Abstract

Illite, a clay mineral, is used in diverse fields such as agriculture, cosmetics, and the food-related industry due to its many advantages, including biocompatibility, UV protection, antibacterial activity, high adsorption capacity for hazardous substances, and cost-effectiveness. However, its relatively large size, broad size distribution, and irregular morphology limit its broader applications. This study investigated the control of particle size and distribution during wet ball milling (WBM) using five media—acetone, ethanol, water, aqueous NaCl solution, and aqueous phosphoric acid solution—over milling times of 2–10 h. Prolonged milling progressively reduced particle size and narrowed the size distribution. Acetone and ethanol exhibited notably superior size-reduction performance compared with the aqueous systems, among which phosphoric acid solution showed the least effectiveness, likely attributed to variations in their physicochemical properties, including viscosity (η) and surface tension (σ), and in their interfacial interactions with illite. Optimal milling in acetone for 10 h resulted in the smallest particles (~700 nm), the narrowest distribution, the largest specific surface area, and the highest moisture retention. Overall, these findings demonstrate that the physicochemical properties of the milling medium, which govern WBM efficiency through fluid dynamics and particle–medium interactions, thereby determine the size and distribution of milled particles.

1. Introduction

Illite is a non-expandable 2:1 clay mineral composed of a single octahedral sheet sandwiched between two tetrahedral sheets, and it is one of the most abundant clay minerals in the Earth’s crust, widely distributed in sedimentary and low-grade metamorphic environments [1,2]. Its chemical formula is commonly described by the generalized formula (K,H3O)(Al,Mg,Fe)2(Si,Al)4O10(OH)2, which reflects compositional variability, partial interlayer K deficiency, and cationic substitutions typically observed in natural illitic materials [3]. For quantitative reference, the end-member illite composition expressed as (K,Na)0.95(Al1.81Fe0.01Mg0.19)(Si3.35Al0.75)O10(OH)2 is also considered [4]. Large natural illite deposits are present in the Yeongdong area of Chungcheongbuk-do, South Korea, and have been studied for industrial mineral applications [5,6]. Illite exhibits beneficial characteristics, including natural abundance, biocompatibility, antibacterial activity, high adsorption capacity for heavy metals and pollutants, skin-brightening effects, UV-blocking properties, extensive reserves, and cost-effectiveness [7,8,9]. Owing to these attributes, illite has been applied in diverse fields, including agriculture, cosmetics, and food-related industries [10,11,12].

Clay minerals such as illite serve as essential resources across various industries, and their particle size and distribution significantly influence their physicochemical properties. Finer particles exhibit enhanced moisture-retention ability and interfacial interactions, making them suitable for analytical and functional applications. These attributes also contribute to the performance and practical function of clay-based materials [13]. Particle-size control has been achieved through mechanical processes, including ultrasonication, planetary milling, ball milling, air-jet milling, vibration milling, tumbling milling, and attrition milling [14,15,16,17,18]. Mechanical grinding is particularly promising because it not only produces fine mineral powders but also induces structural or chemical modifications, thereby enhancing their inherent properties or imparting new functionalities [19,20].

Ball milling is a well-known particle fragmentation process in which particles are split and crushed by mechanically applied pressure, while the fragmented particles simultaneously tend to agglomerate to reduce their surface energy [21]. Ball milling can be performed in either dry or wet conditions, and each condition influences the final particle characteristics depending on the operational parameters [22]. In dry ball milling (DBM), variables such as equipment type, milling time, rotation speed, container filling volume ratio, mass ratio of powders to balls, and initial particle size and hardness govern the resulting physical and chemical properties of the particles [23]. Wet ball milling (WBM) provides several additional advantages, including lower excess heat generation, higher energy efficiency, reduced dust generation, minimized crystallinity loss, reduced tendency for particle agglomeration, and production of finer particles [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

To implement an effective WBM process, the selection of an appropriate milling medium is crucial for controlling particle size [21]. Appropriately selected milling media not only enhance grinding efficiency but also enable the production of finer particles and more uniform particle-size distributions [25,26]. In addition, the physicochemical characteristics of the milling media can prevent particle re-aggregation and influence the size, structure, morphology, porosity, and chemical composition of the resulting particles [26,27,28,29,30]. Moreover, the structure and functionality of particles under external stress strongly depend on the physicochemical characteristics of the milling media, which ultimately determine the resultant powder morphology [31]. While several studies have explored the influence of grinding media on clay minerals, a systematic correlation between fluid dynamics and interfacial properties remains insufficient.

In this study, WBM was performed for various milling times (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h) in five different milling media with distinct physicochemical properties, including viscosity (η) and surface tension (σ), as well as interfacial interactions, to achieve reduced particle size and more uniform size distribution, followed by systematic characterizations of the resulting particles. Considering the potential use of illite in health-related applications, such as cosmetics, foods, and pharmaceuticals, milling media with low toxicity and minimal biological risk were selected. The chosen media included acetone, ethanol, water, an aqueous NaCl solution, and an aqueous phosphoric acid solution. Water is commonly used as a milling medium, whereas acetone and ethanol are employed as organic solvent-based milling media. In addition, an aqueous NaCl solution was used to evaluate the ionic (salt) effect, and an aqueous phosphoric acid solution was selected to explore specific interfacial interactions with illite particles. By examining the evolution of illite particle size, size distribution, and surface characteristics, such as morphology, surface area, and moisture retention capacity, as a function of milling time across different media, this study elucidates how milling medium-dependent physicochemical properties modulate the WBM efficiency of illite particles, thereby enhancing their potential as multifunctional materials for bio-related applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The illite used in this work was purchased from Yongkoong Illite Co., Ltd. (Yeongdong, Republic of Korea), with a nominal particle size of 2000 mesh. Acetone and ethanol were purchased from Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd. (Seoul, Republic of Korea) and used as supplied without further purification. Sodium chloride and phosphoric acid were purchased from Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co., Ltd. (Siheung, Republic of Korea), and then they were dissolved in deionized (DI) water to prepare their respective aqueous solutions at 5 wt%. The desktop ball mill and zirconia balls (ZrO2, diameter: 2 mm) were purchased from LK Lab Korea Co., Ltd. (Namyangju, Republic of Korea).

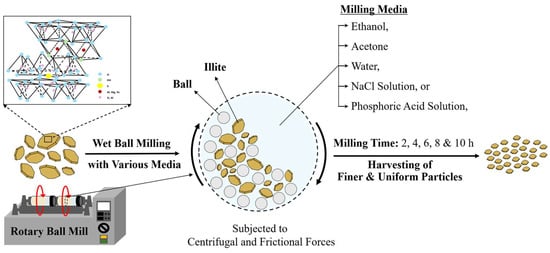

2.2. Wet Ball Milling (WBM) Procedure for Controlled Illite Particle Size

The WBM process for particle-size control of illite was carried out using a conventional benchtop rotary ball mill with two containing bottles. The milling conditions are as follows: a mixture of 20 g of illite particles and 120 mL of a milling medium (acetone, ethanol, water, aqueous NaCl solution, or aqueous phosphoric acid solution) was placed into a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) bottle containing 1 kg of ZrO2 balls. The two bottles containing the mixture were securely mounted on the benchtop rotatory ball miller and operated at room temperature (~20 °C) at 300 rpm for the specified milling times of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h. To prevent thermal accumulation during the milling process, we used an intermittent milling protocol with a 10 min cooling interval every 2 h. Figure 1 shows a schematic of the WBM process of illite particles. The ball-milled illite particles were then dried in an oven at 60 °C and subsequently stored in a desiccator prior to further characterization. Illite samples with reduced particle size obtained via the WBM process, named according to the used milling medium and time, are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the WBM process for illite particles performed using a benchtop rotary ball mill across five different milling media (acetone, ethanol, water, aqueous NaCl solution, and aqueous phosphoric acid solution) for milling times ranging from 2 to 10 h.

