Abstract

Naomaohu coal from the Santanghu Basin, Xinjiang, is characterized by anomalously high Na and Ca contents, which strongly affect its gasification behavior and slagging tendency. However, the genetic linkage between geological alkali enrichment and their transformation during thermal processes remains insufficiently constrained. In this study, an integrated investigation combining coal seam profile analysis, coal petrography, mineralogical characterization, and fixed-bed gasification experiments was conducted to elucidate the enrichment mechanisms and transformation pathways of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs). A total of forty six samples were collected along a vertical seam profile to determine the depositional control of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs), and seven representative samples were further subjected to pressurized fixed-bed gasification. Alkali migration and mineral phase evolution were systematically analyzed using XRD, XRF, and SEM-EDS. The results indicate that Na enrichment is mainly controlled by groundwater infiltration and weak paleoweathering, while Ca accumulation reflects deposition in humid, Ca-rich mire environments. During gasification, Na volatilizes and recondenses as Na-feldspars (NaAlSi2O6) and NaCl, whereas Ca decomposes into gehlenite (Ca2Al2SiO7) and brownmillerite (Ca2AlFeO5). The formation of these low-melting Na–Al–Si phases and Ca–Fe–Al phases dominate the ash fusion and slagging behavior. This study establishes a coupled geological–thermal transformation model for AAEMs in high-Na coal, providing mechanistic insight into mineralogical inheritance and offering guidance for mitigating alkali-induced slagging during gasification.

1. Introduction

The presence of mineral matter in coal critically affects both utilization efficiency and environmental performance [1,2]. Among these components, alkali metals and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs, e.g., Na, K, Ca, Mg) are particularly problematic, as they reduce conversion efficiency and cause severe slagging, fouling, and corrosion in thermal systems [3,4,5,6]. With the transition from conventional combustion to advanced processes such as gasification, liquefaction, and Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC), coal gasification has become a cornerstone technology for the clean and efficient utilization of coal [7,8,9]. However, the volatilization and transformation of AAEMs during thermal treatment pose persistent challenges to stable and efficient operation [10].

Naomaohu coal from the Eastern Junggar Coalfield (Xinjiang, China), deposited in the Early Jurassic Badaowan Formation within a fluvial–deltaic system, provides a representative case for investigating these issues. This coalfield produces high-volatile bituminous coal with high reactivity, low ash, and low sulfur contents [11,12]. Naomaohu coal from this region is characterized by abnormally high Na contents, with Na2O content in coal ash commonly exceeding 2%, far above the Chinese average of 0.16% [13]. Such high Na2O content readily volatilizes during utilization, resulting in severe slagging and corrosion [14,15]. Previous mitigation attempts, including co-pyrolysis with biomass, treatment with organic acids, and the addition of mineral additives, have achieved only limited effectiveness, as they do not fundamentally address the geological origin and migration behavior of sodium enrichment [16,17,18,19]. These limitations highlight the necessity of clarifying both the genesis of alkali accumulation and its transformation pathways during gasification.

Alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs) play a vital role in determining ash fusion and energy efficiency during thermal utilization [20,21,22]. In Chinese coals, Na2O averages 0.16%, with sodium (Na) in coal is primarily associated with silicates (e.g., smectite and feldspars), and to a lesser extent, with carbonates (e.g., dawsonite), sulfates, phosphates and, rarely, with halides [23,24,25,26,27]. In bituminous coals, Na is predominantly clay-bound, whereas in low-rank coals it is often associated with organic matter [28]. Potassium, with an average concentration of 0.19% in Chinese coals [27], primarily occurs in silicate minerals such as illite and K-feldspar [23,28,29,30,31]. The mode of occurrence of these elements controls their thermal behavior during coal conversion [1,32].

During thermal treatment, the evolution of mineral composition governs ash melting and slagging behavior [33]. Due to differences in modes of occurrence, alkali metals and alkaline earth metals, their volatility varies during continuous heating process. Sodium shows relatively high volatility, increasing from 9.18–37% as temperature rises from 450 °C to 800 °C [34,35]. When gasification temperature increases to 1000 °C, about 82.14% sodium released to coal gas phase, mainly as NaCl [36]. Water-soluble Na exhibits the highest volatility and can be progressively transformed into water-insoluble forms during heating [37]. In contrast, potassium is mainly hosted in illite and is, therefore, less readily released than Na during thermal treatment [28,29]. It decomposes initially and then reacts with other substances to form new minerals. Potassium is released to some extent during the thermal treatment due to the exchange of Na and K ions when potassium silicate encounters NaCl vapor, forming potassium chloride vapor and sodium silicate, resulting in the release of K in the form of KCl [38]. At elevated temperatures, K can also migrate from the interior of silicate particles to their surfaces and enter the gas phase in atomic form [38]. During thermal treatment, only a small amount of Ca and Mg bound to organic matter is released to gas phase while the majority of Ca and Mg do not decompose but transform into insoluble substances [1,32,39]. When the heating temperature is below 1000 °C, main Ca-bearing phase detected by XRD is anhydrite, lime (CaO) and carbonate minerals (e.g., calcite), while gehlenite (Ca2Al2SiO7) and merwinite (Ca3Mg (SiO4)2) are the main Ca-bearing phase when the heating temperature above 1000 °C [40]. Previous research concludes the effects of alkali (Na, K) and alkaline-earth (Ca) metals on high-alkali coal thermal conversion [41,42,43,44,45]. Water-soluble Na volatilizes as NaCl(g) causing corrosion/deposition [42,45] while silicate-bound Na is stable [43,44]. Kaolin inhibits Na release to reduce risks [41].

Despite extensive research, the coupling between peat-forming environments, mineral associations, and alkali and alkaline earth metal (AAEM) migration under gasification conditions remains insufficiently constrained. In particular, few studies have systematically integrated coal facies analysis with gasification residue mineralogy to establish a process-oriented mechanism linking depositional controls to alkali redistribution and slagging behavior. In this study, a high-Na coal from the Eastern Junggar Basin was investigated by integrating coal petrography, mineralogical and geochemical characterization, and fixed-bed gasification experiments. The primary objective was to elucidate how depositional environment and mineral occurrence jointly govern Na migration pathways, mineral phase evolution, and slagging propensity during gasification.

This study integrates coal geology with high-temperature gasification chemistry to elucidate the genetic linkage between the enrichment of alkali and alkaline earth metals (Na, K, Ca, and Mg) and the resulting ash–slag behavior. The research was conducted through four sequential steps: (i) collecting a high-resolution vertical profile across the Naomaohu coal seam; (ii) performing standard coal quality, petrographic, and mineralogical–geochemical analyses; (iii) selecting seven representative coal samples covering various lithotypes and stratigraphic levels for fixed-bed pressurized gasification; and (iv) characterizing mineral transformations and AAEM migration in the gasification residues. The overall workflow progresses from field profiling, multi-scale characterization, fixed-bed gasification, ash/mineral phase analysis, forming a complete linkage between geological attributes and thermal behavior. This integrated approach bridges coal geology and gasification chemistry, offering mechanistic insight into slagging control and advancing the understanding of mineralogical evolution in high-sodium coals.

2. Samples and Methods

2.1. Geology Setting

The Naomaohu Coalfield is located in the southeastern part of the Santanghu Basin, in northeastern Xinjiang, China. The Santanghu Basin is a northwest–southeast-trending extensional tectonic basin developed on a Carboniferous–Permian basement and has experienced multi-stage tectonic evolution from the Late Paleozoic to the Cenozoic [46]. Structurally, the basin exhibits a north–south zonation characterized by a central depression, within which the Naomaohu Depression constitutes the principal coal accumulation area. Influenced by Cenozoic tectonic uplift, some coal seams in the northern part of the coalfield are exposed at the surface, forming large open-pit mines (Figure 1A) [47,48]. The coal-bearing strata in the basin are mainly from the Lower to Middle Jurassic, represented by the Badaowan and Xishanyao formations, which were deposited in fluvial–deltaic environments. These formations host multiple thick coal seams, with cumulative thicknesses exceeding several tens of meters, providing abundant coal resources [49].

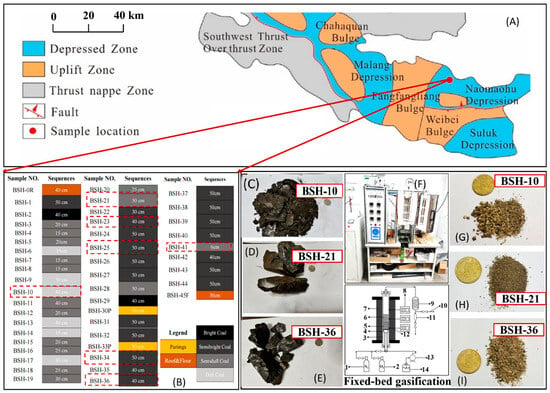

Figure 1.

Overall research framework integrating coal seam profiling, multi-scale characterization, and fixed-bed gasification experiments, (A) geology setting; (B) field profiling; (C–E) pictures of lithotype samples; (F) fixed-bed gasification, 1—nitrogen; 2—oxygen; 3—reactor; 4—sieve plate; 5—corundum ceramic ball; 6—coal sample; 7—heating jacket; 8—temperature controller; 9—condenser; 10—gas outlet; 11—liquid collection tank; 12—thermocouple; 13—peristaltic pump; 14—high-purity water; (G–I) representative samples of gasification ash (The Chinese RMB coin is included for scale reference).

2.2. Sample Information

The coal samples used in this study were collected from the open-pit mining area of the Naomaohu Coalfield in Baishihu Town, Xinjiang, China. A total of 46 samples were obtained based on lithologic features and coal seam structure, including 42 coal samples, one roof sample, two parting samples, and one floor sample, with a cumulative thickness of 16.36 m. Based on the macroscopic coal rock characteristics, perform stratified sampling, the thickness and basic properties of each layer are shown in Figure 1B. According to the lithological characteristics of the coal samples, the samples are mostly semi-bright and semi-dull coal, with fewer bright and dull coals. The sample thickness ranges from 6 cm to 50 cm, with an average thickness of 37.2 cm. The positions of the sample collection profiles can be seen in Figure 1B. The fracture types of the coal samples are mainly conchoidal fracture, with a small number of vitreous fractures and irregular fractures. BSH-5, BSH-6, and BSH-9 exhibit an oily luster, while BSH-29 exhibits an asphalt luster. BSH-13 and BSH-30P have a high silk carbon content. A weathering zone and a laminated structure can be observed between BSH-20 and BSH-21.

Based on mineralogical and geochemical characteristics determined from proximate analyses and XRF determination, seven representative samples, BSH-10, BSH-21, BSH-23, BSH-25, BSH-34, BSH-36, and BSH-41, were selected for fixed-bed gasification. The coal lithotypes of samples BSH-10, BSH-21, and BSH-36 are shown in Figure 1C, Figure 1D, and Figure 1E, respectively. The corresponding ash obtained from the fixed-bed gasification experiment (Figure 1F) is presented in Figure 1G, Figure 1H, and Figure 1I, respectively.

2.3. Fixed-Bed Gasification Simulation

The gasification simulation experiments were conducted at the School of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing), using an electrically heated fixed-bed pressurized system (Figure 1F). The system consists of a reaction tube, an electric heater, a temperature–pressure control unit, and a condenser. The reaction tube, made of an iron–nickel–chromium alloy, is 50 mm in diameter and 600 mm in length, and can withstand pressures up to 5 MPa. It is placed inside a heating bed, where the electric heater provides the required temperature, monitored by a thermocouple positioned within the bed. The temperature–pressure controller regulates operating conditions over a range of 25–1150 °C. The condenser collects coal tar, while gas products are captured using a glass bottle connected to a sealed collection bag [50]. High-purity water is delivered into the reactor in italic a peristaltic pump, vaporized, and subsequently introduced into the coal bed. The overall configuration of the system follows the design described in [51]. Weigh around 30 g of air-dried basis coal sample with a particle size of 1–2 mm were filled into the reaction tube. During the pyrolysis stage, N2 was introduced, while during the gasification stage when the temperature approached to 1000 °C, oxygen and water vapor were introduced. The N2 flow rate was 50 mL/min and the O2 flow rate was 20 mL/min, respectively. The reaction temperature and pressure were 1000 °C and 2 Mpa, respectively, which is consistent with the reaction conditions of the nearby gasification plant in the mining area. After the reaction was completed, the ash could be carried out when the temperature reached room temperature. After the experiment, coal gasification ash was collected to track changes of the alkaline elements in coal.

