Abstract

This study presents the synthesis and characterization of novel kaolinite niobium and kaolinite titanium niobium nanocomposites and their application as heterogeneous photocatalysts. Utilizing a hydrolytic sol–gel route, we combined kaolinite with isopropyl alcohol, acetic acid, titanium (IV) isopropoxide, and ammonium niobium oxalate, followed by heat treatment at 400, 700, and 1000 °C. X-ray diffraction confirmed the retention of kaolinite’s characteristic reflections, with basal spacings indicating the presence of semiconductors on the external surfaces and edges. Heating treatment not allowing the crystallization of anatase until 1000 °C reveals that Nb5+ could inhibit the transition to titanium crystalline phases (anatase and rutile). The bandgap energies decreased with clay mineral support, averaging 2.50 eV, and absorbing up to 650 nm. The model reaction of terephthalic acid hydroxylation accomplished by photoluminescence spectroscopy demonstrated that KaolTiNb400 presented a higher rate of *OH production, achieving 591 mmol L−1 min−1 compared to pure KaolNb400 173 mmol L−1 min−1. Photodegradation studies revealed significant photocatalytic activity, with the KaolTiNb400 nanocomposite achieving the highest efficiency, demonstrating 90% removal of methylene blue (combining adsorption and degradation) after 24 h of UV light irradiation. These materials also exhibited promising results for the degradation of the antibiotics Triaxon® (40%) and Loratadine (8%), highlighting their potential for organic pollutants’ removal. In both cases the presence of byproducts is detected.

1. Introduction

Pharmaceutically active compounds, personal care products (PCP), pesticides, synthetic or natural hormones, and chemical industry residues are continually discharged into the environment from diverse sources. This can lead to toxicity and other adverse effects on ecosystems and, consequently, living organisms [1,2]. These substances, detected in aquatic ecosystems and wastewater at low concentrations (ng L−1 to μg L−1), are referred to as contaminants of emerging concern (CECs). Conventional secondary and tertiary treatments, such as filtration and disinfection, are largely ineffective in removing most CECs from urban wastewater. Consequently, effluents from wastewater treatment plants are the primary pathways through which CECs enter the environment [3,4,5].

There is additional concern for both human health and the environment regarding the release of CECs into soils and their uptake by crops during wastewater reuse practices. The presence of CECs in wastewater discharged into the environment is not yet regulated or easily quantified, including in the reclaimed water used in agriculture. However, some European countries have started to monitor these substances, making it a hotly discussed topic among scientists, policymakers, and other stakeholders [6,7].

In this context, Triaxon®, a medication containing disodium ceftriaxone, is an antibiotic widely used for treating infections due to its broad-spectrum efficacy. It belongs to the cephalosporin family of antibiotics, primarily used in the treatment of bacterial infections [8].

Nanocomposites are increasingly important products of nanotechnology, mainly due to their ability to combine the unique properties of conventional components. The concept of integrating organic or inorganic matrices with metallic nanoparticles has become a crucial aspect of materials science. As a result of advancements in materials chemistry, various types of nanostructured inorganic solids have been synthesized to enhance key properties, such as optical, magnetic, sensing, catalytic, and photocatalytic characteristics. Significant efforts have been dedicated to developing sustainable and environmentally friendly methods for their preparation, characterization, and application [9].

Clay minerals are composed of very small particles (<2 µm) of hydrated aluminosilicates, with other elements present in distinct phases. Due to their unique structure, these silicates are more accurately called phyllosilicates, since their structure comprises stacked sheets formed by tetrahedral (T) units of silicon dioxide (SiO2) and octahedral (O) units of aluminum oxi-hydroxide (Al(OH)3). The stacking of these tetrahedral and octahedral sheets yields lamellae. The manner in which these sheets are stacked determines the different types of clay minerals with regular and irregular sequences [10].

Kaolinite is a clay mineral derived from kaolin, a mineral composed of a series of hydrated silicates, with the main components being kaolinite and halloysite. Kaolin has a fine particle size and contains other substances classified as impurities, such as quartz, mica, and feldspar grains, as well as titanium oxides. The minimum formula for São Simão kaolinite, used in this study, was previously reported by De Faria et al. (2009) [11], and is represented by Si2.0Al1.96Fe0.03Mg0.01K0.02Ti0.03O7.06, with a characteristic basal spacing of 7.14 Å. This kaolinite has a 1:1 (TO) structure, formed by the combination of tetrahedral SiO4 (T) and octahedral Al(OH)3 (O) sheets [12].

São Simão is a small municipality located in the interior of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. It has one of the most important kaolinitic deposits in the country. These “ball clays” are being used by our research group in various projects, with applications ranging from catalysis and adsorption to sensing. Recently, clay minerals have gained significant attention as supports for different semiconductor-based photocatalysts, such as TiO2 [13], ZnO [14], and ZrO [15]. The use of semiconductors supported on lamellar solids aims to promote the dispersion of the active phase on an inert solid with high surface area, along with a 2D, organized lamellar structure, chemical stability, high availability of active sites, and the presence of isomorphic substitutes that can exhibit some photocatalytic activity, such as MnO, TiO2, and Fe2O3, while also facilitating the recyclability of the photocatalyst.

TiO2-based inorganic photocatalysts have been extensively investigated for environmental applications such as air and water treatment, including deodorization, due to their strong oxidizing power, high photocatalytic activity, self-cleaning function, and bactericidal and detoxifying properties [16]. The isomorphic substitution of Nb5+ (0.640 Å) for Ti4+ (0.605 Å) induces distortion in the titanium structure and promotes a charge imbalance due to the smaller ionic size of Ti4+ and the charge deficiency, introducing shallow donor levels below the conduction band edge of TiO2. It is important to note that Nb5+ doping can create cation vacancies or lead to the reduction of Ti4+ into Ti3+. The electronic transition from the valence band to these donor levels can be excited by visible light, enabling Nb-doped TiO2 photocatalysts to respond to visible light [17].

Brazil has been the largest producer of niobium (Nb2O5) since 1980. This substance is commonly used to reduce corrosion in alloys. Recently, numerous studies have been conducted to expand the applications of Nb2O5-based materials as catalysts, luminescent materials, adsorbents, photonic materials, and antibacterial agents [18]. Among these, Triaxon®, a drug composed of sodium ceftriaxone, is a widely used antibiotic for treating infections due to its broad spectrum of activity. It belongs to the family of antibiotics known as cephalosporins, which contain semi-synthetic β-lactams in their structure. β-lactams typically undergo rapid decomposition due to the hydrolytic opening of the lactam ring, and their byproducts and unmetabolized compounds pose significant environmental problems due to their high stability and persistence in natural aquatic habitats [19].

The construction of a heterojunction involves the relative matching of the Electrons Fermi (EFs) that is the highest energy level that an electron can occupy, at 273.15 K, and band structures of two photocatalysts, mainly affecting the photocatalytic performance of the heterojunction. These aspects strongly influence the electron transport and energy-level jump between two semiconductors upon contact and illumination, thereby resulting in different carrier mobility mechanisms. In turn, the EF and band structure of photocatalysts are influenced by their composition, atomic valence, and crystal structure. The photocatalytic mechanism of each heterojunction has not been fully elaborated. For example, Schottky junctions and p–n junctions have multiple mechanisms rather than just one that can be applied to kaolinite/titanium/niobium oxide [20].

The treatment of contaminated water is a major challenge to society. Various methods, such as filtration [21], chemical oxidation [22], adsorption [23], and biological treatments [24], have been studied for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Among these, adsorption is widely studied due to its simplicity and high efficiency. However, a drawback of adsorption technology is that pollutants are merely transferred from the wastewater to the adsorbents, resulting in secondary pollution due to the disposal of the used adsorbents. In contrast, heterogeneous photocatalysis can often promote complete degradation, known as mineralization, into less toxic compounds such as carbonate, nitrate, phosphate, and sulphate [25].

The pervasive contamination of water resources by dyes has emerged as a critical global challenge, occupying a prominent position in environmental sustainability agendas [26,27]. The escalating discharge of these synthetic organic pollutants into aquatic ecosystems poses severe and often irreversible harm to aquatic biota, with cascading effects throughout the food web, ultimately impacting human health [28]. Reactive dyes, in particular, are increasingly used in diverse industrial sectors [29]. Among the myriads of industrial dyes, methylene blue (MB), a phenothiazine derivative widely employed in textile dyeing, stands out as a contaminant and model compound frequently used to evaluate the efficacy of novel adsorbent materials [30]. While MB offers advantages in industrial applications, its toxicity is concentration dependent, and concerns exist regarding its potential carcinogenicity [31]. Traditional wastewater treatment methods, including adsorption and ozonation, have been employed to mitigate dye pollution. However, inherent limitations often hinder the complete removal of these persistent pollutants from wastewater effluents [32]. The ongoing research and development of more efficient and sustainable technologies for dye removal are therefore of paramount importance.

