Abstract

Tennantite (Cu12As4S13) and enargite (Cu3AsS4) are two important minerals that simultaneously contain copper and arsenic. Detailed studies of their structure and properties are crucial for understanding their oxidation, flotation, and leaching. This study investigates the crystal structures, electronic properties, and reactivity of these two copper-arsenic minerals from the perspectives of atomic bonding, charge, density of states, and d-orbital splitting. The results indicate that tennantite is a crystal with mixed Cu valence states of +2 and +1 (predominantly +1), while the Cu in enargite is in the +1 state. The valence state of As in tennantite (+3) is lower than that in enargite (+5). Orbital energy level calculations show that the energy gaps between the copper d-orbitals are small in both minerals, indicating strong electron delocalization and, consequently, strong covalent character in the crystals, which is also confirmed by Mulliken bond population calculations. The presence of arsenic is the reason for the enhanced covalency. It is noteworthy that tennantite exhibits stronger covalency. The Cu 3d and As 4p electrons in tennantite are more electronically active than those in enargite. In tennantite, the strong d-electron delocalization caused by d-p hybridization between Cu and S leads to similar 3d electronic properties between 3-coordinated and 4-coordinated Cu. The energies of the five d-orbitals of the 4-coordinated Cu in enargite are lower than those of the 4-coordinated Cu in tennantite, which may affect the ability of Cu 3d electrons to enter the empty orbitals of S atoms in sulfur-containing collectors to form π back-bonding, thereby reducing the collecting ability of enargite. On the other hand, the splitting energy of the 4-coordinated Cu 3d orbitals in enargite is significantly smaller than that in tennantite, making the structure less stable and, thus, potentially more prone to dissolution.

1. Introduction

With the increasing demand for copper, the mining of low-grade copper ores and arsenic-bearing copper ores has become increasingly important. Schwartz et al. [1] indicated that many processing plants face the challenge of treating copper ores containing more than 0.2% arsenic. In nature, besides the commonly encountered arsenopyrite, the main arsenic-bearing minerals include two copper-arsenic minerals, namely tennantite (Cu12As4S13) and enargite (Cu3AsS4). These arsenic-bearing minerals often coexist with copper sulfides such as chalcopyrite and chalcocite [2]. During the flotation process, arsenic often enters the copper concentrate. The presence of arsenic adversely affects the quality of the flotation products and also has negative impacts on the subsequent metallurgical processes and the environment. However, the copper contained within these copper-arsenic minerals holds significant economic value. Thus, how to utilize these copper-arsenic minerals has become an important consideration.

Tennantite (ideal formula Cu12As4S13) is part of the tetrahedrite group of minerals. The tetrahedrite group has chemical variability. The crystal contains isomorphic impurities, and the fomula can be written as A6(B4C2)Σ6D4Y12Z, where A = Cu+ and Ag+; B = Cu+ and Ag+; C = Zn2+, Fe2+, Hg2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, Cu2+, Cu+, and Fe3+; D = Sb3+, As3+, Bi3+, and Te4+; Y = S2− and Se2−; and Z = S2− and Se2− [3]. Tennantite is an end-member of the tetrahedrite (Cu12Sb4S13) solid solution series, formed when As fully substitutes Sb [4,5,6,7]. In practice, tennantite often contains antimony (Sb) and belongs to the arsenic-rich category. It is classified as tennantite when the arsenic content exceeds the antimony content, and becomes tetrahedrite when antimony predominates over arsenic. Enargite (Cu3AsS4) possesses a wurtzite (ZnS) structure, where Cu and As substitute for the Zn positions [8]. The copper content in tennantite and enargite crystals is 51.75% and 48.61%, respectively, while the arsenic content is 20.22% and 18.99% respectively. This means that both the Cu and As contents in tennantite are slightly higher than those in enargite. Furthermore, the copper content in these two minerals is significantly higher than that in the common copper mineral chalcopyrite (Cu: 34.78%), while their arsenic content is much lower than that in the common arsenic mineral arsenopyrite (As: 46.01%). Generally, it is believed that in tennantite, Cu is in the +1 oxidation state, As is +3, and S is −1. However, Reddy et al. [9], based on electron paramagnetic resonance and UV-VIS absorption spectroscopy, suggested the presence of copper in the +2 oxidation state, although this could be a result of oxidation [8]. Studies by Rossi et al. [10] showed that in air, copper and arsenic in enargite bond with oxygen rather than sulfur. The oxidation of tennantite also primarily involves the formation of Cu-O and As-O bonds [11].

