The Migration Phenomenon of Metal Cations in Vein Quartz at Elevated Temperatures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Equipment for Testing

2.2. Experimental Method

2.3. Characterization Methods

3. Result and Discussion

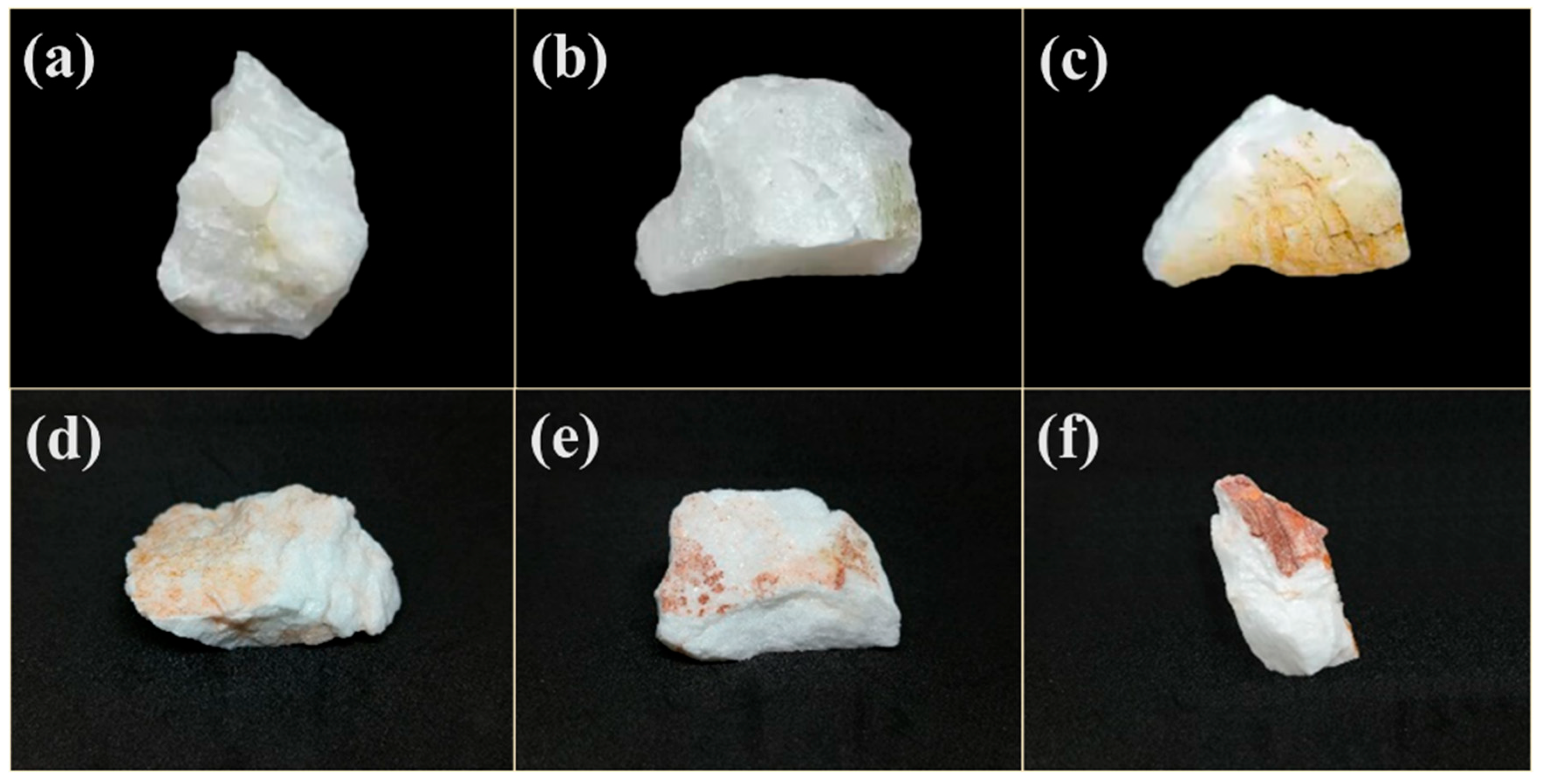

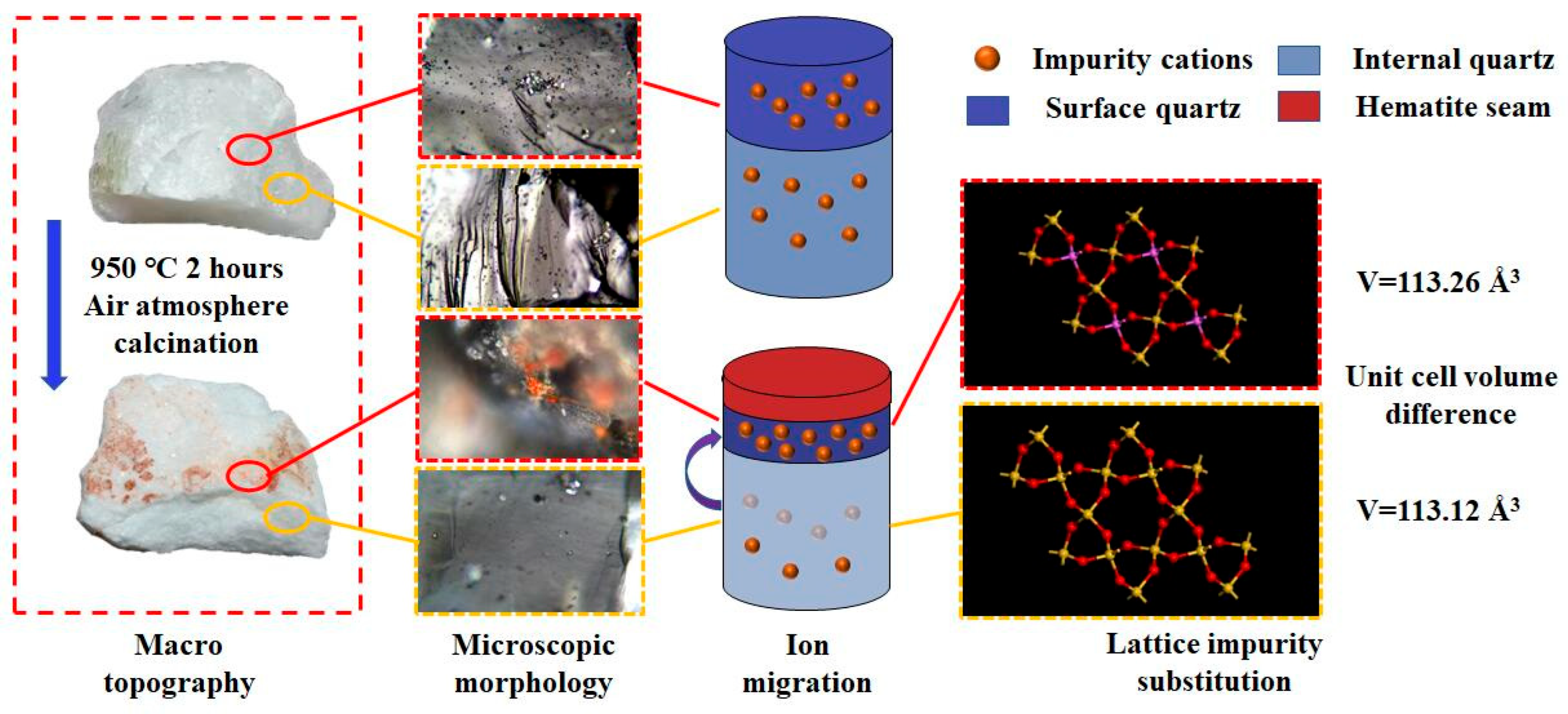

3.1. The Change in Morphology Before and After Calcination

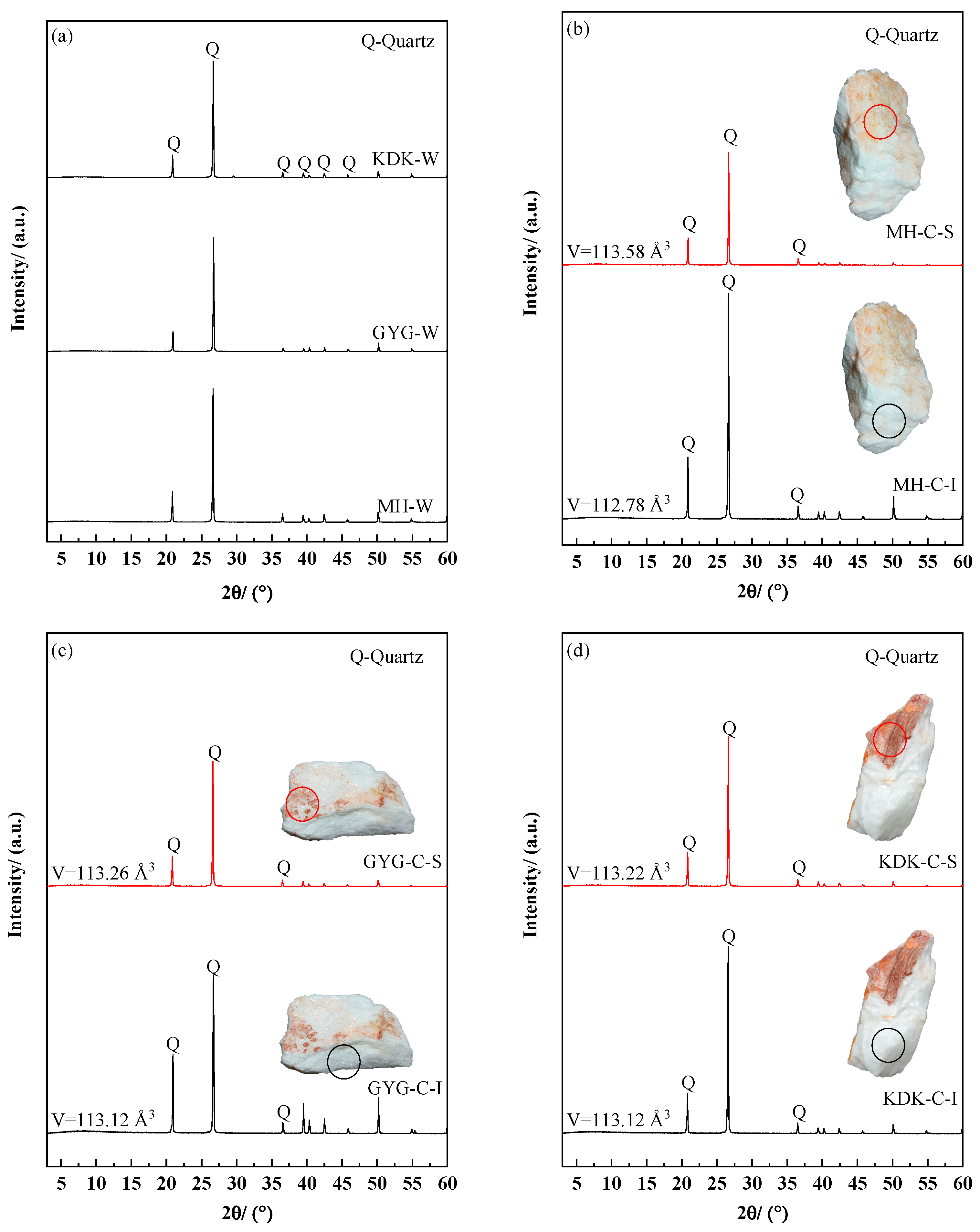

