Abstract

The Tuzla area, located in the Ayvacık district of Çanakkale (Biga Peninsula, northwestern Türkiye), hosts a Oligocene-Miocene volcanic system comprising andesitic, dacitic, rhyolitic lavas, trachyandesite, pyroclastics, and ignimbrites, and the Kestanbol Pluton. Petrographic and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses indicate that the altered volcanic units are dominated by porphyritic dacitic/rhyodacitic and trachyandesitic rocks, with silicification, iron oxide formation, and opacification. XRD results reveal smectite, smectite–illite/mica, illite–mica, kaolinite, cristobalite–opal, K-feldspar, plagioclase, dolomite, hematite, and quartz as the principal mineral phases. Geochemical data, including rare earth elements (REEs), suggest that fractional crystallization of primary mineral phases played a major role in controlling magmatic evolution. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns display enrichment in light REEs relative to heavy REEs, indicating derivation from a common magma source. K2O–Na2O and (Na2O + K2O)–FeOᵗ–MgO (AFM) diagrams show high-K calc-alkaline, calc-alkaline, and tholeiitic affinities, with most rhyodacite/dacite and all trachyandesite samples plotting in the tholeiitic field. Tectonic discrimination diagrams indicate formation in both volcanic arc and intraplate tectonic settings. Moderate enrichments in Ba and Sr reflect magmatic evolution and source characteristics, whereas the highest concentrations are attributed to post-magmatic fluid–rock interaction. Overall, the Tuzla volcanic rocks originated from a collision-related enriched lithospheric mantle source and subsequently evolved through fractional crystallization and assimilation processes, accompanied by crustal contamination and variable hydrothermal overprint.

1. Introduction

The Biga Peninsula in northwestern Anatolia is a geologically and economically significant region due to its complex tectonic evolution, widespread magmatism, and abundant mineral and geothermal resources. The peninsula exposes a mosaic of metamorphic, ophiolitic, and Neogene sedimentary and magmatic rocks, recording multiple tectonic events from the Palaeozoic to the Quaternary. The widespread Cenozoic volcano-plutonic units are particularly important for understanding the region’s tectono-magmatic evolution, hydrothermal systems, and potential for metallic and industrial mineral deposits [1,2].

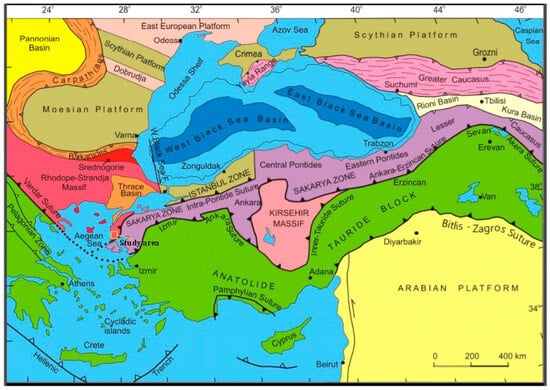

Turkey, located within the Alpine–Himalayan orogenic belt, represents one of the key geodynamic regions where volcanic and plutonic rocks are widely exposed. Northwestern Anatolia, in particular, is characterized by collisional magmatism, well-defined crust–mantle interaction signatures, and the coexistence of magmatic and tectonic processes within a structurally complex framework [3,4,5]. In terms of the regional structural framework, the east–west–trending orogenic system of Türkiye is subdivided into four main tectonic units from north to south: the Pontides, Anatolides, Taurus, and marginal fold belt, as illustrated in Figure 1 [6]. Northwestern Türkiye is bounded by the Intra-Pontide Suture Zone to the north and the İzmir–Ankara–Erzincan Suture Zone to the south and corresponds to the Pontides (or the Sakarya Zone) [7,8]. Within this tectonic setting, the Biga Peninsula represents a key exposure of the Sakarya Zone basement, comprising the Kazdağ, Karadağ, Çamlıca, and Karabiga massifs [7,9].

Figure 1.

Tectonic map of northwestern Anatolia showing the location of the study area (modified after [10]).

The Biga Peninsula records Paleogene–Neogene magmatism in three main stages—Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene—and is widely interpreted as being of post-collisional origin [8,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Subduction of the Neo-Tethyan oceanic lithosphere beneath the Sakarya Zone commenced in the Early Cretaceous (~105 Ma) and was followed by collision between the Sakarya and Tauride–Anatolide continental blocks during the Eocene [7,10,11,17]. The earliest magmatic products associated with this collision include Middle Eocene granitic plutons and andesitic volcanic rocks [11,18,19,20]. Early–Middle Miocene magmatism in the Biga Peninsula is characterized by widespread andesitic, dacitic, rhyolitic, and pyroclastic units, indicating intense and sustained volcanic activity [3,21]. Preceding magmatic phases during the Oligocene to Early Miocene produced granitic intrusions and compositionally related volcanic units [22,23,24,25]. Geochemical trends indicate a systematic evolution from medium-K calc-alkaline compositions in the Eocene, to high-K calc-alkaline affinities in the Oligocene, and ultimately to high-K alkaline and shoshonitic compositions during the Miocene. Na-rich alkaline volcanic products represent the final magmatic stage following the Early Miocene [3,4,15,16,26,27].

The present study investigates the petrographic, geochemical, and petrogenetic characteristics of the Oligocene-Miocene Tuzla volcanic rocks in the Ayvacık region. By providing new constraints on magma evolution and associated hydrothermal processes, this study aims to address existing gaps in the understanding of post-collisional volcanism within in this geodynamically complex area.

2. Geological Setting

The study area is located within the Tuzla volcanic–geothermal system near Ayvacık in the Biga Peninsula (Çanakkale, northwestern Türkiye), where Oligocene-Miocene volcanic and plutonic units are widely exposed. This region forms part of the Sakarya Zone, bounded by the Intra-Pontid Suture to the north and the İzmir–Ankara–Erzincan Suture to the south (Figure 1). The geological evolution of the area reflects prolonged tectonic processes, including continental collisions, oceanic basin closure, magmatic arc development, and post-collisional extension since the Paleozoic [28,29,30]. The basement of the peninsula is represented by the amphibolite-facies Kazdağ Kazdağ Group, which comprises, from bottom to top, the Fındıklı, Tozlu, Sarıkız, and Sutüven formations [29]. These metamorphic units are unconformably overlain by Paleozoic recrystallized limestones, which are, in turn, covered by Miocene rhyolitic tuffs and agglomerates. Tectonically overlying the basement are the Permo–Triassic Karakaya Complex—composed of partially metamorphosed and strongly deformed clastic and volcanic rocks belonging to the Nilüfer, Hodul, Orhanlar, and Çal units—and the Cretaceous Çetmi ophiolitic mélange [9]. To the north of the Sakarya Zone, the Ezine Zone is exposed and comprises the Ezine Group, the Çamlıca metamorphics, and the tectonically emplaced Denizgören Ophiolite. This zone is separated from the Sakarya Zone by the Çetmi Mélange. The Çamlıca metamorphics contain high-pressure/low-temperature eclogitic relics, indicating Maastrichtian metamorphism (65–69 Ma) [31]. The Ezine Group consists mainly of Permo–Triassic carbonates and epicontinental sedimentary rocks metamorphosed under greenschist-facies conditions [32]. The Çetmi Mélange, composed of spilite, greywacke, shale, serpentinite, and radiolarite, represents an ophiolitic unit emplaced during the Late Cretaceous and transported southward during the Paleocene collision [33,34]. The Denizgören ophiolite, consisting predominantly of partially serpentinized harzburgites, tectonically overlies both the Çamlıca metamorphics and Ezine Group [9].

Eocene magmatism in the region is represented by granitic plutons and their volcanic equivalents [14,35]. During the Early Miocene, post-collisional magmatic activity produced high-K calc-alkaline to shoshonitic, I-type plutonic rocks (e.g., the Kestanbol Pluton: 21.5 ± 1.6 Ma [36]; 22.3 ± 0.2 Ma and 22.8 ± 0.2 Ma [35]) as well as coeval calc-alkaline to shoshonitic volcanic units [3,36,37,38]. This magmatic episode is widely interpreted as a consequence of post-collisional continental extension [3,38,39,40]. Miocene magmatic units in the study area include the Tuzla Volcanics and the quartz monzonite–monzogranite Kestanbol Pluton [23]. Volcanic activity commenced with the eruption of rhyolitic tuffs and agglomerates, followed by trachytic–trachyandesitic lava flows, and culminated in extensive rhyolitic tuff and ignimbrite deposition [2]. 40Ar-39Ar ages obtained of biotite (21.22 ± 0.09 Ma) and leucite (22.21 ± 0.07 Ma) crystals indicate that tephriphonolite dyke emplacement was coeval with the intrusion of the Kestanbol Pluton during the Early Miocene (21.5 ± 1.6, 22.8 ± 0.2 Ma) [41].

