Abstract

The Micangshan lead–zinc deposits, located in the northern margin of the Sichuan Basin, are classified as the Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) deposits. This study investigates the genetic linkage between Pb–Zn mineralization and paleo-oil reservoirs in the region, which is distinct from separate investigations on lead–zinc deposits or paleo-oil reservoirs. Through mineralogy, isotope, and fluid inclusion analyses, it is revealed that the direction of ore-forming fluid migration and the ore-forming process are closely related to the thermal cracking of paleo-oil reservoirs. The deposits show a characteristic clustered distribution along the southern part of the Micangshan area, with high-grade mineralization concentrated in the Nanmushu and Kongxigou Pb–Zn deposits. Rb–Sr isotopic dating indicates that mineralization occurred during the Late Cambrian to Early Ordovician (Nanmushu deposit 486.7 ± 3.1 Ma; Kongxigou deposit 472 ± 6.1 Ma), coinciding with the formation of the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs. The study concludes that the MVT Pb–Zn mineralization in the Micangshan area is genetically linked to the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs’ hydrocarbon generation and migration events. The organic-rich hydrothermal fluids facilitated the migration and precipitation of Pb–Zn minerals.

1. Introduction

There is increasing evidence that hydrocarbon accumulation is closely associated with metallic ore mineralization in sedimentary basins, especially in Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) deposits within carbonate environments [1,2,3,4,5,6]. MVT deposits are a major contributor to the world’s lead–zinc resources, accounting for 27% of global Pb–Zn reserves [7,8]. The MVT deposit is an epigenetic stratified Pb–Zn deposit with carbonate rock as its host rock and no apparent relation with magmatic activity [8]. This type of deposit is widely distributed worldwide, but the most classic deposits are located in the Mississippi River of the United States and the lead–zinc ore concentration area of northern Canada [7,9]. The MVT Pb–Zn deposit exhibits a characteristic clustered distribution pattern. Over 400 deposits (approximately 20 million tons) were discovered in Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou Provinces of China [9]. The relationship between the MVT deposits and the oil and gas reservoir is spatiotemporal, indicating that the Pb–Zn mineralization is genetically related to oil and gas accumulation [10,11,12]. The MVT lead–zinc deposit and the oil and gas reservoir have the same material source [12,13], or the oil and gas reservoir can provide reduced sulfur for the lead–zinc mineralization [11,14,15], and the oil and gas reservoir can promote the migration of ore-forming material [11].

The Micangshan lead–zinc deposit is classified as an MVT-type deposit, and it is one of several deposits distributed in the east-west structural belt of the Micangshan area [12]. The ore is hosted by dolomitic carbonate rocks of the Dengying Formation. Additionally, bitumen, formed through the thermal cracking of paleo-oil reservoirs in the lead–zinc deposit, exhibits a close association with lead–zinc mineralization. It has become a consensus that organic matter is involved in lead–zinc mineralization [16,17]. Previous studies on Micangshan MVT Pb–Zn deposits have investigated hydrocarbon accumulation mechanisms, while others have analyzed the Pb–Zn mineralization systems through the framework of petroleum geology [12]. Studies have examined the spatiotemporal correlation between MVT lead–zinc deposits and paleo-oil/gas reservoirs, including their distribution patterns and metallogenic timing characteristics [12,18,19]. Nevertheless, current research has not comprehensively explored the genetic correlation between Pb–Zn mineralization systems and hydrocarbon accumulation processes, along with the direction of fluid migration. Consequently, this impedes a thorough comprehension of the formation mechanisms of MVT deposits.

2. Geological Setting

2.1. Regional Geology

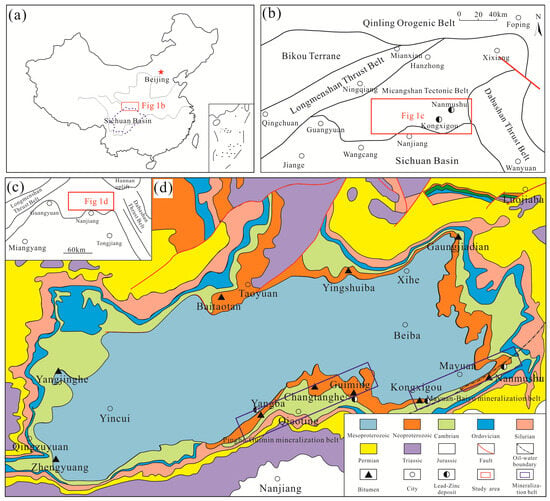

The Micangshan area occupies a critically important tectonic position along the northern margin of the Sichuan Basin (Figure 1a), serving as a transitional zone between the Sichuan Basin and the Qinling Orogenic Belt. The Micangshan area is structurally bounded by the Hannan Uplift to the north, the Sichuan Basin to the south, the northwestern Dabashan Thrust Belt to the east, and the northeastern Longmenshan Thrust Belt to the west (Figure 1b). The study area has undergone multiple tectonic events, and its structural characteristics are extremely intricate [20].

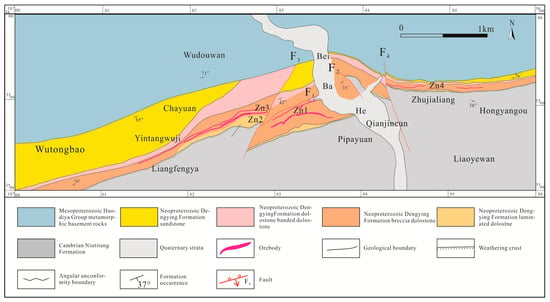

Figure 1.

Sketch map of the geotectonic location of the Micangshan lead–zinc deposits. (a) Location of the Sichuan Basin. (b) Location of the study area in the Sichuan Basin [21]. (c) Location of the study area in the Micangshan Tectonic Belt. (d) Geological map of the Micangshan lead–zinc deposits [22].

2.2. Geology of the Pb–Zn Deposit

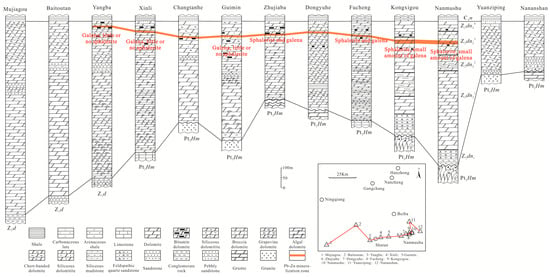

There are many lead–zinc deposits in the Micangshan area, which all occur in fractured dolomite of the Dengying Formation, and many bitumen-associated phenomena can be observed. These mineralized zones form an annular belt surrounding the Micangshan uplift, with preferential distribution along the southern margin (Pinghe–Guimin area, Nanjiang, Sichuan Province) and southeastern margin (Mayuan–Baiyu area, Hanzhong, Shaanxi Province) [23]. The spatial distribution of the lead–zinc ore deposit in the Micangshan area is shown in Figure 1d and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution characteristics of lead–zinc deposits and bitumen of Dengying Formation in the southern margin of the Micangshan area. The column diagram of Mujiagou, Baitoutan, Guimin, Zhujiaba, Dongyuhe, Yuanziping, and Nananshan Dengying Formation was modified from Chen et al. [23]. The column diagram of Yangba, Xinli, and Fucheng Dengying Formation was modified from Long [24]. The column diagram of Nanmushu Dengying Formation was modified from Shi [25].

