Abstract

Sulfide geochemistry has been widely employed to constrain formation processes in various deposit types; however, its use in porphyry W-Mo metallogenic systems is still relatively scarce. The Sansheng porphyry W-Mo deposit (Mo 24,361 t @ 0.226% and WO3 17,285 t @ 0.569%), situated in eastern Inner Mongolia, northeastern China, features with quartz vein and veinlet-disseminated W-Mo orebodies primarily localized within the cupolas of an Early Cretaceous granitic intrusion. This contribution provides a comprehensive analysis of the deposit’s geology, in situ sulfur isotopic signatures, and geochemical characteristics of wolframite and sulfides to decipher the formation of the Sansheng deposit. A narrow δ34S range (2.15‰–7.14‰) for sulfides, consistent Y/Ho (5.09–6.23) and Nb/Ta (7.20–19.96) ratios in wolframite, and pyrite Co/Ni (1–10) and As/Ni (>10) ratios collectively point to a shared source—the highly fractionated Sansheng granitic magma. Wolframite, pyrite, arsenopyrite, and chalcopyrite all host significant trace elements, though their enrichment patterns differ considerably among these minerals. Temporal variations in trace element concentrations in wolframite and sulfides reveal a decline in fluid temperature and oxygen fugacity from early to late stages. Greisenization is associated with tungsten mineralization, whereas sericitization facilitates Stage III sulfide precipitation.

1. Introduction

Porphyry deposits are closely related to hypabyssal–subvolcanic intermediate–acidic intrusions and characterized by veinlet-disseminated mineralization and extensive hydrothermal alteration [1]. These deposits account for over 95% of global molybdenum and 60%–70% of global copper resources, and are also significant sources of tungsten and gold [2,3,4]. In recent years, with the discovery of the Jiangnan porphyry–skarn tungsten belt and breakthroughs in the exploration of the Dahutang W-Cu-Mo ore field, porphyry tungsten deposits have become an important type of tungsten resource [5]. In such deposits, tungsten primarily occurs as wolframite and scheelite, while associated metals are present as sulfide minerals such as molybdenite, chalcopyrite, galena, and sphalerite. The geodynamic triggers and metallogenic models for porphyry Cu-Mo systems are well-established globally. However, in porphyry W-Mo systems, the genetic processes controlling the coexistence of wolframite and sulfides remain poorly constrained. Whether the ore-forming materials of these ore minerals share a common source remains debated [4,6]. Their formation through multi-stage ore-forming fluid evolution is key to understanding the ore-forming mechanisms of porphyry tungsten deposits.

As one of the principal tungsten minerals in porphyry tungsten deposits, the geochemical composition of wolframite is controlled by crystal-chemical parameters and the composition of the initial fluids [7,8,9]. The trace element characteristics of wolframite can not only effectively trace the source of the ore-forming fluids but also reconstruct its crystallization process, providing critical constraints for revealing the evolution of magma–hydrothermal systems related to tungsten mineralization [10,11,12]. In porphyry W-Mo deposits, the trace element composition of sulfide minerals (e.g., pyrite) in multi-stage veins serves as an important indicator for deciphering the nature of the ore-forming fluids and reconstructing magmatic–hydrothermal processes [13,14,15]. Laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) analysis has been successfully applied for in situ elemental analysis of sulfides in Carlin-type gold deposits [16,17,18], magmatic–hydrothermal gold deposits [19,20,21], orogenic gold deposits [22,23], volcanogenic massive sulfide deposits [15,24,25], porphyry Cu-Au deposits [26,27,28], porphyry Mo deposits [29,30], and skarn deposits [31,32,33], providing direct evidence for detailed analysis of ore-forming processes. However, in situ trace element analyses of sulfides such as pyrite in porphyry W-Mo systems remain relatively limited, and controversies persist regarding the metal sources, fluid evolution, and ore-forming mechanisms of mineral assemblages from different stages.

This analytical gap is particularly critical for understanding the intricate coupling between W and base metal sulfide precipitation. A comprehensive, in situ geochemical study on both wolframite and sulfide minerals is crucial to decode the source, fluid evolution, and metal partitioning behaviors, which is a significant and understudied aspect in the global context of porphyry W-Mo deposit research.

The sulfur isotope composition of sulfides is an effective indicator for tracing the sulfur source in ore-forming systems [34]. Recent advances in in situ sulfur isotope microanalysis techniques enable the precise determination of δ34S at the micron scale in different generations of sulfides [35,36,37]. Compared to traditional bulk sample analytical techniques, which are susceptible to mixing of multi-stage sulfides, in situ techniques offer high spatial resolution and efficiency, providing a novel approach for detailed analysis of sulfur source in multi-stage sulfides and reconstruction of the ore-forming process [38,39,40].

The Sansheng W-Mo deposit, situated along the southern margin of NE China, is a medium-sized porphyry W–Mo deposit (WO3 reserves: 17,285 t @ 0.569%; Mo reserves: 24,361 t @ 0.226%). The deposit features veinlet-disseminated and vein-type mineralization [41]. Although the tungsten and molybdenum orebodies occur independently, they exhibit spatial cross-cutting relationships. Based on systematic field investigations and microscopic observations, five stages with characteristic mineral assemblages were identified, making it an ideal subject for in situ trace element and sulfur isotope studies to reveal the detailed ore-forming processes in porphyry W-Mo deposits. Previous research has primarily focused on the geological characteristics of the deposit [41], geochronology of magmatism and mineralization [42,43], genesis of the ore-bearing intrusion [41,43], sources of ore-forming fluids and materials [41], and fluid evolution [44]. However, due to a lack of in situ geochemical data and sulfur isotope information for different generations of ore minerals, key questions regarding the material sources, fluid properties, and formation mechanisms of each mineralization stage remain unresolved. This study details new in situ geochemical analyses of wolframite, pyrite, arsenopyrite, and chalcopyrite from multiple paragenetic stages, alongside in situ sulfur isotope data for the sulfide minerals. These results are utilized to constrain the origin and deposition mechanisms of the metallogenic elements, offering fresh perspectives on the genesis of the Sansheng W-Mo deposit. By employing a combination of in situ methods on coexisting sulfides and wolframite, our work elucidates the formation processes for these intrusion-related W-Mo systems in NE China, findings that carry significant implications for regional exploration. The integrated methodology and genetic model established in this study can serve as a valuable reference for understanding similar W-Mo metallogenic systems worldwide, particularly those related to highly evolved granites, thereby enhancing our global perspective on critical metal enrichment processes in magmatic–hydrothermal systems.

2. Regional Geology

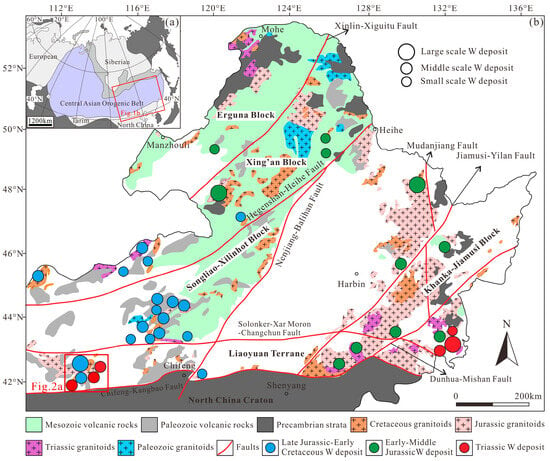

NE China is situated in the eastern segment of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt and is composed of the Erguna, Xing’an, Songliao–Xilinhot, Jiamusi, and Liaoyuan blocks [45] (Figure 1). This region underwent a complex tectonic evolution during the Phanerozoic: in the early Paleozoic (ca. 490 Ma), the Erguna and Xing’an blocks collided along the Xinlin–Xiguitu Fault; in the late Paleozoic (290–260 Ma), the Songliao–Xilinhot Block amalgamated with the Xing’an Block along the Hegenshan–Heihe Fault, while concurrently the Liaoyuan Block collided with the North China Craton along the Chifeng–Kangbao Fault; around 250 Ma, the scissor-like closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean occurred along the Solonker–Xar Moron–Changchun Fault [46,47]. During the Mesozoic, the Jiamusi Block accreted westwards due to the subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Plate [48]. Influenced by the combined effects of the closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean and Paleo-Pacific plate subduction, the region experienced large-scale magmatic–metallogenic events during the Mesozoic [49,50,51,52]. Identified WO3 resources in the region exceed 0.62 Mt, comprising 5 large, 18 medium, and 17 small tungsten deposits [53] (Figure 1b). Regional tungsten mineralization can be subdivided into three epochs: the Triassic metallogenic epoch (250–240 Ma), formed in a syn-/post-collisional setting triggered by the closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean, with deposits discretely distributed along the Solonker–Xar Moron–Changchun Fault; the Early–Middle Jurassic metallogenic epoch (200–170 Ma), controlled by both Paleo-Pacific plate subduction and the closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean, with deposits concentrated in the Lesser Xing’an-Zhangguangcai Range; and the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous metallogenic epoch (160–125 Ma), formed in a post-collisional extensional setting, with deposits mainly distributed in the southern Great Xing’an Range [53] (Figure 1b).

The southern Great Xing’an Range is bounded by the Nenjiang–Balianhan Fault to the east, Chifeng–Kangbao Fault to the south, and Hegenshan–Heihe Fault to the north [52,53] (Figure 1b). The regional strata consist primarily of Lower Paleozoic marine sedimentary rocks and Permian–Lower Triassic volcanic-sedimentary sequences (the Dashizhai, Zhesi, Linxi, and Laolongtou formations), widely overlain by Mesozoic volcanic lavas and volcaniclastic rocks [54]. Intrusive rocks in the area can be divided into two phases: Late Paleozoic (321–250 Ma) intrusions, dominated by tonalite–granodiorite–diorite assemblages, are mainly exposed in the eastern part; Mesozoic (150–131 Ma) intrusions are widely distributed and include monzogranite, syenogranite, granite porphyry, and granodiorite [55,56] (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Generalized tectonic framework of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (after [57]); (b) spatial distribution of significant tungsten deposits across NE China (after [49]).

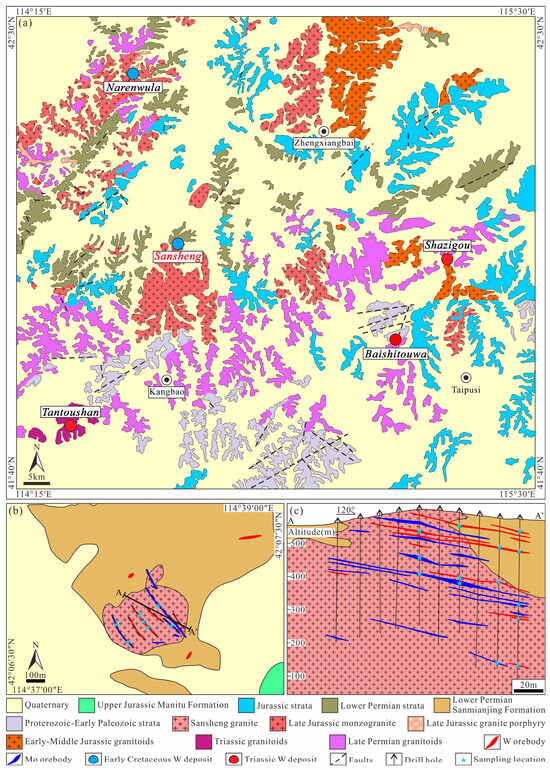

The Narenwula ore-concentrated area is located in the southwestern part of the southern Great Xing’an Range (Figure 1b). The stratigraphy of the area comprises Proterozoic–Early Paleozoic, Lower Permian, Jurassic, and Quaternary units [54]. The Proterozoic–Early Paleozoic strata are sporadically exposed, consisting mainly of medium- to high-grade metamorphic rocks such as leptynite, granulite, and metasandstone, associated with slate–phyllite–schist assemblages and crystalline limestone. The Lower Permian and Jurassic sequences are widely distributed, composed primarily of intermediate–acidic volcanic lavas, volcaniclastic rocks, and sedimentary clastic rocks. Granitic magmatism in the area can be divided into four phases: Late Permian granodiorite and quartz diorite widely intruded the Proterozoic–Early Paleozoic strata; Triassic granite (the ore-forming intrusion in the Tantoushan deposit) is locally exposed; Early–Middle Jurassic fine-grained granite and biotite granite are mainly distributed in the eastern part; and Late Jurassic monzogranite and granite porphyry are extensively distributed in the central-western part [54] (Figure 2a). The ore-concentrated area currently contains one large- (Narenwula) and four medium-sized (Baishitouwa, Sansheng, Shazigou, and Tantoushan) tungsten deposits.