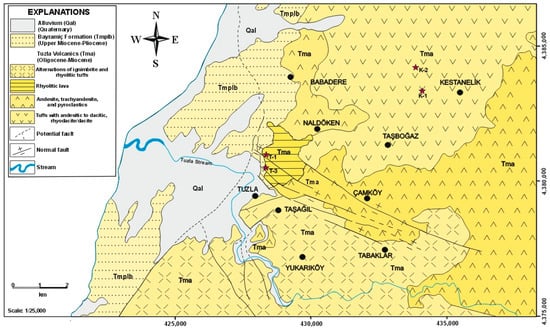

The Tuzla Volcanics, representing the most widespread volcanic unit of the Oligocene-Miocene, consist predominantly of hydrothermally altered porphyritic andesites, basaltic–andesitic lavas, and associated pyroclastic deposits. These units are exposed around Babadere, Naldöken, Taşboğaz, Çamköy and Kestanelik (Figure 2) and are intruded at depth by the Kestanbol Pluton. The volcanic succession is subdivided into three principal units: (i) Oligocene-Early Miocene felsic lava flows (rhyolite–dacite), characterized by massive, hard, and brittle flows locally associated with flow breccias. These rocks display colors ranging from grey to greenish and reddish-brown, and well-developed joint and fracture systems are common. (ii) Lava–pyroclastic alternations composed of well-bedded pumice and crystal tuffs, volcanic blocks, and bombs. These units are commonly affected by hydrothermal alteration, resulting in yellow, light brown, or cream-colored hues (Figure 3a–c). (iii) Later-stage andesitic–trachyandesitic lava flows, locally intercalated with flow breccias, lahar deposits, and lacustrine sandstones [38].

Figure 2.

Geological map of the study area showing sample locations and sample codes (modified after [37,38,42]).

Figure 3.

Field views of the volcanics. (a) Rhyodacitic–dacitic outcrop at Kestanelik, showing alteration zones and local yellow–brown surface oxidation, with a representative hand specimen. (b) Tuzla outcrop, displaying intense alteration, fractures, and widespread yellow discoloration, with a hand specimen showing strong surface oxidation. (c) Tuzla outcrop, with well-developed layering and widespread yellow–brown oxidation, together with a hand specimen illustrating pronounced surface alteration.

K-Ar dating of rhyolitic tuffs yields an age 26.5 ± 1.1 Ma (Late Oligocene) [30], whereas andesitic and trachyandesitic units were dated at 21.2 ± 0.9 Ma using the K–Ar method and 22.72 ± 0.19 Ma and 22.97 ± 0.23 Ma based on SHRIMP U–Pb zircon analysis [15]. Volcanic activity was largely controlled by NE–SW to NW–SE trending fault zones, which also governed in localized subsidence and episodic lacustrine sedimentation.

The Late Miocene volcanic succession exposed south of the Kestanbol Pluton constitutes the most extensive ignimbrite sequence in the region. These ignimbrites are exposed north of the Tuzla and Kestanelik and are predominantly pyroclastic in origin. According to [38], the ignimbrite succession displays a tripartite architecture comprising a basal surge unit, a welded ignimbrite, and an overlying unwelded pumice-rich tuff. Columnar jointing is common in the upper levels, whereas progressive welding in the lower to middle parts produces distinct petrographic zonation. The lower part of the succession begins with latite and andesite lava flows, which are intruded by basaltic and andesitic dykes. The most widespread ignimbrite unit attains a thickness of approximately 40–45 m and contains intermediate volcanic lithic fragments as well as granitic clasts. The upper part of the succession consists of alternating ignimbrite and andesite layers, forming the most extensive pyroclastic sequence in the area. Locally, late-stage rhyolite domes (Tuzla and Ortatepe) developed with compositions similar to those of the Ayvacık volcanics. U–Pb zircon ages obtained from the ignimbrites cluster around the Early Miocene age of ~22.3 ± 1.2 Ma [38].

The ignimbrite succession represents the late stage of regional volcanism and comprises Middle–Late Miocene ignimbrites, pumice-rich ignimbrites, tuffs, and agglomerates exposed around Taşağıl, Tabaklar, and Yukarıköy (Figure 2). The youngest volcanic products in the area are Late Miocene alkaline basalts. All volcanic and plutonic units are unconformably overlain by the Upper Miocene–Pliocene Bayramiç Formation, which consists composed of continental conglomerates, mudstones, marls, and lacustrine limestones [29,43].

3. Materials and Methods

This study is based on volcanic samples collected from the field, including six samples (K-1, K-2 code) from the Kestanelik area and eight samples (T-1, T-3 code) from the Tuzla area. An integrated approach was applied to comprehensively characterize the studied rocks. Mineralogical and petrographic characteristics were investigated using standard thin section petrography and X-ray diffraction (XRD; n = 9). Major and trace element geochemical compositions were determined for all 14 samples. The combined results of these analyses were used to constrain magma source characteristics, fractional crystallization and assimilation processes, and the tectonic setting of the volcanic rocks.

3.1. Mineralogical–Petrographic Analysis

Fourteen representative thin sections were prepared from volcanic rock samples. The samples, cut to dimensions of 5 × 5 × 5 cm, were processed at the Mineralogy–Petrography Laboratory of the Department of Mineral Analyses and Technology, General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (MTA). Petrographic examinations were conducted using a Leica BX–51 polarizing microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at magnifications of 4 × 10 and 10 × 10 in the “Water–Rock and Mineral Analysis Laboratory” of the Department of Geological Engineering, Süleyman Demirel University (SDU). Petrographic observations focused on rock classification, textural characteristics, and mineral assemblages. Photomicrographs were acquired using a 5.1-megapixel digital camera (Lumenera Corporation, Ottawa, ON, Canada) mounted on the microscope.

Nine powder samples were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) at the Mineralogy-Petrography Unit of the Department of Mineral Analysis and Technology, General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (MTA). The analyses were performed using a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with CuKα radiation and a Ni filter. Clay mineral assemblages were examined in detail using XRD patterns obtained under scanning conditions (2–70° 2θ), as well as oriented mounts analyzed under air-dried (2–30° 2θ), ethylene glycol–treated (2–30° 2θ), and heat-treated conditions.

3.2. Geochemical Analysis

Nine representative rock samples were pulverized to <200 mesh at Activation Laboratories Ltd. (Actlabs, Canada) for whole-rock chemical analysis. Major oxides and trace elements concentrations were determined using inductively coupled plasma–emission spectrometry (ICP-ES). For rare earth element (REE) analyses, the samples were digested in dilute nitric acid and subsequently fused with a lithium metaborate/tetraborate flux to ensure complete dissolution. The resulting solutions were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

4. Results

4.1. Petrographic Characteristics

4.1.1. Optical Microscopy

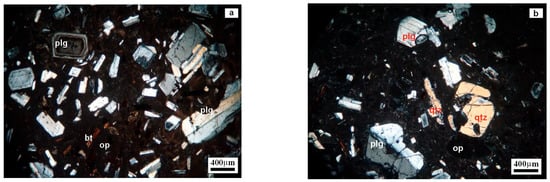

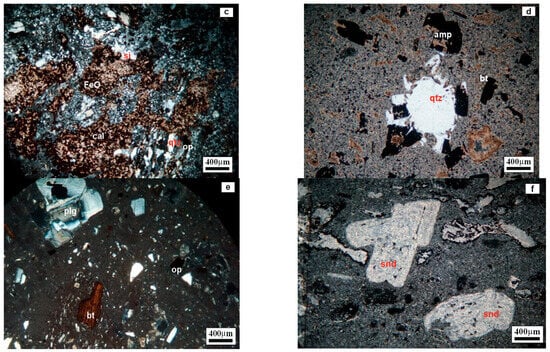

A total of 14 thin sections were prepared from the volcanic rocks collected in the study area. Petrographic analyses were performed under plane-polarized and cross-polarized light using a polarizing microscope, and representative photomicrographs were obtained. The principal phenocryst phases in the rhyodacite/dacite and andesite/trachyandesite samples are plagioclase, quartz, and biotite, accompanied by subordinate amphibole and opaque minerals (Figure 4). In the rhyodacite/dacite thin sections (Figure 4a,b,d,e), plagioclase crystals commonly exhibit polysynthetic twinning and zoning, whereas biotite shows pronounced opacification (Figure 4a). Figure 4b displays subhedral plagioclase with well-developed twinning, euhedral to subhedral quartz, and opaque minerals, together with hexagonal microcrystalline quartz and minor relict feldspar grains. The groundmass is predominantly glassy and exhibits intense staining related to Fe–Ti oxide–bearing phases associated with plagioclase, quartz, and biotite. Silicification and opacification are also widely observed (Figure 4c). Microcrystalline quartz and quartz veins of variable thickness and orientation occur as products of silica-rich fluids. The introduction of calcium together with silica locally resulted in calcite formation. Iron-rich zones display strong iron oxide enrichment and pervasive opacification, with euhedral opaque minerals occurring both within these zones and along quartz veins (Figure 4c). Microcrystalline quartz and quartz veins of variable thicknesses and orientations occur within silica-rich solutions. The introduction of calcium alongside silica led to the formation of calcite. Iron-rich areas exhibit intense iron oxide enrichment and widespread opacification, with euhedral opaque minerals present both in iron-rich zones and within the quartz veins (Figure 4c). In Figure 4d, anhedral quartz, amphibole, and biotite crystals are observed, whereas Figure 4e shows biotite flakes with a spherulitic texture. These spherulitic domains may represent early-formed components that were subsequently remobilized and reintroduced into the magma. Figure 4f illustrates sanidine crystals within trachyandesite/andesite displaying a vesicular texture, where some crystals are well preserved while others show varying degrees of alteration.

Figure 4.

