Abstract

Apatite is a key indicator mineral whose chemical signature can reveal the genesis and evolution of ore-forming systems. However, correctly interpreting these signatures requires a robust discrimination between apatite types formed by different geological processes, such as metamorphism and hydrothermal activity. This study aims to chemically characterize and genetically classify apatite samples from the Slyudyanka deposit (Siberia, Russia) to establish discriminative geochemical fingerprints for metamorphic and hydrothermal apatite types. We analyzed 80 samples of apatite using total reflection X-ray fluorescence (TXRF) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The geochemical data were processed using principal component analysis (PCA) and k-means cluster analysis to objectively discriminate the apatite types. Our analysis reveals three distinct geochemical groups. Metamorphic veinlet apatite is defined by high U and Pb, low REE, Sr, and Th, and suprachondritic Y/Ho ratios. Massive metamorphic apatite from silicate–carbonate rocks shows extreme REE enrichment and chondritic Y/Ho ratios. Hydrothermal–metasomatic apatite features high Sr, Th, and As, with intermediate REE concentrations and chondritic Y/Ho ratios. Furthermore, we validated the critical and anomalous Y concentrations in the metamorphic veinlet apatite by cross-referencing TXRF and ICP-MS data, confirming the reliability of our measurements for this monoisotopic element. We successfully established diagnostic geochemical fingerprints that distinguish apatite formed in different geological environments at Slyudyanka. The anomalous Y/Ho ratio in metamorphic veinlet apatite serves as a key discriminant and provides insight into specific fractionation processes that occurred during the formation of phosphorites in oceanic environments, which later transformed to apatites during high-grade metamorphism without a change in the Y/Ho ratio. This work underscores the importance of multi-method analytical validation for accurate geochemical classification.

1. Introduction

Apatite is a common accessory mineral in most igneous and metamorphic rocks. The capacity of apatite to incorporate various rare earth and volatile elements makes it a valuable indicator mineral for ore deposit exploration. Furthermore, it is increasingly used as a tool for diagnosing substance sources in sedimentary basins and establishing localization conditions, which is essential for paleogeodynamic reconstructions [1,2,3]. The trace element composition of apatite, particularly its rare earth element (REE) content, is of dual significance. It records the mineral’s formation history [4,5,6,7] while also indicating its potential as a source for these critically important metals, which are vital for the global transition to renewable energy and advanced technologies. The REE composition of apatite has long been utilized as a proxy for ancient seawater chemistry and paleomarine environmental reconstruction, with the expectation that hydrogenous (seawater-derived) REE signals will be preserved [8].

The yttrium-to-holmium (Y/Ho) ratio is a sensitive geochemical discriminant. In igneous systems and related hydrothermal fluids, Y and Ho behave coherently due to their similar ionic radii and charge (CHARAC behavior), maintaining a near-chondritic ratio (~28) [9,10,11,12,13]. In contrast, oxidative scavenging in seawater fractionates this pair, producing characteristic super-chondritic Y/Ho ratios (>52) [14]. Studies of hydrothermal and magmatic apatite confirm its diagnostic utility; for example, Zhuxi hydrothermal apatite has suprachondritic Y/Ho, while associated magmatic apatite is chondritic [15,16,17]. Non-chondritic Y/Ho ratios and tetrad effects in apatite can signal advanced magmatic fractionation, fluid interaction, and rare metal mineralization potential [9,11,15,17,18,19,20].

However, the systematic geochemical characterization of apatite formed in high-grade metamorphic terrains, and its discrimination from apatite of clear hydrothermal affiliation within the same complex, is less well-established. The Slyudyanka crystalline complex (Siberia, Russia) presents an ideal natural laboratory to address this problem. It is a granulite facies terrane containing both metamorphic apatite (derived from sedimentary phosphorites and silicate–carbonate rocks) and later hydrothermal–metasomatic apatite in phlogopite veins [21]. This study aims to (1) establish diagnostic geochemical fingerprints for the three main apatite types (hydrothermal–metasomatic, metamorphic veinlet, massive metamorphic) in the Slyudyanka deposit and (2) evaluate the persistence of the Y/Ho anomaly as a tracer for a marine sedimentary protolith through granulite facies metamorphism.

For the analysis of apatite, analytical methods are essential. One of the perspective methods for apatite analysis is total reflection X-ray fluorescence (TXRF), a microanalytical technique requiring minimal sample mass and no calibration standards [22,23,24,25]. Our prior work has optimized TXRF for multi-element analysis of apatite across various size ranges via a direct acid digestion preparation. The method demonstrates accuracy comparable to inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) with sufficient sensitivity for geochemical studies, offering a rapid and cost-effective analysis. Thus, prior to proceeding to geochemical interpretations, the third aim was to demonstrate the efficacy of TXRF as a primary, cost-effective analytical tool for such provenance studies, validated against ICP-MS. By resolving these aims, we provide a new geochemical framework for apatite classification in complex metamorphic settings and contribute to understanding fluid–rock interaction and sedimentary heritage in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB).

2. Geological Setting, Materials, and Methods

2.1. Geological Setting

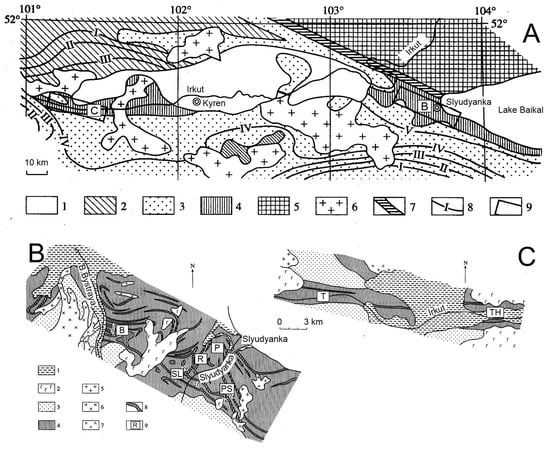

The Slyudyanka crystalline complex includes the most highly metamorphosed (granulite facies) part of the Khamar-Daban terrane of the CAOB, directly adjacent to the southern Siberian Craton [21] (Figure 1A). The Slyudyanka complex is a type locality of the Early Paleozoic Baikal Collisional Belt [26]. Geological maps of the two studied areas of the Slyudyanka Complex are shown in Figure 1B,C.

Figure 1.

Tectonic structure of the Slyudyanka metamorphic complex (A) with enlarged geological maps of regions within the Slyudyanka settlement (B) and Obrub-Haradaban area (C) (compiled based on [27]). Symbols in (A): 1—Cenozoic sediments; 2—Ediacaran–early Paleozoic sediments; 3–4—metamorphic complexes of Hangarul and Slyudyanka series, respectively; 5—Archean–early Proterozoic metamorphic rocks of the Siberian Craton; 6—Paleozoic granites; 7—Major Sayan Fault; 8—metamorphic mineral zones (I—garnet, II—staurolite, III—sillimanite, IV—K-feldspar, V—hypersthene); 9—enlarged geological maps. Symbols in (B,C): 1—Cenozoic sediments; 2—Cenozoic basalts; 3–4—metamorphic complexes of Hangarul and Slyudyanka series, respectively; 5–7—early Paleozoic granites, syenites, and gabbros, respectively; 8—horizons of metaphosphates; 9—sampling sites with indexes as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concentrations (μg/g) of Slyudyanka apatite samples determined by the TXRF method. Samples with code names B, P, PS, SL, and R are from the Kultuk formation, and T and TH are from the Perevalnaya formation.

