unseen fault types.

First, many industrial environments provide only limited labeled fault data. Fault events are rare, costly to reproduce, and often undocumented, leading to severe class imbalance and insufficient training samples. Second, operational conditions vary between machines; changes in speed, load, sensor mounting, structural resonance, and ambient environment induce substantial differences in the underlying data distribution. Models trained under one operating regime frequently generalize poorly to another, a problem broadly known as domain shift. Third, real-world systems frequently encounter unknown or novel faults not represented in the training data, requiring IFD systems to recognize when predictions fall outside their scope.

Traditional deep learning approaches struggle under these constraints. Even advanced transfer learning models may address domain shift but typically do not incorporate open-set recognition or uncertainty quantification, both of which are critical for safety in industrial environments. The lack of unified approaches that jointly address all three challenges: domain adaptation, open-set robustness, and reliable uncertainty estimation, limits the practical uptake of IFD systems outside controlled laboratory settings.

To address these gaps, this study proposes a unified transfer-learning framework that integrates several complementary mechanisms:

- Universal Adaptation Network (UAN) to handle domain shift and partial label mismatch between source and target domains.

- WideResNet backbone for extracting rich, robust features that improve discriminability across vibration regimes.

- Self-attention and Outlier Attention to emphasize diagnostically relevant frequency–temporal regions while suppressing noise and non-stationary artifacts.

- OpenMax to introduce open-set recognition and reject unseen fault categories.

- Spectral-normalized Neural Gaussian Process (SNGP) to provide distance-aware uncertainty, improving model reliability in unfamiliar conditions.

Individually, these mechanisms have been studied within machine learning and fault diagnosis literature, but their combined, synergistic use in an IFD-specific transfer learning pipeline has not been explored. Our central contribution lies not in inventing new algorithms, but in constructing and analyzing a principled, application-driven architecture that integrates domain adaptation, robust feature extraction, open-set modeling, and uncertainty estimation into a single workflow.

This work addresses the following research questions:

- Can a unified transfer learning framework combining UAN, WideResNet, attention mechanisms, OpenMax, and SNGP improve diagnostic robustness across domain shifts?

- How do these components interact, and under which transfer conditions does each mechanism provide the greatest benefit?

- Can uncertainty-aware evaluation metrics better capture the reliability of IFD predictions under shifting operating conditions?

- What are the limitations of this combined approach, particularly when evaluated on classical datasets such as CWRU?

To answer these questions, we evaluate the proposed framework across multiple source → target transfer tasks on the widely used Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) bearing dataset. Although CWRU is a laboratory dataset, it remains the most widely adopted benchmark for domain adaptation in IFD and allows controlled assessment of transfer conditions. We further emphasize interpretability by analyzing performance trends, quantifying outlier behavior, and assessing the role of uncertainty in predicting unfamiliar conditions.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents a structured literature review and identifies the research gap motivating our approach. Section 3 details the proposed methodology, including theoretical justification for combining the selected components. Section 4 describes the case study design, data preprocessing pipeline, and transfer tasks. Section 5 presents the experimental results and corresponding analyses. Section 6 outlines limitations and discussion points, Section 7 discusses the future work path and Section 8 concludes the work discussed in the paper.

2. Literature Review

Intelligent Fault Diagnosis (IFD) has benefited significantly from the rise of machine learning, particularly deep learning approaches that extract discriminative features from vibration and acoustic signals. However, traditional supervised learning models often exhibit poor robustness when operating conditions change, training data are scarce, or novel fault types emerge. As a result, recent research has increasingly focused on transfer learning, domain adaptation, open-set recognition, and uncertainty-aware architectures to make IFD systems more reliable in real industrial deployments.

2.1. Transfer Learning for Fault Diagnosis

Transfer learning has become a central strategy for dealing with dataset scarcity and distribution mismatch in IFD. Early works centered on applying convolutional neural networks (CNNs) pretrained under specific conditions to new machine states or load regimes. Zhao et al. [1], Liu et al. [2], and Han et al. [3] demonstrated that transfer learning notably improves diagnostic performance when labeled data are limited, particularly under cross-load or cross-speed variations. These studies established that the extracted features can be moderately transferable, but they also highlighted significant performance drops under larger domain shifts.

2.2. Domain Adaptation Approaches

Beyond simple transfer learning, domain adaptation explicitly aims to align feature distributions between source and target domains. Popular techniques include discrepancy-based approaches (e.g., Maximum Mean Discrepancy and Joint Distribution Adaptation), adversarial strategies, and subspace alignment.

- Zhang et al. [4], Si, [5], and Xia [6] applied deep learning with subspace alignment or MMD-based adaptation to improve cross-domain robustness.

- Lei et al. [7] surveyed machinery prognostics frameworks and emphasized the importance of domain-aware signal representations.

- More recent MDPI contributions such as Zhao et al. [8], Xu et al. [9], Li et al. [10], and Zhong et al. [11] demonstrated increasingly sophisticated adversarial and dual-adversarial mechanisms tailored to bearing and rotating machinery diagnostics.

These studies collectively indicate that domain mismatch significantly affects IFD performance, and adaptation mechanisms remain essential for reliable generalization.

2.3. Semi-Supervised and Class-Imbalance Considerations

Semi-supervised transfer learning has also been explored to mitigate the lack of target-domain labels. Zong et al. [12] introduced a framework addressing class imbalance and unlabeled samples in bearing fault classification. Studies by Zhang et al. [13], Chen et al. [14], and Liu et al. [15] broaden these discussions by examining transfer learning in broader industrial processes, emphasizing challenges such as limited labeled anomalies and operational variability.

2.4. Advanced Feature Extractors and Attention Mechanisms

Deep residual architectures, particularly WideResNet variants, have shown promise due to their ability to model complex temporal patterns with less overfitting. Kim et al. [16] demonstrated the advantages of widening residual blocks to extract richer representations.

In parallel, attention mechanisms, including self-attention and multi-head attention, have gained traction for IFD applications. Lv et al. [17] reviewed how attention helps isolate salient spectral–temporal features, improving model interpretability and diagnostic precision even under noisy and nonstationary conditions. Attention methods have further enabled more robust multi-domain fusion, feature weighting, and anomaly localization in real-world machinery environments.

2.5. Open-Set Recognition and Outlier Handling

Traditional classifiers assume that all test samples belong to known classes, which is unrealistic in industrial settings. OpenMax, introduced by Bendale and Boult [18], is a seminal open-set recognition method that adjusts softmax outputs using class-specific activation distributions. Extensions and open-set models for safety-critical systems. such as the works of Henriksson et al. [19] and Lv et al. [20], show that incorporating outlier detection reduces erroneous high-confidence predictions on novel or unseen faults. However, open-set recognition remains underexplored in IFD, with most existing works focusing on closed-set scenarios.

