1. Introduction

Nickel and copper are pivotal strategic metals, playing indispensable roles in emerging fields such as new energy vehicles, energy storage systems, and advanced electronics. With the rapid expansion of the global new energy industry, the demand for these two metals is witnessing a sustained surge, further elevating their strategic significance in industrial development and national economic security [

1,

2].

Globally, major copper-nickel mines are distributed in regions including Sudbury (Canada), Norilsk (Russia), and South Africa. Sudbury, formed by ancient magmatic activity, hosts world-class sulfide deposits with high grades (1%–3% Ni, 1%–2% Cu) [

3]. Norilsk stands out for its massive reserves (~18 Mt Ni, ~10 Mt Cu), underpinning Russia’s metallurgical industry. South Africa forms small-to-medium deposits via complex geological structures, with average Ni grades of 0.5%–1.5% [

4]. All three regions generate sulfide deposits through magmatic differentiation mineralization, supplying over 60% of global nickel resources. In China, the Jinchuan copper-nickel sulfide deposit (Gansu province) stands as the primary source of nickel and copper resources, boasting a total resource reserve of 560 million tons and a nickel metal reserve of 5.5 million tons—accounting for over 70% of the national total [

5,

6]. The ores are characterized by complex mineral compositions: they contain valuable sulfide minerals such as pentlandite and chalcopyrite, while also associating with silicate gangue minerals including serpentine and talc [

7,

8]. A critical challenge in processing these ores lies in the pronounced “slime formation” tendency of gangue minerals—their brittle nature leads to excessive grinding into fine slime particles during the comminution process [

9].

Flotation remains the dominant preliminary enrichment technology for sulfide ores, including copper and nickel sulfides, due to its high efficiency and adaptability [

10]. Nevertheless, the flotation of low-grade copper-nickel ores is plagued by two core technical bottlenecks caused by gangue slimes. Firstly, heterogeneous agglomeration occurs between slime particles and valuable mineral surfaces, resulting in “slime coating” that masks the active sites of sulfide minerals, thereby hindering their interaction with flotation reagents [

11]. Secondly, fine gangue slimes are easily entrained in the froth layer during flotation, leading to an increase in magnesium content (derived from silicate gangue) in the concentrate and a consequent decline in product quality [

12]. To address the issue of magnesium reduction in copper-nickel concentrates, researchers have explored various technical pathways, mainly focusing on five directions: stage grinding and flotation/flash flotation to mitigate overgrinding, pre-acid leaching to clean sulfide mineral surface, development of high-efficiency dispersants/inhibitors for gangue suppression, exploration of photoelectric sorting for pre-enrichment, and optimization of flotation process parameters [

13,

14].

While extensive efforts have been devoted to inhibiting or dispersing gangue minerals for magnesium reduction, limited attention has been paid to the intrinsic differences in the influence of gangue minerals from different origins on valuable minerals. It is well-documented that minerals with the same name exhibit significant variations in elemental composition, crystal structure, and surface properties under different geological formation conditions, which in turn affect their beneficiability [

15,

16]. For instance, Yu et al. conducted flotation tests on pyrite samples from five distinct production areas and found that despite using the same flotation reagents, the flotation behavior and performance of pyrite varied substantially among different origins [

17]. Yang [

18] further demonstrated that subtle changes in the mineralogical properties of pyrite can exert varying degrees of influence on its flotation behavior. However, systematic studies on the differences in the flotation impact of gangue minerals from different origins on valuable sulfide minerals remain scarce, creating a research gap in this field.

The Jinchuan copper-nickel deposit has long been a research focus worldwide due to the exceptional difficulty in suppressing its associated serpentine. Against this background, this study aims to fill the aforementioned research gap by comparing the differential effects of serpentine from different origins on the flotation of valuable minerals, and ultimately elucidating the underlying reasons for the recalcitrance of serpentine in the Jinchuan deposit. Taking chalcopyrite and serpentine from the Gansu Jinchuan mining area, as well as serpentine from Liaoning Province, as research objects, this paper will conduct micro-flotation experiments, adsorption characteristic analyses, and elemental composition characterization. The findings are expected to provide valuable insights for relevant researchers and industrial practitioners in addressing the gangue suppression challenges during the flotation of sulfide ores.

