Abstract

We propose a novel design approach for pinning control of a dynamical network that achieves synchronization despite switching between arbitrary topologies. Unlike existing approaches, we consider weighted, directed, and even unconnected topologies as admissible connections that can be switched instantly. We present a selection algorithm that uses the current topology to identify a suitable set of nodes for control. Additionally, we consider a fixed pinning strategy to activate the required controllers to achieve synchronization, with their gains computed via adaptation laws based only on the neighbors of each pinned node. We derive sufficient conditions for the emergence of a stable synchronous state using common Lyapunov function theory and illustrate their efficacy through numerical simulations of networks that can switch instantaneously between arbitrary topologies.

MSC:

34D06; 05C82; 34H10

1. Introduction

Dynamical networks are models of complex systems that highlight the significance of their connection structure in the overall behavior of the system [1]. The emergence of collective coordinated behaviors in time, i.e., synchronization, is one of the most studied phenomena in complex systems [2,3,4,5,6]. Examples can be found in biology, e.g., fireflies flashing at the same time or correlated neuronal firing; in mechanics, as in interconnected pendulums oscillating at the same frequency; and in many other examples [1,2,5]. However, in some cases, coordinated behavior can be established only by applying control actions, a process often referred to as controlled synchronization [2].

In large-scale networks, it is prohibitively costly, or even impossible, to apply control to every node. Therefore, the only feasible strategy is to select a small subset of nodes to be controlled judiciously; these nodes are pinned to the desired solution, whereas the remaining nodes are uncontrolled. This strategy is referred to as pinning control [7]. The main challenge in this approach is determining how many and which nodes must be controlled to enforce the desired solution across the entire network. Assuming that the control objective is achievable, i.e., the network is controllable [8], the choice of controlled nodes is a question of efficiency, since many different sets of pinned nodes can achieve the control objective; deciding which set of nodes is the best choice remains an open problem [4,9].

In numerous real-world complex systems, the underlying communication structure can change abruptly due to link failures, node additions, or removals, leading to sudden structural changes in the network. Abrupt changes can be seen as structural faults that can be resolved using optimal control, as presented in [10]. One way to model a simplified version of these cases is via a switching network, that is, a dynamical network in which the coupling term includes a switching law that specifies which connection structure is valid at each time instant [5]. This addition to the complex network model significantly affects the network’s stability. Since the dynamics of a network are closely related to its structure, as the structure changes, so does the stability of its collective dynamics [11,12].

Synchronization in networks with switching topology was studied from the perspective of switched systems in [5]. In the case of arbitrary switching, the emergence of synchronization for a set of admissible connection structures is determined by stability analysis via a common Lyapunov function. On the other hand, if one is allowed to design their switching law, the network can be synchronized by solving the stabilizability problem using the dwelling-time approach. Furthermore, for an arbitrarily switching network where all admissible topologies are diffusive and undirected, i.e., represented by symmetric Laplacian matrices, the synchronization problem is solvable with pinning control in the form of linear state feedback control that switches along the topology to pin the appropriate nodes for each admissible structure [13]. Complicating the problem further, in [14], the case of directed switching networks was solved by finding strongly connected clusters in the directed network and applying control to each component to achieve control over the entire network.

Adaptive control strategies are commonly used to overcome unknown values and uncertainties in dynamical systems. An example of a recent application of neural-network-based adaptive control to chaotic systems synchronization is presented in [15]. When applied to networks, adaptive control usually adjusts the coupling strength to make the synchronized solution asymptotically stable [16,17]. In the case of switching networks, adaptive control was successfully applied to synchronize networks that arbitrarily switch between symmetric Laplacian matrices by adaptively modifying the control gains for the pinned nodes in response to unknown changes in dynamics caused by network structure commutation [18,19,20]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the problem of pinning synchronization in networks with arbitrary switching between directed general connection topologies remains open.

