Abstract

Managing tailings efficiently remains a critical significant challenge in the mining sector, affecting water usage, industrial process reuse, and environmental safety. Poor disposal practices can lead to water pollution, high infrastructure expenses, and the need for long-term monitoring. To address these challenges, thickening is commonly employed in tailings dewatering to improve particle aggregation and water clarity. In this regard, this study investigates the use of soy lecithin as a biodegradable alternative reagent for iron ore tailings thickening. Bench-scale tests assessed the impact of pH and reagent dosage on sedimentation speed and water clarity. Under optimal conditions (150 g/t at pH 5), there was a 110% increase in sedimentation rate and a 60% decrease in clarified water turbidity compared to untreated tailings. These findings highlight the potential of soy lecithin as a sustainable solution for mineral tailings treatment, providing both environmental and operational advantages, and fostering innovation in the mining industry.

1. Introduction

Mining processing projects are associated with a multitude of environmental challenges, particularly concerning the disposal of tailings, which are typically stored in dams. These dams necessitate extensive land use, pose risks of water contamination, incur significant construction costs, and complicate long-term monitoring in compliance with environmental regulations. In response to these challenges, research on tailings disposal in the form of paste is being conducted in various countries, as this method generally facilitates high water recovery and recirculation, reduces capital and operational costs, and minimizes environmental impact [1,2,3,4].

Thickening and filtration have long been recognized as critical alternatives for tailings dewatering [5,6,7]. Thickening is a solid–liquid separation process based on sedimentation, where suspended particles settle at the bottom of the tank, resulting in a denser slurry. The primary objective of operating this unit is to concentrate dilute pulps into slurries with higher solid content, considering both the target solids concentration and the sedimentation rate of the particles [8]. This technique is extensively employed in nearly all wet processing plants for iron ore in Brazil, where it is crucial for dewatering pellet feed concentrates, tailings, and slimes, as well as for adjusting slurry density to ensure efficiency in downstream operations [9].

In thickening processes, the addition of coagulants or flocculants is essential to accelerate particle settling, enhance water clarity, and allow for the use of smaller thickeners, thereby improving overall process efficiency [10,11]. This is particularly pertinent because the fine size and surface charges of mineral tailings particles often result in impractically long settling times for industrial applications. Currently, polyacrylamides are the most widely used commercial polymers in the mineral industry due to their effectiveness, since the polymer forms large flakes that quickly settle at the bottom of the thickeners [12]. However, increasing pressure for cost-effective and environmentally friendly reagents has spurred research into alternative compounds that, although less studied, exhibit promising potential [12,13,14,15,16,17].

In this context, soy lecithin, a by-product of degummed vegetable oil production, has garnered attention as a versatile emulsifier commonly utilized in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Commercially, the term refers to a mixture of lipids with distinct physicochemical properties, while chemically it is often associated with phosphatidylcholines [18,19,20]. Furthermore, soy lecithin is biodegradable and non-toxic, classified both in the US by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and in the European Union, under the number EE322, as safe for humans [21]. Its emollient, emulsifying, and solubilizing properties, combined with solubility in both polar and non-polar media, confer high industrial applicability and increasing technological value [22,23,24].

After several searches across a wide range of existing research databases, we found only one specific study involving soy lecithin in the mining industry, where the authors [25] used it as a collector in the reverse flotation of phosphate ore. The authors reported that lecithin shows considerable potential as an efficient and environmentally sustainable collector for selective flotation in phosphate concentration circuits. Cunha et al. [26] investigated the performance of soy lecithin as a dispersant at a dosage of 300 g/t; however, under those conditions, the reagent promoted particle aggregation. In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate the impact of soy lecithin, a biodegradable alternative reagent, on the thickening behavior of iron ore tailings.