2. Experimental

2.1. Minerals and Reagents

The chalcopyrite and serpentine specimens from Gansu Province utilized in this study were sourced from the Jinchuan mining district, while the serpentine sample from Liaoning Province was collected locally. The genesis of the Jinchuan copper-nickel deposit is dominated by magmatic segregation, deep-seated segregation-emplacement, and contact metasomatism [

19]. In contrast, the mineralization of Xiuyan in Liaoning is associated with complex geological processes, including crustal movement, magmatic intrusion, hydrothermal activity, and metamorphism [

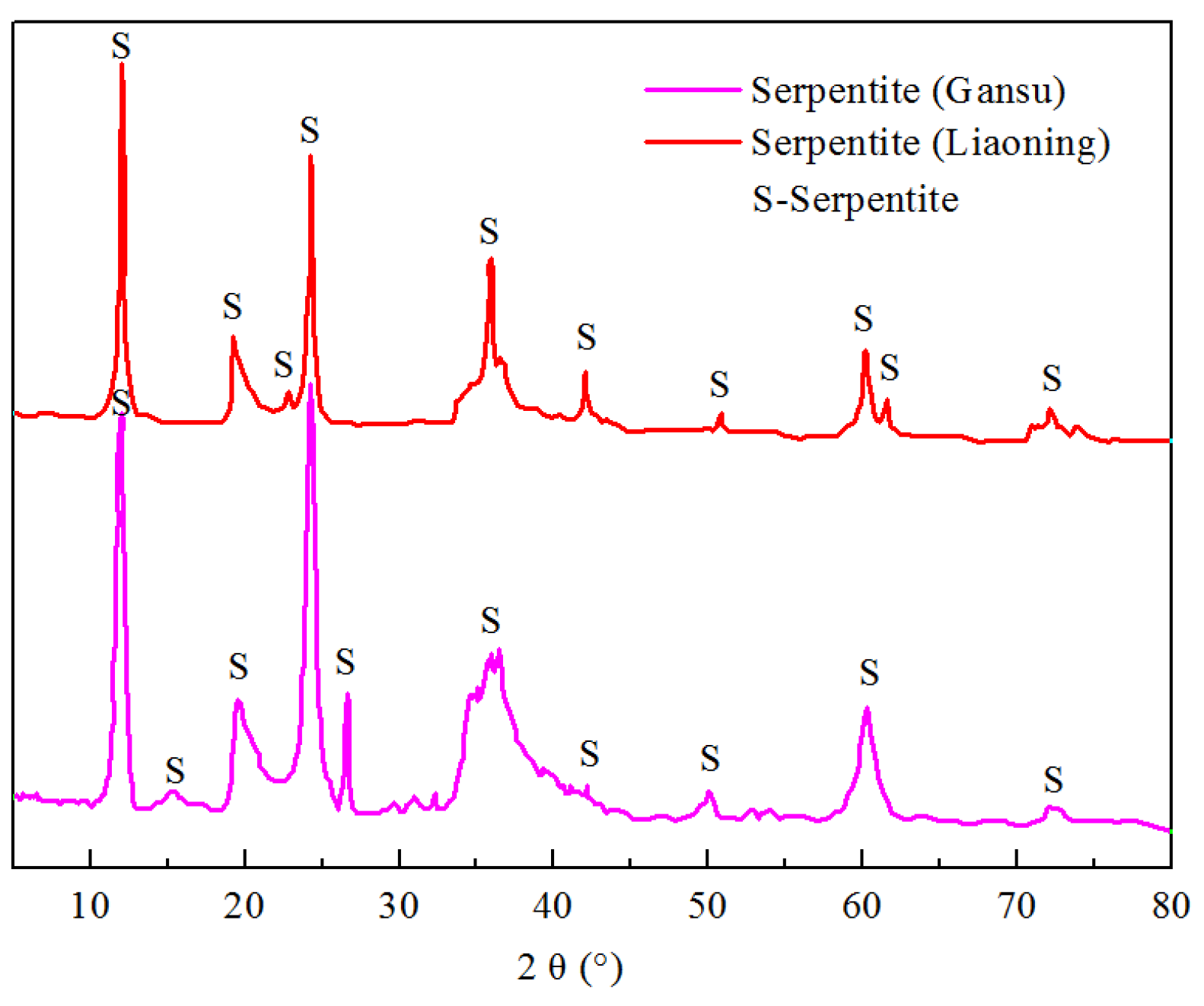

20]. The XRD patterns of serpentine minerals are shown in

Figure 1. The results show that their purities are all relatively high, but the XRD patterns are different. The mineral samples underwent preliminary manual sorting and crushing before being subjected to dry grinding in a ceramic ball mill. Subsequent dry sieving yielded chalcopyrite particles within the size range of −74 + 38 μm and serpentine particles finer than 38 μm, which were used for flotation and adsorption tests. For zeta potential measurements, the mineral samples were further ground to a particle size of less than 5 μm. These are the conventional methods for preparing mineral samples, which are mentioned in many flotation-related studies [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Artificial mineral mixtures were prepared by blending chalcopyrite and serpentine at a 1:1 mass ratio.

