Abstract

Magmatic zircon trace element compositions and their variation trends provide valuable insights into the nature and evolutionary processes of magmatic rocks. The Himalayan orogen contains widespread leucogranites. Despite extensive studies on these granites, the features and petrogenetic implications of trace element composition of zircons from the leucogranites remain poorly constrained. In this study, we present a comprehensive dataset comprising new cathodoluminescence (CL) images, U-Pb ages, and trace element compositions of zircons from the Himalayan leucogranites, and compare them to the previously reported trace element data of zircon from I-type granites. Our results show that zircons from the Himalayan leucogranites have high Hf, U, Y, P, Th, Sc, and heavy rare earth element contents (HREE), and low Nb, Ta, Ti, and light rare earth element contents (LREE), and can be divided into two types. Type I (low-U) zircons exhibit well-developed oscillatory zoning, and the U concentrations are mostly <5000 ppm. Type II (high-U) zircons display mottled or spongy textures and possess elevated U contents that are mostly >5000 ppm. Zircons from the Himalayan leucogranites have higher contents of U, Hf, Nb, Ta, and elevated U/Yb ratios, but lower Th/U, Eu/Eu*, Ce/Ce*, LREE/HREE, and Ce/U values than those from I-type granitic zircons. Furthermore, zircons in the Himalayan leucogranites have gradually decreasing Th, Ti, Th/U, Eu/Eu*, and Ce/Ce*, and increasing U, Nb, Ta, and (Yb/Gd)N with increasing Hf. These geochemical features suggest the magmas involved in the genesis of leucogranites originated from the partial melting of metasedimentary sources under relatively reduced conditions, and underwent a high degree of magmatic fractionation.

1. Introduction

Zircon is the dominant reservoir for both Zr and Hf in Earth’s crust, and a ubiquitous accessory mineral in various igneous rocks. Moreover, zircon retains important geochemical information about the formation and evolution of its host magma [1,2]. Due to its stable physicochemical properties, low common lead contents and elemental diffusivities, and relatively high closure temperatures (>900 °C), zircon has the ability to retain its chemical composition through time and varying conditions [3,4]. Previous studies have suggested that zircon trace element chemistry can be used to monitor magma evolution [2,5], to infer parent-rock composition [6,7,8,9], to calculate the crystallization temperature of magma [10,11], to distinguish different tectono-magmatic settings [12,13,14], to explore the possibility of metallogeny [15,16,17], and to reveal the tectonic evolution of orogenic belt [18,19].

The early Cenozoic collision between the Indian and Asian plates generated the Himalaya range and the adjacent Tibetan Plateau [20]. The Cenozoic leucogranites are well developed along the ~2400 km Himalayan orogen, and have been considered as typical examples of the products of crustal anatexis without any mantle contribution [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The Himalayan leucogranites (HLs) are characterized by high SiO2 (mostly >70 wt.%) and low contents of mafic minerals (generally <5 vol%) [27,28]. Their formation is highly correlated with crustal reworking and differentiation during the collision between the Indian subcontinent and the Asian continent, providing an important record for long-term crustal evolution [29,30].

Over the last decades, numerous studies have been conducted on the HLs from the aspects of field relationship, accessory mineral U-Th-Pb geochronology, zircon Hf-O isotope, whole-rock major and trace element geochemistry, radiogenic Sr-Nd-Hf isotope, mineralogy, and experimental petrology. The significant achievements have been made in the spatial and temporal distributions, rock types, diagenetic ages, petrogenesis, and rare metal mineralization of these granites [22,23,24,25,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Traditionally, the Himalayan leucogranites were regarded as representing the composition of primary melts derived from partial melting of the crustal metasedimentary rocks [22,23,24]. However, there is some evidence to suggest that these leucogranites may originate from different sources and be differentiated by a variety of magmatic processes [27,32,40]. Consequently, the petrogenetic mechanism of Himalayan leucogranites remains controversial. Zircon incorporates a variety of trace elements that are highly sensitive to changes in melt composition [41,42]. As such, zircon is an ideal archive for deciphering the petrogenesis of these granites.

In this contribution, we present new zircon U-Pb geochronology and trace element data of leucogranites in the Yadong, Cona, and Namche Barwa areas in the eastern segment of the Himalayan orogen, and compile zircon trace element data from leucogranites in other regions of the Himalaya and I-type granites worldwide. We reveal the internal zoning profiles, trace element compositions, and petrogenetic characteristics of zircons from the HLs, and zircon trace element differences between the HLs and I-type granites. This study provides indicative significance for the magmatic evolution of the HLs and the discrimination of I- and S-type granites.

2. Geological Setting and Himalayan Leucogranite Overview

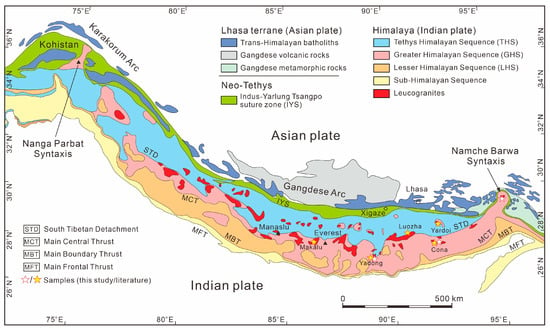

The Himalayan orogenic belt is composed of four tectonostratigraphic units. From north to south, they are the Tethyan Himalayan Sequence (THS), the Greater Himalayan Sequence (GHS), the Lesser Himalayan Sequence (LHS), and the Sub-Himalayan Sequence (Figure 1) [20]. These units are structurally separated by the Southern Tibetan Detachment System (STDS), the Main Central Thrust (MCT), and the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT) (Figure 1). The north side of the Himalayan orogen and the Lhasa block is separated by the Indus-Yarlung Tsangpo suture zone (IYS), which represents remnants of the Neo-Tethyan Ocean situated between the Indian and Lhasa blocks (Figure 1) [20]. The south side of the Himalayan orogen and the Indian craton is separated by the Main Frontal Thrust (MFT) (Figure 1). The THS consists mainly of Neoproterozoic to Mesozoic sedimentary strata and underwent low-grade greenschist to epidote-amphibolite facies metamorphism [20,43]. The GHS, representing the core of the Himalayan orogen, is composed of migmatitic orthogneiss, paragneiss, schist, mafic granulite, amphibolite, marble, and calc-silicate rock, and underwent granulite-to-eclogite facies metamorphism and partial melting [20,43]. The LHS is mainly composed of Paleoproterozoic to Mesoproterozoic metasedimentary, sedimentary, volcanic, and pluton rocks that were subjected to low-grade metamorphism [20,44].

Figure 1.

Sketch geological map of the Himalayan orogen (modified after Zhang et al. [43]), showing the distribution of Cenozoic leucogranites, and locations of the studied samples.

Within the Himalayan orogenic belt, two leucogranite belts, namely the Tethys Himalayan belt in the north and the Greater Himalayan belt in the south, occur along the entire length of the orogen (Figure 1). The leucogranites in the THS typically occur as cores within gneissic domes or intrude into the surrounding sedimentary and metamorphic rocks as stocks and dikes (Figure 1) [27,36]. Within the GHS, leucogranites mostly occur as a discontinuous chain of sills and dikes beneath the STDS (Figure 1) [27,36]. In addition, there are many late Miocene-Pliocene-Pleistocene leucogranites distributed in the Eastern and Western Himalayan Syntaxis [26,45,46].

The HLs are predominantly composed of leucocratic minerals, such as quartz, K-feldspar, plagioclase, and muscovite, and contain minor biotite, tourmaline, or garnet, with accessory phase zircon, monazite, apatite, ilmenite, and xenotime [27,28,33]. These leucogranites can be divided into the following types due to their different mineral assemblages: two-mica (biotite and muscovite) granites, muscovite granites, tourmaline-bearing granites, garnet-bearing granites, and two-mica granites form the major lithology in both the Tethys and the Greater Himalayan belt [27,28,33]. The distinct mineral assemblage of the leucogranites may have resulted from the heterogeneity of source regions, different melting mechanisms, and the degree of magma fractionation [24,27,29,31,32,34,35,38,47,48,49,50].