2.6. Uncertainty Quantification in IFD

A growing concern in real deployments is the inability of deep networks to quantify uncertainty. Overconfidence on unfamiliar inputs can severely undermine the trustworthiness of diagnostic systems. Liu et al. [21] introduced Spectral-Normalized Neural Gaussian Processes (SNGP), which combine spectral norm regularization with a Gaussian process output layer to produce distance-aware uncertainty estimates. Although SNGP has demonstrated superior calibrated uncertainty in general machine learning, its integration into IFD and its interaction with domain adaptation and open-set recognition remain largely unexplored. Most IFD studies to date rely on softmax confidence or Monte Carlo dropout, offering limited reliability under domain shift.

2.7. Research Gap and Motivation

Despite significant progress in transfer learning, domain adaptation, attention mechanisms, open-set modeling, and uncertainty estimation, existing studies treat these components in isolation. Prior work typically focuses on one of the following:

- Improving domain alignment;

- Strengthening feature extraction;

- Capturing salient temporal–spectral regions;

- Rejecting unknown faults; or

- Estimating uncertainty.

However, no existing IFD framework simultaneously integrates domain adaptation (UAN), robust deep feature extraction (WideResNet), attention mechanisms, open-set recognition (OpenMax), and uncertainty quantification (SNGP) within a unified transfer learning pipeline. Furthermore, the literature lacks a systematic analysis of how these components interact under different transfer tasks, and how their synergistic combination affects robustness, reliability, and outlier handling.

This gap motivates the present work: a cohesive and theoretically justified integration of these complementary mechanisms to address domain shift, unknown faults, and uncertainty; core challenges that hinder the practical deployment of IFD models in industrial environments.

3. Methodology

This section presents the proposed transfer learning framework for Intelligent Fault Diagnosis (IFD). The method integrates five complementary components: Universal Adaptation Network (UAN) for domain adaptation, WideResNet for deep feature extraction, Self-Attention and Outlier Attention mechanisms for salient feature weighting, OpenMax for open-set recognition, and Spectral-normalized Neural Gaussian Process (SNGP) for distance-aware uncertainty. Although each component originates from established literature, their joint, principled combination in an IFD-specific transfer learning system has not been previously explored.

3.1. Theoretical Rationale for Component Integration

Although UAN, WideResNet, attention mechanisms, OpenMax, and SNGP are established techniques individually, their combined purpose in an Intelligent Fault Diagnosis pipeline is fundamentally complementary. Each address one of the structural challenges in IFD:

Challenge 1: Domain Shift

- −

- Differences in load, speed, and sensor configuration create severe distribution mismatch.

- −

- UAN explicitly aligns latent distributions while simultaneously identifying shared vs. private classes across domains, making it suitable for realistic cross-condition bearing diagnostics.

Challenge 2: Feature Robustness

- −

- Vibration signals contain multi-frequency structures, harmonics, impulsive transients, and noise.

- −

- WideResNet improves representation capacity without excessively deep architectures, enabling the model to capture salient fault patterns while remaining trainable under limited data.

Challenge 3: Salient Region Identification

- −

- Fault patterns are not uniformly distributed; important features appear in specific spectral-temporal windows.

- −

- Self-attention highlights informative channels/time regions, and the proposed Outlier Attention module amplifies anomalous patterns that deviate from normal spectral structure.

Challenge 4: Unseen Fault Types (Open Set)

- −

- Real machines frequently encounter faults not represented in training data.

- −

- OpenMax adjusts softmax predictions based on activation distances, enabling recognition of unfamiliar faults.

Challenge 5: Uncertainty Awareness

- −

- Overconfident predictions on unfamiliar conditions undermine trustworthiness.

- −

- SNGP adds distance-aware uncertainty, preventing overconfident misclassification and improving safety under domain shift.

Taken together, these mechanisms form a unified architecture that addresses some of the main failure modes of real-world IFD systems: insufficient labeled data, mismatched domains, and unseen anomalies. This synergy constitutes the true novelty of the work; a cohesively designed, practically motivated integration of methods that have not been utilized in prior IFD literature.

Although the proposed framework integrates several components, its reliability arises from the functional complementarity and modularity of the design. UAN targets inter-domain distribution mismatch, WideResNet captures complex vibration dynamics, attention modules refine feature saliency, OpenMax handles unknown fault behavior, and SNGP constrains predictive overconfidence. Each component addresses a distinct failure mode of IFD systems. Because these modules operate at different stages of the pipeline, their interactions are stable and predictable, forming a principled and reliable architecture rather than an arbitrary accumulation of techniques.

3.2. Overall Architecture

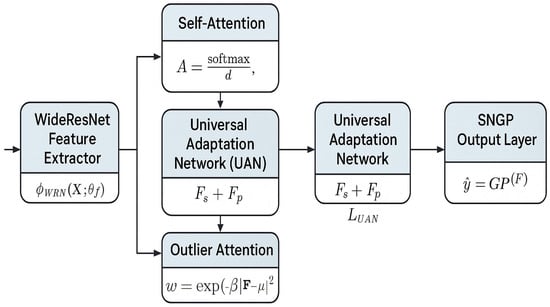

The proposed architecture processes data through five sequential modules:

- WideResNet Feature Extractor

- −

- Input segmented vibration windows.

- −

- Extracts hierarchical temporal-frequency representations.

- −

- Wider filters improve sensitivity to impulsive faults.

- Attention Mechanisms

- −

- Self-Attention: Identifies critical temporal segments and frequency components.

- −

- Outlier Attention: Assigns higher weights to unusual patterns indicating unknown or emerging faults.

- Universal Adaptation Network (UAN)

- −

- Encodes source and target features into shared/private subspaces.

- −

- Uses class-level and instance-level weights to align shared distributions while reducing negative transfer.

- OpenMax Layer

- −

- Computes Mean Activation Vectors (MAVs) for known classes.

- −

- Rebases logits using Weibull modeling to allocate probability mass to an “unknown” class.

- SNGP Output Layer

- −

- Applies spectral normalization to stabilize feature representations.

- −

- Adds a Gaussian process output layer to produce calibrated uncertainty scores.

Information flows through this pipeline as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture flow.

3.3. Mathematical Formulation

- Feature Extraction via WideResNet

Let represent segmented vibration sequences (batch × time). WideResNet maps the input to latent features:

where

- : WideResNet mapping function

- : learnable WRN parameters

- : extracted latent features

- : latent feature dimensionality

WRN converts raw vibration windows into discriminative, higher-level representations capturing impulsive content, harmonics, and transient patterns.

- Attention and Outlier Attention

Self-attention focuses on the relationships between temporal/spectral components:

where

- : Query matrix

- : Key matrix

- : Value matrix

- : scaling dimension for numerical stability

- : refined, attention-weighted representation

Self-attention learns which time-frequency locations in the signal should be emphasized for diagnosis.

Outlier attention highlights unusual feature patterns, useful for unknown fault detection:

where

- : i-th sample feature vector

- : learned “normal-pattern center” in latent space

- : scaling hyperparameter

- : outlier emphasis weight

This weight down- or up-weights features that significantly differ from normal operating patterns.