Polarizing microscope images of Tuzla volcanics. (a) Porphyritic rhyodacitic/dacitic rock with euhedral–subhedral plagioclase (plg) phenocrysts in a fine-grained groundmass, with biotite (bt) and opaque minerals (op). (b) Porphyritic rhyodacitic/dacitic rock with plagioclase (plg) and quartz (qtz) phenocrysts; quartz (qtz) locally fractured, with opaque minerals (op). (c) Trachyandesitic rock showing silicification (si) and calcite (cal) with local FeO enrichment, with quartz (qtz) and opaque minerals (op). (d) Rhyodacitic/dacitic rock with amphibole (amp) and biotite (bt) associated with a quartz (qtz) phenocryst, locally embayed margins. (e) Porphyritic rhyodacitic/dacitic rock with plagioclase (plg) phenocrysts and biotite (bt) with brown pleochroism, with scattered opaque minerals (op). (f) Trachyandesitic rock with sanidine (snd) phenocrysts, semi-euhedral to anhedral, in a dark, fine-grained to microlitic matrix. Abbreviations: plagioclase (plg), quartz (qtz), biotite (bt), sanidine (snd), amphibole (amp), opaque (op), calcite (cal), silicification (si), iron oxidation (FeO).

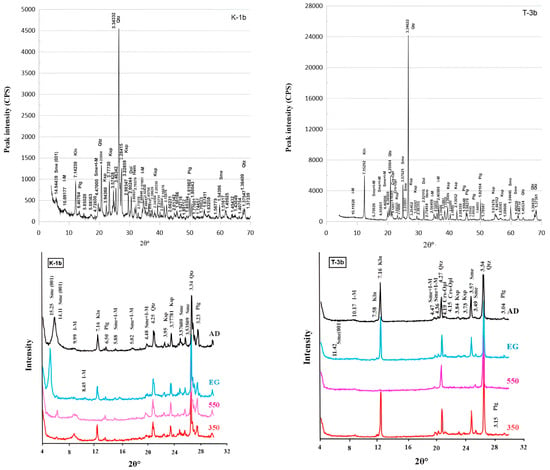

4.1.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses of volcanic rock samples collected from surface units in the Tuzla field reveal well-defined clay mineral assemblages. Representative diffraction patterns and corresponding analytical results are shown in Figure 5. The samples are dominated by smectite, smectite–illite/mica interstratifications, illite/mica, and kaolinite. Analysis of the clay fraction indicates that illite exhibits basal reflections with d(001) spacings ranging from 9.95 to 10.33 Å, d(002) spacings from 4.36 to 5.70 Å, and d(003) spacings from 2.45 to 2.58 Å. Smectite displays a wider range of basal spacings, with d(001) values between 11.16 and 14.94 Å, d(002) values from 3.47 to 3.57 Å, and d(003) values from 1.49 to 1.54 Å. Air-dried (AD), ethylene glycol–treated (EG), and heat-treated preparations at 350 and 550 °C show that the 001 and 002 reflections of smectite remain largely stable, whereas the 003 reflection disappears following these treatments. In long-scan analyses of samples in which smectite is not readily apparent, the characteristic smectite d(001) peak becomes evident after AD and EG treatments, confirming the presence of minor or poorly crystallized smectite layers. In some samples, EG treatment results in smectite expansion up to 21.77 Å, indicating well-developed swelling behavior. Heating at 350 and 550 °C leads to a progressive decrease in the d(001) spacing, consistent with the structural collapse of smectite layers.

Figure 5.

Mineralogical composition and relative abundances of minerals in the volcanic rock samples collected from the Tuzla field, determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The figure presents bulk-rock and clay-fraction diffractograms for each sample (AD: air-dried; EG: ethylene–glycol–solvated; 350 °C and 550 °C: heated preparations). Abbreviations: Smectite (Sme), illite-mica (I-M) smectite+illite-mica (Sme+I-M), kaolinite (Kln), cristobalite (Ksp), plagioclase (Plg), dolomite (Dol), hematite (Hem), and quartz (Qtz).

4.2. Geochemistry

Fourteen volcanic rock samples collected from surface exposures in the Tuzla field were analyzed for major oxides, trace elements, and rare earth elements (REEs). The analytical results are summarized in Table 1. The rhyodacite/dacite samples show SiO2 contents ranging from 51.80 to 73.36 wt.%, Al2O3 from 10.32 to 17.68 wt.%, Fe2O3 from 0.76 to 9.47 wt.%, MgO from 0.02 to 2.26 wt.%, CaO from 0.07 to 11.15 wt.%, K2O from 0.81 to 7.05 wt.%, and Na2O from 0.06 to 2.05 wt.%. These major-element compositions indicate pronounced differentiation and a wide range of compositional variability. The systematic decrease in MgO and CaO with increasing SiO2 reflects progressive magmatic evolution, primarily controlled by fractional crystallization of mafic minerals and plagioclase. Locally elevated Fe2O3 contents, reaching up to 9.47 wt.% in some samples, suggest variable redox conditions and secondary enrichment related to hydrothermal alteration. The trachyandesite samples are characterized by SiO2 contents between 58.23 and 76.53 wt.%, Al2O3 ranging from 12.63 to 17.89 wt.%, and Fe2O3 contents from 1.23 to 6.53 wt.%. Alkali contents vary between 0.13 and 4.35 wt.% for K2O and between 0.10 and 1.58 wt.% for Na2O, whereas the remaining major oxides generally occur at concentrations below 1 wt.%. Sample K-2c, collected from a locality marked by pronounced iron-oxide enrichment, exhibits a relatively high Fe2O3 content, reflecting localized oxidation processes. The upper range of SiO2 values in the trachyandesite samples overlaps with that of the rhyodacite/dacite group, indicating transitional compositions and/or advanced stages of magmatic differentiation. Overall, the volcanic rocks of the Tuzla field display a broad range of silica contents, varying from 51.80 to 76.53 wt.% SiO2, with an average value of 67.80 wt.%. Their relatively high SiO2 and Al2O3 contents, together with generally low concentrations of other major oxides (typically < 1 wt.%), indicate that these rocks represent silica-rich and highly evolved volcanic products. Variations in K2O and Na2O contents reflect differential behavior of alkali elements during magma evolution and post-magmatic processes. In particular, low Na2O values in some samples are likely attributable to plagioclase fractionation and/or sodium loss during hydrothermal alteration, whereas locally elevated K2O contents suggest potassic enrichment related to crustal input or fluid–rock interaction. The geochemical characteristics of sample K-2c further highlight the influence of localized oxidation and hydrothermal processes within the Tuzla field.

Table 1.

Major oxide (wt.%), trace and rare earth elements (ppm) concentrations of Tuzla volcanic rocks samples (Key notes: DL, detection limit; LOI, lost on ignition).

Trace-element data indicate that Sr concentrations range from 20 to 5320 ppm in the rhyodacite/dacite samples and from 306 to 1042 ppm in the trachyandesites, whereas Ba contents vary from 233 to 1287 ppm in the rhyodacite/dacite samples and from 264 to 20,050 ppm in the trachyandesites (Table 1). Moderate Sr concentrations may reflect limited plagioclase fractionation and/or local plagioclase accumulation during magma evolution, whereas lower Sr values are consistent with Sr depletion resulting from plagioclase removal during advanced stages of magmatic differentiation. In contrast, the extremely high Ba contents—particularly values reaching up to 20,050 ppm in some trachyandesite samples—cannot be satisfactorily explained by primary magmatic processes alone (Table 1). Such anomalously high Ba concentrations strongly suggest the involvement of secondary processes, most likely related to hydrothermal alteration and the precipitation of Ba-bearing minerals, such as barite, within fractures, veins, or pore spaces. Similar secondary Ba enrichment has been widely documented in geothermal and hydrothermal systems, where circulating fluids mobilize and redeposit large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs).

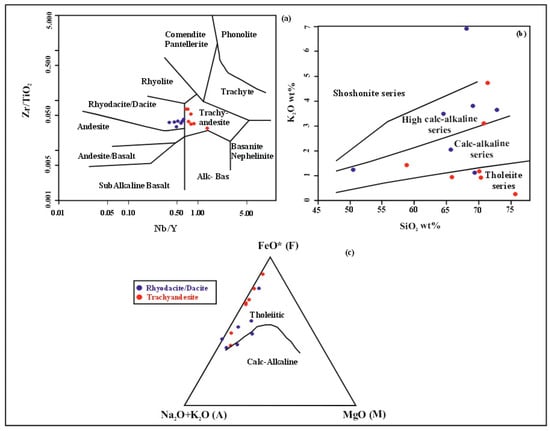

In the Zr/TiO2–Nb/Y discrimination diagram of [44], which employs major and selected trace-element concentrations for volcanic rock classification, the studied samples plot predominantly within the rhyodacite/dacite and trachyandesite fields (Figure 6a). According to the K2O–SiO2 diagram of [45], the rhyodacite/dacite samples are mainly distributed within the calc-alkaline field, whereas most of the trachyandesite samples fall within the tholeiitic field (Figure 6b). In the AFM ternary diagram of [46], the majority of the rhyodacite/dacite samples plot within the tholeiitic field, with only two samples extending into the calc-alkaline field, while all trachyandesite samples are restricted to the tholeiitic domain (Figure 6c). Overall, these geochemical classifications indicate that the magmatic evolution of the Tuzla volcanic rocks reflects a complex differentiation history involving both tholeiitic and calc-alkaline evolutionary trends.

Figure 6.

(a) Rock classification graph of volcanics [44]. (b) K2O-Si2O [45] diagrams, (c) AFM (FeO*-Na2O + K2O-MgO) diagram showing the boundary between tholeiitic and calcaline series [46].