U-Th-Pb dating of zircon, monazite, and xenotime is often used to date the emplacement age of Himalayan granitic bodies. Based on the dating results of these accessory minerals, Wu et al. (2020) [27] divided the formation time of the HLs into three distinct stages: Eo-Himalayan (46–25 Ma), Neo-Himalayan (25–14 Ma), and Post-Himalayan (<14 Ma); and they argued that most leucogranites in both belts were emplaced during the Neo-Himalayan stage and the older leucogranites (>25 Ma) only occur in the THS belt. Recently, Cao et al. (2022) [28] compiled a more comprehensive dataset and proposed that the HLs could be divided into five stages: early Eocene (49–40 Ma), late Eocene-early Oligocene (39–29 Ma), late Oligocene-middle Miocene (28–15 Ma), late Miocene (14–7 Ma) and late Miocene-Pliocene-Pleistocene (6–0.7 Ma), corresponding to the Neo-Tethyan oceanic plate break-off, low-angle underthrust of Indian lithosphere, Indian lithosphere lateral slab break-off or rollback, Indian lithosphere slab vertically tearing, and flat underthrust of Indian lithosphere, respectively. These studies suggested that the HLs recorded long-term and/or multistage partial melting and magmatic crystallization, which is consistent with the long-lived metamorphic and anatectic processes of GHS high-grade metamorphic rocks [43,51,52,53].

The HLs generally have high SiO2, Al2O3, K2O, and Na2O contents, low CaO, MgO, FeO, TiO2, and MnO contents, and a high aluminum saturation index (ASI, molar ratio of Al2O3/CaO + NaO2 + K2O, mostly exceeding 1.1) [27,28,30,37]. These compositional characteristics are consistent with the dominance of quartz and feldspar and the scarcity of dark-colored minerals, and the frequent occurrence of aluminum-rich minerals such as muscovite, garnet, and tourmaline [27,28,36]. In general, the HLs have highly variable trace element and isotopic compositions, characterized by enriched in Rb, K, U, Ta, Cs, Pb, Li, Be, Sn, Ga and light rare earth elements (LREE), and depleted in Sr, Ba, Zr, Hf, Y, Ho, Th, Sc, V, Cr, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ti and heavy rare earth elements (HREE), and typically display high whole-rock (87Sr/86Sr)i ratios (mostly >0.7) and zircon δ18O values (mostly >7), and low whole-rock εNd(t) (mostly <−10) and zircon εHf(t) values (mostly <−5), with negative Eu anomalies in chondrite-normalized REE patterns [25,27,28]. Moreover, some leucogranites exhibit obvious enrichment of light Si and heavy Mg isotopes [30]. The significant variations in trace element ratios of Zr/Hf, Nb/Ta, Rb/Sr, K/Rb, Y/Ho, along with substantial fractionations of non-traditional stable isotopes (e.g., Mg, Zn, and K), indicate that the involvement of multiple factors in the formation of the HLs [27,28,30].

3. Sample and Methodology

3.1. Sample Description

The 21 leucogranite samples studied were collected from the Himalaya in the Yadong, Cuona, and Namche Barwa areas (Figure 1). These leucogranites include garnet-bearing granite, tourmaline-bearing granite, and biotite granite (Figure S1). Petrographic observations show that the garnet-bearing leucogranites typically consist of quartz, plagioclase, K-feldspar, and garnet (Figure S1a,b). Tourmaline-bearing leucogranites consist of plagioclase, K-feldspar, quartz, and tourmaline (Figure S1c,d). Biotite leucogranites consist of quartz, plagioclase, K-feldspar, and biotite (Figure S1e,f). Plagioclase, garnet, and tourmaline occur commonly in euhedral to subhedral form, and anhedral quartz, biotite, and K-feldspar occur among other minerals (Figure S1). Accessory minerals zircon, apatite, monazite, and ilmenite are common in these leucogranites.

3.2. Analytical Methods

Zircon grains were separated using conventional density separation techniques and final purification by handpicking. They were mounted in epoxy resin beds and half-sectioned after the resin beds had dried. Prior to analytical work, all zircon grains were examined under a microscope using both transmitted and reflected light. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of zircons were acquired using a scanning electron microscope (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (CAGS), Beijing. CL images were used for checking the internal texture of individual zircon grains and selecting suitable positions for in situ U-Pb dating and zircon trace element analysis. The experimental conditions for zircon CL images were as follows: accelerating voltage 15 kV, beam current ~60 μA, and working distance 15 mm.

In situ U-Pb dating and trace element analysis of zircons were simultaneously conducted by LA-ICP-MS at the Wuhan Sample Solution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China. Detailed operating conditions for the laser ablation system and the ICP-MS instrument were the same as described by Zong et al. [54]. Laser sampling was performed using a GeoLas Pro laser ablation system (Coherent, Göttingen, Germany), comprising a COMPexPro 102 ArF excimer laser and a MicroLas optical unit. An Agilent 7900 (Agilent, Hachioji, Japan) ICP-MS instrument was used to acquire ion-signal intensities. A beam size of 24 μm was used for all the samples in this study. A total of 395 zircon grains were analyzed for U-Pb isotopes and trace element compositions (Th, U, P, Sc, Ti, Hf, Y, Nb, Ta, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu). Zircon standards GJ-1 and Plešovice were used as secondary reference materials during LA-ICP-MS analysis. NIST610 and Si were used to calibrate the trace element concentrations as external reference material and internal standard element, respectively. Offline selection and integration of background and analyzed signals, time-drift correction, and quantitative calibration for trace element analysis and U-Pb dating were carried out using ICPMSDataCal 12.0 [55].

3.3. Dat Compilation and Filtering

We compiled ~400 zircon trace element compositions of HLs from the published literature and ~950 zircon trace element compositions of I-type granites from different regions around the world. To ensure data quality and comparability, we implemented the following screening and harmonization procedures: (1) we prioritized compiling data that was consistent with the analytical method used for zircon analysis in this study (LA-ICP-MS) to minimize inter-laboratory biases associated with different analytical techniques. (2) The compilation results included key trace elements (e.g., REEs, Hf, U, Th, Y, Nb, Ta, Ti, and P), and zircons were omitted if the source indicated that they were inherited. (3) The light rare element index (LREE-I = Dy/Nd + Dy/Sm < 30) was used to eliminate potential zircon alteration [56]. (4) The Ti > 20 ppm was used to exclude Ti-rich mineral inclusions in zircons from HLs [57]. The criterion for compiled HLs was mainly based on the original authors’ designations and mineralogical criteria (presence of muscovite ± garnet ± tourmaline ± cordierite). The classification of ~950 zircon analyses as I-type granites was based on the following criteria: (1) the host granites were explicitly classified as I-type in the original publications; (2) the whole-rock composition of the host granites was metaluminous to weakly peraluminous; (3) the host granites contained hornblende and/or biotite. The compiled zircon dataset of HLs and I-type granites is listed in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

In addition, we added 395 zircon U-Pb ages and trace element compositions of HLs from our own analyses. The full dataset is listed in the Supplementary Table S3. Europium and Cerium anomalies were calculated using the following equations: Eu/Eu* = EuN/(SmN × GdN)1/2 and Ce/Ce* = CeN/(LaN × PrN)1/2, where the subscript N denotes values normalized to the chondrite. The chondrite values are from Sun and McDonough [58]. Magma crystallization temperatures were estimated utilizing the Ti-in-zircon thermometer [11], where it was assumed that αSiO2 = 1.0 because of the common existence of quartz in the studied samples and HLs, and αTiO2 = 0.5 due to the common presence of ilmenite (a common accessory phase in HLs) and the peraluminous nature of Himalayan magmas.

4. Results

4.1. Zircon Morphology and Internal Structures

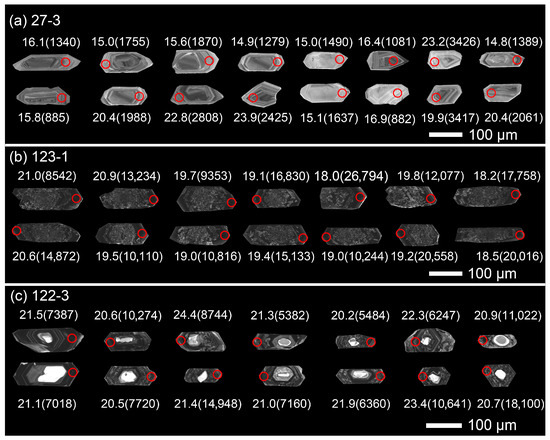

Based on uranium content, zircons from the studied leucogranites are predominantly categorized into two types: “low-U” (type I) and “high-U” (type II). The type I zircons are characterized by relatively low U content (mostly <5000 ppm), and have not undergone metamictization, and therefore display obvious oscillatory zoning patterns (Figure 2a); these zircons are euhedral, with long to short prismatic shapes, and mostly 100–250 μm in length with length/width ratios of ~1:1 to 5:1 (Figure 2a). The type II zircons have relatively high U content (mostly >5000 ppm), and have undergone extensive metamictization, and therefore exhibit a sponge-like texture (Figure 2b,c); these zircons show euhedral, long and/or short prismatic forms, and have lengths of 100–300 μm with length/width ratios of ~1.5:1 to 5:1 (Figure 2b,c). Some type II zircons without core-rim structures typically show dark luminescence in the CL images (Figure 2b). Some type II zircons exhibit a distinct core-rim structure (Figure 2c). The inherited cores are characterized by bright luminescence, variable shapes, sizes, and zoning patterns in the CL images; the rims show dark luminescence and oscillatory zoning (Figure 2c). Apart from the U content, there is no significant difference in the composition of other trace elements between type I and type II zircons (Figures S2 and S3). Furthermore, on the diagrams of Hf versus Ti, TTiZ, Th/U, (Yb/Gd)N, Nb, and Ta of zircons, type I and type II zircons show similar trends of variation (Figure S4). In this case, the metamictization does not change the composition and related evolutionary trends of other zircon elements except for the U. Therefore, we will not make a distinction in the following discussion.

