Genetic and Sealing Mechanisms of Calcareous Sandstones in the Paleogene Zhuhai–Enping Formations, Panyu A Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

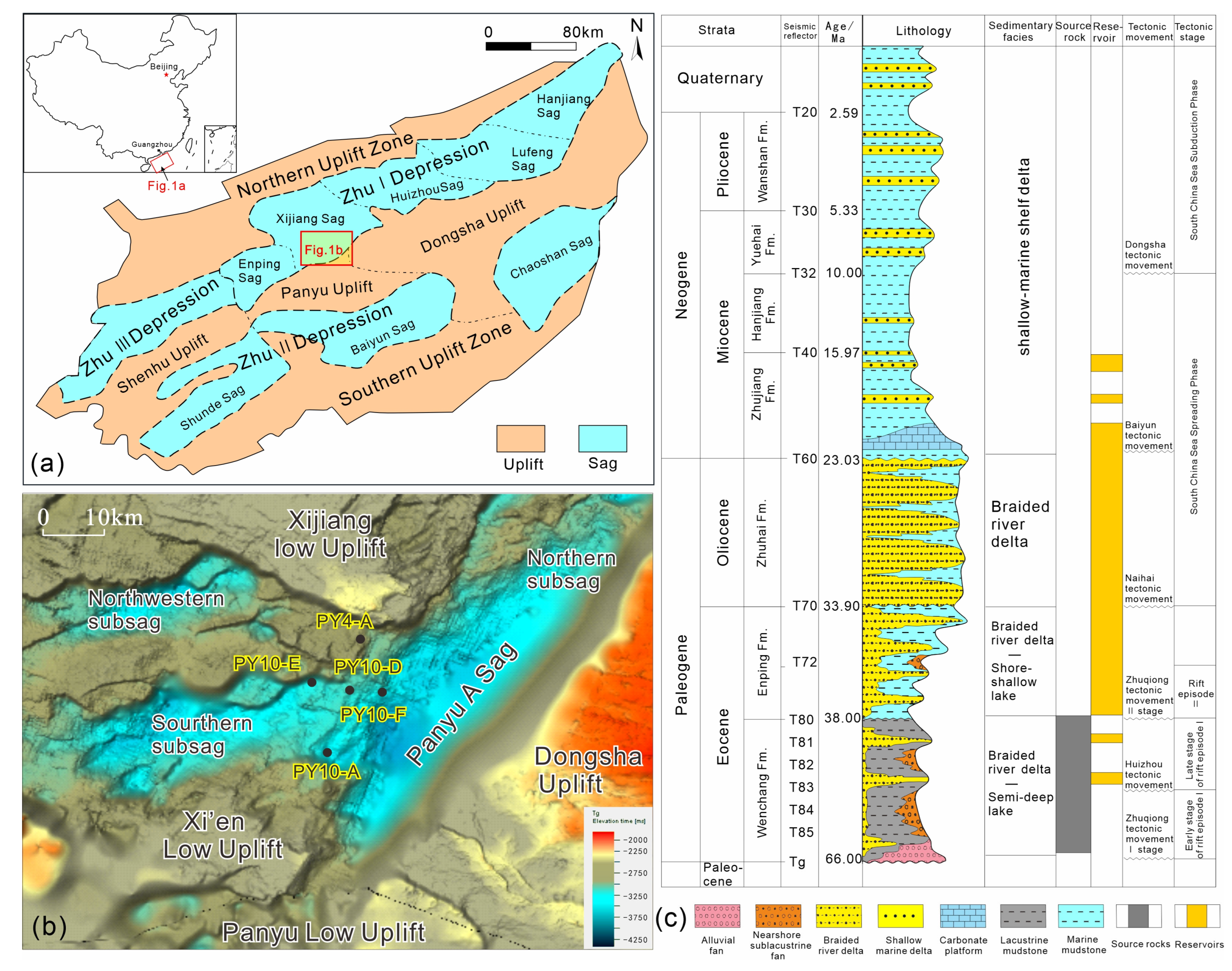

2. Regional Geological Background

2.1. Structural Location

2.2. Stratigraphy

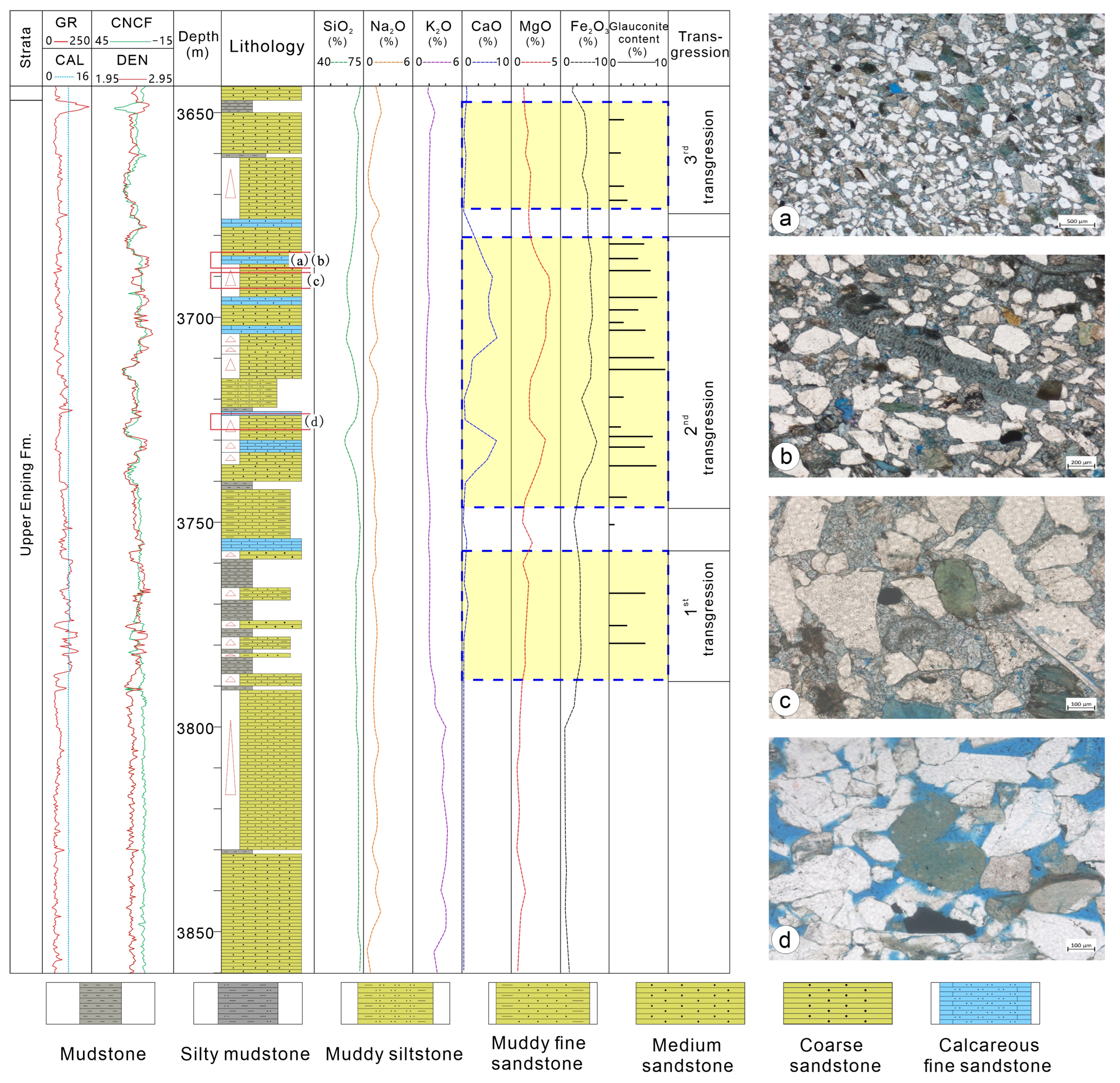

2.3. Sedimentary Characteristics

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

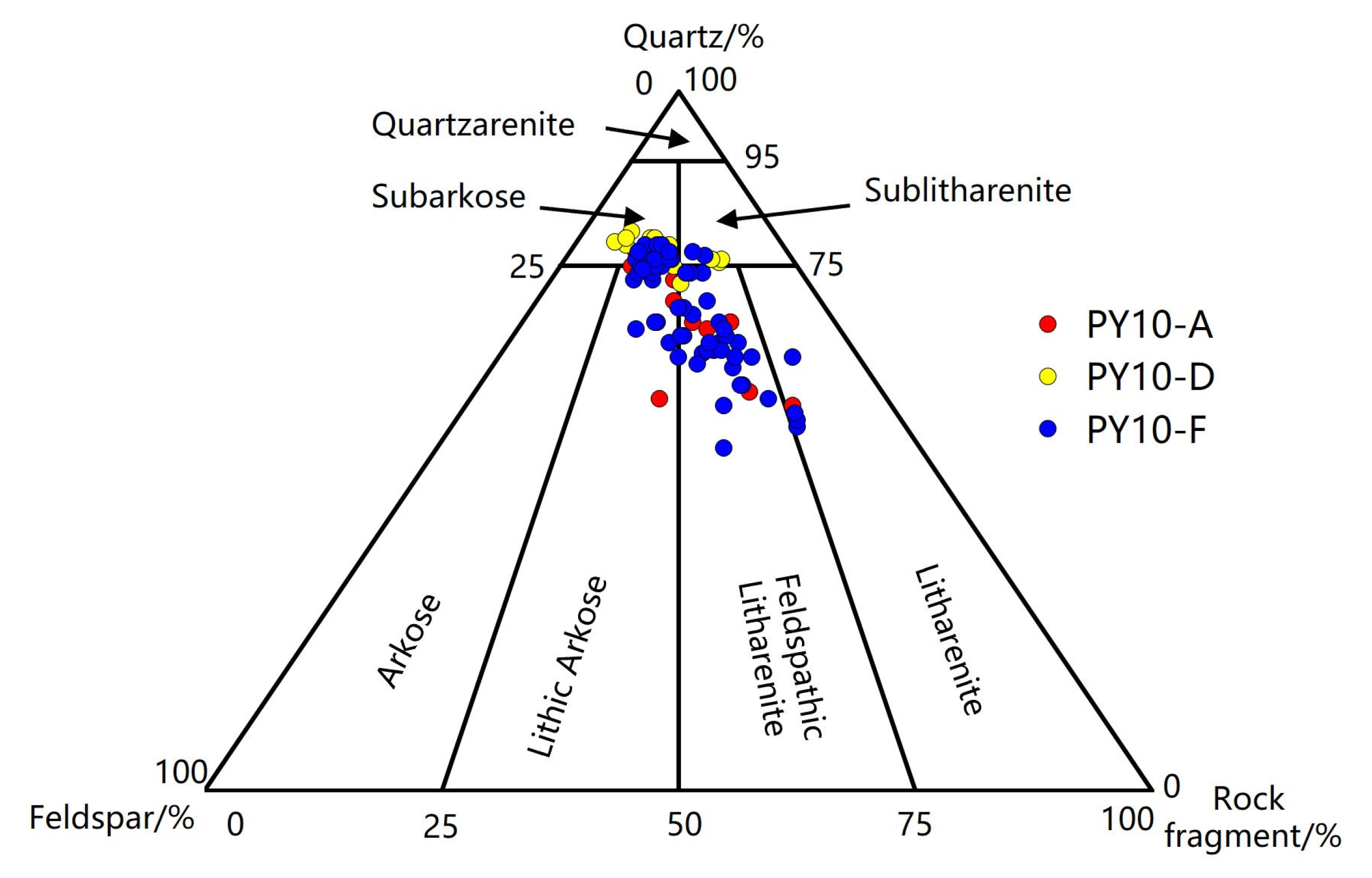

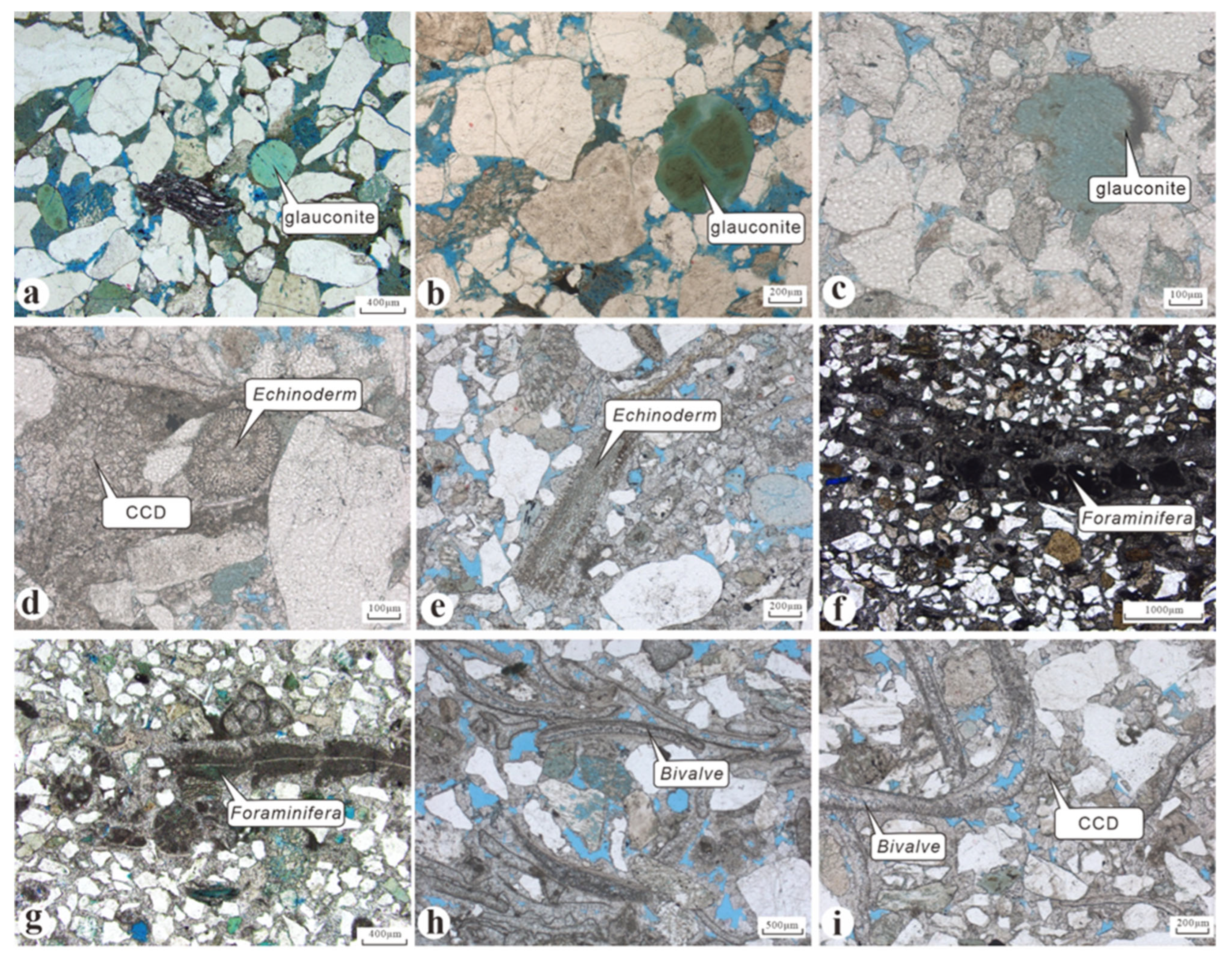

4.1. Petrological Characteristics of Calcareous Sandstones

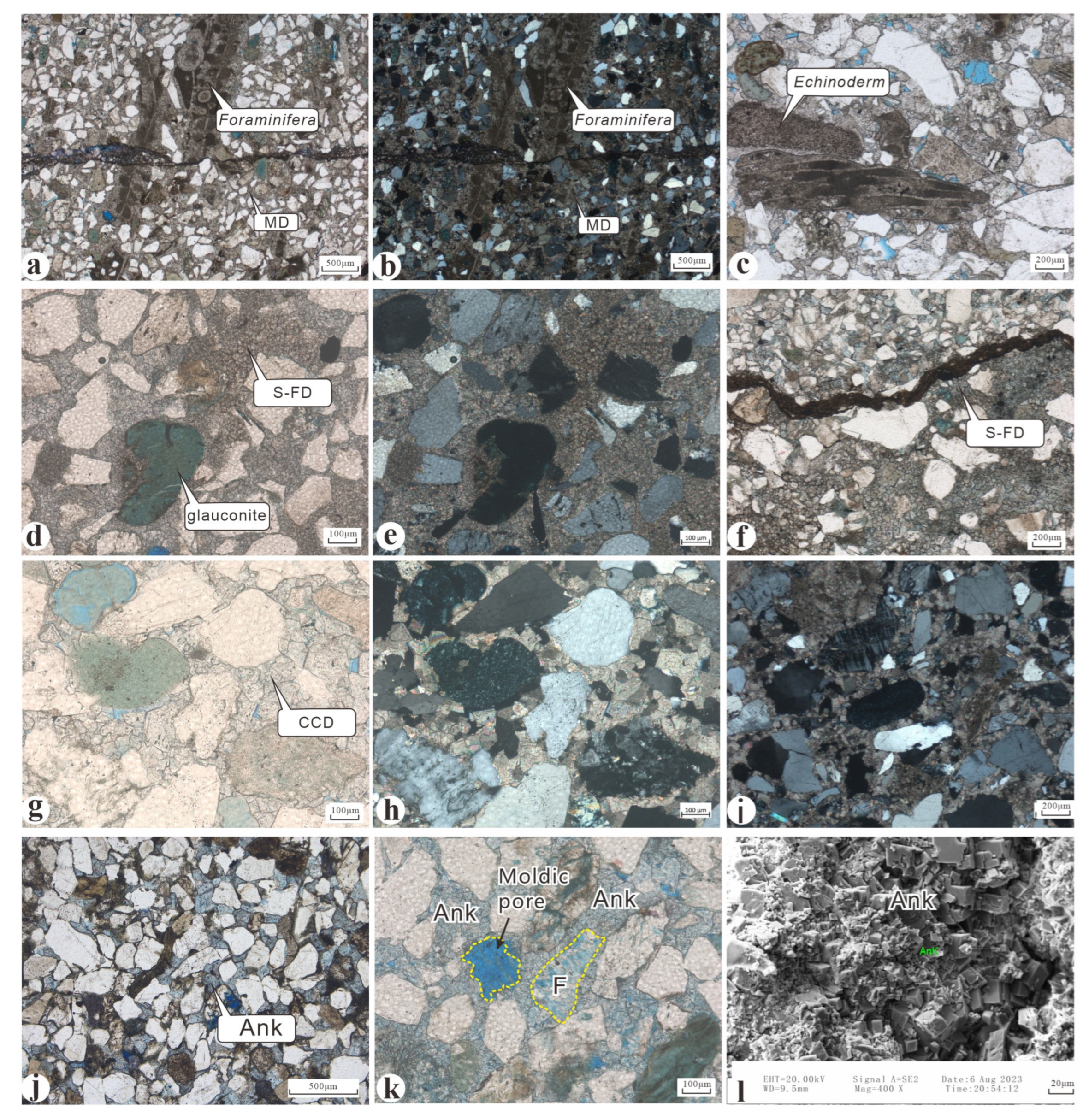

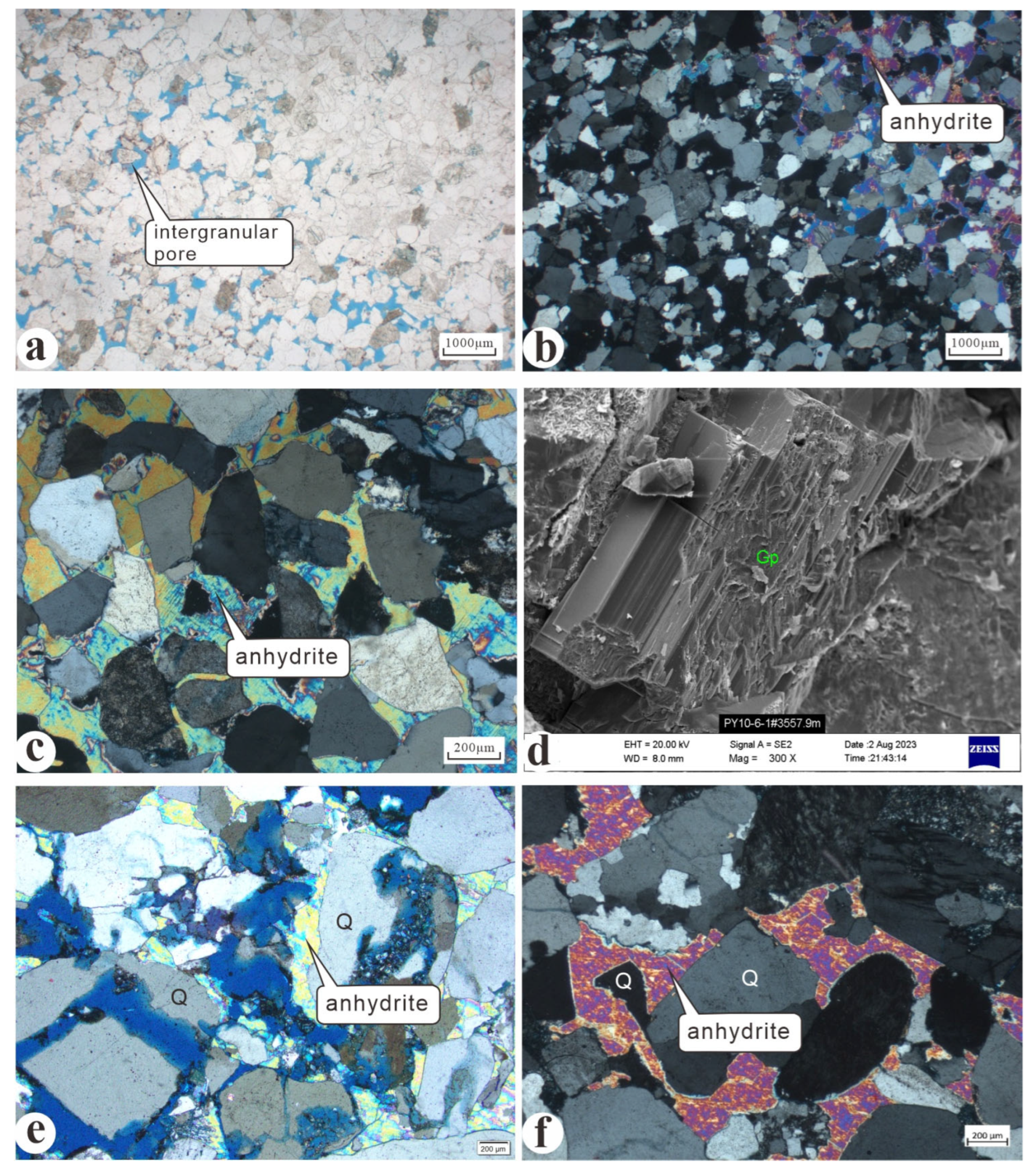

4.2. Calcareous Cement Types and Characteristics

4.2.1. Dolomite

4.2.2. Ankerite

4.2.3. Anhydrite

4.3. Geochemical Characteristics

4.3.1. Major Elements

4.3.2. Trace Elements

4.3.3. Carbon and Oxygen Isotope Data

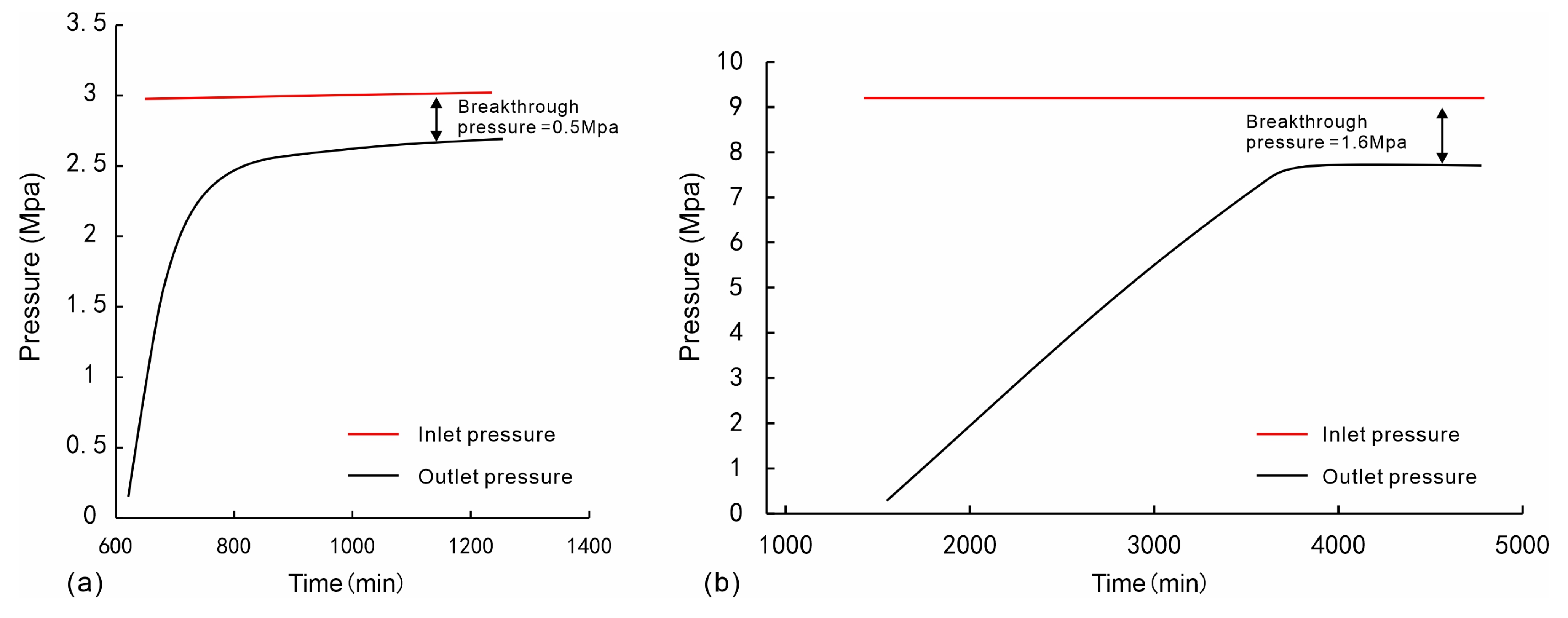

4.4. Displacement Pressure and Breakthrough Pressure