Table 1.

Illite samples processed by WBM under various milling times and media.

2.3. Characterizations

2.3.1. Illite Particle Size, Shape, and Distribution Analysis

The morphology and microstructure of illite particles, as well as the milling time-dependent changes in particle size and shape across the different milling media, were examined using a JSM-7610F field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). All specimens were coated with platinum prior to imaging, and observations were carried out at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

Particle size distribution (PSD) of illite particles was determined by analyzing high-resolution FE-SEM images with ImageJ software (version 1.54), in which the diameters of more than 200 individual particles were quantified for each sample. Based on the measured data, PSD histograms were generated and statistically evaluated using the collected particle-size measurements. Based on the PSD results, the effective average particle size was quantified using the Sauter mean diameter (SMD), which serves as an equivalent metric for the energetic characterization of particle fragmentation. This approach facilitates a consistent comparison of surface-to-volume ratios across different samples and reflects the efficiency of particle breakdown during milling by correlating mechanical energy input with the resultant increase in specific surface area. The SMD was determined according to the following expression:

where D is the diameter of particles, and dN denotes the fraction of particles whose diameter is included within the specified interval [32].

2.3.2. Chemical and Structural Analysis of Illite Particles

Illite particle samples wet-ball-milled for 10 h in each milling medium were collected and dried in a dry oven, and the medium-dependent chemical structural changes were subsequently examined using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. A Nicolet Summit X spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was employed for the measurements, which were performed in the 4000–400 cm−1 range with a resolution of 0.6 cm−1.

The crystal structure of both pristine and ball-milled illite particles was examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD) to assess whether the lattice structure was altered. Analyses were performed using a D2 Phaser diffractometer (Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany). The light source used was a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å).

2.3.3. Specific Surface Area (SBET) Analysis

Illite particles milled in acetone, the medium that provided the most effective particle size reduction, were subjected to Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis to quantify changes in specific surface area (SBET) as a function of milling time (0, 2, 6, and 10 h). BET measurements were conducted using the ASAP 2020 Plus analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). The SBET of pristine and ball-milled illite particles was determined from nitrogen adsorption isotherms fitted to the BET model. The BET equation is expressed as follows:

where υ is the volume of N2 adsorbed at standard temperature and pressure (STP), υm is the volume to form a monolayer on the surface, P is the equilibrium pressure of the gas, P0 is the saturation vapor pressure of the N2 at the measurement temperature, P/P0 is the relative pressure, and C is the BET constant [33]. The υm obtained from Equation (2) was then used to calculate SBET according to Equation (3),

where NA is Avogadro’s number, Ac is the molecular cross-sectional area of N2, and Vm represents the molar volume of N2 gas at STP [34]. Prior to analysis, all samples were degassed at 350 °C for 24 h under vacuum to remove adsorbed impurities.

2.3.4. Moisture Evaporation Content (MEC) Measurements

To evaluate how particle-size reduction influences the apparent moisture content, the moisture content of pristine illite and acetone-milled illite particles was quantitatively measured using a moisture analyzer (MX-50, A&D company, Tokyo, Japan). Approximately 0.1 g of each sample was placed on the analyzer, and the mass change was continuously monitored until the moisture was removed entirely at a controlled temperature of 50 ± 1.0 °C. All measurements were performed under controlled ambient conditions of 22 °C and 97% relative humidity. The moisture evaporation content (MEC) was calculated by the following relationship: MEC = (M1 − M2)/M1 × 100%, where M1 is the weight before drying, and M2 is the weight after drying [35]. The maximum moisture content was also obtained from the saturation plateau of the MEC curve, representing the equilibrium moisture retained within the illite particles after the completion of rapid surface evaporation. Moreover, the initial moisture evaporation rate (RiM) was determined from the slope of the MEC curve in the early linear region.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Milling Medium and Time on Particle Size and Size Distribution

3.1.1. Morphological Evolution of Illite Particles During WBM

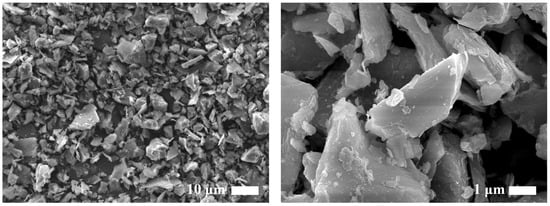

Figure 2 presents SEM images illustrating the surface morphology and internal microstructure of pristine illite particles. The SEM results showed that the illite particles consist of thin lamellar platelets formed by stacked silicate sheets, with edges displaying pronounced, irregular, and sharp boundaries, indicating brittle fracture. In addition, pristine illite particles showed substantial heterogeneity in both particle size and overall geometry.

Figure 2.

SEM images of pristine illite particles prior to ball milling (left: lower magnification and right: higher magnification).

Following the characterization of pristine illite particles, Figure 3 presents the progressive morphological evolution of illite particles subjected to WBM using five different milling media (acetone, ethanol, water, aqueous NaCl solution, and aqueous phosphoric acid solution) over increasing milling time from 2 to 10 h. All WBM processes induced gradual exfoliation and fragmentation of lamellar platelets, resulting in reduced particle size while maintaining their sharp, irregular fracture surfaces. The extent of fragmentation, however, varied depending on the milling medium.

Figure 3.

SEM images of illite particles before and after wet ball milling (WBM) with different milling media (acetone, ethanol, water, aqueous NaCl solution, and aqueous phosphoric acid solution) and milling times (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h). Illite particle samples milled in (a) acetone, (b) ethanol, (c) water, (d) aqueous NaCl solution, and (e) aqueous phosphoric acid solution.

Among the media, the WBM in acetone and ethanol produced the most substantial morphological changes (Figure 3a and Figure 3b, respectively). Both media showed significant fragmentation, yielding finer particles and a more uniform size over time, with minimal visible agglomeration, indicating a highly effective size reduction. In contrast, the WBM in water (Figure 3c) and NaCl solution (Figure 3d) showed relatively lower milling efficiency. Although the particle size decreased over time, partially fractured particles and mild aggregation persisted. The WBM in aqueous phosphoric acid solution showed the lowest particle-size reduction efficiency among all media (Figure 3e). The acid solution produced larger residual fragments, and dense agglomerates persisted even after prolonged milling. These differences visually indicate that the physicochemical properties of the milling media substantially influence fracture pathways and dispersion states during milling.

