Abstract

The use of innovative technology in the field of Speech and Language Therapy (SLT) has gained significant attention nowadays. Despite being a promising research area, Socially Assistive Robots (SARs) have not been thoroughly studied and used in SLT. This paper makes two main contributions: firstly, providing a comprehensive review of existing research on the use of SARs to enhance communication skills in children and adolescents. Secondly, organizing the information into tables that categorize the interactive play scenarios described in the surveyed papers. The inclusion criteria for play scenarios in the tables are based only on their effectiveness for SLT proven by experimental findings. The data, systematically presented in a table format, allow readers to easily find relevant information based on various factors, such as disorder type, age, treatment technique, robot type, etc. The study concludes that the despite limited research on the use of social robots for children and adolescents with communication disorders (CD), promising outcomes have been reported. The authors discuss the methodological, technical, and ethical limitations related to the use of SARs for SLT in clinical or home environments, as well as the huge potential of conversational Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a secondary assistive technology to facilitate speech and language interventions.

1. Introduction

There has been a growing interest in the use of innovative technology in Speech and Language Therapy in the recent years. SARs have drawn significant attention in the field of speech and language therapy in the last decade. While initial results have been promising, further exploration is needed to fully understand the potential and usefulness of SARs in the SLT. It has been observed that the robots provide effective and engaging therapy experiences for children and adolescents with different communication disorders. The objectives of this paper are to examine the use of SARs in the treatment of such disorders among juveniles and to explore the benefits and limitations of existing research in this area.

Challenges, which are commonly associated with the use of SLT in a virtual environment and with social robots, are related to technical issues such as software compatibility, hardware failures, internet connectivity, methodological issues and lack of customization, limited personal social interaction, constraints in social cues, lack of ethical guidelines, training for therapists, integration with traditional therapy methods, integration of technology, and collaboration between therapists and technology (guidance and feedback during therapy sessions), as well as high cost. Ongoing research and evaluation of therapy based on social robots can provide evidence-based insights regarding their efficacy, and facilitate the identification of areas that could be improved.

A communication disorder refers to a condition in which an individual has difficulty to send, receive, process, and comprehend information that is represented in verbal, nonverbal, or graphical modes [1]. This can include difficulties with speech, language, and/or hearing. An impairment of articulation of speech sounds, voice, and/or fluency is defined as a speech disorder. According to DSM-V, a language disorder is due to persistent difficulties in the production and/or comprehension of any language forms—spoken, written, sign language, etc. [2]. A congenital or acquired-in-early-childhood hearing disorder can cause limitations in speech and language development. A communication disorder has an impact on interpersonal, educational, and social functioning and it can affect a person’s and their family’s quality of life [1,2].

Play is widely recognized as a fundamental activity for the overall development of every child [3] and it is essential for health and growth [4,5]. Play is an important part of speech and language therapy. Today, a range of play-based interventions have been developed to foster these skills in autistic children [6]. The child needs a combination of skills-based therapeutic work and play-based learning. Assistive technology allows for comfort and can broaden the scope for the child to play [7]. The majority of interventions have focused on children’s social, communication, and language skills [8].

The current survey was performed via exploring the following scientific databases: Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Google Scholar, MDPI, and IEEE.

This review investigates the potential of social robots for speech and language therapy. The authors focused on the following research questions:

Are SARs used in speech and language therapy and how common are they?

What type of scenarios with social robots have been developed for therapies of children/adolescents with communication disorders?

What are the technical, methodological, and ethical limitations and challenges of using social robots in speech and language therapy?

The objectives of the current paper are: (1) to present a literature review of the research in the implications of social robots in logopedic therapy and rehabilitation for children and adolescents with communication disorders, and (2) to design tables that systematically display the interactive play scenarios between humans and robots, as described in the papers reviewed. The inclusion criteria for the play scenarios in the tables are solely based on their effectiveness for SLT, supported by experimental findings, and involve the use of socially assistive robots. This table presentation enables readers to quickly locate relevant information based on factors such as the type of disorder, age, treatment technique, type of robot, and others.

2. Methodology

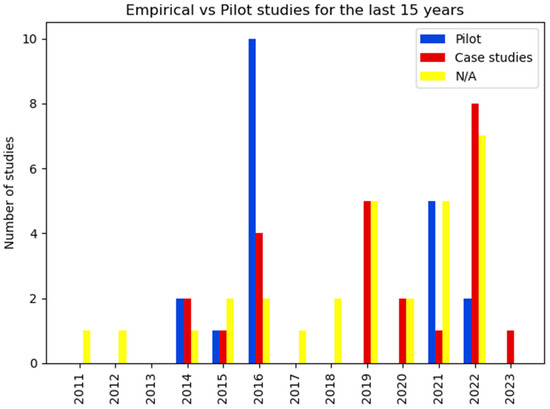

Six electronic databases were used: Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Google Scholar, MDPI, and IEEE for the period of fifteen years (January 2008–April 2023).

Eligibility criteria:

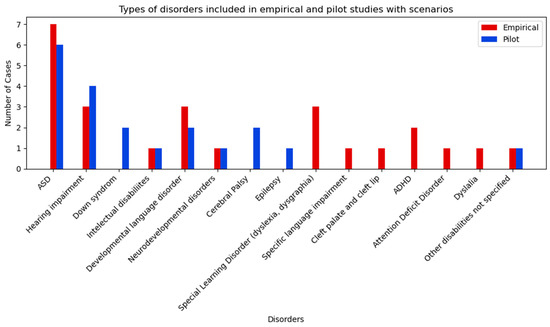

- Sample—Children and adolescents with Disabilities, Neurodevelopmental disorders, Language Disorders, Hearing impairments, Cerebral Palsy, Learning Disabilities, Fluency disorder, Stuttering, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Intellectual disability.

- Intervention—Study reports speech and language therapy, rehabilitation for social skills, language and communication disorders.

Search strategy

Keywords and phrases: Communication disorders, Children with disabilities, Neurodevelopmental disorders, Language Disorders, Hearing impairments, Cerebral Palsy, Learning Disabilities, Fluency disorder, Stuttering, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Intellectual disability, Rehabilitation of Speech and Language Disorders, Speech-language therapy, Communication skills, Turn-taking, Joint attention, Social interaction, Non-verbal communication; Robot-assisted therapy; Play-Based Intervention, Speech therapy, Robot-mediated intervention, Robotic assistant, Humanoid robot, Human–Robot Interaction, Social robot, Nao, Furhat Robot.

