Abstract

Coal gangue, a major industrial solid waste from coal mining and processing, requires efficient alumina and silica separation for high-value utilization. This study focused on mineral reaction mechanisms and characteristics of coal gangue during calcination and alkaline leaching. Results showed calcination at 900–1200 °C altered its phase composition, affecting silica separation efficiency, with the optimal calcination range being 960–1120 °C. Poorly crystallized mullite and Al2O3 in calcined gangue were insoluble under low-alkaline and low-temperature conditions. On the contrary, amorphous silica is soluble and forms a sodium silicate solution in the proper alkaline conditions. This characteristic facilitates the efficient separation of alumina and silica. It was determined that the suitable conditions for silica removal from coal gangue are as follows: 1080 °C calcination for 90 min, leaching at 75 °C with 200 g/L NaOH (solid–liquid ratio of 1:4) for 4 h. Under these selected conditions, the silica leaching efficiency was 77.31%, the alumina leaching efficiency was 12.21%, the Na2O content in the leached residue was 1.94%, and the mass ratio of alumina to silica (A/S) in the leached residue increased from 0.88 to 3.42. A potential desilication mechanism was also analyzed.

1. Introduction

Coal gangue is a substantial industrial solid waste generated in the process of coal mining and processing [1]. The main chemical composition of coal gangue is Al2O3 and SiO2, and the key mineral composition of gangue is kaolin, illite, quartz, etc. [2]. The stockpile of coal gangue has grown to more than 7.7 billion tons [3] and is escalating annually by 300–350 million tons [4,5,6,7]. Most gangue is disposed by stockpile, which occupies a large amount of land and causes serious risks of environmental problems [8,9,10,11,12,13]. After years of efforts, although the comprehensive utilization rate of coal gangue in China has exceeded 70%, it is still mainly used for filling roadbeds and low-lying areas, road construction, simple reclamation, landfill, and other direct use, accounting for 35%–45% of the total amount of the gangue; gangue combustion in power plants and use of other fuels accounts for 10%–15%; gangue bricks and other building materials account for 5%–10%; and the filling of underground mining accounts for 3%–7% [14,15,16,17]. These modes of utilization are all low-value utilization.

The western regions of China (Ordos Basin) are rich in high-alumina coal resources, which is a large high-quality power coal base in China. The prospective reserves are more than 100 billion tons, the proven reserves are 58 billion tons, the mining output is over 200 million tons per year, and the associated high-alumina coal gangue (alumina content exceeds 35%) is about 20 million tons per year [18]. High-alumina coal gangue can be used for high-value utilization of alumina-based products based on its high alumina content and potential mineral resources [19].

The extraction of alumina, silicon, and other valuable elements from coal gangue is a crucial method for exploiting its high value. Various technical routes for alumina extraction from coal gangue have been reported, primarily categorized into an alkaline process and an acid process [20,21,22,23,24,25]. The acid method operates on the principle that alumina dissolves in the liquid phase with sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid, while silicon remains in the solid phase, enabling alumina–silicon separation through solid–liquid separation. The acid process has the advantages of a high alumina extraction rate, short process flow, and fewer by-products. However, these processes have the disadvantages of generating large amounts of wastewater, the need for corrosive-resistant equipment, and high iron content in the intermediate products [26,27,28,29]. The alkali process is currently carried out in industrial applications and can be subdivided into a lime sinter process, soda-lime sinter process, pre-desilication and soda-lime sinter process, et al. [30,31,32,33]. The alkali process is characterized by technical maturity, minimal equipment demands, and direct applicability of products in aluminum electrolysis processes. Yet, challenges like lengthy process flows, substantial material flows, and increased by-product generation exist. In comparison to the acid process, the alkali method emerges as a more promising avenue for coal gangue resource utilization. Therefore, the difficulty of separating alumina and silica components hinders the further efficient utilization and high value of coal gangue.

Calcination of coal gangue to alter the phase composition and subsequent treatment of the calcined coal gangue by alkaline leaching is a potential way to separate alumina and silica in alumina-silica-bearing minerals [34,35,36]. Some studies have indicated that the inclusion of additives can enhance the activation effect during the calcination of coal gangue [37]. Li et al. [6,33] utilized hematite as an additive and implemented a reduction roasting–alkaline leaching process, achieving a silica leaching efficiency of approximately 95%. Song et al. [38]. demonstrated that calcination of coal gangue mixed with calcium hydroxide can significantly improve the activity of coal gangue. Guo et al. [39]. observed that with calcination temperatures ranging from 800 to 900 °C with Na2CO3 to coal gangue weight ratios of 0.8–1, alumina extractions exceeding 90% were obtained. When Lan et al. [40] employed KOH as an additive, with a coal gangue-to-additive ratio of 1:2, a microwave oven power of 595 W, and time of microwave activation of 20 min, a much higher extraction percent of Al (>50) was obtained. Previous research on these additives has primarily concentrated on alumina extraction from coal gangue. Nevertheless, incorporating additives into the calcination process presents challenges, such as the difficulty in controlling the calcined atmosphere, process complexity, and high alumina dissolution losses.

To address the treatment and resource utilization of coal gangue in coal-rich regions, there is an urgent necessity to develop and implement high-value utilization technologies for coal gangue, enabling large-scale reduction of coal gangue. The key to achieving high-value utilization of coal gangue lies in achieving efficient and cost-effective separation of alumina and silica. One of the key advantages of the calcination–alkaline leaching process is its utilization of self-carried carbon during calcination, reducing the reliance on external fuels. Enhanced desilication efficiency translates to higher resource utilization rates for coal gangue. Currently, there is a lack of research on the efficient separation of alumina and silica utilizing the intrinsic phase transformation properties of coal gangue itself, without the need for additives and employing a straightforward calcination treatment process. Current research outcomes in this field are predominantly derived from laboratory-based studies, and there remains a scarcity of practical cases for industrial application.

In this paper, the removal of silica from coal gangue through a calcination–alkaline leaching process was investigated. The mineral phase transformation of coal gangue was investigated during calcination ranging from 900 °C to 1200 °C. The characteristics of mineral phase transformation of the calcined clinker under alkaline leaching conditions were analyzed. Furthermore, the effects of desilication efficiency at different alkaline leaching temperatures was assessed. A potential desilication mechanism was speculated. This process results in the production of silica solution and high-alumina containing residue slag, both of which have practical applications. This study was experimentally validated on a 10,000-ton/year pilot platform, and the desilication performance achieved was consistent with the expected outcomes. The findings of this study carry considerable significance for the high-value utilization of coal gangue and the industrial translation of this technology—with particular relevance to low-grade bauxite ores rich in kaolinite (a typical high-silica aluminum resource). Furthermore, the microstructure of crystal transformation mechanism during calcination, the kinetics of the desilication reaction, and the high-value utilization of the desilication solution will be the core focuses of further research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The analytical grade chemical reagent sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was procured from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China and utilized for the alkaline leaching experiments. The coal gangue raw materials used in this experiment were gathered from Jinzhengtai coal mine in the Jungar coalfield, Inner Mongolia, China. The coal gangue (approximately 50 kg) that met the requirements was separated using X-ray intelligent separation technology (provided by Ganzhou Good Friend Co., Ltd., Ganzhou, China). After being dried in an oven at 105 °C for 12 h, the coal gangue was crushed and ground until its particle size was less than 150 μm. The chemical composition of the coal gangue is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition in coal gangue and clinker (wt.%).

