Abstract

A quasi-configuration is a point–line incidence structure in which each point is incident with at least three lines and each line is incident with at least three points. We investigate derived quasi-configurations that arise both by duality and intersecting lines of three special arrangements of lines. Sets with few intersection numbers are provided.

Keywords:

quasi-configuration; arrangement of lines; Ceva configuration; Klein configuration; Wiman configuration; sets with few intersection numbers; sets with few characters MSC:

51E20

1. Introduction

In finite geometry, the concepts of points and lines are translated from the continuous to the discrete world. A natural way to make this explicit is by starting with a geometry over the complex field ℂ and replacing the field ℂ by a finite field, 𝔽q, of order q, where q is a power of a prime number, thus obtaining a discrete object. The axiomatic approach to geometry contributes to this point of view, allowing geometries consisting only of a finite number of objects that have many applications in coding theory, data storage, or cryptography. Recall that a point–line incidence structure is a triple (P,L,I), where P is a set of points and L is a set of lines, together with a point–line incidence relation I ⊆ P × L, where two points of P can be incident with at most one line of L, and two lines of L can be incident with at most one point of P. Throughout the paper, we only consider connected incidence structures, where any two elements of P∪L are connected via a path of incident elements.

One of the main problems in the theory of point–line incidence structures is to clarify the existence of regular ones, i.e., in which any line contains the same number of points, and any point is contained in the same number of lines. A (vr,bk)-configuration is a point–line incidence structure (P,L) where the size of P is v, the size of L is b, each point of P is contained in r lines of L and each line of L contains k points of P. In such a configuration, we have that vr = bk. If the number of points is equal to the number of lines, we call it a symmetric (nk) configuration.

A point–line incidence structure (P,L,I) is said to be a quasi-configuration of type if P is a disjoint union of subsets Pi of cardinality pi with i = 1, 2, …, m(P), and L is a disjoint union of subsets Lj of cardinality nj with j = 1, 2, …, m(L), such that each point in Pi is incident with ri lines, and each line in Lj is incident with kj points. Quasi-configurations were introduced in [1] and used as building blocks for larger point–line incidence structures, see also [2]. Note that a quasi-configuration with m(P) = m(L) = 1 is a configuration, and if all the parameters are the same for points and lines we say that it is a symmetric quasi-configuration of type . Let 𝔽 denote a field and consider the projective plane ℙ2 over 𝔽. Let d ≥ 3 be an integer. An arrangement of d lines A is a set of d lines {L1, L2, …, Ld} in ℙ2, such that . For i ≥ 2, an i-point is a point in A which belongs to exact i lines in A. We denote the number of i-points by ti. In characteristic zero, apart from pencil of three or more lines, only three types of complex line arrangements with t2 = 0 are currently known: Ceva, Klein, and Wiman arrangements.

2. Materials and Methods

A finite projective plane is a symmetric configuration, such that two points are contained in exactly one line, two lines meet in exactly one point, and there are four points, three by three not collinear. Finite projective planes are constructed using homogeneous coordinates with entries from a finite field 𝔽q. There are also planes not derived from finite fields, but they are beyond the scope of this research. We will study quasi-configurations which arise both by duality and intersecting lines of these special arrangements of lines, by replacing the field of complex numbers ℂ by the smallest finite field 𝔽q containing them. The idea is that if an arrangement of lines is special, then its derived quasi-configuration is also special. A k-set K in a finite projective plane is a set of k points. A k-set K is said to be symmetric if the number vi(P) of i-secant lines, through a point P of K is the same for any point P. A k-set K is said to be a blocking set if K meets every line. It is minimal if it properly contains no blocking sets. A k-set K is said to be of type (m1, m2, …, ms) if any line has exactly m points in common with K with m∈{m1, m2, …, ms} and every value occurs. The integers m1, m2, …, ms are called intersection numbers. Sets with few intersection numbers define projective linear codes with few weights that are useful in authentication codes, secret sharing schemes, and data storage systems. The paper falls into three sections. In the first, we will prove that, in characteristic 2, the Ceva (3) configuration closes, from the incidence point of view, in a projective plane of order four, and this, to our knowledge, seems to be novel. In the second section, we will show that, in characteristic 7, the Klein quasi-configuration is the set of the internal points of a conic of PG (2,7). Unfortunately, this representation is well known, see [3] (p. 7511), [4] (p. 342), and [5] (p. 121), but we provide direct proof arising from the Singer construction of the quasi-configuration. In the third section, we will prove that, in PG (2,19), the Wiman configuration gives rise to a symmetric minimal blocking 45-set of type (1,3,4,5), which, to our knowledge, seems to be novel.

3. Ceva Arrangements of Lines

Ceva(n) arrangements of lines are defined by the set of zeros of linear factor of the polynomial (xn − yn)(xn − zn)(yn − zn), see [6]. This polynomial splits over a field 𝔽 containing a primitive root of unity of degree n, into the linear factors x − ωky, x − ωkz, y − ωkz, k = 0, 1, …, n − 1. Since dual Ceva (1) is a set of three collinear points and dual Ceva (2) is a complete quadrangle, suppose that the characteristic of the field 𝔽 is not three, and consider Ceva (3). The arrangement consists of the nine lines: x − y = 0, x − ωy = 0, x − ω2y = 0, x − z = 0, x − ω2z = 0, x − ωz = 0, y − z = 0, y − ωz = 0, y − ω2z = 0. Dually, we get a set of nine points:

A: = (0,1,−1), B: = (0,1,−ω), C: = (0,1,−ω2);

P: = (1,0,−1), Q: = (1,0,−ω2), R: = (1,0,−ω);

X: = (1,−1,0), Y: = (1,−ω,0), Z: = (1,−ω2,0).

P: = (1,0,−1), Q: = (1,0,−ω2), R: = (1,0,−ω);

X: = (1,−1,0), Y: = (1,−ω,0), Z: = (1,−ω2,0).

