Abstract

In this paper, the inductance of a sensorless PMSM (Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor) drive system equipped with a periodic load torque compensator based on a wavelet denoising and least-order observer with time-delay compensation is estimated in real-time. In a sensorless PMSM system with constant load torque, the magnetically saturated inductance value remains constant. This constant inductance error causes minor performance degradation, such as a constant rotor position estimation error and non-optimal torque current, but it does not introduce a speed estimation error. Conversely, in a sensorless PMSM motor system subjected to periodic load torque, the magnetically saturated inductance error fluctuates periodically. This fluctuation leads to periodic variations in both the estimated position error and the speed error, ultimately degrading the load torque compensation performance. This paper applies the maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion for the optimal selection of the mother wavelet in the wavelet transform to remove the motor signal noise and achieve more accurate inductance estimation. Additionally, the coherence and correlation theory is proposed to address the time delay in the least-order observer and improve the time delay. A self-saturation compensation method is also proposed to minimize periodic speed fluctuations and improve control accuracy through inductance parameter estimation. Finally, experiments were conducted on a sensorless PMSM drive system to verify the inductance estimation performance and validate the effectiveness of vibration reduction.

1. Introduction

Electrical motors have played a crucial role in technological advancements for over a century. As technological progress accelerates, the applications of electrical motors are rapidly expanding. Advances in modern digital computers, along with recent developments in power electronics and semiconductor devices, have made groundbreaking contributions to the design and control of electric motors. Among them, permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) are widely used due to their high efficiency and lightweight characteristics, in applications ranging from household appliances to automotive drives. Field-Oriented Control (FOC) is primarily employed for high-performance operation in PMSM drive systems, which necessitates real-time knowledge of the rotor’s position. However, practical issues such as mounting constraints, high sensor cost, and the risk of catastrophic control failure in the event of a fault have spurred intensive research into sensorless control methods that eliminate the need for a direct position sensor. Sensorless control techniques mainly fall into two categories: current model-based methods and extended back-EMF-based methods. Recently, the latter has been increasingly applied due to the use of Arctan calculations in microprocessors, which eliminate the limitations of input variables and provide fast tracking ability [1,2,3,4].

When the external load torque is constant, the rotor position estimation error is constant because the torque component current and inductance parameter error due to magnetic saturation are constant. This constant rotor position error has a negligible effect on the estimation speed error. However, when periodic load torque occurs, the inductance parameters also undergo periodic fluctuations, resulting in periodic fluctuation components in both the position and speed estimation errors. That is, in environments with a large magnitude and high fluctuation rate of the load torque, rather than the ideal situation of a small and stable load torque, the change in inductance increases, leading to larger estimation position errors and a degradation of the overall motor system’s control precision. Particularly in environments directly exposed to external vibrations and loads, such as motors near engines and powertrain systems, household pumps, and compressors, the control performance can rapidly deteriorate [2].

Analyzing the external load pattern and applying an appropriate compensation current can mitigate the effects of load torque fluctuation. However, applying this method may increase the ripple in the estimated speed due to the magnetic saturation of the inductance as the amount of compensation current increases. If appropriate compensation control considering this is not performed, it can lead to mechanical instability and NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) issues in the entire motor system. Therefore, the precision of sensorless control can be improved by accurately estimating the actual inductance magnitude and performing real-time control in a closed-loop manner [5,6].

Previously, attempts were made to estimate the magnitude of the inductance using mathematical model-based observers to compensate for the magnetic saturation problem caused by inductance variation. However, such approaches were sensitive to the back-EMF (electromotive force constant) and drive output voltage fluctuations because they used the estimated rotor position and speed information during sensorless control. Furthermore, even with an appropriate back-EMF constant, when exposed to periodic load torque fluctuations, the estimated inductance faced problems such as noise and time delay, which could degrade system stability and speed estimation performance [7,8,9].

Wavelet transform is increasingly being used for modeling, analysis, and control of electric motor drives in high-performance applications. Unlike traditional Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), wavelet transform has been implemented in several technologies for high-performance control and diagnostics of systems like Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM) drives, Brushless DC motor drives, and induction motor drives. Chaplais et al. [10] developed an online wavelet-based noise reduction algorithm for a 3-phase PM Brushless DC motor drive used in a reaction wheel system. This wavelet-based algorithm was implemented to denoise the feedback signal of the Brushless DC motor drive. Khorbottly et al. [11] developed a wavelet-based real-time noise reduction technique implemented for position sensorless control of Switched Reluctance Motor (SRM) drive systems. Song et al. [12] proposed a Wavelet Neural Network (WNN) based speed estimation method for sensorless control of PM Brushless DC (BLDC) motor drives. However, the drive system integrated with the WNN-based speed estimator showed unsatisfactory performance during high-speed operation of the Brushless DC motor due to the offline training of the network. Khan et al. [13] developed and implemented a hybrid Wavelet Packet Transform (WPT) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) based fault diagnosis and protection technique for inverter-fed IPM synchronous motors. The stator currents of various fault and healthy conditions of IPMSM were pre-processed by WPT. The second-level WPT coefficients of the stator current were used as inputs to a 3-layer feedforward neural network. Additionally, Khan et al. [14] proposed a new wavelet-based multi-resolution PID controller for precise speed control of IPMSM drives under system uncertainties. The proposed controller is based on the multi-resolution decomposition of speed error between the command and actual speed using Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT). Control signals were generated using wavelet transform coefficients of speed error at various frequency sub-bands of the DWT tree. Based on the above discussions, it can be concluded that there is a trend of recent research activities focusing on the application of wavelet transform in motor drives.

Selection of an appropriate wavelet and the optimal decomposition level are important criteria in signal denoising. A major challenge when using wavelet transforms is choosing the most suitable mother wavelet for a given task, because different mother wavelets applied to the same signal can yield different results. To judge the similarity between a signal and a mother wavelet more precisely, quantitative approaches have been proposed in recent years. Minimum Description Length (MDL) was proposed by N. Saito [15] as a criterion for selecting the optimal mother wavelet for noise suppression and signal compression. MDL theory states that, among a set of candidate models, the best model is the one that provides the shortest combined description of the data and the model itself. Hamid et al. [16] applied MDL as a guideline for selecting the most suitable mother wavelet to compress power disturbance data. Using the MDL criterion, Symlet7 was found to outperform other mother wavelets for most power disturbance signals. Khan et al. [14] applied the MDL criterion in a study on protection of three-phase interior permanent magnet synchronous motors and selected the most suitable mother wavelet for that analysis; db3 was chosen as the mother wavelet for the wavelet packet transform. In addition, the maximum cross-correlation criterion has been applied for denoising ECG signals. Singh and Tiwari [17] investigated ECG denoising using db8, which was selected according to the maximum correlation criterion. Yan [18] proposed the energy-to-Shannon-entropy ratio criterion and the MinMax information criterion to select the most suitable mother wavelet for bearing fault detection. The energy-to-Shannon-entropy ratio criterion refers to maximizing the amount of energy while minimizing the Shannon entropy of the corresponding wavelet coefficients. The MinMax information criterion considers a combination of criteria including minimum joint entropy, minimum conditional entropy, minimum elastic entropy, maximum mutual information, and maximum correlation coefficient. Using the energy-to-Shannon entropy ratio and the MinMax information criteria, reverse biorthogonal 5.5 was chosen as the mother wavelet. Kankar et al. [19] also applied the maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion for bearing fault detection. For thresholding approaches, all wavelets within each wavelet family must be considered to test denoising performance. Therefore, performance-based wavelet selection methods are inefficient and time-consuming when optimizing between selecting lower vanishing moments and performance measures. To avoid this cumbersome procedure, this paper uses the maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion as the method for selecting the optimal mother wavelet for wavelet denoising.

This paper investigates a real-time inductance estimation method for a sensorless PMSM drive based on wavelet denoising and a least-order observer to minimize rotor position and speed errors and compensate for external periodic load-torque variations. To reduce uncertainty caused by flux saturation and improve real-time control performance, motor currents are filtered using a wavelet transformation. The motor inductance is then estimated using a least-order observer that incorporates coherence- and correlation-based time-delay estimation to reduce time delay, and a compensation control for flux-saturation is applied. The proposed least-order observer with coherence- and correlation-based time-delay estimation aims to shorten the delay of observer and thereby improve the accuracy of the estimated inductance. To validate the flux saturation compensation method and assess control performance, a sensorless PMSM drive system is modeled, and experiments are conducted. Under periodic load-torque conditions, applying the estimated inductance from the proposed method for compensation control is shown to reduce sensorless speed estimation errors and to improve the system’s frequency response characteristics and NVH performance.

2. Magnetic Saturation of Sensorless Control

Generally, the voltage equations in the dq synchronous frame for vector control of a PMSM are given by (1),

where and denote the stator resistance, the back-EMF constant, and the differential operator, respectively. are the d- and q-axis inductances, are the stator voltages, and and are the stator currents in the dq synchronous reference frame. Ignoring the difference between the estimated rotor speed and the actual rotor speed, (1) can be transformed into the -axes using the extended back-EMF representation.

The voltage equation can then be written as [2]

where , , and . Here and are the stator voltages, and are the stator currents, and and are the extended back-EMFs in the estimated synchronous reference frame, which account for the rotor position error.

Using and , the rotor position error can be determined.

The estimated speed, denoted as , can be acquired through a PI controller by using the estimated rotor position error, , as the input. To reduce noise, a low-pass filter is applied. Additionally, the estimated rotor position, , can be calculated by integrating the estimated speed.

Ensuring precise sensorless control requires accurate identification of parameters such as resistance and inductance, as described in (2). In systems subjected to significant periodic loads, such as pumps or compressors, magnetic saturation causes a mismatch between the actual q-axis inductance and its estimated value , which in turn introduces errors in rotor position estimation.

To compensate for these deviations caused by magnetic saturation, (2) can be reformulated in terms of the extended back-EMF components :

where , and . Here, and represent the errors in the d- and q-axis inductances, respectively, defined as the difference between the actual inductance and its estimated value. In practical systems, and are affected by and , which incorporate the inductance errors. As a result, both rotor position error and speed ripple increase.

Consequently, since the dominant term contributing to position estimation error is , compensating for variations in the q-axis inductance which is the primary parameter affected by magnetic saturation can effectively reduce rotor position error and mitigate speed ripple [2].