Unlike previous approaches, we consider a network that arbitrarily switches between general weighted directed topologies. That is, we do not restrict the admissible topologies to symmetric Laplacian connections; instead, we consider weighted and directed connections, including the case in which not all nodes are connected. Given the varied nature of connection topologies, we design a pinning control approach that adjusts the required control gains via locally defined adaptation rules. Furthermore, the pinning strategy is complemented by a selection algorithm that identifies the set of nodes required to achieve synchronization, regardless of the connections active at each time instant. The main contributions of this paper are (1) an algorithm providing a methodology to select the necessary pinned nodes that are required to synchronize a network regardless of the weighted, directed, or even unconnected nature of its topology; and (2) an adaptive pinning controller that achieves network synchronization despite arbitrary topology switching by adjusting the controller gains via a local adaptive law.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, the synchronization problem is described in detail along with the generalizations of previous approaches. The main results are presented in Section 3, where a selection algorithm is proposed to identify the required pinned nodes along with an adaptive control law that adjusts the corresponding pinning gains to guarantee asymptotic synchronization. In Section 4, we use numerical simulations to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed design. Finally, the contribution is concluded with a discussion and closing remarks.

2. Problem Statement

Consider a switching dynamical network of N identical nodes given by

where is the state variable for the i-th node; is a nonlinear function that describes the dynamic of a node in isolation. We assume that around a desired trajectory , the following inequality is satisfied locally around the synchronous manifold

for and with a positive constant. Numerous authors have proposed similar assumptions that restrict the dynamics of an isolated node in the network, including bounds on quadratic error, the QUAD condition, and sector dominance, among others. It is important to note that many well-known benchmark chaotic systems satisfy Equation (2), including Lorenz, Chen, and Chua’s systems [13,21,22]. Additionally, note that from Equation (2) we can only guarantee local asymptotic synchronization. Global synchronization would require more general or stronger conditions, which are outside the scope of this work.

The internal coupling matrix, , describes which states are connected and is assumed to be the same for all connections. The coupling structure of the network is established with a switching law

which is piecewise constant and continuous from the right function. At each time instant, indicates a single active connection topology from the set of possible connections M. We assume that the transition from one connection to the next is instantaneous and arbitrary, with irregular dwell times between transitions. Therefore, an averaging approach such as that used in [16] is not applicable. Additionally, we assume that switching is arbitrary, but it has a bounded switching speed. Therefore, infinite switching behavior, such as the Zeno phenomenon, is avoided, ensuring that stability analysis based on common Lyapunov functions is applicable.

The active connection topology is described by the matrix , where if the i-th node is connected to the j-th in the active topology indicated by , with and if they are not connected. In the literature, the most commonly used connection topology is an unweighted, undirected, and diffusive connection, that is, and the diagonal elements are given by

For this connection, is a symmetric Laplacian matrix that is row- and column-sum-zero and negative semidefinite. If there are no isolated nodes in the network, the Laplacian is irreducible, and only one of its eigenvalues is equal to zero. Therefore, its eigenvalues can be arranged as follows:

In this contribution, in addition to the unweighted symmetric Laplacian matrix, we considered the case where weights are positive real values () and diffusive ( for ), resulting in a weighted symmetric Laplacian with an eigenvalue spectrum that satisfies Equation (5). We also consider that the weighted Laplacian becomes directed by letting (); for this case, the Laplacian matrix is no longer symmetric, but if it is zero-sum by rows, then it satisfies Equation (5), but its eigenvalues are complex conjugates. The more general case is a weighted, directed, disconnected topology; that is, the network has isolated clusters. Therefore, the Laplacian matrix is reducible with more than one zero eigenvalue; in fact, the number of zero eigenvalues corresponds to the number of clusters in the connection topology [23]. The zero-row-sum condition, although it may seem restrictive, arises naturally for differential couplings. Moreover, this condition is realistic for many physical and engineered networks, such as flow-conservation networks (e.g., power systems, consensus protocols, chemical reactions). Even in directed and weighted networks, zero-row-sum does not imply symmetry of the Laplacian matrix but does ensure invariance of the synchronization manifold, i.e., that the synchronized trajectory follows the dynamics of the isolated node.

