Abstract

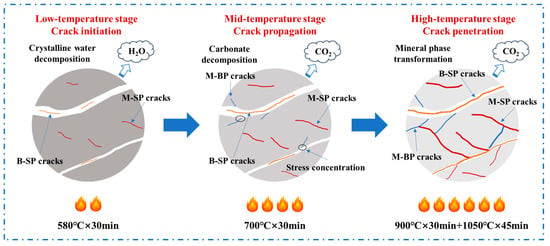

Thermal bursting and pulverization during calcination adversely affect the production of quicklime from low-grade limestones. This study investigates the mechanisms of these phenomena across different temperature stages by integrating thermogravimetric, microstructural, and phase composition analyses. During low-temperature calcination, bound water decomposition induces self-propagating cracks in both the matrix and boundary regions. During mid-temperature calcination, carbonate decarbonation causes pore formation and shrinkage, promoting crack propagation from the boundary into the matrix. When calcined at high-temperature, complete phase transformation and the anisotropic structure of boundary dolomite collectively led to through-crack development. The differing thermal properties and microstructures of calcite and dolomite are thus identified as the primary factors governing crack evolution and thermal bursting behavior.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, the metallurgical industry is confronted with a critical dilemma, namely, the relentless depletion of high-grade limestone reserves against rising demand. This scarcity has spurred urgent interest in utilizing low-grade limestones, characterized by suboptimal chemical composition (typically with CaO content below 51 wt.%) and high levels of impurities (e.g., MgO, SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3) [1,2]. While traditionally deemed unsuitable for many applications, these abundant resources offer a viable alternative for producing quicklimes in sintering and steelmaking processes, thereby alleviating raw material shortages and reducing environmental impacts from quarrying [3,4,5]. However, a critical technological barrier impedes their efficient use, namely, severe thermal bursting and pulverization during calcination.

The phenomenon of thermal bursting is initiated by the formation of microcracks form due to many physical and chemical stresses, including moisture evaporation, anisotropic thermal expansion, and the decomposition of carbonates [6,7,8]. The thermal decomposition of carbonates, particularly calcium carbonate, is a complex endothermic process whose kinetics and mechanism are influenced by factors such as CO2 pressure, sample self-cooling, and particle characteristics [9]. As the temperature rises, the mechanical strength of the limestones diminishes, enabling microcracks to proliferate and coalesce. Furthermore, chemical reactions involving impurities can exacerbate crack formation, resulting in severe fragmentation and pulverization of the lime products [10,11]. In industrial practice, particularly in dynamic environments such as rotary kilns, thermal bursting can result in lime product particle sizes failing to meet specification requirements, leading to diminished product quality and consequently reduced output [12]. The lime powders generated by thermal bursting also disrupt kiln temperature control and cause operational issues such as ash leakage, severely hampering continuous pro-duction [13]. It is imperative to acquire a comprehensive understanding of the thermal fracturing behavior and mechanisms of low-grade limestone to successfully address the challenges it poses in industrial applications.

Current strategies to minimize thermal bursting have primarily focused on optimizing process parameters like heating rate, peak temperature, and holding time [14,15,16]. Nevertheless, these efforts have yielded only limited success, as they often ad-dress the symptoms rather than the root causes. These efforts have yielded only modest success, primarily due to the absence of theoretical guidance concerning the underlying mechanisms. Fundamental studies have identified several influencing factors. For in-stance, Dollimore et al. [17] assessed the decrepitation tendencies of limestones and dolomites using the Pilkington test and thermogravimetric analysis, identifying a weaker correlation between particle size change and decrepitation in limestone than in dolomite. Sivrikaya [18] systematically linked chemical composition and crystal size to decomposition and thermal stability, noting that crystal size as a critical factor affecting carbonate decomposition, with larger crystals exhibiting greater thermal bursting tendency. He et al. [19] further reported the influence of phase structure, observing that aragonite, a polymorph of calcite, transforms to calcite at 300~400 °C with up to 11% volumetric expansion, inducing low-temperature thermal bursting.

While these studies have clearly cataloged factors affecting thermal bursting, re-search in understanding the synergistic and dynamic interplay between thermal, chemical, and mechanical stresses that govern crack initiation and propagation across different temperature stages still remains scarce. The intrinsic limitation of previous research lies in its failure to systematically unravel the coupled thermo-mechano-chemical mechanisms within low-grade limestones under complex calcination conditions. This inherent limitation hinders the predictive capability and control of thermal bursting.

In this study, we conduct a stage-wise investigation into the thermal bursting behavior of low-grade limestones. We employ a multi-faceted analytical approach, combining thermogravimetric-differential thermal analysis (TG-DTA), microstructure characterization (SEM-EDS), phase composition analysis (XRD), and mechanical property testing (microhardness). This strategy is designed to decouple the contributions of different mechanisms at low, medium, and high temperatures, thereby providing new insights into crack initiation and evolution. This paper innovatively links the microscopic compositional differences between calcite and dolomite directly to the crack formation and propagation processes evolving with temperature, thereby revealing the mechanism by which intrinsic microstructural variations influence thermal fracturing behavior. The proposed method is not limited to limestones but can be extended to other low-grade carbonates, such as dolomite, calcite, griotte, and ananthite.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The limestone samples researched here belong to the Ordovician Majiagou Limestones, sampled in northeast China. The quantitative analysis, total acid insoluble (TAI), and loss on ignition (LOI) results are showed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical analysis, TAI and LOI results of limestone samples.