3. Real-Time Inductance Estimation Using Wavelet Denoising and Least-Order Observer with Time-Delay Compensation

3.1. Signal Denoising by Discrete Wavelet Transform

When wavelet transform is applied to signal processing, the general procedure is as follows. First, the signal is decomposed using the wavelet transform to obtain the wavelet coefficients. Then, depending on the requirements, the wavelet coefficients are processed. Finally, the signal is reconstructed through the inverse wavelet transform [2].

The application of wavelet transform in signal denoising can be described as follows. When the noise is stationary, an empirically recorded signal corrupted by additive noise can be expressed as [20]

where is the noisy signal, is the true noise-free signal, is an independent normal random signal, and represents the noise intensity in . The noise is generally modeled as a stationary, independent, zero-mean white Gaussian variable.

The objective of denoising is to reconstruct the original signal from a finite set of values of , without assuming any specific structure of the signal. A common approach to denoising models the noise as a high-frequency component superimposed on the original signal. Several wavelet-based denoising techniques have been proposed, among which thresholding is a simple and effective method. In practice, the fundamental principle of wavelet denoising for extracting the ideal components of a signal corrupted by noise lies in estimating the noise level. The estimated noise level is then used to set a threshold for the small coefficients, which are assumed to correspond to noise.

The signal denoising procedure based on the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) consists of three stages: signal decomposition, thresholding, and signal reconstruction. Orthogonal DWT is particularly well suited for denoising, since the decomposition is additive; consequently, the analysis of the noisy signal is equivalent to the sum of the analyses of the true signal and the additive noise. Moreover, when the noise is assumed to be white, the detail coefficients at all scales essentially correspond to white noise with the same variance.

The core of wavelet denoising lies in selecting an appropriate threshold. In general, the threshold is determined by the noise intensity , as defined in (5). Once the noise intensity has been estimated, various mathematical models can be employed to determine the threshold value. Thresholding is typically applied in one of the following two ways. Let denote the original wavelet coefficient, the thresholded coefficient, and T the threshold value. Define the indicator function as [20,21,22]

(1) Hard Thresholding: In this method, wavelet coefficients with absolute values below the threshold are set to zero. This approach leaves coefficients larger than the threshold unaffected, which may cause instability and sensitivity to small changes in the signal.

(2) Soft Thresholding: In this method, the retained wavelet coefficients are reduced by the threshold value:

3.2. Mother Wavelet Selection Using Maximum Energy-to-Shannon Entropy Criterion

The mother wavelet serves as the basis for analyzing a given signal in wavelet transform. Since the results obtained from the wavelet transform are influenced by the choice of the mother wavelet, selecting an optimal one is of critical importance. In this study, the energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion, which is relatively simple to compute and widely used for condition monitoring and fault diagnosis, was adopted.

The energy content of a signal is a measure that uniquely characterizes the signal. The amount of energy in a continuous-time signal can be calculated as [18]

When the signal is represented by discrete samples , where , the signal energy can be expressed as

Here, denotes the length of the signal expressed as the number of data points, and represents the signal amplitude.

The energy content of a signal can be calculated using its wavelet coefficients and is expressed as

This indicates that the energy associated with a specific scaling parameter s can be written as

For sampled data, the energy can be expressed as

where is the number of wavelet coefficients and denotes the wavelet coefficient. If the signal contains a dominant frequency component corresponding to a specific scale , the wavelet coefficients at that scale will exhibit relatively high magnitudes at the time when this frequency component occurs. Consequently, applying the wavelet transform to a signal enables the extraction of the energy associated with such frequency components.

The energy distribution of wavelet coefficients can be quantitatively described using Shannon entropy. The Shannon entropy of a signal is defined as

where represents the energy probability distribution of the wavelet coefficients and is given by

Since the criterion for selecting a mother wavelet aims at maximization, the objective is to extract the maximum possible energy from the analyzed signal while simultaneously minimizing the Shannon entropy of the corresponding wavelet coefficients. Accordingly, the energy-to-Shannon entropy ratio is defined as

A larger value of indicates that the corresponding mother wavelet is more suitable for signal analysis.

3.3. Proposed Least-Order Observer with Coherence- and Correlation-Based Time-Delay Compensation

In conventional model-based compensation methods for addressing flux saturation errors, the PMSM voltage equations are typically expressed in terms of inductance. The inductance is then predicted through an observer and fed back to compensate for flux saturation. For observer modeling, the input and output variables of the target control system are defined, and specific internal parameters are indirectly estimated based on a mathematical model [3].

When the system is represented by a state equation with two states, the state-space model can be expressed in matrix form as follows:

where and denote the variables to be estimated, u represents the input of the state equation, and is the output. and are weighting constants associated with each state variable, denotes the observer gain, and the symbol ^ indicates estimated variables.

In a sensorless system, since the variable to be estimated for flux saturation compensation is the inductance, the state can be considered measurable, and only a single state needs to be estimated. Thus, the observer can be configured as a least-order observer. Compared to a full-order observer, the least-order observer offers the advantage of a simpler structure, as fewer states need to be estimated.

By reformulating (17) such that becomes the state to be estimated, the dynamics of the estimated state can be expressed as follows, considering the error between the estimated and actual parameters:

The derivative of estimation error can then be derived as

Here, if and satisfy the observability condition, the placement of the observer poles can be determined according to the design of the observer gain . Therefore, must be selected such that the system remains stable, ensuring that the estimation error converges to zero.

To eliminate the derivative term in (19) and simplify the expression, a new parameter is introduced, redefining as

Substituting (20) into (19) and rearranging yields

The value of the parameter can be obtained by applying an integrator to the result of (21). Finally, substituting into (20) allows the estimation of the target variable .

For sensorless PMSM drive model-based inductance estimation, by applying the d-axis voltage equation from (1) to (17), a state-space model for estimating the q-axis inductance which primarily affects flux saturation can be expressed as follows:

where corresponds to the observable variable , which represents the output of the state equation; corresponds to the variable , which represents the -axis inductance to be estimated; and corresponds to the input variable of the state equation, representing the -axis voltage. In addition, each component of the state matrix, serves as weighting constants of the state equation, is represented as , , , and in (17).

Using (20) and (21), the derivative of the parameter can be expressed as

From (24), the parameter can be approximated as

Therefore, by substituting (23) into (25), the estimated q-axis inductance, which is the observer’s target variable, is obtained as

If this estimation equation is directly applied, the derivative term introduces significant noise and degrades the harmonic characteristics. Therefore, as expressed in (27), introducing a first-order low-pass filter minimizes the influence of the pole term in the numerator, thereby improving the noise performance of the estimated parameter. Furthermore, by adding the component obtained by multiplying the observer gain with the state equation output variable , the offset and gain of the estimated parameter can be adjusted, leading to a reduction in system error.

where denotes the time constant of the first-order low-pass filter.

However, the additional lag components and signal distortion introduced by the low-pass filter and the associated computational process increase the time delay, thereby degrading the accuracy of the real-time control loop. In particular, when periodic load signals or overloads are applied due to external conditions, cumulative errors caused by the time delay occur, leading to deviations from the actual values.

To address these issues, this study applies a time-delay compensation method based on coherence and correlation slope to the least-order observer. This approach aims to improve the accuracy of parameter estimation while maintaining the simplicity and efficiency of the observer structure.

When the original reference signal is defined as

the signal estimated through the observer, , exhibits distortion along with a delay of d steps and can be expressed as

where is the fundamental frequency, is the sampling period, represents the actual delay in steps, and denotes measurement noise and DC offset. By accurately estimating the time delay and applying time-delay compensation, the performance of the observer-based inductance estimation can be significantly improved.

The target signal was selected as a periodic signal with at least cycles to ensure estimation accuracy and averaging. The delayed signal can be defined as a set of segments as follows:

The magnitude-squared coherence between the original signal and the delay-compensated signal is calculated as [23]

where is the cross-spectral density, and and are the auto-spectral densities of and , respectively.

For each segment , by varying the delay compensation step , the candidate step that maximizes the coherence for each segment is determined as

While applying coherence alone can reveal the linear relationship between two signals in specific frequency bands, it represents a statistical average over frequency and does not capture noise, nonlinear distortion, or local variations in the time domain. Therefore, to compensate not only for frequency-domain linearity but also for signal nonlinearity and real-time degradation, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the two signals in the time domain is analyzed and corrected, as expressed in [24]

To further enhance the sensitivity of signal alignment and improve the precision of time-delay estimation, the slope (first derivative) of the correlation curve is estimated to identify the inflection point, as defined by

From this analysis, the step that minimizes the average slope of the correlation curve for each segment is selected:

The reference step is obtained by averaging the results across all segments:

Finally, among the coherence-based candidate steps, the value closest to the average Pearson correlation step is selected as the final estimated delay step . Based on (36), the estimated time delay is then determined as:

Thus, by first setting a candidate region using coherence and then refining the estimate using the slope of the Pearson correlation to ensure robustness against noise and distortion, the precision of the time-delay estimation is improved.

Based on the previously estimated time-delay information, a time-delay compensator including the feedback path was implemented to correct the observer output. By utilizing the dynamic model of the observer, the output is advanced by the estimated delay , enabling a real-time estimation model. This can be expressed as

where is the transfer function of the original model, and represents the delay compensation term.

Consequently, the final model output including the time-delay compensator can be expressed in the time domain as

By compensating the observer signal by , becomes time-aligned with the original signal . As a result, the compensated output estimates the original signal instantaneously, significantly reducing estimation errors caused by the observer output delay.