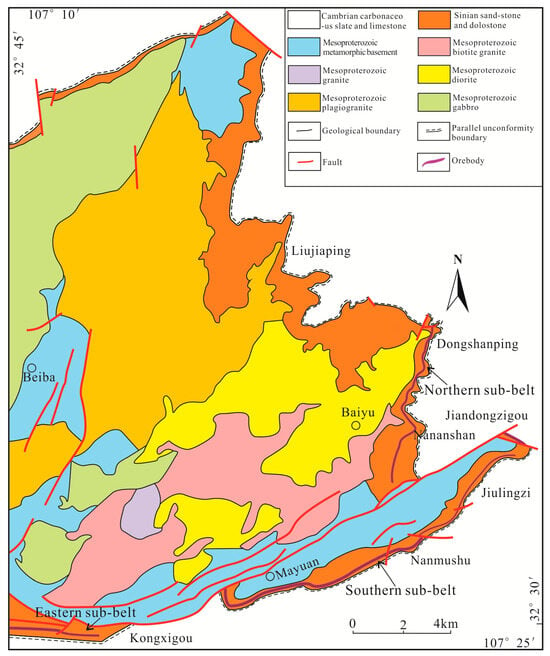

The Pinghe–Guimin mineralization belt hosts predominantly lead–zinc mineralization sites, exemplified by the Yangba, Xinli, and Guimin (Figure 1d). In contrast, the Mayuan–Baiyu mineralization belt exhibits a distinct spatial configuration (Figure 3), concentrated within the Mayuan district, where it extends approximately 60 km in length with variable widths of 10–200 m [26]. The Mayuan–Baiyu mineralization belt comprises three sub-belts (southern, eastern, and northern), collectively containing over 40 lead–zinc ore bodies. The southern sub-belt, distinguished by the most abundant resource endowment, stretches approximately 20 km along the southern Micangshan district, encompassing the areas of Kongxigou, Lengqingpo, Nanmushu, Jiulingzi, and Jiandongzigou. This sub-belt hosts the extensively studied Nanmushu and Kongxigou deposits, which represent typical deposits in the Micangshan area. The eastern sub-belt exhibits a north-south trend along the Liujiaping–Songping–Jiuwanzi–Dongshanping–Nananshan area, whereas the northern sub-belt presents an east–west orientation within the Xihe–Madiping region (Figure 3). Notably, although lead–zinc mineralization persists across all sub-belts, economically significant Pb–Zn deposits are exclusively developed in the southern sub-belt, with the eastern and northern sub-belt exhibiting only diffuse mineralization [26].

Figure 3.

Geological map of the Mayuan district showing the distribution of the mineralization belt (modified from [27]).

2.2.1. Nanmushu Lead–Zinc Deposit

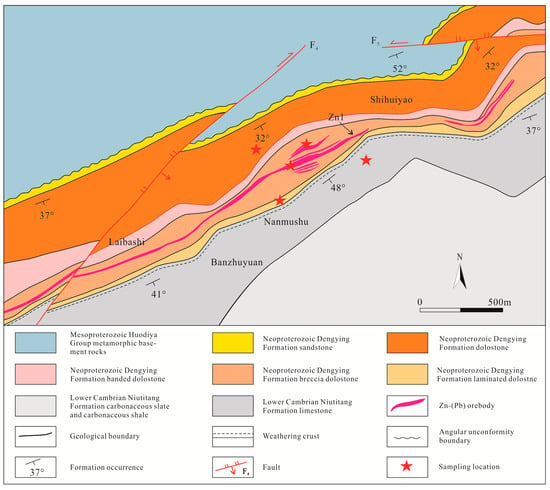

The Nanmushu lead–zinc deposit, situated within the central segment of the southern mineralization sub-belt in the Mayuan–Baiyu mineralization belt. Zinc mineralization predominates, with subordinate occurrences of lead and lead–zinc ore bodies. The Zn1 orebody, representing the largest mineralized entity in the deposit, extending approximately 1580 m along strike, attains a maximum thickness of 21.36 m (average 9.97 m) [28]. All identified Pb–Zn ore bodies demonstrate strict structural control by fracture zones within brecciated dolomite of the Dengying Formation, clustering along and adjacent to the F2 fault system. Localized ore shoots and thickness anomalies occur where mineralization intensifies, correlating with abrupt increases in ore body dimensions and metal grades. Despite post-mineralization tectonic modifications, the ore bodies retain strong continuity both along strike and down-dip within the Dengying Formation sequence (Figure 4). Structural disruptions are limited to localized displacements, preserving the overall integrity of the mineralization system.

Figure 4.

Geological map of the Nanmushu lead–zinc deposit (modified from [29]).

2.2.2. Kongxigou Lead–Zinc Deposit

The Kongxigou deposit is distributed across the Wutongbao–Kongxigou-Hongyangou (Figure 5), characterized by a northeast–east (NEE) trending mineralization belt extending 6 km in length with widths varying from 60 to 350 m. Six zinc-dominated ore bodies occur within brecciated dolomite of the Dengying Formation, comprising four large-scale zinc ore bodies and two smaller occurrences (one zinc and one lead–zinc). The primary Zn1 orebody, situated centrally within the deposit, crops out on the southern slope adjacent to Kongxigou Valley (west of the Beiba River) and extends beneath the surface along a strike of 45° to 55° and down-dip. This stratiform body exhibits structural concordance with the host sequence but suffers significant near-surface weathering due to shallow burial depths (10–50 m), manifesting as extensive oxidation zones and weathering profiles beneath dense vegetation.

Figure 5.

Geological map of the Kongxigou lead–zinc deposits.

The Zn1 orebody is located in the central part of the deposit. It is exposed on the southern slope near Kongxigou (west of the Beiba River) and extends underground in a north-dipping direction at the foot of the northern slope. This stratiform orebody shows structural conformity with the host strata, with a dip angle ranging from 45° to 55°. Nevertheless, owing to its shallow burial depth (ranging from 10 m to 50 m), it has experienced extensive surface oxidation and erosion, which is further compounded by a dense vegetative cover. The Zn2 and Zn3 orebodies on Kongxigou’s northern slope exhibit south-dipping stratiform geometries with strong continuity along both strike and dip directions. The Zn4 orebody at Zhujialiang (north of Hongyangou) shows westward stratiform truncation, likely attributable to post-mineralization fault displacement.

2.3. Geology of the Oil Reservoirs

Bitumen serves as direct evidence of paleo-oil reservoirs and provides critical insights for hydrocarbon exploration [22]. In the Micangshan area, bitumen is extensively developed within the Dengying Formation (Figure 1d), hosted in dolomitic pores, vugs, fractures, and along the unconformity interface between the Dengying and Guojiaba Formation. Field investigations validate that bitumen is exposed at 12 localities distributed across the southern (Yangba, Changtanhe, Huitan), southeastern (Zhujiaba, Kongxigou, Nanmushu, Jiantongzigou), eastern (Guangjiadian), northern (Baitoutan, Yingshuiba), and western (Yanjinghe, Zhengyuan) regions of the Micangshan area. Quantitative analysis of stratigraphic sections reveals bitumen-bearing intervals with thicknesses ranging from 1.8 to 48.7 m (mean: 28.9 m), covering an aerial extent of ~8552 km2 across Micangshan and adjacent regions [22]. These metrics strongly support the existence of a substantial paleo-oil reservoir within the Dengying Formation [4,22].

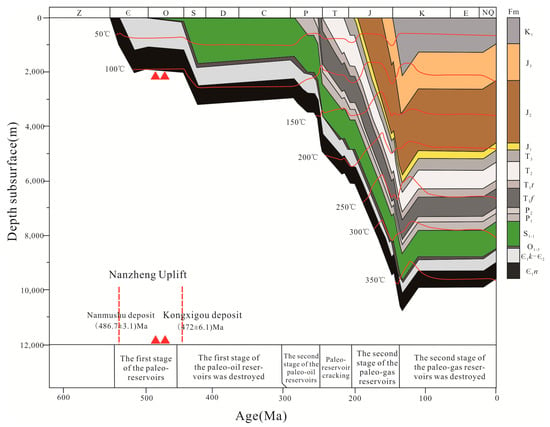

Burial history modeling constrained by stratigraphic thicknesses, lithologic variations, and unconformity surfaces (Figure 6) identifies three critical hydrocarbon generation phases: (1) Early Middle Cambrian: Initial maturation of source rocks. (2) Ordovician–Middle Silurian: Primary hydrocarbon expulsion. (3) Early Permian–Late Jurassic: Peak thermal cracking of accumulated oils. The model suggests two discrete paleo-oil reservoirs formation events, both subsequently compromised by multistage tectonic reactivation. Post-Cretaceous uplift induced reservoir breaching, leaving only bitumen remnants within the Dengying Formation.