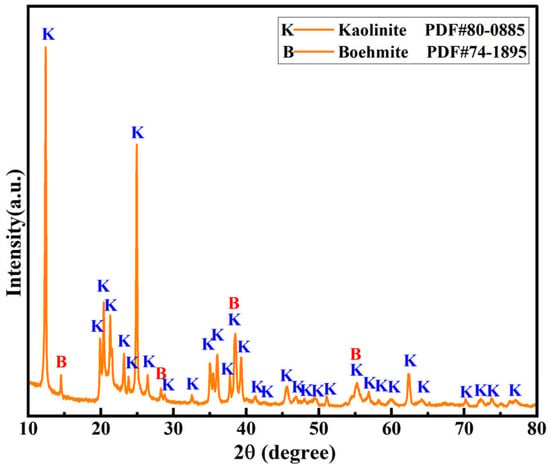

The XRD analysis of the mineral compositions indicated that kaolinite was the main phase in the coal gangue, along with a small quantity of boehmite (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of high-alumina coal gangue.

2.2. Calcination Test

A 100.0 g sample of coal gangue was accurately weighed and gently placed in an 80 mm × 80 mm × 40 mm corundum crucible. Then, the loaded crucible was moved to a muffle furnace (KSL-1700X, Hefei Kejing Material Technology Co., Ltd., Hefei, China). The furnace temperature was gradually raised from ambient to specified levels (900–1200 °C in 20-degree intervals) at a rate of 5 °C/min. Upon the muffle furnace attaining the preset temperature, the sample was held at this temperature for a period of 90 min. After the calcination, the calcined coal gangue was left to cool naturally to room temperature. Then, it was taken out and used for the subsequent alkaline leaching experiments.

2.3. Alkaline Leaching Test

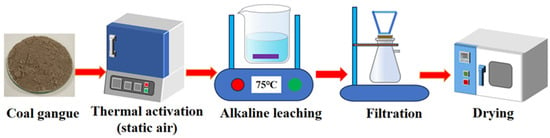

In the present study, alkaline leaching experiments were executed utilizing a temperature-regulated water bath pot. The optimization of these alkaline leaching processes was achieved by precisely modulating critical process parameters. In this research, the effects of alkaline leaching temperature on the alkaline leaching were systematically examined, the alkaline leaching temperature varied across the range of 45, 55, 65, 75, 85, and 95 °C, the alkaline leaching time was set to 4 h, the alkali concentration was specifically fixed at 200 g/L NaOH, and the solid-to-liquid ratio was determined as 15 g/60 mL. These parameters were selected based on preliminary exploratory experiments and industrial operational feasibility, ensuring sufficient desilication efficiency and compatibility with the production process. Subsequent to the leaching process, the solid residue was meticulously washed with deionized water maintained at a temperature of 90 °C. Subsequently, it was dried at a temperature of 105 °C for a duration of 3 h to facilitate further characterization. The entire experiment process can be represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic of calcination–alkaline leaching process.

The leaching efficiency of silica in calcined coal gangue is calculated using the following formula:

where M1 is the mass of the calcined coal gangue(g), is the silica content in the calcined coal gangue (%), M2 is the mass of the leached residue (g), and is the silica content in the leached residue (%).

The leaching efficiency of alumina in calcined coal gangue is calculated using the following formula:

where M1 is the mass of the calcined coal gangue(g), is the alumina content in the calcined coal gangue (%), M2 is the mass of the leached residue (g), and is the alumina content in the leached residue (%).

2.4. Thermodynamic Analysis

Thermodynamic analysis of the reaction equations was conducted using HSC 9.0 software, leveraging its built-in H, S, and Cp Thermochemical Database and Minerals Database.

To validate the reliability of these results, a manual cross-comparison was performed against thermodynamic data reported in the literature [41]. For the thermodynamic calculations, the properties of SiO2 and Al2O3 were represented using the database data for quartz and γ-Al2O3, respectively. For kaolinite, its Gibbs free energy of formation (∆Gf) at 700–1600 K was derived via linear fitting as ∆Gf = 1.07T − 4119.53 with a correlation coefficient R2 = 1.00. This expression was obtained by extrapolating the linear fitting results of kaolinite’s thermodynamic data (at 298.15–700 K) to the 700–1600 K temperature range [34].

2.5. Characterization

The phase and crystalline structures of materials were determined through X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8 Advanced, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) analysis using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm) and the 2theta test range of 5–80°. The morphology of samples was examined utilizing a Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford X-MAX20, High Wycombe, UK) detectors for compositional analysis. Chemical compositions of the calcined coal gangue and the leached residue were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF, ARL PERFORM’X-4200, Thermo Fisher, Tewksbury, MA, USA). The chemical bonds in the calcined coal gangue and the leached residue were identified using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, Nicolet iS5, Thermo Fisher, Madison, WI, USA) with spectral range of 400–4000 cm−1. Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis was carried out using NETZSCH STA 449 C (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany) from room temperature to 1300 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under an air atmosphere.

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Behavior and Thermodynamic Analysis of High-Alumina Coal Gangue During Calcination

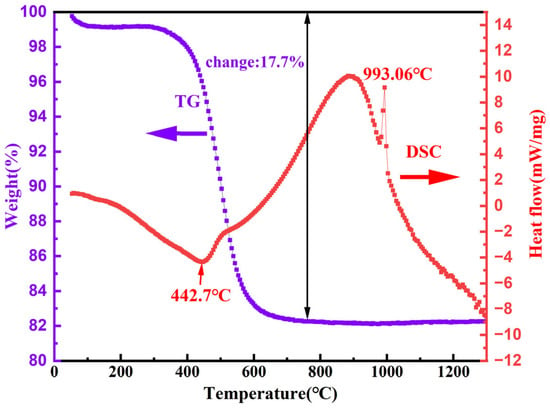

To understand the thermal behavior of high-alumina coal gangue (a key step for optimizing its calcination and desilication processes), TG-DSC analysis was performed, with the curves presented in Figure 3. The TG curve reveals a significant mass loss (17.7%) in the temperature range of 400–700 °C, which corresponds to the dehydroxylation of kaolinite (the dominant aluminosilicate mineral in coal gangue). Furthermore, the initiation temperature of dehydroxylation for kaolin was ascertained to be 442.7 °C. An exothermic peak was detected at 993.06 °C, which serves as an indication of the transition temperature from kaolin to the spinel or mullite phase [33].

Figure 3.

TG-DSC curves of the high-alumina coal gangue.

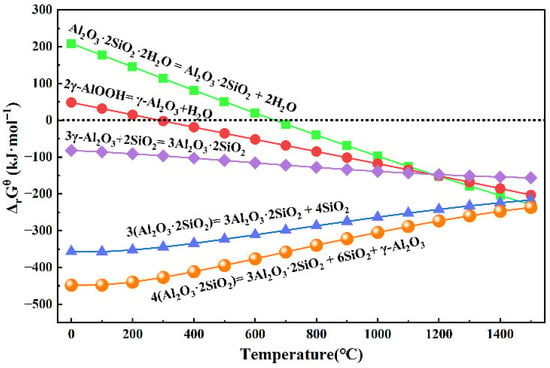

To explain the thermal behavior observed in TG-DSC curves, thermodynamic calculations were performed. High-alumina coal gangue is predominantly composed of two primary minerals: kaolinite and boehmite. With increasing calcination temperatures, the primary potential reactions are summarized as follows:

Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O (kaolinite) = Al2O3·2SiO2 (metakaolin) + 2H2O

3(Al2O3·2SiO2) = 3Al2O3·2SiO2 + 4SiO2

Thermodynamic analysis of the above reaction equations was performed using HSC 9.0 software, with results presented in Figure 4. The manually derived results show good consistency with the thermodynamic calculations from HSC 9.0. Under standard atmospheric pressure, the standard molar Gibbs free energy change (ΔrGθ) of reaction Formula (3) remains positive at temperatures ranging from 0 to 700 °C, while that of reaction Formula (4) is positive between 0 and 400 °C. This indicates these reactions are non-spontaneous under the specified conditions—meaning they do not proceed spontaneously in the forward direction and require external energy input to proceed within these temperature ranges. Above 700 °C, kaolinite decomposes into metakaolin and H2O, while boehmite concurrently breaks down into Al2O3 and H2O. At temperatures exceeding 980 °C, metakaolin further decomposes into amorphous silica and mullite [6]. As illustrated in Figure 4, the conversion of metakaolin to mullite and amorphous silica proceeds readily during calcination, as reaction Formulas (4) and (5) exhibit negative ΔrGθ values. With continued increases in calcination temperature, Al2O3 and amorphous silica can react to form mullite due to the negative ΔrGθ of reaction Formula (7).