2. Materials and Methods

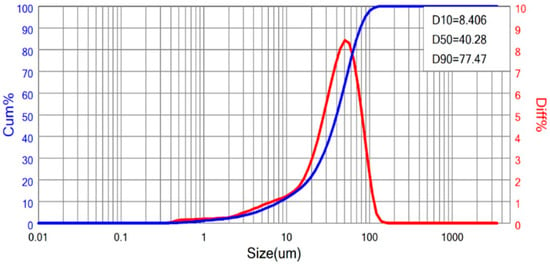

The sample used in this study consisted of iron ore tailings collected from Itatiaiuçu, Minas Gerais, Brazil, representing the feed to the tailings thickener of the mineral processing plant. Martins et al. [27] reported that the material consists predominantly of silica and iron, mainly as quartz (≈73%) and hematite (≈18%). Chemical composition was determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) using a Shimadzu EDX-720 spectrometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The tailings exhibit a fine particle size distribution, with d90 ≈ 77 µm (Figure 1), classified as fine (10–100 µm) according to Valadão and Araujo [28], and a density of 2.82 g/cm3. Particle size distribution was obtained by laser diffraction using a Bettersize S3 Plus analyzer (Bettersize Instruments Ltd., Costa Mesa, CA, USA) under wet conditions, with the samples analyzed as aqueous suspensions. Density was measured using a gas pycnometer (ACP Instruments, ACP Manufacturing, Commerce and Analytical Equipment Services Ltd., São Caetano do Sul, Brazil). Sample preparation and particle size analysis were performed according to the method proposed by Sampaio et al. [29].

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution of the iron ore tailing.

The material consisted of tailings, a mixture of different minerals. The net surface charge of the particles was measured using a Malvern Panalytical Zetasizer Nano (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Worcestershire, UK). As the instrument analyzes only particles smaller than 20 µm, approximately 50 g of the sample were ground with a McCrone Micronising Mill (McCrone Scientific, The McCrone Group, Westmont, IL, USA) to obtain the required fraction. Potassium chloride (KCl, 10−2 mol/L) was used as the inert electrolyte, and pH adjustments were performed with HCl and KOH (0.05 mol/L each).

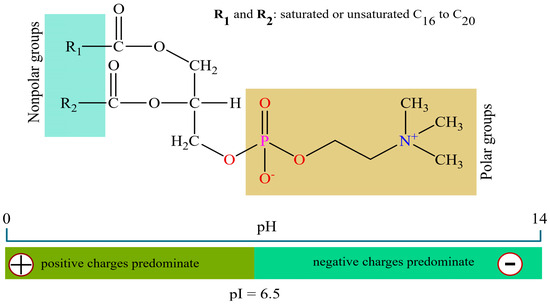

Soy lecithin was supplied by Candon Aditivos para Alimento (Marechal Cândido Rondon, Paraná, Brazil). The product has a viscosity of 80–200 poise, an amber color, saturated fatty acids (15%), monounsaturated fatty acids (13%), polyunsaturated fatty acids (42%), 1700 mg of phosphorus, and 80 mg of calcium. The lecithin solution was prepared following the procedure described by Bailey et al. [30] and Waszcsynskyj [31], with modifications. The reagent was then prepared as a 0.5% (w/w) aqueous solution prior to testing. A total of 100 g of soybean lecithin was heated to 50 °C at a 1:2 ratio (one part solute to two parts solvent) under continuous stirring at 150 RPM using a microprocessed magnetic heater, until complete homogenization was achieved. Figure 2 shows the structural formula of lecithin and its pH-dependent charge distribution relative to the isoelectric point (IP). Based on Chain and Kemp [32], the extrapolated IP is 6.5 ± 0.2, below which positive charges prevail and above which negative charges dominate, influencing its interaction with negatively charged particle surfaces during flocculation. The reported IP refers to freshly prepared solutions, with discrepancies relative to the theoretical value calculated from the ionization constants of choline and glycerophosphoric acid, mainly due to the rapid decomposition of lecithin, even under freshly prepared conditions.

Figure 2.

Structural formula of lecithin and charge distribution as a function of pH relative to its isoelectric point.