Table 1.

Concentrations (μg/g) of Slyudyanka apatite samples determined by the TXRF method. Samples with code names B, P, PS, SL, and R are from the Kultuk formation, and T and TH are from the Perevalnaya formation.

| Sample | Genetic Type | Mn | As | Sr | Y | La | Ce | Pb | Th | U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-2307-A | Metamorphic | 8.4 | 10.4 | 580 | 24.0 | <LOD | 21.7 | 11.0 | 14.6 | 154 |

| B-233-A | Metamorphic | 39.3 | 3.2 | 601 | 23.1 | <LOD | 33.0 | 26.4 | 17.6 | 107 |

| B-2457-A | Metamorphic | 13.9 | 6.4 | 689 | 43.6 | <LOD | 19.4 | 33.6 | 3.1 | 252 |

| B-592-A | Silicate–carbonate | 244 | <LOD | 191 | 1702 | 156 | 873 | 6.5 | <LOD | 15.5 |

| B-595-A2 | Silicate–carbonate | 271 | 1.4 | 356 | 774 | 272 | 817 | 8.1 | <LOD | 14.7 |

| B-513-A5 | Silicate–carbonate | 182 | <LOD | 436 | 882 | 621 | 2020 | 3.9 | 10.6 | 0.0 |

| P-701-A | Metasomatic | 49.4 | 6.2 | 1490 | 32.1 | <LOD | 67.2 | 23.6 | 85.7 | 66.3 |

| P-706-A | Metasomatic | 106 | 16.1 | 1506 | 41.7 | <LOD | 53.5 | 10.3 | 98.9 | 77.4 |

| P-708-AG | Metasomatic | 48.8 | 6.3 | 1484 | 32.0 | <LOD | 60.8 | 23.9 | 90.1 | 64.8 |

| P-709-A | Metasomatic | 42.1 | 8.7 | 1421 | 27.5 | <LOD | 56.6 | 5.3 | 85.2 | 61.1 |

| P-712-A | Metasomatic | 41.9 | 12.0 | 1463 | 23.4 | <LOD | 60.9 | 9.9 | 82.9 | 66.9 |

| P-714 | Metasomatic | 36.8 | 14.0 | 1271 | 35.0 | 76.0 | 89.0 | 20.0 | 124 | 61.0 |

| P-720-A | Metasomatic | 44.1 | 13.5 | 1403 | 47.6 | <LOD | 83.7 | 3.4 | 67.9 | 59.0 |

| P-720-A1 | Metasomatic | 43.0 | 16.6 | 1495 | 53.7 | 19.3 | 79.5 | 5.5 | 72.4 | 57.1 |

| P-726-AB | Metasomatic | 55.3 | 6.4 | 1140 | 50.3 | <LOD | 70.7 | 13.8 | 66.4 | 40.0 |

| P-726-AB1 | Metasomatic | 57.5 | 9.7 | 1257 | 49.6 | <LOD | 52.7 | 3.4 | 75.4 | 40.5 |

| P-726-AG | Metasomatic | 83.4 | 9.8 | 1222 | 43.0 | <LOD | 51.3 | 12.2 | 69.8 | 43.9 |

| P-747 | Metasomatic | 51.2 | 12.0 | 1352 | 38.0 | 66.0 | 66.0 | 20.0 | 100 | 55.0 |

| P-789-AC | Metasomatic | 43.6 | 35.7 | 1371 | 48.6 | 43.8 | 130 | 11.2 | 72.8 | 110 |

| P-798 | Metasomatic | 60.7 | 26.0 | 1404 | 56.0 | 80.0 | 118 | 23.0 | 111 | 64.0 |

| P-804-A | Metasomatic | 72.7 | 15.4 | 1228 | 38.1 | 30.4 | 58.2 | 3.8 | 111 | 61.4 |

| P-804-A | Metasomatic | 73.2 | 15.4 | 1217 | 37.8 | <LOD | 68.9 | 5.9 | 92.3 | 56.9 |

| P-810 | Metasomatic | 62 | 18.0 | 1358 | 46.0 | 71.0 | 122 | 24.0 | 124 | 75.0 |

| P-811-AP | Metasomatic | 64.5 | 14.1 | 1428 | 54.0 | <LOD | 83.1 | 5.2 | 111 | 62.0 |

| P-811-AC | Metasomatic | 80.4 | 22.4 | 1398 | 58.3 | <LOD | 106 | 7.3 | 104 | 64.3 |

| P-832-AZ | Metasomatic | 43.0 | 20.9 | 1354 | 51.3 | <LOD | 102 | 15.0 | 95.8 | 69.5 |

| P-832-A3 | Metasomatic | 42.6 | 11.8 | 1328 | 53.9 | <LOD | 99.6 | 19.3 | 93.7 | 73.4 |

| P-833-AC | Metasomatic | 38.4 | 7.3 | 1320 | 42.4 | 24.6 | 89.2 | 7.0 | 85.2 | 38.5 |

| P-853-A31 | Metasomatic | 33.3 | 13.6 | 1646 | 66.1 | 37.5 | 142 | 7.1 | 77.4 | 65.0 |

| P-853-A32 | Metasomatic | 35.1 | 16.1 | 1693 | 64.6 | 89.1 | 176 | 2.5 | 70.2 | 44.9 |

| P-853-AF | Metasomatic | 50.7 | 10.6 | 1449 | 75.3 | <LOD | 129 | 17.8 | 80.9 | 60.9 |

| P-853-AG | Metasomatic | 71.9 | 11.4 | 1346 | 46.9 | 20.4 | 80.7 | 17.2 | 74.4 | 57.4 |

| P-853-AΓ | Metasomatic | 74.5 | 14.2 | 1280 | 45.7 | 29.0 | 89.1 | 4.1 | 70.8 | 56.3 |

| P-853-AC | Metasomatic | 40.5 | 9.5 | 1502 | 45.6 | <LOD | 92.9 | 8.4 | 96.3 | 59.4 |

| P-864 | Metasomatic | 85 | 11.0 | 1295 | 26.0 | 46.0 | 63.0 | 19.0 | 90.0 | 56.0 |

| P-893-A | Metasomatic | 65.4 | 19.6 | 1315 | 45.9 | <LOD | 79.8 | 18.3 | 121 | 54.1 |

| P-923-A | Metasomatic | 46 | 30.0 | 1602 | 104 | 267 | 494 | 32.0 | 151 | 133 |

| P-934-A | Metasomatic | 60.6 | 13.8 | 1410 | 58.4 | <LOD | 46.5 | 5.1 | 86.0 | 52.9 |

