Abstract

New intensified flotation technologies have emerged to enhance fine and ultrafine particle recovery. However, their modelling remains challenging, as it requires defining the effective collection volume, residence time, and internal recirculation, factors not included in conventional models, while also facing operational complexity and the limited availability of key hydrodynamic and kinetic data. This study presents the development of a flotation model for the Concorde Cell technology, which separates the flotation process into three stages: collection zone, separation tank, and froth transport. The collection zone was represented as a plug-flow reactor with a rectangular rate of constant distribution; the separation zone as a perfect mixer with a detachment efficiency factor; and the froth recovery as a function of froth stability, residence time, and transport distance. Water recovery and gangue entrainment were also modelled to estimate concentrate grades. The model was tested and calibrated using experimental results from tests conducted in a Concorde Cell Lab Unit. A case example is presented for a semi-batch exhausting test performed with minerals from a copper concentrator plant. Good agreement between simulated and experimental results demonstrated the robustness and flexibility of the model. Additionally, the results showed collection rate constants significantly higher than those typically reported for conventional flotation cells (more than 100 times higher for Cu), due to the smaller collection volume and shorter residence time in the Concorde Cell. The calibrated model was then applied to simulate an industrial operation, where sensitivity analyses showed consistent responses to variations in operating conditions. Overall, the proposed model provides a practical tool for predicting the metallurgical performance of intensified flotation cells, supporting the integration of this new technology into modern concentrator flowsheets for the development of hybrid circuits.

1. Introduction

In flotation plants, specific stages have traditionally been designed to optimize overall performance. For example, the rougher and scavenger stages, typically configured as banks of mechanical cells, are primarily aimed at maximizing recovery and generating the final tailings. Conversely, cleaner, recleaner, and cleaner–scalper stages focus on concentrate upgrading at moderate recoveries, using either mechanical cells or pneumatic columns, and producing both final concentrate and recycle streams. In general, such circuits perform well when processing high-grade feeds and relatively simple ores, where a broad range of intermediate particle sizes (e.g., 20–150 µm) achieve high recoveries, with only minor losses at the extremes of the so-called “elephant curve” (finer and coarser fractions). However, this scenario has shifted in recent years. The increasing prevalence of complex ores, characterized by lower liberation and higher contents of non-valuable minerals, together with declining feed grades (often below 0.4% Cu), frequently require finer grinding to achieve adequate mineral liberation. Conversely, coarser grinding may be necessary to meet higher plant throughputs while addressing water scarcity. In both scenarios, the performance of conventional mechanical cells and columns become insufficient, making additional equipment with more specialized functions essential to improve the recovery of ultrafine and coarse particles. Numerous studies have examined the influence of particle size on flotation recovery, emphasizing the need to separately process different size fractions as ores become increasingly complex and difficult to concentrate []. These factors have driven the development of hybrid circuits that combine mechanical cells and new technologies in flotation plants, while further reinforcing the need to address energy efficiency and water constraints [].

1.1. Intensified Flotation Cells for Recovery of Fine and Ultrafine Particles

The processing of fine and ultrafine particles has become an increasingly critical challenge over the years, mainly due to the low collision and attachment efficiencies between these particles and bubbles. To address this issue, several strategies have been proposed, focused on enhancing the recovery of these particles. A recent study analyzed and discussed the advantages and limitations of these approaches, including selective aggregation to increase effective particle size, the use of nano and microbubbles to enhance collision efficiency, and the application of reactor–separator-type flotation cells that provide more intense hydrodynamic conditions []. In this context, flotation technologies specifically aimed at improving fine and ultrafine recovery have been developed [,,]. Thus, different types of intensified flotation cells have been tested at pilot and industrial scales, such as the Jameson cell [], Imhoflot Cell [], Concorde Cell [], SFR and DFR cells [], and the Reflux Cell [].

The intensified flotation cells represent a promising option to enhance overall plant performance when ultrafine fractions are present. These cells generate a localized collection zone of high turbulence that significantly increase the probability of collision between fine particles and bubbles, thereby enabling the recovery of minerals that would otherwise be lost to tailings [,,].