Settling tests were performed using graduated cylinders, following the procedure described by França and Casqueira [33], with a pulp containing 20% solids. When required, pH adjustment was carried out using 1 M hydrochloric acid or 10% (w/w) sodium hydroxide solutions, and monitored with a Hanna benchtop pH meter (model M-7962). At the end of each test, clarified water samples were collected and analyzed for turbidity using a portable Hanna turbidimeter (model HI 93703).

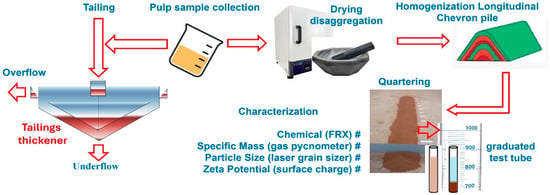

A full factorial experimental design (2k) with three replicates at the central points was applied, totaling seven runs. The independent variables considered were reagent dosage (50 and 150 g/t) and pH (5 and 8), while the response variables were settling rate and turbidity. These parameters were chosen based on preliminary tests, which showed that lower dosages resulted in decreased sedimentation rates, while higher dosages caused redispersion of ultrafine particles and excessive turbidity, preventing accurate measurement of the clarified interface. Statistical analyses and response optimization were performed using Minitab Statistical Software 21, with a significance level of 5%. Figure 3 shows the procedures used during the research, from the collection of iron ore tailings to the final settling tests, including their characterizations.

Figure 3.

Methodological flowchart from sample preparation to sedimentation experiments.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 1 presents the outcomes of the settling tests, highlighting the effects of pH and reagent dosage on turbidity and settling velocity. With respect to turbidity, the lowest values were obtained under acidic conditions (pH 5), with a marked reduction as the dosage increased from 50 to 150 g/t in tests 1 and 2. This behavior suggests a more efficient capture of fine particles at higher dosages. Regarding settling velocity, the highest value was observed in test 2 (pH 5 and 150 g/t), confirming the trend that higher reagent dosages promote the formation of larger aggregates, which settle more rapidly due to increased particle–particle interactions and reduced surface charge effects [34]. It can be inferred that the higher sedimentation speed, provided by the greater amount of soy lecithin, occurred due to the formation of larger flakes, which in themselves, sedimented faster. Along the same lines, better clarification of the liquid may have occurred due to the smaller number of particles on the surface, since the number of particles in equilibrium with the fluid medium may have reduced due to their aggregation into the flocs. In this sense, Valência [35] commented that particles dispersed in a liquid medium, in addition to tending to interact with each other, are also subject to forces acting on the surface, especially those with particle sizes smaller than 100 μm. The evidence also showed that agglomeration may have been caused by particles that presented attractive forces greater than repulsive ones, as described by Oliveira et al. [36] in their work on Particle Dispersion and Packing. It is important to make it clear that these factors can change, both with changes in pH and with the values of the isoelectric point of the medium.

Table 1.

Results of the graduated cylinder tests.

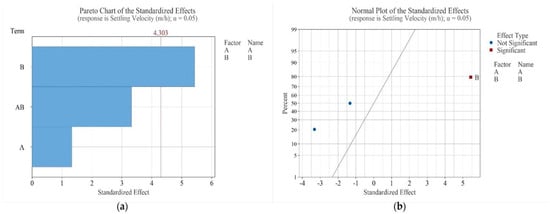

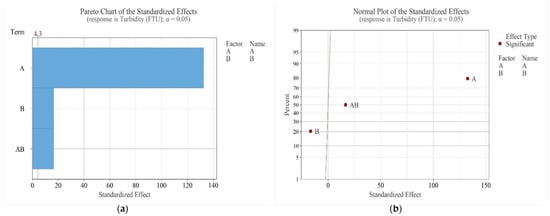

Figure 4a shows the Pareto Chart for settling velocity. Variables and interactions with bars extending beyond the dashed line are considered significant at the studied levels, indicating that only reagent dosage (B) had a statistically significant effect (p < 0.05), while pH (A) and its interaction with dosage (AB) were not significant. Figure 4b, the Normal Plot of Standardized Effects, confirms that reagent dosage has the strongest positive influence on settling velocity. Effects located to the right of the normal line increase the response when the factor level is raised, while those to the left decrease it. Practically, increasing the soy lecithin dosage from the lower to the higher level results in higher settling velocities.