Loratadine (LOR) and its active metabolite, desLoratadine (DES), are a significant class of second-generation antihistamines widely administered to humans. Consequently, these compounds are continuously introduced into wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) via excretion, leading to their ubiquitous presence as residues and transformation products (TPs) in surface water [33]. Pharmacokinetic studies indicate that substantial portions of the ingested loratadine dose, approximately 40% and 42% in urine and feces, respectively, are excreted unchanged [34]. Environmental monitoring has confirmed the occurrence of LOR in surface waters across Europe, with concentrations reported in the range of 3.96–17.1 ng L−1 in Spanish rivers [35]. Furthermore, both LOR and DES have been detected in wastewater effluents globally, with maximum concentrations reaching 58.5 ng L−1 for LOR and 81.0 ng L−1 for DES in Europe, North America, and the Asia–Pacific region [33]. The persistent detection of these antihistamines in aquatic environments, even at low concentrations, raises concerns about potential chronic effects on non-target organisms and the development of resistance in aquatic bacteria.

Ceftriaxone (CTX), a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, is another critical pharmaceutical of environmental concern due to its widespread use in treating various bacterial infections. Its mechanism of action involves inhibiting bacterial cell wall mucopeptide synthesis [36,37]. Common side effects include pain, swelling, or redness at the injection site, diarrhea, which can sometimes be severe and persistent, rash or other allergic reactions, or abnormal liver function tests.

Changes in blood cell counts, such as an increase in eosinophils (a type of white blood cell) or a decrease in white blood cells or platelets, have been reported. It has been approved by regulatory agencies like the FDA for intramuscular or intravenous administration at significant daily doses (up to 2–4 g for extended periods). The global consumption of antibiotics, including CTX, is estimated to be substantial, reaching hundreds of thousands of tons annually [38]. While studies have reported the presence of CTX in influent wastewater at high concentrations (e.g., 334 µg L−1), its absence in effluent samples suggests potential degradation or removal within WWTPs [39]. However, the high influent concentrations and the potential for incomplete removal or the formation of transformation products require further investigation into the environmental fate and potential ecological impacts of this crucial antibiotic. The release of even trace amounts of antibiotics or antihistamines into the environment is a major driver of antibiotic resistance, a critical global health challenge. It is aligned with sustainable development goals (SDGs), principally SDG 6 with specific target 6.3, which aims to improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing the release of hazardous chemicals and materials, promoting the reduction in water pollution by 2030. This goal aims to protect human health and the quality of ecosystems.

Therefore, the objective of this work was to synthesize, characterize, and apply a new material based on kaolinite/titanium doped with niobium ions, prepared by a hydrolytic sol–gel method, for the removal of heterogeneous photocatalysts, including evaluating its potential use in methylene blue degradation and terephthalic acid hydroxylation of the pharmaceuticals Loratadine and Triaxon®.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The kaolinite used in this study was supplied by the mining company Darcy R. O Silva e CIA, obtained from clay deposits located in the city of São Simão, a town in the interior of São Paulo state, Brazil. The removal of impurities and the subsequent purification of kaolinite was achieved through the dispersion and decantation of the natural clay in distilled water, based on Stokes’ Law. Ammoniacal niobium oxalate was supplied by CBMM and used as received, while titanium (IV) isopropoxide was obtained from Merck, isopropanol was purchased from Dinâmica, and acetic acid was supplied by Dinâmica.

2.2. Synthesis of Kaolinite–Titanium–Nb Photocatalysts

The synthesis of the nanocomposites was based on the work of Barbosa et al. (2015) [40]. For this process, 1 g of kaolinite, 20 mL of isopropanol, 0.1 mL of acetic acid, 0.2 mL of titanium (IV) isopropoxide, and ammonium niobium oxalate (NH4NbO(C2O4)2) gently conceded by CBMM at 5 mol% relative to titanium were kept under constant mechanical stirring for 24 h. The resulting suspension was then centrifuged and dried in an oven at 80 °C for 24 h. These materials were designated as Kaol-TiO2-Nb.

The synthesis of the nanocomposite referred to as Kaolinite–Niobium was carried out similarly but without the addition of titanium (IV) isopropoxide, and thus named Kaol-Nb.

The obtained materials were divided into four fractions: one fraction remained untreated while the other three were calcined at 400 °C, 700 °C, or 1000 °C for 24 h in a muffle furnace. The temperatures chosen for thermal treatment were based on the phase transitions of titanium to anatase, rutile, and brookite, respectively, as reported in previous studies [41]. These were named accordingly, with the temperature of calcination added to the names, resulting in Kaol-TiO2-T or Kaol-Nb-T, where T = 400, 700, or 1000, depending on the thermal treatment temperature.

2.3. Photocatalysis Experiments

The photocatalytic reactions involving methylene blue, Triaxon, and Loratadine as substrates were conducted in a sealed chamber containing a 95-watt lamp emitting short-wavelength UV-C radiation with a peak at 253.7 nm and germicidal action. A device that allowed us to accomplish simple and cost-effective photodegradation reactions was utilized. The lamp was surrounded by a quartz tube, which enabled us to use it inside the solution containing the substance to be degraded. An aqueous solution of each substrate with concentrations ranging from 10 mg L−1 to 30 mg L−1. The distance between lamp to each reaction was nearly 5 cm. The influence of exposure time was studied herein (quantified by calibration curves from UV-Vis spectroscopy) and exposed to artificial ultraviolet radiation under constant stirring and placed in a thermostatic bath maintained at 25 ± 1 °C.

Three tests were conducted using methylene blue dye, the antibiotic Triaxon®, and the antihistaminic Loratadine as substrates. For the dye test, 2 mg of each photocatalyst was used for 5 mL of a 10 mg L−1 methylene blue solution, with the results analyzed after 120 min of exposure to ultraviolet radiation. For the Triaxon® test, 2.5 mg of each photocatalyst was used for 5 mL of a 30 mg L−1 Triaxon® solution, with the results analyzed after 60 min. For Loratadine, 2.5 mg of photocatalyst was used with 5 mL of 30 mg L−1 of Loratadine. Both solid photocatalysts were exposed to ultraviolet radiation (λ = 254 nm, P = 95 W) in a chamber-type photoreactor, maintained under constant magnetic stirring at 300 rpm. A control test was also conducted in the absence of ultraviolet radiation to assess the adsorption capacity of the prepared photocatalysts. Before performing spectroscopic measurements, we centrifuged all suspensions and analyzed them using calibration curves for each contaminant (methylene blue, λmax = 665 nm; Triaxon®, λmax = 240 nm; and Loratadine λmax = 225 nm) by UV-Vis molecular absorption spectroscopy. The results were expressed as the percentage removal of each contaminant according to Equation (1).

2.4. Terephthalic Acid Photodegradation: Model to Evaluate the Photoactivity of Kaolinite–Titania–Nb Solids

For the photocatalysis of terephthalic acid (TA), a solution of 0.04 mmol L−1 TA was prepared, and 0.05 g of Kaol–Titanium–Nb was added. The same experiment was performed without the catalyst and after the catalytic photodegradation of Triaxon®. The TA solution and photocatalyst were exposed to artificial UV radiation (λ = 365 nm, P = 96 W) for 1 h under constant magnetic stirring at 300 rpm. The photoreactor used for all photocatalysis runs had dimensions of 150 × 55 × 55 cm (height, width, and length), and was coated with aluminum foil to enhance radiation scattering inside the photoreactor. The solutions were exposed to artificial UV light from a high-pressure mercury vapor fluorescent lamp, attached vertically at a distance of 5 cm from the center of the quartz flask.

2.5. Characterization Techniques

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): XRD analyses were conducted using a Rigaku Miniflex II, (Tokyo, Japan), employing Cu Kα radiation. Diffractograms were obtained in the 2θ range of 2° to 75°, with a step size of 0.04°, and a scan speed of 2° per min.

The thermal analyses were carried out between 25 and 900 °C on a TA Instruments SDT Q600 thermal analyzer, (New Castle, DE, USA), at synthetic air flow of 100 mL/min and heating rate of 10 °C/min. Using alumina crucibles, nearly 10.0 mg of each sample was measured.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): FTIR spectra were recorded at the University of Franca using a Perkin–Elmer 1730 Frontier spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were analyzed in the 400–4000 cm−1 range using diffuse reflectance, mixed with KBr in a 1:100 (w/w) ratio, with KBr as the background. The resolution was set at 0.5 cm−1 with 32 scans per analysis.

Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy (UV-Vis): The solid UV-Vis spectra were obtained with an Ocean Optics spectrometer. Barium sulfate (BaSO4) was employed as standard, and measurement was conducted by using diffuse reflectance, a PX-2 pulsed xenon light source, and an Ocean Optics QE65000 detector (Orlando, FL, USA). Barium sulfate was also used during integration, to study the optical properties of the Kaol-TiO2-Nb and Kaol-Nb materials and to determine the bandgap energy by Tauc Plot.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): SEM images were captured with a Tescan Vega 3 SBH Model EasyProbe (Brno, Czech Republic) at the University of Franca. The samples were dispersed in ethanol, placed on aluminum stubs with colloidal graphite, and coated with a thin gold layer using a Quorum SC7620 sputter coater (Laughton, East Sussex, UK).

Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) and Specific Surface Area (SSA): CEC and SSA were determined using the methylene blue method. A 0.1 mol L−1 methylene blue solution was added dropwise to the sample suspended in an acidic aqueous solution (pH 2.8–3.8) until saturation, indicated by the formation of a halo on the filter paper. The CEC and SSA values were calculated based on the volume of dye solution used at saturation, according to Equations (2) and (3).

where FMB = 7.8043, CEC = cation exchange capacity (mmol per 100.0 g of dry clay), C = concentration of methylene blue (mmol L−1), V = volume of methylene blue (L), and m = mass of dry clay (g).

Point of Zero Charge (pHPZC): The pHPZC was determined by adding 20 mg of the sample to 20 mL of an aqueous solution, with initial pH values ranging from 1 to 12. The final pH was measured after 24 h of constant stirring (300 rpm). A plot of the final pH versus initial pH was used to determine the pHPZC, identified as the pH range where the final pH remained constant, irrespective of the initial pH.

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: The emission spectra of terephthalic acid were recorded at room temperature with a Jobin Yvon SPEX TRIAX 550 Fluorolog 3 spectrofluorometer, (Edison, NJ, USA). The excitation was fixed at 315 nm as a function of irradiation time in the photocatalytic reactor. The fluorescence intensity of 2-hydroxy terephthalic acid with typical emission at 425 nm was monitored in function of illumination time. By using the device’s onboard software, all spectra were corrected for the lamp intensity and sensitivity of the photomultiplier at the monitored wavelength ranges. The emission spectra were recorded with 0.2 nm emission bandpass between 325 and 600 nm.

Chromatographic analyses: Performed using a Shim-pack VP-ODS column (250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 µm; Shimadzu) (Kyoto, Japan) with a flow rate of 1 cm3 min−1 and UV detection at 290 nm for Triaxon®. An isocratic mobile phase system consisting of 0.1% acetic acid in water (solvent A) or acetonitrile (solvent B) was used at 80/20% for 10 min. The column temperature was set at 40 °C, and the injected volume was 10.0 μL.

3. Results and Discussion

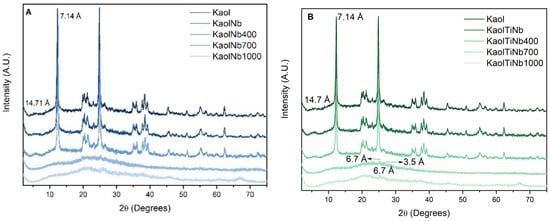

The X-ray diffraction patterns of the kaolinite-based materials are shown in Figure 1. Both the uncalcined and the 400 °C calcined materials exhibit characteristic peaks of kaolinite, similar to those of purified kaolinite. This suggests that there were no significant structural changes after the incorporation of the semiconductors, indicating that these semiconductors are likely present on the surfaces of the materials. Additionally, a low-angle peak at 5.98° 2θ, corresponding to a d001 spacing of 14.71 Å for montmorillonite, suggests contamination in the kaolinite, even after purification.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of (A) KaolNb and (B) KaolTiNb, resulting from the reaction of kaolinite with Nb5+ or Ti4+/Nb5+ ions via sol–gel process. Arrows evidences the peaks of the titania anatase and rutile phases.

For the materials calcined at 700 °C and 1000 °C, kaolinite transitions to metakaolinite and mullite phases. The identification of the semiconductors becomes challenging due to peak overlap [42,43].

An important effect was observed on Kaol-TiO2-Nb solids: the prevention of anatase and rutile crystallization induced by the incorporation of niobium (Nb) into Kaol-TiO2 solids, which presents a significant advancement in the field of photocatalysis. The presence of Nb inhibits the transformation of TiO2 from its amorphous phase to anatase and rutile crystalline phases. This effect is crucial because the crystallization of TiO2 typically reduces the availability of active sites necessary for photocatalytic reactions.

Niobium’s role as a structural modifier helps to maintain the amorphous nature of TiO2 within the composite material. By preventing crystallization, Nb ensures that a greater number of active sites remain exposed and accessible, thereby enhancing the photocatalytic efficiency of the material. The incorporation of Nb likely leads to the formation of Nb-O-Ti bonds, which disrupts the regular TiO2 lattice, inhibiting its ability to reorganize into anatase or rutile structures.

Furthermore, the dispersion of Nb within the Kaol-TiO2 matrix can create more uniform and smaller particle sizes, increasing the surface area available for photocatalytic reactions. This increased surface area, coupled with the preservation of the amorphous phase, facilitates higher photocatalytic activity by providing more active sites for light absorption and subsequent photochemical reactions.

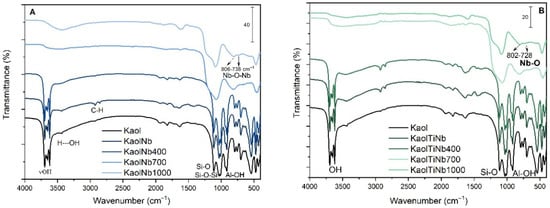

The changes induced by calcination at different temperatures further illustrate the interaction between TiO2/Nb and kaolinite. At 400 °C, the characteristic infrared absorption bands of natural clay minerals, as shown in Figure 2, remain largely unchanged. Kaolinite exhibits typical bands at 3696 and 3666 cm−1, corresponding to inner surface hydroxyl groups (Al-OH), and a band at 3619 cm−1 corresponding to inner hydroxyl groups. Additionally, the band at 1633 cm−1 is associated with δH-O-H, and the Si-O band appears at 1034 cm−1 [44,45,46].

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of (A) KaolNb and (B) KaolTiNb, resulting from the reaction of kaolinite with Nb5+ or Ti4+/Nb5+ ions via sol–gel process.

Upon calcination at 700 °C and 1000 °C, kaolinite transforms into metakaolinite and mullite phases, respectively; this effect is clearly observed in FTIR due the changes observed in the hydroxyl bands and Si-O-Si and Al-OH bands, respectively, at 918 cm−1 and 1100 cm−1. During these transformations, the TiO2 and Nb are covalently bonded with the kaolinite matrix, maintaining the amorphous phase of the semiconductor and preventing the crystallization of anatase and rutile. This stability across a range of calcination temperatures underscores the strong interaction between TiO2/Nb and the kaolinite structure, ensuring that the material’s efficacy as a photocatalyst is preserved.

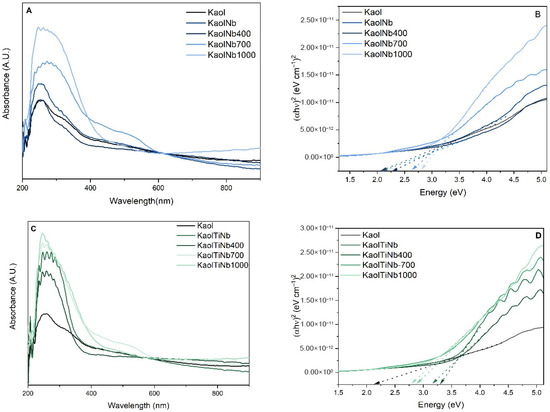

The ultraviolet absorption spectroscopy of solids, as illustrated in Figure 3, revealed a notable increase in the absorbance in clay minerals following the incorporation of semiconductors and the subsequent temperature elevation. This phenomenon is accompanied by a broadening of the absorption band, extending into the visible region. This shift can be attributed to the niobium oxide, which exhibits a maximum absorption at 325 nm [47].

Figure 3.

UV-Vis DRS of (A) KaolNb materials and (C) KaolTiNb materials, and (B,D) bandgap diagram of the materials calculated by Tauc plot. Dashed arrows pointing to the Energy (eV) axis indicate the bandgap energy of each material.

The bandgaps of the semiconductors were determined from the ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra of the solids. The energy required to excite an electron from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) of the semiconductor is directly related to the absorption wavelength. This relationship is described by Equation (4):

where Eg is the optical bandgap (eV), h is Planck’s constant, α is the absorption coefficient, α0 is the energy independent constant, ν is a frequency (Hz), n is the nature of transmission (n = 2 direct bandgap, and n = ½ indirect bandgap.

The bandgap energy of TiO2 is approximately 3.2 eV [48], while that of niobium can range from 0 to 2 eV when combined with titanium [49]. Consequently, the clay mineral supports consistently enhance the bandgap energy in all cases. Furthermore, it is evident that the semiconductor begins to absorb over a much broader range, extending up to 650 nm. This demonstrates the critical role of Nb5+ in developing more efficient semiconductors suitable for milder conditions, such as using sunlight to generate hydroxyl radicals in aqueous media. The values of bandgap vary for Kaol TiNb solids from 3.25 to 2.80 eV to Kaol TiNb heat treated at 400, 700 and 1000 °C respectively. While Kaol Nb solids these values vary from 2.80 to 2.3 eV, for heat treated samples at 400, 700 and 1000 °C. This result corroborates with the hypothesis that Nb creates intermediate levels and could enhance photocatalytical activity.