A direct check shows that the nine points of the above point matrix are contained in the twelve lines, three by three, that are rows, columns, and determinantal products. Thus, we get the matrix of the twelve lines:

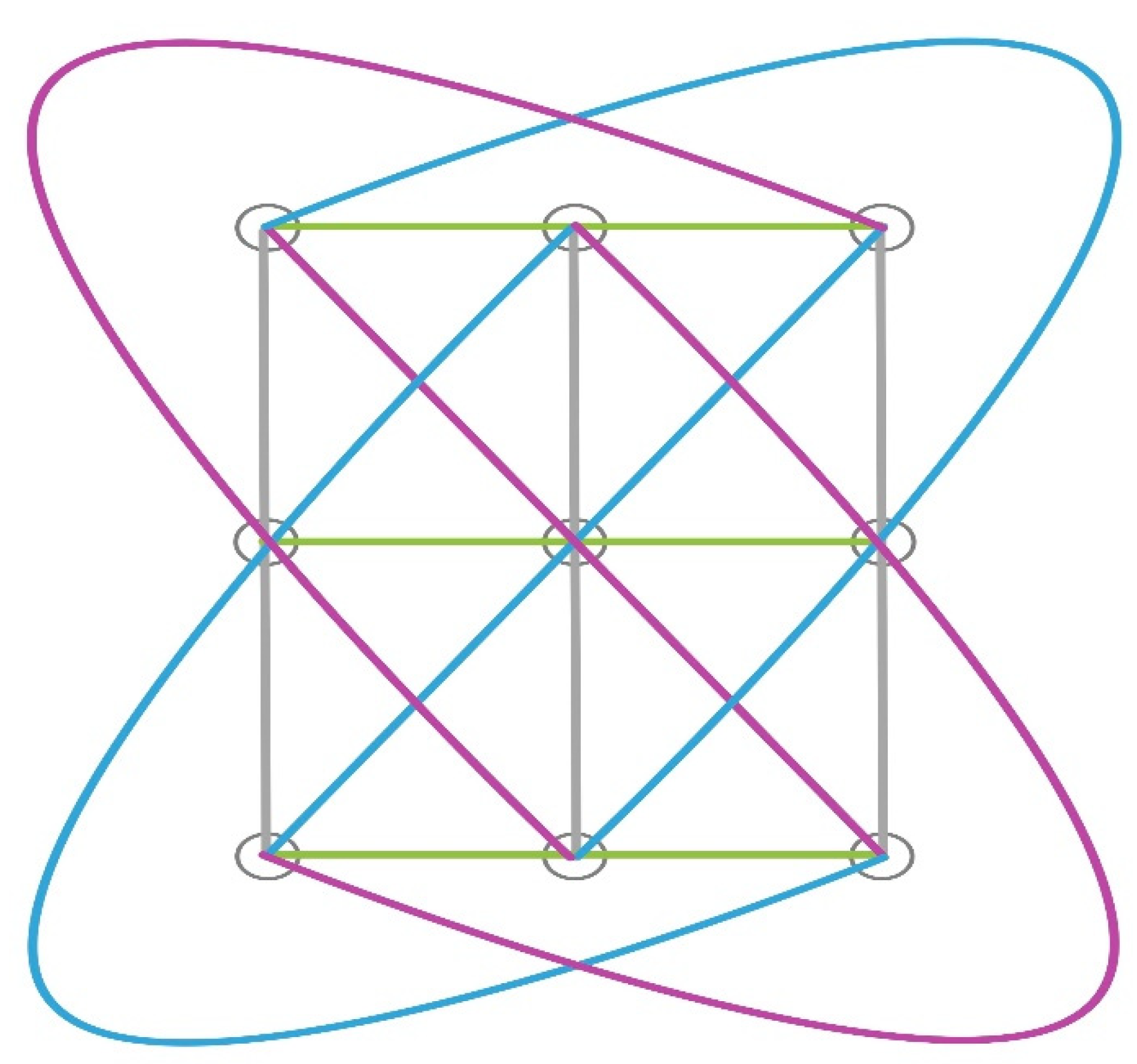

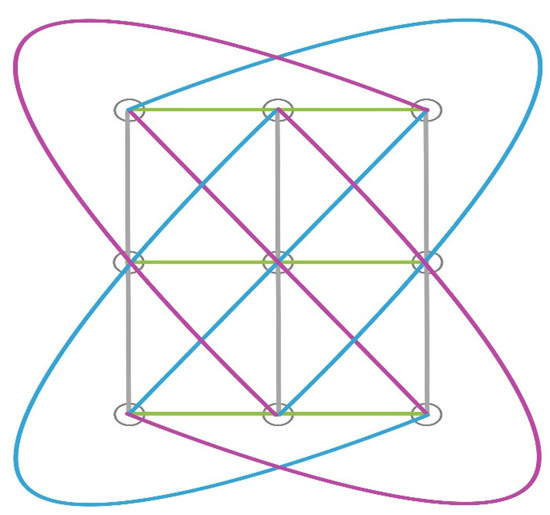

i.e., the Hesse (94,123) configuration as in Figure 1.

ABC: x = 0, PQR: y = 0, XYZ: z = 0;

APX: x + y + z = 0, BQY: x + ω2y + ωz = 0, CRZ: x + ωy + ω2z = 0;

AQZ: x + ωy + ωz = 0, BRX: x + y + ω2z = 0, CPY: x + ω2y + z = 0;

CQX: x + y + ωz = 0, ARY: x + ω2y + ω2z = 0, BPZ: x + ωy + z = 0;

APX: x + y + z = 0, BQY: x + ω2y + ωz = 0, CRZ: x + ωy + ω2z = 0;

AQZ: x + ωy + ωz = 0, BRX: x + y + ω2z = 0, CPY: x + ω2y + z = 0;

CQX: x + y + ωz = 0, ARY: x + ω2y + ω2z = 0, BPZ: x + ωy + z = 0;

Figure 1.

The Hesse (94,123) configuration.

Since the characteristic of the field 𝔽 is not three, then each triple of parallel lines forms a different triangle, i.e., each row of the above line matrix is a triangle whose vertices are written in the rows of the matrix below:

D: = (0,0,1), E: = (1,0,0), F: = (0,1,0);

G: = (1,ω,ω2), H: = (1,ω2,ω), I: = (1,1,1);

L: = (1,ω,1), M: = (1,1,ω), N: = (1,ω2,ω2);

U: = (1,ω,ω), T: = (1,ω2,1), S: = (1,1,ω2).