The collector sodium diethyldithiocarbamate (DDTC, analytical grade) and inhibitor sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC, analytical grade) employed in the experiments were supplied by Rin En Technology Development Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Both reagents exhibited good water solubility. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH), both of analytical purity and procured from Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, were utilized for pH adjustment. Methyl isobutyl carbinol (MIBC, analytical grade) served as the frother, and was also purchased from Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All experimental procedures were conducted using deionized water with a resistivity of 18.25 MΩ·cm.

2.2. Flotation Tests

Micro-flotation tests were performed using an XFGII laboratory flotation machine equipped with a 60 mL cell. For each test, 2.0 g of pure mineral particles were mixed with 38 mL of deionized water in the flotation cell, and the impeller speed was set to 1920 RPM. Following an initial 2 min stirring period, pH adjusters, the specified dosage of dispersant, collector, inhibitor, and frother were added to the slurry in sequence, with a 3 min stirring interval after each reagent addition. After completion of the flotation process, the concentrate and tailings were collected, filtered, and dried (in a vacuum drying oven at 40 °C). For single mineral flotation, recoveries were calculated using mass balance equations. In the case of artificial mixed mineral flotation, recovery was determined based on both the solid weight proportion and copper grade analysis [

25]. Each set of experimental conditions was replicated three times, and the results reported represent the average values of these triplicate tests.

2.3. Micro-Polarity Detection

Pyrene was first dissolved in hot water to reach saturation, followed by cooling to 25 °C and filtration to remove undissolved residual pyrene, thereby preparing a pyrene stock solution with a measured concentration of 6.52 × 10

−7 M. Mineral samples for subsequent measurements were prepared by mixing this stock solution with the relevant reagent(s) and mineral pulp, followed by a 1.5 h conditioning period. A Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Osaka, Japan) was used to record the steady-state emission spectrum of pyrene, which typically exhibits five characteristic peaks. The intensity ratio of the first to the third peak (I

3/I

1) is highly sensitive to the polarity of the microenvironment surrounding the probe molecules [

26]. This ratio varies with changes in micro-environmental polarity: it is generally larger than 0.5 in nonpolar solvents, ranges from 0.8 to 1.0 in surfactant micelles or semi-micelles, and lower than 0.6 in aqueous solutions [

27].

2.4. Electrokinetic Potential

Thirty milligrams of pure mineral particles were dispersed in 50 mL of 1 mM KCl solution to form a homogeneous suspension, which was then homogenized by magnetic stirring. Under continuous agitation, the predetermined pH adjusters, inhibitor, and collector were sequentially added to the suspension, followed by a 10 min conditioning period to ensure sufficient reagent-mineral interaction. After terminating the stirring process, the mixture was left to settle for a minimum of 30 min. Zeta potential measurements were performed using a Delsa 440sx Zeta Potential Analyzer (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK). All tests were conducted in at least three independent replicates, and the final results are presented as the average value.

2.5. XPS Detection

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses were performed on serpentine particles, both untreated and treated with depressant at the same concentration as used in flotation tests. Measurements were conducted using a K-Alpha 1063 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Co., Waltham, MA, USA), which utilizes an Al Kα sputtering source operated at 12 kV and 6 mA. The analysis chamber was maintained at a pressure of 1.0 × 10

−9 Pa during testing. The C 1s peak, corresponding to uncharged hydrocarbon at a binding energy (BE) of 284.8 eV, was used as a reference to calibrate the binding energies of all other spectral peaks for each sample, with necessary corrections applied to account for any shifts [

28]. Quantitative analysis and curve fitting of the XPS spectra were carried out using Thermo Scientific Avantage software version 5.9902.

2.6. ToF-SIMS Tests

A 2 g portion of serpentine with a particle size range of −38 μm was added into a beaker, mixed with deionized water, and subjected to ultrasonication for 2 min. Following cleaning, the supernatant was discarded. Samples exempt from CMC treatment were directly subjected to filtration and subsequent vacuum drying. For samples necessitating CMC modification, 50 mL of deionized water was first added, and the mixture was homogenized using a magnetic stirrer prior to the sequential introduction of CMC. Samples were directly filtered and dried in a vacuum oven. Testing was carried out using a TOF-SIMS V instrument (ION-ToF180 GmbH, Münster, Germany). The positive secondary ion mass spectra were calibrated with CH

3+,

54Fe

+, and C

2H

5+, while the negative secondary ion mass spectra were calibrated with CH

−, FeO

2−, and Cl

− [

29].