Figure 2.

Cathodoluminescence images of representative zircon grains from the studied Himalayan leucogranites, showing the analyzed spot locations and relevant 206Pb/238U ages (in Ma, number outside parentheses) and U contents (in ppm, number inside parentheses). (a) Garnet-bearing granite, (b) Tourmaline-bearing granite), and (c) Biotite granite.

4.2. Zircon U-Pb Ages and Trace Element Compositions

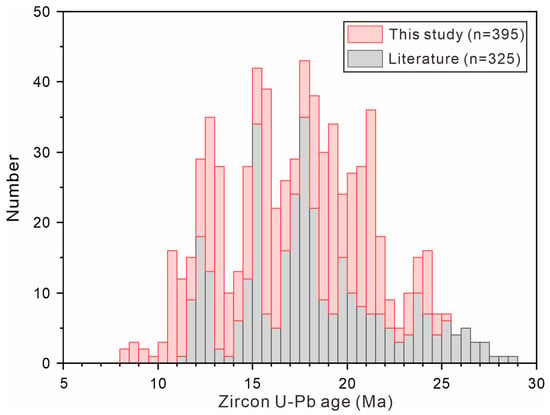

The results of U-Pb dating of zircon from 21 leucogranite samples in the Yadong, Cuona, and Namche Barwa areas of the Himalaya are listed in Table S3. Zircon analyses from the HLs yielded 206Pb/238U ages ranging from 25.0 to 8.2 Ma (Figure 3; Table S3). A wide age range spanning ~29 Ma to ~8 Ma is obtained when these new data are combined with compiled U-Pb ages of zircons from the leucogranites in other regions of the Himalaya (Figure 3; Tables S1 and S3). Moreover, the zircon age spectra from these leucogranites exhibit multiple peaks at ~24 Ma, ~21 Ma, ~18 Ma, ~15 Ma, and ~12 Ma (Figure 3), indicating multiple episodes of magmatism during the Oligocene and Miocene.

Figure 3.

U-Pb age histogram of zircons from the Himalayan leucogranites. Data and sources are given in Tables S1 and S3. The literature data include only precise U-Pb ages; the approximate ages (e.g., “ca”) were excluded.

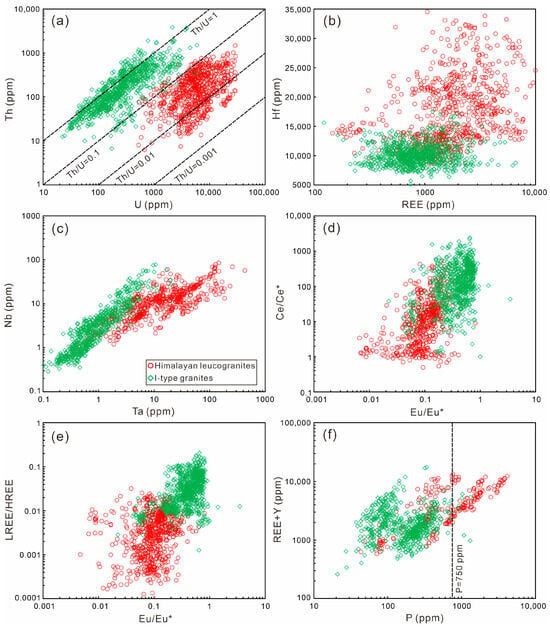

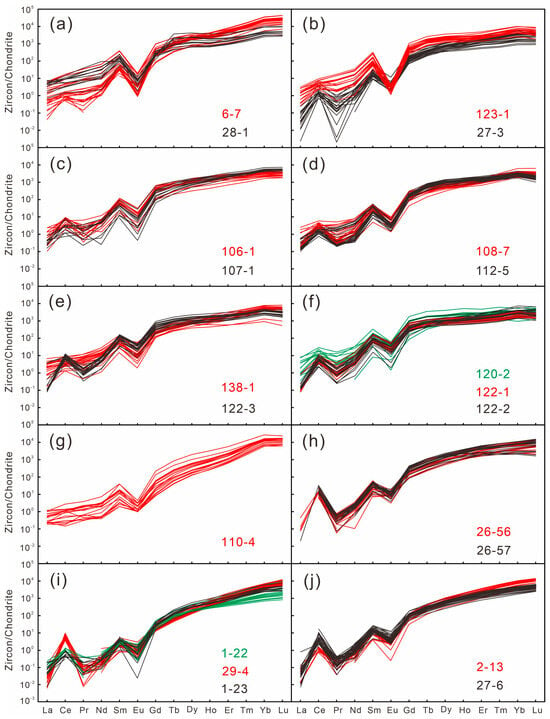

Zircons from the studied and compiled leucogranites exhibit similar trace element compositions, with Hf ranging from 8398 to 34,553 ppm, U from 528 to 29,557 ppm, Y from 371 to 13,600 ppm, P from 43 to 4160 ppm, Th from 6 to 1480 ppm, Sc from 247 to 1824 ppm, Nb from 1.0 to 85 ppm, Ta from 0.4 to 430 ppm, and Ti from 0.3 to 19 ppm (Figure 4; Tables S1 and S3). The calculated Th/U, Eu/Eu*, and Ce/Ce* ratios of zircons range from 0.002 to 0.19, from 0.005 to 0.81, and from 0.5 to 518, respectively (Figure 4a,d). The contents of LREE (La–Nd), HREE (Er–Lu), and REE (La–Lu) in these zircons are 0.2–58 ppm, 71–8881 ppm, and 147–9977 ppm, respectively, and the ratio of LREE/HREE varies from 0.0001 to 0.032 (Figure 4b,e). Consequently, zircons from the leucogranites show high Hf, U, Y, P, Th, Sc, and HREE contents, but low Nb, Ta, Ti, and LREE contents. In the chondrite-normalized REE patterns, the studied zircons are strongly enriched in HREE relative to LREE, with positive Ce and negative Eu anomalies (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

(a) Th versus U, (b) Hf versus REE, (c) Nb versus Ta, (d) Ce/Ce* versus Eu/Eu*, (e) LREE/HREE versus Eu/Eu*, and (f) REE+Y versus P diagrams of zircons from Himalayan leucogranites and I-type granites. Data sources are listed in Tables S1–S3. REE-rare earth elements; LREE-light rare earth elements; HREE-heavy rare earth elements.

Figure 5.

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of zircons from the studied leucogranites. Chondrite values are from Sun and McDonough [58].

5. Discussion

5.1. Origin of Himalayan Leucogranites

5.1.1. Magma Source and Tectonic Setting

The HLs are widely regarded as representing the pure crustal melts derived from the partial melting of metasedimentary rocks [22,24,25,37,59,60,61]. The metapelites within the GHS are particularly considered the dominant source lithology, as supported by geochemical and experimental evidence [22,24,59,60]. However, in recent years, in addition to felsic granites, minor coeval intermediate-mafic lamprophyres, gabbros, diorites, and adakitic rocks have been identified in the Himalayan orogen [62,63,64,65]. Therefore, the petrogenetic model for the HLs originating from partial melting of pure crustal sedimentary rocks has been questioned by many scholars [27,50].

Zircon, a highly refractory accessory mineral commonly found in granitic rocks, has been widely utilized to investigate the compositional characteristics of host magmas [2,6,41,42]. Zircons from the HLs systematically exhibit higher U, Hf, Nb, and Ta concentrations than those from the I-type granites (Figure 4a–c). It is generally believed that the metasedimentary rocks are characteristically enriched in incompatible elements such as U but depleted in Nb, Ta, and Sr [66]. In this case, the relatively higher contents of U, Nb, and Ta in zircons from the HLs are likely attributable to their metasedimentary source. The incompatible elements (e.g., Hf, Nb, Ta) are typically excluded from early-crystallizing minerals such as feldspar, biotite, and quartz, and can become progressively enriched in the residual melt during the cooling of magma [67]. The Hf contents of zircons from the studied HLs vary from 8398 ppm to 34,553 ppm (Figure 4b). Accordingly, these uniformly high Hf contents (all >8000 ppm and mostly >15,000 ppm) reflect extensive magma fractionation.

