Abstract

Suppose that with and where p is a prime and is a unit in Then, R is a local non-chain ring of order with a unique maximal ideal and a residue field of order A linear code C of length N over R is an R-submodule of The purpose of this article is to examine MacWilliams identities and generator matrices for linear codes of length N over We first prove that when there are precisely two distinct rings with these properties up to isomorphism. However, for , only a single such ring is found. Furthermore, we fully describe the lattice of ideals of R and their orders. We then calculate the generator matrices and MacWilliams relations for the linear codes C over illustrated with numerical examples. It is important to address that there are challenges associated with working with linear codes over non-chain rings, as such rings are not principal ideal rings.

MSC:

16L30; 94B05; 16P20; 94B60

1. Introduction

Linear codes of length N over a finite ring R are R-submodules of These codes have been traditionally studied over finite fields; however, many significant codes over fields have been related to those over finite rings by Gray maps [1,2,3,4]. In this article, all of the alphabet rings involved are finite, commutative, and have an identity. A ring R is called local if it has a unique maximal ideal, denoted by J (Jacobson radical). When all ideals of R are principal, R is then called the principal ideal ring (PIR). A chain ring is a principal local ring, and thus many conclusions obtained for coding over chain rings also hold over PIRs. One of the main reasons that Frobenius rings, defined later, are considered the appropriate class to describe codes is because they satisfy both MacWilliams theorems. Furthermore, Frobenius local rings can be decomposed into their component parts and this enables us to find their generating characters. To fully understand codes over Frobenius rings, it is therefore necessary, despite the challenges, to consider local non-chain rings [5,6,7]. For more information on the subject, please refer to [5,8,9,10,11] and the references therein.

In this work, the main purpose is to obtain significant coding results over Frobenius local rings. In particular, linear codes of length N over the ring are the focus of this paper. Prior work on these rings was presented in [12], emphasizing their applicability to coding theory, and their close connection to and linear binary codes [3]. Our attention is also on exploring the roles of generator matrices and MacWilliams relations in error-correction theory, particularly in their role to weight enumerators of a code and its dual code. The authors of [6] considered these approaches for Frobenius local rings of order 16. While in [7], generator matrices and the MacWilliams relations were described for codes over rings of order 32. This work makes an effort to build on the previous findings and provides access to more general rings with higher orders. Let , with and as conditions, where the unite group of Initially, we provide a formula for a generating character associated with through which we can calculate the MacWilliams relations as matrices of specific sizes for a code C over For codes over non-chains, it is more challenging to build a generator matrix G than for codes over chains. Although a simple set of generators can still be found, this type of generator matrix may not provide straightforward information about the code size. In this research, we introduce multiple numerical examples that show the code size might not always determined directly from such a generator matrix. Additionally, the generator matrix G of a code C is completely determined through the algorithm described in Theorem 8.

In Section 3, the classification of rings of the form with invariants is described, after the initial definitions and results in Section 2. Particular attention is given to providing all the details necessary to characterize rings of order and to outline the lattice of their ideals. Section 4 provides the general procedure for generating characters for . Additionally, the symmetrized weight enumerator’s corresponding to the matrix is acquired, and MacWilliams relations are derived. In Section 5, the findings regarding matrices that produce linear codes over such rings are presented.

2. Preliminaries

The notations and basic information that will be used later in our discussion are introduced in this section. Let R be a local ring of identity, and let J be its maximal ideal. For the results mentioned in this section, we refer readers to [4,12,13,14,15,16].

The order of J is provided , and the size of is with In R, the characteristic takes the form and . Additionally, R has a subring , of the form called a Galois ring with Moreover, there is and

If J is principal, then R is chain, and particularly when we have and

where is a root of a specific polynomial Let

Suppose so

where Furthermore, assume that t is the smallest number with condition of We label and t as the parameter (invariants) of

In our later discussion, we use and This implies that and In addition, we consider as

where From [12],

where

The total sum of all minimal ideals in R is what we define as the socle of also known as soc As R is commutative, thus

We will highlight the definition of Frobenius rings that is most pertinent to our analysis. In [14], R is called Frobenius if

Let denote the character group of then elements of are called characters of If ker has no non-trivial ideals of then is named a generating character.

Theorem 1

(Honold [14]). Let R be a finite ring. Then, soc is cyclic, if and only if R is a Frobenius ring.

A code C of length N over R is a subset of ; it is called a linear code if C is a submodule [4]. Furthermore, by including the inner-product (·) in , we can define the dual code of C as follows

3. On the Ring

In this section, we prove some results on the ring which is a finite ring of order and with residue field These results help us in the subsequent discussion.

