Abstract

This paper presents the results of a comprehensive study of a cuboid diamond of variety III according to the mineralogical classification of Y.L. Orlov, which was first discovered in Carnian (Upper Triassic) deposits of the Bulkur anticline in the northeastern Siberian platform. It is established that the crystal has a cubic shape with signs of intense dissolution and is characterized by a zonal–sectorial fibrous internal structure. The central area of the diamond is saturated with microinclusions. The studied cuboid diamond belongs to the IaAB type according to IR spectroscopy data. An accumulation of minerals, which is represented by chamosite (Fe-rich chlorite), quartz, and pyrite, as well as rare native metals (Fe, Cu, and Ag) and intermetallides (chromferide), is present on the diamond surface. The chemical composition and morphology of chamosite indicate its low-temperature hydrothermal–diagenetic origin (50–150 °C, pressure < 1 kbar) in the marine or lagoon sedimentary environment of the rift basin of the Siberian platform during the Triassic. The discovery of a diamond of variety III, characteristic of large industrial kimberlite pipes (Mir, Udachnaya, and Aikhal), in placers of the Leno-Anabar diamond-bearing subprovince indicates a possible unknown primary kimberlite source.

Keywords:

cuboid; diamond; diagenesis; internal structure; mineral crusts; morphology; Siberian platform 1. Introduction

Cuboid diamonds of variety III according to the Orlov mineralogical classification [1] are found in placers of the Leno-Anabar diamond-bearing region (Mayat, Morgogor, Ebelyakh, etc.) of the northeastern Siberian platform (Arctic Yakutia, Russia). In addition, crystals of this variety are often found in large industrial kimberlite pipes of the Yakutian diamond-bearing province (Mir, Udachnaya, Aikhal, etc.) [2], which distinguishes them from other varieties included in the polygenic population of Arctic Yakutian placer diamonds with unknown primary sources. Cuboid diamonds of variety III, along with those common in placers with flat-sided, laminar octahedrons of variety I and cuboids of variety II, are part of a genetically isolated diamond association of presumably kimberlite origin. However, these diamonds have certain mineralogical features that characterize the type of their mantle and primary sources, as well as the postgenetic history of placer formation. Until now, placer diamonds of variety III have not been systematically studied; previous research has focused on varieties I, II, V, VI, VII, and XI [2,3,4,5,6], and available information on variety III remains scattered.

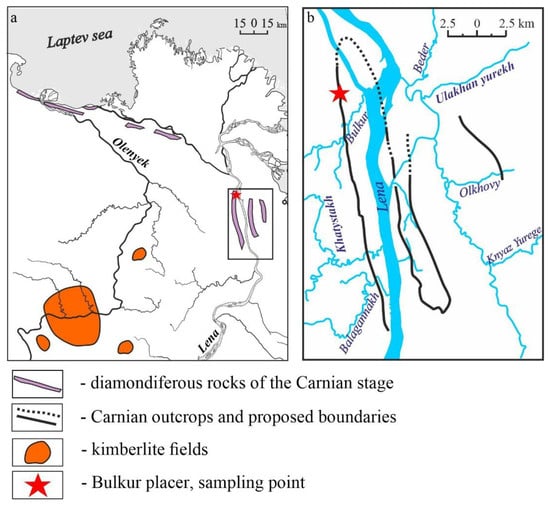

The Bulkur placer is located on the left bank of the Lena River (Figure 1). Here and on the right bank of the river, there are outcrops of Carnian volcanogenic–sedimentary diamond-bearing rocks (tuffs and gravelites). They extend to the mouth of the Olenyek River and further along the coast of the Laptev Sea to the Eastern Taimyr. The following hypotheses have been critically considered as sources of diamonds: redeposition and long-range transport from diamond-bearing reservoirs, redeposition from the weathering crust of kimberlites of near-demolition, hydroexplosive clastic origin of rocks, and the direct volcanogenic–sedimentary genesis of diamond-bearing deposits. Studies of the rock composition suggest extensive eruptive volcanism involving lamproite magmas, which are the source of exotic diamond varieties V–VII in the Yakutian diamondiferous province [7]. An alternative hypothesis currently remains the assumption that the diamonds were the products of the activity of volcanoes of diamond-bearing tuffs of the Triassic age [8].

Figure 1.

Schematic map of Carnian diamondiferous rock location on the northeastern Siberian platform (a); enlarged fragment of the selected area (b).