5. Discussion

5.1. Genetic Mechanisms and Development Models of Calcareous Sandstones

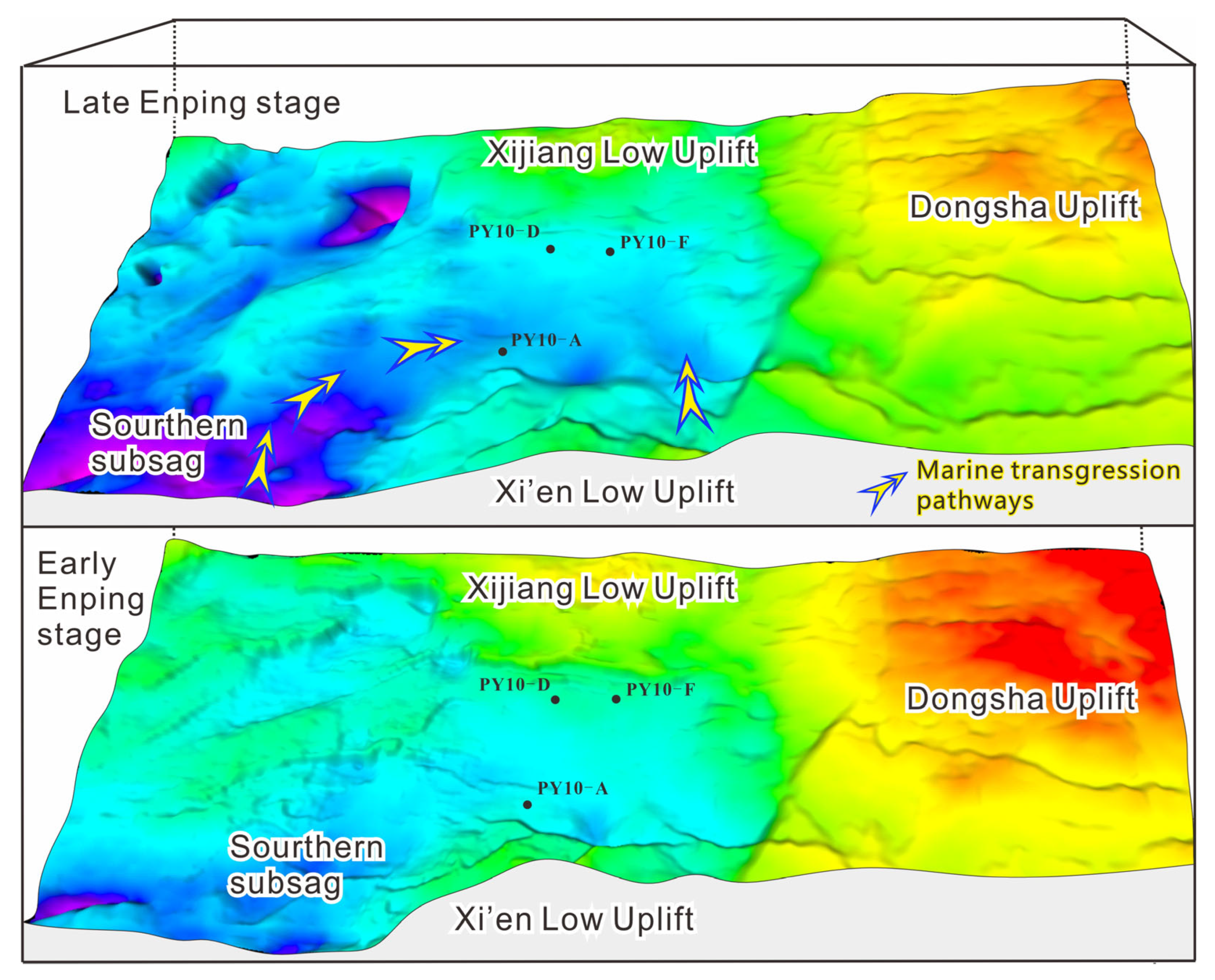

5.1.1. Local Marine Transgressions

5.1.2. Burial Diagenesis

Controls of Burial Diagenesis on Dolomite/Ankerite Cementation

Controls of Burial Diagenesis on Gypsum/Anhydrite Dolomite Cementation

5.2. Development Model of Calcareous Sandstones

5.3. Sealing Mechanisms of Calcareous Sandstones

5.3.1. Sealing Mechanism and Effectiveness Evaluation of Calcareous Sandstones

5.3.2. Development Model of Hydrocarbon Accumulation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPL | Plane-polarized light |

| XPL | Cross-polarized light |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| MD | Micritic dolomite |

| S-FD | Silt-to-fine-crystalline dolomite |

| CCD | Coarse-crystalline dolomite |

| An | Ankerite |

| Gp | Gypsum |

References