Figure 2.

(a) Geological map illustrating the Narenwula ore-concentrated area (after [54]); (b) sketch geological map and (c) geological cross-section of the Sansheng W-Mo deposit (modified from [41]).

3. Ore Deposit Geology

The Sansheng W-Mo deposit is a medium-sized porphyry deposit situated 25 km southwest of Zhengxiangbai Banner in Inner Mongolia. The mining area primarily exposes the Lower Permian Sanmianjing Formation (dominated by siltstone and fine sandstone), the Upper Jurassic Manitu Formation (locally developed tuff–andesite assemblages in the southeast), and Quaternary [41] (Figure 2b). The Sansheng granite, emplaced around 136 Ma, serves as the main ore-bearing rock for the deposit. Orebodies occur predominantly in the cupolas of the pluton and secondarily within the Sanmianjing Formation [41] (Figure 2b,c). Precise geochronological studies indicate that the molybdenite Re-Os isochron age of 138.6 ± 1.4 Ma [41,42] is consistent within error with the in situ wolframite U-Pb age of 137.3 ± 2.0 Ma [43], confirming a synchronous and genetic link between W-Mo mineralization and the emplacement of the Sansheng granite. The genesis of the Sansheng granite involves lower-crust derivation through partial melting, followed by intense fractional crystallization, resulting in a highly evolved A-type composition. Both the granite emplacement and the W-Mo mineralization event occurred in an extensional tectonic setting triggered by the rollback of the Paleo-Pacific plate and the closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean [43].

A total of 81 tungsten and 144 molybdenum orebodies have been delineated in the deposit, the vast majority of which are concealed lenticular orebodies, with only a small number of sub-parallel veins exposed at the surface (Figure 2b,c). The main economic orebodies include No. 5, No. 20, and No. 23 tungsten orebodies (average WO3 grade 0.44%, a dip angle of 8–28° toward 50–55°), and No. 26, No. 27, and No. 28 molybdenum orebodies (average thickness 2.5 m, Mo grade 0.21%, a dip angle of 6–23° toward 50–55°). Ore minerals are dominated by wolframite, molybdenite, pyrite, and arsenopyrite, with subordinate chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and galena, mostly occurring as veins, veinlets, and disseminations (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Gangue minerals are mainly K-feldspar, quartz, muscovite, and sericite, followed by chlorite, calcite, and ankerite (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Representative ore characteristics from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit. (a) Stage I K-feldspar–quartz–magnetite vein. (b) Stage II-1 quartz–wolframite–pyrite vein. (c) A Stage II-2 quartz–wolframite–molybdenite–pyrite vein cross-cutting an earlier Stage II-1 quartz–wolframite–pyrite vein. (d) Stage II-2 ore composed of quartz, wolframite, molybdenite, and pyrite. (e) A Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite veinlet cutting through a Stage II-2 quartz–wolframite–molybdenite veinlet. (f) Stage III-1 quartz–sulfide ore. (g) Stage III-1 quartz–molybdenite–chalcopyrite vein truncated by a later Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite vein. (h) Stage IV quartz–pyrite vein cross-cutting Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite–pyrite ore. (i) Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite–pyrite vein cut by a Stage V quartz–ankerite vein. (j) Stage IV quartz–sulfide vein. (k) Stage V quartz–calcite vein cutting Stage IV quartz–pyrite vein. (l) Stage V quartz–carbonate–pyrite vein. Wol—wolframite; Mol—molybdenite; Py—pyrite; Apy—arsenopyrite; Ccp—chalcopyrite; Sp—sphalerite; Gn—galena; Mt—magnetite; Kfs—K-feldspar; Qtz—quartz.

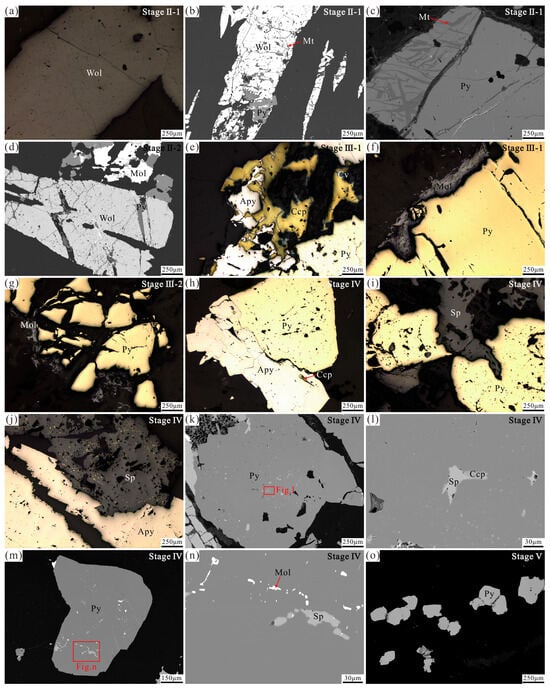

Figure 4.

Representative photomicrographs of the mineral assemblages in distinct stages from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit. (a) Tabular wolframite crystal of Stage II-1. (b) Wolframite containing magnetite replaces pyrite of Stage II-1. (c) Subhedral pyrite of Stage II-1 contains magnetite. (d) Pyrite coexists with molybdenite of Stage II-2 and replaces wolframite along crystal margins and fractures. (e) Coexisting pyrite, arsenopyrite, and chalcopyrite of Stage III-1. Covellite replaces chalcopyrite. (f) Molybdenite replaces pyrite along crystal margins of Stage III-1. (g) Fractured pyrite replaced by molybdenite of Stage III-2. (h) Arsenopyrite containing chalcopyrite inclusions coexists with pyrite of Stage IV. (i) Anhedral sphalerite replaces pyrite of Stage IV. (j) Irregular sphalerite replaces euhedral arsenopyrite of Stage IV. (k,l) Subhedral pyrite of Stage IV contains sphalerite and chalcopyrite inclusions. (m,n) Subhedral pyrite of Stage IV contains sphalerite and molybdenite inclusions. (o) Stage V fine-grained pyrite. Wol—wolframite; Mt—magnetite; Py—pyrite; Mol—molybdenite; Apy—arsenopyrite; Ccp—chalcopyrite; Cv—covellite; Sp—sphalerite.

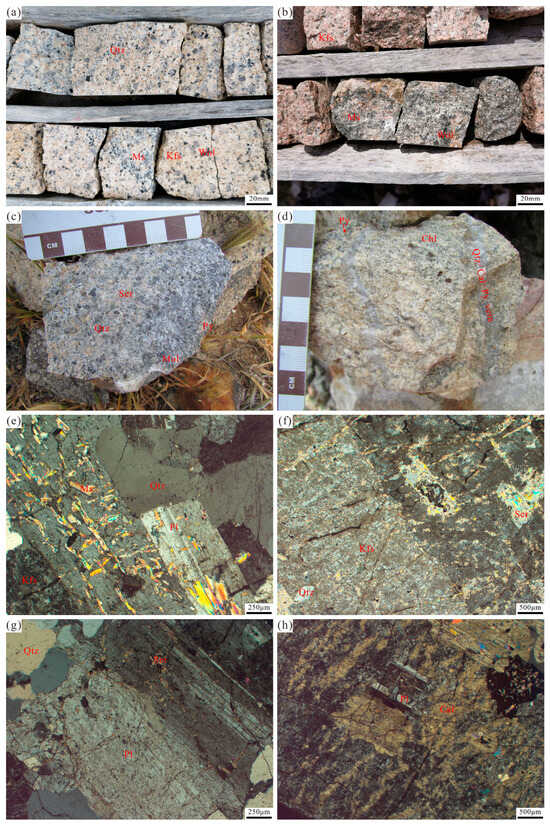

Figure 5.

Representative hand specimen and photomicrographs (cross-polarized light) of gangue minerals from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit. (a) Disseminated wolframite occurs in granite with silicification, K-feldspathization, and greisenization. (b) Disseminated wolframite occurs in granite with greisenization and K-feldspathization. (c) Granite with sericitization and silicification surrounding the molybdenite–pyrite veins. (d) Granite with chloritization surrounding the quartz–carbonate–pyrite veins. (e) Replacement of K-feldspar and plagioclase by muscovite. (f) Replacement of K-feldspar by quartz and sericite. (g) Replacement of plagioclase by sericite and quartz, occurring along crystal margins and fractures. (h) Replacement of plagioclase by calcite. Wol—wolframite; Py—pyrite; Mol—molybdenite; Kfs—K-feldspar; Qtz—quartz; Pl—plagioclase; Cal—calcite; Chl—chlorite; Ser—sericite; Ms—muscovite.

Hydrothermal alteration assemblages at Sansheng encompass K-feldspathization, greisenization, silicification, chloritization, sericitization, and carbonatization (Figure 5). Silicification, manifested as quartz veins or disseminations, is widely distributed in the ore and altered granite (Figure 5a,b); secondary quartz often replaces primary quartz (recrystallization) (Figure 5a), K-feldspar (Figure 5f), and plagioclase (Figure 5g). K-feldspathization is often associated with silicification, forming potassic alteration zones (Figure 5a,b). Greisenization is mainly developed in the granite surrounding wolframite-quartz veins, characterized by a quartz–muscovite assemblage where plagioclase and K-feldspar are replaced by quartz and muscovite (Figure 5e), and is often associated with disseminated wolframite (Figure 5a,b), being spatially closely related to tungsten mineralization. Sericitization occurs as aggregates in the wall rock of sulfide veins, characterized by the replacement of K-feldspar and plagioclase by sericite (Figure 5c,f,g). Chloritization often occurs together with carbonatization (Figure 5d). Carbonatization, as a post-ore low-temperature alteration, consists mainly of calcite and ankerite (Figure 3i,l and Figure 5d,h), and quartz–ankerite veins and quartz–calcite veins often cross-cut early quartz–sulfide veins (Figure 3i,k).

