Abstract

Mid-Neoproterozoic magmatism provides important constraints for revealing the break-up history of the Rodinia supercontinent. Large-sized mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks are distributed within the Dabie Orogen located on the northern Yangtze Block. This study performed zircon LA-ICP-MS geochronology, whole-rock major and trace elements, and zircon Lu-Hf isotope analyses on orthogneisses with a mid-Neoproterozoic protolith age of the northern Dabie Orogen. The analysis results show that the intrusion times of mid-Neoproterozoic granitoids and mafic rocks are all ~750 Ma, with εHf(t) values ranging from −6.60 to −2.57 and a two-stage Hf model age of ~1.8 Ga. They are characterized by light rare earth element (LREE) enrichment and heavy rare earth element (HREE) depletion. In the primitive mantle-normalized trace element diagram, these rocks are enriched in La, Ce, Th, K, Zr, Nd, and Sm and depleted in Nb, Ta, P, Ti, and Sr, with negative Eu anomaly or no significant Eu anomaly. Based on the discrimination diagrams, most of the samples are plotted into the A-type granite field, and which was formed in a post-orogenic extension setting. Comprehensive analysis shows that these mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks were produced by melting of juvenile crust of the Paleoproterozoic and late Mesoproterozoic, having a heterogeneous distribution of δ18O, indicating that these rocks were developed mainly through high-temperature meteoric-hydrothermal alteration during syn-rift magmatic activity.

1. Introduction

The periodic assembly and break-up of supercontinents not only dominated a global tectonic evolution but also critically impacted the sea level, climate change, life evolution, and resource and energy effects during Earth’s evolution [1]. The Rodinia supercontinent, which assembled during the late Mesoproterozoic and broken up during the Neoproterozoic [2,3], is important in Earth’s evolution history. The break-up of the Rodinia supercontinent had remodelled the global tectonic framework and controlled the tectonic-magmatic evolution during the Neoproterozoic [4,5,6], and causing critical changes to the sea level and climate. These changes in turn resulted in the global glacial event (Snowball Earth) [1,7], oxygen enrichment [8], the origin and explosion of life [9], and other events. Therefore, the Neoproterozoic era is one of the most important periods in Earth’s evolution history.

The South China Block (SCB) is one of the most representative continents that recorded Neoproterozoic tectonic evolution [3,4,5,6,7,10,11]. The Yangtze Block, the northwestern part of the SCB, is characterized by Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks formed from the break-up of the Rodinia supercontinent, with their ages predominantly ranging from ~830 to 740 Ma [4,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Large-scale magmatic activity, include 18O-depleted magmatic rocks formation, and the formation of the juvenile crust in the Yangtze Block is key for revealing the tectonic evolution during the Neoproterozoic. Neoproterozoic magmatism occurrence has been proposed by many models, including the mantle plume rift model [4,18], the plate-arc model [10,19], and the plate-rift model [5,6]. However, the genesis mechanism of these mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks remains a controversial issue.

The Luzhenguan Group, located on the northern Dabie Orogen (NDO), is composed of orthogneisses whose protoliths are mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks [6,20,21,22,23,24]. Since these rocks had only undergone low-grade metamorphism [25,26], and their geochemical characteristics had not been altered by the Triassic subduction and exhumation process of the Yangtze Block or significantly affected by the Yanshanian magmatism. Therefore, they are perfect for studing the mid-Neoproterozoic tectonic evolution and magmatism of the Yangtze Block.

Based on detailed field observations, this study conducted zircon LA-ICP MS U-Pb geochronology, whole-rock major and trace element, and zircon Lu-Hf isotope analyses on the orthogneisses of the Luzhenguan Group in the NDO, providing some new evidence on the mid-Neoproterozoic tectono-magmatic evolution in the northern Yangtze Block.

2. Geological Setting and Sample Descriptions

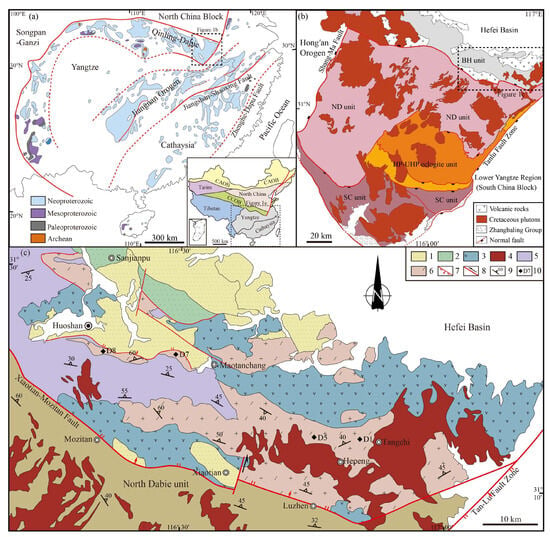

The Dabie Orogen is situated in the eastern part of the Qinling–Tongbai–Hong’an–Dabie Orogen in Central China. This orogen is devided by the NE-trending Tanlu Fault Zone and the Shang-Ma Fault in the east and west, respectively. It is usually divided from north to south into the Beihuaiyang (BH) unit, the North Dabie (ND) unit, the high-pressure and ultra-high pressure (HP-UHP) eclogite unit, the Susong complex (SC) unit, and the Zhangbaling Group (Figure 1) [27].

The Dabie Orogen was formed due to the subduction of the SCB under the North China Block (NCB). Zircons in eclogites and their wall rocks in the orogen are usually characterized by a residual core and a metamorphic mantle, and zircon cores generally recorded mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic crystallization ages [28,29,30]. The Sr-Nd, Pb, δ18O, and δ13C isotopes of eclogites and their wall rocks were consistent with those of the SCB, indicating that they were developed from SCB rocks [28,29,30,31]. The subducted SCB underwent peak metamorphism at ~235 Ma, followed by fast exhumation, and finally returned to the bottom of the crust in the late Triassic [30,32,33]. During the dome-shaped uplift of the Early Cretaceous, large volumes of HP-UHP rocks overlying the ND unit during the syn-collisional stage were eroded and transferred to the surrounding basins, resulting in migmatic and magmatic rocks that widely exposed on the surface [34,35]. The HP-UHP eclogite unit and the Susong complex unit were rebuilt and distributed in the southeastern part of the Dabie Orogen.

Figure 1.

Sketch geological map showing the general distributions of Precambrian rocks within the South China Block (after Zhao and Cawood [36]) (a) and the Dabie Orogen (b). Geological map of the NDO and sampling location (c). In Figure 1a, the solid line is the fault and the dashed line is the buried fault. CAOB: Central Asian Orogenic Belt; CCOB: Central China Orogenic Belt; 1. Cretaceous. 2. Jurassic. 3. Volcanic rocks. 4. Early Cretaceous intrusions. 5. Foziling Group. 6. Luzhenguan Group. 7. Normal fault. 8. Strike-slip fault. 9. Metamorphic foliation. 10. Sampling location.

The BH unit is mainly composed of the Foziling Group, the Luzhenguan Group, and a small amount of Carboniferous strata [27], with a small amount of Early Paleozoic arc-like magmatic rocks remaining in the Foziling Group [37]. The Foziling Group is mainly composed of slate, phyllite, mica schist, quartzite, and marble, and has undergone greenschist facies metamorphism. There is a significant ~450 Ma age cluster in the detrital zircon age frequency distributions of the Foziling Group, and it is generally believed to have been formed as a Devonian flysch sedimentary sequence related to the subduction of the Palaeo-Tethys ocean [27,37,38]. The Carboniferous strata (Meishan Group) are mainly composed of conglomerates, feldspar sandstones, siltstones, and silty mudstones, with coal-bearing rocks interbedded at the bottom without significant metamorphism [27]. The formation of the BH unit was generally believed to be a product of shallower subduction [25,39] or accretion during the subduction stage [26].

The Luzhenguan Group is mainly exposed in the eastern part of the BH unit (Figure 1), which consists of a complex made of orthogneisses and metamorphic sedimentary rocks. These orthogneisses are mainly composed of granitic gneiss (Figure 2a), monzogranitic gneiss (Figure 2b), amphibolite (Figure 2c), some granodioritic gneisses and a small amount of mica schist. Their protoliths are mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks with formation ages of 800–700 Ma [17,20,24], indicating past Triassic epidote amphibolite facies metamorphism [25,26,39]. Most orthogneisses of the Luzhenguan Group were weakly deformed with steep NNE-dipping foliation. Strong deformation zones occurred locally, causing the development of mylonites with an augen structure. The mylonitic foliations are mainly NE-dipping near the Xiaotian-Mozitan Fault, with a dominant dip of about 30°, while those far away from the fault are mainly S- or N-dipping. Stretching lineations in these mylonites dominantly plunge towards to NW or SE. Macroscopic asymmetric folds and S-C structures in the outcrop indicate a top-to-the-NW shear sense. Relatively, the deformation of the Foziling Group is significantly stronger, with NE-dipping foliation and NW-plunging lineation. The Luzhenguan and the Foziling Groups usually exhibit fault contacts, with the contacts’ location being a fault fracture zone and strongly weathered.

