Abstract

Understanding the influence of strike–slip faulting on deep carbonate reservoirs remains challenging. This study integrates core observations, well logging, and seismic interpretation to investigate fracture diagenesis and evaluate the impact of strike–slip faulting on Upper Permian reef–shoal reservoirs in the northern Sichuan Basin. Within the platform margin reef–shoal microfacies, transtensional faulting during the Late Permian was later overprinted by transpressional deformation in the Early–Middle Triassic. Although individual fault displacements are generally less than 200 m, the associated damage zones may extend over 1000 m in width. Strong compaction and cementation eliminated most primary porosity in the reef–shoal carbonates, whereas dissolution enhanced porosity preferentially developed along fault damage zones. The most productive of fracture–vug reservoirs (“sweet spots”) are mainly distributed adjacent to strike–slip fault zones within the reef–shoal bodies. Reservoir quality is controlled by syn-sedimentary faults, moldic vugs, karstic argillaceous fills, and U-Pb ages of fracture cements that indicate multi-stage diagenesis. Contemporaneous fracturing and dissolution during the Late Permian played a dominant role in enhancing reservoir porosity, while burial-stage cementation had a detrimental effect. This case study demonstrates that even small-scale strike–slip faulting can significantly improve reservoir quality in deep tight reef–shoal carbonates.

1. Introduction

Strike–slip faults play a critical role in tectonic evolution and subsurface fluid migration [1,2,3]. They are typically characterized with nearly vertical fault planes, horizontal displacement, and narrow damage zones. The width of a fault damage zone generally follows a power-law relationship with displacement [4,5], implying that small-displacement strike–slip faults typically generate narrow fracture zones and exert limited influence on reservoir quality. Nevertheless, strike–slip faulting can influence localized reef–shoal microfacies and distribution, subsequently affecting reservoir development [6,7,8,9,10]. Porosity and permeability in tight reef–shoal reservoirs located within strike–slip fault zones may increase by more than two-fold and by an order of magnitude, respectively [10]. As a result, the impact of small-scale strike–slip faulting has been underestimated. However, the mechanism by which such faulting controls reservoir porosity in the deep subsurface remains inadequately understood.

The concept of structural or fracture diagenesis [11,12,13] provides a framework for understanding the effects of fracturing on reservoir evolution within fault zones. Fracture diagenesis has been shown to significantly facilitate fluid flow and hydrocarbon migration in sedimentary basins [14,15,16,17]. Fracture networks can increase permeability by one to three orders of magnitude and generate secondary porosity through dissolution during paragenetic, burial, or supergene diagenetic stages [16,17,18]. In contrast, repeated fracture cementation during burial can obstruct pore networks and reduce permeability [19,20,21]. Despite its importance, fracture diagenesis associated with small strike–slip faults has received limited attention, and its effects on reef–shoal reservoir quality remain largely unquantified.

The Permian carbonate reservoir in the Sichuan Basin is one of the major natural gas production targets in China [22]. Large gas accumulations have been discovered in Upper Permian reef–shoal reservoirs along the Kaijiang–Liangping trough (KLT) in the northern basin. These reservoirs are commonly attributed to high-energy reef–shoal microfacies developed along the carbonate platform margin [22,23,24,25], yet they are characterized by low porosity and permeability and poor production performance. Seismic interpretation has recently identified strike–slip faults along the KLT [26]; fracture networks associated with these faults may significantly improve gas recovery from deep, tight carbonates [27]. However, strike–slip impact on reservoir properties remain insufficiently constrained. Many wells encounter low porosity–permeability intervals with poor gas productivity, underscoring the need to clarify the relationship between fault-related diagenesis and reservoir development.

In this study, we conduct fracture diagenesis analysis based on an integrated core, well logging, and seismic data to characterize strike–slip faults, fracture networks, and diagenetic features within reef–shoal reservoirs in the southeastern KLT. We further evaluate the influence of small-scale strike–slip faulting on platform margin reef–shoal reservoir development.

2. Geological Background

The Sichuan Basin, located in southwestern China (Figure 1a), is a large intracratonic basin that has undergone multiple tectonic and sedimentary evolutionary stages [28]. A widespread Ediacaran–Ordovician carbonate platform was developed across the basin, followed by the denudation of Silurian–Carboniferous strata related to the Caledonian–Hercynian tectonic events. The carbonate deposition resumed from the Carboniferous through the Middle Triassic and was unconformably overlain by Late Triassic–Cretaceous siliciclastic successions. Several major unconformities formed in association with regional uplift and denudation during the Indosinian and Himalayan orogenic movements.

Figure 1.

Tectonic setting showing the location of the Sichuan Basin (a), structural configuration of the Kaijiang–Liangping trough (b), and the stratigraphic column of the Upper Permian interval (c) (modified after [21]; FXG: Feixianguan Formation).

The Kaijiang–Liangping trough (KLT) is an NWW-trending structural depression bounded by platform margins in the northern Sichuan Basin (Figure 1b). Following emplacement of the Emeishan LIP (large igneous province), the KLT is interpreted to have formed NE-directed extensional stress during the Late Permian [28,29]. The trough features relatively thin shale deposits and is flanked by carbonate platform margins developed within the Changxing Formation. The platform margin evolved from a gentle ramp to a rimmed platform [24,29], where thick (up to 300 m) reef–shoal successions accumulated. It comprises multiple bioclastic shoals interbedded with reef frameworks [22,23,24,25]. Shales of the Longtan Formation have high total organic carbon (TOC) contents (>2%), indicating excellent hydrocarbon source potential. The combination of Upper Permian trough shale source rocks and adjacent reef–shoal reservoirs along the platform margin forms a favorable source reservoir assemblage. During the Early–Middle Triassic, the KLT progressively filled with marine carbonates. Subsequent Indosinian tectonism caused regional uplift of the basin and transition to terrestrial deposition, followed by deep burial beneath thick Late Triassic siliciclastic strata [28,29]. Under prolonged burial conditions in the Changxing Formation, the reef–shoal reservoirs typically exhibit low porosity (<6%) and low permeability (<2 mD) [27].