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. Proximate and Ultimate Analyses

Proximate analyses were performed using a LECO TGA701 (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA) thermogravimetric analyzer following the ASTM D7582–12 standard [52]. Approximately 1.05 g of 60-mesh coal was placed into ceramic crucibles for moisture, volatile matter, ash, and fixed carbon determinations. The procedure was computer-controlled to ensure analytical precision. The calorific value was measured using a LECO AC600 calorimeter (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA). Total sulfur (St,d) was analyzed externally by the Shanxi Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources using standard combustion analysis. The basic chemical properties of profile samples are listed in Appendix A Table A1.

2.4.2. Petrological Analysis

Polished briquettes were prepared for maceral identification and vitrinite reflectance measurements. Approximately 2.5 g of 20-mesh coal was mixed with epoxy resin and hardener, poured into cylindrical molds, and cured in a drying oven. The solidified briquettes were ground using 320-, 400-, and 600-grit SiC papers, followed by polishing with 1.0 μm and 0.3 μm Al2O3 suspensions. Final polishing was performed using 0.04 μm colloidal silica until a mirror-smooth surface was obtained. After air-drying, the briquettes were stored in a desiccator before microscopic examination. Maceral identification was conducted using a Zeiss Universal reflected-light microscope, equipped with a 40× oil-immersion objective and a 1.6× magnification changer. Maceral classification followed the 1994 ICCP classification scheme for vitrinite, inertinite, and liptinite [53,54,55]. For each sample, 500 points were counted to quantify maceral proportions.

2.4.3. XRD and XRF

Mineralogical compositions of raw coals and gasification ashes were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) at the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology. Analyses were performed using a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å), operated at 40 kV and 40 mA, over a scanning range of 5–70° 2θ, with a step size of 0.02° and a scan rate of 4°/min. X-ray diffractograms of the non-coal sampleswere subjected to quantitative mineralogical analysis using Siroquant. Major element oxides (SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, K2O, Na2O, Fe2O3, MnO, MgO, TiO2, P2O5) were determined using X-ray fluorescence (XRF). Loss on ignition (LOI) was measured following ASTM D7348–13 [56]. For XRF analysis, samples were heated to 750 °C to obtain ash residues, which were then mixed with a fluxing agent and fused into glass beads for quantitative analysis. Major element data for all samples are summarized in Appendix A Table A2.

2.4.4. SEM-EDS

Morphological and mineralogical characteristics of raw coal and gasification ash were examined using scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM–EDS, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Analyses were conducted at the Tsinghua University Analytical Center using a Merlin field-emission SEM equipped with an Oxford EDS detector. Raw coal and ash powders (200 mesh) were mounted on conductive carbon tape and coated with a thin layer of gold. SEM–EDS analyses were performed in high-vacuum mode at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, a working distance of 8–10 mm, and a beam current optimized for quantitative analysis. All procedures followed the Chinese Standard GB/T 17361–1998 [57].

3. Coal Quality and Petrography

3.1. Coal Quality Characteristics

According to the Chinese national standards GB/T 15224.1–2018, GB/T 15224.2–2021, and GB/T 15224.3–2010 [58,59,60], the Naomaohu coals are classified as high-volatile bituminous coal characterized by very low ash yield (Ad < 10%), very low sulfur (St,d < 0.5%), and high-volatile matter yield. Vertical variations in coal quality parameters along the seam profile are shown in Figure 2. The inherent moisture (Mad) decreases from the roof toward the middle of the seam and then increases again toward the floor. Overall, samples near the roof contain higher moisture than those near the floor. A marked decrease in moisture is observed at the coal partings, consistent with the findings [61], who reported that parting layers commonly exhibit significantly lower moisture.

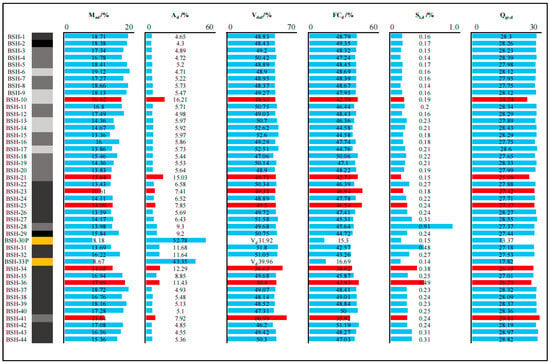

Figure 2.

Vertical distributions of proximate analysis, total sulfur, and high calorific value along section of profile (the items marked in red are the selected gasification samples).

The ash yield (Ad) increased sharply between 9.3 and 12.9 m from the roof (samples BSH-21 to BSH-36), corresponding to the intervals adjacent to coal partings where mineral matter intrusion is common. Elevated ash values were also observed in samples BSH-10 and BSH-21 (16.21% and 15.03%, respectively), which may be attributed to short-term fluctuations in the sedimentary environment. The volatile matter (Vdaf) remained relatively stable across the seam, except for slightly higher values in samples BSH-14, BSH-15, and BSH-41 (52.62%, 52.60%, and 60.99%). The total sulfur (St,d) increased toward the lower part of the seam, with the highest sulfur content occurring in BSH-28 (12.9 m from the roof). This enrichment is likely related to the influence of the overlying parting layer. The mine–water leaching affects sulfur distribution in the Eastern Junggar coalfield [61], which may partially explain the elevated sulfur in the lower layers. The fixed carbon (FCd) and gross calorific value (Qg,rd) exhibit only minor variation throughout the profile. Although BSH-41 contains relatively low fixed carbon (35.92%), its calorific value is higher than most samples, indicating that carbon quality rather than quantity controls heating performance.

Overall, aside from the influence of parting layers, the chemical properties of Naomaohu coal show limited variation along the vertical profile (Figure 2), suggesting a relatively stable depositional environment with a low probability of major interruption during peat accumulation.

3.2. Coal Petrography and Coal Facies

The Naomaohu coal is strongly dominated by vitrinite (54.5–95.6%, average 84.9%), in contrast to the typically inertinite-rich Jurassic coals of the Eastern Junggar region [1,61]. Inertinite proportions are variable (0.7–21.0%, average 3.4%), and liptinite is minor (1.3–16.4%, average 7.1%), with cultinite being the principal subtype. Figure 3a–h illustrates the maceral characteristics of the Naomaohu coal. Coal facies parameters derived from maceral data, including the Tissue Preservation Index (TPI), Gelification Index (GI), Groundwater Influence Index (GWI), and Vegetation Index (VI), are shown in Figure 3 and indicate deposition in limno-telmatic and bog environments under persistently high water levels [62,63]. The quantitative results of the macerals of the samples are shown in Appendix A Table A3.

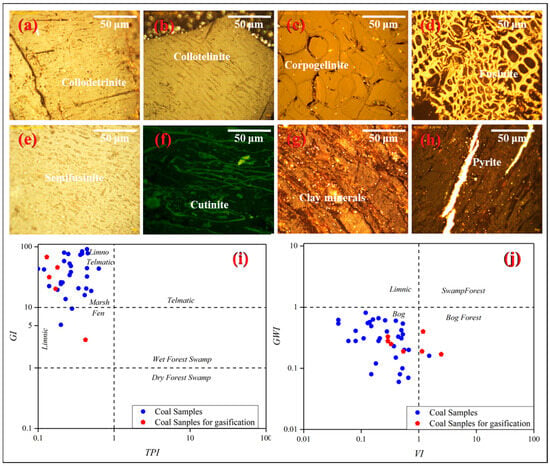

Figure 3.

Macerals in Naomaohu coal and its coal facies characteristics, (a–d) Vitrinite and inertinite macerals; (e–h) coal facies indices (TPI, GI, GWI, VI) (i,j).

The low TPI values suggest that organic matter experienced strong degradation under relatively high hydrodynamic energy. The wide variation in the GI reflects frequent water-level fluctuations under long-term deep-water conditions, which favored the development of collodetrinite. The VI indicates that the peat-forming vegetation was dominated by woody plants, whereas the low GWI implies minimal groundwater input, with precipitation and surface-water inflow (e.g., lakes and rivers) serving as the primary water sources [64]. These characteristics point to peat accumulation in a deep-water, low-oxidation mire environment with strong gelification but poor preservation of organic matter. The predominance of collodetrinite and high vitrinite contents therefore record a stable, waterlogged depositional system with sustained input from woody peat-forming vegetation [65]. Coal facies analysis also provides important insights into sedimentary controls on mineral sources and modes of occurrence. Hydrodynamic intensity and redox conditions regulate the deposition of carbonates, silicates, and pyrite, thereby influencing the distribution of mineral matter within the seam [64]. Since mineral occurrence directly affects ash fusion behavior and slagging tendency during gasification, understanding the facies–mineralogy relationship offers a scientific basis for assessing slagging risks, particularly in high-sodium coals such as those of the Naomaohu seam [65,66].

4. Mineralogical and Geochemical Characteristics of AAEMs

4.1. Mineralogy

X-ray diffraction (XRD) results of representative coal, roof, parting, and floor samples show that the mineral assemblage of the Naomaohu coal is dominated by clay minerals (20–80%) and quartz, accompanied by minor K-feldspar, plagioclase, calcite, and siderite (Table 1). The clay minerals, primarily illite, kaolinite, and mixed-layer illite/smectite, serve as the principal hosts for Na and K. Their vertical distribution is highly variable, with pronounced enrichment in the middle and lower portions of the seam, indicating stratigraphic heterogeneity in alkali metal occurrence. Quartz displays a similar enrichment trend in the lower seam, which likely reflects enhanced terrigenous detrital input during peat accumulation. Feldspars, another important carrier of alkali elements, were only detected in the lowermost coal sample (BSH-41), implying localized contributions from detrital influx or discrete volcanic-derived materials. Calcite, the dominant Ca-bearing phase, occurs infilling fractures or forming euhedral to subhedral crystal clusters, with the highest abundance observed in BSH-36 (16.3%) [67]. Siderite, representing Fe-carbonates under reducing conditions, is notably enriched in BSH-25. Its presence reflects the low-sulfur nature of Naomaohu coal, where Fe predominantly occurs as carbonates rather than as pyrite, consistent with the weakly reducing, freshwater depositional environment inferred from coal facies analyses. These mineralogical characteristics form the essential baseline for interpreting the occurrence modes and stratigraphic distribution of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs) in the Naomaohu seam [23,24]. Identifying clay minerals, feldspars, calcite, and siderite as key mineral carriers provides critical constraints on their thermal transformation pathways during gasification, including alkali release, silicate–aluminate phase evolution, and the development of low-melting eutectics controlling slagging behavior.

Table 1.

Mineral compositions (%) of coal by XRD and Siroquant.

4.2. Major Elements

4.2.1. Correlation Between Major Elements and Ash Yield

Major element geochemistry provides important insights into coal-forming processes and the enrichment mechanisms of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs) [68]. From a utilization perspective, these elements ultimately enter the ash or slag during combustion and gasification, where they play a critical role in ash fusion, slagging, and overall conversion performance [33,68]. Major element concentrations for all 44 samples (42 coal and 2 partings) are listed in Appendix A Table A2. Compared with average Chinese coals, the Naomaohu samples show significant enrichment in Na, K, Ca, and Mg (Table 2), confirming their high-alkali characteristics.

Table 2.

Major elements in samples and enrichment coefficient compared with Chinese coal.