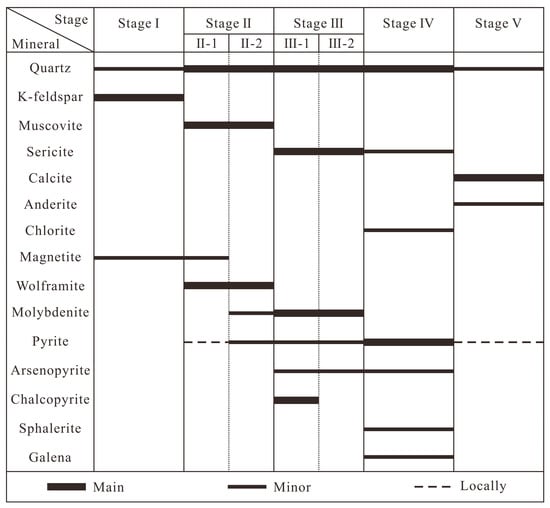

The evolution of the hydrothermal system at the Sansheng W-Mo deposit is categorized into five stages, based on diagnostic criteria including mineral paragenesis, alteration styles, and vein cross-cutting relationships (Figure 6). Stage I features K-feldspar–quartz–magnetite veins, lacking wolframite and sulfides (Figure 3a). Stage II is the main tungsten-forming stage. In Stage II-1, quartz appears abundantly, magnetite persists, and abundant tabular wolframite and minor pyrite form (Figure 4a,b); magnetite inclusions are present within wolframite and pyrite (Figure 4b,c). This stage develops quartz–wolframite(–pyrite) veins (Figure 3b,c). In Stage II-2, magnetite disappears, molybdenite begins to appear, coexisting with wolframite and minor pyrite (Figure 4d). This stage develops quartz–wolframite–molybdenite(–pyrite) veins (Figure 3c–e). Stage II-2 quartz–wolframite–molybdenite–pyrite veins cross-cut Stage II-1 quartz–wolframite–pyrite veins (Figure 3c). Stage III marks the disappearance of wolframite and is the main molybdenite ore-forming stage. In Stage III-1, molybdenite is often associated with chalcopyrite, pyrite, and arsenopyrite (Figure 3f and Figure 4f), developing quartz–molybdenite–chalcopyrite(–pyrite-arsenopyrite) veins (Figure 3f,g). In Stage III-2, chalcopyrite disappears, and molybdenite occurs alone or associated with pyrite (Figure 4g), developing quartz–molybdenite(–pyrite) veins (Figure 3g–i). Stage III-1 quartz–molybdenite–chalcopyrite veins are cross-cut by Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite veinlets (Figure 3g). Stage IV is dominated by pyrite, associated with arsenopyrite, sphalerite, and galena (Figure 3h,j and Figure 4h,i); minor chalcopyrite occurs as droplets within sphalerite (Figure 4j). Pyrite contains inclusions of sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and molybdenite (Figure 4k–n). Quartz–pyrite veins cross-cut Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite–pyrite ore (Figure 3h). Stage V contains only minor subhedral–anhedral fine-grained pyrite as sulfides (Figure 4o). Quartz–ankerite veins cross-cut Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite–pyrite veins (Figure 3i), and quartz–calcite veins cross-cut Stage IV quartz–pyrite veins (Figure 3k).

Figure 6.

Paragenesis of minerals in the Sansheng W-Mo deposit.

4. Sampling and Analytical Methods

4.1. Samples

Based on field exposures and drill core, fifty representative specimens were acquired for this investigation, comprising thirty sulfide and twenty wolframite samples, and the sampling location is illustrated in Figure 2b,c. Wolframite was sourced from Stage II-1 quartz–wolframite–pyrite veins and Stage II-2 quartz–wolframite–molybdenite(–pyrite) veins. Sulfide minerals were collected from multiple stages, including Stage II-1 and II-2 wolframite-bearing veins, Stage III-1 quartz–molybdenite–chalcopyrite(–pyrite–arsenopyrite) veins, Stage III-2 quartz–molybdenite(–pyrite) veins, Stage IV quartz–pyrite(–arsenopyrite–galena–sphalerite) veins, and Stage V quartz–calcite–pyrite veins. All specimens were prepared as polished thin sections for detailed microscopic examination to determine mineral paragenesis. To clarify textural relationships between different mineral generations and ensure analytical reliability, backscattered electron imaging of wolframite and sulfides was conducted at the Key Laboratory of Resource Exploration Research in Handan, China.

4.2. In Situ Sulfur Isotope Analyses of Sulfides

In situ sulfur isotope measurements on sulfide minerals were performed at Beijing Createch Testing Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) employing a Neptune Plus multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a RESOlution SE 193 nm laser ablation system (Applied Spectra Inc., West Sacramento, CA, USA). The experimental parameters were set as follows: spot sizes of 24–38 μm, repetition rate of 6 Hz, and laser energy density of 4 J/cm2. To minimize short-term signal fluctuation, particularly under low pulse frequency conditions, a signal-smoothing device was installed downstream of the ablation cell. Isotopes 32S, 33S, and 34S were measured simultaneously in static mode using Faraday cup detectors. Signal sensitivity was enhanced using the Neptune Plus’s X-type skimmer cone and Jet sample cone (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Introduction of nitrogen (4 mL/min) into the central gas flow helped suppress polyatomic interferences. Each analysis included 20 s of background signal acquisition, 40 s of sample data acquisition, and 40 s of washout time. A standard-sample bracketing approach was applied for δ34S determination, using an external pyrite reference material (ZX; δ34SV-CDT = 16.9‰) for mass bias correction. The external reproducibility (2σ) was better than 0.2‰. For comprehensive details regarding instrument settings and analytical methodology, refer to [58].

4.3. In Situ Trace Element Analysis of Wolframite

In situ trace element composition of wolframite was determined at Wuhan Sample Solution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) using an Agilent 7700e ICP-MS (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) interfaced with a GeoLas 2005 laser ablation system (Coherent, Göttingen, Germany). Analyses employed a laser repetition rate of 6 Hz, fluence of 5 J/cm2, and a spot diameter of 60 μm. The ablation cell, optimized for reduced internal volume, ensured rapid aerosol washout. Prior to enclosure, the chamber was flushed with helium, which also served as the carrier gas for transporting the ablated aerosol. A standard-free calibration method utilizing multiple external reference materials (USGS glass reference materials BCR-2G, BIR-1G, and BHVO-2G) was applied, with standard reference data obtained from the GeoReM database. Each analysis comprised 20–30 s of background signal acquisition and 50 s of sample signal acquisition. To remove potential surface contamination, pre-ablation (~8 laser pulses) was conducted at each spot. Only analytical intervals displaying stable, smooth signals were retained to minimize spectral interference from fluid inclusions or other mineral phases. A complete description of operating conditions and methodology was reported in [59]. Data reduction was carried out with ICPMSDataCal12.2 [60,61].

4.4. In Situ Trace Element Analyses of Sulfides

Trace element concentrations in pyrite and chalcopyrite were measured using an Agilent 7700e ICP-MS with a GeoLas Pro laser ablation system at Wuhan Sample Solution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Analytical conditions followed [62], employing a 32 μm spot size at a 5 Hz repetition rate. Each analysis cycle comprised 20–30 s background and 50 s sample signal acquisition. For quality assurance, reference materials MASS-1 and NIST 610 were analyzed after every 10 unknown samples. Arsenopyrite trace element data were acquired at Beijing Createch Testing Technology Co., Ltd. using an AnalytikJena PQMS ICP-MS (Analytik Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany) coupled with a RESOLution 193 nm laser ablation system. Operating parameters included 5 J/cm2 energy density, 5 Hz repetition rate, and 26 μm spot size. Measurement cycles contained 20 s background and 45 s sample acquisition. Quality control involved repeated analysis of multiple reference materials (NIST 610, NIST 612, BHVO-2G, BCR-2G, BIR-1G, and MASS-1) at 10-sample intervals. All sulfide trace element data were processed using ICPMSDataCal [60].

5. Results

5.1. In Situ Sulfur Isotopic Compositions

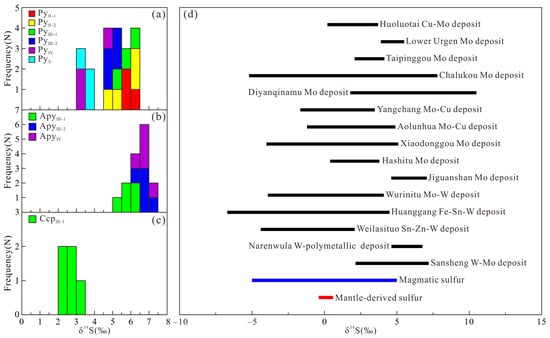

A total of 40 sets of in situ sulfur isotope data were obtained for sulfides from various stages in the Sansheng W-Mo deposit (Table S1 and Figure 7). The δ34S values of pyrite from Stage II-1 range from 5.59‰ to 6.41‰, while those from Stage II-2 range from 4.91‰ to 6.15‰. For Stage III-1, the δ34S values are 5.33‰ to 6.18‰ for pyrite, 5.25‰ to 6.20‰ for arsenopyrite, and 2.15‰ to 3.37‰ for chalcopyrite. In Stage III-2, the δ34S values of pyrite and arsenopyrite range from 4.60‰ to 5.17‰ and 6.29‰ to 7.05‰, respectively. For Stage IV, the δ34S values are 3.14‰ to 4.59‰ for pyrite and 6.48‰ to 7.14‰ for arsenopyrite. Pyrite from Stage V has δ34S values ranging from 3.43‰ to 3.89‰.

Figure 7.

Sulfur isotope values of sulfides from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit (a–c) and their comparison with regional Late Mesozoic W-Mo mineralized systems (d).

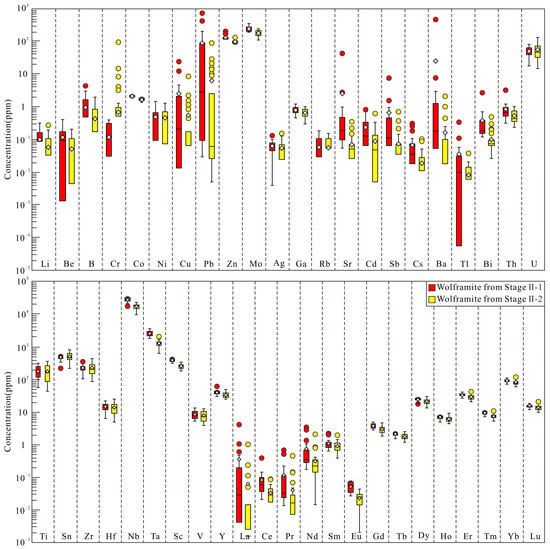

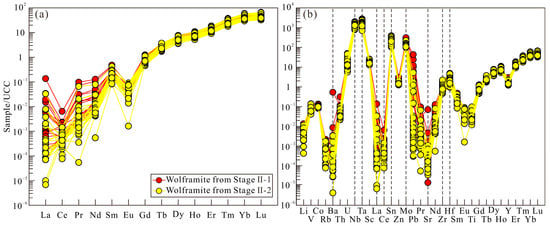

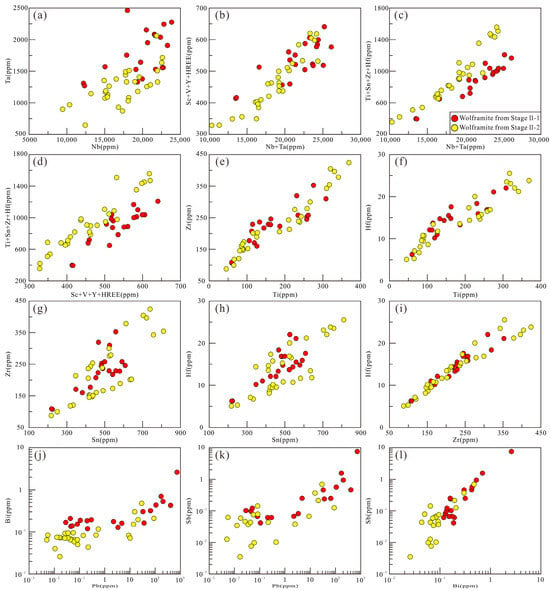

5.2. Trace Element Compositions of Wolframite

In situ trace element data for the two generations of wolframite from Stage II at the Sansheng W-Mo deposit are shown in Figure 8 and Table S2, with representative laser ablation signals shown in Figure 9a–f. In Stage II-1 wolframite, the concentrations of Zn, Mo, Ti, Sn, Zr, Nb, Ta, and Sc are close to or exceed 100 ppm; Pb, Hf, Y, Lu, Yb, Er, and Dy range from 10 to 100 ppm; B, Cr, Co, Cu, V, Gd, Tb, Ho, and Tm range from 1 to 10 ppm; and the remaining components are less than 1 ppm. In Stage II-2 wolframite, the concentrations of Zn, Mo, Ta, Nb, Zr, Sn, Ti, and Sc are close to or exceed 100 ppm; Hf, Y, Lu, Yb, Er, and Dy are between 10 and 100 ppm; Cr, Co, Cu, Pb, V, Gd, Tb, Ho, and Tm range from 1 to 10 ppm; and the remaining components are less than 1 ppm.