Figure 2.

Field and microscopic photographs of orthogneisses in the NDO. (a) Monzogranitic gneiss, with an Early Cretaceous brittle–ductile fault developed. (b) Granitic gneiss, with garnet and biotite. (c) Amphibolite coexisting with granitic gneiss. (d) Microscopic photographs of monzogranitic gneiss. (e) Microscopic photographs of granitic gneiss. (f) Microscopic photographs of amphibolite. These images were taken under cross-polarizers. Qz: quartz, Ms: muscovite, Bt: biotite, Fsp: feldspar, and Amp: amphibolite.

The selected samples for this study are orthogneisses from the Luzhenguan Group, of which D1 and D5 are amphibolites collected from the Hepeng area, D7 is the granitic gneiss and D8 is the monzogranitic gneiss from the Huoshan area (Figure 1). The mineral assemblage of the sample D7 is quartz + plagioclase + K-feldspar + biotite + garnet. Garnets in rocks mostly exist as aggregates, with grain sizes of ~5 mm, and the largest ones can be up to 8–9 mm (Figure 2a). Quartz is characterized by irregular shapes with general grain sizes ~200 μm. Feldspar in the rock is mainly made of plagioclase and a few K-feldspars, with grain sizes mostly greater than 500 μm, where polysynthetic twins are developed in plagioclase. The mineral assemblage of the sample D8 is mainly quartz + plagioclase + K-feldspar + muscovite, and a small amount of biotite. Minerals in the rock are mainly composed of xenomorphic grains that are not significantly oriented (Figure 2d,e). Quartz has a general grain size in the range of 200–300 μm and characterized by irregular shapes. Feldspar is significantly larger, usually greater than 500 μm, with lattice twins developed in K-feldspar and polysynthetic twins in plagioclase. Smaller sized amphibolites are exposed on the outcrop, which is usually mixed with granitic gneiss. The mineral assemblage of amphibolite is mainly plagioclase + amphibole. The minerals exhibit a subhedral or xenomorphic shape, with grain sizes mostly ~600 μm. The amphibolites show significantly weathering, which may have been caused by later fluid metasomatism.

3. Analytical Methods

Zircon separation and whole-rock powders were obtained at the Langfang Chengxin Geological Service Co., Ltd., Langfang, China. Zircons were separated using standard magnetic and heavy liquid separation techniques, as well as handpicking under a binocular microscope. The whole-rock powders analyzed were obtained by crushing fresh rock samples in an agate mortar to yield 200-mesh powders.

3.1. Zircon LA-ICP-MS U-Pb Geochronology

A total of 200 zircons from each sample were mounted on adhesive tape before being enclosed in epoxy resin. After polishing to around half their original thickness, the internal structures of these zircons were examined under cathodoluminescence (CL) using a JXA-8100 electron microprobe (JEOL Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a CL3 + CL detector (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA, USA).

Zircon U-Th-Pb data were obtained using laser ablation followed by inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China. The analyses were conducted using an Agilent 7500a ICP-MS apparatus (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a 193 nm GeoLas 2005 laser. The analyses were carried out with a laser beam diameter of 32 μm. Each analysis includes background collection for 20–30 s (gas blank), followed by data collection from the sample for 50 s. Zircon 91500 was used as an external standard for calibration. Zircon standards GJ-1 and SK10-2 were used as the secondary standard and analyzed to correct mass discrimination. The methodology employed here was the same as that described by Liu et al. [40], with uncertainties on individual analyses quoted at the 1σ level. We employed the approach outlined by Andersen [41] for common Pb corrections. The resulting data were calculated using the ICP-MS-Data Cal 8.0 and Isoplot 3.14 [42] software packages and are given in Table S1.

3.2. Zircon Lu-Hf Isotope Analyses

Zircon Lu-Hf isotope analysis was conducted using a Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Gemany) coupled plasma mass spectrometer equipped with a GeoLas 2005 laser (LA-MC-ICP-MS) at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China. This analysis used a 44 μm spot size with an applied energy density of 5.3 J/cm2. Standard 91500 (reference value: 176Hf/177Hf = 0.282308 ± 0.0000040) and GJ1 (reference value: 176Hf/177Hf = 0.282021 ± 0.000011) zircons were reanalyzed as unknowns to verify the data’s quality during the analysis. Details on the analytical approaches and data-reduction techniques are given by Hu et al. [43]. Initial 176Hf/177Hf ratios and εHf(t) values were calculated at their 206Pb/238U age for each zircon grain. The resulting data were calculated using the ICP-MS-Data Cal 8.0 software [40], and the zircon Lu-Hf isotopic data are given in Table S2.

3.3. Whole-Rock Geochemical Analyses

Whole-rock major and trace element contents were analyzed at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China. Major element concentrations were determined via X-ray fluorescence using a Rigaku RIX 2100 instrument (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Both the analytical precision and accuracy of the analysis are generally around 1%–5%. Trace element and REE concentrations were determined via ICP-MS using an Agilent 7500a instrument. The analytical accuracies are better than ±5%. The analytical procedure was described in detailed by Liu et al. [40].

4. Analytical Results

4.1. Zircon LA-ICP-MS U-Pb Ages

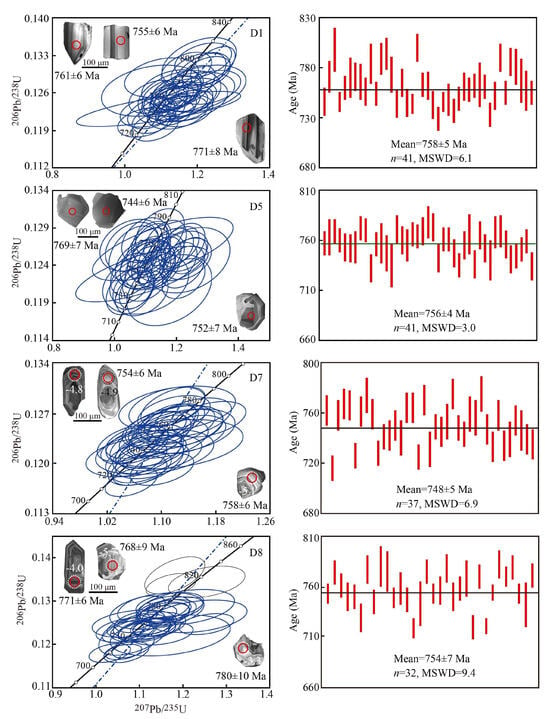

In this study, four samples (D1, D5, D7, and D8) were collected to perform zircon LA-ICP-MS U-Pb dating. Samples D1 and D5 are amphibolites, while the others are gneisses. Zircons in D1 and D5 were abraded and rounded shapes with a size range of ~200 μm (Figure 3). Based on the CL images, zircons exhibit clear oscillatory zoning, and their high Th/U ratios of >0.1 (Table S1) indicate that these zircons are magmatic [44]. A total of 41 Neoproterozoic 206Pb/238U ages with concordance values of 90%–100% were obtained for each sample, yielding weighted mean ages of 758 ± 5 Ma for D1 and 756 ± 4 Ma for D5 (Figure 3). The mean squared weighted deviations (MSWDs) are 6.1 and 3.0, respectively.

Figure 3.

Concordia diagrams and weighted mean U-Pb ages for zircons from gneisses in the NDO. The insert are cathodoluminescence images of a selection of dated zircons. Red circles show the locations of zircon U-Pb analyses and white dotted circles indicate the locations of zircon Lu-Hf isotope analyses. The data represented by the black line were not included in the calculation of the weighted mean age.

Zircons in D7 and D8 were abraded and rounded or short prisms in the size range of 100–200 μm (Figure 3). Based on the CL images, zircons exhibit clear oscillatory zoning, with high Th/U ratios of >0.1 (Table S1), indicating that these zircons are magmatic [44]. More than 32 Neoproterozoic 206Pb/238U ages with concordance values of 90%–100% were obtained for each sample, yielding weighted mean ages of 748 ± 5 Ma for D7 and 754 ± 7 Ma for D8 (Figure 3). The mean squared weighted deviations (MSWDs) are 6.9 and 9.4, respectively.