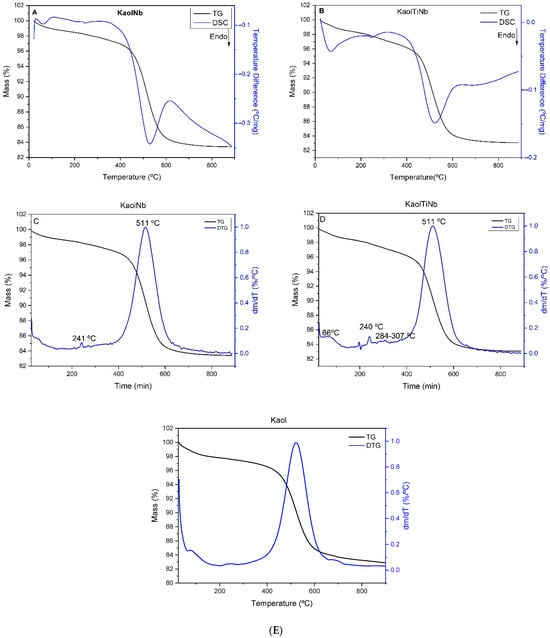

For kaolinite–titanium–niobium based materials, Figure 4 shows the endothermic peaks at 64 °C, corresponding to water loss, and at 520 °C, related to the formation of metakaolinite [41]. Additionally, an endothermic peak was present at around 640 °C.

Figure 4.

TG and DSC curves of KaolNb (A), KaolTiNb (B), DTG curves of Kaol Nb (C), and KaolTiNb (D) and Kaol (E).

The solid KaolTiNb exhibited a primary endothermic effect centered at 64 °C, with a mass loss of 2% attributed to the removal of adsorbed water and possibly small amounts of ethanol used as a solvent. A second mass loss, amounting to 2.5%, occurred between 150 and 400 °C and is ascribed to the decomposition of organic matter, as indicated by the broad exothermic effect observed in the DSC curve near 400 °C. This organic matter likely originated from the acetic acid used in the reaction and/or isopropanol formed during alkoxide hydrolysis, and also due to the ammonium cations and oxalate anions from the niobium salt employed as precursor. Condensation reactions between Ti-OH alkoxide groups and Al-OH or Si-OH groups from the clay were also observed by FTIR, as expected, and could be confirmed by thermal analysis within this temperature range, likely contributing an endothermic effect. Evaluating in detail the hydroxyl region after 400 °C of thermal treatment, the FTIR results show the reduction based on this result of thermal treatment, realized before and after characterization by FTIR (Figure 2B); the condensation could be evidenced as previously discussed [40,41]. Additionally, small but significative events are observed centered at 241 °C, which could be attributed to the decomposition of the ammonium oxalate complex. For the sample containing titanium and niobium, new effects centered at 241 °C, and between 284 and 307 °C, are observed and were attributed to the decomposition of trapped niobium oxalate in smaller sol–gel nanoparticles. The dehydroxylation process of kaolinite was centered at 511 °C, with the associated mass loss decreasing from 13.96% in purified kaolinite to 13% in the solid, as anticipated due to the reduced kaolinite content after alkoxide reaction with hydroxyl groups and due to the coordination of Nb ions into Ti-OH or Al-OH groups. Based on the thermal analysis, the composite composition was estimated to be 4.85% TiO2 and 95.15% kaolinite by mass.

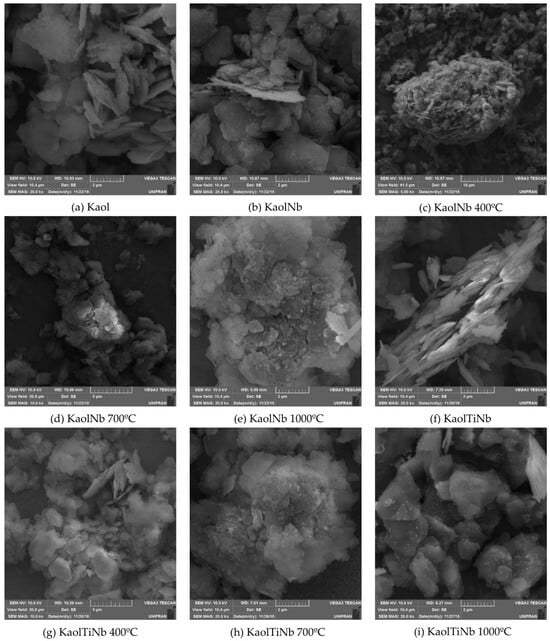

The morphological alterations resulting from functionalization are evident in Figure 5, where the SEM micrographs of the composite are presented. Kaolinite particles typically have a flaky appearance, often forming hexagonal plates and stacks. However, the introduction of titanium alkoxide doped with Nb ions during functionalization promotes the attachment of smaller particles without a defined morphology on the surface of these hexagonal structures, causing the plates to separate. The presence of Nb ions appears to enhance the fragmentation process of these titanium particles, promoting the formation of smaller particles with reduced agglomeration against kaolinite plates. A highly porous structure was observed after the attachment of TiO2 crystallites. The subsequent thermal treatment further intensified this effect, leading to fissures on the crystal surfaces after 700 °C, inducing the aggregation of the smaller, fragmented particles, revealing, at higher temperatures, the reduction in roughness and the migration of titanium/niobium to aluminosilicate surfaces (indicated by smaller points located around the kaolinite plates. Compared to the previous results reported by Barbosa and Mora [40,41], the effect observed was very similar considering that the same type of clay was employed and also that sol–gel process was employed to attach titanium to kaolinite plates.

Figure 5.

SEM images of (a) Kaol (b) KaolNb, (c) KaolNb 400, (d) KaolNb 700, (e) KaolNb 1000, (f) KaolTiNb, (g) KaolTiNb 400, (h) KaolTiNb 700, and (i) KaolTiNb 1000.

Kaolinite, characterized by a low cation exchange capacity (CEC), shown in Table 1, consistently had the most modest results. Generally, an inverse relationship was observed between increasing temperature and rising CEC. This effect was noted in KaolNb1000 and KaolTiNb1000 solids. This result corroborates the XRD and SEM results, showing that metakaolinite is obtained after 700 °C, inducing amorphous phases. The synthetization of clay platelets probably induced the reduction in the solids’ specific surface area.

Table 1.

Cationic exchange capacity (CEC), and total surface area from C.E.C. calculated by the methylene blue method.

It is well established that the pH of a solution can significantly influence the surface charge of a material, the degree of ionization of various pollutants, the dissociation of functional groups at the active sites of the photocatalyst, and the structure of the pollutant molecule itself. Consequently, pH is a critical parameter in the photocatalysis process. When pH < pHPCZ, the surface charge is positive, whereas when pH > pHPCZ, the surface charge is negative. By plotting the final pH against the initial pH, the PCZ (point of zero charge) corresponds to the range where the final pH remains constant, irrespective of the initial pH, indicating that the surface exerts a buffering action [50,51].

The pH point of zero charge are presented in Table 2. The positive charges of the kaolinite surfaces primarily developed at the Al-OH or Ti-OH sites located on the edges and basal OH surfaces, particularly at pH levels below approximately six. This charge development is influenced by electrolyte concentration. For instance, at very low electrolyte concentrations (around 1 mM), where the Debye length is comparable to the thickness of kaolinite particles, these positive charges may not emerge as expected. When TiO2 and Nb ions are present on the kaolinite surface, especially as TiO2-Nb, these charges can be further stabilized or modified depending on the interaction between TiO2 and the kaolinite’s Al-OH sites. On solids such as synthesized KaolTiNb and KaolTiNb-400 the presence of Ti-OH groups induces the generation of more active positive sites compared to pure clay. A pHPZC value of 4.8 was observed in the synthesized sample. However, in the samples heat treated at 400, 700, and 1000 °C, the presence of Si-O, Al-O, and Ti-O on the surface induced the generation of negatively charged surfaces, changing the pHPZC value to be close to 6.5.

Table 2.

pHPZC of KaolNb and KaolTiNb materials.

As the pH of the suspension increases beyond the point of zero charge (pHPZC) of the kaolinite edges, typically around pH 6–6.5, the unique surface charge heterogeneity of kaolinite diminishes. This is due to the deprotonation of Si-OH groups, followed by the Al-OH sites, leading to the development of negative charges on both the edges and basal O faces. In the presence of TiO2 and TiO2-Nb, these deprotonation processes can be affected, potentially altering the overall surface charge distribution. The addition of Nb ions, in particular, could introduce additional negative charges or stabilize smaller particles, thereby reducing agglomeration and enhancing the surface reactivity of the kaolinite–TiO2 composite. This complex interplay of pH, surface charge, and the presence of TiO2 and TiO2-Nb illustrates the nuanced behavior of modified kaolinite in various chemical environments.