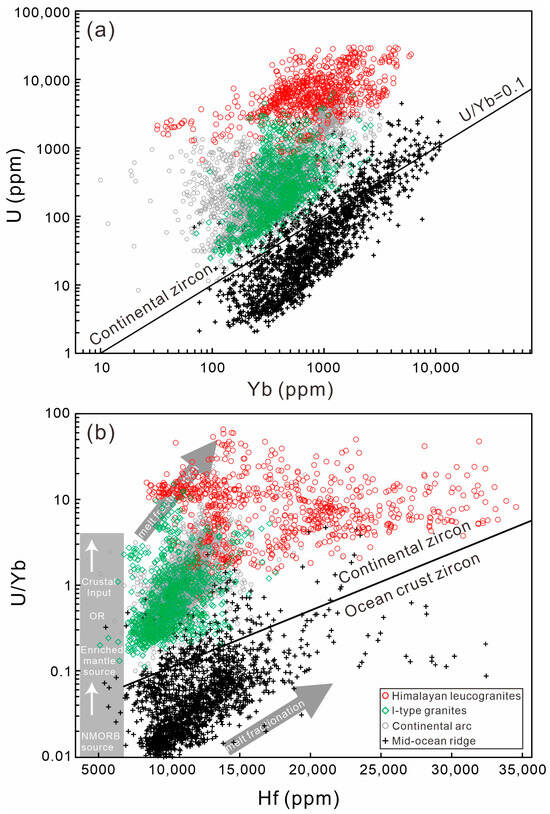

Previous studies have demonstrated that trace element compositions of oceanic-affinity zircon are distinct from those of continental-affinity zircon [12,13]. Zircons from continental arc exhibit Yb contents comparable to those of oceanic zircons, but are characterized by notably higher U contents, resulting in distinctly elevated U/Yb ratios (0.1–4), in contrast to oceanic crust zircons, which typically display U/Yb ratios below 0.1 (Figure 6) [12]. In both U versus Yb and U/Yb versus Hf diagrams, all of the zircon data from the studied leucogranites plot within the continental zircon field (Figure 6a,b), indicating a continental crustal origin for their parental magmas rather than an oceanic one. Zircons from the compiled I-type granites show U, Yb, and Hf contents and U/Yb ratios similar to those typical of continental-arc magmatic zircons (Figure 6a,b). Notably, most zircons from the HLs display higher U contents and U/Yb ratios compared to both I-type granitic zircons and continental-arc zircons (Figure 6a,b), suggesting derivation from a more enriched crustal magma source. Thus, we infer that the majority of the HLs are S-type granites derived from metasedimentary protoliths, with a few being I-type granites.

Figure 6.

(a) U versus Yb and (b) U/Yb versus Hf diagrams for continental and ocean crust zircons. The zircon data and sources of Himalayan leucogranites and I-type granites are given in Tables S1–S3, and zircons in continental arc and mid-ocean ridge are from Grimes et al. [13].

5.1.2. Oxygen Fugacity and Temperature of Magma

The zircon Eu anomaly is influenced by both the abundance of coexisting plagioclase and the oxidation state of the magma [67,68]. Divalent Eu (Eu2+) behaves geochemically similarly to Sr2+, and both cations can readily substitute for Ca2+ in plagioclase [67]. Hence, the pronounced negative Eu anomalies in zircons may reflect either extensive plagioclase removal from an evolving melt or low magmatic oxygen fugacity, which stabilizes europium in the divalent state and enhances its partitioning into plagioclase [15,68]. This study reveals that zircon grains from the HLs exhibit more pronounced negative Eu anomalies (with most Eu/Eu* ratios < 0.2) than those from I-type granites (Figure 4d,e). Thus, the low Eu/Eu* values observed in Himalayan zircons probably suggest that their parent magmas underwent significant plagioclase fractionation and/or formed under relatively reducing environments.

Zircon Ce anomaly is primarily governed by oxygen fugacity, crystallization temperature, and magmatic water content [68,69]. However, the crystallization temperature calculated from the Ti-in-zircon thermometer shows no significant difference between I- and S-type magma [8]. Similarly, magmatic water contents do not vary substantially between the two granite types [70]. Therefore, variations in zircon Ce anomalies can be largely attributed to differences in magmatic oxygen fugacity. Under high oxygen fugacity conditions, trivalent Ce is readily oxidized to tetravalent Ce4+, which readily substitutes for Zr4+ in the zircon lattice due to their similar ionic radii and identical charge [71]. In this study, zircon grains from the HLs exhibit lower Ce/Ce* values (i.e., weaker positive Ce anomalies) than those from I-type granites (Figure 4d), suggesting that the Himalayan leucogranitic magmas likely formed under relatively low oxygen fugacity environments. However, some researchers argued that partial melting of HLs occurred in relatively oxidized conditions [24].

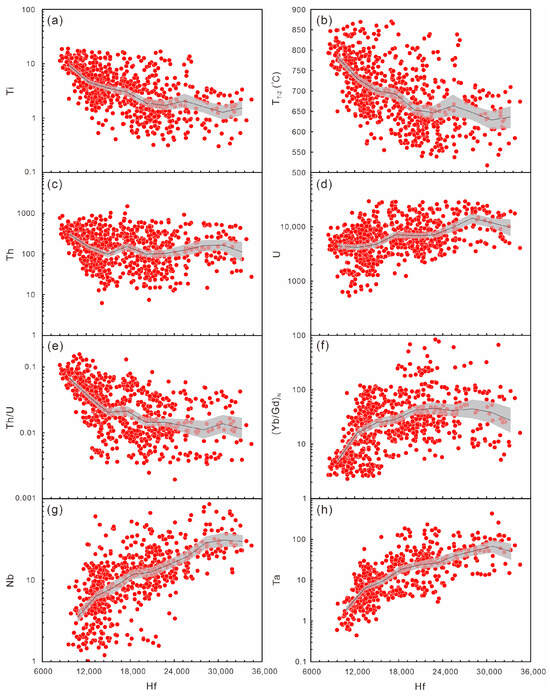

Zircon Ti content is primarily temperature-dependent and can consequently be used to constrain magmatic crystallization temperatures [10,11]. The Ti contents in zircons from the HLs range from 0.3 ppm to 19 ppm (Figure 7a). Although the calculated Ti-in-zircon temperatures can reach up to 850 °C, most of them are concentrated at 600–800 °C with a mean of 696 °C (Figure 7b). These results are broadly consistent with whole-rock zircon saturation temperatures reported for the Himalayan leucogranites [27,28]. Therefore, the HLs are widely considered as low-temperature “cold” granites, although previous work argued that they may have formed under high-temperature conditions [72].

Figure 7.

(a) Hf versus Ti, (b) Hf versus TTiZ, (c) Hf versus Th, (d) Hf versus U, (e) Hf versus Th/U, (f) Hf versus (Yb/Gd)N, (g) Hf versus Nb, and (h) Hf versus Ta diagrams of zircons from Himalayan leucogranites. In this study, Hf concentration is used to define the degree of magmatic differentiation and to reflect the changes in some trace elements and their ratios. Data are plotted as scatter points along with binned bootstrap trends. For each plot, the data were divided into 10 equal-width bins along the X-axis, and 2000 bootstrap resamples were performed within each bin to estimate the median trend (solid line) and its 95% confidence interval (shaded region).

5.1.3. Fractional Crystallization

Trace element concentrations and ratios in magmatic zircons often show regular variations with magma evolution [41,42,73]. For instance, Hf content in zircon typically increases during progressive fractional crystallization of granitic magmas and is therefore widely used as a proxy for the degree of evolution [2]. The Ti contents and corresponding Ti-in-zircon temperatures (TTiZ) are inversely correlated with Hf (Figure 7a,b). In this case, Hf increases, and Ti and TTiZ decrease systematically, indicating progressive magma cooling during zircon crystallization.

Increasing Hf content in zircon from the HLs is accompanied by a slight decrease in Th and an increase in U, resulting in a gradual decline in the Th/U ratio (Figure 7c–e). This change trend can be explained by the crystallization of monazite, which efficiently removes Th from the melt, while U becomes enriched in later residual melt. Such zircon behavior is consistent with systematic whole-rock variations in Th and U contents and Th/U ratios during magma evolution [28]. Additionally, the positive correlation of zircon (Yb/Gd)N ratios with Hf contents (Figure 7f) indicates progressive depletion of MREE relative to HREE in the leucogranitic magma. This probably resulted from the co-crystallization of MREE-rich phases such as apatite and monazite during zircon growth.