- Liao, M.G.; Huang, Z.Q.; Liang, W.F.; Liao, J.J. Geological Characteristics and Genesis Analysis of Calcareous Intercalation Layer of Oil Group A in N Oilfield. Sediment. Geol. Tethyan Geol. 2020, 40, 26–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shang, F.K.; Zhang, K.H.; Shi, H.G.; Xu, Y.D.; Zhang, Y.J.; Chen, L. “Ternary composite” genesis and petroleum geological significance of calcareous barriers in the 1st sand group of Shawan-1 member of Neogene in the Chepaizi bulge of the Junggar Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2020, 25, 112–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C.D. Possible links between sandstone diagenesis and depth-related geochemical reactions occurring in enclosing mudstones. J. Geol. Soc. 1978, 135, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surdam, R.C.; Crossey, L.J.; Hagen, E.S.; Heasler, H.P. Organic-Inorganic Interactions and Sandstone Diagenesis. AAPG Bull. 1989, 73, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J.; Shi, H.; Mao, X.D.; Zhang, M.; Shen, L.C.; Wu, W.H. Diagenetic alteration of earlier palaeozoic marine carbonate and preservation for the information of seawater. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2003, 30, 9–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D.A.; Lundgren, C.E.; Longman, M.W. Sedimentology and Diagenesis of the St. Peter Sandstone, Central Michigan Basin, United States. AAPG Bull. 1992, 76, 1507–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.G.; Macquaker, J.H.S. Early diagenetic pyrite morphology in a mudstone-dominated succession: The Lower Jurassic Cleveland Ironstone Formation, eastern England. Sediment. Geol. 2000, 131, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, F.L. Mineral/Water Interaction, Fluid Flow, and Frio Sandstone Diagenesis: Evidence from the Rocks. AAPG Bull. 1997, 80, 486–504. [Google Scholar]