Theorem 2.

The ring is a Frobenius local ring.

Proof.

As each element of R is uniquely written where and Also, as then R is a local ring of order and In fact, R is a local ring with a singleton basis and We now prove that R is Frobenius. Because elements of soc annihilates particularly then Thus, soc Suppose soc and Then, in particular, This implies that but as will also lead to Hence,

Using Theorem 1, R is Frobenius. ☐

Corollary 1.

As then R is a non-chain singleton ring.

Remark 1.

For any Frobenius local ring R with invariants and then

3.1. Determination of Rings of Order with

An exhaustive characterization of all rings with is given by Theorem 3, which is essential for our upcoming discussion.

Theorem 3.

Assume that R is a ring and that is its invariant. Then, among the rings given in Table 1, R is isomorphic to one particular ring.

Table 1.

Rings of order with .

Proof.

Every element of R is uniquely expressed as where and As then the associated polynomial is of the form where Suppose that As hence there exists precisely one class represented by

From now, we assume that Consider the usual partition on

It is worth noting that We next proceed the proof with two cases.

- Case a. We show that and are not isomorphic, that is, they are not in the same class when . In contrast, suppose that , and define the isomorphism as . Assuming for some . Consequently, we noteWe have , because restricted to is a fixed isomorphism. Furthermore, because this contradicts the assumption about and thus Therefore,

- Case b. When In such a case, there exists such that Note thatAs u is a root of then and hence This implies that, from the above argument, Thus, This suggests that for can be taken as , which is identical to that of As a result, To sum up, we have two classes of such rings that are not isomorphicThe first class is represented bywhere is any element in While the second class is represented by

☐

Corollary 2.

Let be the number rings with Then,

Proof.

The proof is direct from the proof of Theorem 3 with and . ☐

3.2. Lattice of Ideals of R

Theorem 4.

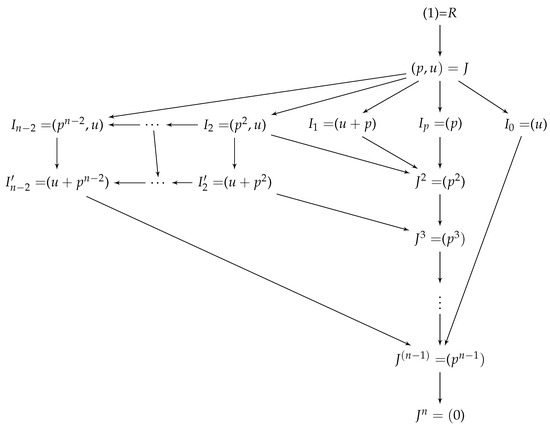

The ideals of R is given by the following lattice (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lattice of ideals of .

Proof.

Consider a proper ideal of R, I. As R is local, J represents the only maximal ideal of R; hence, This indicates that I is generated by a combination of p and u and their powers. Given that and we have where Thus, we only consider ideals generated by and u and their combinations. In other words, without raising J to a power, there are only n choices for namely

where and First, note that where It is clear that and , and, moreover, where Thus, if and

As thus Finally, we justify that where As then If then Now, if then and hence Therefore, the results follow. ☐

Corollary 3.

Suppose R as in Theorem 4. Then, for

Remark 2.

Two non-isomorphic rings can have the same ideal lattice.

Remark 3.

Theorem 4 states that every ideal of R contains soc

Example 1.

The ring is a Frobenius local non-chain ring. Because the assumption of Theorem 2. Note that soc and .

3.3. Units of

The form of the units of R will be established in this subsection, which will be useful in the following section. The elements in are the units of R, as R is local. Furthermore, because if

where and The elements of can be written as

where and for Thus, can be expressed as

where and In other words,

where Moreover, observe that , as Consequently, the following theorem is established.

Theorem 5.

Every element v of is of the form or where and . Moreover, is of order and

Example 2.

If then the units of R are of the form

4. MacWilliams Identities

With as invariants and , let R be a Frobenius local ring. Theorem 6 outlines a method to produce a generating character for any such ring. Suppose is a -root of unity and for each

Theorem 6

([7]). Let R be a ring with There is , such that and

is a generating character of

The formulas of for R are shown in the following Table 2, where , and are the th, pth, and th roots of unity, respectively.

Table 2.

for the ring R.