G: = (1,ω,ω2), H: = (1,ω2,ω), I: = (1,1,1);

L: = (1,ω,1), M: = (1,1,ω), N: = (1,ω2,ω2);

U: = (1,ω,ω), T: = (1,ω2,1), S: = (1,1,ω2).

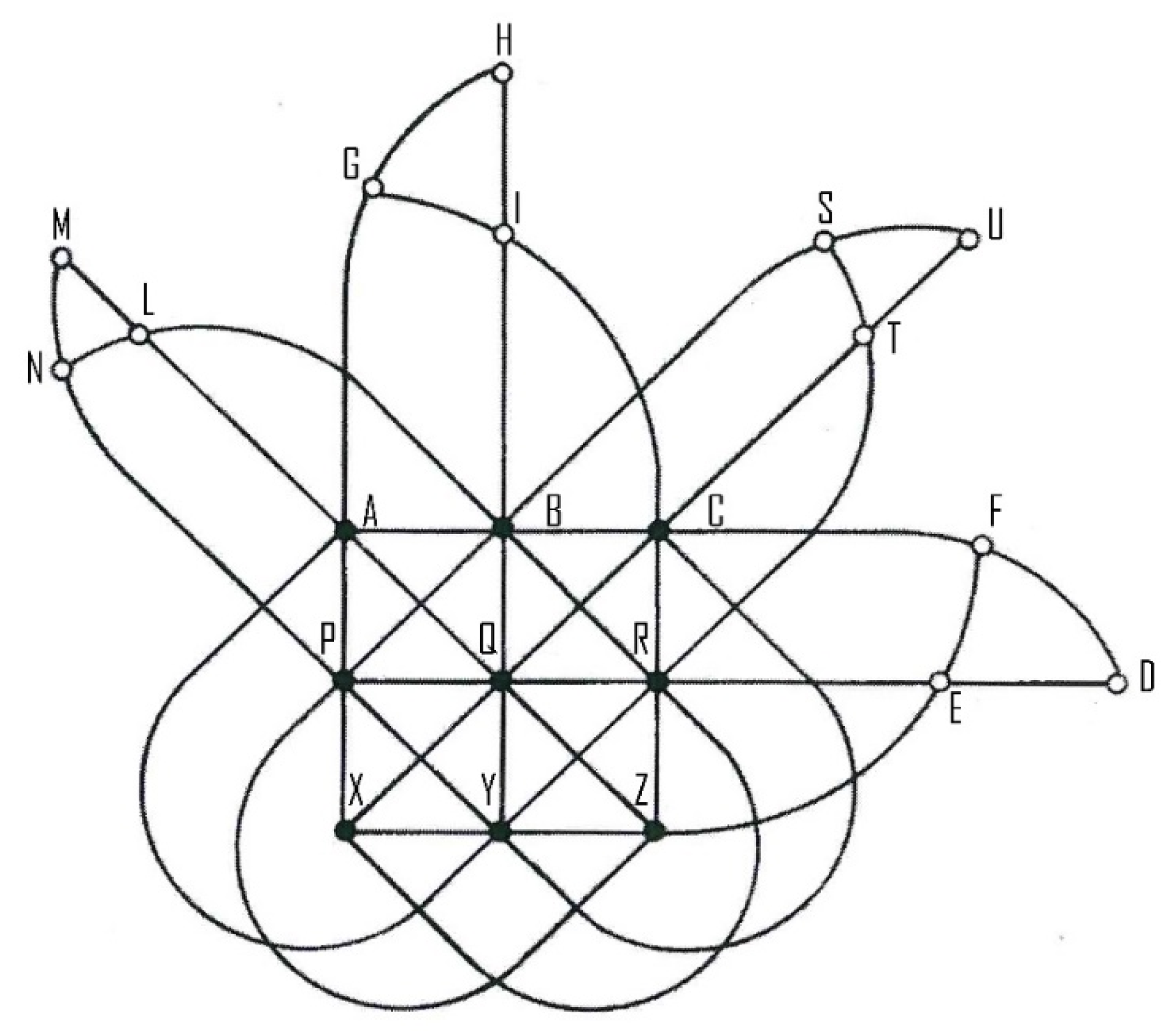

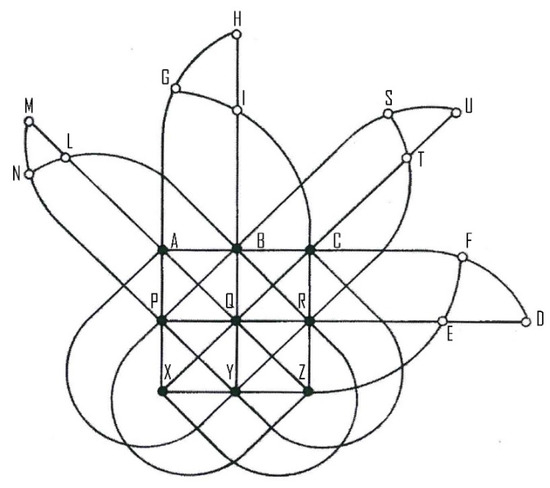

The points and their alignments are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The Hesse (94,123) configuration with the 12 intersection points of the parallel lines.

A direct check shows that these twelve points are contained, four by four, in the nine lines of the Ceva arrangement:

DGLU: x − ω2y = 0, DIMS: x − y = 0, DHNT: x − ωy = 0;

EGMT: y − ω2z = 0, EHSL: y − ωz = 0, EINU: y − z = 0;

FGNS: x − z = 0, FHMU: x − ω2z = 0, FILT: x − ωz = 0.

EGMT: y − ω2z = 0, EHSL: y − ωz = 0, EINU: y − z = 0;

FGNS: x − z = 0, FHMU: x − ω2z = 0, FILT: x − ωz = 0.