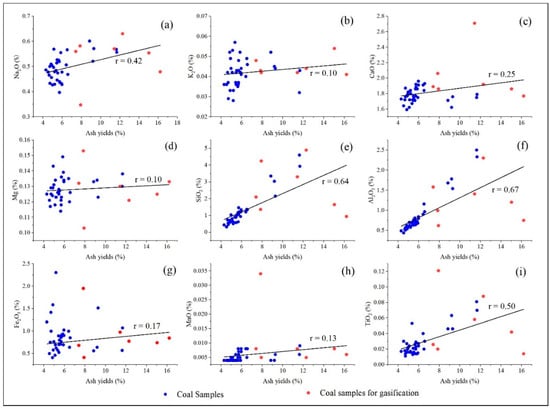

Correlation analysis between major elements (Na2O, K2O, CaO, MgO, SiO2, Al2O3) and ash yield (Ad) reveals distinct occurrence behaviors (the parting samples were not included in the subsequent). Sodium is the most enriched element, with a concentration coefficient of 3.06 (Appendix A Table A4). Na2O shows a moderate correlation with ash yield (r = 0.42), suggesting partial mineral association. Its positive weak correlations with SiO2 (r = 0.38) and Al2O3 (r = 0.64) indicate that a portion of Na is incorporated into silicate and aluminosilicate minerals. The remaining Na likely occurs in water-soluble, organically bound, or amorphous forms. This mixed occurrence mode is typical of high-sodium coals. In contrast, K2O, CaO, and MgO exhibit weak or negligible correlations with ash yield (r < 0.22; Figure 4), implying that these elements predominantly occur in non-crystalline, organic-associated, or weakly crystalline carbonate/silicate phases, rather than in ash-forming minerals. Weak to moderate correlations between SiO2, Al2O3, and ash yield confirm that clay minerals are the primary contributors to coal ash.

Figure 4.

Relationship of major elements with coal ash yield. (a) Na2O vs. ash yield; (b) K2O vs. ash yield; (c) CaO vs. ash yield; (d) MgO vs. ash yield; (e) SiO2 vs. ash yield; (f) A2O3 vs. ash yield; (g) Fe2O3 vs. ash yield; (h) MnO vs. ash yield; (i) TiO2 vs. ash yield.

Overall, the major element–ash relationships quantitatively demonstrate that Naomaohu coal is a high-alkali coal (Na = 2.62%, K = 0.87%), with AAEMs occurring in both mineral-bound and non-mineral forms. These geochemical characteristics provide a fundamental basis for interpreting element release and migration during gasification and establishing links between coal quality, mineralogy, and slagging behavior in high-sodium coals.

4.2.2. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) Analysis of Major Oxides and Ash Yield

To investigate multivariate relationships between major oxide compositions and ash yield in Naomaohu coal, agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) was applied to standardized geochemical data from 44 coal samples using Euclidean distance and Ward’s linkage method. The dendrogram identifies three distinct compositional clusters. Cluster I is characterized by low SiO2-Al2O3 contents and low ash yields, indicating limited detrital input and a greater contribution from dispersed or authigenic minerals. Cluster II shows moderate SiO2-Al2O3 and Fe2O3 contents with intermediate ash yields, reflecting enhanced aluminosilicate input from clays and quartz. Cluster III exhibits high SiO2-Al2O3 contents and markedly elevated ash yields, suggesting strong detrital or parting-related mineral enrichment. Overall, ash yield is mainly controlled by combined aluminosilicate inputs rather than a single oxide. In contrast, Na2O and CaO exert limited influence on clustering, indicating that AAEM enrichment is decoupled from bulk ash content and governed by specific mineral associations.

4.2.3. Variation of Main Major Elements Along Section of Profile

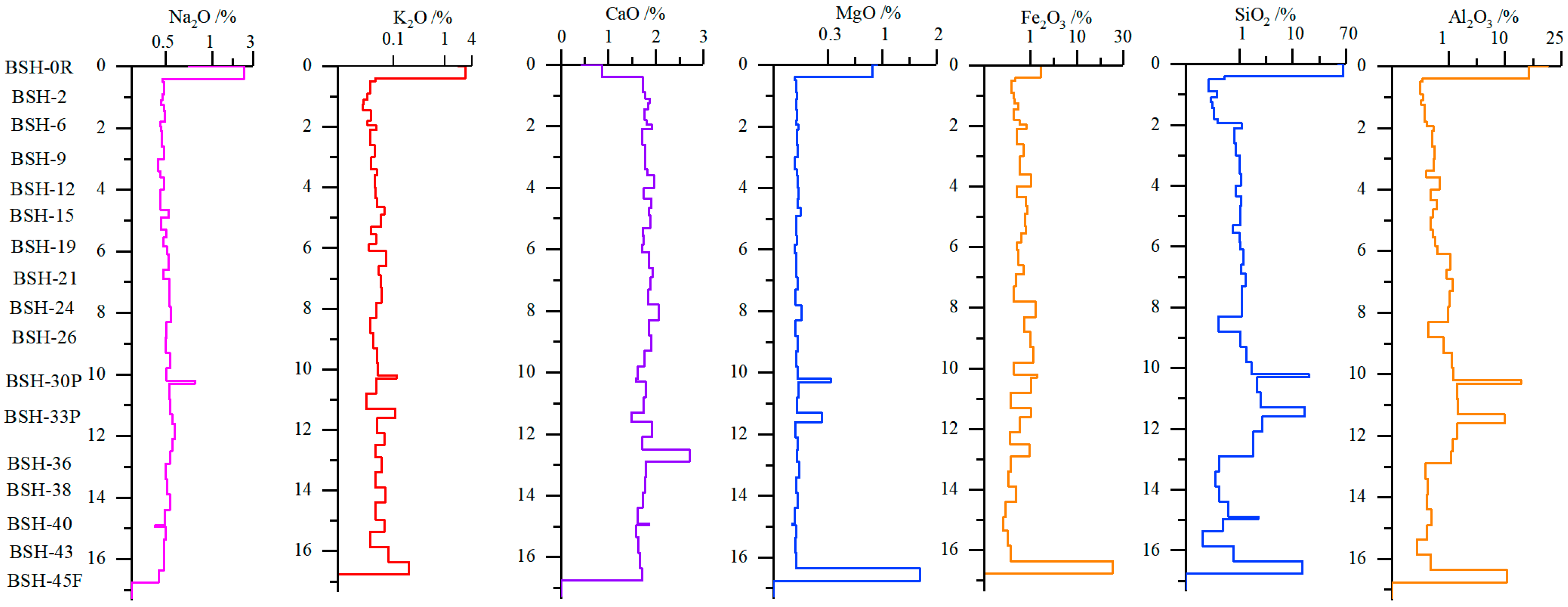

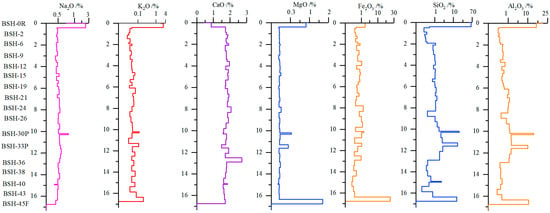

The vertical distribution of major elements along the Naomaohu coal profile exhibits distinct patterns controlled by sedimentary environment, hydrological conditions, and terrigenous input (Figure 5). Na2O shows relatively stable concentrations throughout most of the seam but displays clear enrichment at coal–rock interfaces and in the lower part of the seam. This enrichment pattern is consistent with the influence of highly mineralized groundwater, rather than clay mineral abundance, as previously reported for the Eastern Junggar coals [69,70]. The localized Na elevation near partings suggests secondary ionic exchange or infiltration during diagenesis. K2O shows greater variability toward the lower portion of the seam but remains low overall, reflecting the limited development of K-bearing clay minerals (e.g., illite) indicated in XRD results. CaO is markedly enriched in several lower-seam samples, corresponding to deposition in a humid, calcium-rich mire environment favorable for carbonate precipitation. This agrees with the observed abundance of calcite in the same intervals. MgO varies little along the profile, implying restricted mobility and limited detrital or groundwater contribution during peat accumulation and early diagenesis. In contrast, SiO2 and Al2O3 increase significantly in the vicinity of partings, reflecting strong terrigenous clastic input during episodic sediment influx. These peaks coincide with mineralogical evidence of elevated quartz and kaolinite, confirming that the inorganic material associated with partings substantially influences the geochemical profile. Overall, the vertical variations of major elements reveal the combined controls of groundwater chemistry (Na), mire depositional conditions (Ca, Mg), and detrital influx (Si, Al) on elemental distribution in the Naomaohu coal. These findings refine the genetic understanding of alkali and alkaline earth enrichment and provide essential constraints for interpreting their behavior during gasification.

Figure 5.

Change of major elements in coal seam profile.

4.3. Validation of Coal Facies Interpretation Based on Paleobotanical and Palynological Evidence from the Eastern Junggar Basin

Previous paleobotanical and palynological studies from the eastern Junggar Basin provide independent constraints on peat-forming vegetation, mire hydrology, and paleoclimate evolution, supporting the coal facies interpretations presented in this study. Paleobotanical investigations from the Shaerhu Coalfield indicate that Middle Jurassic vegetation was dominated by abundant ferns, gymnosperms, and woody plants, suggesting a humid warm–temperate to subtropical climate favorable for extensive mire development [71]. The dominance of arboreal plant remains implies strong terrestrial organic input, consistent with the vitrinite-rich coal facies interpreted as forested mire environments. Palynological analyses from the Dananhu Coalfield further document diverse Early to Middle Jurassic spore–pollen assemblages dominated by fern spores and gymnosperm pollen, indicative of freshwater mires under humid climatic conditions [72]. Variations in sporopollen assemblages reflect fluctuating water table conditions during peat accumulation, which agree well with the vertical changes in maceral composition and coal facies observed in this study. Regional palynological syntheses confirm the long-term predominance of terrestrial vegetation and continental depositional systems in the Junggar Basin, with coal-forming environments characterized by low-salinity freshwater mires rather than marine influence [73]. In addition, tectonic studies suggest that Middle Jurassic coal accumulation occurred during a relatively stable intracontinental basin stage with widespread lacustrine–swamp systems [74], favoring persistent peat accumulation.

Overall, the coal facies interpretations based on maceral composition and petrographic characteristics are well supported by independent paleobotanical and palynological evidence, providing a robust paleoenvironmental framework for understanding peat formation and associated geochemical characteristics of high-Na coals.