2. Methods

Optical microscopy studies of the morphology of diamonds were performed by means of an Olympus SZX-12 stereoscopic microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital camera. An OI-19 ultraviolet illuminator (Lomo Ltd., St. Petersburg, Russia) was used to excite photoluminescence. A microscopic examination of a flat, plane-parallel diamond plate was performed using transmitted light and an Axioskop 40A Pol polarizing microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany).

In order to visualize the internal structure of a diamond in three-dimensional space, as well as identify possible defects or mineral inclusions, an analysis of an entire diamond crystal was performed using a SkyScan 1272 X-ray microtomography (Bruker Corp., Billerica, MA, USA). The CT images were reproduced with the NRecon Software, and the 3D images were processed and analyzed with the CTAnalyser Software (engineer Kedrova T.V., PJSC “ALROSA”, Mirny, Russia).

Photoluminescence spectra were recorded on an InVia confocal Raman microscope (Reinishaw plc., Wotton-under-Edge, UK) in the wavelength range from 300 to 700 nm using a 325 nm laser.

The micromorphology of diamond crystals and mineral formations on their surface and in diamond cracks was studied using a JEOL JSM-6480LV electron scanning microscope (engineer Popov A.V., DPMGI SB RAS, Yakutsk, Russia). The chemical composition of the mineral microphases was determined using a scanning electron microscope equipped with an Oxford Energy 350 energy dispersion spectrometer (Oxford Instruments plc., Abingdon, UK) at a voltage of 20 kV, a current of 1 nA, and a beam diameter of 1 micron. Cathodoluminescence patterns were recorded with a Gatan Mini CL attachment to the JEOL JSM-6480LV electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). To improve the accuracy of the elemental analysis result, the sample preparation consisted of polishing the surface of the sawn diamond, followed by carbon spraying.

Defects and impurities in diamond crystals were studied by transmission using an infrared spectral complex consisting of an automated FT-801 IR Fourier spectrometer and a MICRAN-2 infrared wide-range microscope (engineer Molotkov A.E., DPMGI SB RAS, Yakutsk, Russia). The intensity of the absorption spectrum was normalized according to the internal standard of the intrinsic lattice IR absorption of diamond [9].

3. Results

3.1. Morphology of Diamond Variety III

According to previously studied diamond samples from the Mayat and Morgogor placers of the Anabar diamondiferous region of Yakutia, crystals of variety III have cubic and combination shapes (cube–rhombic dodecahedron) and are dissolved to varying degrees. They are primarily translucent in the center, with the color ranging from clear to varying degrees of gray or greenish-gray with a blue tint. The crystals are rich in needle-shaped microinclusions oriented along the [110] direction.

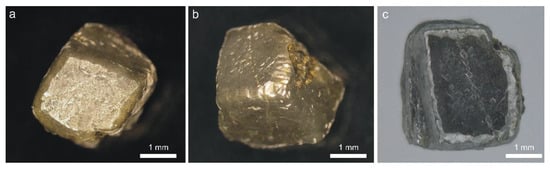

A relatively large cuboid crystal (8082) was studied in detail, which is of interest as a single find in the Bulkur placer of a diamond of variety III with tightly attached mineral crusts on the surface. The diamond weighs 0.75 carats. Its cuboid shape is isometric, with a slight flattening along the (100) face (Figure 2a). The cube’s edges are partially replaced by convex, spherical rhombic dodecahedron pseudofaces. The surface relief of the rhombic dodecahedron faces has a blocky structure (Figure 2b). The crystal is crossed by extended etching channels located along microcracks. A dense cellular complex of tetragonal etch pits, inversely oriented relative to the crystal’s cubic edges, is observed on the (100) faces (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Images of variety III diamond (8082) from the Carnian deposits of the Bulkur anticline in three projections: (a) the general appearance of the crystal; (b) corroded cracks and block structure of the dodecahedron surfaces, blunting the edges of the cube; (c) tetragonal etching pits on the cube face (oblique illumination).

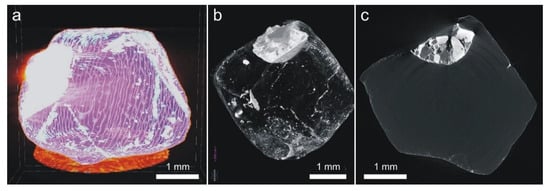

On a polished section along (100) taken through the center of the crystal 8082, its fibrous zonal structure was visually observed in reflected light (Figure 3a). The greenish-yellow fluorescence of the surface under UV radiation (365 nm) more clearly reveals the zonal–sectorial fibrous structure of the crystal with parallel fiber orientation in the <100> growth pyramids (Figure 3b). The cathodoluminescence image of the cut surface does not show the sectorial structure of the crystal, but its fibrous structure and cracks in the diamond become more visible (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Images of polished section through the cuboid center along (100) in (a) reflected light; (b) FL; (c) CL.