Nb and Ta are key rare metal ore-forming elements. Nb and Ta contents of the leucogranite zircons increase with increasing Hf, reaching maximum values near or above 100 ppm (Figure 7g,h). This indicates that the magmas that underwent extensive fractional crystallization have greater potential for Nb-Ta mineralization. In recent years, numerous rare metal deposits associated with highly fractionated leucogranites were identified across the Himalayan orogen, such as Nb-Ta-Be mineralization in the Xiaru dome [74], Li-Be-Nb-Ta mineralization in the Kuju area [75], W-Sn-Be mineralization in the Cuonadong dome [76], and Li mineralization in the Qomolangma area [39]. The widespread mineralization of the Himalayan leucogranites highlights the orogenic belt as a promising world-class rare metal metallogenic province.

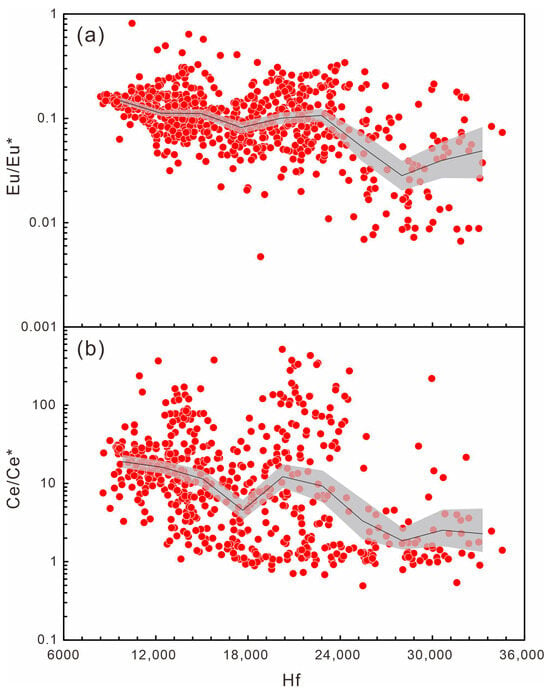

Eu/Eu* and Ce/Ce* values of the leucogranite zircons gradually decrease with increasing Hf, although localized increases are observed (Figure 8a,b), which may be influenced by fluctuations in oxygen fugacity or changes in melt structure. These observations likely indicate that the Himalayan leucogranitic magma formed under relatively reducing conditions and became progressively more reduced with magmatic fractionation.

Figure 8.

(a) Hf versus Eu/Eu* and (b) Hf versus Ce/Ce* diagrams of zircons from Himalayan leucogranites. Data are plotted as scatter points along with binned bootstrap trends. For each plot, the data were divided into 10 equal-width bins along the X-axis, and 2000 bootstrap resamples were performed within each bin to estimate the median trend (solid line) and its 95% confidence interval (shaded region).

5.2. Discrimination of S- and I-Type Granites

Distinguishing the sources of granite is crucial for understanding the formation and evolution of continental crust [9]. The S- and I-type granite classification scheme, initially defined based on the study of granites from the Lachlan Fold Belt of southeastern Australia, is widely used to distinguish melts that were derived from the metasedimentary rocks and metaigneous rocks [77]. Mineralogically, I-type granites are characterized by the prevalence of hornblende and biotite as essential mafic phases, while S-type granites typically contain aluminous minerals, such as primary muscovite, cordierite, garnet, and tourmaline [36,70,77]. Geochemically, S-type granites are strongly peraluminous (ASI > 1.1), with high Rb/Sr ratios and low Sr contents, and have low whole-rock εNd(t) and zircon εHf(t), high whole-rock initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios and zircon δ18O values [28,70,78]. I-type granites are characterized by their metaluminous to weakly peraluminous composition (ASI < 1.1), with relatively high εNd(t) values and low initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios, consistent with derivation from mantle-like or juvenile igneous protoliths [70,77].

Several schemes have been proposed for the discrimination of S- and I-type granites based on zircon trace element features. Wang et al. [7] indicated that zircons from the S-type granitoids in the central Lhasa terrane and Tethyan Himalaya are characterized by higher Pb contents, lower (Nb/Pb)N ratios, and more significant Eu negative anomalies, while the I-type granites in the southern and central Lhasa terrane exhibit lower Pb contents and (Nb/Pb)N ratios. The author attributed these zircon trace element compositional differences to distinct magma source regions. In addition, the P content and the ratio of P to REE + Y in zircon have been used to distinguish between S- and I-type granites [8,79]. Zircons in S-type granites from the Lachlan Fold Belt and Bohemian Massif typically have higher P contents (mostly >750 ppm) and show a strong 1:1 correlation between the molar concentrations of P and REE + Y, whereas zircons from I-type usually contain less than 750 ppm P and show no linear relationship between P and REE + Y [8,79]. Apatite has greater solubility in peraluminous S-type melt compared to peralkaline and/or metaluminous I-type melt [80]. Therefore, these researchers explain the difference in P content of zircon as the apatite effect, whereby the higher availability of P in S-type melts generally results in increased P incorporation into zircon via the xenotime substitution mechanism P5+ + (Y + REE)3+ = Zr4+ + Si4+.

However, recent studies have demonstrated that the zircons in many S-type and/or strongly peraluminous granites have significantly low P concentration (<750 ppm), and exhibit correlations between P and REE + Y that deviate from a strict 1:1 [9,81]. The P content of zircons in the studied HLs is not always higher than 750 ppm, and a significant proportion of zircons exhibit P contents below this threshold (Figure 4f). Therefore, this study further shows that the zircon P content and its correlation with REE + Y are unreliable as robust discriminators between I- and S-type granites.