Inclusion criteria: The searched keywords must be present in the title, abstract, and full text of the articles. Articles must include a minimum of two of the keywords: robot + at least one Communication disorder, and SAR was used as an assistant in SLT.

In total, 100 articles were reviewed, but only 30 of them met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed.

The references in Section 5 are related to future directions on how to optimize the role and importance of social robots in speech and language therapy.

The main criteria for the selection of articles in the review was existence of scenarios of interventions between child and robot.

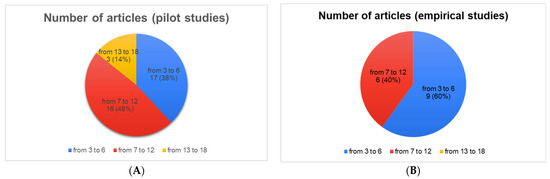

The human–robot interactive scenarios are presented in two tables. Table 1 includes description of scenarios from pilot studies, and Table 2—from empirical ones.

The structure of the presented scenarios includes: reference number, objectives, treatment domain, type of CD, treatment technique, play type (social, cognitive), interaction technique, age, activity description, robot configuration and mode of operation, used software, setting and time, variation.

3. Related Works on Social Robots for the Therapy of Communication Disorders

This section reviews the existing research on the use of SARs to enhance communication skills in children and adolescents in the last 15 years. Then, the authors discuss the methodological, technical, and ethical limitations related to the use of SARs for SLT in clinical or home environments.

The specific focus of our research questions is narrowed to the use of SARs in speech and language therapy and the interactive scenarios developed for therapies of children/adolescents with communication disorders. Therefore, more general research questions concerning the degree of integration of social robots in special education, the impairments that social robots have been used for, and the challenges in integrating social robots in special education are not directly addressed; however, these can be seen in [9] and [10]. The study in [9] analyzed the interaction of social robots with children in special education, including quantitative information on studies with multiple impairments that aim to improve social, cognitive, and communication skills. Table 2 in [9] presents quantitative information on the examined studies. In the study [10], 344 social robots were examined with their applications in various domains including service, healthcare, entertainment, education, research, and telepresence.

The outcome of our research on the systematic review of the use of SARs in speech and language therapy for children and adolescents produced table format scenarios presented in Section 3. Twenty-three articles have been analyzed in a tabular format and can be searched using keywords such as treatment domain, type of communication disorder, treatment technique, play type, interaction technique, participants’ role and behavior, age, activity description, robot configuration and mode of operation, used software, setting and time, and variation.

3.1. Social Robots as ATs in the Rehabilitation of Communication Disorders

In the 2022 UNICEF report [11] on assistive technologies for children with neurodevelopmental disorders, socially assistive robots and virtual reality are identified as high-tech assistive technologies with the most promising results in promoting social interaction and communication. SARs have the greatest potential: robots can play the role of a friend in a game or a mediator in the interaction with other children or adults, promote social interaction, and change the role of the child from a spectator to an active participant. Research shows that Assistive Technologies (AT) improve the skills of children with CD [12,13]; however, their use is still limited, possibly due to a lack of methodological and ethical guidelines and instructions for their use. SARs must be “empathetic”, “digitally intelligent”, stable, and reliable so that they can be assistants in speech and language therapy work. Therefore, they need assistive technologies such as mobile platforms for telepresence, virtual reality, interfaces for tracking body behavior, user interfaces for interaction through gestures or emotions, natural language interfaces, etc.

There are very few scientific studies on the use of SAR in speech and language therapy practice [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The most frequently used robot is of the NAO type, which participates with children with CD in individual sessions. Reported results show that it increases motivation and enhances children’s attention [12,13,14,15,16,17]. In addition to making the intervention more engaging, the robot supports therapists and the child’s family. For example, NAO does not have a human mouth and does not allow lip reading, and this makes children use their hearing to hear what the robot says when it speaks [15]. As a result of experiments [17] on the use of NAO in speech therapy conducted by members of the project team, it was concluded that there was a need to expand the environment in which children and robots communicate by applying more innovative image recognition and improving verbal interactivity with the robots. For example, one of the favorite games of children is shopping and telling a story via a series of pictures, but actions based on pictures are difficult to be animated by NAO, while a 3D project offering shopping in a virtual grocery store would be more realistic and attractive. In addition,, NAO is not so engaging for children with CD in middle schools, so there is a need for different 3D applications as well as a more innovative SAR to be developed and used. Other robots used to improve the social and communication skills of children with CD are robots which change their emotional facial expression or have cloud-based chat services, such as iRobiQ [16] and QTrobot [18]. Unfortunately, their price is not affordable for home use.

Robot assistants using other innovative assistive technologies in speech therapy intervention and inclusive education are presented in [26,27]. They integrate intelligent ICT components and tools, robotic systems such as cloud services [27], expert systems with speech therapy purposes, and a database of knowledge, ontologies, and concepts from the language–speech field [26]. Assistive technologies such as virtual reality are used more among children with autism spectrum disorders [28,29,30,31,32]. The STAR [29] platform is oriented to speech and language therapy and integrates augmented reality for practicing communication skills and strategies for analyzing alternative communication and applied behavior analysis (ABA). Another platform suitable for speech therapy is the VRESS [31] platform for developing customized scenarios for virtual reality to support children who practice and develop their social skills by participating in selected social stories. The platform is integrated with sensors for heart rate detection and eye tracking, which provides important feedback for further customization of scenarios as well as their evaluation. In general, eye tracking technology has recently been widely used to assess engagement in intervention tasks. With the help of the new-generation Tobii eye-and head-tracking devices, not only the attention but also the emotions of the child can be assessed.

Although research on the use of social robots in communication disorders is limited, some studies have reported promising results. For example, in [33], children with special needs who interacted with social robots Nao and CommU showed increased verbal production and engagement in therapy sessions. Another study [34] found that the presence of two social robots in a disability unit for adolescents with special needs led to improvements in articulation, verbal participation, and spontaneous conversations over a two-year period. The robot Kaspar has also been used in a long-term study by caregivers in a nursery school for children with ASD and has shown beneficial outcomes for the participants [35], in some special moments children use phrases and show interactive behaviour that are learned during the interactions with Kaspar and apply them to situations outside of their play with the robot.. Additionally, the humanoid robot iRobi positively impacted communication skills in children with pervasive developmental disorders using augmentative and alternative communication strategies. A low-cost robot named SPELTRA was also used to support therapy sessions for children with neurodevelopmental disorders [36], resulting in improvements in phonological, morphosyntactical, and semantic communication measures. The work [37] designed a program for improving articulation in children with cleft lip and palate using a social robot named Buddy. Similarly, Castillo et al. [38] created an application utilizing a desktop social robot called Mini to support rehabilitation exercises for adults with apraxia. In addressing stuttering, Kwaśniewicz et al. [39] employed the social robot Nao to provide “echo” by combining delayed auditory feedback and choral speech while clients worked on improving their fluency.