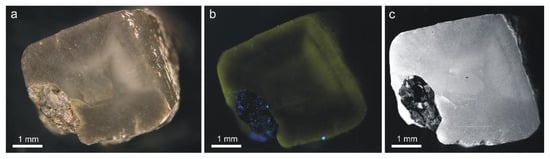

The central translucent region of the crystal is rectangular and saturated with unevenly distributed, isometric, dust-like microinclusions (Figure 4a). The microinclusions are generally uniform in size, approximately 2 µm, but increase slightly to 4–5 µm in clusters (Figure 4b,c). This may be due to an increase in size as a result of local fusion of inclusions.

Figure 4.

Images of the central polished diamond plate (8082) along (100) in transmitted light: (a) general view of the plate; (b,c) scattered micro-sized inclusions in the center of the transparent area of the crystal.

3.2. Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy and Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy

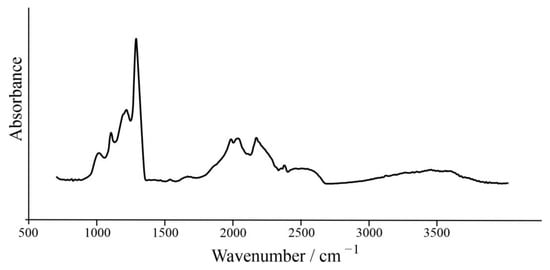

The IR spectrum of a plane-parallel plate of cuboid diamond 8082 was recorded through the central transparent region. A spectrum with a spectral resolution of 2 cm−1 was obtained integrally from 50 scans (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

An absorption spectrum for the central area of the diamond plate (the variety III cuboid diamond 8082 from the Carnian deposits of the Bulkur anticline).

The spectral pattern in the single-phonon absorption region is characteristic of diamond crystals of the IaAB type. As in the standard spectrum of variety III diamonds [1], an absorption band at 1282 cm−1 is present. In addition, absorption bands are recorded at 1210 and 1100 cm−1, also responsible for the presence of the A defect (a pair of nitrogen atoms in neighboring substitution positions [10]). Their intensity overlaps the invisible absorption lines at 1175 and 1332 cm−1, characteristic of the B1 defect (four substitutional nitrogen atoms around a vacancy [11]. The presence of the line at 1010 cm−1 indicates the presence of B1 defects. In the three-phonon region, the presence of a peak at 3107 cm−1 of low intensity 0.5 cm−1 marks vibrations within the vinylidene group (>C=CH) [12].

The concentrations of nitrogen impurity in the form of A and B1 defects were calculated using the methodology for IaAB-type diamonds [13], with an amendment proposed by Khachatryan [14]. The calculated concentrations of nitrogen defects are 574 ppm (A) and 80 ppm (B1).

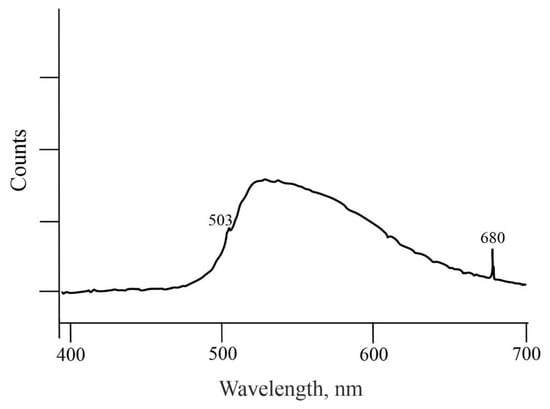

The PL spectrum of crystal 8082 (Figure 6) is typical of previously studied diamonds of variety III from the Aikhal and Udachnaya kimberlite pipes [2] and is characterized by a broad, structureless band, the presence of the nitrogen-containing center H3 (503 nm), and a narrow band in the 680 nm region.

Figure 6.

The PL spectrum of crystal 8082.