Figure 4.

Pareto Chart (a) and Normal Plot of Standardized Effects (b) for settling velocity (Factor A—pH, B—dosage).

Figure 5a shows the Pareto Chart and Figure 5b the Normal Plot of Standardized Effects for turbidity. Both pH (A) and reagent dosage (B) had statistically significant effects (p < 0.05), as did their interaction (AB). Factor A had the strongest positive influence, while factor B exerted a negative effect. Practically, increasing pH or the interaction of pH and dosage increases turbidity, whereas increasing reagent dosage alone reduces turbidity.

Figure 5.

Pareto Chart (a) and Normal Plot of Standardized Effects (b) for turbidity (Factor A—pH, B—dosage).

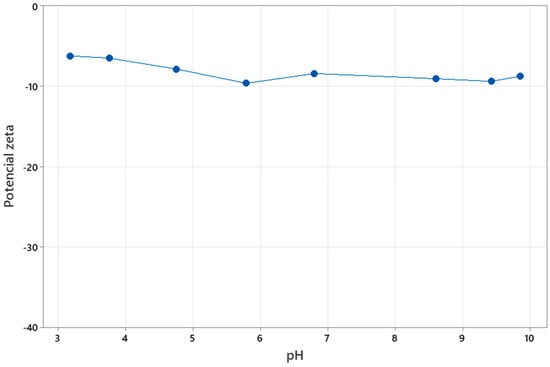

The increase in turbidity with rising pH can be explained by the behavior of the tailings’ surface charge and the amphoteric nature of lecithin used as a reagent. According to the zeta potential curve reported by Figure 6, the tailings, composed predominantly of quartz, exhibit a negative surface charge in the pH range of 3–10. Lecithin, in turn, is an amphoteric reagent, whose main phospholipids are phosphatidylcholines and phosphatidylethanolamines [25]. At low pH (around 4–5), lecithin molecules are positively charged, allowing for electrostatic adsorption onto tailing surfaces and favoring aggregation. However, as pH increases, lecithin becomes predominantly anionic, enhancing electrostatic repulsion between particles [33]. This shift reduces aggregation efficiency and increases dispersion, resulting in higher turbidity at alkaline conditions.

Figure 6.

Net surface charge of the tailings.

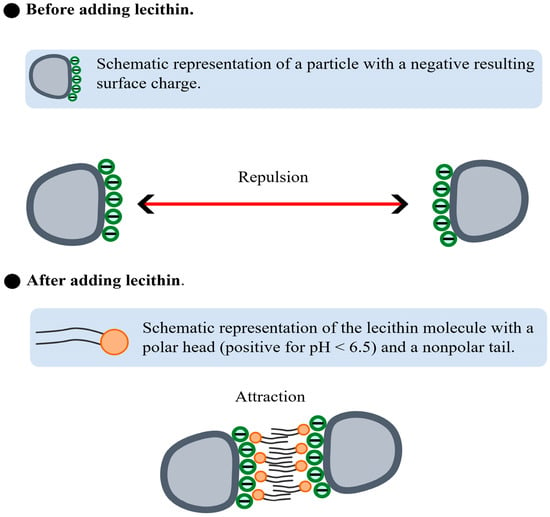

Figure 7 depicts the proposed mechanism of lecithin action. Initially, particles with a net negative surface charge repel each other, thereby hindering aggregation. Upon lecithin addition at pH < 6.5, favorable interactions occur between the positively charged region of lecithin and the negatively charged particle surfaces. Once the particles are “coated” with lecithin molecules, the nonpolar tails of lecithin interact through hydrophobic affinity, leading to the aggregation of particles that were previously dispersed in solution.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the interaction between suspended particles before and after lecithin addition.