Figure 6.

Burial history and ages of mineralization on the north margin of the Sichuan Basin (modified from [20]).

3. Sampling and Methods

Representative samples from the Micangshan Pb–Zn deposits underwent surface cleaning to minimize contamination before the analysis. Mineralogical characterization focused on paragenetic stages of the Nanmushu and Kongxigou deposits using polished thin sections examined under a Nikon microscope (20× objective, Nikon LV100POL) at Chengdu University of Technology.

Carbon-coated specimens from Nanmushu and Kongxigou deposits were analyzed via SEM-EDS (Quanta 250 FEG; Inca X-max 20) at the State Key Laboratory of Reservoir Geology and Development Engineering (Chengdu University of Technology) to resolve textures and compositions of sphalerite, galena, pyrite, and bitumen phases.

Seven samples were crushed to 40–80 mesh for hand picking under a binocular microscope to guarantee the purity of single mineral separates (>99%). All mineral separates were crushed to <200 mesh in an agate mortar. Then, the samples were washed with ultrapure water in an ultrasonic bath to remove salts from the opened fluid inclusions. The Rb–Sr isotopic measurements of the samples were conducted using the Phoenix TIMS instrument at the Analysis and Test Research Center of Beijing Institute of Geology. Chemical treatment is carried out in the center’s high-level ultra-clean isotope chemistry laboratory with a national patent right. The measured 87Sr/86Sr ratio of the NBS-987 standard was 0.710224 ± 8 (N = 10), and all isotopic compositions were normalized to a value of 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194. Total procedural blanks were <3 × 10−9 g for Sr. The mineral samples were digested and dissolved into clear liquid after using different dilute and concentrated ultrapure HCl-HNO3 mixed acids and dilute and concentrated ultrapure H2SO4-HNO3-HClO4 mixed acids for multiple gradient leaching and were then evaporated and dissolved into clear liquid with acid. The solution was divided into two: one sample for the determination of isotope ratio (without Rb–Sr isotope diluent) and the other sample for the determination of isotope abundance (with ultrapure Rb–Sr isotope diluent). The Rb–Sr isochron ages were calculated using the internationally recognized program ISOPLOT [30]. The calculated 87Rb/86Sr ratios and 87Sr/86Sr ratios of the measured samples have accuracies of better than 1% and 0.005%, respectively. Details of the Rb–Sr chemical preparation, mass spectrum determination method, and the results of all standard sample analyses can be found in the literature of Wang et al. [31].

Fluid inclusion studies targeted 50 samples across mineralization stages in Nanmushu and Kongxigou deposits. Petrographic screening of inclusions hosted in dolomite, quartz, barite, calcite, and sphalerite utilized a Nikon microscope (50× objective). The petrographic observation and microthermometric measurements of Fluid inclusion were carried out at the Key Laboratory of Structural Metallogenesis and Reservoir-Formation (Chengdu University of Technology). Laser Raman spectroscopy (Renishaw RW1000) at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources (China University of Geosciences, Wuhan), with 514.5 nm excitation wavelength, 22 mW laser power, and 25 μm slit width, maintaining consistent analytical parameters across all sessions.

4. Results

4.1. Mineralogy

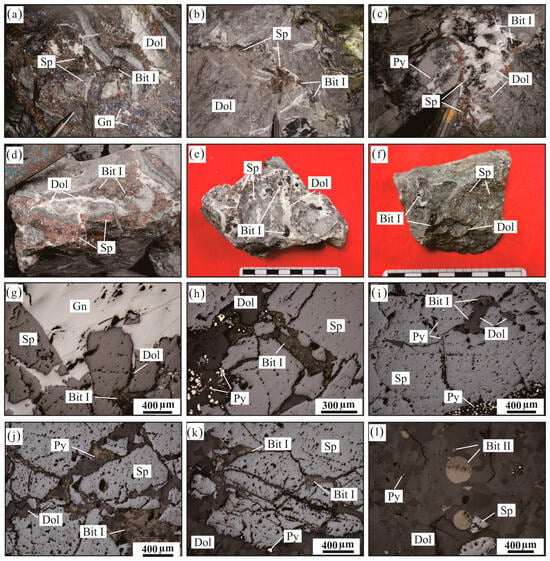

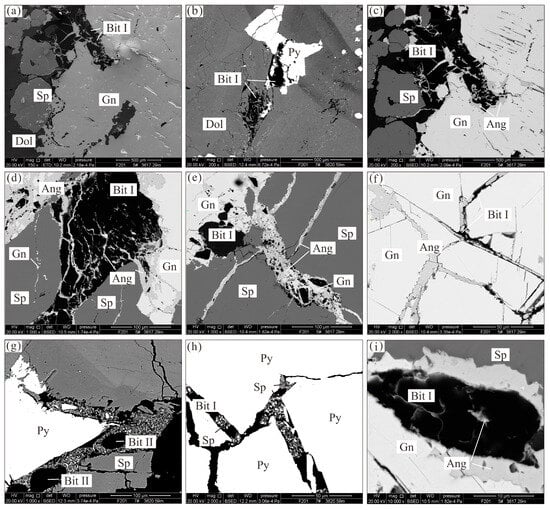

The Nanmushu and Kongxigou deposits in the Micangshan area exhibit a simple mineral assemblage (Figure 7a–f and Figure 8a–f). The ore minerals predominantly consist of sphalerite, accompanied by minor quantities of galena and pyrite. Gangue minerals are dominated by dolomite, followed sequentially by barite, quartz, and bitumen, with subordinate calcite occurring sporadically. Notably, the bitumen represents the residual product of thermal cracking from paleo-oil reservoirs.

Figure 7.

Mineral paragenesis of the Nanmushu zinc–lead deposit. (a–f) Field pictures show the symbiosis of sphalerite, galena, pyrite, and bitumen. (g–l) Photomicrographs of the samples showing the mineral associations. Sp = Sphalerite; Py = Pyrite; Dol = Dolomite; Bit I = Stage I bitumen; Gn = Galena; Bit II = Stage II bitumen.

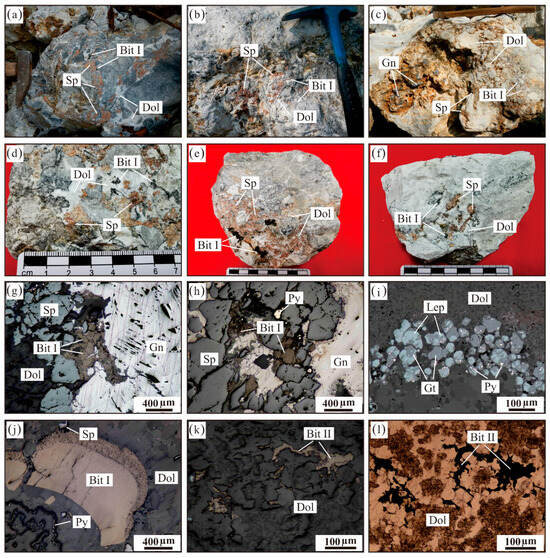

Figure 8.

Mineral paragenesis of the Kongxigou zinc–lead deposit. (a–f) Field pictures show the symbiosis of sphalerite, galena, pyrite, and bitumen. (g–l) Photomicrographs of the samples showing the mineral associations. Sp = Sphalerite; Py = Pyrite; Dol = Dolomite; Bit I = Stage I bitumen; Gn = Galena; Bit II = Stage II bitumen.