The reviewed paper [6] provides a comprehensive map of the research on play-based interventions targeting social and communication outcomes for autistic children and the development of a conceptual framework for the appraisal of play-based interventions to inform clinical decision-making/practitioners and families. The study reported positive outcomes in terms of social and communication skills, including related skills in social cognition, following play interventions in autistic children aged 2–8 years. This paper provides a summary of the disparate literature on the role of play in social and communication interventions in a manner that is relevant to stakeholders. In terms of clinical implications, the conceptual framework proposed in this review can help practitioners evaluate the literature and aid families in making joint decisions about an intervention (p. 21).

3.2. Technical, Methodological, and Ethical Limitations and Challenges of Using SARs in Speech and Language Therapy

Technical limitations include the high cost of purchasing and maintaining SARs, potential technical malfunctions and limitations in their ability for speech recognition and natural language processing capabilities, and emotional and social intelligence. Methodological limitations include the lack of standardization in the use of SARs in speech and language therapy. Ethical concerns include issues related to privacy and data protection, as well as potential negative effects on the therapeutic relationship between the therapist and the patient. In addition, there is a risk that children may become overly dependent on SARs for communication, rather than developing their natural communication skills.

The use of SARs in speech and language therapy can presents several technical challenges and limitations, including:

- Limited adaptability and personalization: Most SARs are pre-programmed with a fixed set of responses and behaviors, which may not be tailored to the individual needs and preferences of each patient.

- Limited physical capabilities: SARs may have limited physical capabilities, such as the ability to manipulate objects or to move around in the environment, which may limit their effectiveness in certain therapy contexts.

- Limited speech recognition and natural language processing capabilities: SARs may have difficulty accurately recognizing and understanding speech, especially in noisy environments or when dealing with non-standard dialects or accents, or in cases of speech and/or language disorders.

- Limited emotional and social intelligence: Although SARs are designed to interact with humans, they may lack the emotional and social intelligence needed to provide appropriate responses to patients who are experiencing strong emotions or who have complex social communication needs.

- Technical failures and maintenance issues: Like any technology, SARs may experience technical failures or require maintenance and updates, which can disrupt therapy sessions and create additional stress for patients and therapists.

- Cost: The cost of SAR technology and maintenance may be prohibitively high for some healthcare organizations, limiting their opportunity to provide this type of therapy to patients who could benefit from it.

The use of SARs in speech and language therapy poses several methodological challenges, including:

- Reliability and Validity: One of the main challenges is ensuring the reliability and validity of the results when using SARs in speech and language therapy. This requires careful control of the methods of study design and data collection methods to minimize sources of bias and error.

- Usability and User Acceptance: SARs must be usable and acceptable to the target population, including children with communication disorders, to be effective. This may require significant efforts to design and refine the user interface and user experience of the robot.

- Standardization: There is a lack of standardized protocols and assessment methods for using SARs in speech and language therapy, which can make it difficult to compare results across studies and determine the effectiveness of different approaches.

- Evaluation: Assessing the effectiveness of SARs in speech and language therapy often requires multiple raters to evaluate the therapy sessions. Ensuring inter-rater reliability, or consistent long-term effectiveness: Another challenge is demonstrating the long-term effectiveness of SARs in speech and language therapy. Many studies have only measured short-term outcomes, so there is a need for longer-term studies to determine the sustainability of the benefits of using SARs in therapy.

- A number of participants: Usually, the sample is small in most published research about children/adolescents with communication disorders who interact with the SARs. The study groups consist of heterogenous types of neurodevelopmental disorders and lack control groups; therefore, it is difficult to apply statistical analysis.

The use of SARs in speech and language therapy includes several ethical challenges, including:

- Privacy and Confidentiality: SARs collect and store sensitive information about the users, such as their speech and language patterns, which can raise concerns about privacy and confidentiality. This requires appropriate data protection measures, such as encryption and secure storage, to prevent unauthorized access to the data.

- Bias and Discrimination: SARs are designed and programmed by humans, which raises the possibility of unintended bias and discrimination in their behavior and interactions with users. This requires careful consideration of the design and programming of SARs to ensure that they do not perpetuate or amplify existing biases and discrimination.

- Responsibility and Liability: SARs are increasingly being used in healthcare settings, which raises questions about who is responsible and liable for any harm caused by their use. This requires clear and well-defined policies and procedures for the use of SARs in healthcare and speech and language therapy, as well as appropriate insurance coverage and risk management strategies.

- Interpersonal Relationships: SARs may have the potential to affect interpersonal relationships and human interactions, including the relationships between patients, therapists, and caregivers. This requires careful consideration of the design and use of SARs to ensure that they enhance, rather than undermine, existing relationships and interactions.

- Dependence and Over-Reliance: There is a risk that users may become overly dependent on SARs and cease to engage in important interpersonal relationships and activities, which can have negative impacts on their health and well-being. This requires careful monitoring and evaluation of the use of SARs in speech and language therapy to ensure that they are not creating negative consequences for users.

4. Related Works on Interactive Scenarios with Social Robots for the Therapy of Communication Disorders

This section presents the interactive play scenarios involving SARs for SLT derived from the surveyed papers. We analyzed some of the most useful, informative, or easily replicable scenarios in more detail. The interactive play scenarios, which have been verified by experiments, are organized and categorized in table format. Table 1 describes scenarios from pilot studies, while Table 2 presents scenarios from empirical studies.

The authors in the article [40] describe a case study with an eight-year old child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The research aims are to improve the joint attention and social skills of the student. For this purpose, one assistive technology is used—the socially assistive robot NAO. The article offers robot-assisted procedures, used in the study, to practitioners in schools. In addition, the authors claim that using robots to teach and practice social and communication skills can be interesting, motivating, and fun for students and encourage researchers to focus more on robots in their future work so that the communication skills of students with ASD can be enhanced.

In [41], a robot-assisted therapy is applied via a single assistive technology—a pet robot called CuDDler (A*STAR Singapore) to three children with ASD. The authors design a training protocol based on experimental psychology which emphasizes the cognitive mechanisms of responding to joint attention (RJA). Results indicate improvement in RJA in the post-training in comparison with the pre-training test. However, the scientists evaluate the joint attention skills soon after the last session (around 3 days later). Therefore, future work should try to investigate whether an improvement in RJA is observed in the long term. Moreover, follow-up studies should include a larger sample and test the effects of longer training. The authors also suggest that future work will have to develop methods to make robot training more engaging.

