Abstract

With the increasing harsh drilling environments encountered more frequently than ever before, developing environmentally benign and multifunctional additives is essential to formulate high performance drilling fluids. Herein, hydrothermal carbon/bentonite composites (HCBCs) were prepared by a hydrothermal carbonization reaction using soluble starch and sodium bentonite as raw materials. A systematic investigation was conducted into the effects of HCBC concentration on the rheological, filtration, and lubricating characteristics of xanthan gum, modified starch, and high-temperature polymer slurries. These properties were evaluated before and after exposure to hot rolling at different temperatures. The hydroxyl radical scavenging properties of HCBC were evaluated. Observation showed plentiful micro- and nano-sized carbon spheres deposited on the bentonite particles, endowing the bentonite with better dispersion. HCBCs could maintain stability of the water-based drilling fluids’ rheological profile, decrease filtration loss, and improve the lubrication with relatively low concentrations. The excellent properties were attributed to the highly efficient scavenging of free radicals and the stabilization of bentonite particle dispersion.

1. Introduction

With the increasing demand on resources, complex formations such as deep and ultradeep reservoirs, unconventional shale oil and shale gas, and geothermal reservoirs are more frequently encountered than ever before. To address these needs, a new generation of high-performance water-based drilling fluid is required—one that delivers better hole cleaning, enhanced wellbore stability, stable rheology, and low filtration under high-temperature conditions, reflecting the performance attributes and benefits of oil-based drilling fluids [1,2].

Water-based drilling fluid typically contains bentonite and polymers to impart the desired rheological and filtration properties [3]. The main component of bentonite is montmorillonite. Montmorillonite has a 2:1 layered crystal structure, composed of an aluminum–oxygen octahedral sheet sandwiched between two silicon–oxygen tetrahedral sheets, and contains exchangeable cations (such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, etc.). Many unit cells are stacked over each other and form layered structures [4]. Due to the isomorphic replacement of cations within the structure, the crystal surface of montmorillonite is negatively charged. Additionally, the fracturing of Al-O and Si-O result in the electrical properties of end surfaces [5]. When dispersed in an aqueous environment, house of card structures are formed by montmorillonite particles via edge-face interactions. The colloidal behavior of bentonite clay is governed by several factors including surface charge nature, cation exchange capacity (CEC), concentration, particle size and shape, and density [6]. The dispersion of clay particles is a primary cause of water-based drilling fluid instability under high-temperature conditions [7]. A previous study indicated that bentonite tends to flocculate at temperatures above 121 °C [8].

The colloidal stability of a bentonite dispersion can be improved by modifying its surface charge or by providing a steric barrier [3]. Various polymers have been employed during the past decades for different purposes. By adsorbing onto bentonite surfaces, polymers confer effective steric stabilization, preventing aggregation of the dispersed particles. Therefore, the rheology and filtration properties are improved. In addition, polymers can be used as lubricants, emulsifiers, and drag reducers, and are multi-functional [9]. In general, there are natural polymer derivatives and synthetic polymers. When the temperature exceeds 150 °C, biopolymers undergo degradation through mechanisms including thermo-oxidative degradation, hydrolysis, and fragmentation, resulting in complete loss of function [10]. In terms of synthetic polymers, the carbon–carbon backbones provide improved thermal stability; however, thermal degradation still occurs due to oxidation and side-chain hydrolysis [1]. Once the polymers degrade, the colloidal stability of the bentonite dispersion would rapidly be lost. Therefore, developing new additives to improve the colloidal stability of bentonite dispersion under elevated temperatures is important and also a challenging task.

Apart from designing high-temperature-resistant polymers, such as star polymers, comb polymers, and dendritic polymers, combining the advantages of inorganic materials and organic materials to form a composite is also a desirable method. For example, an organic–inorganic composite for high-temperature-, high-salt-resistant water-based drilling fluids was prepared by copolymerizing acrylamide (AM), 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonic acid (AMPS), diallydimethylammonium chloride (DMDAAC), and 4-acryloylmorpholine (ACMO) with laponite via aqueous radical polymerization. The water-based drilling fluid containing 2 wt% composite maintained excellent rheology and filtration properties, even after hot rolling at 180 °C and contamination with 15 wt% NaCl [11]. In another study, Ahmed et al. prepared a SiO2/g-C3N4 hybrid and revealed that the hybrid nanoparticles can improve the thermal stability of drilling fluid and reduce the filtration both before and after hot rolling at 225 °F [12]. A zwitterionic silica-based hybrid nanomaterial (ZSHNM) was designed with a dual-functional structure: a silicate core for thermal stability and a zwitterionic shell to improve filtration by complexing with cations and suppressing bentonite aggregation. The addition of 2 wt% ZSHNM enabled the water-based drilling fluid to maintain extraordinary filtration loss properties after being thermally aged at 240 °C [13].

Due to exceptional chemical, physical, mechanical, and thermal attributes, carbon nanomaterials have been paid increasing attention to drastically improve the rheology, filtration, lubrication, and inhibition of drilling fluids [12,14,15,16]. When bentonite and biomass are mixed together and exposed to a subcritical water, hydrothermal carbonization occurs, and a composite materials of hydrothermal carbon spheres supported on montmorillonite can be obtained. Many oxygen-containing groups including hydroxyl, carboxyl, and carbonyl groups are anchored on the surface of the composites, which improves the dispersion stability of bentonite. Due to these special properties, the composites have been widely used for adsorption [17,18,19].

Herein, hydrothermal carbon bentonite composites (HCBCs) were designed and fabricated using the low-cost materials of soluble starch and sodium bentonite as the raw materials via one-step hydrothermal carbonization. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM), and specific surface area were used to characterize the structure characteristics of HCBCs. A systematic investigation was then conducted to assess the impact of HCBCs on the water-based drilling fluid’s key properties, including rheology, filtration, and lubrication.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Sodium-based bentonite was purchased from Shengli Oilfield Boyou Mud Technology Co., Ltd., (Dongying, China), containing 60% montmorillonite, 32% quartz, and 8% potassium feldspar. Methyl violet (MV) (CAS: 8004-87-3), hydrochloric acid (CAS: 7647-01-0), soluble starch (CAS: 9005-84-9), and anhydrous ethanol (CAS: 64-17-5) are analytical grade reagents purchased from China National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., (Beijing, China). Xanthan gum (XC) was purchased from Ordos Zhongxuan Biochemical Co., Ltd., (Zibo, China). Modified starch was provided by China Oilfield Services Limited, (Beijing, China). HT, a high-temperature polymer fluid loss reducer, was provided by Chevron Philips Chemical Company, (The Woodlands, TX, USA).