2.7. Electronic Micro-Area Analysis

An electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) is an analytical instrument that utilizes characteristic X-rays generated by the interaction of a focused electron beam with a sample to conduct micro-area compositional analysis, enabling the determination of the chemical composition of minerals in micro-regions of the sample. Specifically, the EPMA employs a narrow, accelerated, and focused electron beam as the probe to excite a tiny area of the specimen, prompting the emission of characteristic X-rays. By measuring the wavelength and intensity of these X-rays, qualitative or quantitative analysis of elements in the micro-region can be achieved [

30].

The equipment used in this experiment was a SHIMADZU EPMA-1720 electron probe microanalyzer imported from Shimadzu Corporation (Kyoto, Japan), with a test accuracy of up to 10 ppm. For testing, 20 mg of the −38 μm sample was subjected to gold sputtering treatment and then placed in the detection chamber for analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single Mineral Flotation

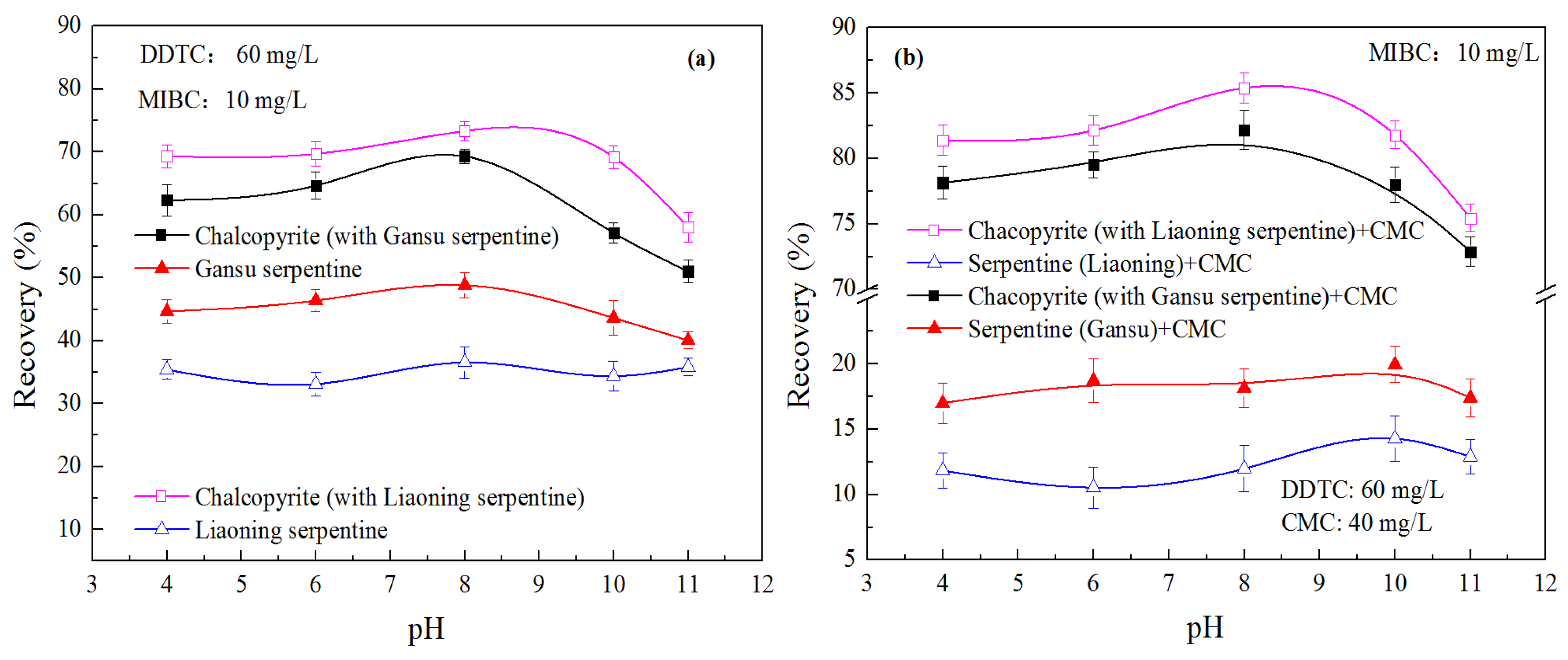

Single-mineral flotation tests were conducted on chalcopyrite and serpentine (characteristic minerals of Jinchuan ore, Gansu province) as well as exotic serpentine (from Liaoning Province) for comparison, with the results presented in

Figure 2. As shown in

Figure 2a, chalcopyrite exhibits good flotability in the DDTC collector system. When the pulp pH is less than 8, its recovery rate reaches around 90%, but a significant decline occurs when pH > 9. This is attributed to the formation of hydrophilic metal hydroxides on the surface of sulfide minerals under higher pH conditions [

31].