The design of intensified flotation cells is based on the reactor–separator concept []. In this framework, the reaction zone corresponds to the formation of particle–bubble aggregates, which require specific operating conditions to promote high levels of energy dissipation (intensive collection) []. The separation zone is associated with the disengagement of these aggregates from the pulp and their transport to the froth phase. Finally, the froth zone reduces water recovery and entrainment of non-valuable minerals into the concentrate. This configuration is consistent with previous studies, which identified two distinct regions within the pulp: a highly agitated collection zone and a relatively quiescent upper zone [].

The identification of distinct zones in mechanical flotation cells and columns has been crucial for the development of more advanced flotation models, allowing for the collection and separation processes to be represented independently []. This approach has improved the understanding of how hydrodynamics, bubble–particle interactions, and froth transport contribute to overall performance. Nevertheless, modelling intensified flotation cells remains challenging due to their more complex operation and the scarcity of key hydrodynamic and kinetic data, most of them difficult to obtain experimentally.

1.2. Modelling Structure of Flotation Equipment

1.2.1. Mechanical Cells

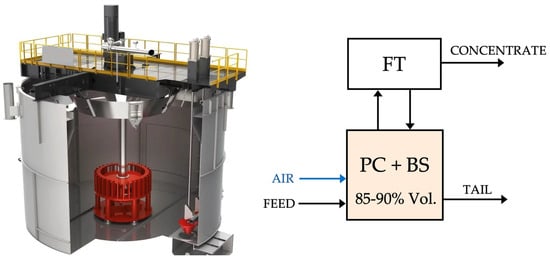

The classical mechanical cells used in rougher, cleaner, and scavenger duties are well described by two main zones: the particle collection (PC) plus bubble-separation (BS) zone, and the froth transport zone (FT). In this case, there is a single volume where the (PC + BS) zone is confined, representing around 85–90% of the total cell volume. Typical mechanical cells are either forced-air or self-aerated. Figure 1 shows a forced-air cell.

Figure 1.

Mechanical forced-air flotation cell [].

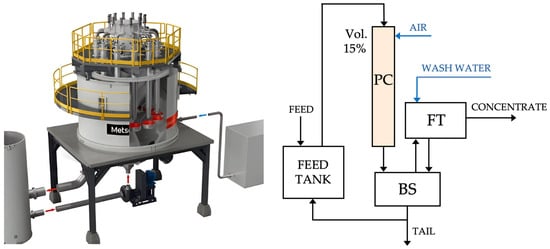

1.2.2. Pneumatic Columns

The classical pneumatic columns, used mainly in cleaner and re-cleaner duties, are also well described by two main zones: the particle collection (PC) plus bubble-separation (BS) zone, and the froth transport zone (FT). In this case, there is also a single volume where the (PC + BS) zone is confined, representing around 90% of the total cell volume, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flotation columns.

In mechanical cells and columns, the collection and separation processes occur within the same overall pulp volume, making it impossible to isolate the effective residence time for the particle–bubble aggregate’s formation from the separation process. This characteristic prevents the establishment of the optimal conditions to achieve the flotation performance targets, whether for finer or coarser minerals [].

1.2.3. Intensified Flotation Cells

Classical approaches are commonly applied for modelling intensified flotation cells, typically based on first-order kinetics with a single or a distribution of rate constants (e.g., Klimpel and Gamma). While these models can reproduce the overall flotation response, they do not explicitly differentiate between the collection and separation stages. As a result, they are limited to assessing the individual effects of key operational variables, such as froth depth, air flow rate, and wash water addition on metallurgical performance.

In this study, a metallurgical model for the intensified Concorde Cell was developed, accounting for the different zones of the process, along with its hydrodynamic and kinetic characteristics. The model enables the simulation of both semi-batch exhausting laboratory tests and continuous (steady-state) operations at laboratory and plant scales. Model testing and calibration was carried out using laboratory data, and this paper presents a case example based on a semi-batch exhausting test, followed by a preliminary simulation of industrial operation.