| PS-312-AG | Metasomatic | 20.0 | 9.0 | 1892 | 46.0 | 220 | 319 | 29.0 | 131 | 56.0 |

| PS-313 | Metasomatic | 13.5 | 9.5 | 2158 | 55.6 | 127.4 | 306 | 29.0 | 120 | 64.2 |

| PS-313-AC | Metasomatic | 14.5 | 11.9 | 1803 | 47.4 | 92.2 | 271 | 11.3 | 103 | 37.5 |

| PS-314-AG | Metasomatic | 17.9 | 13.0 | 1778 | 34.0 | 129 | 177 | 20.0 | 118 | 49.0 |

| PS-316 | Metasomatic | 10.0 | 8.7 | 1895 | 58.6 | 90.7 | 317 | 25.0 | 108 | 58.5 |

| PS-317 | Metasomatic | 11.8 | 12.1 | 1530 | 42.9 | 118 | 236 | 8.1 | 87.1 | 45.0 |

| PS-317-AC | Metasomatic | 14.9 | 11.0 | 1990 | 38.9 | 148 | 287 | 4.4 | 118 | 49.2 |

| PS-318 | Metasomatic | 12.7 | 13.1 | 1823 | 36.8 | 46.2 | 194 | 13.4 | 87.8 | 51.4 |

| PS-318-AG | Metasomatic | 16.9 | 8.8 | 1928 | 31.0 | 46.7 | 168 | 15.0 | 86.5 | 29.2 |

| PS-319-A | Metasomatic | 21.0 | 14.0 | 1466 | 25.0 | 84.0 | 96.0 | 18.0 | 96.0 | 44.0 |

| PS-334-A | Metamorphic | 201 | 7.6 | 364 | 4.7 | <LOD | 35.6 | 11.9 | <LOD | 82.6 |

| PS-353 | Metamorphic | 5.0 | 4.0 | 557 | 64.0 | 34.0 | 49.0 | 46.0 | 10.0 | 220 |

| PS-354-A | Metamorphic | <LOD | 5.6 | 1094 | 51.7 | <LOD | <LOD | 28.9 | <LOD | 208 |

| PS-355-A | Metamorphic | 195 | 4.5 | 326 | 4.6 | <LOD | 29.0 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 79.0 |

| PS-406-AMG | Silicate–carbonate | 653 | <LOD | 1202 | 466 | 1017 | 1942 | 2.2 | 8.8 | 9.6 |

| PS-414-AMG | Silicate–carbonate | 524 | 4.7 | 1578 | 705 | 691 | 2048 | 3.2 | 31.0 | 16.8 |

| PS-573-A | Metasomatic | 68 | 12.0 | 2028 | 38.0 | 105 | 134 | 26.0 | 125 | 103 |

| R-1-A | Metasomatic | 38.9 | 15.6 | 1252 | 50.5 | 23.0 | 98.3 | <LOD | 107 | 50.7 |

| R-712-A1 | Metasomatic | 48.3 | 7.7 | 1484 | 25.2 | <LOD | 61.0 | 22.0 | 88.2 | 58.7 |

| SL-254-A | Metamorphic | 23.0 | 2.5 | 500 | 29.7 | 50.2 | 52.8 | 30.3 | <LOD | 116 |

| SL-257-A | Metamorphic | 55.5 | 8.6 | 343 | 51.9 | <LOD | <LOD | 10.7 | 3.7 | 123 |

| SL-258-A | Metamorphic | 12.8 | 9.8 | 499 | 26.4 | <LOD | 21.2 | 9.6 | <LOD | 125 |

| SL-264 | Metamorphic | 13 | <LOD | 507 | 43.0 | 22.0 | 22.0 | 32.0 | 7.0 | 218 |

| SL-265-A | Metamorphic | 25.2 | <LOD | 733 | 19.6 | <LOD | 33.0 | 19.3 | <LOD | 223 |

| SL-266-A | Metamorphic | 64.0 | 4.8 | 287 | 2.7 | <LOD | <LOD | 11.2 | <LOD | 50.4 |

| SL-271-A | Metamorphic | 4.9 | 4.8 | 461 | 25.7 | <LOD | <LOD | 4.8 | <LOD | 82.0 |

| SL-271-A5 | Metamorphic | <LOD | 4.8 | 450 | 19.5 | <LOD | 20.2 | 9.6 | 5.9 | 84.3 |

| SL-273-A1 | Metamorphic | 18.3 | 3.4 | 577 | 15.7 | <LOD | 26.3 | 16.7 | <LOD | 154 |

| SL-276 | Metamorphic | <LOD | <LOD | 712 | 67.0 | 54.0 | 45.0 | 38.0 | 63.0 | 119 |

| SL-288-AG | Metamorphic | 29.2 | <LOD | 518 | 26.5 | <LOD | 20.4 | 22.4 | <LOD | 98 |

| SL-291-AG | Metamorphic | 17.8 | 7.8 | 541 | 60.9 | <LOD | 21.8 | 23.3 | <LOD | 300 |

| SL-291-A3 | Metamorphic | 16.7 | 11.4 | 578 | 66.4 | <LOD | 24.1 | 19.6 | <LOD | 320 |

| T-93-A | Metamorphic | 31.3 | 2.9 | 388 | 10.8 | <LOD | <LOD | 9.0 | <LOD | 52.9 |

| T-93-A2 | Metamorphic | 25.8 | <LOD | 374 | 8.3 | <LOD | <LOD | 10.4 | <LOD | 52.3 |

| T-95-A | Metamorphic | 46.9 | <LOD | 440 | 10.3 | <LOD | <LOD | 15.4 | <LOD | 33.9 |

| T-95-A1 | Metamorphic | 17.6 | 0.0 | 508 | 2.5 | <LOD | <LOD | 9.1 | <LOD | 32.5 |

| T-97-A | Metamorphic | 38.0 | 3.9 | 470 | 8.7 | <LOD | <LOD | 13.5 | <LOD | 38.9 |

| T-97-A1 | Metamorphic | 40.9 | 0.0 | 494 | 10.0 | <LOD | 33.3 | 4.4 | <LOD | 35.5 |

| TH-701-A | Metasomatic | 44.9 | 5.3 | 1530 | 38.9 | 22.1 | 77.7 | 27.9 | 88.6 | 70.3 |

| TH-715 | Metamorphic | 34 | <LOD | 321 | 32.0 | 14.0 | <LOD | 18.0 | 8.0 | 55.0 |

| TH-74-A | Metamorphic | 21.6 | 3.8 | 429 | 39.0 | <LOD | <LOD | 18.3 | <LOD | 69.8 |

| TH-78-A1 | Metamorphic | 22.3 | 2.9 | 335 | 5.4 | <LOD | 21.7 | 10.1 | <LOD | 30.3 |