The final attention-enhanced feature:

where

- : elementwise multiplication

- : enhanced feature combining learned attention and anomaly emphasis

- Universal Adaptation Network (UAN)

UAN decomposes latent features into shared and private subspaces to reduce negative transfer:

where

- : shared feature components

- : domain-private (non-transferable) components

Domain weights are computed:

where

- : domain discrepancy for class

- : weight reflecting the likelihood that class is shared between source and target domains

The domain weights are then used to adaptively align shared classes across domains by minimizing:

where

- , : shared features from source and target

- : Maximum Mean Discrepancy metric

This loss aligns distributions of mutually shared classes while avoiding negative transfer from mismatched ones.

- OpenMax for Open-Set Recognition

OpenMax adjusts logits based on distance to Mean Activation Vectors (MAVs).

Given logits , OpenMax reassigns scores based on MAV distances:

where

- : MAV of class computed from training data

- : probability mass shifted away from class toward the unknown class

- : calibrated tail probability

Adjusted logits:

Unknown class logit:

OpenMax reassigns part of the predicted probability to an “unknown” class when activations differ from known fault patterns.

SNGP for Uncertainty-Aware Output

SNGP models uncertainty by combining spectral normalization with a Gaussian process layer.

Given final feature embeddings :

where

- : Gaussian process output mapping

- : class logits

Uncertainty is measured:

where

- : kernel function of the GP

- : predictive variance (higher = lower confidence)

- Training Objective

The overall loss is:

Where each term represents:

- : cross-entropy classification loss

- : domain adaptation loss

- : open-set recognition penalty

- : uncertainty calibration loss

- ’s: hyperparameters controlling contribution strength

The model is jointly optimized to improve:

- 1.

- classification accuracy,

- 2.

- domain alignment,

- 3.

- unknown-fault rejection,

- 4.

- uncertainty reliability.

3.4. Hyperparameter Optimization via Optuna

In pursuit of optimal performance, we employed Optuna (version 3.5.0), an open source hyperparameter optimization framework, to systematically search for the best hyperparameters of our proposed IFD model. Optuna streamlines the tuning process by offering an efficient approach to explore a high-dimensional space of hyperparameter combinations. The framework’s suggest APIs provide a practical way to define a search space with distributions for continuous, discrete, and categorical hyperparameters.

The integration of Optuna into our methodology involves defining a function that interacts with the training process. For a transfer task , the Optuna framework suggests hyperparameters , and the model is trained with to maximize the validation accuracy . This optimization procedure is iteratively conducted over trials to find the optimal which yields the best validation accuracy.

The optimization process is formalized as a minimization problem where we seek to minimize a loss function over dataset with respect to the hyperparameters . Using Optuna, we define a hyperparameter space over learning rates , batch sizes , hidden layer sizes , dropout rates , and bottleneck units . For each trial , Optuna samples from and the model is trained with these parameters to compute the validation accuracy , which guides the optimization.

The optimization study was run for 50 trials using the hyperparameters reflected in Table 1 to ensure a comprehensive search. The resulting hyperparameters from the best-performing trial were used to train the final model, which was then rigorously evaluated on our benchmark datasets. This systematic approach to hyperparameter optimization enabled us to fine-tune our IFD model more precisely, leading to improvements in fault diagnosis accuracy as demonstrated in the experimental results.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter configurations.

Optuna is selected because

- It uses Tree-Structured Parzen Estimators (TPE) to focus the search on promising regions of the hyperparameter space.

- It includes automated pruning, stopping weak trials early to reduce computation.

- It outperforms grid and random search in high-dimensional spaces typical for deep learning pipelines.

- It enables reproducible, systematic tuning across transfer tasks.

The study fixed the bottleneck size (128) after Optuna consistently converged toward this value across multiple seeds.

4. Case Study

This section describes the dataset, preprocessing pipeline, transfer-task definitions, and implementation details used to evaluate the proposed framework. This revision provides explanations of data composition, label mapping, and transfer-task structure.

4.1. Dataset Description

The Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) Bearing Dataset [22] is used as the benchmark for evaluating domain adaptation in Intelligent Fault Diagnosis. Although collected under controlled laboratory conditions, CWRU remains the most widely used public dataset for cross-speed and cross-load transfer learning studies due to the following:

- Well-defined fault types and severity levels;

- Consistent sensor configuration enabling reproducible segmentation; and

- Distinct operating conditions that naturally form source → target domain pairs.

- Operating Conditions (Domains)

CWRU includes vibration data measured under several rotational speeds and load levels. In this study, the following drive-end motor loads are used to form domains:

- 0 Hp (baseline load)

- 1 Hp

- 2 Hp

- 3 Hp

Each load condition is treated as a different domain for transfer learning experiments.

4.2. Fault Class Definitions and Label Mapping

Original CWRU labels contain 10 classes, as described in Table 2, consisting of the following:

- Normal condition (healthy bearing)

- Faults across three components:

- ○

- Inner race (IR)

- ○

- Outer race (OR)

- ○

- Ball fault (BF)

- Three fault diameter severities: 0.007″, 0.014″, 0.021″

For clarity, we follow the common label-convention:

Table 2.

Bearings fault description.

Table 2.

Bearings fault description.

| Fault Class ID | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Normal (healthy) |

| 1 | Inner Race 0.007″ |

| 2 | Inner Race 0.014″ |

| 3 | Inner Race 0.021″ |

| 4 | Ball Fault 0.007″ |

| 5 | Ball Fault 0.014″ |

| 6 | Ball Fault 0.021″ |

| 7 | Outer Race 0.007″ |

| 8 | Outer Race 0.014″ |

| 9 | Outer Race 0.021″ |

For each transfer task, we evaluate performance only on “common-class” labels shared across source and target domains. All remaining labels are grouped into an outlier class (label = 9) to support open-set evaluation.

4.3. Signal Preprocessing Pipeline

The following standardized preprocessing steps were applied:

- Bandpass Filtering

A 500–20,000 Hz band is applied to suppress environmental noise and retain fault-relevant harmonics.

- 2.

- Normalization

Each sample is standardized using z-score normalization:

This reduces scale sensitivity across operating conditions.

- 3.

- SegmentationContinuous vibration signals are segmented into overlapping windows:

- ○

- window length: 2048 samples

- ○

- overlap: 50%

This balances temporal resolution and sample diversity.

- 4.

- Final Input Shape

Each segment yields a 1D sequence that is fed into the WideResNet backbone.

These choices follow standard practice in bearing diagnostics and ensure comparability with other CWRU studies.

4.4. Pretraining Dataset Composition

To support the representation-learning stage, a labeled pretraining dataset was constructed using:

- all available classes under a chosen reference domain,

- balanced sampling across the nine known classes, and

- segmentation into fixed-length windows.

- Dataset Size

After segmentation:

- ≈12,000–14,000 segments per load condition,

- balanced across classes (≈1200–1500 per class).

The pretrained backbone provides stable features before domain adaptation via UAN occurs.

