Abstract

Exceptionally high chlorine contents (up to 1.57%) occur in the Middle Jurassic coal seams of the Sha’erhu area, Turpan–Hami Basin, Northwest China, making this coalfield one of the most Cl-enriched coal occurrences reported in China. However, the occurrence modes and enrichment pathways of chlorine in such coals remain insufficiently characterized. In this study, we integrated coal quality analyses, mineralogical characterization (XRD and SEM–EDS), geochemical measurements (XRF and ICP–MS), and an integrated Sequential Chemical Extraction Procedure–High-Temperature Combustion Hydrolysis approach to systematically elucidate the occurrence forms and enrichment processes of chlorine in the Sha’erhu coals. The results indicate that chlorine predominantly occurs in water-soluble form (78.3%–84.7% of total Cl), followed by a minor adsorbed fraction, whereas carbonate-bound and organic/silicate-bound Cl are negligible. The mineral assemblages and geochemical indicators jointly suggest that the coal seams were deposited in a semi-closed, strongly evaporative lacustrine–peat mire system, which subsequently experienced structurally controlled brine intrusion. Chlorine enrichment is attributed to the combined effects of primary evaporative concentration, externally sourced brines migrating through tectonic conduits, and diagenetic fluid activities. This study provides an important case for understanding the genesis of High-chlorine coals in continental basins.

1. Introduction

Chlorine, as one of the most mobile and potentially harmful elements in coal, exhibits significant environmental and engineering sensitivity during energy utilization. Both the concentration of chlorine in coal and its occurrence modes among different hosting phases directly control chlorine release during combustion and gasification, while also strongly affecting equipment corrosion, catalyst poisoning, and the formation of chlorinated organic pollutants such as dioxins [1,2,3,4]. The occurrence of chlorine in coal is complex and diverse, encompassing inorganic salts, chlorinated silicates, carbonates, sulfides, as well as dissolved Cl in pore water and organically bound Cl [5]. Different chlorine species display substantial variations in mobility, geochemical behavior, and retention capacity [6,7,8]. Therefore, systematically characterizing the multiphase occurrence of chlorine in coal is fundamental for understanding its subsequent environmental behavior and constitutes a key prerequisite for elucidating the genesis of High-chlorine coals.

Globally, Cl-rich coal seams are often associated with marine depositional environments or deep brine activities. For instance, the high Cl enrichment in certain Carboniferous coals in the United Kingdom has been attributed to Cl-rich seawater introduced during marine transgression events [9,10], whereas some deep High-chlorine coals in the Illinois Basin, USA, are believed to result from the migration and evolution of basin brines [11]. These brines are characterized by high Cl− activity, strong permeability, and long-term confined hydrological conditions, favoring the retention and fixation of water-soluble Cl in coal. In addition to marine deposition and brine intrusion, evaporative processes represent another important mechanism for Cl enrichment. For example, Lin et al. [12] reported that evaporation significantly increased Na+ and Cl− concentrations in the waters of the Yan’an Formation coals in the southern Ordos Basin, China. These cases highlight the diverse enrichment patterns of chlorine under different geological forces. Notably, in many Meso-Cenozoic continental basins widely distributed in northwestern China, coal seams with anomalously high Cl contents (typically >0.3%) have also been reported [13,14]. However, as the coal-forming environments in this region are predominantly continental, whether the high Cl content is controlled by deep brine activity or evaporative concentration remains to be fully clarified.

Accurately elucidating the mechanisms of Cl enrichment in coal remains challenging. In surficial environments, chlorine mainly migrates as highly mobile chloride ions (Cl−), and its eventual accumulation reflects the combined effects of primary depositional conditions (e.g., paleosalinity, hydrological characteristics) and subsequent diagenetic modifications (e.g., fluid activities, water-rock interactions) [15,16]. Traditional bulk Cl analyses are unable to distinguish between different chemical forms, thereby limiting the tracing of migration and fixation pathways. In recent years, sequential chemical extraction techniques have emerged as effective tools for characterizing elemental occurrence, allowing quantitative identification of water-soluble, exchangeable, carbonate-bound, and organically bound Cl species, and providing key insights into the activation, migration, and retention mechanisms of chlorine [17,18,19]. Furthermore, integrating mineralogical features (e.g., the presence of gypsum in strongly evaporative settings and vein-type mineral intrusions) with sensitive geochemical proxies (e.g., B/Ga and Sr/Ba ratios) provides reliable indicators for reconstructing paleowater salinity and identifying subsequent fluid activities [20,21].

The Middle Jurassic coal seams in the Sha’erhu (SEH) area of the Turpan–Hami Basin, Xinjiang, represent a typical example of continental High-chlorine coals. Previous exploration data indicate that the Cl content in these coal seams generally exceeds the 0.3% threshold for High-chlorine coals, with some samples reaching up to 1%, among the highest values reported both domestically and internationally. Nevertheless, the dominant occurrence forms, sources, and key controlling factors of anomalous Cl enrichment in this region remain poorly understood and lack systematic explanation.

Based on the above scientific questions and current knowledge, this study focuses on the Cl-rich coal seams of the Xishanyao Formation in the Luxin mining area of the SEH region. A comprehensive approach integrating coal quality and lithofacies analyses, mineralogical characterization (XRD and SEM-EDS), whole-rock geochemistry (XRF and ICP-MS), and chlorine-targeted sequential chemical extraction combined with high-temperature combustion hydrolysis (SCEP-HTCP) was employed, with the following objectives: (1) to accurately characterize the multiphase occurrence and relative distribution of chlorine in High-chlorine coals; (2) to reconstruct the original depositional environment of the coal seams and identify the properties and activity of diagenetic fluids; and (3) to determine the key geological processes controlling anomalous Cl enrichment, thereby establishing a comprehensive model explaining the genesis of High-chlorine coals in the SEH area. This study provides theoretical insights into the geochemical cycling of Cl in continental basins and offers a scientific basis for environmental risk assessment and green exploitation of Cl-rich coal resources in this region.

2. Geological Setting

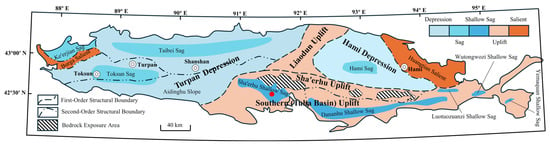

The Luxin coal mine is situated in the eastern part of the SHE shallow sag, on the southern margin of the central Turpan Basin, Northwest China (Figure 1). The mining area is bounded to the north by the SHE uplift and to the east by a weakly north–south trending basement uplift and the Danaanhu sag. Quaternary deposits extensively cover the area, with few outcrops of bedrock. Exposed strata mainly include the Lower Permian Albazai Formation, Upper Permian Kule Formation, Middle Jurassic Xishanyao Formation, and Toutunhe Formation. Among these, the Middle Jurassic Xishanyao Formation represents the primary coal-bearing strata in the study area (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Tectonic map of the Turpan–Hami Basin and the location of the Luxin Mining Area.