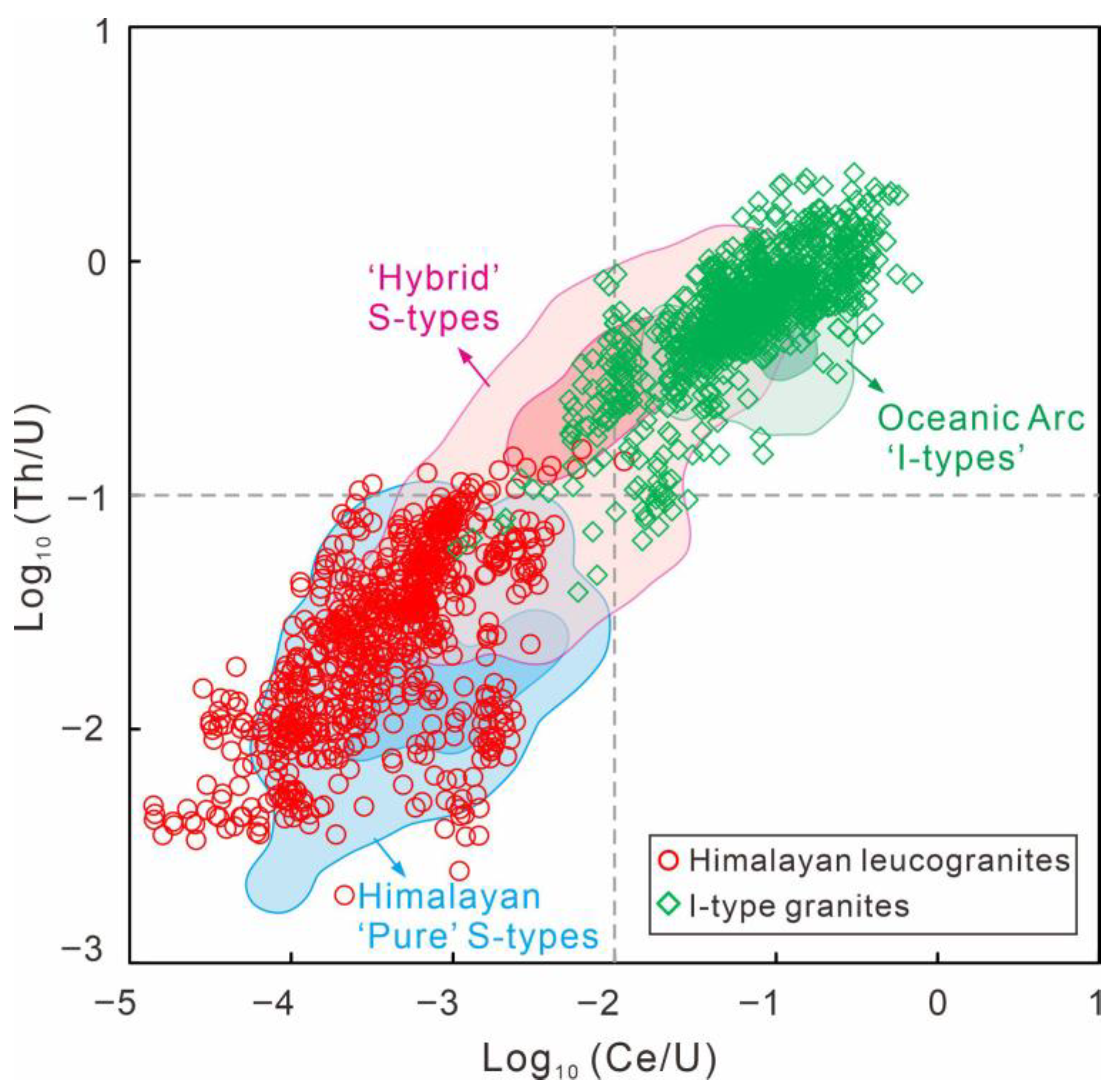

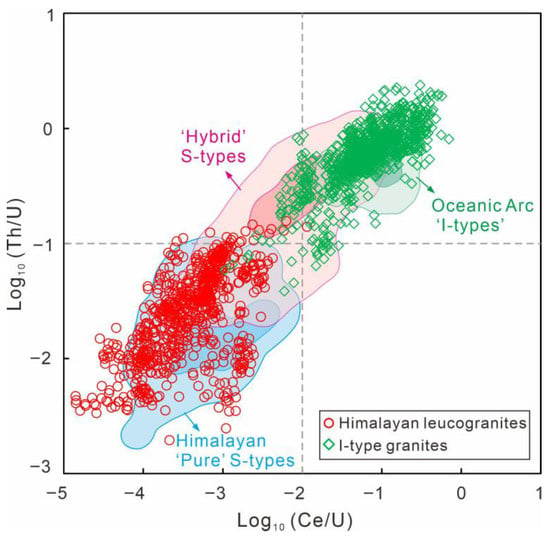

To re-evaluate discrimination between I- and S-type granites using zircon trace element compositions, Roberts et al. [9] recently compiled a comprehensive dataset of trace element data of zircon from diverse magmatic suites and metapelites, and proposed a new discrimination method based on a log10 (Ce/U) vs. log10 (Th/U) diagram based on Th and Ce depletions characteristic of anatectic melts formed under monazite-saturated conditions (Figure 9). In this diagram, the Himalayan ‘pure’ S-type zircons overlap the metapelite-derived field, with both falling within the bottom left quadrant. The ‘oceanic arc’ I-type zircons overlap the presumably sediment-free ‘mantle-derived’ field, with both occupying the top right quadrant (Figure 9). Zircons from other S-types (i.e., hybrid granites) are located between the zircons in the Himalayan ‘pure’ S-types and the ‘oceanic arc’ I-types (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Th/U versus Ce/U diagram of zircons for I- and S-type granite classification (Roberts et al. [9]).

On the log10 (Ce/U) vs. log10 (Th/U) discrimination diagram, most zircons from the studied HLs plot within the Himalayan ‘pure’ S-type field, with a small portion falling into the ‘hybrid’ S-type field (Figure 9). This scattered distribution may be attributed to analytical uncertainties, metamictization, and/or magmatic compositional heterogeneity. We evaluated the analytical errors for data points located outside the Himalayan ‘pure’ S-type field and found that, even accounting for analysis uncertainty, the majority of these points still cannot fall into the Himalayan ‘pure’ S-type field. Thus, analytical errors are unlikely to be the primary cause of the observed dispersion. Both non-metamict (low-U) and metamict (high-U) zircons have a portion falling into the ‘hybrid’ S-type field (Figure S3), indicating that metamictization is not the main cause of this dispersion. Therefore, this dispersed feature may reflect the heterogeneity of the magma source, implying that some Himalayan leucogranite magmas may not have derived from pure metapelitic source areas, but could have incorporated a certain proportion of igneous components or experienced a high degree of crustal differentiation [26]. This interpretation is consistent with previous geochemical studies proposing source heterogeneity for Himalayan leucogranites. Nevertheless, we maintain that the Ce/U and Th/U ratios remain effective discriminants for distinguishing between pure S-type and I-type granites.

This study shows that there are systematic differences in the trace element compositions between zircons from Himalayan S-type leucogranites and I-type granites. Zircons from the Himalayan S-type granites are characterized by relatively higher U, Hf, Nb, Ta contents and U/Yb ratios, and lower Eu/Eu*, Ce/Ce*, LREE/HREE, Th/U, and Ce/U ratios in comparison to those from I-type granites (Figure 4, Figure 6 and Figure 9). As discussed previously, the higher U, Hf, Nb, Ta, U/Yb, along with lower Eu/Eu* and Ce/Ce* values in Himalayan S-type zircons are associated with extensive magmatic differentiation and/or a sedimentary protolith. Monazite is a major host mineral for LREE and Th, and is ubiquitous in metasedimentary rocks [82]. The partitioning coefficients of LREE and Th between monazite and melt can reach up to 1000 [83]. The persistence of residual monazite during partial melting of metasedimentary protoliths may result in relatively depleted LREE contents in S-type melt. Consequently, we suggest that monazite plays a critical role in modulating the LREE/HREE ratios of Himalayan S-type zircons.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Two distinct types of zircons are recognized in Himalayan leucogranites: Type I (low-U) zircons exhibit well-defined oscillatory zoning and have U concentrations mostly below 5000 ppm; Type II (high-U) zircons are characterized by spongy textures and U concentrations mostly exceeding 5000 ppm.

- (2)

- Himalayan leucogranites may have formed in a relatively reduced environment and underwent a high degree of magmatic fractionation.

- (3)