The samples contain 48.728 wt.% CaO and 3.742 wt.% MgO, belonging to the carbonate content standard of fourth-grade magnesium limestones (52.5 wt.%) stipulated by YB/T 5279-2005. Except for the main carbonate minerals, the total content of impurities, presenting as SiO2, Fe2O3, Al2O3 and TiO2, was found to be higher than that of conventional limestones. The higher-than-normal levels of TAI value further confirmed this conclusion. Thus, it can be seen that the minerals comprise principal calcite phase with content percentage of about 75.26%, secondary crystalline phase of dolomite, accounting for about 19.65%, as well as some impurities, belonging to typical low-grade limestones.

2.2. Methods

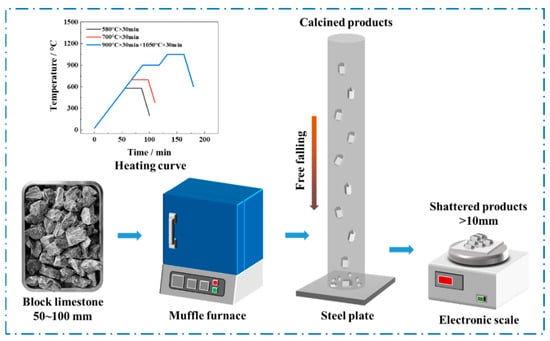

In a typical procedure (Figure 1), the low-grade limestone samples with a size of 50 to 100 mm were subjected to calcination in a muffle furnace at room temperature to specific temperature with the heating rate of 10 °C/min and kept for 30 min before furnace cooling.

Figure 1.

Testing procedure for thermal bursting behaviors of low-grade limestones and heating curves at different calcination stages.

The ignition loss rate (ILR) was calculated from the equation below:

where mbc is the mass of the limestone samples before calcination (g), and mac is the mass of the samples after calcination (g).

The macroscopic morphology of low-grade limestones was observed using a three-dimensional optical stereomicroscope (4K3630-3D-B, Bokeshijue, Guangdong, China). The numbers and lengths of cracks were quantified from surface morphology photographs using the image analysis software integrated with the optical microscope. To ensure statistics representativeness, ten specimens were randomly selected from each group. Cracks on these specimens were systematically categorized based on their location and photographed. The length of each crack was then measured from the photographs using the measurement tools of the software. Origin Pro 2018C software was used to conduct a statistical analysis of the number, fraction and length of the given crack types obtained at different calcination temperatures.

In the shatter strength measurement, three to four calcined samples were taken as a group after being weighed, and were made to fall onto a steel plate (10 mm thick) from a height of 2 m. The blocks with a size greater than 10 mm were collected and weighed for the calculation of shatter rate. The final shatter rate was characterized by the average value of cumulative shatter rates for experiments.

The accumulation shatter rate (ASR) was obtained by the equation below:

Here, mbs represents the mass of calcined samples before shattering (g), and mas represents the mass of samples with a size greater than 10 mm after shattering (g).

The chemical composition of low-grade limestones was recorded by a ZSX Primus IV X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy instrument (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

The measurement of the total acid insoluble (TAI) value was performed as follows: the limestone powders with 200 mesh were dispersed in a 6 N HCl solution under thorough stirring until the quality remained constant. Subsequently, the collected samples were washed thrice with deionized water, and thoroughly dried in a drying oven at 378.15 K. The TAI value was calculated as follows:

Here, mi represents the mass of insoluble substance with drying treatment (g), and mt represents the total mass of added limestones (g).

The SX2-5-12N muffle furnace (Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was employed for the purpose of determining the LOI value of limestone powders with 200 mesh at 1273.15 K for 2 h. The LOI value can be calculated as follows:

where mc is the total mass of limestones for calcination (g), and mr is the residual mass of limestones after calcination (g).

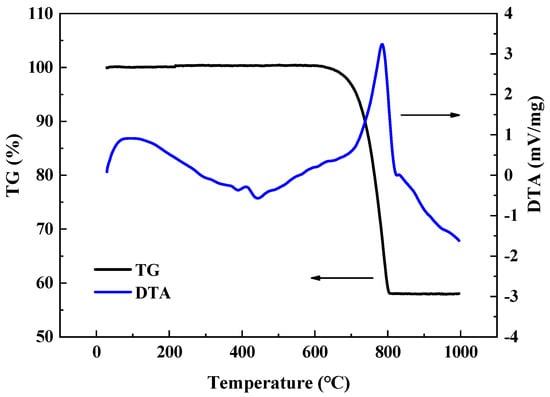

The TG/DTA curve was acquired with a STA 449 F5 simultaneous thermal analyzer (Netzsch GmbH, Selb, Germany) at temperatures ranging from 30 to 1000 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min in air.

The moisture content of limestone powders was assessed through a DGG-9100GD Electric Blast Constant Temperature Drying Oven (Shanghai Senxin Laboratory Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at a temperature of 378.15 K overnight. Before testing, the agate mortars were utilized for the grinding of the limestone samples into fine powders, and stainless steel laboratory sieves with the pore size of 200 mesh were employed for screening.