Their properties are quite similar to those of other non-arsenic copper minerals, making flotation separation relatively difficult. A more promising approach involves separation after selective oxidation [8,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Research by Fullston et al. [17] indicated that under pH 11 conditions, the oxidation rates of copper minerals and copper-arsenic minerals follow this order: chalcocite > tennantite > enargite > covellite > pyrite. It can be observed that the oxidation rate of tennantite is greater than that of enargite. Furthermore, the elemental dissolution behavior of tennantite and enargite also differs. Studies by Sasaki et al. [2] in solutions of different pH showed that after one hour of H2O2 oxidation under strongly acidic conditions (pH 2), the dissolved Cu concentration from tennantite was much higher than from enargite, while the dissolved S content from enargite was far greater than from tennantite. Additionally, for tennantite, Cu dissolved preferentially to As and S, whereas the opposite was true for enargite. In contrast, in pH 5 and pH 11 solutions, the dissolved Cu content from enargite was much higher than from tennantite.

The above results indicate that although both minerals contain the same elements, their different crystal structures likely lead to significant differences in properties and elemental reactivity, resulting in distinct oxidation behaviors. Therefore, studying their structures and properties will be highly beneficial for understanding oxidation, flotation, and leaching processes. This paper employs first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) to investigate in detail the crystal structures and electronic properties of tennantite and enargite, including bonding, coordination, charge, density of states, d-orbital splitting, etc. The findings are intended to provide insights helpful for the flotation separation or leaching of these two minerals.

2. Calculation Methods

The calculations were performed using the CASTEP module, based on density functional theory (DFT) with the GGA-PW91 functional and ultrasoft pseudopotentials. A plane-wave cut-off energy of 400 eV was determined through convergence testing. Spin polarization was performed in the calculations. The self-consistent field (SCF) convergence tolerance was set to 2.0 × 10−6 eV/atom, and the maximum atomic displacement was less than 2.0 × 10−3 Å. During geometry optimization, the convergence criteria for the maximum energy change, maximum force, and maximum stress were set to 2 × 10−5 eV/atom, 0.05 eV/Å, and 0.1 GPa, respectively. A 4 × 4 × 4 k-point mesh was generated using the Monkhorst–Pack scheme. The valence electron configurations used in the pseudopotential calculations for Cu, As, and S were 3d104s1, 4s24p3, and 3s23p4, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystal Structures of Tennantite and Enargite

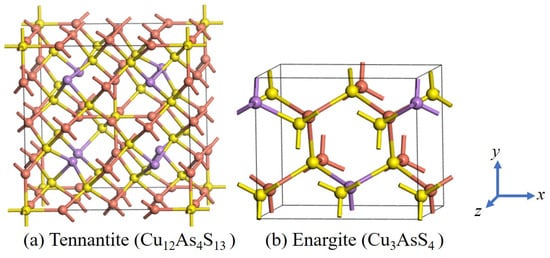

The chemical formulas of tennantite and enargite are Cu12As4S13 and Cu3AsS4, respectively. The former belongs to the cubic crystal system, while the latter belongs to the orthorhombic crystal system. Their structural models are shown in Figure 1. The calculated lattice constant for tennantite is a = b = c = 10.254 Å, which is close to the experimental value of a = b = c = 10.190 Å [18], with a minor error of only 0.68%. For enargite, the calculated lattice constants are a = 7.448 Å, b = 6.441 Å, and c = 6.162 Å, also close to the experimental values (a = 7.426 Å, b = 6.452 Å, c = 6.163 Å) [19], with errors within a very small margin of 0.3%. These results confirm the reliability of the calculations.

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of tennantite and enargite.