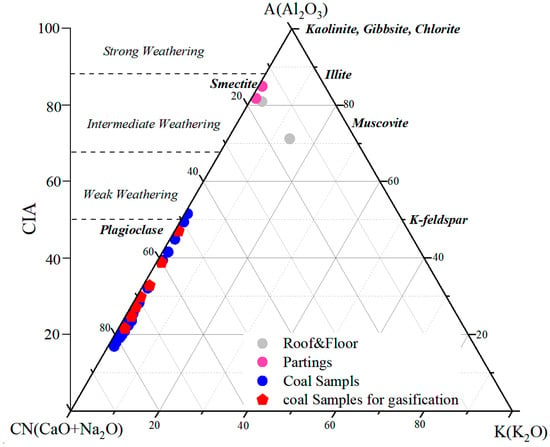

4.4. Paleoweathering Conditions Inferred from Major Elements

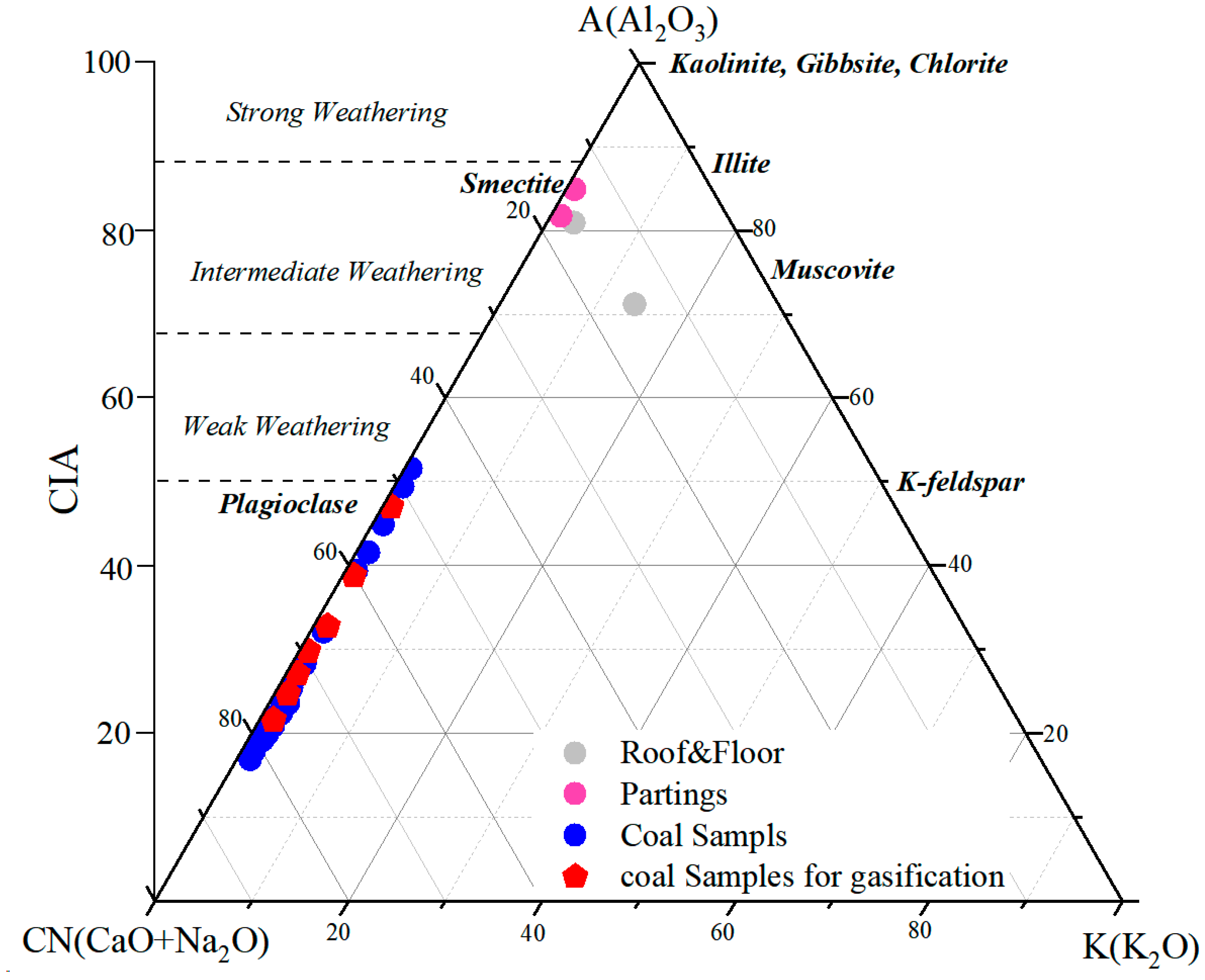

Major oxide compositions provide useful constraints on paleoweathering intensity during peat formation and early diagenesis [75,76]. During coal accumulation, detrital minerals supplied to the peat underwent variable physical and chemical weathering depending on climatic conditions. To assess the degree of chemical alteration in the Naomaohu seam, CIA (Chemical Index of Alteration) and CIW (Chemical Index of Weathering) values were calculated, and an A–CN–K ternary diagram was constructed (Figure 6) [76]. The Naomaohu samples exhibit CIW values ranging from 17.10 to 94.69 (average 33.43) and CIA values ranging from 16.87 to 85.51 (average 32.59). The majority of samples fall within the low-CIA/low-CIW field, plotting close to the feldspar-rich side of the A–CN–K diagram. These patterns indicate that the inorganic fraction of the coal experienced very weak chemical weathering during deposition. In this study, these indices are explicitly qualified and used as relative indicators of chemical alteration rather than as direct proxies for palaeoweathering in coal systems. Most samples show minimal migration toward the kaolinite apex, suggesting limited leaching of Ca, Na, and K, and the preservation of primary aluminosilicate minerals. The weak degree of chemical alteration is consistent with the sedimentological context of the Naomaohu seam, where coal facies analyses indicate deposition under sustained deep-water, low-oxidation mire conditions. In such environments, reduced exposure of detrital minerals to atmospheric weathering, together with rapid sediment accumulation and high water levels, suppresses chemical leaching. Episodic detrital influx, as reflected by elevated SiO2 and Al2O3 near partings (Section 4.2), further contributes to the prevalence of weakly weathered material. Collectively, the CIA–CIW results suggest that the Naomaohu peat accumulated under a humid but low-energy sedimentary system where hydrological stability and rapid burial limited chemical weathering intensity. This weak paleoweathering background explains the preservation of easily altered minerals such as feldspars and contributes to the distinct AAEM occurrence patterns observed in the seam. The paleoweathering framework established here provides important constraints on the initial mineralogical composition that controls AAEM release, mineral transformation, and slagging behavior during gasification.

Figure 6.

The A–CN–K triangular diagram showing CIA of studied coal (refer to [77]).

4.5. Coupling Between Geological Enrichment and Gasification-Induced Mineral Transformations

To quantitatively link geological enrichment processes with gasification-induced mineral transformations, vertical geochemical variations in the coal seam were directly compared with the composition and slagging behavior of the corresponding gasification residues. The key causal relationships between coal geochemistry and gasification behavior are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Linkage between geological enrichment characteristics and gasification-induced mineral transformations.

4.6. Comparison with Previous High-Temperature Transformation and Gasification Studies

The observed alkali metal migration and mineral phase evolution during fixed-bed gasification in this study are broadly consistent with previously reported high-temperature transformation and gasification studies, while also exhibiting several notable distinctions. Previous investigations have shown that Na can partially volatilize at elevated temperatures and subsequently recondense on cooler mineral surfaces or react with aluminosilicates to form low-melting phases during gasification or combustion. Similar behavior is inferred in this study from the enrichment of Na-bearing aluminosilicate phases and glassy materials in the gasification residues.

However, compared with entrained flow or fluidized bed systems, the fixed-bed gasification conditions applied here promote stronger spatial heterogeneity in temperature and gas composition. This heterogeneity limits extensive Na volatilization and instead favors localized recondensation and melt formation. As a result, Na is preferentially incorporated into aluminosilicate melt phases rather than being completely released into the gas phase. In addition, the high initial Na content and its strong association with clay minerals in the studied coal further enhance the formation of low-melting, Na-rich aluminosilicate phases, leading to higher slagging indices than those reported for lower-alkali coals.

Overall, the similarities and differences relative to previous studies highlight that alkali metal behavior during gasification is jointly controlled by reactor configuration, temperature regime, and the geological occurrence of Na. These comparisons provide important context for interpreting the observed mineral transformations and slagging behavior under fixed-bed gasification conditions.A comparison of alkali metal behavior under different high-temperature conversion systems is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of alkali metal behavior under different high-temperature conversion systems.

5. High AAEM Migration Characteristics During Fixed-Bed Gasification

Building on the AAEM occurrence modes and geological enrichment background established in Chapter 4, this chapter further examines the migration pathways and mineral phase transformations of AAEMs under gasification conditions.

5.1. Raw COAL Properties

Seven representative coal samples (BSH-10, BSH-21, BSH-23, BSH-25, BSH-34, BSH-36, and BSH-41) were selected to capture the vertical variability of the Naomaohu seam in terms of lithotype, mineral carriers, and AAEMs (Na, K, Ca, Mg) abundance (Table 5). These samples span different depths from the upper, middle, and lower portions of the seam (3.0–14.96 m), enabling a systematic comparison of their geochemical and mineralogical responses during gasification. Although clay minerals and quartz dominate all samples, the targeted coals differ notably in their AAEM-bearing phases: BSH-25 contains siderite, BSH-36 is enriched in calcite, and BSH-41 host feldspar. Correspondingly, their total AAEMs contents range from 2.35% to 3.45%, representing distinct mineralogical controls, from carbonates to aluminosilicates. These contrasts ensure that both mineral-bound and relatively mobile AAEM occurrence modes are represented. Consequently, this sample set provides a robust basis for elucidating AAEM migration pathways and mineral transformation mechanisms under fixed-bed gasification conditions.

Table 5.

Gasification raw coal samples and their characteristics.

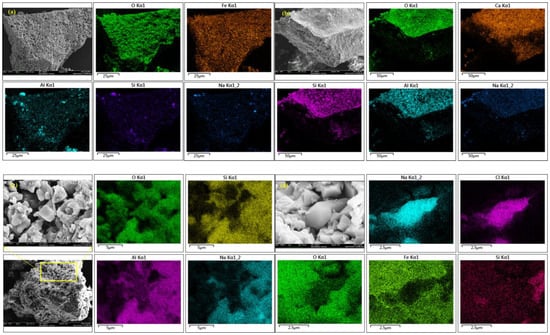

5.2. Mineralogical Evolution and AAEM Transformation During Fixed-Bed Gasification

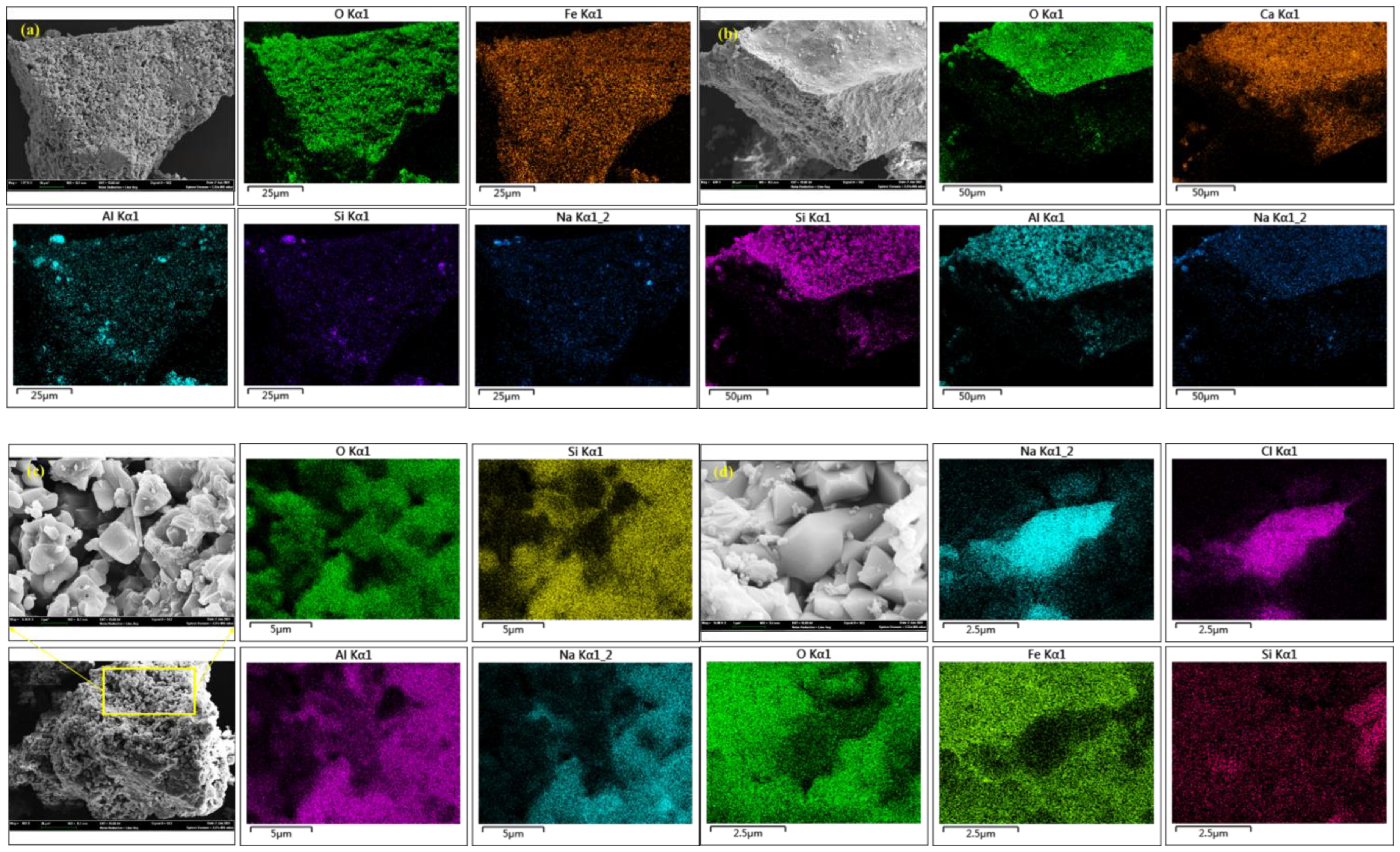

XRD and SEM–EDS analyses of the gasification ash show that fixed-bed gasification induces pronounced mineralogical reorganization, transforming the original clay- and quartz-dominated assemblage into new Ca-Al-Si, Na-Al-Si, and Fe-oxide phases (Table 6; Figure 7). As shown in Figure 7, Na exhibits a distinctly heterogeneous spatial distribution and is preferentially concentrated within Al–Si-rich domains, whereas little association with discrete sulfur-rich or salt-like phases is observed. This co-localization pattern suggests that sodium is largely involved in the formation of Na-Al-Si-bearing aluminosilicate phases through high-temperature solid-phase reorganization and re-condensation processes, rather than being completely volatilized and removed from the system. In contrast, Ca displays a relatively more dispersed distribution, with localized enrichment associated with Si-rich regions, indicating partial incorporation into Ca-silicate phases during gasification. The different spatial behaviors of Na and Ca reflect their distinct migration mechanisms and affinities toward silicate matrices at elevated temperatures. The spatial redistribution patterns of alkali metals observed in this study are consistent with previous high-temperature transformation studies on high-alkali coals. The Na and Ca in Zhundong coal preferentially participate in aluminosilicate melt formation during entrained-flow pyrolysis, resulting in heterogeneous elemental distribution within ash particles [77], Na and K migration under oxy-fuel fluidized-bed combustion conditions is strongly controlled by mineral associations and high-temperature re-condensation processes rather than complete volatilization [78].