Bulk density and apparent porosity were measured with a Mettler ME104E analytical balance (Mettler Toledo, Zurich, Switzerland) via the Archimedes method. Specimens were initially dried at 110 °C to constant mass and cooled in a desiccator. The dry mass (m1) was recorded. Subsequently, specimens underwent vacuum impregnation by being evacuated to below −0.095 MPa for 5 min, slowly immersed in deionized water, and held under vacuum for another 5 min. After returning to atmospheric pressure, they were soaked for 30 min to achieve full saturation. The saturated mass was then weighed both in water (m2) and in air after surface drying (m3). These mass values were used to calculate the final bulk density ρb (g/cm3) and apparent porosity πa (%).

where m1 is the mass of samples with drying treatment (g), m2 is the apparent mass of saturated samples (g), m3 is the mass of saturated samples in air (g), and ρing is the density of the liquid at the test temperature. To ensure the reliability of experimental result, the data of bulk density and apparent porosity were finally reported based on the arithmetic mean values of five sets of bulk samples.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of samples were obtained by a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray Diffractometer (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, America), and the data were collected in Bragg-Brentano mode using Cu Kα radiation with the scan rate of 5°/s at 40 kV and 40 mA. To analyze the X-ray diffraction spectra of different regions, zoned sampling should be conducted on the basis of the appearance of the matrix zone and boundary zone. The targeted regions were separated using a hand-held electric angle grinder with a diamond-tipped blade. The separated pieces were then individually ground into a fine powder using an agate mortar, passed through a 200-mesh sieve to ensure uniformity, and dried at 105 °C until a constant weight was attained for further characterization.

Microscopic morphology was conducted using a Zeiss-ΣIGMA HD Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, Oberkochen, Germany) operated at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. Energy Dispersion Spectrum (EDS) analysis was acquired with the Oxford X-max Spectrum Analyzer (Oxford, England), an accessory equipped in scanning electron microscope. The samples were loaded on a rounded Cu specimen stage for support.

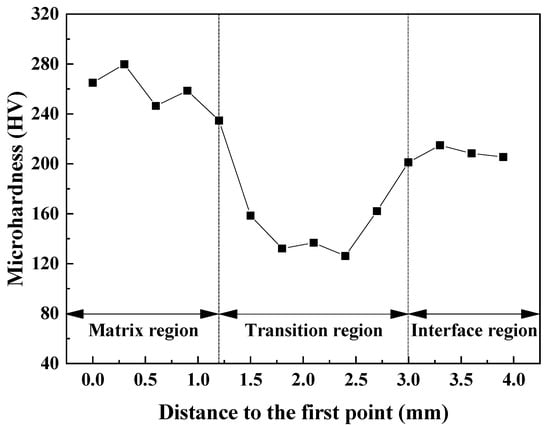

The microhardness of the transition zone between the matrix and interface was measured using the HVS-1000 Digital Display Vickers Microhardness Tester (Shanghai Materials Testing Machine Factory, Shanghai, China). The load of 1 kgf was applied via a diamond indenter for a duration of 10 s. Set a test point at intervals of 0.5 mm, with five tests conducted at each position and the average value taken.

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Bursting Behaviors of Low-Grade Limestones

The phenomenon of thermal bursting in low-grade limestones is understood to occur as a result of the concentration of internal stresses within the rock structure, which is triggered by temperature gradients [20]. Upon the attainment of a certain temperature, the microcracks that are present within the limestones undergo rapid expansion, which subsequently results in structural damage [21]. In the present study, batch calcination tests were conducted at three distinct temperature stages, namely, low-temperature calcination stage (580 °C), mid-temperature calcination stage (700 °C) and high-temperature calcination stage (1050 °C) to investigate crack formation and expansion in low-grade limestones at different temperature stages.

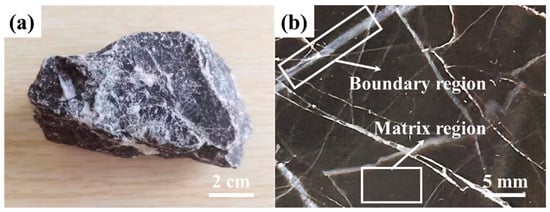

The surface appearance and cross-section morphology of typical low-grade limestones is presented in Figure 2. The limestone blocks exhibit distinctive black coloring with the milky interstratified inclusions. Based on the analyses of the minerogenetic conditions and chemical composition, this specimen can be classified as a typical endogenetic sedimentary rock [22]. Furthermore, a large-area dark homogeneous region is observed, interspersed with some bright crisscrossed regions. For analytical purposes, these regions are defined as matrix region and boundary region, respectively.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic appearance of the representative low-grade limestone specimen: (a) surface view of the raw block sample, showcasing its distinctive black matrix with milky-white interstratified inclusions, characteristic of an endogenetic sedimentary rock; (b) cross-section morphology, revealing the defined matrix and boundary regions, with a representative boundary zone highlighted by the white box and arrow.

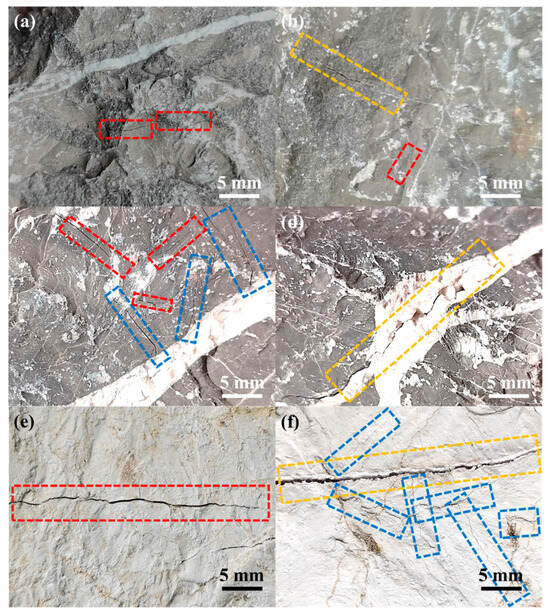

The evolutionary morphology of thermal cracks on the limestone surfaces across different calcination stages is delineated in Figure 3. This morphology was consistently observed in ten independent replicates for each condition, confirming the generalizability of the behavior.