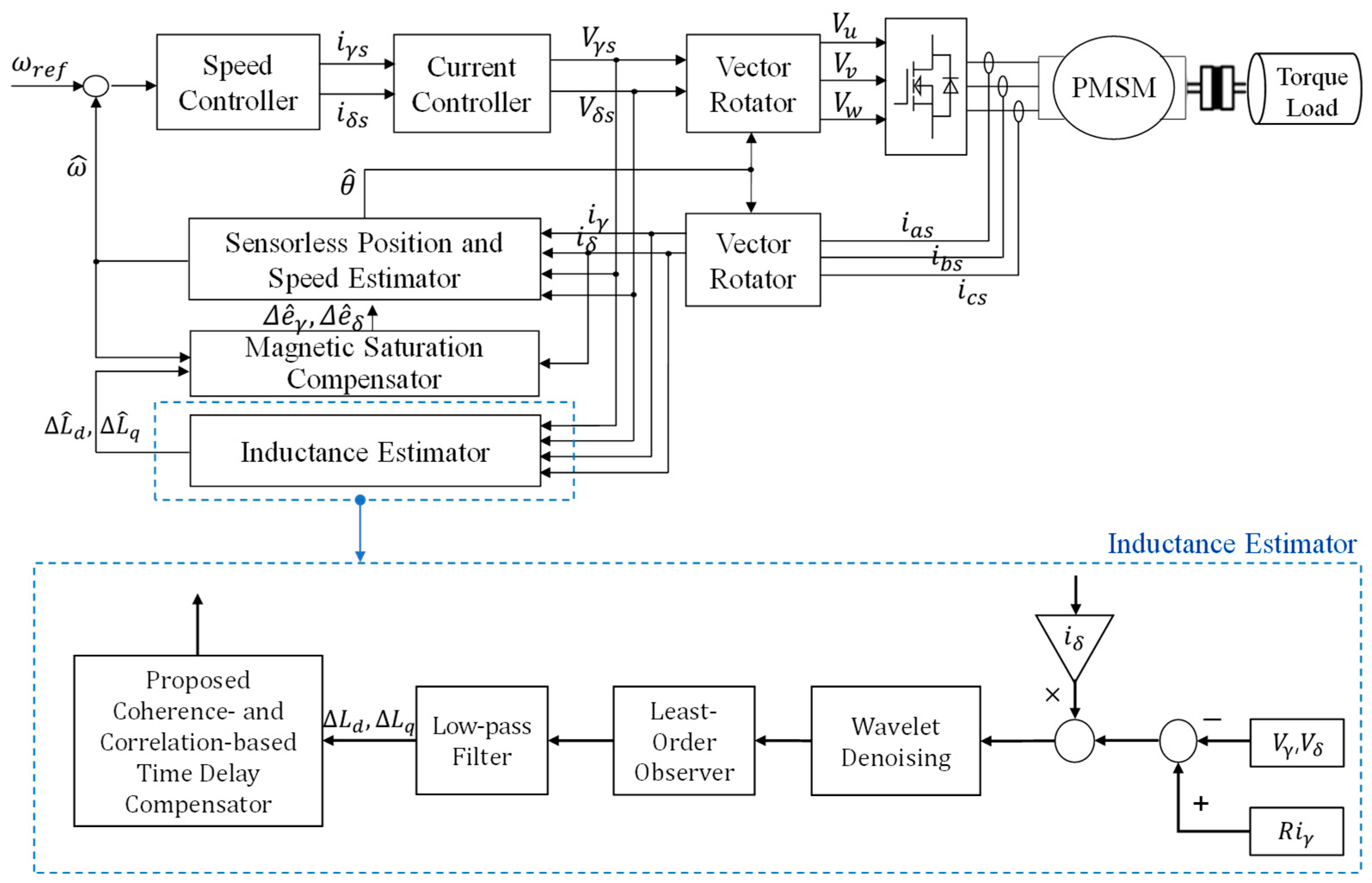

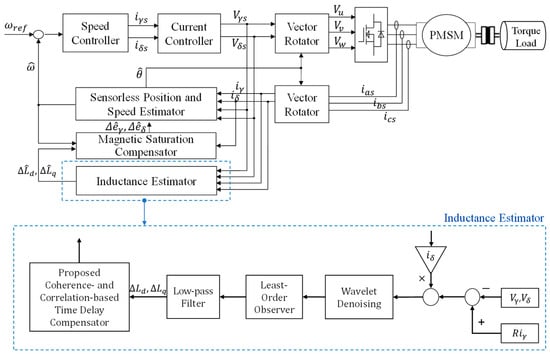

Based on the algorithms presented in this chapter, the overall block diagram of the flux-saturation-compensated sensorless PMSM drive system designed to enhance inductance estimation performance is illustrated in Figure 1. In the inductance estimator, wavelet denoising selected according to the maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion is employed to minimize distortions in the input signal of the least-order observer. In addition, a coherence- and correlation-based real-time delay compensator is applied to correct the time delay and offset errors in the observer output signal. Through this approach, inductance can be estimated with high accuracy, and the estimated flux value is fed back to suppress speed ripple and vibration.

Figure 1.

Overall block diagram of the flux-saturation-compensated sensorless PMSM drive system.

4. Experiment Results

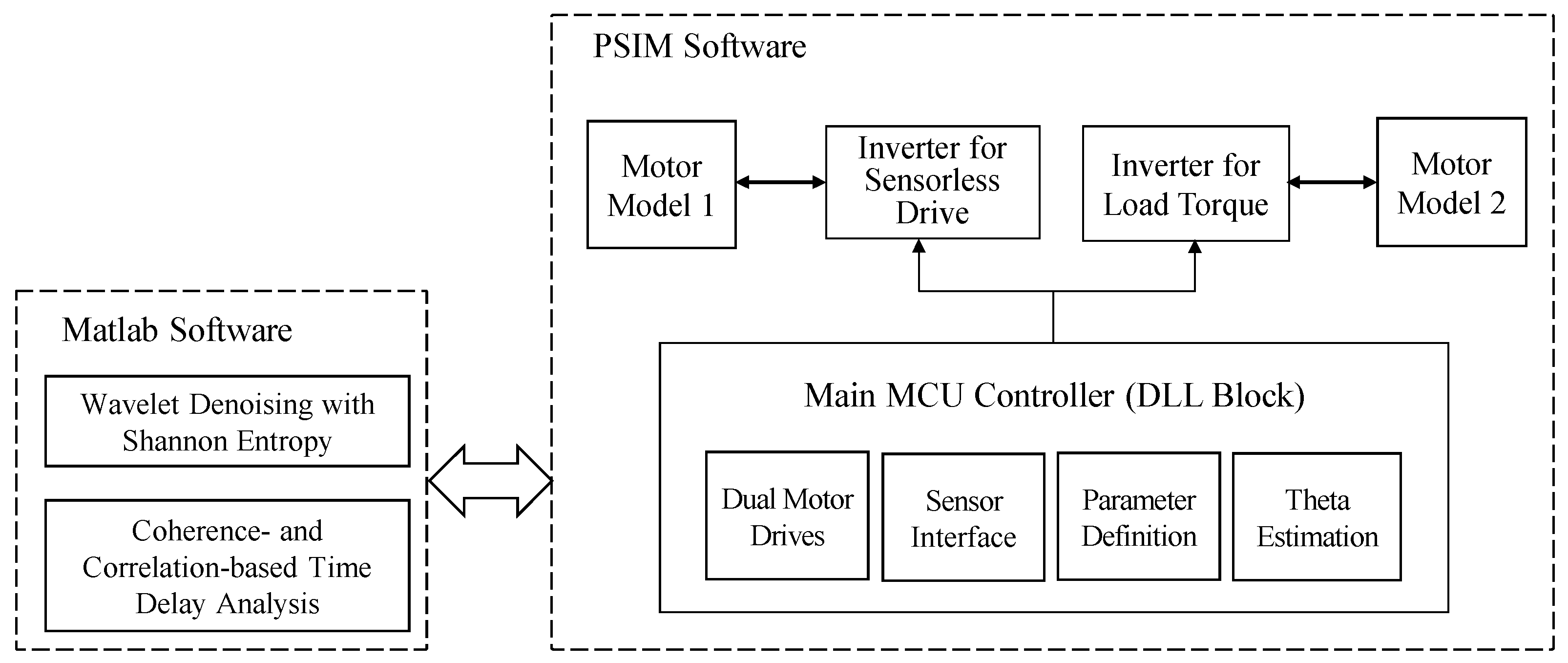

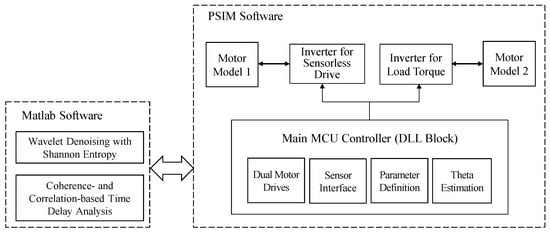

Simulations were carried out using PSIM software to analyze and compare the inductance estimation performance and speed ripple characteristics according to inductance estimation and compensation methods under flux-saturation conditions in sensorless PMSM control. As shown in the control simulation block diagram in Figure 2, the main MCU-based controller equivalent to the actual dual-motor drive system was implemented. The dual motors share identical specifications: Motor model 1 corresponds to the machine employed for the sensorless drive, while motor model 2 serves as the load-torque generation machine. The controller was modeled and compiled in C language using the General DLL block in PSIM, generating a DLL file for co-simulation. In addition, specific signal-processing functions, such as wavelet denoising and time delay analysis, were interfaced with MATLAB R2024b for data processing and system integration.

Figure 2.

Detailed Block Diagram for the Control Simulation Environment.

The main parameters of the PMSM applied to the simulation and experiments are presented as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Motor parameters.