Recent seismic interpretation has identified several NW-trending strike–slip faults along the KLT [26]. These faults show relatively small displacements in the Permian, yet associated fractured reservoirs have been detected through reservoir characterization and borehole data. Fault damage zones locally enhance permeability [27], and wells drilled near such zones consistently exhibit higher gas productivity. These observations indicate that strike–slip fault zones are favorable targets for fractured reservoirs and represent promising areas for gas exploitation in the KLT.

3. Data and Methods

A 3D seismic dataset covering over 1000 km2 was analyzed in the southeastern part of the KLT (Figure 1c). The top and base of the Changxing Formation were interpreted and mapped using the reprocessed seismic data [26]. To improve the imaging of small-scale deep strike–slip faults, a steerable pyramid reprocessing technique was applied, enabling a multi-directional seismic decomposition and reconstruction [26]. Seismic coherence and maximum likelihood attributes were used to delineate fault geometry, while seismic energy anisotropy—constrained by borehole data—was extracted to characterize fault damage zones. This approach is particularly effective for describing carbonate fault damage zones associated with strike–slip deformation. Because horizontal displacement is difficult to quantify, vertical displacement, damage zone width, and localized structural relief were used as proxies for fault deformation intensity.

Based on microfacies data from the Changxing Formation [22,23,24], the residual thickness method was applied to delineate reef–shoal distribution along the platform margin [30]. Core data and petrographic thin sections from 13 wells located within fault zones were used to characterize fracture attributes, including fracture frequency, dip angle, aperture, filling type, and brecciation features [27]. Diagenetic characteristics—such as compaction, cementation, and dissolution porosity—were also examined. Due to limited core coverage, FMI (formation micro-resistivity imaging) logging was employed to supplement fracture datasets and assess spatial variations in fracture density and orientation [27]. Sequential diagenetic evolution was interpreted based on crosscutting relationships, cementation sequences, and FMI image analysis. Porosity and permeability within carbonate fault damage zones were evaluated using CIFLog software 2.0 [27], calibrated against core measurements.

The timing of fault activity was constrained using seismic superposition, relationships, and the U-Pb dating of fracture-filling calcite cements [31,32]. Two calcite samples were collected from core fracture fillings for isotopic analysis. U–Pb age determinations followed the methodology described in [33]. The measured 238U/206Pb ratios were calibrated using an in-house standard (AHX-1d, 236.9 ± 1.7 Ma) to ensure reliability and accuracy. Data reduction was performed using the Iolite software package, and isotopic ages were plotted using IsoplotR (version 5.0) [33].

This integrated workflow enables a systematic evaluation of the relationship between fault activity, fracture diagenesis, and reef–shoal reservoir quality along the platform margin.

4. Results

4.1. The Strike–Slip Fault Distribution in the Platform Margin

Core and thin-section observations indicate that reef–shoal microfacies are well developed along the platform margin of the Changxing Formation (Figure 1c) [22,23,24]. The principal reef-building organisms comprise sponges, bryozoans, tabulate corals, and foraminifera, forming clustered, branching, and blocky reef structures that are interbedded with extensive grainstone deposits [23,24,25]. Three stacked reef–shoal cycles are recognized within the 200–300 m thick Changxing Formation. Residual thickness mapping indicates that reef–shoal bodies are continuously distributed along the platform margin (Figure 2). These bodies exhibit strong vertical aggradation and local thickening along the western margin, where reef–shoal complexes may exceed 2 km in width. The overall margin trends NW but gradually shifts to NE, forming multiple rows of stacked progradational reef–shoal belts up to 4 km wide.

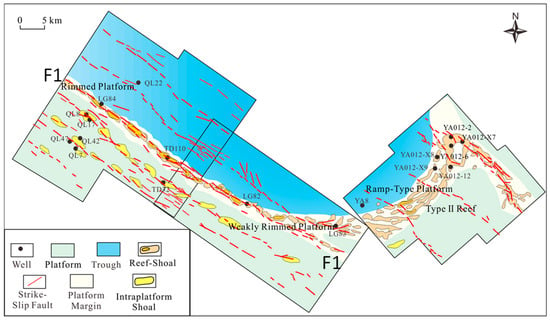

Figure 2.

Distribution of reef–shoal bodies and strike–slip faults within the Changxing Formation. (F1 represents the strike–slip fault zone along the platform margin; modified from [3]).

Seismic interpretation of the reprocessed high-resolution data identified a deep NW-trending strike–slip fault system within the study area (Figure 2). Four main fault zones can be defined from seismic imaging (Figure 3), including the following: (1) transtensional faults within the Cambrian–Ordovician and Changxing Formation and (2) transpressional faults below the Middle Permian and within the Early–Middle Triassic.

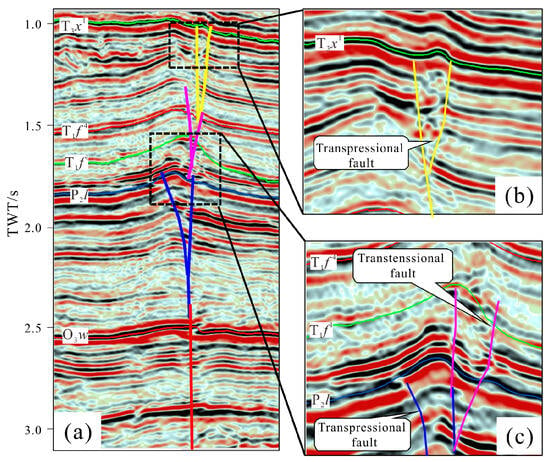

Figure 3.