- Zircons from Himalayan leucogranites exhibit higher U, Hf, Nb, Ta contents and U/Yb ratios, but lower Eu/Eu*, Ce/Ce*, LREE/HREE, Th/U, and Ce/U ratios than those from I-type granites.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min15121306/s1. Supplementary Figure S1: Representative photomicrographs of the studied Himalayan leucogranites. Supplementary Figure S2: Trace element compositions of the two different types of zircons from the Himalayan leucogranites. Supplementary Figure S3: Th/U versus Ce/U diagram of zircons for I- and S-type granite classification. Supplementary Figure S4: The relationship between Hf and Ti, TTiZ, Th/U, (Yb/Gd) N, Nb, and Ta in two different types of zircons from the Himalayan leucogranites. Supplementary Figure S5: U-Pb concordia diagrams of zircons from the studied Himalayan leucogranites. Supplementary Table S1: Compiled U-Pb ages and trace element compositions (in ppm) of zircons from Himalayan leucogranites. Supplementary Table S2: Compiled trace element compositions (in ppm) of zircons from I-type granites. Supplementary Table S3: Zircon U-Pb dating and trace elements data of the studied Himalayan leucogranites.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: W.L. and Z.Z.; methodology: W.L., J.Y., Y.Z., Q.L., Y.A. and D.Z.; investigation: W.L. and Z.Z.; data curation: W.L. and Z.Z.; formal analysis: W.L.; writing—original draft preparation: W.L.; writing—review and editing: W.L. and Z.Z.; supervision: Z.Z., J.Y., Y.A. and Y.Z.; funding acquisition: Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U2244203 and 91855210) and the China Geological Survey (Grant No. DD20221630).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by Wuhan Sample Solution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd., for conducting zircon U-Pb dating and trace element analysis. We are grateful to editors and reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments on the manuscript. Their thorough review and insightful feedback have greatly contributed to the improvement of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bea, F.; Montero, P. Behavior of accessory phases and redistribution of Zr, REE, Y, Th, and U during metamorphism and partial melting of metapelites in the lower crust: An example from the Kinzigite Formation of Ivrea-Verbano, NW Italy. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claiborne, L.L.; Miller, C.F.; Walker, B.A.; Wooden, J.L.; Mazdab, F.K.; Bea, F. Tracking magmatic processes through Zr/Hf ratios in rocks and Hf and Ti zoning in zircons: An example from the Spirit Mountain batholith, Nevada. Mineral. Mag. 2006, 70, 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniak, D.J.; Hanchar, J.M.; Watson, E.B. Rare-earth diffusion in zircon. Chem. Geol. 1997, 134, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee†, J.K.W.; Williams, I.S.; Ellis, D.J. Pb, U and Th diffusion in natural zircon. Nature 1997, 390, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claiborne, L.L.; Miller, C.F.; Flanagan, D.M.; Clynne, M.A.; Wooden, J.L. Zircon reveals protracted magma storage and recycling beneath Mount St. Helens. Geology 2010, 38, 1011–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousova, E.; Griffin, W.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Fisher, N. Igneous zircon: Trace element composition as an indicator of source rock type. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2002, 143, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhu, D.-C.; Zhao, Z.-D.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Sui, Q.-L.; Hu, Z.-C.; Mo, X.-X. Magmatic zircons from I-, S- and A-type granitoids in Tibet: Trace element characteristics and their application to detrital zircon provenance study. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 53, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, A.D.; Berry, A.J. Formation of Hadean granites by melting of igneous crust. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.M.W.; Yakymchuk, C.; Spencer, C.J.; Keller, C.B.; Tapster, S.R. Revisiting the discrimination and distribution of S-type granites from zircon trace element composition. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2024, 633, 118638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.B.; Harrison, T.M. Zircon Thermometer Reveals Minimum Melting Conditions on Earliest Earth. Science 2005, 308, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, J.M.; Watson, E.B. New thermodynamic models and revised calibrations for the Ti-in-zircon and Zr-in-rutile thermometers. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2007, 154, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, C.B.; John, B.E.; Kelemen, P.B.; Mazdab, F.K.; Wooden, J.L.; Cheadle, M.J.; Hanghøj, K.; Schwartz, J.J. Trace element chemistry of zircons from oceanic crust: A method for distinguishing detrital zircon provenance. Geology 2007, 35, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, C.B.; Wooden, J.L.; Cheadle, M.J.; John, B.E. “Fingerprinting” tectono-magmatic provenance using trace elements in igneous zircon. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2015, 170, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, T.L.; Miller, C.F.; Wooden, J.L.; Padilla, A.J.; Schmitt, A.K.; Economos, R.C.; Bindeman, I.N.; Jordan, B.T. Iceland is not a magmatic analog for the Hadean: Evidence from the zircon record. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 405, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilles, J.H.; Kent, A.J.R.; Wooden, J.L.; Tosdal, R.M.; Koleszar, A.; Lee, R.G.; Farmer, L.P. ZIRCON COMPOSITIONAL EVIDENCE FOR SULFUR-DEGASSING FROM ORE-FORMING ARC MAGMAS*. Econ. Geol. 2015, 110, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, N.J.; Hawkesworth, C.J.; Robb, L.J.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Roberts, N.M.W.; Kirkland, C.L.; Evans, N.J. Contrasting Granite Metallogeny through the Zircon Record: A Case Study from Myanmar. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolillo, L.; Chiaradia, M.; Ulianov, A. Zircon Petrochronology of the Kişladaǧ Porphyry Au Deposit (Turkey). Econ. Geol. 2021, 117, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, J.J.; Barra, F.; Reich, M.; Leisen, M.; Romero, R.; Morata, D. Episodic construction of the early Andean Cordillera unravelled by zircon petrochronology. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; McKenzie, N.R.; Colleps, C.L.; Chen, W.; Ying, Y.; Stockli, L.; Sardsud, A.; Stockli, D.F. Zircon isotope–trace element compositions track Paleozoic–Mesozoic slab dynamics and terrane accretion in Southeast Asia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2022, 578, 117298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Harrison, T.M. Geologic Evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan Orogen. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2000, 28, 211–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniel, C.; Vidal, P.; Fernandez, A.; Le Fort, P.; Peucat, J.-J. Isotopic study of the Manaslu granite (Himalaya, Nepal): Inferences on the age and source of Himalayan leucogranites. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 96, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Fort, P.; Cuney, M.; Deniel, C.; France-Lanord, C.; Sheppard, S.M.F.; Upreti, B.N.; Vidal, P. Crustal generation of the Himalayan leucogranites. Tectonophysics 1987, 134, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.; Massey, J. Decompression and anatexis of Himalayan metapelites. Tectonics 1994, 13, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño Douce, A.E.; Harris, N. Experimental Constraints on Himalayan Anatexis. J. Petrol. 1998, 39, 689–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, T.N.; Harris, N.B.W.; Warren, C.J.; Spencer, C.J.; Roberts, N.M.W.; Horstwood, M.S.A.; Parrish, R.R.; EIMF. The identification and significance of pure sediment-derived granites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 467, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kohn, M.J. Himalayan “S-type” granite generated from I-type sources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2500480122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-Y.; Liu, X.-C.; Liu, Z.-C.; Wang, R.-C.; Xie, L.; Wang, J.-M.; Ji, W.-Q.; Yang, L.; Liu, C.; Khanal, G.P.; et al. Highly fractionated Himalayan leucogranites and associated rare-metal mineralization. Lithos 2020, 352–353, 105319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.-W.; Pei, Q.-M.; Santosh, M.; Li, G.-M.; Zhang, L.-K.; Zhang, X.-F.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Zou, H.; Dai, Z.-W.; Lin, B.; et al. Himalayan leucogranites: A review of geochemical and isotopic characteristics, timing of formation, genesis, and rare metal mineralization. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 234, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-E.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, L.; Hou, K.; Guo, C.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y. Geochemical behavior of rare metals and high field strength elements during granitic magma differentiation: A record from the Borong and Malashan Gneiss Domes, Tethyan Himalaya, southern Tibet. Lithos 2021, 398–399, 106344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Z.; Teng, F.-Z.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Z.-C. Himalayan Leucogranites: A Geochemical Perspective. Elements 2024, 20, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, S.; Le Fort, P. Geochemical constraints on the bimodal origin of High Himalayan leucogranites. Lithos 1995, 35, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Gao, L.-E.; Xie, K.; Liu-Zeng, J. Mid-Eocene high Sr/Y granites in the Northern Himalayan Gneiss Domes: Melting thickened lower continental crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 303, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wilson, M. The Himalayan leucogranites: Constraints on the nature of their crustal source region and geodynamic setting. Gondwana Res. 2012, 22, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-C.; Wu, F.-Y.; Ji, W.-Q.; Wang, J.-G.; Liu, C.-Z. Petrogenesis of the Ramba leucogranite in the Tethyan Himalaya and constraints on the channel flow model. Lithos 2014, 208–209, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-C.; Wu, F.-Y.; Liu, X.-C.; Wang, J.-G.; Yin, R.; Qiu, Z.-L.; Ji, W.-Q.; Yang, L. Mineralogical evidence for fractionation processes in the Himalayan leucogranites of the Ramba Dome, southern Tibet. Lithos 2019, 340–341, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-Y.; Liu, Z.-C.; Liu, X.-C.; Ji, W.-Q. Himalayan leucogranite: Petrogenesis and implications to orogenesis and plateau uplift. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2015, 31, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, R.F. Himalayan leucogranites and migmatites: Nature, timing and duration of anatexis. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2016, 34, 821–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-E.; Zeng, L.; Asimow, P.D. Contrasting geochemical signatures of fluid-absent versus fluid-fluxed melting of muscovite in metasedimentary sources: The Himalayan leucogranites. Geology 2017, 45, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.-Z.; Zhao, J.-X.; He, C.-T.; Shi, R.-Z. Discovery of the Qongjiagang giant lithium pegmatite deposit in Himalaya, Tibet, China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2021, 37, 3277–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Gao, X.