1. Introduction

Ultramafic alkaline ultrapotassic rocks provide key insights into deep mantle processes. Among these, kimberlites and lamproites are particularly significant due to their ability to sample metasomatized lithospheric and sub-lithospheric mantle domains. Despite their importance, their classification remains challenging, owing to their complex mineralogy, geochemical, and petrogenetic evidence.

Accurate classification of these rocks requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates mineralogical, geochemical, and petrogenetic criteria to build a robust and widely accepted framework and provide a basis for strong genetic interpretations with meaningful geological correlations. Recent advances in analytical techniques—such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), wavelength-dispersive spectroscopy (WDS), micro-XRF, and micro-Raman—have supported the development of refined mineralogical and genetic frameworks for distinguishing potassic-ultrapotassic alkaline rock types. These tools allow more precise identification of typomorphic minerals, degrees of hybridization, and distinction of mantle versus crustal contributions, which in turn allowed the development of mineralogical–genetic classification schemes for alkaline rocks, particularly kimberlites and lamproites.

The main objective of this paper is to clarify the classification of kimberlitic and lamproitic rocks occurring in the Sao Francisco Craton (SFC). Although many bodies in this region have historically been described as “kimberlites”, their mineralogical and geochemical signatures suggest a broader compositional spectrum. This has led to confusion and inconsistencies in the literature. To address these issues, we apply the modern classification schemes of Scoth-Smith et al. (2018) and Mitchell (2020) [

1,

2], which distinguish kimberlitic from lamproitic signatures based on integrated mineralogical–geochemical criteria. The IUGS still considers kimberlites and lamproites as part of the broader lamprophyric clan, and this terminology is retained here for consistency with international recommendations. Our goal is to establish clear distinctions between lamproitic and kimberlitic occurrences in the SFC and to refine their petrogenetic and geotectonic interpretations.

The complexity of these rocks has long been recognized. Rock [

3] provided one of the earliest systematic attempts to classify lamprophyres, characterizing them as mafic to ultramafic rocks rich in phlogopite, amphibole, and pyroxene. Although pioneering, this approach was initially overshadowed by alternative schemes. Since then, the study of these rocks has evolved significantly. Later refinements, such as those by Le Maitre [

4], separated kimberlites into Group 1, olivine-rich kimberlites, analogous to those from Kimberley, Wagner [

5], and Group 2 “orangeites”, formerly mica-rich kimberlites of the IUGS [

6]. However, this framework has been criticized for oversimplifying the diversity of kimberlitic rocks and failing to accommodate the full range of mineralogical and geochemical variations observed globally, including in the SFC [

7].

Subsequent studies emphasized typomorphic mineral assemblages and microanalytical characterization as tools for refining classifications. These approaches integrate petrography, mineral chemistry, texture, and spatial relationships, enabling more accurate interpretations of parental magma composition and mantle processes [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Scott-Smith et al. [

1] proposed that non-kimberlitic ultrapotassic bodies should be classified using type-locality suffixes (e.g., “Kaapvaal lamproite variety”). This acknowledges the effects of xenolith assimilation, hybridization, and lithospheric variability on magma composition. Despite this sophistication, deviations from classification criteria remain common, reflecting the inherently hybrid nature of these magmas [

11,

12].

Kimberlites are currently defined as volatile rich (H

2O and CO

2 contents often exceeding 5 and 10 wt.%, respectively), ultrabasic, potassic (Na

2O/K

2O ratios below 0.5, with Na

2O < ~0.5 wt.% and K

2O up to ~3 wt.%), and olivine rich (~50 modal %), typically exhibiting distinctive inequigranular textures with macrocrysts and microphenocrysts of olivine (and, less commonly, phlogopite and Mg-Cr-Ti spinel) [

7,

11]. Their fine-grained groundmasses may contain monticellite, phlogopite–kinoshitalite solid solutions, perovskite, apatite, carbonate (calcite and dolomite), spinel, and serpentine. However, “kimberlitic” bodies display significant diversity, complicating their classification.

Lamproites, historically regarded as less economically significant, have gained prominence following discoveries at Finsch (South Africa) and Argyle (Australia), which demonstrated their potential, particularly pyroclastic lamproites, to host both high- and low-grade diamonds, including rare pink diamonds [

9]. Notably, the Argyle AK1 mine contains some of the world’s highest-quality primary diamonds (~30–680 ct/100 t). These bodies not only have significant economic, but also high scientific interest, providing valuable insights into mantle processes [

9]. Moreover, recent syntheses of the geochemistry and mineralogy of kimberlites highlight that lamproites share several deep-mantle signatures with them, particularly in terms of radiogenic isotopes and volatile-rich mineral assemblages, reinforcing their genetic link to small-degree melts from metasomatized mantle sources [

9]. As discussed by Giuliani and Kamvisis [

10,

11], both display complex hybrid mineralogy, contributions from lithospheric and sub-lithospheric mantle components, and isotopic affinities to ocean island basalts, features that underscore their significance as probes of mantle evolution. These findings renewed global interest in lamproite occurrences and highlighted their scientific and economic value.

In the SFC, kimberlitic and lamproitic bodies display mineralogical and geochemical variability suggestive of multiple magmatic sources, mantle domains, and emplacement ages, patterns comparable to those documented in major global kimberlite provinces. The occurrence of rocks with lamproitic affinities in the Serrinha Nucleus portion of the craton has been known for nearly three decades [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. More recent work identifies hybrid kimberlitic-lamproitic compositions within the Nordestina Kimberlite Province (PKN), including the Braúna Kimberlite Field (BKF) [

18]. These classifications were initially based on Le Maitre [

19], but the acquisition of new data requires a reassessment utilizing modern frameworks in better to better understand the processes that have occurred in the SFC throughout geological time. Although previous studies provided important insights into Paleoproterozoic syenite-lamprophyre magmatism and potassic-alkaline processes [

16], there are significant gaps remaining in the distinction between kimberlitic and lamproitic components, their petrogenesis, and their relationship to diamond occurrences. By revisiting the works of Rios et al. [

15], Placid et al. [

16,

17], Nascimento et al. [

14], Santos et al. [

12,

18], and Donatti-Filho et al. [

19,

20] in association with the collection of new data, we propose an updated petrogenetic and geodynamic framework for the PKN and associated lamprophyric intrusions of the Morro do Afonso Syenite Pluton.