3.2. The Change in Phase Structure Before and After Calcination

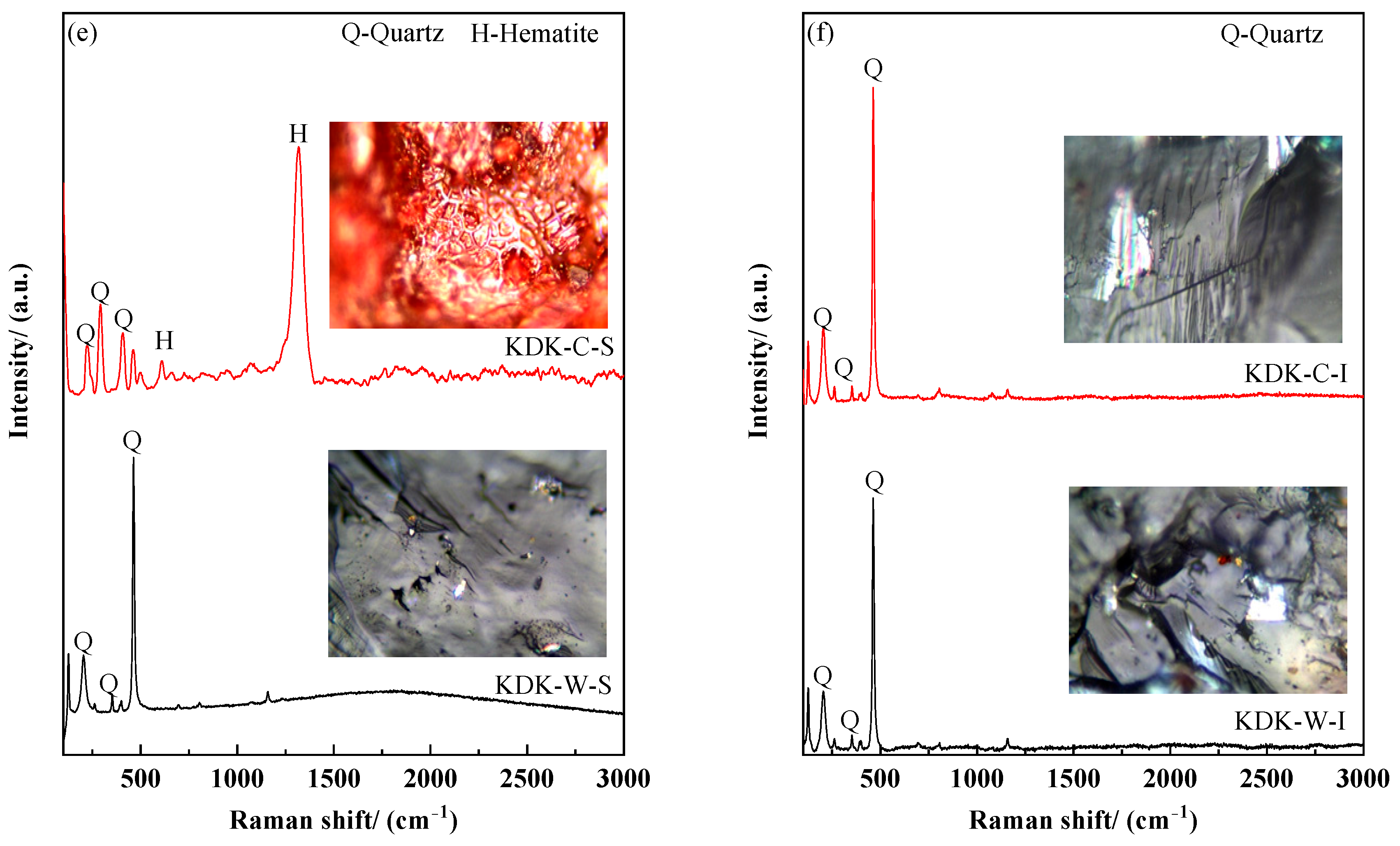

3.3. Changes in Raman Spectra Before and After Calcination

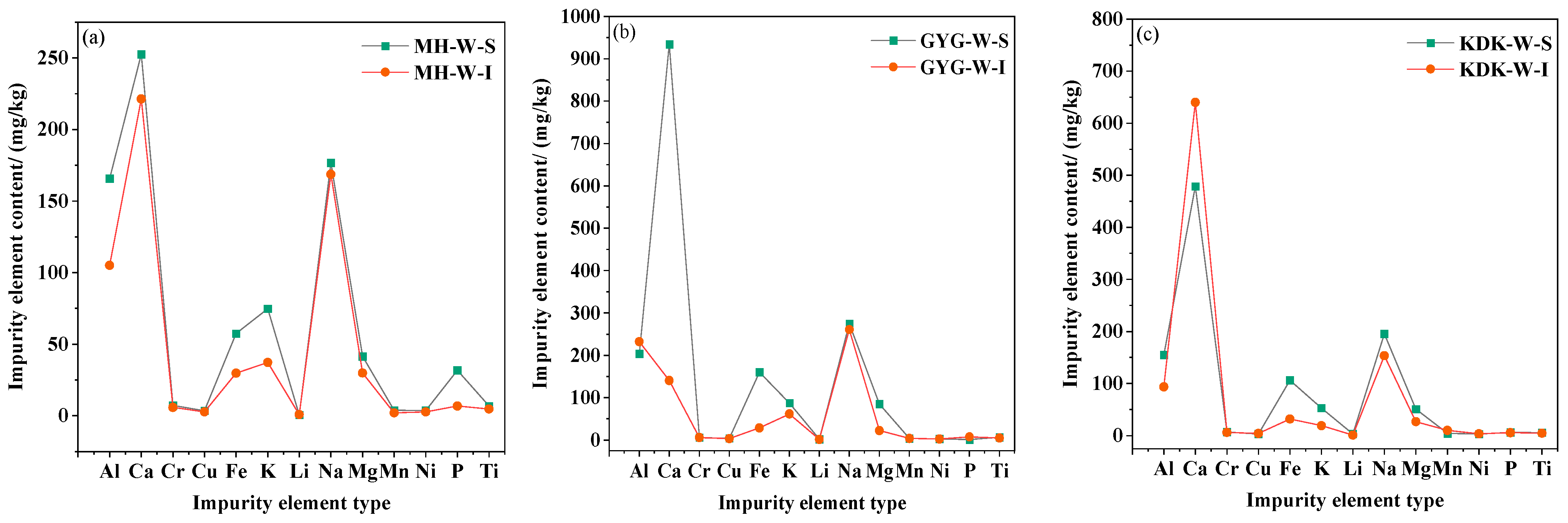

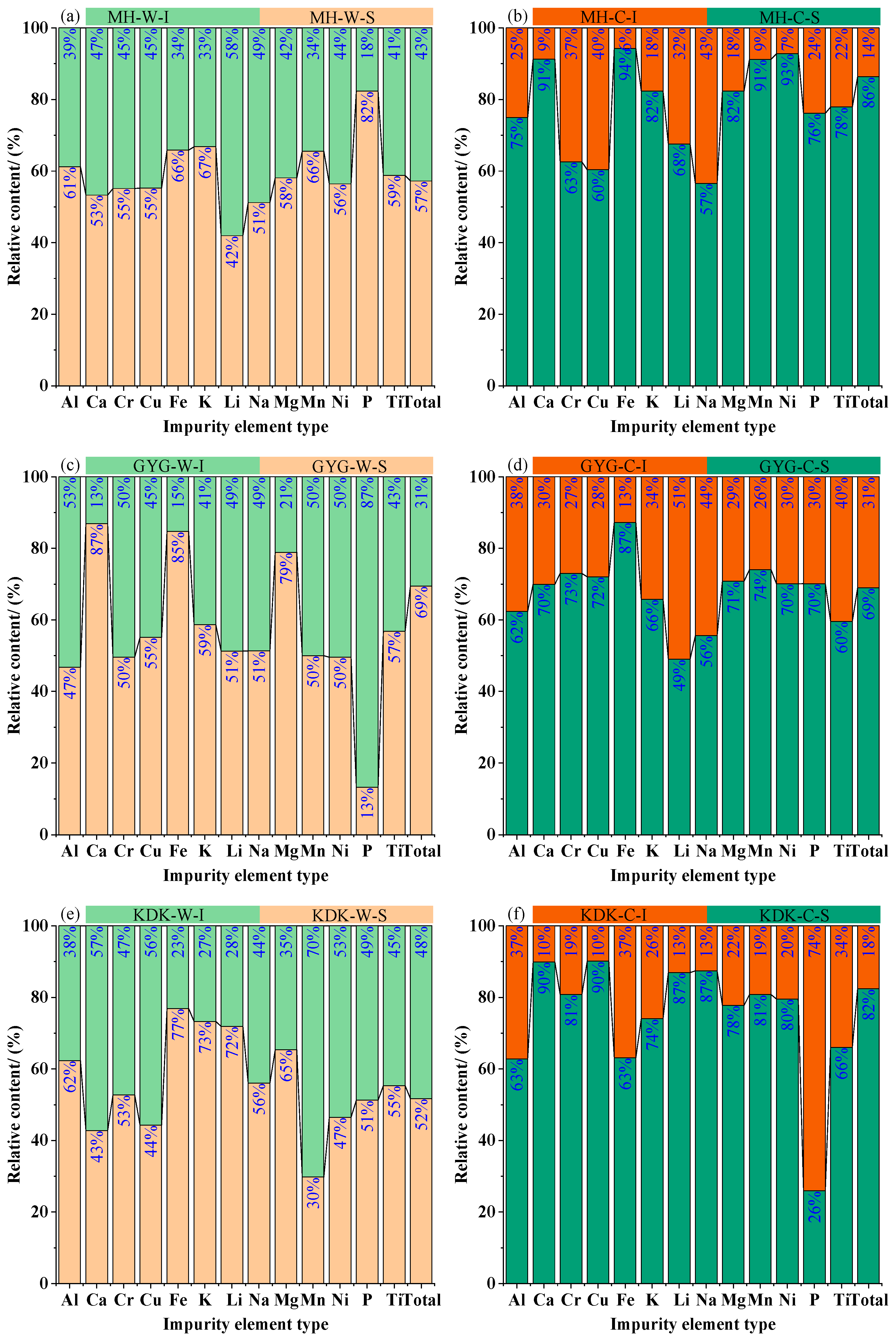

3.4. Changes in Metal Cations Before and After Calcination

3.5. Impurity Migration Process

3.6. Experimental Verification

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Major chemical composition analysis and macroscopic morphology characterization indicate that vein quartz exhibits excellent purification potential in terms of impurity element control. All three groups of vein quartz samples achieve a purity of 2N grade, serving as suitable raw materials for high-purity quartz production. Furthermore, a reddish-brown adherent layer forms on the quartz surface after calcination, providing macroscopic evidence for subsequent phase analysis.

- (2)

- Based on the XRD and Raman spectroscopy results, the unit cell volume of the quartz surface layer after calcination is significantly larger than that of the internal region. Moreover, the layered substance covering the quartz surface at the macroscopic scale is confirmed as a hematite layer through phase matching, revealing the evolutionary characteristics of surface phases during the calcination process.

- (3)

- Trace chemical composition analysis demonstrates a distinct migration phenomenon of internal cations toward the surface during calcination, with the impurity element content on the surface of calcined vein quartz samples accounting for more than 80% of the total content. Integrating multiple characterization techniques, it is inferred that after cation migration induced by calcination, a hematite adherent layer forms on the quartz surface, and Lattice-bound impurities are enriched in the surface layer. This implies that by removing the surface layer of calcined vein quartz, the internal quartz with low lattice impurity content can be utilized as a high-quality raw material for high-purity quartz preparation.

- (4)