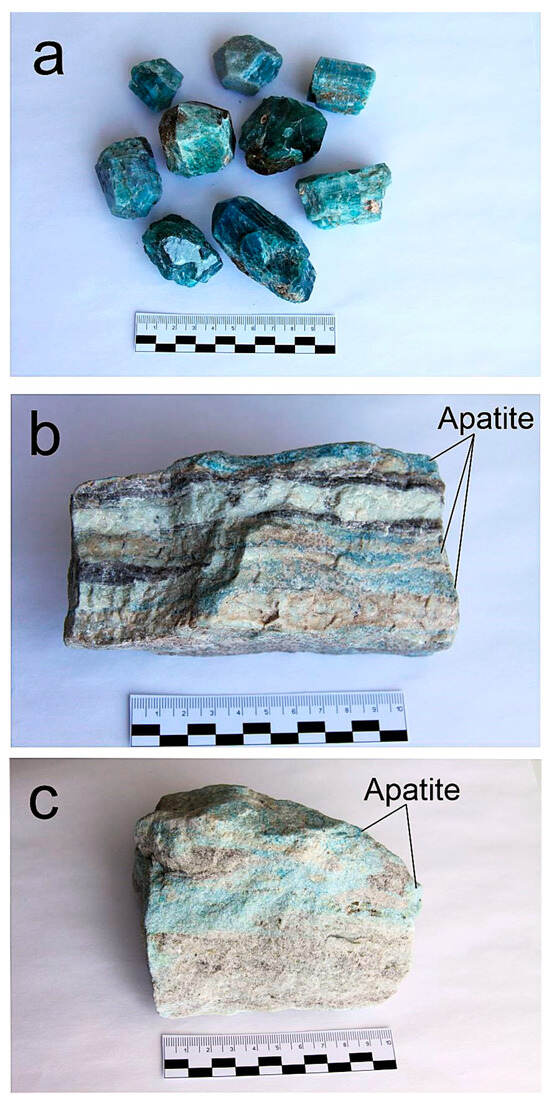

The Slyudyanka complex is located within the CAOB, near the southern end of Lake Baikal. The peak of metamorphism at Slyudyanka was estimated in a time range of ~495–477 Ma, depending on isotope dilution thermal ionization mass spectrometry (ID-TIMS) or laser ablation (LA) ICP-MS dating techniques and using igneous or metamorphic rocks [28,29,30]. After the granulite peak of metamorphism, the Slyudyanka complex underwent a complex thermal history with the youngest K-Ar closure age for phlogopite at ~270 Ma [31]. The most detailed description of the layered strata, structure, magmatism, metamorphism, and evolution of the Slyudyanka complex is provided in a monograph [21]. The 80 apatite samples analyzed in this study are legacy specimens collected from the Slyudyanka complex during geological fieldwork in the early 1980s. While precise geographic coordinates are not available, their genetic context is well-constrained by original sample labels, associated mineral assemblages, and the extensively mapped geology of the region [27]. Two main groups were distinguished from the selected apatite samples: metamorphic and metasomatic. The metamorphic group consists of two subgroups. The first subgroup includes apatite crystallized from metasedimentary rocks (metaphosphorites). Phosphate-bearing siliceous dolomites underwent metamorphism under granulite facies conditions at a temperature of ~800 °C and a pressure of ~6 kbar. These are sheet bodies that occur as a part of the Slyudyanka Series. The rocks are usually banded; bands (layers) of quartz, diopside, and apatite alternate in composition. Samples of the metamorphic type are designated by the indices «SL», «TH», «T», and «B». The second subgroup, called the silicate–carbonate (calciphyre) type, consists of nests or inclusions of apatite in sheet metamorphic rocks composed of green diopside. These samples are labeled as «B-5», fine-crystalline apatite from a nest of green rocks, and «PS-4», black fine-crystalline varieties. The metasomatic group includes apatite from phlogopite-bearing veins, which provides the name of the whole complex (Slyudyanka means micaceous in Russian). These are usually large-crystalline varieties ranging in size from several cm to several dm. They vary in color—blue, greenish, and sometimes with a violet tint. They are labeled as «PS», «P», and «R». Figure 2 shows pictures of three different types of apatite: hydrothermal–metasomatic, metamorphic apatite, and massive metamorphic apatite of silicate–carbonate rocks.

Figure 2.

Slyudyanka apatite: (a) hydrothermal–metasomatic apatite crystals of various colors (dark, green, colorless) of phlogopite veins, (b) veinlets of metamorphic apatite of deep blue color crystallized from metaphosphorites, (c) massive metamorphic apatite of light blue color from silicate–carbonate rocks.

2.2. Analytical Instrumentation

2.2.1. Total Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence (TXRF) Analysis

Elemental analysis via TXRF was conducted using a benchtop S2 PICOFOX spectrometer (Bruker Nano Analytics, Berlin, Germany). The instrument is equipped with a Mo-anode X-ray tube, a multilayer monochromator for beam conditioning, and a 30 mm2 silicon drift detector with an energy resolution of <150 eV for the Mn Kα line. Measurement parameters were standardized. The live time for one analysis was 500 s, with the X-ray tube operating at 50 kV and 0.50 mA. Samples were prepared on quartz carriers, which served as both sample holders and reflectors. The acquired spectra were processed using the vendor’s «Spectra 7.8.2» software.

2.2.2. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) Analysis

A subset of representative samples was analyzed for their rare earth element (REE) content using an Agilent 7900 quadrupole ICP-MS (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The instrument was operated in standard mode. Sample introduction was achieved using a MicroMist nebulizer (Glass Expansion, Melbourne, Australia) coupled with a Scott-type spray chamber (Glass Expansion, Melbourne, Australia) maintained at a constant temperature by a Peltier cooling element (Glass Expansion, Melbourne, Australia). Standard nickel sampler and skimmer cones were used for the interface.

2.3. Reagents

All acids—hydrofluoric acid (HF, 48%), nitric acid (HNO3, 65%), and perchloric acid (HClO4, 70%–72%)—were of ultrapure grade (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Single-element stock solutions of gallium (Ga), indium (In), and bismuth (Bi) (each at 1000 mg/L, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) were used for internal standardization. All dilutions were performed using ultrapure deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm, Elga Labwater, High Wycombe, UK).

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.4.1. TXRF

Apatite samples were first mechanically crushed and homogenized using a mortar grinder (Retsch RM-200, RETSCH GmbH, Haan, Germany). For digestion, approximately 10 mg of the resulting powder was transferred to a PTFE vessel. To this, 100 μL of concentrated HNO3 was added, and the sealed vessel was heated on an electric hotplate at 160 °C for 30 min. After cooling, the solution was diluted with 800 μL of ultrapure water and spiked with 100 μL of a Ga internal standard solution. A precise aliquot of this final solution was then deposited onto a quartz carrier and dried on a heating plate to form a thin film for analysis.