Table 6.

XRD results of fixed-bed gasification ash (main phases).

Figure 7.

(a–d) SEM-EDS determination of new generated minerals in gasification coal ash. BSH-36A), showing the spatial distributions of Na, Ca, Fe, Al, and Si. Al and Si delineate the aluminosilicate framework of the ash particles, while Na is heterogeneously distributed and preferentially concentrated within Al–Si-rich domains. Ca shows a relatively dispersed distribution and locally overlaps with Si, indicating the formation of Ca-bearing silicate and aluminosilicate phases. Fe occurs mainly in discrete regions corresponding to Fe oxides and Ca–Fe–Al phases formed during fixed-bed gasification.

Compared with these studies, the SEM-EDS maps obtained in the present work provide direct micro-scale spatial evidence that Na in Naomaohu coal is preferentially redistributed into Al-Si-rich domains during fixed-bed gasification. This further supports the view that alkali metal migration in high-sodium coals is dominated by solid-phase reorganization and mineral interaction at elevated temperatures.

These transformations reflect a sequence of decomposition, release, and recombination reactions under high-temperature gasification conditions. Carbonates (e.g., calcite, siderite) decompose early, generating CaO and FeOx, while clay minerals release Al–Si structural units. These liberated components react to form low-melting Ca-bearing silicates and aluminosilicates, including gehlenite (Ca2Al2SiO7) and mayenite (Ca12Al14O33). Simultaneously, siderite- and pyrite-derived Fe reorganizes into magnetite (Fe3O4) and hematite (Fe2O3). Locally, Ca–Fe–Al phases such as brownmillerite (Ca2AlFeO5) are produced. Sodium exhibits a volatilization–recondensation pathway: Na initially released from water-soluble and weakly bound mineral forms volatilizes at elevated temperatures, later recrystallizing as Na-feldspars (NaAlSi2O6), Na-bearing aluminosilicates, and minor NaCl during cooling. Potassium remains more tightly integrated within aluminosilicate frameworks and shows limited volatilization, whereas magnesium participates primarily in forming amorphous Mg–Ca–Al–Si glass phases. These transformations vary stratigraphically: upper-seam samples favor Ca-rich phases, whereas lower-seam samples yield more Na-rich aluminosilicates, consistent with their raw AAEMs distributions. Overall, gasification redistributes AAEMs into reactive and often low-melting compounds, establishing the mineralogical basis for their migration pathways and the subsequent slagging behavior observed in the Naomaohu coal.

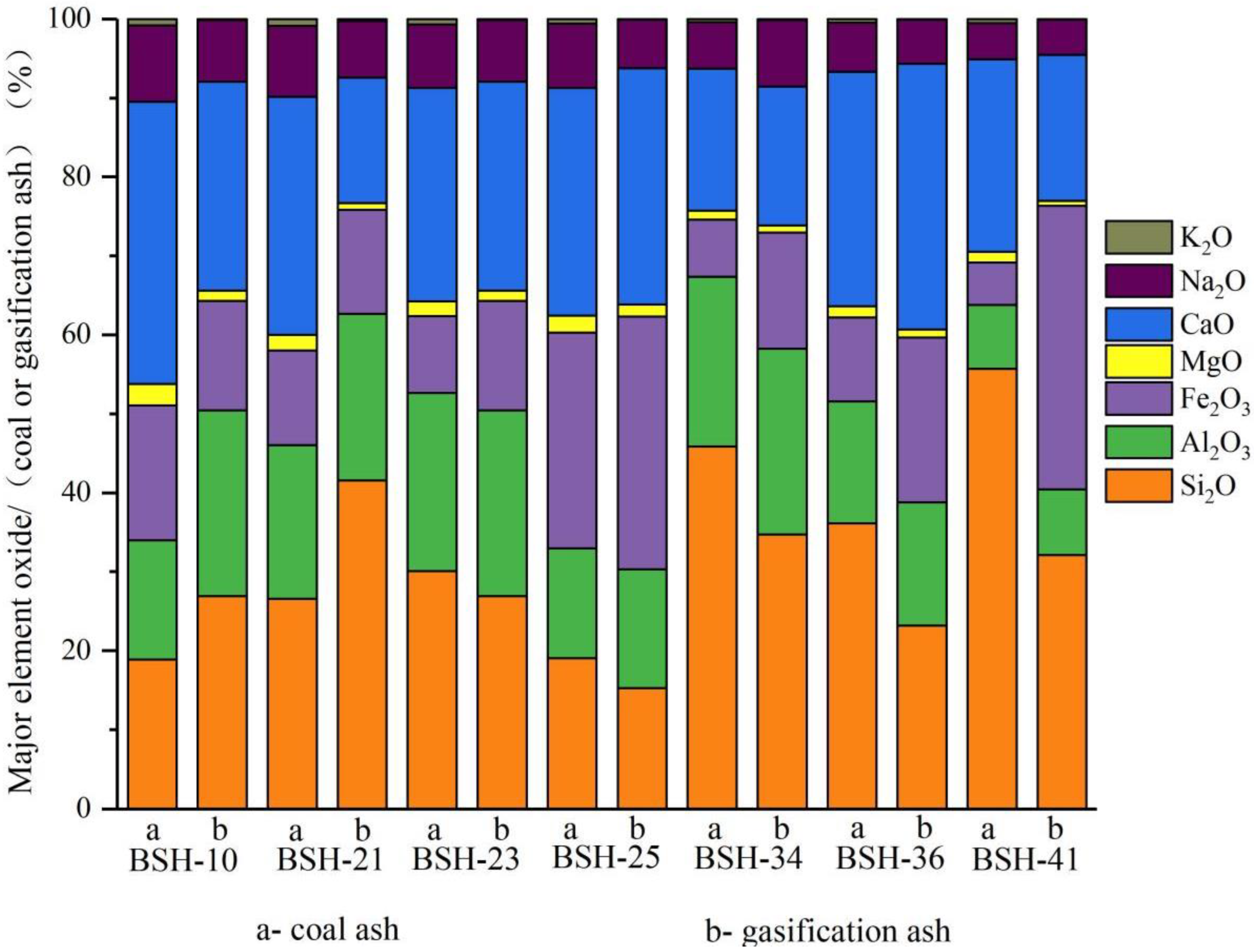

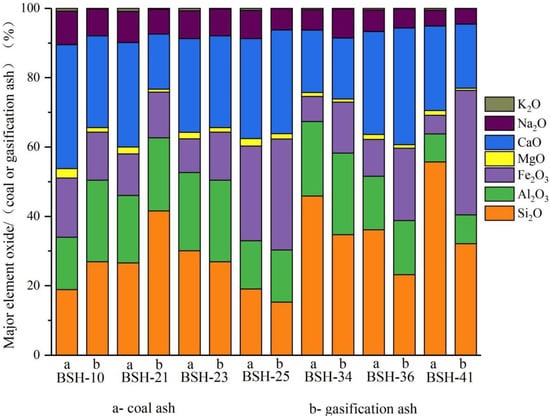

5.3. Major Element Composition Before and After Fixed-Bed Gasification

Major element oxides in the raw coal and gasification ash exhibit systematic compositional shifts that reflect the redistribution of alkali and alkaline earth elements during high-temperature conversion (Figure 8; Appendix A Table A5). Sodium shows a clear decrease after gasification (from an average of 6.68% in raw coal to 5.22% in ash), indicating partial volatilization even under pressurized conditions (2 MPa). Calcium also declines in most samples, whereas Fe2O3 increases markedly due to the oxidation of Fe-bearing minerals, resulting in the accumulation of Fe-oxides. With CaO (19.57%) and Fe2O3 (18.15%) both exceeding 15%, Naomaohu ash is classified as high-Ca and high-Fe ash. In contrast, SiO2 and Al2O3 remain relatively stable, maintaining a consistent ratio (SiO2/Al2O3 ≈ 1.6), suggesting limited redistribution of the aluminosilicate matrix during gasification. MgO shows only slight reductions, consistent with its weak mobility under the tested conditions. The mineralogical characterization confirms that Na becomes incorporated into Na, and Ca-aluminosilicate-glass phases, while K remains predominantly bound within stable aluminosilicate structures with minimal evidence of volatilization.

Figure 8.

Proportion of major element oxides in gasification ash.

Correlation analysis provides additional constraints on element behavior. Strong positive correlations between Na2O and K2O with SiO2 and Al2O3 (r = 0.71–0.98; Appendix A Table A5) indicate that both alkali metals are reincorporated into aluminosilicate phases during cooling. CaO and MgO show moderate correlation (r = 0.66), suggesting partial co-precipitation into Ca-Mg-bearing aluminosilicates, although a proportion of Ca is also present in amorphous phases. Fe2O3 correlates positively with MnO but negatively with Na2O and K2O, reflecting its independent mineralogical trajectory dominated by iron oxide formation.

The slagging index (Rs) [79] and fouling index (RfB) [80] were calculated based on the major oxide compositions of the gasification residues following:

A higher Rs indicates a stronger slagging tendency, while a lower RfB suggests a higher fouling propensity associated with alkali and alkaline earth metals.

Overall, these results demonstrate that AAEMs undergo two primary pathways during gasification, volatilization followed by recondensation or re-mineralization (especially for Na), and solid-state reorganization into Ca–Al–Si and Fe-oxide systems. The formation of Na-bearing aluminosilicates and Ca–Fe–Al low-melting phases is particularly significant, as these compounds reduce ash fusion temperatures and enhance the propensity for slagging. The oxide-level changes documented here thus provide quantitative evidence for the chemical drivers of slag formation and complement the mineralogical transformations described earlier, offering an integrated understanding of AAEMs mobility and slagging behavior in high-sodium coals.

5.4. Implications for Slagging and Ash Behavior

The integrated results of elemental redistribution, mineral transformation, and ash chemistry provide a coherent mechanistic framework for understanding the slagging behavior of Naomaohu coal during fixed-bed gasification. Sodium exerts the strongest influence among all AAEMs. Its partial volatilization and subsequent recondensation into Na-bearing aluminosilicates (e.g., Na-feldspars) and halides (NaCl), together with amorphous Na-rich phases, significantly depress ash fusion temperatures. These low-melting Na phases facilitate early liquid-phase formation and strongly enhance slag adhesion and corrosion risks under gasification conditions.

Calcium and iron further intensify slagging tendencies through solid-state reactions. Ca released from carbonate decomposition readily combines with aluminosilicate components to form Ca-Al-Si minerals such as gehlenite, as well as Ca-rich amorphous matrices. Iron, originating from siderite and pyrite, transforms into Fe oxides and participates in forming Ca-Fe-Al phases (e.g., brownmillerite), which possess intrinsically low melting points and promote melt generation. The coexistence of Ca- and Fe-rich phases therefore accelerates slag flow and enlarges the liquid fraction at typical gasification temperatures. In contrast, potassium remains mostly within stable aluminosilicate frameworks, and magnesium plays only a limited role, reflecting their inherently lower reactivity during high-temperature conversion.