Serpentine minerals generally show low flotation recovery in sulfide mineral collector systems, and most of their recovery is presumably caused by water entrainment [

32]. Additionally, the single-mineral flotation tests compared the performance between exotic serpentine (Liaoning) and Gansu serpentine (Gansu). The flotation recovery of serpentine (Gansu) is slightly higher than that of the exotic serpentine, which is one of the key reasons for the greater difficulty in upgrading Jinchuan ore.

The effects of DDTC dosage on the flotation behavior of the three minerals are shown in

Figure 2b. The recovery of all three minerals tends to increase with the rise in collector concentration. However, there is an optimal collector dosage—beyond 60 mg/L, the recovery increase becomes insignificant. According to relevant studies, this is related to the collector concentration approaching its critical micelle concentration value, which slows down the further adsorption of surfactant [

33,

34].

Meanwhile, the results are consistent with those of the pH impact tests: under different collector concentrations, the recovery of Gansu serpentine is always slightly higher than that of the exotic serpentine. This indicates that more attention should be paid to the depression of Gansu serpentine in flotation processes.

3.2. Mixed Mineral Flotation

Mixed-mineral flotation systems can partially reflect the characteristics of actual ore flotation systems compared with single-mineral systems. Mixed system selects representative minerals, dominant valuable sulfide and gangue in Jinchuan ore, to reproduce core interactions (slime coating, entrainment) that govern actual flotation performance. Therefore, this study investigated the flotation behavior of mixed characteristic sulfide minerals and gangue minerals (represented by chalcopyrite and serpentine, respectively) from Jinchuan copper-nickel ore at a mass ratio of 1:1, with the results presented in

Figure 3.

When chalcopyrite was mixed with serpentine for flotation, a significant decrease in chalcopyrite’s recovery was observed—dropping from approximately 90% to 70% at pH = 8. Meanwhile, the flotation recovery of serpentine increased: Gansu serpentine showed a greater increase to around 45%, while exotic serpentine rose slightly to about 35%, as shown in

Figure 3a. It is evident that in the mixed-mineral system, not only does water entrainment of serpentine occur, but the slime coating of serpentine on the chalcopyrite surface also significantly reduces chalcopyrite’s flotability, leading to a substantial drop in its recovery [

35]. Additionally, some serpentine particles float by adhering to chalcopyrite surfaces, resulting in a marked increase in their own recovery—this is extremely unfavorable for the flotation separation of copper-nickel ore [

36].

Furthermore, it is found that in the mixed-mineral system, the floating behavior of Gansu serpentine (including water entrainment and adhesion to chalcopyrite) is more severe than that of exotic serpentine (Liaoning), exerting a greater negative impact on chalcopyrite’s recovery. This is another key factor contributing to the difficulty in processing Jinchuan ore.

We also investigated the effect of CMC, a commonly used slime depressant, on the flotation performance of the mixed minerals, with the results shown in

Figure 3b. When 40 mg/L of CMC was added, the flotation recoveries of both chalcopyrite and serpentine were partially restored: chalcopyrite’s recovery bounced back to around 80%, while the recoveries of both serpentine samples dropped below 20%. It is obvious that the slime inhibitor significantly reduces the adhesion of serpentine on the surface of chalcopyrite, restores the floatability of chalcopyrite, and at the same time reduces the chance of gangue minerals entering the concentrate [

37]. Even in the presence of the slime depressant CMC, the flotation behavior still shows that Gnasu serpentine has a higher floating rate than exotic serpentine, and the recovery of chalcopyrite in the Gansu serpentine system is lower than that in the exotic serpentine system. This indicates that serpentine (Gansu) is more difficult to depress.