2.4.2. ICP-MS

For ICP-MS analysis, a larger aliquot of 50 mg of powdered apatite was digested in a 35 mL PTFE beaker using a mixture of 5 mL HF, 2 mL HNO3, and 1 mL HClO4. The beakers were swirled for homogenization and left at room temperature for 24 h to ensure the initial reaction. A stepped heating program was then applied: 3 h at 110 °C, followed by 3 h at 140 °C, and a final 3 h at 180 °C. After evaporation to incipient dryness, the residues were re-treated with 1 mL of water and 1 mL of HNO3 and evaporated again. The final residue was dissolved in 10 mL of 10% (v/v) HNO3 with gentle heating to yield a clear solution. This solution was transferred to a 50 mL volumetric flask and made up to volume with ultrapure water, resulting in a primary stock solution. A subsequent dilution was performed by taking a 1 mL aliquot of this stock, diluting it with 4 mL of 2% (v/v) HNO3 in a polystyrene tube, yielding a total dilution factor of 5000. Immediately before analysis, internal standards (In and Bi) were added to all solutions at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL [32].

2.5. Quantification and Data Treatment

2.5.1. TXRF Quantification and Figures of Merit

Elemental concentrations (Ci, in mg/kg) were calculated using the following established equation:

where Cis is the internal standard concentration, Ni and Nis are the net peak areas of the analyte and internal standard, and Sᵢ and Sᵢₛ are their respective relative sensitivities.

The limit of detection (LOD) for each element was derived from the spectrum using the following formula:

where NBG is the background count under the analyte’s peak.

The elements were chosen according to the sensitivity restriction of TXRF because some REEs were not determined. The following elements were determined by TXRF: Mn, As, Sr, Y, La, Ce, Pb, Th, and U. The detection limits for the TXRF method ranged from 1 μg/g for Mn, As, Sr, Y, Pb, Th, and U; for La and Ce, they were 15 μg/g. The measurement combined expanded uncertainties (UCA) for Y; Th did not exceed 3.9%, Sr and U did not exceed 6.9%, Mn, As, La, and Ce did not exceed 9.9%, and Pb did not exceed 16.6%. The analytical figures of merit were calculated for the TXRF method in our previous publication [22].

2.5.2. ICP-MS Performance

The uncertainty of the ICP-MS measurements was maintained below, 5% for Y, 7% for light REEs, and 10% for heavy REEs, following established laboratory procedures [32]. Method detection limits ranged from 0.021 to 0.24 μg/g for middle and heavy REEs and from 0.44 to 2.0 μg/g for light REEs.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All multivariate statistical analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and k-means clustering, were performed using Origin 2024 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Prior to multivariate analysis, concentration data below the LOD were replaced with a value of LOD/√2, a common practice to minimize bias in statistical treatment of censored data. The dataset was then auto-scaled (mean-centered and divided by the standard deviation for each variable) to ensure all elements contributed equally to the PCA and cluster analysis, regardless of their absolute concentration ranges.

3. Results

3.1. TXRF and ICP-MS Results

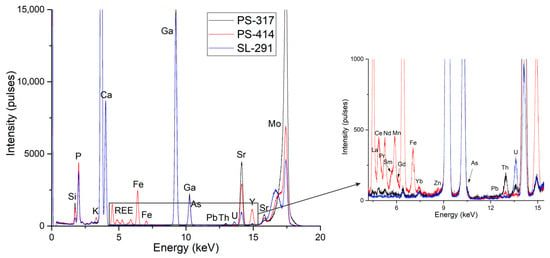

Table 1 presents the concentrations of 80 apatite samples from Slyudyanka obtained using the TXRF method. Figure 3 shows the spectra of apatite samples that differ most in elemental composition. For the correct interpretation of spectra, all intensities were normalized to the Kα line of the internal standard Ga, which was added in the same quantity to all samples. From Figure 3, we can observe a large variety of intensities obtained for different types of apatite. The full range of elements identified in the samples, from P to U, is displayed in the spectra. The air between the sample and the detector causes the Ar peak to appear, the addition of the internal standard gives the Ga peak, and the Mo-anode X-ray tube’s scattering radiation causes the Mo peak. The spectra also showed a significant amount of Si, which can be explained by the use of quartz carriers as sample holders and reflectors.

Figure 3.

TXRF spectra, normalized to GaKα, of apatite samples: PS-317—hydrothermal–metasomatic apatite of phlogopite veins; PS-414—massive metamorphic apatite of silicate–carbonate rocks; SL-291—metamorphic veinlet apatite of metaphosphorites.

The results of 80 samples were observed, and the representative parts, including 17 samples, were measured using ICP-MS. The samples were chosen according to the classification of apatite types based on TXRF data. Table 2 presents the REE + Y data. ICP-MS was applied to determine the rare earth element (REE) composition for subsequent geochemical research. A comparison of the data obtained using the two methods showed good agreement between the results.

Table 2.

Concentrations (μg/g) of REEs in Slyudyanka apatite samples determined by the ICP-MS method. Samples with code names B, P, PS, SL, and R are from the Kultuk formation, and T and TH are from the Perevalnaya formation.

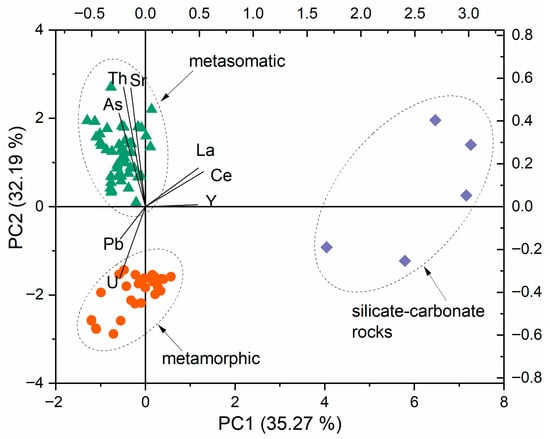

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate analysis is a common method for the discrimination of apatite of different origins [33]. Different statistical methods, including principal component analysis, partial least squares [33], support vector machine [7], and decision tree algorithms [34], are used to classify apatite samples.

We applied a convenient chemometric technique called principal component analysis (PCA). The study of the score and loading scatter plots allowed the identification of the criteria for clustering objects. PCA was applied to the elemental composition obtained for the apatite samples, which enabled us to classify them into three main groups. Figure 4 presents the score scatter plots constructed in projections of the first and second principal components of PC1-PC2. The cumulative percentage of variance in the correlation matrix for the first two principal components was greater than or equal to 67% for all scatter plots. Correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between Th and Sr (r = 0.88), La and Ce (r = 0.95), and Ce and Y (r = 0.72). The following elements, Ce, La, and Y, were the most significant variables for the first PC. The second PC was characterized by the dispersion of Th and Sr.

Figure 4.

PCA results based on the TXRF element composition of apatite samples from Slyudyanka. Three apatite groups were obtained by their genesis: the metamorphic group is highlighted in red; the hydrothermal–metasomatic group is highlighted in green; and blue rhombs are apatite of silicate–carbonate rocks, whose origin is also metamorphic.

The samples with relatively high U concentrations were in the metamorphic group, and those with high Sr and Th concentrations were in the hydrothermal–metasomatic group. The sample, which belongs to the latter group, differs in REE content and is assigned to apatite of silicate–carbonate rocks. The PCA results showed that the obtained groups of apatite samples were consistent with the geochemical data on the genesis of these samples.