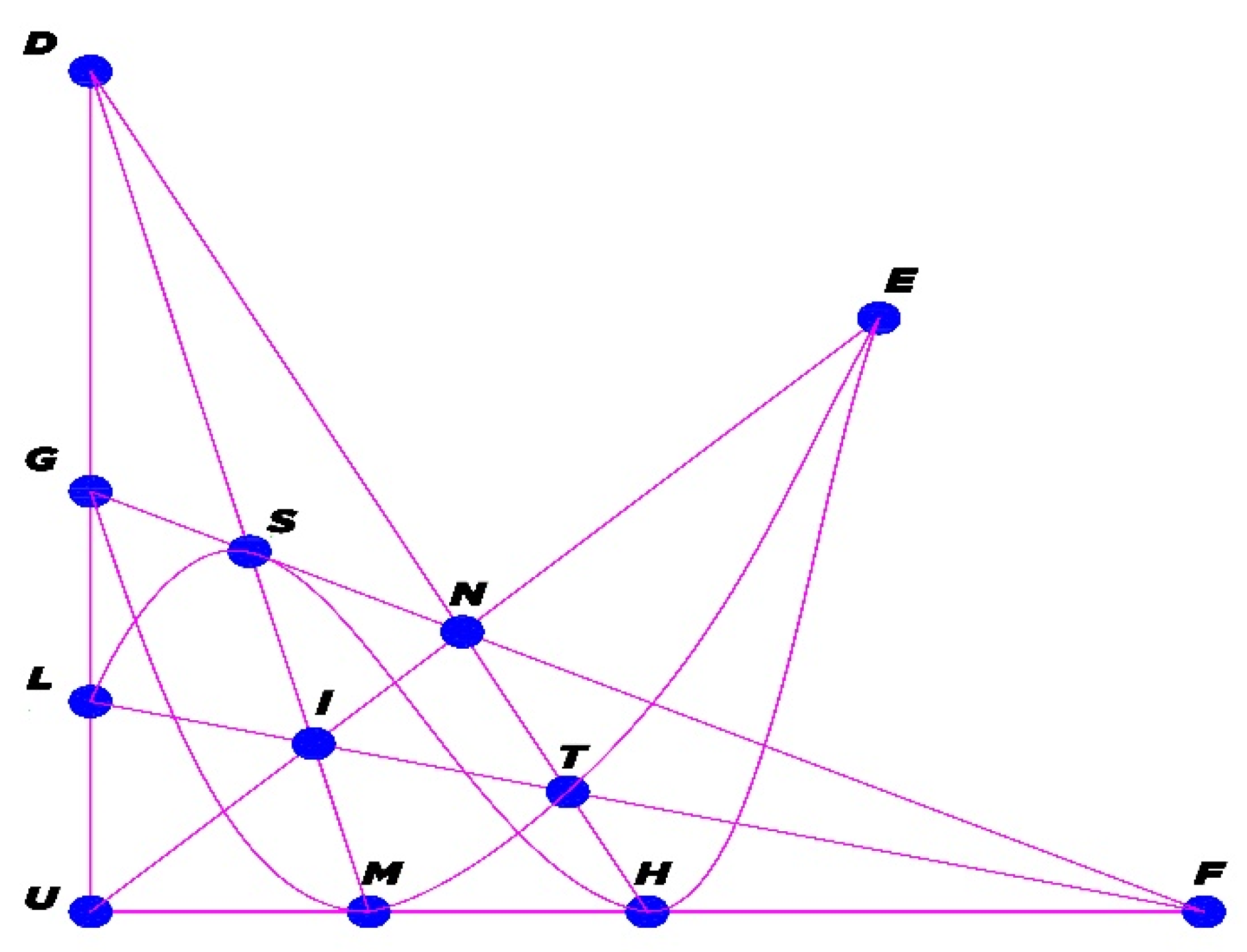

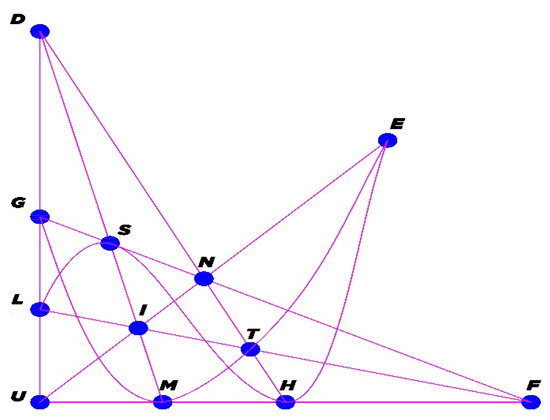

The 12 intersection points of the parallel lines and their alignments are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The 12 intersection points of the parallel lines are contained in the nine lines of the Ceva arrangement.