Figure 8.

Tukey box plots illustrating the trace element distribution in wolframite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit. In these plots, the box encompasses the interquartile range (IQR), defined by the 25th and 75th percentiles. The central line within the box marks the median value, while gray diamonds indicate the mean for each dataset. The whiskers extend to a maximum of 1.5 times the IQR beyond either end of the box. Data points falling beyond the whiskers are classified as outliers.

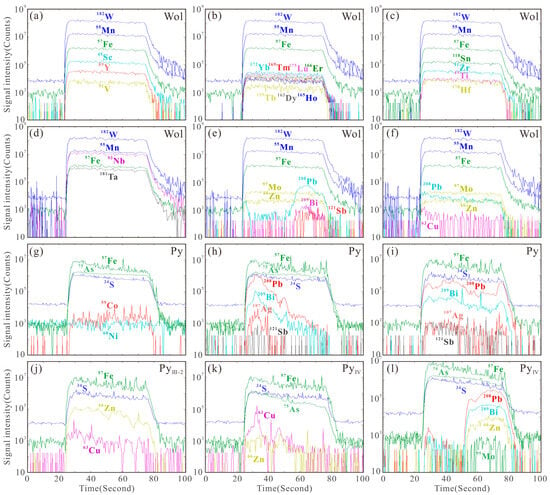

Figure 9.

Representative laser ablation signals of wolframite (a–f) and pyrite (g–l).

The total rare earth element (ΣREE) concentrations in Stage II-1 and Stage II-2 wolframite range from 149.33 to 229.83 ppm (mean 190.61 ppm) and 117.51 to 238.98 ppm (mean 166.48 ppm), respectively. Both exhibit significant fractionation characteristics: low light rare earth element (LREE) contents (0.94–10.98 ppm and 0.40–5.74 ppm) and highly enriched heavy rare earth element (HREE) contents (147.39–226.58 ppm and 117.11–237.31 ppm). The upper crust-normalized REE patterns show a left-dipped trend characterized by LREE depletion and HREE enrichment for both generations [63] (Figure 10a). The trace element patterns reveal that all samples are featured with enrichment in Nb, Zr, Sn, Mo, Ta, and Hf, and depletion of Sr and Ba (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Chondrite-normalized REE (a) and primitive mantle-normalized trace element (b) distribution patterns for wolframite in the Sansheng W-Mo deposit (after [63]).

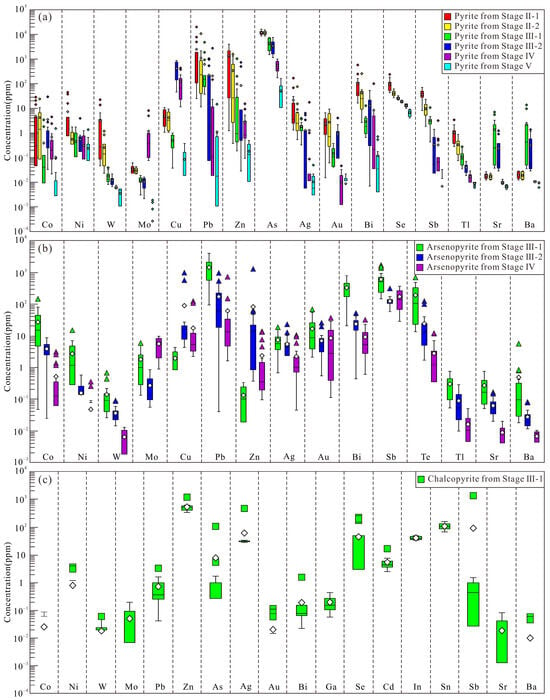

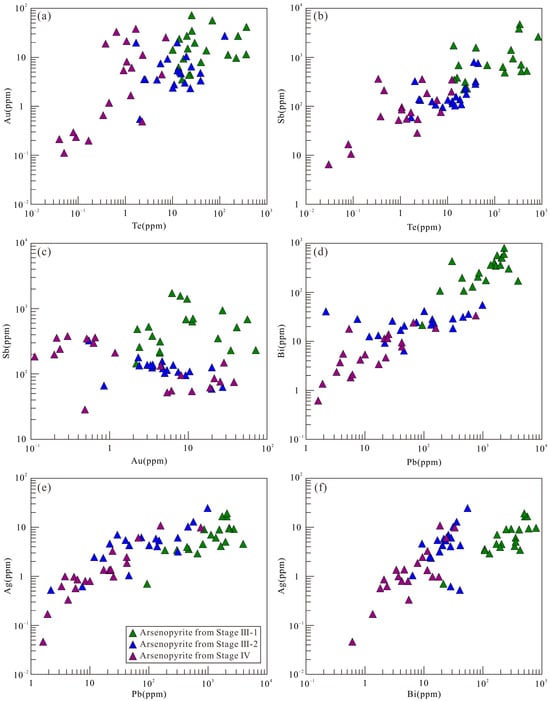

5.3. Trace Element Compositions of Sulfides

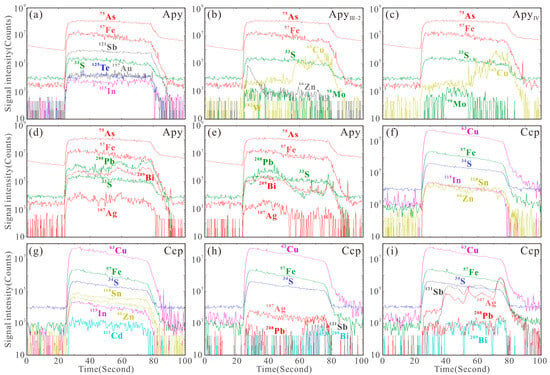

In situ trace element data for pyrite, arsenopyrite, and chalcopyrite are presented in Tables S3–S5 and Figure 11, with representative laser ablation signals shown in Figure 9g–l and Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Tukey box plots displaying trace element distributions in pyrite (a), arsenopyrite (b), and chalcopyrite (c) from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit. Each box defines the interquartile range (IQR), bounded by the 25th and 75th percentiles. A horizontal line inside the box marks the median, while gray diamonds show mean values. Whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR above and below the box. Data points located outside this range are considered outliers.

Figure 12.

Representative laser ablation signals of arsenopyrite (a–e) and chalcopyrite (f–i) at Sansheng.

Pyrite exhibits stage-specific geochemical signatures: Stage II-1 contains the highest contents of Ni, W, Ag, Zn, Pb, Bi, Se, Sb, and Tl; both Stages II-1 and II-2 show high As contents; Stage III-1 is enriched in Sr and Ba; Stage III-2 contains the highest Cu; Stage IV contains the highest Mo; Co contents remain relatively stable across stages (lowest in Stage V), while Ni concentrations are similar in all stage pyrite except for Stage II-1. From Stage II-1 to V, systematic decreasing trends are observed for W, Zn, Pb, As, Bi, Ag, Se, Tl, and Sb (Figure 11a).

Arsenopyrite displays the following characteristics: Stage III-1 contains the highest concentrations of Co, Ni, W, Pb, Au, Bi, Sb, Te, Tl, Sr, and Ba; Stage III-2 contains the highest Cu and Zn; Stage IV contains the highest Mo; Ag is elevated in Stages III-1 and III-2, while Sb shows similar levels in Stages III-2 and IV. Concentrations of Co, Ni, W, Pb, Bi, Te, Tl, Sr, and Ba progressively decrease from Stage III-1 to Stage IV (Figure 11b).

Stage III-1 chalcopyrite contains Zn and Sn at concentrations close to or greater than 100 ppm; Ag, Se, and In are between 10 and 100 ppm; Ni, As, and Cd are 1 to 10 ppm; and all other elements are below 1 ppm. Among these, W, Zn, Ag, Cd, In, and Sn show relatively stable concentrations, while Mo, Pb, As, Au, Bi, Ga, Se, Sb, Sr, and Ba exhibit significant variation (Figure 11c).

6. Discussion

6.1. Source of Materials

Sulfides in the Sansheng W-Mo deposit primarily consist of molybdenite, pyrite, and arsenopyrite, with subordinate chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and galena. The lack of sulfate minerals suggests that H2S prevailed as the dominant sulfur species in the hydrothermal fluid during sulfide deposition [64]. Under low-oxygen, low-pH conditions typical of such H2S-dominated systems, the relationship δ34Ss ≈ δ34SH2S ≈ δ34Spyrite is expected to hold at isotopic equilibrium [64]. Measured δ34S values for pyrite, arsenopyrite, and chalcopyrite across all mineralization stages span from 2.15‰ to 7.14‰, averaging 5.22‰. Notably, in stages III-2 and IV, coexisting pyrite exhibits lower δ34S values than associated arsenopyrite—a reversal of the predicted equilibrium fractionation trend (pyrite > arsenopyrite > chalcopyrite). This deviation implies that full isotopic equilibrium was not attained among co-precipitating sulfides [65]. Such disequilibrium is frequently documented in hydrothermal ore systems and is commonly attributed to kinetic effects during crystallization [66,67,68]. In dynamic hydrothermal regimes, crystallization sequence, growth rate, and local fluid heterogeneity can produce isotopic fractionation that departs from theoretical equilibrium predictions [64]. For example, if arsenopyrite nucleates earlier or more rapidly than pyrite, it may incorporate heavier δ34S, leaving the residual fluid isotopically lighter for subsequent pyrite formation. Conversely, the lower δ34S values of chalcopyrite relative to coexisting pyrite and arsenopyrite in stage III-1 align well with equilibrium fractionation behavior. In such contexts, the δ34S value of pyrite can be taken as representative of the bulk sulfur isotopic composition of the hydrothermal system [69]. The δ34SH2S values were derived from the following expression:

where i denotes the sulfide phase (Ai = 0.4 for pyrite), and T is temperature in Kelvin [69]. Homogenization temperature averages for each stage from [44] were applied in the calculation. Resulting δ34SH2S values for pyrite from stages II-1 to V are as follows: 4.63–5.45 (II-1), 3.95–5.19 (II-2), 4.09–4.94 (III-1), 3.36–3.93 (III-2), 1.74–3.19 (IV), and 1.88–2.34 (V). These values are significantly higher than those of mantle-derived sulfur (0.1 ± 0.5‰) [70] but closely align with the typical range for magmatic sulfur (0 ± 5‰) [34,64] (Figure 7d). A comparison with sulfur isotope data from Late Mesozoic tungsten and molybdenum deposits in NE China reveals that deposits such as the Narenwula W-polymetallic deposit (4.68‰–7.02‰) [71], the Weilasituo Sn-Zn-W deposit (−4.4‰–2‰) [72,73], the Huanggang Fe-Sn-W deposit (−6.7‰–4.5‰) [74,75,76,77], the Wurinitu Mo-W deposit (−3.9‰–4.1‰) [78,79], the Jiguanshan Mo deposit (4.62‰–7.07‰) [80], the Hashitu Mo deposit (0.4‰–3.8‰) [81], the Xiaodonggou Mo deposit (−4‰–5.1‰) [82], the Aolunhua Mo-Cu deposit (−1.2‰–4.9‰) [83,84,85], the Yangchang Mo-Cu deposit (−1.66‰–3.48‰) [86], the Diyanqinamu Mo deposit (1.78‰–10.41‰) [87,88], the Chalukou Mo deposit (−5.2‰–7.8‰) [89,90,91,92], the Taipinggou Mo deposit (2.08‰–4.14‰) [93], the Lower Urgen Mo deposit (3.9‰–5.5‰) [94], and the Huoluotai Cu-Mo deposit (0.2‰–3.7‰) [95,96] all exhibit magmatic sulfur signatures (Figure 7d), collectively confirming a magmatic sulfur source for the Sansheng W-Mo deposit.