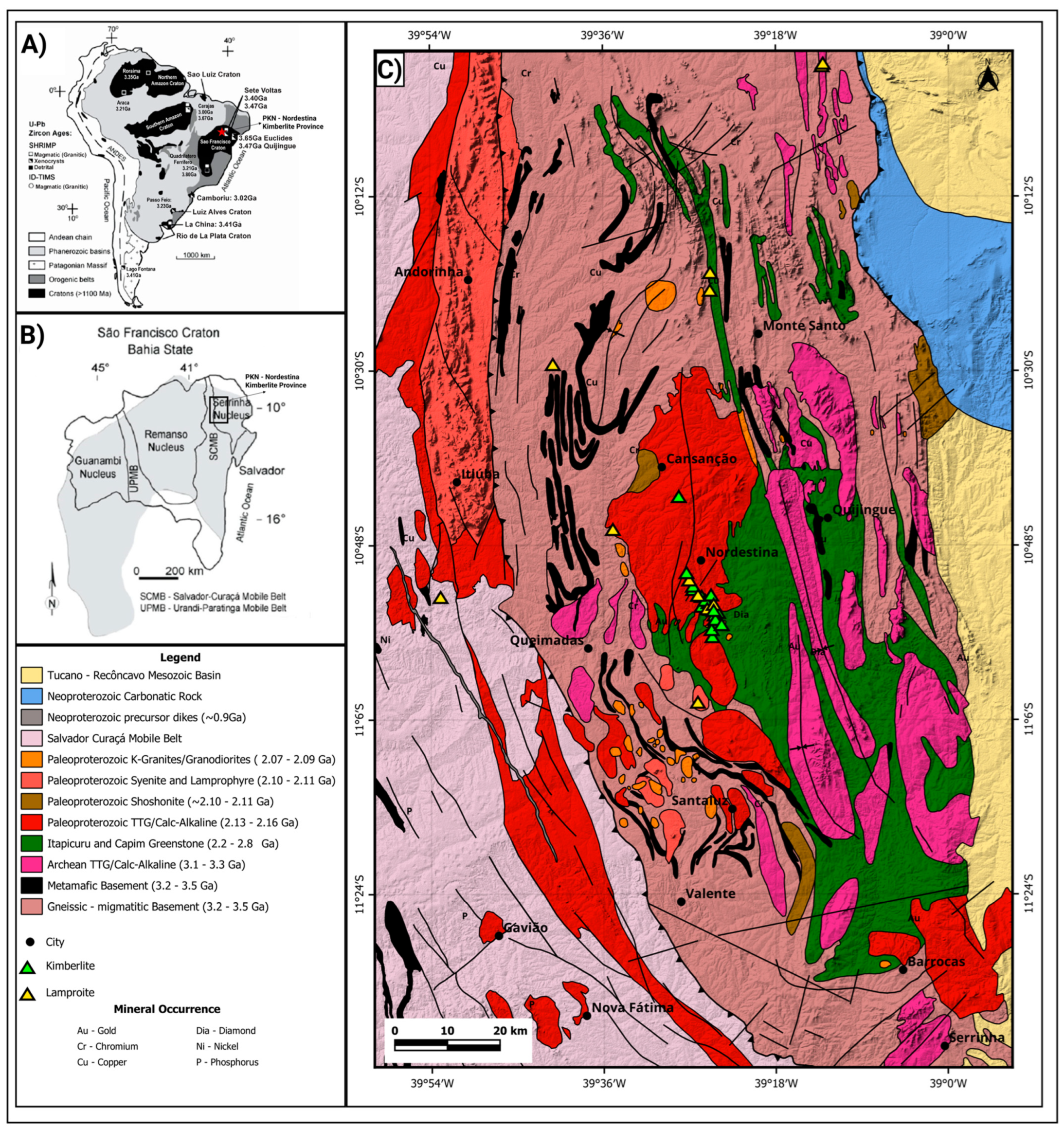

2. Geological Background

Diamond exploration in Bahia has deep historical roots, beginning in the 16th century, when pioneer Bandeirante expeditions ventured into the country’s rural areas and laid the foundations of Brazil’s mining industry, which remains a pillar of the regional economy. However, the primary sources of these gemstones remained undiscovered until the late 20th century. It was in the 1980s that De Beers initiated systematic exploration [

5], identifying numerous kimberlitic (s.l.) bodies within the Serrinha Nucleus (SerN) of the São Francisco Craton (SFC), one of the most exposed and extensively studied tectonic provinces of South America [

5]. At least 20 kimberlite bodies have been reported in the SerN, yet their classification remains uncertain due to complex mineralogical and chemical attributes, which traditional methods often fail to resolve.

The western boundary of the SerN is defined by the Salvador-Curaçá Mobile Belt (SCMB), a major Paleoproterozoic tectonic structure. The Aroeira lamproite, so far the only known off-craton kimberlitic body in this region, occurs along its boundary. The SCMB consists mainly of tonalite–trondhjemite–granodiorite (TTG) orthogneisses of the Caraíba Complex. Other key geological units include (i) those of the Itiúba Syenite (2.1 Ga, U-Pb), a 1800 km

2 ultrapotassic syenite–lamprophyre suite [

21]; (ii) The Nordestina Trondhjemite Batholith (NTB, 2155 ± 9 Ma, Pb-Pb), a representative example of Paleoproterozoic calc-alkaline juvenile magmatism [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]; and (iii) the Santaluz Complex, comprising Archean gneisses and migmatites intruded by diverse granites and greenstone sequences [

16].

The SerN also preserves evidence of late-to-post-orogenic alkaline and potassic-ultrapotassic magmatism (2.11–2.07 Ga), including shoshonites, syenites, and lamprophyres with lamproitic affinity [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. These small circular and oval intrusions retain magmatic textures and flux foliations, reflecting their emplacement during the final stages of regional tectonism.

South of the NTB lies the Morro do Afonso Syenitic Pluton (2.11 Ga, MASP), spatially aligned with the Braúna kimberlite intrusions. It comprises a bimodal suite of syenites and mafic dykes of lamprophyric/lamproitic affinity [

14,

15]. Their genesis is linked to partial melting of a subduction-modified mantle, with zircon inheritance up to 2.6 Ga [

15]. The subsequent interaction with SerN Archean TTGs during magma ascent may have further influenced their chemical and mineralogical characteristics.