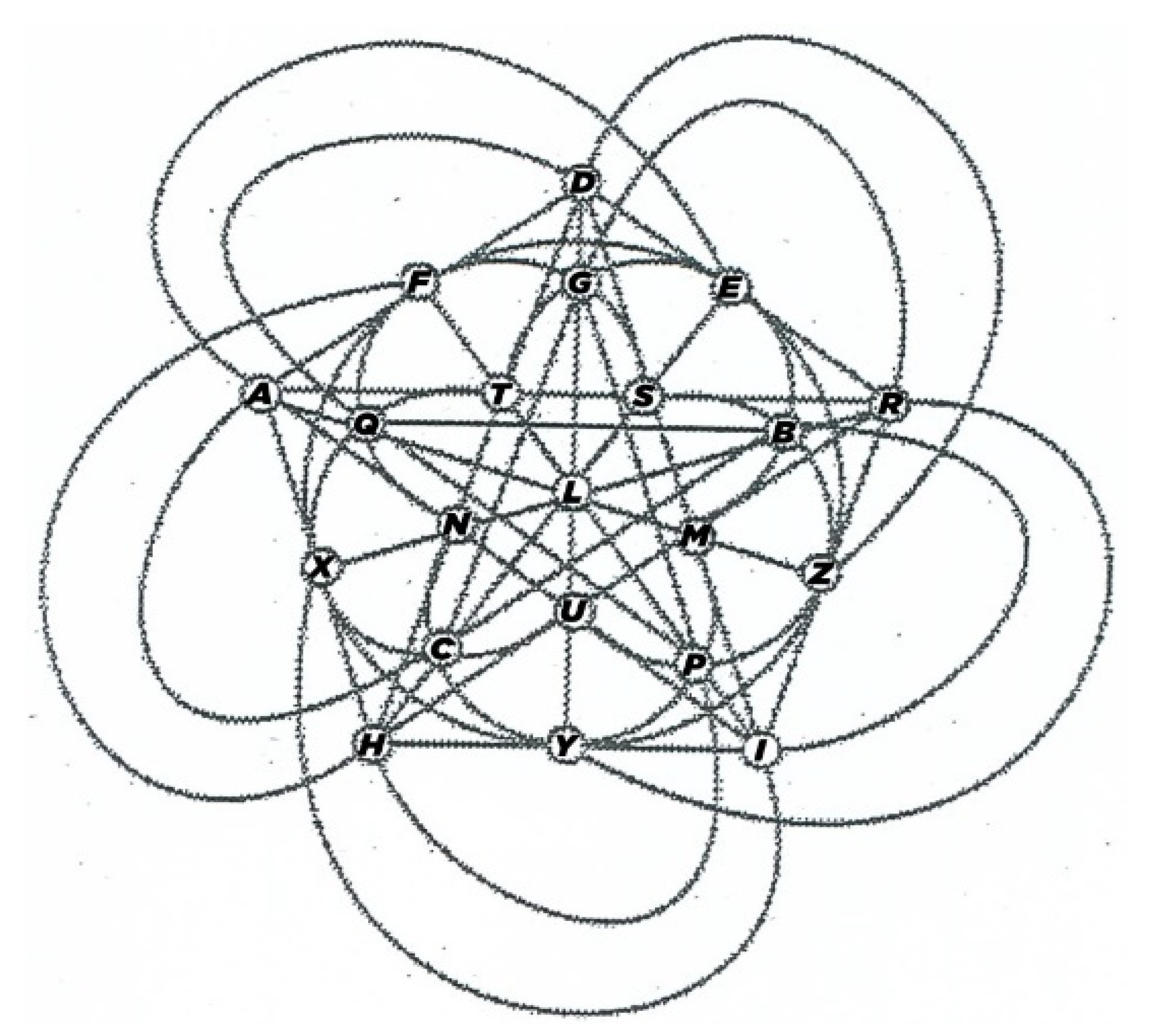

In a direct check, if the characteristic of the field 𝔽 is two, then we have that

and we get a symmetric (215) configuration, i.e., a projective plane of order four, as shown in Figure 4.

X∈DIMS, Y∈DGLU, Z∈DHNT,

A∈EINU, B∈EGMT, C∈EHSL,

P∈FILT, Q∈FGNS, R∈FHMU,

A∈EINU, B∈EGMT, C∈EHSL,

P∈FILT, Q∈FGNS, R∈FHMU,

Figure 4.

The projective plane of order four.

In a direct check, if the characteristic of the field 𝔽 is two, then the Ceva (3) configuration closes, from incidence point of view, in a projective plane of order four, and this, to our knowledge, seems to be novel.

If the characteristic of the field 𝔽 is not two, then we get either, without considering two lines, a symmetric quasi-configuration or a 21-set of type (0,1,2,4,5).

4. Klein Arrangement of Lines

The Klein arrangement of lines naturally arises from the subgroup PSL (2,7), the finite simple group of order 168, which is the automorphism group of the Klein quartic curve x3y + y3z + z3y = 0 of ℙ2, see [7,8]. It contains 21 involutions, each leaving a line fixed. The arrangement of these 21 lines is called the Klein arrangement. Let 𝔽 be a field containing a root of x2 + x + 2. The Klein arrangement consists of the 21 lines:

x = 0, y + z = 0, ωx + y − z = 0, ωx − y + z = 0, −y + z = 0, x + ωy − z = 0, ωx − y − z = 0,

−x + y + ωz = 0, ωx + y + z = 0, −x + ωy + z = 0, −x − y + ωz = 0, x + z = 0, −x + ωy − z = 0, x + ωy + z = 0,

−x + z = 0, x − y + ωz = 0, x + y + ωz = 0, z = 0, −x + y = 0, x + y = 0, y = 0.

−x + y + ωz = 0, ωx + y + z = 0, −x + ωy + z = 0, −x − y + ωz = 0, x + z = 0, −x + ωy − z = 0, x + ωy + z = 0,

−x + z = 0, x − y + ωz = 0, x + y + ωz = 0, z = 0, −x + y = 0, x + y = 0, y = 0.

Dually, we get a set of 21 points:

P1: = (1,0,0), P2: = (0,1,1), P3: = (1,ω−1,−ω−1), P4: = (1,−ω−1,ω−1), P5: = (0,1,−1), P6: = (1,ω,−1), P7: = (1,−ω−1,−ω−1),

P8: = (1,−1,−ω), P9: = (1,ω−1,ω−1), P10: = (1,−ω,−1), P11: = (1,1,−ω), P12: = (1,0,1), P13: = (1,−ω,1), P14: = (1,ω,1),

P15: = (1,0,−1), P16: = (1,−1,ω), P17: = (1,1,ω), P18: = (0,0,1), P19: = (1,−1,0), P20: = (1,1,0), P21: = (0,1,0).

P8: = (1,−1,−ω), P9: = (1,ω−1,ω−1), P10: = (1,−ω,−1), P11: = (1,1,−ω), P12: = (1,0,1), P13: = (1,−ω,1), P14: = (1,ω,1),

P15: = (1,0,−1), P16: = (1,−1,ω), P17: = (1,1,ω), P18: = (0,0,1), P19: = (1,−1,0), P20: = (1,1,0), P21: = (0,1,0).