2. Methodology

2.1. Development of a Flotation Model for the Concorde Cell

2.1.1. Modelling Structure

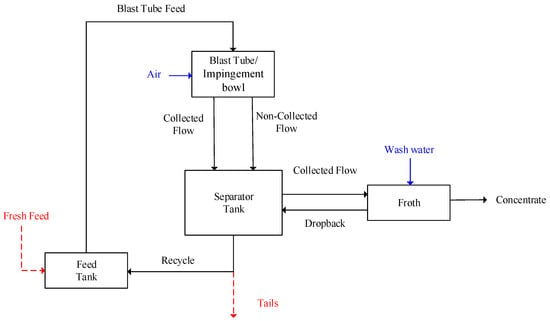

The Concorde Cell technology features an intensive collection zone, the so-called Concorde Blast Tube, which provides high-energy dissipation within a compact volume. The discharge from the Blast Tube impacts the impingement bowl, minimizing the bypass of valuable minerals to the tailings. A portion of the tailings is recirculated to the feed tank, where it mixes with the fresh feed before entering the Blast Tube. The cell operates under pressure, with high pulp velocities within the Blast Tube’s core component [,].

For modelling purposes, the Concorde Cell can be characterized using distinct zones, similar to mechanical cells and columns (Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively). Here, three different zones are identified for the flotation-separation process in addition to the feed tank: (i) the particle collection (Blast Tube) plus impingement bowl (PC), (ii) the bubble-separation (BS), and (iii) the froth transport (FT) zones, as illustrated in Figure 3. In this case, the PC zone represents only about 15% of the total system’s volume.

Figure 3.

Model structure of Concorde Cell.

Based on this structure, a model was developed to describe the metallurgical performance of the Concorde Cell.

Figure 4 presents a diagram of the Concorde Cell, illustrating the feed tank and the three main zones for the flotation-separation process, with the flowrates of valuable mineral throughout the system. This scheme applies to both continuous and semi-batch (exhausting) operations. The key difference is that during continuous operation, the system is fed with a constant fresh feed flowrate and continuously discharges tailings (indicated by red dashed arrows), with partial recirculation to the feed tank. In contrast, the semi-batch exhausting operation starts with a fixed pulp volume, without additional fresh feed, and all tailings recirculate to the feed tank.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the different zones of a Concorde Cell for modelling (continuous operation includes the red dashed arrows).

The valuable mineral from the feed tank enters the collection zone, composed of the Blast Tube and the impingement bowl. Particle collection occurs in the Blast Tube’s core component, but the discharge into the impingement bowl may promote additional particle collection or detachment. Therefore, in this first approximation, a net collection rate describes this zone as a single stage due to limited experimental data.

From the collection zone, the flowrates of collected and non-collected minerals proceed to the separation tank. In this zone, collected minerals are transported to the froth phase, while a small fraction may be lost to tailings (reflecting the separation tank’s efficiency), together with the non-collected fraction. A portion of tailings recirculates to the feed tank (100% in the semi-batch operation), where it combines with the fresh feed in continuous mode to supply the Blast Tube. The froth zone produces the final concentrate, while minerals rejected from the froth return to the separation tank as non-collected material. No additional mineral collection is expected to occur within the separation tank.

Water flowrates are also included in the model, following the same paths as the valuable minerals throughout the system.

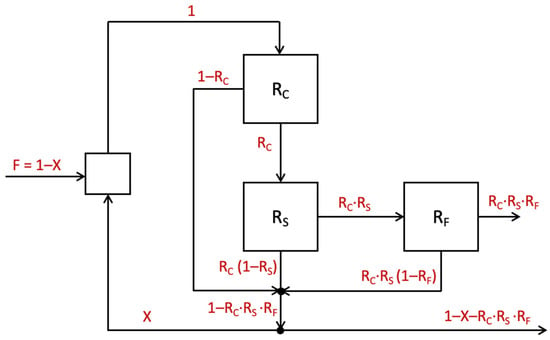

2.1.2. Calculation of the Total Recovery of a Concorde Cell

The objective of the modelling was to represent the Concorde Cell realistically, accounting for the sub-processes and internal recirculation within the equipment. In mechanical cells, recovery is a function of the collection and froth recoveries, according to the two-zone model [], which represents a mass balance within the cell. In the same way, Figure 5 shows the calculation of the total recovery of a Concorde Cell from the recovery of each individual zone through a mass balance. In this approach, the cell recovery is expressed as a function of three zones: the collection, separation, and froth zones (a “three-zone” model). This aligns with the three zones identified by Savassi [] for mechanical cells, with the distinction that in the intensified flotation cells, these zones are physically independent and can be identified and characterized separately.