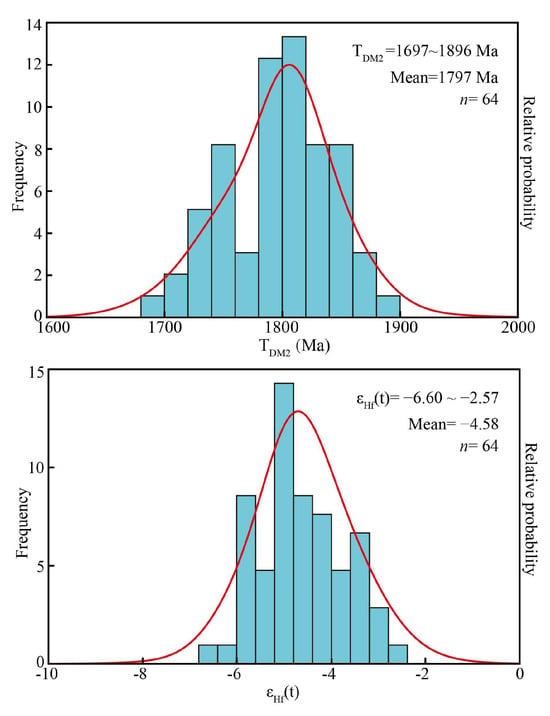

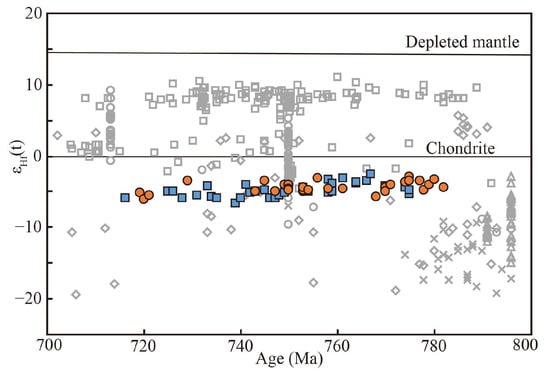

4.2. Zircon Lu-Hf Analysis

In this study, samples D7 and D8 were collected to perform zircon Lu-Hf isotope analyses. These analyses were conducted on the same grain as that for the LA-ICP-MS U-Pb dating ananlysis. A total of 64 Lu-Hf isotope analyses were performed on zircons from samples D7 and D8. Most have relatively consistent initial 176Hf/177Hf values (0.282143–0.282255), with negative εHf(t) values ranging from −6.60 to −2.57 and a weighted mean value of −4.58 (Figure 4), two-stage Hf model ages (TDM2(Hf)) from 1896 to 1697 Ma and a weighted mean age of 1797 Ma (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Diagram showing zircon TDM2(Hf) and εHf(t) values for granitic gneisses in the NDO.

4.3. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Element Compositions

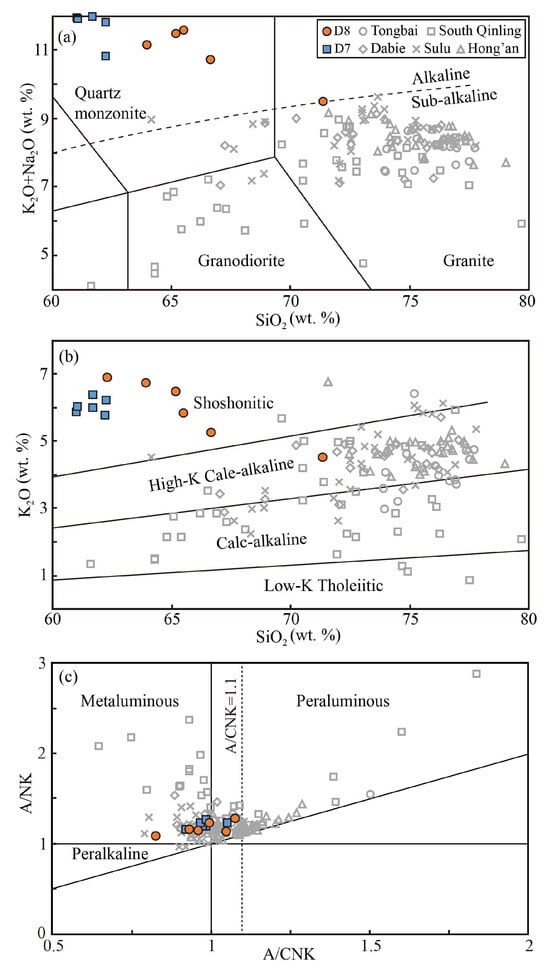

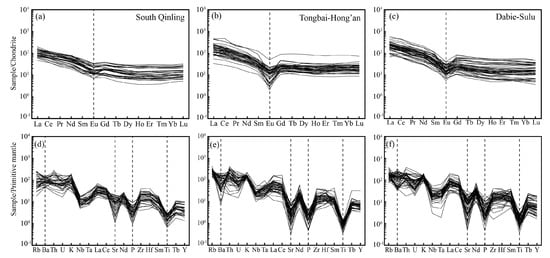

The selected samples for this study are granitic gneisses (D7-1–D7-6) and monzogranitic gneisses (D8-1–D8-6). They contain relatively low SiO2 (60.0–65.8 wt.% except 70.6 wt.% of D8-2), TiO2 (0.28–0.89 wt.%), FeOT (1.68–3.39 wt.%), CaO (0.60–2.64 wt.%), and MgO (0.15–1.26 wt.%) and high Al2O3 (14.7–19.5 wt.%), and Na2O + K2O (9.51–12.5 wt.%) contents (Table 1). The majority of these samples are classified as an alkaline field on a SiO2 vs. K2O + Na2O diagram (Figure 5a) and a shoshonitic field of an SiO2 vs. K2O diagram (Figure 5b). The A/CNK values range from 0.83 to 1.08, suggesting a metaluminous to weakly peraluminous composition (Figure 5c). The (Na2O + K2O)/Al2O3 values are relatively low, ranging from 0.59 to 0.68, and the FeOT/MgO values range from 3.73 to 15.4.

Figure 5.

(a) TAS diagram (after Middlemost [45]); (b) K2O vs. SiO2 diagram (after Rickwood [46]); (c) A/NK vs. A/CNK diagram (after Maniar et al. [47]) for the granite gneisses in the NDO. The legends for subfigures (b,c) are the same as those for subfigure (a). Data of the South Qinling are from Wu et al. [48], Wang et al. [49], and the references therein. Data of the Tongbai Orogen are from Qiu et al. [50]. Data of the Hong’an Orogen are from Xu et al. [51] and Chen et al. [52]. Data of the Dabie Orogen are from Li et al. [53], Tuo et al. [54], and Chen et al. [52]. Data of the Sulu Orogen are from He et al. [55], Wang et al. [56], and the references therein.

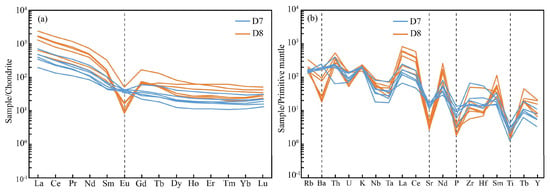

The chondrite-normalized rare earth element (REE) shows that these samples are enriched in light rare earth elements (ΣLREEs = 190–2073 ppm) and depleted in heavy rare earth elements (ΣHREEs = 28.5–176 ppm), with (La/Yb)N = 8.90–79.5 and (La/Sm)N = 4.42–10.4 (Table 1). Sample D7 exhibits no significant anomalies of Eu*, ranging from 0.08 to 0.24, while sample D8 shows strong negative anomalies of Eu*, ranging from 0.53 to 1.25. These rock samples are enriched in La, Ce, Th, K, Zr, Nd, and Sm, depleted in Nb, Ta, P, Ti, Sr in the primitive mantle-normalized trace element diagram (Figure 6). In contrast, sample D8 is depleted in Ba, while D7 shows weak enrichment.

Figure 6.

Chondrite-normalized rare earth element (REE) diagram (a) and primitive mantle normalized multi-element variation diagram (b) for samples from the NDO.

Table 1.

Whole-rock major and trace element compositions of samples from the NDO.

Table 1.