A direct check shows either that the 21 points of the above point matrix are contained four by four in the 21 lines,

or that the 21 points of the above point matrix are contained three by three in the 28 lines,

P2P5P18P21 x = 0, P1P12P15P18 y = 0, P1P19P20P21 z = 0, P1P3P4P5 y + z = 0, P12P13P14P21 x − z = 0,

P11P17P18P20 x − y = 0, P6P10P15P21 x + z = 0, P1P2P7P9 y − z = 0, P8P16P18P19 x + y = 0,

P3P10P11P12 x − (ω + 1)y − z = 0, P4P14P15P16 x + (ω + 1)y + z = 0, P9P13P15P17 x − (ω + 1)y + z = 0,

P7P10P16P20 x − y + (ω + 1)z = 0, P2P4P6P11 (ω + 1)x − y + z = 0, P5P7P11P14 (ω + 1)x − y − z = 0,

P5P8 P9P10 (ω + 1)x + y + z = 0, P3P6P17P19 x + y + (ω + 1)z = 0, P2P3P13P16 (ω + 1)x + y − z = 0,

P6P7P8P12 x + (ω + 1)y − z = 0, P4P8P13P20 x − y − (ω + 1)z = 0, P9P11P14P19 x + y − (ω + 1)z = 0,

P11P17P18P20 x − y = 0, P6P10P15P21 x + z = 0, P1P2P7P9 y − z = 0, P8P16P18P19 x + y = 0,

P3P10P11P12 x − (ω + 1)y − z = 0, P4P14P15P16 x + (ω + 1)y + z = 0, P9P13P15P17 x − (ω + 1)y + z = 0,

P7P10P16P20 x − y + (ω + 1)z = 0, P2P4P6P11 (ω + 1)x − y + z = 0, P5P7P11P14 (ω + 1)x − y − z = 0,

P5P8 P9P10 (ω + 1)x + y + z = 0, P3P6P17P19 x + y + (ω + 1)z = 0, P2P3P13P16 (ω + 1)x + y − z = 0,

P6P7P8P12 x + (ω + 1)y − z = 0, P4P8P13P20 x − y − (ω + 1)z = 0, P9P11P14P19 x + y − (ω + 1)z = 0,

P1P6P13 y + ωz = 0, P1P10P14 y − ωz = 0, P6P14P18 ωx − y = 0, P1P8P17 ωy − z = 0, P2P8P14 (−ω + 1)x + y − z = 0,

P3P14P20 x − y + (ω − 1)z = 0, P3P8P15 x + (−ω + 1)y + z = 0, P10P13P18 ωx + y = 0, P3P9P18 x − ωy = 0,

P6P9P20 x − y + (−ω + 1)z = 0, P7P13P19 x + y + (ω − 1)z = 0, P3P7P21 x + ωz = 0, P4P7P18 x + ωy = 0, P2P15P20 x − y + z = 0,

P7P11P15 x + (ω − 1)y + z = 0, P1P11P16 ωy + z = 0, P5P11P13 (ω − 1)x + y + z = 0, P8P11P21 ωx + z = 0, P2P12P19 x + y − z = 0,

P5P15P19 x + y + z = 0, P4P9P21 x − ωz = 0, P4P10P19 x + y + (−ω + 1)z = 0, P2P10P17 (ω − 1)x + y − z = 0,

P9P12P16 x + (−ω + 1)y − z = 0, P4P12P17 x + (ω − 1)y − z = 0, P5P6P16 (ω − 1)x − y − z = 0, P5P12P20 x − y − z = 0,

P16P17P21 ωx − z = 0.

P3P14P20 x − y + (ω − 1)z = 0, P3P8P15 x + (−ω + 1)y + z = 0, P10P13P18 ωx + y = 0, P3P9P18 x − ωy = 0,

P6P9P20 x − y + (−ω + 1)z = 0, P7P13P19 x + y + (ω − 1)z = 0, P3P7P21 x + ωz = 0, P4P7P18 x + ωy = 0, P2P15P20 x − y + z = 0,

P7P11P15 x + (ω − 1)y + z = 0, P1P11P16 ωy + z = 0, P5P11P13 (ω − 1)x + y + z = 0, P8P11P21 ωx + z = 0, P2P12P19 x + y − z = 0,

P5P15P19 x + y + z = 0, P4P9P21 x − ωz = 0, P4P10P19 x + y + (−ω + 1)z = 0, P2P10P17 (ω − 1)x + y − z = 0,

P9P12P16 x + (−ω + 1)y − z = 0, P4P12P17 x + (ω − 1)y − z = 0, P5P6P16 (ω − 1)x − y − z = 0, P5P12P20 x − y − z = 0,

P16P17P21 ωx − z = 0.

Thus, we get a ((218),) quasi-configuration.

Since 7 is the smallest order, with characteristic different from 2, of a finite field, which contains a root of x2 + x + 2, such that ℙ2 contains at least 21 points, let us consider the field 𝔽7. In 𝔽7, 3 is a root of x2 + x + 2. In order to write the cyclic structure of ℙ2: = PG (2,7), let ω be a primitive element of 𝔽73 over 𝔽7 and let be its minimal polynomial over 𝔽7. The companion matrix of f is given by and it induces a Singer cycle γ of PG(2,7), cf. [9]. Let us consider a primitive polynomial with minimal weight, i.e., the minimal number of non-zero coefficients, among all primitives of that degree over 𝔽7, f(x) = x3 + 3x + 2, cf. [10]. The companion matrix C(f) is . Let us consider the point . We get:

by continuing in this way, we obtain the cyclic structure of PG (2,7) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The cyclic structure of the points of PG (2,7).

Let us denote the points represented by ωi simply by i. Thus, the Singer group is isomorphic to the additive group Z57, the integers modulo 57. The sets of 21 points are:

P1 = (1,0,0) = 0, P2 = (0,1,1) = 53, P3 = (1,5,2) = 18, P4 = (1,2,5) = 48, P5 = (0,1,6) = 37, P6 = (1,3,6) = 39,

P7 = (1,2,2) = 24, P8 = (1,6,4) = 38, P9 = (1,5,5) = 16, P10 = (1,4,6) = 50, P11 = (1,1,4) = 54, P12 = (1,0,1) = 13,

P13 = (1,4,1) = 30, P14 = (1,3,1) = 27, P15 = (1,0,6) = 43, P16 = (1,6,3) = 49, P17 = (1,1,3) = 25, P18 = (0,0,1) = 1,

P19 = (1,6,0) = 42, P20 = (1,1,0) = 35, P21 = (0,1,0) = 2,

P7 = (1,2,2) = 24, P8 = (1,6,4) = 38, P9 = (1,5,5) = 16, P10 = (1,4,6) = 50, P11 = (1,1,4) = 54, P12 = (1,0,1) = 13,

P13 = (1,4,1) = 30, P14 = (1,3,1) = 27, P15 = (1,0,6) = 43, P16 = (1,6,3) = 49, P17 = (1,1,3) = 25, P18 = (0,0,1) = 1,

P19 = (1,6,0) = 42, P20 = (1,1,0) = 35, P21 = (0,1,0) = 2,

Now, select any line, for example, we choose the line ℓ0: = x1 = 0, which contains the 8-set of points written in Table 2.