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of HCBCs

The HCBC was synthesized via a hydrothermal method. Briefly, 4 g of soluble starch and 4 g of sodium bentonite were added to 80 mL of deionized water. The mixture was stirred at 10,000 rpm for 30 min and then subjected to a hydrothermal reaction in a 100 mL Teflon-lined kettle at 200 °C for 16 h. After cooling to room temperature, the product was collected by centrifugation, alternately washed three times with deionized water and absolute ethanol, dried at 80 °C for 24 h, and finally ground and passed through a 100-mesh sieve (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of hydrothermal reaction.

The functional groups on the surface of the HCBC were investigated with a NEXUS Fourier transform infrared spectrometer, (Thermo Nicolet Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). Thermal stability was evaluated by employing a TGA5500 thermogravimetric analyzer, scanning from 35 to 1000 °C at 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. The interlayer spacing of the HCBC sample was measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using an X-ray diffractometer (X’Pert PRO MPD), (PAnalytical, Almelo, Overijssel, The Netherlands). The HCBC sample was prepared as a randomly oriented specimen. The measurement was conducted under the following operating conditions: 45 kV (accelerating voltage), 40 mA (tube current), a fixed slit width of 0.76 mm, Cu-Kα radiation (wavelength λ = 0.154 nm), a scanning rate of 3.86°/min, a step size of 0.017° (2θ), and a scanning range of 3–15°. The microstructure of the HCBC was observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SU8010) (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (FEI Tecnai G2 F20), (FEI NanoPorts, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The specific surface area was tested using an automatic specific surface area analyzer (Micromeritics APSP2460), (Mcmurdik (Shanghai) Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The surface elements of the HCBC were analyzed with a high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (ESCALAB XI+), (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), using Al Kα radiation (hm = 1486.6 eV) during the test, and the binding energy was calibrated by the C1s line at 284.8 eV. The Zeta potential of the HCBC suspension was measured using a multi-angle particle size and high-sensitivity Zeta potential analyzer (Omni), (Brookhaven, New York City, NY, USA). To determine the water adsorption capacity of the HCBC, 1 g HCBC was put in a glass dish. Then the glass dish was placed in the middle position of a dryer where the bottom was filled with water. After sealing the dryer for a certain interval, the glass dish was quickly taken out and weighed. Then, the glass dish with the HCBC was put in the dryer and sealed again until the weight change, reaching a balance.

2.3. Drilling Fluid Preparation and Properties Measurement

2.3.1. Drilling Fluid Preparation

Sodium bentonite (16 g) was putted in 400 mL fresh water and mixed at 10,000 rpm for 20 min on a Hamilton Beach mixer. Then, the suspension was sealed and incubated overnight to hydrate and form a bentonite suspension. XC slurry was prepared by adding 0.8 g NaOH and 0.8 g XC into the 400 mL bentonite slurry and stirring at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The modified starch slurry and HT polymer slurry was prepared via a similar method, where the dosage of both the modified starch and the HT polymer is 4 g.

2.3.2. Drilling Fluid Hot Rolling

The prepared drilling fluid (400 mL) was placed into a stainless-steel aging cell (total volume of 500 mL) and sealed. The aging cell can withstand a maximum temperature of 300 °C and a pressure of 5 MPa (Hengtai Da Electromechanical Equipment Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China). Then the aging cell was transferred into a GW300-X high-temperature roller oven (Xusheng Petroleum Instruments Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China). The drilling fluid was hot-rolled at a specified temperature for 16 h with a rotation speed of 50 r/min.

2.3.3. Drilling Fluid Rheological Properties Measurement

The rheological parameters of the drilling fluid, including plastic viscosity (PV), yield point (YP), and apparent viscosity (AV), were measured using a ZNN-D6 rotational viscometer (Haitongda Special Instrument Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China). The rotational viscometer consists of an inner cylinder (diameter: 34.49 mm) and an outer cylinder (inner diameter: 36.83 mm), with an annular gap of 1.16 mm. It operates at six rotational speeds (3, 6, 100, 200, 300, and 600 r/min), corresponding to six shear rates (5, 10, 170, 340, 511, and 1022 s−1). The experimental procedures strictly adhered to the API standard method API RP 13B-1 (2019 edition) [20]. The sample was poured into the viscometer cup. Measurements were performed sequentially at rotational speeds of 600, 300, 200, 100, 6, and 3 r/min at room temperature. When the dial stabilized, the dial readings were recorded, and the rheological parameters were calculated using the following formulas:

AV = θ600/2 (mPa·s)

PV = θ600 − θ300 (mPa·s)

YP = AV − PV (Pa)

For the gel strength measurement, the drilling fluid sample was first stirred at 600 rpm for 10 s, followed by standing for 10 s. Subsequently, the maximum dial reading at a rotation speed of 3 rpm was recorded. Half of this value was recorded as the initial gel strength (gel 10 s). The drilling fluid sample was stirred at 600 rpm for 10 s again and allowed to rest for 10 min. Then, the maximum dial reading at 3 rpm was recorded. Half of this value was recorded as the final gel strength (gel 10 min).

2.4. Hydroxyl Free Radicals Scavenging Experiment

Under the test conditions, MV exhibits its characteristic purple color. The highly reactive hydroxyl radicals generated via the Fenton reaction cause the discoloration of methyl violet, leading to a significant decrease in the maximum absorbance value. With the increase in the dosage of free radical scavenger, the color of the methyl violet solution gradually deepens, and the absorbance increases correspondingly. Therefore, the free radical scavenging efficiency can be indirectly detected [21,22]. First, 0.001 mol/L FeSO4 solution, 2 × 10−4 mol/L MV solution, 0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl buffer, and 0.004 mol/L H2O2 solution were prepared. Then, 0.4 mL of HCBC suspension, 0.4 mL of MV solution, 0.4 mL of FeSO4 solution, 0.4 mL of H2O2 solution, and 0.4 mL of Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 3.7) were sequentially added to a beaker. The total volume of the mixture was adjusted to 4 mL with deionized water. After allowing the reaction to proceed for 5 min, the solution was transferred to a cuvette. The absorbance was measured using a UV1750 ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), and the hydroxyl radical scavenging rate was calculated based on the absorbance values obtained.

2.5. Boehm Titration Experiment

The acidic oxygen-containing functional groups on the HCBC were quantified via Boehm titration. Briefly, 0.2 g of dried HCBC was placed in a beaker and mixed with 50 mL of a 0.05 mol/L sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) solution. The mixture was magnetically stirred at 25 °C for 24 h. After the reaction, the solid was separated by filtration. A 25 mL aliquot of the filtrate was collected and titrated with a standard 0.05 mol/L HCl solution, using 2–3 drops of 0.1% methyl orange as an indicator. The titration endpoint was identified as a color change from yellow to orange, and the volume of HCl consumed was recorded as V01. A blank titration, following the same procedure but in the absence of the HCBC, was performed, and the consumed HCl volume was recorded as V1. The same procedure was repeated by replacing the NaHCO3 solution with 0.05 mol/L sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solutions, respectively. The corresponding volumes of HCl consumed were recorded as V02 and V03 for the samples, and V2 and V3 for their respective blanks.