3.1.2. PSD and Effective SMD Reduction

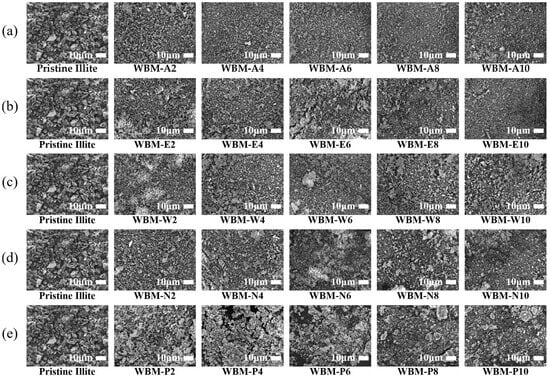

To quantitatively support the morphological evolution of the illite particles observed in SEM, the PSDs of illite particles obtained under various milling media and times were examined (Figure 4). The effective average particle diameter was calculated using the Sauter mean diameter (SMD) for all milling systems (Table 2). Pristine illite particles exhibited a broad polydisperse distribution with an SMD of 9.94 ± 2.48 μm, reflecting their intrinsic heterogeneous morphology. Upon WBM treatment, all PSD curves shifted progressively toward smaller values for all media, accompanied by a transition from a broad to a narrower distribution, indicating effective particle fragmentation over milling time.

Figure 4.

Particle size distributions (PSDs) of illite particles before and after wet ball milling (WBM) using different milling media (A: acetone, E: ethanol, W: water, N: aqueous NaCl solution, and P: aqueous phosphoric acid solution) and various milling times. (a) Pristine illite particles and (b–f) illite particle samples milled for 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h, respectively.

Table 2.

Sauter mean diameter (SMD) of illite particles milled in five different milling media over various milling times.

Among all milling conditions, longer milling time yielded a narrower distribution and a smaller average particle size, and the WBM in acetone (WBM-A) produced the most effective particle size reduction, showing the most pronounced leftward PSD shift, a sharply contracted distribution curve, and the smallest SMD of 0.73 ± 0.06 μm at 10 h (WBM-A10). The WBM in Ethanol (WBM-E) followed, yielding similarly narrow distributions but with slightly larger SMD (0.88 ± 0.08 μm). In contrast, the WBM in aqueous systems (water and NaCl solution, WBM-W and WBM-N, respectively) exhibited less size reduction (1.10 ± 0.09 μm and 1.25 ± 0.05 μm, respectively) and broader residual distributions. The WBM in phosphoric acid solution (WBM-P) produced the least effective size reduction (1.45 ± 0.04 μm), consistent with size distribution and SEM observations of persistent agglomerates and larger fragments. The average sizes increased in the order: WBM-A10 < WBM-E10 < WBM-W10 < WBM-N10 < WBM-P10.

The narrowing of PSDs, from broad and asymmetric distributions to narrow and symmetric forms, confirms the improved uniformity associated with effective size control via the milling process. Collectively, the SEM and PSD analyses consistently demonstrate that organic solvents surpass aqueous media in achieving uniform particle size reduction.

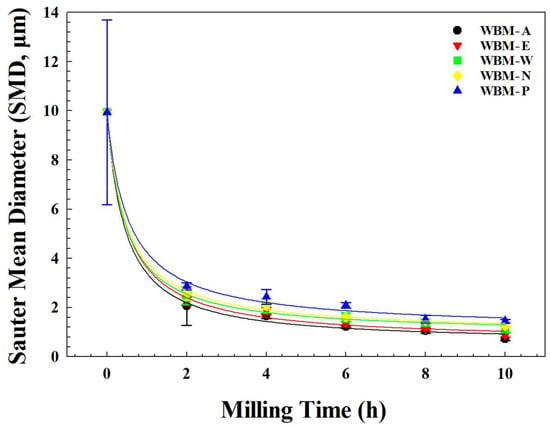

Figure 5 illustrates the SMD of pristine illite particles and milled illite particles as a function of milling time. To quantitatively evaluate the kinetics and provide a statistical basis for the media-dependent performance, the experimental data were fitted using a modified power-law model: SMD(t) = y0 + a · (t + 1/2)−b, where y0 denotes the asymptotic equilibrium particle size which indicates theoretical grinding limit caused by the equilibrium between the rate of mechanical cleavage and the rate of particle re-aggregation. In this model, a represents a fragmentation constant associated with the primary breakage of pristine particles, and b serves as the milling efficiency exponent, which reflects how the kinetic energy of the milling media is effectively transferred to the particles. The high coefficients of determination (r2 > 0.99) across all media validate the statistical significance of the medium-dependent kinetics. The fitting parameters of the modified power-law model for time-dependent SMD are summarized in Table 3. The results for all samples show a biphasic reduction behavior. An initial rapid decrease in effective particle size was shown within the first 2 h, corresponding to the primary breakage stage, followed by a secondary fragmentation stage characterized by a gradual decline and approach to the limit y0. Notably, acetone and ethanol consistently produced lower y0 values (0.512 μm and 0.624 μm, respectively) and higher b values (1.054 and 0.982, respectively) throughout the milling duration, confirming their superior milling performance in achieving sub-micron scales (~700 nm). In contrast, water, NaCl solution, and phosphoric acid show significantly higher y0 values (0.856–1.215 μm) and lower b values (0.654–0.844), and exhibit slower transformation and maintain larger particle sizes, reflecting lower effectiveness in particle size reduction and maintaining larger residual particle size due to dampened momentum transfer.

Figure 5.

Sauter mean diameter (SMD) of illite particles milled in five different milling media (A: acetone, E: ethanol, W: water, N: aqueous NaCl solution, and P: aqueous phosphoric acid solution) as a function of milling time. The solid lines represent the non-linear curve fitting based on the modified power-law model, SMD(t) = y0 + a · (t + 1/2)−b (r2 > 0.99), where y0 denotes the asymptotic equilibrium particle size (grinding limit) and a and b indicate the fragmentation constant and the milling efficiency exponent, respectively.

Table 3.

Fitting parameters of the modified power-law model for time-dependent SMD reduction.

3.1.3. Effect of the Physicochemical Properties of Milling Medium on WBM Efficiency

The distinct differences in milling performance among the five media were considered to be due to physicochemical properties associated with the following key factors: (i) viscosity (η), (ii) surface tension (σ), and (iii) particle–medium interfacial chemistry and interactions. These factors collectively govern the hydrodynamic behavior of the slurry, collision efficiency, energy transfer efficiency, and dispersion stability during WBM. The physicochemical properties of the five milling media considered in this study, including η, σ, density (ρ), molecular weight (Mw), and their characteristic chemical interactions with illite particles, are summarized in Table 4. Here, the ρ and Mw of the milling media showed no direct correlation with milling efficiency; however, they affect fluid momentum, collision frequency, and energy dissipation, thereby modulating milling dynamics, although they are not the dominant controlling parameters.

Table 4.

Physicochemical properties of the milling media used in the WBM process.