Figure 3.

Representative optical images of the progressive evolution of thermal cracks on limestone surfaces during calcination: (a,b) low-temperature stage, characterized by M-SPCs (marked with red boxes) and B-SPCs (marked with orange box), manifested as crack initiation; (c,d) mid-temperature stage, characterized by M-SPCs, B-SPCs and M-BPCs (marked with blue box), manifested as crack propagation and the emergence of M-BPCs; (e,f) high-temperature stage, displayed all three crack types, manifested as crack penetration and network formation.

During the low-temperature calcination stage (Figure 3a,b), the specimens retained their original macroscopic integrities. The primary morphological change was the initiation of fine micro-cracks, defined as Self-Propagating Cracks in the Matrix (M-SPCs, red boxes) and Boundary (B-SPCs, orange box). This study has indicated that microcrack propagation occurs due to the release of bound water and differing thermal expansion between the calcite matrix and the dolomite boundary, leading to altered crystal orientation and spatial arrangement [23].

At mid-temperature calcination condition (Figure 3c,d), the B-SPCs within wider boundaries underwent significant elongation and widening. Concurrently, a distinct new crack type emerged, namely, Boundary Propagation Cracks towards the Matrix (M-BPCs, blue boxes). The initiation of M-BPCs signifies a critical transition where stress concentrations at the matrix-boundary interface become the dominant driver of crack evolution, surpassing the isolated growth observed initially. This stage is thus characterized by the synergistic propagation of existing M-SPCs and B-SPCs, coupled with the initiation of interface-driven M-BPCs.

Following high-temperature calcination (Figure 3e,f), the dominant morphological feature was the penetration and interconnection of cracks, particularly the M-BPCs, which formed an interconnected state flanking the wide boundaries. The significant increase in crack length, without a substantial increase in the number of new cracks, indicates a shift in the failure mechanism from the initiation of new defects to the extensive propagation and coalescence of pre-existing ones. This pervasive crack network effectively compromises the mechanical integrity of the limestones. The absence of complete fragmentation in our static furnace tests is attributed to the lack of external mechanical agitation. In an industrial rotary kiln, this severely weakened microstructure would readily lead to the thermal bursting and pulverization observed in practice [24].

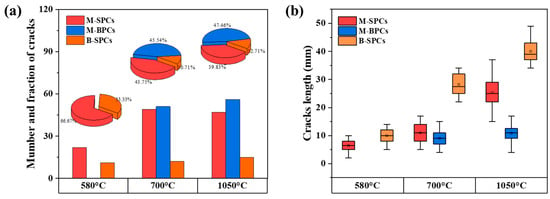

The number, fraction and length of various types of cracks in low-grade limestones after undergoing the calcination at different temperatures were counted to further reveal the principles of crack formation and expansion with temperature. As illustrated in Figure 4a, only M-SPCs and B-SPCs were observed in the low-temperature calcination process, with a ratio of approximately 2:1. During the subsequent mid-temperature calcination stage, the increase in the number of B-SPCs was not significant, whereas that of M-SPCs increased markedly, exceedingly twice the number of this crack type in the previous stage. This suggests that the formation of B-SPCs occurred predominantly during the low-temperature stage. By contrast, M-SPCs have been observed to form in both the low-temperature and mid-temperature stages. Significantly, M-BPCs only began to emerge in substantial numbers at the mid-temperature stage, indicating that a certain temperature threshold must be reached for their formation. After being calcined at a high temperature, the number ratio of the three types of cracks remained essentially unaltered.

Figure 4.

Statistics of temperature-dependent crack evolution behavior in low-grade limestones: (a) population distribution (number and fraction) of different crack types, indicating the dominant mechanisms at each stage; (b) Statistical distribution of crack lengths for each type.

The lengths of various types of cracks in low-grade limestones at different calcination stages are shown in Figure 4b. The box plots were generated to represent the distribution of crack lengths for each sample group. The central line in each box represents the median value of all measured crack lengths within that group.

The prevailing trend for the length of various crack types indicates an increase with rising temperature. Yang et al. [25] discovered in their research that the duration of the stress concentration stage of limestones show an increasing trend with temperature, which may explain the aforementioned phenomenon. Cwik et al. [9] characterized the thermal bursting behavior of low-grade limestones from Jutjärn quarry, located in Dalarna, Sweden, at different calcination temperatures. This was achieved using the degree of calcination and the average crack area percentage (Table 2). The results indicate that the number of cracks increases with rising temperature, consistent with our conclusions.

Table 2.

Analysis results of fractures for limestones from Jutjärn quarry [9].

Among these, the crack lengths of M-SPCs and B-SPCs exhibited a marked increase with the elevation of the calcination temperature, particularly at high temperature. This phenomenon may be associated with alterations in the internal structure of limestones at elevated temperature, including crystalline phase transformation, volume expansion, and the release of internal stress [26].