Whole-rock major and trace element compositions of samples from the NDO.

| Samples | D7-1 | D7-2 | D7-3 | D7-4 | D7-5 | D7-6 | D8-1 | D8-2 | D8-3 | D8-4 | D8-5 | D8-6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major elements (wt.%) | ||||||||||||

| SiO2 | 61.5 | 60.9 | 61.4 | 60.1 | 60.6 | 60.0 | 65.8 | 70.6 | 63.7 | 63.6 | 63.0 | 60.9 |

| TiO2 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.28 | 0.65 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.51 |

| Al2O3 | 18.2 | 19.2 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 19.2 | 19.5 | 17.9 | 14.7 | 16.6 | 17.2 | 18.3 | 18.6 |

| FeOT | 4.43 | 3.42 | 2.93 | 3.30 | 2.99 | 3.07 | 1.68 | 2.73 | 2.31 | 2.61 | 2.95 | 3.39 |

| MnO | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.15 |

| MgO | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 1.26 | 0.29 |

| CaO | 2.28 | 1.87 | 1.49 | 2.01 | 2.36 | 2.34 | 1.90 | 0.60 | 2.64 | 1.97 | 1.47 | 1.72 |

| Na2O | 4.96 | 5.87 | 5.49 | 5.98 | 5.92 | 5.75 | 5.36 | 4.91 | 5.58 | 4.86 | 4.31 | 5.42 |

| K2O | 5.74 | 5.97 | 6.17 | 5.82 | 6.32 | 5.96 | 5.23 | 4.50 | 5.71 | 6.36 | 6.68 | 6.78 |

| P2O5 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| LOI | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.45 | 1.33 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 2.55 | 2.15 | 1.19 | 1.99 |

| Total | 98.8 | 98.7 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 98.3 | 98.4 | 98.8 | 99.0 | 97.2 | 97.6 | 98.6 | 97.8 |

| A/CNK | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 1.08 | 0.96 |

| A/NK | 1.27 | 1.19 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 1.23 | 1.24 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.16 | 1.28 | 1.14 |

| K2O + Na2O | 10.8 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 11.9 | 10.7 | 9.51 | 11.6 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 12.5 |

| (K2O + Na2O)/Al2O3 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.66 |

| FeOT/MgO | 4.92 | 4.44 | 4.07 | 4.71 | 7.12 | 4.51 | 3.73 | 5.46 | 15.4 | 10.4 | 2.34 | 11.7 |

| Trace and rare earth elements (ppm) | ||||||||||||

| Ba | 1359 | 1251 | 1292 | 1251 | 1170 | 1666 | 657 | 541 | 183 | 153 | 1107 | 127 |

| Rb | 94.3 | 83.3 | 99.2 | 104 | 91.2 | 95.4 | 125 | 94.1 | 86.1 | 112 | 204 | 117 |

| Sr | 349 | 290 | 240 | 273 | 294 | 362 | 70.9 | 56.4 | 98.6 | 72.7 | 59.2 | 55.1 |

| Zr | 734 | 257 | 223 | 168 | 159 | 172 | 559 | 62.1 | 139 | 206 | 105 | 127 |

| Nb | 25.9 | 23.0 | 31.4 | 57.3 | 13.0 | 32.3 | 47.6 | 34.8 | 38.4 | 33.0 | 60.6 | 42.2 |

| Ni | 2.29 | — | 0.24 | 2.61 | 0.09 | 2.00 | 1.53 | 0.52 | — | — | — | — |

| Co | 3.89 | 2.86 | 4.31 | 5.93 | 2.33 | 4.44 | 1.63 | 5.76 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 3.56 | 0.97 |

| Zn | 83.5 | 48.6 | 93.4 | 164 | 52.4 | 86.4 | 16.4 | 21.3 | 30.4 | 71.1 | 37.9 | 64.7 |

| Cr | 13.8 | 9.03 | 9.65 | 11.7 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 7.78 | 7.31 | 4.50 | 6.98 | 5.67 | 7.11 |

| La | 114 | 80.4 | 114 | 164 | 93.4 | 46.5 | 151 | 563 | 390 | 411 | 115 | 301 |

| Ce | 197 | 136 | 197 | 280 | 148 | 84.1 | 281 | 998 | 653 | 692 | 208 | 500 |

| Pr | 19.9 | 15.9 | 22.4 | 32.4 | 16.7 | 10.5 | 28.3 | 110 | 70.0 | 76.8 | 22.9 | 54.8 |

| Nd | 67.2 | 52.4 | 73.0 | 108 | 50.0 | 39.1 | 92.9 | 348 | 220 | 238 | 73.3 | 179 |

| Sm | 10.4 | 7.86 | 9.65 | 15.3 | 6.57 | 6.80 | 15.8 | 50.0 | 24.2 | 25.6 | 11.9 | 20.9 |

| Eu | 2.51 | 2.25 | 1.93 | 2.42 | 2.13 | 2.54 | 0.99 | 2.92 | 0.49 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 0.55 |

| Gd | 8.20 | 6.20 | 7.28 | 12.6 | 4.63 | 5.68 | 13.3 | 33.6 | 14.3 | 15.6 | 12.3 | 13.9 |

| Tb | 1.21 | 0.97 | 1.12 | 2.01 | 0.69 | 0.93 | 2.12 | 4.93 | 1.93 | 2.10 | 2.48 | 1.96 |

| Dy | 6.81 | 5.04 | 5.41 | 10.4 | 3.24 | 4.77 | 12.7 | 20.9 | 7.39 | 8.30 | 15.6 | 8.60 |

| Ho | 1.34 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 2.07 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 2.49 | 3.65 | 1.44 | 1.59 | 3.44 | 1.56 |

| Er | 3.65 | 3.05 | 3.07 | 5.51 | 1.89 | 2.76 | 6.92 | 9.34 | 3.96 | 4.83 | 10.1 | 4.40 |

| Tm | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.82 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.99 | 1.18 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 1.55 | 0.59 |

| Yb | 3.53 | 3.20 | 2.78 | 5.00 | 1.91 | 2.55 | 6.31 | 7.16 | 3.52 | 4.33 | 9.29 | 3.98 |

| Lu | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.77 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.90 | 1.05 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 1.31 | 0.68 |

| Y | 36.5 | 25.6 | 26.1 | 49.7 | 14.9 | 25.1 | 70.3 | 93.9 | 30.0 | 36.2 | 88.9 | 37.2 |

| Cs | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.30 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.99 | 1.65 | 1.12 | 2.77 |

| Ta | 0.93 | 1.12 | 1.59 | 3.00 | 0.71 | 1.48 | 2.11 | 1.93 | 1.31 | 1.03 | 2.88 | 1.34 |

| Hf | 17.0 | 7.34 | 4.63 | 3.68 | 4.49 | 4.24 | 14.5 | 2.15 | 2.78 | 3.61 | 2.71 | 2.52 |

| Li | 5.90 | 5.95 | 9.70 | 11.4 | 4.48 | 7.42 | 6.97 | 6.84 | 4.01 | 8.01 | 8.82 | 7.48 |

| Be | 2.28 | 1.61 | 1.43 | 1.59 | 1.78 | 1.61 | 3.55 | 1.58 | 1.18 | 0.96 | 3.62 | 0.97 |

| Sc | 4.65 | 5.50 | 5.67 | 9.73 | 2.75 | 5.11 | 4.66 | 8.57 | 10.1 | 13.1 | 5.24 | 17.0 |

| V | 26.8 | 22.1 | 30.7 | 30.2 | 14.3 | 33.6 | 8.01 | 10.5 | 3.57 | 4.05 | 10.8 | 4.18 |

| Cu | 3.89 | 10.8 | 4.50 | 2.44 | 1.83 | 4.79 | 2.22 | 4.26 | 1.02 | 1.76 | 1.29 | 1.53 |

| Ga | 26.7 | 26.1 | 28.6 | 31.0 | 25.6 | 24.2 | 25.0 | 42.3 | 35.1 | 36.5 | 26.7 | 32.6 |

| Mo | — | 1.67 | 1.97 | 0.99 | 2.21 | 0.90 | — | 8.45 | 1.71 | 1.64 | 0.22 | 0.87 |

| Cd | — | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.09 | — | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| In | — | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.05 | — | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.18 |

| Sn | 1.21 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 1.06 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 3.05 | 2.37 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 2.55 | 0.67 |

| Sb | — | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | — | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.21 |

| Te | — | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 | — | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| W | — | 0.25 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.28 | — | 0.63 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.39 |

| Tl | — | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.39 | — | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.82 | 0.49 |

| Pb | 21.6 | 23.8 | 21.6 | 18.2 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 6.04 | 8.16 | 16.5 | 16.8 | 5.11 | 14.0 |

| Bi | — | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | — | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Th | 16.4 | 19.4 | 20.3 | 32.8 | 18.9 | 5.33 | 32.5 | 22.6 | 28.9 | 29.0 | 43.4 | 20.9 |

| U | 2.71 | 2.86 | 1.83 | 2.00 | 1.58 | 1.48 | 2.96 | 2.90 | 1.13 | 1.30 | 2.72 | 1.10 |

| Zr + Nb + Ce + Y | 993 | 442 | 477 | 555 | 335 | 313 | 958 | 1189 | 860 | 967 | 463 | 707 |

| 10,000 × Ga/Al | 2.73 | 2.53 | 2.75 | 2.99 | 2.48 | 2.31 | 2.61 | 5.37 | 3.88 | 3.91 | 2.72 | 3.24 |