The variations in size-reduction efficiency observed across these media can be fundamentally elucidated by the synergy between fluid dynamics and interfacial science. First, the effect of milling-medium η, which is a major factor governing particle motion within the slurry, on the milling efficiency was examined. Milling media with lower η enabled faster slurry circulation and more efficient transfer of kinetic, impact, and shear energy from milling balls to illite particles by reducing drag forces, thereby generating more effective collisions, in agreement with previously reported mechanochemical findings that a milling medium with lower η minimizes drag forces on milling beads and maximizes collision stress intensity [31]. Acetone, with the lowest η among the media, produced the highest particle size reduction efficiency, while the higher η values of water, NaCl solution, and phosphoric acid solution dampened shear and impact forces, resulting in lower particle size reduction efficiency. Because acetone showed the lowest η among all media, it enabled more rapid slurry flow and more effective momentum transfer between balls and particles, producing stronger shear and impact forces that facilitated fragmentation and reduced particle size. In contrast, water, NaCl solution, and phosphoric acid exhibited higher η, which dampened particle motion and shear and impact forces, thereby reducing milling efficiency. Interestingly, ethanol, despite having a relatively higher η, yielded a high particle size reduction efficiency. This suggests that the fragmentation process is governed not only by the hydrodynamic resistance but also by complex interfacial interactions, which will be further discussed in the following sections.

Another factor affecting the milling efficiency of the milling media is σ defined as the work required to increase a unit area per unit of new surface created [36,37]. Milling media with low σ improved their wetting on the illite surfaces and reduced interparticle friction by minimizing capillary forces and reducing the probability of particle–particle bridging. These effects enhanced particle dispersion stability and further prevented particle re-agglomeration, thus enabling continuous fragmentation. Both acetone and ethanol, with very low σ, suppressed agglomeration and enabled continuous fragmentation throughout the process. Conversely, aqueous systems (water, aqueous NaCl solution, and phosphoric acid solution) with relatively higher σ increased drag force, lowered collision efficiency, and promoted particle clustering, thereby limiting fragmentation efficiency. The superior size reduction in organic media compared to aqueous systems is consistent with reports that organic solvents with lower σ facilitate deeper penetration into the microcracks of clay minerals, enhancing particle breakage [28,29]. This phenomenon is widely recognized as the ‘Rehbinder effect’, in which media with lower σ decrease the energy required for new surface formation by weakening atomic bonds at crack tips, thereby enhancing particle fragmentation [28].

Interfacial chemistry and interactions played a decisive role in milling efficiency. Water molecules form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxy groups on illite particles, creating a robust hydration layer. This layer not only increases fluid resistance (η and associated drag forces) but also acts as a mechanical buffer, known as the ‘cushioning effect’ [30], which dissipates the impact energy from the milling beads and protects the silicate framework from effective fragmentation [30]. In the NaCl solution, the high ionic strength led to the compression of the electrical double layer (EDL) of the illite particles. According to the Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) theory, this compression of the electrical double layer significantly reduces the Debye screening length, which diminishes electrostatic repulsion. This promotes rapid particle re-aggregation, leading to reduced colloidal stability during milling [26]. Such re-aggregation counteracts the mechanical fragmentation process, ultimately resulting in a lower size-reduction efficiency. Moreover, phosphoric acid in water could protonate the –O− groups of illite particles to –OH and participate in a ligand-exchange reaction with surface hydroxyl groups, forming phosphate-bound species (–PO4). This chemical modification further compressed the EDL, enhanced particle–particle adhesion, and hindered effective dispersion, lowering milling efficiency. Consistent with the reports, these enhanced attractive forces and the resulting agglomeration counteract mechanical shear, resulting in relatively larger residual particle sizes and sustained re-agglomeration during milling [26,37].

Collectively, the PSD and SMD analyses demonstrated that organic media, particularly acetone and ethanol, yield more uniform particles and effectively reduce particle size, compared to aqueous systems. This result is primarily attributed to the synergy between lower η and σ, which enhances energy transfer and facilitates crack propagation via the Rehbinder effect, while suppressing particle re-aggregation. Furthermore, the relatively weak particle–medium interfacial interactions in organic solvents improved dispersion stability, leading to finer, more uniform illite particles. Taken together, these findings elucidate how η, σ, and particle–medium interfacial chemistry collectively regulate fragmentation dynamics during WBM. This study thus provides a comprehensive mechanistic framework for selecting optimal milling media to achieve efficient size reduction and structural control of illite.

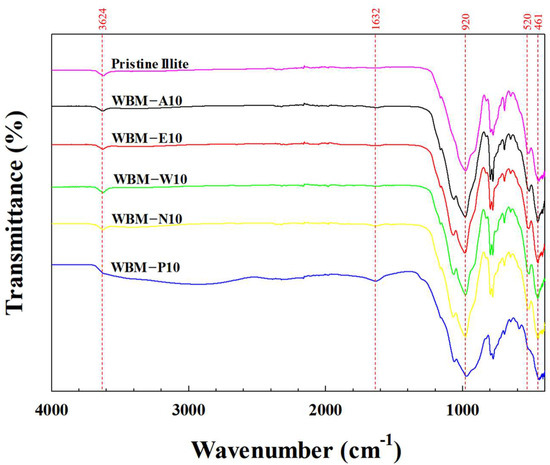

3.2. Media-Dependent Surface Chemistry and Structural Responses of Illite After WBM

The FT-IR spectra of pristine illite particles and illite particles ball-milled for 10 h using five different milling media (A: acetone, E: ethanol, W: water, N: aqueous NaCl solution, and P: aqueous phosphoric acid solution) are shown in Figure 6. The absorption bands observed at 3624 cm−1 and 1632 cm−1 are attributed to the O–H stretching vibration of structural hydroxyl groups in illite particles [38] and the H–O–H bending vibration of residual interlayer or hydrogen-bonded water molecules [39,40], respectively. The absorption bands at 920 cm−1, 520 cm−1, and 461 cm−1 correspond to Al–OH–H bending [41], Si–O stretching [42], and O–Si–O bending vibrations [43], indicating the characteristic aluminosilicate lattice of illite.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of pristine illite particles and illite particles ball-milled for 10 h using different milling media (A: acetone, E: ethanol, W: water, N: aqueous NaCl solution, and P: aqueous phosphoric acid solution).

The FT-IR spectra of WBM-A10, WBM-E10, WBM-W10, and WBM-N10 showed peak positions nearly identical to those of pristine illite particles, demonstrating that the functional aluminosilicate lattice was preserved even after milling. In contrast, WBM-P10 displayed spectra with similar absorption bands to other illite particles; however, it exhibited a significantly broadened and intensified O–H stretching band spanning approximately 3600–2600 cm−1. This broadening is attributed to the formation of phosphate-induced strong hydrogen bonding between phosphoric acid and the surface hydroxyls of illite, likely forming specific P–O···H–O surface complexes [44], together with an increase in the density of surface hydroxy groups (Si–OH and Al–OH) via a possible surface protonation, which demonstrates a distinct interfacial chemical modification not observed with the other milling media. Moreover, the band at 1632 cm−1, assigned to the H–O–H bending vibration of interlayer and adsorbed water, became more intense for WBM-P10. This increase suggests a higher amount of strongly bound water associated with the protonated surface sites and hygroscopic residual phosphate species (P–OH and H2PO4−/HPO42− groups) generated during WBM in phosphoric acid solution.