Conversely, the crack lengths of M-BPCs displayed comparatively negligible temperature dependence, which may be associated with their formation mechanism or the crack stress concentration patterns observed at varying temperatures. Consequently, it can be inferred that temperature is the primary factor in the propagation of cracks. At the microstructural level, elevated temperature induces changes in the crystalline lattice structure of limestones, particularly generating localized high-stress fields at heterogeneous interfaces [6,11]. The conditions established thus provide the energy necessary for crack initiation and propagation.

The shatter strength tests were conducted, which may, to a certain degree, reflect the propensity of low-grade limestones to undergo a sudden bursting during thermal events. The accumulation shatter rate (ASR) was utilized to characterize the shatter strength of the samples.

The ASR values of the low-grade limestones calcined at low-temperature and mid-temperature were found to be 0.04% and 1.7%, respectively, indicating less fragmentation of the limestones at the corresponding stages. It can thus be concluded that the calcination of low-grade limestones at temperature below 700 °C does not result in significant cracking behaviors. However, the ASR value after calcination at high-temperature exhibited a notable increase, reaching 35.63%. This suggests that the fracture resistance of calcined limestones diminishes markedly, primarily attributable to stress concentration and accelerated crack propagation resulting from crystalline phase transformations [27].

3.2. Thermal Bursting Mechanisms of Low-Grade Limestones

3.2.1. Low-Temperature Calcination Stage

The thermal decomposition process of low-grade limestones from room temperature to 1000 °C was investigated using simultaneous thermal analysis technology (Figure 5). The small heat-absorbing peak occurs at approximately 400 °C in the DTA branch, corresponding to the volatilization of moisture [28,29]. The prominent heat-absorbing peak observed at 800 °C is attributed to the weight loss of carbon dioxide accompanying the decomposition of calcium carbonate [30,31]. As indicated by the TG branch, the mass loss of the samples commenced at approximately 610 °C and concluded at around 800 °C, which correspond to the onset and conclusion of decarbonation, respectively. Notably, the weight reduction exhibited by the samples approximates 43%, which closely corresponds to the LOI value of 42.08% derived from the calcination experiment (Table 1).

Figure 5.

TG-DTA curves of the thermal decomposition process of low-grade limestones. The analysis provides a quantitative assessment of the decarbonation extent, with the total mass loss being consistent with the Loss on ignition (LOI) value, confirming the intense gas release during calcination.

As noted, the calcite phase in low-grade limestones has not yet decomposed at temperature below 580 °C. Thus, the formation of M-SPCs and B-SPCs can be attributed to the thermal stresses generated by the decomposition of bound water. In order to ascertain the impact of bound water on the formation and propagation of cracks, it was necessary to measure the moisture content and porosity of the samples. The moisture content of the powders with particle sizes of 200 mesh from the matrix and boundary region, which were subjected to drying at 778.15 K for an overnight period, reached 1.24% and 2.98%, respectively. The values obtained for these samples are considerably higher than those previously reported for conventional limestones, thereby substantiating the pronounced tendency towards hydration exhibited by the Ordovician Majiagou limestones, a property that is intrinsic to these rocks [18,32,33]. Furthermore, the bulk densities of the samples extracted from the matrix and boundary region were determined to be 2.70 g/cm3 and 2.84 g/cm3, respectively. The porosities of both samples were determined to be 0.08% and 0.91%, indicating that they exhibited dense (less than 0.8%) and slightly loose (0.8% to 2%) structures, respectively.

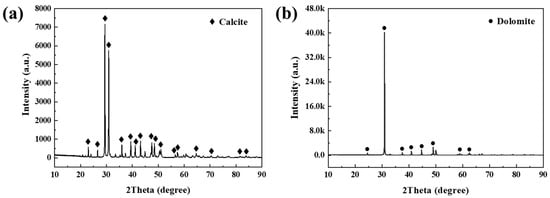

The phase structures present in different regions were elucidated through the analysis of X-ray diffraction patterns. The results indicate that the predominant mineral phase present in the matrix region is calcite (CaCO3), exhibiting high diffraction peak intensity and good crystallinity (Figure 6a). The mineral assemblage in the boundary region corresponds to dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) (Figure 6b). The mineral identification was verified by comparison with JCPDS standard cards (calcite: PDF#86-2334; dolomite: PDF#89-1304).

Figure 6.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns identifying the distinct mineral phases in different regions of the low-grade limestones: (a) matrix region, identified as calcite (CaCO3, PDF#86-2334); (b) boundary region, identified as dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2, PDF#89-1304).

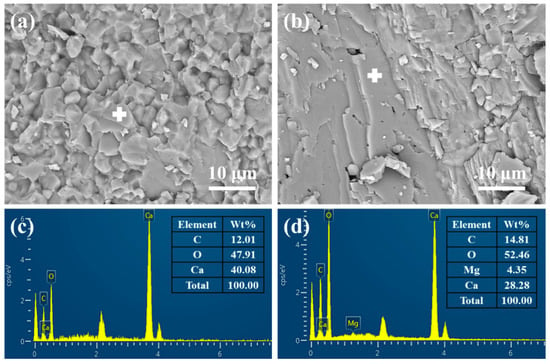

The microstructure and chemical composition of the disparate regions were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). As demonstrated in Figure 7a, the black matrix region exhibited compact grain structures with particle sizes ranging from 1.6 μm to 2.5 μm. The grains were distributed into allotriomorphic granular structures. In comparison, the formation of the white boundary regions is attributable to the interface directional deposition of laminar loosened microstructures with a thickness of less than 1 μm (see Figure 7b). The microstructural compactness exhibited in both regions corresponds with the results of porosity analysis. Moreover, the EDS analysis indicates that the chemical component of the matrix region was CaCO3, corresponding to the calcite phase (Figure 7c), while the CaMg(CO3)2 (dolomite phase) presented in the boundary region (Figure 7d), which are consistent with the results of the XRD analysis (Figure 6).