Overall, the pronounced slagging propensity of Naomaohu coal arises from two synergistic mechanisms: (i) Na volatilization-condensation cycling that generates eutectic low-melting Na-Al-Si and halide phases, and (ii) Ca and Fe enrichment that drives the formation of low-fusion Ca-Al-Si and Ca-Fe-Al compounds [81]. Acting together, these pathways substantially reduce ash fusion temperatures and increase the likelihood of slag accumulation, deposit growth, and refractory corrosion in industrial gasification systems.

6. Conclusions

This study establishes an integrated geological–geochemical–thermal framework to elucidate the enrichment, migration, and transformation mechanisms of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs) in the Naomaohu coal seam and their implications for slagging behavior during fixed-bed gasification. The major findings and innovations are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Depositional and mineralogical controls: AAEM occurrence, speciation, and mobility are fundamentally governed by coal facies and mineral associations, with clay minerals, feldspars, calcite, and siderite serving as primary carriers. Weak paleoweathering preserves easily alterable minerals, sustaining water-soluble and exchangeable Na.

- (2)

- AAEM migration pathways: During gasification, Na primarily migrates via volatilization–recondensation forming Na-Al-Si and halide phases, while Ca and Fe undergo solid-state reorganization into low-melting Ca-Al-Si and Ca-Fe-Al minerals. These pathways reconstruct the element-mineral network and control slagging behavior.

- (3)

- Mineralogical transformations and slagging precursors: Formation of low-fusion phases, including gehlenite, Ca12Al14O33, and brownmillerite, promotes early liquid-phase formation and strongly influences ash fusion and deposit formation.

- (4)

- Unified slagging mechanism: Na-driven eutectics and Ca-Fe-Al melt networks jointly reduce ash fusion temperatures, defining the slagging propensity of high-Na coal and providing a framework for predicting and managing slagging risks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Y.H.; software and validation, Y.H. and H.Z.; formal analysis, Y.H. and X.G.; data curation, Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, X.G. and Y.T.; funding acquisition, Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42030807, 42102226).

Data Availability Statement

All of the data and models generated or used in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have approved the manuscript for submission and without any potential competing interests.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Proximate analyses of the coals from the Naomaohu Coal (%).

Table A1.

Proximate analyses of the coals from the Naomaohu Coal (%).

| Sample | Mad | Ad | Vdaf | FCd | St,d | Qgr,d | T (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSH-1 | 18.71 | 4.65 | 48.83 | 48.79 | 0.16 | 28.3 | 50 |

| BSH-2 | 18.38 | 4.3 | 48.43 | 49.35 | 0.17 | 28.26 | 40 |

| BSH-3 | 17.34 | 4.89 | 49.2 | 48.32 | 0.15 | 28.23 | 20 |

| BSH-4 | 16.78 | 4.72 | 50.42 | 47.24 | 0.14 | 28.39 | 15 |

| BSH-5 | 18.41 | 5.2 | 48.89 | 48.45 | 0.17 | 27.98 | 20 |

| BSH-6 | 19.12 | 4.71 | 48.9 | 48.69 | 0.16 | 28.12 | 35 |

| BSH-7 | 17.27 | 5.22 | 48.95 | 48.39 | 0.16 | 27.95 | 15 |

| BSH-8 | 18.66 | 5.73 | 48.37 | 48.67 | 0.14 | 27.75 | 15 |

| BSH-9 | 18.13 | 5.47 | 49.27 | 47.95 | 0.16 | 28.12 | 50 |

| BSH-10 | 16.62 | 16.21 | 48.93 | 42.79 | 0.19 | 24.24 | 40 |

| BSH-11 | 16.8 | 5.71 | 50.75 | 46.44 | 0.2 | 28.34 | 40 |

| BSH-12 | 17.49 | 4.98 | 49.03 | 48.43 | 0.16 | 28.29 | 20 |

| BSH-13 | 14.36 | 5.97 | 50.7 | 46.36 | 0.23 | 27.89 | 40 |

| BSH-14 | 14.67 | 5.92 | 52.62 | 44.58 | 0.21 | 28.43 | 35 |

| BSH-15 | 13.36 | 5.97 | 52.6 | 44.58 | 0.18 | 28.29 | 30 |

| BSH-16 | 16 | 5.86 | 49.29 | 47.74 | 0.18 | 27.75 | 25 |

| BSH-17 | 13.86 | 5.73 | 52.51 | 44.76 | 0.21 | 28.6 | 40 |

| BSH-18 | 15.46 | 5.44 | 47.06 | 50.06 | 0.22 | 27.65 | 25 |

| BSH-19 | 14.36 | 5.53 | 50.14 | 47.1 | 0.21 | 28.33 | 30 |

| BSH-20 | 13.83 | 5.64 | 48.9 | 48.22 | 0.19 | 27.99 | 25 |

| BSH-21 | 13.64 | 15.03 | 49.71 | 42.73 | 0.15 | 25.09 | 50 |

| BSH-22 | 13.43 | 6.58 | 50.34 | 46.39 | 0.27 | 27.88 | 30 |

| BSH-23 | 10.61 | 7.41 | 49.31 | 46.94 | 0.18 | 27.42 | 40 |

| BSH-24 | 14.11 | 6.52 | 48.89 | 47.78 | 0.22 | 27.71 | 50 |

| BSH-25 | 14.09 | 7.85 | 49.5 | 46.54 | 0.24 | 27.37 | 50 |

| BSH-26 | 13.59 | 5.69 | 49.72 | 47.41 | 0.24 | 28.27 | 50 |

| BSH-27 | 14.17 | 6.43 | 51.58 | 45.31 | 0.31 | 28.55 | 50 |

| BSH-28 | 13.98 | 9.3 | 49.68 | 45.64 | 0.91 | 27.37 | 50 |

| BSH-29 | 15.84 | 9.2 | 50.75 | 44.72 | 0.24 | 27.44 | 40 |

| BSH-30P | 8.18 | 52.78 | Vd 31.92 | 15.3 | 0.15 | 13.37 | 10 |

| BSH-31 | 13.69 | 11.68 | 51.8 | 42.57 | 0.48 | 27.18 | 50 |

| BSH-32 | 16.22 | 11.64 | 51.05 | 43.26 | 0.27 | 27.53 | 50 |

| BSH-33P | 8.67 | 43.35 | Vd 39.96 | 16.69 | 0.14 | 17. 82 | 30 |

| BSH-34 | 14.05 | 12.29 | 56.65 | 38.02 | 0.38 | 26.95 | 50 |

| BSH-35 | 16.94 | 8.85 | 49.68 | 45.87 | 0.25 | 27.01 | 40 |

| BSH-36 | 17.69 | 11.43 | 50.4 | 43.93 | 0.49 | 26.21 | 40 |

| BSH-37 | 18.72 | 4.93 | 49.07 | 48.41 | 0.23 | 28.32 | 50 |

| BSH-38 | 16.76 | 5.48 | 48.14 | 49.01 | 0.24 | 28.09 | 50 |

| BSH-39 | 18.16 | 5.13 | 48.52 | 48.84 | 0.23 | 28.37 | 50 |

| BSH-40 | 17.28 | 5.1 | 47.31 | 50 | 0.25 | 28.36 | 50 |

| BSH-41 | 11.64 | 7.92 | 60.99 | 35.92 | 0.24 | 29.81 | 6 |

| BSH-42 | 17.08 | 4.85 | 46.2 | 51.19 | 0.24 | 28.19 | 40 |

| BSH-43 | 16.56 | 4.55 | 49.42 | 48.27 | 0.31 | 28.97 | 50 |

| BSH-44 | 15.36 | 5.36 | 50.3 | 47.03 | 0.31 | 28.82 | 50 |

M, moisture; A, ash yield; V, volatile matter; FC, fixed carbon; St, total sulfur; Qgr,d, Gross calorific value at constant volume; T, thickness; ad, air-dried basis; d, dry basis; daf, dry and ash-free basis.

Table A2.

Concentration of major element oxides (%), loss on ignition (LOI) in the samples from the Naomaohu coal.

Table A2.

Concentration of major element oxides (%), loss on ignition (LOI) in the samples from the Naomaohu coal.

| Sample | Si2O | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | MnO | TiO | P2O5 | FeO | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSH-1 | 0.718 | 0.528 | 0.673 | 0.117 | 1.72 | 0.465 | 0.042 | <0.004 | 0.018 | 0.006 | 0.49 | 95.54 |

| BSH-2 | 0.421 | 0.491 | 0.579 | 0.125 | 1.73 | 0.486 | 0.036 | <0.004 | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.43 | 96.03 |

| BSH-3 | 0.582 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.129 | 1.77 | 0.456 | 0.033 | <0.004 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.48 | 95.72 |

| BSH-4 | 0.46 | 0.509 | 0.648 | 0.125 | 1.87 | 0.433 | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.014 | <0.006 | 0.48 | 95.83 |

| BSH-5 | 0.488 | 0.578 | 0.741 | 0.123 | 1.84 | 0.479 | 0.028 | 0.004 | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.57 | 95.68 |

| BSH-6 | 0.527 | 0.565 | 0.633 | 0.129 | 1.76 | 0.500 | 0.037 | <0.004 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.5 | 95.72 |

| BSH-7 | 0.593 | 0.609 | 0.763 | 0.123 | 1.8 | 0.429 | 0.033 | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.57 | 95.59 |

| BSH-8 | 1.46 | 0.737 | 0.906 | 0.136 | 1.92 | 0.437 | 0.043 | 0.007 | 0.029 | 0.011 | 0.74 | 94.27 |

| BSH-9 | 0.905 | 0.7 | 0.694 | 0.128 | 1.71 | 0.446 | 0.036 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 0.49 | 95.25 |

| BSH-10 | 0.934 | 0.75 | 0.845 | 0.133 | 1.77 | 0.479 | 0.041 | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.63 | 94.84 |

| BSH-11 | 1.05 | 0.737 | 0.767 | 0.118 | 1.77 | 0.397 | 0.037 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.57 | 94.98 |

| BSH-12 | 1.03 | 0.599 | 0.76 | 0.131 | 1.82 | 0.427 | 0.044 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.55 | 95.14 |

| BSH-13 | 1.23 | 0.838 | 1.02 | 0.134 | 1.96 | 0.478 | 0.041 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.006 | 0.9 | 94.26 |

| BSH-14 | 0.93 | 0.679 | 0.692 | 0.139 | 1.75 | 0.432 | 0.042 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.53 | 95.24 |

| BSH-15 | 1.33 | 0.792 | 0.9 | 0.133 | 1.91 | 0.428 | 0.044 | 0.008 | 0.027 | <0.006 | 0.76 | 94.33 |

| BSH-16 | 1.19 | 0.718 | 0.931 | 0.149 | 1.86 | 0.555 | 0.052 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.83 | 94.43 |

| BSH-17 | 1.19 | 0.676 | 0.871 | 0.123 | 1.88 | 0.439 | 0.048 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.009 | 0.64 | 94.68 |

| BSH-18 | 0.878 | 0.713 | 0.893 | 0.126 | 1.72 | 0.514 | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.63 | 95.05 |

| BSH-19 | 1.01 | 0.767 | 0.795 | 0.127 | 1.74 | 0.474 | 0.043 | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.59 | 94.9 |

| BSH-20 | 1.15 | 0.806 | 0.705 | 0.114 | 1.71 | 0.525 | 0.035 | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.007 | 0.52 | 94.76 |

| BSH-21 | 1.64 | 1.2 | 0.74 | 0.125 | 1.86 | 0.554 | 0.054 | 0.008 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.57 | 93.63 |

| BSH-22 | 1.34 | 0.964 | 0.848 | 0.126 | 1.93 | 0.468 | 0.046 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.65 | 93.82 |

| BSH-23 | 2.1 | 1.58 | 0.677 | 0.132 | 1.89 | 0.56 | 0.048 | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.006 | 0.54 | 92.96 |

| BSH-24 | 1.36 | 1.16 | 0.637 | 0.12 | 1.84 | 0.566 | 0.049 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.5 | 94.2 |

| BSH-25 | 1.36 | 0.995 | 1.95 | 0.153 | 2.06 | 0.582 | 0.043 | 0.034 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 1.45 | 92.79 |

| BSH-26 | 0.607 | 0.639 | 0.855 | 0.121 | 1.86 | 0.519 | 0.036 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.61 | 95.29 |