The materials studied exhibited a higher pHPCZ, even in the presence of titanium, due to the inclusion of niobium, bringing them closer to neutral pH. This is in contrast with those reported in the literature [40,51], which contain only titanium on kaolinite or silicon oxide, and tend to be acidic.

Understanding the charge recombination process of a semiconductor is crucial because it significantly influences the photodegradation properties and photocatalyst performance. Photoluminescence (PL) is a suitable tool to study the efficiency of charge carrier trapping, migration and transfer, and to understand the fate of electron–hole pairs in semiconductor particles, because PL emissions result from the recombination of free carriers. The TiO2 will absorb the incident photons with sufficient energy equal to or higher than the bandgap energy, which will produce photoinduced charge carriers (h+…e−) [52,53].

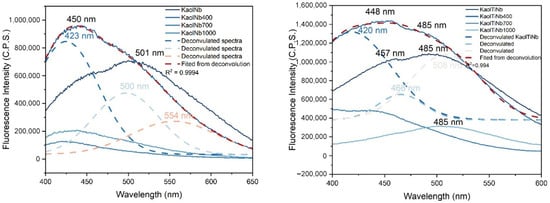

In this context, the photoluminescence spectrum of the KaolTiNb and KaolTi materials measured at an excitation wavelength of 270 nm is shown in Figure 6. Both samples (uncalcined KaolNb and KaolTiNb) had higher emission bands at 450 nm and 485 nm, attributed to kaolinite emission. These broadened bands could be deconvoluted, resulting in three bands at 370 nm. A UV emission band is typical of mineral phases containing SiO4 tetrahedra (quartz and silicates), and may be associated with structural features such as Schottky defects, Frenkel defects, dislocations, planar defects, etc., as previously described by [54]. The second maximum peak at 425 nm is an emission (common to several aluminosilicates with different chemical compositions and variable Al/Si ordering) that can be attributed to the dehydroxylation processes formed by the presence of a hole–oxygen ion adjacent to two Al ions (Al-O-Al). The 464 nm band can be assigned to radiation-induced defects (O−). These broadened bands without deconvolution were previously reported by us under excitation at 250 nm [55]. Additionally, the spectra of KaolNb and KaolTiNb revealed that both samples were similar, according to Figure 6, with two emission peaks centered at 423 and 501 nm for KaolNb and at 448 and 485 nm for KaolTiNb, indicating that recombination occurs through a multiphonon process between states located in the bandgap of the material, which results in broadband emission [56,57].

Figure 6.

Photoluminescence spectra measured with 270 nm excitation at wavelengths from 400 to 600 nm, experiment condition slits 2/2, and integration time 0.1 s. filter employed, lower than 250 nm, employed in excitation entry lamp. Deconvoluted curves for Kaol-TiNb and KaolNb are shown by dashed lines.

Overall, we observed low values of photoluminescence emissions, principally in samples heat treated at 700 and 1000 °C, indicating that the recombination of the photo-generated electron–hole pairs was inhibited. The separation efficiency of photo-excited electron–hole pairs is enhanced, leading to improved photocatalytic properties. This has been observed before for Nb5+ incorporation into kaolinite–TiO2 nanocomposites [56,58], mainly KaolTiNb-400, which maintain the layered structure of kaolinite and induce the reduction in anatase crystallization from TiO2. This separation efficiency might also have been associated with the greater presence of defects after the Nb5+ ions were incorporated in the TiO2 matrix, drastically reducing the transitions of anatase, rutile, and brookite.

3.1. Photocatalytical Applications

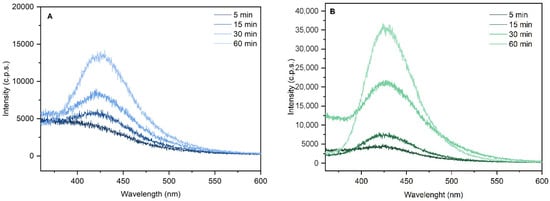

Terephthalic acid (TA) serves as an effective probe molecule to detect hydroxyl radicals (•OH) generated during photocatalytic processes. Its reaction with •OH results in the formation of 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid (2-HTA), a highly fluorescent compound. The increase in fluorescence emission intensity at 425 nm, measured by photoluminescence spectroscopy, directly indicates the enhanced production of •OH [59,60]. Figure 7 illustrates the mechanism of hydroxyl radical detection via the photocatalytic hydroxylation of TA.

Figure 7.

Emission spectra with excitation at 325 nm of 2-hidroxyterphtalyc acid resulting from hydroxylation reaction of terephthalic acid using KaolNb400 (A) and KaolTiNb400 (B) as photocatalyst.

Quantifying •OH is crucial to evaluate the activity and efficiency of photocatalysts, since these radicals are the primary agents responsible for photocatalytic oxidation reactions [61]. In this study, we investigated the photocatalytic activity of Kaol-TiO2-400 for the photohydroxylation of TA under UV-C irradiation. The results are presented in Figure 7.

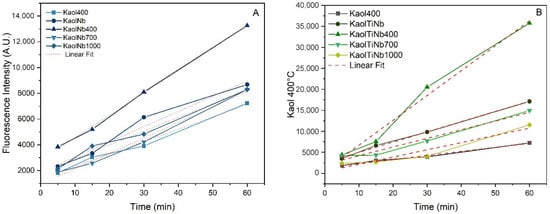

As observed in Figure 8, the fluorescence intensity of 2-HTA increased with the irradiation time of the TA solution and the photocatalyst under UV-C radiation (254 nm), indicating an increase in •OH production.

Figure 8.

Fluorescence intensity against time resulting from emission at 425 nm band of 2-hidroxyterphtalyc acid resulting from the hydroxylation reaction of terephthalic acid using KaolNb400 (A) and KaolTiNb400 (B) as photocatalyst.

Table 3 shows a linear relationship between fluorescence intensity and irradiation time, indicating that the amount of •OH generated on the photocatalyst surfaces was directly proportional to the irradiation time during the photocatalytic process. Some differences occurred in the slopes during photodegradation, reinforcing that heat treatment and the presence of Nb5+ ions drastically influenced the •OH generation. However, it is important to note that the catalytic activity of KaolTiNb400 was higher than that of KaolTiNb, evidencing a rate of OH 591 mmol L−1 min−1. This value is drastically lower than that presented by the similar solid prepared without niobium (KaolTi400) [62], with OH generation near 3532 mmol L−1 min−1, This result revealed that Nb5+ acts by reducing the efficiency of photogeneration of TiO2 in UV-C light. This finding corroborates the previous bandgap and XRD results, in turn showing that the increasing absorption of light by the solid induces a decrease in bandgap. XRD revealed that anatase was only formed at higher temperatures, in contrast to the previous solid prepared without Nb5+. This confirms that the Nb5+ ions in the kaolinite matrix prevent the crystallization and also the transition of anatase to rutile. However, the photoefficiency of a photocatalyst depends on many factors, such the mass/solution ratio, light scattering, irradiation wavelength, and the disposal of clay semiconductor particle. Similar results were previously observed by [63].

Table 3.

Experimental data extracted from linear fit of terephthalic acid photocatalytic hydroxylation catalyzed by Kaol400, KaolNb, and KaolTiNb photocatalysts heat treated at 400, 700, and 1000 °C.

The probable mechanism involving KaolTiNb400 and the degradation of organic molecules primarily occurs through the reaction of holes (h+) with adsorbed water and hydroxyl groups on the surface, producing reactive •OH, which are the main agents responsible for photodegradation [61]. Therefore, the semiconductor supported on kaolin has significant potential for stable applications in the photodegradation of a wide range of molecules, including dyes, volatile organic compounds, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals [40,41,61].

With regard to the use of KaolNb and KaolTiNb heat treated at 400, 700, and 1000 °C, the KaolTiNb400 material exhibited the best performance. This superior performance is attributed to the presence of layered kaolinite and the dispersion of nanotitanium on the kaolinite surfaces. It is also notable that the presence of Nb ions decreased the yield of the hydroxy–terephthalic acid reaction.

3.2. Methylene Blue Photodegradation

The experiments described here involving this series of photocatalysts were based on previous experiments by our group [40]. The effects of mass, pH, and dye concentration were not in the scope of this study. The focus here is the diversity of contaminants that this new photocatalyst can efficiently remove.