Figure 7.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) morphology and corresponding energy dispersion spectrum (EDS) patterns of low-grade limestone samples selected from different regions: (a,c) matrix region; (b,d) boundary region. The “+” symbols in Figure (a,b) denote the positions analyzed during the EDS point scan.

Vickers microhardness distributions were performed in order to reveal the hardness of different regions of low-grade limestones. According to Figure 8, the matrix region was found to have the high microhardness (227.0~277.5 HV), followed by the boundary zone, while the matrix-boundary transition region had the low microhardness (126.0~162.8 HV). It can thus be concluded that the Vickers microhardness characteristics of limestones are significantly influenced by the microstructure, which is consistent with the conclusion by Ghorbani’ group [34]. Liu et al. observed that when the temperature ranges from 250 °C to 400 °C, uneven expansion occurs among different mineral particles, leading to the formation of microcracks [35]. Meanwhile, the process of combined water decomposition is identified as a pivotal factor in the low-temperature cracking. Theoretically, upon attaining the temperature for the desorption and vaporization of bound water, moisture will diffuse preferentially along the pores within the limestones, thus forming vapor pathways [7]. Nevertheless, the restricted internal channels impeded the diffusion of gas out of the limestones, due to the low porosity. Once the internal gas pressure exceeds the local tensile strength of the material, micro-fractures are initiated [36]. These fractures are concentrated preferentially at grain boundaries, pores, and impurity particles, which represent the primary locations for the formation of M-SPCs and B-SPCs. Notably, the majority of cracks are relatively short and localized due to the limited concentration and release of thermal stresses brought about by the decomposition of the bound water.

Figure 8.

Vickers microhardness of cross-sections of low-grade limestones.

3.2.2. Mid-Temperature Calcination Stage

Following a mid-temperature calcination, the low-grade limestones commence the decomposition of carbonate preliminary decomposition according to the TG/DTA data (Figure 6). The principal chemical reaction that occurs is the decomposition of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) into calcium oxide (CaO) and carbon dioxide (CO2) gases, which results in the formation of pores within the microstructure of samples. Concurrently, the rhombohedral crystal structure of calcite (CaCO3) undergoes a transformation into a cubic structure, which is the characteristic form of lime (CaO) [14]. The decarbonation reaction results in a net reduction in apparent volume due to the lower molar volume of the solid CaO product compared to the original CaCO3 [37]. Simultaneously, the release of voluminous CO2 gas generates substantial micro-porosity within the solid matrix. Due to the increase in internal porosity and the decrease in volume, thermal stresses within the limestones are further accumulated and released [38]. The relatively dense structure of the matrix region impedes the escape of gas, resulting in the formation and propagation of a considerable number of cracks in the matrix region. The macroscopic manifestation of this phenomenon is an increase in the number and length of M-SPCs (Figure 4a).

In the boundary region, the lamellar loose structure functions as a diffusion channel for the escape of gases. As the rate of gas release increases, the initial short B-SPCs in the interface gradually expand and coalesce to form the longer cracks (Figure 4b). The formation of these cracks gives rise to alterations in the distribution of stress in the vicinity of the cracks, which in turn gives rise to the phenomenon of stress concentration at the edges of the cracks [39]. The aforementioned stress concentration serves to augment the stress at the crack tip, thereby facilitating the genesis and propagation of M-BPCs (Figure 3c). It can thus be concluded that the initiation of M-BPCs and the propagation of M-SPCs and B-SPCs, governed by carbonate decomposition reaction, constitute the prerequisite for thermal bursting behaviors in low-grade limestones.

3.2.3. High-Temperature Calcination Stage

The low-grade limestones underwent a complete mineral phase transformation upon being subjected to a temperature of 1050 °C during the calcination process (Figure 5). Based on the preceding analysis, the number and fraction of cracks remained relatively constant, whereas their lengths exhibited a notable increase (Figure 4). Therefore, the penetration of cracks is the principal manifestation of thermal bursting behavior at this stage.

For the matrix region, the main calcite phase, which possess tripartite crystal structure, are fully transformed into calcium oxide with a cubic crystal structure, resulting in a reduction in the tightness and strength of the calcined product. Thus, the cracks that had initially formed in the matrix region undergo rapid expansion between the calcium oxide grains, leading to the formation of through-length cracks.

For the boundary region, the length of B-SPCs is significantly greater than that observed during the mid-temperature stage (Figure 4b). Based on the thermal bursting behaviors and corresponding material characterization, the lamellar structure with dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) as the primary phase in the interfacial region demonstrates preferential deterioration properties under thermal loading. The initial decomposition temperature of dolomite is lower than the stabilization temperature range of calcite. This disparity in thermal stability results in a reduction in strength of the interfacial zone at an earlier stage in the heating process. Furthermore, the lamellar structure formed by the preferential growth of dolomite crystals along the specific crystal faces produces significant anisotropic effects during crack propagation. When the crack propagation direction is at a small angle to the interlayer interface, the weak bonding surface between the layers reduces the crack extension energy barrier through the interfacial debonding mechanism. And when the crack is perpendicular to the laminate structure, the stress field distribution at the crack tip is changed through the bridging toughening mechanism. This structure-directed crack extension path selection mechanism ultimately leads to a significant increase in the crack extension rate in the interfacial region compared to the homogeneous matrix region.