Microscopic observations reveal that bitumen, sphalerite, galena, and pyrite occupy interstices between brecciated dolomite (Figure 7g–k and Figure 8g,h). Bitumen exhibits two distinct paragenetic relationships: (1) Stage I bitumen, characterized by fine-grained textures, displays intimate spatial associations with sulfide mineralization. It manifests as rims or belts encircling sphalerite and galena (Figure 7g–k), or bitumen is distributed along fractures within sphalerite (Figure 8g,h), which implies a coeval formation process. (2) Stage II bitumen, comprising coarser-grained anhedral aggregates, predominantly fills dolomite vugs, dissolution pores, and fractures without direct contact with sulfides (Figure 7l and Figure 8j–l). Morphologically, Stage I bitumen is characterized by fine-grained, irregular to reticulated vein networks exhibiting direct association with sulfide mineralization, whereas Stage II bitumen occurs as coarse, irregular to subrounded aggregates spatially isolated from sulfides. Therefore, the Dengying Formation in the study area demonstrates a genetic association between lead–zinc mineralization and Stage II bitumen.

4.2. Microscopic Composition of Ore Minerals

Sphalerite, galena, and Stage I bitumen exhibit cross-cutting, interstitial, and intergrown relationships (Figure 9). Sphalerite (Figure 9a,c) and galena veinlets (Figure 9b–d,i) are embedded within Stage I bitumen matrices, while submicron galena and bitumen fragments occur along sphalerite fracture networks (Figure 9f). Stage II bitumen, despite its coarse-grained texture and occasional subhedral morphologies, shows no micron-scale sulfides based on SEM-EDS mapping (Figure 9g). Partial oxidation of galena to secondary anglesite (PbSO4, Ang) is observed along fracture systems (Figure 9c–e), including galena veins within Stage I bitumen (Figure 9d,i).

Figure 9.

Backscattering images of sphalerite, galena, and bitumen in the Micangshan area. (a–d) Backscattering image of the Nanmushu deposit. (e–i) Backscattering image of the Kongxigou deposit. Sp = Sphalerite; Py = Pyrite; Dol = Dolomite; Bit I = Stage I bitumen; Gn = Galena; Bit II = Stage II bitumen.

The symbiotic intergrowth of micron-scale Pb–Zn sulfides within Stage I bitumen matrices, characterized by mutually embayed “sulfide–bitumen” microtextures (Figure 9a–f), constitutes diagnostic evidence for syngenetic relationships between Zn-Pb mineralization and paleo-oil reservoirs. Nevertheless, sulfide distribution heterogeneity persists. Stage I bitumen domains are devoid of resolvable sulfide inclusions under SEM-EDS, while Stage II bitumen universally lacks sulfide mineralization (Figure 9g). This spatial-temporal decoupling suggests prolonged formation of Stage I bitumen relative to shorter-duration Pb–Zn mineralization events. Consequently, metal sulfides are selectively associated with early hydrocarbon migration phases but are absent in later-stage bitumen formed during post-mineralization periods.

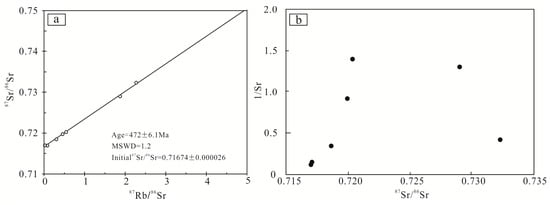

4.3. Rb–Sr Isotope

The Rb–Sr isotopic results of sphalerite and galena from lead–zinc deposits in the Micangshan area are shown in Table 1. The (87Sr/86Sr)i values of the galena and sphalerite in the lead–zinc deposits range from 0.700955 to 0.71709, with an average of 0.71319. The (87Sr/86Sr)i values range from 0.710931 to 0.736468, with an average of 0.72037.

Table 1.

Rb–Sr isotopic results of sphalerite and galena from Kongxigou lead–zinc deposits in the Micangshan area.

The Rb–Sr isotope systematics of sphalerite and galena from the Kongxigou Pb–Zn deposit (Table 1) yield a robust geochronological framework through Isoplot 4.0 regression analysis. The calculated isochron age of 472 ± 6.1 Ma (MSWD = 1.2; Figure 10a) corresponds to the Late Cambrian–Early Ordovician transition, with an initial 87Sr/86Sr ratio of 0.71674 ± 0.000026. Previous research has indicated that the 1/Rb-87Sr/86Sr diagram can be utilized to ascertain the validity of an isochron. Typically, points in the diagram that exhibit a positive linear correlation are indicative of mixed lines, whereas points that display a nonlinear correlation possess isochron significance [32,33,34,35]. Critical validation of isochron reliability was performed using 1/Rb-87Sr/86Sr systematics (Figure 10). The absence of linear correlation in this parameter space confirms the dataset’s compliance with closed-system behavior, excluding mixing line artifacts that typically produce spurious linear arrays. This methodological verification substantiates the 472 ± 6.1 Ma age as representing true mineralization timing rather than fluid mixing events.

Figure 10.

(a) Rb–Sr isochron ages and initial Sr isotopic compositions for the Kongxigou lead–zinc deposit. (b) Diagram of 1/Rb-87Sr/86Sr of Kongxigou lead–zinc deposit.

4.4. Fluid Inclusions

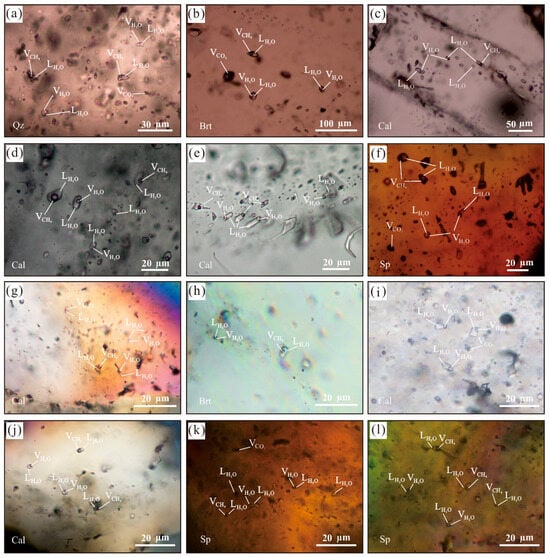

4.4.1. Fluid Inclusions Petrography

The Nanmushu deposits exhibit well-developed transparent minerals (quartz, calcite, barite, and dolomite) and honey-colored sphalerite, the latter attributed to its minor Fe content. A systematic study of fluid inclusions in quartz, barite, calcite, and sphalerite from the sphalerite-galena-barite mineralization stage reveals distinct characteristics. Primary inclusions (3–25 μm) display dispersed distributions dominated by negative crystal and oval morphologies, with subordinate irregular forms. Secondary inclusions (1–6 μm), typically smaller than primary ones, predominantly exhibit rounded or irregular shapes arranged in linear arrays or clusters along microfractures, interpreted as post-formational hydrothermal products. Four types of inclusions were identified at ambient temperature (25 °C): liquid-rich (L-type), vapor-rich (V-type), pure liquid-phase (ML-type), and pure vapor-phase (MV-type) inclusions (Figure 11a–f). L-type inclusions (5–25 μm), representing the dominant primary type across mineralization stages, occur as negative crystalline, ellipsoidal, or irregular forms lacking daughter minerals. These two-phase inclusions contain 60–90 vol% liquid that homogenizes to the liquid phase upon heating and are ubiquitous in quartz, barite, calcite, and sphalerite. V-type inclusions (5–15 μm) consist of >65 vol% vapor with minor liquid fractions. ML-type and MV-type inclusions (3–10 μm) constitute approximately 5% of the total population.

Figure 11.

Fluid inclusions characteristics of the lead–zinc deposit in the Micangshan area. (a–f) Fluid inclusions characteristics of the Nanmushu zinc-lead deposit. (g–l) Fluid inclusions characteristics of the Kongxigou zinc-lead deposit. Qz = Quartz; Brt = Barite; Cal = Calcite; Sp = Sphalerite.