The PKN (

Figure 1) hosts more than 20 kimberlites (s.l.) intrusions, including (i) the Braúna Kimberlite Field (BKF), aged at ~0.7 Ga [

21], with three major pipes and numerous dikes [

20,

21]; and (ii) additional dikes such as Alecrim, Angico, Umbu, Asa Branca 1–2, Icó 1–2, and Aroeira [

14,

20]. Among them, the Braúna 3 pipe is noteworthy as the only operational kimberlite diamond mine in Latin America [

14].

Despite yielding diamonds and microdiamonds in surface samples [

23], the PKN remains poorly characterized petrologically, and lamproite occurrences were only recently recognized. Preliminary mineralogical observations, including Mn–ilmenite, orickite in Braúna 7, and Ba-enriched phases, suggest derivation from a deep mantle source [

14,

21].

3. Methodology

The methodological strategy adopted integrates petrography, lithochemistry, and mineral chemistry to systematically characterize the bodies of the PKN. The protocol was designed to address two main challenges: (i) the identification of complex mineral assemblages, including exotic or altered phases in partially weathered samples; and (ii) the quantification of mineralogical and geochemical variations to reconstruct magmatic processes and post-emplacement alteration. This integrated approach ensures a robust framework for distinguishing between kimberlitic and lamproitic affinities while shedding light on their petrogenesis.

3.1. Sampling

A total of 39 samples were analyzed from 23 kimberlitic bodies and 16 lamproitic bodies of the PKN, in addition to 5 lamprophyric dikes from the Gameleira and Morro do Afonso massifs (MASP,

Table 1 and

Table 2). Most samples (FV) provided by the Brazilian Geological Survey (SGB) were collected during the Diamond Brazil Project (2003–2013) [

26] and are approximately fist-sized. These include 6 drill-core samples (22–106 m depth), 6 surface outcrop samples, and 27 trench samples (0.2 to 12 m depth). Geologar Research Group Samples (NS) collected between 1995 and 2020 represent fresh rocks from surface outcrops (<0.5 m depth) and trenches (0.5 to 2 m). This differentiation by source and depth allows direct comparison of fresh vs. weathered samples, according to weathering indices (e.g., Clement contamination index (SiO

2 + Al

2O

3/2K

2O + MgO) [

27] and Taylor alteration index (FeO

t + TiO

2/2K

2O + MgO) [

28]) alongside mineralogical and geochemical data.

3.2. Sample Preparation

Each sample was split into two fractions: (i) powder preparation for whole-rock geochemistry and XRD analyses, and (ii) thin-section preparation, resulting in three orthogonal polished thin sections (TSs) produced from each sample. Complimentary polished slabs (5 cm × 3 cm × 0.5 cm) were also prepared to facilitate macroscopic descriptions.

Thin sections were prepared at the SGB-SUREG Salvador. TS were cut based on the main foliation and mineral alignment (

Figure 2A). Cut-1 was made parallel to foliation, orthogonal to the drill core. Cuts 2 and 3 were longitudinal to the core, perpendicular to each other, providing a 3D mineralogical context. Half of each drill core was reserved for macroscopic descriptions, while the other half was prepared for analyses.

3.3. Optical and Digital Petrography

Initial petrographic observations were made using an Olympus BX51 microscope at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, Brazil. These were followed by high-resolution digital imaging using (i) an automated Olympus DSX-500 system (Western University, EPMA Lab, London, ON, Canada), (ii) VHX-X1 Keyence Digital microscopes (Camborne School of Mines, Exeter University, Cornwall, UK; and University of Toronto, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Images were captured at ~385 nm/pixel and stitched using Adobe Creative Suite, generating billion-pixel PPL and XPL mosaics. These allow browser-based interactive petrography, enabling collaborative examination of textures, mineralogical variations, and alteration patterns beyond conventional microscopy.

This method facilitated the recognition of both primary and secondary phases, clarifying mineral interactions during ascent and emplacement. Mineral abbreviations follow Warr [

29].

3.4. Lithochemical Analyses

Lithochemical analyses were carried out at Geosol Laboratories (SGS Brazil). Fragments weighing 50–100 g were reduced to 3 mm (75% passing) and ground to <150#(mesh) (95% passing). Duplicate fragments were distinguished with suffixes _1 and _2. Subsampling was performed using a Jones splitter.

Major elements were analyzed by ICP-OES and by XRF using pellets prepared via lithium tetraborate fusion. Total iron (reported as Fe

2O

3) was obtained from XRF analyses. Ferrous iron (Fe

2+), expressed as FeO, was determined by titration; in this context, the FeO value represents only the divalent iron fraction, while ferric iron (Fe

3+) can be calculated by difference when required. Carbon phases were identified by infrared spectroscopy. Loss on ignition (LOI) was measured gravimetrically at 1000 °C. Minor and trace elements were analyzed by ICP-MS following lithium metaborate (LiBO

2) fusion and acid dissolution. The results are provided in the

Supplementary File.

3.5. X-ray Diffraction and Rietveld Refinement

To complement petrography and geochemistry, one-quarter of each powdered sample (15–20 g) was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD). Phase identification was carried out using HighScore Plus (v.4.9) [

30].

Quantitative analysis was conducted through Rietveld refinement using the General Structure Analysis System (GSAS) [

31]. Parameters such as cell dimensions, atomic positions, and thermal factors were refined to produce accurate mineral quantification.

This approach allowed for the precise determination of both crystalline and fine-grained alteration phases, enhancing the interpretation of magmatic evolution and post-magmatic processes.

4. Results

Integrated petrographic, mineralogical, and geochemical analyses reveal two distinct diamond-bearing magma types in the Nordestina Kimberlitic Province: Type 1 magmas, represented by the Braúna 03 pipe, preserve features of a less evolved, olivine-dominated kimberlitic-lamproitic melts that crystallized in equilibrium with mantle assemblages. Type 2 magmas, typified by the Aroeira dike, display the mineralogical and textural attributes of phlogopite-dominated lamproitic systems.

Both magma types contain abundant mantle and crustal xenoliths. These occur as fragments ranging from sub-millimetric to decametric-sized nodules. Even in the absence of macroxenoliths (>0.5 cm), microxenoliths are consistently preserved, observable in thin sections.

4.1. Type 1 Magma—Olivine-Rich Braúna Kimberlites

The Braúna intrusions (e.g., Braúna 3, 5, 7, 8, 16, and 21) are hypabyssal, macrocrystic olivine/serpentine–phlogopite kimberlites emplaced in shallow, volatile-rich crustal environments, where hydrothermal fluids and high-temperature volcanic activity significantly influenced their post-magmatic evolution (

Figure 3;

Table 1)

These kimberlites display inequigranular, seriate textures, with a dominant macrocrystic to megacrystic mineral assemblage, dominated by forsterite olivine with variable serpentinization, which is accompanied by phlogopite, pyroxenes, and rare garnet. This assemblage is set in a fine-grained lamproitic groundmass (

Figure 3).