From the preceding results, the mechanisms by which thermal bursting occurs in low-grade limestones can be deduced, as illustrated in Figure 9. For the low-grade limestone examined in this study, the pronounced differences in microstructure, physical properties, and thermal characteristics between the calcite in the matrix region and the dolomite in the boundary region determine the manner of crack initiation and propagation. In addition to self-propagating cracks within the matrix region caused by hydration, the cracks tend to propagate along weaker grain boundaries or cleavage planes of dolomite phase, even penetrating into the brittle calcite matrix to form expansion paths. This crack propagation, governed by differences in microstructure and properties, constitutes the primary mechanism underlying the thermal bursting of low-grade limestones.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of thermal bursting mechanisms of low-grade limestones.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the thermal bursting behavior in low-grade limestones, and elucidates the underlying mechanisms governing crack evolution across different temperature stages. The primary conclusions are as follows:

- At the low-temperature stage, thermal bursting is primarily initiated by the vaporization of bound water. The moisture content of the specimens in matrix and boundary regions was 1.24% and 2.98%, respectively. This process leads to the formation and propagation of self-propagating cracks within the matrix (M-SPCs) and boundary regions (B-SPCs), at an approximate ratio of 2:1.

- During the mid-temperature stage, the decarbonation of carbonates generates increased gas pressure and induces crystalline phase transformations. This results in localized pore formation and volumetric shrinkage, which promotes the propagation of existing M-SPCs and B-SPCs and initiates new cracks propagating from boundaries into the matrix (M-BPCs). Compared to the previous stage, the crack lengths for M-SPCs and B-SPCs exhibited an increase of 69.2% and 182.5%, respectively. M-BPCs account for approximately 45.5% of the three crack types.

- Under high-temperature calcination, the complete decomposition of carbonates and the accompanying thorough phase transformation cause a substantial reduction in the mechanical strength of the limes. This enables the rapid, through-crack propagation of all three crack types, ultimately leading to severe thermal bursting and material disintegration, which is primarily attributed to the significant lengthening of M-SPCs and B-SPCs, which increased by 129.4% and 41.8%, respectively, compared to the mid-temperature stage.

- The thermal bursting of low-grade limestones is fundamentally governed by the distinct thermal and microstructural properties of calcite and dolomite. Crack propagation preferentially occurs along the weaker dolomitic boundaries and cleavage planes. The insights from this research provide a fundamental basis for developing strategies to mitigate thermal bursting in low-grade limestones during industrial calcination processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and C.A.; methodology, Y.T. and Z.X.; validation, Y.T., L.G. and X.Q.; formal analysis, Y.T.; data curation, Z.X., S.H. and B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T. and Z.X.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and C.A.; visualization, L.G.; supervision, X.Q., S.H. and B.C.; project administration, Y.T. and L.G.; funding acquisition, Y.T. and L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Science Foundation Project of Liaoning Province (2024-BS-229, 2024-BS-228), General Research Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (LJ212511430008, JYTQN2023448), Doctoral Research Initiation Fund Project of Liaoning Institute of Science and Technology (2505B01), and Project of College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (202611430038).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the internal policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TAI | Total acid insoluble |

| LOI | Loss on ignition |

| ILR | Ignition loss rate |

| ASR | Accumulation shatter rate |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

| TG/DTA | Thermogravimetric-differential thermal analysis |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| EDS | Energy dispersion spectrum |