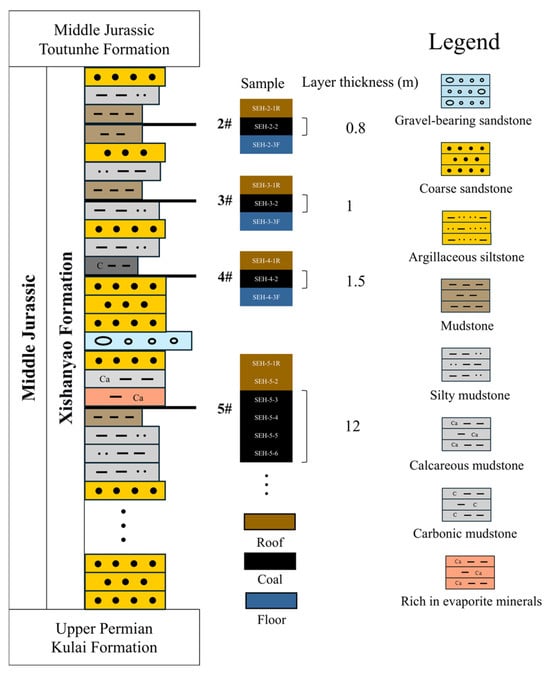

Figure 2.

Stratigraphic column of the study area showing coal seam positions, sampling locations, and sample IDs (internal data).

The Upper Permian Kule Formation is distributed in the northern part of the mining area and comprises a lacustrine–fluvial clastic sequence dominated by gray-yellow to gray-green calcareous sandstones, conglomerates, and silty mudstones, intercalated with minor black shale, stacked limestone, and limonite lenses. It contains abundant plant fossils and silicified wood. This formation unconformably overlies the underlying Albazai Formation and is in turn unconformably overlain by Jurassic strata. The Middle Jurassic Xishanyao Formation reaches a maximum thickness of 617.34 m, with an average thickness of approximately 475.6 m, and rests unconformably on the underlying strata and middle Variscan intrusive rocks. Based on lithological characteristics and depositional cycles, the Xishanyao Formation can be subdivided into lower, middle, and upper lithofacies units. The lower and upper units are mainly composed of fluvial–lacustrine clastic deposits with limited coal development, whereas the middle unit constitutes the main coal-bearing section, with a thickness ranging from 32.89 to 318.40 m, comprising 2–34 coal seams. Individual coal seam thickness generally exceeds 0.3 m, with an average cumulative thickness of 91.62 m. The dominant lithologies include interbedded gray-white siltstones, sandstones, and thick black coal seams, with intercalations of light gray-green mudstone in the upper part and gray-black carbonaceous mudstone and siderite-rich thin layers in the lower part. The coal seams investigated in this study include Seams 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the middle unit, which are relatively stable and representative of the formation. The lithological assemblage reflects the energy variations and redox fluctuations of a lacustrine–peat mire depositional system [22].

Structurally, the SEH shallow sag at the southern margin of the Turpan Basin is generally a broad, gentle, near east–west trending composite syncline, with the Luxin coal mine located on the northern limb. The coal-bearing basin rests on a basement composed of Permian volcanic rocks, clastic sequences, and acidic intrusions, overlain by Jurassic strata. A major fault, trending approximately 338–158°, is developed within the area, extending along the contact between the Xishanyao Formation and the Albazai Formation and dipping southwest at ~64°, with a total length of ~10 km. This fault is a left-lateral strike-slip normal fault, with significantly fractured hanging and footwalls, the southern block downthrown, and the northern block upthrown. Intense fault activity has significantly influenced both the structure and preservation of coal seams. The SEH syncline serves as a regional coal-controlling structure, with an axis trending nearly east–west (~100–280°), a core composed of the Toutunhe Formation, a northern limb dip of 5–16°, a southern limb dip of 9–16°, and an overall gentle morphology.

3. Materials and Methods

A total of 15 coal samples were collected from the Luxin mining area in the central Turpan–Hami Basin. Samples were obtained from a ~10 cm × 10 cm area. Coals 2, 3, and 4, with thicknesses ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 m, were sampled using evenly spaced composite sampling at 0.25 m intervals. Seam 5, a thick coal seam (~20 m thick) within the study area, was sampled at four evenly spaced points with 3 m intervals (individually sampled). Corresponding roof and floor samples were collected for all coal seams to characterize the surrounding strata and boundary conditions; however, due to field constraints, only the roof sample of Seam 5 (SHE-5-1R) was obtained. All samples were placed in sealed bags and transported to the laboratory for storage and analysis. The sampling locations, seam thicknesses, and sample identifiers are shown in Figure 2 (prefixes R and F denote roof and floor samples, respectively). Prior to analysis, portions of the samples were ground to powders suitable for proximate and geochemical analyses, while others were prepared as polished coal blocks or cut into regular coal pieces for microscopic observation.

3.1. Standard Coal, Mineralogical, and Geochemical Analyses

Moisture, ash yield, volatile matter, total sulfur, and total chlorine contents were determined following ASTM standards D3173M-17A, D3174-12, D3175-17, D3177-02 and D4208-19, respectively [23,24,25,26,27]. Random vitrinite reflectance (Rr) was measured using a microphotometer (CRAIC 165 GeoImage, CRAIC Technologies, San Dimas, CA, USA) under oil immersion conditions, following the ASTM D2798-21 standards [28].

Initial samples were subjected to low-temperature ashing (LTA) using a low-temperature oxygen plasma asher (K1050X, EMITECH, Laughton, UK) at temperatures below 120 °C to minimize the influence of organic matter. Mineralogical analysis was performed on powdered samples using X-ray diffraction (XRD; Bruker D8 Advance, Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). Mineral phases were identified, and quantitative phase analysis was conducted by full-pattern Rietveld refinement. Additionally, mineral morphology was observed by a field emission scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (SEM-EDS, ZEISS Sigma 300, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

Major element concentrations (SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, MgO, CaO, MnO2, Na2O, K2O, and P2O5) were determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF, Thermo Scientific™ ARL™ QUANT’X EDXRF, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) after high-temperature ashing (HTA) at 815 °C. Trace elements were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Varian 820-MS, Mulgrave, Australia) following microwave-assisted acid digestion using a purified HNO3–HF mixture. The microwave digestion procedure and ICP-MS trace element analysis followed the detailed methods of Dai et al. [29].

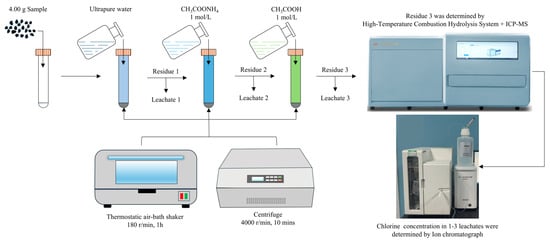

3.2. Analytical Methods for Chlorine Speciation

Chlorine occurrence in coal was determined using a combination of sequential chemical extraction procedure (SCEP) and high-temperature combustion hydrolysis (HTCP) (Figure 3). The SCEP was adapted from the methods of Finkelman, Zhao, and Yudovich [5,30,31], employing ultrapure water, ammonium acetate (1 mol/L), and acetic acid (1 mol/L) as sequential extracting solutions. Residues from the final SCEP step were further processed by HTCP: the sample was exposed to 1100 °C with steam to convert chlorine to HCl, which was absorbed in NaOH solution and subsequently analyzed. This combined approach allowed for the determination of the following chlorine species: (I) water-soluble Cl; (II) exchangeable or adsorbed Cl extracted by CH3COONH4; (III) carbonate-bound Cl; and (IV) Cl associated with organic matter and other mineral phases.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of the sequential chemical extraction procedure (SCEP) and high-temperature combustion-hydrolysis (HTCH) for chlorine speciation.