The fluid inclusion assemblages in transparent gangue minerals (quartz, barite, calcite) and translucent sphalerite from the Kongxigou lead–zinc deposit demonstrate comparable features to those documented in the Nanmushu deposit (Figure 11g–l). Primary inclusions (3–20 μm), predominantly exhibiting negative crystalline and ellipsoidal morphologies, are well-developed in calcite, barite, and sphalerite. Secondary inclusions, typically smaller than primary counterparts (<5 μm), occur as linear arrays along microfractures, suggesting late-stage hydrothermal activity. At ambient temperature (25 °C), the inclusion population comprises predominantly liquid-rich (L-type) inclusions with subordinate pure vapor-phase (MV-type) and pure liquid-phase (ML-type) varieties (Figure 11g–l). The dominant L-type inclusions (3–25 μm), present across all mineralization stages in quartz, calcite, and sphalerite, display negative crystalline, ellipsoidal, and irregular shapes. These two-phase inclusions homogenize to the vapor phase upon heating, indicating liquid–vapor coexistence under formation conditions. MV-type and ML-type inclusions (3–10 μm), representing <10% of the total population, maintain monophasic characteristics at room temperature with negative crystal and ellipsoidal morphologies.

4.4.2. Microthemometry

The microthermometric data for fluid inclusions in the hydrothermal period are summarized in Table 2. In the hydrothermal period, fluid inclusions are identified in barite, sphalerite, and quartz. The hosted minerals of the hydrothermal period are predominantly composed of L-type fluid inclusions (FIs). These FIs homogenize to the liquid phase at temperatures ranging from 133.1 to 303.7 °C in barite, from 138.6 to 253.7 °C in quartz, and from 162.1 to 192.0 °C in sphalerite.

Table 2.

Microthemometric characteristics of the Nanmushu and Kongxigou Pb–Zn deposit.

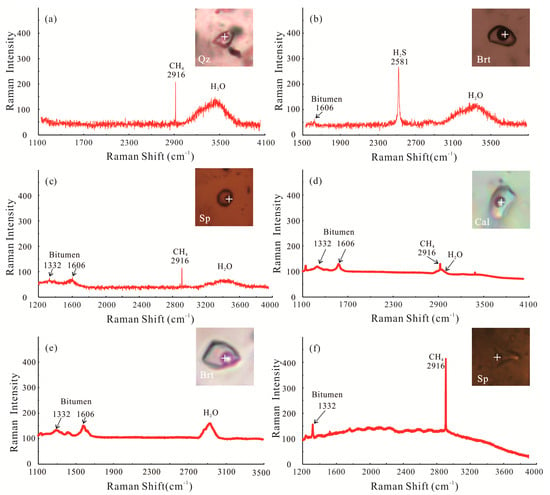

4.4.3. Laser Raman Spectroscopic Analysis

Primary inclusions from sphalerite, barite, calcite, and quartz associated with the sphalerite-galena-barite mineralization stage in both Nanmushu and Kongxigou deposits were analyzed via Laser Raman spectroscopy at ambient temperature (25 °C). Spectral results (Figure 12) reveal the liquid phase is dominated by H2O, though some inclusions display attenuated H2O signals (Figure 12c–e). The vapor phase contains CH4 (Raman peak at 2916 cm−1; Figure 12a–d,f) and trace H2S (Raman peak at 2586 cm−1; Figure 12b). Notably, primary sphalerite inclusions host solid bitumen, identified by characteristic Raman vibrations at 1332 cm−1 and 1606 cm−1 (Figure 12b–f). These findings collectively demonstrate that the ore-forming fluids in the Micangshan lead–zinc deposits represent a NaCl-H2O system enriched with organic components, as evidenced by the coexistence of CH4, H2S, and bitumen. The persistent association of hydrocarbon phases with sulfide and sulfate mineralization strongly supports the participation of organic fluids during the crystallization of sphalerite, barite, calcite, and quartz, thereby confirming organic involvement in the Pb–Zn metallogenic process.

Figure 12.

Representative Raman spectroscopy for fluid inclusions from the Nanmushu lead–zinc deposit. (a–c) Raman spectral characteristics of primary inclusions in Nanmushu lead–zinc deposit. (d–f) Raman spectral characteristics of primary inclusions in Kongxigou lead–zinc deposit. Qz = Quartz, Brt = Barite, Sp = Sphalerite.

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatial Relationship Between Paleo-Oil Reservoirs and Pb–Zn Deposits

The MVT Pb–Zn deposits in the Micangshan district are mainly concentrated in the southern part (Figure 1d, Figure 2 and Figure 3). These deposits are stratigraphically constrained to lenticular dolomite beds within the Dengying Formation, where mineralization predominantly occurs as fracture-fill and cementation textures within breccia dolomite matrices. Notably, breccia clasts lack sulfide mineralization or hydrocarbon residues from paleo-oil reservoir thermal alteration. The primary concentration of Pb–Zn deposits, or mineralization sites, can be found in Pinghe-Guimin, Nanjiang, Sichuan Province, and Mayuan-Baiyu, Hanzhong, Shaanxi Province.

The Dengying Formation in the Micangshan district preserves bitumen distributions derived from thermal degradation of paleo-oil reservoirs, exhibiting planar continuity but variable effective thicknesses ([22]; Figure 2). Pb–Zn mineralization exhibits distinct spatial confinement, being predominantly concentrated along the southern and southeastern regions. A systematic E–W zonation of ore mineral assemblages is evident across principal deposits (Nanmushu → Kongxigou → Fucheng → Zhujiaba → Guimin → Xinli → Yangba). However, it is worth noting that the distribution area of the paleo-oil reservoirs is much larger than that of the lead–zinc deposits. In a longitudinal view, the bitumen, formed through the thermal cracking of the paleo-oil reservoirs, develops within the Dengying Formation and ancient weathering crust. Conversely, the lead–zinc deposits or mineralization sites are confined solely to the bacciform dolomite, strictly governed by the bacciform dolomite fracture zone. The Pb–Zn deposits in the Micangshan district exhibit a close association with the paleo-oil reservoirs in terms of their plane and vertical distribution characteristics. However, the occurrence ranges of the two are not entirely congruent. The locations where lead–zinc deposits occur merely constitute a minor proportion of the distribution of paleo-oil reservoirs.

5.2. Hydrocarbon Generation History and Timing of Mineralization

Song et al. [36] employed high-precision Rb–Sr isotope analysis on sphalerite-galena pairs from the Nanmushu deposit, selecting samples demonstrating robust analytical reproducibility (MSWD = 1.11). Their isochron regression yielded a Late Cambrian–Early Ordovician mineralization age of 486.7 ± 3.1 Ma, with an initial 87Sr/86Sr ratio of 0.710521 ± 0.00009. Wang et al. [4] conducted a study on the formation ages of the three lead–zinc deposits (Xinli, Zhujiaba, and Nanmushu) that are distributed in an east-to-west orientation on the surface within the Miciangshan. Their research revealed that the early lead–zinc deposits were formed at 468.3 ± 3.8 Ma. The Rb–Sr isotopic isochron age obtained is comparable to the average metallogenic age of the MVT lead–zinc mineralization belt within the Micangshan area. Specifically, the metallogenic time of the Nanmushu Pb–Zn deposit is 486.7 ± 3.1 Ma, whereas that of the Kongxigou Pb–Zn deposit is 472 ± 6.1 Ma. Notably, both the Nanmushu and Kongxigou Pb–Zn deposits are situated within the same lead–zinc mineralization zone, and their ore-forming fluid activity occurred during the same period. Interestingly, the Nanmushu Pb–Zn deposit located in the east is older than the Kongxigou deposit in the west. Therefore, based on the geographical location and metallogenic time of the lead–zinc deposits within the Micangshan district, it is proposed that the lead–zinc ore-forming fluid migrated from east to west.