In [42], the scientists apply a music-based therapy, assisted by the social robot NAO, to four autistic children. The case study continues for three months and the results show that the students have learned to play musical notes and the scenarios positively influenced fine movements, communication abilities, and autism as a whole. The limitations in that study are related to the small number of autistic participants and the access to valid tools which can measure children’s behavior accurately. Thus, the authors propose bigger samples in future research so that statistical analysis can be applied.

The article [43] presents a case study in which children with ASD interact with the humanoid robot NAO in a football game scenario during four sessions. The qualitative and quantitative analyses show that there is improvement in communication skills, social interplay, turn taking, and eye contact. Although the article provides valuable insights into child–robot interaction, the size of the sample is small and a bigger number of individuals should be considered in future work.

The case study in [44] again presents the use of the social robot NAO as an assistant in logopedic and pedagogical therapy with children with different needs, especially ones related to speech and language. The authors propose an architecture that develops “adaptive behavior” and is applied to engineer–therapist–child interaction. Findings in the study suggest that the use of humanoid robots is promising and can improve interventions in speech-therapy centers. Regarding future work, the scientists point to the development of intelligent algorithms so that the presence of the engineer–programmer in the sessions can be eliminated.

Another study [45] reveals robot-based augmentative and alternative ways of communication for non-verbal children with communication disorders. The assistive technology used in the case study is the humanoid robot iRobi. The study evaluates changes in gestures, speech, vocalization, and verbal expression and the results show a positive influence on the communication abilities of non-verbal children. The limitations of the work concern the small number of participants and the authors recommend that robot-based AAC be modified to expand the vocabulary of the non-verbal children.

The authors in the article [46] propose a conceptual framework for designing linguistic activities for children with developmental speech and language impairments or autism. This is a pilot study that develops and assesses only a tablet experimental condition and the next empirical study is expected to be conducted regarding children’s performance in linguistic activities during interaction with robots. The results of the study are promising and in the future, scientists will explore the use of Activity Patterns for other technological solutions, such as augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and smart spaces.

The paper [47] introduces a newly developed socially assistive robot (MARIA T21) used in psychomotor therapies for children with Down syndrome and psychosocial and cognitive therapies for children with ASD. The authors describe a pilot study with serious games in four stages and highlight the children’s emotional interplay with the robot, and it is observed that the robot MARIA T21 demonstrates notable gain in the field of assistive robotics. In terms of the limitations of the study, the main difficulty was encountered during the selection of children, due to the COVID–19 pandemic which reduced the options of available clinics. Subsequently, the scientists carried out a new testing protocol with 15 children with ASD and will analyze new data for future publications.

In [48], the authors offer the use of a robotic assistant and a mobile support environment included in speech and language therapy. The approach in the pilot study is based on an integrative environment that involves mobile Information and Communications Technology (ICT) tools, an expert system, a knowledge layer, and standardized vocabularies. The experiment has been tested on 65 children suffering from different types of disabilities, and the results achieved are encouraging. It was observed that it was possible to automate several activities linked to speech language therapy. Regarding future work, the scientists propose developing an inference mechanism that can automatically select activities according to the changes in the concentration levels of each patient and design more specific activities by stimulation requirements for the skills affected in each patient.

The authors in [49] present a robotic assistant which can provide support during speech language therapy for children with communication disorders. The researchers conducted a pilot experiment in two stages—one to find out the robot’s response in controlled environments, and another to analyze the children’s responses to the robot. The variety of functionalities implemented in the robot offers speech language therapists to perform therapy sessions efficiently. In terms of future work, the scientists propose developing a mobile application for smart watches with to monitor the user response to robot-assisted therapy (pulse, vital signs, etc.); integrating the robotic assistant to multisensory stimulation rooms; developing a module based on computer vision with to incorporate face gestures recognition to support oral motor therapy; designing a voice analyzer with the objective of determining the patient’s voice quality (vocal tract configuration + laryngeal anatomy + learned component).

The research study [14] is based on a team approach: professionals in engineering/programming, qualitative analysis and education, psychology, special education, and speech therapy. For logopedic and educational treatment Aldebaran Robotics NAO named “EBA” (educational behavior aid) is used. Five Spanish-language children aged 9–12 years are included in the study, assessed by a psychologist and a speech therapist to determine the cognitive and language level of development. All children are with different diagnoses: (1) cleft palate and cleft lip, (2) specific language impairment (SLI), attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with comorbidity, dyslexia and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), (3) SLI, (4) language developmental delay and several types of dyslalia, (5) dyslexia with evolving dysgraphic and dysortographic symptoms with an ADD. The sessions with EBA are designed on the following treatment aspects: (1) for the children with dyslalia and dyslexia: Reading comprehension: short/medium- and long-term memory, literacy, storytelling, tales, vocabulary, phonological awareness, articulation and phonetical–phonological pronunciation, phonetic segmentation; (2) for the children with ADD: attention and writing; and (3) for the children with SLI: oral and written comprehension, reading and writing. The obtained results draw attention to both the positive aspects and limitations of NAO implementation in the speech therapy. The data show improvement in the child’s learning process, vocalization, construction, and structure of sentences, and an increase in the children’s confidence in themselves and motivation. An essential part of the results in an educational and therapeutic context is the non-judgmental nature of the work and well-structured language for better understanding by children. The limitations of the study are related to the small number of children included in the study, as well as the use of a single camera, which leads to the impossibility of analyzing the entire non-verbal behavior of the children. Concerning future work, the research team state that more research is needed to find out how EBA can best be implemented in speech and language therapy for more inclusive education.

The paper [50] presents the use of a robot-like assistant that provides tactile, auditory, and visual stimuli for children with speech and language disorders with the aim of motivating children to perform exercises and treatment activities and to contribute to extending the children’s attention span. For the study, a FONA robot is developed that “has 6 degrees of freedom (can move arms and walk), weights six pounds, implements a touch screen (5 inches), has three push buttons (chest) and two resistive sensors (head) that can trigger any script written in Python or C, and can play sounds through a Bluetooth speaker” (p. 588). The study included eight children, aged 4–5 years, with functional dyslalia for two months. Speech and language therapy is based on the combination of robotic assistant, a rules-based reasoning system, and the Motor Learning Theory. Data show improvement in attention span during the treatment sessions with the robot (the average child’s attention span increases by more than 17 min for a therapy session consisting of 40 min). Regarding future research work, it is necessary to develop a remote control system based on video game controls that assists children with severe motor disabilities to interact with the box and include new elements and relationships in the ontology, allowing the modeling of psychomotor abilities and concept development of children up to 7 years of age.