The last term in Equation (1) corresponds to the control inputs with to be designed. We propose using the pinning approach. That is, most of the controllers are set to zero, and only a small number () of controllers are designed to pin the selected nodes to a desired solution, with the overall objective to send the collective behavior of the entire network towards synchronization regardless of the arbitrary switching between different connection topologies. The function is a piecewise constant time function that specifies the set of nodes pinned at each time t. We consider three scenarios or strategies, which are specified in the next section.

For the dynamical network (Equation (1)) identical synchronization is achieved when

In other words, when all the nodes’ trajectories satisfy the following condition:

where the desired common trajectory, denoted as , is called the synchronized solution of the network.

It is important to remark that, under the assumption of zero-sum in the connection structures of Equation (1), its dynamical behavior at the synchronized solution becomes the solution of an isolated node, that is,

with the solution for the entire network given by . Defining the synchronization errors as , Equation (6) can be written as

Therefore, the switching network (Equation (1)) is said to achieve asymptotically identical synchronization if the error is asymptotically stable at least locally at its zero equilibrium point.

3. Main Result

Our goal is to identify the sets of nodes that should be pinned to ensure the stability of the synchronized solution (Equation (7)) of the switching dynamical network (Equation (1)) via local linear feedback controllers, even when the network switches arbitrarily among a set of admissible connections.

We consider network topologies with three properties: weight, direction, and connectivity. Therefore, one has eight distinct types of Laplacian matrices. Notice that, for unweighted, undirected, and connected networks, it is usually sufficient to pin a single node to achieve synchronization [24]. If the topology is additionally weighted, it is preferable to include the connection strength when selecting the node to pin. In the case of directed networks, identifying the minimum set of nodes to pin can be solved using a matching algorithm: select nodes to pin that are roots of expanding trees that cover the entire network [25]. In a more general setting, some node subsets may be unconnected. In this case, inspired by [14], we propose that, for each cluster, at least one node must be pinned, and, depending on the cluster’s connectivity properties, additional nodes may also need to be pinned.

For each admissible coupling matrix , the following algorithm is used to determine the set of nodes that need to be pinned such that synchronization is achieved for this coupling topology. Note that if the active topology is disconnected, the Laplacian matrix has multiple zero eigenvalues corresponding to independent clusters. The proposed algorithm ensures that at least one node is pinned in each cluster, thereby eliminating isolated clusters and guaranteeing asymptotic synchronization of the entire network despite the disconnected nature of the original active coupling topology.

From Algorithm 1 we obtain , which are the nodes to be pinned for the admissible topology with . All the nodes to be pinned in each topology are collected in the set

| Algorithm 1 To determine the set of nodes to be pinned for each coupling matrix for |

|

Algorithm 1 assumes that the set of admissible network topologies and their corresponding structures are known. Consequently, the algorithm is executed offline and independently for each admissible topology. As a result, its computational complexity does not affect the implementation of the proposed adaptive pinning control scheme. While this assumption is restrictive, it enables topology-aware pinning strategies that provide synchronization guarantees under arbitrary switching.

Then, the pinning controllers are

The specific nodes to be pinned are chosen with one of the following three different strategies:

- The controller switches at the same time as the topology, i.e., . In this strategy, when the admissible connection matrix is active, the corresponding set of nodes is pinned. Then, the controller becomes

- The controller switches independently from the topology, i.e., . In this way, the controller switches fewer times than the topology does. That is, the controller is given bywhere each with and is a set of controlled nodes to synchronize a group of admissible topologies.

- The controller is applied to a fixed selection of nodes, that is, constant. Then, the controller does not change,where is the set of nodes that one needs to pin to synchronize all the topologies, regardless of which is active at any given time.