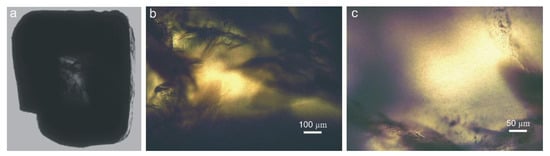

3.3. X-Ray Microtomography

Against the background of the diamond crystal’s mass, which is uniform in X-ray density, the tomographic images show numerous high-contrast solid inclusions with increased density relative to the main volume of the diamond. Inclusions are distributed throughout the crystal, with the largest ones located closer to the diamond’s periphery (Figure 7a). Small and medium-sized inclusions form “chains” that allow one to observe the orientation of cracks within the crystal (Figure 7a,b). Using 3D X-ray microtomography and tomographic sections, the relationships between mineral phases in a cup-shaped cavity of the cubic diamond were observed in detail. This cavity is visually distinguished by the relatively different X-ray densities of the variously shaped mineral grains filling it (Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

Image of the internal structure of a crystal obtained using X-ray microtomography: (a) high-contrast three-dimensional image of a crystal with internal defects of inclusions and mineralized cracks with different X-ray densities; (b) three-dimensional image of a crystal with a cup-shaped depression filled with minerals; (c) tomographic section of a mineralized depression in a crystal.

3.4. Composition of Mineral Crusts on the Surface and in Cracks of the Diamond Crystal

Scanning electron microscopy and microprobe analysis provided significantly enhanced data on the morphology, mineral relationships, and chemical composition. First, the natural crystal surface was examined. Then, after cutting and polishing the diamond, minerals exposed on the surface of the polished sections and on fresh diamond cleavages were studied.

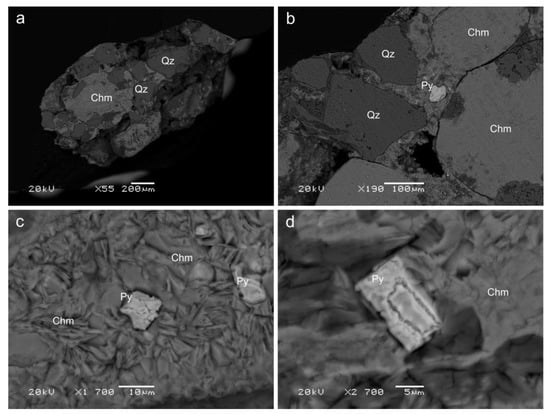

The SEM image of a polished section intersecting the aforementioned cup-shaped depression reveals a cluster of tightly cemented mineral grains (Figure 8). The mineral assemblage consists of coarse quartz fragments and ovalized chamosite (Fe-bearing Al-Mg-Fe chlorite), as confirmed by the results of microprobe analysis of the chemical composition. Judging by the angular and ovalized shape of the minerals, also observed using optical microscopy and X-ray tomography, their unsorted size composition is evident. A significant portion of the clasts is represented by coarse quartz fragments and isolated oval chamosite grains (Figure 8a,b). The detrital material is cemented by a foliated–flaky chamosite aggregate, inferred to be of a later generation. Idiomorphic pyrite micrograins are scattered within the cementing mass of the chamosite aggregates (Figure 8c), and a zoned cubic pyrite metacrystal is noted (Figure 8d). In addition to the minerals listed above, rare thin calcite crusts and TiO2 grains measuring 20–30 μm are present in the depression.

Figure 8.

Mineral assemblage in a diamond cavity (SEM): (a,b) brecciated association of cemented coarse quartz grains (Qz), oval chamosite (Chm) and pyrite (Py) grains; (c) cementing foliated–flaky chamosite aggregates with pyrite grains; (d) cubic pyrite metacrystal in a foliated–flaky chamosite aggregate.

The microprobe analyses of chamosite are given in wt% oxides with oxygen calculation based on the stoichiometry of chamosite ((Fe,Mg)5Al(Si3Al)O10(OH)8). The stoichiometry was calculated based on normalization to 10 cations (4 tetrahedral + 6 octahedral sites), typical for the chlorite structure (excluding H2O ≈ 12–14 wt%) (Table 1). The composition of chamosite in ovalized grains and in the late foliated–flaky aggregates enclosing them differs in the content of Mg, Fe, and Al. Table 1 presents the microprobe analyses of oolitic particles in a cup-shaped depression (analysis No. 1). In addition, the data for chamosite are shown for comparison: the binding foliated–flaky mass (analysis No. 2) and a thin film tightly attached to the diamond surface (analysis No. 3).

Table 1.

Composition of oxides and distribution of cations by positions in the structure of chamosite (microprobe analysis) in various types of precipitates on the surface and in cracks of diamond.

Based on the analysis 1 composition calculation, the stoichiometric formula is given by (Mg0.98 Fe3.34 Al1.69)6 (Si2.86Al1.14)4 O10 (OH)8. The analysis calculations confirm Fe-rich chlorite (chamosite), with a slight Mg deficiency and an elevated Al content in the octahedral position. The calculation of analysis 2 is closer to the composition of chlorite: (Mg0.68 Fe3.49 Al1.83)6 (Si2.79 Al1.21)4 O10 (OH)8. The high Fe content in the octahedral position confirms chamosite as the end member in the Fe content of the chlorite group. It is noteworthy that chamosite has an elevated Fe content in a deep diamond crack, which may indicate a typical accumulation of iron hydroxides in mechanical defects of the crystal.