The paper [39] describes an application that allows the use of a humanoid robot NAO as a stutterer’s assistant and therapist based on auditory and visual feedback. For auditory feedback, the “echo” method, known also as delayed auditory feedback (DAF), is modified. For visual feedback, changes in the robot’s hand movements according to the shape of the speech signal envelope and possibility of controlling speech with a metronome effect are used. Applications for DAF are installed both on the computer and NAO, because it is important for the microphone to be close to the mouth for the feedback and for this purpose a computer/laptop’s microphones are used. It is important to note that the sound from the microphones has to be sent by the application and network to the NAO’s speakers with some delay, causing the impression of echo (data streaming). The robot moves its hands based on an auditory signal and metronome mode which allows the robot hand’s movement up and down from the lowest to the highest location. The authors state that a robot can replace the speech therapist while accompanying the patient and leading his treatment, and various types of exercises such as reading, conversing, or running a monologue can be used. Researchers suggest treatment procedures to be used for at least 20 min every day. Another advantage is that by using this type of program it will be possible for the robot to use pre-prepared questions directly, aiming to give the patient the impression of a real conversation. This will break through the social barriers associated with shyness and discomfort that result from stuttering. For future research, it is stated that the application will be tested on a group of people with speech disfluency and compared to other methods.

The study [19] investigates parental attitudes towards the robot-assisted therapy in pediatric (re)habilitation with humanoid robots. Thirty-two parents are included in the study. They had to give feedback about their children who took part in the treatment using a mobile anthropomorphic robot with cognitive skills, and to complete the Frankenstein Syndrome Questionnaire. Children had been referred to a two week-long corrective exercise training program due to poor posture.

The findings of this investigation showed that parental attitudes towards humanoid robots and robot-assisted therapy are positive, and that most of them are informed about the latest technological advances. They have neutral attitudes and positive expectations of humanoid robots and have accepted them socially. It also was found that less educated parents were more apprehensive of technology, and older parents tended to be more anxious.

In [51], the authors investigate the potential of a robotic learning assistant which could monitor the engagement of children with ASD and support them when necessary. The scientists focused on acceptable and content-specific behavior of the robot which they handled through an AI-based detection system. The results of the survey suggest that an emphasis on speech and interaction competences is needed as well as adaptability, customizability, and variability of the robot’s behavior. In addition, the robot needs to detect and react according to the current state of the children. There are a few limitations of the study. On the one hand, the sample size is relatively small and the participants were recruited through the same ASD program and interviewed via Internet-based technologies, which can impact the applicability of the findings. On the other hand, this was a qualitative study and it is not possible to determine the frequency of the identified requirements.

4.1. Components of the Play Scenarios (in Tables)

Taken from the current survey, useful interactive play scenarios that involve social robots as assistants during SLT are presented in a table format. The format of the following play scenarios is inspired by previously developed robot-assisted play scenarios, originated from [13], and broadly conforms to several current robot-assisted interventions that have been used for children, in particular for children with ASD [52,53].

4.1.1. Description of Interactive Scenarios with SARs (Pilot Studies)

A review of the scientific studies was made in which interactive scenarios with SARs are presented to support the development of children with CD. Table 1 presents interactive scenarios with SARs described in pilot studies. They are ordered chronologically, with the most recent publications appearing first.

Table 1.

Description of interactive scenarios with SARs (pilot studies).

Table 1.

Description of interactive scenarios with SARs (pilot studies).

| Reference: [17], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Farm Animals—Voices and Names |

|---|---|

| Objectives | Remote speech and language therapy; Enrich the child’s vocabulary. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Farm animals’ voices and names; children with neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of farm animal voice. Identification and pronunciation of words for farm. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Age | Four years old. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are five participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game) a social robot (instructor–Nao), a social robot EmoSan (playmate), parent (co-therapist), and a child with neurodevelopmental disorders (playmate). |

| Activity description | [17], page 123 (https://youtu.be/KpeQcIXG6cA, accessed on 16 April 2023). |

| Robot configuration and mission | A social robot NAO, a social robot EmoSan, pictures of farm animals, a tablet and a laptop, BigBlueButton platform for telepresence. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23, Python v.2.7, Node-RED v.2.1.3. |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants. |

| Reference: [17], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Storytime |

| Objectives | Follow a story and representation of a story as a sequence of scenes in time. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, children with neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Story as a sequence of scenes in time. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are four participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game), a social robot (instructor-Nao), a social robot EmoSan (playmate), and a child with neurodevelopmental disorders (playmate). |

| Age | 3–10 years old (15 children) |

| Activity description | [17], page 123 (https://youtu.be/AZhih7KlaPc, accessed on 16 April 2023) |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO, a social robot EmoSan was used with 3 pictures of story scenes and a whisk. |

| Used software | NAOqi software, v.2.8.6.23 Python 2.7, Node-RED v.2.1.3. |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Variation | - |

| Reference: [46], 2021 | Name of Scenario: Different interactive activities with a tablet; robots are expected to be used. |

| Objectives | To propose a conceptual framework for designing linguistic activities (for assessment and training), based on advances in psycholinguistics. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Speech and language impairments—developmental language disorder, autism spectrum disorder. |

| Treatment technique | Interactive therapeutic activities. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social and cognitive. |

| Interaction technique | The child performs activities on a tablet. |

| Age | 4–12 years old. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The participants in this scenario are the children (30), performing activities via a tablet. |

| Activity description | [46], page 2–6. |

| Robot configuration and mission | Socially assistive robots/tablets with different modules for training and assessing linguistic capabilities of children with structural language impairments. |

| Used software | Socially assistive robot and/or mobile device. |

| Setting and time | This scenario has been carried out in clinical settings over multiple sessions, two groups have been included—a target and a control group. |

| Variation | There are different linguistic tasks which evaluate different linguistic skills. Activities can include more than one participant. |

| Reference: [47], 2021 | Name of Scenario: Serious games conducted by a social robot via embedded mini-video projector |

| Objectives | To show the application of a robot, called MARIA T21 as a therapeutic tool. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome. |

| Treatment technique | Interactive serious games. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social and cognitive. |

| Interaction technique | Robot–child interaction. |

| Age | 4–9 years old. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The participants in this scenario are the social robot and eight children, supervised by the therapist and a group of researchers. |