Figure 4.

Relationship between ΔrGθ and temperature for Formulas (3)–(7).

3.2. Separation of Amorphous Silica

3.2.1. The Impact of Calcination Temperature on Desilication Efficiency

To understand more comprehensively the leaching behavior of amorphous silica from gangue clinker at various calcination temperatures in an alkaline environment, the gangue clinker was subjected to alkaline leaching. This was carried out in a 200 g/L NaOH solution with a solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL at different alkali-desilication temperatures for 4 h.

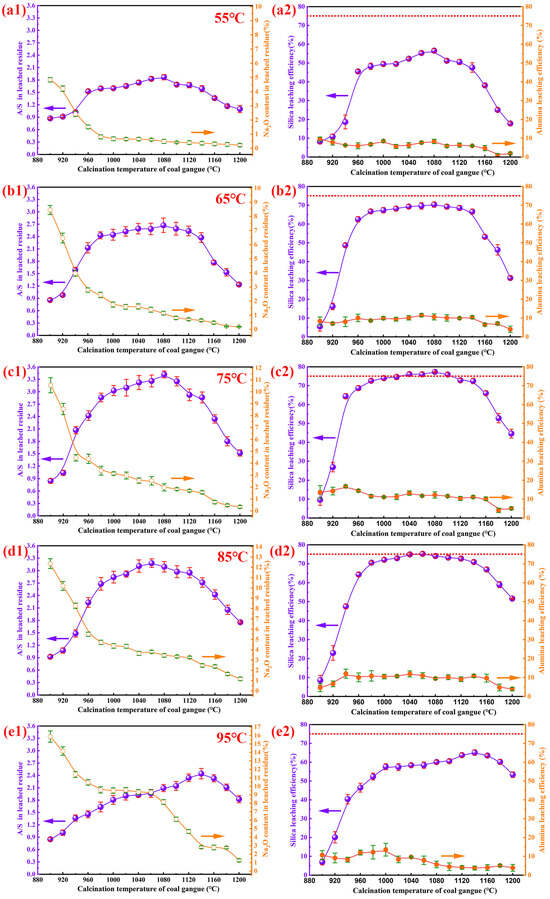

As shown in Figure 5(a1,a2), alkali desilication of calcined gangue clinker at 55 °C revealed that the A/S ratio in leached residues increased from 0.87 to 1.87 with calcination temperatures rising from 900 °C to 1080 °C, then decreased to 1.17 at 1200 °C. Concurrently, the Na2O content dropped from a peak of 4.83% to 0.22%. Silica leaching efficiency rose gradually from 8.22% to 56.57% within 900–1080 °C, but declined to 25.05% at 1200 °C. Alumina leaching efficiency remained below 10.0%, decreasing with higher temperatures.

Figure 5.

The leaching performance of calcined gangue clinker under varying alkali desilication temperatures is illustrated as follows: (a1,a2) 55 °C desilication, (b1,b2) 65 °C desilication, (c1,c2) 75 °C desilication, (d1,d2) 85 °C desilication, and (e1,e2) 95 °C desilication. All experiments were conducted under standardized conditions: 4 h leaching duration, 200 g/L NaOH concentration, and a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:4 (15 g/60 mL) at different calcination temperatures.

Figure 5(b1,b2) depicts results at 65 °C: the A/S ratio surged from 0.86 to 2.67 between 900 and 1080 °C, then fell to 1.24 at 1200 °C. Na2O content dropped from 8.45% to 0.18% across the same temperature range. Silica leaching efficiency peaked at 70.36% at 1080 °C (up from 5.50% at 900 °C), then declined to 31.29% at 1200 °C. Alumina leaching efficiency fluctuated between 5.0% and 10.0%.

At 75 °C (Figure 5(c1,c2)), the A/S ratio sharply increased to 3.42 at 1080 °C (from 0.85 at 900 °C), then decreased to 1.52 at 1200 °C. Na2O content dropped from 10.55% to 0.34%. Silica leaching first rose steeply to 68.74% at 960 °C, then plateaued to a peak of 77.30% at 1080 °C, before falling to 44.61% at 1200 °C. Alumina leaching efficiency ranged from 5.0% to 15.0%.

As shown in Figure 5(d1,d2), alkali desilication at 85 °C showed that the A/S ratio in leached residues surged from 0.92 to 3.18 with calcination temperatures rising from 900 °C to 1060 °C, then gradually declined to 1.76 at 1200 °C. Na2O content dropped from a peak of 12.36% at 900 °C to 1.17% at 1200 °C. Silica leaching efficiency spiked from 8.54% to 64.30% between 900 and 960 °C, rose to a peak of 75.22% at 1060 °C, then fell to 51.62% at 1200 °C. Alumina leaching efficiency fluctuated between 5.0% and 12.0%.

For the 95 °C condition (Figure 5(e1,e2)), the A/S ratio slowly increased from 0.85 to 2.44 as calcination temperature rose from 900 °C to 1140 °C, then declined to 1.82 at 1200 °C. Na2O content decreased from 15.87% at 900 °C to 1.25% at 1200 °C. Silica leaching efficiency surged from 6.97% to 46.49% between 900 and 960 °C, climbed to a peak of 65.12% at 1140 °C, and dropped to 53.37% at 1200 °C. Alumina leaching efficiency remained in the 5.0%–13.0% range across all temperatures.

Table 2 displays the chemical composition of leached residues post-desilication, illustrating how varying calcination temperatures affect the residue’s elemental distribution.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of leached residues after desilication under different calcination temperatures (wt.%).

As indicated in Figure 5 and Table 2, based on the analysis of the A/S ratio, Na2O content, silica leaching efficiency, and alumina leaching efficiency, the clinker exhibits an underburned state at calcination temperatures of 900–960 °C, reaches the optimal normal-burned state at 960–1120 °C, and enters an overcooked state when the temperature increases to 1120–1200 °C. Analysis results indicate that within the desilication temperature range of 55–75 °C, the silica leaching efficiency increases progressively with increasing temperature. However, when the temperature exceeds 85 °C, this ratio decreases progressively as the temperature continues to rise.

3.2.2. XRD Analysis

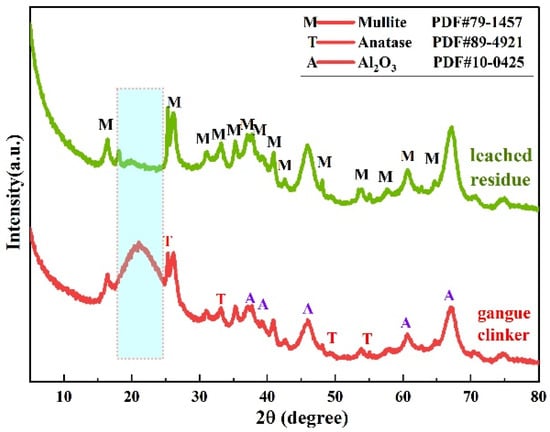

Comparative XRD analysis of the before and after resultant alkaline leached residue of calcined coal gangue is show in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

XRD patterns of alkaline leached residues and the calcined coal gangue clinker obtained at 1080 °C for 90 min, with leaching conditions as follows: 75 °C, 4.0 h, NaOH concentration of 200 g/L, solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL.