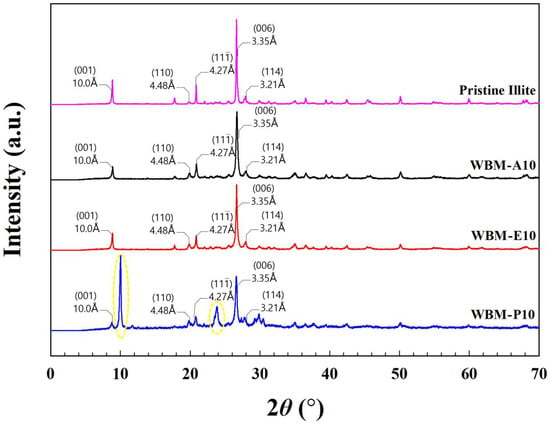

Figure 7 presents the XRD patterns of pristine illite and illite particles ball-milled for 10 h (WBM-A10, WBM-E10, and WBM-P10) in three different milling media: acetone, ethanol, and aqueous phosphoric acid solution, measured over the 2θ range of 0–70°. The characteristic XRD pattern of illite exhibits prominent diffraction peaks at 2θ ≈ 8.8°, 17.7°, 19.8°, 20.8°, 26.6°, and 27.8°. The basal (001) reflection of illite is clearly observed at 2θ ≈ 8.8°, corresponding to a d-spacing (d) of approximately 10.0 Å, as calculated using Bragg’s law (nλ = 2d sinθ, where λ is the X-ray wavelength, d is the interplanar spacing, and θ is the Bragg angle). The presence of this basal reflection indicates the preservation of the non-swelling layered 2:1 phyllosilicate structure characteristic of the monoclinic 2M1 illite polytype after wet ball milling. The d-spacings of the other characteristic illite reflections at 17.7°, 19.8°, 20.8°, 26.6°, and 27.8° are approximately 5.01, 4.48, 4.27, 3.35, and 3.21 Å, respectively, which are provided to facilitate phase identification. In particular, the peaks at 2θ = 8.8°, 19.8°, 20.8°, 26.6°, and 27.8° are indexed to the (001), (110), (11), (006), and (114) crystallographic planes of illite, respectively, and are clearly marked [1,45].

Figure 7.

XRD patterns of pristine illite and illite particles ball-milled for 10 h in three different milling media: acetone (WBM-A10), ethanol (WBM-E10), and aqueous phosphoric acid solution (WBM-P10), over the 2θ range of 0–70°. The characteristic illite reflections indexed to the (001), (110), (006), and (114) crystallographic planes are marked, and the d-spacings (Å) of the major reflections are provided to facilitate phase identification. The notable emergence of reflections at 2θ ≈ 10° and 23.4° in the WBM-P10 pattern is highlighted in yellow.

In WBM-A10 and WBM-E10, the principal peak positions remained the same as pristine illite, indicating the fundamental illite crystal structure was preserved after WBM. No shift in diffraction peak positions and no new reflections were observed, confirming the structural stability of illite under these milling conditions. In contrast, WBM-P10 exhibited a relatively broad feature peak at 2θ ≈ 24° (d ≈ 3.7 Å) and an additional low-angle reflection at 2θ ≈ 10° (d ≈ 8.8 Å), indicating the formation of a partially ordered, phosphate-rich compact interfacial layer induced by chemical interactions with phosphoric acid, rather than interlayer swelling. The coexistence of the peaks at 2θ ≈ 8.8° and 10° suggests the development of a core–shell-like structure, in which a dense phosphate-rich shell forms on the surface while preserving the structural integrity of the highly crystalline 2M1 illite core. Notably, the 8.8° reflection in WBM-P10 showed a significant reduction in intensity and a discernible broadening of peak width quantified by the Kübler Index (KI, representing full width at half maximum (FWHM)) compared to the pristine illite. The KI values were determined to be approximately 0.15 (pristine illite), 0.22 (WBM-A10), 0.20 (WBM-E10), and 0.50 (WBM-P10). This substantial increase in the KI value, together with the attenuation of the intensity for WBM-P10, is primarily attributed to the phase transformation associated with the formation of a new crystalline aluminum phosphate phase. Moreover, the redistribution of the crystalline fraction towards the 10° and 23.4° reflections effectively diminishes the diffraction contribution from the original illite (001) plane. The broad reflection near 2θ ≈ 24° in the WBM-P10 sample is consistent with the formation of a partially crystalline aluminum phosphate phase via chemical reactions between phosphoric acid and the alumina components [46].

Collectively, although phosphoric acid induces surface modification and phosphate-rich interfacial layers, the persistence of the characteristic illite reflections confirms that the fundamental high-crystallinity 2M1 illite framework remains preserved under all WBM conditions.

3.3. Surface-Related Characteristics of Acetone-Milled Illite Particles

Acetone, which exhibited the lowest viscosity and surface tension and the weakest interfacial interaction with illite particles, was identified as the milling medium that produced the most substantial reduction in illite particle size in this work. Therefore, the acetone-milled illite particles were selected for a detailed investigation of their surface-related characteristics. In particular, specific surface area, mesoporous structure, and moisture evaporation and retention behavior were examined, as these properties play critical roles in determining the applicability of clay-based materials in various bio-related fields where hydration control, interfacial stability, and material–cell interactions are essential.