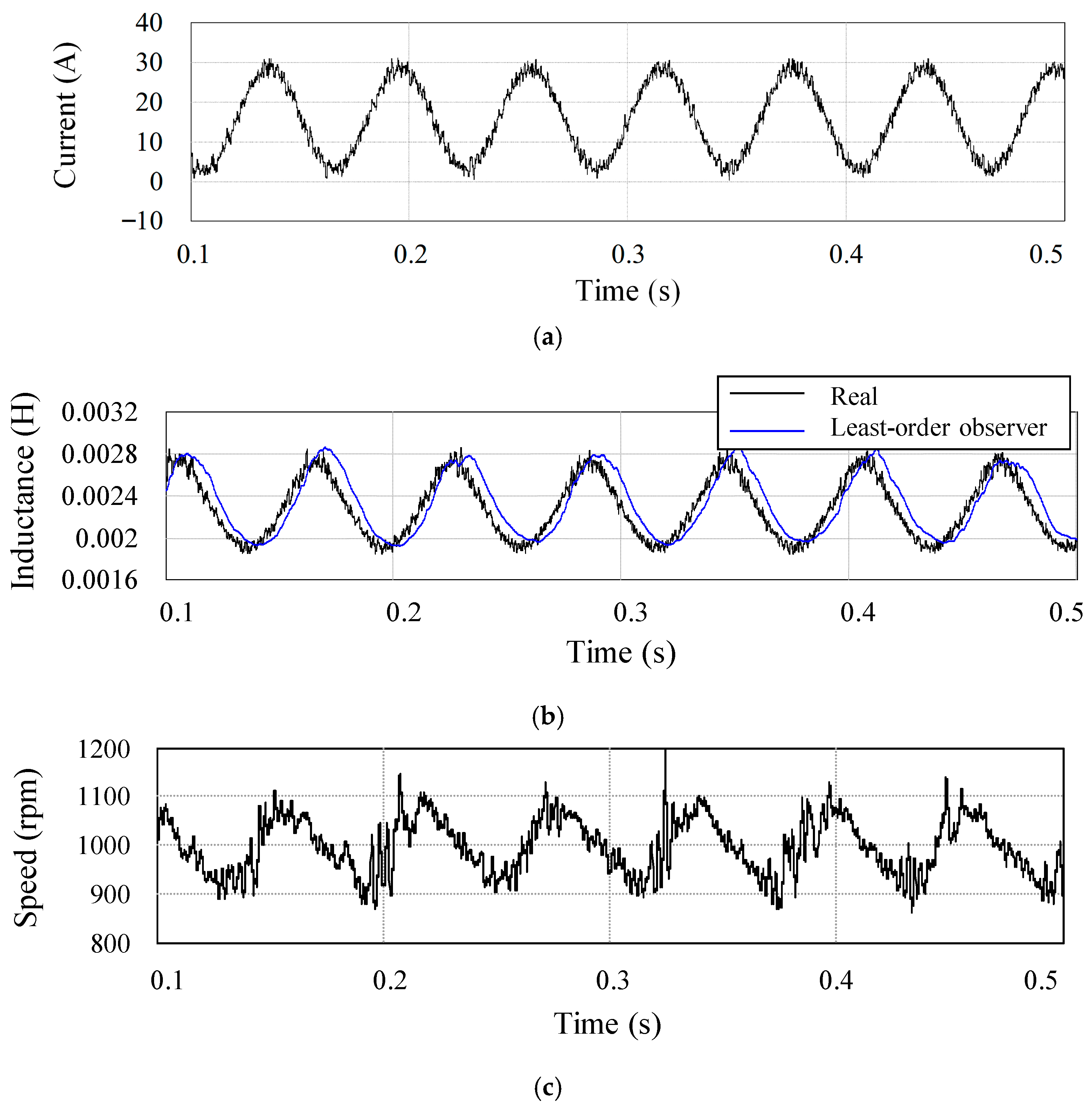

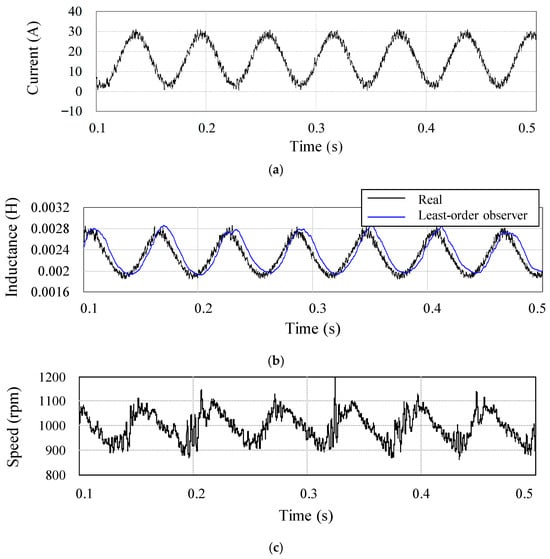

Figure 3 shows the simulation results of the inductance magnitude and the corresponding speed when the motor is operated at 1000 rpm (16.67 Hz) under load-torque compensation current. When the load-torque compensation current along the q-axis varies from 0 A to 30 A due to external periodic loads, as shown in Figure 3a, the real inductance continuously changes due to flux saturation, as indicated by the black line in Figure 3b. The blue line in Figure 3b represents the inductance estimated using the conventional least-order observer model, which is used to compensate for the inductance variation caused by flux saturation. In this least-order observer-based inductance estimation, the influence of the low-pass filter and integration introduces time delay and DC offset, increasing the uncertainty of the parameter estimation. If this varying inductance component is not properly estimated and compensated, the estimated speed exhibits significant ripples exceeding ±100 rpm, accounting for more than 10% of the speed reference, as shown in Figure 3c.

Figure 3.

Simulation results when the load fluctuated at 16.7 Hz for (a) -axis current, (b) -axis inductance, and (c) estimated speed.

The primary cause of the issues is, as previously described, the distortion of the input signal to the conventional least-order observer and the time delay in its output. To minimize the distortion of the observer input signal, a wavelet filter was applied as a preprocessing stage. Wavelet denoising was performed on the collected voltage and current data using the maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion to select the optimal mother wavelet function. The candidate mother wavelets tested for this purpose included Daubechies, Symlet, Coiflet, and Biorthogonal wavelets. In addition, considering the signal’s noise level for the selected mother wavelet, the decomposition level was set to 4 for current and 8 for voltage.

Table 2 presents the set of candidate mother wavelets and the mother wavelets selected based on the maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion. For each candidate, the energy and Shannon entropy of the motor signals were computed, and the corresponding maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy ratio was evaluated. The selected mother wavelets, db1 as a Daubechies variant and Sym4 as a Symlet variant, were subsequently employed for real-time noise filtering of current and voltage signals in the sensorless PMSM drive system.

Table 2.

Selection of mother wavelets for currents and voltage.

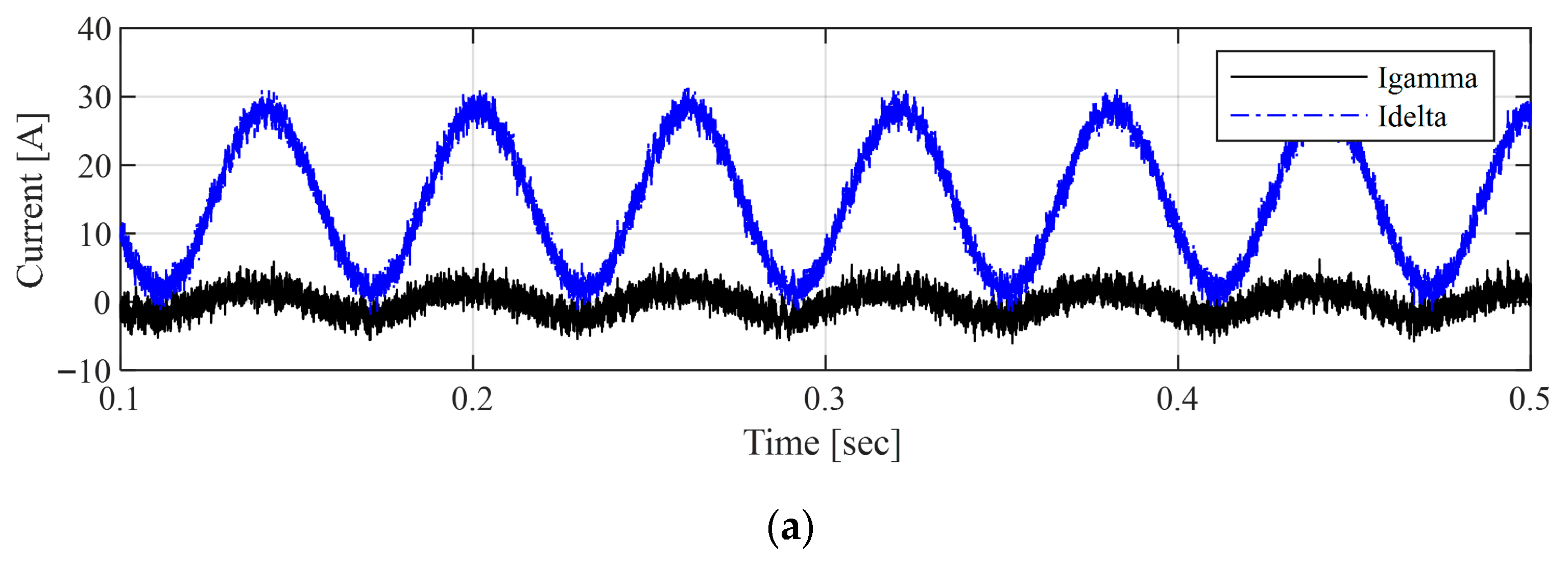

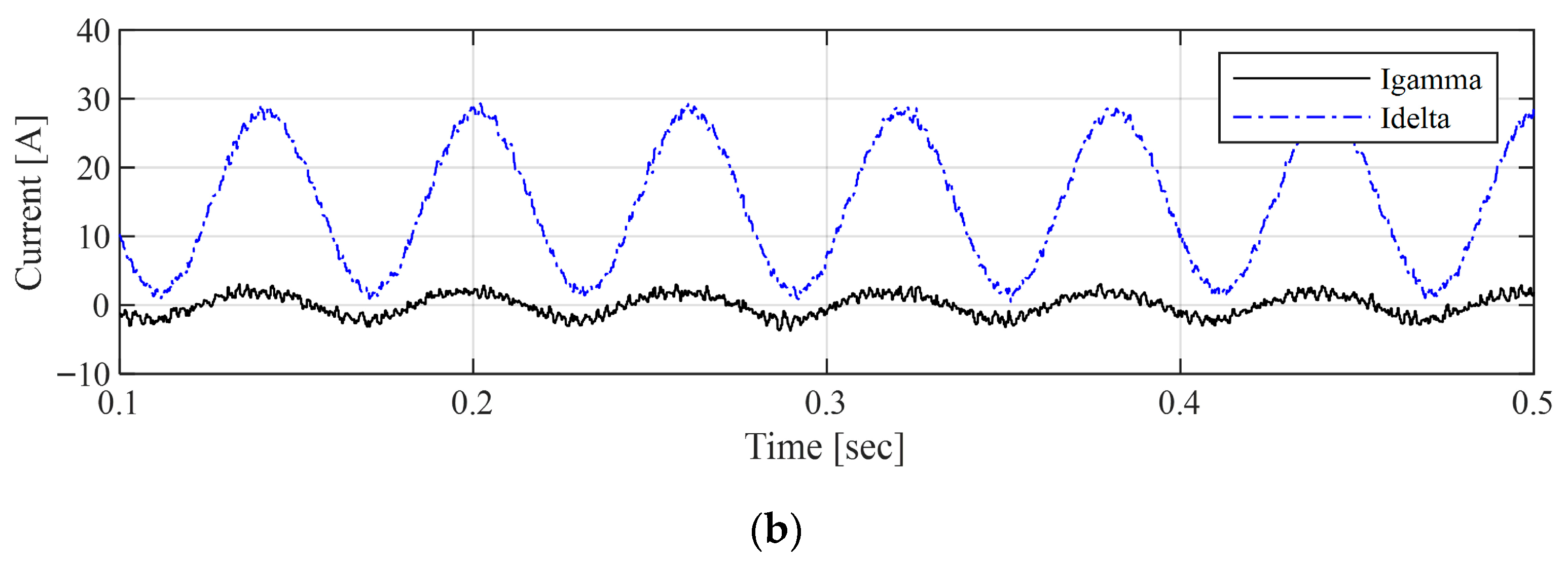

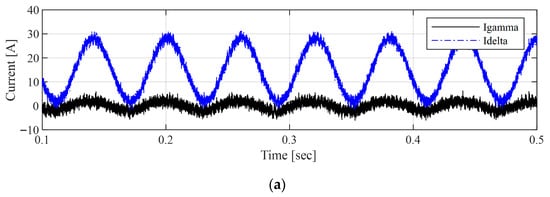

Figure 4 presents the results with and without applying the wavelet filter using the selected mother wavelet db1 for denoising the least-order observer input variables and .