For each extraction, 4.0 g of dried powdered coal (accurate to 0.0001 g) was placed in a 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tube and mixed with 40 mL of ultrapure water. The mixture was agitated at 180 rpm for 1 h at room temperature using a thermostatic shaker (CHA-S, Jiangsu Jinyi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Jincheng Industrial Area, China). Following agitation, the samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min (LT53, Hunan Xiangyi Laboratory Instrument Development Co., Ltd., Changsha, China), and the supernatant was collected using a disposable syringe and filtered through a 0.45 μm PES membrane. The filtrate was diluted appropriately and analyzed for chlorine concentration by ion chromatography. The chlorine content in each sample was calculated as:

where C is the Cl concentration in the diluted solution (mg/L), V is the volume of extractant (mL), D is the dilution factor, and M is the sample mass (g); 10,000 converts mg/kg to %. The procedure was repeated sequentially for each SCEP extraction step.

HTCP was performed similarly: the residue after the third extraction step was mixed with high-purity SiO2 in a combustion crucible, placed in an automatic sample carousel, and subjected to combustion hydrolysis under 1100 °C oxygen flow. The evolved gases were absorbed in NaOH solution and analyzed following the same procedure and calculation method.

4. Results

4.1. Coal Properties

The proximate analysis, sulfur and chlorine contents, and random vitrinite reflectance (Rr) of SEH coals are listed in Table 1. The moisture contents of the coal samples show noticeable variations, which are mainly attributed to differences in coal texture, pore structure, and associated mineral matter, collectively affecting the water-retention capacity of the coals. The ash yields of Coal 2 and Coal 5 range from 4.4% to 9.52%, whereas those of Coal 3 and Coal 4 are 19.65% and 33.41%, respectively. According to GB/T 15224.1-2018 [32], Coals 2 and 5 are classified as very low-ash coals, while Coals 3 and 4 fall into medium-ash and medium-high-ash categories. The sulfur contents of Coals 2, 3, and 4 are 1.32%, 1.96%, and 0.9%, respectively, while Coal 5 exhibits 0.07–0.21%, with an average of 0.105%. Based on GB/T 15224.2-2021 [33], Coal 5 is classified as very low-sulfur, Coal 4 as low-sulfur, and Coals 2 and 3 as medium-sulfur.

Table 1.

Proximate analysis (%), total sulfur content (%), total chlorine content (%), and vitrinite random reflectance (%) of coal and associated noncoal samples from Coal Seams 2–5 in the Luxin Mine.

Chlorine content in all coals exceeds 0.3%, meeting the high-chlorine coal threshold defined by GB/T 20475.2-2006 [34]. Notably, sample SHE-5-3 shows an exceptionally high Cl content of 1.57%, which is unprecedented in the published literature. Random vitrinite reflectance ranges from 0.26 to 0.34, and volatile matter ranges from 37.11% to 59.52%, indicating these coals are high-volatile brown coals [35]. Overall, SEH coals show a wide range of ash and sulfur content, with a general trend toward low-ash and low-sulfur, while chlorine content is generally elevated and tends to increase with burial depth.

4.2. Mineralogy

The mineral assemblage of the SEH coal samples is dominated by quartz, clay minerals, and sulfate minerals (mainly bassanite), with subordinate feldspars and trace halide minerals. The mineralogical results of the samples are summarized in Table 2. In general, quartz, kaolinite, and bassanite constitute the principal mineral phases of the SEH coal samples, although their relative abundances vary among different seams. Quartz, kaolinite, and bassanite account for 11.7%–23.1%, 14.2%–45.9%, and 6.4%–49.0%, respectively. Illite and muscovite occur in relatively low abundances (illite: 0–17.5%; muscovite: 4.0%–15.6%), while montmorillonite appears only in minor amounts (4.7%–8.8%). In the lower coal seams (samples SEH-5-3 to SEH-5-6), bassanite is enriched, with contents reaching up to 49.0%, accompanied by minor halite and nitratine. It should be noted that part of this bassanite signal may originate from thermal decomposition of carbonates (e.g., calcite) during low-temperature ashing, and thus may not represent entirely primary sulfate minerals.

Table 2.

Mineral compositions (%) of the SEH coal (LTAs basis) and the associated non-coal samples (whole-rock basis).