The XRD diffraction pattern reveals four phases: mullite, Al2O3, anatase, and amorphous silica. Al2O3 and amorphous silica exhibit stronger diffraction. After alkaline leaching, there are three phases on the leached residue: Al2O3, mullite, anatase; the complete disappearance of the diffraction peak of amorphous silica at 20–22° (2θ) indicates that amorphous silica may have been dissolved in the alkaline solution. Weak diffraction peaks at 2θ = 45.86° and 2θ = 67.03° corresponding to the [400] and [440] lattice plane of Al2O3, respectively, are observed in the before and after alkaline leached residue. The amorphous silica is soluble in the alkaline solution, combined with the presence of Al2O3 in the alkaline leached residue, and represents the primary factor contributing to the increase in the A/S ratio within the residue.

3.2.3. FT-IR Analysis

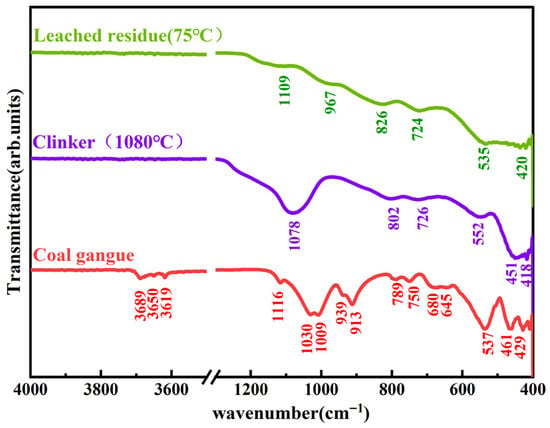

Figure 7 displays the FTIR spectra of coal gangue, clinker, and leached residue, while Table 3 summarizes the characteristic absorption bands corresponding to these three samples.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of coal gangue, 1080 °C calcined clinker (90 min), and alkaline leached residue (leaching conditions: 75 °C, 4.0 h, 200 g/L NaOH, 15 g/60 mL solid/liquid ratio).

Table 3.

FTIR characteristic band assignments for coal gangue, clinker, and leached residue.

For coal gangue, peaks at 3689/3650/3619 cm−1 (kaolinite O-H stretches [42,43]), 1116/1030/1009 cm−1 (Si-O/Si-O-Al stretches [44]), 939/913 cm−1 (Al-O-H swing [45]), and 738/750/680/645 cm−1 (Si-O-Si/Si-O-Al bending/deformation [10,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]) reflect its kaolinite-dominated structure.

For the calcined clinker, the disappearance of O-H-related peaks (3689/3650/3619 cm−1) indicates hydroxyl removal via calcination; the broad peak at 1078 cm−1 (assigned to Si-O (Si-O-Si/Si-O-Al) stretch vibration [44]), combined with the absence of sharp crystalline SiO2diffraction peaks in XRD, suggests the presence of amorphous silica; 802/726 cm−1 (Si-O-Si/Si-O-Al bending [46,47]) and a552/451/418 cm−1 (Si-O/Al-O deformation [48,49]) correspond to the calcined silicoaluminate framework.

For leached residue, a further shifted broad Si-O peak (1109 cm−1 [44]) and a distinct Si-O-Al peak (967 cm−1 [48]) (plus 826/724 cm−1 [46,47] and 535/420 cm−1 [49,50]) reveal structural modifications from desilication, consistent with the change in Si-containing phases.

3.2.4. SEM-EDS Analysis

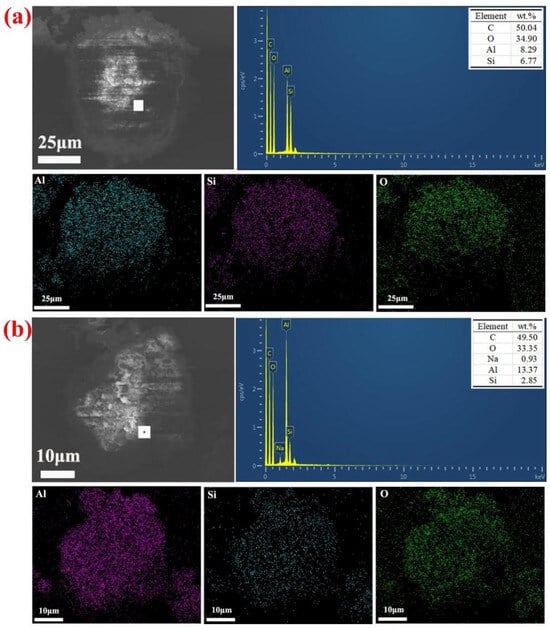

To further elucidate the desilication reaction characteristics of coal gangue clinker calcined and the corresponding alkaline leached residue, they were subjected to detailed SEM-EDS characterization, as depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

SEM-EDS images of (a) calcined gangue clinker and (b) alkaline leached residue (under conditions of 75 °C, 4.0 h, 200 g/L NaOH, solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL).

The energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping of clinker and alkaline leached residue is presented in Figure 8a and Figure 8b, respectively. The elemental C shown in Figure 8 is mainly due to the situation where the sample was put on a conductive adhesive that contains C. Within the labeled particle range, energy spectrum analyses revealed that the coal gangue contained 8.29 wt.% Al and 6.77 wt.%Si, as shown in Figure 8a. Following alkaline leaching, the residue contained 13.37 wt.% Al and 2.85 wt.%Si, as illustrated in Figure 8b. This outcome implies that a significant quantity of SiO2 dissolves in alkaline solutions, resulting in a mass reduction and significant shifts in the relative proportions of Al and Si in the calcined gangue clinker as well as the alkaline leached residue. The major elements Al, Si, and O were uniformly dispersed within the particles not alkaline leached, with their respective contents closely aligned. In contrast, the distribution of the major elements Al and Si in the alkaline leached residue indicated a higher concentration of Al and a lower concentration of Si, while the concentration of element O remained almost constant. Upon comparing the elemental concentrations of calcined gangue clinker, a decrease in the concentration of elemental Si and a lesser decrease in the concentration of elemental Al were shown in the solid phase of alkaline leached residue. The elemental distribution patterns revealed by EDS mapping are consistent with the compositional profiles derived from energy spectrum analysis.

3.3. Mineral Phase Transformation of Coal Gangue During Calcination and Alkaline Leaching

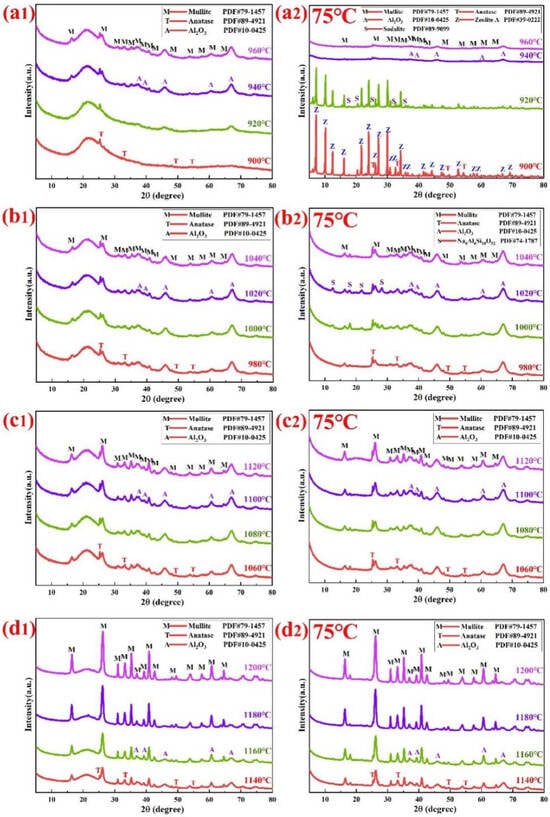

In order to obtain more profound understanding of the phase transformation behavior of coal gangue under different calcination temperatures and the phase transformations happening during the alkaline leaching procedure, the XRD patterns of the coal gangue calcined for 90 min at various temperatures and the XRD analysis results of the leached residues are presented in Figure 9, with the leaching conditions being 75 °C, 4 h, a NaOH concentration of 200 g/L, and a solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL.