Figure 4.

Comparison of input current signals (a) with wavelet filtering and (b) without wavelet filtering.

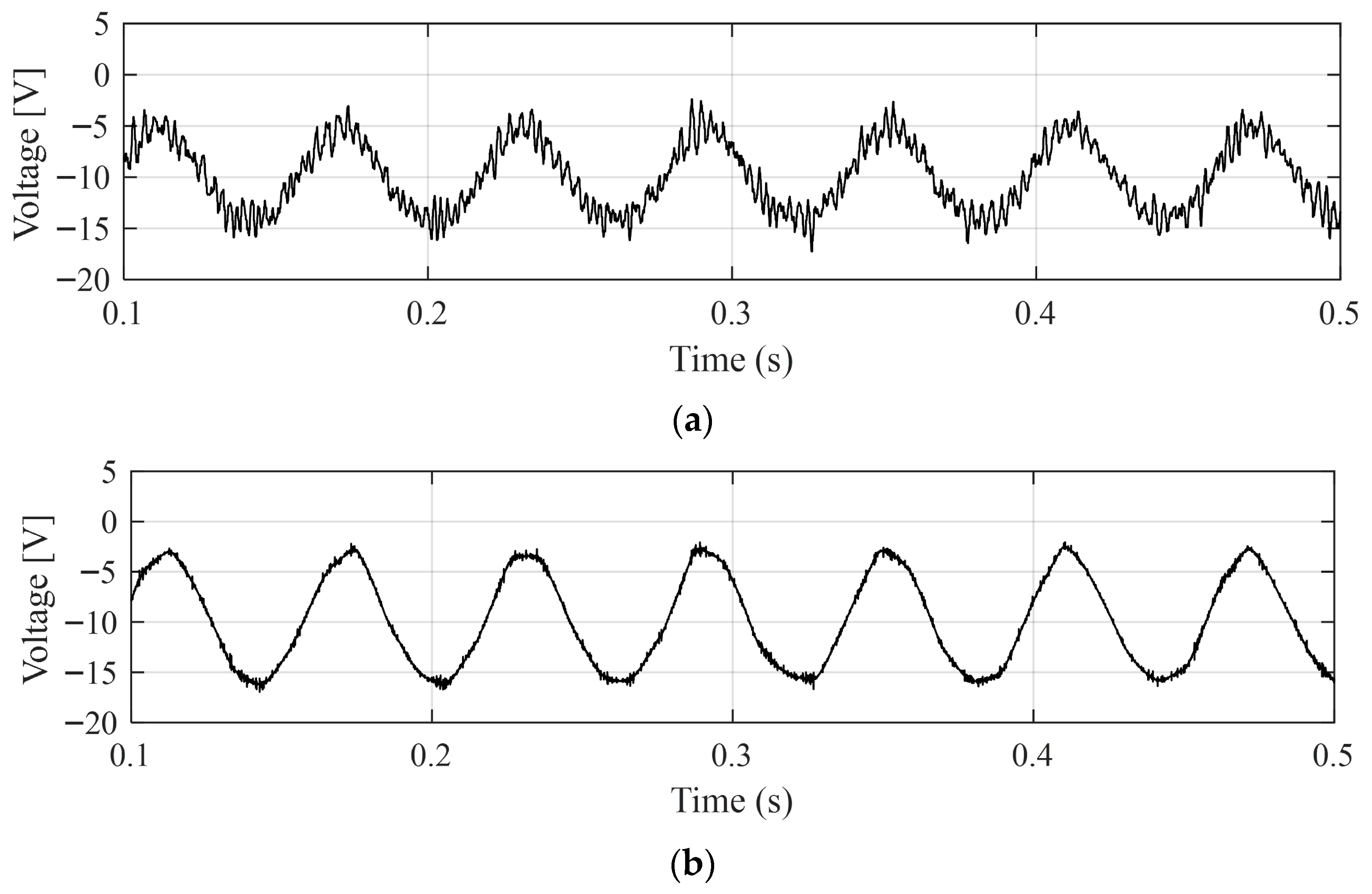

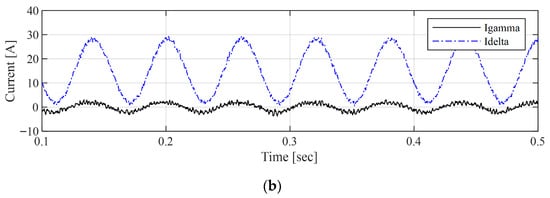

Similarly, Figure 5 presents the results with and without applying the wavelet filter using the selected mother wavelet Sym4 for denoising another input variable, .

Figure 5.

Comparison of voltage signal (a) with wavelet filtering and (b) without wavelet filtering.

To improve the estimation accuracy of the conventional least-order observer, reliable estimates are required not only to compensate for distortions in the input signals but also for the time delay in the output signals. Therefore, to address the time-delay issue in the output signals, simulations and experiments were carried out based on the proposed methodology presented in Section 3.

First, , in (28) and (29) were divided into multiple segments, and candidate values of the time delay were obtained by varying the delay in each segment and identifying the point at which the coherence reached its maximum. In addition, within the time domain, the transition region of the slope, where the correlation coefficient between the two signals was maximized in each segment, was identified and corrected, thereby enabling accurate estimation of the time delay even under non-stationary signals.

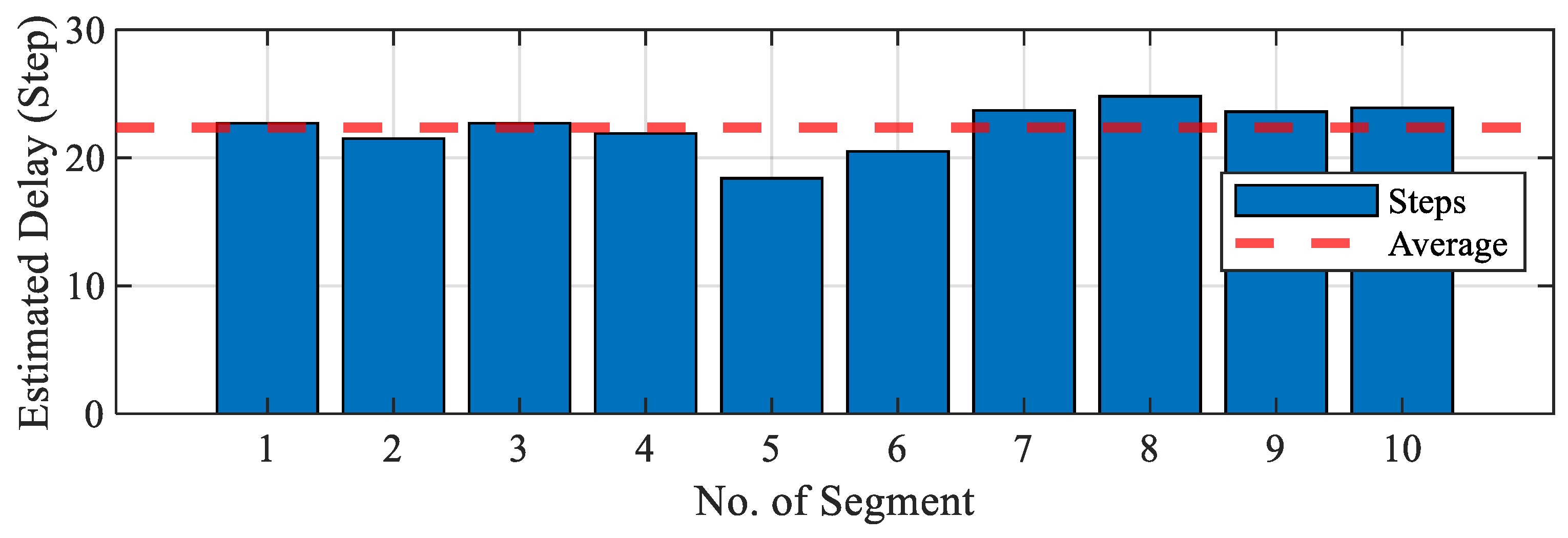

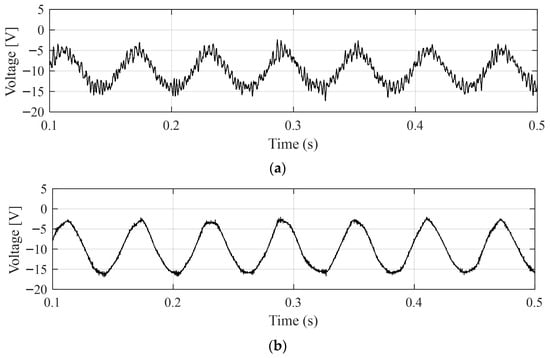

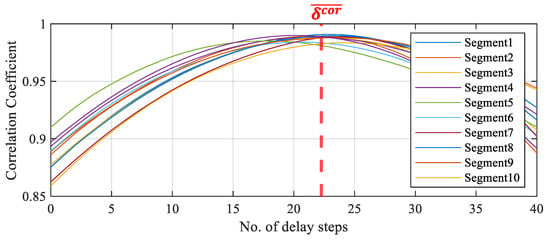

Figure 6 presents the coherence comparison results across segments for compensating the output signal time delay in the least-order observer model. The number of segments in (30) was set to 10, and by varying the size of the time step for time-delay compensation, the step size at which the maximum coherence occurred in each segment was identified as a candidate time-delay step. Among these, the segments corresponding to the minimum and maximum delay steps were excluded, and the remaining eight segment delay steps were selected as the final candidate step .

Figure 6.

Comparison of estimated time-delay steps obtained from segment-based coherence analysis.