- Rlykke, K.O.B.O. Fluid-flow processes and diagenesis in sedimentary basins. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1994, 78, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.F.; Jiang, W.; Wu, K.J.; Wang, H.; Xu, T.K.; Chen, S.J.; Ran, T. Sedimentation mechanism and petroleum significance of calcareous cements in continental clastic rocks: Comparison between the Kongdian Formation in the Jiyang Depression and the Xujiahe Formation in the western Sichuan Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2016, 38, 293–302. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.N.; Deng, L.L.; Gong, Y.C.; Sun, W. Carbonate cement from Xujiahe Sandstone and its forming mechanism, West Sichuan Depression. Nat. Gas Technol. 2008, 2, 24–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Pang, J.; Yang, Y.T.; Cao, Y.H.; Qi, M.H.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, S. Carbon and Oxygen isotope characteristics and genesis of carbonate cements in sandstone of the 4th Member of the Xujiahe Formation in the central western Sichuan depression, Sichuan basin, China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2022, 96, 2094–2106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, A.H.; Noble, J.A. Origin, distribution and significance of carbonate cements in the Albert Formation reservoir sandstones, New Brunswick, Canada. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1996, 13, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.Y.; Kominz, M.; Reuning, L.; Gallagher, S.J.; Takayanagi, H.; Ishiwa, T.; Knierzinger, W.; Wagreich, M. Quantitative compaction trends of Miocene to Holocene carbonates off the west coast of Australia. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 68, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.F.; Liu, Z.B.; Li, Y.P.; Wen, J.T.; Wang, T. Genetic mechanism and controlling factors of calcareous sandstone of the Paleogene Shahejie Formation, Liaodong Gulf. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2018, 25, 65–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.L.; Shang, J.X.; Fu, T.; Ye, Q.; Kong, L.H. Influence research of calcareous intercalation on development effect in oil group ZJ1-5of Wenchang oilfield. Pet. Geol. Eng. 2015, 29, 73–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Yang, C.Q.; Huang, G.Z.; Li, M.W. Study on Development Pattern of Zhujiang Formation Calcareous Sandstone in Wenchang Oilfield Group. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2014, 21, 14–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- You, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.Z. Distribution and Genetic Mechanism of Carbonate Cements in the Zhuhai Formation Reservoirs in Wenchang A Sag, Pear River Mouth Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2012, 33, 883–889. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.Q.; Yao, G.Q.; Yang, X.H. Constraints of Authigenic Clay Minerals on Deep Reservoirs in Wenchang A Sag. Earth Sci. 2019, 44, 909–918. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.Y.; Chen, D.X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, F.W. Preservation mechanism and model of primary pore diagenesis in deep reservoirs: Taking the Enping Formation and Wenchang Formation in the south of Huizhou Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin as example. J. Northeast Pet. Univ. 2022, 46, 72–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.G.; Gao, Y.D.; Liu, J.; Peng, G.R.; Qiu, X.W.; Zhang, X.Z.; Jia, P.M. Major discoveries and significance of hydrocarbon exploration in the Paleogene reservoirs of Panyu A subsag, Xijiang sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2024, 45, 1031–1043. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, G.; Liu, P.; Song, P.; Gao, X.; Xiong, W.; Xiang, Q.; Han, B. Source rock attribute, oil classification and hydrocarbon accumulation main control factors of Xijiang main sag in Pearl River mouth Basin. Earth Sci. 2023, 48, 2361–2375. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Sun, Z.; Qiu, N.; Zhao, M.H.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, F.C.; Lin, J.; Lee, E.Y. The paleo-lithospheric structure and rifting-magmatic processes of the northern South China Sea passive margin. Gondwana Res. 2023, 120, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.S.; Shu, Y.; Du, J.Y. Petroleum Geology of Paleogene in Pearl River Mouth Basin; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pang, X.; Chen, C.M.; Shao, L.; Wang, C.S.; Zhu, M. Baiyun Movement, a great tectonic event on the Oligocene-Miocene boundary in the northern South China Sea and its implications. Geol. Rev. 2007, 53, 145–151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.S.; Du, J.Y.; Mei, L.F.; Zhang, X.T.; Hao, S.H.; Liu, P.; Deng, P.; Zhang, Q. Huizhou movement and its significance in Pearl River Mouth Basin, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 447–461. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.D.; Liu, J.; Peng, G.R.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Shi, Y.L. New fields and resource potential of oil and gas exploration in Pearl River Mouth Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2024, 45, 183–201. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.P.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, Z.H. Cenozoic faults characteristics and regional dynamic background of Panyu 4 sub-sag, Zhu I Depression. J. China Univ. Pet. 2015, 39, 1–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.W.; Zhu, H.T.; Yang, X.H.; Xia, C.C.; Chen, Y.; Han, Y.C. Provenance transformation and sedimentary evolution of Enping Formation, Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Earth Sci. 2017, 42, 1936–1954. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.W.; Liu, J.; Liu, L.H.; Zhang, X.Z.; Bai, H.J.; Yang, D.F. Lithology prediction technology and its application of Paleogene Wenchang Formation in Panyu 4 Depression, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Lithol. Reserv. 2022, 34, 118–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.J. Diagenesis of Carbonate Rocks; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. Research on Petrological Characteristics and Diagenesis of the Lower Triassic Jialingjiang Formation in Libi Gorge of Chongqing Area, Eastern Sichuan Basin. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.G. Dolomite Crystal Architecture: Genetic Implications for the Origin of the Tertiary Dolostones of the Cayman Islands. J. Sediment. Res. 2005, 75, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, E.H.; Grice, J.D. The IMA Commission on new minerals and mineral names: Procedures and guidelines on mineral nomenclature. Mineral. Petrol. 1998, 64, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.L.; Jia, W.Q.; Xu, F.; Liu, Y. Mineralogical characteristics of ankerite and mechanisms of primary and secondary origins. Earth Sci. 2018, 43, 4046–4055. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.D. Favorable Main Controlling Factors of Paleogene Wenchang Formation in the Southwest of Huizhou Sag of Zhuyi Depression. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q. Late Cainozoic ostracod faunas and paleoenvironmental changes at ODP Site 1148, South China Sea. Mar. Micropaleontol. 2005, 54, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.X.; Jiang, Z.M.; Zhao, Q.H.; Li, Q.Y.; Wang, R.J. Deep-sea evidence for the evolution and monsoon history of the South China Sea. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2003, 48, 2228–2239. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.M.; Wu, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.Y.; Liu, Z.; Dai, L.M.; Li, J.W.; Li, L.B. Changes of paleocoastline in key geological periods in the South China Sea. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2013, 33, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.C. Theory of deepwater hydrocarbon accumulation controlled by progressive tectonic cycles of the marginal sea in the South China Sea. Acta Pet. Sin. 2023, 44, 569–582. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.D.; Xiang, X.H.; Zhang, X.T. Cenozoic sedimentary evolution and its geological significance for hydrocarbon exploration in the northern South China Sea. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2021, 32, 645–656. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.A.; Allen, J.R. Basin Analysis Principle and Application; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Qi, J.F. Method of delaminated decompaction correction. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2003, 25, 206–210. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L. Genesis of the glauconites in the Miocene Zhujiang Formation, Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.K.; Xie, L.; Zhang, Y.F.; Xu, J.; Li, S.H.; Wang, Y. Sedimentary records of the Mis 3 transgression event in the north Jiangsu Plain, China. Quat. Sci. 2010, 30, 883–891. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, W.J.; Liang, X.J.; Zhang, Y.Y. Geochemical characteristics of Quaternary sediments of typical borehole XJ01 in ancient Yellow River Delta. Miner. Explor. 2024, 15, 938–945. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.; Mamming, D.A.C. Comparison of geochemical indices used for the interpretation of depositional environments in ancient mudstones. Chem. Geol. 1994, 111, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Guo, W.Y.; Zhang, G.D. Application of some geochemical indicators in determining of sedimentary environment of the Paleogene Funing Group, Jinhu Depression, Jiangsu Province. J. Tongji Univ. 1979, 7, 51–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.G.; Xie, Z.Q.; Zhao, J.L. The characteristics of Sr/Ba and B/Ga ratios in lake sediments on the Ardley Peninsula, Maritime Antarctic. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2000, 20, 43–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kimura, Y.; Puchala, B. Dissolution enables dolomite crystal growth near ambient conditions. Science 2023, 382, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Ma, Y.F.; Yao, Q.Z.; Qian, F.J.; Wang, Y.H.; Li, H.; Zhou, G.T. “Dolomite Problem”and Experimental Studies of Dolomite Formation. Geol. J. China Univ. 2015, 21, 395–406. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.L.; Liu, C.H.; Yang, W.Q.; Zhu, D.C.; Yu, Y.M.; Chen, F.Z.; Zou, H.Y. Characteristics and genesis of thick layer dolomites in the Lower Cambrian Xixiangchi Group, eastern Sichuan Basin. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2024, 31, 599–610. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, Z.T. Carbonate Reservoir Geology; Press of the University of Petroleum: Dongying, China, 1998. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Zhong, D.K.; Gao, C.L.; Yang, X.Q.; Xie, R.; Li, Z.P.; Deng, M.X.; Zhou, Y.C. Geochemical characteristics, genesis and hydrocarbon significance of dolomite in the Cambrian Longwangmiao Formation, eastern Sicuhan Basin. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 37, 1102–1115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, F.L.; Ji, Y.L.; Zhou, X.F.; Zhang, C.H. Characteristics and controlling factors of dolomite karst reservoirs of the Sinian Dengying Formation, central Sichuan Basin, southwestern China. Precambrian Res. 2020, 343, 105708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M.L.; Weber, J.N. Carbon and oxygen isotopic composition of selected limestones and fossils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1964, 28, 1787–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, H.; Curtis, C.; Coleman, M. Isotopic evidence for source of diagenetic carbonates formed during burial of organic-rich sediments. Nature 1977, 269, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L. Relationship between carbon and oxygen stable isotope in carbonate rocks and paleosalinity and paleotemperature of seawater. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 1985, 3, 17–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.J.; Wu, W.H.; Liu, J.; Shen, L.C.; Huang, C.G. Generation of secondary porosity by meteoric water during time of subaerial exposure: An example from Yanchang Formation Sandstone of Triassic of Ordos Basin. Earth Sci. 2003, 28, 419–424. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.L. Characteristics and diagenetic significance of carbon and oxygen isotopes in the authigenic dolomites of lacustrine carbonate rocks—A case study of the Paleogene Shahejie Formation of the Shijiutuo Uplift in Bohai Sea. Adv. Geosci. 2017, 7, 847–855. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.M.; Shi, Z.J.; Li, T.Y.; Liang, X.W.; Xin, H.G.; Wu, X.M.; Gao, X. Characteristics and origin of the carbonate cement of Chang 8 member in Jiyuan area, Ordos Basin. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 26, 26–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Meshri, I.D.; Gautier, D.L. On the Reactivity of Carbonic and Organic Acids and Generation of Secondary Porosity; SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology: Claremore, OK, USA, 1985; pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.M.; Lu, B. Study on carbonate cements in siliceous clastic rocks and their controlling effect on reservoirs. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 1994, 12, 56–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Hou, Y.D.; Sun, J.F.; He, W.X.; Gao, X.Y.; Si, J.; Song, W.X. Geochemical characteristics of trace elements in Yanghugou formation in the western margin of Ordos Basin and their implications for the sedimentary environment. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 11999–12009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Sheng, W.Z.; Zheng, L.D. Elements and isotopic geochemistry of Guadalupian-Lopingian boundary profile at the Penglaitan section of Laibin, Guangxi Province, and its Geological implications. Acta Geol. Sin. 2009, 83, 1–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nan, J.Y.; Ye, J.L.; Wang, Z.M.; Zhou, D.Q. Geochemical study of Permian-Triassic paleoclimate and paleo-marine environment in Guizhou. Acta Mineral. Sin. 1998, 18, 239–249. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Downey, M.W. Evaluating seals for hydrocarbon accumulations. AAPG Bull. 1984, 68, 1752–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.L. Theoretical aspects of cap-rock and fault seals for single-and two-phase hydrocarbon columns. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1987, 4, 274–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.F.; Wu, T.; Lv, Y.F.; Liu, S.B.; Tian, H.; Lu, M.X. Research status and development trend of the reservoir caprock sealing properties. Oil Gas Geol. 2018, 39, 454–471. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.D. Caprock Sealing Quantitative Evaluation of Low Abundance of Gas Accumulation. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China, 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