| M-SPCs | Self-propagation cracks in the matrix region |

| B-SPCs | Self-propagation cracks in the boundary region |

| M-BPCs | Boundary-propagation cracks towards the matrix region |

References

- Lim, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, G.; Kim, J. Modeling of the wet flue gas desulfurization system to utilize low-grade limestone. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 37, 2085–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.W.; Yang, Z.Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.M.; Liu, H.Z.; Zhang, W.; You, C.F. Insights into the desulfurization mechanism of low-grade limestone as absorbent induced by particle size. Fuel 2021, 305, 121444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Sahu, L.; Chaurasia, B.; Nayak, B. Prospects of utilization of waste dumped low-grade limestone for iron making: A case study. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusti, P.; Barik, K.; Dash, N.; Biswal, S.K.; Meikap, B.C. Effect of limestone and dolomite flux on the quality of pellets using high LOI iron ore. Powder Technol. 2021, 379, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Sarkar, S.; Roy, T.K. A strategy for partial replacement of lime by limestone and its impact on basic oxygen furnace steelmaking. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 2400030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwik, K.; Broström, M.; Backlund, K.; Fjäder, K.; Hiljanen, E.; Eriksson, M. Thermal decrepitation and thermally-induced cracking of limestone used in quicklime production. Minerals 2022, 12, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.W.; Li, C.X.; Lu, H.; Xie, W. Limestone dissolution and decomposition in steelmaking slag. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2018, 45, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Zhou, X.Y.; Hu, C.L.; Wang, F.Z.; Hu, S.G. Role of partial limestone calcination in carbonated lime-based binders. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 183, 107572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’vov, B.V. Mechanism and kinetics of thermal decomposition of carbonates. Thermochimica Acta 2002, 386, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, K.; Carlborg, M.; Eriksson, M.; Broström, M. Characterization of limestone surface impurities and resulting quicklime quality. Minerals 2024, 14, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.M.; Mi, Z.J. Production practice of calcination of high quality metallurgical lime from magnesian limestone of Majiagou formation. Mod. Min. 2022, 633, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, H.; Hassanpour, S.; Saboonchi, A. Thermal energy analysis of a lime production process: Rotary kiln, preheater and cooler. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 114, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitsangiam, P.; Suwan, T.; Wattanachai, P.; Tangchirapat, W.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Fan, M. Investigation of hard-burn and soft-burn lime kiln dust as alternative materials for alkali-activated binder cured at ambient temperature. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14933–14943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.X.; Wang, S.H.; Li, C.X.; Sun, H.K.; Zhang, Y. Decomposition mechanism and calcination properties of small-sized limestone at steelmaking temperature. Processes 2023, 11, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.M.; Fu, T.L. Effect of mineral crystal structure on thermal bursting of limestone during calcination. Ind. Furn. 2022, 44, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Moropoulou, A.; Bakolas, A.; Aggelakopoulou, E. The effects of limestone characteristics and calcination temperature to the reactivity of the quicklime. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollimore, D.; Dunn, J.G.; Lee, Y.F.; Penrod, B.M. The decrepitation of dolomite and limestone. Thermochim. Acta 1994, 237, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivrikaya, O. A study on the physicochemical and thermal characterisation of dolomite and limestone samples for use in ironmaking and steelmaking. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2018, 45, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Z.; Shi, Y.L. Analysis on breaking mechanism and influencing factors of breakable limestone. Refract. Lime 2020, 45, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vola, G.; Bresciani, P.; Rodeghero, E.; Sarandrea, L.; Cruciani, G. Impact of rock fabric, thermal behavior, and carbonate decomposition kinetics on quicklime industrial production and slaking reactivity. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 136, 967–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.B.; Zhao, G.C.; Zhang, C.R. Research on calcination and bursting characteristics of Ordovician Majiagou limestone. Refract. Lime 2019, 44, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.X.; Kong, X.X.; Yang, Y.P.; Zhang, J.G.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, L.; Yuan, X.D. Multi-source genesis of continental carbonate-rich fine-grained sedimentary rocks and hydrocarbon sweet spots. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Huang, F.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y. Microscopic characteristics and thermodynamic property changes in limestone under high-temperature treatment. Mater. Lett. 2024, 356, 135558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vola, G.; Ardit, M.; Sarandrea, L.; Brignoli, G.; Natali, C.; Cavallo, A.; Bianchini, G.; Cruciani, G. Investigation and prediction of sticking tendency, blocks formation and occasional melting of lime at HT (1300 C) by the overburning test method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 294, 123577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Han, S.; Han, Z.; Yan, C.; Xue, M.; Liu, Z.; Chen, F. Initiation and propagation behaviour of cohesive cracks at high temperatures: A dynamic experimental study. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 276, 108923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murru, A.; Freire-Lista, D.M.; Fort, R.; Varas-Muriel, M.J.; Meloni, P. Evaluation of post-thermal shock effects in Carrara marble and Santa Caterina di Pittinuri limestone. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 114, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.F.; Xue, Z.L.; Li, J.L. Kinetics of thermal decomposition reaction of limestone for flash heating of limestone at high temperature. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 44, 754–762. [Google Scholar]

- Bahulayan, A.; Santhanam, M. Hydration, phase assemblage and microstructure of cementitious blends with low-grade limestone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, F.W.; Sharp, J.H.; Tinsley, D.M.; McIntosh, R.M. The effect of procedural variables on TG, DTG and DTA curves of calcium carbonate. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1991, 37, 2003–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, F.; Bragança, S.R. Thermogravimetric analysis of limestones with different contents of MgO and microstructural characterization in oxy-combustion. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 561, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbalagan, G.; Rajakumar, P.; Gunasekaran, S. Non-isothermal decomposition of Indian limestone of marine origin. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2009, 97, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.O.; Sun, J.; Ma, Y.K.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.T.; Wang, E.Y. Research on the influence mechanism of moisture content on macroscopic mechanical response and microscopic evolution characteristic of limestone. Buildings 2024, 14, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, H.; Paramban, S. Investigating the effects of specimen diameter on the relationships between mechanical and physical properties of limestone. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, S.; Hoseinie, S.H.; Ghasemi, E.; Sherizadeh, T. Effect of quantitative textural specifications on Vickers hardness of limestones. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Chen, H.; Guo, Y.; Rao, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of loading modes and temperature on fracture properties of limestone. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Oterkus, S.; Oterkus, E. Investigation of the effect of porosity on intergranular brittle fracture using peridynamics. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2020, 28, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Suzuki, K.; Ito, S.; Sato, K.; Takebe, T. Decomposition of synthesized ettringite by carbonation. Cem. Concr. Res. 1992, 22, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.F.; Liu, K.; Chen, F.; Wang, S.; Zheng, F.Q.; Yang, L.Z.; Liu, Y.J. Effect of basicity on the reduction swelling behavior and mechanism of limestone fluxed iron ore pellets. Powder Technol. 2021, 393, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.J.; Hu, J.H.; Wen, G.P.; Xu, X.; Zeng, P.P. Numerical simulation of micro crack evolution and failure modes of limestone under uniaxial multi-level cyclic loading. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.