Figure 9.

Shows the XRD patterns of coal gangue calcined at different temperature intervals: (a1) 900–960 °C, (b1) 980–1040 °C, (c1) 1060–1120 °C, (d1) 1140–1200 °C for 90 min and their corresponding leached residues’ XRD patterns (a2–d2).

As shown in Figure 9(a1), when the calcination temperature increases from 900 °C to 920 °C, the disappearance of boehmite’s characteristic diffraction peaks indicates boehmite’s complete transformation into Al2O3 via Formula (3), while the vanishing of kaolinite’s peaks suggests its conversion to amorphous meta-kaolinite through Formula (4). During the decomposition of kaolinite and boehmite into an amorphous phase within the temperature range of 900–920 °C, a weak diffraction peak remains at 2θ = 25.303°; this peak corresponds to the [101] lattice plane of anatase. The existence of the anatase phase might be attributed to the approximately 1% TiO2 contained in the coal gangue. Moreover, a broad peak, which represents the typical amorphous silica phase, is observed at 2θ = 20–24°. When the calcination temperature ascends from 940 °C to 960 °C, four phases can be detected in the XRD diffraction pattern: mullite, amorphous silica, Al2O3, and anatase. Weak diffraction peaks appear at 2θ = 16.43° and 2θ = 26.27°, corresponding to the [110] and [210] lattice planes of mullite, respectively.

In the leached residues of clinkers calcined at temperatures between 900 °C and 920 °C, zeolite A along with a small quantity of sodalite were detected in Figure 9(a2). The diffraction intensity of sodalite increased steadily, whereas the diffraction intensity of zeolite A declined gradually. The existence of zeolite A and sodalite within the leached residues shows that meta-kaolinite can engage in a reaction with the alkaline solution as per Formula (8) [32], causing the production of sodium aluminate solution and sodium silicate solution. In the following steps, Formulas (11) and (12) between sodium aluminate and sodium silicate solutions with distinct molecular ratios result in the formation of zeolite A and sodalite respectively [31]. These zeolite-like substances significantly increase the alkali content within the leached residue.

As depicted in Figure 9(b1,c1), when the calcination temperature ascends from 980 °C to 1120 °C, four phases can be detected in the XRD diffraction pattern: mullite, amorphous silica, Al2O3, and anatase. Weak diffraction peaks appear at 2θ = 16.43° and 2θ = 26.27°, corresponding to the [110] and [210] lattice planes of mullite, respectively. At the calcination temperatures of 940 °C to 1060 °C, the characteristic diffraction peaks of mullite are relatively weak. In comparison, the mullite peaks at 1120 °C are stronger than those at 940 °C. Based on previous research [31], amorphous meta-kaolinite might decompose into mullite and amorphous silica via Formula (5). Diffraction peaks are present at 2θ = 45.86° and 2θ = 67.03°, which, respectively, correspond to the [400] and [440] lattice planes of Al2O3 (PDF#10-0425). The characteristic diffraction peaks of Al2O3 that are detected are relatively conspicuous at calcination temperatures of 940 °C and 1120 °C. The emergence of the Al2O3 diffraction peaks can be ascribed to the transformation of boehmite at elevated temperatures via Formula (3) and the decomposition of kaolinite through Formula (6). As a result of the decomposition of metakaolin, there is a relative increase in the diffraction intensity of amorphous silica at the main peak position corresponding to 2θ in the 20–24° interval. The abundant amorphous silica in the products of coal gangue calcination at 940 °C and 1120 °C provides the foundation for efficient alumina–silica separation.

As depicted in Figure 9(b2,c2), the diffraction intensity of amorphous silica at the main peak position where 2θ is between 20 and 22° disappears because amorphous silica is soluble in the alkaline solution. Mullite, anatase, Al2O3, and a small quantity of Na6Al6Si10O32 are detected in the leached residues of clinkers that have been calcined at temperatures ranging from 940 °C to 1120 °C. As the calcination temperature of coal gangue increases to 980 °C and 1120 °C, the reaction between amorphous silica and sodium hydroxide generates sodium silicate through Formula (9), and active alumina and sodium hydroxide generate sodium aluminate through Formula (10) [35]. The reactions described by these equations explain the increase in the A/S ratio of the leached residue and the observed alumina leaching behavior, as shown in Figure 5. The existence of Na6Al6Si10O32 within the leached residues shows that amorphous silica and active Al2O3 can engage in a reaction with the alkaline solution through Formulas (9) and (10), causing the production of sodium aluminate solution and sodium silicate solution. In the following steps, Formula (13) between sodium aluminate and sodium silicate solutions with distinct molecular ratios results in the formation of Na6Al6Si10O32. Mullite and Al2O3 are present in the leached residue, which implies that, within the current reaction circumstances, the reactivity of these components with the alkaline solution is somewhat limited.

6NaOH + Al2O3·2SiO2 = Na2O·Al2O3 + 2Na2SiO3 + 3H2O

2NaOH + SiO2 (amorphous) = Na2SiO3 + H2O

2NaOH + Al2O3 (active) = Na2O·Al2O3 + H2O

Na2O·Al2O3 + 2Na2SiO3+ 6.5H2O = Na2O·Al2O3·2SiO2·4.5H2O + 4NaOH

Na2O·Al2O3 + 6Na2SiO3+ 6H2O = Na2O·Al2O3·6SiO2 +12NaOH

3Na2O·Al2O3 + 10Na2SiO3 + 10H2O = Na6Al6Si10O32 + 20NaOH

3Al2O3·2SiO2 + 10NaOH = 6NaAlO2 + 2Na2SiO3 + 5H2O

3Na2O·Al2O3 + 10Na2SiO3+ 22H2O = Na6Al6Si10O32·12H2O +20NaOH

When the temperature of calcination increases from 1140 °C to 1200 °C, as shown in Figure 9(d1), the characteristic diffraction peaks of mullite are highly conspicuous. This shows that with an increase in temperature, the crystallization form of mullite is more distinct. The occurrence of mullite diffraction peaks is due not only to the breakdown of metakaolin through Formulas (5) or (6) but also to the reaction of Al2O3 and amorphous silica in accordance with Formula (7). When the calcination temperature of coal gangue is increased to 1200 °C, the characteristic diffraction peaks of Al2O3 vanish. The reason could be that Al2O3 reacts with amorphous silica to form mullite via Formula (7). As the calcination temperature rises, the diffraction intensity of amorphous silica in coal gangue samples declines significantly.

In the leached residues of clinkers calcined at temperatures from 1140 °C to 1200 °C, in addition to the pre-existing mullite, a small quantity of Al2O3 was detected in Figure 9(d2). When the diffraction intensity of amorphous silica at the main peak position where 2θ is between 20 and 22°disappeared, no novel substances were detected. These findings imply that mullite and Al2O3 exhibit low reactivity towards the alkaline solution. The XRD analysis results are consistent with the leaching experiments depicted in Figure 5(c1,c2).