The contents of carboxyl groups, lactone groups, and hydroxyl groups in the HCBC were calculated using the following formula.

where is concentration of standardized HCl (mol/L), and m is mass of the sample (g). The factor “2” accounts for the 25 mL aliquot taken from 50 mL filtrate. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the average values were reported to ensure reproducibility.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of HCBCs

3.1.1. FTIR

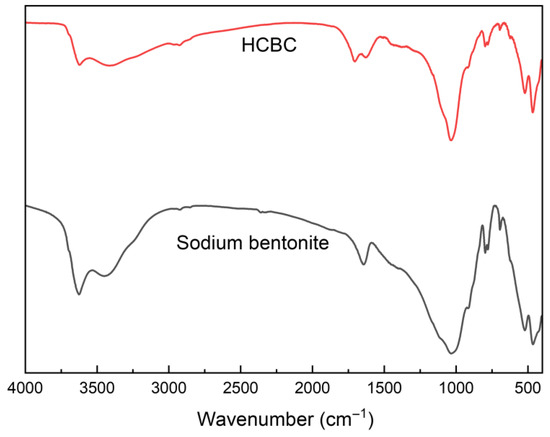

As shown in Figure 2, the infrared spectroscopy of bentonite exhibits characteristic absorption peaks at 3624 cm−1 (Al-OH stretching vibration), 3444 cm−1 (adsorbed water OH stretching vibration), 1644 cm−1 (adsorbed water -OH bending vibration), 1032 cm−1 (Si-O-Si stretching vibration), 521 cm−1 (Si-O-Al bending vibration), and 464 cm−1 (Si-O-Si bending vibration) [23]. These characteristic peaks remain after the hydrothermal carbonization reaction, and new stretching vibration peaks of C=O and C=C appear at 1704 cm−1 and 1631 cm−1, respectively. This indicates that soluble starch is deposited on the surface of bentonite, introducing oxygen-containing functional groups after hydrothermal carbonization [18].

Figure 2.

FTIR of sodium bentonite and HCBC.

3.1.2. XPS

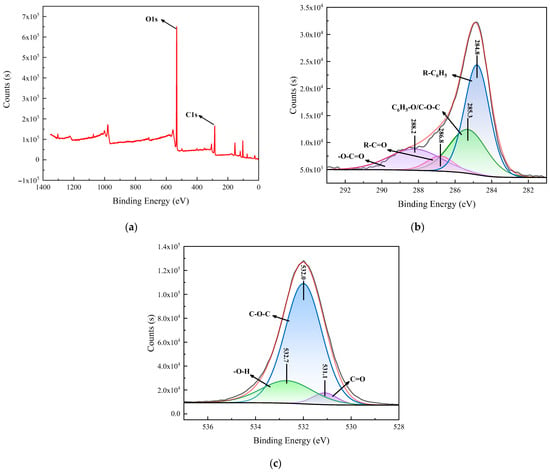

From the full-spectrum analysis of bentonite and the HCBC in Figure 3a, a C1s peak appears at a binding energy of 284.8 eV in HCBC, suggesting that the hydrothermal carbonization reaction increases the carbon content on the surface of bentonite. As shown in Figure 3b, the C1s peak is located at 284.8 eV, and its four fitted peaks at 284.8, 285.3, 286.8, and 288.2 eV correspond to aromatic groups or alkyl-substituted aromatic groups (R-C6H5), phenolic or ether groups (C6H5-O/C-O-C), carbonyl groups (R-C=O), and carboxyl, ester, or lactone groups (-O-C=O), respectively [24]. As shown in Figure 3c, the O1s peak is located at 531.7 eV, and its three fitted peaks at 531.1, 532.0, and 532.7 eV correspond to carbonyl groups (C=O), ester groups (C-O-C), and hydroxyl groups (-OH), respectively [25]. It can be seen that the surface of the composite formed after the hydrothermal carbonization of bentonite contains abundant oxygen-containing functional groups.

Figure 3.

XPS spectra of HCBC: (a) survey spectrum, (b) C1s spectrum, (c) O1s spectrum.

3.1.3. Boehm Titration

Table 1 shows the experimental results of the Boehm titration. The contents of carboxyl groups (-COOH), lactone groups (-O-CO-), and hydroxyl groups (-OH) are 0.5 mmol/g, 0.2 mmol/g, and 0.3 mmol/g, respectively, which is generally consistent with the XPS results. The Boehm titration results further confirm that the surface of the HCBC is rich in oxygen-containing functional groups.

Table 1.

Contents of carboxyl, lactone and hydroxyl groups in the HCBC.

3.1.4. XRD

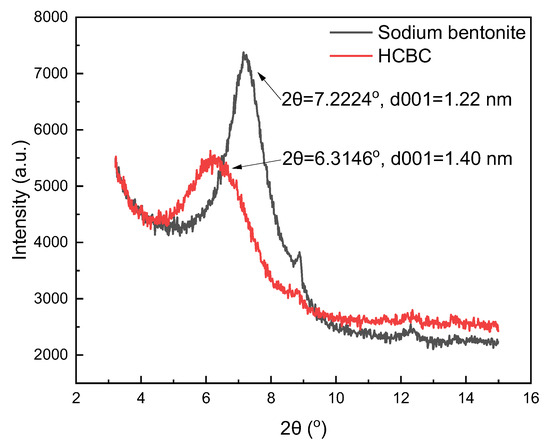

Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of bentonite and the HCBC. Compared with bentonite, no new diffraction peaks appeared in the XRD pattern of the HCBC, indicating that the basic crystal structure of bentonite was not destroyed. According to Bragg’s equation, nλ = 2dSinθ, where n is 1, the wavelength is 1.54 nm, and the θ for sodium bentonite and the HCBC is 3.6112° and 3.1573°, detected by XRD. Therefore, the calculated interlayer spacing was 1.22 nm and 1.40 nm for sodium bentonite and the HCBC, respectively. The reason for this is that water-soluble starch was adsorbed into the interlayers of montmorillonite through hydrogen bonds and other interactions. Water-soluble starch would change into carbon particles through hydrothermal carbonization under high temperatures, which could increase the interlayer spacing. Combined with SEM analysis, it can be seen that the hydrothermal carbonization reaction not only occurred on the outer surface of bentonite but also in the interlayer of bentonite.

Figure 4.

XRD of sodium bentonite and HCBC.