Relevant data under the condition of pH = 8 are presented in the form of a qualitative and quantitative balance sheet (see

Table 1). In the absence of the depressant CMC, serpentine from Gansu is more prone to entrainment into the copper concentrate compared with that from Liaoning, resulting in lower Cu grade and Cu recovery of the concentrate. After adding the depressant, the Cu grades of both mixed mineral systems are correspondingly improved; however, overall, the performance of the chalcopyrite+Liaoning serpentine system remains superior. This further confirms that Gansu serpentine exerts a more significant adverse impact on the flotation indices of chalcopyrite and is relatively harder to depress. This is evidenced by the higher MgO content in the concentrate of the chalcopyrite+Gansu serpentine system even in the presence of the depressant.

3.3. Surface Electrical Property of the Particles

The zeta potential profiles of chalcopyrite—including its native state and after interaction with the collector DDTC (60 mg/L), slime depressant CMC (40 mg/L), and the CMC/DDTC reagent system—are illustrated in

Figure 4.

The zeta potential of chalcopyrite exhibits a decreasing trend with increasing pulp pH, with an isoelectric point (IEP) of approximately 5.2, consistent with previously reported findings [

38]. After exposure to the collector DDTC, the zeta potential of chalcopyrite undergoes a significant reduction, attributed to the extensive adsorption of anionic DDTC molecules on its surface. In contrast, interaction with the anionic inhibitor CMC results in only a marginal decrease in zeta potential, indicating weak binding between CMC ions and the chalcopyrite surface, which does not substantially alter the mineral’s surface microstate [

39].

When chalcopyrite particles are pretreated with CMC followed by DDTC, the extent of zeta potential reduction is comparable to that observed for chalcopyrite treated with DDTC alone. This suggests that the addition of anionic depressant CMC exerts negligible influence on the adsorption of DDTC onto the chalcopyrite surface, a conclusion that aligns well with the flotation experimental results.

The zeta potential curves of Gansu serpentine, exotic serpentine, and their interactions with collector DDTC (60 mg/L), slime depressant CMC (40 mg/L), and the CMC/DDTC reagent system are presented in

Figure 5.

The zeta potential of serpentine decreases with increasing pulp pH. The isoelectric point (IEP) of Gansu serpentine (Gansu) is approximately 8.2, while that of exotic serpentine (Liaoning) is around 7.8—both falling within the range of serpentine IEPs reported in the literature [

36]. After interacting with slime depressant CMC, the zeta potential of both serpentine samples drops significantly, attributed to the extensive adsorption of anionic CMC on their surfaces.

Furthermore, careful comparison reveals that CMC induces a greater reduction in the surface potential of exotic serpentine, indicating that exotic serpentine is more susceptible to the slime depressant CMC. This implies that Gansu serpentine is more difficult to depress and disperse than exotic serpentine. When interacting with anionic collector DDTC, the zeta potential of both serpentine samples shows only a slight decrease. This suggests weak interaction between DDTC and the serpentine surface, which does not significantly alter the mineral’s surface microstate. It also confirms that serpentine flotation is mainly related to water entrainment and adhesion to valuable mineral surfaces, rather than DDTC adsorption.

When serpentine particles are first treated with CMC followed by DDTC, the magnitude of zeta potential reduction is comparable to that observed for serpentine treated with CMC alone.

3.4. Surface Micro-Polarity

To clarify the differences in surface micropolarity between the two serpentine samples (Gansu and Liaoning) in aqueous and reagent solutions, the effect of collector DDTC dosage on the micropolarity (related to hydrophobicity) of different mineral pulp solutions was investigated, with the results presented in

Figure 6.

As shown in

Figure 6a, the pulp micropolarity of all minerals decreases with increasing DDTC dosage, indicating enhanced hydrophobicity on the mineral surfaces [

40]. Among them, sulfide minerals undergo a more significant reduction in micropolarity, while serpentine shows only a slight decrease. This demonstrates that collector DDTC typically acts selectively on sulfide minerals, which is consistent with the zeta potential test results.

Comparing the micropolarity parameters of sulfide minerals, it is found that in the DDTC system, chalcopyrite has the lowest surface micropolarity, while serpentine has the highest. This aligns with the single-mineral flotation results—sulfide minerals achieve high recovery, while serpentine exhibits poor flotability. When comparing Gansu and Liaoning serpentine, both have relatively high micropolarity. However, serpentine (Gansu) interacts more easily with the collector to a certain extent, leading to a slight reduction in its micropolarity. This makes it more prone to entering the concentrate, thereby lowering the concentrate grade.