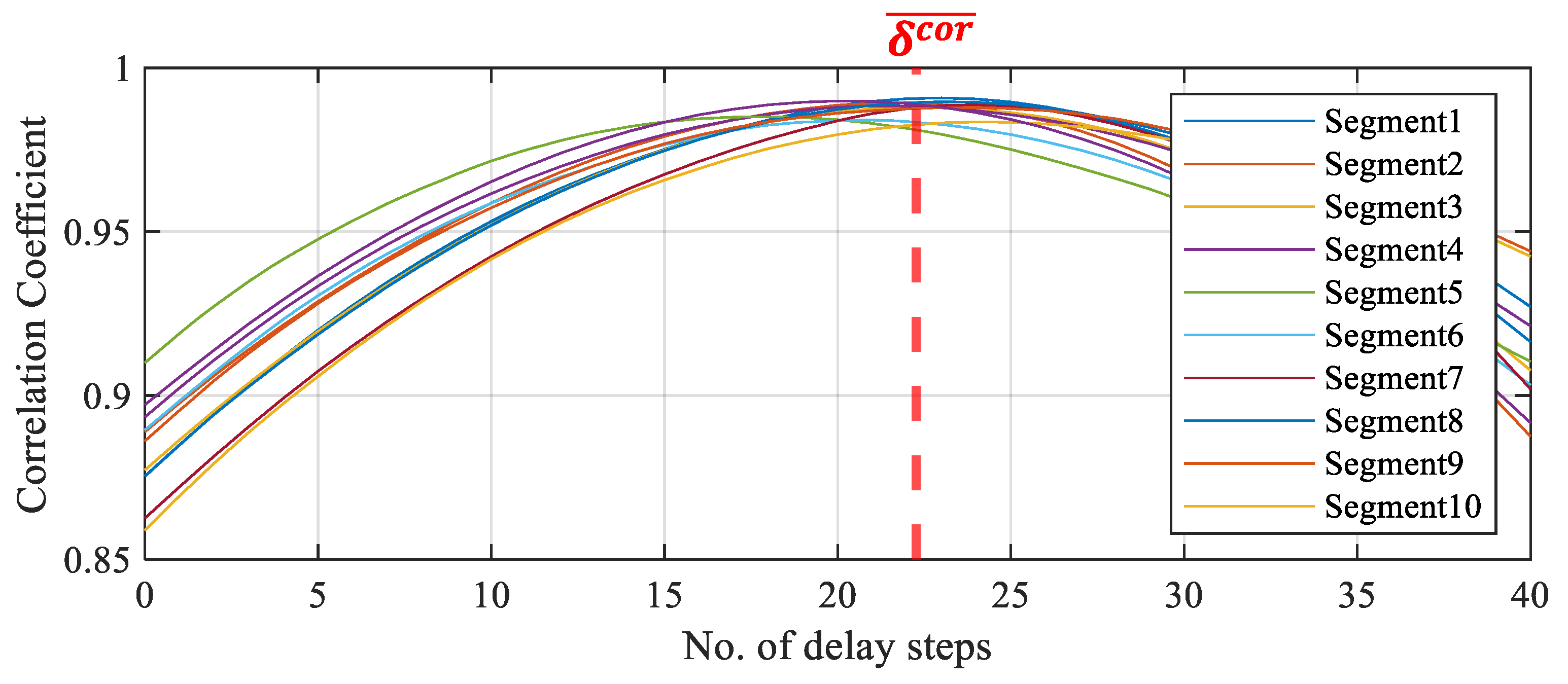

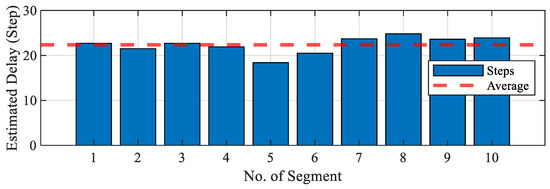

Figure 7 presents the segment-based comparison results for selecting the step that shows the highest linearity and correlation in the time domain, which cannot be fully captured by coherence analysis. By considering the first derivative of the correlation coefficient, the inflection point where the average slope of the curve was minimized was identified, thereby enabling the determination of the exact time at which the time delay was minimized in the time domain. Finally, based on the average of the results from the ten segments, the reference step was determined to be 22.3.

Figure 7.

Inflection-point analysis of correlation coefficients across segments.

Finally, among the candidate steps obtained from the coherence-based analysis, the value closest to the average correlation-based step was selected and determined as the final estimated delay step . Accordingly, the final output delay time was obtained using (38), and the estimated time delay of the signals was compensated by applying (39) and (40).

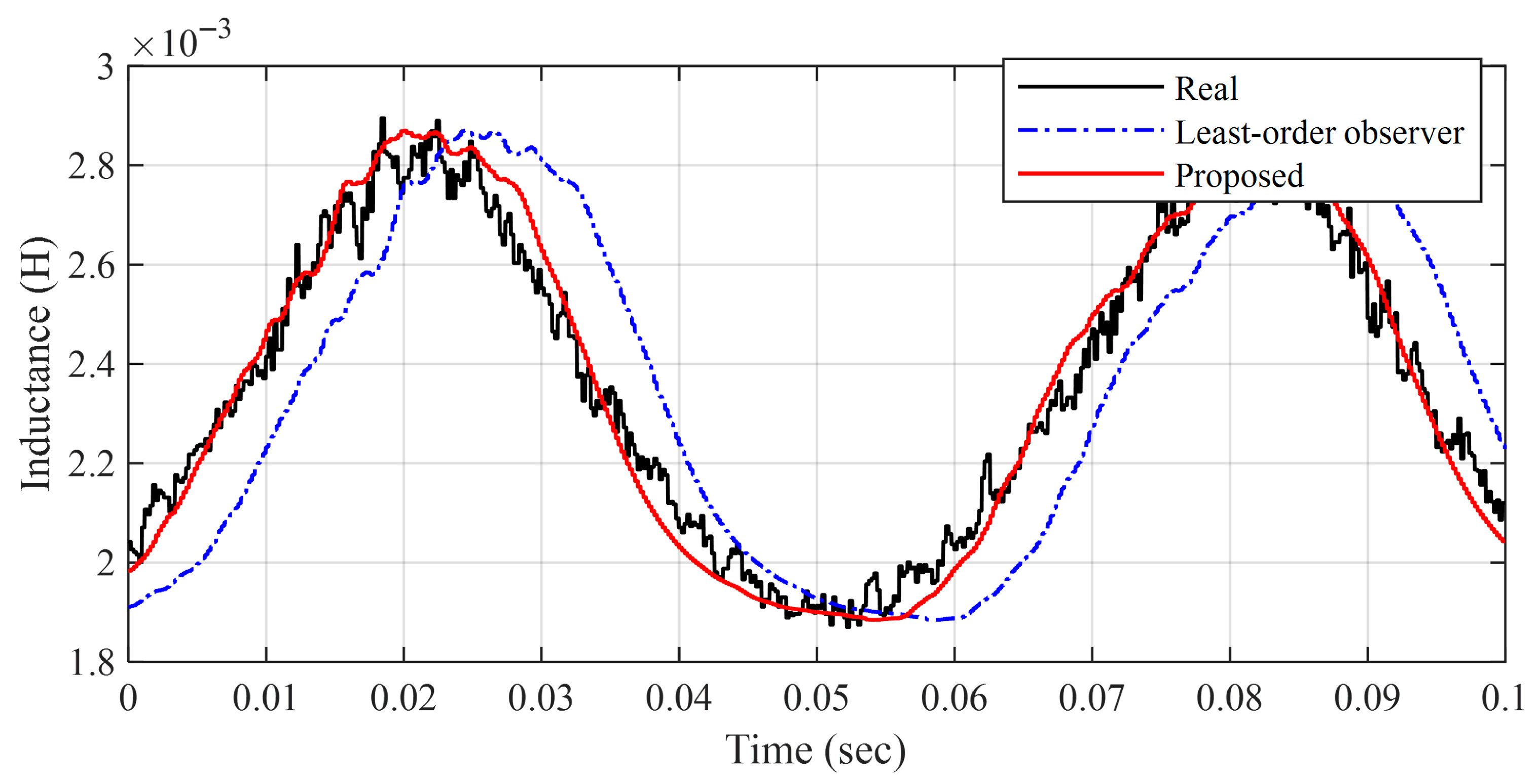

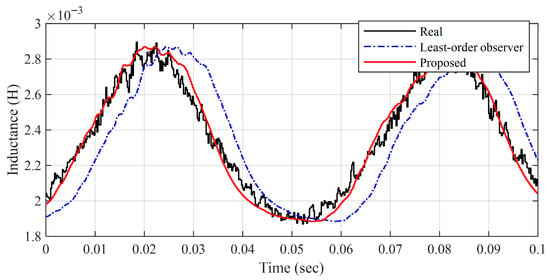

Figure 8 presents the comparison results of the real and estimated inductance. Compared to the uncompensated case, the compensated inductance estimate closely follows the real signal without delay, and the estimation error caused by the observer output delay is significantly reduced.

Figure 8.

Comparison of real and estimated inductances.