Application of generalized cluster analysis by k-means is a fast and easy way for provenance analysis without preliminary preparation of the dataset, for example, excluding outliers. This method was applied under the following conditions: the k-means algorithm, the squared Euclidean distance method, and a training/test samples ratio of 2:1. Table 3 presents the results of CA of apatite samples, characterized by type. The total number of clusters is equal to 3, as well as the actual quantity of apatite types.

Table 3.

Frequency table for cluster analysis of apatite samples characterized by type.

3.3. Geochemistry of Slyudyanka Apatite

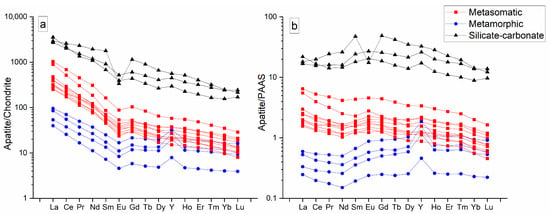

To study the geochemistry of apatite from Slyudyanka, we used data on the rare element composition obtained by ICP-MS (Table 2). Chondrite-normalized and PAAS-normalized diagrams were constructed for Slyudyanka apatite (Figure 5). At first glance, there are significant differences among the three types of apatite.

Figure 5.

Chondrite-normalized (a) and PAAS-normalized diagrams (b) obtained based on the ICP-MS results of measurements of Slyudyanka apatite.

Figure 5a shows the chondrite-normalized diagram for the three groups of apatite samples. Metasomatic apatite shows a regular trend from high to low REEs according to the atomic number of elements, with a small negative Eu anomaly. Metamorphic apatite is characterized by lower concentrations of light and middle REEs and a more irregular pattern with a small negative Eu anomaly and a notable positive Y anomaly. The values of heavy REEs of metamorphic apatite were comparable to those of metasomatic apatite. Apatite from silicate–carbonate rocks has significantly higher REE content than metasomatic and metamorphic apatite samples. Two analyzed samples of this type have no Eu anomaly, and one studied sample has a very deep negative Eu anomaly.

Figure 5b shows the REE normalization to Post-Archean Australian Shale (PAAS). This normalization reflects the REE depletion of metamorphic apatite relative to an average marine sedimentary rock represented by PAAS. Metasomatic apatite is only slightly REE-enriched relative to PAAS, whereas apatite of silicate–carbonate rocks is highly REE-enriched at the level of REE–ore concentrations.

4. Discussion

The distinct trace element signatures of the three apatite groups are controlled by differing mineral stabilities and fluid compositions during their formation. For the metamorphic veinlet apatite, the high U and low REE, Th, and Sr concentrations are a direct function of high-grade metamorphic conditions. During granulite facies metamorphism, the stability of monazite effectively sequesters the available light REE and Th [35], while plagioclase incorporates Sr [36]. Consequently, apatite crystallizing in this environment is depleted in these elements. Uranium, being less compatible in the structures of monazite and common rock-forming minerals, partitions into the apatite structure. The high Pb content is predominantly radiogenic, accumulating from the in situ decay of U over geological time. In contrast, the hydrothermal–metasomatic apatite derives its composition from an evolved fluid. Its high Sr content suggests interaction with, or derivation from, a carbonate-rich or plagioclase-bearing source. Concurrently, elevated Th and As point to a metasomatic fluid enriched in incompatible and metalloid elements, consistent with its formation in phlogopite-bearing veins. The extreme REE enrichment in the massive metamorphic apatite from silicate–carbonate rocks indicates a protolith and formation environment where competing REE host minerals, like monazite, were absent. In this setting, apatite became the primary sink for all available REEs during metamorphic recrystallization.

The clear separation between the two metamorphic groups on the PCA plot (Figure 4) is a direct reflection of their distinct protoliths. The veinlet apatite (red) inherited a high-U, low-REE signature from a marine phosphorite precursor where REEs were sequestered by monazite during metamorphism, whereas the massive apatite (blue) formed from an REE-rich calc–silicate rock where apatite became the dominant REE host.

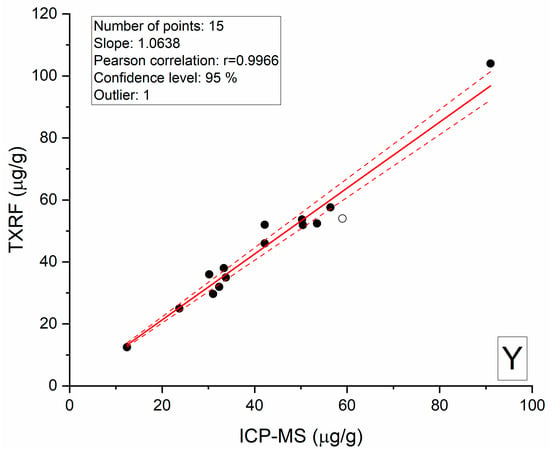

The main feature of metamorphic apatite is a positive anomaly of Y relative to Ho. Yttrium and Ho are two elements with similar geochemical affinity [9,10,11,12]. Therefore, deviation of the Y/Ho ratio from the chondritic value requires special analytical control. To verify the trueness of the analytical results, Y from the same samples was determined by the ICP-MS and TXRF methods (Figure 6), which showed good correlation over the entire concentration range. The correlation coefficient r was 0.9966, and the measured concentration range was from 12 to 104 μg/g. Thus, the anomalously high, suprachondrite Y/Ho ratio is a characteristic of metamorphic apatite.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the Y determination results in apatite samples by TXRF and ICP-MS. One outlier is highlighted by a blank circle. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence interval.

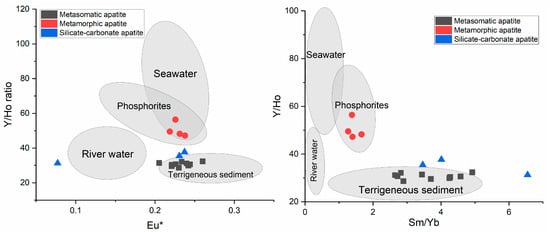

Figure 7 presents the Y/Ho—Sm/Yb ratio diagram for apatite from Slyudyanka, divided into three types. The values of apatite were compared to the reference values of terrigenous sediments, river water, modern seawater, and phosphorites, presented as clouds on the diagram. According to Zhang et al. [8], Y and Ho exhibit comparable vertical distribution patterns and ionic radii in the contemporary ocean; however, Ho is scavenged from the water column by particulates or ionic species almost twice as quickly as Y. The terrigenous protolith sediments of the Slyudyanka metamorphic rocks are characterized by relatively uniform, low Y/Ho ratios equal to 23–32 [37], and wide Sm/Yb ratios from 1 to 5, whereas modern seawater exhibits variable but generally higher Y/Ho ratios, commonly 50–100 [38], but narrow Sm/Yb ratios that do not exceed 0.97. Y/Ho ratios of river water are in the range 28–48, with almost no variation in Sm/Yb values (0.18–0.30) [14]. Phosphorites have the following characteristics: Y/Ho ratios of 43–75 and Sm/Yb ratios of 1–2 [39]. Figure 7 shows that the metamorphic apatite dots are inside the cloud of the phosphorites reference data. The Y/Ho ratio changes in seawater, which is why it accumulates in the phosphorites that form in seawater. Apatite of silicate–carbonate rocks has a chondritic Y/Ho ratio and resembles terrigenous rocks. REEs are immobile elements during high-grade metamorphism when little fluid is involved [40]. The remaining protholite Y/Ho signature in metamorphic apatite likely testifies that Slyudyanka high-grade metamorphism was dry, involving very little fluid. Yttrium and Ho usually fractionate in a hydrothermal environment [9]. Thus, it is surprising that hydrothermal–metasomatic apatite has Y/Ho ratios close to those of the terrigenous rocks. This example shows that the remaining chondritic Y/Ho ratio in apatite is not a universal fingerprint of hydrothermal origin. For apatite of silicate–carbonate rocks, there was a saline fluid that was different from seawater.