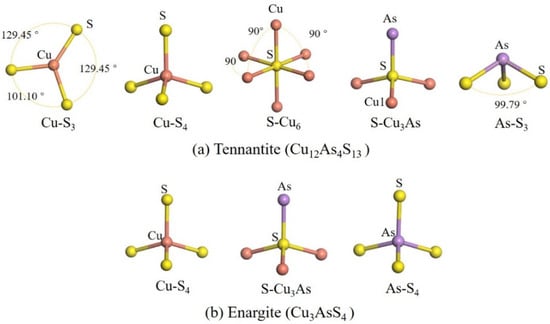

Figure 2 shows the coordination environments of the atoms. In tennantite, Cu atoms exhibit both 3-fold and 4-fold coordination, present in equal amounts [4], forming planar triangular and tetrahedral structures, respectively. As atoms are 3-coordinated, resembling the ammonia molecule structure. S atoms show both 4-fold and 6-fold coordination, forming tetrahedral and octahedral structures. In enargite, all Cu, As, and S atoms are 4-coordinated.

Figure 2.

Coordination environments of atoms in the crystal structures.

Regarding bonding, in both minerals, Cu atoms bond only with S atoms and not directly with As atoms, while S atoms bond with both Cu and As atoms. However, in tennantite, S atoms form a 6-coordinated structure only when bonded exclusively to Cu atoms; when bonded to both Cu and As atoms, they form a 4-coordinated structure. The ratio of these two S coordination types is 1:12, meaning the 4-coordinated S atoms constitute the majority.

It can be observed that the coordination environments of Cu and As differ significantly between the two minerals, while the overall S environments are relatively similar (with the 6-coordinated S in tennantite being very rare). In tennantite, 3-coordinated (planar triangle) and 4-coordinated (tetrahedral) Cu atoms each account for half of the total Cu content, whereas in enargite, all Cu atoms are 4-coordinated (tetrahedral). This structural difference may influence their reactivity. The planar triangle structure represents a coordinatively unsaturated system for Cu, with potential coordination sites above and below the copper center that can interact with molecules without requiring the dissociation of an existing ligand to create space. This could lead to a lower energy barrier for molecular interactions. These factors suggest that the reactivity of these sites may be higher.

For the As in tennantite, which has a structure analogous to the arsenic hydride molecule (AsH3). In the presence of oxygen, this might also make it more susceptible to oxidation. These aspects require further surface studies.

Mulliken bond lengths and populations in the crystals were calculated, as shown in Table 1. Bond population shows how the electron density is distributed between atoms. A value greater than zero indicates a bonding interaction, with higher values signifying stronger covalency. Values close to or less than zero may suggest ionic bonding, non-bonding, or anti-bonding interactions.

Table 1.

Mulliken bond populations.

It can be seen that all bond population values are positive, indicating bonding interactions exist between the atoms. Since Cu does not bond directly with As, only Cu-S and As-S bonds are displayed. The population values for As-S bonds are significantly lower than those for Cu-S bonds, indicating their covalent character is weaker compared to Cu-S bonds.

In tennantite, the 3-coordinated Cu-S bonds are of two types. One has a bond length of 2.236 Å and a population value of 0.61, indicating very strong covalency. The other has a bond length of 2.270 Å and a population value of 0.35, representing the weakest covalency, even weaker than the longer 4-coordinated Cu-S bond (2.314 Å, population value 0.47). Further observation reveals that the S atoms in the weakest covalent Cu-S bond are in S-Cu6 configurations (i.e., S coordinated to six Cu atoms forming an octahedron), whereas the S atoms in the stronger covalent Cu-S bonds (population values 0.61 and 0.47) are in S-Cu3As configurations (i.e., S coordinated to three Cu atoms and one As atom forming a tetrahedron). This suggests that the arsenic environment enhances the covalency of the Cu-S bonds, potentially leading to increased hydrophobicity of the mineral.

Unlike tennantite, the Cu-S4 coordination in enargite is a distorted tetrahedron, with bond lengths ranging from 2.027 Å to 2.332 Å and population values between 0.38 and 0.56. The maximum bond length is longer than that in tennantite (2.314 Å), and the maximum population value is lower than that in tennantite (0.61). However, the minimum population value is higher than that in tennantite (0.35). Furthermore, the As-S bonds in enargite are also non-uniform, with lengths ranging from 2.252 Å to 2.265 Å and population values between 0.04 and 0.26. Overall, it is thought that tennantite exhibits stronger covalency, suggesting better hydrophobicity.