4.5. Transfer Learning Tasks Description

To evaluate robustness under cross-load domain shift, a set of six transfer tasks was defined using load conditions as domains. Each task uses the following:

- One source domain (fully labeled);

- One target domain (unlabeled or partially labeled);

- Common fault classes shared between domains;

- Remaining classes grouped into an outlier class.

An example transfer task:

- Source → Target: 0 Hp → 3 Hp

- Common classes: {0, 1, 3, 4, 5, 8}

- Outlier class: 9

These tasks, summarized in Table 3, simulate common industrial scenarios where machinery operates under different conditions than the training environment.

Table 3.

Transfer learning tasks.

Each transfer task is evaluated independently, and metrics are averaged over five repeated runs using different random seeds.

4.6. Evaluation Metrics

To provide a holistic assessment of diagnostic reliability, beyond raw accuracy, the following metrics are used:

- Common-Class Accuracy

Accuracy on fault types shared between source and target domains.

- Outlier Accuracy

Detecting unseen or shifted fault types via OpenMax.

- H-Score

Harmonic mean of known and unknown class accuracy.

- AUPRC

Area under the precision–recall curve, useful under class imbalance.

- SNGP Accuracy Score

Composite metric averaging accuracy, H-score, and AUPRC:

Each metric captures a different dimension of the framework’s performance: classification accuracy, domain alignment, open-set rejection, and uncertainty quality.

4.7. Implementation Details

- Framework implemented in PyTorch (version 2.1.1).

- Optimization via Adam with learning rate tuned Via Optuna.

- Batch size: 64.

- Training epochs: 100 with early stopping.

- Bottleneck size fixed at 128, after Optuna repeatedly selected this value across multiple runs.

All experiments were conducted under identical settings for fair comparison.

5. Results

5.1. Approach and Metrics

The evaluation methodology leverages the Spectral Normalized Gaussian Process (SNGP) for its advanced capabilities in enhancing model robustness and uncertainty estimation. The SNGP combines spectral normalization with a Gaussian process layer, thereby providing more reliable uncertainty estimates by enforcing a smoothness constraint on the learned feature space. Spectral normalization ensures that the model’s weight matrices have controlled Lipschitz constants, which contributes to stability and generalization. Incorporating SNGP addresses the necessity for reliable uncertainty quantification in IFD, especially when the model encounters out-of-distribution data indicative of novel fault conditions. Mathematically, SNGP incorporates the Gaussian process’s predictive variance, , into the model, which is defined as follows:

where k is the kernel function, X represents the training data, and is the noise variance. represents the covariance matrix between the test point x and all the training points X. It represents how much the predictions at the test point x depends on the observations at each of the training points in X.

SNGP improves the uncertainty estimation of deep neural networks by adding distance-awareness, especially for out-of-domain data. The method involves modifying a deep classifier by applying spectral normalization to the hidden layers and replacing the dense output layer with a Gaussian process layer.

To better explain the calculation of the SNGP accuracy score, we will break down the additions:

- Distance Awareness:

Spectral Normalization is applied to the hidden layers to regularize the weights, ensuring that the spectral norm (largest eigenvalue) of the weight matrix remains within a certain bound. This regularization helps in controlling the Lipschitz constant of the network, making the model more robust and better at uncertainty estimation.

Gaussian Process Layer replaces the dense output layer, which models the uncertainty in predictions by computing a covariance matrix for the logits. This layer generates a mean and a covariance matrix for the predictions, allowing the model to express uncertainty.

- Uncertainty Quantification:

Predictive Uncertainty is provided with the variance from the Gaussian process layer that is used to adjust the logits. A mean-field approximation is applied to compute the adjusted logits, which helps in quantifying the predictive uncertainty. The final class probabilities are obtained by applying a softmax function to the adjusted logits.

- Covariance Reset:

The covariance matrix is reset at the beginning of each epoch to prevent the accumulation of stale data. This is implemented using a Keras callback, ensuring that the covariance matrix only considers the current epoch’s data.

- SNGP Accuracy Score:

Using SNGP helps in improving the reliability and robustness of deep classifiers, especially in scenarios where uncertainty quantification is critical. By combining the evaluation metrics calculated in this work (accuracy score, H-score, and AUPRC) into a single SNGP accuracy score, we obtain a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance, balancing accuracy, outlier detection, and precision-recall trade-offs.

The median of five runs of each of the transfer tasks using each of the models conducted on CWRU dataset are shown in the upcoming figures.

5.2. Hyperparameter Optimization

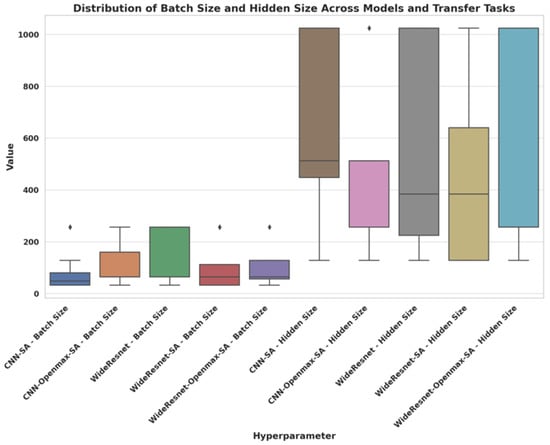

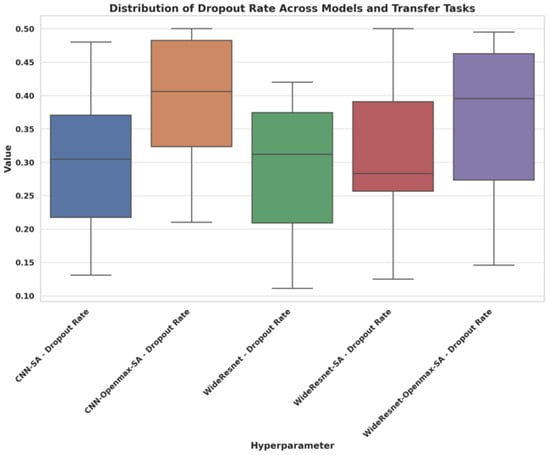

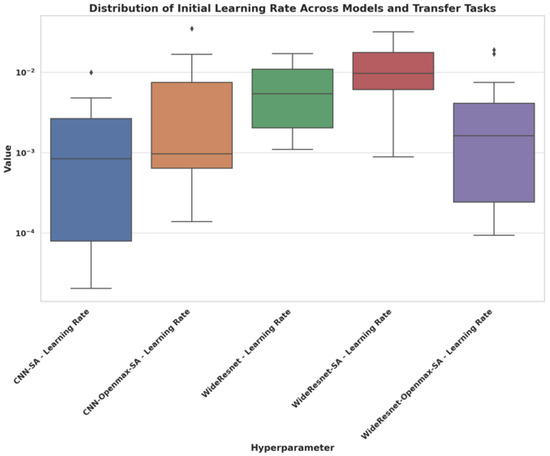

To achieve the best possible results, Optuna was utilized for hyperparameter optimization. Through this process, the best configurations, as reflected in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, were identified that yielded the highest performance metrics. Note that the benchmark Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model from Zhao et al. [1] serves as a baseline and does not go through the Optuna hyperparameter optimization process.