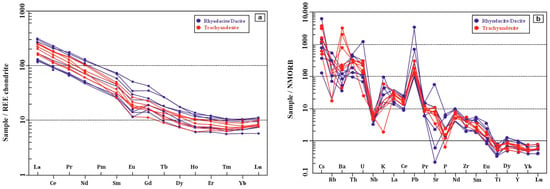

Chondrite-normalized rare earth element (REE) spider diagrams of the studied volcanic rocks [47] are shown in Figure 7. The rhyodacite/dacite and trachyandesite samples exhibit pronounced enrichment in light rare earth elements (LREEs) relative to heavy rare earth elements (HREEs), with LaN/SmN ratios ranging from 3.93 to 9.28 and LaN/YbN ratios between 16.38 and 34.50. These values indicate broadly similar REE distribution patterns among the investigated rock types (Figure 7a). Such LREE enrichment relative to HREEs is a typical geochemical characteristic of calc-alkaline volcanic suites [48,49].

Figure 7.

(a) Chondrite-normalized rare earth element (REE) patterns [47]. (b) N-MORB–normalized trace element distribution patterns of the volcanic rocks from the study area [47].

The observed REE patterns indicate that the studied volcanic rocks evolved through differentiation of parental magma(s) derived from a common source. The volcanic rocks display slight negative Eu anomalies superimposed on LREE-enriched patterns (Figure 7a). The average Eu/Eu* values range from 0.57 to 0.91 for the rhyodacite/dacite samples and from 0.62 to 0.85 for the trachyandesites. These negative Eu anomalies are interpreted to result from plagioclase fractionation and may also reflect assimilation of Eu-depleted continental crustal material.

The studied volcanic rocks show enrichment in light rare earth elements (LREEs) relative to heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) in N-MORB–normalized trace element patterns (Figure 7b). They are characterized by enrichment in large ion lithophile elements (LILEs), such as K, Pb, and Th, together with depletion in Rb and Sr. High field strength elements (HFSEs), including Nb, Zr, Ti, P, and Yb, are also depleted. In addition, Ba displays both positive and negative anomalies (Figure 7b).

5. Discussion

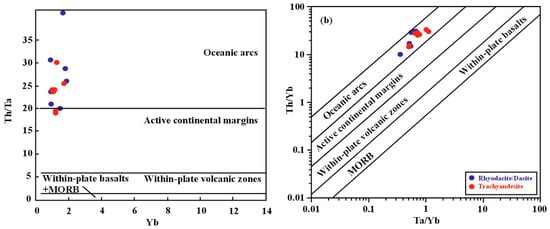

5.1. Tectonic Setting

To constrain the tectonic setting of the Tuzla volcanics, several widely used geochemical discrimination diagrams were applied [50,51]. In the Th/Ta versus Yb diagram, most samples plot within the oceanic arc field, while a limited number extend toward the active continental margin domain (Figure 8a). Likewise, the Th/Yb versus La/Th diagram places all samples within the oceanic arc field (Figure 8b). For comparison, Oligocene–Miocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the Büyükbostancı–Çiçekpınar villages (Balıkesir, NW Turkey) plot within the active continental margin field in the Th/Ta versus Yb diagram, reflecting a different tectonomagmatic setting [52]. Ref. [53] showed that the Gökçeada volcanic rocks fall within the oceanic arc field on the same diagram and display a vertically elongated distribution indicative of subduction-related enrichment, a pattern closely comparable to that observed in the Tuzla volcanics. Overall, these geochemical signatures indicate that the Tuzla volcanic rocks were predominantly generated in an oceanic arc–related tectonic setting, with a subordinate contribution from active continental margin processes. This interpretation is consistent with other Oligocene–Miocene magmatic suites in NW Türkiye and with comparable subduction-related volcanic sequences documented in comparable tectonic settings worldwide.

Figure 8.

Geochemical discrimination diagrams for the Tuzla volcanic rocks: (a) Th/Ta versus Yb diagram [50]; (b) Ta/Yb versus Th/Yb diagram (after [51]).

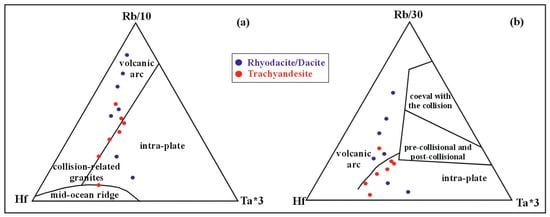

The Tuzla volcanic rocks display mixed geochemical affinities, as they are distributed across both the volcanic arc and intraplate fields in the Rb/10–Hf–Ta*3 and Rb/30–Hf–Ta*3 triangular diagrams (Figure 9a,b) [54]. The rhyodacite/dacite samples predominantly plot within the volcanic arc field, whereas the trachyandesites mainly fall within the intraplate field, indicating contributions from both arc-related and intraplate magmatic processes. For comparison, the Yürekli volcanic rocks, which are spatially adjacent to the Tuzla volcanics, are mainly composed of andesite–trachyandesite–dacite, with minor basaltic andesite. In the Rb/10–Hf–Ta*3 diagram, these samples plot largely within the volcanic arc field, whereas in the Rb/30–Hf–Ta*3 diagram they are distributed between the pre-collisional and post-collisional fields, with only a few samples plotting in the volcanic arc field [55]. This comparison highlights the differences in magmatic evolution and source contributions between the Tuzla and Yürekli volcanic suites.

Figure 9.

Distribution of rhyodacite/dacite and trachyandesite samples from the Tuzla volcanic rocks in (a) the Rb/10–Hf–Ta*3 diagram and (b) the Rb/30–Hf–Ta*3 diagram [54].

In particular, because Rb is a large-ion lithophile element that is highly mobile and sensitive to hydrothermal fluids, the distributions observed in these discrimination diagrams may reflect not only primary magmatic signatures but also the effects of hydrothermal alteration and fluid–rock interactions. The dispersion of samples across both the volcanic arc and intraplate fields in the Rb/10–Hf–Ta*3 diagram suggests a multi-source magmatic system; however, it also implies that the positions of some samples may have been secondarily modified by Rb enrichment or depletion. In this context, the overlap between the arc and intraplate fields observed in the Rb/10–Hf–Ta*3 diagram can be partly attributed to the influence of alteration on Rb distribution. By contrast, the clearer separation observed between rock types in the Rb/30–Hf–Ta*3 diagram indicates that this diagram more effectively preserves the primary magmatic signal, as it is less sensitive to Rb mobility. The predominance of rhyodacite/dacite samples within the volcanic arc field suggests that their characteristic geochemical signatures—reflecting contributions from subduction-related metasomatized mantle sources and crustal components—have been largely retained despite hydrothermal overprinting. Conversely, the concentration of trachyandesite samples within the intraplate field implies derivation from enriched lithospheric mantle sources and indicates a post-arc/intraplate magmatic affinity.

5.2. Magma Source

The studied volcanic rocks are characterized by pronounced enrichment in large ion lithophile elements (LILEs; Rb, Ba, and K) and light rare earth elements (LREEs) relative to high field strength elements (HFSEs; Nb, Ti, Zr, Hf, and Y) and heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) (Figure 8b). This geochemical signature indicates a metasomatized mantle source enriched in LILEs by a subduction-related component. [55]. The presence of negative Nb, P, Zr, and Ti anomalies, together with LREE enrichment relative to HREEs, further supports a subduction-related continental arc affinity for the parental magmas [51,56,57,58,59]. Elevated Th/Yb ratios, coupled with enrichment in Ce, Th, and other LILE elements (Sr, K, Ba, Rb), suggest that the parental magmas were derived predominantly from the lithospheric mantle [60,61,62,63,64]. Moreover, the marked depletion of Nb relative to LILEs implies that the mantle source region was metasomatized by fluids and/or melts released from the subducting slab or associated sediments, reinforcing a subduction-modified mantle origin for the magmas [51,61,65]. Comparable trace element characteristics have also been reported for volcanic rocks from the Ezine–Gülpınar–Ayvacık region in western Anatolia, Türkiye [3], indicating similar magmatic processes and tectonomagmatic settings.

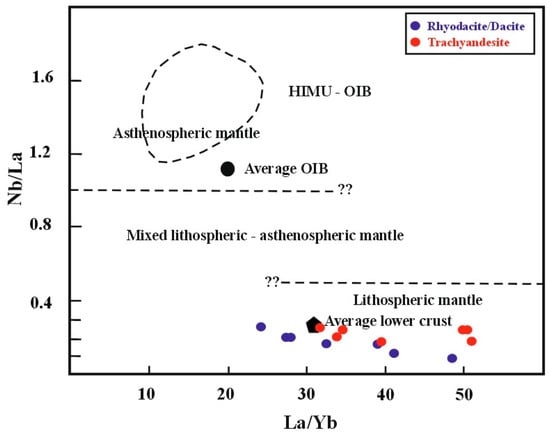

High-field strength elements (HFSEs), such as Nb, are commonly depleted relative to light rare earth elements (LREEs; e.g., La) in the lithospheric mantle. Consequently, high Nb/La ratios (>1) are generally interpreted to indicate an asthenospheric mantle source, whereas low Nb/La ratios (<0.5) are characteristic of a lithospheric mantle origin [66,67]. In the investigated rhyodacite/dacite samples, Nb/La ratios range from 0.11 to 0.25, while La/Yb ratios vary between 24.30 and 48.45. The trachyandesite samples yield Nb/La ratios of 0.19–0.25 and La/Yb ratios of 32.83–51.17. The combination of low Nb/La and high La/Yb ratios indicates that the parental magmas were predominantly derived from a lithospheric mantle source (Figure 10). For comparison, Lower Miocene Şapçı volcanic rocks, which exhibit geochemical characteristics similar to those of the Tuzla volcanics [68], plot within the same field on the Nb/La versus La/Yb diagram. In contrast, Mesozoic volcanic rocks from central Lebanon (Middle East) fall within the HIMU–OIB field on the same diagram [69], reflecting a significant contribution from an asthenospheric mantle source

Figure 10.