Figure 5.

Mass balance inside a Concorde Cell to estimate total recovery.

Figure 5 shows the mass flowrates of valuable minerals throughout the system, expressed in terms of the recoveries in each zone: collection (RC), separation (RS), and froth (RF). Additionally, flowrate X is defined, which is related to the recirculation ratio (RR), calculated as the mass flowrate recirculated from the tailings to the feed tank (X) divided by the flowrate entering the Blast Tube (defined as 1). Therefore, X is equivalent to RR, as expressed in Equation (1). Although the recirculation ratio is normally reported as a volumetric ratio (typically 30–60%), it can be converted to a mass-based ratio for mass balance calculations.

Then, solving the mass balance in the system, the total recovery (RT) in the Concorde Cell is calculated as shown in Equation (2), considering the concentrate (RC·RS · RF) divided by the feed flowrate (F = 1 − X).

2.1.3. Flotation Models to Characterize a Concorde Cell

The Concorde Cell model considers each zone shown in Figure 5 independently, in order to estimate metallurgical performance. The input variables for modelling are classified into three main categories, as outlined below:

- 1.

- Feed characteristics, such as solid flowrate (continuous operation), initial pulp volume (exhausting operation), solid content, mineral grades, content and grade of fine particles.

- 2.

- Cell design specifications, such as Blast Tube diameter and length, number of Blast Tubes, inlet nozzle diameter, cell diameter and height, froth area, lip length, and feed tank volume.

- 3.

- Operating conditions, such as froth depth, air and wash water flowrates, gas holdup, and pressure.

On the other hand, for the simulation of the Concorde Cell’s performance, the main assumptions were as follows:

- The overall particle collection follows a first-order kinetic.

- The Blast Tube behaves like a plug flow.

- The feed and separation tanks behave like perfect mixers.

- The collection and detachment processes in the Blast Tube and impingement bowl are represented together, as a net collection kinetic.

- No mineral collection occurs in the pulp separator tank. Additionally, an efficiency factor was applied to account for the potential loss of collected minerals to the tailings (e.g., 95%).

Then, the models used to represent each of the three stages in the Concorde Cell are described below:

- Collection zone (BT + IB): The mixing regime was modelled as a plug flow inside the Blast Tube, while a rectangular distribution [] was used to describe the rate constant. Thus, the collection recovery (RC) of the floatable mineral is estimated as shown in Equation (3):where is the rate constant from the Klimpel model and is the pulp residence time in the Blast Tube. The latter can be calculated as a function of the Blast Tube’s volume (VBT), the gas holdup in the Blast Tube (εG), and the feed pulp volumetric flowrate (QF), as shown in Equation (4).

- Separator tank: This zone was assumed to behave as a perfect mixer. For metallurgical characterization, an efficiency factor (θ) was introduced to account for the net detachment of collected minerals from the Blast Tube and impingement bowl discharge. This parameter can be adjusted by the user, but an initial value of 95% was adopted for simulation purposes. Thus, the mass flowrate of collected minerals entering the froth is calculated as shown in Equation (5), where is the mass flowrate of collected minerals going out of the Blast Tube.

- Froth zone: The froth recovery model is an adaptation of that proposed by Yianatos et al. [] for conventional mechanical cells, in which froth recovery is expressed as a function of froth stability (SF), froth residence time (tF), and the nominal transport distance to the overflow lip (L). SF is calculated as the total mass flowrate of solids entering the froth with respect to the froth area, AF (Equation (6)), while the residence time is given by the froth depth (HF) divided by the superficial gas rate at the top of the froth (JG,F), as shown in Equation (7).Additionally, water recovery and gangue entrainment models were included to enable the estimation of concentrate grades.