(a) Representative seismic section showing four structural layers associated with strike–slip faulting. (b) Enlarged view of transtensional faulting within the Changxing Formation. (c) Enlarged view of transpressional faulting within the Triassic. Interpretation follows [30]. Red, blue, pink, and yellow lines represent strike–slip faults in different stratigraphic units. The strata interpretation is after reference [26]. T3x1: base of the Xujiahe Formation (Upper Triassic); T1f1: base of the Feixianguan Formation (Lower Triassic); T1f4: base of the fourth member of the Feixianguan Formation (Lower Triassic); P2l: base of the Changxing Formation (Upper Permian); O3w: top of the Upper Ordovician.

These two deformation episodes correspond to two transtensional–transpressional tectonic cycles. Later compressional deformation prior to the Late Triassic resulted in NE-trending folds that intersected the strike–slip fault zones. Within the Changxing Formation, vertical fault displacement ranges from 10 to 80 m, with most values below 40 m, indicating relatively weak deformation intensity. Laterally, the strike–slip faults display echelon and oblique segment arrangements (Figure 2), with individual faults 1–3 km in length. Segment overlap at fault tips and cross-cutting by secondary splays produce interaction and relay zones characterized by weak deformation and incomplete linkage. Although horizontal displacement is difficult to measure from seismic data estimation based on reef–shoal body offsets and structural anticline, deviation suggests values of less than 200 m. Structural relief along the fault zone is generally below 50 m. Despite its small displacement, the fault zone extends laterally for more than 70 km, demonstrating long strike length but weak vertical deformation.

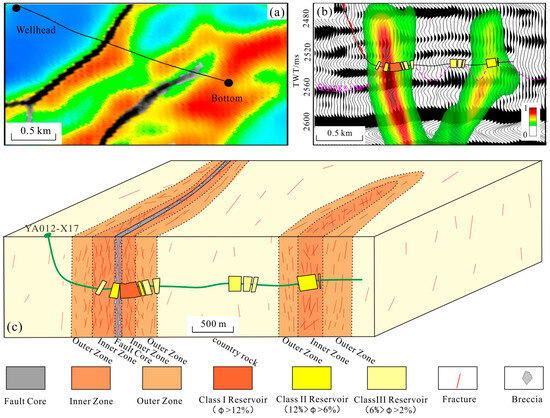

Borehole-calibrated seismic attribute analysis indicates that fault damage zones are well developed along the platform margin reef–shoal bodies (Figure 4). The width of the damage zone is positively correlated with fault scale. In Well Ya012-X7, a damage zone exceeding 1350 m in width was penetrated (Figure 4). These damage zones merge downward into the base of the Permian strata. Seismic anomalies, supported by borehole data, suggest that fractured reservoirs occur within the damage zones. These fractured intervals appear as columnar or elliptical clusters of high-amplitude seismic reflections and display segmented lateral continuity. Localized deformation associated with secondary splays and tip structures may increase damage zone width by more than twofold. The most intense deformation and reservoir development occur within segment overlap, bending, and intersection zones.

Figure 4.

(a) Plan view interpretation of a typical strike–slip fault damage zone. (b) Seismic cross-section of the damage zone. (c) Geological model illustrating reservoir classification (after [27]). Green–orange areas indicate seismic expression of the fault damage zone (after method in [30]).

4.2. Characteristics of Micro-Fractures

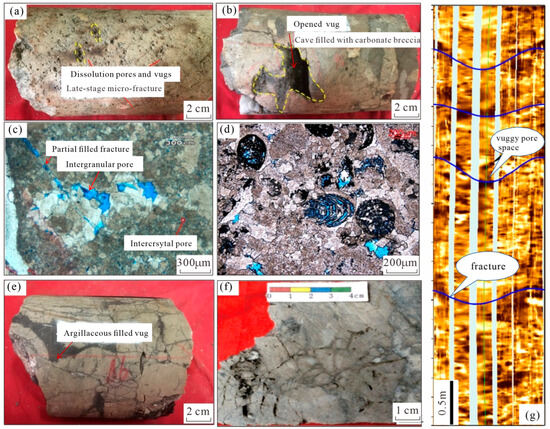

Core observations demonstrate that micro-fractures are well developed within the strike–slip fault damage zones (Figure 5). Stylolites are pervasive within the limestones, typically forming irregular, curved structures (Figure 5e,f). Local stylolite apertures may exceed 2 mm and are commonly enlarged by dissolution, producing jagged zigzag textures. Structural fractures are generally narrow but steeply inclined, with apertures ranging from 0.1 to 2 mm (Figure 5a,d). In the core of the damage zone, fracture apertures locally exceed 1 cm. Dense fracture networks commonly display cataclastic textures (Figure 5d), and dissolution pores are frequently present along fracture surfaces (Figure 5a,b). Wide fractures are partially to completely filled by calcite cements, while others contain dolomite, argillaceous materials or asphalt (Figure 5c,d). Cross-cutting relationships between fractures and stylolites indicate multiple fracturing and cementation stages. Later high-angle fractures cut across earlier argillaceous-filled fractures and stylolites, suggesting repeated fracture reactivation.

Figure 5.

Typical fracture photos in the Changxing Formation. ((a) Dissolution pores along the irregular fracture that intersected the grainstone, Well F003-2; (b) dissolution pores and fractures developed along the dolomitic grainstones, Well D002-11; (c) high-angle fracture with semi-filled calcite cements and postdate dissolution pores, Well TS5; (d) irregular micro-fractures terminated on the horizontal stylolite, Well D110; (e) expanded high-angle stylolite filled by dark argillaceous; (f) curved stylolite with dissolution pores, Well D110; (g) dark curves in FMI images showing fractures and dissolution vugs, Well LG82.)