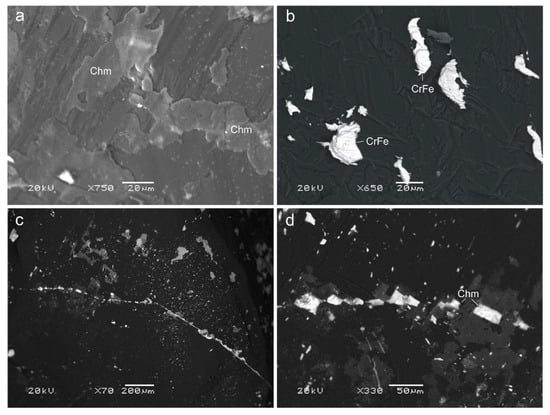

Chamosite segregations characteristically appear as thin films and crusts observed by SEM on the natural diamond surface (Figure 9a). Due to the finely distributed nature of the mineral formations, EDS analysis only allows qualitative characterization without a full stoichiometric analysis. Additionally, numerous microparticles of native metals (Fe, Cu, and Ag) and intermetallic compounds Cu-Fe and chromferide (Fe 86-88, Cr 14-12) were found tightly attached to the negative microsculptures of the diamond’s microrelief (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

Mineral segregations on the surface of a diamond crystal (scanning electron microscope): (a) thin crusts of chamosite (Chm) tightly attached to the diamond surface (BSE); (b) crystalline scaly segregations of chromferide (Cr-Fe) in the depressions of the diamond microrelief; (c,d) mineralized protogenetic crack in a diamond filled with chamosite (Chm).

Thin cracks in the diamond are also filled with mineral phases of the same association. Judging by the pronounced symmetrical crystallographic shape of the surface, the cracks in the diamond are of syngenetic origin. They likely formed during the diamond’s growth period, and the cracks mark the boundaries between crystalline blocks. On the outer side of the crystal, the cracks are completely filled with chamosite (Figure 9c,d).

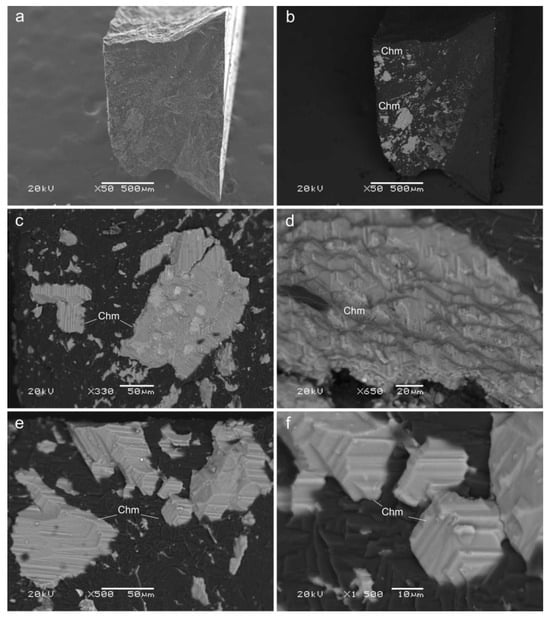

During mechanical processing of the crystal, a fresh diamond cleavage was obtained along a protogenetic mineralized fracture, as shown in the SEM image (Figure 9c,d). The fracture opened by the cleavage is covered with chamosite precipitates across its entire depth and surface (Figure 10a,b). It is interesting that the symmetrical trigonal positive relief of the chamosite surface is induced by the negative microrelief of the dissolution of the crack surface in the diamond in the form of an imprint left after its cleavage (Figure 10c–f). Thus, the crack in the diamond shows clear signs of natural etching of its internal walls. Chamosite precipitates covering the entire surface of the crystal cleavage demonstrate the significant penetration depth of chamosite mineralization into the cracks intersecting the diamond crystal.

Figure 10.

Chamosite mineral formations on the cleavage surface along a protogenetic fracture in the diamond: (a,b) surface of a freshly mineralized cleavage along a fracture in diamond ((a) SE, (b) BSE); (c–f) symmetrical microrelief pattern covering the chamosite surface induced by the crystallographic surface of the diamond.