Each strategy has its advantages and shortcomings. The first strategy is the most commonly used in the literature, as stability analysis can be addressed using a standard Lyapunov approach [13]. However, this approach requires the controllers to switch to a potentially different set of nodes whenever the topology changes. In the second strategy, we group the nodes required to synchronize a few topologies into a single set, ; this, in fact, reduces the number of commutations required for control. Finally, in the third strategy, the controller does not switch. Yet it may require pinning more nodes than necessary for any single topology, since all possible topologies need to be considered when determining the set . Strategy III adopts a worst-case design by pinning the union of all required nodes across the admissible topology set. While this guarantees applicability under arbitrary switching, the resulting pinning set may grow significantly as the number or diversity of topologies increases, potentially reducing practical efficiency. For this reason, Strategy III is best interpreted as a conservative baseline, whereas Strategies I and II provide a more balanced trade-off between pinning cost and adaptability.

Once the set of nodes to be controlled has been determined according to one of the strategies discussed above, the corresponding gains with are designed using a local adaptation law of the form

where is a positive constant.

The error dynamics are given by

where and if and otherwise.

Under the adaptive control law (Equation (15)), the controlled network will synchronize if the following theorem is satisfied.

Theorem 1.

If Equation (2) is satisfied, and nodes in Ω are selected for pinning using the algorithm described previously, such that

where γ is the Lipschitz constant for , is the largest eigenvalue of for all time and all values of and ω is a positive constant, then the switched dynamical network (Equation (1)) will synchronize under adaptive pinning control (Equation (15)).

Proof.

Consider the common Lyapunov function

Its derivative is

Since if ,

Using the bound constant we got

where if and otherwise. In vector form,

where . Let be the largest eigenvalue of for all time and all values of . Then,

Since is semidefinite negative and K and are semidefinite positive, then it is guaranteed that is negative. According to the assumption in Theorem 1, ; therefore, the derivative of the Lyapunov function is negative, and the synchronization solution is stable. Furthermore, the control gains will reach a constant value, and the adaptive control will stabilize. □

The analysis presented above focuses on exact synchronization of identical node dynamics across switching network topologies, and does not explicitly account for external disturbances or parametric uncertainties. Our proposed strategy can be extended to heterogeneous networks with uncertain node dynamics; however, this would require substantial changes to the controller design and extensions to the Lyapunov stability analysis, which are beyond the scope of this paper.

4. Numerical Illustrations

Consider a network of 500 identical nodes, each a Lorenz system. We generated fifteen different network topologies. Each topology consists of either a single cluster or a random number of isolated clusters, and each cluster follows one of three possible network models: random, small-world, or scale-free [12]. The fifteen topologies were generated using distinct parameter sets, yielding unique structures and connectivity patterns. The weight of each link in the network is assigned uniformly at random from 0.1 to 5.

The equation that describes the dynamics of each node is

with , and .

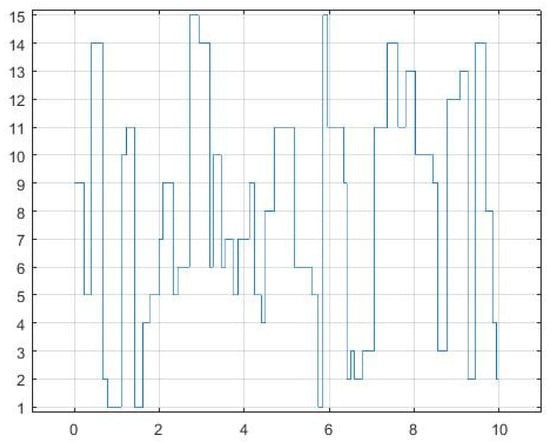

The switching law that determines which topology is active at every time instant is represented in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Switching law of the structure between 15 topologies.