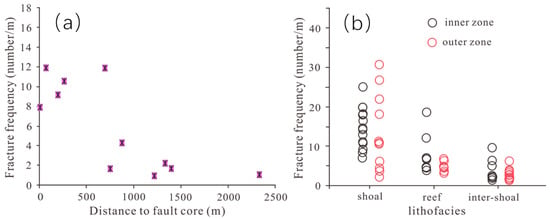

Spatial variation in fracture attributes is evident within the strike–slip fault zone. Fracture frequency increases markedly toward the fault core (Figure 6). While country rocks typically contain fewer than 1 fracture/m, the inner damage zone contains more than mudstones. The tectonic fracture frequency in the thin grainstones can be more than 10/m, with 9 fractures/m (e.g., Well TD110). Fractures are more abundant in grainstones than in mudstones, with tectonic fracture density exceeding 10/m in grainstones but typically being <4/m in intershoal mudstones.

Figure 6.

Fracture frequency versus distance from fault core (a) and fracture frequency in different lithofacies from the data of cores (b).

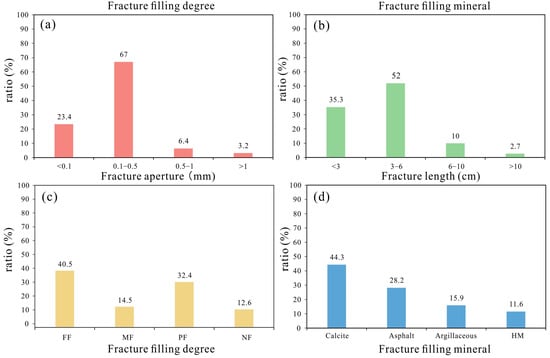

Structural fractures are predominantly high-angle to vertical, although moderately inclined fractures are also observed near fault cores. Most unfilled fractures have apertures < 0.5 mm, and fracture lengths are typically <6 cm (Figure 7a,b). Fractures within the inner damage zone exhibit high filling ratios (>80%), with the proportion decreasing toward the host rock (Figure 7c). Fracture-filling minerals consist mainly of calcite, with minor dolomite, asphalt, and hydrothermal minerals (Figure 7d). Significant variability in fracture aperture, filling degree, and mineral composition is observed among individual wells.

Figure 7.

Characteristics of fracture elements from core analysis: ((a) fracture aperture; (b) fracture length; (c) fracture-filling degree; (d) fracture-filling mineral; FF: full filling (>90%); MF: mostly filled (>50%); PF: partially filled (<50%); NF: non-filling; HM: hydrothermal mineral).

4.3. Fracture Diagenesis

During prolonged deep burial, the Permian carbonate rocks underwent intense mechanical compaction (Figure 5a,b). In transpressional domains, pressure dissolution led to the development of stylolites, resulting in tight intergranular contacts. Within fault damage zones, stylolites exhibit evidence of multiple stages of dissolution and cementation (Figure 5e,f).

Multiple generations of dissolution pores (<2 mm) and vugs (2–100 mm) are widely developed along fractures within the reef–shoal bodies (Figure 5 and Figure 8). Enlarged fractures commonly contain irregular dissolution pores (Figure 5a,c). Locally, large dissolution vugs and karstic cavities reaching 2–20 cm in diameter are present within fracture networks (Figure 8b,e). These dissolution features are particularly concentrated at the upper parts of reef–shoal bodies and within the inner fault damage zones. Fracture-related dissolution frequently propagates into adjacent matrix rocks, forming cluster-like pore systems and enhancing reservoir connectivity (Figure 8f,g). Strong dissolution generates patchy or clotted pores around fractures. Some dissolution pores occur within calcite fracture cements (Figure 5c) and within vug fillings (Figure 8c). Together with argillaceous and dolomite infills, fractures exhibit evidence of multiple dissolution phases. In FMI images (Figure 5g and Figure 8g), dissolved pores and vugs appear as dark linear or clustered patches along sinusoidal fracture traces. These observations suggest that diagenetic dissolution is more closely associated with fracture distribution than with lithofacies alone.

Figure 8.

The typical images of fracture diagenesis. (a) Needle-like dissolution vugs, densely distributed, locally filled with asphalt, Well TD110, 3703.78–3703.95 m; (b) karst caves, fracture expansion and dissolution, vug filling with argillaceous and calcite, Well TD110, 3699.70–3699.91 m; (c) dissolution vugs formed along the fractures, filled with dolomite and asphalt, intergranular micropores, Well QL8, 4165 m; (d) intergranular dissolution vugs, mold vugs, well LH002-X2, 3914.5 m; (e) reticular fracture, fracture expansion and dissolution, filled with argillaceous and calcite, Well TD110, 3693.8 m; (f) reticular fractures, dissolution vugs, filled with argillaceous and calcite, Well LG82, 4238 m; Well LG82; (g) FMI imaging logging showing high-angle fractures along with dissolution vugs.

Fractures are mostly filled by calcite cements with a high average filling ratio (>80%) (Figure 7c,d). Multiple cementation episodes are identified within both fractures and vugs. Early-stage fibrous calcite commonly precipitated along grain edges (Figure 8d), while later blocky and granular calcite cements fill the central portions of fractures and vugs. High-angle fractures near the top of reef–shoal reservoirs are frequently filled with argillaceous materials (Figure 5c and Figure 8e). Minor saddle dolomite cements are locally present among calcite fillings (Figure 8d), suggesting the involvement of hydrothermal fluids. Typically, two or more generations of cementation are typically observed within fault damage zones (Figure 5c and Figure 8c), compared with only one or two phases in surrounding country rocks.

4.4. U–Pb Ages of Fracture Cements

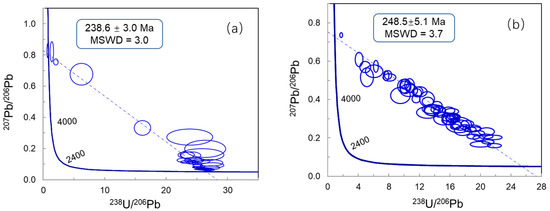

Two fracture cement samples collected from strike–slip fault zones yielded reliable in situ U-Pb isotope ages.