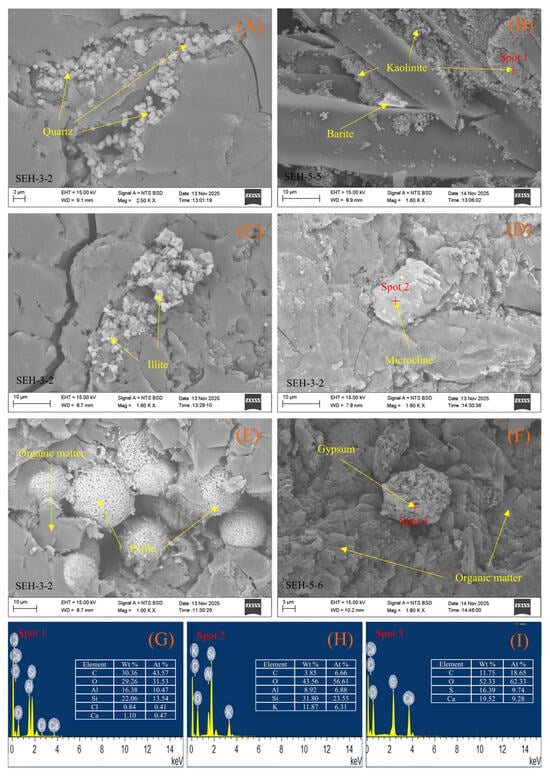

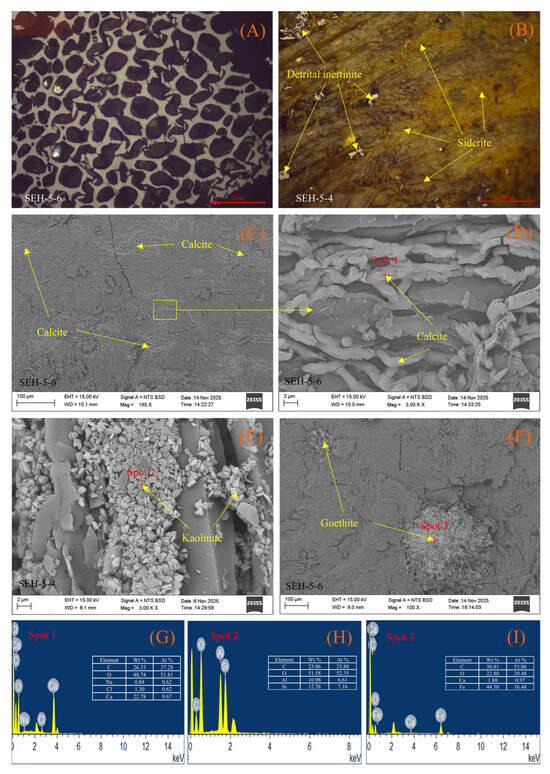

Optical microscopy and SEM-EDS observations indicate that SEH coals have high porosity with abundant detrital organic matter particles (Figure 4E,F). Kaolinite occurs both within plant cell walls (Figure 5A) and along microfractures in the coal matrix (Figure 4A and Figure 5E), forming lamellar or stacked aggregates, indicating later fluid migration. Calcite is distributed along matrix fractures in a vein-like pattern in some samples (Figure 5C,D), showing evidence of strong fluid transport or intrusion. Pyrite occurs mainly as framboidal or euhedral clusters (Figure 4E), characteristic of primary formation; while goethite and siderite are locally developed in minor fractures (Figure 5B,F), likely as oxidation products from water ingress. Gypsum appears as coarse blocks within the coal matrix (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Backscattered electron (BSE) images and selected-point EDS spectra of minerals in the coal samples. (A) Quartz filling microfractures; (B) kaolinite occurring as fracture infillings; (C) illite intergrown with organic matter; (D) plagioclase embedded within the coal matrix; (E) pyrite occurring as euhedral grains and framboidal forms within the coal matrix; (F) gypsum occurring among fragments of the coal matrix; (G), (H) and (I) EDS spectra of Spot 1, Spot 2, and Spot 3, respectively.

Figure 5.

Optical micrographs, backscattered electron (BSE) images, and selected-point EDS spectra of minerals in the coal samples. (A) Clay minerals extensively filling sieve-textured fusinite (plant cell cavities); (B) Disseminated siderite occurring within coal matrix fractures, with minor detrital inertinite present; (C) vein-like calcite; (D) calcite infilling pores within the coal matrix; (E) kaolinite filling fractures in the coal matrix; (F) goethite embedded within the coal matrix; (G), (H) and (I) EDS spectra of Spot 1, Spot 2, and Spot 3, respectively.

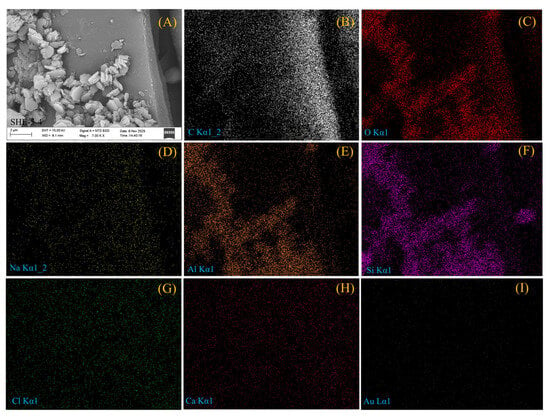

Notably, SEM-EDS analyses detected minor Cl signals on surfaces of various minerals (Figure 4G, Figure 5G and Figure 6G), but no NaCl crystals were observed in any coal sample. Elemental mapping indicates Cl is dispersed uniformly within mineral and matrix areas (Figure 6), suggesting soluble chlorine likely exists in amorphous, thin-film, or nanoscale forms rather than as typical crystalline salts.

Figure 6.

EDS area mapping spectra of a coexisting region of kaolinite and coal matrix. (A) Mapped area; (B), (C), (D), (E), (F), (G), and (H) represent the distribution of C, O, Na, Al, Si, Cl, and Ca elements within the scanned area, respectively; (I) Au element, from the gold coating during sample preparation.

4.3. Geochemistry

Major oxide compositions (whole-coal basis) of all samples are presented in Table 3. SiO2 dominates (0.59%–19.04%, average 3.79%), followed by CaO (1.49%–2.71%, average 2.27%) and Al2O3 (0.45%–8.30%, average 2.03%). Compared with average Chinese coals [36], CaO in SEH coals is relatively high, indicating carbonate input and precipitation during deposition or diagenesis, corroborated by SEM-EDS observations (Figure 5C,D). Elevated Na2O (0.67%, Chinese coals: ~0.16%) reflects influence from Na-rich brines during deposition or diagenesis, while the presence of MgO may indicate input from minor Mg-bearing minerals (e.g., dolomite or Mg-rich clays), although such minerals were not prominently identified in the mineralogical analyses of this study. Other major elements are close to or below Chinese coal averages.

Table 3.

Major element oxides in SEH coals. Loss on ignition (LOl; %) and contents of major element oxides (%).

Non-coal samples are dominated by SiO2 and Al2O3 (SiO2: 44%–58%; Al2O3: 19%–23%), indicating the significant presence of quartz and clay minerals. CaO, Na2O, and K2O contents are 0.5%–1.4%, 0.6%–1.3%, and 1.1%–2.2%, reflecting widespread minor alkali and calcium minerals. Fe2O3 ranges 2.7%–4.5%, suggesting minor Fe-bearing phases.

Forty-seven trace elements, including REEs, are listed in Table S1 [37]. According to Dai et al. [38,39,40], enrichment levels are classified as highly enriched (CC ≥ 10), enriched (5 ≤ CC < 10), slightly enriched (2 ≤ CC < 5), normal (0.5 ≤ CC < 2), and depleted (CC < 0.5). Weighted average-based CC calculations indicate most trace elements are at normal or depleted levels; only Sr (CC = 2.4) is slightly enriched, whereas Li, Ge, In, Sn, Ta, W, Th, U, etc., are strongly depleted (CC < 0.5), and Sc, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn are at normal levels. Overall, the trace element distribution does not show typical hydrothermal or marine influence, though slight Sr enrichment and other depletions may reflect carbonate participation or saline water influence in the depositional system.

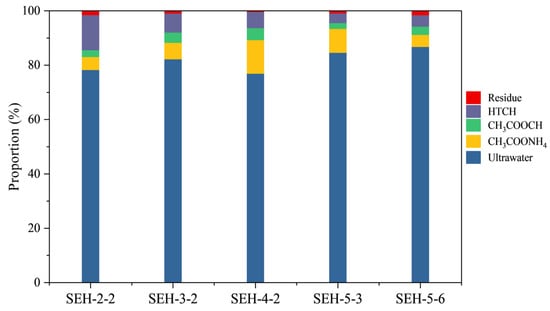

4.4. Chlorine Speciation

Based on the sequential chemical extraction procedure (SCEP) combined with high-temperature combustion hydrolysis (HTCP) described in Section 3.2, the concentrations of different chlorine species—including water-soluble, exchangeable/adsorbed, carbonate-bound, and organic/silicate-bound chlorine—were determined (Table 4). The distribution of chlorine species across the SEH coal samples shows a consistent pattern. After normalization (Figure 7), it is evident that the relative proportions of the four forms are markedly distinct, indicating a dominant single-species control over chlorine occurrence.

Table 4.

Chlorine concentrations in different occurrence forms of SEH coal obtained by SCEP and HTCH (%, Whole-Coal Basis).

Figure 7.

Normalized distribution of chlorine speciation in SEH coal samples showing proportions of water-soluble, adsorbed, carbonate-bound, and refractory chlorine.