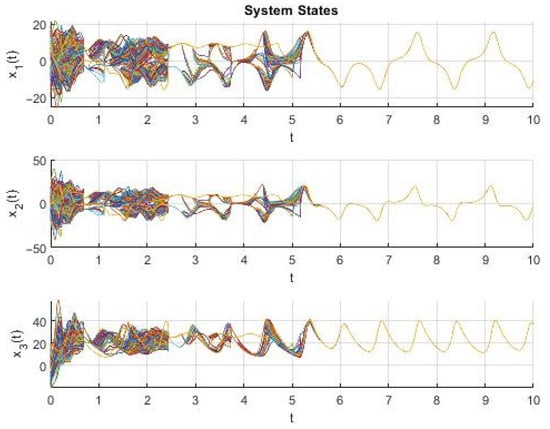

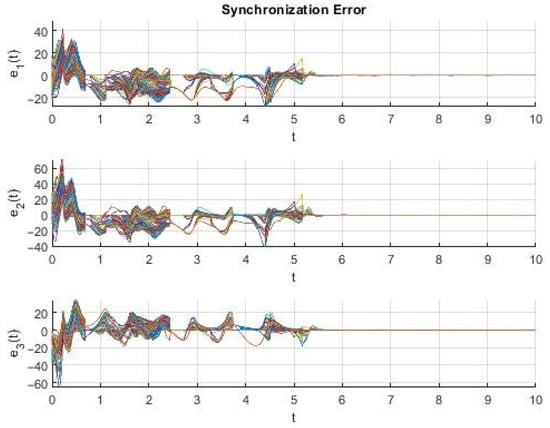

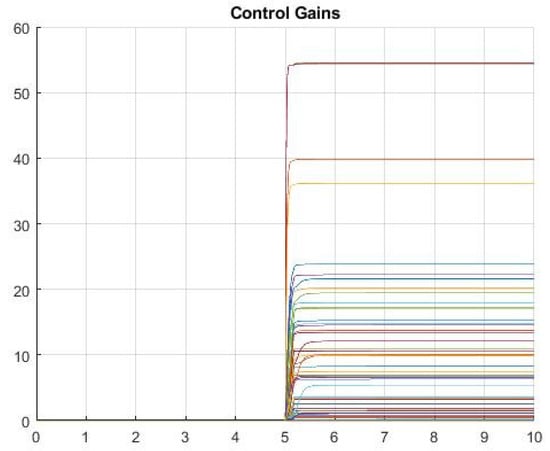

The simulation starts without any control; therefore, no synchronization is observed initially. At time , the adaptive pinning control is activated. Using Algorithm 1, we identify the nodes required for synchronization in each topology. Then, following Strategy III, we select 57 nodes for fixed adaptive control to achieve network-wide synchronization. This number is not guaranteed to be minimal, but it represents a conservative choice that ensures synchronization under arbitrary switching. Initially, each control gain is set to zero. The adaptation velocity parameters are set as . The simulation results are shown in the following figures. The state variables of each node are shown in Figure 2, with the synchronization errors in Figure 3, and Figure 4 presents the adaptive evolution of the control gains for each of the fifty-seven pinned nodes.

Figure 2.

State variables for a network of 500 Lorenz systems that switch between 15 arbitrary weighted and directed topologies with 57 pinned controllers.

Figure 3.

Synchronization error for a network of 500 Lorenz systems that switch between 15 arbitrary weighted and directed topologies with 57 pinned controllers.

Figure 4.

Dynamical evolution of the 57 pinning controller gains for a network of 500 Lorenz systems that switch between 15 arbitrary weighted and directed topologies.

In our numerical simulations, we observe that synchronization is preserved as long as Theorem 1 holds. Therefore, the robustness extends across a broad range of weight distributions and connectivity levels that affect the transient synchronization performance, including convergence speed and the magnitude of the adaptive gains.