δ34SH2S = δ34Si − Ai(106 × T−2)

The trace element composition of wolframite is a key indicator for tracing the source of ore-forming materials [7]. The two generations of wolframite from Stage II at the Sansheng deposit display similar REE and trace element patterns (Figure 10), indicating an identical source. The similar ionic radii of Y3+ (0.93 Å) and Ho3+ (0.97 Å) result in generally constant Y/Ho ratios in magmatic–hydrothermal systems [97]. The Y/Ho ratios of the two wolframite generations are 5.16–6.23 and 5.09–5.90, respectively, further confirming a consistent source. Although the Nb/Ta ratios of Stage II-1 wolframite (7.20–14.61) are slightly lower than those of Stage II-2 (10.53–19.96), the limited variation in Nb/Ta values for all samples (<3 times) is more restricted compared to the reported variation (>10 times) for cogenetic wolframite in the French Massif Central deposits [7]. Combined with the geochemical behavior of Nb-Ta, which typically do not fractionate significantly in magmatic systems [98], this evidence robustly demonstrates a unified material source for both wolframite generations.

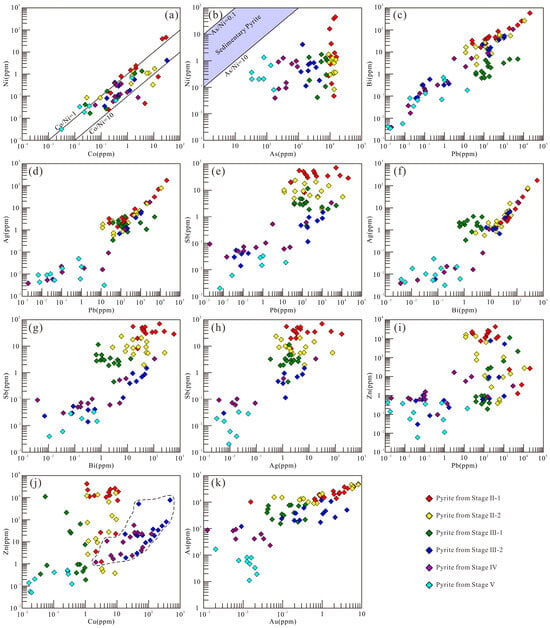

The Ni and Co contents and Co/Ni ratios in pyrite are important indicators for discriminating ore-forming environments [16,99]. Sedimentary pyrite is typically Ni-rich with Co/Ni < 1, while magmatic–hydrothermal pyrite usually has Co/Ni ratios of 1–10 [100,101]. The pyrite Co/Ni ratios of various stages at Sansheng predominantly fall within the 1–10 range (Figure 13a), indicating a magmatic–hydrothermal origin. The As/Ni ratios of Sansheng pyrite (61-285564) are significantly higher than those of sedimentary pyrite (0.1–10) [100], further supporting this conclusion (Figure 13b). Although Cu/Ni and Zn/Ni ratios can also be used for genetic discrimination [100], this method is not applicable in this study because Zn and Cu often appear as mineral inclusions within the pyrite (Figure 4l and Figure 9j–l). LA-ICP-MS analysis of fluid inclusions indicates that all mineralization stages exhibit elevated Mn and B concentrations, alongside distinctive elemental ratios (e.g., high Rb/Sr, Zn/Na, Pb/Na, Ba/Na, Rb/Na, K/Na, Li/Na, and low K/Rb), which align closely with geochemical signatures of the Sansheng ore-bearing granite. Furthermore, the consistent Cs/Rb and Cs/(Na + K) ratios jointly attest to a fluid source originating from a homogeneous, highly fractionated granitic magma [44].

Figure 13.

Binary diagrams of trace elements in pyrite from different stages in the Sansheng W-Mo deposit (a–k).

Integrating the sulfur isotope data of sulfides, the geochemical components of pyrite and wolframite, and previous fluid inclusion geochemical data, we propose that the mineralization across different stages at Sansheng shares a unified material source. Ore-forming materials for the deposit were continuously supplied by the highly evolved Sansheng ore-bearing granite.

6.2. Occurrence of Trace Elements in Minerals

6.2.1. Wolframite

Previous studies have shown that wolframite can enrich trace elements through various mechanisms, including solid solution, nanoparticles, and micro- to nano-scale inclusions [7,102,103]. Analysis of laser ablation profiles, box plots, and binary diagrams can reveal the occurrence states of different elements in wolframite: Trivalent (Sc3+, V3+, Y3+, and HREEs), tetravalent (Ti4+, Sn4+, Zr4+, Hf4+), and pentavalent (Nb5+, Ta5+) cations exhibit smooth signal profiles parallel to those of major elements (Fe, Mn, W) (Figure 9a–d). Combined with positive correlations in element pairs such as Nb-Ta-(Sc + V + Y + HREE)-(Ti + Sn + Zr + Hf) (Figure 14a–i), this indicates that these elements are homogeneously distributed within the crystal lattice via solid solution. Zn2+ (isomorphically substituting for Fe2+/Mn2+) and Mo6+ (substituting for W6+) [104] show stable signal profiles (Figure 9e,f) and constant concentrations > 100 ppm (Figure 8), confirming their occurrence in solid solution. In contrast, Cu shows fluctuating signals, and its concentration varies > 2 orders of magnitude) (Figure 8). Pb (spiky signals, synchronous with Bi-Sb signals, concentration variation > 4 orders of magnitude) shows positive correlations with Bi and Sb (Figure 14j–l). This evidence indicates that Cu and Pb are present in wolframite as micro-inclusions.

Figure 14.

Binary diagrams of trace elements in two generations of wolframite in the Sansheng W-Mo deposit (a–l).

6.2.2. Pyrite

The smooth and stable signal profiles of Ni, Co, and As in pyrite (Figure 9g) indicate their homogeneous distribution: Co and Ni enter the crystal lattice via isomorphous substitution for Fe2+ (showing positive correlation in content, Figure 13a), while As substitutes for S in a non-stoichiometric manner [105,106]. All three elements exist in solid solutions. The significantly larger ionic radius of Pb2+ compared to Fe2+ [104], its fluctuating signal profiles (Figure 9h,i,l), and anomalously high concentrations (Figure 11a) suggest that Pb is primarily hosted as micro-inclusions of galena. The synchronous signal variations in Bi, Ag, and Sb with Pb (Figure 9h,i) and their positive correlations (Figure 13c–h) confirm their coexistence with galena micro-inclusions. The co-varying Cu and Zn signal profiles (Figure 9j,k) and their positive content correlation (Figure 13j) in Stage III-2 and IV pyrite, combined with the microscopic observation of sphalerite–chalcopyrite inclusions (Figure 4l,n), jointly verify their occurrence as micro-inclusions. The positive As-Au correlation in Stage II-III pyrite (Figure 13k) suggests that As may facilitate Au enrichment. The anomalously high Mo content in Stage IV pyrite, its synchronously fluctuating signal profile with Pb (Figure 9l), and the presence of molybdenite micro-inclusions (Figure 4n) definitively confirm that Mo and Pb occur as mineral micro-inclusions within the Stage IV pyrite.

6.2.3. Arsenopyrite

Laser ablation signal analysis reveals that Sb, Te, Au, and In in arsenopyrite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit display smooth signal profiles that are parallel to those of the major elements (As, Fe, S) (Figure 12a), indicating their homogeneous distribution. Based on ionic substitution mechanisms [104], Te substitutes for S, Sb substitutes for As, and Au and In substitute for Fe, entering the crystal lattice; all four elements thus exist in solid solution. The positive Au-Te content correlation (Figure 15a) indicates that Te facilitates Au enrichment [107], while the positive Te-Sb correlation (Figure 15b) reflects their synchronous incorporation into the lattice. The lack of association between Au and Sb (Figure 15c) suggests different occurrence mechanisms. From Stage III-1 to Stage III-2, the Cu content in arsenopyrite increases significantly (Figure 11b). Its fluctuating signal profiles, which are not synchronous with the major elements (Figure 12b,c), indicate that Cu in Stages III-2 and IV exists as micro-inclusions. The Mo content shows an initial decrease followed by a later increase (Figure 11b). The weak signals in Stage III-2 (Figure 12b) strengthening in Stage IV (Figure 12c) reflect the precipitation of molybdenite primarily in Stage III, followed by its occurrence as micro-inclusions in Stage IV. The anomalous Zn content and its signal fluctuations, independent of Cu, in Stage III-2 (Figure 12b) indicate its occurrence as independent mineral inclusions. The fluctuating yet parallel signal profiles of Pb-Bi-Ag across different stages (Figure 12d,e), their wide concentration ranges (Figure 11b), and significant positive correlations (Figure 15d–f) collectively confirm their occurrence as mineral micro-inclusions.

Figure 15.

Binary diagrams of trace elements in arsenopyrite from different stages in the Sansheng W-Mo deposit (a–f).

6.2.4. Chalcopyrite

Although numerous studies indicate that chalcopyrite has a limited capacity for trace element incorporation when coexisting with other sulfides [15,108,109], the Stage III-1 chalcopyrite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit exhibits significant enrichment in Zn, Sn, In, and Cd. Compared to coexisting pyrite and arsenopyrite, its Zn (<0.2 wt%), Sn, In, and Cd contents are stable (varying by less than one order of magnitude; Figure 11c), and their smooth laser ablation signal profiles, parallel to those of the major elements (Figure 12f,g), confirm the homogeneous distribution of these elements: Zn is present in solid solution [31,110]; Sn and In enter the crystal lattice by substituting for Fe [104,111]; and Cd preferentially substitutes for Cu, with hydrothermal chalcopyrite typically being more enriched in Cd compared to magmatic chalcopyrite [104,109,112]. Silver exhibits a dual occurrence mode: stable signals indicate its distribution in solid solution (Figure 12h), while fluctuating signals, synchronous with Pb, Bi, and Sb (Figure 12i), indicate the presence of micro-inclusions of galena.

6.3. Mineralization Processes

Sulfides in situ sulfur isotope data, combined with geochemical compositions of wolframite and sulfides, reveal that the ore-forming fluids and metals at Sansheng are attributed to a common reservoir—the uniform Sansheng granitic magma. Simultaneously, the trace element evolutionary characteristics provide key constraints for deciphering the ore-forming fluid evolution and metal precipitation mechanisms [9,26,113].