Nb/La versus La/Yb diagram. Mean OIB values are from [66], and mean lower crust values are from [67]. Dashed lines separating asthenospheric, lithospheric, and mixed mantle domains are based on [67]. The HIMU–OIB field is defined using data from the oceanic islands of St. Helena, Bouvet, and Ascension as reported by [70], assuming Yb = Tb ÷ 0.5. (OIB: Ocean Island Basalt; HIMU–OIB: asthenospheric mantle source characterized by high μ (U/Pb) ratios).

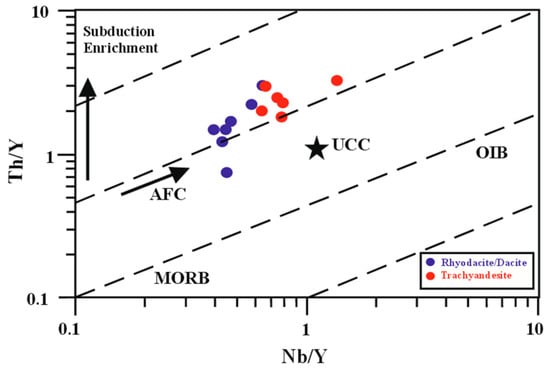

The Nb/Y and Th/Y ratios are widely used geochemical parameters for distinguishing between crustal contamination and homogenization of magma sources. The Nb/Y versus Th/Y discrimination diagram [51] (Figure 11) is commonly applied to differentiate between subduction-enriched and melt-enriched magmatic systems. In the present study, the volcanic rock samples display relatively elevated Th/Y ratios. This geochemical trend points to the influence of assimilation and fractional crystallization processes and further suggests that the mantle source was metasomatized by fluids released from the subducting slab.

Figure 11.

Nb/Y-Th/Y diagram of the studied volcanic rocks [51]. (AFC: Assimilation–Fractional Crystallization, UCC: Upper Continental Crust, OIB: Ocean Island Basalt, MORB: Mid-Ocean Ridge Basalt).

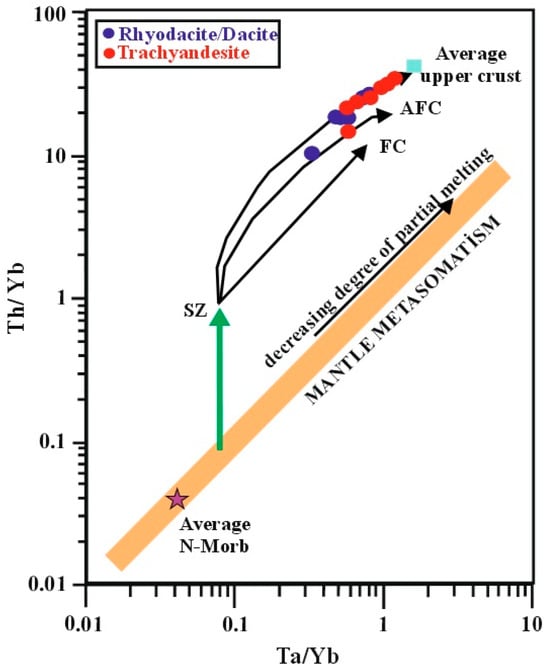

In the Ta/Yb–Th/Yb discrimination diagram (Figure 12), the studied volcanic rocks are characterized by elevated Th/Yb ratios and define a trend parallel to the mantle array. This distribution indicates the combined influence of subduction-related enrichment and a decrease in the degree of partial melting. Such a pattern suggests that the parental magmas were derived from a mantle source enriched by fluids released during subduction-related metasomatism and subsequently generated under relatively low degrees of partial melting. In other words, the melts originated from a mantle source that had been previously modified by subduction-derived fluids and later underwent partial melting at reduced extents [71,72]. The Ta/Yb and Th/Yb ratios are widely used to evaluate mantle source characteristics and the extent of crustal contamination, as Th is more sensitive to crustal processes than Yb and Ta [73]. The position of the samples on the diagram further implies that assimilation–fractional crystallization (AFC) processes played a significant role in the magmatic evolution of the studied volcanic rocks. A comparable influence of fractional crystallization has also been documented for Miocene–Pliocene volcanic rocks from central Armenia [74].

Figure 12.

Th/Yb versus Ta/Yb diagram of rhyodacite/dacite and trachyandesite samples from the Tuzla volcanic rocks [73]. Vectors indicating subduction enrichment and mantle metasomatism are after [73]. N-type OIB and average upper continental crust compositions were taken from [47] and [75], respectively. FC, fractional crystallization vector; AFC, assimilation coupled with fractional crystallization curve. (AFC: Assimilation–Fractional Crystallization, FC: Fractional Crystallization, SZ: Subduction Zone).

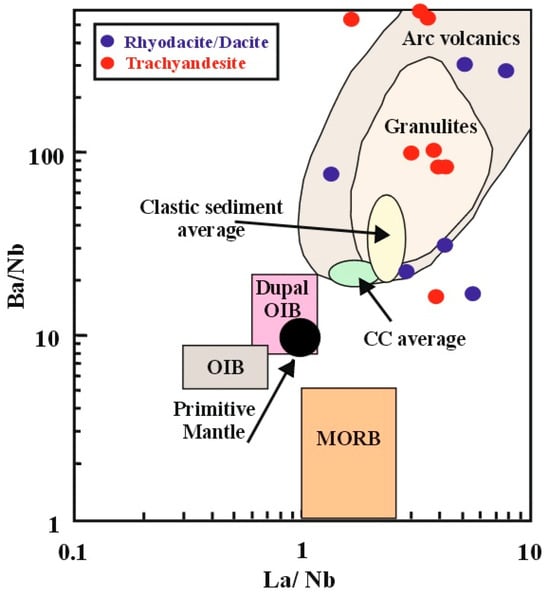

In the La/Nb versus Ba/Nb discrimination diagram (Figure 13), the studied volcanic rocks cluster within a field proximal to arc-related volcanic compositions. During subduction, light rare earth elements (LREEs) and large ion lithophile elements (LILEs; Ba, Sr, K, and Rb) are transported upward by fluids released from the subducting slab [61,62]. The elevated La/Nb and Ba/Nb ratios observed in these volcanic rocks therefore indicate that their mantle source was significantly influenced by subduction-related enrichment. For comparison, the Taşlıyayla volcanic rocks (Çaykara, Trabzon, NE Turkey) also plot within the arc volcanic field on the La/Nb–Ba/Nb diagram [76], exhibiting geochemical characteristics closely comparable to those of the Tuzla volcanics.

Figure 13.

La/Nb–Ba/Nb diagram of the investigated volcanic rocks (Primitive mantle from [47]; Continental crust from [75,77]; Dupal-OIB from [78]; Arc volcanics and Archean granulites from [79]. (OIB: Ocean Island Basalt, MORB: Mid-Ocean Ridge Basalt, CC: Continental Crust).

Although no isotope analyses were performed in the present study, the magma source characteristics of Miocene volcanic rocks in western Anatolia have been well constrained by previous isotopic investigations. Sr–Nd–Pb isotope data indicate that Miocene calc-alkaline to shoshonitic volcanic rocks were derived from a heterogeneous and enriched lithospheric mantle source that was variably modified by subduction-related components and subjected to limited crustal assimilation [3,80,81]. Elevated 87Sr/86Sr ratios and negative εNd values are generally interpreted to reflect enriched mantle domains rather than extensive upper-crustal contamination, whereas Pb isotope systematics point to mixing between depleted asthenospheric mantle and enriched mantle components. Furthermore, zircon Lu–Hf and δ18^{18}18O isotope data from felsic volcanic and plutonic rocks indicate predominantly mantle-derived magmas with subordinate crustal input during magma evolution [35,82]. Taken together, these regional isotopic constraints support a multi-component mantle source for Oligocene-Miocene magmatism in Western Anatolia related to post-collisional lithospheric thinning and asthenospheric upwelling.

5.3. Fractional Crystallization and Assimilation- Fractional Crystallization

The studied volcanic rocks are characterized by enrichment in light rare earth elements (LREEs) together with elevated La/Yb ratios, suggesting that fractional crystallization of hornblende played a significant role in controlling the relative depletion or enrichment of heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) [83]. Likewise, the presence or absence of Eu anomalies appears to be largely governed by the extent of plagioclase equilibration and/or fractionation within the magma [84]. These geochemical features indicate that the investigated volcanic rocks likely evolved from parental magmas derived from a common source. Comparative evaluation with the Yürekli volcanic rocks of northwest Türkiye [55] and the Early Miocene Şapçı volcanic rocks [61] further supports derivation from a similar magmatic source and a broadly comparable evolutionary history.

The interaction of mantle-derived magmas with crustal material during ascent, and the resulting contamination, provides important constraints on the source characteristics of volcanic rocks [73]. Previous studies have shown that fractional crystallization and assimilation–fractional crystallization (FC–AFC) processes play a fundamental role in the petrogenesis of intermediate calc-alkaline volcanic rocks formed in subduction-zone settings [85,86,87]. Trace element and rare earth element (REE) abundances, as well as their ratios, represent key geochemical indicators of the mineral phases removed from parental magmas during partial melting and subsequent evolutionary processes, including fractional crystallization, assimilation, and crustal contamination [87]. Accordingly, assimilation of crustal material is regarded as a major geodynamic process that significantly modifies and redistributes the trace element compositions of mantle-derived magmas [63,64].