| BSH-27 | 1.2 | 0.902 | 0.995 | 0.135 | 1.91 | 0.506 | 0.04 | 0.008 | 0.04 | 0.008 | 0.87 | 94.18 |

| BSH-28 | 2.14 | 1.54 | 1.51 | 0.123 | 1.76 | 0.571 | 0.044 | 0.006 | 0.046 | 0.006 | 1.3 | 92.07 |

| BSH-29 | 3.03 | 1.78 | 0.635 | 0.134 | 1.62 | 0.521 | 0.045 | 0.004 | 0.063 | 0.007 | 0.54 | 92.09 |

| BSH-30P | 28.24 | 14.42 | 2.24 | 0.338 | 1.58 | 0.83 | 0.152 | 0.017 | 0.981 | 0.032 | 1.83 | 51.11 |

| BSH-31 | 3.92 | 2.33 | 1.07 | 0.138 | 1.79 | 0.556 | 0.043 | 0.009 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.75 | 89.93 |

| BSH-32 | 4.6 | 2.5 | 0.565 | 0.13 | 1.75 | 0.568 | 0.032 | 0.006 | 0.081 | 0.006 | 0.47 | 89.73 |

| BSH-33P | 23.73 | 9.93 | 1.04 | 0.265 | 1.49 | 0.601 | 0.128 | 0.007 | 1.000 | 0.024 | 0.87 | 61.67 |

| BSH-34 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 0.772 | 0.121 | 1.92 | 0.63 | 0.044 | 0.005 | 0.088 | 0.008 | 0.57 | 89.15 |

| BSH-35 | 3.34 | 1.68 | 0.557 | 0.133 | 1.71 | 0.601 | 0.052 | <0.004 | 0.046 | 0.006 | 0.47 | 91.8 |

| BSH-36 | 3.3 | 1.41 | 0.975 | 0.13 | 2.71 | 0.57 | 0.042 | 0.008 | 0.058 | 0.007 | 0.82 | 90.77 |

| BSH-37 | 0.62 | 0.581 | 0.576 | 0.143 | 1.79 | 0.504 | 0.049 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.47 | 95.57 |

| BSH-38 | 0.556 | 0.631 | 0.522 | 0.125 | 1.77 | 0.526 | 0.042 | <0.004 | 0.015 | <0.006 | 0.44 | 95.71 |

| BSH-39 | 0.62 | 0.617 | 0.69 | 0.134 | 1.72 | 0.569 | 0.053 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.5 | 95.51 |

| BSH-40 | 0.795 | 0.698 | 0.458 | 0.118 | 1.62 | 0.496 | 0.042 | 0.004 | 0.024 | 0.006 | 0.38 | 95.62 |

| BSH-41 | 4.25 | 0.618 | 0.411 | 0.103 | 1.86 | 0.347 | 0.042 | 0.005 | 0.121 | 0.007 | 0.35 | 92.05 |

| BSH-42 | 0.685 | 0.618 | 0.407 | 0.124 | 1.59 | 0.509 | 0.052 | <0.004 | 0.027 | 0.006 | 0.3 | 95.84 |

| BSH-43 | 0.312 | 0.437 | 0.496 | 0.121 | 1.64 | 0.478 | 0.036 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.39 | 96.33 |

| BSH-44 | 0.894 | 0.682 | 0.571 | 0.126 | 1.67 | 0.484 | 0.057 | <0.004 | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.49 | 95.43 |

Table A3.

Maceral compositions of the Naomaohu coal (Vol%, mineral-free basis).

Table A3.

Maceral compositions of the Naomaohu coal (Vol%, mineral-free basis).

| Sample | T | CT | CD | CG | T-V | F | SF | Ma | ID | T-I | Cut/T-L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSH-1 | N.d. | 28.3 | 51.1 | 1.1 | 80.5 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 4.3 | 4.3 | 13.1 |

| BSH-2 | N.d. | 16.8 | 74.7 | 1.4 | 92.9 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.6 | 1.6 | 4.6 |

| BSH-3 | N.d. | 25 | 55.5 | 1.1 | 81.6 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 5.1 | 5.1 | 9.1 |

| BSH-4 | N.d. | 19.5 | 58.4 | 10.3 | 88.2 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 2.3 | 2.3 | 7.4 |

| BSH-5 | N.d. | 25.8 | 62.4 | 3.9 | 92.1 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.1 | 1.1 | 4.4 |

| BSH-6 | N.d. | 4.1 | 85.8 | 0.6 | 90.5 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 0.9 | 0.9 | 3 |

| BSH-7 | N.d. | 28.1 | 58.9 | 4 | 91 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| BSH-8 | N.d. | 18.7 | 69.2 | 2 | 89.9 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.7 | 1.7 | 6.9 |

| BSH-9 | 0.4 | 8 | 76.1 | 2.8 | 86.9 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 2 | 2 | 9.5 |

| BSH-10 | N.d. | 9.4 | 68.9 | 3.1 | 81.4 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.2 | 1.2 | 8.5 |

| BSH-11 | N.d. | 29.2 | 60.2 | 3.8 | 93.2 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| BSH-12 | N.d. | 15.5 | 66.4 | 3.3 | 85.2 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 3.3 | 3.3 | 8.9 |

| BSH-13 | N.d. | 36.4 | 51.1 | 4.3 | 91.8 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 2.1 | 2.1 | 5.2 |

| BSH-14 | N.d. | 18.9 | 62.6 | 5.3 | 86.8 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.8 | 1.8 | 10.5 |

| BSH-15 | 0.4 | 26.9 | 55.4 | 3.5 | 86.2 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 4.2 | 4.2 | 7.9 |

| BSH-16 | N.d. | 18.5 | 71.3 | 1.2 | 91 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.2 | 1.2 | 7.4 |

| BSH-17 | N.d. | 21 | 55.7 | 1.7 | 78.4 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 3.8 | 3.8 | 16.4 |

| BSH-18 | 0.3 | 15.4 | 63.3 | 0.6 | 79.6 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 5.8 | 5.8 | 12.5 |

| BSH-19 | N.d. | 14.3 | 68.4 | 7.1 | 89.8 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.6 |

| BSH-20 | N.d. | 15.7 | 72.4 | 3.1 | 91.2 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2.3 |

| BSH-21 | N.d. | 12.8 | 66.7 | 3.7 | 83.2 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 4.1 | 4.1 | 2.6 |

| BSH-22 | N.d. | 5.4 | 75.3 | 2.1 | 82.8 | N.d. | 0.7 | N.d. | 1.3 | 2 | 7.9 |

| BSH-23 | N.d. | 9.3 | 72.6 | 3.7 | 85.6 | N.d. | 1.3 | N.d. | 1.4 | 2.7 | 8.3 |

| BSH-24 | N.d. | 26.7 | 55.8 | 4.8 | 87.3 | N.d. | 0.6 | N.d. | 2.1 | 2.7 | 4.3 |

| BSH-25 | N.d. | 11.2 | 48.1 | 3.1 | 62.4 | 3.5 | 10.2 | N.d. | 7.7 | 21 | 8 |

| BSH-26 | N.d. | 16 | 67.1 | 3.8 | 86.9 | 1.7 | 3.2 | N.d. | 4.2 | 9.1 | 3.1 |

| BSH-27 | N.d. | 6.1 | 65.8 | 2.9 | 74.8 | 2.3 | 6.4 | N.d. | 5.8 | 14.5 | 5.9 |

| BSH-28 | N.d. | 23.4 | 55.1 | 6 | 84.5 | N.d. | 0.2 | N.d. | 0.9 | 1.1 | 7 |

| BSH-29 | N.d. | 15.8 | 64.3 | 7.6 | 87.7 | N.d. | 0.3 | N.d. | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| BSH-31 | N.d. | 9.3 | 70 | 3.7 | 83 | N.d. | 1.5 | N.d. | 2.2 | 3.7 | 8.8 |

| BSH-32 | 1.8 | 14.1 | 61.6 | 4.4 | 81.9 | N.d. | 1.3 | N.d. | 1.1 | 2.4 | 9.2 |

| BSH-34 | N.d. | 5 | 73.9 | 5 | 83.9 | 0.4 | 0.7 | N.d. | 0.9 | 2 | 11.8 |

| BSH-35 | N.d. | 26.4 | 53.9 | 4.2 | 54.5 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 0.7 | 0.7 | 14.1 |

| BSH-36 | N.d. | 13 | 65.7 | 3.8 | 82.5 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.8 | 1.8 | 9.2 |

| BSH-37 | N.d. | 8.7 | 75.4 | 4.9 | 89 | N.d. | 0.9 | N.d. | 1.2 | 2.1 | 5.6 |

| BSH-38 | N.d. | 6.5 | 82.6 | 1.2 | 90.3 | N.d. | N.d. | N.d. | 1.4 | 1.4 | 4.1 |

| BSH-39 | N.d. | 3.2 | 82.4 | 1 | 86.6 | N.d. | 0.5 | N.d. | 1.1 | 1.6 | 6.3 |

| BSH-40 | N.d. | 3.1 | 84 | 0.9 | 88 | N.d. | 0.5 | N.d. | 1.6 | 2.1 | 5.3 |

| BSH-41 | N.d. | 3.3 | 64.6 | 4.6 | 72.5 | N.d. | 3.5 | N.d. | 4.6 | 8.1 | 11.9 |

| BSH-42 | N.d. | 25.5 | 60 | 10.1 | 95.6 | N.d. | 0.2 | N.d. | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| BSH-43 | N.d. | 4.1 | 81.7 | 1.1 | 86.9 | 0.3 | 1.6 | N.d. | 2 | 3.9 | 4.7 |

| BSH-44 | N.d. | 13.3 | 71.5 | 2.8 | 87.6 | N.d. | 2.1 | N.d. | 1.5 | 3.6 | 6 |

T, telinite; CT, collotelinite; CD, collodetrinite; CG, Corpogelinite; T-V, total vitrinite; F, fusinite; SF, semifusinite; Ma, macrinite; ID, inertodetrinite; T-I,total inertinite; Cut, cutinite; T-L, total liptinite; N.d., macerals are either absent or did not fall under the intersection of the eyepiece crosshairs, and therefore macerasl in both cases are not involved in point counting.

Table A4.

Correlation analysis between major element oxidation and ash content in Naomaohu coal.

Table A4.

Correlation analysis between major element oxidation and ash content in Naomaohu coal.

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | Fe2O3 | MnO | TiO2 | P2O5 | St,d | Ad | |

| SiO2 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Al2O3 | 0.86 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| MgO | −0.04 | 0.15 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| CaO | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Na2O | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 1.00 | |||||||

| K2O | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.26 | −0.02 | 0.34 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Fe2O3 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |||||

| MnO | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 1.00 | ||||

| TiO2 | 0.89 | 0.64 | −0.25 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | −0.08 | 0.002 | 1.00 | |||

| P2O5 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.003 | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||

| St,d | 0.41 | 0.48 | −0.03 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.41 | −0.004 | 1.00 | |

| Ad | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

Table A5.

Correlation coefficient between major element oxides in gasification ash.

Table A5.

Correlation coefficient between major element oxides in gasification ash.

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | MnO | TiO2 | P2O5 | |

| SiO2 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Al2O3 | 0.66 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Fe2O3 | −0.88 | −0.87 | 1.00 | |||||||

| MgO | −0.35 | 0.43 | −0.04 | 1.00 | ||||||

| CaO | −0.52 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 1.00 | |||||

| Na2O | 0.71 | 0.98 | −0.89 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 1.00 | ||||

| K2O | 0.90 | 0.61 | −0.76 | −0.50 | −0.50 | 0.61 | 1.00 | |||

| MnO | −0.87 | −0.88 | 0.98 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.88 | −0.73 | 1.00 | ||

| TiO2 | 0.67 | −0.05 | −0.28 | −0.83 | −0.83 | −0.01 | 0.72 | −0.27 | 1.00 | |

| P2O5 | 0.84 | 0.39 | −0.58 | −0.63 | −0.63 | 0.41 | 0.95 | −0.53 | 0.84 | 1.00 |

Table A6.

Concentration of major element oxides (%), loss on ignition (LOI), slagging Index (Rs), and fouling Index (RfB) in gasification ash.

Table A6.

Concentration of major element oxides (%), loss on ignition (LOI), slagging Index (Rs), and fouling Index (RfB) in gasification ash.