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-F. Geochemical evidence for partial melting of progressively varied crustal sources for leucogranites during the Oligocene–Miocene in the Himalayan orogen. Chem. Geol. 2022, 589, 120674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A.P.; Wooden, J.L. Coupled elemental and isotopic analyses of polygenetic zircons from granitic rocks by ion microprobe, with implications for melt evolution and the sources of granitic magmas. Chem. Geol. 2010, 277, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claiborne, L.L.; Miller, C.F.; Wooden, J.L. Trace element composition of igneous zircon: A thermal and compositional record of the accumulation and evolution of a large silicic batholith, Spirit Mountain, Nevada. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2010, 160, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, H.; Palin, R.M.; Dong, X.; Tian, Z.; Kang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, S.; Li, W. On the origin of high-pressure mafic granulite in the Eastern Himalayan Syntaxis: Implications for the tectonic evolution of the Himalayan orogen. Gondwana Res. 2022, 104, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-C.; Wu, F.-Y.; Ji, W.-Q.; Liu, X.-C.; Wang, J.-G. Monazite record of assimilation and differentiation processes in the petrogenesis of Himalayan leucogranites. Chem. Geol. 2023, 639, 121700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, J.L.; Waters, D.J.; Searle, M.P.; Bowring, S.A. Pleistocene melting and rapid exhumation of the Nanga Parbat massif, Pakistan: Age and P–T conditions of accessory mineral growth in migmatite and leucogranite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 288, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Gao, L.-E.; Dong, C.; Tang, S. High-pressure melting of metapelite and the formation of Ca-rich granitic melts in the Namche Barwa Massif, southern Tibet. Gondwana Res. 2012, 21, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.-Q.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Zeng, L.-S.; Gao, L.-E.; Huang, K.-X.; Li, W.; Li, Q.-Y.; Fu, Q.; Liang, W.; Sun, Q.-Z. Eocene–Oligocene granitoids in southern Tibet: Constraints on crustal anatexis and tectonic evolution of the Himalayan orogen. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 349–350, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-C.; Wu, F.-Y.; Ding, L.; Liu, X.-C.; Wang, J.-G.; Ji, W.-Q. Highly fractionated Late Eocene (~35Ma) leucogranite in the Xiaru Dome, Tethyan Himalaya, South Tibet. Lithos 2016, 240–243, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, X.; Xiang, H.; Ding, H.; Tian, Z.; Lei, H. Petrogenesis and tectonic implications of the Yadong leucogranites, southern Himalaya. Lithos 2016, 256–257, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.-Q.; Wu, F.-Y.; Liu, X.-C.; Liu, Z.-C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.-G.; Paterson, S.R. Pervasive Miocene melting of thickened crust from the Lhasa terrane to Himalaya, southern Tibet and its constraint on generation of Himalayan leucogranite. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 278, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, H.; Dong, X.; Tian, Z.; Kang, D.; Mu, H.; Qin, S.; Jiang, Y.; Li, M. High-Temperature Metamorphism, Anataxis and Tectonic Evolution of a Mafic Granulite from the Eastern Himalayan Orogen. J. Earth Sci. 2018, 29, 1010–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Palin, R.M.; Tian, Z.; Dong, X. Prolonged Partial Melting of Garnet Amphibolite from the Eastern Himalayan Syntaxis: Implications for the Tectonic Evolution of Large Hot Orogens. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2020, 125, e2019JB019119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Kohn, M.J.; Zhang, Z. Long-lived (ca. 22–24 Myr) partial melts in the eastern Himalaya: Petrochronologic constraints and tectonic implications. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 558, 116764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, K.; Klemd, R.; Yuan, Y.; He, Z.; Guo, J.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Z. The assembly of Rodinia: The correlation of early Neoproterozoic (ca. 900Ma) high-grade metamorphism and continental arc formation in the southern Beishan Orogen, southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB). Precambrian Res. 2017, 290, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, S.; Hu, Z.; Gao, C.; Zong, K.; Wang, D. Continental and Oceanic Crust Recycling-induced Melt–Peridotite Interactions in the Trans-North China Orogen: U–Pb Dating, Hf Isotopes and Trace Elements in Zircons from Mantle Xenoliths. J. Petrol. 2009, 51, 537–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.A.; Boehnke, P.; Harrison, T.M. Recovering the primary geochemistry of Jack Hills zircons through quantitative estimates of chemical alteration. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 191, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-J.; Richards, J.P.; Rees, C.; Creaser, R.; DuFrane, S.A.; Locock, A.; Petrus, J.A.; Lang, J. Elevated Magmatic Sulfur and Chlorine Contents in Ore-Forming Magmas at the Red Chris Porphyry Cu-Au Deposit, Northern British Columbia, Canada. Econ. Geol. 2018, 113, 1047–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1989, 42, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inger, S.; Harris, N. Geochemical Constraints on Leucogranite Magmatism in the Langtang Valley, Nepal Himalaya. J. Petrol. 1993, 34, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.; Ayres, M.; Massey, J. Geochemistry of granitic melts produced during the incongruent melting of muscovite: Implications for the extraction of Himalayan leucogranite magmas. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1995, 100, 15767–15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.M.; Grove, M.; Lovera, O.M.; Catlos, E.J. A model for the origin of Himalayan anatexis and inverted metamorphism. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1998, 103, 27017–27032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.-Q.; Wu, F.-Y.; Chung, S.-L.; Wang, X.-C.; Liu, C.-Z.; Li, Q.-L.; Liu, Z.-C.; Liu, X.-C.; Wang, J.-G. Eocene Neo-Tethyan slab breakoff constrained by 45 Ma oceanic island basalt–type magmatism in southern Tibet. Geology 2016, 44, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeming, Z.; Hua, X.; Huixia, D.; Xin, D.; Zhengbin, G.; Zhulin, T.; Santosh, M. Miocene orbicular diorite in east-central Himalaya: Anatexis, melt mixing, and fractional crystallization of the Greater Himalayan Sequence. GSA Bull. 2017, 129, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, T.; Zhang, B.; Fan, Y. Himalayan Miocene adakitic rocks, a case study of the Mayum pluton: Insights into geodynamic processes within the subducted Indian continental lithosphere and Himalayan mid-Miocene tectonic regime transition. GSA Bull. 2021, 133, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-C.; Wang, J.-G.; Liu, X.-C.; Liu, Y.; Lai, Q.-Z. Middle Miocene ultrapotassic magmatism in the Himalaya: A response to mantle unrooting process beneath the orogen. Terra Nova 2021, 33, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.; Gao, S. Composition of the Continental Crust. Treatise Geochem. 2003, 3, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskin, P.W.O.; Schaltegger, U. The Composition of Zircon and Igneous and Metamorphic Petrogenesis. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 53, 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trail, D.; Bruce Watson, E.; Tailby, N.D. Ce and Eu anomalies in zircon as proxies for the oxidation state of magmas. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 97, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.R.; Palin, J.M.; Campbell, I.H. Relative oxidation states of magmas inferred from Ce(IV)/Ce(III) in zircon: Application to porphyry copper deposits of northern Chile. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2002, 144, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, B.W.; White, A.J.R. I- and S-type granites in the Lachlan Fold Belt. In The Second Hutton Symposium on the Origin of Granites and Related Rocks; Brown, P.E., Chappell, B.W., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1992; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Trail, D.; Watson, E.B.; Tailby, N.D. The oxidation state of Hadean magmas and implications for early Earth’s atmosphere. Nature 2011, 480, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zheng, Y.-F.; Mayne, M.J.; Zhao, Z.-F. Miocene high-temperature leucogranite magmatism in the Himalayan orogen. GSA Bull. 2020, 133, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zheng, Y.-F.; Zhao, Z.-F. Distinction between S-type and peraluminous I-type granites: Zircon versus whole-rock geochemistry. Lithos 2016, 258–259, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Tao, X.; Wang, R.; Wu, F.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, R. Highly fractionated leucogranites in the eastern Himalayan Cuonadong dome and related magmatic Be–Nb–Ta and hydrothermal Be–W–Sn mineralization. Lithos 2020, 354–355, 105286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.-F.; Qin, K.-Z.; He, C.-T.; Wu, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.-C.; Niu, X.-L.; Mo, L.-C.; Liu, X.-C.; Zhao, J.-X. Li-Be-Nb-Ta mineralogy of the Kuqu leucogranite and pegmatite in the Eastern Himalaya, Tibet, and its implication. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2021, 37, 3305–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-M.; Zhang, L.-K.; Jiao, Y.-J.; Xia, X.-B.; Dong, S.-L.; Fu, J.-G.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.-Y.; Dong, L.; et al. First discovery and implications of Cuonadong superlarge Be-W-Sn polymetallic deposit in Himalayan metallogenic belt, southern Tibet. Miner. Depos. 2017, 36, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, B.W.; White, A.J.R. Two contrasting granite type. Pac. Geol. 1974, 8, 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz, C.E.; Stolper, E.M.; Eiler, J.M.; Breaks, F.W. A Comparison of Oxygen Fugacities of Strongly Peraluminous Granites across the Archean–Proterozoic Boundary. J. Petrol. 2018, 59, 2123–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Campbell, I.H.; Allen, C.M.; Burnham, A.D. S-type granites: Their origin and distribution through time as determined from detrital zircons. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020, 536, 116140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichavant, M.; Montel, J.-M.; Richard, L.R. Apatite solubility in peraluminous liquids: Experimental data and an extension of the Harrison-Watson model. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 3855–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholz, C.E. Coevolution of sedimentary and strongly peraluminous granite phosphorus records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2022, 596, 117795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakymchuk, C.; Kirkland, C.L.; Clark, C. Th/U ratios in metamorphic zircon. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2018, 36, 715–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, A.S.; Hermann, J.; Rubatto, D.; Rapp, R.P. Experimental study of monazite/melt partitioning with implications for the REE, Th and U geochemistry of crustal rocks. Chem. Geol. 2012, 300–301, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).