Olivine forms abundant macro- to megacrysts (0.5 to 5.8 mm). Many grains are angular or fragmental, typically subhedral to euhedral, consistent with derivation from disaggregated mantle xenoliths. Despite extensive serpentinization, pseudomorphic textures preserve the original morphology. Some olivine grains contain inclusions of chromite and apatite, further supporting their mantle-derived origin.

Phlogopite occurs as both macrocrysts (0.5 to 2.4 mm) and fine-grained plates in the matrix. Macrocrysts are subhedral to euhedral and frequently show hematite exsolution, inclusions of silicates—olivine, serpentine-pseudomorphed olivine, diopside—acicular apatite, and localized alteration to vermiculite/chlorite, particularly along cleavage planes or grain boundaries. Groundmass phlogopite forms dense mesh, micro-scale lamellae that maintain their lamellar structure even under advanced alteration.

Clinopyroxene, typically prismatic or acicular (0.5 to 2.2 mm), occurs as macrocrysts and as anhedral interstitial grains in the groundmass. The macrocrysts are usually subhedral to euhedral, and some contain inclusions of olivine or apatite. In the matrix, they form a fine-grained interlocking network with serpentine and phlogopite.

Rare occurrences of garnet macrocrysts, chromite, ilmenite, perovskite, and minor sulfides are observed, typically as accessory phases or as inclusions within larger crystals.

The groundmass is aphanitic to very fine-grained, dominated by serpentine and phlogopite, with accessory minerals including euhedral perovskite (with square cross-sections), chromite, ilmenite, sulfides, and scattered carbonate blebs (<0.05 mm).

Magmaclasts and autholits are common, recording internal fragmentation and remobilization of partially crystallized melt. These features vary from rounded to angular in shape and exhibit curvilinear to embayed margins, often immersed in the finer-grained groundmass, which crystallized from the residual melt.

Mantle-derived xenoliths and xenocrysts are minor but significant components providing key petrogenetic information. Garnet xenocrysts include eclogite (orange), peridotite (pink, red, burgundy), and rare harzburgite (purplish) types. Additional mantle-derived phases include chrome diopside (only as inclusions), spinel, and large phlogopite megacrysts. A mica-bearing peridotite xenolith was identified, containing diopside, subordinate olivine, and accessory apatite and zircon, indicative of a spinel-facies mantle source.

In summary, Braúna kimberlites are texturally complex hypabyssal intrusions, with high macrocryst contents, abundant mantle signatures, and strong post-magmatic alteration. Their features reflect crystallization and emplacement in a shallow, volatile-rich environment. The interaction between distinct magma pulses, combined with post-emplacement hydrothermal alteration, has left a rich record of mantle processes and reveals a prolonged magmatic history shaped by multiple pulses, crustal assimilation, and hydrothermal processes.

4.2. Type 2 Magma—Phlogopite-Rich Lamproites, the SFC Lamproite Variety

Type 2 lamproites, including Aroeira, Umbu 1–2, Ico 1–2, Asa Branca 1, and Braúna 1, 9, 12, 17, 18, and 19 (

Figure 4), exhibit a contrasting mineralogical framework dominated by phlogopite and characterized by distinctive megacryst populations set within a fine-grained, phlogopite-rich matrix, densely packed with small pyroxene prisms, opaque minerals, and fine phlogopite lamellae.

Olivine occurs exclusively as macro- to megacrysts (4 mm to 30 mm). Crystals are prismatic, subhedral to anhedral, and range from moss-green to light brown. Curved and re-entrant boundaries are common, and the grains usually display second to third-order interference colors, often yellow. Euhedral chromite and ripple- or eye-shaped phosphate inclusions are widespread. Resorption textures, producing characteristics “dog’s tooth” margins typical of “orangeite” rocks, indicate magmatic instability before serpentinization. Serpentine surrounds or infiltrates the olivine margins, often in association with the surrounding pyroxene-rich groundmass.

Phlogopite is the dominant mineral phase. Macrocrysts (2–12 mm, rarely megacrysts up to 40 mm) are subhedral, lamellar, and light brown, displaying bird’s-eye extinction and abundant exsolution textures. Groundmass phlogopite consists of fine-grained lamellae intergrown with pyroxenes and opaques. Phlogopite macro- and megacrysts commonly form embayed boundaries and act as nucleation sites for olivine, and are frequently bordered by serpentine or pyroxene. Exsolution textures indicate a prolonged cooling history, highlighting dynamic crystallization and late-stage mingling between crystal populations and the melt. Radiating aggregates of phlogopite, often including pyroxene and serpentine, further illustrate the intricate interactions between mineral phases during magmatic differentiation. Pyroxenes are found predominantly in the groundmass as fine-grained microcrystals with a mesh or needle-like habit (<0.2 mm). They display brown to green hues (mossy or pale) and show limited petrographic distinction due to small grain size and weathering, with interference colors from first-order yellow to light brown. Curved and re-entrant boundaries, interlocking networks, and poikilitic needle inclusions within olivine macrocrysts indicate syn- to late-magmatic growth. Due to their fine-grained size and advanced weathering, specific pyroxene types could not be identified petrographically.

Opaque minerals are present both as inclusions within megacrysts and dispersed in the groundmass. Subhedral, elongated microcrystals interpreted as ilmenite (0.09–0.1 mm) form poikilitic textures, while euhedral cubic chromite crystals appear as inclusions and isolated grains dispersed in the matrix.

Phosphates (0.01–2.0 mm), likely apatite, occur as inclusions and recrystallized groundmass phases. Their presence in Aroeira-type lamproites, previously undocumented, provides new constraints on lamproite evolution in the PKN.

Barite, carbonates, phosphates, and silica minerals fill fractures and micro-veins, crosscutting both macrocrysts and matrix. These metasomatic features reflect post-crystallization fluid activity.

In rare cases, fractured, colorless grains showing undulatory extinction, likely quartz or a silica polymorph, occur bordered by two adjacent phlogopite megacrysts, further indicating late-stage fluid interaction.