| Activity description | [47], page 6–14 (see in Section 5 Methodology) |

| Robot configuration and mission | A new socially assistive robot termed MARIA T21 which uses an innovative embedded mini-video projector able to project Serious Games on the floor or tables. |

| Used software | A set of libraries-PyGame, written in Python 2.7; an open-source robot operating system. |

| Setting and time | The tests were carried out partly in a countryside region and partly in a metropolitan area, in order to expand socioeconomic diversity. |

| Variation | The games were created with all their possible events, characters, awards, and stories and have included different types of serious games. |

| Reference: [52], 2021 | Name of Scenario: Questions and Answering with NAO Robot |

| Objectives | Initiation of conversation. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to ASD. |

| Treatment technique | Asking and answering simple questions. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Age | 5–24 years old (4 children). |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are five participants in this scenario, two teachers, two researchers, social robot, and the child. |

| Activity description | [52], page 0357 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A social robot NAO is talking with a child. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a classroom of special school, in 4 sessions. |

| Variation | - |

| Reference: [52], 2021 | Name of Scenario: Physical Activities with NAO Robot. |

| Objectives | Initiation of physical movements. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Basic communication domain, Social and communication interaction due to ASD. |

| Treatment technique | Provocation of imitation of physical movements. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Age | 5–24 years old (4 children) |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are five participants in this scenario, two teachers, two researchers, social robot, and the child. |

| Activity description | [52], page 0357 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A social robot NAO is talking with a child. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a classroom of special school, in 4 sessions. |

| Variation | - |

| Reference: [54], 2021 | Name of Scenario: I like to eat popcorn |

| Objectives | Learning Bulgarian Sign Language. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Demonstration of signs, video and pronunciation of words from Sign Language. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are two participants in this scenario social robot (instructor) and the typically developed toddler. |

| Age | 5 years |

| Activity description | [54] page 72–73 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot Pepper. |

| Used software | NAOqi v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario has been carried out in a lab setting, in one session. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [49], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Different activities between a robot and children |

| Objectives | To present a robotic assistant which can provide support during therapy and can manage the information. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Communication disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Tasks and exercises for language, pragmatics, phonetics, oral-motor, phonological, morphosyntactic, and semantic interventions. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social and cognitive. |

| Interaction technique | Robot–child interaction. |

| Age | - |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The participants in this scenario are the robot and 32 children of regular schools. |

| Activity description | [49], see pages 4–6 |

| Robot configuration and mission | The robot was designed via 3D technology, and has a humanoid form with possibility to wear any costume representing animals (dogs, cats, etc.), children (boys or girls), or any other characters. The main controller of the robot (brain). |

| Used software | A Raspberry PI 2 plate that contains the operative system (Raspbian-Raspberry Pi Model 2 B+). |

| Setting and time | The pilot experiment consists of two stages—lab tests to determine robot’s performance (over multiple activities) and analyses of patients’ responses to the robot’s appearance. |

| Variation | The robot offers different activities (playing, dancing, talking, walking, acting, singing, jumping, moving, and receiving voice commands. The system automates reports generation, monitoring of activities, patient’ data management, and others. The robot’s appearance can be customized according to the preferences of the patients. |

| Reference: [36], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Therapy mode |

| Objectives | Development of phonological, morphological, and semantic areas. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language and speech domain; Children with Cerebral Palsy. |

| Treatment technique | The robot displays on its screen some activities related to speech therapy such as phonological, semantic, and morphosyntactic exercises. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Age | 7 years |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are three participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist, social robot, and the child. |

| Activity description | [36], page 4 |

| Robot configuration and mission | SPELTRA (Speech and Language Therapy Robotic Assistant) with a display, |

| Used software | a Raspberry Pi Model 2 B+ (2015); mobile application (Android-Raspberry Pi Model 2 B+,2015). |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a school setting, in three sessions |

| Variation | Generates a complete report of activities and areas of language which the child has worked; it could be used by parents and their children at home. |

| Reference: [55], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Fruit Salad |

| Objectives | Assessment of nonverbal communication behavior and verbal utterances, transferring skills in life. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Nonverbal behavior and Language domain, Children with ASD. |

| Treatment technique | The robot had the role of presenting each trial by following the same repetitive pattern of behaviors: calling the child’s name, looking at each fruit, expressing the pre-established facial expression, and providing an answer at the end after the child placed a fruit in the salad bowl. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Age | 5–7 years |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are three participants in this scenario, an adult, social robot, and the child. |

| Activity description | [55], page 118 |

| Robot configuration and mission | Social robot Probo and plastic fruit toys. |

| Used software | Elan—Linguistic Annotator, version 4.5 |

| Setting and time | This scenario has been carried out in the therapy rooms in three schools, in two sessions. |

| Variation | The game is played in child–adult condition or in child–robot condition. |

| Reference: [56], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Shapes |

| Objectives | Assessment of decoding/understanding words. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Identification; listening and following spoken instructions; Sign Language interpreter helps with the instructions if the child needs it. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are three participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (mediator), social robot (instructor), and the child with hearing impairment. |

| Age | 5–15 years old |

| Activity description | [56], page 257 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO was used with pictures of different shapes and colors. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a school setting, in one session. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [56], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Emotions |

| Objectives | Understanding emotion sounds and naming the emotion, transferring skills in life. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of emotion sounds; Sign Language interpreter helps with the instructions if the child needs it. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Peer interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are three participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (mediator), social robot (instructor), and the child with hearing impairment. |

| Age | 5–15 years |

| Activity description | [56], page 257 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO was used with pictures of emotions. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a school setting, in one session. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [56], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Shopping_1 |

| Objectives | Identification of environment sounds and words pronunciation, transferring skills in life. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of environmental sounds; Demonstration of body movements; Sign Language interpreter helps with the instructions if the child needs it. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Peer interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are three participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (mediator), social robot (instructor), and the child with hearing impairment. |

| Age | 5–15 years |

| Activity description | [56], page 257 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO and hygienic products (soap, shampoo, sponge, toothpaste and etc.). |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario wascarried out in a school setting, in one session. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [56], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Shopping_2 |

| Objectives | Identification of sentence and words pronunciation, transferring skills in life. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of sentence; categorization of words according to a certain criterion; Sign Language interpreter helps with the instructions if the child need. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Peer interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are three participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (mediator), social robot (instructor), and the child with hearing impairment. |

| Age | 5–15 years |

| Activity description | [56], page 258 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO and toys. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a school setting, in one session. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [57], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Order a doughnut |

| Objectives | How to order a doughnut from a menu in a doughnut shop, transferring skills in life. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, ASD. |