- Water recovery model: The water recovery in froth was modelled to then estimate gangue entrainment. Water recovery is defined as the water flowrate in concentrate divided by the one entering the froth () and was expressed as a function of mineral froth recovery (RF), froth depth (HF), and superficial gas rate (JG,F), as shown in Equation (8). Here, λ is a constant parameter.Then, to estimate the water flowrate in the concentrate, the water flowrate entering the froth is required, which was estimated using Equation (9):where corresponds to the liquid retention in the froth near the pulp–froth interface, assuming a packed bed of spheres (26%), is the density of pulp for fine particles (e.g., less than 45 µm), and is the fraction of fine particles. Additionally, and are the superficial gas rate and the cross-sectional area at the interface level, respectively.

- Gangue entrainment model: The gangue recovery by entrainment (RENT) was estimated as a function of the water recovery in the cell (with respect to the fresh feed) (RW), the entrainment factor (ENT), and the superficial water rate at the top of the froth level (JW), as shown in Equation (10). In this case, ξ1 and ξ2 are fitting parameters.The entrainment factor (ENT) was obtained from the empirical model proposed by Wang et al. [], based on experimental data, which relates the ENT to the effective liquid velocity at the interface and particle sedimentation, as shown in Equation (11).where is the effective (net) liquid velocity at the pulp–froth interface and is the particle settling velocity, which was estimated using the approach proposed by Neethling and Cilliers []. Then, p and q are fitting parameters.The net liquid velocity depends on the liquid volumetric flowrate in the concentrate (FWC), the cross-sectional area at the interface (AC), and the liquid retention near the interface (εGIN), as shown in Equation (12). On the other hand, depends on solid and water densities ( and , respectively), acceleration of gravity (g), mean size of fine particles (), and water viscosity (μ), as shown in Equation (13).

2.2. Testing of the Model from Experimental Data

The flotation model was tested using multiple experimental datasets obtained from flotation tests conducted in a laboratory Concorde Cell. These data included different minerals, such as copper, iron, nickel, lead, and coal.

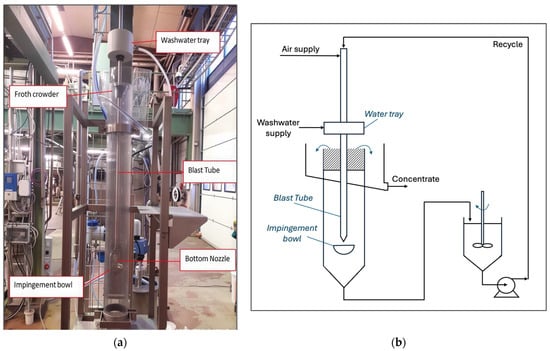

This paper shows one of the datasets used for model testing and calibration as an example, which consists of results from a semi-batch exhausting test, performed on a sample from the column feed stream of a copper concentrator plant. This sample is mainly composed of Chalcopyrite, Pyrite, and Molybdenite as floatable minerals. The experimental test was carried out in the Metso Pori Research Center in Finland, using a Concorde Cell Lab Unit of 150 mm diameter [,], as shown in Figure 6. The pH used in the test was 10.5, and the following reagents were used: lime as the pH modifier, a type of Aerophine as the collector, and MIBC as the frother.

Figure 6.

(a) Picture [] and (b) diagram of the Concorde Cell Lab Unit setup in the laboratory.

The test started by mixing the mineral sample and water in the conditioning tank, forming an initial pulp volume of approximately 25 L, with continuous agitation to prevent solids settling. After reagent conditioning, the pulp was transferred to the cell, and recirculation was initiated immediately. Airflow was then introduced and adjusted to reach the target APR. Flotation time was recorded from the first froth overflow. Concentrates and tailings were collected and prepared for chemical analysis.

Table 1 presents the operational conditions under which the laboratory flotation test was conducted. The mineral processed in the Concorde Cell Lab Unit contained 8.5% Cu, and the equipment was operated with an air/pulp ratio (APR) of 0.6, based on volumetric flowrates entering the Blast Tube, a superficial water rate (JW) of 0.05 cm/s, and a froth depth of 400 mm.