Sample S1, obtained from Well G2, consists of coarse blocky calcite filling a wide fracture. It yielded an age of 238.6 ± 3.0 Ma (MSWD = 3.0) (Figure 9a). The concordant 207Pb/235U and206Pb/238U ratios indicate that calcite cement precipitated during burial in the Middle Triassic.

Figure 9.

U-Pb concordia diagrams of samples S1 (a) and S2 (b) from fracture-vug cements within Permian strike–slip fault zones. Isotope data are presented with 2σ confidence ellipses. Dashed lines in concordia diagrams represent mixing between common-lead (upper intercept) and radiogenic-lead (lower intercept) endmembers. Lower intercept ages in Tera–Wasserburg plots display low MSWD values and were calculated using IsoplotR.

Sample S2, collected from a vertical fracture in well P4, yielded a similar age of 248.5 ± 3.7 Ma (MSWD = 2.2) (Figure 9b), corresponding to early-stage cementation during the Early Triassic.

These ages show that fault-related fluid migration and fracture diagenesis occurred between the Late Permian and Early Triassic, confirming that early syn-sedimentary fracturing was followed by cementation during shallow burial.

4.5. The Carbonate Reservoir

Core and logging data indicate that reservoirs within the Changxing Formation are primarily composed of grainstones and reef limestones. Most primary porosity was destroyed by compaction and cementation during prolonged burial (Figure 5b and Figure 8c). Matrix porosity is typically <3%, with permeability < 1 mD. Thus, reservoir pore space is dominated by secondary porosity, including fractures, dissolution pores, and vugs (Figure 5 and Figure 8). Reservoir development is most pronounced along fault-related fracture networks within reef–shoal bodies. Additional dissolution porosity occurs in limestones adjacent to the fault damage zone. Secondary porosity comprises complex combinations of fracture–vug, pore–vug, and fracture-type reservoir systems.

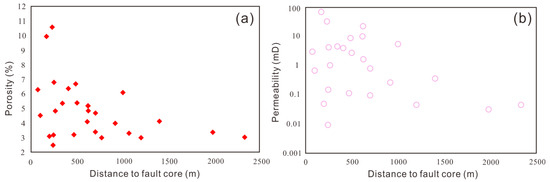

The thickness of fractured reservoir intervals ranges from 1 m to >30 m. Logging responses typically include low gamma, low density, medium–low resistivity, and high acoustic travel time. Drilling within these intervals often encounters gas kicks, mud losses, or borehole enlargement. Fracture networks connect dissolution porosity, forming highly permeable fractured reservoirs. Logging-derived porosity generally ranges from 2% to 8% and may reach 14% in localized fracture cavity reservoirs. Reservoir intervals with porosity > 6% and permeability >1 mD predominantly occur within 700 m of the fault core (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The reservoir average porosity (a) and permeability (b) from the logging data vs. the distance to the fault core.

5. Discussion

5.1. Timing of the Fractured Reservoirs

Regional uplift and denudation occurred at the end of the Middle Permian [28,29]. NW-trending strike–slip faults likely initiated during this phase, consistent with NW-directed transpressional faulting previously documented in the central Sichuan Basin [31]. Subsequent NE–SW extension associated with KLT development [28,29] progressively reactivated these structures as transtensional faults. Transtensional deformation within the Changxing Formation differs from the overlying and underlying transpressional faulting (Figure 3). Variations in fault geometry and displacement between stratigraphic levels, together with contrasts in lithology and microfacies, indicate syn-sedimentary transtensional activity during the Late Permian. Additionally, facies transitions from platform margin reef–shoal deposits (>200 m thick) to trough shales (<50 m thick) [21,22,23] and stratigraphic thickening between the hanging wall and footwall (Figure 3c) support this interpretation. Fault inversion occurred during the Indosinian compressional phase prior to the Late Triassic, when transtensional structures were overprinted by transpressional deformation (Figure 3). U–Pb dating ages of 238.6 Ma and 248.5 Ma (Figure 9) constrain fracturing prior to or during Early Triassic cementation. These observations indicate two primary faulting stages affecting the reservoir, namely Late Permian transtensional faulting, forming extensive syn-sedimentary damage zones within reef–shoal bodies and Early–Middle Triassic transpressional reactivation, partially overprinting earlier structures.

During syn-sedimentary fracturing, fracture porosity and dissolution porosity (Figure 5a,b and Figure 8c,f) developed contemporaneously. Intergranular and moldic porosity (Figure 8d) likely formed during early diagenesis. Argillaceous cement occurring within fractures is interpreted as meteoric cementation during Late Permian subaerial exposure, supporting contemporaneous fracturing and dissolution processes. Differential compaction and pressure dissolution near fault zones enhanced the formation of horizontal stylolites and localized dissolution porosity during early diagenesis (Figure 5b,d). Oblique and high-angle stylolites postdating earlier structures (Figure 5e) reflect progressive structural dissolution. Later calcite cements represent burial-stage reactivation and fluid migration. U–Pb ages (238.6 and 248.5 Ma) indicate large-scale burial cementation during the Early Triassic. Saddle dolomite and cement phases aged 235–250 Ma reported from comparable Permian reservoirs [32,33,34,35] support extensive cementation during the Early–Middle Triassic. Consequently, most fracture networks and associated dissolution porosity developed during contemporaneous Late Permian diagenesis.

During Triassic rapid subsidence, extensive calcite cementation (240–220 Ma) occluded much of the earlier porosity. Transpressional reactivation toward the end of the Middle Permian may have induced limited secondary porosity. Hydrothermal activity during burial generated localized dissolution and saddle dolomite (Figure 5c) but with limited net porosity enhancement. Late-stage reactivation (prior to Late Triassic) resulted in fracture generation mainly in Triassic strata, with a minor reactivation of Permian fractures. These fractures underwent limited dissolution before being sealed by late-stage cementation. Minor unfilled micro-fractures may represent Cenozoic reactivation associated with NE-trending thrust faults.