The MacWilliams identities for various version of R are now computed. Actually, the class of all Frobenius rings is a broader class of finite rings to which these relationships can be extended. These identities are fundamental to the study of coding theory because they introduce a crucial link between a code’s dual and weight enumerator. Assume the following: The elements in are in that order. Suppose C is a linear code over R with length N. Let us assume that is the number of instances of in c. The complete weight enumerator is then denoted as

where and We define The Hamming weight (HW) enumerator and its MacWilliams identity are given by

Suppose that ∼ is defined on R by when there is , such that It is evident that this relation is equivalent. Let be the equivalence classes and let calculate the number of elements of that occurred in the codeword c. Hence, SWE is defined as follows

We introduce the MacWilliams equation for SWE as

where and

As we can notice, once is obtained, it is straightforward to obtain the matrix A in Equation (11). Nonetheless, S in Equation (15) necessitates the determination of the classes While it takes more work, this procedure is essential for building If we look at the broader case for that is, . Note that in this ring, of order , with as its index of nilpotency, and Then, one can obtain the set of as follows.

For a more general case, we have a detailed scheme for finding in the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

Let Then,

Proof.

Suppose that then . For the other cases, assume that First, let As soc then where and are a representative of Now, also suppose that then for some in It follows that where This means that all elements of are of the form which can be interpreted as the set is just copies of soc Thus,

However, we have the following formula for complex numbers,

The positive reflects the number of copies of soc, which is precisely Therefore,

The last case of the proof can be achieved similarly by noting that every element of can be expressed as where In such a case,

Hence, by Equation (16), we conclude the results. ☐

Theorem 7.

The S matrix for is given as

Proof.

Let us assume that the elements of R are ordered as follows: if then i comes before j if as an integer, and comes before if i precedes The equivalency classes are therefore

Thus, by using Lemma 16 and after making the necessary computations, the results are obtained. ☐

Remark 4.

The matrix S can be obtained for R when but the computations will be tedious.

We then move on to a numerical demonstration of these computations and their steps for examples of rings with We will first concentrate on comprehending under ∼ before building

Example 3.

Suppose that Assuming the order for the elements of R as:

We then compute S, which requires a large number of calculations. The for R that we must obtain are listed as

Therefore, by Theorem 7, we obtain

As a summary, we introduce Table 3 to present S and .

Table 3.

S and for .

Remark 5.

From the above discussion, S is an equivalent matrix for every ring that is examined in this article.

5. Generator Matrices

The remaining content of the article is devoted to Frobenius local rings of order

Definition 1.

If the vectors with coefficients from J cannot be combined linearly in a nontrivial way to equal the zero vector, we refer to the vectors as modularly independent. When the rows of G independently produce the code C, then G is a generator matrix over the ring R.

Remark 6.

Every linear code C over R has a generator matrix G and this matrix is unique up to raw equivalency.

This section finds matrices G that produce linear codes over Building a generator matrix G for codes over non-chains is more difficult than for those over chains. This kind of generator matrix might not provide straightforward information about the code size or number of codewords, even though one can still locate a basic set of generators.

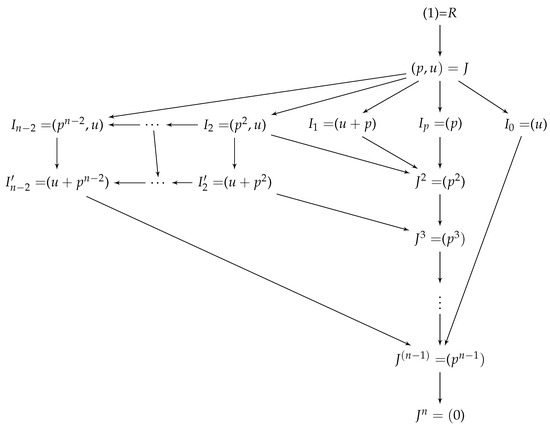

Figure 2 above illustrates ideals of As and Therefore, the goal of this section is to produce a collection of independent modular elements that function as a code’s generator matrix’s rows. A complete description of the structure of G is given by the following theorem.

Figure 2.

Lattice of ideals of .