Table 2.

The starting line.

The remaining lines of the plane are found by adding 1 to each point of the preceding line beginning with ℓ0 and using addition modulo 57. For the convenience of the reader, we represent the projective plane of order 7 as a set of four orthogonal arrays of the affine plane of order 7, with the intersection point of the elements of each parallel class indicated to the right of the row array and at the bottom of the column array.

Let us color the points of the 21-set green and the others red.

{0,1,2,13,16,18,24,25,27,30,35,37,38,39,42,43,48,49,50,53,54},

{3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,14,15,17,19,20,21,22,23,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,36,40,41,44,45,46,47,51,52,55,56}.

The alignments of the Singer representation, written in Table 3, show that the Klein (,) quasi-configuration embedded in PG (2,7) is a symmetric 21-set of type (0,3,4), which are, by the result in [11], the internal points of a conic, see also [12,13,14].

Table 3.

The projective plane PG (2,7) in which the points of the 21-set are colored green and its complementary set colored red.

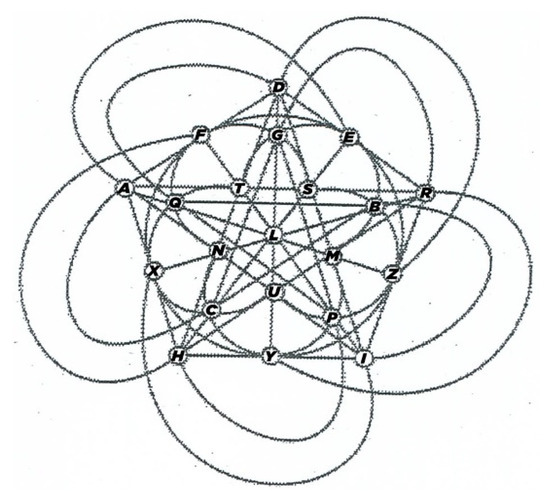

5. Wiman Arrangement of Lines

Let 𝔽 be a field containing a root of x4 – x2 + 4 and sufficiently large such that the resulting 201 points are different. The Wiman arrangement of lines consists of 45 lines of ℙ2, with 36 quintuple points, 45 quadruple points, and 120 triple points, see [3,15,16] for a detailed description of the group action giving rise to it.

Since 19 is the smallest order, with characteristic different from 2, of a finite field, such that ℙ2 contains at least 201 points, let us consider the field 𝔽19. In 𝔽19, 3 is a root of x4 − x2 + 4. The dual of the Wiman arrangement of lines consists of the 45 points, see [16]:

P1: = (0,1,0), P2: = (1,16,15), P3: = (0,0,1), P4: = (1,3,15), P5: = (1,14,6), P6: = (1,5,6), P7: = (1,9,5), P8: = (1,10,5),

P9: = (1,3,4), P10: = (1,14,13), P11: = (1,5,4), P12: = (1,12,18), P13: = (1,9,14), P14: = (1,15,2), P15: = (1,15,17),

P16: = (1,16,4), P17: = (1,5,13), P18: = (1,14,4), P19: = (1,7,18), P20: = (1,10,14), P21: = (1,4,2), P22: = (1,4,17),

P23: = (1,1,12), P24: = (1,14,15), P25: = (1,5,15), P26: = (1,12,1), P27: = (1,11,0), P28: = (1,8,8), P29: = (1,7,1),

P30: = (1,10,17), P31: = (1,18,12), P32: = (1,8,0), P33: = (1,11,8), P34: = (1,9,17), P35: = (1,0,7), P36: = (1,0,0),

P37: = (1,10,2), P38: = (0,1,11), P39: = (1,8,11), P40: = (1,11,11), P41: = (1,9,2), P42: = (0,1,8), P43: = (1,18,7),

P44: = (1,0,12), P45: = (1,1,7).

P9: = (1,3,4), P10: = (1,14,13), P11: = (1,5,4), P12: = (1,12,18), P13: = (1,9,14), P14: = (1,15,2), P15: = (1,15,17),

P16: = (1,16,4), P17: = (1,5,13), P18: = (1,14,4), P19: = (1,7,18), P20: = (1,10,14), P21: = (1,4,2), P22: = (1,4,17),

P23: = (1,1,12), P24: = (1,14,15), P25: = (1,5,15), P26: = (1,12,1), P27: = (1,11,0), P28: = (1,8,8), P29: = (1,7,1),

P30: = (1,10,17), P31: = (1,18,12), P32: = (1,8,0), P33: = (1,11,8), P34: = (1,9,17), P35: = (1,0,7), P36: = (1,0,0),

P37: = (1,10,2), P38: = (0,1,11), P39: = (1,8,11), P40: = (1,11,11), P41: = (1,9,2), P42: = (0,1,8), P43: = (1,18,7),

P44: = (1,0,12), P45: = (1,1,7).

In order to write the cyclic structure of PG (2,19), let ω be a primitive element of GF (193) over GF (19) and let be its minimal polynomial over GF (19). The companion matrix of f is given by

and it induces a Singer cycle γ of PG (2,19), cf. [9]. Let us consider a primitive polynomial with minimal weight, i.e., the minimal number of non-zero coefficients, among all primitives of that degree over GF (19), f(x) = 17 + 15x2 + x3, cf. [10]. The companion matrix C(f) is .

Let us consider the point . We get:

by continuing in this way, we obtain the cyclic structure of PG (2,19) as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The cyclic structure of the points of PG (2,19).

Let us denote the points represented by ωi simply by i. Thus, the Singer group is isomorphic to the additive group Z381, the integers modulo 381.