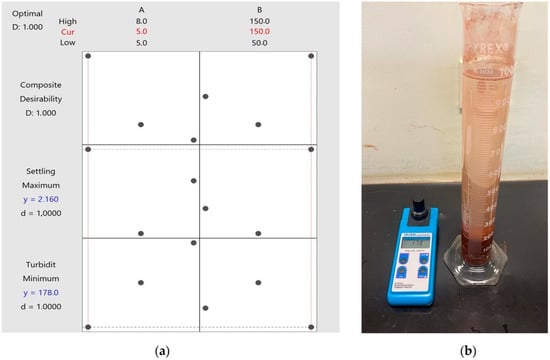

To optimize the process, it is essential to consider both variables simultaneously, aiming to minimize turbidity while maximizing settling velocity. Figure 8a presents the optimized projection generated by Minitab, indicating that the optimal operating conditions correspond to the maximum dosage of 150 g/t and the minimum pH of 5. These parameters, shown in Figure 8b, were analyzed in experiment 2, resulting in a settling velocity of 2.16 m/h and a turbidity of 178 FTU.

Figure 8.

Optimization plot for the response variables turbidity and settling velocity (a) and Settling test with 150 g/t of soy lecithin at pH 5 (b).

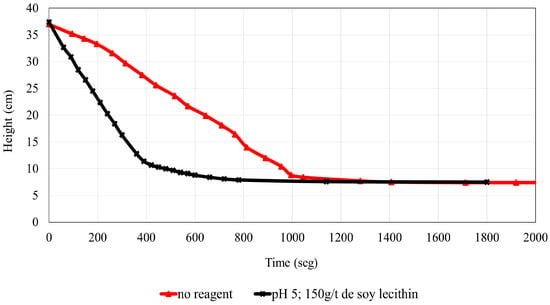

The settling velocity of the iron ore tailings without the addition of soy lecithin was 1.02 m/h, with a turbidity of 529 FTU. Figure 9 compares test 2 (150 g/t of soy lecithin) with the test conducted without reagent addition at the natural pH (approximately 6.5). An increase of approximately 110% in settling velocity and a 60% reduction in turbidity were observed. A steeper slope indicates faster downward movement of the solid–liquid interface, characteristic of a more intense sedimentation stage. The highest sedimentation rate was obtained for the curve with the steepest slope, resulting from the addition of soy lecithin, which enhanced the flocculating effect.

Figure 9.

Comparison of settling curves in the absence and presence of soy lecithin.

From a practical standpoint, the simultaneous reduction in turbidity and increase in settling velocity are particularly relevant for industrial tailings management, as they imply not only improved water recovery but also reduced demand for thickener area and enhanced operational efficiency. Nevertheless, it is important to balance the benefits of higher dosages against reagent consumption and associated costs. In this regard, the use of soy lecithin as a biodegradable and potentially cost-competitive reagent offers a promising pathway for sustainable mineral processing, aligning with the growing demand for eco-friendly alternatives to synthetic polymers [25].

These results indicate that acidic conditions, combined with higher dosages of soy lecithin, improve both water clarification and settling kinetics, thereby enhancing the overall dewatering efficiency of iron ore tailings. However, to further improve this process, additional studies are needed to optimize tailings dewatering, particularly by evaluating lecithin performance with different types of residues, under varying process conditions (e.g., conditioning time and agitation intensity), and in combination with other reagents.

4. Conclusions

Soy lecithin proved to be an effective and biodegradable reagent for improving iron ore tailings thickening. Dosage strongly influenced settling velocity, while both dosage and pH affected turbidity. The optimum condition (150 g/t at pH 5) achieved a settling velocity of 2.16 m/h and reduced turbidity to 178 FTU.