| Y + Nb | 62.4 | 57.5 | 107 | 27.9 | 57.4 | 48.6 | 118 | 129 | 68.4 | 69.2 | 150 | 79.4 |

| Yb + Ta | 4.46 | 4.32 | 4.37 | 8.00 | 2.62 | 4.03 | 8.42 | 9.09 | 4.83 | 5.36 | 12.2 | 5.32 |

| ΣREE | 473 | 466 | 691 | 346 | 233 | 341 | 686 | 2249 | 1422 | 1518 | 577 | 1130 |

| ΣLREE | 411 | 418 | 602 | 317 | 190 | 294 | 570 | 2073 | 1358 | 1444 | 432 | 1057 |

| ΣHREE | 62.3 | 47.7 | 88.9 | 28.5 | 43.6 | 46.1 | 116 | 176 | 63.6 | 74.3 | 145 | 72.9 |

| (La/Yb)N | 23.2 | 29.5 | 23.5 | 35.1 | 13.1 | 18.0 | 17.2 | 56.5 | 79.5 | 68.2 | 8.90 | 54.2 |

| (La/Sm)N | 7.08 | 7.66 | 6.94 | 9.18 | 4.42 | 6.60 | 6.17 | 7.28 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 6.24 | 9.29 |

| (Gd/Yb)N | 1.92 | 2.16 | 2.08 | 2.00 | 1.85 | 1.61 | 1.74 | 3.88 | 3.35 | 2.98 | 1.10 | 2.88 |

| Eu* | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 1.18 | 1.25 | 0.99 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.10 |

Eu* = EuN/(SmN × GdN)1/2; A/CNK = molar Al2O3/(CaO + Na2O + K2O); A/NK = molar Al2O3/(Na2O + K2O); N denotes the chondrite-normalized values of Sun and McDonough [57].

5. Discussion

5.1. Petrologic Genesis and Tectonic Setting

The period range of ~830–740 Ma was a prominent period of widespread magmatism in the SCB, corresponding to rift magmatic activity during the break-up of the Rodinia supercontinent [4,10,21,22,58]. The intrusion time of granitic gneisses in the NDO is ~750 Ma, which is consistent with the intrusion time of the coexisting mafic rocks, indicating that the protolith of these gneisses should have formed during the mid-Neoproterozoic bimodal magmatism [21,22,23,24].

The A/CNK values of these rock samples are relatively low (0.83–1.08), indicating that they belong to a metaluminous to weakly peraluminous series, and their Na2O content is high, which is different from typical S-type granite [59]. Although muscovites or garnets are more typical of S-type granites, highly fractionated I-type granites may contain a few these minerals. Therefore, muscovites and garnets are not effective indicators for identifying S-type granites [60,61]. A-type granites are generally characterized by depletions in Ba, Sr, P, and Ti, with significantly negative Eu anomalies, and high Zr, Nb, Ce, and Y contents due to their alkali rich properties [59,61,62,63]. Relatively, I-type granites are characterized by weak negative anomalies or no anomalies. Samples D8-1~D8-6 exhibit significant negative Eu anomalies, with depletions in Ba, Sr, P, and Ti, and should be classified as A-type granite; samples D7-1~D7-6 show no significant negative Eu anomaly, with weak enrichment of Ba, and its characteristics are similar to those of I-type granite or I-A transition-type rocks. Based on the compilation of trace elements in the northern Yangtze Block, the mid-Neoproterozoic granites in any area of the Qinling–Tongbai–Hong’an–Dabie orogenic belt and the Sulu Orogen exhibit the coexistence of I-type and A-type granites (Figure 7). This was usually explained as the remelting of the former arc-like magmatic rocks [5,17,23], resulting in rocks exhibiting both arc-like and rift magmatism geochemical characteristics.

Figure 7.

(a–c) Summary of chondrite-normalized REE diagram and (d–f) primitive mantle normalized multi-element variation diagram from the South Qinling, Tongbai-Hong’an, and Dabie-Sulu orogens, respectively. Data of the South Qinling, Tongbai, Hong’an, Dabie, and Sulu orogens are from the same references as those in Figure 5.

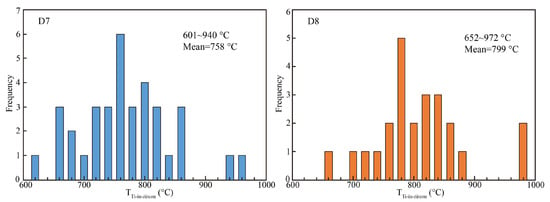

A-type granite usually has a relatively high crystallization temperature (>800 °C) [64]. The distribution of Ti in zircon is mainly controlled by temperature, whose elucidation resulted in the development of the Ti-in-zircon geothermometer [65]. The TTi-in-zircon values of sample D7 mainly range from 660 °C to 940 °C with a mean temperature of 758 °C, while those of sample D8 mainly range from 700 °C to 880 °C with a mean temperature of 799 °C (Figure 8), indicating that these rocks were formed in a relatively high-temperature melting condition. This is consistent with the conclusion that those Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks were formed as coexistence of I-type and A-type granites.

Figure 8.

TTi-in-zircon values of gneiss samples from the NDO.

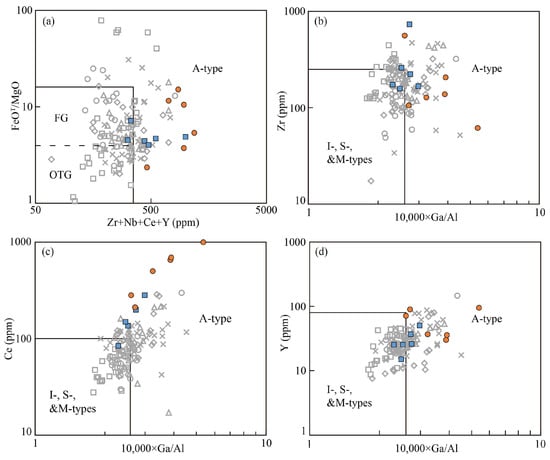

The Ga/Al ratio is the most effective metric for distinguishing A-type granite [62]. The 10,000 × Ga/Al values of these granitic gneisses in the NDO range from 2.31 to 5.37 and are mostly more than 2.6. In the 10,000 × Ga/Al vs. Zr, Ce, and Y diagram, these elements are mainly plotted in the field of the A-type granite region (Figure 9). The Zr + Nb + Ce + Y values of these samples range from 313 × 10−6 to 1189 × 10−6 and are mostly greater than 350 × 10−6. In the (Zr + Nb + Ce + Y) vs. FeOT/MgO diagram, these elements are also mainly plotted in the field of A-type granite (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

(a) (Zr + Nb + Ce + Y) vs. FeOT/MgO; (b) 10,000 × Ga/Al vs. Zr; (c) 10,000 × Ga/Al vs. Ce, and (d) 10,000 × Ga/Al vs. Y diagrams (after Whalen et al. [62]). Data of the South Qinling, Tongbai, Hong’an, Dabie, and Sulu orogens are from the same references as those in Figure 5. Legend symbols are the same as those in Figure 5.

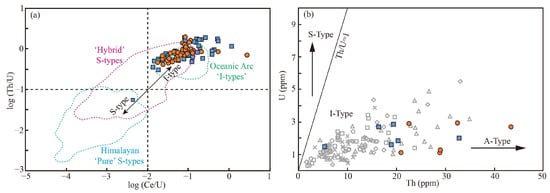

Generally, A-type granite has a high Th concentration, while S-type granite has a high U concentration, and I-type granite has a moderate concentration. Additionally, the Th/U valuse of A-type and I-type granites are generally greater than 1, while those of S-type granites may exhibit both Th/U > 1 and Th/U < 1. Therefore, the whole-rock Th and U contents of these samples can be used to distinguish granite types [63]. In the log (Ce/U) vs. log (Th/U) diagram, all the log (Ce/U) values of these samples are greater than −2, indicating that they are not S-type granite. In the Th vs. U diagram, all data points are located to the right of the Th/U = 1 line (Figure 10), indicating that the rock is not a S-type granite, but more in line with the characteristics of an A-type granite.

Figure 10.

Diagram of (a) zircon log(Ce/U) vs. log(Th/U)(Ce/U) vs. log (after Roberts et al. [66]) and (b) whole rock Th vs. U concentrations (after Regelous et al. [63]). Data of the South Qinling, Tongbai, Hong’an, Dabie, and Sulu orogens are from the same references as those in Figure 5. Legend symbols are the same as those in Figure 5.