It is worth noting that the maximum Cu-S bonds in tennantite and enargite are larger than those in chalcopyrite, while the minimum Cu-S bonds are smaller than those in chalcopyrite [20]. Additionally, the As-S bond lengths are much shorter than those in the arsenopyrite crystal [21]. We have conducted research on chalcopyrite and arsenopyrite and found that the covalent property of Cu-S in tennantite and enargite is stronger than that in chalcopyrite, while that of As-S is weaker than that in arsenopyrite [22,23]. It is once again confirmed that the presence of arsenic can increase the covalent property of crystals.

3.2. Electronic Properties of Atoms

The Hirshfeld charges of the atoms were analyzed and shown in Table 2. In Tennantite (Cu12As4S13), both the 3-coordinated and 4-coordinated Cu atoms have a charge of +0.14 e. The 3-coordinated As has a charge of +0.17 e. The 4-coordinated S (S-Cu3As) has a charge of −0.17 e, while the 6-coordinated S (S-Cu6) has a charge of −0.27 e. In Enargite (Cu3AsS4), the 4-coordinated Cu and As have charges of +0.13 e and +0.26 e, respectively. The charges of the 4-coordinated S atoms range from −0.15 e to −0.17 e. It can be observed that the charge differences for Cu and S atoms between the two crystals are relatively small (although the charge of the 6-coordinated S in tennantite differs more significantly from the 4-coordinated S, it constitutes a very small fraction and can thus be neglected). However, there is a considerable difference in the charge of the As atoms.

Table 2.

Hirshfeld charges of atoms.

The charge differences alone cannot determine the variation in copper valence states; therefore, the issue of copper valence will be discussed in more detail later. The following section will discuss the oxidation state of arsenic. The As in tennantite has a lower positive charge (+0.17 e), indicating a lower oxidation state compared to the As in enargite (charge of +0.26 e). Previous bond length calculation results showed that the As-S bond length in 3-coordinated As in tennantite (2.283 Å) is significantly longer than the As-S bond lengths in 4-coordinated As in enargite (ranging from 2.252 Å to 2.265 Å). This suggests that the As ionic radius in tennantite is larger, corresponding to a lower valence state. These results are consistent with ore-forming practices: enargite forms in high-sulfur and oxidizing environments where As is considered to have a +5 valence state, whereas tennantite forms in reducing environments where the As valence state is generally considered to be +3.

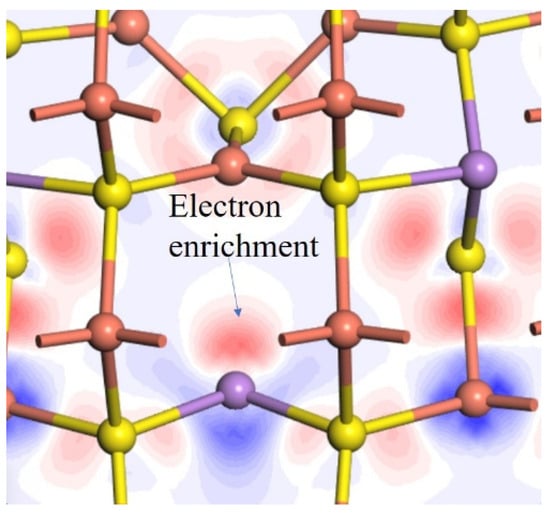

The As atom in tennantite exhibits a 3-coordinated structure analogous to the arsenic hydride molecule (AsH3). The As in AsH3 has a pair of lone electrons and is prone to oxidation. To investigate whether there are also lone pairs of electrons in the As of AsS3, the differential charge density of arsenic was analyzed, as shown in Figure 3. It can be observed that in Tennantite, on the side opposite to the three As-S bonds, there is an electron-rich region (red area), confirming the existence of lone pair electrons on the As atom.

Figure 3.

Electron density difference map of the arsenic atom.

Combining this with the previously analyzed Hirshfeld charge indicates a lower oxidation state. Due to its stronger reducibility, if oxygen or oxidizing agents are present, it is more prone to lose electrons and undergo oxidation, leading to increased hydrophilicity.