| Strata | Depth (m) | Al2O3 /% | CaO /% | Fe2O3 /% | K2O /% | MgO /% | MnO /% | Na2O /% | P2O5 /% | TiO2 /% | SiO2 /% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3z1 | 3005 | 11.9 | 0.93 | 4.60 | 2.66 | 1.29 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 72.7 |

| 3055 | 11.9 | 0.28 | 5.11 | 2.64 | 1.20 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.75 | 71.8 | |

| 3115 | 9.70 | 0.54 | 3.02 | 2.58 | 1.09 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 78.4 | |

| 3150 | 14.8 | 0.20 | 4.73 | 3.11 | 1.55 | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 68.3 | |

| 3195 | 9.85 | 0.50 | 3.43 | 2.52 | 1.19 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 77.4 | |

| E3z2 | 3270 | 12.9 | 0.50 | 4.49 | 3.17 | 1.67 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.13 | 0.70 | 71.7 |

| 3310 | 7.84 | 0.62 | 3.28 | 2.66 | 1.08 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 80.2 | |

| 3375 | 8.51 | 0.44 | 2.20 | 3.02 | 1.02 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 80.3 | |

| 3405 | 10.7 | 1.39 | 3.02 | 3.33 | 1.41 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 74.4 | |

| E3z3 | 3440 | 10.6 | 0.69 | 3.77 | 3.10 | 1.74 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 75.0 |

| 3470 | 6.34 | 2.07 | 2.00 | 2.83 | 1.50 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 80.5 | |

| 3505 | 5.84 | 5.49 | 3.46 | 2.72 | 3.41 | 0.26 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 68.7 | |

| 3525 | 7.08 | 5.47 | 4.89 | 2.61 | 3.59 | 0.24 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 67.3 | |

| 3535 | 7.34 | 0.47 | 2.47 | 2.90 | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 81.3 | |

| 3560 | 11.9 | 0.76 | 4.24 | 3.06 | 1.92 | 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 72.3 | |

| 3565 | 8.64 | 0.38 | 3.30 | 3.07 | 1.21 | 0.02 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 78.7 | |

| 3580 | 5.86 | 0.32 | 1.50 | 2.60 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 86.0 | |

| 3640 | 6.30 | 2.45 | 1.79 | 3.18 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 82.7 | |

| 3645 | 17.9 | 0.18 | 4.26 | 3.83 | 1.80 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 65.4 | |

| E2e1 | 3685 | 6.53 | 6.49 | 5.13 | 2.79 | 4.06 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 64.1 |

| 3690 | 5.71 | 6.14 | 5.76 | 2.49 | 3.93 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 69.3 | |

| 3700 | 5.70 | 8.34 | 4.71 | 2.41 | 4.53 | 0.44 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 64.4 | |

| 3705 | 6.05 | 8.58 | 6.70 | 2.49 | 4.37 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 62.0 | |

| 3715 | 7.24 | 0.52 | 3.73 | 2.57 | 1.22 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 81.1 | |

| 3720 | 9.75 | 0.63 | 5.23 | 3.11 | 1.57 | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 76.2 | |

| 3730 | 5.50 | 6.31 | 5.13 | 2.40 | 3.49 | 0.51 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 72.4 | |

| 3750 | 6.62 | 1.32 | 2.25 | 2.74 | 1.24 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 79.8 | |

| 3760 | 10.6 | 0.40 | 3.43 | 3.17 | 1.38 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 76.2 | |

| 3785 | 9.22 | 0.24 | 1.75 | 3.58 | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 79.8 | |

| E2e2 | 3925 | 6.08 | 3.28 | 1.88 | 3.07 | 1.87 | 0.12 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 77.6 |

| 3945 | 5.07 | 3.54 | 1.66 | 2.38 | 1.68 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 79.9 |

| Strata | Depth (m) | V/ ppm | Ni/ ppm | Cu/ ppm | Ga/ ppm | Rb/ ppm | Sr/ ppm | Y/ ppm | Zr/ ppm | Ba/ ppm | B/ ppm | Sr/Cu | Sr/Ba | B/Ga | V/(V + Ni) | Zr/Y | Rb/Zr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3z1 | 3005 | 56.0 | 18.8 | 22.0 | 12.9 | 122.6 | 91 | 28.6 | 257 | 8052 | 52.5 | 4.145 | 0.011 | 4.061 | 0.749 | 8.994 | 0.476 |

| 3055 | 56.9 | 16.9 | 20.1 | 13.4 | 125 | 80 | 31.3 | 261 | 8117 | 49.9 | 3.970 | 0.010 | 3.723 | 0.771 | 8.331 | 0.477 | |

| 3115 | 45.0 | 14.4 | 16.0 | 10.6 | 120 | 86 | 26.4 | 239 | 11,416 | 39.7 | 5.372 | 0.008 | 3.748 | 0.757 | 9.046 | 0.501 | |

| 3150 | 61.8 | 20.8 | 24.1 | 15.94 | 149.3 | 78 | 33.8 | 266 | 5708 | 65.2 | 3.243 | 0.014 | 4.089 | 0.748 | 7.853 | 0.562 | |

| 3195 | 46.6 | 14.9 | 15.9 | 10.58 | 115.0 | 68 | 24.0 | 245 | 6171 | 54.6 | 4.291 | 0.011 | 5.158 | 0.758 | 10.205 | 0.470 | |

| E3z2 | 3270 | 55.6 | 19.4 | 17.4 | 13.16 | 139.8 | 76 | 30.7 | 247 | 5283 | 65.1 | 4.374 | 0.014 | 4.946 | 0.741 | 8.020 | 0.567 |