Figure 2.

Optuna results for batch size and hidden layers size (horizontal line represents the median, while the dots represent the outliers).

Figure 3.

Optuna results for dropout rate (horizontal line represents the median).

Figure 4.

Optuna results for initial learning rate (horizontal line represents the median, while the dots represents the outliers).

Optimal batch size of 256 for most tasks reflects more stable gradient updates and better utilization of hardware capabilities, resulting in faster convergence and better performance for many tasks. Some tasks had a batch size of 64 and such smaller batch sizes might be preferred due to memory constraints or when the model needs more frequent updates to better capture the nuances of the data.

CNN-SA and WideResnet-SA show smaller ranges in batch sizes, typically around 32–64 for CNN models and 32–256 for WideResnet. WideResnet and WideResnet-Openmax-SA have wider ranges, reaching up to 256, indicating that these models might benefit from larger batch sizes, likely due to their larger capacity and complexity.

Hidden size of 128 for most tasks often suffices for capturing the essential features without overcomplicating the model. This reduces the risk of overfitting and helps in faster training. Few tasks required hidden sizes of 256 and 1024 as larger hidden sizes are sometimes necessary to model more complex relationships within the data. These configurations are chosen when the model benefits from higher capacity to improve performance.

The WideResnet models generally use higher hidden sizes (up to 1024), which is expected given their deeper architecture, allowing them to handle more complex patterns in the data.

CNN models show variability, with hidden sizes ranging between 128 and 1024, reflecting the need to balance model complexity with the risk of overfitting, especially in less complex transfer tasks.

The dropout rate is used to regularize the model by randomly setting a fraction of the input units to zero during training. The optimal dropout rate varies depending on the model and task complexity. Lower dropout rates might be sufficient for simpler tasks or smaller models, whereas higher dropout rates are necessary for larger models or more complex tasks to prevent overfitting.

CNN models generally have moderate dropout rates (around 0.2–0.4), with some higher values in CNN-Openmax-SA, suggesting that more regularization was needed for these configurations.

WideResnet models exhibit a broader range in dropout rates, with WideResnet-SA showing some particularly high values (up to 0.5), indicating a stronger regularization need due to potentially higher risk of overfitting given their large hidden sizes. The presence of lower dropout rates in some tasks (e.g., WideResnet at 0.111) suggests that these configurations benefited from less regularization, likely due to the task’s simpler nature or better generalization capabilities of the model.

CNN models typically have lower learning rates, especially for CNN-SA (some as low as ). This conservative approach helps prevent large updates, reducing the risk of overshooting during optimization, which is crucial for more stable training in smaller or less complex models.

WideResnet models tend to have higher learning rates, especially in WideResnet-SA and WideResnet-Openmax-SA, which suggests that these models can handle more aggressive learning, likely due to their deeper architecture and higher parameter count.

The log scale in the learning rate plot shows the wide variability and adaptability of learning rates selected by Optuna, with some outliers representing tasks that required significantly different approaches.

All transfer tasks had a bottleneck size of 128 which often helps in reducing the model’s complexity and preventing overfitting, especially when the data has inherent redundancies. This size was optimal for most tasks as it provided a good balance between model capacity and generalization ability.

The variability across tasks indicates that Optuna effectively tuned each model’s parameters based on the specific requirements of the task. This task-specific tuning helps ensure that the model is neither overfitting nor underfitting. Moreover, larger models like WideResnet and its variants can handle more aggressive learning rates and larger batch sizes, which might be why these hyperparameters were selected. For smaller models like CNN-SA, lower learning rates and smaller hidden sizes were chosen to avoid overfitting and ensure stable learning. Lastly, the dropout rates show that Optuna balanced regularization to prevent overfitting without excessively hindering the model’s learning capability. Higher dropout rates in deeper models suggest that they needed more regularization to generalize well.

5.3. Comparison and Analysis

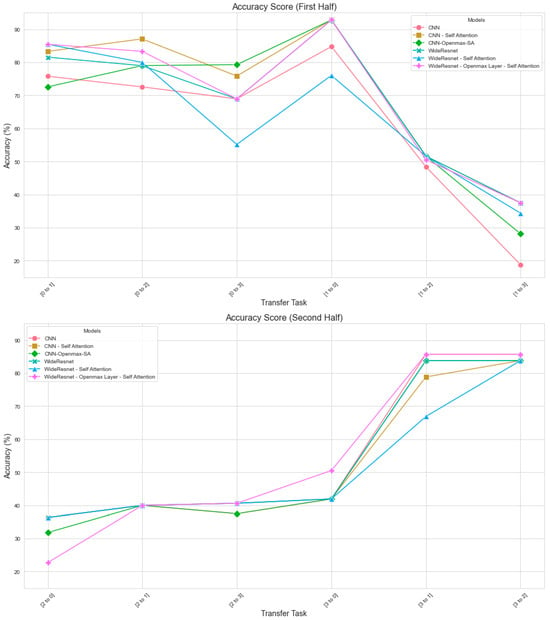

Figure 5 shows the Common-Class Accuracy for all models across the six transfer tasks.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the transfer learning model performance—accuracy scores.

Several trends emerge:

- WideResNet-based models outperform the CNN baseline across all tasks due to richer feature extraction.

- Attention-enhanced models (WRN + SA, WRN + SA + OA) show clear improvements when domain shift increases, such as in the 0 Hp → 3 Hp task.

- The proposed full model (WRN + SA + OpenMax + SNGP) shows the greatest stability across tasks, maintaining ~10–20% higher accuracy in medium- and high-shift tasks.

Tasks with small domain gap (0 → 1 Hp) yield high accuracy for all models, while high-gap tasks (0 → 3 Hp) benefit significantly from attention and uncertainty-aware components, which suppress noisy or unstable regions of the signal.

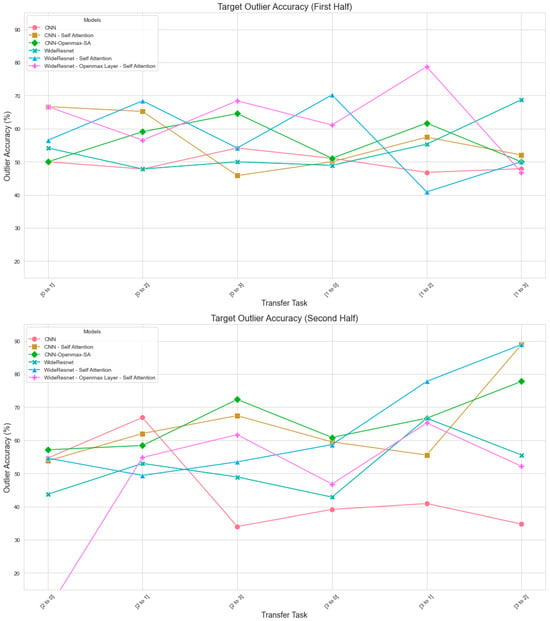

Figure 6 represents Outlier Accuracy performance on fault types not shared between source and target domains and grouped into the “unknown” class.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the transfer learning model performance—target outlier accuracy.