Aroeira and related SFC lamproites exhibit a complex assemblage dominated by phlogopite and characterized by megacrystic olivine, abundant opaque minerals, fine pyroxenes, and metasomatic veins. Their textures documented prolonged crystallization, resorption, and fluid-driven alteration, underscoring the distinct magmatic processes that separate this type 2 phlogopite lamproites from type 1 olivine-kimberlites in the SFC.

5. Discussion

The petrographic diversity observed in the kimberlites and lamproites illustrates the heterogeneity of the PKN’s ultrapotassic magmatism and underscores the need for integrated mineralogical–geochemical workflows to further elucidate the magmatic history and tectonic context of the SFC.

Within this study, macroscopic classifications proved insufficient given the presence of numerous small-scale magmatic fragments and the effects of mixing, hybridization, and alteration. Thin sections improve resolution but remain limited by orientation effects relative to magma flow. The classification of kimberlitic rocks by visual inspection alone presented significant limitations and is particularly challenging for samples from the PKN, where multiple magma pulses are present, frequently showing very distinctive compositions and preserved microscopic fragments in the late magmas. Also, most of these features are impossible to observe macroscopically.

Figure 2 showcases some of these challenges, presenting visual examples from the PKN that highlight these issues.

Our approach also establishes a robust comparative dataset for global kimberlite and lamproite studies. By refining analytical procedures for weathered and compositionally complex samples, this study offers a methodological model applicable to other exotic igneous bodies worldwide, particularly in countries where advanced microanalytical techniques—such as EPMA and SIMS—are less accessible.

5.1. Lithochemical Insights

Whole-rock analyses reveal a wide compositional range across the studied bodies, reflecting the combined influence of deep mantle processes, magma–crust interaction, and extensive effects of hydrothermal fluids post-magmatic alteration.

The major element variation highlights both the primary characteristics of lamproitic and kimberlitic magmas and the effects of secondary processes such as silicification, carbonation, and serpentinization. SiO

2 content ranges from 23.9% to 80.1%, indicating a transition from ultrabasic compositions (typical of primary lamproites) to highly altered silica-rich samples. Very low silica values (e.g., Braúna 13: 23.9% and Braúna 21: 36.9%,

Figure 5) are consistent with primitive mantle-derived melts. In contrast, the extremely high SiO

2 contents recorded in some samples (e.g., Braúna 5: 75.9% and Aroeira: 80.08%) indicate strong silicification or assimilation of quartz-rich crustal material. Values approaching ~60% or higher are interpreted as evidence of incorporated acidid crustal xenoliths that were not recognized during sampling for analyses.

MgO, a marker of mantle affinity, ranges from 0.77% to 30.6%. Elevated MgO, such as in Braúna 3 (30.6% MgO) and Braúna 21 (25.1%), preserves a mantle peridotite signature, whereas low MgO (e.g., Braúna 5: 2.22% MgO) reflects either loss of mafic phases during hydrothermal alteration or magmatic differentiation. Together, these variations define a geochemical spectrum from primitive mantle melts to strongly altered and contaminated compositions.

5.1.1. Type 1 Magma—Olivine-Rich Braúna Kimberlites

The olivine-rich Braúna kimberlites show significant compositional variability, reflecting both primitive mantle signatures and variable degrees of crustal assimilation during ascent through the SFC. The main bodies investigated (Braúna 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 13, 16, 17, and 21, and Umbu 1) illustrate this hybrid character.

Braúna 3 highlights the interplay between primitive and contaminated signatures and the hybrid nature of these kimberlites. SiO

2 ranges from 36 to 50 wt.%, with MgO between 4 and 15 wt.% (

Figure 5). Highly compatible element concentrations (Ni up to 1069 ppm and Cr 80–125 ppm) confirm a mantle source, whereas enrichment in lithophile elements such as Rb (≤118 ppm), Ba (≤1976 ppm), and Sr (81–678 ppm) marks crustal involvement. LOI values of 5%–14% reflect volatile-rich phases, consistent with carbonates and serpentine, and the role of secondary alteration. This internal variability underscores the dynamic nature of kimberlite magmatism, preserving deep mantle signatures while recording crustal interaction.

Other bodies reinforce this duality. Braúna 13 represents the most primitive end of the spectrum. Low SiO2 (21.7 wt.%), high MgO (30.8 wt.%), and elevated Ni (523 ppm) and Cr (86.2 ppm) indicate derivation from an ultramafic mantle source. The high LOI (27.8%) reflects pervasive carbonation and serpentinization.

In contrast, some Braúna 3 samples show anomalously high silica contents (>70 wt.%), low MgO and Ni, and enrichment in Ba (≤412 ppm) and Sr (54 ppm) (

Figure 6). These features are inconsistent with primitive kimberlites and instead point to dominant crustal assimilation with minimal post-magmatic alteration (low LOI ~3%).

Intermediate compositions occur in several bodies. For example, Braúna 1 displays SiO

2 (≈50 wt.%), MgO (2–3 wt.%), Ni (>1100 ppm), and Cr (≈125 ppm), partially preserving mantle characteristics despite crustal input. Again, the LOI of 10% indicates significant volatile content. Braúna 21 (SiO

2 36.9 wt.%; MgO 7.4 wt.%), and Braúna 19 (SiO

2 ≈ 49 wt.%; MgO 3 wt.%; Ni > 1100 ppm; and LOI = 10%–11%) both show enrichment in incompatible elements (Rb ≤ 215 ppm; Ba up to 2885 ppm; Sr 65 ppm;

Figure 6), indicating assimilation of crustal components on a mantle--derived chemistry.

Overall, type 1 kimberlites with low SiO2 and high MgO, Ni, and Cr (e.g., Braúna 13, Braúna 4) best preserve primitive mantle signatures, whereas those with higher silica and lithophile enrichment (e.g., Braúna 3 and Braúna 1) reflect substantial crustal modification. LOI variability (~2% to >27%) emphasizes the importance of serpentinization and carbonation in modifying primary compositions.

5.1.2. Type 2 Magma—Craton of San Francisco—Phlogopite-Rich Lamproite Variety

The Type 2 lamproites of the SFC (e.g., Braúna 8, 12, 18, and 19; Aroeira; and Asa Branca 1 and 2) are characterized by pronounced geochemical diversity derived from metasomatized mantle sources combined with varying degrees of crustal assimilation and secondary alteration. These lamproites record the ascent of volatile-rich, potassium- and incompatible-element-enriched magmas through the São Francisco Craton.