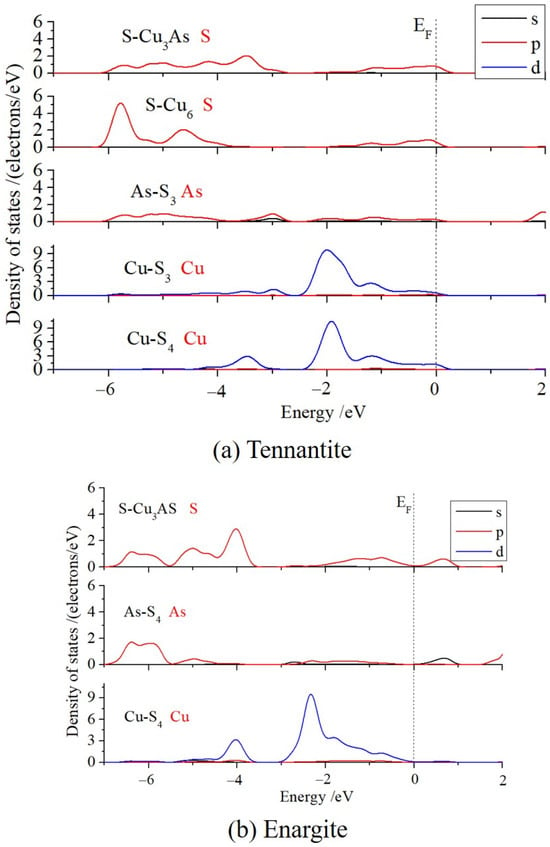

The density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level was calculated (as shown in Figure 4) to analyze the bonding between atoms and the characteristics of the reactive orbitals. The comparative results for the two types of S and the two types of Cu in tennantite were discussed below. The S 3p states of S-Cu6 and S-Cu3As are quite similar near the Fermi level. However, the S 3p of S-Cu6 exhibits a distinct sharp peak in the energy range of −6 eV to −5 eV, whereas the DOS of S 3p for S-Cu3As is flat and has a lower intensity. Similarly, the Cu 3d of Cu-S4 also shows a pronounced DOS peak in the range of −4 eV to −3 eV, while the Cu 3d DOS of Cu-S3 is very small in this region, and the entire distribution is shifted towards higher energies. These results indicate that the 4-coordinated S and 3-coordinated Cu in tennantite are less stable and have higher reactivity compared to the 6-coordinated S and 4-coordinated Cu.

Figure 4.

Density of states of atoms. The Fermi level (EF) is set at zero energy.

The Cu 3d states of the 4-coordinated Cu in enargite are very similar to those of the 4-coordinated Cu in tennantite, but the overall DOS of the former is located at lower energies and lacks electronic states at the Fermi level. This suggests that the copper structure in enargite is more stable, whereas the Cu 3d electrons in tennantite are more active.

Previous charge calculations showed that the Cu charges in both crystals are almost identical, making it impossible to determine their valence states from this alone. However, analysis of the DOS can provide insight. In enargite, the Cu 3d band is fully occupied, lying entirely below the Fermi level (EF), indicating a d10 configuration, i.e., Cu tends to be in the +1 oxidation state. This valence state is consistent with its formula, Cu3+1As+5S4−2. In tennantite, a very small portion of the Cu 3d states crosses the Fermi level, and the 3d band is partially occupied, suggesting the possible presence of a d9 component, i.e., Cu in the +2 oxidation state. However, according to the chemical formula Cu12As4+3S13−2, the average valence of Cu should be +1.17, closer to +1. Therefore, further analysis of the copper valence state is needed. Combining this with the DOS, it can be seen that near the Fermi level, the Cu 3d and S 3p orbitals form strong p-d orbital hybridization, with electrons highly shared between Cu and S, resulting in strong covalent interactions and consequently metallic character. This aligns with the observed metallic conductivity and luster of tennantite. This indicates that strong covalent interactions lead to the delocalization of d electrons, causing the d orbitals to cross the Fermi level. In summary, it can be concluded that the Cu in tennantite is not purely +1 or +2, but rather exists in a mixed valence state dominated by +1, with some +2 character.