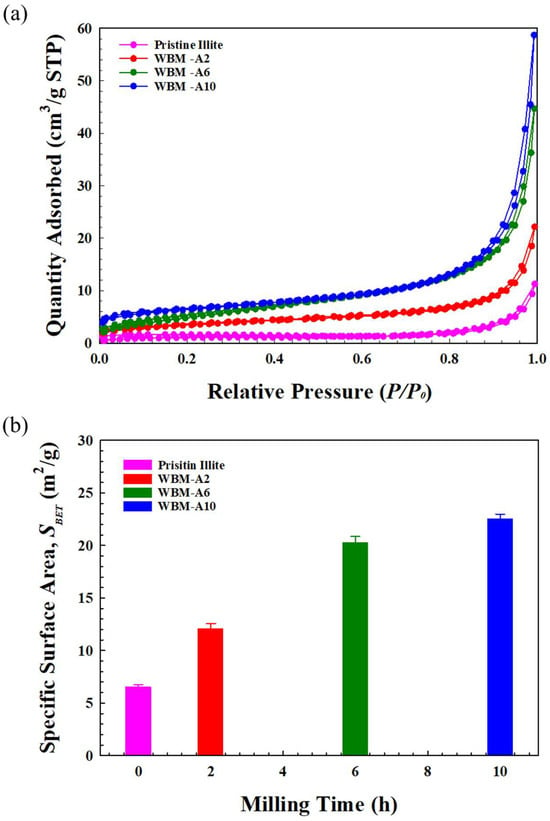

3.3.1. Surface Area and Mesoporous Structure Evolution

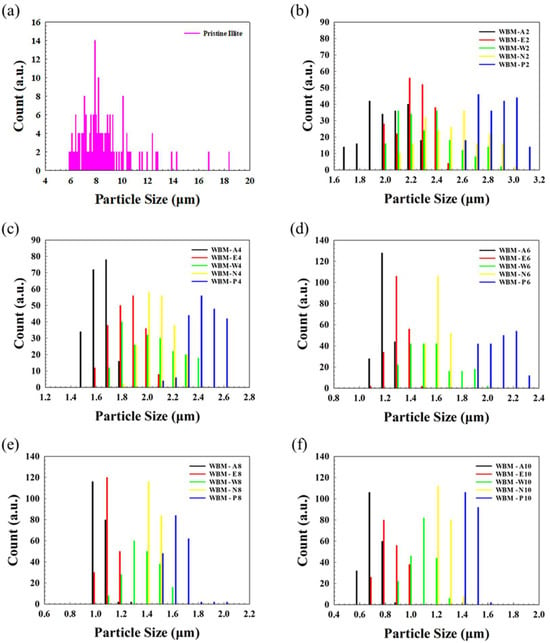

Figure 8a and Figure 8b present the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and the corresponding BET specific surface areas (SBET) of pristine illite particles and the acetone-milled illite particle samples (WBM-A2, WBM-A6, and WBM-A10) for various milling times: 2, 6, and 10 h, respectively. As shown in Figure 8a, all samples followed the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) adsorption model represented by Equation (2). All samples exhibited adsorption curves in which the adsorption amount gradually increased at low relative pressures (P/P0) and then increased rapidly as P/P0 approached unity. According to the IUPAC classification, this behavior corresponds to a Type IV isotherm accompanied by an H3 hysteresis loop, which is characteristic of mesoporous materials composed of plate-like particle aggregates and is reflected by a distinct hysteresis loop that clearly appears in the adsorption–desorption branches and shows a gradual tendency toward loop closure at high relative pressures [40]. In the low relative pressure (P/P0) region (<0.4), the adsorption and desorption curves nearly overlapped, indicating adsorption occurs predominantly through monolayer formation on external surfaces with negligible micropore filling, consistent with the absence of significant microporosity. At higher P/P0 (>0.4), the amount of N2 adsorbed increases sharply due to capillary condensation and multilayer adsorption within mesopores. At this stage, slit-shaped mesopores were formed by the progressive fragmentation and restacking of illite layers during the WBM process [47].

Figure 8.

(a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms as a function of relative pressure (P/P0) and (b) BET specific surface areas (SBET) of pristine illite particles and the illite particles milled in acetone for different milling times: 2, 6, and 10 h.

Meanwhile, the SBET increased systematically with milling time due to progressive particle fragmentation and increased exposure of external and edge surfaces. To explicitly establish the mathematical dependence of surface area evolution on milling duration, the SBET data were fitted to a non-linear growth model, exhibiting a strong correlation with the reciprocal of the particle size reduction rate. The SBET values of pristine illite and WBM-A2, WBM-A6, and WBM-A10 were calculated using the BET method and were 6.51 ± 0.26 m2/g, 12.07 ± 0.48 m2/g, 20.25 ± 0.61 m2/g, and 22.54 ± 0.45 m2/g, respectively, demonstrating a substantial increase as milling progressed. The SBET increased gradually as particle size decreased. This systematic increase in specific surface area directly reflects the geometric transition toward a higher surface-to-volume ratio as the particle size decreases, establishing a definitive functional link between mechanical energy input and surface structure evolution. Since adsorption behavior is strongly governed by the accessible external surface area of layered silicates, the observed increase directly reflects the particle surface enhanced by WBM [48].

3.3.2. Moisture Evaporation and Retention Behavior

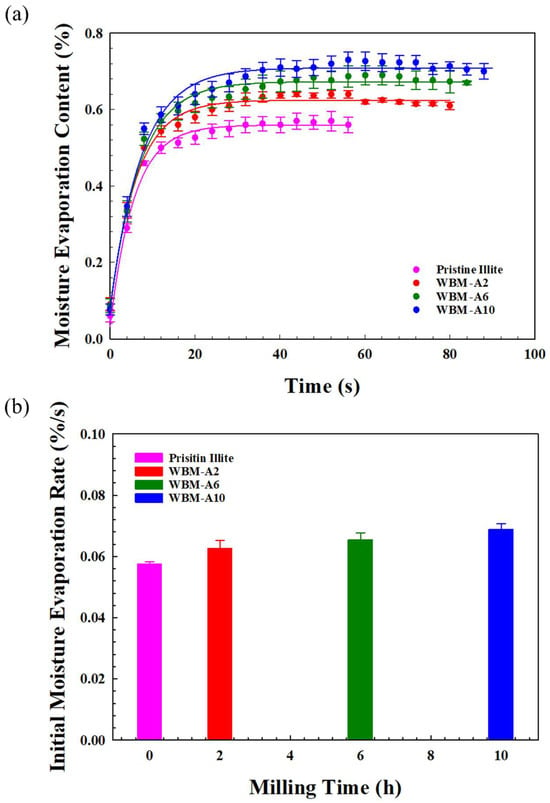

As the wet ball-milling process progressively reduced particle size and increased the surface area of illite, the moisture-evaporation and retention behavior also changed significantly, reflecting the combined effects of surface exposure and diffusion-limited moisture transport within the milled illite particles. Figure 9a and Figure 9b show the moisture evaporation content (MEC) as a function of time and the initial evaporation rate (RiM) values for pristine illite particles and the illite particles ball-milled in acetone for 2, 6, and 10 h (WBM-A2, WBM-A6, and WBM-A10), respectively. To quantitatively elucidate the evaporation dynamics and establish a definitive mathematical dependency on milling duration, the MEC profiles in Figure 9a were fitted using a first-order kinetic model (3-parameter exponential rise function): MEC(t) = yi + c · (1 − e−dt). In this framework, yi represents the baseline offset, c denotes the asymptotic evaporation capacity (maximum moisture content), and d serves as the evaporation rate constant. This model explicitly captures both the early-stage evaporation kinetics and the long-term moisture retention behavior within a unified mathematical framework. The fitted kinetic parameters (yi, c, and d) obtained from this model are summarized in Table 5, along with the corresponding coefficients of determination (r2), providing a quantitative comparison of moisture-evaporation behavior as a function of milling time. For all samples, the MEC initially increased sharply, and their RiM were 0.058 ± 0.001%, 0.063 ± 0.003%, 0.065 ± 0.002%, and 0.069 ± 0.002%, respectively, indicating a gradual increase with milling time. The faster initial evaporation observed for samples with longer milling times reflects their reduced particle size and enlarged SBET, both of which accelerate early-stage moisture release. The high statistical correlation (r2 > 0.99 for all systems) confirms that moisture release follows a well-defined kinetic pathway, governed by the structural evolution of the illite aggregates. In addition, the maximum moisture content, represented by the evaporation capacity parameter (c), increased steadily with the values of 0.57 ± 0.002%/s, 0.64 ± 0.01%/s, 0.70 ± 0.01%/s, and 0.73 ± 0.03%/s for pristine illite particles, WBM-A2, WBM-A6, and WBM-A10, respectively. This monotonic increase in the c values directly correlates with the increased SBET, indicating enhanced water adsorption capacity associated with expanded external surfaces and newly formed mesoporous structures. Meanwhile, the evaporation rate constant (d) reflects the accelerated mass transfer through the newly developed mesoporous network. Despite exhibiting higher RiM, the samples showed higher maximum moisture content and longer retention times. In particular, WBM-A10 retained its highest maximum moisture content for the longest period. This behavior is attributed to the greater moisture adsorption capacity associated with reduced particle size and enlarged surface area [49].