Aroeira provides a clear example of the primary lamproite signature at the SFC. Its moderate to low SiO

2 (51.7–58.1 wt.%) and elevated MgO (13.6–18.9 wt.%) (

Figure 5), along with high Ni (up to 276 ppm) and Cr

2O

3 (up to 2.67 wt.%), reflect derivation from a phlogopite- and amphibole-bearing metasomatized lithospheric mantle. LOI values of 7%–13% are consistent with hydrous and carbonated phases, such as phlogopite, apatite, and carbonate, typical of lamproitic systems.

However, other samples from the same intrusion (e.g., Aroeira NS 3385 B2, NS 3385 B3) and from Braúna 8 record high SiO

2 contents (78–80 wt.%) and low MgO (<8 wt.%), with depleted Ni and Cr. These values reflect substantial crustal assimilation or differentiation. Their enrichment in incompatible elements (Rb up to 306 ppm; Ba up to 1.97 wt.%; Th up to 33.7 ppm; and elevated U; see

Figure 6) is typical of lamproitic enriched mantle domains interacting with felsic crust. The exceptionally high SiO

2 in these samples is best explained by the incorporation of quartz-rich xenolithic material.

Intermediate compositions are preserved in Braúna 8, Braúna 12, and Umbu 1 (SiO

2 52–67 wt.%; MgO 6–10 wt.%; and Ni 100 to 275 ppm). These samples retain aspects of the enriched mantle signature, while also recording crustal assimilation. Umbu 1 stands out for its high LREE contents (e.g., Ce 438 ppm and Nd 189 ppm; see

Figure 7) and LOI of 8.9%, indicating both a volatile-rich, metasomatized source and post-magmatic alteration.

In summary, the SFC lamproites record the ascent of volatile-rich, ultrapotassic melts derived from a strongly metasomatized lithospheric mantle. Their geochemical variability, particularly in SiO2, MgO, Ni, Cr, LOI, and trace elements, captures the interplay among source heterogeneity, crustal contamination, and secondary alteration. These signatures provide critical insights into the mantle evolution and tectonomagmatic history of the São Francisco Craton.

5.2. Petrogenetic Insights

Mineralogical and textural contrasts between the Kimberlite Braúna and SFC Lamproite variety reflect differences in magma evolution, supported directly by the analytical dataset obtained in this study. Kimberlite Braúna samples contain abundant olivine and pyroxene, preserved mantle xenocrysts (forsteritic olivine and Cr-diopside), and relatively coarse seriate textures, all consistent with less evolved, deeper-seated melts [

1,

34]. In contrast, the SFC lamproite variety exhibits finer groundmasses, abundant phlogopite macrocrysts, and pervasive barite–carbonate–silica microveins, features consistent with shallow emplacement, rapid cooling, and late-stage volatile-fluid overprinting [

34,

35,

36,

37].

Alteration patterns further magnify these differences. Braúna kimberlites show moderate serpentinization and carbonation (LOI 5%–15%), whereas the SFC lamproite variety is heavily modified by serpentinization, vermiculitization, and hydrothermal veining, producing very high LOI values (up to 27.5%) [

37,

38]. Elevated P

2O

5 (up to 1.1%) and anomalously high SiO

2 values (e.g., 80.1% in FV-R-507C) reflect interaction with silica-rich fluids and assimilation of crustal xenoliths [

39,

40]. High Al

2O

3 (>10 wt.%) coupled with K

2O/Na

2O < 1 supports crustal contamination [

40,

41], although these signatures may also reflect contributions from recycled oceanic lithologies (sediment-derived melts) or eclogites in the mantle source.

Ultramafic alkaline systems rarely provide homogeneous samples [

42]. These mineralogical and geochemical features complicate whole-rock chemical classification, which requires homogeneous samples for reliable discrimination. Furthermore, the coexistence of multiple intrusive pulses—documented in global kimberlite provinces [

43] as well expressed in the PKN—challenges the interpretation of bulk-rock geochemistry. Distinguishing true magmatic variability from sampling bias remains a major issue in kimberlite–lamproite studies, and analytical limitations remain challenging [

44,

45,

46]. Quantifying error emphasizes the need for mineral-chemistry-based classifications, microanalytical validation, and further discussions within the kimberlite–lamproite research community.

5.3. Magma Genesis and Evolution

An additional complication arises from the intermixing of these two magma types, which introduces significant uncertainty in reconstructing their magmatic evolution. These associations raise the question of whether observed lithological diversity represents a differentiation continuum or discrete magmatic pulses. Mitchell’s model [

9] suggests that extrusive and intrusive facies may preserve distinct mineralogies and textures, with olivine-rich, less evolved bodies forming at depth and phlogopite-rich compositions reflecting shallow, volatile-rich regimes. However, a straightforward genetic link between kimberlites and lamproites seems difficult to support, as modern models attribute them to fundamentally different mantle sources and volatile regimes: CO

2-rich metasomatized peridotite for kimberlites versus H

2O-rich, strongly enriched lithospheric mantle for lamproites [

44,

45]. These distinct signatures point to discrete melting events rather than a single evolutionary lineage.

The reclassification of the PKN’s ultrapotassic rocks under this modern framework resolves longstanding ambiguities. Kimberlite Braúna is now clearly differentiated from phlogopite-rich lamproitic bodies (SFC lamproite variety). The former exhibits high MgO (15%–30%), very high Ni (up to 1172 ppm) and Cr (up to 2500 ppm), minimal crustal contamination and preserved mantle xenocrysts, consistent with rapid ascent through thick lithosphere—a hallmark of diamondiferous systems. However, post-emplacement alteration, extensive serpentinization, and carbonation, as evidenced by high LOI (5%–15%), may have degraded diamond stability. The latter records extensive interaction with crustal fluids, elevated SiO2 (up to 80%), barite-carbonate veining, and cristobalite, features typical of shallow lamproitic systems affected by hydrothermal overprinting and assimilation of quartz-rich lithologies. While such processes diminish diamond potential, they mirror features observed in high-grade systems like the Argyle lamproite (Australia), where secondary alteration coexists with diamond-rich zones at depth. This paradox highlights the need to assess deeper, less altered facies in the PKN, particularly where Braúna and Lamproite SFC varieties intersect.