In all samples, water-soluble chlorine is the predominant form, generally accounting for 80%–90% of total chlorine. Exchangeable/adsorbed chlorine represents the second major form, contributing roughly 5%–10%. Carbonate-bound chlorine is minor, typically 1%–3%, whereas organic/silicate-bound chlorine accounts for 4%–7%, appearing consistently but in smaller amounts. Residual chlorine remaining after HTCP is very low (<1%), suggesting that the majority of chlorine can be effectively mobilized and separated through chemical extraction, and that a negligible portion is structurally incorporated into mineral lattices or bound in stable forms.

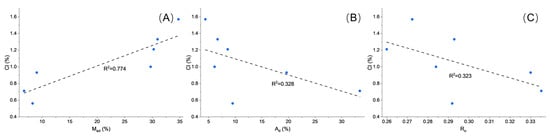

Correlation analysis between total chlorine content and coal properties (moisture, ash content, and random reflectance, Rr) reveals clear trends (Figure 8). Chlorine content shows a positive correlation with moisture and negative correlations with both ash content and Rr, indicating that chlorine preferentially associates with more labile, water-rich phases in coal. These water-rich phases mainly correspond to coal macerals with higher porosity and hydrophilic properties, such as vitrinite and associated microporous domains, which can retain inherent moisture. It is therefore likely that the elevated chlorine concentration reflects Cl− ions associated with this inherent moisture, potentially derived from Cl-rich formation waters present during peat accumulation and subsequent burial. Overall, the speciation pattern of chlorine in the SEH coals can be summarized as: water-soluble Cl ≫ exchangeable/adsorbed Cl > organic/silicate-bound Cl > carbonate-bound Cl, highlighting the dominant role of water-soluble chlorine in the coal matrix and the subordinate contributions of other forms.

Figure 8.

Correlation plots of chlorine content with (A) moisture, (B) ash yield, and (C) random vitrinite reflectance (Rr) in SEH coal samples.

5. Discussion

5.1. Depositional–Diagenetic Environment

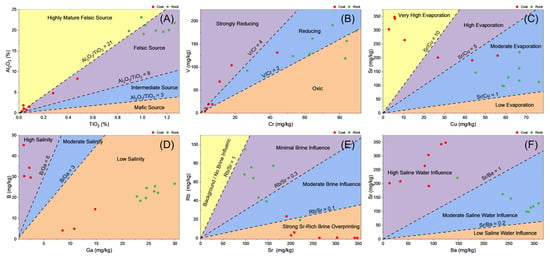

The mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of the SEH coal seams indicate that peat accumulated under strongly evaporative, semi-closed depositional conditions, providing an ideal environment for chlorine enrichment. The Al2O3/TiO2 ratios of the coal samples (Figure 9A) mostly exceed 8, with some samples even exceeding 21, reflecting that the detrital input was mainly mature felsic to intermediate-felsic material from the surrounding uplifts. This is consistent with the observation of abundant detrital quartz and kaolinite in SEM observations (Figure 4A,B) and XRD results (Table 2). The mudstone samples from the roof and floor show a narrow Al2O3/TiO2 ratio range (16–21), suggesting that the input pathways of detrital material remained relatively stable throughout the depositional process [41,42]. The redox conditions during peat formation are reflected in the V/Cr ratios (Figure 9B). The V/Cr ratios of coal samples are mostly greater than 2, with three samples exceeding 4, indicative of a reducing environment [43,44]. This corresponds with the frequent observation of framboidal pyrite (Figure 4E) and finely dispersed goethite (Figure 5F), pointing to an overall reducing state with low oxygen content but not completely stagnant, with significant local fluctuations, consistent with a water-saturated peat swamp in a semi-closed lacustrine–swamp environment.

Figure 9.

Geochemical indicators of the SEH coal seams. Colored intervals and in-figure labels indicate the corresponding depositional and post-depositional environmental characteristics. (A) Al2O3/TiO2 ratios of SEH coals and surrounding roof–floor mudstones, reflecting the provenance and maturity of detrital input; (B) V/Cr ratios of SEH coal samples, indicating redox conditions during peat accumulation; (C) Sr/Cu ratios of SEH coals and adjacent mudstones, used as an indicator of evaporation intensity and paleosalinity; (D) B/Ga ratios of SEH coals and surrounding rocks, reflecting the influence of saline or brackish water; (E) Rb/Sr ratios of SEH coals and roof–floor strata, indicating selective alteration by Sr-rich saline fluids; (F) Sr/Ba ratios of SEH coals and adjacent clastic rocks, reflecting saline water intrusion during diagenesis.

One of the strongest indicators of strong evaporative stress is the widespread presence of gypsum in the coal seams (Figure 4F; Table 2). Gypsum rarely precipitates in freshwater peat swamps but readily forms in sulfate-rich concentrated brines generated under high evaporation rates [45,46,47]. The observed definite gypsum indicates that pore water experienced strong ion concentration during peat accumulation, consistent with the environment of a shallow semi-closed basin where limited water exchange promoted salinity accumulation. Geochemical indicators sensitive to salinity further support this interpretation. Compared to the surrounding mudstones (0.5–1.7), the SEH coals have higher Sr/Cu ratios (3.1–9.6; Figure 9C), indicating strong evaporation [48,49,50]. The moderately enriched B/Ga ratios (usually >2) indicate the presence of saline or brackish water (Figure 9D), as boron is preferentially enriched in evaporative or alkaline fluids, while gallium is mainly present in detrital form [51]. These geochemical features, along with mineralogical evidence, indicate that the SEH coal seams were deposited in a high-evaporation, semi-closed lacustrine–swamp system, where restricted water exchange, strong evaporation, and local reducing environments worked together to provide favorable conditions for chlorine preservation in the peat.

5.2. Brine Iintrusion

The most direct mineralogical indicator is the presence of vein-like calcite, filling fractures and joints in the form of a three-dimensional interconnected network (Figure 5C,D), traceable for millimeters to centimeters. They cut through macerals and primary bedding–this geometry is inconsistent with syndepositional carbonate precipitation. Instead, such cross-cutting carbonate veins are typical products of late diagenetic brines [52,53,54], forming when Ca-HCO3− or Ca-Cl− rich fluids migrate along fracture systems and precipitate carbonate during fluid cooling or mixing. Another key mineralogical indicator is the widespread occurrence of kaolinite filling cell walls and micro-fractures (Figure 4B and Figure 5A,E). These authigenic kaolinite fillings are consistent with dissolution-precipitation reactions triggered by the interaction of acidic to weakly saline fluids with the coal matrix [55,56]. Their microcrystalline structure and pore-filling habit indicate active reaction between external fluids and the organic-mineral framework of the coal during diagenesis.