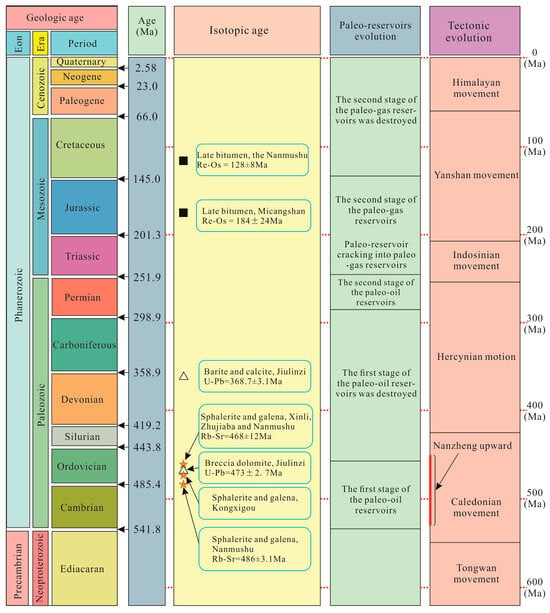

Previous studies have shown that the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs in the Micangshan district were established during the early to Middle Cambrian period and subsequently destroyed toward the end of the Middle Cambrian [4,18,20]. The second phase of paleo-oil reservoirs formation occurred in the early Permian, with these reservoirs gradually being damaged by tectonic movements following the Late Triassic [20]. Residual thermal cracking asphalt is a testament to this geological history [4,18,20,24,37]. By comparing the formation time of lead–zinc deposits in the Micangshan area with the evolution time of paleo-oil reservoirs, it can be inferred that the lead–zinc deposits are only likely to be associated with the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs (Figure 13). The coexistence of sphalerite, galena, and early bitumen provides the most direct evidence of the genetic link between lead–zinc ore and the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs. Conversely, the formation and destruction timeline of the second-stage paleo-oil reservoirs bear no relation to the mineralization of lead–zinc deposits.

Figure 13.

Coupling relationship between Pb–Zn deposit, paleo-reservoirs evolution, and tectonic evolution in the Micangshan area. The Re–Os data of the Micangshan late bitumen are sourced from Ge et al. [38]. The U–Pb data of the Jiulinzi barite and calcite are sourced from Xiong et al. [39]. The Rb–Sr data of the Xinli, Zhujiab and Nanmushu sphalerite and galena are sourced from Wang et al. [4]. The U–Pb data of the Jiulinzi breccia dolomite are sourced from Xiong et al. [27]. The Rb–Sr data of the Nanmushu sphalerite and galena are sourced from Song et al. [36].

5.3. Source and Migration of Ore-Forming Fluid

The hydrogen and oxygen isotopes of gangue minerals quartz, barite, and calcite in the Micangshan lead–zinc deposits indicate that the ore-forming fluid is a mixed source of ancient seawater and metamorphic water and has the characteristics of organic [34,40]. This interpretation is further supported by the presence of H2O, H2S, CH4, and bitumen within fluid inclusions of sphalerite and gangue minerals, indicating that hydrothermal ore fluids rich in organics, Pb, Zn, and reducing agents co-existed.

Diagnostic evidence for organic matter involvement in mineralization includes: (1) methane-rich fluid inclusions and (2) bitumen inclusions preserved in paragenetic mineral assemblages (dolomite-quartz-barite-sphalerite-galena). The Pb–Zn mineralization in the Micangshan area exhibits zonation characteristics. Ore mineral assemblages display an east–west progression. Sphalerite-dominated mineralization with minor galena in eastern deposits (Nanmushu, Kongxigou) transitions westward to sphalerite-galena associations (Zhujiaba, Fucheng), ultimately evolving into galena-dominated mineralization with negligible sphalerite in western deposits (Yangba, Xinli, Guimin). Notably, large-scale, high-grade deposits are restricted to the eastern sector (Nanmushu-Kongxigou), contrasting with limited mineralization in western occurrences.

This spatial distribution correlates with the Micangshan paleo-uplift structure, where the Guanyinya area represents the uplift core and the Guanyinya–Nanmushu axis defines the paleo-uplift slope. Paragenetic sequences reveal sphalerite precipitation consistently precedes galena deposition within individual mineralization stages under stable physicochemical conditions (pH, fO2, fS2). Radiometric ages exhibit a westward young trend, with Nanmushu deposits predating Kongxigou deposits (468.3 ± 3.8 Ma average age for Xinli, Zhujiaba, and Nanmushu deposits) [4]. These observations support an east-to-west hydrothermal migration model along the paleo-uplift slope. In the eastern slope zone (Nanmushu-Kongxigou), high-grade mineralization occurred because of the early-stage fluids, which were then followed by the subsequent westward migration of fluids towards the uplift core. During the migration of ore-forming fluids, they underwent a gradual cooling process, accompanied by a decrease in density. Additionally, the early mineralization events led to the depletion of lead–zinc resources. As a result, the western part of the Micangshan area is dominated by galena, with extremely limited sphalerite. Late-stage fluorite-rich mineralization (Xinli fluorite deposits) subsequently developed, completing the metallogenic sequence.

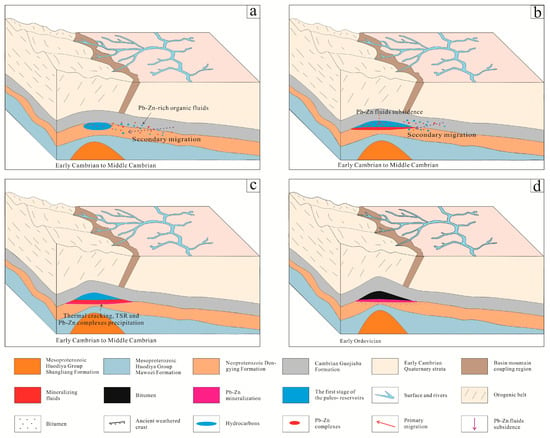

5.4. Mineralization Model

Song et al. [36] conducted an in-depth study on the provenance of ore-forming materials in the lead–zinc deposits located within the Mayuan–Baiyu district. Their findings suggested that the Guojiaba Formation could potentially serve as a metal source. Building on this research, Huang et al. [18] further investigated the source rocks in the same geographical region and concluded that the bitumen discovered in the Dengying Formation originated from the Guojiaba Formation, which is located above the lead–zinc mineralization. Consequently, the Guojiaba Formation emerges as a “dual source layer,” which not only furnishes essential metal source for deposits but also supplies the organic matter for paleo-oil reservoirs.

During the Early to Middle Cambrian, the Guojiaba Formation preserved Early Cambrian paleo-seawater within the formation. Progressive deep burial of the Guojiaba Formation led to gradual temperature elevation, triggering hydrocarbon generation from source rock organic matter upon reaching the thermal maturation threshold (80–120 °C; Figure 14a). The Fucheng-Kongxigou-Nanmushu area, situated on the southeastern margin of Micang Mountain and proximal to the hydrocarbon generation center, provided favorable conditions for lead–zinc metallogenic element mobilization through abundant hydrocarbon production.

Figure 14.

Mineralization model of the lead–zinc deposit in the Micangshan area. (a) The Early Cambrian to Middle Cambrian periods witnessed the secondary migration of lead-zinc-rich organic fluids. (b) Progressive accumulation of metal-bearing complexes at the reservoir base during the Early Cambrian to Middle Cambrian periods. (c) Late Cambrian–Early Ordovician Nanzheng Uplift activity induced crustal uplift, dolomite fracture zones, halted hydrocarbon generation, and yielded mineralizing hydrothermal fluids. (d) During the Early Ordovician, lead-zinc mineralization occurrences and bitumen accumulations were characterized by a regular spatial distribution.