4. Discussion

According to the interpretation of Yu. L. Orlov [1], the III mineralogical variety of diamond crystals, based on finds from large kimberlite pipes of the Yakut diamondiferous province, includes crystals of type I according to the physical classification of diamonds, enriched in nitrogen. The crystals are predominantly cubic in shape with traces of intense etching of the faces. Less often, the dominant cube faces are found in combination with rhombic dodecahedron and octahedron faces. The diamonds are translucent, colorless, or colored to varying degrees in shades of gray to black, with a complete loss of transparency. The crystals are characterized by a complex internal structure, zoning, the presence of a transparent zone in the center, and zonal fluorescence in UV. At the same time, the outer region is saturated with micro-sized inclusions, which is the cause of their low transparency and specific coloration. These characteristics are the main typomorphic features of this variety and have undergone virtually no changes. Later, diamonds of variety III were discovered in placers of the northeastern Siberian platform [2].

Based on the complex of identified typomorphic mineralogical features and physical characteristics of the defect–impurity composition, the cuboid diamond crystal found in the Carnian deposits confidently belongs to variety III according to Orlov’s mineralogical classification [1].

The curved surfaces on the edges of the cuboid and the dense microrelief of etching pits on the cube faces indicate that the crystal has undergone a process of bulk dissolution [1,5]. Similar features are also characteristic of curved dodecahedroids of variety I of the Ural type and crystals and intergrowths of varieties V and VII, discovered in the same Bulkur placer where the diamond of variety III was discovered [15]. In addition to the varieties listed, curved forms of crystal dissolution are observed in cuboid diamonds of the variety II from the Anabar region [6]. This fact suggests a common genetic history of the diamond population from placers of the northeastern Siberian platform, which is associated with an episode of mass dissolution of crystals under conditions of presence in a fluid-saturated, water-containing carbonate–silicate melt.

The calculated concentrations of A (574 ppm) and B1 (80 ppm) defects of variety III cuboid diamond correspond to the values of previously studied diamonds from the volcanogenic–sedimentary deposits of the Carnian stage of the Upper Triassic of the Bulkur region. In [16], two groups were distinguished, characterized by different degrees of nitrogen aggregation, which probably indicates differences in the processes of their post-growth history. The crystal (8082) under consideration belongs to the first of the previously distinguished groups. In this group, the average value of the total concentration of nitrogen defects was 916 ppm, with a degree of aggregation of 18%, which is close to the values obtained for the crystal we are describing—654 ppm and 12%.

The mineral crust on the surface of a diamond from Triassic deposits (approximately 252–201 million years old) consists of an association of quartz (Qz), chamosite (Chm, Fe-rich chlorite), and pyrite grains (Py). It is typical of secondary (placer) diamondiferous provinces in the Siberian Arctic. The diamonds here were redeposited from primary sources, possibly kimberlites, with the formation of volcanic–sedimentary or sedimentary–tuff rocks. The composition of the mineral crust on the diamond reflects a series of post-sedimentary processes associated with the transport, accumulation, and transformation of diamondiferous deposits in a sedimentary environment. Chamosite is widespread in the rocks of the Bulkur anticline; it forms numerous lappi and the cementing mass of tuffs [16], and its formation in the tuffisites of the Carnian stage is associated with the development of secondary processes in the marine environment [8,15].

Chromferide has previously been detected on the surface of diamond crystals from Carnian deposits of varieties I, V, and VII [15]. The presence of native metals (Fe and Cu) and intermetallic compounds (chromferide) on the diamond surface and in close association with diamond in the form of inclusions may indicate a high rate of pressure and temperature drop during the post-crystallization stage of the genesis of lithospheric and sublithospheric natural diamonds [17]. The sharp change in PT parameters during the transportation of cubic diamonds of variety II, which are part of the diamond population of the northeastern Siberian platform, to the Earth’s surface is also associated with the decompression effect [6], which also confirms the high rate of ascent of diamond-bearing rocks that fed placers in this region.

Let us consider the literature data on the diagenetic conditions of chamosite formation on the surface and in diamond fractures. The conclusion that the composition of Fe-rich chlorite (chamosite) with a slight Mg deficiency and elevated octahedral Al is typical of hydrothermal or diagenetic conditions is based on classical and modern studies of the authigenic (secondary) mineralization of chlorites in sedimentary rocks. These studies analyze the structural and chemical characteristics of chamosite (Fe/(Fe+Mg) > 0.5, octahedral Al ~2–3.5 at., and tetrahedral Al ~1–2 at.), which forms at temperatures of 50–150 °C in reducing environments. These include anaerobic sediments, with the participation of organic matter and Fe2+ from the dissolution of carbonates or oxides.