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns and N-MORB–normalized multi-element diagrams of the studied volcanic rocks are presented in Figure 8. The samples are characterized by enrichment in large ion lithophile elements (LILEs; U, Th, Rb, and K), light rare earth elements (LREEs), and particularly Pb, whereas high field strength elements (HFSEs; Nb and Ti) are depleted. The weakly developed Eu anomalies observed in the samples (Figure 8a) indicate crystallization and/or fractionation of plagioclase and K-feldspar, while pronounced P depletions in the multi-element patterns (Figure 8b) point to apatite fractionation. The presence of marked negative Nb anomalies coupled with positive Pb anomalies (Figure 8b) is a typical geochemical feature reflecting continental crustal influence.

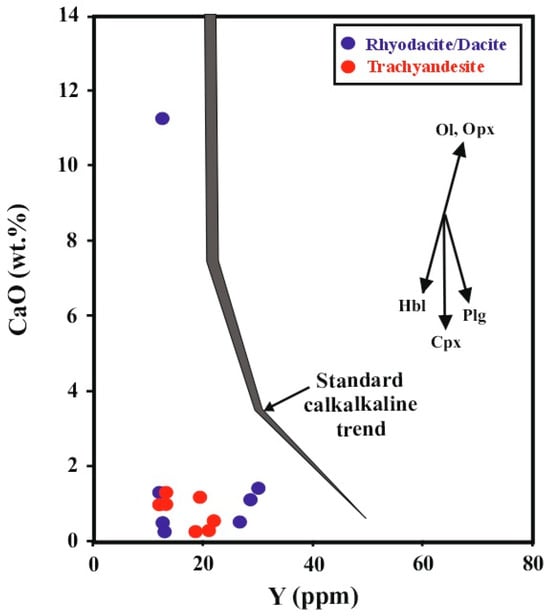

Within the calc-alkaline series, Ref. [88] used the CaO–Y diagram to distinguish between J- and L-type trends, corresponding to relative Y depletion and enrichment, respectively, compared to the standard calc-alkaline trend. In the CaO–Y diagram (Figure 14), nearly all of the studied samples plot on the Y-depleted side of the calc-alkaline reference line, defining a J-type trend. This distribution emphasizes the significant role of hornblende and plagioclase fractionation in the petrogenesis of the volcanic rocks. Similar mineralogical controls have been reported for Upper Oligocene–Lower Miocene volcanic rocks from the Karakavak and Çukurhüseyin villages (Balıkesir Province, northwestern Türkiye) [89], as well as for Early Eocene volcanic rocks from the Artvin region in, northeastern Türkiye [90].

Figure 14.

Y (ppm)-CaO (wt%) diagram of volcanic rocks in the study area [91].

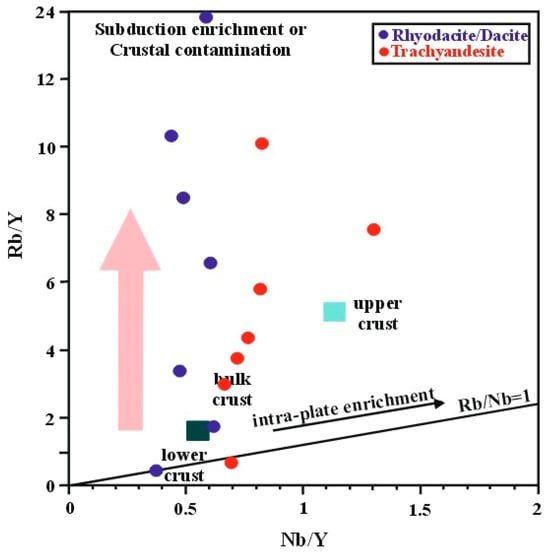

The relationship between fractional crystallization, source metasomatism, and/or crustal assimilation associated with subduction-derived fluids can be effectively evaluated using the Rb/Y versus Nb/Y diagram [73]. In this diagram, the studied volcanic rocks define a predominantly vertical trend and plot within the field characteristic of subduction-zone enrichment and/or crustal contamination (Figure 15). In contrast, intraplate magmatic enrichment is typically expressed by a positive correlation between Rb and Nb, corresponding to Nb/Y values of approximately 1 [91]. In the Tuzla volcanic suite, Nb/Y ratios range from 0.39 to 0.63 in the rhyodacite/dacite samples and from 0.68 to 1.35 in the trachyandesites, reflecting relative HFSE depletion that is characteristic of subduction-related magmatism. Comparable geochemical trends indicative of subduction-related enrichment or crustal contamination have also been documented in Late Cretaceous high-K volcanic rocks from the Central Pontides orogenic belt [92] and in Eocene–Oligocene volcanic units from the Momen Abad, eastern Iran [93].

Figure 15.

Nb/Y and Rb/Y graphs of Tuzla field volcanics [79]. (compositions of upper and lower crusts according to [75]).

6. Conclusions

Mineralogical, petrographic, and geochemical investigations of the Oligocene-Miocene volcanic rocks exposed in the Tuzla field, many of which record varying degrees of hydrothermal alteration, provide important constraints on the tectonic setting, magma source characteristics, and the roles of fractional crystallization and assimilation processes. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

- The Tuzla area hosts a complex Miocene volcanic system composed of andesitic, dacitic, and rhyolitic lavas, trachyandesites, pyroclastic deposits, ignimbrites, and the Kestanbol Pluton.

- Petrographic observations and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses indicate that the volcanic units are dominated by porphyritic dacitic–rhyodacitic and trachyandesitic rocks, which have been variably affected by pervasive silicification, iron oxide formation, and mineral opacification related to hydrothermal alteration.

- Geochemical data, particularly rare earth element (REE) systematics, demonstrate that fractional crystallization of primary mineral phases played a major role in the magmatic evolution of the Tuzla volcanics. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns show enrichment in light REEs relative to heavy REEs and broadly similar distribution trends, suggesting derivation from a common parental magma source.

- K2O–Na2O and AFM diagrams indicate high-K calc-alkaline, calc-alkaline, and tholeiitic affinities. Most rhyodacite/dacite samples and all trachyandesites plot within the tholeiitic field, reflecting compositional diversity within the volcanic suite.

- Tectonic discrimination diagrams collectively suggest that the Tuzla volcanic rocks were generated in both volcanic arc–related and intraplate magmatic settings, reflecting a complex tectonomagmatic evolution.

- Although moderate enrichments in Ba and Sr may partly reflect magma source characteristics and differentiation processes, the highest Ba and Sr concentrations are interpreted to result from post-magmatic hydrothermal fluid–rock interaction rather than primary magmatic compositions.

- The Tuzla volcanic suite includes rocks that preserve primary magmatic geochemical signatures as well as samples that have experienced varying degrees of hydrothermal overprinting. Overall, the volcanics were derived from a collision-related, enriched lithospheric mantle source and subsequently evolved through fractional crystallization and assimilation processes, accompanied by crustal contamination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and O.C.; Methodology, D.K. and O.C.; Formal analysis, D.K. and O.C.; Investigation, D.K.; Resources, D.K. and O.C.; Writing—original draft, D.K. and O.C.; Writing—review & editing, D.K. and O.C.; Visualization, D.K. and O.C.; Project administration, D.K. and O.C.; Funding acquisition, D.K. and O.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the TÜBİTAK 1002 Program (Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey), Project No. 123Y088.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a broader research project that includes field investigations. The authors thank Erhan Şener (Süleyman Demirel University, Isparta, Turkey) for his support during the fieldwork. The authors also thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which helped to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Erenoğlu, R.C.; Arslan, N.; Erenoğlu, O.; Arslan, E. Application of spectral analysis to Determine geothermal anomalies in the Tuzla Region, NW Turkey. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, Ş.C.; Dönmez, M.; Akçay, A.E.; Altunkaynak, Ş.; Eyüpoğlu, M.; Ilgar, Y. Biga Yarımadası Tersiyer Volkanizmasının Stratigrafik, Petrografik ve Kimyasal Özellikleri Biga Yarımadası’nın Genel ve Ekonomik Jeolojisi, MTA Rapor No: 11101. Ankara, Türkiye. 2009; Unpublished.