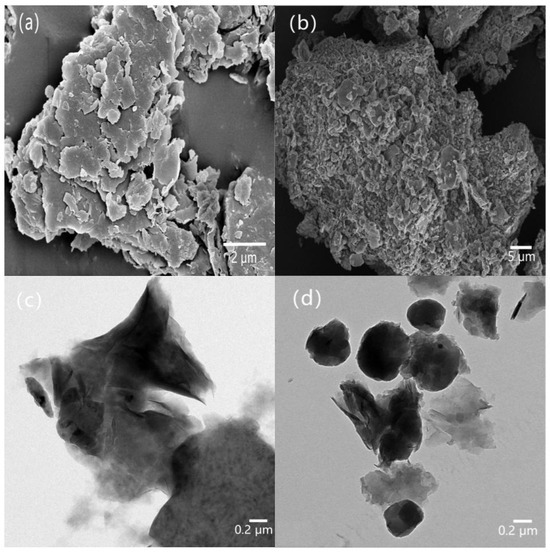

3.1.5. SEM and TEM

It can be seen from the SEM image in Figure 5a that bentonite has a typical plate-like structure. In the HCBC, in addition to retaining some plate-like structure, a large number of nearly spherical and irregular nanoparticles can also be observed, some of which are embedded between the layers of bentonite, while others are in a free deposition state. In a high-temperature hydrothermal environment, starch and other sugar compounds first hydrolyze into low-molecular substances such as glucose, and then dehydrate to form intermediates such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. These intermediates undergo condensation or addition reactions to form polyfuran structures, and then undergo aromatization reactions to ultimately form hydrothermal carbon [26]. When bentonite is present, there are two main reaction pathways: a portion of the soluble starch is adsorbed on the surface of bentonite under the influence of hydrogen bonds and the polarity of the bentonite surface, and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and other intermediates nucleate and grow on the active sites of the bentonite surface to form carbon particles. The growth of these carbon particles is restricted by bentonite, resulting in a smaller particle size, mainly at the nanoscale. Another portion of the soluble starch undergoes hydrothermal carbonization directly in the solution to form micrometer-sized carbon spheres, which deposit on the surface of bentonite [18]. Due to the different reaction pathways, the hydrothermal carbon between the layers of bentonite has a graphite-like structure, while the hydrothermal carbon on the surface of bentonite has an amorphous structure [27]. After the surface of bentonite is covered with micro–nano carbon spheres, the BET specific surface area decreases from 6.7379 m2/g to 2.8357 m2/g. It can also be seen from the TEM images in Figure 5c,d that a typical plate-like aggregation structure can be observed in the bentonite suspension, while in the HCBC suspension, not only are there a large number of nearly spherical nanoparticles deposited on the surface of the bentonite layers, but also hundreds of nanometer-sized or even micrometer-sized free particles can be observed.

Figure 5.

SEM and TEM images of HCBC and bentonite. (a) SEM image of bentonite, (b) SEM image of HCBC, (c) TEM image of bentonite, and (d) TEM image of HCBC.

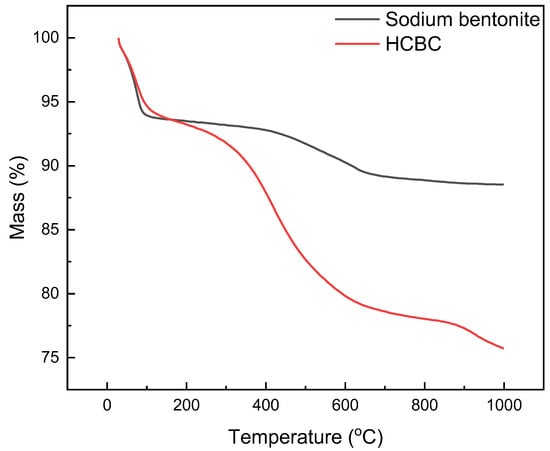

3.1.6. TGA

As shown in Figure 6, for bentonite, the mass loss between 30 and 200 °C mainly results from the removal of free water and bound water, and the mass loss between 400 and 600 °C corresponds to the dehydroxylation reaction. When the temperature rises to 1000 °C, the mass loss rate is 11.47%. For the HCBC, starch molecules enter the interlayer of bentonite and undergo hydrothermal carbonization reactions, displacing some water molecules. Within the range of 30 to 200 °C, the weight loss is lower than that of bentonite. After exceeding 350 °C, HCBC begins to lose weight rapidly, and at this time, the carbon particles loaded on the surface of bentonite start to degrade. When the temperature rises to 1000 °C, the mass loss rate is 24.28%. From this, it can be inferred that the content of hydrothermal carbon particles loaded on the surface of bentonite is approximately 12.81%.

Figure 6.

TGA curves of sodium bentonite and the HCBC.

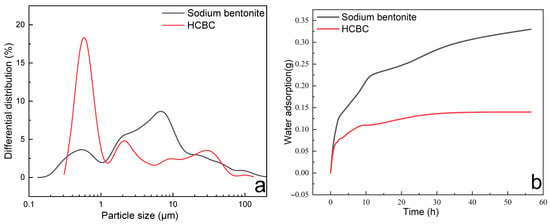

3.1.7. Particle Size Distribution and Water Adsorption

As depicted in Figure 7a, both sodium bentonite and the HCBC exhibit multimodal distribution. The average particle size of sodium bentonite and the HCBC is 5.434 μm and 0.811 μm, respectively, indicating that after modification, the dispersion of bentonite particles is significantly improved. This could also be verified by the zeta potential measurement results. The zeta potential of bentonite being −38.41 mV changes to −45.51 mV for the HCBC. As shown in Figure 7b, for bentonite, the weight increases rapidly at the initial 2 h, followed by a gradual increase. After about 56.5 h, the weight increase is 33%, which corresponds to the amount of water adsorption. In terms of the HCBC, the weight increases rapidly at the initial 1.3 h, then increases with a much slower rate. After 56.5 h, the weight increases only by 14%, much lower than that of bentonite. This indicates that the water affinity is decreased to some degree after modification with the hydrothermal carbon clusters on the bentonite surface.

Figure 7.

Particle size distribution (a) and water adsorption amount (b) as a function of time for bentonite and HCBC.