- By regulating the impurity migration process of quartz and adopting the autogenous grinding and sieving process for surface tailing removal of calcined quartz, the purification potential of vein quartz raw materials can be significantly enhanced, thereby enabling the preparation of high-purity quartz sand with a grade of 4N or higher. This process features both simplicity and economy, making it applicable to practical industrial production. It realizes the high-value utilization of conventional vein quartz and effectively alleviates the demand pressure for high-purity quartz sand in fields such as photovoltaics and communications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, R.; Tang, C.; Ni, W.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X. Research Status and Challenges of High-Purity Quartz Processing Technology from a Mineralogical Perspective in China. Minerals 2023, 13, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Han, Y.; Li, Z. Review of advanced purification technologies for high-purity quartz materials. Mater. Res. Bull. 2026, 196, 113904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, K.; Alfonso, P.; Oliva, J.; Sampaio, C.H.; Anticoi, H. Perspectives for High-Purity Quartz from European Resources. Minerals 2025, 15, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Han, Y.-F.; Zhang, Q. Development Current Situation, Consumption and Market Forecast of High Purity Quartz. Build. Mater. World 2023, 44, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Kong, H. Current Situation and Development Suggestions of China’s High-Purity Quartz Industry Chain. Northwestern Geol. 2023, 56, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhu, D.; Pan, J.; Li, S.; Guo, Z.; Xu, X. Innovative process for the extraction of 99.99% high-purity quartz from high-silicon iron ore tailings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, D.; Chi, R. Crystal structure transformation and lattice impurities migration of quartz during chlorine roasting. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tan, X.; Yi, Y.; Tan, Q.; Liu, L. Characteristics of high-purity quartz raw materials for crucibles and exploration of key purification technologies. Miner. Eng. 2025, 231, 109446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, W.; Xu, K.; Wang, S.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Z.; Miao, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W. Progress of joint process research on purification of high purity quartz sand. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 117, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Xia, Z.; Li, W.; Lei, S. Influences of Na2CO3 roasting and H3PO4 hot-pressure leaching on the purification of vein quartz to achieve high-purity quartz. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 218, 106065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, G.; Wei, L. Preparation of High-Purity Quartz by Roasting–Water Quenching and Ultrasound-Assisted Acid Leaching Process. Minerals 2025, 15, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, S.; Zhang, G.; Ai, G.; Wei, K.; Ma, W. Transformation mechanism of Fe impurities during Fe removal from vein quartz via low-temperature sulfuric acid roasting. Miner. Eng. 2026, 235, 109807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Wang, Q.; Ku, J.; Shang, H.; Shen, Z. Purification Technologies for High-Purity Quartz: From Mineralogy to Applications. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branlund, J.M.; Hofmeister, A.M. Thermal diffusivity of quartz to 1,000 °C: Effects of impurities and the α-β phase transition. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2007, 34, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q. Crystal Chemical Characteristics of Vein Quartz and Its’ Relationship of Making High Purity Quartz. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, D.H.A.; dos Santos, L.; de Pinho Guimarães, I.; de Assis Batista, L.; Araújo, B.S.; Amorim, J.V.A.d.; Queiroga, G.N. Petrological characterization of Fe–Ti oxides in metamafic rocks from the Nw borborema province, Ne Brazil. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2023, 122, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.D.; Sheremet, E.; Deckert-Gaudig, T.; Chaneac, C.; Hietschold, M.; Deckert, V.; Zahn, D.R. Surface-and tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy reveals spin-waves in iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 9545–9551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wei, Y.; Liu, B.; Meng, Y.; Qiu, H.; Lei, S.M.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.B. A Critical Review on the Mineralogy and Processing for High-Grade Quartz. Min. Metall. Explor. 2020, 37, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, S.; Wu, J.; Wu, D.; Wei, K.; Ma, W. Effect of quartz crystal structure transformations on the removal of iron impurities. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 204, 105715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampides, G.; Vatalis, K.; Baklavaridis, A.; Karayannis, V.; Benetis, N.-P. Chemical and Mineralogical Analysis of High-Purity Quartz from New Deposits in a Greek Island, for Potential Exploration. EUREKA Phys. Eng. 2020, 4, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, J.; Wei, M.; Li, F.; Ban, B.; Li, J. Effect of impurity content difference between quartz particles on flotation behavior and its mechanism. Powder Technol. 2020, 375, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapiaggi, M.; Pagliari, L.; Pavese, A.; Sciascia, L.; Merli, M.; Francescon, F. The formation of silica high temperature polymorphs from quartz: Influence of grain size and mineralising agents. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 4547–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, M.; Malaspina, N.; Frezzotti, M.L. Threshold size for fluid inclusion decrepitation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2015, 120, 7396–7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhang, G.; Ouyang, B.; Liu, Z.; Ren, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H. Study on high temperature chlorination purification of quartz sand. Ind. Miner. Process. 2019, 49, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Tan, X.; Wu, Z. Research Progress on Impurity Characteristics and Deep Chemical Purification Technology in High-purity Quartz. Conserv. Util. Miner. Resour. 2022, 42, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hühn, C.; Erlebach, A.; Mey, D.; Wondraczek, L.; Sierka, M. Ab Initio energetics of Si-O bond cleavage. J. Comput. Chem. 2017, 38, 2349–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component (%) | SiO2 | CaO | P2O5 | SO3 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | BaO | MgO | Cr2O3 | Cs2O | Ignition Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH-W | 99.57 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.02 | * | 0.16 | * | * | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.39% |