Table 1.

Operational conditions of the laboratory test for the Cu and Fe minerals.

Once the dataset was fitted (model calibration), the kinetic parameters associated with the Blast Tube (collection) were obtained and subsequently used to simulate an industrial operation under specific conditions. A Concorde Cell with 6.5 m diameter and 24 Blast Tubes was selected for the simulation. The same mineral feed as in the semi-batch test was considered. The operating conditions are based on recommended ranges: an APR of 0.5, the JW was 0.05 cm/s, and the froth depth was 300 mm (Table 2).

Table 2.

Operational conditions of the simulated industrial operation.

Then, the metallurgical performance in the industrial cell was evaluated through sensitivity analysis, varying the APR from 0.5 to 0.8 and the froth depth from 300 to 600 mm. This analysis allows for the assessment of the flotation model’s response trends under different operational scenarios.

Currently, no data from industrial operations are available to calibrate the model. This will be assessed in future work.

3. Results

3.1. Fitting of Experimental Data

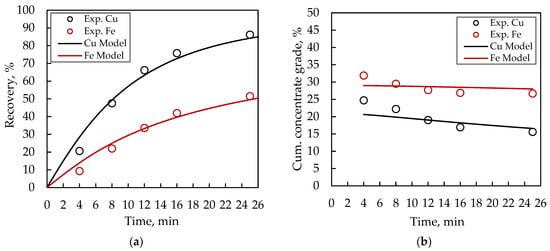

The Cu and Fe recoveries obtained from the semi-batch test were analyzed and fitted using the proposed model. Figure 7a,b shows the mineral recovery and concentrate grade profiles over time, respectively. Experimental data (dots) and modelled predictions (solid lines) show a good agreement, with relative errors below 10% for most data points. The flotation model successfully described the kinetic behaviour of Cu and Fe over time, as well as the cumulative concentrate grade behaviour for the semi-batch operation.

Figure 7.

Fitting results for Cu and Fe: (a) recoveries and (b) concentrate grade profiles.

From the fitting, the kinetic parameters associated with mineral collection in the Blast Tube were obtained, as shown in Table 3. Collection rate constants of 162 and 72 min−1 were determined for Cu and Fe, respectively. It should be noted that these values are significantly higher than those typically reported for conventional flotation cells (e.g., kmax: 0.3–2.0 min−1 for Cu), where the collection rate constants account for the entire pulp volume, with residence times of approximately 4–6 min. In contrast, although the total residence time in the Concorde Cell is similar to that of a conventional cell (2–5 min), the collection process takes place in a much smaller, well-defined volume, with residence times of only 5–10 s, about 25–30 times shorter than in conventional mechanical and column cells.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters in the collection zone for the Cu and Fe minerals.

The maximum recoveries were 93% and 73% for Cu and Fe, respectively, which are similar to those obtained for mechanical cells, because this parameter is mainly associated with the quality of the minerals.

3.2. Simulation of an Industrial Operation

The kinetic parameters obtained from the semi-batch laboratory test (Table 3) were used to simulate the metallurgical response of an industrial Concorde Cell in continuous operation (under the conditions shown in Table 2).

Table 4 shows the metallurgical results from the simulation. A Cu recovery of 66% and a concentrate grade of 23% were obtained. In this case, the recirculation ratio, i.e., the volumetric flowrate recirculated to the feed tank divided by the flowrate entering the Blast Tube, was 45%.

Table 4.

Metallurgical results for the simulated industrial operation for the Cu and Fe minerals.