3.2. Properties Evaluation

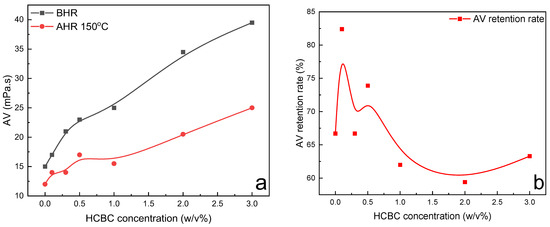

3.2.1. Xanthan Slurries

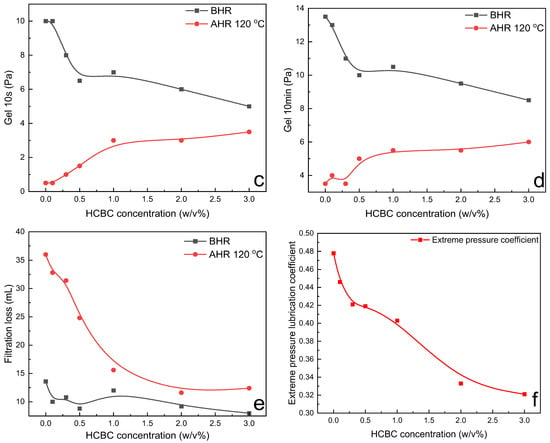

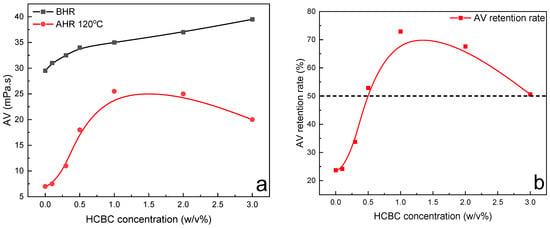

The variation in rheological parameters including PV, YP, gel strength, filtration loss, and extreme pressure lubrication coefficient of XC slurries as a function of HCBC concentration before and after hot rolling (AHR) at 120 °C is presented in Figure 8. Before hot rolling (BHR), the rheological parameters such as PV, YP, and filtration loss changed slightly with the increasing concentration of HCBC, indicating that the HCBC imposes little influence on the rheological and filtration properties of XC slurries. After hot rolling at 120 °C, the degradation of XC resulted in remarkable decrease in PV and YP for the control slurry, while the addition of HCBC was able to restore the PV to that of before hot rolling, and increase the YP to some extent. Meanwhile, both the filtration loss and lubrication coefficient decreased obviously with the addition of HCBC. A reduction of 55.4% and 30.3% was observed, respectively, for the filtration loss and lubrication coefficient at 2 w/v% HCBC. In terms of gel strength, as shown in Figure 8c,d, both the gel 10s and gel 10 min decreased with the increase in HCBC concentration before hot rolling. After hot rolling, these two parameters increased progressively with the increase in HCBC concentration, indicating the improved suspending capacity. As depicted in Figure 9, after hot rolling, the AV retention rate was only 23.7% for the XC slurries, indicating the severe degradation of XC. However, it recovered to over 50% when the concentration of HCBC was above 0.5%. Howard et al. (2015) stated that the fluids maintaining 50% of their viscosity after hot rolling for 16 h can be defined to have thermal stability [28]. Therefore, the addition of HCBC improves the thermal stability of XC slurries effectively. Overall, the XC slurries with HCBC maintain stable viscosity, low filtration loss, and low lubrication coefficient after hot rolling.

Figure 8.

Variation in rheological, filtration, and lubrication properties of XC slurry as a function of HCBC concentration before and after hot rolling at 120 °C: (a) PV, (b) YP, (c) Gel 10s, (d) Gel 10min, (e) filtration loss, (f) extreme pressure lubrication coefficient.

Figure 9.

Variation in AV (a) and AV retention rate (b) as a function of HCBC concentration for the XC slurry after hot rolling at 120 °C.

3.2.2. Modified Starch Slurries

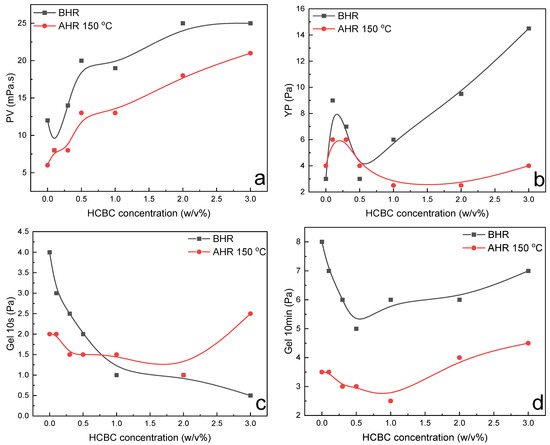

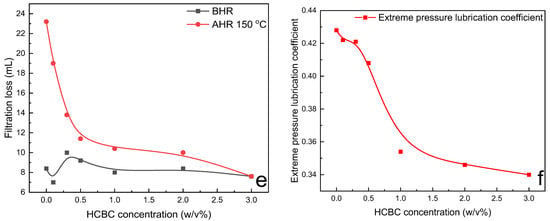

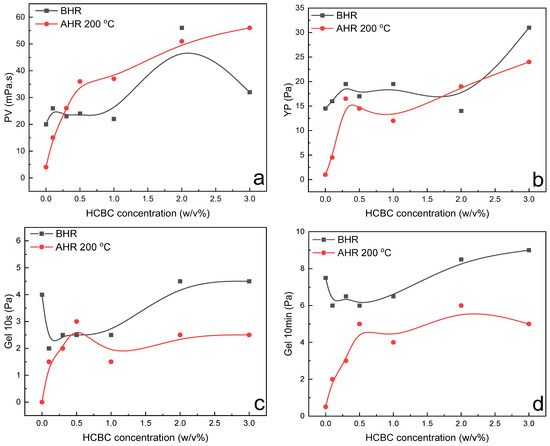

The variation in rheological parameters including PV, YP, gel strength, filtration loss, and extreme pressure lubrication coefficient of modified starch slurries as a function of HCBC concentration before and after hot rolling at 150 °C is presented in Figure 10. Regarding the rheological parameters, the PV exhibited an increasing trend with the addition of HCBC before hot rolling and after hot rolling, whereas the YP generally increased before hot rolling but decreased slightly after hot rolling with the addition of HCBC. The gel 10s decreased gradually, and gel 10 min exhibited an initial decrease and then a slight increase behavior with the increase in HCBC concentration before hot rolling. After hot rolling, both the gel 10 s and gel 10 min exhibited an increase after the incorporation of HCBC, indicating enhanced suspending capacity. In terms of filtration and lubrication, they exhibited a similar pattern of change as XC slurries. When 3 w/v% HCBC was employed, the filtration loss and lubrication coefficient was reduced by 67.2% and 20.5%, respectively. For the AV retention rate, as shown in Figure 11, it increased at a low concentration of HCBC, while decreasing slightly at relatively high concentration of HCBC. Nevertheless, for all the concentrations of HCBC, the AV retention rate is higher than 50%, indicating thermal stability after thermal treatment.

Figure 10.

Variation in rheological, filtration, and lubrication properties of modified starch slurry as a function of HCBC concentration before and after hot rolling at 150 °C: (a) PV, (b) YP, (c) Gel 10s, (d) Gel 10min, (e) filtration loss, (f) extreme pressure coefficient.

Figure 11.