| GYG-W | 99.68 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | * | * | 0.58% |

| KDK-W | 99.32 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.02 | * | 0.02 | * | * | 0.62% |

| Sample Name | Unit Cell Volume (Å3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Samples | Internal Samples | |

| MH-C | 113.58 | 112.78 |

| GYG-C | 113.26 | 113.12 |

| KDK-C | 113.22 | 113.12 |

| Group a | Group b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Workshop Section | Parameter | Workshop Section | Parameter |

| crushing | Jaw crusher with zirconia liner to break down to 10 mm. | crushing | Jaw crusher with zirconia liner to break down to 10 mm. |

| calcination | The samples were calcined at 900 °C for 120 min in oxygen atmosphere. | calcination | The samples were calcined at 900 °C for 120 min in oxygen atmosphere. |

| grinding | The sample was ground to 70~150 mesh using a zirconia lining disc prototype. | autogenous grinding | Autogenous grinding for 5 min using zirconia-lined self-grinding mill. |

| scrubbing | Scrub with 5% mass fraction of oxalic acid solution. | screening | Fine tailings with particle size less than 100 mesh are sieved and discharged. |

| magnetic separation | Using a wet high intensity magnetic separator with a magnetic flux of 23,000 Oe, magnetic separation is performed once at a pulp concentration of 20%. | grinding | The sample was ground to 70~150 mesh using a zirconia lining disc prototype. |

| flotation | Slurry concentration 20%, pH ≈ 2.5, regulator HF, collector dodecylamine. | flotation | Slurry concentration 20%, pH ≈ 2.5, regulator HF, collector dodecylamine. |

| acid pickling | 0.4 mol/L HF, 1.2 mol/L HCl, solid–liquid ratio of 1:1, acid leaching at 80 °C for 4 h. | acid pickling | 0.4 mol/L HF, 1.2 mol/L HCl, solid–liquid ratio of 1:1, acid leaching at 80 °C for 4 h. |

| Element | Al | Ca | Cr | Cu | Fe | K | Li | Na | Mg | Mn | Ni | P | Ti | SUM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDK-a | 351.92 | 134.64 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 22.10 | 8.76 | 1.44 | 8.55 | 14.20 | 1.90 | 0.62 | 9.23 | 2.49 | 556.33 |

| KDK-b | 36.58 | 10.97 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 5.73 | 3.23 | 0.56 | 7.04 | 4.50 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 3.24 | 2.51 | 75.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Peng, T. The Migration Phenomenon of Metal Cations in Vein Quartz at Elevated Temperatures. Minerals 2025, 15, 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121318

Wang Z, Sun H, Liu B, Huang Y, Peng T. The Migration Phenomenon of Metal Cations in Vein Quartz at Elevated Temperatures. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121318

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhenxuan, Hongjuan Sun, Bo Liu, Yehao Huang, and Tongjiang Peng. 2025. "The Migration Phenomenon of Metal Cations in Vein Quartz at Elevated Temperatures" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121318

APA StyleWang, Z., Sun, H., Liu, B., Huang, Y., & Peng, T. (2025). The Migration Phenomenon of Metal Cations in Vein Quartz at Elevated Temperatures. Minerals, 15(12), 1318. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121318