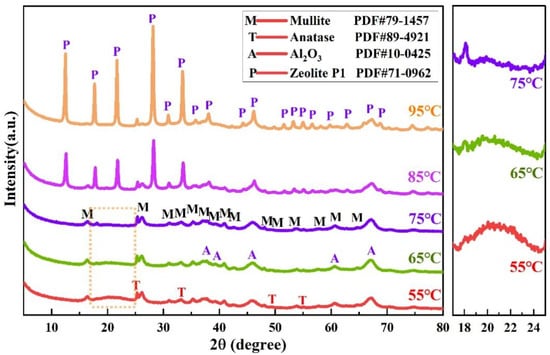

To gain deeper insights into the phase composition of alkaline leached residues under different desilication temperatures (55 °C, 65 °C, 75 °C, 85 °C, 95 °C), their XRD patterns are shown in Figure 10. When the desilication temperature increases from 55 °C to 75 °C, the same three phases—mullite, Al2O3, and anatase—are consistently detected in the XRD patterns of the leached residue. At 55 °C, the XRD pattern exhibits a broad bun peak (2θ = 20~25°) characteristic of amorphous SiO2, suggesting incomplete dissolution of amorphous SiO2 in the NaOH solution due to an insufficient desilication temperature. As the temperature increases to 65 °C, the integral intensity of the amorphous SiO2 bun peak decreases, reflecting a reduced proportion of undissolved amorphous SiO2 in the residue. This indicates that an elevated temperature enhances the solubility of amorphous SiO2 in the NaOH solution, promoting its dissolution. At 75 °C, the characteristic bun peak of amorphous SiO2 nearly vanishes, confirming complete dissolution of amorphous SiO2 in the NaOH solution under sufficient desilication temperatures. At 85 °C and 95 °C, the XRD patterns of the leached residues reveal the emergence of zeolite P1 (Na6Al6Si10O32·12H2O) and anatase, with the diffraction intensity of zeolite P1 being notably higher at 95 °C than at 85 °C. The presence of zeolite P1 and the disappearance of primary crystalline phases (mullite and Al2O3) indicate that amorphous silica and active Al2O3 react with the alkaline solution via Formulas (9) and (10), dissolving into sodium aluminate (NaAlO2) and sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) solutions; and primary mullite decomposes via reaction (14), contributing additional aluminate and silicate ions to the solution. Subsequently, the molecular ratio-dependent Formula (15) between sodium aluminate and sodium silicate solutions triggers the crystallization of zeolite P1, as depicted by Formula (15).

Figure 10.

XRD patterns of alkaline leached residues under varying desilication temperatures (55 °C, 65 °C, 75 °C, 85 °C, 95 °C). Coal gangue was calcined at 1080 °C for 90 min, and the leaching conditions were as follows: 4 h, 200 g/L NaOH, and a solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL.

To better characterize the chemical composition of alkaline leached residues under different desilication temperatures, their constituent profiles are presented in Table 4. As the desilication temperature increases from 55 °C to 95 °C, the Na2O content in the residues rises significantly; this trend can be ascribed to the formation of diverse zeolite phases. Importantly, these chemical analysis results exhibit a strong correlation with the XRD results shown in Figure 10.

Table 4.

Chemical composition of leached residues after desilication under different desilication temperatures (wt.%).

In an effort to elucidate why desilication efficiency declines as desilication temperature increases, XRD characterization was performed on the alkaline leached residue (obtained at 95 °C) across different calcination temperature regimes, as shown in Figure 11. Below 960 °C, zeolite A and Faujasite-Na react rapidly under the studied experimental conditions. For calcination temperatures ranging from 960 to 1120 °C, primary mullite and amorphous SiO2 undergo reactions with the alkaline solution according to Formulas (9) and (14), producing sodium silicate and sodium aluminate as intermediate products. These intermediates subsequently undergo a secondary reaction to generate zeolite P1. When the calcination temperature is elevated to 1140–1200 °C, the final solid product is a mixture of zeolite P1 and residual primary mullite. By comparing with Figure 9, it can be concluded that the primary mullite phase disappears within the calcination temperature range of 940–1100 °C. This indicates that at a desilication temperature of 75 °C, the alkaline solution only leaches amorphous SiO2 without reacting with the primary mullite phase. However, when the desilication temperature is elevated to 95 °C, the reaction pathway changes: the alkaline solution first reacts with amorphous SiO2, and after the majority of amorphous silica is consumed, it further reacts with the primary mullite phase. The decomposition of mullite leads to a significant increase in the liquid-phase Al2O3 concentration, which drives the in situ formation of a zeolite phase. This zeolite phase precipitates back into the solid residue, thereby inhibiting the leaching of silica and reducing its leaching rate.

Figure 11.

XRD patterns of leaching residues obtained under different calcination temperature ranges of (a) 900–960 °C, (b) 980–1040 °C, (c) 1060–1120 °C, (d) 1140–1200 °C, with a fixed desilication temperature of 95 °C, 4 h, 200 g/L NaOH, and a solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL.

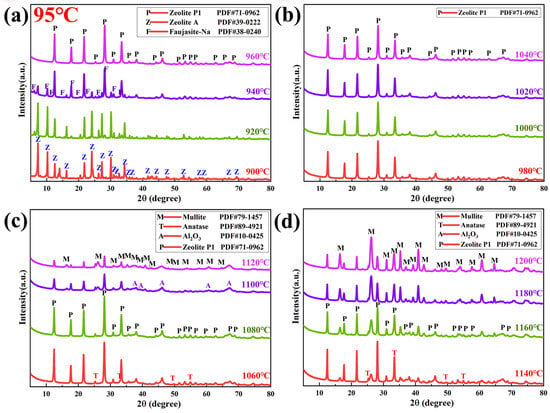

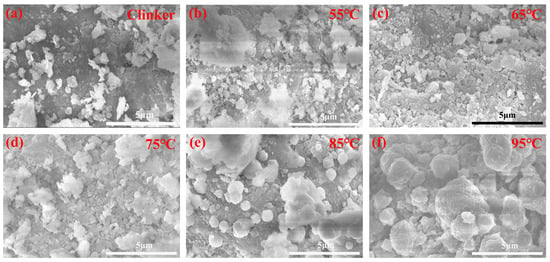

3.4. Microscopic Morphological Changes of the Leached Residues After Alkaline Leaching

To obtain a more profound understanding of the microscopic morphological alterations of alkaline solution leached residues at various calcination temperatures, SEM analyses were carried out, as depicted in Figure 12. The leaching conditions are 75 °C, 4 h, a NaOH concentration of 200 g/L, and a solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL.

Figure 12.

SEM images of the leached residues with different calcination temperature: (a) 900 °C, (b) 920 °C, (c) 940 °C, (d) 960 °C, (e) 980 °C, (f) 1000 °C, (g) 1020 °C, (h) 1040 °C, (i) 1060 °C, (j) 1080 °C, (k) 1100 °C, (l) 1120 °C, (m) 1140 °C, (n) 1160 °C, (o) 1180 °C, (p) 1200 °C.

In Figure 12a, a multitude of zeolite A cubic particles, measuring only 1.0–3.0 μm, alongside small spherical sodalite particles measuring approximately 0.5–1.0 μm at 900 °C is shown. As the calcination temperature increases to 920 °C in Figure 12b, the amount of zeolite A cubic particles decreases, measuring only 0.5–2.0 μm, whereas the amount of sodalite particles increases, measuring approximately 1.0–2.0 μm. These SEM images align closely with the XRD analysis findings in Figure 6. As the calcination temperature increases to 940 °C in Figure 12c, a very small amount of sodalite particles can be observed and most of the particles are clustered flakes. As the calcination temperature increases from 960 °C to 1120 °C in Figure 12d–l, the leached residue exhibits a granular and aggregated state, with minor changes compared to the calcination clinker, and some large particles are present as calcination temperature increases. After leaching with an alkaline solution, the leached residue shows minimal structural changes.

As the calcination temperature progresses (Figure 12m–p), the leached residue exhibits a granular and aggregated state. Aggregation between particles is denser in this temperature range than that in the lower temperature range (960–1120 °C), with a gradual increase in large particles, which is due to the fact that at this calcination temperature interval, the amorphous silica reacts with active Al2O3 through Formula (11) and the amorphous silica content is low and less dissolved in the alkaline solution. These SEM observations are consistent with the leaching experiments detailed in Figure 5(c1,c2).