- Aldanmaz, E.; Pearce, J.A.; Thirlwall, M.F.; Mitchell, J.G. Petrogenetic evolution of Late Cenozoic, post collision volcanism in Western Anatolia, Turkey. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2000, 102, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunkaynak, Ş.; Genç, Ş.C. Petrogenesis and time-progressive evolution of the Cenozoic continental volcanism in the Biga Peninsula, NW Anatolia. Lithos 2008, 102, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, G.; Okay, A.I. Late Eocene–early Oligocene two-mica granites in NW Turkey (the Uludağ Massif): Water-fluxed melting products of a mafic metagreywacke. Lithos 2017, 268, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketin, İ. Anadolu’nun Tektonik Birlikleri. Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 1966, 66, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Yılmaz, Y. Tethyan evolution of Turkey: A plate tectonic approach. Tectonophysics 1981, 75, 181–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Y. Comparision of Young Volcanic Associations of Western and Eastern Anatolia under Conpressional Regime; A Review. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1990, 44, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.İ.; Siyako, M.; Bürkan, K.A. Biga Yarımadası’nın Jeolojisi ve Tektonik Evrimi. TPJD Bülteni 1990, 2, 83–121. [Google Scholar]

- Okay, A.İ.; Tüysüz, O. Tethyan sutures of northern Turkey. In Mediterranean Basins: Tertiary Extension Within the Alpine Orogen; Durand, B., Jolivet, L., Horvath, F., Seranne, M., Eds.; Geological Society Special Publications: London, UK, 1999; Volume 156, pp. 475–515. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, N.B.; Kelley, S.; Okay, A.I. Post-collision magmatism and tectonics in northwest Anatolia. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1994, 117, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.; Satır, M.; Maluski, H.; Siyako, M.; Monie, P.; Metzger, R.; Akyüz, S. Paleo- and Neo-Tethyan events in northwest Turkey: Geological and geochronological constraints. In Tectonics of Asia; Yin, A., Harrison, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 420–441. [Google Scholar]

- Okay, A.I.; Tansel, İ.; Tüysüz, O. Obduction, subduction and collision as reflected in the Upper Cretaceous-Lower Eocene sedimentary record of western Turkey. Geol. Mag. 2001, 138, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunkaynak, S.; Dilek, Y. Timing and Nature of Postcollisional Volcanism in Western Anatolia and Geodynamic İmplications. Postcollisional Tectonics and Magmatism in the Mediterranean Region and Asia; Dilek, Y., Pavlides, S., Eds.; Geological Society of America Special Paper: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; Volume 409, pp. 321–351. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, Z.; Erdem, D.; Temizel, İ.; Arslan, M. SHRIMP U–Pb zircon ages and whole-rock geochemistry for the Şapçı volcanic rocks, Biga Peninsula, Northwest Turkey: Implications for pre-eruption crystallization conditions and source characteristics. Int. Geol. Rev. 2017, 59, 1764–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Z.; Demir, H.; Altın, İ. U–Pb zircon geochronology and petrology of the early Miocene Göloba and Şaroluk plutons in the Biga Peninsula, NW Turkey: Implications for post-collisional magmatism and geodynamic evolution. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2020, 172, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.I. Geology of Turkey: A synopsis. Anschnitt 2008, 21, 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Genç, S.C.; Yılmaz, Y. Post Collisional Magmatism in Armutlu Peninsula, NW Anatolia; Abstracts; IAVCEI International Volcanology Congress: Ankara, Türkiye, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Delaloye, M.; Bingöl, E. Granitoids from Western and Nortwestern Anatolia: Geochemistry and Modeling of Geodynamic Evolution. Int. Geol. Rev. 2000, 42, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunkaynak, Ş. Collision-Driven Slab Break off Magmatism in North Western Anatolia. Turkey. J. Geol. 2007, 115, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, T.; Satır, M.; Steinitz, G.; Dora, A.; Sarıfakıoğlu, E.; Adis, C.; Walter, H.J.; Yıldırım, T. Biga Yarımadası ile Gökçeada, Bozcaada ve Tavşan Adalarındaki KB Anadolu Tersiyer Volkanizmasının Özellikleri. MTA Derg. 1995, 117, 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Y. An approach to the origin of young volcanic rocks of western Turkey. In Tectonic Evolution of the Tethyan Region; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 159–189. [Google Scholar]

- Genç, S.C. Evolution of the Bayramiç Magmatic Complex, Northwestern Anatolia. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1998, 85, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgenc, I.; Ilbeyli, N. Petrogenesis of the Late Cenozoic Egrigöz pluton in western Anatolia, Turkey: Implications for magma genesis and crustal processes. Int. Geol. Rev. 2008, 50, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, E. Geology and petrology of the Simav Magmatic Complex (NW Anatolia) and its comparison with the Oligo-Miocene granitoids in NW Anatolia: Implications on Tertiary tectonic evolution of the region. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2009, 98, 1655–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelević, D.; Akal, C.; Foley, S.F.; Romer, R.L.; Stracke, A.; Van Den Bogaard, P. Ultrapotassic mafic rocks as geochemical proxies for post-collisional dynamics of orogenic lithospheric mantle: The case of southwestern Anatolia, Turkey. J. Petrol. 2012, 53, 1019–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysal, N.; Öngen, A.S.; Şahin, S.Y.; Kasapci, C.; Hanilçi, N.; Peytcheva, I. Peritectic assemblage entrainment and mafic-felsic magma interaction in theLate Oligocene-Early Miocene Karadağ Pluton in the Biga Peninsula, northwest Turkey: Petrogenesis and geodynamic implications. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 30, 279–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krushensky, R.D. Volcanic rocks of Turkey. Bull. Geol. Surv. Jpn. 1976, 26, 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Duru, M.; Pehlivan, Ş.; Şentürk, Y.; Yavaş., F.; Kar, H. New Results on the Lithostratigraphy of the Kazdağ Massif in Northwest Turkey. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2004, 13, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dönmez, M.; Akçay, A.E.; Genç, Ş.C.; Acar, Ş. Middle-late Eocene volcanism and marine ignimbrites in Biga peninsula (NW Anatolia-Turkey). Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 2005, 131, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Okay, A.İ.; Satır, M. Coeval plutonism and metamorphism in a Latest Oligocene metamorphic core complex in northwest Turkey. Geol. Mag. 2000, 137, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaletto, L.; Jenny, C. Geology and correlations of the Ezine Zone: A Rhodope fagment in NW Turkey. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2004, 13, 145–176. [Google Scholar]

- Okay, A.I. The oxygen fugacity stability of deerite: An alternative view. J. Metamorph. Geol. 1987, 5, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, K.; Okay, A.I. Blueschists discovered east of Saros Bay in Thrace. MTA Derg. 1984, 97, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Altunkaynak, Ş.; Dilek, Y.; Genç, C.Ş.; Sunal, G.; Gertisser, R.; Furnes, H.; Foland, K.A.; Yang, J. Spatial, temporal and geochemical evolution of Oligo–Miocene granitoid magmatism in Western Anatolia, Turkey. Gondwana Res. 2012, 21, 961–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkle, P.; Satir, M.; Erler, A.; Ercan, T.; Bingol, E.; Orcen, S. Dating, geochemistry and geodynamic significance of the Tertiary magmatism of the Biga Peninsula, NW Turkey. Geol. Black Sea Reg. 1995, 117, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Karacik, Z. Ezine-Ayvacık (Çanakkale) Dolayında Genç Volkanizma-Plütonizma İlişkileri [Relationship Between Young Volcanism and Plutonism in Ezine-Ayvacık (Canakkale) Region]. Ph.D. Thesis, İstanbul Technical University, İstanbul, Turkey, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Karacık, Z.; Yılmaz, Y. Geology of ignimbrites and the associated volcano-plutonic complex of the Ezine area, northwestern Anatolia. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1998, 85, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Y. Geology of Western Anatolia: Active tectonics of northwestern Anatolia. In The Marmara Poly Project; VDF; Hochschulverlag Ag An Der ETH: Zürich, Switzerland, 1997; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, Y.; Genc, Ş.C.; Karacik, Z.; Altunkaynak, S. Two contrasting magmatic associations of NW Anatolia and their tectonic significance. J. Geodyn. 2001, 31, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akal, C. Coeval shoshonitic-ultrapotassic dyke emplacements within the Kestanbol pluton, Ezine–Biga peninsula (NW Anatolia). Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2013, 22, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, M.; Gevrek, A.I. Distribution and significance of hydrothermal alteration minerals in the Tuzla hydrothermal system, Canakkale, Turkey. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2000, 96, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevrek, A.İ.; Şener, M.; Ercan, T. Çanakkale-Tuzla Jeotermal alanının hidrotermal alterasyon etüdü ve volkanik kayaçların petrolojisi. Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 1985, 103, 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- Winchester, J.A.; Floyd, P.A. Geochemical discrimination of different magma series and their differentiation products using immobile elements. Chem. Geol. 1977, 20, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccerillo, A.; Taylor, S.R. Geochemistry of Eocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the Kastamonu Area, northern Turkey. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1976, 58, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, T.N.; Baragar, W.A.R. A guide to chemical classification of common volcanic rocks. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1971, 8, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. In Magmatism in Oceanic Basins; Saunders, A.D., Norry, M.J., Eds.; Geological Society Special Publications: London, UK, 1989; Volume 42, pp. 313–345. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.A.; Joron, J.L.; Treuil, M.; Norry, M.; Tarney, J. Elemental and Sr isotope variations in basic lavas from Iceland and the surrounding ocean floor: The nature of mantle source inhomogeneities. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1979, 70, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.H. Geologic Setting, Petrology, and Age of Pliocene to Holocene Volcanoes of the Stepovak Bay Area. In US Geological Survey Bulletin; Government Printing Omce: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; pp. 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gorton, M.P.; Schandl, E.S. From continents to island arcs: A geochemical index of tectonic setting for arc-related and within-plate felsic to intermediate volcanic rocks. Can. Mineral. 2000, 38, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A. Role of the sub-continental lithosphere in magma genesis at active continental margins. In Continental Basalts and Mantle Xenoliths (s. 230–249); Hawkesworth, C.J., Norry, M.J., Eds.; Shiva Publications: Nantwich, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bozan, F.; Aslan, Z. Büyükbostancı-Çiçekpınar (Balıkesir, KB Türkiye) yöresindeki Oligosen-Miyosen yaşlı kalk-alkalen volkanik kayaçların mineral kimyası, jeokimyası ve petrolojisi. Türkiye Jeol. Bülteni 2022, 65, 117–148. [Google Scholar]