| 3310 | 36.1 | 15.4 | 15.3 | 8.10 | 114.5 | 77.9 | 21.5 | 216 | 10,101 | 37 | 5.103 | 0.008 | 4.504 | 0.701 | 10.068 | 0.530 | |

| 3375 | 35.3 | 13.9 | 13.0 | 8.36 | 120.8 | 84 | 21.2 | 210 | 11,342 | 39.6 | 6.510 | 0.007 | 4.738 | 0.717 | 9.921 | 0.575 | |

| 3405 | 43.4 | 17.7 | 14.8 | 10.72 | 141.7 | 116 | 21.0 | 228 | 9860 | 36.2 | 7.843 | 0.012 | 3.373 | 0.710 | 10.847 | 0.621 | |

| E3z3 | 3440 | 46.6 | 17.0 | 13.8 | 11.0 | 139 | 77 | 23.8 | 227 | 7870 | 53.6 | 5.567 | 0.010 | 4.877 | 0.733 | 9.538 | 0.612 |

| 3470 | 26.9 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 6.1 | 115 | 94 | 16.4 | 187 | 8217 | 15.8 | 9.077 | 0.011 | 2.583 | 0.706 | 11.420 | 0.615 | |

| 3505 | 30.1 | 12.6 | 13.7 | 5.6 | 105 | 68 | 19.2 | 179 | 6709 | 16.3 | 4.994 | 0.010 | 2.932 | 0.705 | 9.340 | 0.586 | |

| 3525 | 42.7 | 20.3 | 11.9 | 7.2 | 106 | 70 | 24.2 | 211 | 6725 | 21.9 | 5.899 | 0.010 | 3.028 | 0.678 | 8.731 | 0.501 | |

| 3535 | 30.8 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 7.4 | 120 | 74 | 19.2 | 199 | 9603 | 28.8 | 6.283 | 0.008 | 3.896 | 0.717 | 10.415 | 0.603 | |

| 3560 | 49.9 | 17.2 | 17.7 | 12.0 | 132 | 69 | 28.6 | 259 | 4797 | 70.5 | 3.877 | 0.014 | 5.894 | 0.744 | 9.048 | 0.509 | |

| 3565 | 36.1 | 13.9 | 12.6 | 8.50 | 122.7 | 75 | 23.7 | 217 | 9414 | 25.8 | 5.925 | 0.008 | 3.033 | 0.723 | 9.132 | 0.566 | |

| 3580 | 24.7 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 5.7 | 111 | 66 | 14.7 | 189 | 6808 | 25.2 | 7.243 | 0.010 | 4.422 | 0.734 | 12.848 | 0.586 | |

| 3640 | 21.4 | 6.6 | 31.1 | 5.34 | 114.3 | 157.7 | 12.4 | 172 | 6354 | 9.3 | 5.066 | 0.025 | 1.741 | 0.763 | 13.823 | 0.666 | |

| 3645 | 65.4 | 20.1 | 23.7 | 18.3 | 171 | 76 | 35.9 | 260 | 4496 | 60.3 | 3.208 | 0.017 | 3.300 | 0.765 | 7.252 | 0.655 | |

| E2e1 | 3685 | 35.9 | 13.2 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 104 | 75.5 | 19.8 | 199 | 6309 | 14.3 | 7.646 | 0.012 | 2.218 | 0.731 | 10.027 | 0.524 |

| 3690 | 44.5 | 14.5 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 91 | 73.4 | 21.5 | 184 | 6761 | 12.0 | 8.559 | 0.011 | 2.063 | 0.755 | 8.555 | 0.493 | |

| 3700- | 30.8 | 11.0 | 9.3 | 5.4 | 89 | 82.1 | 21.1 | 199 | 7759 | 12.8 | 8.798 | 0.011 | 2.389 | 0.737 | 9.416 | 0.445 | |

| 3705 | 38.1 | 14.3 | 14.9 | 6.0 | 89 | 77.1 | 24.7 | 195 | 6123 | 14.4 | 5.193 | 0.013 | 2.415 | 0.727 | 7.888 | 0.456 | |

| 3715 | 32.3 | 10.6 | 15.2 | 7.2 | 95 | 63.4 | 25.5 | 260 | 6699 | 38.1 | 4.175 | 0.009 | 5.324 | 0.753 | 10.199 | 0.365 | |

| 3720 | 46.2 | 17.6 | 14.1 | 9.6 | 120 | 68.3 | 27.7 | 257 | 5868 | 45.2 | 4.850 | 0.012 | 4.719 | 0.724 | 9.288 | 0.465 | |

| 3730 | 37.3 | 12.4 | 8.9 | 5.5 | 89 | 65.9 | 17.7 | 208 | 5586 | 18.0 | 7.374 | 0.012 | 3.248 | 0.750 | 11.720 | 0.429 | |

| 3750 | 34.1 | 11.5 | 13.6 | 6.7 | 96 | 119.3 | 21.7 | 289 | 25,202 | 27.1 | 8.752 | 0.005 | 4.039 | 0.748 | 13.350 | 0.332 | |

| 3760 | 42.1 | 14.9 | 14.5 | 10.3 | 115 | 83.6 | 27.0 | 288 | 11,374 | 56.1 | 5.764 | 0.007 | 5.441 | 0.739 | 10.681 | 0.400 | |

| 3785 | 30.5 | 9.5 | 11.4 | 8.5 | 117 | 98.3 | 20.7 | 243 | 9907 | 27.8 | 8.595 | 0.010 | 3.273 | 0.762 | 11.761 | 0.482 | |

| E2e2 | 3925 | 22.7 | 5.9 | 9.3 | 5.4 | 93 | 127.0 | 12.0 | 176 | 16,288 | 9.4 | 13.589 | 0.008 | 1.745 | 0.794 | 14.685 | 0.531 |

| 3945 | 23.7 | 27.2 | 37.6 | 4.6 | 78.7 | 126 | 11.6 | 173 | 16,400 | 13.4 | 3.365 | 0.008 | 2.920 | 0.465 | 14.897 | 0.455 |

| Strata | Depth (m) | V/ ppm | Ni/ ppm | Cu/ ppm | Ga/ ppm | Rb/ ppm | Sr/ ppm | Y/ ppm | Zr/ ppm | Ba/ ppm | B/ ppm | Sr/Cu | Sr/Ba | B/Ga | V/(V + Ni) | Zr/Y | Rb/Zr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3z1 | 2986 | 29.8 | 9.9 | 56.3 | 4.3 | 71 | 147 | 9.2 | 162 | 44,603 | 26.4 | 2.609 | 0.003 | 6.098 | 0.750 | 17.536 | 0.442 |

| 3097 | 32.6 | 8.9 | 58.9 | 3.9 | 76 | 175 | 11.3 | 151 | 59,735 | 17.3 | 2.970 | 0.003 | 4.460 | 0.786 | 13.284 | 0.506 | |

| E3z2 | 3193 | 38.5 | 12.4 | 61.3 | 6.48 | 103.5 | 164 | 13.8 | 189 | 52,937 | 36.8 | 2.673 | 0.003 | 5.675 | 0.756 | 13.706 | 0.548 |

| 3199 | 29.3 | 7.7 | 55.2 | 3.38 | 69.5 | 155 | 7.8 | 157 | 52,158 | 23.4 | 2.819 | 0.003 | 6.919 | 0.791 | 20.029 | 0.443 | |

| 3322 | 38.3 | 11.5 | 49.9 | 7.60 | 130.5 | 127 | 16.8 | 194 | 33,087 | 48.7 | 2.550 | 0.004 | 6.412 | 0.769 | 11.541 | 0.671 | |

| E3z3 | 3457 | 37.1 | 11.6 | 59.1 | 6.43 | 113.5 | 186.6 | 13.6 | 175 | 47,535 | 41 | 3.157 | 0.004 | 6.333 | 0.762 | 12.865 | 0.646 |

| 3472 | 32.2 | 9.5 | 53.6 | 5.67 | 110.8 | 152 | 12.5 | 170 | 47,758 | 22.5 | 2.839 | 0.003 | 3.961 | 0.772 | 13.618 | 0.652 | |

| E2e1 | 3547 | 30.1 | 9.7 | 48.8 | 6.50 | 133.2 | 282 | 14.0 | 193 | 22,647 | 23.2 | 5.773 | 0.012 | 3.567 | 0.756 | 13.784 | 0.691 |

| 3598 | 41.4 | 13.2 | 60.7 | 6.6 | 112 | 174 | 18.2 | 169 | 23,718 | 15.5 | 2.873 | 0.007 | 2.358 | 0.758 | 9.279 | 0.666 | |