The effect of slime depressant CMC dosage on the polarity (hydrophobicity) of different mineral pulp solutions was investigated, with the results shown in

Figure 6b. As the dispersant dosage increases, the pulp polarity of all minerals increases—meaning the hydrophobicity of mineral surfaces decreases. Among them, serpentine exhibits a more significant decrease in polarity, while sulfide minerals show only a slight decrease. This indicates that slime depressants typically act selectively on gangue minerals [

41].

When comparing Gansu serpentine and exotic serpentine (Liaoning), both have relatively high polarity. However, even under the action of the depressant, Gansu serpentine still has slightly lower polarity than exotic serpentine. This makes it relatively more likely to enter the concentrate, thereby reducing the concentrate grade, which is one of the reasons for the difficulty in beneficiation and separation of Jinchuan copper-nickel ore. Comparing the polarity parameters of sulfide minerals, it is found that in the inhibitor CMC system, chalcopyrite particles still have the lowest surface polarity, while serpentine has the highest polarity.

3.5. Results of XPS Detection

Based on previous characterizations such as zeta potential measurements, weak interactions were found between serpentine and sulfide mineral collector DDTC, as well as between chalcopyrite and depressant CMC. Thus, no further investigation into these interactions is conducted herein. XPS measurements were performed on the surfaces of the two serpentine samples (Gansu and Liaoning) before and after interaction with slime depressant CMC, and the high-resolution Mg 1s spectra are presented in

Figure 7.

After serpentine (Gansu) interacted with the depressant, the characteristic peak of the Mg 1s spectrum shifted from a binding energy of 1304.90 eV to 1306.83 eV, with a total shift of 1.93 eV. This indicates that chemical adsorption of CMC occurred on the serpentine surface [

42]. Meanwhile, through XPS spectrum analysis, the variations in the main atomic concentrations on the surface of Gansu serpentine before and after CMC treatment were obtained, and the results are summarized in

Table 1. Prior to interaction with CMC, the Mg atomic content on the serpentine surface was relatively high (10.29%); after interaction, this value decreased to 7.14% (a reduction of 3.15%), which also confirms the adsorption of CMC on the active Mg sites of Gansu serpentine [

43]. Additionally, it is observed that the surface contents of C and O atoms increased after the depressant interacted with Gansu serpentine. This is mainly due to the presence of these atoms in the CMC molecules adsorbed on the mineral surface.

After exotic serpentine (Liaoning) interacted with depressant CMC, the characteristic peak of the Mg 1s spectrum shifted from a binding energy of 1302.48 eV to 1306.94 eV, with a total shift of 4.46 eV. This also indicates that chemical adsorption of CMC occurred on the surface of this serpentine sample. Comparing the Mg 1s peak shift magnitude after CMC interaction, exotic serpentine shows a larger shift than Gansu serpentine. This demonstrates that Gansu serpentine is more difficult to interact with depressant CMC and harder to depress. Combined with findings from previous characterizations, Gansu serpentine exhibits more significant entrainment in flotation and is more refractory to depression compared to exotic serpentine (Liaoning)—this is another key factor contributing to the difficulty in beneficiation and separation of Jinchuan ore.

Table 2 also presents the variations in the main atomic concentrations on the surface of exotic serpentine (Liaoning) before and after CMC treatment. Prior to interaction with CMC, the Mg atomic content on the surface of exotic serpentine was relatively high (12.15%, compared to 10.29% for Gansu serpentine), providing more active sites for the depressant to act on [

44]. After interaction, this value decreased to 5.09% (a reduction of 7.06%). This confirms that CMC interacts with the active Mg sites on exotic serpentine, and the greater reduction in Mg atomic content on exotic serpentine further demonstrates the stronger interaction between the dispersant and exotic serpentine.

3.6. Results of ToF-SIMS

Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry is a highly sensitive and powerful surface analysis technique. It facilitates understanding of the interactions between flotation reagents and mineral surfaces by identifying characteristic ion fragments. ToF-SIMS analyses were performed on serpentine before and after interaction with slime depressant CMC, and the results are presented in

Figure 8.

The contents of OH

−, Ni

+, NiOH

+ and other components on the surface of Gansu serpentine are higher than those of exotic serpentine (Liaoning), while the contents of Mg

+, MgOH

+, SiO

2− and other components are lower. Take MgOH

+ as an example, the ion image of Gansu serpentine (

Figure 8c) is darker than that of exotic serpentine (

Figure 8d), indicating the higher ion strength of MgOH

+ at exotic serpentine (Liaoning). This is in good agreement with the XPS surface atomic concentration data.