The systematic evolution of mineral trace elements indicates a continuous cooling process of the ore-forming fluids at Sansheng: Nb and Ta, being temperature-sensitive elements [114], show decreasing concentrations from Stage II-1 to II-2 wolframite, reflecting temperature decrease (Figure 8). Although trace element contents differ between the two wolframite stages, their consistent left-dipped REE and trace element patterns (Figure 10) indicate an identical source. The decrease in HREE in Stage II-2 wolframite may result from the preferential consumption of HREE by Stage II-1 wolframite crystallization. The content variations in the temperature-sensitive elements Se [113,115] and Sb (transported as thioantimonate complexes, with temperature-dependent solubility) [116] in pyrite further support this trend: Se content decreases continuously from the highest values in Stage II-1 to the lowest in Stage V, and Sb content decreases systematically from Stage II-1 to Stage V, collectively indicating a gradual decline in sulfide crystallization temperature (Figure 11a).

The fluid oxygen fugacity (fO2) at Sansheng evolved stage-wise: The mineral assemblage transition from Stage I (K-feldspar + quartz + magnetite) through Stage II-1 (quartz + wolframite + magnetite ± pyrite) to a sulfide-dominated system from Stage II-2 onwards (Figure 3 and Figure 4) indicates a significant drop in fO2 starting from Stage II-2. The valence fractionation of the redox-sensitive element Eu (Eu3+/Eu2+) serves as an important indicator: Eu3+ (0.95 Å), due to its similar ionic radius to Fe2+ (0.78 Å) and Mn2+ (0.83 Å) [104], is more readily incorporated into the wolframite lattice [117]. The higher Eu content in Stage II-1 wolframite (Figure 8) reflects formation under higher fO2 conditions. The limited lattice incorporation of Cr3+ (0.61 Å) also corroborates this trend; the lower Cr content in Stage II-1 wolframite (Figure 8) likewise indicates high fO2 conditions. The partitioning of Sc, Ta, and Nb in wolframite further constrains fluid properties: high fO2 and low pH favor Ta and Nb enrichment, whereas low fO2 and PO43−/F−-rich fluids favor Sc incorporation [9]. The higher Sc, Ta, and Nb contents in Stage II-1 wolframite (Sc potentially sourced from fluids interacting with Sc-rich strata) collectively support the conclusion of high fO2 fluid during this stage.

The genetic link between greisenization and wolframite precipitation is well established [118,119,120]. At the Sansheng deposit, tungsten mineralization is spatially closely associated with greisenization (Figure 5). Greisenization of plagioclase and K-feldspar under high-temperature conditions can release Sr and Ba into the fluid, which can then be hosted as micro-inclusions in wolframite. The higher Ba and Sr contents in Stage II-1 wolframite (Figure 8) indicate more intense greisenization during this stage. Notably, the anomalously high Sr and Ba contents in Stage III pyrite (Figure 11a) correspond with the intense contemporaneous sericitization alteration (Figure 5), reflecting the capture of Sr and Ba released during alteration as micro-inclusions within pyrite. The significant decrease in Sr and Ba in Stage IV and V pyrite might be related to the influx of meteoric water [44], a phenomenon that further confirms the coupled relationship between alteration and mineralization.

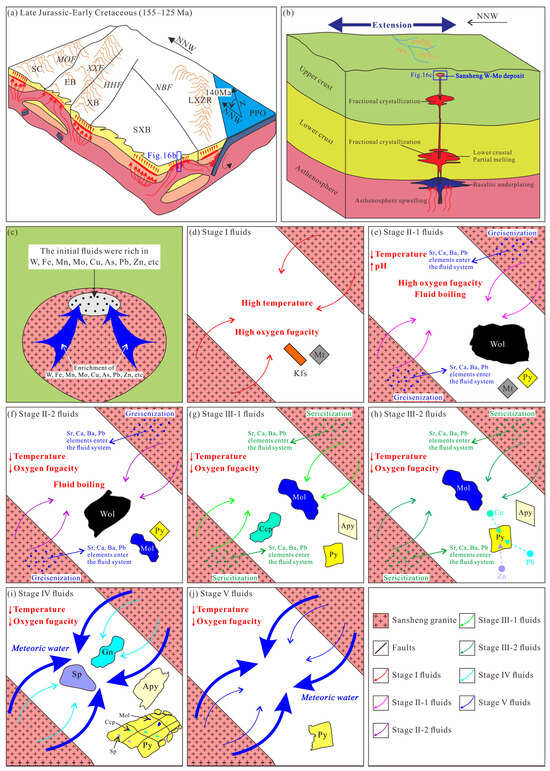

6.4. Metallogenic Model of the Sansheng Magmatic–Hydrothermal System

During the Early Cretaceous, the study area was under an extensional setting controlled by the combined effects of Paleo-Pacific plate rollback and the closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean [53,121,122] (Figure 16a). Petrogenetic studies indicate that the Sansheng ore-bearing granite (136.8–136.0 Ma) was primarily derived from partial melting of the lower crust, followed by intense fractional crystallization [43], a process conducive to the enrichment of ore-forming materials within the granitic magma [114,123]. (Figure 16b). In situ S isotopic compositions and trace element data of minerals demonstrate that the metallogenic materials of all stages at Sansheng share the same granitic magmatic source. Integrated with fluid inclusions LA-ICP-MS data of various stages [44], it is revealed that the homogeneous and highly evolved Sansheng granite served as the sustained source for high-temperature, metal-rich ore-forming fluids (Figure 16c). During the magmatic–hydrothermal transition stage, the system had high fO2, forming high-temperature K-feldspar–quartz–magnetite veins (Figure 16d).

Figure 16.

(a) Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous tectonic setting of the Sansheng region (after [124]). (b) Conceptual model of the Sansheng W-Mo system (after [43]). (c) Progressive fractional crystallization concentrated metals within the melt, followed by their partitioning into magmatic–hydrothermal fluids. (d–j) Schematic representation of fluid evolution and paragenetic sequence for multiple wolframite and sulfide generations. LXZR—Lesser Xing’an-Zhangguangcai Range; SXB—Songliao-Xilinhot Block; XB—Xing’an Block; EB—Erguna Block; SC—Siberian Craton; NBF—Nenjiang–Balihan Fault; HHF—Heganshan–Heihe Fault; XXF—Xinlin–Xiguitu Fault; MOF—Mongolia-Okhotsk Fault; PPO—Paleo-Pacific Ocean; Kfs—K-felspar; Sp—sphalerite; Gn—galena; Apy—arsenopyrite; Ccp—chalcopyrite; Mol—molybdenite; Py—pyrite; Wol—wolframite; Mt—magnetite.

The evolved fluids ascended along fractures in the Sansheng mining area and interacted with the cooled granite, causing water–rock interactions that resulted in silicification, potassic alteration, and greisenization. As the fluid temperature dropped to 320–420 °C, the high fO2 environment, coupled with fluid boiling and greisenization, significantly promoted the large-scale precipitation of Stage II-1 wolframite [44] (Figure 16e). With decreasing fO2 of the fluids, minor molybdenite and pyrite appeared in the Stage II-2 veins. During this stage, Zn primarily entered the wolframite lattice in solid solution, while Pb and Cu were present as mineral micro-inclusions within the wolframite. Mo, in addition to precipitating as molybdenite, also occurred in solid solution within the wolframite lattice (Figure 16f).

As the fluid temperature further reduced to 250–340 °C [44] and the fO2 of the fluid system dropped further, large-scale molybdenite precipitation commenced, influenced by fluid boiling and sericitization. Early Stage III-1 molybdenite coexisted with chalcopyrite, pyrite, and arsenopyrite, while late Stage III-2 molybdenite often occurred alone or associated with pyrite (Figure 16g,h). The significantly high Cu content in Stage III-2 pyrite indicates that Cu was present as mineral micro-inclusions within the pyrite. Compared to Stage II pyrite, the lower Mo content in this stage is related to the large-scale precipitation of Mo predominantly as molybdenite, which depleted the Mo content in the ore-forming fluids. Zn and Pb continued to occur as mineral micro-inclusions within the pyrite and arsenopyrite of this stage.

With the invasion of meteoric water in Stage IV, the fluid temperature dropped to 220–300 °C [44]. Cooling and dilution triggered by fluid mixing promoted the deposition of pyrite, galena, sphalerite, and arsenopyrite in this stage, while also reducing the trace element contents in the arsenopyrite and pyrite. The relatively high Mo and Cu contents in the pyrite suggest their continued precipitation as mineral micro-inclusions within pyrite after their large-scale precipitation in Stage III (Figure 16i).

The Stage V ore-forming fluids consisted predominantly of meteoric water, with its temperature declining to 200–270 °C [44]. The mineral assemblage mainly consists of quartz, calcite, and ankerite. Sulfides are represented only by minor subhedral–anhedral fine-grained pyrite (Figure 16j). Almost all trace element contents in this stage’s pyrite are the lowest, implying a significant decrease in the contents of both precipitating and non-precipitating elements, marking the termination of the formation process of the Sansheng W-Mo deposit.

7. Conclusions

(1) The Sansheng W-Mo deposit experienced five ore-forming stages. Most of wolframite precipitated in Stage II. Molybdenite began to appear during Stage II-2, and massive molybdenite deposition happened in Stage III. A significant quantity of chalcopyrite was stored in Stage III-1 veins.

(2) Sulfides from different stages share consistent δ34S values (2.15‰–7.14‰), indicating the sulfur mainly originated from a unified granitic magma. Two generations of wolframite have similar left-dipped REEN and trace element patterns, and relatively constant Y/Ho (5.09–6.23) and Nb/Ta ratios (7.20–19.96). Six generations of pyrite maintain high As/Ni ratios (>10) and uniform Co/Ni (mostly 1–10). Combined with prior fluid inclusion investigation, we propose that the multi-stage ore-forming materials at Sansheng were all derived from the highly fractionated Sansheng granitic magma.

(3) Significant partitioning differences are observed for trace elements among the ore minerals. Wolframite strongly incorporates Zn, Mo, Sc, Ta, Nb, Zr, Sn, and Ti; pyrite concentrates As; arsenopyrite sequesters Te and Sb; and chalcopyrite collects In, Sn, Zn, and Cd. This distribution pattern is fundamentally controlled by substitution into the crystal structure via solid solution.