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | MnO | TiO2 | P2O5 | FeO | LOI | Rs | RfB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSH-10 | 9.41 | 10.97 | 26.22 | 1.05 | 22.21 | 3.63 | 0.036 | 0.426 | 0.266 | 0.019 | 1.16 | 2.75 | 2.43 | 0.39 |

| BSH-21 | 36.81 | 18.73 | 11.66 | 0.767 | 14.09 | 6.36 | 0.205 | 0.219 | 1.13 | 0.048 | 0.67 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 1.71 |

| BSH-23 | 23.93 | 20.96 | 12.31 | 1.16 | 23.55 | 6.97 | 0.094 | 0.203 | 0.298 | 0.021 | 1.83 | 3 | 0.82 | 1.03 |

| BSH-25 | 11.12 | 10.96 | 23.38 | 1.11 | 21.82 | 4.5 | 0.043 | 0.429 | 0.241 | 0.02 | 1.46 | 7.89 | 2.10 | 0.44 |

| BSH-34 | 31.17 | 21.07 | 13.2 | 0.834 | 15.75 | 7.59 | 0.103 | 0.223 | 0.475 | 0.029 | 3.05 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 1.41 |

| BSH-36 | 19.06 | 12.88 | 17.18 | 0.811 | 27.7 | 4.64 | 0.048 | 0.308 | 0.285 | 0.02 | 0.87 | 2.58 | 1.43 | 0.64 |

| BSH-41 | 20.63 | 5.33 | 23.07 | 0.412 | 11.88 | 2.86 | 0.059 | 0.386 | 0.932 | 0.025 | 2.71 | 0.41 | 1.36 | 0.70 |

References

- Tang, Y.G.; Guo, X.; Xie, Q.; Finkelman, R.B.; Han, S.C.; Huan, B.B.; Pan, X. Petrological characteristics and trace element partitioning of gasification residues from slagging entrained-flow gasifiers in Ningdong, China. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 3052–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Qin, S.J.; Li, S.Y.; Wen, H.J.; Lv, D.; Wang, Q.; Kang, S. The migration and mineral host changes of lithium during coal combustion: Experimental and thermodynamic calculation study. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2023, 275, 104298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Tang, Y.G.; Huan, B.B.; Guo, X.; Finkelman, R.B. Mineralogical examination of the entrained-flow coal gasification residues and the feed coals from northwest China. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 3990–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.X.; He, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Z.J.; Liu, J.Z.; Wang, Z.H. Reactions and transformations of mineral matters during entrained flow coal gasification using oxygen-enriched air. J. Energy Inst. 2022, 10, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, N.; Masnadi, M.S.; Roberts, D.G.; Kochanek, M.A.; Ilyushechkin, A.Y. Mineral matter interactions during co-pyrolysis of coal and biomass and their impact on intrinsic char co-gasification reactivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 279, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivula, L.; Oikari, A.; Rintala, J. Toxicity of waste gasification bottom ash leachate. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Duan, Y.Y.; Liu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Mohamed, U.; Zhang, Y.K.; Ren, Z.L.; Shao, Y.F.; Yi, Q.; Shi, L.J.; et al. Life cycle energy-economy-environmental evaluation of coal-based CLC power plant vs. IGCC, USC and oxy-combustion power plants with/without CO2 capture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Guo, L.; Liu, G.N.; Amjed, M.A.; Wang, T.Y.; Qi, H.X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, M. Advanced design, parameter optimization, and thermodynamic analysis of integrated air-blown IGCC power plants. Fuel 2024, 357, 130016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.J.; Lapuerta, M.; Monedero, E. Characterisation of residual char from biomass gasification: Effect of the gasifier operating conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Saxena, V.K.; Sarkar, A.; Banerjee, S.K. Petrographic controls on combustion behavior of inertinite rich coal and char and fly ash formation. Fuel 2014, 128, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.Y.; Su, J.S.; Xu, H.L.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.F.; Zhang, B.; Ni, Z.H. Synergistically effective flotation enrichment of vitrinite by Na removal for high-Na high-inertinite low-rank Zhundong coal. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.A.; Tang, G.T.; Sun, R.J.; Hu, G.T.; Yuan, M.B.; Che, D.F. The correlations of chemical property, alkali metal distribution, and fouling evaluation of Zhundong coal. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Dou, H.Y.; Bai, J.; Kong, L.X.; Feng, W.; Li, H.Z.; Guo, Z.X.; Bai, Z.Q.; Li, P.; Li, W. Effect of phosphorus on viscosity-temperature behavior of high-sodium coal ash slag. Fuel 2023, 343, 127930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Kong, L.X.; Bai, J.; Dai, X.; Li, H.Z.; Bai, Z.Q.; Li, W. The key for sodium-rich coal utilization in entrained flow gasifier: The role of sodium on slag viscosity-temperature behavior at high temperatures. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.X.; Zhang, W.W.; Shen, Y.J.; Luo, S.Y.; Ren, D.D. Progress in the change of ash melting behavior and slagging characteristics of co-gasification of biomass and coal: A review. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 111, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ma, W.C. An experimental study on the effects of adding biomass ashes on ash sintering behavior of Zhundong coal. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 126, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Lv, Q.; Zhao, L.; Che, D.F. Correlations of chemical properties of high-alkali solid fuels: A comparative study between Zhundong coal and biomass. Fuel 2018, 211, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.S.; Zhuo, X.Y.; Zhang, L.F.; Wang, L.; Guo, M.Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, M.L.; Ni, Z.H. Efficient removal behaviors and correlation rules of Na from Zhundong coal with low concentration organic acids. Fuel 2023, 350, 128803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Jin, J.; Zheng, L.Q.; Zhang, R.P.; Wang, Y.Z.; He, X.; Kong, S.; Zhai, Z.Y. Controlling the ash adhesion strength of zhundong high-calcium coal by additives at high temperature. Fuel 2023, 323, 1243422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.Q.; Guan, J.; He, D.M.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, Q.M. The influence of inherent minerals on the constant-current electrolysis process of coal-water slurry. Energy 2023, 285, 128766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.Z.; Yang, Q.W.; Wang, J.Q.; Shen, B.X.; Wang, Z.Z.; Shi, Q.Q.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, C.; Xu, J. The migration and transformation of Pb, Cu, and Zn during co-combustion of high-chlorine-alkaline coal and Si/Al dominated coal. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 141, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Q.; Liao, Q.; Hu, L.T.; Xie, L.H.; Qu, B.L.; Gao, R.X. Effect of removal of alkali and alkaline earth metals in cornstalk on slagging/fouling and co-combustion characteristics of cornstalk/coal blends for biomass applications. Renew. Energy 2023, 207, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.F.; Finkelman, R.B.; French, D.; Hower, J.C.; Graham, I.T.; Zhao, F.H. Modes of occurrence of elements in coal: A critical evaluation. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 222, 103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.R. Analysis, origin and significance of mineral matter in coal: An updated review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 165, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, F.; Esmaeili, A. Mineralogy and geochemistry of the coals from the Karmozd and Kiasar coal mines, Mazandaran province, Iran. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 96–97, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayiğit, A.I.; Oskay, R.G.; Christanis, K.; Tunoğlu, C.; Tuncer, A.; Bulut, Y. Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the Çardak coal seam, SW Turkey. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2015, 139, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.F.; Ren, D.Y.; Chou, C.L.; Finkelman, R.B.; Seredin, V.V.; Zhou, Y.P. Geochemistry of trace elements in Chinese coals: A review of abundances, genetic types, impacts on human health, and industrial utilization. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 94, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.F.; Ji, D.P.; Ward, C.R.; French, D.; Hower, J.C.; Yan, X.Y.; Wei, Q. Mississippian anthracites in Guangxi Province, southern China: Petrological, mineralogical, and rare earth element evidence for high-temperature solutions. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 197, 84–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkoyun, H.; Kadir, S.; Huggett, J. Occurrence and genesis of tonsteins in the Miocene lignite, Tunçbilek Basin, Kütahya, western Turkey. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 202, 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossifova, M.G.; Eskenazy, G.M.; Valčeva, S.P. Petrology, mineralogy, and geochemistry of submarine coals and petrified forest in the Sozopol Bay, Bulgaria. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 87, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayiğit, A.İ.; Oskay, R.G.; Córdoba Sola, P.; Bulut, Y.; Eminaǧaoǧlu, M. Mineralogical and elemental composition of the Middle Miocene coal seams from the Alpu coalfield (Eskişehir, Central Türkiye): Insights from syngenetic zeolite formation. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 282, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.B. The fate of trace elements during coal combustion and gasification: An overview. Fuel 1993, 72, 731−736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Ma, T.D.; Tang, Y.G.; Gupta, R.; Schobert, H.; Zhang, J.Y. Thermal transformation of coal pyrite with different structural types during heat treatment in air at 573–1473k. Fuel 2022, 327, 124918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.H.; Zhang, S.Y.; Tu, S.K.; Jin, T.; Shi, D.Y.; Pei, Y.F. Transformation of sodium during Wucaiwan coal pyrolysis. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2012, 42, 1190–1196. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.Y.; Wang, C.; Yan, Y.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y.H.; Che, D.F. Release and transformation of sodium during pyrolysis of Zhundong coals. J. Energy Inst. 2016, 89, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Zhang, H.X. Gasification characteristics and sodium transformation behavior of high-sodium Zhundong coal. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 6435–6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, J.; Wei, X.L. Research progress of alkali metals release characteristics during thermal utilization of high-alkali coals. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 51, 92–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bläsing, M.; Müller, M. Release of alkali metal, sulphur, and chlorine species from high temperature gasification of high- and low-rank coals. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 106, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Tang, Y.G.; Wang, Y.F.; Eble, C.F.; Finkelman, R.B.; Li, P.Y. Evaluation of carbon forms and elements composition in coal gasification solid residues and their potential utilization from a view of coal geology. Waste Manag. 2020, 114, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.P.; Li, X.; Wei, B.; Tan, P.; Fang, Q.Y.; Chen, G.; Xia, J. Release and transformation characteristics of Na/Ca/S compounds of Zhundong coal during combustion/CO2 gasification. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Jin, J.; Liu, D.Y.; Yang, H.R.; Li, S.J. Understanding Ash Deposition for the Combustion of Zhundong Coal: Focusing on Different Additives Effects. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 7103–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.L.; Yang, S.B.; Song, W.J.; Qi, X.B. Release and transformation behaviors of sodium during combustion of high alkali residual carbon. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 122, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.H.; Cui, B.; Chen, Y.; Yang, T.H.; Guo, L.Z. Occurrence of sodium in high alkali coal and its transformation during combustion. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2019, 47, 897–906. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B.; Xu, Z.X.; Wei, B.; Zhang, L.; Tan, H.Z.; Yang, T.; Mikulčić, H.; Duić, N. The ash deposition mechanism in boilers burning Zhundong coal with high contents of sodium and calcium: A study from ash evaporating to condensing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 80, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.B.; Song, G.L.; Yang, S.B.; Yang, Z.; Lyu, Q.G. Migration and transformation of sodium and chlorine in high-sodium high-chlorine Xinjiang lignite during circulating fluidized bed combustion. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wei, B.; Tian, J. Characteristics of Coal Ouality and Coal Facies of Middle-Lower Jurassic CoalSeam in Large Ready Coalfield of the Santanghu Basin, Hami, Xinjiang. Acta Geol. Sin. 2015, 89, 917–930. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.N.; Zhou, J.M.; Jiao, L.X.; Sun, B.; Huang, Y.Y.; Huang, D.F.; Zhang, J.L.; Shao, L.Y. Coalbed Methane Enrichment Regularity and Model in the Xishanyao Formation in the Santanghu Basin, NW China. Minerals 2023, 13, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.Z.; Huang, S.Q.; Du, F.P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Zhu, S.F. Characteristics and origin of high quality direct liquefaction coal of A4 coal seam in Naomaohu coalfield, Xinjiang Province. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 251–262. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.W.; Zheng, J.J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.H. Paleozoic Structural Evolution of Santanghu Basin and Its Surrounding and Prototype Basin Recovery. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2010, 21, 947–954. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.Q.; Wang, C.H.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhang, S.J. Distribution and Fate of Trace Elements during Fixed-Bed Pressurized Gasification of Lignite. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 9061–9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]