P1: = (0,1,0) = 1, P2: = (1,16,15) = 35, P3: = (0,0,1) = 2, P4: = (1,3,15) = 19, P5: = (1,14,6) = 266, P6: = (1,5,6) = 343,

P7: = (1,9,5) = 311, P8: = (1,10,5) = 33, P9: = (1,3,4) = 232, P10: = (1,14,13) = 207, P11: = (1,5,4) = 237,

P12: = (1,12,18) = 199, P13: = (1,9,14) = 287, P14: = (1,15,2) = 254, P15: = (1,15,17) = 325, P16: = (1,16,4) = 346,

P17: = (1,5,13) = 271, P18: = (1,14,4) = 198, P19: = (1,7,18) = 41, P20: = (1,10,14) = 256, P21: = (1,4,2) = 159,

P22: = (1,4,17) = 279, P23: = (1,1,12) = 145, P24: = (1,14,15) = 28, P25: = (1,5,15) = 40, P26: = (1,12,1) = 209,

P27: = (1,11,0) = 272, P28: = (1,8,8) = 354, P29: = (1,7,1) = 148, P30: = (1,10,17) = 350,

P31: = (1,18,12) = 278, P32: = (1,8,0) = 267, P33: = (1,11,8) = 367, P34: = (1,9,17) = 363,

P35: = (1,0,7) = 253, P36: = (1,0,0) = 0, P37: = (1,10,2) = 128, P38: = (0,1,11) = 273,

P39: = (1,8,11) = 49, P40: = (1,11,11) = 7, P41: = (1,9,2) = 95, P42: = (0,1,8) = 268,

P43: = (1,18,7) = 352, P44: = (1,0,12) = 158, P45: = (1,1,7) = 324.

P7: = (1,9,5) = 311, P8: = (1,10,5) = 33, P9: = (1,3,4) = 232, P10: = (1,14,13) = 207, P11: = (1,5,4) = 237,

P12: = (1,12,18) = 199, P13: = (1,9,14) = 287, P14: = (1,15,2) = 254, P15: = (1,15,17) = 325, P16: = (1,16,4) = 346,

P17: = (1,5,13) = 271, P18: = (1,14,4) = 198, P19: = (1,7,18) = 41, P20: = (1,10,14) = 256, P21: = (1,4,2) = 159,

P22: = (1,4,17) = 279, P23: = (1,1,12) = 145, P24: = (1,14,15) = 28, P25: = (1,5,15) = 40, P26: = (1,12,1) = 209,

P27: = (1,11,0) = 272, P28: = (1,8,8) = 354, P29: = (1,7,1) = 148, P30: = (1,10,17) = 350,

P31: = (1,18,12) = 278, P32: = (1,8,0) = 267, P33: = (1,11,8) = 367, P34: = (1,9,17) = 363,

P35: = (1,0,7) = 253, P36: = (1,0,0) = 0, P37: = (1,10,2) = 128, P38: = (0,1,11) = 273,

P39: = (1,8,11) = 49, P40: = (1,11,11) = 7, P41: = (1,9,2) = 95, P42: = (0,1,8) = 268,

P43: = (1,18,7) = 352, P44: = (1,0,12) = 158, P45: = (1,1,7) = 324.

Now, select any line as the line at infinity, for example, we choose the line ℓ∞:= x0 = 0. The remaining lines of the plane are found by adding 1 to each point of the preceding line beginning with ℓ∞ as ℓ0 and using addition modulo 381. Table 5 shows that the above 45 points are contained in 36 5-lines, 45 4-lines and 120 3-lines.

Table 5.

The cyclic structure of the lines of PG (2,19) in which the points of the 45-set are colored red.

Thus, we get a (,) quasi-configuration embedded in PG (2,19), which is a symmetric minimal blocking 45-set of type (1,3,4,5), which, to our knowledge, seems to be novel.

6. Conclusions

Sets with few intersection numbers are connected with many theoretical and applied areas, such as coding theory, strongly regular graphs, association schemes, optimal multiple coverings, and secret sharing, cf. [17]. In this paper, sets with few intersection numbers are provided by quasi-configurations derived by special arrangements of lines.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledge GNSAGA of INDAM for supporting research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bokowski, J.; Pilaud, V. Quasi-configurations: Building blocks for point-line configurations. Ars Math. Contemp. 2016, 10, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, L.W.; Gévay, G.; Pisanski, T. On a new (21_4) polycyclic configuration. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.12992v2. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, T.; Di Rocco, S.; Harbourne, B.; Huizenga, J.; Seceleanu, A.; Szemberg, T. Negative Curves on Symmetric Blowups of the Projective Plane, Resurgences, and Waldschmidt Constants. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2019, 2019, 7459–7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünbaum, B.; Rigby, J.F. The Real Configuration (214). J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1990, 2, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxeter, H.S.M. My graph. Proc. London Math. Soc. 1983, 46, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceva, G. De Lineis Rectis se Invicem Secantibus Statica Constructio, Mediolani, ex Typographia Ludouici Montiae, 1678. Available online: https://archive.org/details/ita-bnc-mag-00001346-001 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Klein, F. Uber die Transformation siebenter Ordnung der elliptischen Functionen. Math. Ann. 1879, 14, 428–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gévay, G.; Pokora, P. Klein’s arrangements of lines and conics. Beitr Algebra Geom 2023, 65, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. A theorem in finite projective geometry and some applications to number theory. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 1938, 43, 377–385. Available online: https://www.ams.org/journals/tran/1938-043-03/S0002-9947-1938-1501951-4/S0002-9947-1938-1501951-4.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Mullen, G.L. Primitive Polynomials Over Finite Fields. Math. Comput. 1992, 59, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clerck, F.; De Feyter, N. A characterization of the sets of internal and external points of a conic. Eur. J. Comb. 2007, 28, 1910–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Love, C.P. On the (22, 4)-arcs in PG(2, 7) and related codes. Discrete Math. 2003, 266, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Voorde, G. On sets without tangents and exterior sets of a conic. Discrete Math. 2011, 311, 2253–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyukliev, I.; Cheon, E.J.; Maruta, T.; Okazaki, T. On the (29, 5)-Arcs in PG(2,7) and Some Generalized Arcs in PG(2,q). Mathematics 2020, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiman, A. Zur Theorie der endlichen Gruppen von birationalen Transformationen in der Ebene. Math. Annalen 1896, 48, 195–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.; Di Rocco, S.; Harbourne, B.; Huizenga, J.; Lundman, A.; Pokora, P.; Szemberg, T. Bounded Negativity and Arrangements of Lines. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2015, 2015, 9456–9471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, N. On sets with few intersection numbers in finite projective and affine spaces. Electron. J. Combin. 2014, 21, P4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).