| Treatment technique | Imitation of actions and words. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The child’s family, the robot programmer, the special education teacher, social robot NAO, and the child. |

| Age | 6 years old |

| Activity description | [57], page 132–133 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO and a menu |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out at subject’s home, in two sessions. |

| Variation | - |

| Reference: [57], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Joint Attention |

| Objectives | Joint attention skills |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Joint attention; Developmental Delay and Speech-Language Impairments. |

| Treatment technique | Understanding instructions. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The robot programmer, the speech and language pathologist, social robot NAO, and two children. |

| Age | 7 and 9 years old |

| Activity description | [57], page 135 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO and objects in speech and language pathologist’s office. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out at speech and language pathologist’s office in five sessions. |

| Variation | After each session, the modification of the robot behaviors were designed according to the child’s needs. |

| Reference: [57], 2016 | Name of Scenario: Joint Attention, Turn-Taking, Initiative |

| Objectives | Joint attention, introduction of turn-taking and initiative skills |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Speech-Language Impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Imitation of actions and sentences. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The robot operator, the speech and language pathologist, social robot NAO, and a child |

| Age | 7 years |

| Activity description | [57], page 136–137 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO and cue cards. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out at school’s playroom, in eight months, twice a week sessions. |

| Playing the game without the cue cards. | |

| Reference: [48], 2015 | Name of Scenario: Auditory Memory Stimulation, Comprehensive Reading, Visual Stimulation, Stimulation of Motor Skills |

| Objectives | To offer a robotic assistant able to provide support for Speech Language Practitioners. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome, Cerebral Palsy, Mild and Moderate Intellectual Disability, Epilepsy, Unspecified intellectual disabilities, other disabilities. |

| Treatment technique | Interactive therapy exercises, assessment tasks. |

| Play type | Social and cognitive. |

| Interaction technique | Therapist–patient interaction via an intelligent integrative environment. |

| Age | - |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The participants in this scenario are the therapist, the children, the robotic assistant (the model can be used by relatives and students, too). |

| Activity description | [48], page 75 |

| Robot configuration and mission | RAMSES (v.2)—an intelligent environment that uses mobile devices, embedded electronic systems, and a robotic assistant. The robotic assistant consists of a central processor (an Android smartphone or tablet, or an embedded electronic system) and a displacement. |

| Used software | Electronic platform. |

| Setting and time | This is a pilot study, conducted in clinical settings over multiple activities. |

| Variation | The proposed model relies on different ICT tools, knowledge structures, and functionalities. |

| Reference: [58], 2014 | Name of Scenario: The impact of humanoid robots in teaching sign languages |

| Objectives | Teaching Sign Language |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Demonstration of sign language and special flashcards illustrating the signs. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Age | 9–16 years (10 children hearing impairment). |

| Participants’ role and behavior | Individual and group sessions of a therapist in sign language, a social robot, and a child/ children. |

| Activity description | [58], page 1124–1125 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A social robot Robovie R3 and pictures of sings. |

| Used software | Robovie Maker 2 software (v.1.4). |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a computer laboratory, in one session. |

| Variation | Individual or group sessions. |

| Reference: [59], 2014 | Name of Scenario: Sign Language Game for Beginners |

| Objectives | Learning signs from Turkish Sign Language |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of words in Turkish Sign Language for beginners’ level (children of early age group), most frequently used daily signs. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Age | Average age of 10:6 (years:months) |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are two participants in this scenario, the typically developed child and a humanoid social robot (instructor). |

| Activity description | [59], page 523, 525 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A social robot NAO H25 and a modified Robovie R3 robot. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario wa carried out in a university setting for one session. |

| Variation | The game can also be played with children with hearing impairment. |

4.1.2. Description of Interactive Scenarios with SARs (Empirical Use Studies)

Table 2 presents interactive scenarios with SARs described in empirical use cases.

Table 2.

Description of human–robot interactive scenarios—empirical.

Table 2.

Description of human–robot interactive scenarios—empirical.

| Reference: [60], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Ling Six-Sound Test |

|---|---|

| Objectives | Assessment of auditory skills/identification. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Frequency speech sounds, children with neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Discrimination and identification of speech sounds. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are four participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game), a social robot (instructor-Nao), a social robot EmoSan (playmate), and a child with neurodevelopmental disorders (playmate). |

| Age | 3–10 years old |

| Activity description | [60], page 491 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO; a social robot EmoSan was used with pictures of different speech sounds. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 and Python 2.7. |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The instructions play in random order. The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [60], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Warming up |

| Objectives | Identification of speech. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Common greeting and introduction of someone, children with neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of speech. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are four participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game), a social robot (instructor-Nao), a social robot EmoSan (playmate), and a child with neurodevelopmental disorders (playmate). |

| Age | 3–10 years old |

| Activity description | [60], page 491 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO, a social robot EmoSan. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 and Python 2.7. |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [60], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Farm animals—receptive vocabulary |

| Objectives | Receptive vocabulary of children for this particular closed set of words. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Receptive vocabulary of closed set of words, children with neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of vocabulary of closed set of words. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child-robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are four participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game) a social robot (instructor-Nao), a social robot EmoSan (playmate) and a child with neurodevelopmental disorders (playmate). |

| Age | 3–10 years old |

| Activity description | [60], page 492 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO, a social robot EmoSan has been used with pictures of different farm animals. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 and Python 2.7. |

| Setting and time | This scenario has been carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The instructions are played in random order. The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [60], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Colors. |

| Objectives | Receptive vocabulary of children for this particular closed set of words. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Receptive vocabulary of closed set of words, children with neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of vocabulary of closed set of words. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are four participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game), a social robot (instructor-Nao), a social robot EmoSan (playmate), and a child with neurodevelopmental disorders (playmate). |

| Age | 3–10 years old |

| Activity description | [60], page 492 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO; a social robot EmoSan has been used with pictures of different colors. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 and Python 2.7. |

| Setting and time | This scenario has been carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The instructions are played in random order. The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [60], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Shopping game |

| Objectives | Identification of environmental sounds and expressive vocabulary of closed set of words, transferring skills in life. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Identification of sounds and expressive vocabulary of closed set of words, children with neurodevelopmental disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Identification of sounds and words. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child-robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are four participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game), a social robot (instructor-Nao), a social robot EmoSan (playmate), and a child with neurodevelopmental disorders (playmate). |

| Age | 3–10 years old |

| Activity description | [60], page 492 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO; a social robot EmoSan was used with pictures of different colors. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 and Python 2.7. |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The instructions are played in random order. The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [61], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Imitation games and speech therapy sessions |