The results suggest that the combined effect of acidic conditions and higher dosages of soy lecithin significantly improves the dewatering performance of iron ore tailings. These findings highlight the potential of this reagent not only to optimize thickening processes but also to contribute to greener mineral processing practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.d.S.O. and M.G.J.; methodology, I.H.B.P. and M.d.S.O.; formal analysis, I.H.B.P., N.J.P. and M.d.S.O.; resources, I.H.B.P. and L.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.H.B.P. and L.A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.d.S.O. and M.G.J.; supervision, M.d.S.O. and M.G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The experimental data generated and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica de Minas Gerais (CEFET-MG), Campus Araxá, for providing the infrastructure and laboratory facilities to carry out this research. Special thanks are extended to the Laboratory of Mineral Processing for technical support during the experimental procedure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Vargas, C.C.; Campomanes, G.P. Practical experience of filtered tailings technology in Chile and Peru: An environmentally friendly solution. Minerals 2022, 12, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamraoui, L.; Bergani, A.; Ettoumi, M.; Aboulaich, A.; Taha, Y.; Khalil, A.; Neculita, C.M.; Benzaazoua, M. Towards a circular economy in the mining industry: Possible solutions for water recovery through advanced mineral tailings dewatering. Minerals 2024, 14, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.H.; Corser, P.G.; Garces, E.E.P.; Lopez, C.T.E.; Vandekeybus, J. A comparison of alternative tailings disposal methods—The promises and realities. In Proceedings of the First International Seminar on the Reduction of Risk in the Management of Tailings and Mine Waste, Perth, Australia, 29 September–1 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.C.; Silva, E.M.S.; Silva Júnior, A.P.; Arruda, J.P.A.; Vaz, V.R.A. Mineral paste production from phosphate rock tailings. Rev. Esc. De Minas 2015, 68, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Edraki, M.; Malekizadeh, A.; Schenk, P.M.; Berry, L. Introducing the hydrate gel membrane technology for filtration of mine tailing. Miner. Eng. 2019, 135, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. Towards the Elimination of Conventional Surface Slurried Tailings Storage Facilities, Tailings and Mine Waste Management for the 21st Century; Australian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Jolimont, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barreda, R.H.O.; Valadão, G.E.S. Flocculant polymers for disposal of thickened tailings. Holos 2020, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, E.A.; Chaves, A.P. Efeito das dimensões das provetas no dimensionamento de espessadores. In Proceedings of the XVII Encontro Nacional de Tratamento de Minérios, Águas de São Pedro, Brazil, 23–26 August 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, Y.J.G.L.; Oliveira, A.C. Ensaios de espessamento com finos de minério de ferro. In Proceedings of the XXIX Encontro Nacional de Tratamento de Minérios, Armação dos Búzios, Brazil, 25–28 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, C.; Fawell, P.; Costine, A. Optimising the activity of acrylamide-based polymer solutions used to flocculate mineral processing tailings suspensions—A review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 199, 214–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Ghaedi, A.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Sam, A.; Entezari-Zarandi, A. The effect of residual flocculants in the circulating water on dewatering of Gol-e-Gohar iron ore. Miner. Eng. 2022, 179, 107440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, G.P.; Giudici, R.; Soares, J.B.P. Exploring alternatives to polyacrylamide: A comparative study of novel polymers in the flocculation and dewatering of iron ore tailings. Polymers 2023, 15, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding, M. Analytical Methods for Polymers and Their Oxidative by-Products; AWWA, Ed.; AWWA Research Foundation: Denver, CO, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bolto, B.; Gregory, J. Organic polyelectrolytes in water treatment. Water Res. 2007, 41, 2301–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallevialle, J.; Bruchet, A.; Fiessinger, F. How safe are organic polymers in water treatment? J. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 1984, 76, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.M. The carcinogenicity of acrylamide. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2005, 580, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, S.C.A.; Loayza, P.E.V.; Brocchi, E.A. Estudo da aplicação de polímeros naturais (ácido húmico e quitosana) na floculação de polpas minerais. In Proceedings of the XXVI Encontro Nacional de Tratamento de Minérios, Poços de Caldas, Brazil, 18–22 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.Y.; Park, S.E.; Chun, H.S.; Rho, J.R.; Ahn, S. Phospholipid composition analysis of krill oil through HPLC with ELSD: Development, validation, and comparison with 31p nmr spectroscopy. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 107, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W., Jr.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G.J.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Safety assessment of lecithin and other phosphoglycerides as used in cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 5S–25S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, G.D.; Alberici, R.M.; Pereira, G.G.; Cabral, E.C.; Eberlin, M.N.; Barrera-Arellano, D. Direct characterization of commercial lecithins by easy ambient sonic-spray ionization mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1855–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, A.R.; Assis, L.M.; Machado, M.I.R.; Souza, L.A. Importance of lecithin for encapsulation processes. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2014, 8, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejon, L.V. Quality Parameters in the Clarification of Soy Lecithin. Ph.D. Dissertation, Faculty of Chemical Engineering, Federal University of Uberlândia, Uberlândia, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, P.V.; Nitesh, K.; Chandrashekhar, H.R.; Mallikarjuna-Rao, C.; Venkata-Rao, J.; Udupa, N. Effect of lecithin and silymarin on d-galactosamine induced toxicity in isolated hepatocytes and rats. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2010, 25, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, E. An Introduction to Food Colloids, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, Z.; Assimeddine, M.; Abdennouri, M.; Barka, N.; Sadiq, M. Lecithin as an ecofriendly amphoteric collector foaming agent for the reverse flotation of phosphate ore. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 200, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.V.; Silva, L.A.; Melchior, S.T.B.; Junior, M.G.; Pereira, C.A.; Pires, N.J.; Oliveira, F.T.; Oliveira, M.S. Study of Particle Dispersion Degree in Phosphate Ore Slurry. In Proceedings of the Congresso Brasileiro de Fosfatos, Caldas Novas, Brazil, 5–8 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.; Oliveira, M.S.; Testa, F.G. Influência de floculantes nas características reológicas e de sedimentação de polpas de rejeito de minério de ferro. Tecnol. Em Metal. Mater. E Mineração 2024, 21, e2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadão, G.E.S.; Araujo, A.C. Introdução ao Tratamento de Minérios, 1st ed.; UFMG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, J.A.; França, S.C.A.; Braga, P.F.A. (Eds.) Tratamento de Minérios: Práticas Laboratoriais; CETEM: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A.E.; Swern, D.; Formo, M.W.; Applewhite, T.H. Bailey’s Industrial Oil and Fat Products, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 1, p. 841. [Google Scholar]

- Waszcsynskyj, N. Lecitina. Bol. Cent. Pesqui. Process. Aliment. 1984, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chain, E.; Kemp, I. The isoelectric points of lecithin and sphingomyelin. Biochem. J. 1934, 28, 2052–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, S.C.A.; Casqueira, R.G. Ensaios de sedimentação. In Tratamento de Minérios: Práticas Laboratoriais, 1st ed.; Sampaio, J.A., França, S.C.A., Braga, P.F.A., Eds.; CETEM/MCTI: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007; pp. 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Baltar, C.A.M. Agregação na separação sólido-líquido. In Tratamento de Minérios, 6th ed.; Luz, A.B., França, S.C.A., Braga, P.F.A., Eds.; CETEM/MCTIC: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018; Chapter 12; pp. 513–545. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, G.A. Estudo das Características de Dispersão de Suspensões de Carbonato de Cálcio. Master’s Thesis, Escola Politécnica, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.R.; Studart, A.R.; Pileggi, R.G.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Dispersão e Empacotamento de Partículas: Princípios e Aplicações em Processamento Cerâmico, 1st ed.; Fazendo Arte Editorial: São Paulo, Brazil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.