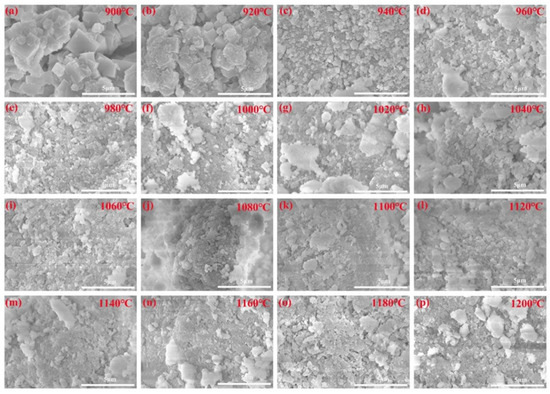

To obtain a more profound understanding of the microscopic morphological alterations of alkaline solution leached residues at various alkali desilication temperatures, SEM analyses were carried out, as depicted in Figure 13, the calcination temperature is 1080 °C, and the leaching conditions are 4 h, a NaOH concentration of 200 g/L, and a solid/liquid ratio of 15 g/60 mL.

Figure 13.

SEM images of leached residues: (a) 45 °C, (b) 55 °C, (c) 65 °C, (d) 75 °C, (e) 85 °C, (f) 95 °C, respectively.

In Figure 13a, the surface of the calcination clinker particles exhibits lamellar aggregates with a relatively compact architecture. Additionally, a minor fraction of fine particles (approximately 0.5–2.0 μm in size) exists as discrete entities rather than being incorporated into the aggregate structure. As the alkali desilication temperature increases from 55 °C to 75 °C in Figure 13b–d, the leached residue exhibits a granular and aggregated state, with minor changes compared to the calcination clinker, and partial aggregation of particles to a relatively large extent, about 1–3 μm. As the desilication temperature increases from 55 °C to 75 °C, the increasing leaching rate of amorphous silica leads to a gradual increase in pore structure. In Figure 13e, when the alkali desilication temperature rises to 85 °C, a large number of spherical-like zeolite P1 particles with a size of about 1.0–2.0 μm are present. In Figure 13f, when the alkali desilication temperature attains 95 °C, a substantial quantity of spherical-like zeolite P1 particles with a size ranging from approximately 2.0 to 4.0 μm becomes observable. At this temperature, the elevated crystallinity of the zeolite P1 particles results in a more perfect zeolite morphology. These SEM images are in close agreement with the XRD analysis results shown in Figure 10.

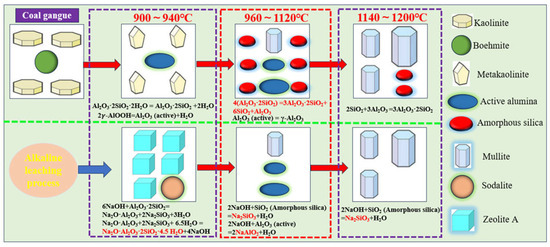

4. Discussion

In order to elucidate the desilication reaction mechanism of calcined gangue clinker, analysis of the raw materials in the coal gangue reveals the presence of two minerals, namely kaolinite and boehmite. It has been established that boehmite undergoes decomposition at a calcination temperature of 960–1120 °C, resulting in the formation of Al2O3 [31]. The kaolinite decomposes into meta-kaolinite at about 400–500 °C, and meta-kaolinite might decompose into mullite and amorphous silica via Formula (5) or decompose into mullite, Al2O3, and amorphous silica via Formula (6) at about 960–1120 °C. Theoretical assessments of the reaction equations are carried out to calculate the theoretical desilication efficiency and theoretical A/S ratios that stem from the two reaction equations. If the meta-kaolinite is decomposed according to Formula (5), the theoretical desilication efficiency achievable is 66.67%, corresponding to the A/S ratio of leached residue of 2.55. Similarly, Formula (6) yields a desilication efficiency of 75.00%, with an A/S ratio of leached residue of 3.40.

From the silica leaching efficiency shown in Figure 4, we can deduce that the reaction mechanism of kaolinite when the calcination temperature is between 960–1120 °C probably adheres to Formula (6). When compared with pure kaolin, coal gangue contains diverse proportions of boehmite. Boehmite significantly affects the A/S ratio in the alkaline leached residue products. For the purpose of understanding the influence that different amounts of boehmite in coal gangue have on the A/S ratio of the final product, an analysis of the chemical composition associated with the A/S ratio and desilication efficiency can be carried out through theoretical computations. For instance, when the proportion of boehmite relative to kaolinite is 0%, the computed alumina to silica ratio (A/S) amounts to 3.40, which is equivalent to a silica leaching efficiency of 75.00%. Additionally, if the relative content of boehmite to kaolinite is 10%, the calculated A/S ratio is 4.13, also corresponding to a silica leaching efficiency of 75.00%. In the same vein, when the boehmite content relative to kaolinite is 20%, the theoretical A/S value is 4.86, and the associated silica leaching efficiency remains at 75.00%. Theoretical evaluations indicate that as the boehmite content rises, the calculated A/S experiences a sharp increase, yet the silica leaching efficiency persistently remains at 75.00%. Significantly, the theoretical forecasts are in good agreement with the outcomes of the experimental findings.

In conclusion, the mineral transformation mechanism during coal gangue calcination and alkaline leaching is systematically elucidated through integrated experimental validation, theoretical analysis, and characterization by XRD and SEM, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of the mineral transformation in coal gangue calcination and alkaline leaching.

From the above analysis, it can be concluded that the high-efficiency separation of alumina and silica in coal gangue within the temperature range of 960–1120 °C is due to the decomposition of meta-kaolinite. Specifically, 4 moles of meta-kaolinite break down into 1 mole of poorly crystallized mullite, along with 6 moles of amorphous silica and 1 mole of Al2O3. Moreover, the conversion of 2 moles of boehmite into 1 mole of active Al2O3 at a temperature range of 900–1100 °C also plays an important role in increasing the A/S in the leached residue. The amorphous silica is soluble in alkaline solutions, while the active Al2O3 and poorly crystallized mullite remain insoluble under these leaching conditions.

5. Conclusions

This paper adopts a novel method combining calcination and alkaline leaching to remove amorphous silica from high-alumina coal gangue and analyzes the reaction mechanism of desilication. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

(1) Increasing the calcination temperature from 900 °C to 1200 °C alters the internal phase composition of coal gangue. The distinct phase structures of alumina and silica formed under different temperatures directly influence the efficiency of silica separation. Kaolinite in high-alumina coal gangue first converts to meta-kaolinite, then decomposes into primary mullite, amorphous silica, and Al2O3 at 960–1120 °C; meanwhile, boehmite transforms into γ-Al2O3 at 940–1140 °C. The optimal desilication efficiency is achieved at the recommended calcination temperature range of 960–1120 °C, as primary mullite and Al2O3 remain insoluble, while amorphous silica dissolves under suitable alkaline conditions, thereby enabling efficient silica separation.

(2) The desilication temperature significantly impacts amorphous silica dissolution. Raising the temperature from 55 °C to 95 °C changes the leached residue’s phase composition. Below 70 °C, desilication is incomplete—some amorphous silica dissolves, while the rest remains solid, lowering desilication efficiency. Above 80 °C, primary mullite and Al2O3 react with the alkaline solution, dissolving into sodium aluminate (NaAlO2) and sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) solutions, which in turn triggers the crystallization of zeolite-like phases, also reducing desilication efficiency. A suitable desilication temperature range is identified as 70–80 °C.