| Objectives | To compare the children’s engagement while playing a mimic game with the affective robot and the therapist; to assess the efficacy of the robot’s presence in the speech therapy sessions alongside the therapist. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language disorders. |

| Treatment technique | Mimic game; speech therapy sessions. |

| Play type | Social and cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Robot–child–therapist interaction. |

| Age | Average age of 6.4 years. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The participants in the scenarios are the social robot (RASA), six children in the intervention group, six children in the control group, and the therapist. |

| Activity description | [61], pages 10–11 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A humanoid Robot Assistant for Social Aims (RASA). Designed to be utilized primarily for teaching Persian Sign Language to children with hearing disabilities. |

| Used software | The robot is controlled by a central PC carrying out high level control, and two local controllers. |

| Setting and time | Scenarios have been carried out in a clinical setting over ten therapy sessions (one per week). |

| Variation | The robot uses external graphics processing unit to execute facial expression recognition due to the limited power of the robot’s onboard computer. |

| Reference: [12], 2022 | Name of Scenario: Reading skills |

| Objectives | Social robots are used as the tutor with the assistance of a special educator. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Special Learning Disorder (dyslexia, dysgraphia, dysorthography). |

| Treatment technique | Teaching cognitive and metacognitive strategies. |

| Play type | Cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Robot–child interaction enhanced by the special education teacher; |

| Age | mean age 8.58. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | All scenarios were similar in content; structure and succession for both the NAO and the control group with the only difference that the welcoming, the instructions, the support, and the feedback for the activities was delivered by the special educator for the control group. |

| Activity description | [12], pages 5–4 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A humanoid robot Nao. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23. |

| Setting and time | Interventions took place in a specially designed room in a center; 24 sessions with a frequency of two sessions per week |

| Variation | - |

| Reference: [14], 2021 | Name of Scenario: Therapy session with EBA. |

| Objectives | Formulation of questions and answers, Comprehension and construction of sentences, Articulation and pronunciation, Voice volume, Dictations, Literacy, Reading comprehension |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Treatment domain—nasality, vocalization, language, attention, motivation, memory, calculation, visual perception; children with language disorders—cleft palate and cleft lip, ADHD, dyslexia, language development delay. |

| Treatment technique | Story-telling, making dictations to check the spelling, asking questions about the text that has been read or listened, ask the child for words starting with a letter or will ask the child to identify how many syllables are contained in a word told, to repeat more clearly everything the child does not say properly, give instructions to the child for all the activities defined. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Social and cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Robot-child-therapist interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are 3 participants in this scenario, a speech and language therapist (control the game) a social robot Nao and the child with language disorder. |

| Age | 9–12 years old (five children) |

| Activity description | [14], page 8–9 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO has been used, preprogrammed with the modules: reading comprehension; dictations, stories and vocabulary, improvement of oral comprehension; articulation and phonetic-phonological pronunciation; phonological awareness and phonetic segmentation; literacy skills. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 and Python 2.7. |

| Setting and time | Thirty-minute sessions with children were conducted once a week for 30 weeks. The intervention was conducted during ordinary therapy sessions in a room at the speech therapist centre. |

| Variation | Possible software modifications for different behaviors and scenarios. |

| Reference: [44], 2020 | Name of Scenario: Different scenarios for child–robot interaction |

| Objectives | To achieve significant changes in social interaction and communication. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Different speech and language impairments—specific language impairment, ADHD, dyslexia, oppositional defiant disorder, misuse of oral language, dyslalia, ADD, problems with oral language, nasality, vocalization. |

| Treatment technique | Logopedic and pedagogical therapy. |

| Play type | Social and cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Robot–child–therapist interaction. |

| Age | 9–12 years old (9,10,12) |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The participants in this scenario are the social robot (instructor), five children, the therapist, and a researcher-programmer. |

| Activity description | [44], page 564–565 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A social robot NAO was used, preprogrammed with the modules: reading comprehension; dictations, stories and vocabulary, improvement of oral comprehension; articulation and phonetic-phonological pronunciation; phonological awareness and phonetic segmentation; literacy skills. |

| Used software | NAOqi v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions—once a week for 30 weeks. |

| Variation | Possible software modifications for different behaviors, faster modules, and adaptation to unpredictable scenarios. |

| Reference: [35], 2020 | Name of Scenario: Physically explore the robot |

| Objectives | Joint attention, identification of emotional expressions. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language disorders in children with complex social and communication conditions. |

| Treatment technique | Cause and effect game. |

| Play type | Social and cognitive play. |

| Interaction technique | Robot–child–therapist interaction. |

| Age | From 2 to 6 years. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | The participants in the scenarios are the social robot Kaspar, staff at the nursery, teachers and volunteers, children with complex social and communication conditions. |

| Activity description | [35], pages 306–307 |

| Robot configuration and mission | A social robot Kaspar. |

| Used software | The robot is controlled by a specific Kaspar software that have been developed to facilitate semi-autonomous behavior and make it more user-friendly for non-technical users. |

| Setting and time | Scenarios were carried out in a nursery and the children interacted with the robot for as many sessions as were deemed meaningful within the day-to-day running of the nursery. Number of interactions with the robot per child was 27.37 and the standard deviation was 18.62. |

| Variation | The robot Kaspar can be used in different play scenarios. |

| Reference: [15], 2019 | Name of Scenario: Ling sounds story |

| Objectives | Acquisition of hearing skills. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Ling sounds, auditory-verbal therapy method. |

| Play type (social/cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are two participants in this scenario, a social robot (instructor) and the individual who has hearing impairments (learner). |

| Age | 3–4 years old |

| Activity description | [15], page 442 |

| Robot configuration and mode of operation | A social robot NAO was used with toys correlated with the Ling sounds. |

| Used software | NAOqi software v.2.8.6.23 |

| Setting and time | This scenario was carried out in a clinical setting over multiple sessions. |

| Variation | The level of difficulty can be adjusted. The activity can also include more participants to promote cooperative play. |

| Reference: [15], 2019 | Name of Scenario: Music density |

| Objectives | Acquisition of hearing skills. |

| Treatment domain, Type of CD | Language domain, Language disorder due to hearing impairment. |

| Treatment technique | Listening of environmental sounds; discrimination and identification; sound intensity, auditory-verbal therapy method. |

| Play type (social∣cognitive) | Cooperative and practice play. |

| Interaction technique | Child–robot interaction. |

| Participants’ role and behavior | There are two participants in this scenario, a social robot (instructor) and the individual who has hearing impairments (learner). |

| Age | 3–4 years old |