Figure 7.

Y/Ho vs. Eu* () and Y/Ho vs. Sm/Yb diagrams for different types of Slyudyanka apatite. The data were compared with the reference values for phosphorites [39], terrigenous protolith sediments of the Slyudyanka complex [37], modern river water [14], and modern seawater [41].

5. Conclusions

Three genetically distinct apatite groups from the Slyudyanka complex have been geochemically defined using TXRF and validated by ICP-MS, supported by multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, k-means). This classification provides a diagnostic fingerprinting framework for apatite in high-grade metamorphic terrains. (1) Hydrothermal–metasomatic apatite is identified by high Sr, Th, and As, and a chondritic Y/Ho ratio. (2) Massive metamorphic apatite from silicate–carbonate rocks is distinguished by extreme REE enrichment. (3) Metamorphic veinlet apatite from metaphosphorites is uniquely characterized by high U and Pb, low REEs, Sr, and Th, and a suprachondritic Y/Ho ratio. The key scientific advance is the demonstration that the suprachondritic Y/Ho signature—a hallmark of modern seawater—is preserved through granulite facies metamorphism. This finding is significant because it shows that the Y/Ho ratio in metamorphic apatite can act as a robust tracer of its sedimentary protolith. The anomaly is not “borrowed” but inherited; the metamorphic apatite retains the Y/Ho fractionation signature acquired by its marine sedimentary precursor (phosphorite) prior to metamorphism. Therefore, our work confirms the Y/Ho ratio’s utility as a powerful and resilient tool for reconstructing sedimentary provenance and paleoenvironments from detrital or metamorphic apatite.

The diagnostic geochemical framework established here has direct application in mineral exploration, enabling the efficient identification of apatite types with high REE potential. Furthermore, the validation of TXRF presents a practical, cost-effective analytical strategy for provenance studies and deposit characterization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.M. and A.V.I.; methodology, A.S.M.; investigation, A.N.Z.; resources, L.Z.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.M.; writing—review and editing, A.V.I., L.Z.R. and A.N.Z.; visualization, A.S.M.; supervision, A.V.I.; funding acquisition, A.V.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation № 25-77-30006, https://rscf.ru/project/25-77-30006/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data obtained are available via the author’s contacts.

Acknowledgments

The research was performed using the equipment of the «Geodynamics and Geochronology» Center at the Institute of the Earth’s Crust SB RAS. During the preparation of this work, the authors used DeepSeek V3.2 in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TXRF | Total reflection X-ray fluorescence |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| CA | Cluster analysis |

| REE | Rare earth element |

| CHARAC | CHArge-and-RAdius-Controlled |

| LA | Laser ablation |

| CAOB | Central Asian orogenic belt |

| ID-TIMS | Isotope dilution thermal ionization mass spectrometry |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PAAS | Post-Archean Australian Shale |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