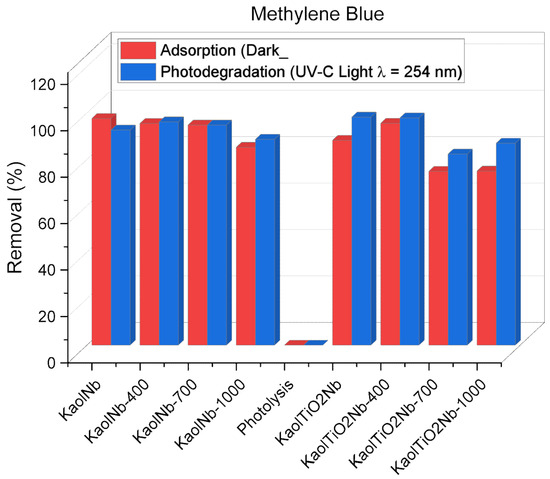

Photolysis did not result in any decrease on the concentration of dye in the analyzed interval time. This demonstrates that the presence of a semiconductor is necessary to promote the generation of hydroxyl radicals and subsequently induce the degradation of MB. We investigated the effect of light exposure on photocatalytic efficiency under artificial UV-C irradiation using a fixed mass of photocatalyst of 2 mg per 5 mL of a 10 mg L−1 MB dye solution, as shown in Figure 9. It shows that the dye removal efficiency was higher with or without light. In some cases of heat-treated samples at 1000 °C, the efficiency decreased to 80%–90%. However, samples without light only caused adsorption (mass transfer phenomena). The resulting solids were completely blue, demonstrating that KaolNb and/or KaolTiNb series can interact efficiently with MB. Nevertheless, the results of materials exposed to UV-C light were consistent with previously reported data [40]. When the UV-C light was applied, the solids did not have any color, indicating that photocatalytic activity actually occurred. The most efficient dye removal was reached by KaolNb-400 and KaolTiNb-400, which might have been caused by an increased number of active sites on the catalyst surface due to the presence of layered kaolinite and nanotitanium disposed in the form of clay platelets. The comparison of the series with and without Nb5+ treated at similar temperatures did not cause significant differences in the solids of KaolTi, KaolTi400, KaolTiNb, and KaolTiNb400, demonstrating that Nb5+ incorporation at the tested concentration did not induce relevant changes in photocatalytic activity. However, at higher temperatures, dye removal by KaolTiNb700 and KaolTiNb1000 decreased from nearly 100 to 80%. This can be ascribed to the decrease in the specific surface area induced by the aggregation of particles acting as barriers to light irradiation and production of *OH radicals. Similar effects were observed in the terephthalic acid hydroxylation reaction. Materials treated at 1000 °C presented the lowest rate of OH formation, near 107 and 172 mmol L−1 min−1 (Table 3).

Figure 9.

Effect of light exposure and presence of Nb5+ ions on the MB removal efficiency using various heat-treated KaolNb and KaolTiNb solids as photocatalysts and 5 mL of MB, 10 mg L−1, time of light exposure, and adsorption experiments of 120 min.

3.3. Loratadine Photodegradation

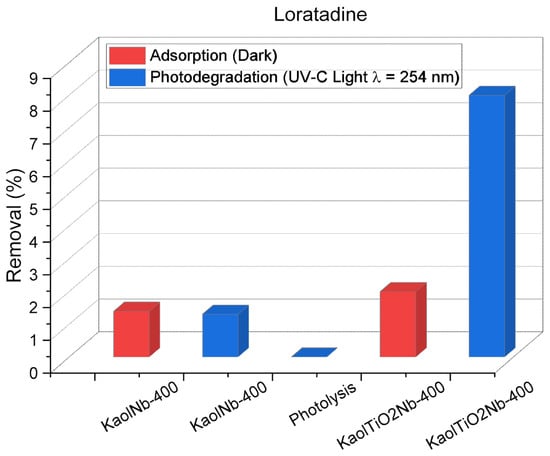

Figure 10 shows that both materials attained negligible Loratadine removal via adsorption, achieving approximately 2%. However, under UV-C irradiation, a modest increase to 8% removal was observed after 120 min. Notably, spectroscopic analysis indicated a shift in Loratadine bands, suggesting the formation of transformation products upon light exposure. Given Loratadine’s inherent stability and resistance to complete oxidation by advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), achieving full mineralization, supported by the limited literature, remains a significant challenge. The addition of H2O2 increased the removal efficiency from 2 to 8%, with dark experiments also revealing that 2% lower adsorption occurs after 120 min, employing Kaol Nb and KaolTiNb400, emphasizing the necessity of UV light to induce the photodegradation mechanism.

Figure 10.

Effect of light exposure and presence of Nb5+ ions for the Loratadine removal using KaolNb400 and KaolTiNb400 materials, 50 mL of Loratadine, 20 mg L−1, time of light exposure, and adsorption experiments = 120 min.

Despite the low removal of Loratadine by adsorption, as previously discussed, we further investigated its degradation under UV-C irradiation, drawing upon the existing literature regarding its photochemistry. Consistent with prior findings [64], Loratadine exhibited significantly faster photodegradation in aqueous solutions. In contrast, byproduct compounds inducing small displacements in the UV absorption band could be found in the aqueous solution. Control experiments carried out by the literature data [64] further revealed that isoloratadine is itself photolabile, undergoing transformation to unidentified materials after 20 min of UV-B irradiation.

Based on these observations and the existing literature, we propose a plausible mechanistic interpretation. The formation of a stable compound is likely initiated by a 1,3-hydrogen shift, potentially proceeding through a radical pair generated from the excited triplet state of Loratadine—a hypothesis supported by the observed quenching in the presence of oxygen [65]. The subsequent recombination of this radical pair can then yield either the original Loratadine or its isomer, isoloratadine. In turn, in the case of byproducts in aqueous media, we propose it involves the addition of water to generate intermediates, followed by β-cleavage of the resulting alkoxy radical intermediate. The β-cleavage of alkoxy radicals, leading to the formation of ketones and stable radicals, is a well established reaction pathway.

3.4. Triaxon Photodegradation

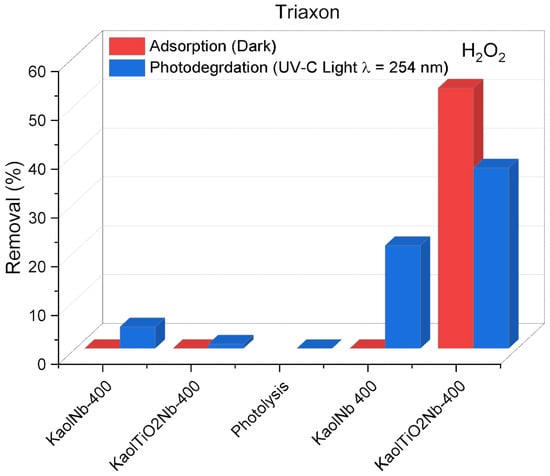

The materials KaolNb and KaolTiNb demonstrated incomplete degradation of ceftriaxone (CTX) under the investigated conditions (Figure 11). Even with the application of light, a maximum of 60% adsorption followed by only 40% degradation was achieved within 60 min. This observation underscores the inherent recalcitrance of complex pharmaceutical molecules, such as antibiotics, toward rapid and direct photodegradation. The intricate molecular structure of CTX likely contributes to its resistance to efficient breakdown within short irradiation periods, highlighting a significant challenge to its removal from aqueous matrices. The addition of 100 µL of H2O2 in the reaction increased the photodegradation to 40% in the case of KaolTiNb400. However, the degradation without light was higher, revealing the complexity of the substrate studied. In both cases, complete mineralization was not achieved.

Figure 11.

Effect of light exposure and presence of Nb5+ ions for Triaxon® removal using KaolNb400 and KaolTiNb400 materials, 5 mL of Triaxon®, 30 mg L−1, time of light exposure, and adsorption experiments = 60 min.

The difficulty faced in achieving rapid CTX degradation aligns with the findings reported in the literature. Shokri et al. (2016) [66] investigated the photocatalytic degradation of ceftriaxone, utilizing immobilized TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles. Their study revealed that while both processes led to substantial degradation over extended timeframes, the UV/TiO2 system achieved a higher removal efficiency (96.7% COD in 480 min) compared to the UV/ZnO system (75% COD in 480 min). The significantly longer reaction times required in their study to reach high removal efficiencies further supports the conclusion that CTX is not readily amenable to rapid photodegradation, requiring more aggressive or prolonged treatment strategies.

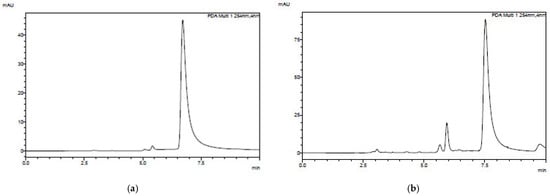

Using HPLC, we observed the formation of byproducts. Figure 12 depicts the ratio of final to initial concentration. However, this degradation was minimal, likely due to the high initial drug concentration (300 mg L−1), consistent with the findings that other parameters remained unchanged [66].

Figure 12.

HPLC chromatogram of (a) initial Triaxon® solution and (b) degraded solution at 240 min. Effect of light exposure and presence of Nb5+ ions for Loratadine removal using KaolNb400 and KaolTiNb400 materials.