The work [18] describes the reactions of formation of authigenic chlorite (including chamosite) during diagenesis of sandstones, with the participation of Fe2+ and Mg2+ during illitization of smectite and destruction of kaolinite. Formation is indicated at depths of 2–4 km at T ~100–150 °C, with a deficiency of octahedral cations (sum <12), similar to the analysis of chamosite described here. This confirms the hydrothermal–diagenetic nature with an increased content of AlVI.

The article [19] details the transformation of berthierinite (a precursor of chamosite) into chamosite at T 60–150 °C in reducing sediments, with the reactions 9FeCO3 + 3Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + … → (Fe9Al3)Al3Si5O20. The authors [19] emphasized the role of elevated Al content in the octahedron and Mg deficiency in iron-rich chamosite, characteristic of early mesodiagenesis.

Judging by the recorded composition of chamosite in the surface formations of diamond (Fe ~3.34 at., AlVI ~1.69 at., Mg ~0.98 at.), and based on a review of the temperature regimes of diagenesis with the composition of minerals [20], the closest models for our case are [18,19], where such proportions record the transition from early diagenesis with berthierine to mesodiagenesis.

Chamosite is stable under low-temperature metamorphic conditions (greenschist facies, 150–300 °C), where it replaces other layered silicates. The processes of late diagenesis with chloritization and secondary mineral transformations under the influence of volcanic fluids and heating (50–150 °C) in the context of Triassic and Permian–Triassic deposits of Siberia are considered in the work [21]. Post-volcanic low-temperature alterations in the tuffs of the Siberian traps (the Putorana Plateau region, northern Siberia, was considered) were recorded, including chloritization and sericitization (with the participation of K-Fe-Mg micas and kaolinite) under the influence of volcanic fluids. The authors emphasize progressive stages of alteration at temperatures consistent with late diagenesis (low T, up to 50–150 °C, and pressures < 1 kbar) with enrichment of the sediment composition in MgO and TiO2. This is directly related to the Triassic volcanosedimentary complexes of Siberia, where such processes record the massive influence of trap magmatism on sediments.

Chamosite (Al-Mg-Fe chlorite) forms in clay fractions during compaction and sedimentation, often in ferruginous sediments (oolites or shales), and fixes Fe from dissolved forms during early diagenesis. This may indicate a Triassic marine or lagoonal environment with high organic and Fe contents, typical of the Siberian platform rift basin.

Pyrite grains and crystals found in the mineral crust on the diamond surface also correspond to the formation conditions of this mineral assemblage as an authigenic mineral precipitating at pH 4–7 and also at relatively low temperatures (<100 °C).

Quartz is the main sedimentary component, indicating the clastic nature of the crust (sand fraction). The presence of coarse quartz grains without signs of mechanical processing within the mineral admixtures and the fairly size-sorted sedimentary material may indicate an admixture of marine sand sediments in the host rocks.

Almost all of the mineral phases detected on the diamond crystal were previously found in mineral crusts on the surface of diamonds of varieties I, V, and VII from the Bulkur site [15]. They represent an eclogite association syngenetic to the diamond and a complex of mineral paragenetic associations reflecting stages of low-temperature hydrothermal diagenesis of volcanogenic–sedimentary rocks under marine conditions.

The genetic peculiarity of cuboids of variety III is expressed in the characteristic crystallography. In contrast to diamonds of varieties I [1], II [5,6], and V [2], cuboid diamonds of variety III from placers of the northeastern Siberian platform and kimberlites of the Yakut diamondiferous province [2], as well as those known in the Arkhangelsk kimberlites with a similar population of diamond varieties [22], do not have transitions to curved crystal forms in the form of a tetrahexahedroid or dodecahedroid, which have survived deep volumetric dissolution in hydrous melts. This morphological typomorphic feature determines the possibility of combining diamonds of variety III together with planar and laminar octahedra of variety I in a stable association of diamonds of kimberlite genesis with a common type of mantle source.

5. Conclusions

This thorough crystal study marks the first discovery of a variety III cuboid diamond in Carnian Triassic deposits. It expands the typomorphic diversity of the diamond population belonging to the kimberlite group common in the largest high-diamond-bearing kimberlite pipes of the Yakutian diamondiferous province (Aikhal, Udachnaya, and Mir). This fact strengthens the case for a kimberlite origin for some of the diamond population in the Leno-Anabar diamondiferous region and highlights the prospects for discovering a large kimberlite source.