The DOS of As 4p in tennantite is low and flat in the range of −6 eV to −4 eV, whereas the As 4p DOS in enargite shows a higher and more concentrated peak at lower energies, between −7 eV and −5.5 eV. This suggests that the arsenic in enargite is more stable, while the arsenic in tennantite is more reactive and potentially more easily oxidized.

Finally, a bonding analysis was performed. It can be observed that the S 3p in S-Cu3As and the Cu 3d in Cu-S4 exhibit strong hybridization in the ranges of −4.5 eV to −3 eV and −1.5 eV to 0 eV, whereas the S 3p in S-Cu6 and the Cu 3d in Cu-S3 show only moderate hybridization within the −1.5 eV to 0 eV range. This indicates stronger covalency in the bonding between the former pair, i.e., the Cu-S bond within the arsenic environment has greater covalent character, which is consistent with the Mulliken bond population analysis.

In enargite, both Cu (Cu-S4) and As (As-S4) bond only with S, while S (S-Cu3As) bonds with both Cu and As. A strong hybridization peak between Cu 3d and S 3p is observed in the range of −5.5 eV to −3.5 eV, with weaker hybridization occurring between −2 eV and 0 eV.

In tennantite, the S 3p in S-Cu3As and the As 4p in As-S3 show weak hybridization from −6 eV to −2.8 eV, and also weak hybridization from −1.5 eV to 0 eV. In contrast, the S 3p in S-Cu3As and the As 4p in As-S4 in enargite exhibit relatively strong hybridization in the range of −7 eV to −5.5 eV, forming a distinct hybridization peak. This indicates that the As-S orbital hybridization in tennantite is weaker but spans a broader energy range, whereas the As-S hybridization in enargite is slightly stronger but confined to a narrower range. Combined with the earlier bond population analysis, the covalent character of the As-S bonds in both crystals is similar.

Compared with the Cu and As in chalcopyrite [22] and arsenopyrite [23], it is shown that the Cu 3d electronic structure of tennantite or enargite near the Fermi level is relatively similar to that of chalcopyrite, but it moves towards the lower energy level As a whole, while As 4p in arsenopyrite is distributed near the Fermi level. These results indicate that the Cu 3d electrons in chalcopyrite and As 4p electrons are more active than in tennantite or enargite.

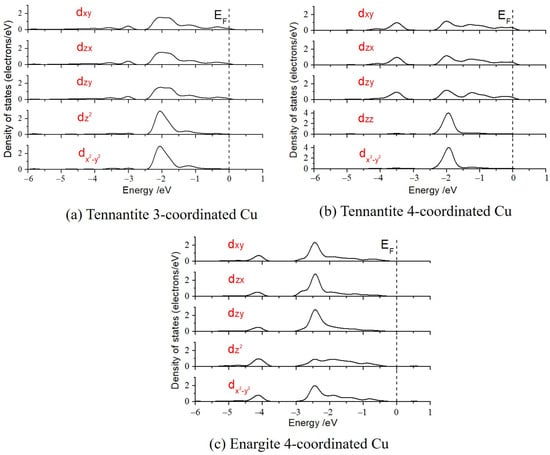

3.3. Splitting of Cu 3d Orbitals in the Crystal Field

The five split d-orbitals were calculated (as shown in Figure 5), and the energy levels of these five d-orbitals were determined using the weight center method, establishing the energy level ordering for the different orbitals, as listed in Table 3. From the perspective of orbital splitting, the d-orbitals of the planar triangle and tetrahedral copper in tennantite can be divided into two groups: dx2-y2 and dz2 form one group, while dxy, dzx, and dyz form another group, with the latter group having lower energy levels. The energy distinction among the d-orbitals of the tetrahedral copper in enargite is less pronounced but can still be categorized into four groups: dz2 has the lowest energy level, followed by dxy, then dx2-y2 and dzx, which are close in energy, and finally dyz with the highest energy level. It is important to note that the energy differences between the d-orbitals for the various copper types are very small, indicating strong electron delocalization.

Figure 5.

Density of states of d-orbital splitting.

Table 3.

Cu 3d orbital energy levels.