Overall, three main diagenetic stages are identified. The contemporaneous fracturing and dissolution during the Late Permian have resulted in the primary fracture–vug porosity. The early burial cementation during the Early–Middle Triassic caused extensive calcite filling and porosity loss. Late reactivation and sealing after Middle Triassic had weak re-fracturing and cementation on the reservoirs. These results indicate that fracture diagenesis predominantly occurred during the syn-sedimentary-to-early burial stages, consistent with similar fracture-controlled diagenesis reported in other basins [10,36,37,38]. Consequently, fractured reservoirs in the KLT reef–shoal bodies were primarily formed during Late Permian contemporaneous diagenesis.

5.2. Fault Effect on Reef–Shoal Reservoirs

Fracture frequency and petrophysical properties generally increase toward the fault core and decrease outward (Figure 6) [4,20]. Although the strike–slip faults in this study exhibit relatively small vertical displacement, their steep geometries generated fractured reservoirs extending several hundred meters from the fault core (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 10). Unlike large-scale karst systems formed through prolonged subaerial exposure [39,40,41], these fractured reservoirs developed primarily under syn-depositional and early diagenetic conditions, which is consistent with U–Pb cement ages of 250–220 Ma [31,32,33]. No unconformity or evidence of extensive post-depositional karstification is observed in the studied reservoirs [22,23,24,25].

Porosity increases of 1–5 times and permeability enhancement of 1–3 orders of magnitude are recorded within damage zones compared with surrounding country rocks (Figure 10). This trend follows a power-law increase towards the fault core, demonstrating that fracture networks play a key constructive role in reservoir improvement. Most deep reef–shoal reservoirs exhibit poor gas productivity, whereas high-production wells are typically associated with fracture–vug reservoirs characterized by interconnected dissolution features. Some fractured intervals yield stable high production, whereas others display rapid decline, likely due to localized diagenetic cementation reducing reservoir connectivity.

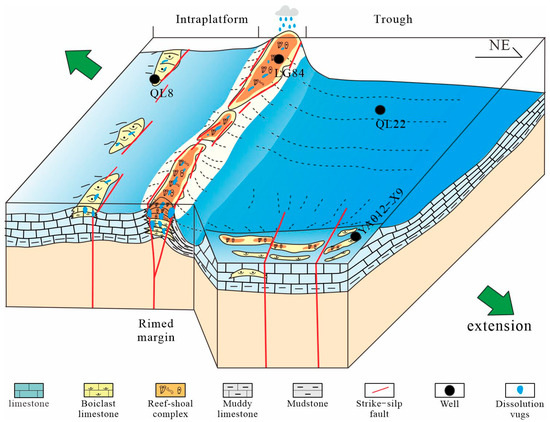

Reef–shoal microfacies exert strong primary control on reservoir development [22,23,24,25]. High-energy depositional environments promoted grainstone accumulation, which provided favorable precursor textures for dissolution. Syn-depositional diagenesis enhanced initial porosity, particularly in marginal shoals subject to periodic exposure. The average matrix porosity of limestones is <1.5%, whereas fine-grained shoal grainstones may exceed 3%. Fracture density is greater in grainstones and dolomites than in low-energy mudstones. During Late Permian deposition, syn-sedimentary strike–slip faults developed along the NW-trending platform margin (Figure 3) under regional extension [28,29]. These faults generated localized paleogeomorphic highs (Figure 11), which fostered preferential reef–shoal accumulation and enhanced meteoric dissolution. In these highlands, matrix porosity exceeded 4% (Figure 8a–c), whereas weaker strike–slip activity along the eastern platform margin resulted in reduced reservoir thickness and porosity. In multi-row northeast shoal belts, fault influence was minor and matrix porosity dominated. The best reservoir development occurs where syn-sedimentary faults intersect reef–shoal belts, enabling localized contemporaneous dissolution along fracture networks. Gas production in fractured reservoirs may exceed that of matrix reservoirs by more than an order of magnitude.

Figure 11.

The reservoir model of the contemporaneous dissolution porosity along the strike–slip fault zone within the Permian reef–shoal bodies (reef–shoal developed well within the rimmed margin along the strike–slip fault zone; the higher paleogeomorgraphy within the fault damage zone was favorable for the selective dissolution of the meteoric water).

Despite favorable microfacies, most reef–shoal carbonates are now tight due to long-term compaction and burial cementation [22,23,24]. Secondary porosity, especially that associated with fracture–vug systems, represents the primary reservoir space (Figure 5 and Figure 8). Late Permian fracturing followed by short-term meteoric dissolution produced well-connected fracture–vug networks. Dissolution originated along fracture corridors and extended into peripheral rocks, forming intra- and intergranular pores. Dissolution intensity and reservoir connectivity are greatest near fault cores and decrease rapidly outward. Similar contemporaneous karstic porosity and the fracture effect have been documented in the central Sichuan Basin [39] and the Tarim Basin [40,41]. During burial, hydrothermal and acidic fluids migrated along pre-existing fractures, producing localized dissolution within early calcite and dolomite cements [32]. However, this process contributed far less to reservoir enhancement than contemporaneous meteoric dissolution. Burial cementation and compaction are the dominant destructive processes, progressively reducing porosity and sealing fractures. U–Pb ages of 250–220 Ma (Figure 9) and evidence of rapid subsidence support extensive burial cementation (Figure 5 and Figure 8).

In summary, high-quality reservoirs formed primarily through Late Permian contemporaneous fracturing and dissolution along strike–slip fault zones (Figure 11). Reef–shoal carbonates accumulated along the NW-trending fault system, where syn-sedimentary uplift and sea-level regression led to brief subaerial exposure. Overlap and fault-tip zones produced fracture corridors up to 1000 m wide (Figure 4). Meteoric water infiltration along these networks generated fracture–vug reservoirs with enhanced porosity and permeability. Transpressional reactivation at the end of the Middle Triassic created secondary fractures but contributed little new porosity. As the strike–slip faults terminated below the Upper Triassic, burial cementation dominated, resulting in progressive reservoir degradation during deep diagenesis.