(4) Compositional evolution of trace elements in sulfides and wolframite through successive stages documents a trend of fluid cooling and redox decline. Greisenization is genetically associated with tungsten deposition, whereas sericitization facilitates the precipitation of sulfide. Following the deposition of Cu and Mo in stages III, residual amounts of these metals were hosted within later pyrite as micro-inclusions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min15121283/s1, Table S1: In situ sulfur isotopes of pyrite, arsenopyrite, and chalcopyrite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit; Table S2: LA-ICP-MS trace element concentrations (in ppm) of wolframite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit; Table S3: LA-ICP-MS trace element concentrations (in ppm) of pyrite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit; Table S4: LA-ICP-MS trace element concentrations (in ppm) of arsenopyrite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit; Table S5: LA-ICP-MS trace element concentrations (in ppm) of chalcopyrite from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.X. and C.J.; methodology, W.X.; formal analysis, W.X.; investigation, W.X., C.J., Q.Z., R.W., J.W., R.D. and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; writing—review and editing, C.J. and Q.Z.; visualization, W.X.; supervision, C.J.; funding acquisition, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department (Grant No. BJ2025178), Hebei Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. D2025402002), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 91962104), and Open Research Fund Program of Key Laboratory of Metallogenic Prediction of Nonferrous Metals and Geological Environment Monitoring (Ministry of Education), Central South University (Grant No. 2024YSJS10).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have significantly improved the quality of this manuscript. We would like to thank Zheng-Tao Zhu and Jian-Mei Tang from Beijing Createch Testing Technology Co., Ltd. for their technical support in the sulfides in situ sulfur isotope analysis and arsenopyrite LA-ICP-MS analysis. We also acknowledge Yun-Ze Huang and Zhen-Hua Hu from Wuhan Sample Solution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd. for their professional assistance during the LA-ICP-MS analyses of chalcopyrite, pyrite, and wolframite.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seedorff, E.; Dilles, J.H.; Proffett, J.M.; Einaudi, M.; Zurcher, L.; Stavast, W.J.A.; Johnson, D.A.; Barton, M.D. Porphyry deposits: Characteristics and origin of hypogene features. Econ. Geol. 2005, 100, 251–298. [Google Scholar]

- Sillitoe, R.H. Porphyry copper systems. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.Y.; Zhao, K.D.; Jiang, H.; Su, H.M.; Xiong, S.F.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Xu, Y.M.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, L.Y. Spatiotemporal distribution, geological characteristics and metallogenic mechanism of tungsten and tin deposits in China: An overview. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 3730–3745. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, P.; Pan, J.Y.; Han, L.; Cui, J.M.; Gao, Y.; Fan, M.S.; Li, W.S.; Chi, Z.; Zhang, K.H.; Cheng, Z.L.; et al. Tungsten and tin deposits in South China: Temporal and spatial distribution, metallogenic models and prospecting directions. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2023, 157, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.W.; Wu, S.H.; Song, S.W.; Dai, P.; Xie, G.Q.; Su, Q.W.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.G.; Yu, Z.Z.; Chen, X.Y.; et al. The world-class Jiangnan tungsten belt: Geological characteristics, metallogeny, and ore deposit model. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 3746–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.D.; Lehmann, B.; Deng, C.Z.; Zhang, X.C.; Luo, A.B.; Chen, Y.H.; Yin, R.S. Multiple metal sources in polymetallic W-Sn ore deposits revealed by mercury stable isotopes. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2024, 67, 3465–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlaux, M.; Mercadier, J.; Marignac, C.; Peiffert, C.; Cloquet, C.; Cuney, M. Tracing metal sources in peribatholitic hydrothermal W deposits based on the chemical composition of wolframite: The example of the Variscan French Massif Central. Chem. Geol. 2018, 479, 58–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.D.; Luo, T.; Li, J.W.; Hu, Z.C. Direct dating of hydrothermal tungsten mineralization using in situ wolframite U–Pb chronology by laser ablation ICP-MS. Chem. Geol. 2019, 515, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Shao, Y.J.; Cheng, Y.B.; Jiang, S.Y. Discrete Jurassic and Cretaceous Mineralization Events at the Xiangdong W(-Sn) Deposit, Nanling Range, South China. Econ. Geol. 2020, 115, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.Q.; Gao, J.F.; Lu, J.J.; Wu, J.W. In-situ LA-ICP-MS trace element analyses of scheelite and wolframite: Constraints on the genesis of veinlet-disseminated and vein-type tungsten deposits, South China. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2018, 99, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, B.; Kong, H.; Wu, Q.H.; Chen, S.F.; Li, H.; Wu, J.H. In situ geochemistry and Sr–O isotopic composition of wolframite and scheelite from the Yaogangxian quartz vein-type W(–Sn) deposit, South China. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2022, 149, 105066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.L.; Hu, J.R.; Chen, X.F.; Fan, L.F.; Guo, D.B.; Zhang, Y.K.; Feng, F.; Cao, H.W. Zircon, wolframite and helvite U-Pb geochronology and geochemistry of the Hongjianbingshan tungsten polymetallic deposit: Implications for the Triassic critical metal mineralization in the Beishan orogenic belt, China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2025, 41, 260–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.V.; Large, R.R.; Bull, S.W.; Maslennikov, V.; Berry, R.F.; Fraser, R.; Froud, S.; Moye, R. Pyrite and pyrrhotite textures and composition in sediments, laminated quartz veins, and reefs at Bendigo gold mine, Australia: Insights for ore genesis. Econ. Geol. 2011, 106, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.L.; Zeng, Q.D.; Sun, G.T.; Duan, X.X.; Bonnetti, C.; Riegler, T.; Long, D.G.F.; Kamber, B. Laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS) elemental mapping and its applications in ore geology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2019, 35, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo, E.; Beaudoin, G.; Dare, S.; Genna, D.; Petersen, S.; Relvas, J.M.R.S.; Piercey, S.J. Trace Element Composition of Chalcopyrite from Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide Deposits: Variation and Implications for Provenance Recognition. Econ. Geol. 2023, 118, 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, R.R.; Danyushevsky, L.; Hollit, C.; Maslennikov, V.; Meffre, S.; Gilbert, S.; Bull, S.; Scott, R.; Emsbo, P.; Thomas, H. Gold and trace element zonation in pyrite using a laser imaging technique: Implications for the timing of gold in orogenic and Carlin-style sediment-hosted deposits. Econ. Geol. 2009, 104, 635–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, E.A.; Jilly-Rehak, C.; Sack, P.; Phillips, D.L.; Gopon, P. Nanoscale Characteristics of Carlin-Type Auriferous Pyrite from the Nadaleen Trend, Yukon. Econ. Geol. 2024, 119, 1643–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, R.C.; He, X.H.; Wang, X.Y. Application of principal component analysis method based on machine learning to gold deposit type discrimination: A case study of the geochemical characteristics of pyrite. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2024, 40, 1801–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Xie, G.Q.; Olin, P. Texture, in-situ geochemical, and S isotopic analyses of pyrite and arsenopyrite from the Longshan Sb-Au deposit, southern China: Implications for the genesis of intrusion-related Sb-Au deposit. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2022, 143, 104781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.Y.; Song, M.C.; Santosh, M.; Li, J. The gold-telluride connection: Evidence for multiple fluid pulses in the Jinqingding telluride-rich gold deposit of Jiaodong Peninsula, Eastern China. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Liang, G.Z.; Wu, J.J.; Yang, K.F.; Fan, H.R.; Zeng, Q.D.; Zhang, Z.M.; Hu, F.F. Two periods of gold mineralization-magmatism-tectonism in the East Kunlun metallogenic belt. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2025, 41, 526–543. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.F.; Evans, K.; Li, J.W.; Fougerouse, D.; Large, R.R.; Guagliardo, P. Metal remobilization and ore-fluid perturbation during episodic replacement of auriferous pyrite from an epizonal orogenic gold deposit. Geochim. Cosmochimca Acta 2019, 245, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.Y. Trace elements in pyrite from orogenic gold deposits: Implications for metallogenic mechanism. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2023, 39, 2330–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; McDonald, I.; Jamieson, J.; Jenkin, G.R.T.; McFall, K.A.; Piercey, G.; MacLeod, C.J.; Layne, G.D. Mineral-scale variation in the trace metal and sulfur isotope composition of pyrite: Implications for metal and sulfur sources in mafic VMS deposits. Miner. Depos. 2022, 57, 911–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Y.; Deng, X.H.; Pirajno, F. Textures, trace element compositions, and sulfur isotopes of pyrite from the Honghai volcanogenic massive sulfide deposit: Implications for ore genesis and mineral exploration. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 66, 738–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, M.; Deditius, A.; Chryssoulis, S.; Li, J.W.; Ma, C.Q.; Parada, M.A.; Barra, F.; Mittermayr, F. Pyrite as a record of hydrothermal fluid evolution in a porphyry copper system: A SIMS/EPMA trace element study. Geochim. Cosmochimca Acta 2013, 104, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M.; Haase, K.M.; Chivas, A.R.; Klemd, R. Phase separation and fluid mixing revealed by trace element signatures in pyrite from porphyry systems. Geochim. Cosmochimca Acta 2022, 329, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Cooke, D.R.; Baker, M.J.; Zhang, L.J.; Liang, P.; Fang, J.; Olin, P.; Danyushevsky, L.V.; Chen, H.Y. Using pyrite composition to track the multi-stage fluids superimposed on a porphyry Cu system. Am. Mineral. 2024, 109, 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, D.R.; Wilkinson, J.J.; Baker, M.; Agnew, P.; Phillips, J.; Chang, Z.S.; Chen, H.Y.; Wilkinson, C.C.; Inglis, S.; Hollings, P.; et al. Using Mineral Chemistry to Aid Exploration: A Case Study from the Resolution Porphyry Cu-Mo Deposit, Arizona. Econ. Geol. 2020, 115, 813–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.W.; Liu, B.; Wang, T.S.; Zhou, L.L.; Wang, Y.B.; Sun, G.T.; Hou, K.J.; Weng, S.F.; Zeng, Q.D.; Long, Z.; et al. Genesis of the Danping bauxite deposit in northern Guizhou, Southwest China: Constraints from in-situ elemental and sulfur isotope analyses in pyrite. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2022, 148, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Chen, S.Y.; Tian, H.; Zhao, J.N.; Tong, X.; Chen, X.S. Trace element and S isotope characterization of sulfides from skarn Cu ore in the Laochang Sn-Cu deposit, Gejiu district, Yunnan, China: Implications for the ore-forming process. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2021, 134, 104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.J.; Shao, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.Y.; Zhang, S.T.; Zhao, H.T.; Li, H.B. Pyrite geochemical fingerprinting on skarn ore-forming processes: A case study from the Huangshaping W-Sn-Cu-Pb-Zn deposit in the Nanling Range, South China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2024, 262, 107474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.J.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, P.P.; Li, R.J.; Huang, Y.; Ding, W.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, M.X.; Sun, L.H.; Wang, Z.K.; et al. Indium concentrations as a potential indicator of orebody-intrusion distance in a skarn Pb-Zn system, elucidated by the Fozichong Orefield (South China). Ore. Geol. Rev. 2024, 165, 105912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, R.R. Sulfur Isotope Geochemistry of Sulfide Minerals. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2006, 61, 633–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.R.; Li, X.H.; Zuo, Y.B.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Hu, F.F.; Feng, K. In-situ LA-(MC)-ICPMS and (Nano) SIMS trace elements and sulfur isotope analyses on sulfides and application to confine metallogenic process of ore deposit. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2018, 34, 3479–3496. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.T.; Zeng, Q.D.; Zhou, L.L.; Philip Hollis, S.; Zhou, J.X.; Chen, K.Y. Mechanisms for invisible gold enrichment in the Liaodong Peninsula, NE China: In situ evidence from the Xiaotongjiapuzi deposit. Gondwana Res. 2022, 103, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.W.; Zeng, Q.D.; Zhou, L.L.; Liu, B.; Fu, Y.; Sun, G.T.; Yu, B.; Long, Z. Genesis and prospecting significance of the Buziwannan gold-polymetallic ore deposit in the West Kunlun Orogen Belt, China: Constraints from mineral geochemistry and in situ S–Pb isotope analyses of sulfides. J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 244, 107125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Fan, H.R.; Zhu, R.X.; Yang, K.F.; Yu, X.F.; Li, D.P.; Zhang, Y.W.; Ma, W.D.; Feng, K. In-situ monazite Nd and pyrite S isotopes as fingerprints for the source of ore-forming fluids in the Jiaodong gold province. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2022, 147, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Zeng, Q.D.; Santosh, M.; Fan, H.R.; Bai, R.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.W.; Huang, L.L. Deep ore-forming fluid characteristics of the Jiaodong gold province: Evidence from the Qianchen gold deposit in the Jiaojia gold belt. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2022, 145, 104911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Zeng, Q.D.; Frimmel, H.E.; Fan, H.R.; Xue, J.L.; Yang, J.H.; Wu, J.J.; Bao, Z.A. Spatio-temporal fluid evolution of gold deposit in the Jiaodong Peninsula, China: A case study of the giant Xiling deposit. J. Geochem. Explor. 2024, 260, 107455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. The Mineralization of Sansheng W-Mo Deposit in Huade, Inner Mongolia. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Geological Science, Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J.; Zhou, Y.; Dang, Z.C.; Zhao, Z.L.; Li, C.; Qu, W.J.; Cao, Z.C.; Yang, G.J.; Fu, C.; Tang, W.L. Re-Os isotopic dating of molybdenites from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit in Huada County, Inner Mongolia, and its geological significance. Geol. Bull. China 2016, 35, 531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Zeng, Q.D.; Lan, T.G.; Zhou, L.L.; Wang, R.L.; Wu, J.J. Genetic link between the Late Mesozoic granitic magmatism and W mineralization in NE China: Constraints from in-situ U-Pb geochronology and geochemistry of wolframite, and whole-rocks geochemistry analyses of W-bearing granites from the Sansheng W-Mo deposit. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2022, 144, 104868. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Zeng, Q.D.; Huang, L.L.; Zhou, L.L.; Fan, H.R.; Wu, J.J.; Wang, R.L.; Zhu, H.P. Composition and evolution of ore-forming fluids in the Sansheng porphyry W-Mo deposit, Inner Mongolia, NE China: Evidence from LA-ICP-MS analysis of fluid inclusions. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2023, 158, 105481. [Google Scholar]