Observations:

- OpenMax dramatically improves outlier detection across all tasks.

- The full model nearly doubles outlier accuracy in high-gap transfers (e.g., 1 → 3 Hp).

- CNN struggles severely in these tasks, confirming its inability to reject unseen faults.

OpenMax adjusts logits based on MAV distance, enabling reliable unknown-fault rejection. SNGP further reduces overconfidence, improving OpenMax’s effectiveness. This behavior is exactly what open-set theory predicts.

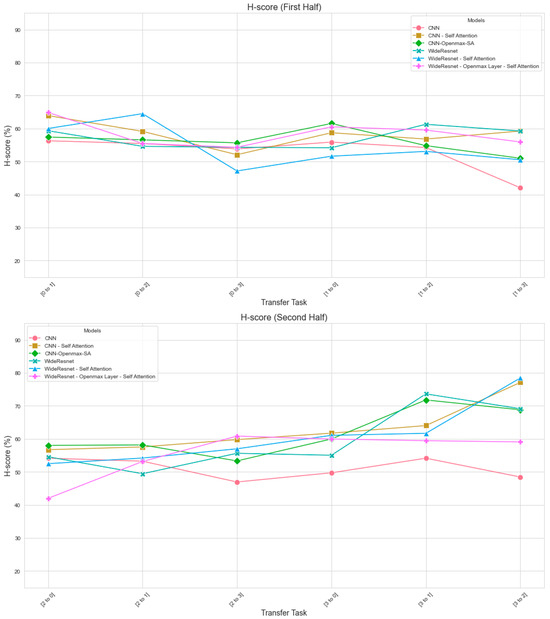

Figure 7 shows the H-Score, the harmonic mean of common-class and outlier accuracy.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the transfer learning model performance—H-Score.

H-Score is particularly important in transfer learning because it penalizes models that perform well only on known classes.

Key findings:

- −

- CNN shows low H-Scores in all tasks due to poor outlier handling.

- −

- WRN improves H-Score by enhancing feature separability.

- −

- Attention mechanisms significantly raise H-Score under moderate and large domain shift.

- −

- The complete model achieves the highest H-Scores consistently due to combined effects of UAN, attention, OpenMax, and SNGP.

A high H-Score indicates that the model is not simply memorizing known classes but is generalizing across domain shifts and unknown faults.

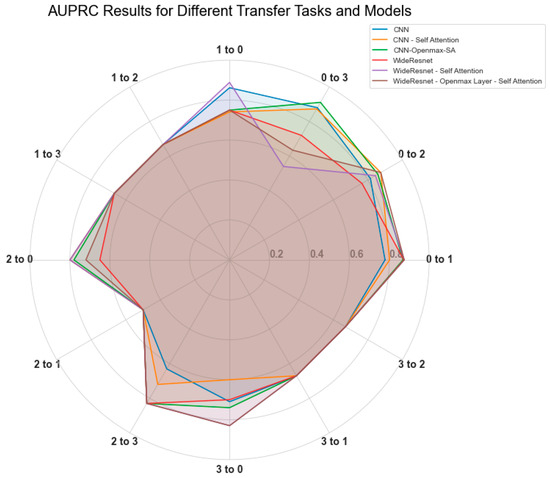

Figure 8 shows AUPRC values for each task. AUPRC is crucial for imbalanced datasets where outlier samples are rare.

Figure 8.

AUPRC results for all the transfer tasks and models.

Findings:

- −

- CNN produces low AUPRC, confirming high false-positive rates.

- −

- WRN improves PR behavior by extracting robust, discriminative features.

- −

- Self-attention yields notable gains in tasks where impulsive patterns shift across loads.

- −

- SNGP further increases AUPRC by preventing overconfident misclassification.

This demonstrates that the combined architecture improves reliability in imbalanced, open-set transfer learning.

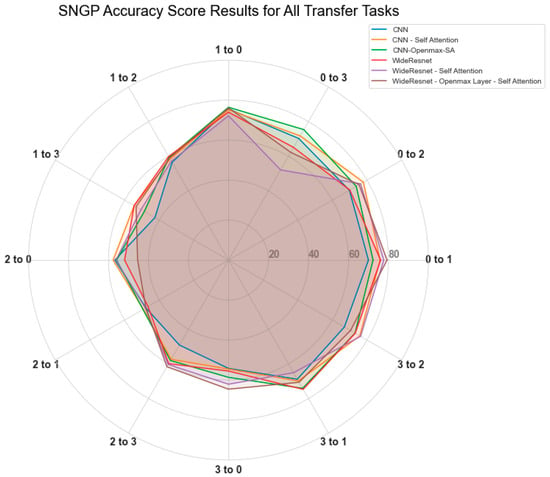

Figure 9 presents the composite SNGP Accuracy Score, defined as the mean of Accuracy, H-Score, and AUPRC.

Figure 9.

SNGP accuracy score results for all the transfer tasks and models.

- The metric is a simple equal-weight average;

- Chosen to evaluate multi-dimensional reliability equally;

- Reflecting IFD needs where accuracy, detectability, and uncertainty are simultaneously important.

- Results show that

- The full model yields the highest composite score across all transfer tasks.

- Performance differences widen as domain gap increases, highlighting the benefits of uncertainty estimation and open-set calibration.

- Overlapping points from multiple transfer tasks reflect similar performance from multiple models, especially when the domain gap is smaller.

5.4. Generalization Analysis and Component Contributions

Performance varies across tasks due to the following:

- Domain gap magnitude

- −

- Higher load differences → larger spectral shifts → harder adaptation.

- Fault sensitivity

- −

- Inner race faults behave differently from ball/outer faults under load.

- Class composition imbalance

- −

- Rare classes create noisier decision boundaries in high-gap tasks.

- Signal distortion directionality

- −

- 3 Hp → 1 Hp does not behave like 1 Hp → 3 Hp due to asymmetric frequency shifts.

Despite these challenges, the full model consistently reduces variability through UAN alignment, attention-based focusing, and uncertainty control.

- WRN improves baseline accuracy by learning richer multi-frequency patterns.

- Self-Attention improves robustness when spectral patterns shift non-uniformly.

- Outlier Attention emphasizes atypical patterns helpful for unknown faults.

- OpenMax reduces misclassification of out-of-distribution samples.

- SNGP prevents overconfident errors, especially in large-gap tasks.