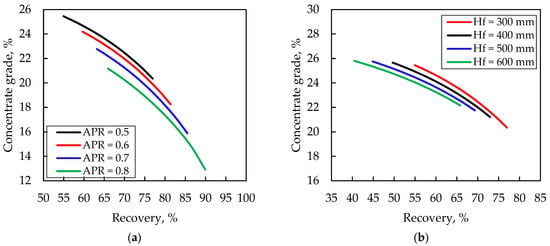

Figure 8 shows the Cu grade–recovery curves for the simulated industrial cell under a range of different operating conditions (sensitivity analysis). Thus, Figure 8a shows the effect of a varying APR (0.5 to 0.8), while Figure 8b shows the effect of changing the froth depth (HF) (300 to 600 mm). Each point along the grade–recovery curves represents a different recirculation ratio. In this analysis, values ranging from 0 to 80% were evaluated.

Figure 8.

Sensitivity analysis for an industrial cell. Effect of (a) APR and (b) froth depth.

These results show the expected trends in terms of recovery and concentrate grades. Recovery increases when the APR increases, while it decreases when the HF increases. The opposite effect was observed for concentrate grade, because a higher air flowrate favours collection recovery, while HF favours selectivity, and therefore, concentrate grade.

The metallurgical model proved to be a valuable tool for representing industrial scenarios and assessing potential hybrid circuit configurations.

4. Conclusions

A first approach for the modelling and simulation of the Concorde Cell was successfully developed, characterizing the three zones within the equipment separately. In this way, the kinetics of the effective collection zone in the Blast Tube were identified and characterized, independent from the separation and froth zones.

The flotation model was suitably tested and calibrated for semi-batch exhausting operations using different ores, showing a good agreement between modelled and experimental data (with relative errors below 10% for the case example). Then, the flotation model showed good potential to represent an industrial cell within the typical range of variables. Full validation of the model for an industrial operation will be carried out once industrial data become available.

The collection rate constants associated with the Blast Tube were found to be significantly higher than those typically reported for conventional flotation cells (over 100 times higher for Cu). This occurs because the collection process in the Concorde Cell takes place in a much smaller volume, with residence times of only 5–10 s. This is about 25–30 times shorter than in conventional cells, where the collection rate constant accounts for the entire pulp volume, without distinguishing between collection and separation processes. Despite this, the total residence time in the Concorde Cell remains comparable to that of mechanical cells (2–5 min).

The application of this approach is useful to assess different types of intensified flotation cells and different scenarios regarding hybrid circuits in industrial flotation plants, to estimate their potential advantages, looking at the most suitable configuration according to plant requirements, for instance, to improve the fine particles’ recovery or the final concentrate grade.