- Sengör, A.M.C.; Natal’in, B.A.; Burtman, V.S. Evolution of the Altaid tectonic collage and Paleozoic crustal growth in Eurasia. Nature 1993, 364, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J.; Windley, B.F.; Hao, J.; Zhai, M.G. Accretion leading to collision and the Permian Solonker suture, Inner Mongolia, China: Termination of the central Asian orogenic belt. Tectonics 2003, 22, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, W.M.; Feng, Z.Q.; Wen, Q.B.; Neubauer, F.; Liang, C.Y. A review of the Paleozoic tectonics in the eastern part of Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 2017, 43, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.B.; Wilde, S.A. The crustal accretion history and tectonic evolution of the NE China segment of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 2013, 23, 1365–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.D.; Liu, J.M.; Yu, C.M.; Ye, J.; Liu, H.T. Metal deposits in the Da Hinggan Mountains, NE China: Styles, characteristics, and exploration potential. Int. Geol. Rev. 2011, 53, 846–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, H.G.; Mao, J.W.; Zhou, Z.H.; Su, H.M. Late Mesozoic metallogeny and intracontinental magmatism, southern Great Xing’an Range, northeastern China. Gondwana Res. 2015, 27, 1153–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, K.Z.; Zhai, M.G.; Li, G.M.; Zhao, J.X.; Zeng, Q.D.; Gao, J.; Xiao, W.J.; Li, J.L.; Sun, S. Links of collage orogenesis of multiblocks and crust evolution to characteristic metallogeneses in China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.L.; Zeng, Q.D.; Zhang, Z.C.; Zhou, L.L.; Qin, K.Z. Extensive mineralization in the eastern segment of the Xingmeng orogenic belt, NE China: A regional view. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2021, 135, 104204. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Zeng, Q.D.; Wang, R.L.; Wu, J.J.; Zhang, Z.M.; Li, F.C.; Zhang, Z. Spatial-temporal distribution and tectonic setting of Mesozoic W-mineralized granitoids in the Xing-Meng Orogenic Belt, NE China. Int. Geol. Rev. 2022, 64, 1845–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMBGMR. Regional Geology of Inner Mongolia; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.Y.; Sun, D.Y.; Ge, W.C.; Zhang, Y.B.; Grant, M.L.; Wilde, S.A.; Jahn, B.M. Geochronology of the Phanerozoic granitoids in northeastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Lu, C.D.; Zeng, Z.X.; Mohammed, A.S.; Liu, Z.H.; Dai, Q.Q.; Chen, K.L. Nature and significance of the late Mesozoic granitoids in the southern Great Xing’an range, eastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Int. Geol. Rev. 2019, 61, 584–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J.; Huang, B.C.; Han, C.M.; Sun, S.; Li, J.L. A review of the western part of the Altaids: A key to understanding the architecture of accretionary orogens. Gondwana Res. 2010, 18, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.H.; Zeng, Q.W.; Tao, S.Y.; Cao, R.; Zhou, Z.H. Mineralogical Characteristics and in-situ Sulfur Isotopic Analysis of Gold-Bearing Sulfides from the Qilishan Gold Deposit in the Jiaodong Peninsula, China. J. Earth Sci.-China 2021, 32, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Shao, Y.J.; Zhou, H.D.; Wu, Q.H.; Liu, J.P.; Wei, H.T.; Zhao, R.C.; Cao, J.Y. Ore-forming mechanism of quartz-vein-type W-Sn deposits of the Xitian district in SE China: Implications from the trace element analysis of wolframite and investigation of fluid inclusions. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2017, 83, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Hu, Z.C.; Gao, S.; Günther, D.; Xu, J.; Gao, C.G.; Chen, H.H. In situ analysis of major and trace elements of anhydrous minerals by LA-ICP-MS without applying an internal standard. Chem. Geol. 2008, 257, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Gao, S.; Hu, Z.C.; Gao, C.G.; Zong, K.Q.; Wang, D.B. Continental and oceanic crust recycling-induced melt-peridotite interactions in the Trans-North China Orogen: U-Pb dating, Hf isotopes and trace elements in zircons from mantle xenoliths. J. Petrol. 2010, 51, 537–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, K.Q.; Klemd, R.; Yuan, Y.; He, Z.Y.; Guo, J.L.; Shi, X.L.; Liu, Y.S.; Hu, Z.C.; Zhang, Z.M. The assembly of Rodinia: The correlation of early Neoproterozoic (ca. 900 Ma) high-grade metamorphism and continental arc formation in the southern Beishan Orogen, southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB). Precambrian Res. 2017, 290, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S. 3.01−Composition of the continental crust. Treatise Geochem. 2003, 3, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmoto, H.; Rye, R.O. Isotope of sulfur and carbon. In Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits, 2nd ed.; Barnes, H.L., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmoto, H. Stable isotope geochemistry of ore deposits. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 1986, 16, 491–559. [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher, M.E.; Smock, A.M.; Cypionka, H. Sulfur isotope fractionation during experimental precipitation of iron(II) and manganese(II) sulfide at room temperature. Chem. Geol. 1998, 146, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, J.M.; Fischer, T.P.; Sharp, Z.D.; King, P.L.; Wilke, M.; Botcharnikov, R.E.; Cottrell, E.; Zelenski, M.; Marty, B.; Klimm, K.; et al. Sulfur degassing at Erta Ale (Ethiopia) and Masaya (Nicaragua) volcanoes: Implications for degassing processes and oxygen fugacities of basaltic systems. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2013, 14, 4076–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.J.; Zhou, M.F.; Li, X.C.; Huang, F.; Malpas, J. Constraints of Fe-S-C stable isotopes on hydrothermal and microbial activities during formation of sediment-hosted stratiform sulfide deposits. Geochim. Cosmochimca Acta 2021, 313, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; He, Z.L.; Shen, S.L.; Yang, Z.L.; Du, J.F. Stable isotope geology of the Dongchuang and the Wenyu gold deposits and the source of ore-forming fluids and materials. Contrib. Geol. Miner. Resour. Res. 1993, 8, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, H.; Des Marais, D.J.; Ueda, A.; Moore, J.G. Concentrations and isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in ocean-floor basalts. Geochim. Cosmochimca Acta 1984, 48, 2433–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Jin, C.; Zeng, Q.D.; Zhou, L.L.; Wu, J.J.; Wang, R.L.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.J. Ore genesis of the large Narenwula W polymetallic deposit, NE China: Evidence from mineral geochemistry and in-situ S isotope analyses of sulfides. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2025, 184, 106732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.H.; Nie, F.J.; Liu, Y.F.; Yun, F. Sulfur and lead isotopic compositions of Bairendaba and Weilasituo silver-polymetallic deposits, Inner Mongolia. Miner. Depos. 2010, 29, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, H.G.; Mao, J.W.; Santosh, M.; Wu, Y.; Hou, L.; Wang, X.F. The Early Cretaceous Weilasituo Zn–Cu–Ag vein deposit in the southern Great Xing’an Range, northeast China: Fluid inclusions, H, O, S, Pb isotope geochemistry and genetic implications. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Wang, J.B.; Wang, Y.W.; Mao, Q. Fluid-melt inclusions in fluorite of the Huanggangliang skarn iron-tin deposit and their significance to mineralization. Acta Geol. Sin. 2001, 75, 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.H.; Wang, A.S.; Li, T. Fluid inclusion characteristics and metallogenic mechanism of Huanggang Sn-Fe deposit in Inner Mongolia. Miner. Depos. 2011, 30, 867–889. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, W.; Lu, X.B.; Cao, X.F.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ai, Z.L.; Tang, R.K.; Abfaua, M.M. Ore genesis and hydrothermal evolution of the Huanggang skarn iron-tin polymetallic deposit, southern Great Xing’an Range: Evidence from fluid inclusions and isotope analyses. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2015, 64, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.J.; Liu, J.J.; Zhai, D.G.; Wang, J.P.; Xing, Y.L. Sulfur and lead isotopic compositions of the polymetallic deposits in the southern Daxing’anling: Implications for metal sources. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2012, 42, 362–373. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.H.; Wang, J.P.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, S.G.; Wang, Q.Y.; Kang, S.G.; Zhang, J.X.; Zhao, Y. Isotope geochemistry of the Wurinitu W-Mo deposit in Sunid Zuoqi, Inner Mongolia, China. Geoscience 2013, 27, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.H.; Zhang, F.F.; Liu, J.J.; Xue, C.J.; Zhang, Z.C. Genesis of the Wurinitu W-Mo deposit, Inner Mongolia, northeast China: Constraints from geology, fluid inclusions and isotope systematics. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2018, 94, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Chu, S.X.; Liu, J.M.; Liu, H.T.; Zeng, Q.D. S and Pb isotopic composition of the Jiguanshan porphyry molybdenum deposit in Inner Mongolia: Indication to the source of ore-forming material. Geol. Explor. 2020, 56, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, D.G.; Liu, J.J.; Tombros, S.; Williams-Jones, A.E. The genesis of the Hashitu porphyry molybdenum deposit, Inner Mongolia, NE China: Constraints from mineralogical, fluid inclusion, and multiple isotope (H, O, S, Mo, Pb) studies. Miner. Depos. 2017, 53, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Y. Geology, ore genesis and the source of ore-forming materials in the Xiaodonggou Mo deposit, Inner Mongolia. Xinjiang Nonferrous Met. 2017, 40, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.H.; Chen, B. The source of hydrothermal fluids and mineralization in the Aolunhua porphyry Mo-Cu deposit, southern Da Hinggan Mountains: Constraints from stable (C, H, O and S) and radiogenic (Pb) isotopes. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2011, 41, 1770–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, T.; Wang, J.B.; Wang, Y.W.; Yuan, J.M.; Lin, L.J.; Dou, J.L.; Jiang, W.; Li, W.; Ma, X.H. Geological characteristics and genesis of the Aolunhua porphyry Mo-Cu deposit, Inner Mongolia. Geol. Explor. 2011, 47, 737–747. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Fu, L.J.; Huang, G.H.; Cui, Z.L.; Wang, K.Y.; Sun, Q.F. Source of ore-forming fluids and metallogenic mechanism in Aolunhua Mo- Cu deposit, Inner Mongolia. Gold 2021, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Zhou, Q.Z.; Liu, J.M.; Zeng, Q.D. Sulfur isotope composition of the Yangchang molybdenum—Copper deposit in Inner Mongolia and its geological significance. Geol. Explor. 2018, 54, 544–551. [Google Scholar]