The Nanzheng Uplift positioned the Micangshan Paleo-uplift center near Guanyinya, with the Fucheng-Kongxigou-Nanmushu area is a slope. Hydrocarbons discharged from the Guojiaba Formation underwent primary migration, migrating through pores, vugs, and fractures into the ancient, weathered crust. The occurrence of a substantial quantity of bitumen within the ancient, weathered crust offers compelling evidence. Previous studies have established that hydrocarbon-derived organic matter facilitates metal element activation, transport, enrichment, and precipitation through adsorption, coordination, complexation, cation exchange, and redox processes [41,42,43]. The migratory and enriching effects of metal elements triggered by organic matter components or petroleum, along with their regulation of the metallogenic environment [40]. The primary migration extracted a large amount of Pb–Zn elements from the Guojiaba Formation, generating organic-rich hydrothermal fluids containing Pb–Zn complexes (Figure 14a). Subsequent secondary migration facilitated enrichment of the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs within the Dengying Formation and weathering zone. The Guojiaba Formation hinders the upward migration of hydrocarbons and compels them to migrate downward into the underlying strata. During this secondary migration, Pb–Zn complexes were co-transported with hydrocarbons but exhibited density-driven segregation, resulting in progressive accumulation of metal-bearing complexes at the reservoir base (Figure 14b).

During the Late Cambrian to Early Ordovician, intensified Nanzheng Uplift activity induced pronounced crustal uplift. Interlayer slip and shearing within the Dengying Formation’s thick dolomite sequence generated brecciated dolomite fracture zones. Concurrently, elevated formation temperatures and pressures terminated hydrocarbon generation in the Guojiaba Formation source rocks. The thermal evolution of first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs, brines enriched in Pb and Zn, produced mineralizing hydrothermal fluids (Figure 14c). Tectonic movement drove the westward migration of these fluids along the paleo-uplift slope toward the Guanyinya area, proximal to the Nanmushu oil–water interface.

Thermal alteration of the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs, driven by compressional dynamics of the Nanzheng Uplift, with the temperature exceeding 127 °C [41], induced thermal cracking of crude oil (heavy oil → light oil + H2S + CO2 + S) and thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR; Hydrocarbon + CaSO4 (sulfate) → CaCO3 + CO2 + H2S + H2O + S [11,18,44,45]). This process generated H2S, CH4, CO2, and stage I bitumen, with TSR reaction fronts localized at the interface between Pb–Zn mineralizing fluids and the paleo-oil reservoirs (Figure 14c). At this redox boundary, sulfide precipitation occurred via the reaction: Pb–Zn complexes + H2S → PbS↓ + ZnS↓ [18]. Density-driven gravitational settling facilitated downward accumulation of sulfide precipitates within brecciated dolomite fracture zones, while overlying strata remained largely barren except for bitumen residues.

The westward migration of Pb–Zn mineralizing fluids along the paleo-uplift slope, driven by tectonic movement, was accompanied by thermal cracking attenuation that established a systematic mineral zonation. Sphalerite preferentially precipitated under elevated thermal regimes due to the temperature-dependent solubility contrast between Zn-chloride and Pb-bisulfide complexes in hydrothermal fluids [9], whereas galena saturation occurred at lower temperatures as Pb complexes destabilized [7]. This thermal gradient produced an east-to-west spatial distribution pattern in the southern mineralization belt: sphalerite-dominant → sphalerite-galena → galena-dominant assemblages (Figure 11), with economic-grade deposits restricted to the Nanmushu and Kongxigou.

During Pb–Zn complex precipitation under reducing conditions, ore fluids exhibit minimal bitumen concentrations, resulting in CH4-dominated volatiles with trace bitumen inclusions within sphalerite and gangue minerals. The Early Ordovician reactivation of the Nanzheng Uplift triggered crustal uplift and erosional denudation in the Micangshan area. This process degraded the preservation conditions of the first-stage reservoirs, ultimately leading to the differential distribution patterns of Stage I bitumen and Pb–Zn mineralization observed in the Dengying Formation (Figure 10 and Figure 14d).

6. Conclusions

Based on the results and the foregoing discussion, the following conclusions are reached:

- The Pb–Zn mineralization in the Micangshan region exhibits a significant correlation with paleo-oil reservoirs. The primary inclusions within sphalerite are composed of bitumen, CH4, and H2S, which offer evidence for the participation of oil and gas reservoirs in the lead–zinc mineralization process.

- Rb–Sr isotopic dating suggests that the MVT Pb–Zn mineralization in the Micangshan deposits occurred during the Late Cambrian to Early Ordovician, coinciding with the formation of the first-stage paleo-oil reservoirs.

- The ore-forming fluids are derived from a mixed source of ancient seawater, metamorphic water, and organic-rich fluids, with the latter originating from the thermal cracking of paleo-oil reservoirs.