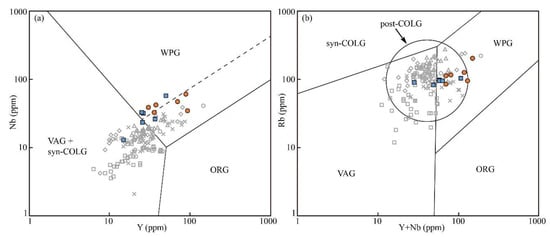

I-Type granite development was usually associated with subduction, while A-type granite is mainly produced in an intraplate tectonic or post-collisional setting [63,66]. The strong enrichment of large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs) and LREEs, as well as the negative anomalies of P and high-field-strength elements (HFSEs), is a common feature of the trace element distribution in the continental crust, typically indicating the geochemical characteristics of subduction-related magma [67]. The mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks in the NDO exhibit strong LREE enrichment and P and HFSE (Ba and Nb) depletion, demonstrating the characteristics of arc-like magmatic rocks. Previous studies have also shown that the mid-Neoproterozoic granites, which serves as protolith of HP-UHP eclogites in the Dabie Orogen, were characterized by the coexistence of “arc-like” and “rift” magmatic rocks in geochemical features. It is a product of the remelting of crustal material from the former arc-like magmatic rocks in an extensional setting [23]. In the Y vs. Nb, and (Y + Nb) vs. Rb discrimination diagrams, these samples all fall into both the WPG and VAG field (Figure 11), indicating that they were formed in a post-collisional tectonic setting, which is consistent with the evolution history of the mid-Neoproterozoic rift activity that occurred in the northern Yangtze Block.

5.2. Implication for the Neoproterozoic Tectono-Magmatic Evolution

The diffusion rate of oxygen in zircon is very low [69]. Under metamorphic conditions from greenschist to low amphibolite facies, zircon is almost unaffected by hydrothermal alteration and metamorphism, effectively preserving its original oxygen isotope information. The δ18O value of the mantle is 5.3 ± 0.6 ‰. Rocks derived from the mantle exhibit an oxygen isotope ratio close to this value. The δ18O value of zircons crystallized from igneous rocks differentiated from mantle-derived magma is close to the δ18O value of the mantle. If the oxygen isotope ratio of magma is lower than this value, the production of magma may be result of crustal rocks that have undergone high-temperature hydrothermal alteration, which maybe occur between oceanic crust rocks and high-temperature seawater or between continental crust rocks and atmospheric precipitation [21]. The Luzhenguan Group on the NDO has mainly undergone low-amphibolite facies metamorphism, and its low δ18O values were usually explained by the high-temperature meteoric-hydrothermal alteration during Neoproterozoic syn-rift magmatism [5,21,22,31,70]. The development of inhomogeneous δ18O values within these magmatic rocks may be related to the heterogeneity of hydrothermal alterations at different scales.

The break-up of the Rodinia supercontinent caused extensive mid-Neoproterozoic magmatism in the Yangtze Block, which mainly from ~830 to 740 Ma [4,10,20,21,58]. The syn-rift magmatism in the Jiangnan Orogen, located on the southeastern flank of the Yangtze Block, mainly occurred at ~780 Ma, with positive zircon εHf(t) values and two-stage Hf model ages ranging from 1.12 to 1.21 Ga and exhibiting trace element characteristics similar to those of arc-like magmatic rocks [6]. In the Dabie Orogen on the northeastern Yangtze Block, the syn-rift magmatism mainly occurred ~750 Ma [20,21,24,30]. The two-stage Hf model ages of mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks with positive εHf(t) values are mostly between 0.82 and 1.24 Ga, while the two-stage Hf model ages of those with negative εHf(t) values are ~1.82 Ga [30]. Recently, mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks with negative εHf(t) values and two-stage Hf model ages of 2.3–1.8 Ga been discovered in the Dabie Orogen [53], as well as a large number of magmatic rocks formed in the Neoarchean–Paleoproterozoic [71,72,73]. This study shows that the mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks on the NDO are characterized by negative εHf(t) values and two-stage Hf model ages of ~1.8 Ga (Figure 6) and εHf(t) values of ~−4.58 (Figure 4 and Figure 12), and these rocks may have been formed from the remelting of the juvenile crust related to the evolution of the Columbia supercontinent. The Zhangbaling tectonic belt [74,75] and the Sulu Orogen [55], both located on the northeastern Yangtze Block, are composed of developed mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks formed by the remelting of the Neoarchean–Paleoproterozoic crust. Based on these results, it can be concluded that the formation mechanism of the mid-Neoproterozoic magmatic rocks in the northern Yangtze Block is more complex than that in the southeastern region. The subduction of the oceanic plate on the western and northern Yangtze Block at 1.3–1.1 Ma, resulting in the development of large-scale arc-like magmatic rocks and the growth of the juvenile crust. After a prolonged orogenic evolution period, the crust may have transformed into an intraplate extensional setting no later than 790 Ma [17,53,55]. After the subduction of the oceanic plate, a complex arc-continent collision occurred and resulted in the mixed development of the Neoarchean–Paleoproterozoic and late Mesoproterozoic crusts in the northern Yangtze Block. Eventually, magmatic rocks with different two-stage Hf model ages were formed during the mid-Neoproterozoic syn-rift magmatism.

Figure 12.

Summary of εHf(t) data from the northern Yangtze Block. Data of the South Qinling are from Wu et al. [48], and the references therein. Data of the Tongbai Orogen are from Zhang et al. [76], and the references therein. Data of the Hong’an Orogen are from Xu et al. [51]. Data of the Dabie Orogen are from Zheng et al. [26,30] and Dai et al. [77]. Data of the Sulu Orogen are from He et al. [78], Zhao et al. [79], and the references therein. Legend symbols are the same as those in Figure 5.

Although the mid-Neoproterozoic rocks in the northern Yangtze Block are formed by the remelting of rocks from different ages, they all exhibit the characteristics of a heterogeneous δ18O distribution [5,6,20,21,26,30,48,76,77,79,80], indicating that these low δ18O features may not have been inherited from the Neoarchean–Paleoproterozoic and late Mesoproterozoic crusts but are more likely to have been caused by the high-temperature meteoric-hydrothermal alteration during the syn-rift magmatism.

6. Conclusions

(1) The intrusion time of Neoproterozoic granitic and mafic rocks in the NDO is ~750 Ma, with εHf(t) values ranging from −6.60 to −2.57 and a two-stage Hf model age of ~1.8 Ga, indicating that they were developed from the remelting of the Paleoproterozoic juvenile crust.

(2) Geochemical analysis shows that these mid-Neoproterozoic granitic rocks in the NDO are enriched in LREEs and depleted in HREEs, with (La/Yb)N = 8.90–79.5. These rocks are enriched in La, Ce, Th, K, Zr, Nd, and Sm and depleted in Nb, Ta, P, Ti, and Sr, with negative Eu anomaly or no distinct Eu in the primitive mantle-normalized trace element diagram. These mid-Neoproterozoic granitic rocks are A-type granites displaying both arc-like and rift magmatism characteristics.