Typical geochemical indicators consistently indicate that the SEH coal seams experienced significant brine intrusion after deposition. The Rb/Sr ratio, as a sensitive tracer for provenance and fluid activity [57], provides key evidence for identifying brine alteration (Figure 9E). The Rb/Sr ratios of coal samples vary significantly, from 8.12 × 10−4 to 0.96, with most samples showing very low values (< 0.1) accompanied by significant Sr enrichment (up to 348 mg/kg, Table S1). This contrasts sharply with the relatively high and stable Rb/Sr ratios of the roof and floor rocks (e.g., SEH-2-1R, SEH-3-1R, etc.). The two are spatially closely associated yet show a strong geochemical contrast of “low Rb/Sr, high Sr in coal samples, normal in surrounding rocks”, effectively ruling out simple provenance control and clearly indicating selective overprinting of the coal seams by Sr-rich, Rb-poor saline fluids. The B/Ga ratio, as a sensitive paleosalinity indicator [58,59], ranges from 0.45 to 39.38 in SEH coals (mean 13.2), significantly higher than that of adjacent mudstones (0.78–1, mean 0.88; Figure 9D). Generally, boron is highly enriched in saline, alkaline, or evaporative waters, while gallium is mainly present in detrital form; therefore, higher B/Ga ratios indicate an enhanced influence of saline pore water [60]. Similarly, the Sr/Ba ratio in the coal seams is 0.34–5.99, significantly higher than that of the surrounding clastic rocks (0.2–0.6; Figure 9F). Since strontium is preferentially enriched in saline or brackish water, while barium is easily removed by barite precipitation in freshwater, higher Sr/Ba ratios indicate intermittent or persistent saline water intrusion during diagenesis [59,61].

In short, these three sets of mutually corroborating geochemical evidences–Rb/Sr, B/Ga, and Sr/Ba–together with mineralogical observations, reveal that the SEH coal seams experienced infiltration of saline water along fracture networks after deposition, accompanied by extensive fluid-rock interactions.

5.3. Chlorine Occurrence Forms

As mentioned in Section 4.4, water-soluble chlorine dominates the total chlorine content absolutely (78.3%–84.7%, average 79.7%), and is the primary occurrence form in SEH coals. However, the classification of “water-soluble chlorine” remains somewhat vague. Previous studies suggest that water-soluble chlorine can be divided into two main forms [5]: inorganic salt forms (e.g., NaCl) and inorganic ion forms (existing as ions or hydrated ions in pore water). In all coal samples of this study, no identifiable halite crystals were observed by SEM/EDS. This phenomenon can be explained from two aspects: first, halite may occur as nano- to sub-micron-scale salt films or aggregates coating maceral surfaces or filling micropores; however, elemental mapping at sub-micron to nanometer scales is extremely challenging under conventional SEM–EDS conditions, and such features may therefore escape detection. Second, chlorine may predominantly exist as inorganic ions or hydrated ions dissolved in capillary-bound pore water within the coal matrix, a mode of occurrence that is especially common in moisture-rich coal systems. Considering the extremely high proportion of water-soluble chlorine and the clear positive correlation between chlorine content and moisture (Figure 8A), the most reasonable interpretation is that chlorine in the SEH coal seams is mainly preserved as pore-water-bound Cl−, with nano-scale salt films being possible but not dominant contributors to the water-soluble chlorine pool. This occurrence characteristic is consistent with the chlorine occurrence mode reported for high-chlorine coals in the UK affected by high-salinity fluid invasion [9].

Although the proportion of adsorbed chlorine is significantly lower than water-soluble chlorine, it should not be overlooked, accounting for 4.7%–10.1% (average about 7.1%). As pointed out by Huggins et al. [11] in their study of high-chlorine coals in Illinois, USA, Cl can be bound to coal’s organic structure (e.g., quaternary amine groups, alkali metal carboxyl complexes) and adsorbed on micro-pore and fracture surfaces. The developed fine-grained kaolinite with high specific surface area in the SEH coal seams (Figure 4B and Figure 5E) provides key carriers for adsorbed Cl. Furthermore, the combined effect of evaporative concentration and external saline water input increases the ionic strength of the pore water, making Cl− more likely to form inner- or outer-sphere coordination adsorption on clay mineral surfaces [62,63], thereby increasing the proportion of adsorbed chlorine.

The total amount of mineral-bound and organically bound chlorine is usually less than 10%, belonging to minor components in SEH coals. Fabbri pointed out that both silicate and carbonate lattices have very low capacity for accommodating Cl [64]. The chlorine content also shows a negative correlation with ash yield (Figure 8B), so the low content of this part in SEH coals is reasonable. The SEH coal seams have low vitrinite reflectance (Table 1), and chlorine content shows a negative correlation with reflectance (Figure 8C), reflecting that the coal-forming process also lacked conditions that could promote organic halogenation reactions, making it difficult to form large amounts of organically bound chlorine. Although SEH coals are significantly affected by evaporative concentration and external brine intrusion, such brines mainly increase water-soluble chlorine content rather than driving organic halogenation reactions, thus making it difficult to form large amounts of organically bound chlorine. The results of SCEP and HTCH (Table 4; Figure 7) further confirm that this part is very low, indicating that the chlorine in SEH coals mainly originates from external evaporative brines, rather than organic chlorination during coal formation.

5.4. Formation Mechanism of High-Chlorine Coal

Integrating the geological setting, depositional–diagenetic environment, brine intrusion, and chlorine occurrence characteristics of the SEH coal seams, we can basically understand the genetic mechanism of the SHE high-chlorine coals. As mentioned earlier (see Section 5.1), the SEH coal seams formed in a semi-closed, high-evaporation lacustrine–swamp system. This depositional environment possesses two key characteristics: first, restricted water exchange allows external salts to be easily trapped within the system; second, continuous evaporation promotes the concentration of dissolved ions. This provides the most basic depositional condition for chlorine retention in the peat.

On this basis, the geological structure of this area (see Section 2) also created pathways for chlorine input. The NE-trending faults and secondary tensional-shear structures widely developed in the Luxin mining area and its vicinity provide effective routes for the migration of underground fluids. Chlorine-rich pore water/brine from outside the lake basin or deep strata could potentially enter the depositional center along fault zones. This “early brine intrusion” mechanism has been reported in several high-chlorine coal mining areas (e.g., Bowen Basin in Australia, Qianyingzi Mine in Anhui, China, Ibbenbüren anthracite mine in Germany), all indicating that tectonically driven external saline water input is an important initial condition for anomalous chlorine enrichment [65,66,67]. The widely distributed vein-like calcite and fine vein-like carbonate fillings in the SEH coal seams (Figure 5C,D) further support the existence of early fluid activity.

The strong evaporation conditions in this area further enhanced the chlorine concentration effect. During evaporation, water molecules are continuously lost, while Cl− gradually enriches within the system. This is highly consistent with the Sequential Chemical Extraction (SCEP) results: water-soluble chlorine accounts for 78.3%–84.7% of the total chlorine content, being the most prominent occurrence form in SEH coals. Although XRD detected relatively high contents of bassanite (30%–40%, LTA), this mainly reflects the precipitation of Ca2+–SO42− in the late diagenetic stage, which does not contradict the occurrence of Cl−; even in gypsum-rich coals, Cl− still exists mainly in dissolved and adsorbed forms, rather than forming stable minerals together with sulfate [68].

Overall, the high chlorine content in SEH coals is not directly caused by a typical marine transgression environment, but results from the coupling effect of salt retention within the semi-closed lake basin, tectonically controlled brine input, and strong evaporation conditions. Evaporative concentration is interpreted to have occurred during coal formation and early diagenesis as a persistent background process, while brine input represents a later, structurally controlled enrichment stage. In this process, Cl− accumulates in large quantities and is mainly preserved in water-soluble form, supplemented by a small amount of adsorbed chlorine, while mineral-bound and organically bound forms are significantly low.