Figure 9.

(a) Moisture evaporation content (MEC) as a function of time for pristine and the illite particles (WBM-A2, WBM-A6, and WBM-A10) milled in acetone for 2, 6, and 10 h, fitted with exponential rise function, y = yi + c · (1 − e−dx), where yi represents the baseline moisture content at t = 0, c means the maximum asymptotic evaporation level (evaporation capacity), and d is evaporation rate constant (r2 > 0.99 for all systems), and (b) initial moisture evaporation rate (RiM) calculated from the early-stage kinetic slopes.

Table 5.

Kinetic parameters of the moisture evaporation content (MEC) of pristine illite, WBM-A2, WBM-A6, and WBM-A10, fitted with the 3-parameter exponential rise model.

The progressive fragmentation of illite particles during WBM produced finer particles that pack more densely, thereby increasing the tortuosity of internal diffusion pathways and imposing diffusion limitations for internally adsorbed water. Therefore, all samples exhibited a dual moisture-evaporation mechanism: rapid evaporation of loosely bound surface moisture in the initial stage, followed by slow evaporation driven by prolonged retention of internally adsorbed moisture due to diffusion-limited release. In particular, WBM-A10 showed the most drastic evaporation of surface-bound moisture and the longest retention of internal moisture, clearly demonstrating that particle-size reduction simultaneously accelerates surface evaporation while enhancing long-term moisture retention through diffusion-limited transport. These results highlight the pronounced effects of particle size reduction on moisture evaporation and retention behavior in illite particles.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated how the milling medium, rather than milling time alone, governed the particle size, surface chemistry, and moisture–interaction behavior of illite particles using wet ball milling (WBM). Although prolonged milling induced progressive fragmentation of illite particles across all media, particle-size reduction and uniformity varied substantially depending on the physicochemical properties of the selected milling medium, including viscosity, surface tension, and interfacial chemistry and interactions. By correlating these parameters with fragmentation kinetics and surface evolution, this work establishes a physicochemical-property-based framework that provides mechanistic insights beyond simple phenomenological observations. Five different media, including acetone, ethanol, water, aqueous NaCl solution, and aqueous phosphoric acid solution, were used in this study. Organic solvents, acetone and ethanol, exhibited markedly superior milling performance. Acetone, characterized by the lowest viscosity, low surface tension, and minimal interfacial interactions with illite, exhibited the most effective performance in producing the finest and most uniformly dispersed particles (~700 nm) after 10 h of milling. In contrast, aqueous systems, water, NaCl solution, and phosphoric acid solution, showed significantly lower milling efficiency. In particular, phosphoric acid solution displayed strong hydrogen bonding, electrical double-layer compression, and surface protonation or phosphate complexation via interactions with illite particles, all of which promoted severe particle agglomeration and substantially reduced fragmentation efficiency. FT-IR and XRD confirmed that the fundamental aluminosilicate lattice of illite was preserved after milling using various media, although phosphoric acid induced distinct surface-specific chemical modifications, including broadened O–H vibrational bands and phosphate-related complexation. Acetone-milled particles exhibited marked increases in specific surface area and mesoporosity, displaying Type IV isotherms with H3 hysteresis loops. These surface changes significantly altered moisture behavior: smaller particles with larger accessible surface area exhibited more rapid initial moisture evaporation, but retained higher internal moisture due to increased adsorption capacity and extended diffusion pathways.

Overall, this work demonstrates that the physicochemical properties of the milling medium serve as key factors in regulating slurry hydrodynamics, collision efficiency, energy transfer, and dispersion stability during wet ball milling, thereby governing particle fragmentation, surface morphology evolution, and moisture-retention behavior. Beyond simple empirical optimization, these findings provide a mechanistic basis by elucidating how medium-dependent viscosity, surface tension, and particle–medium interfacial chemistry collectively influence slurry hydrodynamics and dispersion behavior. While aqueous systems remain the industrial standard, the insights gained from this study offer a rational perspective for improving medium selection to produce fine, uniform, and functionality-enhanced illite particles and to address the limitations of conventional aqueous milling. As a result, this work expands the practical use of finely milled illite in cosmetics, agriculture, foods, and other bio-relevant fields where controlled particle size and surface activity are essential performance parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.L. and N.L.; methodology, J.H.L. and N.L.; software, N.L.; validation, N.L., H.L. and J.H.L.; formal analysis, N.L., H.L. and J.H.L.; investigation, N.L., H.L. and J.H.L.; data curation, N.L.; writing— original draft preparation, N.L.; writing—review and editing, J.H.L., H.L. and Y.J.; visualization, N.L., H.L., Y.J. and J.H.L.; supervision, J.H.L.; project administration, J.H.L.; funding acquisition, J.H.L. All authors edited the manuscript and revised the final submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2023R1A2C1007971). This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Chungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea (No. 2025-RISE-11-003-03).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Inhye Lee, Yeryeong Lee, and Hwa-In Lee for their assistance with this research conducted in the Functional Materials, Formulation, and Delivery (FMFD) Laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moore, D.M.; Reynolds, R.C., Jr. X-Ray Diffraction and the Identification and Analysis of Clay Minerals, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 34–181. [Google Scholar]