References

- Almada-Gutiérrez, V.; Noury, M.; Calmus, T.; Cogné, N.; Barrera-Moreno, E.; Poujol, M. Processes Controlling Magma Fertility at Buenavista Del Cobre Porphyry Copper Deposit (Cananea, México): A New Petrogenetic Model Based on Zircon U-Pb Dating and Apatite Geochemistry. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 175, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrylov, N.; Hovakimyan, S.; Meliksetian, K.B.; Veress, E.; Bergemann, C.A.; Hambaryan, K.; Vardanyan, A.; Navasardyan, G.; Korneeva, A.; Kamenetsky, V.S.; et al. The Role of Evaporite in Iron Oxide-Apatite Ore Deposit Formation: Constraints of the Late Miocene Abovyan Deposit, Armenia. Lithos 2025, 508, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Zhang, B.; Friehauf, K.; Wang, H.; Feng, C.; Dick, J.M.; Yu, M. Apatite as a Record of Ore-Forming Processes: Magmatic-Hydrothermal Evolution of the Hutouya Cu–Fe–Pb–Zn Ore District in the Qiman Tagh Metallogenic Belt, NW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 154, 105343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Cai, D.; Dong, X.; Yu, Q. Application of Detrital Apatite U-Pb Geochronology and Trace Elements for Provenance Analysis, Insights from a Study on the Yarlung River Sand. J. Earth Sci. 2024, 35, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Fang, X.; Qi, H.; Yin, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, B. Geochemical Study of Detrital Apatite in Sediment from the Southern Okinawa Trough: New Insights into Sediment Provenance. Minerals 2019, 9, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogarko, L. Chemical Composition and Petrogenetic Implications of Apatite in the Khibiny Apatite-Nepheline Deposits (Kola Peninsula). Minerals 2018, 8, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, G.; Chew, D.; Kenny, G.; Henrichs, I.; Mulligan, D. The Trace Element Composition of Apatite and Its Application to Detrital Provenance Studies. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 201, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Algeo, T.J.; Cao, L.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Li, Z. Diagenetic Uptake of Rare Earth Elements by Conodont Apatite. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016, 458, 176–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M. Controls on the Fractionation of Isovalent Trace Elements in Magmatic and Aqueous Systems: Evidence from Y/Ho, Zr/Hf, and Lanthanide Tetrad Effect. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1996, 123, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M.; Dulski, P. Comparing Yttrium and Rare Earths in Hydrothermal Fluids from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge: Implications for Y and REE Behaviour During Near-Vent Mixing and for the Y/Ho Ratio of Proterozoic Seawater. Chem. Geol. 1999, 155, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Cao, X.; Fan, H.; Xiao, J.; Xia, Y.; Zeng, M. Geochemistry of Apatite Individuals in Zhijin Phosphorites, South China: Insight into the REY Sources and Diagenetic Enrichment. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 150, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Rasskazov, S.V.; Chebykin, E.P.; Markova, M.E.; Saranina, E.V. Y/Ho Ratios in the Late Cenozoic Basalts from the Eastern Tuva, Russia: An ICP-MS Study with Enhanced Data Quality. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 2000, 24, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M.; Dulski, P. Comparative study of yttrium and rare-earth element behaviours in fluorine-rich hydrothermal fluids. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1995, 119, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, Y.; Zhang, J.; Amakawa, H. The Fractionation between Y and Ho in the Marine Environment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1997, 148, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-N.; Pan, J.-Y.; Lehmann, B.; Li, J.-X.; Yin, S.; Ouyang, Y.-P.; Wu, B.; Fu, J.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Diagnostic REE Patterns of Magmatic and Hydrothermal Apatite in the Zhuxi Tungsten Skarn Deposit, China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 252, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Xu, C.; Song, W.; Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, M.; Wei, C. REE Mineralization in the Bayan Obo Deposit, China: Evidence from Mineral Paragenesis. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 91, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-N.; Pan, J.-Y.; Lehmann, B.; Li, J.-X.; Yin, S.; Ouyang, Y.-P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, F.-J.; Fu, J.-L.; Wu, B. Geochemical Composition of Apatite from the Zhuxi Tungsten Granite and the Zhenzhushan Granite Porphyry in the Jiangnan Porphyry-Skarn Tungsten Belt, China. Geochemistry 2023, 83, 126010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.-J.; Zhou, Q.-F.; Qin, K.-Z.; Tang, D.-M.; Evans, N.J. The Tetrad Effect and Geochemistry of Apatite from the Altay Koktokay No. 3 Pegmatite, Xinjiang, China: Implications for Pegmatite Petrogenesis. Mineral. Petrol. 2013, 107, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veksler, I.V. Liquid Immiscibility and Its Role at the Magmatic–Hydrothermal Transition: A Summary of Experimental Studies. Chem. Geol. 2004, 210, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumiste, K.; Mänd, K.; Bailey, J.; Paiste, P.; Lang, L.; Lepland, A.; Kirsimäe, K. REE+Y Uptake and Diagenesis in Recent Sedimentary Apatites. Chem. Geol. 2019, 525, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasil’ev, E.P.; Reznitskiy, L.Z.; Vishnyakov, V.N.; Nekrasova, E.A. Sludyanskiy Crystalline Complex; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1981. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, E.N.; Maltsev, A.S.; Fomina, E.N.; Sidorov, M.Y.; Zhilicheva, A.N.; Panteeva, S.V.; Kompanchenko, A.A.; Chernyavskiy, A.V. Study of the Distribution of Rare-Earth Elements and Strontium in Apatite from Rocks of the Vuoriyarvi Carbonatite Complex by Total-Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (TXRF): First Results and Prospects. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2023, 64, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, A.S.; Ivanov, A.V.; Chubarov, V.M.; Pashkova, G.V.; Panteeva, S.V.; Reznitskii, L.Z. Development and Validation of a Method for Multielement Analysis of Apatite by Total-Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. Talanta 2020, 214, 120870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltsev, A.S.; Ivanov, A.V.; Pashkova, G.V.; Marfin, A.E.; Bishaev, Y.A. New Prospects to the Multi-Elemental Analysis of Single Microcrystal of Apatite by Total-Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta Part B 2021, 184, 106281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, A.S.; Zhilicheva, A.N.; Pashkova, G.V.; Karimov, A.A. New Quantification Approaches for Total-Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis of Micro-Sized Samples: Apatite Case Study. Microchem. J. 2023, 193, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donskaya, T.V.; Sklyarov, E.V.; Gladkochub, D.P.; Mazukabzov, A.M. The Baikal Collisional Metamorphic Belt. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2000, 374, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Reznitskii, L.Z.; Fefelov, N.N.; Vasil’ev, E.P.; Zarudneva, N.V.; Nekrasova, E.A. Isotopic composition of lead in metaphosphorites and the problem of age of the Slyudyanka series (Southern CisBaikalia-Western Hamar-Daban). Lithol. Miner. Resour. 1998, 5, 484–493. [Google Scholar]

- Kotov, A.B.; Sal’nikova, E.B.; Kozakov, I.K.; Yakovleva, S.Z.; Kovach, V.P.; Reznitskii, L.Z.; Vasil’ev, E.P.; Berezhnaya, N.G. Age of Metamorphism of the Slyudyanka Crystalline Complex, Southern Baikal Area: U-Pb Geochronology of Granitoids. Petrology 1997, 5, 338–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach, V.; Salnikova, E.; Wang, K.L.; Jahn, B.M.; Chiu, H.Y.; Reznitskiy, L.; Kotov, A.; Iizuka, Y.; Chung, S.-L. Zircon Ages and Hf Isotopic Constraints on Sources of Clastic Metasediments of the Slyudyansky High-Grade Complex, South-Eastern Siberia: Implication for Continental Growth and Evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 62, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salnikova, E.B.; Sergeev, S.A.; Kotov, A.B.; Yakovleva, S.Z.; Steiger, R.H.; Reznitskiy, L.Z.; Vasil’ev, E.P. U-Pb Zircon Dating of Granulite Metamorphism in the Sludyanskiy Complex, Eastern Siberia. Gondwana Res. 1998, 1, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, I.S.; Rasskazov, S.V.; Ivanov, A.V.; Reznitskii, L.Z.; Brandt, S.B. Radiogenic Argon Distribution Within a Mineral Grain: Implications for Dating of Hydrothermal Mineral-Forming Event in Sludyanka Complex, Siberia, Russia. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 2006, 42, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteeva, S.V.; Gladkochoub, D.P.; Donskaya, T.V.; Markova, V.V.; Sandimirova, G.P. Determination of 24 Trace Elements in Felsic Rocks by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry after Lithium Metaborate Fusion. Spectrochim. Acta Part B 2003, 58, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.M.R.; Huang, X.-W.; Meng, Y.-M.; Xie, H.; Qi, L. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Trace Elements in Apatite: Discrimination of Apatite with Different Origins. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 153, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousova, E.; Griffin, W.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Fisher, N. Igneous Zircon: Trace Element Composition as an Indicator of Source Rock Type. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2002, 143, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, O.M.; Jackson, S.; Miller, W.G.R.; St-Onge, M.R.; Rayner, N. Quantitative elemental mapping of granulite-facies monazite: Textural insights and implications for petrochronology. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2020, 38, 853–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundy, J.D.; Wood, B.J. Crystal-chemical controls on the partitioning of Sr and Ba between plagioclase feldspar, silicate melts, and hydrothermal solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnik, S.I.; Reznitsky, L.Z.; Letnikova, E.F.; Proshenkin, A.I. New Data about Age and Geodynamic Nature of Hamsara Terrane. Geodyn. Tectonophys. 2017, 8, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Nozaki, Y. Rare Earth Elements and Yttrium in Seawater: ICP-MS Determinations in the East Caroline, Coral Sea, and South Fiji Basins of the Western South Pacific Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 4631–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsbo, P.; McLaughlin, P.I.; Breit, G.N.; du Bray, E.A.; Koenig, A.E. Rare Earth Elements in Sedimentary Phosphate Deposits: Solution to the Global REE Crisis? Gondwana Res. 2015, 27, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatsky, V.S.; Kozmenko, O.A.; Sobolev, N.V. Behaviour of rare-earth elements during high-pressure metamorphism. Lithos 1990, 25, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shi, Y.; Yin, J.; Lai, J. Recent Advances for Seawater Hydrogen Evolution. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).