In summary, contemporaneous fracturing and dissolution had a constructive impact on reservoir development, whereas burial-stage cementation and compaction exerted a destructive effect on the Permian reef–shoal reservoirs.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Two faulting stages from transtensional (Late Permian) to transpressional (the end of the Middle Triassic) resulted in small-scale strike–slip faults along the platform margin in the northern Sichuan Basin. These faults produced wide damage zones and multi-stage fracture diagenesis.

- (2)

- Three principal stages of fracture diagenesis were identified, as follows: Late Permian syn-sedimentary fracturing and dissolution; extensive burial cementation during rapid subsidence in the Early–Middle Triassic; and limited reactivation and sealing prior to the Late Triassic.

- (3)

- Contemporaneous fracturing and dissolution at the end of the Permian generated fracture–vug “sweet spot” reservoirs within reef–shoal carbonates. This early fracture diagenesis exerted the most significant positive influence on reservoir quality. In contrast, subsequent burial diagenesis and compaction resulted in porosity loss and permeability reduction.

- (4)

- Even small-displacement strike–slip faults can create favorable fractured reservoirs when structural deformation is coupled with syn-depositional dissolution, providing critical implications for gas exploration in deep, tight reef–shoal reservoirs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W.; methodology, J.L. and X.L.; software, J.L. and Y.W.; investigation, X.L. and Y.W.; data curation, C.S. and B.H.; writing—original draft preparation, G.W. and Y.W.; visualization, C.S. and Y.Y.; supervision, Y.W. and B.H.; funding acquisition, B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U24B2019, 42402163) and the Science and Technology Cooperation Project of the CNPC-SWPU Innovation Alliance (grant no. 2020CX010101, 2020CX010301).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and reviewer for their comments regarding manuscript improvement. We also thank Hao Tang, Bingshan Ma, Yonghong Wu and Xiaojun Zhou for their help with the data.

Conflicts of Interest

Yinyu Wen, Bing He and Chen Su are employees of PetroChina Southwest Oil & Gasfield Company, Jiawei Liu is employee of Sinopec Exploration Company. The paper reflects the views of the scientists and not the company.