Variation in AV (a) and AV retention rate (b) as a function of HCBC concentration for the modified starch slurry after hot rolling at 150 °C.

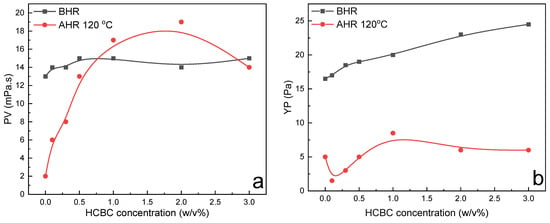

3.2.3. HT Polymer Slurries

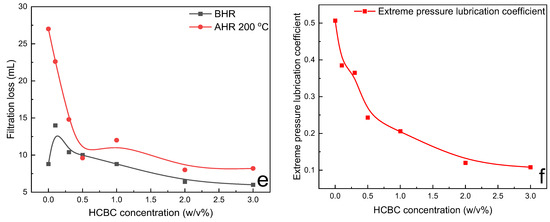

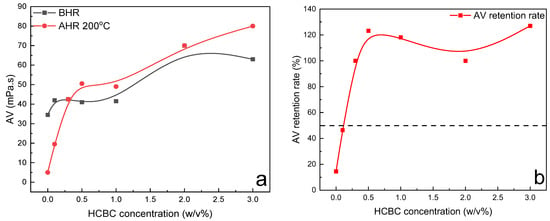

The variation in rheological parameters including PV, YP and gel strength, filtration loss, and extreme pressure lubrication coefficient of HT polymer slurries as a function of HCBC concentration before and after hot rolling at 200 °C is presented in Figure 12. Since HCBC are microparticles, the incorporation of HCBC increases the friction between the liquid and solid phase, as well as the friction between solid and solid phase, resulting in the increase in PV to some extent before hot rolling. The oxygen-containing functional groups in HCBC probably promoted the formation of network structures among bentonite particles, HT polymers, and HCBC through hydrogen bonding. The YP increased obviously at 3.0 w/v% HCBC before hot rolling. After hot rolling at 200 °C, both PV and YP for the control slurries decreased to near zero, indicating that the slurries suffering from severe degradation under such harsh conditions. However, the addition of HCBC with much low concentration of 0.3 w/v% can maintain the PV and YP value approaching to that of before hot rolling. For gel strength, both gel 10 s and gel 10 min decreased at low concentration of HCBC and then increased to some degree before hot rolling. After hot rolling, they all exhibited a similar behavior that increased obviously at low concentration of HCBC and then varied slightly. Overall, the addition of HCBC could improve the gel structure of the slurries after hot rolling. As shown in Figure 13, the AV retention rate was even higher than 100% when the concentration of HCBC above 0.5 w/v%, indicating excellent thermal stability effect. For filtration loss and lubrication, the addition of 2 w/v% HCBC resulted in decrease by 70.4% and 77.5%, respectively, after hot rolling at 200 °C.

Figure 12.

Variation in rheological, filtration, and lubrication properties of HT polymer slurry as a function of HCBC concentration before and after hot rolling at 200 °C: (a) PV, (b) YP, (c) Gel 10s, (d) Gel 10min, (e) filtration loss, (f) extreme pressure coefficient.

Figure 13.

Variation in AV (a) and AV retention rate (b) as a function of HCBC concentration for the HT polymer slurry after hot rolling at 200 °C.

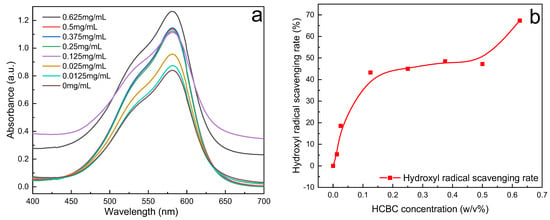

3.2.4. Free Radical Scavenging

The variation in hydroxyl radical scavenging rate with HCBC concentration was calculated based on the change in maximum absorbance, as shown in Figure 14. At an extremely low concentration of 0.025 mg/mL, HCBC achieves a scavenging rate of 5.39%. Thereafter, the scavenging rate generally shows an upward trend with increasing concentration. When the concentration reaches 0.625 mg/mL, the scavenging rate can reach 67.35%, indicating that HCBC effectively blocks the reaction between hydroxyl radicals and methyl violet, and that it exhibits a scavenging effect on hydroxyl radicals. After the radicals generated through chain initiation are scavenged, the radical chain propagation reaction is interrupted, preventing subsequent oxidation reactions. This can effectively avoid the attack and damage of free radicals on polymer molecular chains.

Figure 14.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging as a function of HCBC concentration: (a) absorbance; (b) hydroxyl radical scavenging rate.

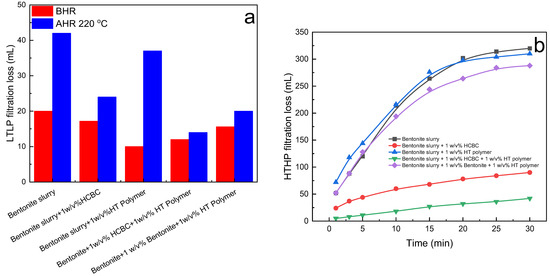

3.2.5. Filtration Loss

The LTLP filtration loss and HTHP filtration loss of bentonite slurry treated with various filtration reducers are illustrated in Figure 15. Before hot rolling, the addition of HCBC decreased the LTLP filtration loss from 20 mL to 17.2 mL, exhibiting a limited effectiveness, whereas the HT polymer could decrease the filtration loss from 20 mL to 10 mL, better than HCBC. After hot rolling at 220 °C, due to the degradation of the HT polymer, the fluid with the HT polymer lost filtration control, with a high filtration loss of 37 mL. The combination of the HCBC and the HT polymer exhibited much lower filtration loss, indicating a synergistic effect. As shown in Figure 13b, after hot rolling, the dehydration of bentonite resulted in the aggregation of clay particles, which corresponded to the quite high HTHP (200 °C/3.5 MPa) filtration loss of 640 mL. The degradation of the HT polymer also caused uncontrollable HTHP filtration loss, and the HTHP filtration loss reached 620 mL. The combination of 1 w/v% HT polymer and 1 w/v% bentonite decreased the HTHP filtration loss to a very limited degree. However, the HTHP filtration loss was significantly decreased to 180 mL in the presence of 1 w/v% HCBC, and further decreased to 84 mL when 1 w/v% HCBC and 1 w/v% HT polymer were both used. Both the LTLP filtration loss and the HTHP filtration loss indicated that the HCBC can effectively decrease the filtration loss of bentonite slurry and has a synergistic effect with HT polymer.

Figure 15.

The LTLP filtration loss (a) and HTHP filtration loss (b) of bentonite slurry in the presence of various filtration reducers before and after hot rolling at 220 °C.