After interaction with depressant CMC, the contents of Mg, Ni, Si and other components on the surface of serpentine (Gansu) all decreased, indicating the adsorption of the depressant at these sites [

45]. The contents of O, OH and other components increased—since the depressant molecules contain O elements, this also confirms the adsorption of the depressant on the mineral surface. Meanwhile, the appearance of the MgCOO

− component further verifies the adsorption of CMC on the serpentine surface.

Comparing the changes in the content of the MgCOO

− component on the surfaces of serpentine (Gansu) and exotic serpentine (higher in Liaoning serpentine), it can be inferred that the interaction between the depressant and exotic serpentine is stronger than that with Gansu serpentine [

46]. In other words, Gansu serpentine is relatively more difficult to disperse, which is consistent with the conclusions from previous experimental results. After the interaction, the surface Mg content of exotic serpentine is lower than that of Gansu serpentine, indicating that Mg sites are the main targets for the depressant CMC. These sites are covered by CMC molecules, leading to a reduction in their detected quantity. The experimental results further verify the reliability of the aforementioned conclusions from the perspective of adsorbed ion fragments.

3.7. Composition of Mineral Elements

The standard chemical composition of serpentine is Mg

6Si

4O

10(OH)

8, with ideal mass fractions of 43.6% MgO, 43.6% SiO

2, and 13.1% H

2O [

47]. Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA) of serpentine single minerals from Jinchuan copper–nickel ore revealed the following average mass fractions: 45.482% SiO

2, 38.668% MgO, and 4.586% FeO. For serpentine from Liaoning Province, the corresponding average values are 45.317% SiO

2, 41.012% MgO, and 4.148% FeO. As shown in

Table 3. The slight imbalance stems from unlisted trace components and the inability of EPMA to detect hydroxyl groups (OH

−) in serpentine.

The EPMA results (

Table 3) show that the MgO content of serpentine from Liaoning falls within the theoretical composition range of ideal serpentine, while that from Gansu is slightly lower, consistent with the well-documented Mg loss induced by magmatic hydrothermal alteration in Jinchuan deposit. Direct comparisons with existing literature are limited due to the scarcity of published compositional data for serpentines from these two specific localities (magmatic hydrothermal genesis for Gansu and sedimentary-metamorphic genesis for Liaoning) in previous studies. Thus, this work fills the gap in published data for serpentines from key deposits, providing a valuable reference for subsequent related research.

Since EPMA cannot detect OH− content in minerals, the theoretical OH− content was substituted for chemical formula calculation. Based on the theoretical formula, the theoretical mass fractions of Mg and Si should be 26.31% and 20.27%, respectively. EPMA results showed that the mass fractions of Mg and Si in Gansu serpentine are 23.201% and 21.225%, while those in Liaoning serpentine are 24.607% and 21.1148%. The actual contents of Mg and Si are essentially consistent with the theoretical values and formula, confirming the good representativeness of the serpentine samples used.

Notably, multi-point EPMA measurements indicated that although serpentine is inherently a magnesium-rich silicate mineral, Gansu serpentine has a slightly lower Mg content compared to Liaoning serpentine. This leads to fewer active Mg sites exposed on the surface of Gansu serpentine after crushing and grinding—as reflected in the XPS and TOF-SIMS results—making it difficult for dispersants to act extensively and achieve effective depression [

48]. This provides an in-depth explanation for the refractory depression characteristic of serpentine, a typical gangue mineral in Jinchuan ore, which is one of the key reasons why Jinchuan ore has long attracted the attention of numerous researchers. This offers a clear research roadmap for relevant engineers: follow-up work can leverage our mechanistic insights to optimize reagents and processes, gradually bridging to industrial application.

4. Conclusions

This study clarifies origin-driven differences between Gansu and Liaoning serpentines governing chalcopyrite flotation, addressing a global gap in copper-nickel ore processing. World-class deposits universally face serpentine-related flotation inefficiencies, yet prior global research treated serpentine as homogeneous, neglecting genesis impacts. Gansu serpentine has lower MgO content and fewer active sites than Liaoning serpentine, leading to weaker CMC interactions—evidenced by smaller XPS Mg 1s shifts and lower MgCOO− content in ToF-SIMS. It causes severer chalcopyrite slime coating and entrainment; even with CMC, its recovery remains higher, limiting chalcopyrite recovery restoration. These findings confirm elemental composition-driven surface variations are the root of Gansu serpentine’s refractory depression. Beyond Jinchuan, this work provides a universal framework for global low-grade copper-nickel ores with low-MgO silicate gangues, guiding targeted depressant development and scalable flotation optimization to enhance global complex sulfide ore upgrading efficiency.