References

- Aydin, A.; Schultz, R.A. Effect of mechanical interaction on the development of strike-slip faults with echelon patterns. J. Struct. Geol. 1990, 12, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Sanderson, D.J. The relationship between displacement and length of faults. Earth Sci. Rev. 2005, 68, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, D.C.P.; Anderson, M.W. The scaling of pull-aparts and implications for fluid flow in areas with strike-slip faults. J. Pet. Geol. 2012, 35, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabia, A.; Berg, S.S. Scaling of fault attributes: A review. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2011, 28, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayolle, S.; Soliva, R.; Dominguez, S.; Wibberley, C.; Caniven, Y. Nonlinear fault damage zone scaling revealed through analog modeling. Geology 2021, 49, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainge, A.M.; Davies, K.G. Reef exploration in the East Sengkang Basin, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1985, 2, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédir, M.; Boukadi, N.; Tlig, S.; Timzal, F.B.; Zitouni, L.; Alouani, R.; Slimane, F.; Bobier, C.; Zargouni, F. Subsurface Mesozoic basins in the central Atlas of Tunisia: Tectonics, Sequence deposit distribution, and hydrocarbon potential. AAPG Bull. 2001, 85, 885–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolting, A.; Fernández-Ibáñez, F. Stress states of isolated carbonate platforms: Implications for development and reactivation of natural fractures post burial. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 128, 105039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Ran, Q.; Tian, W.; Liang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Zou, Y.; Su, C.; Wu, G. Strike-slip fault effects on diversity of the Ediacaran mound-shoal distribution in the Central Sichuan intracratonic basin, China. Energies 2022, 15, 5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Scarselli, N.; Yan, W.; Sun, C.; Han, J. The strike-slip fault effects on tight Ordovician reef-shoal reservoirs in the central Tarim Basin (NW China). Energies 2023, 16, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubach, S.E.; Eichhubl, P.; Hilgers, C.; Lander, R.H. Structural diagenesis. J. Struct. Geol. 2010, 32, 1866–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Yasuhara, H. An evaluation of the effects of fracture diagenesis on hydraulic fracturing treatment. Geosystem Eng. 2013, 16, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Xie, E.; Zhang, Y.F.; Qing, H.R.; Luo, X.S.; Sun, C. Structural diagenesis in carbonate fault damage zones in the northern Tarim Basin, NW China. Minerals 2019, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhubl, P.; Davatzes, N.C.; Becker, S.P. Structural and diagenetic control of fluid migration and cementation along the Moab fault, Utah. AAPG Bull. 2009, 93, 653–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeginste, V.; Swennen, R.; Allaeys, M.; Ellam, R.M.; Osadetz, K.; Roure, F. Challenges of structural diagenesis in foreland fold-and-thrust belts: A case study on paleofluid flow in the Canadian Rocky Mountains West of Calgary. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2012, 35, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Paton, D.A.; Knipe, R.J.; Wu, K.Y. A review of fault sealing behaviour and its evaluation in siliciclastic rocks. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015, 150, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.T.; Goodwin, L.B.; Mozley, P.S. Diagenetic controls on the evolution of fault-zone architecture and permeability structure: Implications for episodicity of fault-zone fluid transport in extensional basins. GSA Bull. 2017, 129, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marghani, M.M.A.; Zairi, M.; Radwan, A.E. Facies analysis, diagenesis, and petrophysical controls on the reservoir quality of the low porosity fluvial sandstone of the Nubian formation, east Sirt Basin, Libya: Insights into the role of fractures in fluid migration, fluid flow, and enhancing the permeability of low porous reservoirs. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 147, 105986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehl, B.C.; Reuning, L.; Schoenherr, J.; Lueders, V.; Kukla, P.A. Impacts of hydrothermal dolomitization and thermochemical sulfate reduction on secondary porosity creation in deeply buried carbonates: A case study from the Lower Saxony Basin, northwest Germany. AAPG Bull. 2016, 100, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Zhao, K.Z.; Qu, H.Z.; Nicola, S.; Zhang, Y.T.; Han, J.F.; Xu, Y.F. Permeability distribution and scaling in multi-stages carbonate damage zones: Insight from strike-slip fault zones in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 114, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.J.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Y.C.; Chen, H.H.; Ping, H.W.; Fang, X.J. Structural diagenesis and reservoir control analysis of tight sandstone in the strike-slip fault zones of the Chang 8 to Chang 6 Members in the Jinghe Oilfield. Bullet Geol. Sci. Technol. 2025, 44, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wen, L.; Zhou, G.; Zhan, W.; Li, H.; Song, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tao, J.; Tian, X.; Yuan, J. New fields, new types and resource potentials of hydrocarbon exploration in Sichuan Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2023, 44, 2045–2069, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.Z.; Xu, C.C.; Wang, T.S.; Wang, H.J.; Wang, Z.C.; Bian, C.S.; Li, X. Comparative study of gas accumulations in the Permian Changxing reefs and Triassic Feixianguan oolitic reservoirs between Longgang and Luojiazhai-Puguang in the Sichuan Basin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 3310–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.M.; Hu, Z.G.; Chen, S.Y.; Yuan, B.G.; Dai, X. Reef–shoal combinations and reservoir characteristics of the Changxing–Feixianguan Formation in the eastern Kaijiang–Liangping trough, Sichuan Basin, China. Carbonates Evaporites 2021, 36, 00698-6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.P.; Li, B.S.; Duan, J.B.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Zou, H.Y.; Hao, F. Sulfate sources of thermochemical sulfate reduction and hydrogen sulfide distributions in the Permian Changxing and Triassic Feixianguan formations, Sichuan Basin, SW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 145, 105892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Tang, S.; Luo, B.; Luo, X.; Feng, L.; Li, S.; Wu, G. Seismic description of deep strike-slip fault damage zone by steerable pyramid method in the Sichuan Basin, China. Energies 2022, 15, 8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Feng, L.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Wu, G.; Luo, B. The fractured Permian reservoir and its significance in the gas exploitation in the Sichuan Basin, China. Energies 2023, 16, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.G.; Yang, Y.; Deng, B.; Zhong, Y.; Wen, L.; Sun, W.; Li, Z.W.; Jansa, L.; Li, J.X.; Song, J.M.; et al. Tectonic evolution of the Sichuan Basin, Southwest China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 213, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Z.; Li, B.; Wen, L.; Xu, L.; Xie, S.Y.; Du, Y.; Feng, M.Y.; Yang, X.F.; Wang, Y.P.; Pei, S.Q. Characteristics of “Guangyuan-Wangcang” trough during late Middle Permian and its petroleum geological significance in northern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Wu, G.H.; Tang, Q.S.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Zhao, Z.Y. Effects of intracratonic strike-slip fault on the differentiation of carbonate microfacies: A case study of a Permian platform margin in the Sichuan Basin (SW China). Acta Geol. Sin. 2024, 98, 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.S.; Liang, H.; Wu, G.H.; Tang, Q.S.; Tian, W.Z.; Zhang, C.; Yang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.L. Formation and evolution of the strike-slip faults in the central Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.F.; Zheng, J.F.; Dai, K.; Hong, S.X.; Duan, J.M.; Liu, Y.M. Petrological, geochemical and chronological characteristics of dolomites in the Permian Maokou Formation and constraints to the reservoir genesis, central Sichuan Basin, China. Minerals 2023, 13, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Jiang, T.; Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Qiu, C.; Liu, T.; Deng, M.; Tian, W. Timing and Effect of the Hidden Thrust Fault on the Tight Reservoir in the Southeastern Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.Y.; Shang, J.X.; Shen, A.J.; Wen, L.; Wang, X.Z.; Xu, L.; Liang, F.; Liu, X.H. Episodic hydrothermal alteration on Middle Permian carbonate reservoirs and its geological significance in southwestern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.S.; Zhou, R.J.; Mou, C.L.; Ge, X.Y.; Hou, Q.; Zhao, J.X.; Howard, D. Origins of the Upper Permian reef-dolostone and reservoir evolution in northern South China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 162, 106748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucchi, P. Segmented, curved faults: The example of the Balduini Thrust Zone, Northern Apennines, Italy. J. Struct. Geol. 1999, 21, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.; Budai, T.; Győri, O.; Kele, S. Multiphase partial and selective dolomitization of Carnian reef limestone (Transdanubian Range, Hungary). Sedimentology 2014, 61, 836–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.D.; Yuan, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Yang, X.Z.; Dong, D.T.; Ma, P.J.; Huang, C.Q. Diagenesis of the Paleogene sandstones in the DN2 Gas Field, Kuqa foreland basin and its link to tectonics. Acta Geol. Sin. 2023, 97, 1538–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, C.; Liu, Y.; Su, C.; Tang, Q.; Tian, W.; Wu, G. The strike-slip fault effects on the Ediacaran carbonate tight reservoirs in the central Sichuan Basin, China. Energies 2023, 16, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.B.; Shi, J.X.; Ma, Q.Y.; Lyu, W.Y.; Dong, S.Q.; Cao, D.S.; Wei, H.H. Strike-slip fault control on karst in ultra-deep carbonates, Tarim Basin, China. AAPG Bull. 2024, 108, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.L.; Chen, L.X.; Su, Z.; Dong, H.Q.; Ma, B.S.; Zhao, B.; Lu, Z.D.; Zhang, M. Differential characteristics of conjugate strike-slip faults and their controls on fracture-cave reservoirs in the Halahatang area of the northern Tarim Basin, NW China. Minerals 2024, 14, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).