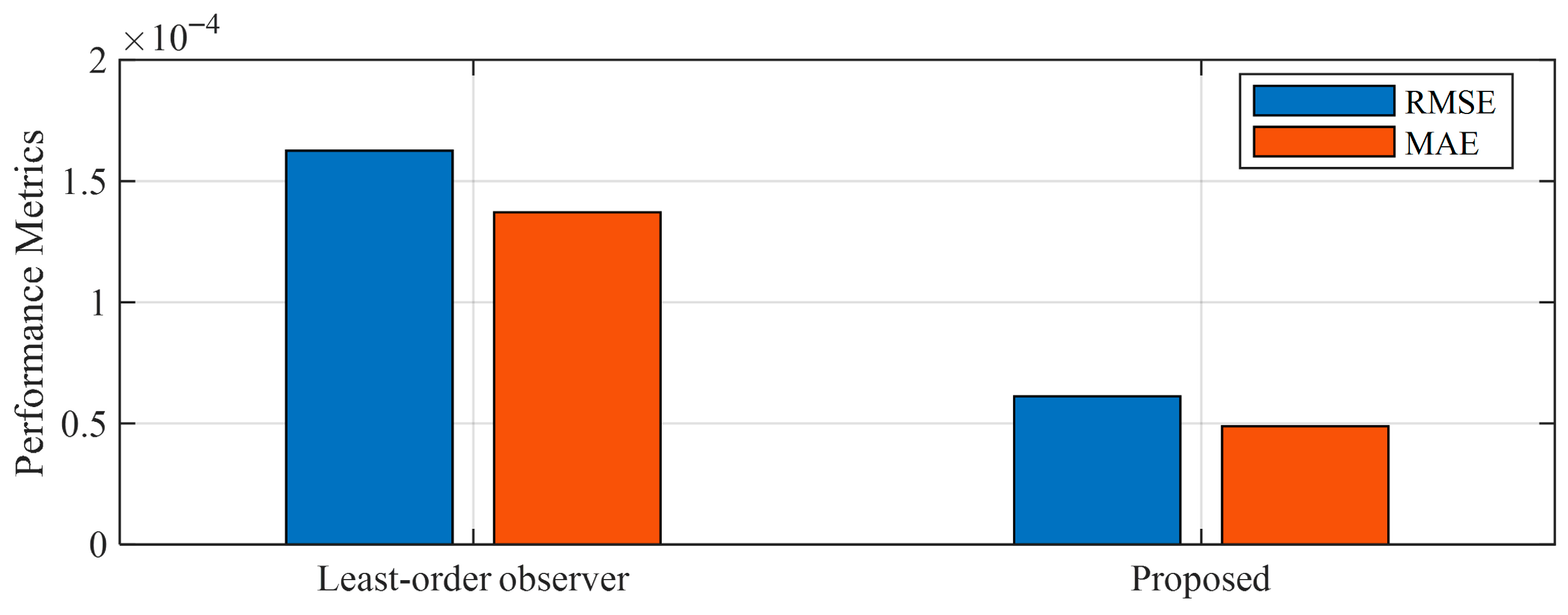

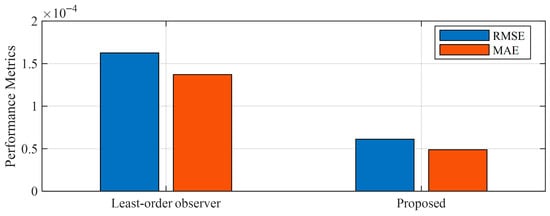

Figure 9 and Table 3 present a comparison of the mean error (MSE) and root mean square error (RMSE) of the time-delay estimates obtained by applying the proposed coherence- and correlation-based approach and the conventional least-order observer. The experimental results show that the proposed coherence- and correlation-based time-delay estimation method significantly improves accuracy by simultaneously considering both frequency- and time-domain signal characteristics.

Figure 9.

Comparison of time-delay compensation results.

Table 3.

Numerical results of time-delay compensation.

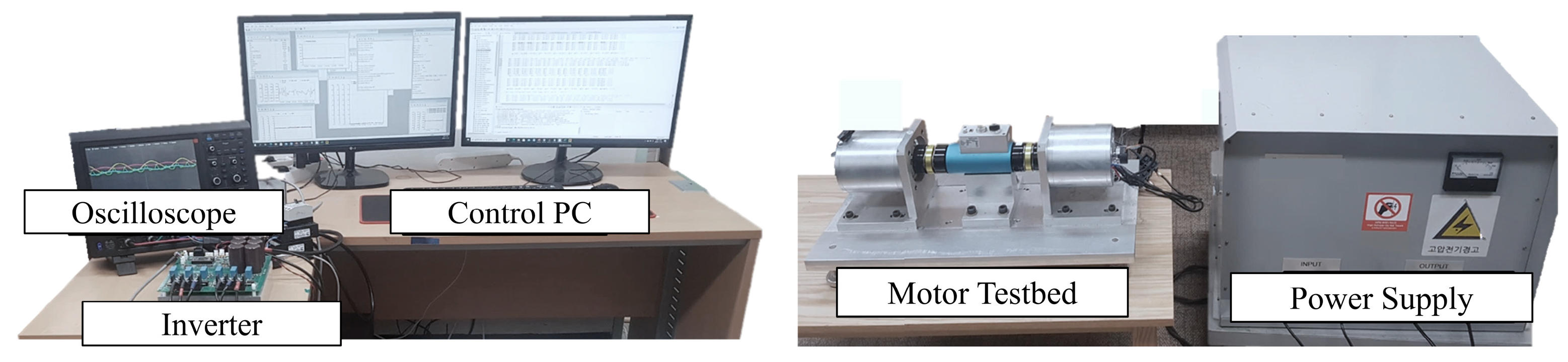

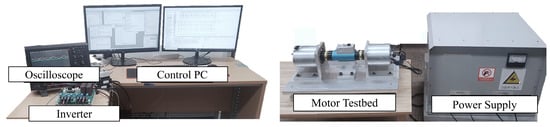

Figure 10 illustrates the experimental setup based on a motor testbed. For the experiment, the compressor of a Sonata hybrid vehicle was disassembled, and two motors were fabricated and utilized. A dual inverter was also developed to independently control each motor. In addition, since the load was represented through torque control, a periodic load torque current was generated by supplying q-axis current to the load motor, thereby emulating a varying load-torque environment. The inverter system for driving the motor was implemented using a TI TMS320F28335 MCU. The IRFP4868PbF was employed as the power MOSFET for the three-phase inverter, while ACS758KCB-150B sensors were used for three-phase current measurement, providing sufficient margin to withstand potential spike components during inverter switching. In addition, auxiliary circuits, including noise-reduction filters and communication interfaces for motor drive control, were incorporated into the experimental setup. Real-time data communication and monitoring between the MCU and the PC were established via a serial communication interface. The output signals of key variables, such as the estimated inductance and speed, were continuously monitored using a four-channel digital-to-analog converter (DAC) and observed on an oscilloscope to verify system performance.

Figure 10.

Experimental testbed for real-time inductance estimation.

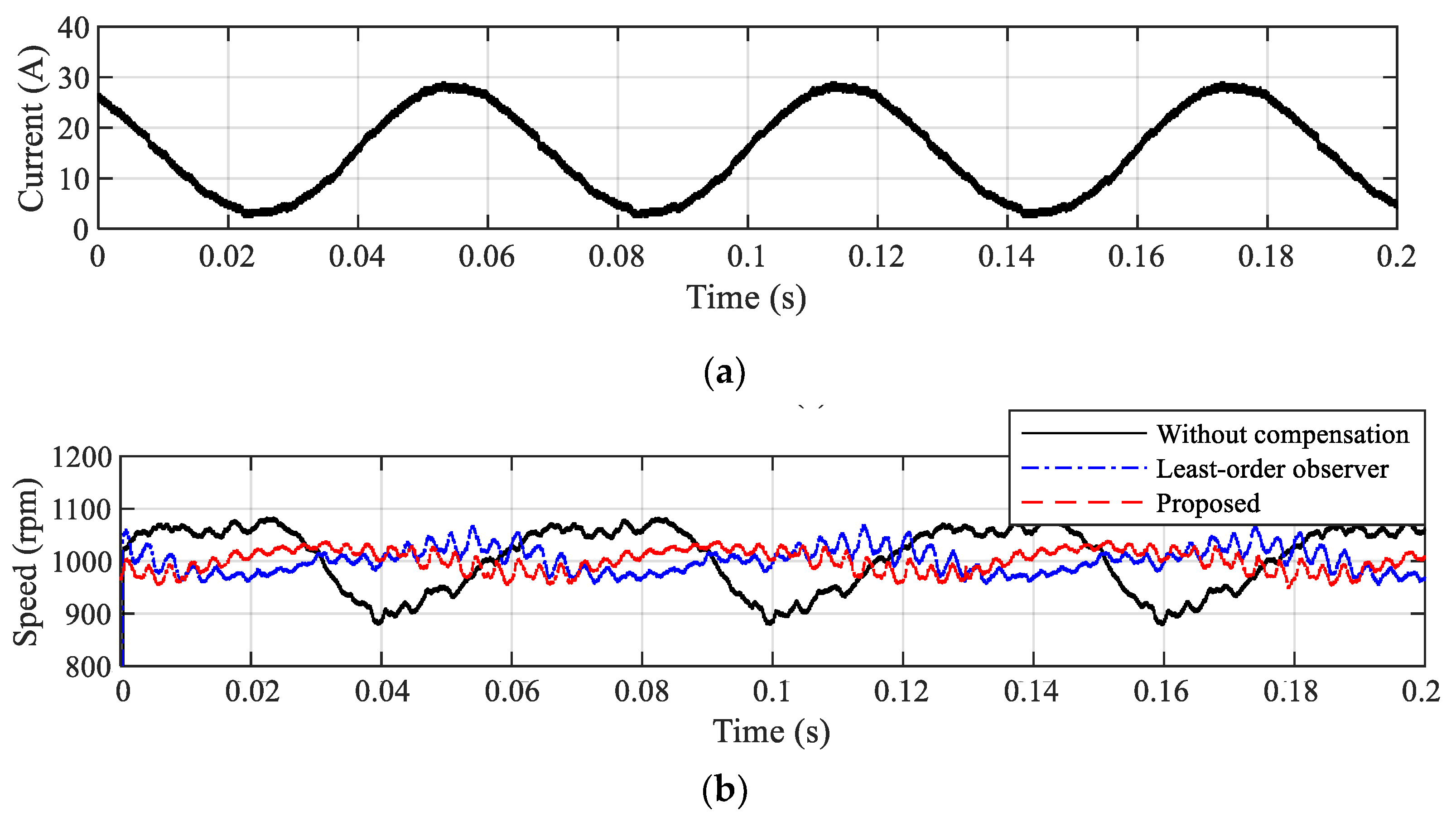

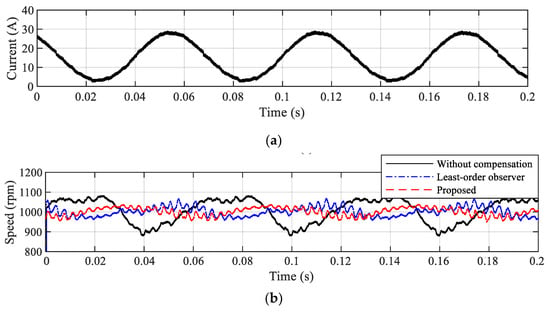

Figure 11 shows the experimental rotor speed results of the sensorless PMSM drive under magnetic saturation induced by an external load. The motor was operated at a constant speed of 1000 rpm, and without inductance estimation compensation, a ripple of approximately ±100 rpm was observed in the estimated speed. In the case of sensorless control using the conventional least-order observer scheme based on the least-order observer, the speed ripple was reduced to less than half compared with the uncompensated case; however, its magnitude still exceeded ±50 rpm. In contrast, when the proposed compensation control was applied, the ripple amplitude was significantly reduced to within ±40 rpm. These results demonstrate that the proposed control strategy effectively suppresses speed fluctuations by approximately 20%, owing to its accurate estimation and compensation of magnetic saturation.

Figure 11.

Experimental results under magnetic saturation for (a) q-axis current and (b) speed comparison with and without compensation.