In future work, mineral characteristics such as mineralogy and particle size distribution will be incorporated into the model to enhance its representativeness. In addition, other key factors affecting flotation performance, such as water quality and clay properties, will be evaluated to be implemented into the model. On the other hand, ongoing work aims to conduct additional experimental tests to further validate and strengthen the model’s results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V., J.Y. and I.S.; methodology, P.V., J.Y., M.B. and A.Y.; software, M.B., P.V. and D.B.; validation, M.B., I.S. and A.Y.; formal analysis, M.B. and D.B.; investigation, P.V. and J.Y.; resources, J.Y. and I.S.; data curation, P.V., M.B. and D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.V., J.Y. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, I.S., A.Y. and D.B.; visualization, P.V., J.Y. and M.B.; supervision, JY. and I.S.; project administration, P.V. and D.B.; funding acquisition, J.Y., I.S. and A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), Fondecyt Project 1201335.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), FONDECYT Project 1241830, and Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, Chile, for providing funding for research in industrial process characterization and modelling. Additionally, the invaluable contribution of the personnel at Metso Finland, and their permission to present these results, are greatly acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Ian Sherrel, Alejandro Yáñez and Dominique Betancourt were employed by the company Metso Finland Oy. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Trahar, W.G. A rational interpretation of the role of particle size in flotation. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1981, 8, 289–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Safari, M.; Khoshdast, H.; Güner, M.K.; Hoang, D.H.; Sambrook, T.; Kowalczuk, P.B. Introducing key advantages of intensified flotation cells over conventionally used mechanical and column cells. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2022, 58, 155101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhpay, S.; Filippov, L.; Fornasiero, D. Flotation of fine particles: A review. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2020, 42, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankosa, M.J.; Kohmuench, J.N.; Christodoulou, L.; Yan, E.S. Improving fine particle flotation using the StackCell™ (raising the tail of the elephant curve). Miner. Eng. 2018, 121, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohmuench, J.N.; Mankosa, M.J.; Thanasekaran, H.; Hobert, A. Improving coarse particle flotation using the HydroFloat™ (raising the trunk of the elephant curve). Miner. Eng. 2018, 121, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chimonyo, W.; Peng, Y. Flotation behaviour in reflux flotation cell—A critical review. Miner. Eng. 2022, 181, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R.; Jameson, G.J.; Manlapig, E.V. The development and application of the Jameson cell. Miner. Eng. 1991, 4, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Gungor, E.; Samet, E.; Durunesil, D.; Hoang, D.H.; Vinnett, L. ImhoflotTM Flotation Cell Performance in Mini-Pilot and Industrial Scales on the Acacia Copper Ore. Minerals 2024, 14, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, G. The Concord Cell. In Symposium on Flotation Developments; Outotec: Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aljohani, F.; Mogashoa, S.; Hatton, D.; Banerjee, T.; Layyous Gedeon, F. Integration of Woodgrove Direct Flotation Reactors DFR into Jabal Sayid from Pilot to Operation. In Proceedings of the Procemin-Geomet 2025, Santiago, Chile, 6–8 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, S.; Wang, P.; Galvin, K.P. Benchmarking a Single-Stage Reflux Flotation Cell Against a Multi-Stage Industrial Copper Concentrator and Lab-Scale Mechanical Cell. Minerals 2025, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Safari, M.; Hoang, D.H.; Khoshdast, H.; Albijanic, B.; Kowalczuk, P.B. Technological assessment on recent developments in fine and coarse particle flotation systems. Miner. Eng. 2022, 180, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yianatos, J.; Vallejos, P.; Rodríguez, M.; Cortínez, J. A scale-up approach for industrial flotation cells based on particle size and liberation data. Miner. Eng. 2022, 184, 107635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J.A. Column Flotation: A selected review-part IV: Novel flotation devices. Miner. Eng. 1995, 8, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wanga, H.; Lia, X.; Lia, D.; Wanga, W.; Lianga, Y.; Yana, X.; Zhang, H. Effect of energy input on flotation of particles with different sizes: Perspective of hydrodynamics characteristics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savassi, O. A compartment model for the mass transfer inside a conventional cell. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2005, 77, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J.; Dobby, G. Column Flotation; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Metso. Available online: https://www.metso.com/es/portafolio/tankcell/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Yianatos, J.; Vallejos, P. Challenges in flotation scale-up: The impact of flotation kinetics and froth transport. Miner. Eng. 2024, 207, 108541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, G. New directions in flotation machine design. Miner. Eng. 2010, 23, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, A.; Kupka, N.; Tunç, B.; Suhonen, J.; Rinne, A. Fine and ultrafine flotation with the Concorde Cell™—A journey. Miner. Eng. 2024, 206, 108538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimpel, R.R. Selection of chemical reagents for flotation. In Mineral Processing Plant Design, 2nd ed.; Mular, A.L., Bhappu, B., Eds.; SME: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Chapter 45; pp. 907–934. [Google Scholar]

- Yianatos, J.; Vallejos, P.; Grau, R.; Yáñez, A. New approach for flotation process modelling and simulation. Miner. Eng. 2020, 156, 106482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Runge, K.; Peng, Y.; Vos, C. An empirical model for the degree of entrainment in froth flotation based on particle size and density. Miner. Eng. 2016, 98, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethling, S.; Cilliers, J. The entrainment factor in froth flotation: Model for particle size and other operating parameter effects. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2009, 93, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunç, B.; Duran, M.; Nikolov, S.; Kupka, N.; Grau, R.; Yáñez, A. The effect of operational changes on gas dispersion in Concorde Cell™. In Proceedings of the Flotation’23, Cape Town, South Africa, 6–9 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kupka, N.; Suhonen, J.; Bird, M.; Yáñez, A. Benchmarking the metallurgical performance of the Concorde Cell™ at lab, pilot and industrial scales. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Canadian Mineral Processors Operators Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 17–19 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).