6. Conclusions

The SEH coals formed in a strongly evaporative, semi-closed lacustrine–swamp environment and experienced later brine intrusion, leading to anomalous chlorine enrichment. The occurrence form of chlorine is dominated by the water-soluble state, which mainly exists as Cl− ions in pore water, rather than as typical halite crystals. Chlorine adsorbed on mineral surfaces (e.g., kaolinite) or in micropores of coal organic matter is a secondary occurrence form, while the contents of mineral-bound and organically bound chlorine are extremely low. The chlorine enrichment process is mainly controlled by three factors: First, the semi-closed sedimentary basin and strong evaporation provided a favorable primary environment for the initial concentration and preservation of chlorine. Second, regional fault systems provided channels for the migration of chlorine-rich brines from deep or peripheral sources into the coal seams, and the interaction between brines and coal seams (manifested as widespread vein-like calcite and authigenic kaolinite) further introduced a large amount of chlorine. Finally, continuous evaporation caused chloride ions to continuously concentrate in the coal seam pore water, ultimately being largely retained in the low-rank, high-moisture coal matrix in water-soluble form. This study emphasizes the key role of the “tectonics–brine–evaporation” coupled system in forming high-chlorine coals in terrestrial basins.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min16010018/s1, Table S1: Concentrations of trace elements (μg/g, In in ng/g, whole-coal basis) and the associated non-coal samples (whole-rock basis) from the Luxin Coalfield (SEH coal).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X. and W.W. (Wenfeng Wang); methodology, X.X. and W.W. (Wenlong Wang); validation, B.Z., Y.W. and J.L.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X., Y.W. and Q.L.; resources, W.W. (Wenfeng Wang); data curation, X.X., K.C. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X. and W.W. (Wenfeng Wang); visualization, X.X.; supervision, W.W. (Wenfeng Wang); project administration, W.W. (Wenfeng Wang); funding acquisition, W.W. (Wenfeng Wang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42472236, 42402176); the Graduate Innovation Program of China University of Mining and Technology (No. 2025WLKXJ008); the Major Science and Technology Special Project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (No. 2022A03014); the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Introduction Plan ‘Tianchi Talent’ project (No. 5105250180k); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2024QN11071); and the Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (No. 2024ZB489).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the staff at the Luxin Mining Area for their cooperation during the on-site sampling process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hong, K.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, H. Combustion Utilization of High-Chlorine Coal: Current Status and Future Prospects. Energies 2025, 18, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, D.A.; Duong, D.; Miller, B. Chlorine in solid fuels fired in pulverized fuel boilers Sources, forms, reactions, and consequences: A literature review. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 3379–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullett, B.; Sarofim, A.; Smith, K.; Procaccini, C. The role of chlorine in dioxin formation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2000, 78, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procaccini, C. The Chemistry of Chlorine in Combustion Systems and the Gas-Phase Formation of Chlorinated and Oxygenated Pollutants. Doctoral Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yudovich, Y.E.; Ketris, M. Chlorine in coal: A review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2006, 67, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.; Eskenazy, G.; Vassileva, C. Contents, modes of occurrence and origin of chlorine and bromine in coal. Fuel 2000, 79, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Song, G.; Yang, S.; Yang, Z.; Lyu, Q. Migration and transformation of sodium and chlorine in high-sodium high-chlorine Xinjiang lignite during circulating fluidized bed combustion. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Li, X. Release and transformation characteristics of modes of occurrence of chlorine in coal gangue during combustion. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 9926–9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, S.A.; Holmes, L.F.; Spears, D.A. Water-soluble chlorine and associated major cations from the coal and mudrocks of the Cannock and North Staffordshire coalfields. Fuel 1984, 63, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, S.A.; Holmes, L.F.; Spears, D.A. Total chlorine in coal seam profiles from the South Staffordshire (Cannock) coalfield. Fuel 1984, 63, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, F.E.; Huffman, G.P. Chlorine in coal: An XAFS spectroscopic investigation. Fuel 1995, 74, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Qiao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, E.; Ma, Y.; Hao, Y. Chemical characteristics, formation mechanisms, and geological evolution processes of high-salinity coal reservoir water in the Binchang area of the southern Ordos Basin, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 291, 104574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Jia, S.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Tan, H.; ur Rahman, Z. Experimental investigation of water washing effect on high-chlorine coal properties. Fuel 2022, 319, 123838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhuang, X.; Querol, X.; Font, O.; Moreno, N.; Zhou, J. Environmental geochemistry of the feed coals and their combustion by-products from two coal-fired power plants in Xinjiang Province, Northwest China. Fuel 2012, 95, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanor, J.S. Origin of saline fluids in sedimentary basins. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1994, 78, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, X.; Li, S.; Bundschuh, J. A review of the distribution, sources, genesis, and environmental concerns of salinity in groundwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 41157–41174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, A.J.; Weindorf, D.C. Heavy metal and trace metal analysis in soil by sequential extraction: A review of procedures. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2010, 2010, 387803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Tuzen, M.; Jatoi, W.B.; Feng, X.; Sun, G.; Saleh, T.A. A review of sequential extraction methods for fractionation analysis of toxic metals in solid environmental matrices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 173, 117639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, H.K.; Fatoki, O.S.; Adekola, F.A.; Ximba, B.J.; Snyman, R.G. A review of sequential extraction procedures for heavy metals speciation in soil and sediments. Open Access Sci. Rep. 2012, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selley, R.C. Ancient Sedimentary Environments: And Their Sub-Surface Diagnosis; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, C. Mineralogical and elemental geochemical characteristics of Taodonggou Group in Taibei Sag, Turpan-Hami Basin: Implication for Source sink system and evolution history of lake basin. EGUsphere 2023, 2023, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Zhao, C.; Tang, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Yuan, T. Sedimentary facies and coal-accumulation of the Early-Middle Jurassic in Toksun coalfield Northwestern China. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2013, 31, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3174-12; Standard Test Method for Ash in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke from Coal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ASTM D3173M-17a; Standard Test Method for Moisture in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D3175-17; Standard Test Method for Volatile Matter in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D4208-19; Standard Test Method for Total Chlorine in Coal by the Oxygen Vessel Combustion/Ion Selective Electrode Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ATSM D3177-02; Standard Test Methods for Total Sulfur in the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D2798-21; Standard Test Method for Microscopical Determination of the Vitrinite Reflectance of Coal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Dai, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hower, J.C.; Li, D.; Chen, W.; Zhu, X.; Zou, J. Chemical and mineralogical compositions of silicic, mafic, and alkali tonsteins in the late Permian coals from the Songzao Coalfield, Chongqing, Southwest China. Chem. Geol. 2011, 282, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelman, R.B.; Palmer, C.A.; Wang, P. Quantification of the modes of occurrence of 42 elements in coal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 185, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Ren, D.; Wang, Z. Geochemical characteristics and step-by-step extraction of chlorine in coal. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 1999, 28, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 15224.1-2018; Classification for Quality of Coal—Part 1: Ash. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 15224.2-2021; Classification for Quality of Coal—Part 2: Sulfur Content. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 20475.2-2006; Classification for Content of Harmful Elements in Coal—Part 2: Chlorine. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- ASTM D388-23; Standard Classification of Coals by Rank. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Dai, S.; Ren, D.; Chou, C.-L.; Finkelman, R.B.; Seredin, V.V.; Zhou, Y. Geochemistry of trace elements in Chinese coals: A review of abundances, genetic types, impacts on human health, and industrial utilization. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 94, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketris, M.P.; Yudovich, Y.E. Estimations of Clarkes for Carbonaceous Biolithes: World Averages for Trace Element Contents in Black Shales and Coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2009, 78, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Seredin, V.V.; Ward, C.R.; Hower, J.C.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, W.; Song, W.; Wang, P. Enrichment of U–Se–Mo–Re–V in coals preserved within marine carbonate successions: Geochemical and mineralogical data from the Late Permian Guiding Coalfield, Guizhou, China. Miner. Depos. 2015, 50, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Graham, I.T.; Ward, C.R. A review of anomalous rare earth elements and yttrium in coal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 159, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Liu, J.; Ward, C.R.; Hower, J.C.; French, D.; Jia, S.; Hood, M.M.; Garrison, T.M. Mineralogical and geochemical compositions of Late Permian coals and host rocks from the Guxu Coalfield, Sichuan Province, China, with emphasis on enrichment of rare metals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 166, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanga, A.D.; Ekoa Bessa, A.Z.; Ngueutchoua, G.; Armstrong-Altrin, J.S. Microtexture, mineralogy, and geochemistry of sediments in the Campo beach area, South Cameroon. J. Sediment. Environ. 2025, 10, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Dai, S.; Nechaev, V.; Sun, R. Environmental perturbations during the latest Permian: Evidence from organic carbon and mercury isotopes of a coal-bearing section in Yunnan Province, southwestern China. Chem. Geol. 2020, 549, 119680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, S.M. Geochemical paleoredox indicators in Devonian–Mississippian black shales, central Appalachian Basin (USA). Chem. Geol. 2004, 206, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandour, I.M. Paleoenvironmental changes across the Paleocene–Eocene boundary in West Central Sinai, Egypt: Geochemical proxies. Swiss J. Geosci. 2020, 113, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A.G.; Gavrieli, I.; Rosenberg, Y.O.; Reznik, I.J.; Luttge, A.; Emmanuel, S.; Ganor, J. Gypsum precipitation under saline conditions: Thermodynamics, kinetics, morphology, and size distribution. Minerals 2021, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J. Evaporites, brines and base metals: Fluids, flow and ‘the evaporite that was’. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 1997, 44, 149–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raup, O.B.; Bodine, M.W. Evaporites and Brines; The Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Ning, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Ding, L. Geochemical characteristics and paleoenvironmental significance of the Xishanyao Formation coal in the eastern Junggar Basin. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, W.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Dong, L. Geochemistry of Middle Jurassic Coals from the Dananhu Mine, Xinjiang: Emphasis on Sediment Source and Control Factors of Critical Metals. Minerals 2024, 14, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Li, C.; Leng, J.; Jia, M.; Gong, H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z. Paleoenvironmental characteristics of lacustrine shale and its impact on organic matter enrichment in Funing Formation of Subei Basin. Minerals 2023, 13, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Gilleaudeau, G.; Song, Y.; Ruebsam, W.; Algeo, T.J. Preface for Chemical Geology VSI: Elemental salinity proxies. Chem. Geol. 2025, 694, 123023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J. Evaporites, brines and base metals: Low-temperature ore emplacement controlled by evaporite diagenesis. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2000, 47, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargani-Guilani, K.; Faramarzi, M.; Tak, M.A.N. Multistage dolomitization in the cretaceous carbonates of the east Shahmirzad area, north Semnan, central Alborz, Iran. Carbonates Evaporites 2010, 25, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H. Halogen elements in sedimentary systems and their evolution during diagenesis. In The Role of Halogens in Terrestrial and Extraterrestrial Geochemical Processes: Surface, Crust, and Mantle; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 185–260. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Fan, A.; Van Loon, A.; Han, Z.; Wang, X. Depositional and diagenetic controls on sandstone reservoirs with low porosity and low permeability in the eastern Sulige gas field, China. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. Ed. 2014, 88, 1513–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Yao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, S.; Jia, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W. Influence of coupled dissolution-precipitation processes on the pore structure, characteristics, and evolution of tight sandstone: A case study in the upper Paleozoic reservoir of Bohai Bay Basin, eastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2024, 262, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataille, C.P.; Bowen, G.J. Mapping 87Sr/86Sr variations in bedrock and water for large scale provenance studies. Chem. Geol. 2012, 304, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewuła, K.; Środoń, J.; Kuligiewicz, A.; Mikołajczak, M.; Liivamägi, S. Critical evaluation of geochemical indices of palaeosalinity involving boron. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2022, 322, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, S.; Yue, D.; Cui, W. Paleosalinity reconstruction in offshore lacustrine basins based on elemental geochemistry: A case study of Middle-Upper Eocene Shahejie Formation, Zhanhua Sag, Bohai Bay Basin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 42, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Pang, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, T.; Lu, K.; Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X. Impact of paleosalinity, dilution, redox, and paleoproductivity on organic matter enrichment in a saline lacustrine rift basin: A case study of Paleogene organic-rich shale in Dongpu Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, Eastern China. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 5045–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, B. Evidence for cross formational hot brine flow from integrated 87Sr/86Sr, REE and fluid inclusions of the Ordovician veins in Central Tarim, China. Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, C.; Yang, G. Adsorption of ions at the interface of clay minerals and aqueous solutions. In Advances in Colloid Science; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, G.; Nkusi, G.; Schöler, H.F. Natural organohalogens in sediments. J. Für Prakt. Chem./Chem.-Ztg. 1996, 338, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizio, A.; Stalder, R.; Hametner, K.; Günther, D. Experimental chlorine partitioning between forsterite, enstatite and aqueous fluid at upper mantle conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 121, 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, S.; Collerson, K.; Uysal, I.; Glikson, M.; Baublys, K.; Zhao, J. Nature and source of carbonate mineralization in Bowen Basin coals, Eastern Australia. In Organic Matter and Mineralisation: Thermal Alteration, Hydrocarbon Generation and Role in Metallogenesis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 296–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, C.; Qimeng, L.; Yu, L.; Weihua, P.; Zitao, W.; Xiang, Z. Hydrochemical characteristics and source analysis of deep groundwater in Qianyingzi Coal Mine. Coal Geol. Explor. 2022, 50, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Rinder, T.; Dietzel, M.; Stammeier, J.A.; Leis, A.; Bedoya-González, D.; Hilberg, S. Geochemistry of coal mine drainage, groundwater, and brines from the Ibbenbüren mine, Germany: A coupled elemental-isotopic approach. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 121, 104693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, S.; Goldhaber, M.; Hatch, J. Modes of occurrence of mercury and other trace elements in coals from the warrior field, Black Warrior Basin, Northwestern Alabama. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2004, 59, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.