(3) The suitable desilication conditions involve a calcination temperature of 1080 °C, a calcination duration of 90 min, an alkaline leaching temperature of 75 °C, an alkali concentration of 200 g/L NaOH, a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:4, and an alkaline leaching time of 4.0 h. With these conditions in place, the alumina content within the calcined coal gangue grew from 45.77% to 66.23% in the leached residue. In contrast, the silica content in the residue following leaching decreased from 51.79% to 19.35%. The silica leaching efficiency is 77.31%, the alumina leaching efficiency is 12.21%, the Na2O content in the leached residue amounts to 1.94%, and the A/S ratio shifts from 0.88 for the coal gangue to 3.42 for the leached residue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and W.M.; methodology, J.H.; software, N.Y.; validation, H.Z.; formal analysis, J.H. and H.Z.; investigation, N.Y.; resources, W.M.; data curation, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, W.M.; visualization, N.Y.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, J.H.; funding acquisition, W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Inner Mongolia Mengtai Group Co., Ltd. for providing equipment support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Zhu, M.M.; Cheng, F.C.; Zhang, D.K. Interactions of coal gangue and pine sawdust during combustion of their blends studied using differential thermos-gravimetric analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, C. Effect of calcination condition on the microstructure and pozzolanic activity of calcined coal gangue. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2016, 146, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Mei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Xie, D.; Xia, J.; Nie, Y. Novel desulfurization technology by employing coal gangue slurry as an absorbent: Performance and mechanism study. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J. Comprehensive utilization and environmental risks of coal gangue: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 117946–117963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, F.; Zhong, Q.; Bao, H.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Separation of aluminum and silica from coal gangue by elevated temperature acid leaching for the preparation of alumina and SiC. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 155, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z. Efficient separation of silica and alumina in simulated CFB slag by reduction roasting-alkaline leaching process. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, X.; Du, F.; Tan, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Three-dimensional distribution and oxidation degree analysis of coal gangue dump fire area: A case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiao, K.; Wang, X.; Lv, Z.; Mao, M. Evaluating the distribution and potential ecological risks of heavy metal in coal gangue. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 18604–18615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wan, J.; Sun, H.; Li, L. Investigation on the activation of coal gangue by a new compound method. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Yang, L. Study on the release characteristics of chlorine in coal gangue under leaching conditions of different pH values. Fuel 2018, 217, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wen, Q.; Hu, L.; Gong, M.; Tang, Z. Feasibility study on the application of coal gangue as landfill liner material. Waste Manag. 2017, 63, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. Environmental investigation on co-combustion of sewage sludge and coal gangue: SO2, NOx and trace elements emissions. Waste Manag. 2016, 50, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.M.; Lee, N.K.; Lee, H.K. Circulating fluidized bed combustion ash as controlled low-strength material (CLSM) by alkaline activation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, G.; Wu, S.; Lam, P.K.S. The environmental characteristics of usage of coal gangue in bricking-making: A case study at Huainan, China. Chemosphere 2014, 95, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Bian, Z.; Dong, J.; Lei, S. Soil properties in reclaimed farmland by filling subsidence basin due to underground coal mining with mineral wastes in China. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2014, 24, 2627–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhu, M.; Gao, J. Performance of microwave-activated coal gangue powder as auxiliary cementitious material. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 2799–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Wu, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, M. Preparation of solid-waste-based pervious concrete for pavement: A two-stage utilization approach of coal gangue. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 125962–125975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lü, G.; Zhang, T.; Gong, Y. Kinetics of alumina extraction from coal gangue by hydrochloric acid leaching. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 1932–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Li, G.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Rao, M.; Jiang, T. Extraction and value-added utilization of alumina from coal fly ash via one-step hydrothermal process followed by carbonation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yan, K.; Cui, L.; Cheng, F. Improved extraction of alumina from coal gangue by surface mechanically grinding modification. Powder Technol. 2016, 302, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lv, H.; Yang, X.; Cheng, F. AlCl3·6H2O recovery from the acid leaching liquor of coal gangue by using concentrated hydrochloric inpouring. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 151, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, G.; Jiang, T.; Peng, Z.; Rao, M.; Zhang, Y. Conversion of coal gangue into alumina, tobermorite and TiO2-rich material. J. Cent. South Univ. 2016, 23, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Deng, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, C.; Shi, C.; Zeng, M. Extraction of alumina from alumina rich coal gangue by a hydro-chemical process. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 7, 192132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Yang, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, L.; Ma, X. Reaction behaviour of Al2O3 and SiO2 in high alumina coal fly ash during alkali hydrothermal process. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 2065–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Pan, J.; He, X.; Shi, S.; Long, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, C. Study on modes of occurrence and selective leaching of lithium in coal gangue via grinding-thermal activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Cheng, F. Novel process of alumina extraction from coal fly ash by pre-desilicating—Na2CO3 activation—Acid leaching technique. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 169, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Cheng, S.; Zhu, F.; Tan, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Miao, S. Digesting high-aluminum coal fly ash with concentrated sulfuric acid at high temperatures. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 180, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemi, A.; Ndlovu, S.; Sibanda, V.; van Dyk, L.D. Extraction of alumina from coal fly ash using an acid leach-sinter-acid leach technique. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 157, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Ji, X.; Sarker, P.K.; Tang, J.; Ge, L.; Xia, M.; Xi, Y. A comprehensive review on the applications of coal fly ash. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015, 141, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Teng, W.; Wang, X.; Qin, J.; Xu, P.; Li, P. Alkali desilicated coal fly ash as substitute of bauxite in lime-soda sintering process for aluminum production. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2010, 20, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Xia, M.; Sarker, P.K.; Chen, T. A review of the alumina recovery from coal fly ash, with a focus in China. Fuel 2014, 120, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ma, S.; Shen, S.; Xie, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y. Research and industrialization progress of recovering alumina from fly ash: A concise review. Waste Manag. 2016, 60, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Y. Efficient separation of alumina and silica in reduction-roasted kaolin by alkali leaching. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Y. Reaction behavior of kaolinite with ferric oxide during reduction roasting. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Jiang, T.; Li, G.; Fan, X.; Huang, Z. Activation and removal of silicon in kaolinite by thermochemical process. Scand. J. Metall. 2004, 33, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. The processing of high silica bauxites -Review of existing and potential processes. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 98, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xie, M.; Yu, G.; Ke, C.; Zhao, H. Study on calcination catalysis and the desilication mechanism for coal gangue. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 10318–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Gong, C.; Li, D. Study on structural characteristic and mechanical property of coal gangue in activation process. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 32, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yan, K.; Cui, L.; Cheng, F.; Lou, H.H. Effect of Na2CO3 additive on the activation of coal gangue for alumina extraction. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2014, 131, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Liu, S.; Jing, Y. Microwave activation of coal gangue for Al compound. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 592, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barin, I. Thermochemical Data of Pure Substances; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 1995; ISBN 3527287450. [Google Scholar]

- Souri, A.; Golestani-Fard, F.; Naghizadeh, R.; Veiseh, S. An investigation on pozzolanic activity of Iranian kaolins obtained by thermal treatment. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 103, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Pan, J.; Long, X.; He, X.; Shi, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, C. Study on the leaching behavior differences of rare earth elements from coal gangue through calcination-acid leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 344, 127222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J. Thermal kinetics analysis of coal-gangue selected from Inner Mongolia in China. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 131, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Ma, B.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. Extraction of valuable components from coal gangue through thermal activation and HNO3 leaching. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 113, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Min, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Gao, Y. Improved holding and releasing capacities of coal gangue toward phosphate through alkali-activation. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.; Turturro, A.; Riani, P.; Montanari, T.; Finocchio, E.; Ramis, G.; Busca, G. Bulk and surface properties of commercial kaolins. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Li, X.; Xu, P.; Liu, Q. Thermal activation and structural transformation mechanism of kaolinitic coal gangue from jungar coalfield, inner mongolia, China. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 223, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Annabi-Bergaya, F.; Tao, Q.; Fan, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, J.; He, H.; Chen, T. A combined study by XRD, FTIR, TG and HRTEM on the structure of delaminated Fe-intercalated/pillared clay. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 324, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Frost, R.L. Delamination of kaolinite–potassium acetate intercalates by ball-milling. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 348, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Yang, J.; Ma, S.; Frost, R.L. The thermal behavior of kaolinite intercalation complexes—A review. Thermochim. Acta 2012, 545, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Frost, R.L. Thermal behavior and decomposition of kaolinite–potassium acetate intercalation composite. Thermochim. Acta 2010, 503–504, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).