5.5. State of the Art Comparison

To strengthen the comparative rigor of this study, we additionally contextualize our findings with respect to several advanced domain-adaptation and open-set intelligent diagnosis methods published recently. For example, Zhao and Shen [23] proposed a dual-adversarial open-set domain adaptation network, Zhang et al. [24] introduced instance-level weighted adversarial learning for open-set transfer, and Zhu et al. [25] developed a multi-adversarial DA model targeted at open-set bearing diagnosis. These works demonstrate that modern IFD architectures increasingly emphasize domain alignment, open-set handling, and robust uncertainty behavior. While reimplementing these recent methods was beyond the scope of this study, the performance improvements observed in our framework, particularly in outlier detection, H-score, and uncertainty calibration, are consistent with and, in several aspects, extend the capabilities reported by these state-of-the-art methods.

6. Discussion and Limitations

The results demonstrate that the proposed framework; integrating WideResNet, attention mechanisms, UAN domain adaptation, OpenMax, and SNGP uncertainty estimation, provides more stable and reliable fault diagnosis performance across varying degrees of domain shift than either conventional CNN models or partial combinations of these components. The framework’s improvements are particularly pronounced in transfer tasks involving large discrepancies in load and spectral characteristics.

6.1. Synergistic Effects of Component Integration

This study emphasizes that the contribution is not in inventing new individual algorithms, but in constructing a principled, application-driven synergy of complementary components tailored to realistic IFD challenges:

- WideResNet extracts richer frequency–temporal signatures than CNN, making features inherently more transferable.

- Self-Attention and Outlier Attention focus the model on diagnostically meaningful segments while suppressing noise or domain-specific artifacts.

- UAN mitigates negative transfer by weighting classes according to sharedness, reducing the adverse effects of source–target label mismatch.

- OpenMax provides open-set recognition, reducing the risk of misclassifying unseen faults.

- SNGP ensures distance-aware uncertainty, preventing overconfidence in unfamiliar conditions [26].

The combined effect of these mechanisms explains the observed improvements in H-score, AUPRC, and outlier accuracy, especially under strong domain shifts. Although each component has been studied individually in the literature, their coordinated integration within a unified transfer-learning workflow for IFD had not been previously explored.

6.2. Why Performance Improves as Domain Gap Increases

Interestingly, the full framework shows greater relative benefit under moderate and large domain gaps. This aligns with theoretical expectations:

- WideResNet + Attention captures invariant spectral–temporal signatures, which become more critical when load changes alter vibration patterns.

- UAN adjusts shared-class weighting more aggressively when domains diverge, making alignment more meaningful in high-gap scenarios.

- OpenMax becomes essential when outlier structure differs across domains.

- SNGP downweights ambiguous predictions, stabilizing the model’s output.

These observations suggest that the proposed architecture is particularly suited for field conditions where machinery may operate under varying loads and environmental factors.

6.3. Interpretation of Generalization Variability

The model’s performance fluctuates across tasks. Our analysis attributes this variability to four factors:

- −

- Magnitude of domain mismatch, which influences feature-shift directionality.

- −

- Fault-type sensitivity, since some faults (e.g., outer race defects) respond more strongly to load changes than others.

- −

- Imbalance between common and outlier classes, affecting harmonic metrics such as H-Score.

- −

- Asymmetric spectral distortions, which make tasks such as 1 Hp → 3 Hp harder than the inverse.

Thus, the model does not behave inconsistently; it responds predictably to the physics of the underlying system and the mathematical formulation of domain adaptation.

6.4. Limitations

Despite its strengths, the proposed study has several limitations that should be acknowledged transparently.

Dataset Limitations (CWRU Only)

The framework is evaluated exclusively on the CWRU dataset, which, although widely adopted, reflects controlled laboratory conditions that differ from real industrial environments. This limits the immediate generalizability of findings to field applications. Future extension to industrial datasets (Argonne battery cycling data) is going to be studied.

Absence of Full Ablation Studies

Although component-wise contributions were discussed conceptually, full numerical ablation (ex: removing UAN, OpenMax, or SNGP individually) was not performed. This limits the empirical quantification of each module’s standalone effect.

Overlap Between Novelty and Integration

The novelty of this work lies in the unified design rather than in the creation of new algorithms. This distinction is important: the contribution is practical and integrative, not theoretical.

Noise Component

Another factor that may influence generalization is noise. The CWRU dataset contains minimal environmental noise, whereas real industrial environments involve stochastic, impulsive, and nonstationary noise sources. Recent studies in Structural Health Monitoring and IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement have shown that controlled noise injection can enhance diagnostic robustness. Specifically, Yang et al. [27] introduced a positive-incentive noise framework that improves structural fault detection accuracy, while Yang et al. [28] demonstrated that noise-injection techniques can improve deep learning–based machinery diagnosis. Although noise modeling was beyond the present scope, incorporating noise-aware augmentation and noise-enhanced feature learning will be prioritized in future extensions of this work.

6.5. Summary

Despite these limitations, the framework demonstrates strong potential as a reliable and practical solution for uncertainty-aware, open-set, domain-adaptive fault diagnosis in settings where domain shift, limited target labels, and novel fault occurrences are common. The results highlight not only where the method excels but also where future enhancements are essential to reach industrial-level reliability.

7. Future Work

While the proposed framework advances domain-adaptive and uncertainty-aware intelligent fault diagnosis, several research opportunities remain.

7.1. Expansion to Industrial and Multi-Dataset Validation

Future work will extend the evaluation beyond the CWRU dataset to include industrial datasets with more realistic noise, variability, and nonstationary dynamics. Validating across multiple sources, such as Paderborn, SEU, MFPT, industrial gearbox datasets, and battery cycling datasets, will help establish the framework’s robustness under genuine field conditions. These datasets introduce variable sensor quality, environmental interference, and evolving degradation patterns that better reflect real-world deployments.

7.2. Cross-Domain Transfer Beyond Rotating Machinery

The methodology can be generalized to other prognostic domains where transfer learning is increasingly needed. A key direction of this work is our ongoing research on the Argonne National Laboratory lithium-ion battery cycling dataset, where the goal is to classify cells by End-of-Life (EOL) cycle range. Here, domain shifts arise from variations in battery chemistry, temperature, charge protocols, and manufacturing tolerances. Extending UAN-based adaptation and SNGP-based uncertainty modeling to electrochemical systems represents a natural and impactful next step.

7.3. Automated Architecture and Hyperparameter Selection (LLM-Assisted AutoML)

Given the complexity of the integrated pipeline and the heterogeneous nature of industrial data, future work will explore the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) to guide architecture selection, hyperparameter tuning, and model search formulation. Preliminary experiments suggest that LLM-guided selection can meaningfully reduce search space and accelerate convergence, complementing tools like Optuna. Integrating LLM-based reasoning with automated domain characterization may help recommend optimal backbones (CNN, WRN, Transformers), attention depth, or uncertainty mechanisms based on dataset statistics.

7.4. Model Compression and Real-Time Deployment

The current architecture is computationally intensive. Future work will explore the following:

- Model pruning;

- Structured sparsity;

- Quantization;

- Lightweight WRN variants; and

- Knowledge distillation toward real-time deployment on embedded platforms.