- The ore-forming fluid is rich in organic matter and migrates westward along the slope of the ancient uplift of Micangshan, forming high-grade deposits at the eastern slope zone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H.; formal analysis, X.H. and Y.Z.; funding acquisition, C.C. and X.H.; investigation, X.H., Y.G., X.L. and X.C.; methodology, C.C.; project administration, C.C.; resources, X.H. and C.C.; software, X.H. and X.W.; supervision, X.H.; validation, Y.G., X.L. and X.C.; visualization, X.H. and X.W.; writing—original draft, X.H.; writing—review and editing, X.H. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41372093), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2023NSFSC0274) and Chengdu Technological University Talent Program (Grant No. 2024RC033).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Wei Sun and the reviewer for their constructive reviews and valuable suggestions that significantly improved the article’s presentation. We extend our thanks to the editor of the Minerals for their insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kesler, S.E.; Jones, H.D.; Furman, F.C.; Sassen, R.; Anderson, W.H.; Kyle, J.R. Role of crude oil in the genesis of Mississippi Valley-type deposits: Evidence from the Cincinnati arch. Geology 1994, 22, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Mao, J.; Ouyang, H.; Sun, J. The genetic relationship between hydrocarbon systems and Mississippi Valley-type Zn-Pb deposits along the SW margin of Sichuan Basin, China. Int. Geol. Rev. 2013, 55, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtig, N.C.; Hanley, J.J.; Gysi, A.P. The role of hydrocarbons in ore formation at the Pillara Mississippi Valley-type Zn-Pb deposit, Canning Basin, Western Australia. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 102, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, F.F.; Li, N.; Fu, Y.Z. The relationship between hydrocarbon accumulation and Mississippi Valley-type Pb-Zn mineralization of the Mayuan metallogenic belt, the northern Yangtze block, SW China: Evidence from ore geology and Rb-Sr isotopic Dating. Resour. Geol. 2020, 70, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, X.F.; Tang, G.; Liu, Y.D.; Zou, G.F. S-Pb isotopes and tectono-geochemistry of the Lunong ore block, Yangla large Cu deposit, SW China: Implications for mineral exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 136, 104249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hu, Y.Z.; Zhou, J.X.; Guan, S.J.; Xu, S.H.; Cui, M.; Zhang, J.L.; Tan, X.L.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Genetic link between Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) Pb-Zn mineralization and hydrocarbon accumulation in the Niujiaotang ore field, SW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 165, 105929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.L.; Sangster, D.F.; Kelley, K.D.; Large, R.; Garven, G.; Allen, C.R.; Gutzmer, J.; Walters, S. Sediment-Hosted Lead-Zinc Deposits: A Global Perspective; Society of Economic Geology, Inc.: Littleton, CO, USA, 2005; 100th Anniversary Volume, pp. 561–607. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, D.L.; Bradley, D.C.; Huston, D.; Pisarevsky, S.A.; Taylor, R.D.; Gardoll, S.J. Sediment-hosted lead-zinc deposits in earth history. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 593–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Q. The Genetic Model of Mississippi Valley-Type Deposits in the Boundary Area of Sichuan, Yunan and Guizhou Provinces, China. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China, 2008; pp. 1–177, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gize, A.P.; Barnes, H.L. The organic geochemistry of two Mississippi Valley-type lead-zinc deposits. Econ. Geol. 1987, 82, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.X.; Zhang, Y.M.; Li, B.H.; Xue, C.J.; Dong, S.Y.; Fu, S.H.; Cheng, W.B.; Liu, L.; Wu, C.Y. The coupling relationship between metallization and hydrocarbon accumulation in sedimentary basins. Earth Sci. Front. 2010, 17, 083–105, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.Z.; Liu, S.G.; Chen, C.C.; Wang, D.; Sun, W. The genetic relationship between MVT Pb-Zn deposits and paleo-oil/gasres-ervoirs at Heba South eastern Sichuan Basin. Earth Sci. Front. 2013, 20, 107–116, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.X.; Li, B.H.; Xu, S.H.; Fu, S.H.; Dong, S.Y. Characteristics of hydrocarbon-bearing ore-forming fluids in the Youjiang Basin, South China: Implications for hydrocarbon accumulation and oremineralization. Earth Sci. Front. 2007, 14, 133–146, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Powell, T.G.; Macqueen, R.W. Precipitation of sulfide ores and organic matter: Sulfate reactions at pine point, Canada. Science 1984, 224, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, N.S.F.; Zentilli, M. Association of pyrobitumen with copper mineralization from the uchumi and talcuna districts, central chile. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2006, 65, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Wang, J.Z.; Ni, S.J.; Li, C.Y.; Hu, X.Q.; Li, T.Y. Na-Cl-Br systematics of mineralizing fluid in Mississppi Valley-type deposits from southwest China. Mineral. Petrol. 2002, 22, 38–41, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.C. Hydrothermal Exhalative Metallogeny of Stratiform Pb-Zn Deposits on Western Margin of the Yangtze Craton. Ph.D. Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2005; pp. 1–177, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.D.; Chen, C.H.; Song, Z.J.; Yin, L.; Gu, Y.; Lai, X.; Chen, X.J. Relationship between bitumen and zinc-lead mineralization in the nanmushu zinc-lead deposit, northern margin of sichuan basin, China. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, G.Z.; Li, N.; Fu, Y.Z.; Lei, Q.; Mao, X.L. Genetic link between Mississippi Valley-Type (MVT) Zn-Pb mineralization and hydrocarbon accumulation in the Nanmushu, northern margin of Sichuan Basin, SW China. Geochemistry 2021, 81, 125805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Study on the Multi-Phase Fluid Activities of Dengying Formation and Tectonic Uplift of Micang Mountain Area. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2013; pp. 1–80, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. The Formation and Evolution of Hydrothermal Fluids in the MVT Lead-Zinc Deposits in Northern Margin of Sichuan Basin. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2015; pp. 1–101, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.S.; Liu, S.G.; Sun, W.; Han, K.Y.; Luo, Z.L.; Xie, Z.L.; Huang, Y.Z. Study on characteristics of Sinian-Silurian bitumen outcrops in the Longmenshan-Micangshan area Southwest China. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2009, 36, 687–696, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.C.; Wang, J.C.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhang, Q.S.; Kong, W.N.; Chen, J.L.; Li, C.J. Metallogenic geological background of lead-zinc polymetallic deposits of Sinian Dengying Formation in the northwestern margin of Yangtze landmass. Geol. Bull. China 2012, 31, 773–782, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Long, T. Studies on the Coupling Relationship of the MVT Lead-Zinc Deposits and the Ancient Oil (Gas) Reservoir in the Northern Margin of the Sichuan Basin. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2016; pp. 1–79, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S. Origin of Breccia and Its Metallogenesis of Mayuan Lead-Zinc Deposit. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2015; pp. 1–74, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hou, M.T.; Wang, D.G.; Deng, S.B.; Yang, Z.R. Geology and genesis of the Mayuan lead-zinc mineralization belt in Shaanxi Province. Northwest. Geol. 2007, 40, 42–60, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, S.F.; Jiang, S.Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhao, K.D.; Jiang, M.R. Ore genesis of Kongxigou and Nanmushu Zn-Pb deposits hosted in Neoproterozoic carbonates, Yangtze Block, SW China: Constraints from sulfide chemistry, fluid inclusions, and in situ S-Pb isotope analyses. Precambrian Res. 2019, 333, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Yang, Y.L.; Song, Z.; Chen, X.J.; Jia, W.; Lai, X.; Li, H.Z.; Yin, L.; Huang, X.D.; et al. Geology, fluid inclusion, bitumen and isotope geochemistry of the organic-matter-rich Nanmushu lead-zinc deposit, Mayuan, the northern margin of the Yangtze platform. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.X.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, S.W.; Lei, W.S.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.T.; Li, X. Origin of the breccia and metallogenic geological background of Mayuan Pb-Zn deposit. Earth Sci. Front. 2016, 23, 94–101, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, R.K. ISOPLOT: A Plotting and Regression Program for Radiogenic-Isotope Data (Version 2.9); U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1996; Volume 91, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X.; Gu, L.X.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Wu, C.Z.; Zhang, J.K.; Li, H.M.; Yang, J.D. Geochronology and Nd-Sr-Pb isotops of the bimodal volcanic rocks of the Bogda rift. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2006, 22, 1215–1224, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, S.; Halliday, A.N.; Kesler, S.E.; Henry, D.; Jones, J.; Richard, K.; Thomas, E.L. Rb-Sr dating of sphalerites from Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) ore Deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1993, 57, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettke, T.; Diamond, L.W. Rb-Sr isotopic analysis of fluid inclusions in quartz: Evaluation of bulk extraction procedures and geochronometer systematics using synthetic fluid inclusions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1995, 59, 4009–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Haack, U.; Stedingk, K. Rb-Sr dating of epithermal vein mineralization stages in the eastern harz mountains (germany) by paleomixing lines. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 1803–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.; Schneider, J.; Chiaradia, M. Timing and metal sources for carbonate-hosted Zn-Pb mineralization in the Franklinian Basin (North Greenland): Constraints from Rb-Sr and Pb isotopes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 79, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.J.; Chen, C.H.; Yang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, L.; Li, H.Z. Mineralization age and sources of ore-forming material of the nanmushu Zn-Pb deposit in the micangshan tectonic belt at the northern margin of the yangtze craton, china: Constraints from Rb-Sr dating and Sr-Pb isotopes. Resour. Geol. 2020, 70, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Z.; Liu, S.G.; Li, N.; Wang, D.; Gao, Y. Formation and preservation mechanism of high quality reservoir in deep burial dolomite in the Dengying Formation on the northern margin of the Sichuan basin. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 667–678, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ge, X.; Shen, C.B.; Selby, D.; Wang, G.Z.; Yang, Z.; Gong, Y.J.; Xiong, S.F. Neoproterozoic-Cambrian petroleum system evolution of the Micang Shan uplift, northern Sichuan Basin, China: Insights from pyrobitumen rhenium-osmium geochronology and apatite fission-track analysis. GSA Bull. 2018, 102, 1429–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.F.; Jiang, S.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhao, J.X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; Duan, Z.P.; Niu, P.P.; Xu, Y.M. A Mississippi Valley-type Zn-Pb mineralizing system in South China constrained by in situ U-Pb dating of carbonates and barite and in situ S-Sr-Pb isotopes. GSA Bull. 2022, 134, 2880–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.B.; Li, K.; Qian, B.; Li, W.Y.; Zheng, C.M.; Zhang, C.G. Trace elements, S, Pb, He, Ar and C isotopes of sphalerite in the Mayuan Pb-Zn deposit, at the northern margin of the Yangtze plate, China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 32, 251–263, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, J. Metal enrichments in solid bitumens: A Review. Miner. Depos. 1988, 23, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, D.A.C.; Gize, A.P. The Role of Organic Matter in Ore Transport Processes. In Organic Geochemistry; Engel, M.H., Macko, S.A., Eds.; Topics in Geobiology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1993; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machel, H.G. Bacterial and thermochemical sulfate reduction in diagenetic settings-old and new insights. Sediment. Geol. 2001, 140, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.A. H2S-related porosity and sulfuric acid oil-field karst. In Unconformities and Porosity in Carbonate Strata; Budd, D.A., Saller, A.H., Harris, P.M., Eds.; AAPG Memoir: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1995; Volume 61, pp. 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, C.T.; Li, S.Y.; Ding, K.L.; Zhong, N.N. Study of simulation experiments on the TSR system and its effect on the natural gas destruction. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2005, 48, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.