- Şen, P.; Sarı, R.; Şen, E.; Dönmez, C.; Özkümüş, S.; Küçükefe, Ş. Geochemical features and petrogenesis of Gökçeada volcanism, Çanakkale, NW Turkey. Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 2020, 161, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.B.; Pearce, J.A.; Tindle, A.G. Geochemical characteristics of collision-zone magmatism. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1986, 19, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatçi, E.S.; Aslan, Z. Yürekli (Balıkesir) volkanitinin petrografisi ve petrolojisi: Biga yarımadasında (KB Türkiye) çatışma sonrasında felsik volkanizmaya bir örnek. MTA Derg. 2018, 157, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A.; Parkinson, I.J. Trace element models for mantle melting: Application to volcanic arc petrogenesis. In Magmatic Processes and Plate Tectonics; Prichard, H.M., Ed.; Geological Society Special Publications: London, UK, 1993; pp. 373–403. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz, A.J.; Varne, R.; Davies, G.R.; Wheller, G.E.; Foden, J.D. Magma source components in an arc-continent collision zone: The Flores-Lembata sector, Sunda arc, Indonesia. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1990, 105, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Johnson, K.T.M.; Kinzler, R.J.; Irving, A.J. High-field-strength element depletions in arc basalts due to mantle–magma interaction. Nature 1990, 345, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringwood, A.E. Slab-mantle interactions: 3. Petrogenesis of intraplate magmas and structure of the upper mantle. Chem. Geol. 1990, 82, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Peate, D.W. Tectonic implications of the composition of volcanic arc magmas. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1995, 23, 251–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elburg, M.A.; Bergen, M.V.; Hoogewerff, J.; Foden, J.; Vroon, P.; Zulkarmain, I.; Nasution, A. Geochemical trends across an arc-continent collision zone: Magma sources and slab-wedge transfer processes below the Pantar Strait volcanoes. Indones. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 2771–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churikova, T.; Dorendorf, F.; Wörner, G. Sources and fluids in the mantle wedge below Kamchatka, evidence from across-arc geochemical variation. J. Petrol. 2001, 42, 1567–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellmer, G.F.; Annen, C.; Charlıer, B.L.A.; George, R.M.M.; Turner, S.P.; Hawkesworth, C.J. Magma evolution and ascent at volcanic arcs: Constraining petrogenetic processes through rates and chronologies. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2005, 140, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, F.; Delfin, F.G.; Defant, M.J.; Turner, S.; Maury, R. The petrogenesis of magmas from Mt. Bulusan and Mayon in the Bicol arc, the Philippines. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2005, 150, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkesworth, C.J.; Turner, S.P.; McDermott, F.; Peate, D.W.; Van Calsteren, P. U-Th isotopes in arc magmas: Implications for element transfer from the subducted crust. Science 1997, 276, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, T.K.; Smith, E.I. Polygenetic Quaternary volcanism at Crater Flat, Nevada. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1994, 63, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.I.; Sánchez, A.; Walker, J.D.; Wang, K. Geochemistry of mafic magmas in the Hurricane Volcanic Field, Utah: Implications for small- and large scale chemical variability of the lithospheric mantle. J. Geol. 1999, 107, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, D.; Aslan, Z. Kalk-alkalen Şapçı (Balıkesir) Volkanitlerin Petrografisi ve Petrolojisi: Biga Yarımadası’nda (Kuzeybatı Türkiye) Çarpışma ile İlişkili Volkanizma. Türkiye Jeol. Bülteni 2015, 58, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, A.F.M. Mesozoic volcanism in the Middle East: Geochemical, isotopic and petrogenetic evolution of extension-related alkali basalts from central Lebanon. Geol. Mag. 2002, 139, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, B.L.; Wood, D.A.; Tarney, J.; Joron, J.L. Geochemistry of ocean island basalts from the south Atlantic: Ascension, Bouvet, St. Helena, Gough and Tristan da Cunha. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1987, 30, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Temizel, I.; Abdioğlu, E.; Kolaylı, H.; Yücel, C.; Boztuğ, D.; Şen, C. 40Ar–39Ar dating, whole-rock and Sr–Nd–Pb isotope geochemistry of post-collisional Eocene volcanic rocks in the southern part of the Eastern Pontides (NE Turkey): Implications for magma evolution in extension-induced origin. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2013, 166, 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydınçakır, E.; Şen, C. Petrogenesis of the post-collisional volcanic rocks from the Borçka (Artvin) area: Implications for the evolution of the Eocene magmatism in the Eastern Pontides (NE Turkey). Lithos 2013, 172, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Bender, J.F.; De Long, S.E.; Kidd, W.S.F.; Low, P.J.; Güner, Y.; Şaroğlu, F.; Yılmaz, Y.; Moorbath, S.; Mitchell, J.J. Genesis of collision volcanism in eastern Anatolia Turkey. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1990, 44, 189–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, V.A.; Chernyshev, I.V.; Sagatelyan, A.K.; Goltsman, Y.V.; Oleinikova, T.I. Miocene–Pliocene volcanism of Central Armenia: Geochronology and the role of AFC processes in magma petrogenesis. J. Volcanol. Seismol. 2018, 12, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Aydınçakır, E. Taşlıyayla (Çaykara, Trabzon, KD Türkiye) civarı Geç Kretase yaşlı kalk-alkali volkanik kayaçların petrografik ve Jeokimyasal Özellikleri. Gümüşhane Üniv. Fen Bilim. Derg. 2017, 7, 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Condie, K.C. Chemical composition and evolution of the upper continental crust: Contrasting results from surface samples and shales. Chem. Geol. 1993, 104, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.M.; Wu, F.; Lo, C.H.; Tsai, C.H. Crust–mantle interaction induced by deep subduction of the continental crust: Geochemical and Sr–Nd isotopic evidence from post-collisional mafic–ultramafic intrusions of the northern Dabie complex, central China. Chem. Geol. 1999, 157, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.M.; Zhang, Z.Q. Archean granulite gneisses from eastern Hebei Province, China: Rare earth geochemistry and tectonic implications. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1984, 85, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alıcı, P.; Temel, A.; Gourgaud, A.; Kieffer, G.; Gündoğdu, M.N. Petrology and geochemistry of potassic volcanism in the Gölcük area (Isparta, SW Turkey): Genesis of enriched alkaline magmas. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2002, 20, 867–886. [Google Scholar]

- Karaoğlu, Ö.; Helvacı, C.; Sunal, G. Geochemical and Sr–Nd–Pb isotopic constraints on the petrogenesis of Miocene volcanic rocks from western Anatolia: Implications for mantle source characteristics and crustal interaction. Lithos 2014, 184–187, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, T.; Rooney, T.O.; Hanan, B.B.; Yücel, C. Isotopic evidence for multi-component mantle sources beneath western Anatolia: Implications for post-collisional magmatism. Lithos 2021, 380–381, 105871. [Google Scholar]

- Romick, J.D.; Kay, S.M.; Kay, R.W. The influence of amphibole fractionation on the evolution of calc-alkaline andesite and dacite tephra from the central Aleutians, Alaska. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1992, 112, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arth, J.G. Some Trace Elements in Troundhjemites Their Implication to Magma Genesis and Paleotectonic Setting. In Developments in Petrology; U.S. Geological Survey: Denver, CO, USA, 1979; Chapter 3; Volume 6, pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, K.N.; Zhou, M.F.; Qi, L.; Chung, S.L.; Chu, C.H.; Lee, H.Y. Petrology and geochemistry at the Lower zone-Middle zone transition of the Panzhihua intrusion, SW China: Implications for differentiation and oxide ore genesis. Geosci. Front. 2013, 4, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P.; Zhou, M.F.; Luais, B.; Cividini, D.; Rollion-Bard, C. Disequilibrium iron isotopic fractionation during the high-temperature magmatic differentiation of the Baima Fe–Ti oxide-bearing mafic intrusion, SW China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 399, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak, V.D.; Spagnuolo, M.G.; Folguera, A.; Poma, S.; Jones, R.E.; Ramos, V.A. Late Cenozoic calc-alkaline volcanism over the Payenia shallow subduction zone, South-Central Andean back-arc (34 30′–37 S), Argentina. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2015, 64, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.B. Orogenic Andesites and Plate Tectonics; Earth Sciences Board and Oakes College: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Thirlwall, M.F.; Smith, T.E.; Graham, A.M.; Theodorou, N.; Hollings, P.; Davidson, J.P.; Arculus, R.J. High field strength element anomalies in arc lavas: Source or process? J. Petrol. 1994, 35, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.S.J.; Holland, J.G. Yttrium geochemistry applied to petrogenesis utilizing calcium-yttrium relationships in minerals and rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1974, 38, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Menzies, M.; Thirlwall, M. Evidence from Muriah, Indonesia, for the interplay of supra-subduction zone and intraplate processes in the genesis of potassic alkaline magmas. J. Petrol. 1991, 32, 555–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydınçakır, E. Subduction-related Late Cretaceous high-K volcanism in the Central Pontides orogenic belt: Constraints on geodynamic implications. Geodin. Acta 2016, 28, 379–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabi, S.; Emami, M.H.; Modabberi, S.; Zakariaee, S.J.S. Eocene-Oligocene volcanic units of momen abad, east of Iran: Petrogenesis and magmatic evolution. Iran. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 11, 126–140. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.