The mineral assemblage found on the surface and in deep fractures of variety III crystal indicates a Triassic marine or lagoonal sedimentary environment with a high Fe content, typical of rift basins on the Siberian platform. Diagenesis likely occurred at temperatures of 50–150 °C and pressures < 1 kbar.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, A.P., S.U., A.B. and O.O.; software, visualization, A.P. and S.U.; investigation, optical and scanning electron microscopy, A.P. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and S.U.; project administration, S.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 25-27-20056).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Orlov, Y.L. The Mineralogy of Diamond; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977; 233p. [Google Scholar]

- Zinchuk, N.N.; Koptil, V.I. Typomorphism of Diamonds of the Siberian Platform; Nedra: Moscow, Russia, 2003; 603p. [Google Scholar]

- Grakhanov, S.A.; Molotkov, A.E.; Oleinikov, O.B.; Pavlushin, A.D.; Pomazansky, B.S. Typomorphism and isotopes of diamonds Triassic tuffites Bulkur anticline. Russ. Geol. 2015, 5, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ugapieva, S.S.; Pavlushin, A.D.; Goryainov, S.V.; Afanasiev, V.P.; Pokhilenko, N.P. Comparative characteristics of diamonds with olivine inclusions from the Ebelyakh placer and kimberlite bodies of the Yakutian diamond-bearing province. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2016, 468, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragozin, A.; Zedgenizov, D.; Kuper, K.; Kalinina, V.; Zemnukhov, A. The Internal Structure of Yellow Cuboid Diamonds from Alluvial Placers of the Northeastern Siberian Platform. Crystals 2017, 7, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlushin, A.D.; Zedgenizov, D.A.; Pirogovskaya, K.L. Crystal morphological evolution of growth and dissolution of curve-faced cubic diamonds from placers of the Anabar diamondiferous region. Geochem. Int. 2017, 55, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letnikova, E.F.; Lobanov, S.S.; Pokhilenko, N.P.; Izokh, A.E.; Nikolenko, E.I. Sources of clastic material in the Carnian diamond-bearing horizon of the northeastern part of the Siberian Platform. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2013, 451, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grakhanov, S.A.; Proskurnin, V.F.; Petrov, O.V.; Sobolev, N.V. Triassic Diamondiferous Tuffaceous–Sedimentary Rocks in the Arctic Zone of Siberia. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2022, 63, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyuev, Y.A. The intensity of bands in the IR absorption spectrum of natural diamonds. Almazy 1971, 6, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G. The A nitrogen aggregate in diamond—Its symmetry and possible structure. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1976, 9, L537–L542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, E.V.; Lisoivan, V.I. On the nature of the properties of an intermediate type diamond. Rep. USSR Acad. Sci. 1972, 204, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, G.S.; Collins, A.T. Infrared absorption spectra of hydrogen complexes in type I diamonds. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1983, 44, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokiy, G.B.; Bezrukov, G.N.; Klyuev, Y.A.; Naletov, A.M.; Nepsha, V.I. Natural and Synthetic Diamonds; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1986; 270p. [Google Scholar]

- Khachatryan, G.K. Improved methodology for estimating nitrogen concentrations in diamond and its practical application. In Geological Aspects of the Mineral Resource Base of ALROSA. Current State, Prospects, Solutions; MGT: Mirny, Russia, 2003; pp. 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlushin, A.D.; Grakhanov, S.A.; Smelov, A.P. Paragenetic associations of minerals on the surface of diamond crystals from deposits of the Carnian stage of the northeastern Siberian platform. Russ. Geol. 2010, 5, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Molotkov, A.E.; Pavlushin, A.D.; Smelov, A.P.; Grakhanov, S.A.; Oleinikov, O.B.; Kovalchuk, O.E. Defective impurity composition of diamond crystals from deposits of the Carnian stage of the northeastern Siberian platform. Russ. Geol. 2014, 5, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chepurov, A.; Sonin, V. Metallic inclusions in natural diamonds and their evolution in the postcrystallization period. Geol. Ore Depos. 2025, 67, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, J.R.; Franks, S.G. Clay diagenesis in Wilcox sandstones of southwest Texas: Implications of smectite diagenesis on sandstone cementation. J. Sediment. Petrol. 1979, 49, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Iljima, A.; Matsumoto, R. Berthierine and Chamosite in Coal Measures of Japan. Clays Clay Miner. 1982, 30, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, S.D.; Elders, W.A. Authigenic layers silicate minerals in bore holes Elmore 1, Salton Sea geothermal field, California, USA. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1980, 74, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchl, G.; Gier, S. Petrogenesis and alteration of tuffs associated with continental flood basalts from Putorana, northern Siberia. Lithos 2003, 67, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanin, V.; Garanin, K.; Kriulina, G.; Samosorov, G. Diamonds from the Arkhangelsk Province; NW Russia; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; 265p. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).