Table 4 shows the photodegradation efficiency of various photocatalyst systems compared to the tested pollutants under very similar experimental conditions. It is important to emphasize that pure TiO2 for MB presents higher photoefficiency; however, the dilution on the kaolinite matrix could be a great advantage, because the combined mechanism adsorption and photodegradation induces a similar 100, as previously reported by Barbosa et al. [40]. Triaxon under UV-C was 93% removed at 480 min, compared to 37% after 60 min of our system. The degradation of Trixon is very low, probably due the interval time tested of 120 min, the difference in the initial drug concentration (30 mg L−1), and also the photocatalyst dosage [66]. No results using Loratadine were found in comparison with our systems. The results are very low with the tested interval time: nearly 8% in 120 min. This result confirms the stability of the molecule and UV-C radiation, and open perspectives for the study of new parameters to induce complete photodegradation. The detailed study of the influences of these new parameters like photocatalyst dosage and the addition of oxidants will be tested in future studies.

Table 4.

Photodegradation efficiency of photocatalysts from the literature data compared to our system.

4. Conclusions

The incorporation of Nb5+ ions effectively inhibited the anatase-to-rutile transformation (ART) in TiO2 nanoparticles supported on kaolinite. Our findings demonstrated that the presence of Nb5+ prevents the complete crystallization of titanium oxide phases up to 1000 °C. This suppression of ART is a crucial factor in maintaining the desirable photocatalytic activity of TiO2, since rutile is generally less active than anatase.

Furthermore, the introduction of Nb5+ resulted in a reduction in the bandgap energy, attributed to the creation of sublevels within the TiO2 matrix induced by Nb5+ ion incorporation. While a reduced bandgap can potentially enhance photocatalytic activity by increasing light absorption, terephthalic acid (TA) tests revealed that the highest activity was achieved by materials heat treated at 400 °C. Notably, this optimal activity was significantly lower than that observed for KaolTi materials prepared in our previous studies, suggesting that Nb5+ negatively impacts the generation of hydroxyl radicals, a key species in photocatalytic processes. Future optimization strategies need to be studied, like tuning the Nb levels to result in increases in photocatalytic activity or coupling with other co-catalysts.

Degradation experiments using methylene blue (MB), ceftriaxone (Triaxon®), and Loratadine confirmed the photocatalytic activity of both KaolNb and KaolTiNb materials. However, under the studied conditions, the complete mineralization of these complex organic pollutants was not achieved (only MB was fully removed). This highlights the challenge of degrading more complex pharmaceuticals and emphasizes the need for further optimization of the catalyst and reaction conditions.