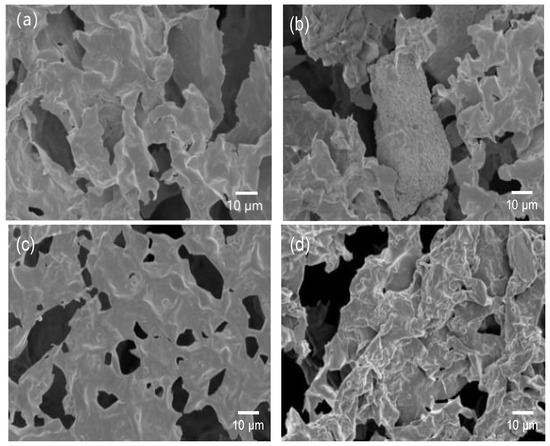

The SEM images of filter cake formed by bentonite slurry with and without HCBC before and after hot rolling are shown in Figure 16. Before hot rolling, the clay particles are fully hydrated and dispersed, and the particles are mainly connected by end to surface to form a typical honeycomb structure. Due to the thick hydration film, the edges of clay particles are relatively rounded after rapid freezing and freeze-drying with liquid nitrogen. After hot rolling at 220 °C, as shown in Figure 16b, due to the high-temperature dehydration effect, the repulsive force of the hydration film decreases, and the clay particles form larger sheet-like structures through surface to surface connections. The filtration channels significantly increase and the filtration loss significantly increases.

Figure 16.

SEM images of filter cake: (a) bentonite slurry before hot rolling, (b) bentonite slurry after hot rolling at 220 °C, (c) bentonite slurry in the presence of HCBC before hot rolling, (d) bentonite slurry in the presence of HCBC after hot rolling at 220 °C.

After adding HCBCs, as shown in Figure 16c, the oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of HCBCs interact with clay particles before hot rolling, causing the clay particles to stick together and form sheets, which to some extent reduces the filtration area. As shown in Figure 16d, after hot rolling at 220 °C, the clay particles in the filter cake with added HCBCs also underwent agglomeration due to high-temperature dehydration. However, HCBCs enhanced the repulsive force between clay particles, and the agglomeration effect was significantly weakened compared to the filter cake without HCBCs. In addition, regardless of whether hot rolling has been carried out or not, a large number of micro and nano carbon spheres can be observed in the filter cake after adding HCBCs, which is beneficial for improving particle stacking efficiency and forming a dense mud cake.

3.3. High Temperature Stabilizing and Filtration Control Mechanism

When starch is dissolved in water under subcritical conditions, it first hydrolyze into low molecular weight mono saccharides such as glucose, and then dehydrate to form intermediates such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. The intermediates undergo condensation or addition reactions to form polyfuran structures, which are then subjected to aromatization reactions to ultimately generate hydrothermal carbon.

When bentonite is present, there are two main reaction pathways: a portion of soluble starch is adsorbed on the surface of bentonite under hydrogen bonding and polarity induction. Intermediates such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural nucleate and grow at the active sties on the surface of bentonite to form carbon particles. The growth of this part of carbon particles is limited by bentonite; therefore, their particle size is relatively small, mainly at the nanoscale. For the other part of soluble starch, which is dissolved in the aqueous solution, it can directly form micrometer-sized carbon spheres through hydrothermal carbonization. These carbon spheres can deposit on the surface of bentonite.

The anchoring or depositing of hydrothermal carbon spheres on the surface of bentonite brings abundant oxygen-containing groups such as hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups. On the one hand, the hydroxyl groups tend to act as H-atom donors to unstable free radical molecules [29]. On the other hand, compounds with long conjugated C=C chains are usually great free radical scavengers. For graphene, carbon nanotubes, and fullerene, the radical addition to the sp2 carbon network plays an important role [30]. Similarly, there are plentiful sp2-conjugated C=C chains in the core of hydrothermal carbon spheres. The spin across the conjugated graphemic backbone is delocalized, which forms free radical adducts and results in the decrease in free radical quantities [31,32]. The combination of hydrogen donating by surface hydroxyl groups and formation adducts by the core sp2 C=C carbon contributes to the free scavenging effect, which in turn prevents the thermal oxidative degradation of polymers. Therefore, the thermal stability of water-based drilling fluid is significantly enhanced.

Regarding filtration loss, due to the abundant oxygen groups on the HCBC, on the one hand, the addition of HCBC promotes the dispersibility of clay particles. On the other hand, the partially free nano carbon spheres in the HCBC increase the content of submicron particles in the system. Therefore, the addition of HCBC leads to a decrease in the average particle size of the suspension, and forms a reasonable gradation with bentonite particles, making it easier to form a dense filter cake and thus reducing filtration loss. At the same time, clay particles also undergo agglomeration due to high-temperature dehydration, but the HCBC enhances the repulsion between clay particles, and the agglomeration is significantly weakened. In addition, regardless of before and after hot rolling, a large number of micro and nano carbon spheres are observed to be filled into the filter cake after adding the HCBC, which is beneficial for improving particle packing efficiency and forming a dense filter cake.

4. Conclusions

In this study, hydrothermal carbon/bentonite composites (HCBCs) were prepared by a hydrothermal carbonization reaction using soluble starch and sodium bentonite as raw materials. The interlayer spacing of bentonite increased from 1.22 nm to 1.40 nm after the hydrothermal carbonization reaction. There were plentiful micro- and nano-sized carbon spheres deposited on the surface of bentonite, and the oxygenated groups on the carbon sphere surface improved the dispersion stability of bentonite particles.

HCBCs exhibit limited effect on the rheology of xanthan slurries, modified starch slurries, and high-temperature-resistant polymer slurries. However, after dynamical thermal aging, the presence of HCBCs could effectively improve the apparent viscosity retention, reduce the filtration loss, and enhance the lubrication of the slurries.

The high efficiency in free radical scavenging contributes to the excellent thermal stability of water-based drilling fluids. The surface of HCBCs has abundant oxygen-containing functional groups, which improve the dispersion stability of clay particles at ultra-high temperatures through electrostatic repulsion and other mechanisms. The relatively small particle size of HCBC and the formation of free micro nano carbon spheres through hydrothermal reactions are beneficial for improving the solid-phase particle size distribution of drilling fluids and enhancing the quality of mud cakes. The above comprehensive effects mean that HCBCs exhibit excellent ultra-high temperature filtration performance.