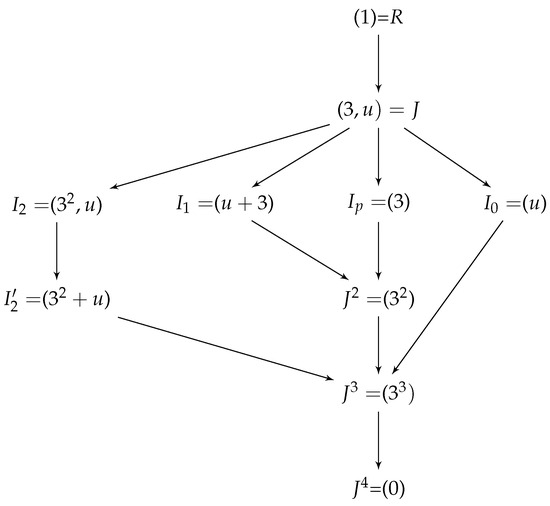

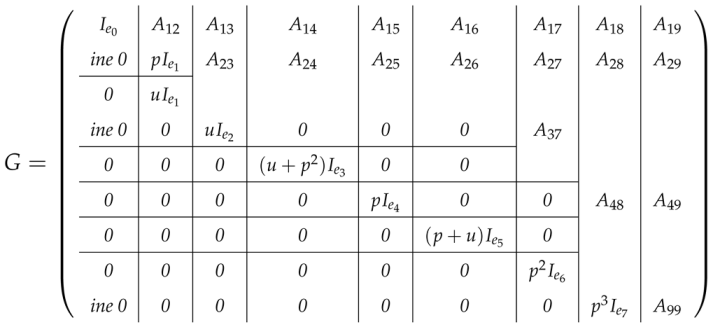

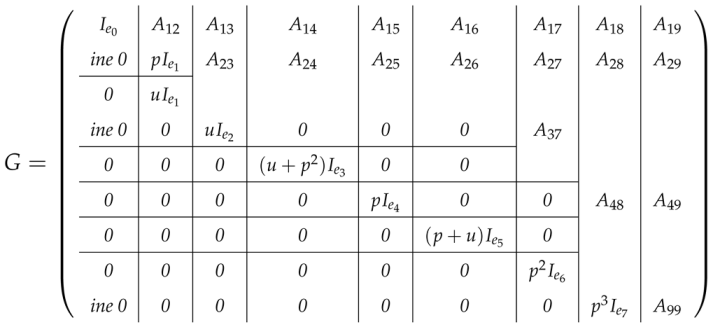

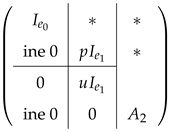

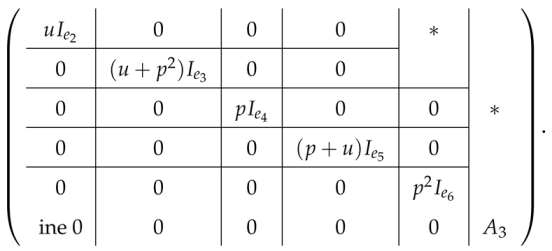

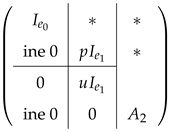

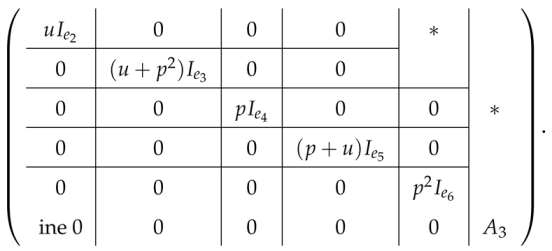

Theorem 8.

Assume C is a linear code with N over. Thus, for any C, any G is raw equivalent to

where Aij are matrices of various sizes.

where Aij are matrices of various sizes.

Proof.

Let G be a matrix such that the rows ’s of the matrix produce C as an R-module. Every column containing a unit is moved to the left of We obtain a matrix of the form by row reduction on those columns,

Now, not every element in A is a unit. To transform the matrix into the next form, we shift all columns containing elements of to the left once more and apply the primary row operations.

We continue with this algorithm, making sure that the matrix is created by putting elements in columns such that they form a pair We keep doing this until the matrix takes on the form that we want.

where only one of (p), (u), (p + u), and (p2 + u) is represented by the elements of the matrix A2’s columns. We will now move over to the matrix A2. The four ideals are (u), (p2 + u), (p), and (p + u). We choose a particular ordering for each ideal for the sake of producing a one expression of the matrix. The matrix will be constructed using this selected order consistently. Assuming v is a unit of R, we proceed as follows: columns with entries of the form uv, columns with elements of the form (u + p2)v, and finally columns with elements of the form (p)v. Lastly, we address columns that take the form (u + p)v. We carry out row reduction in the standard way in each step. Observe that both (p) and (u + p) contain the ideal (p2). Consequently, we redo similar a process with (p2) as the remaining column entries will come from (p2).

where only one of (p), (u), (p + u), and (p2 + u) is represented by the elements of the matrix A2’s columns. We will now move over to the matrix A2. The four ideals are (u), (p2 + u), (p), and (p + u). We choose a particular ordering for each ideal for the sake of producing a one expression of the matrix. The matrix will be constructed using this selected order consistently. Assuming v is a unit of R, we proceed as follows: columns with entries of the form uv, columns with elements of the form (u + p2)v, and finally columns with elements of the form (p)v. Lastly, we address columns that take the form (u + p)v. We carry out row reduction in the standard way in each step. Observe that both (p) and (u + p) contain the ideal (p2). Consequently, we redo similar a process with (p2) as the remaining column entries will come from (p2).