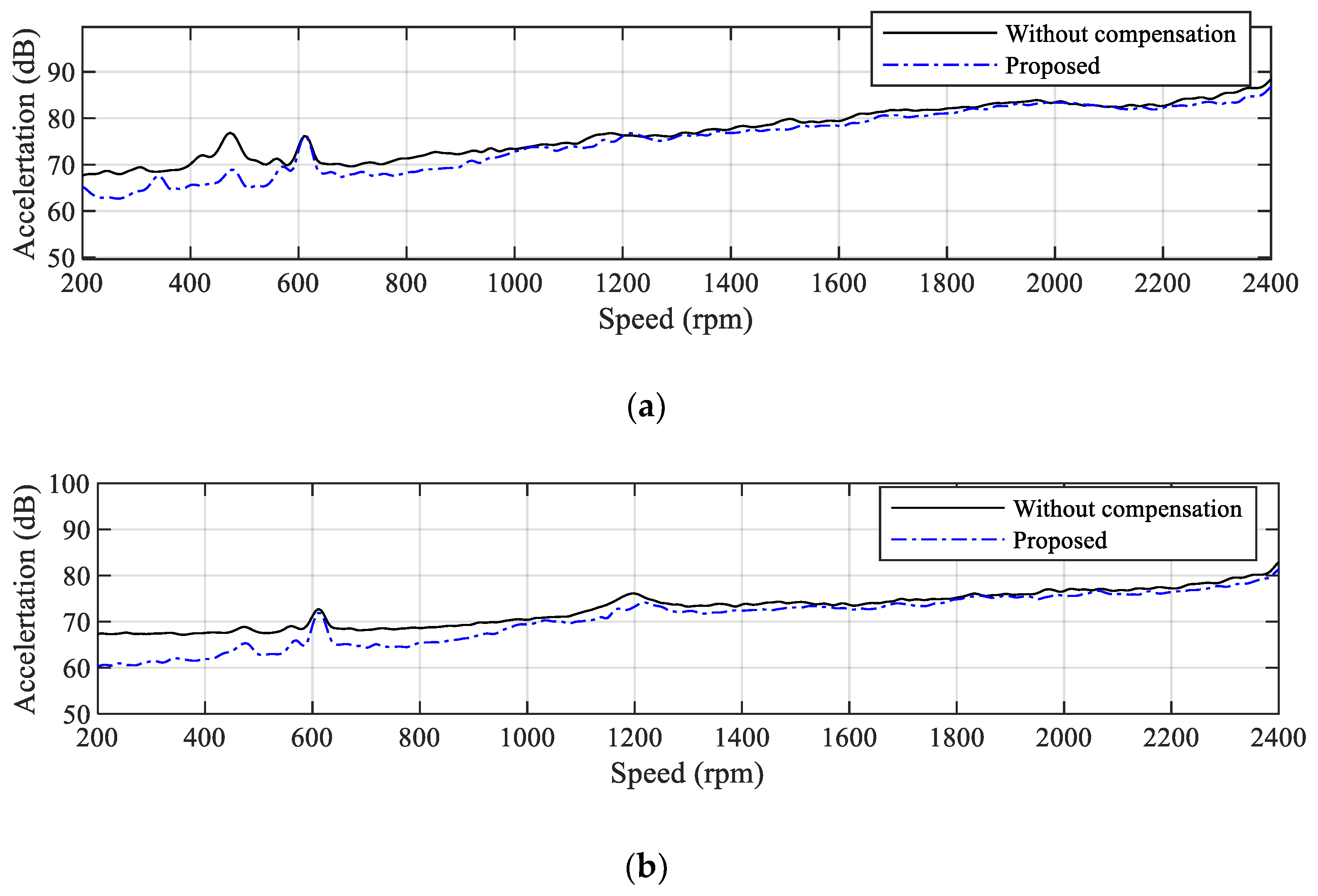

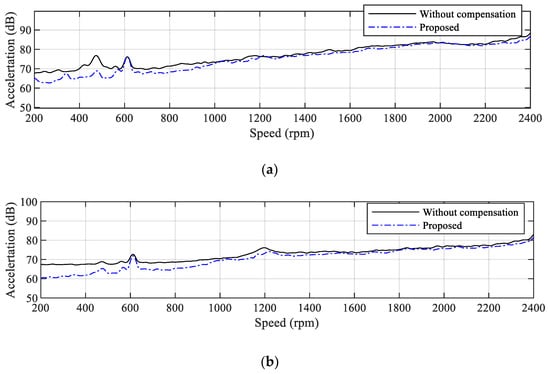

Figure 12 presents the experimental results comparing the vibration magnitude with and without the proposed real-time magnetic saturation compensation. The motor speed was increased from a low speed of 200 rpm up to 2400 rpm, and the tests were conducted in both the horizontal and vertical directions. The experimental results show that when the real-time inductance estimation-based flux-saturation compensation was applied, the vibration magnitude was reduced by an average of 2–3 dB compared with the baseline, which corresponds to the ‘Without compensation’ case. In particular, a reduction exceeding 5 dB relative to the baseline was observed in the low-speed region below 500 rpm. Since the fluctuating load currents are applied under the same conditions regardless of speed, the influence of inductance variation caused by flux saturation becomes more pronounced at low speeds. Consequently, flux-saturation compensation is particularly effective in reducing vibration in the low-speed region.

Figure 12.

Vibration characteristics of sensorless PMSM drives with and without magnetic saturation compensation in (a) horizontal and (b) vertical directions (dB reference: (g)).

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a coherence- and correlation-based time delay compensation method is proposed following wavelet denoising preprocessing to achieve accurate real-time inductance estimation in a sensorless PMSM drive system. First, we employed a systematic approach to select the optimal mother wavelet using the maximum energy-to-Shannon entropy criterion in order to reduce noise in the PMSM drive system signals. Then, the time delay in the output of the least-order observer is compensated using a coherence- and correlation-based time delay estimation method. By applying the proposed technique, we could achieve a relatively simple yet accurate real-time estimation performance for the inductance parameters and experimentally verified that the sensorless control performance was efficiently enhanced compared to the conventional method. The proposed technique is expected to be utilized for parameter estimation and compensation control in various types of motor control systems in the future, as it is suitable for real-time embedded control system implementation due to its ability to adapt to diverse operating conditions, relatively fast computation speed, and high accuracy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and J.B.; methodology, G.P. and J.B.; software, G.P.; validation, G.P. and J.B.; formal analysis, G.P. and J.B.; investigation, G.P. and J.B.; resources, G.P.; data curation, G.P.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, J.B.; visualization, G.P.; supervision, J.B.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, G.P. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning of Korea (25-IT-01) and research grants from Daegu Catholic University in 2025 (No. 20251084).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Morimoto, S.; Kawamoto, K.; Sanada, M.; Takeda, Y. Sensorless control strategy for salient-pole PMSM based on extended EMF in rotating reference frame. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2002, 38, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Bae, J. Inductance Estimation Based on Wavelet-GMDH for Sensorless Control of PMSM. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tao, B.; Xiao, M.; Yang, G.; Zhang, X.; Lu, K. Luenberger position observer based on deadbeat-current predictive control for sensorless PMSM. Electronics 2020, 9, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoia, H.K.; Chen, S.C.; Chang, C.F. Realization of the Neural Fuzzy Controller for the Sensorless PMSM Drive Control System. Electronics 2020, 9, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, S.; Sanada, M.; Takeda, Y. Effects and Compensation of Magnetic Saturation in Flux-Weakening Controlled Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1994, 30, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, C.; Bisceglie, G.; Torreggiani, A.; Davoli, M.; Macrelli, E.; Bellini, A.; Frigieri, M. Effects of the Magnetic Model of Interior Permanent Magnet Machine on MTPA, Flux Weakening and MTPV Evaluation. Machines 2023, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Park, H.; Kim, C.; Lee, H. A Review of State-of-the-art Techniques for PMSM Parameter Identification. J. Electr. Eng. Tech. 2020, 15, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.J.; Gu, B.G.; Kim, J.; Nam, K.; Kim, Y. Inductance Estimation of Electrically Excited Synchronous Motor via Polynomial Approximations by Least Square Method. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 1526–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Yao, X. A Modified Flux Sliding-Mode Observer for the Sensorless Control of PMSMs with Online Stator Resistance and Inductance Estimation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 8652–8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplais, F.; Tsiotras, P.; Jung, D. On-line wavelet denoising with application to the control of a reaction wheel system. In Proceedings of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Providence, RI, USA, 16–19 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Khorbotly, S.; Khalil, A.; Carletta, J.; Husain, I. A wavelet based denoising approach for real-time signal processing in switched reluctance motor drives. In Proceedings of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society Annual Conference (IECON), Raleigh, NC, USA, 6–10 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Ponci, F.; Monti, A.; Gao, L.; Dougal, R.A. A novel brushless DC motor speed estimator based on space frequency localized wavelet neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Austin, TX, USA, 6–10 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Radwan, T.S.; Rahman, M.A. Wavelet Packet Transform Based Protection of Three-Phase IPM Motor. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, Montreal, QC, Canada, 9–13 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Rahman, M.A. Implementation of a new wavelet controller for interior permanent magnet motor drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2008, 44, 1957–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, N. Simultaneous noise suppression and signal compression using a library of orthonormal bases and the minimum description length criterion. Wavelet Anal. Its Appl. 1994, 4, 299–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, E.Y.; Mardiana, R.; Kawasaki, Z.I. Wavelet-based compression of power disturbances using the minimum description length criterion. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power Engineering Society Summer Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 15–19 July 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.N.; Tiwari, A.K. Optimal selection of wavelet basis function applied to ECG signal denoising. Digit. Signal Process. 2006, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Gao, R.X. Base Wavelet Selection for Bearing Vibration Signal Analysis. Int. J. Wavelets Multiresolut. Inf. Process. 2009, 7, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankar, P.K.; Sharma, S.C.; Harsha, S.P. Fault diagnosis of ball bearings using continuous wavelet transform. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 2300–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L. De-noising by soft-thresholding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1995, 41, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L.; Johnstone, I.M. Ideal spatial adaptation by wavelet shrinkage. Biometrika 1994, 81, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonhstone, I.M.; Silverman, B.W. Wavelet threshold estimators for data with correlated noise. J. R. Statis. Soc. Ser. B 1997, 59, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.C. Coherence and time delay estimation. Proc. IEEE 1987, 75, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B.; Kertész, J. Accurate estimator of correlations between asynchronous signals. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2009, 389, 5138–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).