The raw materials used in the preparation of HCBC are widely sourced, and the preparation process is green and environmentally friendly. Multifunctional HCBCs show great potential in developing high-performance water-based drilling fluids. This study also opens up a new way to design and develop multifunctional and environmentally friendly additives for drilling fluids.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and D.L.; methodology, H.Z. and Y.Z.; validation, C.C. and Y.Z.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, H.Z. and X.W.; data curation, H.Z. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science and Technology Major Projects, grant number 2025ZD1401301, the Open Fund for Sinopec’s Key Laboratory of Ultra-Deep Well Drilling Engineering and Technology, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number No. 52174013.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yubin Zhang, Daqi Li, and Xianguang Wang was employed by SINOPEC Research Institute of Petroleum Engineering Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AV | Apparent viscosity |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy |

| HCBCs | Hydrothermal carbon/bentonite composites |

| HT | High-temperature |

| HTHP | High-temperature and high-pressure |

| LTLP | Low-temperature and low-pressure |

| MV | Methyl violet |

| PV | Plastic viscosity |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscope |

| TGA | Thermogravimetry Analysis |

| XC | Xanthan gum |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| YP | Yield point |

| BHR | Before hot rolling |

| AHR | After hot rolling |

References

- Galindo, K.A.; Zha, W.; Zhou, H.; Deville, J.P. Clay-free high performance water-based drilling fluid for extreme high temperature wells. SPE-173017-MS. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference and Exhibition, London, UK, 17–19 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani, M.A.; Popplestone, A.; Guarneri, A.; Carminati, S. Water-based drilling fluid for HT/HP applications. SPE-105485-MS. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry, Houston, TX, USA, 28 February–2 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rabaioli, M.R.; Miano, F.; Lockhart, T.P.; Burrafato, G. Physical/chemical studies on the surface interactions of bentonite with polymeric dispersing agents. SPE-25179-MS. In Proceedings of the SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–5 March 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, H.M.; Kamal, M.S.; Al-Harthi, M.A. Effect of thermal aging and electrolyte on bentonite dispersions: Rheology and morphological properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 269, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, Z.; Han, F. Effects of pH on the gel properties of montmorillonite, palygorskite and montmorillonite-palygorskite composite clay. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 190, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormán, J. Chemistry and field practice of high-temperature drilling fluids in Hungary. SPE-21940-MS. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 March 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Elward-Berry, J.; Darby, J.B. Rheologically sable, nontoxic, high-temperature, water-based drilling fluid. SPE Drill. Complet. 1997, 12, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilch, H.E.; Otto, M.J.; Pye, D.S. The evolution of geothermal drilling fluid in the imperial valley. SPE 21786. In Proceedings of the Western Regional Meeting, Long Beach, CA, USA, 20–22 March 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, J.; Miska, N.; Takach, N.; Yu, M.; Saasen, A. The effect of elongational flow through the drill bit on the rheology of polymeric drilling fluids. SPE-99107-MS. In Proceedings of the IADC/SPE Drilling Conference, Miami, FL, USA, 21–23 February 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Deville, J.P.; Davis, C.L. Novel thermally stable high-density brine-based drill-in fluids for HP/HT applications. SPE-172659-MS. In Proceedings of the SPE Middle East Oil & Gas Show and Conference, Manama, Bahrain, 8–11 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Qu, Y.; Wang, P.; Huang, H.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Z. Laponite-polymer composite as a rheology modifier and filtration loss reducer for water-based drilling fluids at high temperature. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 655, 130261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Pervaiz, E.; Abdullah, U.; Noor, T. Optimization of water based drilling fluid properties with the SiO2/g-C3N4 hybrid. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 15052–15064. [Google Scholar]

- Ao, T.; Yang, L.; Xie, C.; Jiang, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; He, X. Zwitterionic silica-based hybrid nanoparticles for filtration control in oil drilling conditions. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 11052–11062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, R.; Jan, B.M.; Vejpravova, J. Towards recent tendencies in drilling fluids: Application of carbon-based nanomaterials. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 3733–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospanov, Y.K.; Kudaikulova, G.A. A comprehensive review of carbon nanomaterials in the drilling industry. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Khan, I.; Saleh, T.A. Advances in carbon nanostructures and nanocellulose as additives for efficient drilling fluids: Trends and future perspective-A review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 7319–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shen, J.; Huang, S.; Li, N.; Ye, M. Hydrothermal carbonization synthesis of a novel montmorillonite supported carbon nanosphere adsorbent for removal of Cr (VI) from waste water. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 93–94, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cai, W.; Liu, L. Hydrothermal carbonization synthesis of Al-pillared montmorillonite@ carbon composites as high performing toluene adsorbents. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 162, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zeng, G.; Jiang, L.; Tan, X.; Huang, X.; Yin, Z.; Liu, N.; Li, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of montmorillonite/hydrochar nanocomposites and application for 17β-estradiol and 17α-ethynylestradiol removal. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 4273–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- API RP 13B-1; Recommended Practice for field Testing Water-Based Drilling Fluids. American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Lankone, R.S.; Deline, A.R.; Barclay, M.; Fairbrother, D.H. UV-Vis quantification of hydroxyl radical concentration and dose using principal component analysis. Talanta 2020, 218, 121148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Luan, Q.; Yang, D.; Yao, X.; Zhou, K. Direct evidence for hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of Cerium oxide nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. 2011, 115, 4433–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Li, L. Efficient removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution with ecofriendly biomass-derived carbon@montmroillonite nanocomposites by one-step hydrothermal process. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 223, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Fuertes, A.B. Chemical and structural properties of carbonaceous products obtained by hydrothermal carbonization of saccharides. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 4195–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, W.; Liu, S.X. Hydrothermal synthesis, characterization, and KOH activation of carbon spheres from glucose. Carbohydr. Res. 2011, 346, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titirici, M.M.; Antonietti, M.; Baccile, N. Hydrothermal carbon from biomass: A comparison of the local structure from poly- to monosaccharides and pentoses/hexoses. Green Chem. 2008, 10, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.L.; Pei, M.S.; He, Y.J.; Du, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, L. Hydrothermal and activated synthesis of adsorbent montmorillonite supported porous carbon nanospheres for removal of methylene blue from waste water. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 89839–89847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.; Kaminski, L.; Downs, J. Xanthan stability in formate brines-formulating non-damaging fluids for high temperature applications. SPE-174228-MS. In Proceedings of the SPE European Formation Damage Conference and Exhibition, Budapest, Hungary, 3–5 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kong, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Optimizing oxygen functional groups in graphene quantum dots for improved antioxidant mechanism. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shen, X.; Xing, D. Carbon quantum dots as ROS-generator and -scavenger: A comprehensive review. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 208, 110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenzi, P.; Stagi, L. Carbon dots as oxidant-antioxidant nanomaterials, understanding the structure-properties relationship. A critical review. Nanotoday 2023, 50, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Owens, A.C.E.; Kulaots, I.; Chen, Y.; Kane, A.B.; Hurt, R.H. Antioxidant chemistry of graphene-based materials and its role in oxidation protection technology. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 11744–11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).