Finally, every component of A3 originates from the ideal that p3 generates. We obtain a matrix that precisely corresponds to the desired form by removing any rows that contain only zeros and completing one last row reduction round. ☐

Finally, every component of A3 originates from the ideal that p3 generates. We obtain a matrix that precisely corresponds to the desired form by removing any rows that contain only zeros and completing one last row reduction round. ☐

Proposition 1.

If and is a R-submodule. Then,

Proof.

Let I be an ideal created by the vector ’s coordinates. Also, let Then,

By Figure 2, ☐

Theorem 9.

Let be R-submodule, where the coordinates of w,v are not units of R. Thus,

Proof.

From Proposition 1, we have As then ☐

Example 4.

To have a code C over of order set with Then, Meanwhile, to construct C with size suppose with and This implies Take and Hence, Therefore,

Example 5 shows a minimal set of generators may not exist for C over a (non-chain) Frobenius local, which makes the code more complex. Stated differently, it highlights the differences in coding over chain rings and that over non-chain rings.

Example 5.

Let G be a generator matrix of the code C over of the form

Assuming that represents the R-submodule produced by and of and the R-submodule produced by

This indicates that the module C cannot be reduced.

6. Conclusions

We conclude that, up to isomorphism, all rings of the form with and have been successfully classified in terms of Furthermore, generator matrices and MacWilliams relations for linear codes over such rings have been discovered. These are popular and effective tools for encoding data over chain rings; codes over local non-chain rings may not be able to achieve such a case. The challenge is in identifying a smallest number of generators and counting the code size because non-chain local rings are not PIRs. This restriction suggests that in order to effectively handle such an issue, different approaches or strategies are needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and A.A.A.; methodology, S.A. and A.A.A.; formal analysis, S.A., A.A.A. and N.A.A.; investigation, S.A. and A.A.A.; writing—original draft, S.A. and N.A.A.; writing—review & editing, S.A., A.A.A. and N.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R871), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Norton, G.; Salagean, A. On the structure of linear cyclic codes over finite chain rings. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput. 2000, 10, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greferath, M. Cyclic codes over finite rings. Discrete Math. 1997, 177, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, S.T.; Saltürk, E.; Szabo, S. Codes over local rings of order 16 and binary codes. Adv. Math. Commun. 2016, 10, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabiad, S.; Alkhamees, Y. Constacyclic codes over finite chain rings of characteristic p. Axioms 2021, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, B.; Karadeniz, S. Linear codes over ℤ4+uℤ4: MacWilliams identities, projections, and formally self-dual codes. Finite Fields Their Appl. 2014, 27, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, S.T.; Saltürk, E.; Szabo, S. On codes over Frobenius rings: Generating characters, MacWilliams identities and generator matrices. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput. 2019, 30, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabiad, S.; Alhomaidhi, A.A.; Alsarori, N.A. On Linear Codes over Finite Singleton Local Rings. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moro, E.; Szabo, S.; Yildiz, B. Linear codes over ℤ4[x]/(x2 + 2x). Int. Inf. Coding Theory 2015, 3, 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sriwirach, W.; Klin-Eam, C. Repeated-root constacyclic codes of length 2ps over Fpm + uFpm + u2Fpm. Cryptogr. Comm. 2021, 13, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaouine, J.; Charkani, M.E.; Wang, L. Complete classification of repeated-root-constacyclic codes of prime power length over Fpm[u]/(u3). Discrete Math. 2021, 344, 112325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhu, S.; Yang, S. A class of optimal p-ary codes from one-weight codes over Fp[u]/<um>. J. Frankl. Inst. 2013, 350, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhamees, Y.; Alabiad, S. The structure of local rings with singleton basis and their enumeration. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendran, R. Finite associative rings. Compos. Math. 1969, 21, 195–229. [Google Scholar]

- Honold, T. Characterization of finite Frobenius rings. Arch. Math. 2001, 76, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moro, E.; Szabo, S. On codes over local Frobenius non-chain rings of order 16. In Noncommutative Rings and Their Applications; Contemporary Mathematics, Dougherty, S., Facchini, A., Leroy, A., Puczylowski, E., Solé, P., Eds.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2015; Volume 634, pp. 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.A. Duality for modules over finite rings and applications to coding theory. Am. J. Math. 1999, 121, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).