It can be observed that in tennantite, the energies of the five d-orbitals for the 4-coordinated tetrahedral Cu are similar to those of the 3-coordinated planar triangle copper. In contrast, the d-orbital energies of the 4-coordinated Cu in enargite are significantly lower than those in tennantite (approximately 0.4 eV higher in tennantite).

The strong d-electron delocalization results in relatively low splitting energies (the energy difference between the highest and lowest energy orbitals) of the Cu d-orbitals in both copper-arsenic minerals. Particularly, the planar triangular Cu exhibits the smallest splitting energy (0.029 eV), while the splitting energy of tetrahedral Cu in tennantite (0.066 eV) is greater than that of Cu in enargite (0.034 eV). The above studies indicated that the oxidation state of copper in tennantite is slightly higher than that in enargite, and Mulliken charge calculations also show that Cu in enargite carries +0.13 e, while Cu in tennantite carries +0.14 e. Under the same ligands and coordination number, a lower oxidation state leads to a smaller splitting energy, resulting in a less stable structure and higher reactivity. Thus, it can be concluded that the 4-coordinated copper structure in enargite is less stable. This aligns with the findings of Sasaki et al. [2], where the dissolved Cu content from enargite was much higher than that from tennantite in pH 5 and pH 11 solutions.

4. Conclusions

The crystal structures, electronic properties, and d-orbital splitting of the two most common copper-arsenic minerals (tennantite and enargite) were investigated. In tennantite, both S and Cu exhibit two different coordination environments, while As has a three-coordinated structure analogous to the ammonia molecule. In contrast, the coordination environments of the elements in enargite are simpler, with Cu, As, and S all being four-coordinated. Calculation results indicate that tennantite exhibits a stronger covalent character, leading to better hydrophobicity.

Hirshfeld charge calculations and density of states analysis reveal slight differences in the valence states of Cu in tennantite and enargite. Specifically, the former is a crystal with mixed +2 and +1 valence states, while the latter contains Cu in the +1 state. The valence state of As in tennantite (+3) is lower than that in enargite (+5). The energy levels of the five d-orbitals were calculated using the weight center method, which determined the energy level ordering of the different orbitals. Strong Cu-S p–d hybridization results in very small energy gaps among the five Cu 3d orbitals, leading to strong electron delocalization. Furthermore, the energy levels of the five d-orbitals of both 3- and 4-coordinated Cu in tennantite are similar and higher than those of the d-orbitals in enargite. However, the d-orbital splitting energy of four-coordinated Cu in enargite is smaller than that of four-coordinated Cu in tennantite, resulting in a less stable structure and higher reactivity of the four-coordinated Cu in enargite.

The collecting ability of the flotation collector to enargite would be weaker than tennantite due to the lower energies of the five d-orbitals. The arsenic in tennantite possesses lone pair electrons. Due to its lower valence state and stronger reducibility, it is predicted to lose electrons more easily and undergo oxidation, potentially leading to increased hydrophilicity, and hence tennantite would be easier to suppress than enargite.

Author Contributions

D.Y. did the conception, analysis, and initial interpretation of data, and did part of the writing work. Y.L. conceived of the study and prepared part of the figures and context. F.Q., M.J. and C.Q. helped in the mineral calculations and interpretation. W.Z., J.C. and Y.G. did supervision, review and editing of work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 52364023 and 52374264) the Special Fund for Science and Technology Development of Guangxi (Grant No. AD25069078) and Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2025GXNSFAA069648).

Data Availability Statement

All the research data have been included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dong Yang, Faqi Qu and Ciren Quni are employed by Xizang Jinlong Mining Co., Ltd., Meiguang Jiang and Wenjie Zhang are employed by Kunming Metallurgical Research Institute Co., Ltd. The paper reflects the views of the scientists and not the companies.