- Guggenheim, S.; Martin, R.T. Definition of Clay and Clay Mineral: Joint Report of the Aipea Nomenclature and CMS Nomenclature Committees. Clays Clay Miner. 1995, 43, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, A.; Velde, B. Solid solutions in I/S mixed-layer minerals and illite. Am. Mineral. 1989, 74, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Środoń, J.; Zeelmaekers, E.; Derkowski, A. The charge of component layers of illite-smectite in bentonites and the nature of end-member illite. Clays Clay Miner. 2009, 57, 649–671. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Choung, S.; Shin, W.; Han, W.S.; Chon, C.-M. A Batch Experiment of Cesium Uptake Using Illitic Clays with Different Degrees of Crystallinity. Water 2021, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, D.M.; Lee, H.; Chang, J.H. Enhancement of Oxygen and Moisture Permeability with Illite-Containing Polyethylene Film. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2019, 56, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Yan, S. Effect of 3-Mercaptopropyltriethoxysilane Modified Illite on the Reinforcement of SBR. Materials 2022, 15, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavitskaya, A.; Batasheva, S.; Vinokurov, V.; Fakhrullina, G.; Sangarov, V.; Lvov, Y.; Fakhrullin, R. Antimicrobial Applications of Clay Nanotube-Based Composites. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, J.D.D.; Bertolino, S.R.A.; Cuffini, S.L.; Ducart, D.F.; Bretzke, P.E.; Leonardi, G.R. Clay minerals: Properties and applications to dermocosmetic products and perspectives of natural raw materials for therapeutic purposes-A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 534, 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, M.-C.; Im, D.-Y.; Park, H.-S.; Dhungana, S.K.; Kim, I.-D.; Shin, D.-H. Seed Treatment with Illite Enhanced Yield and Nutritional Value of Soybean Sprouts. Molecules 2022, 27, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgelane, I.; Sevjakova, V.; Dzene, L. Influence on illitic clay addition on the stability of sunflower oil in water emulsion. Colloids Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 529, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Muniyappan, M.; Shanmugam, S.; Kim, I.H. Effects of dietary supplementation of illite on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and meat-carcass grade quality of growing-finishing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2024, 66, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Liu, F.; Hu, L.; Reed, A.H.; Furukawa, Y.; Zhang, G. Evaluation of the particle sizes of four clay minerals. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 135, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, F.; Cecila, J.A.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, J.L.; Gomes, C.S.F. Particle-size reduction of dickite by ultrasound treatments: Effect on the structure, shape and particle-size distribution. Appl. Clay Sci. 2007, 35, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Horváth, E.; Makó, É.; Kristóf, J.; Cseh, T. The effect of mechanochemical activation upon the intercalation of a high-defect kaolinite with formamide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 265, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriche, L.; Chamayou, A.; Calvet, R.; Hamdi, B.; Balard, H. Influence of different dry milling processes on the properties of an attapulgite clay, contribution of inverse gas chromatography. Powder Technol. 2014, 254, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Mio, H.; Kano, J.; Saito, F. Ball mill simulation in wet grinding using a tumbling mill and its correlation to grinding rate. Powder Technol. 2004, 143–144, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Mitchell, R.J.; Lee, J.H. Environmentally friendly pretreatment of plant biomass by planetary and attrition milling. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 144, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, F.; Xue, B.; Sun, M.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X. Wet grinding of montmorillonite and its effect on the properties of mesoporous montmorillonite. Colloids Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2010, 356, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, W.; Hu, Y.; Du, C.; Tang, A. Effect of Mechanochemical Processing on Illite Particles. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2005, 22, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janot, R.; Guerard, D. Ball-milling in liquid media: Applications to the preparation of anodic materials for lithium-ion batteries. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2005, 50, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, P.; Knieke, C.; Mackovic, M.; Frank, G.; Hartmaier, A.; Göken, M.; Peukert, W. Microstructural evolution during deformation of tin dioxide nanoparticles in a comminution process. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 3060–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Sohn, Y.; Sung, H.G.; Hyun, H.S.; Shin, W.G. Physicochemical properties of ball milled boron particles: Dry vs. wet ball milling process. Powder Technol. 2015, 269, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, K.; Sirkecioğlu, A.; Tatlıer, M.; Savaşçı, Ö.T.; Erdem-Şenatalar, A. Wet ball milling of zeolite HY. Powder Technol. 2004, 142, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriche, L.; Calvet, R.; Chamayou, A.; Hamdi, B. Influence of different wet milling on the properties of an attapulgite clay, contribution of inverse gas chromatography. Powder Technol. 2021, 378, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jin, S.-H.; Raju, K.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.-K. Analysis of individual and interaction effects of processing parameters on wet grinding performance in ball milling of alumina ceramics using statistical methods. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 31202–31213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Kuo, C.L.; Wen, S.-B.; Lin, C.-P. Changes of organo-montmorillonite by ball-milling in water and kerosene. Appl. Clay Sci. 2007, 36, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papirer, E.; Roland, P. Grinding of Chrysotile in Hydrocarbons, Alcohol, and Water. Clays Clay Miner. 1981, 29, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papirer, E.; Eckhardt, A.; Muller, F.; Yvon, J. Grinding of muscovite: Influence of the grinding medium. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25, 5109–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Q. Effects of Typical Solvents on the Structural Integrity and Properties of Activated Kaolinite by Wet Ball Milling. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeis, S.; Schmidt, J.; Peukert, W. Mechanochemical aspects in wet stirred media milling. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2016, 156, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semião, V.; Andrade, P.; da Graça Carvalho, M. Spray characterization: Numerical prediction of Sauter mean diameter and droplet size distribution. Fuel 1996, 75, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemball, C.; Schreiner, G.D.L. The Determination of Heats of Adsorption by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller Single Isotherm Method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 5605–5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, H.K. The cross-sectional areas of molecules adsorbed on solid surfaces. J. Colloid Sci. 1949, 4, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Experimental investigation of gas seepage characteristics in coal seams under gas-water-stress function. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Lee, S.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, J.-B. Effect of ball size and powder loading on the milling efficiency of a laboratory-scale wet ball mill. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 8963–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Q.; Yu, J.; Lin, T.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, H. Optimizing the size distribution of zinc borosilicate glass powder by organic solvent and tetradecylphosphonic based wet milling. Mater. Lett. 2023, 349, 134745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Yu, X.; Yu, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, S.; Yu, C. Synthesis of illite/iron nanoparticles and their application as an adsorbent of lead ions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 29449–29459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y. Highly efficient preferential adsorption of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution using sodium lignosulfonate modified illite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 26191–26207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Puebla, R.A.; dos Santos, D.S., Jr.; Blanco, C.; Echeverria, J.C.; Garrido, J.J. Particle and surface characterization of a natural illite and study of its copper retention. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 285, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Churchman, G.J.; Yin, K.; Li, R.; Li, Z. Randomly interstratified illite–vermiculite from weathering of illite in red earth sediments in Xuancheng, southeastern China. Geoderma 2014, 214–215, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, H.S.; Sung, D.; Choi, W.I. A Novel Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Stabilized Illite Microparticle with Enhanced Antioxidant and Antibacterial Effect. Polymers 2021, 13, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, X.; Liu, S.; Dai, C.; Zhong, G.; Duan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Makninov, A.N.; Araruna Júnior, J.T.A.; Tu, Y.; Leong, K.H. Effects of EDTA on adsorption of Cd(II) and Pb(II) by soil minerals in low-permeability layers: Batch experiments and microscopic characterization. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 41623–41638. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-S.; Choi, H.-J. Design of a Novel Sericite-Phosphoric Acid Framework for Enhancement of Pb(II) Adsorption. Molecules 2023, 28, 7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, N. In situ high temperature X-ray diffraction study of illite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 146, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bij, H.E.; Cicmil, D.; Wang, J.; Meirer, F.; de Groot, F.M.F.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Aluminum-Phosphate Binder Formation in Zeolites as Probed with X-ray Absorption Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17774–17787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tian, G.; Zong, L.; Zhou, Y.; Kang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, A. From illite/smectite clay to mesoporous silicate adsorbent for efficient removal of chlortetracycline from water. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 51, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, J.-J.; Wang, X.-G.; Huang, H. Particle Size Effect and Temperature Effect on the Pore Structure of Low-Rank Coal. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 5865–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Krooss, B.M. Influence of Grain Size and Moisture Content on the High-Pressure Methane Sorption Capacity of Kimmeridge Clay. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 11548–11557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.