While Nb5+ effectively stabilizes the anatase phase and prevents its transformation to rutile at high temperatures, which is a significant advantage for maintaining photocatalytic efficiency, its incorporation also appears to hinder the generation of hydroxyl radicals, ultimately limiting the overall degradation of complex organic pollutants. Further research should focus on balancing these competing effects to optimize the performance of Nb-modified TiO2/kaolinite composites for wastewater treatment applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.B., L.V.B., S.D.d.S., Y.P.V., H.F.M.d.S., V.F.L., M.V.d.P. and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.B., L.V.B., S.D.d.S., Y.P.V., H.F.M.d.S., V.F.L., M.V.d.P. and L.M.; and writing—review, E.J.N., K.J.C., L.A.R., L.M. and E.H.d.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Brazilian group acknowledges support from the research funding agencies Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP (2017/15482–1), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, finance code 001), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq , grant 306328/2024-0). CBMM gently conceded niobium oxalate (NH4NbO(C2O4)2). The equipment of the Brazilian group was financed by FAPESP (1998/11022–3, 2005/00720–7, 2011/03335–8, 2012/11673–3 and 2016/01501–1).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kanan, S.; Moyet, M.; Obeideen, K.; El-Sayed, Y.; Mohamed, A.A. Occurrence, analysis and removal of pesticides, hormones, pharmaceuticals, and other contaminants in soil and water streams for the past two decades: A review. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2022, 48, 3633–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaj, E.; von der Ohe, P.C.; Grote, M.; Kühne, R.; Mondy, C.P.; Usseglio-Polatera, P.; Brack, W.; Schäfer, R.B. Organic chemicals jeopardize the health of freshwater ecosystems on the continental scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9549–9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzeminski, P.; Tomei, M.C.; Karaolia, P.; Langenhoff, A.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Felis, E.; Gritten, F.; Andersen, H.R.; Fernandes, T.; Manaia, C.M.; et al. Performance of secondary wastewater treatment methods for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern implicated in crop uptake and antibiotic resistance spread: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 1052–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, T. Mass flows and removal of antibiotics in two municipal wastewater treatment plants. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.; Fiorentino, A.; Grassi, M.; Attanasio, D.; Guida, M. Advanced treatment of urban wastewater by sand filtration and graphene adsorption for wastewater reuse: Effect on a mixture of pharmaceuticals and toxicity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.; Krätke, R.; Linders, J.; Scott, M.; Vighi, M.; de Voogt, P. Proposed EU minimum quality requirements for water reuse in agricultural irrigation and aquifer recharge: SCHEER scientific advice. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 2, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.; Malato, S.; Antakyali, D.; Beretsou, V.G.; Đolić, M.B.; Gernjak, W.; Heath, E.; Ivancev-Tumbas, I.; Karaolia, P.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; et al. Consolidated vs new advanced treatment methods for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern from urban wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 986–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Diego, M.; Godoy, G.; Mennickent, S. Chemical stability of ceftriaxone by a validated stability-indicating liquid chromatographic method. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2010, 55, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, S.; Li, X.; You, J.; Wang, L.; Cai, J.; Wang, X. Structural regulation and photocatalytic antibacterial performance of TiO2, carbon dots and their nanocomposites: A review. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 700, 138482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergaya, F.; Lagaly, G. General introduction: Clays, clay minerals, and clay science. In Handbook of Clay Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria, E.H.; Lima, O.J.; Ciuffi, K.T.; Nassar, E.J.; Vicente, M.A.; Trujilano, R.; Calefi, P.S. Hybrid materials prepared by interlayer functionalization of kaolinite with pyridine-carboxylic acids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 335, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.K. Phase Transformation of Kaolinite Clay, 1st ed.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, M.C.; Maubane-Nkadimeng, M.S.; Moma, J.A. The use of TiO2/clay heterostructures in the photocatalytic remediation of water containing organic pollutants: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, M.; Aranda, P.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H.; Ruiz-Hitzky, E. ZnO/clay nanoarchitectures: Synthesis, characterization and evaluation as photocatalysts. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 131, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Huang, B.; He, J.; Xiong, R.; Xie, Y. Fe3O4 and CQDs co-doped ZrO2 composite for efficient and recyclable removal of glyphosate: A synergistic effect of adsorption and photocatalysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 126993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoubi, W.A.; Al-Hamdani, A.A.S.; Sunghun, B.; Ko, Y.G. A review on TiO2-based composites for superior photocatalytic activity. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 41, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedneva, T.A.; Lokshin, E.P.; Belikov, M.L.; Belyaevskii, A.T. TiO2-and Nb2O5-based photocatalytic composites. Inorg. Mater. 2013, 49, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Liu, H.; Gao, Z.; Fornasiero, P.; Wang, F. Nb2O5-Based Photocatalysts. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2003156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Trindade, M.T.; Salgado, H.R.N. A critical review of analytical methods for determination of ceftriaxone sodium. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018, 48, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Linghu, X.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shan, D.; Wang, B. Classification and catalytic mechanisms of heterojunction photocatalysts and the application of titanium dioxide (TiO2)-based heterojunctions in environmental remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zheng, G.; Yang, F. Adsorptive removal and oxidation of organic pollutants from water using a novel membrane. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, F.J.; Acero, J.L.; Real, F.J.; Roldan, G.; Casas, F. Comparison of different chemical oxidation treatments for the removal of selected pharmaceuticals in water matrices. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 168, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M.N. Adsorption technique for the removal of organic pollutants from water and wastewater. In Organic Pollutants-Monitoring, Risk and Treatment, 1st ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013; pp. 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, Z. Application of biosorption for the removal of organic pollutants: A review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 997–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvelis, K.; Karavaka, E.E.; Panagiotaras, D.; Papoulis, D.; Frontistis, Z.; Petala, A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Losartan with BiOCl/Sepiolite Nanocomposites. Catalysts 2024, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ye, W.; Xie, M.; Seo, D.H.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.; der Bruggen, B.V. Environmental impacts and remediation of dye-containing wastewater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Touchente, Z.; Khalil, A.M.; Simsek, S.; Boufi, S.; Ferreira, L.F.V.; Vilar, M.R.; Touzani, R.; Chehimi, M.M. Ultrasonic effect on the photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine 6G (Rh6G) dye by cotton fabrics loaded with TiO2. Cellulose 2020, 27, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachs, J.; Méjanelle, L. Organic Pollutants in Coastal Waters, Sediments, and Biota: A Relevant Driver for Ecosystems During the Anthropocene? Estuaries Coasts 2010, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kaur, A. Various Methods for Removal of Dyes from Industrial Effluents—A Review. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauke, N.M.; Mohlala, R.L.; Ngqoloda, S.; Raphulu, M.C. Harnessing visible light: Enhancing TiO2 photocatalysis with photosensitizers for sustainable and efficient environmental solutions. Front. Chem. Eng. 2024, 6, 1356021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Carrott, P.J.M.; Ribeiro, M.M.L.; Suhas, S.J. Low-Cost Adsorbents: Growing Approach to Wastewater Treatment—A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 39, 783–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; Huo, Y.; Yang, M.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y. Monitoring of 943 organic micropollutants in wastewater from municipal wastewater treatment plants with secondary and advanced treatment processes. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 67, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristofco, L.A.; Brooks, B.W. Global scanning of antihistamines in the environment: Analysis of occurrence and hazards in aquatic systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 592, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R.K.; Kirkpatrick, D.L.; Belani, C.P.; Friedland, D.; Green, S.B.; Chow, H.H.S.; Cordova, C.A.; Stratton, S.P.; Sharlow, E.R.; Baker, A.; et al. A Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of PX-12, a novel inhibitor of thioredoxin-1, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 13, 2109–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Serna, R.; Petrović, M.; Barceló, D. Occurrence and distribution of multi-class pharmaceuticals and their active metabolites and transformation products in the Ebro River basin (NE Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 440, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cini, N.; Atasoy, Ö.; UyanikgiL, Y.; Yaprak, G.; Erdoğan, M.A.; Erbas, O. Ceftriaxone has a neuroprotective effect in a whole-brain irradiation-induced neurotoxicity model by increasing GLT-1 and reducing oxidative stress. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2025, 201, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Firoozeh, F.; Moniri, R.; Zibaei, M. Prevalence of CTX-M-Type and PER Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases Among Klebsiella spp. Isolated from Clinical Specimens in the Teaching Hospital of Kashan, Iran. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e22260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, O.; Amábile-Cuevas, C.F.; Shang, C.; Wang, C.; Ngai, K.W. What Water Professionals Should Know about Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance: An Overview. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 1334–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tang, X.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Li, Z. Distribution and persistence of cephalosporins in cephalosporin producing wastewater using SPE and UPLC–MS/MS method. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 569–570, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, L.V.; Marçal, L.; Nassar, E.J.; Calefi, P.S.; Vicente, M.A.; Trujillano, R.; Rives, V.; Gil, A.; Korili, S.A.; Ciuffi, K.J.; et al. Kaolinite-titanium oxide nanocomposites prepared via sol-gel as heterogeneous photocatalysts for dyes degradation. Catal. Today 2015, 246, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.D.; Bonfim, L.F.; Barbosa, L.V.; da Silva, T.H.; Nassar, E.J.; Ciuffi, K.J.; González, B.; Vicente, M.A.; Trujilano, R.; Rives, V.; et al. White and Red Brazilian São Simão’s Kaolinite–TiO2 Nanocomposites as Catalysts for Toluene Photodegradation from Aqueous Solutions. Materials 2019, 12, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaly, M.; Gotor, F.J.; Sayagués, M.J. Mechanically induced combustion synthesis of niobium carbonitride nanoparticles. J. Solid State Chem. 2018, 267, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, O.F.; de Mendonça, V.R.; Silva, F.B.F.; Paris, E.C.; Ribeiro, C. Niobium Oxides: An Overview of the Synthesis of Nb2O5 and its Application in Heterogenous Photocatalysis. Quim. Nova 2015, 38, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, D.F.; Filho, E.C.S.; da Fonseca, M.G.; Jaber, M. Organophilic bentonites obtained by microwave heating as adsorbents for anionic dyes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7080–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.H.; de Souza, T.F.M.; Ribeiro, A.O.; Ciuffi, K.J.; Nassar, E.J.; Silva, M.L.A.; de Faria, E.H.; Calefi, P.S. Immobilization of metallophthalocyanines on hybrid materials and in-situ synthesis of pseudo-tubular structures from an aminofunctionalized kaolinite. Dyes Pigm. 2014, 100, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria, E.H.; Ciuffi, K.J.; Nassar, E.J.; Vicente, M.A.; Trujillano, R.; Calefi, P.S. Novel reactive amino-compound: Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane covalently grafted on kaolinite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Sun, C.; Wood, B.; Wang, L.; Hulicova-Jurcakova, D.; Zou, J.; Rudolph, V.; Lu, G.Q.M. Visible-light photoresponsive heterojunctions of (Nb-Ti-Si) and (Bi/Bi-O) nanoparticles. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiravan, A.; Chandramohan, M.; Renganathan, R.; Sekar, S. Cyanobacterial chlorophyll as a sensitizer for colloidal TiO2. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009, 71, 1783–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübke, M.; Shin, J.; Marchand, P.; Brett, D.; Shearing, P.; Liu, Z.; Darr, J.A. Highly pseudocapacitive Nb-doped TiO2 high power anodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 22908–22914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumer, M.E.; Abate, G.; Messerschmidt, I.; Assis, L.M.; Martinazzo, R.; Silveira, C.A.P. Effect of Chemical Activation on Surface Properties of Oil Shale By-Product. Quím. Nova 2016, 39, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, K.; Lou, L. Photodegradation of dye pollutants on silica gel supported TiO2 particles under visible light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2004, 163, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.P.; Pandikumar, A.; Lim, H.N.; Ramaraj, R.; Huang, N.M. Boosting Photovoltaic Performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Using Silver Nanoparticle-Decorated N,S-Co-Doped-TiO2 Photoanode. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotti, D.K.; Passoni, L.; Maddalena, P.; Fonzo, F.D.; Lettieri, S. Photoluminescence Mechanisms in Anatase and Rutile TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 9011–9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Guinea, J.; Correcher, V.; Rodriguez-Lazcano, Y.; Crespo-Feo, E.; Prado-Herrero, P. Light emission bands in the radioluminescence and thermoluminescence spectra of kaolinite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 49, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, D.T.; de Pádua, G.S.; Peixoto, V.G.; Ciuffi, K.J.; Nassar, E.J.; Vicente, M.A.; Trujillano, R.; Rives, V.; Pérez-Bernal, M.E.; de Faria, E.H. Luminescent properties of biohybrid (kaolinite-proline) materials synthesized by a new boric acid catalyzed route and complexed to Eu3+. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 192, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ücker, C.L.; Riemke, F.; Goetzke, V.; Moreira, M.L.; Raubach, C.W.; Longo, E.; Cava, S. Facile preparation of Nb2O5/TiO2 heterostructures for photocatalytic application. Chem. Phys. Impact 2022, 4, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkauskas, A.; Yan, Q.; de Walle, C.G.V. First-principles theory of nonradiative carrier capture via multiphonon emission. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 075202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ücker, C.L.; Gularte, L.T.; Fernandes, C.D.; Goetzke, V.; Moreira, E.C.; Raubach, C.W.; Moreira, M.L.; Cava, S.S. Investigation of the properties of niobium pentoxide for use in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 102, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.; Xu, J.; Ao, Y.; Wang, P. In-situ growth of zinc tungstate nanorods on graphene for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 57, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žerjav, G.; Albreht, A.; Vovk, I.; Pintar, A. Revisiting terephthalic acid and coumarin as probes for photoluminescent determination of hydroxyl radical formation rate in heterogeneous photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2020, 598, 117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.V.T.P.F.; Barbosa, L.V.; de Souza, S.D.; Ciuffi, K.J.; Vicente, M.A.; Trujillano, R.; Korili, S.A.; Gil, A.; de Faria, E.H. Titania-triethanolamine-kaolinite nanocomposites as adsorbents and photocatalysts of herbicides. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 419, 113483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.V.; Castro, M.S.S.; Ciuffi, K.J.; Nassar, E.J.; Marçal, L.; Pereira, L.R.; Santos, M.F.C.; Ambrósio, S.R.; Gomes, P.S.S.; Nogueira, F.A.R.; et al. Kaolinite-titanium nanocomposite applied to the photodegradation of the genotoxic compound cisplatin and the terephthalic acid hydroxylation reaction. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 676, 132144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, N.; Vijayaraghavan, R. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of nanocrystalline N-doped ZnSb2O6: Role of N doping, cation ordering, particle size and crystallinity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 65223–65231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abounassif, M.A.; El-Obeid, H.A.; Gadkariem, E.A. Stability studies on some benzocycloheptane antihistaminic agents. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005, 36, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turro, N.J.; Cox, G.S.; Li, X. Remarkable inhibition of oxygen quenching of phosphorescence by complexation with cyclodextrins. Photochem. Photobiol. 1983, 37, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, M.; Isapour, G.; Shamsvand, S.; Kavousi, B. Photocatalytic Degradation of Ceftriaxone in Aqueous Solutions by Immobilized TiO2 and ZnO Nanoparticles: Investigating Operational Parameters. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016, 7, 2843–2851. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Lin, W.; Ping, S.; Guan, W.; Hu, N.; Zheng, S.; Ren, Y. Analysis of degradation and pathways of three common antihistamine drugs by NaClO, UV, and UV-NaClO methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 43984–44002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).