(3) The two-stage Hf model ages of mid-Neoproterozoic granitic rocks in the NDO are varied, indicating the remelting of rocks from different ages. However, these rocks all show a heterogeneous δ18O distribution, indicating that low δ18O content was likely resulted from the high-temperature meteoric-hydrothermal alteration during the syn-rift magmatism.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min15121323/s1, Table S1: Zircon LA-ICP-MS U-Pb ages; Table S2: Lu-Hf isotopic analysis results of the granitic gneiss in the northern Dabie Orogen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.; Methodology, Q.B. and L.M.; Software, Q.B. and X.Z.; Investigation, Q.B., Y.W., L.M., X.Z. and S.Z.; Resources, Y.W.; Writing—original draft, Q.B.; Writing—review and editing, Y.W.; Project administration, Y.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 42272240 and 42472268).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge reviewers for their constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hoffman, P.F.; Abbot, D.S.; Ashkenazy, Y.; Benn, D.I.; Brocks, J.J.; Cohen, P.A.; Cox, G.M.; Creveling, J.R.; Donnadieu, Y.; Erwin, D.H.; et al. Snowball Earth climate dynamics and Cryogenian geology-geobiology. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1600983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.F.; Kaufman, A.J.; Halverson, G.P.; Schrag, D.P. A Neoproterozoic snowball earth. Science 1998, 281, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Bogdanova, S.V.; Collins, A.S.; Davidson, A.; De Waele, B.; Ernst, R.E.; Fitzsimons, I.C.W.; Fuck, R.A.; Gladkochub, D.P.; Jacobs, J.; et al. Assembly, configuration, and break-up history of Rodinia: A synthesis. Precambrian Res. 2008, 160, 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Li, X.H.; Kinny, P.D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.H.; Zhou, H. Geochronology of Neoproterozoic syn-rift magmatism in the Yangtze craton, South China and correlations with other continents: Evidence for a mantle superplume that broke up Rodinia. Precambrian Res. 2003, 122, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Zhang, S.B.; Zhao, Z.F.; Wu, Y.B.; Li, X.H.; Li, Z.X.; Wu, F.Y. Contrasting zircon Hf and O isotopes in the two episodes of Neoproterozoic granitoids in South China: Implications for growth and reworking of continental crust. Lithos 2007, 96, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Wu, R.X.; Wu, Y.B.; Zhang, S.B.; Yuan, H.L.; Wu, F.Y. Rift melting of juvenile arc-derived crust: Geochemical evidence from Neoproterozoic volcanic and granitic rocks in the Jiangnan Orogen, South China. Precambrian Res. 2008, 163, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.M.; Tucker, R.; Xiao, S.H.; Peng, Z.X.; Yuan, X.L.; Chen, Z. New constraints on the ages of Neoproterozoic glaciations in south China. Geology 2004, 32, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields-Zhou, G.; Och, L. The case for a Neoproterozoic oxygenation event: Geochemical evidence and biological consequences. GSA Today 2011, 21, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, D.G.; Chen, L.; Han, J.; Zhang, X.L. An early Cambrian tunicate from China. Nature 2001, 411, 472–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Zhou, J.C.; Qiu, J.S.; Gao, J.F. Geochemistry of the Meso- to Neoproterozoic basic-acid rocks from Hunan Province, South China: Implications for the evolution of the western Jiangnan orogen. Precambrian Res. 2004, 135, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.F.; Yan, D.P.; Wang, C.L.; Qi, L.; Kennedy, A. Subduction related origin of the 750 Ma Xuelongbao adakitic complex (Sichuan Province, China): Implications for the tectonic setting of the giant Neoproterozoic magmatic event in South China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 248, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.; Xu, Z.Q.; Santosh, M.; Zeng, B. Mid-Neoproterozoic magmatism in the northern margin of the Yangtze Block, South China: Implications for transition from subduction to post-collision. Precambrian Res. 2021, 354, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X.L.; Li, J.Y.; Li, R.C.; Du, D.H.; Jiang, C.H.; Li, L.S.; Ding, N. From arc accretion to within-plate extension: Geochronology and geochemistry of the Neoproterozoic magmatism on the northern margin of the Yangtze Block. Precambrian Res. 2023, 395, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.L.; Shu, L.S.; Santosh, M.; Li, J.Y. Precambrian crustal evolution of the South China Block and its relation to supercontinent history: Constraints from U–Pb ages, Lu–Hf isotopes and REE geochemistry of zircons from sandstones and granodiorite. Precambrian Res. 2012, 208–211, 19–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, W. Neoproterozoic magmatism in the western and northern margins of the Yangtze Block (South China) controlled by slab subduction and subduction-transform-edge-propagator. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 187, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, B.; Dong, Y.P.; Liu, G.; Zhao, H.; Sun, S.S.; Zhang, F.F.; Liu, X.M. Origin of mafic intrusions in the Micangshan Massif, Central China: Implications for the Neoproterozoic tectonic evolution of the northwestern Yangtze Block. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2020, 190, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Wu, Y.B.; Zhang, S.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Song, H.; Xu, Z.Q.; Shi, Z.M. Revisiting Neoproterozoic tectono-magmatic evolution of the northern margin of the Yangtze Block, South China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 255, 104825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wymanc, D.; Li, Z.; Bao, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jian, P.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L. Petrology, geochronology and geochemistry of ca. 780 Ma A-type granites in South China: Petrogenesis and implications for crustal growth during the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia. Precambrian Res. 2010, 178, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.F.; Yan, D.P.; Kennedy, A.K.; Li, Y.Q.; Ding, J. SHRIMP U–Pb zircon geochronological and geochemical evidence for Neoproterozoic arc-magmatism along the western margin of the Yangtze Block, South China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 196, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Wu, Y.B.; Chen, F.K.; Gong, B.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z.F. Zircon U-Pb and oxygen isotope evidence for a large-scale 18O depletion event in igneous rocks during the Neoproterozoic. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 4145–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Tang, J.; Gong, B.; Zhao, Z.F.; Liu, X.M. Zircon U–Pb dating of water–rock interaction during Neoproterozoic rift magmatism in South China. Chem. Geol. 2007, 246, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.N.; Wang, X.C.; Li, Q.L.; Li, X.H. Integrated in situ U–Pb age and Hf–O analyses of zircon from Suixian Group in northern Yangtze: New insights into the Neoproterozoic low-18O magmas in the South China Block. Precambrian Res. 2016, 273, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Qiu, J.S.; Xu, X.S.; Wang, X.L.; Li, Z. Geochronology and geochemistry of gneissic metagranites in eastern Dabie Mountains: Implications for the Neoproterozoic tectono-magmatism along the northeastern margin of the Yangtze Block. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2010, 53, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Zhang, L.M.; Ye, K.; Su, W.; Cheng, N.F. Oxygen isotopes of whole-rock and zircon and zircon U-Pb ages of meta-rhyolite from the Luzhenguan Group and associated meta-granite in the northern Dabie Mountains. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2013, 29, 1511–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Wang, Q.C.; Faure, M.; Arnaud, N. Tectonic evolution of the Dabieshan orogen: In the view from polyphase deformation of the Beihuaiyang metamorphic zone. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2005, 48, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Zhou, J.B.; Wu, Y.B.; Xie, Z. Low-grade metamorphic rocks in the Dabie–Sulu orogenic belt: A passive-margin accretionary wedge deformed during continent subduction. Int. Geol. Rev. 2005, 47, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.T.; Wu, W.P.; Lu, Y.Q.; Wang, D.H. Tectonic setting of the low-grade metamorphic rocks of the Dabie Orogen, central eastern China. J. Struct. Geol. 2012, 37, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, D.B.; Xue, F.; Tucker, R.D.; Peng, Z.X.; Baker, J.; Davis, A. Ages of ultrahigh pressure metamorphism and protolith orthogneisses from the eastern Dabie Shan: U/Pb zircon geochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1997, 151, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, B.R.; Ratschbacher, L.; Webb, L.; Ireland, T.; Walker, D.; Dong, S.W. U/Pb zircon ages constrain the architecture of the ultrahigh-pressure Qinling-Dabie Orogen, China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 161, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Zhao, Z.F.; Wu, Y.B.; Zhang, S.B.; Liu, X.M.; Wu, F.Y. Zircon U–Pb age, Hf and O isotope constraints on protolith origin of ultrahigh-pressure eclogite and gneiss in the Dabie orogen. Chem. Geol. 2006, 231, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prave, A.R.; Meng, F.W.; Lepland, A.; Kirsimäe, K.; Kreitsmann, T.; Jiang, C.Z. A refined late-Cryogenian–Ediacaran earth history of South China: Phosphorous-rich marbles of the Dabie and Sulu orogens. Precambrian Res. 2018, 305, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G.; Jagoutz, E.; Chen, Y.Z.; Li, Q.L. Sm-Nd and Rb-Sr isotopic chronology and cooling history of ultrahigh pressure metamorphic rocks and their country rocks at Shuanghe in the Dabie Mountains, Central China. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2000, 64, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.L.; Gerdes, A.; Liou, J.G.; Xue, H.M.; Liang, F.H. SHRIMP U-Pb zircon dating from Sulu-Dabie dolomitic marble, eastern China: Constraints on prograde, ultrahigh-pressure and retrograde metamorphic ages. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2006, 24, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Ji, W.B.; Faure, M.; Wu, L.; Li, Q.L.; Shi, Y.H.; Schärer, U.; Wang, F.; Wang, Q.C. Early Cretaceous extensional reworking of the Triassic HP-UHP metamorphic orogen in Eastern China. Tectonophysics 2015, 662, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Yang, J.H.