Compared to classic kimberlites, which typically present SiO

2 (20%–35%), MgO (15%–30%), and Ni (500–2000 ppm), the analyzed samples exhibit greater variability: SiO

2 ranges from 23.9 to 80.1% (due to alteration), MgO varies from 0.77 to 30.6% (reflecting mantle heterogeneity and secondary processes), and Ni ranges from 27 to 1172 ppm (lower values indicating olivine loss). Petrogenetically, the data suggest mantle heterogeneity, with variations in Nb, La, and Ce (e.g., NS 3385 T vs. FV-R-502B) (

Figure 7) indicating multiple mantle sources, including enriched and depleted reservoirs. Rapid ascent is supported by the preservation of mantle xenoliths (e.g., peridotites in FV-R-499) and high MgO contents, implying ultrafast ascent without significant crustal assimilation.

The coexistence of olivine- and phlogopite-dominated lamproites within single bodies suggests either (1) magma mingling of distinct mantle-derived melts or (2) polybaric crystallization during ascent. The former is supported by textural evidence of mingling (e.g., olivine-phlogopite aggregates in

Figure 3B), while the latter aligns with Mitchell’s [

9] model of kimberlite–lamproite differentiation in multi-stage conduits.

5.4. Global Comparisons

Geodynamically, the PKN’s ultrapotassic magmatism (K2O up to 7.8%) likely originated from metasomatized lithospheric mantle, enriched by Paleoproterozoic subduction during the Transamazonian orogeny. This aligns with regional post-orogenic magmatism (e.g., Morro do Afonso Syenite and Itiúba Syenite) and mantle metasomatism recorded in xenocrysts. The São Francisco Craton’s reactivation during Neoproterozoic rifting may have triggered melting of this enriched mantle, producing the PKN’s diverse “kimberlitic” pulses.

This interpretation is further reinforced through comparison with global analogs. Braúna Kimberlite shares affinities with archetypal kimberlites (e.g., Kimberley, South Africa) in MgO-Cr-Ni systematics but diverges in its ultrapotassic signature, akin to orangeites (Group II kimberlites) [

5]. Meanwhile, the SFC lamproite variety parallels lamproites from the Leucite Hills (USA) and West Kimberley (Australia), where phlogopite-rich matrices and hydrothermal textures dominate [

2]. They share traits with the Argyle lamproite: phlogopite-rich matrices, LREE-enriched signatures, and hydrothermal overprinting that masks diamond content near the surface.

By comparing the PKN to world-class systems such as the Argyle lamproite (Australia) and Kimberley kimberlites (South Africa), this study highlights both convergent and divergent aspects of alkaline magmatism in cratonic settings. At Argyle, surface samples initially showed low diamond grades, but deeper mining revealed high-quality diamonds in unaltered hypabyssal facies [

47,

48], a pattern suggesting that the PKN’s SFC lamproite variety bodies may conceal diamond-rich zones at depth. Hydrothermal overprinting at Argyle degraded near-surface diamonds but preserved deeper deposits [

9], a process likely active in the PKN given the SFC lamproite variety’s high loss on ignition (LOI; up to 27.5%). However, the PKN lacks Argyle’s large-scale volcaniclastic deposits, pointing to differences in eruption dynamics or preservation [

48].

In contrast, the archetypal Group I kimberlites of Kimberley (South Africa) offer insights into the Braúna kimberlites. Both systems exhibit high MgO (15%–30%), chromium (>1000 ppm), and nickel (>500 ppm). Kimberley’s hypabyssal facies host intact diamonds due to rapid magma ascent [

9], a process inferred for Kimberlite Braúna bodies given their preserved mantle xenocrysts. Key differences include the PKN’s ultrapotassic geochemistry (K

2O up to 7.8% vs. ~1%–3% in Kimberley) and the absence of significant diamond recovery in surface samples, likely due to intense tropical weathering [

49,

50].

Globally, kimberlite–lamproite provinces are associated with cratonic margins reactivated during rifting or plume activity [

49]. The PKN aligns with this trend, as Paleoproterozoic mantle metasomatism [

50] was likely reactivated during Neoproterozoic rifting of the São Francisco Craton. However, the coexistence of kimberlite-like (Braúna) and lamproite-like (Aroeira) magmas in a single province remains rare, highlighting the PKN’s petrological complexity and offering a unique natural laboratory to study alkaline magma genesis. This duality positions the PKN as a hybrid transitional system [

49,

50], bridging kimberlite and lamproite end-members—a rarity in cratonic settings.

5.5. Exploration and Metallogenic Implications

Syenite–lamprophyre–gold associations, as identified within the Serrinha Nucleus, have been attributed to both orogenic and anorogenic environments, with geodynamic interpretations pointing to either subduction-driven mantle enrichment or continental rift processes [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. The occurrence of rocks of lamproitic affinity as dykes and xenoliths within the syenites results from the bimodal nature of this plutonic complex. Similar lamprophyric occurrences are well documented in other syenites within the SFC as Araras, Serra do Pintado e Agulhas-Bananas, SerN; Itiúba, Santanapolis, Sao Felix, Anuri, SCMB; and even in the Southwest region of SFC, Guanambi, Ceraima, Estreito [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], revealing a regional pattern of ultrapotassic syenite-lamprophyre magmatism at the Paleoproterozoic (2.0 to 2.1 Ga). In the southwestern Serrinha Nucleus, lamprophyres are also spatially associated with gold deposits, as observed at the Maria Preta Au-Mine [

46], suggesting a potential genetic link between these melts and the ore mineralization typical of the classical trilogy syenite-lamprophyre-carbonatite [

46,

47,

48].

For exploration, Braúna’s kimberlite high MgO and Ni/Cr ratios prioritize targets like Braúna 3 and 21 for deep drilling. Conversely, the SFC lamproite association with metasomatic fluids (evidenced by LILE enrichment: Ba up to 2.68% and La/Yb > 100) suggests potential for rare metal mineralization (e.g., Nb and Ta), as seen in the Alto Paranaíba Province (Brazil). These findings impact historical classifications that conflict between the two magma types, often leading to misinterpretations of their diamond potential and geodynamic significance. The distinctions have major exploration implications: Braúna kimberlites preserve the strongest indicators of diamond potential, while SFC lamproite varieties may host Nb-Ta-REE enrichment, paralleling Nb-Ta-REE-enriched kamafugite and lamproite systems in the Alto Paranaiba Province (Brazil). Both regions exhibit niobium-tantalum anomalies and barium-strontium enrichment, linked to carbonate-rich mantle metasomatism [

49]. Alto Paranaíba’s deposits, such as Catalão I, demonstrate that lamproitic systems can transition from diamond- to critical-metal-dominant mineralization with depth, a model applicable to the SFC lamproite variety [

10,

51]. This underscores the PKN’s potential not only for diamonds but also for strategic metals like niobium and rare earth elements.