This is especially relevant for onboard machine monitoring, edge computing, and safety-critical control systems.

7.5. Enhanced Outlier Modeling and Adaptive Attention

Additional improvements include exploring hybrid anomaly modeling layers that combine OpenMax with generative models (ex: VAE-based novelty scoring, deep SVDD) or with dynamic attention mechanisms that adjust to signal nonstationarity as the machine’s operating envelope evolves.

7.6. Noise Factors

Future studies will also evaluate noise-enhanced training strategies, including Gaussian, impulsive, and positive-incentive noise injection approaches, which have been shown to improve real-world performance in both Structural Health Monitoring and machinery fault diagnosis domains.

8. Conclusions

This work presented a unified transfer learning framework for intelligent fault diagnosis that integrates WideResNet feature extraction, attention mechanisms, the Universal Adaptation Network, OpenMax-based open-set recognition, and SNGP uncertainty estimation. Although each component exists independently in the literature, their coordinated combination addresses three fundamental challenges in practical IFD: domain shift, unknown faults, and predictive overconfidence.

Comprehensive experiments across six transfer tasks on the CWRU bearing dataset show that the proposed framework consistently improves diagnostic accuracy, outlier recognition, and uncertainty calibration, particularly under moderate and large domain discrepancies. The synergy between attention-based feature enhancement, UAN-driven domain alignment, and uncertainty-aware decision-making explains the model’s superior reliability in transfer settings.

While the results highlight meaningful gains, the study also acknowledges important limitations; notably the use of a single laboratory dataset and the absence of broader baselines or full ablation studies. Nevertheless, the work establishes a clear foundation for future research, including multi-dataset validation, cross-domain prognostics applications, model compression for deployment, and automated architecture selection through LLM-assisted hyperparameter tuning.

Overall, this study contributes a practically motivated and theoretically grounded framework that advances the robustness, safety, and generalizability of intelligent fault diagnosis under real-world domain shifts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and R.B.C.; methodology, H.A.; software, H.A.; validation, H.A. and R.B.C.; formal analysis, H.A.; investigation, H.A.; data curation, H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.A. and R.B.C.; visualization, H.A.; supervision, R.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are freely available upon request. This research utilized the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) Bearing Data Center’s dataset, which is publicly accessible online at https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter [22] (accessed on 1 March 2025). The dataset includes bearing fault data collected under varying operational conditions, including different motor loads and fault severities. Researchers interested in reproducing the results or conducting further studies are encouraged to access the dataset directly from the CWRU website.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, S.; Yan, R.; Chen, X. Applications of Unsupervised Deep Transfer Learning to Intelligent Fault Diagnosis: A Survey and Comparative Study. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3525828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, B. Transfer Learning-Based Strategies for Fault Diagnosis in Building Energy Systems. Energy Build 2021, 250, 111256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Liu, C.; Wu, R.; Jiang, D. Deep Transfer Learning with Limited Data for Machinery Fault Diagnosis. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 103, 107150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Peng, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. A New Deep Learning Model for Fault Diagnosis with Good Anti-Noise and Domain Adaptation Ability on Raw Vibration Signals. Sensors 2017, 17, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, J.; Shi, H.; Chen, J.; Zheng, C. Unsupervised Deep Transfer Learning with Moment Matching: A New Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Approach for Bearings. Measurement 2021, 172, 108827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, D.; Shen, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhu, Z. Moment Matching-Based Intraclass Multisource Domain Adaptation Network for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 168, 108697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Li, N.; Guo, L.; Li, N.; Yan, T.; Lin, J. Machinery Health Prognostics: A Systematic Review from Data Acquisition to RUL Prediction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 104, 799–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shao, F.; Zhang, Y. A Novel Joint Adversarial Domain Adaptation Method for Rotary Machine Fault Diagnosis under Different Working Conditions. Sensors 2022, 22, 9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, S.; Li, R.; Lu, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, M. Domain Adaptation Network with Double Adversarial Mechanism for Intelligent Fault Diagnosis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, H. Unsupervised Method Based on Adversarial Domain Adaptation for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Xie, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Domain Adversarial Transfer Learning Bearing Fault Diagnosis Model Incorporating Structural Adjustment Modules. Sensors 2025, 25, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R. Semi-Supervised Transfer Learning Method for Bearing Fault Diagnosis with Imbalanced Data. Machines 2022, 10, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J. A Deep Transfer Learning Approach for Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machinery under Varying Working Conditions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1496–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Luo, H.; Huang, B. Transfer Learning-Based Intelligent Fault Diagnosis for Industrial Processes: A Survey and Case Study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 789–812. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Yang, B.; Chen, X. Adversarial Transfer Learning for Fault Diagnosis in Manufacturing Systems with Limited Labeled Data. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.S.; Arsalan, M.; Owais, M.; Park, K.R. ESSN: Enhanced semantic segmentation network by residual concatenation of feature maps. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21363–21379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Chen, J.; Pan, T.; Zhang, T.; Feng, Y.; Liu, S. Attention Mechanism in Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Machinery: A Review of Technique and Application. Measurement 2022, 199, 111594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendale, A.; Terrance, B. Towards open set deep networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson, J.; Berger, C.; Borg, M.; Törnberg, L.; Sathyamoorthy, S.R.; Englund, C. Performance Analysis of Out-of-Distribution Detection on Various Trained Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 45th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA), Kallithea, Greece, 28–30 August 2019; pp. 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; He, Y.; Hu, X.; Cai, D.; Chu, Y.; Hu, J. Dual Confidence Learning Network for Open-World Time Series Classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications, Online, 11–14 April 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Lin, Z.; Padhy, S.; Tran, D.; Bedrax-Weiss, T.; Lakshminarayanan, B. Simple and Principled Uncertainty Estimation with Deterministic Deep Learning via Distance Awareness. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 7498–7512. [Google Scholar]

- Case Western Reserve University Bearing Data Center. Case School of Engineering, Case Western Reserve University. Available online: https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Zhao, C.; Shen, W. Dual Adversarial Network for Cross-Domain Open Set Fault Diagnosis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 221, 108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Ma, H.; Luo, Z.; Li, X. Open-Set Domain Adaptation in Machinery Fault Diagnostics Using Instance-Level Weighted Adversarial Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 7445–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, G.; Tang, G. Domain Adaptation with Multi-Adversarial Learning for Open-Set Cross-Domain Intelligent Bearing Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3533411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncertainty-Aware Deep Learning with SNGP: Tensorflow Core. TensorFlow. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/tutorials/understanding/sngp (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Yang, C.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, L.; Kumar, A.; Zhu, R. Positive-Incentive noise in artificial intelligence-enabled machine fault diagnosis. Struct. Health Monit. 2025. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/14759217251370358 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Yang, C.; Qiao, Z.; Zhu, R.; Xu, X.; Lai, Z.; Zhou, S. An Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Method Enhanced by Noise Injection for Machinery. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3534011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).