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.S. Determination of the formation time of the present tectonic framework in the Dabie Orogen, eastern China: Zircon U-Pb geochronology and Al-in-Hornblende geobarometer. Minerals 2024, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.C.; Cawood, P.A. Precambrian geology of China. Precambrian Res. 2012, 222–223, 13–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Jiang, C.; Yang, J.H.; Bai, Q. Geochronology and geochemistry of Beilou granitic pluton: Identification of early Paleozoic arc magmatic rock in the Dabie Orogen, central China. Geol. J. 2022, 57, 2540–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, Y.S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Gu, C.C.; Li, Y.J. An accreted micro-continent in the north of the Dabie Orogen, East China: Evidence from dating results of detrital zircons. Tectonophysics 2017, 698, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.K.; Shi, Y.H.; Cheng, N.F.; Yang, G.S.; Li, J.J.; Tang, G.X. Tectonic affinity and evolution of the Foziling Group: A window into the Dabie orogenic belt’s shallow subduction process. Lithos 2024, 488–489, 107804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Gao, S.; Hu, Z.C.; Gao, C.G.; Zong, K.Q.; Wang, D.B. Continental and oceanic crust recycling-induced melt-peridotite interactions in the Trans-North China Orogen: U-Pb dating, Hf isotopes and trace elements in zircons from mantle xenoliths. J. Petrol. 2010, 51, 537–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. Correction of common lead in U-Pb analyses that do not report 204Pb. Chem. Geol. 2002, 192, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, K.R. User’s Manual for Isoplot 3.14: A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel; Berkeley Geochronology Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.C.; Liu, Y.S.; Gao, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Tong, X.; Lin, L.; Zong, K.Q.; Li, M.; Chen, H.; et al. Improved in situ Hf isotope ratio analysis of zircon using newly designed X skimmer cone and jet sample cone in combination with the addition of nitrogen by laser ablation multiple collector ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom 2012, 27, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousova, E.A.; Griffin, W.L.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Fisher, N. Igneous zircon: Trace element composition as an indicator of source rock type. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2002, 143, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood, P.C. Boundary lines within petrologic diagrams which use oxides of major and minor elements. Lithos 1989, 22, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniar, P.D.; Piccoli, P.M. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1989, 101, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, S.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Li, Q.L.; Lia, Z.X.; Sun, F.Y. The occurrence of Neoproterozoic low δ18O igneous rocks in the northwestern margin of the South China Block: Implications for the Rodinia configuration. Precambrian Res. 2020, 347, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Yang, B.Z.; Tan, L.; Li, X.Y.; Deng, N. Neoproterozoic (750–711 Ma) Tectonics of the South Qinling Belt, Central China: New Insights from Geochemical, Zircon U-Pb Geochronological, and Sr-Nd Isotopic Data from the Niushan Complex. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. Ed. 2023, 97, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.F.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, T.; Lu, S.S.; Zhao, L. Petrogenesis and tectonic significance of the middle Neoproterozoic highly fractionated A-type granite in the South Qinling block. Geol. Mag. 2021, 158, 1891–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, K.G.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.N.; Deng, X. Ca. 800 Ma I-type granites from the Hong’an Terrane, central China: New constraints on the mid-Neoproterozoic tectonic transition from convergence to extension in the northern margin of the Yangtze Block. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2022, 239, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; She, Z.B.; Ma, C.Q.; Yuan, J.L.; Kong, L.Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, J.; Fan, C.; Guo, P.; Deng, H.; et al. Widespread ca. 800 Ma granitoids in the southern Dabie Orogen: Petrogenesis and implications for Neoproterozoic accretion-type orogeny in the northern Yangtze Block. Precambrian Res. 2024, 414, 107610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.J.; Hu, M.Y.; Kong, L.Y.; Wang, L.; Lyu, Q.Q. Discovery and Geological Significance of Neoproterozoic Bimodal Intrusive Rocks in the Dabie Orogen, China. Minerals 2024, 14, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, J.C.; Wu, C.; Wang, G.S.; Wu, J.W.; Zhou, Z.G.; Li, J.L.; Haproff, P.J. Neoproterozoic–mesozoic tectono-magmatic evolution of the northern Dabie Orogen, eastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2022, 228, 105138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.L.; Yang, Z.Y.; Liu, K.; Zhu, W.; Zhan, H.L.; Yang, P.; Wei, T.Z.; Wang, S.X.; Zhang, Y.Y. Involvement of the Northeastern Margin of South China Block in Rodinia Supercontinent Evolution: A Case Study of Neoproterozoic Granitic Gneiss in Rizhao Area, Shandong Province. Minerals 2024, 14, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Brown, M.; Johnson, T.E.; Kirkland, C.L.; Clark, C.; Blereau, E. Not all Neoproterozoic continental crust exposed in the Sulu belt was deeply subducted. Lithos 2025, 510–511, 108116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 1989, 42, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Zhou, J.C.; Qiu, J.S.; Jiang, S.Y.; Shi, Y.R. Geochronology and geochemistry of Neoproterozoic mafic rocks from western Hunan, South China: Implications for petrogenesis and post-orogenic extension. Geol. Mag. 2008, 145, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, B.W. Aluminium saturation in I- and S-type granites and the characterization of fractionated haplogranites. Lithos 1999, 46, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.F. Are strongly peraluminous magmas derived from pelitic sedimentary sources? J. Geol. 1985, 93, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Liu, X.C.; Ji, W.Q.; Wang, J.M.; Yang, L. Highly fractionated granites: Recognition and research. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 60, 1201–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J.B.; Currie, K.L.; Chappell, B.W. A-type granites: Geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 95, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regelous, A.; Scharfenberg, L.; De Wall, H. Origin of S-, A- and I-Type Granites: Petrogenetic Evidence from Whole Rock Th/U Ratio Variations. Minerals 2021, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.L.; White, A.J.R.; Chappell, B.W.; Allen, C.M. Characterization and origin of aluminous A-type granites from the Lachlan fold belt, southeastern Australia. J. Petrol. 1997, 38, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, J.M.; Watson, E.B. New thermodynamic models and revised calibrations for the Ti-in-zircon and Zr-in-rutile thermometers. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2007, 154, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.M.W.; Yakymchuk, C.; Spencer, C.J.; Keller, C.B.; Tapster, S.R. Revisiting the discrimination and distribution of S-type granites from zircon trace element composition. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2024, 633, 118638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The geochemical evolution of the continental crust. Rev. Geophys. 1995, 33, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Harris, N.B.W.; Tindle, A.G. Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks. J. Petrol. 1984, 25, 956–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.B.; Cherniak, D.J. Oxygen diffusion in zircon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1997, 148, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, S.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Xia, Q.X.; Rubatto, D. Geochemical evidence for hydration and dehydration of crustal rocks during continental rifting. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2019, 124, 12593–12619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Gao, S.; Jiao, W.F.; Liu, Y.S. Zircon U-Pb age and trace element evidence for Paleoproterozoic granulite-facies metamorphism and Archean crustal rocks in the Dabie Orogen. Lithos 2008, 101, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Bai, Q.; Tian, Z.Q.; Du, H. Detrital zircon U–Pb dating in the southern Hefei Basin: Evidence for exhumation of HP–UHP rocks of the Dabie Orogen. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 954–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhu, G.; Wu, Q.; Hu, R.M.; Wu, Y.H.; Xu, Z.Y.; Ye, J. Evidence for discrete Archean microcontinents in the Yangtze Craton. Precambrian Res. 2021, 361, 106259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, X.Y.; Santosh, M.; Aulbach, S.; Zhou, H.Y.; Geng, J.Z.; Sun, W.D. Neoproterozoic intraplate crustal accretion on the northern margin of the Yangtze Block: Evidence from geochemistry, zircon SHRIMP U-Pb dating and Hf isotopes from the Fuchashan Complex. Precambrian Res. 2015, 268, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, J.; Zhao, J.X.; Yang, Y.Z.; Chen, F.K. Multiple-stage Neoproterozoic magmatism recorded in the Zhangbaling uplift of the Northeastern Yangtze Block: Evidence from zircon ages and geochemistry. Minerals 2023, 13, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.X.; Wu, Y.B.; Zhou, G.Y.; He, Y.; Liu, X.C.; Hu, P.; Chang, H.; Liu, C.Y.H. Crustal architecture of the southern Tongbai orogen, central China: Insight from migmatites and post-collisional granites. Lithos 2021, 404, 106439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.Q.; Zhao, Z.F.; Dai, L.Q.; Zheng, Y.F. Slab–mantle interaction in the petrogenesis of andesitic magmas: Geochemical evidence from postcollisional intermediate volcanic rocks in the Dabie Orogen, China. J. Petrol. 2016, 57, 1109–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, S.B.; Zheng, Y.F. High temperature glacial meltwater–rock reaction in the Neoproterozoic: Evidence from zircon in-situ oxygen isotopes in granitic gneiss from the Sulu orogen. Precambrian Res. 2016, 284, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Wu, Y.B.; Liu, X.C.; Gao, S.; Wang, H.; Zheng, J.P.; Yang, S.H. Distinct zircon U–Pb and O–Hf–Nd–Sr isotopic behaviour during fluid flow in UHP metamorphic rocks: Evidence from metamorphic veins and their host eclogite in the Sulu Orogen, China. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2016, 34, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.; Xu, Z.Q.; Santosh, M. Neoproterozoic magmatism in the northern margin of the Yangtze Block, China: Implications for slab rollback in a subduction-related setting. Precambrian Res. 2019, 327, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).