5. Closing Remarks

In this work, we present an algorithm for selecting which nodes to pin in a network that switches instantly between arbitrary connections, including disconnected topologies. Additionally, we discuss deploying the pinning controllers with different strategies to activate the corresponding controllers, namely, switching with or independently of the connections. We investigate synchronization behavior using a common Lyapunov function approach, which yields conservative sufficient conditions at the expense of guaranteeing stability under arbitrary switching of network topologies. The switching pinning strategy reduces the number of nodes pinned at each commutation, but it may result in unnecessary switching if some topologies share pinning node sets. Therefore, actively selecting when to switch the sets of pinning nodes may reduce switching in control, though it requires more analysis of each topology and its switching behavior. Algorithm 1 is a centralized, topology-aware procedure that requires full knowledge of the network adjacency matrix to identify connected components and directed trees. This assumption may be restrictive in large-scale networks. However, our algorithm is an offline design procedure for pinning node selection that guarantees synchronization under arbitrary switching among weighted, directed, and possibly disconnected topologies. We illustrate our adaptive pinning design using a fixed selection, which is perhaps more practical since it involves no switching in the control, but may require more energy and be redundant. A detailed comparison of energy consumption across pinning strategies may help determine the optimal choice by measuring the integral synchronization error across configurations. Our preliminary results indicate that this depends on the node dynamics and switching behavior. Therefore, a fixed selection strategy is a good compromise.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, analysis, and validation, I.L.L.-G. and J.G.B.-R.; original draft preparation, I.L.L.-G. and J.G.B.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONACYT of Mexico under 968050 for doctoral studies.

Data Availability Statement

Programs and simulation data are available via direct contact with authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Strogatz, S.H. Exploring complex networks. Nature 2001, 410, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Díaz-Guilera, A.; Kurths, J.; Moreno, Y.; Zhou, C. Synchronization in complex networks. Phys. Rep. 2008, 469, 93–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Chen, G. Synchronization in small-world dynamical networks. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2002, 12, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.F.; Chen, G. Pinning a complex dynamical network to its equilibrium. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2004, 51, 2074–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Hill, D.J.; Liu, T. Synchronization of complex dynamical networks with switching topology: A switched system point of view. Automatica 2009, 45, 2502–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Jiang, H. Pinning synchronization for directed networks with node balance via adaptive intermittent control. Nonlinear Dyn. 2015, 80, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Chen, G. Pinning control of scale-free dynamical networks. Phys. A 2002, 310, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. Pinning control and synchronization on complex dynamical networks. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 2014, 12, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. Pinning Control of Complex Dynamical Networks. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2022, 68, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Puig, V.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Y. Dynamic-High-Gain-Based Decentralized Optimal Fault-Tolerant Control for a Class of Interconnected Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2025, 70, 5823–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, D. Switching in Systems and Control; Birkhauser: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; p. 246. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaletti, S.; Latora, V.; Moreno, Y.; Chavez, M.; Hwang, D.U. Complex networks: Structure and dynamics. Phys. Rep. 2006, 424, 175–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Qiao, F.; Wang, F. Pinning Synchronization of Switched Complex Dynamical Networks. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 45827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Yu, W.; Hu, G.; Cao, J.; Yu, X. Pinning synchronization of directed networks with switching topologies: A multiple Lyapunov functions approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 28, 3239–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Zhao, L.; Jin, J. Preset-Time Convergence Fuzzy Zeroing Neural Network for Chaotic System Synchronization: FPGA Validation and Secure Communication Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turci, L.F.R.; Simoes, M.M.R. Adaptive pinning of mobile agent network. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2015, 26, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLellis, P.; DiBernardo, M.; Porfiri, M. Pinning control of complex networks via edge snapping. Chaos 2011, 21, 033119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, B.; Ghosh, B.K. Formation–Circumnavigation Switching Control of Multiple ODIN Systems via Finite-Time Intermittent Control Strategies. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2024, 11, 1986–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-Z.; Yang, G.-H. Adaptive pinning synchronization of a class of nonlinearly coupled complex networks. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2013, 18, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Geng, H. Pinning consensus control for switched multi-agent systems: A switched adaptive dynamic programming method. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2023, 48, 101319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chen, G.; Lü, J. On pinning synchronization of complex dynamical networks. Automatica 2009, 45, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Wei, P.-C.; Wu, H.-N.; Huang, T.; Xu, M. Pinning synchronization of complex dynamical networks with multiweights. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Networks: An Introduction; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2010; p. 772. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Liu, X.; Lu, W. Pinning complex networks by a single controller. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2007, 54, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Slotine, J.-J.; Barabási, A.-L. Controllability of complex networks. Nature 2011, 473, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.