Diamond potential varies strongly among samples. Promising samples include FV-R-509 (999 ppm Ni, 0.13% Cr

2O

3) and FV-R-499 (962 ppm Ni, 0.15% Cr

2O

3), which display high MgO (23.6%–25.1%) and elevated Cr contents, consistent with derivation from mantle sources within the diamond stability field under high geothermal gradients. Although Cr is commonly associated with pyrope garnet, it may also be hosted—often more prominently—by Cr-rich spinel; the presence of these Mg-rich spinels in the samples further supports their diamond potential [

10]. In contrast, evolved or contaminated samples with low MgO and Ni display limited diamond transport potential. Barren samples such as FV-R-502B (167 ppm Ni, 0.77% MgO) and FV-R-511 (2.22% MgO) show low concentrations of compatible elements, suggesting they represent more evolved or contaminated magmas that are unlikely to have transported diamonds.

The analyzed samples represent a spectrum from primary lamproites, rich in MgO and compatible elements, to altered or contaminated bodies with signatures modified by hydrothermal and crustal processes. Samples like FV-R-515A and NS 3385 T, with high Ni, Cr, and LREE contents, are prioritized for deep mantle studies and diamond prospecting. The compositional diversity underscores the petrogenetic complexity of alkaline magmatism in the SFC, linked to extreme geodynamic environments and multiscale interactions among magma, fluid, and host rocks.

The main distinction is based on specific geochemical criteria: Braúna kimberlites, characterized as primary and potentially diamondiferous, and SFC lamproites, which show signs of alteration or contamination. The relationship between these two types and their geological context highlights differences in origin and dominant processes. Braúna kimberlites are associated with a deep mantle source, rapid ascent, and the preservation of xenoliths, represented by samples such as FV-R-499 and FV-R-509. In contrast, the SFC lamproites are linked to shallower or altered systems, influenced by crustal assimilation and hydrothermalism, as observed in samples like FV-R-507C and NS 3385 B1.

This classification provides important practical implications. Braúna kimberlites should be prioritized in mantle composition studies, with FV-R-499 and FV-R-509 serving as key examples. Meanwhile, the SFC lamproites are relevant for understanding post-magmatic alteration processes, represented by samples such as FV-R-504 and NS 3385 B1-B3.

Reclassification into Braúna kimberlites and SFC lamproites sharpens exploration strategies in the PKN, which can draw lessons from global analogs. The Argyle model suggests prioritizing geophysical surveys to locate unaltered hypabyssal facies in the SFC lamproite variety, as surface alteration may mask diamond potential [

51]. The Kimberley model emphasizes focusing on Kimberlite Braúna bodies for traditional diamond exploration while accounting for Brazil’s aggressive weathering, which may require deeper sampling. Meanwhile, the Alto Paranaíba model advocates evaluating SFC lamproites for Nb-Ta-REE mineralization using soil geochemistry and mineral chemistry, such as identifying Nb-rich rutile.

6. Conclusions

This study redefines the Nordestina Kimberlite Province as a hybrid ultrapotassic complex system, hosting two compositionally and genetically distinct magma types: (i) primitive Braúna kimberlites, derived from a metasomatized lithospheric mantle source, and (ii) SFC lamproites, a phlogopite-rich variety strongly modified by crustal assimilation and pervasive hydrothermal alteration.

The SFC lamproites are interpreted to derive from a deep mantle source that was progressively metasomatized during multiple subduction-related events from the Paleoproterozoic to the final consolidation of the São Francisco Craton. These long-lived metasomatic processes modified the lithospheric mantle, enriching it in incompatible elements and volatiles, and creating favorable conditions for the generation of lamproitic magmas. The ascent and emplacement of these melts were likely controlled by tectonic reactivations, which promoted the reuse of ancient faults and fracture systems, providing efficient pathways for magma migration and emplacement within the cratonic framework.

The Braúna kimberlite group preserves key indicators of mantle provenance and diamond stability—including high MgO, Ni, and Cr contents, Cr-rich spinel, and abundant mantle xenocrysts—yet its shallow facies are heavily weathered. As a result, the economic potential of these bodies can only be fully evaluated through deeper-level exploration to bypass altered near-surface features. In contrast, the SFC lamproites display elevated SiO2, P2O5, incompatible-element enrichment, and intense alteration consistent with near-surface hydrothermal processes, offering insights into post-magmatic processes and rare element enrichment, such as Nb-Ta-REE mineralization. Together, these compositional end-members reflect a heterogeneous mantle influenced by long-lived metasomatism and episodic reactivation during Proterozoic rifting. These signatures highlight its importance not only for diamond prospectivity but also for understanding post-magmatic modifications and for guiding future assessments of Nb-Ta-REE critical metal potential.

Petrogenetically, the coexistence of kimberlitic and lamproitic signatures reflects the interplay between Paleoproterozoic mantle metasomatism and Neoproterozoic lithospheric reactivation, consistent with regional patterns of South American alkaline magmatism. This model explains the variable degrees of hybridization, xenolith entrainment, and crustal contamination that characterize the PKN suite.

Methodologically, this work demonstrates the value of integrating SEM-EDS imaging, advanced optical petrography, XRD-Rietveld refinement, and lithogeochemical analysis, especially in highly weathered tropical terrains. The results validate the mineralogical–geochemical criteria of Scott Smith [

1] and resolve long-standing classification controversies by firmly distinguishing kimberlite-type from lamproite-type magmas within the province.

Future research (i) should prioritize U-Pb geochronology—to constrain emplacement ages and temporal relationships; (ii) detailed xenocryst and xenolith chemistry—to map lithospheric mantle architecture beneath the northeastern SFC; and (iii) radiogenic isotope tracing—to quantify crustal assimilation and refine petrogenetic models.

In conclusion, PKN’s dual kimberlite–lamproite affinity bridges global analogs, offering insights into alkaline magma genesis and mineralization. While its diamond potential remains sub-explored, lessons from Argyle, Kimberley, and Alto Paranaíba provide a roadmap for targeted exploration in this emerging province. By bridging petrological complexity with exploration pragmatism, this work advances the understanding of alkaline magmatism in cratonic terranes and underscores the São Francisco Craton’s untapped potential as a frontier for diamond and critical mineral discovery associated with lamproitic systems.