References

- Schwartz, D.M.; Omaynikova, V.Y.; Stocker, S.K. Environmental benefits of the CESL process for the treatment of high-arsenic copper concentrates. In Proceedings of the 9th International Seminar on Process Hydrometallury—International Conference on Metal Solvent Extraction, Santiago, Chile, 21–23 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, K.; Takatsugi, K.; Ishikura, K.; Hirajima, T. Spectroscopic study on oxidative dissolution of chalcopyrite, enargite and tennantite at different pH values. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 100, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioni, C.; George, L.L.; Cook, N.J.; Makovicky, E.; Moëlo, Y.; Pasero, M.; Sejkora, J.; Stanley, C.J.; Welch, M.D.; Bosi, F. The tetrahedrite group: Nomenclature and classification. Am. Mineral. 2020, 105, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.W.; Craig, J.R. Tetrahedrite-tennantite series compositional variations in the Cofer Deposit, Mineral District, Virginia. Am. Mineral. 1983, 68, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wuensch, B.J. The crystal structure of tetrahedrite, Cu12Sb4S13. Cryst. Mater. 1964, 119, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuensch, B.J.; Takéuchi, Y.; Nowacki, W. Refinement of the crystal structure of binnite, Cu12As4S13. Cryst. Mater. 1966, 123, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuensch, B.J. Sulfide Mineralogy; Mineralogical Society of America: Chantilly, VA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi, P.; Da Pelo, S.; Musu, E.; Atzei, D.; Elsener, B.; Fantauzzi, M.; Rossi, A. Enargite oxidation: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2008, 86, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi Reddy, S.; Gangi Reddy, N.C.; Siva Reddy, G.; Jagannadha Reddy, B.; Frost, R.L. Optical absorption and EPR studies on enargite. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 2006, 161, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Atzei, D.; Da Pelo, S.; Frau, F.; Lattanzi, P.; England, K.E.R.; Vaughan, D.J. Quantitative X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of enargite (Cu3AsS4) surface. Surf. Interface Anal. 2001, 31, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielczarski, J.A.; Cases, J.M.; Alnot, M.; Ehrhardt, J.J. XPS characterization of chalcopyrite, tetrahedrite, and tennantite surface products after different conditioning. 1. Aqueous solution at pH 10. Langmuir 1996, 12, 2519–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyantara, G.P.W.; Hirajima, T.; Miki, H.; Sasaki, K.; Kuroiwa, S.; Aoki, Y. Effect of H2O2 and potassium amyl xanthate on separation of enargite and tennantite from chalcopyrite and bornite using flotation. Miner. Eng. 2020, 152, 106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullston, D.; Fornasiero, D.; Ralston, J. Oxidation of synthetic and natural samples of enargite and tennantite: 2. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic study. Langmuir 1999, 15, 4530–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Grano, S.; Ralston, J.; Franco, A. Process development for the separation of tetrahedrite from chalcopyrite in the Neves-Corvo ore of Somincor SA, Portugal. Miner. Eng. 1995, 8, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasiero, D.; Fullston, D.; Li, C.; Ralston, J. Separation of enargite and tennantite from non-arsenic copper sulfide minerals by selective oxidation or dissolution. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2001, 61, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantar, C. Solution and flotation chemistry of enargite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2002, 210, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullston, D.; Fornasiero, D.; Ralston, J. Zeta potential study of the oxidation of copper sulfide minerals. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1999, 146, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L.; Neuman, E.W. The crystal structure of binnite, (Cu, Fe)12As4S13, and the chemical composition and structure of minerals of the tetrahedrite group. Cryst. Mater. 1934, 88, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao, J.; de Delgado, G.D.; Delgado, J.M.; Castrillo, F.; Odreman, O. Single-crystal structure refinement of enargite [Cu3AsS4]. Mater. Res. Bull. 1994, 29, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.S.; Marshall, W.G.; Zochowski, S.W. The low-temperature and high-pressure thermoelastic and structural properties of chalcopyrite, CuFeS2. Can. Mineral. 2011, 49, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, L.; Moelo, Y.; Leone, P.; Suchaud, M. Stoichiometric arsenopyrite, FeAsS, from La Roche-Balue Quarry, Loire-Atlantique, France: Crystal structure and Mössbauer study. Can. Mineral. 2012, 50, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.C.; Chen, J.H.; Zhao, C.; Cui, W. Comparison study of crystal and electronic structures for chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) and pyrite (FeS2). Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2021, 57, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.C.; Chen, J.H.; Zhao, C.H. Electronic and chemical structures of pyrite and arsenopyrite. Mineral. Mag. 2015, 79, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).