| 3601 | 38.8 | 13.4 | 50.5 | 5.2 | 90 | 146 | 16.1 | 156 | 31,291 | 19.3 | 2.886 | 0.005 | 3.716 | 0.743 | 9.651 | 0.579 | |

| 3640 | 38.5 | 12.3 | 43.5 | 5.2 | 93 | 162 | 15.0 | 163 | 37,715 | 17.7 | 3.722 | 0.004 | 3.422 | 0.758 | 10.899 | 0.571 | |

| 3649 | 31.3 | 10.4 | 44.7 | 4.7 | 94 | 219 | 15.5 | 153 | 35,644 | 13.0 | 4.896 | 0.006 | 2.796 | 0.751 | 9.846 | 0.616 | |

| 3652 | 32.6 | 9.8 | 35.1 | 5.8 | 116 | 133 | 13.9 | 170 | 10,376 | 19.4 | 3.791 | 0.013 | 3.356 | 0.769 | 12.235 | 0.681 | |

| 3658 | 38.1 | 12.1 | 45.5 | 6.3 | 109 | 144 | 20.7 | 225 | 33,070 | 29.4 | 3.168 | 0.004 | 4.653 | 0.759 | 10.893 | 0.486 | |

| 3694 | 39.7 | 15.3 | 45.9 | 8.78 | 144.9 | 106 | 23.8 | 193 | 9324 | 26.2 | 2.302 | 0.011 | 2.983 | 0.722 | 8.101 | 0.752 | |

| 3700 | 31.2 | 8.7 | 37.3 | 6.5 | 114 | 96 | 15.6 | 184 | 15,786 | 27.1 | 2.562 | 0.006 | 4.191 | 0.781 | 11.802 | 0.619 | |

| E2e2 | 3988 | 54.8 | 11.3 | 48.9 | 14.78 | 169.7 | 142.8 | 26.0 | 239 | 23,063 | 21.9 | 2.921 | 0.006 | 1.482 | 0.829 | 9.164 | 0.711 |

| 4024 | 24.0 | 6.0 | 51.0 | 5.9 | 102 | 263 | 8.9 | 154 | 22,233 | 11.2 | 5.158 | 0.012 | 1.893 | 0.801 | 17.308 | 0.662 |

| Strata | Depth (m) | Measured Point | Cement Types | δ13CPDB (‰) | δ18OPDB (‰) | δ18OSMOW (‰) | Z | Paleo-Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3z | 3518 | 1 | CCD | −11.94 | −9.16 | 21.44 | 98.32 | 87.90 |

| 2 | S-FD | −14.38 | −7.28 | 23.36 | 94.22 | 72.64 | ||

| 3 | CCD | −12.12 | −9.52 | 21.06 | 97.72 | 91.14 | ||

| 3565.3 | 1 | CCD | −17.62 | −2.64 | 28.14 | 89.94 | 41.98 | |

| 2 | S-FD | −14.56 | −6.92 | 23.74 | 94.06 | 69.88 | ||

| 3 | S-FD | −10.98 | −6.78 | 23.88 | 101.48 | 68.84 | ||

| 4 | MD | −22.01 | −3.20 | 27.58 | 80.64 | 45.20 | ||

| E2e | 3695.5 | 1 | S-FD | −12.82 | −6.50 | 24.16 | 97.84 | 66.86 |

| 2 | S-FD | −11.76 | −7.24 | 23.40 | 99.62 | 72.34 | ||

| 3703.5 | 1 | MD | −11.74 | −3.78 | 26.98 | 101.40 | 48.72 | |

| 2 | MD | −11.86 | −4.24 | 26.50 | 100.90 | 51.60 | ||

| 3 | MD | −12.70 | −4.04 | 26.70 | 99.28 | 50.36 | ||

| 4 | Ank | −13.26 | −10.02 | 20.53 | 95.18 | 95.72 | ||

| 3731.8 | 1 | S-FD | −15.30 | −6.71 | 23.94 | 92.62 | 68.44 | |

| 2 | S-FD | −15.38 | −5.62 | 25.08 | 93.02 | 60.66 | ||

| 3755.8 | 1 | MD | −16.72 | −2.72 | 28.06 | 91.72 | 42.40 | |

| 2 | MD | −21.42 | −2.26 | 28.54 | 82.32 | 39.76 | ||

| 3 | MD | −20.54 | −2.66 | 28.14 | 83.94 | 42.06 | ||

| 4 | MD | −16.98 | −3.28 | 27.50 | 90.92 | 45.68 |

| Strata | Well Name | Depth (m) | δ13CPDB (‰) | δ18OPDB (‰) | δ18OSMOW (‰) | Z | Paleo-Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3z | PY10F | 3371.6 | −9.98 | −12.4 | 18.08 | 100.69 | 120.07 |

| PY10A | 3530 | −9.98 | −12.88 | 17.58 | 100.45 | 125.56 | |

| PY10A | 3418.5 | −10.61 | −12.76 | 17.71 | 99.22 | 124.20 | |

| PY10A | 3424.17 | −10.11 | −13.1 | 17.36 | 100.07 | 128.21 | |

| E2e | PY10A | 3686 | −11.41 | −8.66 | 21.93 | 99.62 | 83.72 |

| PY10A | 3710.3 | −11.01 | −10.4 | 20.14 | 99.57 | 99.31 | |

| PY10D | 3604 | −10.14 | −10.94 | 19.58 | 101.09 | 104.57 | |

| PY10 D | 3631.47 | −10.94 | −8.15 | 22.46 | 100.84 | 79.52 | |

| PY10 D | 3796.44 | −9.79 | −8.26 | 22.35 | 103.14 | 80.41 | |

| PY10 D | 3798.39 | −9.75 | −8.36 | 22.24 | 103.17 | 81.23 | |

| PY10 D | 3799.13 | −10.1 | −9.24 | 21.34 | 102.01 | 88.70 |

| Well Name | Depth (m) | Lithology | Porosity (%) | Permeability (mD) | Displacement Pressure (MPa) | Ave. Displacement Pressure (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY10-A | 3530 | Calcareous sandstone | 8.371 | 0.263 | 0.842 | 1.013 |

| 3686 | Calcareous sandstone | 4.828 | 0.0431 | 1.417 | ||

| PY10-D | 3604 | Calcareous sandstone | 9.992 | 0.127 | 0.779 | |

| PY10-A | 3710.3 | Sandstone reservoirs | 10.9 | 2.56 | 0.163 | 0.275 |

| 3671.80 | Sandstone reservoirs | 14.5 | 4.69 | 0.749 | ||

| 3690.93 | Sandstone reservoirs | 9.5 | 3.26 | 0.901 | ||

| 3712.94 | Sandstone reservoirs | 19.4 | 14.7 | 0.242 | ||

| 3726.00 | Sandstone reservoirs | 14.2 | / | 0.040 | ||

| 3738.00 | Sandstone reservoirs | 17.1 | 30.7 | 0.174 | ||

| 3758.13 | Sandstone reservoirs | 13.3 | 20.6 | 0.187 | ||

| 3788.93 | Sandstone reservoirs | 10.9 | 9.77 | 0.330 | ||

| 3795.17 | Sandstone reservoirs | 14.9 | 837 | 0.035 | ||

| 3798.93 | Sandstone reservoirs | 12.5 | 117 | 0.091 | ||

| 3844.00 | Sandstone reservoirs | 11.3 | 67.7 | 0.114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Peng, G.; Zhang, W.; Qiu, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, K.; Que, X.; Jia, P. Genetic and Sealing Mechanisms of Calcareous Sandstones in the Paleogene Zhuhai–Enping Formations, Panyu A Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121285

Zhou Y, Peng G, Zhang W, Qiu X, Li Z, Wang K, Que X, Jia P. Genetic and Sealing Mechanisms of Calcareous Sandstones in the Paleogene Zhuhai–Enping Formations, Panyu A Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121285

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yong, Guangrong Peng, Wenchi Zhang, Xinwei Qiu, Zhensheng Li, Ke Wang, Xiaoming Que, and Peimeng Jia. 2025. "Genetic and Sealing Mechanisms of Calcareous Sandstones in the Paleogene Zhuhai–Enping Formations, Panyu A Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121285

APA StyleZhou, Y., Peng, G., Zhang, W., Qiu, X., Li, Z., Wang, K., Que, X., & Jia, P. (2025). Genetic and Sealing Mechanisms of Calcareous Sandstones in the Paleogene Zhuhai–Enping Formations, Panyu A Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Minerals, 15(12), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121285